Abstract

Background

Surgical resection of locally advanced or borderline pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is a recognized procedure with curative intent performed in specialized oncology centers. Postoperative dysautonomia such as gastroparesis, mild hypotension, and diarrhea are common in elderly patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy. A distinctive feature of our case, is the severing of an important sympathetic chain by the surgical procedure, leading to recurrent severe neurogenic shock. Locally advanced borderline tumor extension, aggressive maximal local tumor resection, and advanced age of the patient were the combined factors that explained the observed postoperative complication.

Case Description

An 80-year-old woman underwent an elective R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy with total mesopancreas excision, distal gastrectomy and portal vein resection without relevant intraoperative and immediate postoperative complication. Pathology confirmed a 5.0 cm × 3.2 cm × 1.9 cm ductal adenocarcinoma in the head of the pancreas. After discharge, the patient returned to the emergency room complaining of nonspecific malaise, lipothymia, and cold sweating that was exacerbated by bowel movement attempts. During hospitalization, the patient experienced two additional severe hypotensive episodes with identical clinical presentation that required resuscitative measures in the intensive care unit (ICU). Because the third hypotensive episode developed without an obvious causal factor, apart from evacuation attempts, the hypothesis of neurogenic shock due to secondary splanchnic dysautonomia caused by extensive resection of the celiac plexus nerve structures after duodenopancreatectomy was considered.

Conclusions

This discussion is important, as it enables the care team to recognize this differential diagnosis and provide the best care for the patient. The patient was treated with sympathomimetics, fludrocortisone, and mechanisms to increase venous return when clinical improvement promptly occurred, allowing discharge from the hospital. Despite the challenging prognosis of the disease, we were able to provide the patient with moments at home with their family.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, duodenopancreatectomy, neurogenic shock, case report

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Differential diagnosis of a life-threatening situation after curative surgery for pancreatic cancer.

What is known and what is new?

• Post-ganglionic sympathetic nerve fibers can be affected in pancreatic tumor resections, and transient dysautonomia can be expected.

• The study included neurogenic shock in similar situations as a differential diagnosis, which had not yet been reported in the literature.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• Recognizing the situation and immediately implementing therapeutic measures can reduce risks and additional costs in the management of postoperative complications associated with pancreatoduodenectomy with complete removal of the mesopancreas.

Introduction

Surgical resection of locally advanced or borderline pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a recognized procedure with curative intent performed in specialized oncology centers (1). Nevertheless, the prognosis of patients with complete tumor resection remains poor because of the high incidence of distant and local recurrence in patients undergoing upfront surgical resection (2). In addition, early locoregional recurrences are a common pattern observed in patients with borderline tumors (3).

Early involvement of retropancreatic tissue by lymph node spread along with peripancreatic nerve plexuses is one explanation for the pancreatic recurrence pattern (4). A perineural layer is located in the posterior region of the pancreas, called the mesopancreas. The term mesopancreas is not widely accepted in the literature. This region, was firstly defined as mesopancreas by Gockel I et al. and Gaedcke J et al. (4,5), but it can also be known as pancreatic head plexus, term defined by the Japan Pancreas Society in 2017 (6) or as a nonexistent region due to the lack of precise anatomic borders.

The anatomical limits of the mesopancreas include: the medial and posterior aspect of the uncinate process and pancreatic head (lateral delimitations), the right aspect of the superior mesenteric vein and superior mesenteric artery (medial limits), the origin go the celiac trunk (cephalic limit), the beginning of the mesenteric root (caudal limit) and the left renal vein posterior delimitation (7).

This well-vascularized tissue extends from the posterior region of the pancreatic head to the vicinity of the superior mesenteric vein and superior mesenteric artery. The lymphatic chain of the mesopancreas follows the neural plexus in the posterior region of the pancreas (8). Up to 100% of pancreatic tumors show some degree of neural invasion with increasing severity of invasion resulting in significantly decreased survival, which shows the importance of extensive resection in specialized centers (9). Emerging evidence shows that the peripheral nerve is an important non-tumor component in the tumor microenvironment that regulates tumor growth and immune escape (10).

The decision to perform pancreaticoduodenectomy in an elderly patient is often influenced by the presence of comorbid conditions associated with postoperative side effects (11). Postoperative dysautonomia such as gastroparesis, mild hypotension, and diarrhea are common in elderly patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy (12,13). This report describes recurrent neurogenic shock as a postoperative complication associated with pancreaticoduodenectomy with totally excision of the mesopancreas. To our knowledge, this life-threatening complication has not been reported previously. The diagnostic procedure and treatment are described below. We present this case in accordance with the CARE reporting checklist (available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-23-494/rc).

Case presentation

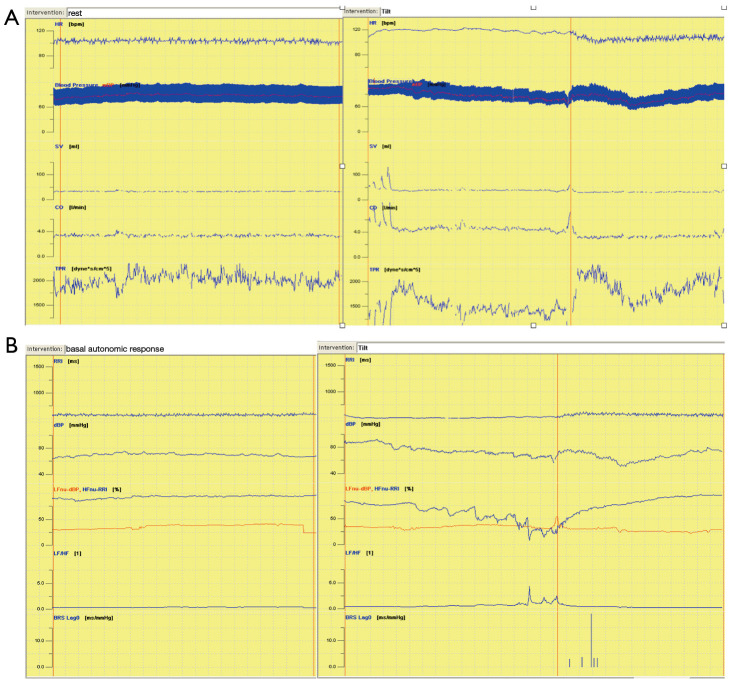

An 80-year-old white woman with a history of controlled hypertension and early breast cancer treated with surgery and adjuvant hormone therapy in 2006 was referred. In December 2021, she experienced acute pancreatitis, which was treated clinically without further investigation. In February 2022, she was diagnosed with a second acute pancreatitis and admitted to the Sírio-Libanês Hospital Emergency Center. Abdominal computed tomography showed a 3.5 cm solid mass in the pancreatic head with involvement of the portal vein/superior mesenteric vein, causing dilatation of the duct of Wirsung and signs of acute edematous pancreatitis. Clinical staging excluded metastatic disease. After clinical support and biliary stent placement in March 2022, the patient became eligible for and underwent elective R0 pancreaticoduodenectomy with total mesopancreas excision, distal gastrectomy and portal vein resection without relevant intraoperative and immediate postoperative complication in April 2022. The decision for surgical management of the disease was made in a multidisciplinary approach and in joint decision with the patient and family members. Pathology confirmed a 5.0 cm × 3.2 cm × 1.9 cm ductal adenocarcinoma in the head of the pancreas, which was resected with clear margins. Eight of 38 lymph nodes were positive for metastasis (American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition stage pT3pN2). The patient was discharged from the hospital 7 days after surgery. Three days after discharge, the patient returned to the Emergency Center complaining of nonspecific malaise, lipothymia, and cold sweating that was exacerbated by bowel movement attempts. The patient was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 84 mmHg × 58 mmHg and a heart rate of 104 bpm. She was sweating and had a respiratory rate of 19 bpm, a temperature of 36.3 °C, and a oxygen saturation of 95% on room air. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) with suspected postoperative septic shock. The patient required intensive intravenous hydration, broad-spectrum antibiotics, vasoactive medications, and ventilatory support. However, the clinical course showed an unexpectedly rapid and complete clinical recovery within the first 12 hours of intensive treatment, allowing the patient to be discharged from the ICU after 24 hours. During hospitalization, the patient experienced two additional severe hypotensive episodes with identical clinical presentation that required resuscitative measures in the ICU, with 5 and 7 days between events. Because the third hypotensive episode developed without an obvious causal factor, apart from bowel movements attempts, the hypothesis of neurogenic shock due to secondary splanchnic dysautonomia caused by extensive resection of the celiac plexus nerve structures after duodenopancreatectomy was considered. The diagnosis of orthostatic dysautonomic hypotension was confirmed by a tilt test (Figure 1A,1B), which demonstrated an absence of baroreflex sensitivity in the horizontal dorsal decubitus during the study period and in orthostasis.

Figure 1.

Autonomic test response evaluation for the diagnosis of orthostatic dysautonomic hypotension. (A) Resting autonomic responses (left) versus tilt test lines (right). (B) Basal autonomic responses versus tilt-test lines regarding autonomic responses (left) versus tilt-test (right). HR, heart rate; mBP, mean blood pressure; SV, stroke volume; CO, cardiac output; TPR, total peripheral resistance; RRI, R-R interval; dBP, diastolic blood pressure; LFnu-dBP, low frequency diastolic blood pressure in normalized units; HFnu-RRI, high-frequency R-R interval in normalized units; LF/HF, heart rate variability in the frequency domain with a low frequency/high frequency ratio obtained in the basal period and in an orthostatic inclination of 70°; BRS, baroreflex sensitivity.

Treatment with sympathomimetics, fludrocortisone, compression stockings, and lower abdominal compression was effective and prevented new episodes of hypotension.

The patient was discharged from the hospital in June 2022. She refused adjuvant systemic therapy, and returned to her hometown, maintaining an excellent quality of life for approximately 9 months, during which time her family kept in touch with the medical team, sending photos and videos of the patient participating in significant family events without any symptoms. This was considered a success, given the high risk of recurrence (pT3pN2) and the high likelihood that, in the absence of response to systemic therapy, it could lead to early compressive symptoms and loss of quality of life, being well-controlled with surgical treatment during the reported time. Follow-up in December 2022 revealed asymptomatic liver metastases, but in March 2023, patient underwent a teleconsultation from her city, during which a possible cholangitis was identified. We were informed that she died on March 2023.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee from Sírio-Libanês Hospital and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Discussion

Dissection of the mesopancreas is performed in the treatment of PDAC in the pancreatic region by laparotomy or, more recently, by robot (14). Recent improvements in surgical techniques for patients with pancreatic cancer involve the mesopancreatic resection margin. This procedure reduces local recurrences in patients undergoing R0 resection. The operation implies that the mesopancreatic resection should be extended to the paraaortic area to maximally remove retro-pancreatic lymph nodes. As a result, postganglionic sympathetic nerve fibers may be affected, and transient dysautonomia should be expected (15). Furthermore, PDAC development and progression appear to be under complex neural influences where sensory and sympathetic nerves stimulate tumour growth, while parasympathetic nerves inhibit tumorigenesis through cholinergic signaling (16).

This case report describes a severe and life-threatening secondary dysautonomia caused by diversion of sympathetic splanchnic nerve. The clinical presentation was characterized by recurrent neurogenic shock in an elderly patient. Locally advanced borderline tumor extension, aggressive maximal local tumor resection, and advanced age of the patient were the combined factors that explained the observed postoperative complication. In addition, the effort associated with the patient’s attempts to defecate (e.g., the Valsalva maneuver) caused an increase in intrathoracic and abdominal pressure, which reduced cardiac preload. Also, the surgical intervention seriously impaired the baroreflex compensatory mechanism to maintain systemic pressure. This combination triggered the neurogenic shock.

The neurogenic shock presented by the patient is defined as a hypo-perfused state of the organ tissue as a result from the interruption or deregulation of the autonomic nervous system control over the vascular tone. This condition consists of the lack of sympathetic tone, due to plexus lesion, for example, resulting in an uncontrolled parasympathetic system, which leads to an unbalanced autonomic nervous system activity. This decline in sympathetic control over the vascular tone leads to an expanded capacitance blood vessel in the lower body extremities. This results in decreased cardiac filling, which leads to hypotension and shock. Furthermore, the diminished sympathetic control over the heart leads to a state in which the unopposed vagal influence causes bradycardia.

The tilt test is a practical diagnostic tool in patients with dysautonomia. When the orthostatic position is assumed, 500–800 mL of central volume is shifted to the periphery, resulting in a decrease in systolic volume and, consequently, cardiac output. Normally, this deficit is in turn sensed by the baroreceptors of the aortic arch and carotid sinus, which, after interaction with the vasomotor centers, elicit a response leading to a decrease in parasympathetic activity and an increase in sympathetic activity, resulting in peripheral vasoconstriction and increased heart rate. In our case, the tilt-test procedure demonstrated the absence of baroreflex sensitivity in the horizontal dorsal decubitus during the study period and in orthostasis.

The main goal in the initial management of neurogenic shock is hemodynamic stability. The first line of treatment for hypotension consists of intravenous fluid resuscitation, which aims at the vasogenic component typically observed in a neurogenic shock. The second line of treatment amounts to the use of vasopressors and inotropes, which changes the force of the heart’s contractions, enhancing the force of the heartbeat. These medications are used when the hypotension remains even after euvolemia. Phenylephrine, a pure alpha-1 agonist, is frequently used to induce peripheral vasoconstriction and lessen the lack of sympathetic activity. Another important pillar of neurogenic shock management consists of prevention. The patients with this condition should stay well hydrated, minimize abrupt movements and adhere to prescribed medications such as sympathomimetics.

A distinctive feature of our case, as mentioned earlier, is the severing of an important sympathetic chain by the surgical procedure, as evidenced by the lack of baroreceptor response, leading to recurrent severe neurogenic shock.

Conclusions

This case is an example that the diagnosis of neurogenic shock, which was not initially thought of, should be considered a reasonable hypothesis in patients with similar conditions. Immediate implementation of therapeutic measures may reduce additional risks and costs in the management of postoperative complications associated with pancreatoduodenectomy with complete removal of the mesopancreas. To our knowledge, this is the only reported case evidencing recurrent neurogenic shocks in the postoperative period of curative oncological surgery for pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the patient and her family for willing to share their experience.

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee from Sírio-Libanês Hospital and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Footnotes

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the CARE reporting checklist. Available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-23-494/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://gs.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/gs-23-494/coif). The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Oettle H, Neuhaus P, Hochhaus A, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine and long-term outcomes among patients with resected pancreatic cancer: the CONKO-001 randomized trial. JAMA 2013;310:1473-81. 10.1001/jama.2013.279201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ratnayake B, Savastyuk AY, Nayar M, et al. Recurrence Patterns for Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma after Upfront Resection Versus Resection Following Neoadjuvant Therapy: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 2020;9:2132. 10.3390/jcm9072132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Imamura M, Nagayama M, Kyuno D, et al. Perioperative Predictors of Early Recurrence for Resectable and Borderline-Resectable Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:2285. 10.3390/cancers13102285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gockel I, Domeyer M, Wolloscheck T, et al. Resection of the mesopancreas (RMP): a new surgical classification of a known anatomical space. World J Surg Oncol 2007;5:44. 10.1186/1477-7819-5-44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaedcke J, Gunawan B, Grade M, et al. The mesopancreas is the primary site for R1 resection in pancreatic head cancer: relevance for clinical trials. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2010;395:451-8. 10.1007/s00423-009-0494-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandes ESM, Strobel O, Girão C, et al. What do surgeons need to know about the mesopancreas. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2021;406:2621-32. 10.1007/s00423-021-02211-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talathi SS, Zimmerman R, Young M. Anatomy, Abdomen and Pelvis, Pancreas. [Updated 2023 Apr 5]. Treasure Island, FL, USA: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutchings C, Phillips JA, Djamgoz MBA. Nerve input to tumours: Pathophysiological consequences of a dynamic relationship. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 2020;1874:188411. 10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ni B, Yin Y, Li Z, et al. Crosstalk Between Peripheral Innervation and Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Neurosci Bull 2023;39:1717-31. 10.1007/s12264-023-01082-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haigh PI, Bilimoria KY, DiFronzo LA. Early postoperative outcomes after pancreaticoduodenectomy in the elderly. Arch Surg 2011;146:715-23. 10.1001/archsurg.2011.115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paiella S, De Pastena M, Pollini T, et al. Pancreaticoduodenectomy in patients ≥ 75 years of age: Are there any differences with other age ranges in oncological and surgical outcomes? Results from a tertiary referral center. World J Gastroenterol 2017;23:3077-83. 10.3748/wjg.v23.i17.3077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong D, Zhao M, Zhang J, et al. Neurolytic Splanchnic Nerve Block and Pain Relief, Survival, and Quality of Life in Unresectable Pancreatic Cancer: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Anesthesiology 2021;135:686-98. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machado MA, Mattos BV, Lobo Filho MM, et al. Mesopancreas Excision and Triangle Operation During Robotic Pancreatoduodenectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 2021;28:8330-4. 10.1245/s10434-021-10412-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Selvaggi F, Melchiorre E, Casari I, et al. Perineural Invasion in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma: From Molecules towards Drugs of Clinical Relevance. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:5793. 10.3390/cancers14235793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shyr BU, Shyr BS, Chen SC, et al. Mesopancreas level 3 dissection in robotic pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surgery 2021;169:362-8. 10.1016/j.surg.2020.07.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocha EA, Mehta N, Távora-Mehta MZP, et al. Dysautonomia: A Forgotten Condition - Part II. Arq Bras Cardiol 2021;116:981-98. 10.36660/abc.20200422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]