Abstract

This article discusses the growing burden of smog in Pakistan, tracing its origins to vehicular emissions, industrial pollutants, and agricultural practices. It highlights current national initiatives and advocates for enhanced government interventions to mitigate smog's adverse effects on ocular health. It also emphasizes the need for collective action to safeguard ocular health amid rising smog pollution in Pakistan.

Keywords: Smog, Ophthalmological health, Air pollution, Pakistan, Policy initiatives, Environmental health

In 2015, a study published in The Lancet estimated that approximately 135,000 individuals in Pakistan lost their lives due to air pollution [1]. Smog, a combination of various pollutants suspended in the air, poses a significant health threat to Pakistani society, particularly affecting respiratory and ophthalmological health [2]. The industrialization of major cities, outdated agricultural practices, and the poor quality of vehicle fuel and engines contribute to the persistence of smog from October to February each year [3]. This article discusses the causes and consequences of smog and highlights the critical need for long-term policies to mitigate its impact on ophthalmological health.

Factors contributing to smog in Pakistan

Pakistan's air quality faces numerous challenges [4], including emissions from industries, improper waste disposal, agricultural practices, and vehicle exhaust. Stubble burning emits large quantities of carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx), carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), and particulate matter (PM). Approximately 63 million tonnes of crop stubble burned annually result in the release of 3.4 million tonnes of CO, 0.1 million tonnes of NOx, 91 million tonnes of CO2, 0.6 million tonnes of CH4, and 1.2 million tonnes of PM into the atmosphere [4]. Additionally, the lack of adequate public transportation has increased motor vehicle usage, with an estimated 10 million vehicles worsening the air quality over the past two decades [5].

Poor urban planning and unchecked economic growth have exacerbated pollution, leading to elevated levels of PM2.5, which significantly surpasses the World Health Organization (WHO)’s recommended annual limit of 10 μg/m3. Exposure to such levels has been linked to severe health burdens, highlighting the urgency of addressing air pollution in Pakistan [6].

Impact of smog on ophthalmological health

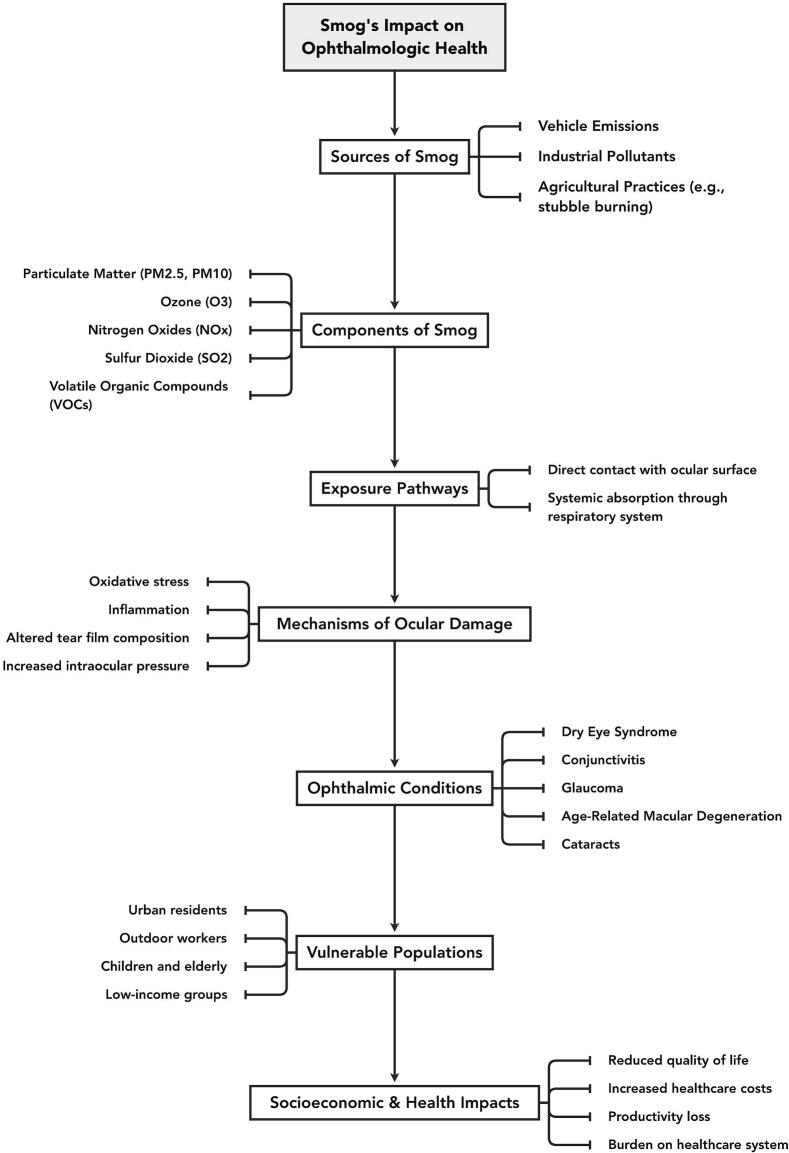

PM, ground-level ozone (O3), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), and sulfur dioxide (SO2) in smog have all been linked to various eye diseases [5,6]. Smog has led to a rise in ocular surface diseases, affecting structures such as the cornea, conjunctiva, sclera, and tear film. Studies in Pakistan have reported symptoms like itching, watering, and burning in cases of dry eye disease (DED), which significantly impacts quality of life. These conditions arise from various factors, including inflammation, immune reactions, oxidative stress, and epigenetics [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12], [13], [14]]. Fig. 1 depicts a flowchart illustrating the several mechanisms through which smog impacts ophthalmological health.

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms by which smog affects ophthalmological health.

Lahore, the capital of Punjab, is Pakistan's second-largest city and has a population of over 14 million [15]. In October 2024, IQAir, the world's largest real-time air quality monitoring platform, reported a PM2.5 concentration in Lahore that was 102.4 times the WHO's annual air quality guideline value, with an air quality index (AQI) score of 1165, more than 120 times the level recommended by the WHO, ranking it as the world's most polluted city [16,17]. Cities like Faisalabad and Peshawar frequently follow with some of the worst AQI levels globally as well [[18], [19], [20]].

Findings from a 2016 case study in Lahore revealed that the level of NOx in the city was nearly 17 times higher than the baseline value. Other pollutants, such as SO2 and O3, were four times higher, while CO, VOC, and PM2.5 were twice as high, and PM10 was six times higher than the baseline values. The study concluded that there was a 60 % increase in the number of patients reporting ocular surface diseases (including dry eyes, irritation, lid erosion, corneal diseases, conjunctival diseases, uveitis, and lacrimation) during the Lahore smog event compared to baseline conditions on the same day and month in 2015 [21]. Since 2016, smog has become a common and persistent phenomenon in Lahore, earning the nickname “the fifth season.” During this time, people living in cities such as Lahore, Faisalabad, and Multan are subjected to harmful levels of air pollution [22,23].

In a study conducted in Islamabad, common symptoms of DED included itching (155/191 cases, 81.2 %), watering (151/191 cases, 79.1 %), and burning (124/191 cases, 64.9 %), with watering and photophobia severely affecting daily activities [24]. During winter, a higher incidence of smog forces Pakistan's residents to restrict their occupational activities due to its adverse health impacts and restricted mobility caused by poor visibility [25]. Moreover, smog contributes to increased cases of conjunctival inflammation [21], commonly known as pink eye disease, which has become a significant health concern in Pakistan's major urban areas [26,27].

Smog has been linked to chronic ophthalmic diseases such as glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, and age-related macular degeneration (ARMD). Studies have found that pollutants like PM2.5 and NOx are associated with a higher risk of acute glaucoma, elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), earlier onset of childhood glaucoma, and a higher frequency of outpatient visits for glaucoma on days when the AQI indicates poor air quality [[28], [29], [30], [31]]. Similarly, high levels of PM pollution increase the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy; a population-based study in rural Pakistan reported a 24.2 % (563/2331) prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among individuals with diabetes [32]. Oxidative stress and inflammation, both aggravated by PM2.5 exposure, are linked to the pathophysiology of ARMD. [33] Since PM2.5 is directly correlated with increased oxidative stress [34], smog is associated with an increasing incidence, severity, and hastening progression of ARMD. Long-term exposure to hydrocarbons and high daily levels of PM10, NO2, SO2, O3, and CO can lead to presbyopia and other vascular eye diseases, further burdening Pakistan's healthcare system [[35], [36], [37]].

In Lahore, the air quality ranks among the most hazardous globally, yet its impact varies among residents [38]. High-income groups have a decreased risk of mortality from smog and heat-related events [39]. This reduced risk is attributed to their lower exposure to smog, as they can afford protective measures such as masks and air filters. [[38], [41] These groups are also more likely to engage in behaviors that reduce exposure to PM2.5 [42]. In contrast, low-income groups tend to have increased exposure and fewer protective behaviors, placing them at higher risk for the ophthalmological effects of smog. Additionally, individuals in low-income communities, especially in lower-middle-income countries like Pakistan, face greater complications due to limited access to healthcare [43].

Policy initiatives and recommendations

Beijing offers valuable insights for Pakistan to mitigate the effects of smog. Wang et al. distinguished Beijing's air pollution as haze rather than smog, highlighting coal power plants as a major anthropogenic pollution source [44]. Their comparison with London highlights the shared reliance on coal for power generation, particularly for winter heating, and the significant air pollution resulting from rapid economic development. In the 1990s, coal combustion accounted for 87 % of SO₂ emissions and 76 % of NOₓ emissions in China [45]. Beijing's success in tackling air pollution was largely due to policies that phased out coal power plants, along with temporary traffic controls that reduced pollutants significantly [46]. Implementation of the 2013 five-year action plan, Beijing's Battle to Clean Up its Air, saw the city's smog control budget grow from USD 434 million to USD 2.6 billion between 2013 and 2017, resulting in notable reductions in NO₂, SO₂, and PM2.5 levels [47,48].

Pakistan's government has taken similar initiatives and implemented policy changes to mitigate its impacts and improve air quality. The revised Pakistan Clean Air Plan (PCAP), announced by Pakistan's Ministry of Climate Change with the support of the Asian Development Bank in 2021 [49,50] led to the development of the country's first national air pollutant inventory, quantifying black carbon and other airborne pollutants at both the national and provincial levels. The ongoing PCAP encompasses a National Clean Air Plan with three primary goals: establishing air pollution concentration targets, identifying effective strategies for mitigating air pollution, and developing a coordinated action plan for air quality improvement [51].

The Government of Punjab (GoP) has also implemented smart lockdowns in various districts to curb rises in worsening air quality indexes [52]. These measures include reducing working days and hours, closing markets and restaurants earlier, and closing educational institutions on certain days of the week. The government has also been implementing air quality monitoring systems to track pollution levels and assess the effectiveness of control measures [53]. In 2023, the GoP declared a month-long smog emergency. Measures such as enforcing water sprinkling on construction sites, banning smoke-emitting vehicles, and sealing polluting factories were implemented [54]. Yet, the AQI continues to range in dangerous levels each year exposing inhabitants of Pakistan to air pollutants each year.

Given the significant impact of smog on ophthalmological health, the current government efforts in Pakistan need further strengthening. The lessons learned from Beijing's approach, such as large-scale policy implementation, stricter regulations on coal emissions, and proactive traffic management, could be effectively applied in the Pakistani context to mitigate smog's effects. However, the need for ongoing research into the specific ocular effects of smog is crucial. It will help to refine public health strategies, guiding policies that prioritize reducing exposure to harmful air pollutants, enhancing environmental integrity, and protecting citizens' health. To achieve these goals, Pakistan requires increased awareness, stronger policies, and dedicated research efforts focused on smog and its long-term health impacts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Zoya Ejaz: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization. Faizan Masood: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation. Arsalan Nadeem: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology. Abdullah Ahmed: Writing – original draft, Methodology. Eeman Ahmad: Writing – original draft, Methodology. Mahrukh Chaudhry: Writing – original draft.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Cohen A.J., Brauer M., Burnett R., et al. Estimates and 25-year trends of the global burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution: an analysis of data from the Global Burden of Diseases Study 2015. The Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1907–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30505-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grzywa-Celińska A., Krusiński A., Milanowski J. “Smoging kills” - Effects of air pollution on human respiratory system. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2020;27(1):1–5. doi: 10.26444/aaem/110477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashraf M.F., Ahmad R.U., Tareen H.K. Worsening situation of smog in Pakistan: A tale of three cities. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022;79 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toxic heavy smog in eastern Pakistan makes tens of thousands sickAP News. 2023 https://apnews.com/article/pakistan-smog-school-markets-shut-pollution-2b752ee29d1be2b8c93ec8bd5a81bf62 Accessed October 12, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Photochemical Smog - an overviewScienceDirect Topics. 2024 https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/earth-and-planetary-sciences/photochemical-smog Accessed June 8, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Millen A.E., Dighe S., Kordas K., Aminigo B.Z., Zafron M.L., Mu L. Air pollution and chronic eye disease in adults: a scoping review. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2024;31(1):1–10. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2023.2183513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Song F., Hao S., Gu Y., Yao K., Fu Q. Research advances in pathogenic mechanisms underlying air pollution-induced ocular surface diseases. Adv Ophthalmol Pract Res. 2021;1(1) doi: 10.1016/j.aopr.2021.100001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Somayajulu M., Ekanayaka S., McClellan S.A., et al. Airborne particulates affect corneal homeostasis and immunity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2020;61(4):23. doi: 10.1167/iovs.61.4.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jung S.J., Mehta J.S., Tong L. Effects of environment pollution on the ocular surface. Ocul Surf. 2018;16(2):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pandey P., Patel D.K., Khan A.H., Barman S.C., Murthy R.C., Kisku G.C. Temporal distribution of fine particulates (PM₂.₅:PM₁₀), potentially toxic metals, PAHs and Metal-bound carcinogenic risk in the population of Lucknow City, India. J Environ Sci Health A Tox Hazard Subst Environ Eng. 2013;48(7):730–745. doi: 10.1080/10934529.2013.744613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J., Man R., Ma S., Li J., Wu Q., Peng J. Atmospheric levels and health risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) bound to PM2.5 in Guangzhou, China. Mar Pollut Bull. 2015;100(1):134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qi H., Liu Y., Wang N., Xiao C. Lentinan attenuated the PM2.5 exposure-induced inflammatory response, epithelial-mesenchymal transition and migration by inhibiting the PVT1/miR-199a-5p/caveolin1 pathway in lung cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 2021;40(5):683–693. doi: 10.1089/dna.2020.6338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niu L., Li L., Xing C., et al. Airborne particulate matter (PM2.5) triggers cornea inflammation and pyroptosis via NLRP3 activation. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;207 doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu Y., Li M., Tian Y., et al. Short-term effects of ambient fine particulate air pollution on inpatient visits for myocardial infarction in Beijing, China. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26(14):14178–14183. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahore, Pakistan Population. 2024. https://worldpopulationreview.com/cities/pakistan/lahore Accessed November 7, 2024.

- 16.Lahore Air Quality Index (AQI) and Pakistan Air Pollution | IQAir. 2024. https://www.iqair.com/pakistan/punjab/lahore Accessed November 7, 2024.

- 17.How is Lahore, the world's most polluted city, battling toxic air? Reuters. 2024 https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/how-is-lahore-worlds-most-polluted-city-battling-toxic-air-2024-11-06/ Accessed November 7, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashraf M.F., Ahmad R.U., Tareen H.K. Worsening situation of smog in Pakistan: A tale of three cities. Ann Med Surg. 2022;79 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Faisalabad Air Quality Index (AQI) and Pakistan Air Pollution | IQAir. 2024. https://www.iqair.com/pakistan/punjab/faisalabad Accessed November 7, 2024.

- 20.Peshawar Air Quality Index (AQI) and Pakistan Air Pollution | IQAir. 2024. https://www.iqair.com/ae/pakistan/khyber-pakhtunkhwa/peshawar Accessed November 7, 2024.

- 21.Ashraf A., Butt A., Khalid I., Alam R.U., Ahmad S.R. Smog analysis and its effect on reported ocular surface diseases: A case study of 2016 smog event of Lahore. Atmos Environ. 2019;198:257–264. doi: 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.10.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan W.A., Sharif F., Khokhar M.F., Shahzad L., Ehsan N., Jahanzaib M. Monitoring of ambient air quality patterns and assessment of air pollutants’ correlation and effects on ambient air quality of Lahore, Pakistan. Atmosphere. 2023;14(8):1257. doi: 10.3390/atmos14081257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Majeed R., Anjum M.S., Imad-ud-din M., et al. Solving the mysteries of Lahore smog: the fifth season in the country. Front Sustain Cities. 2024:5. doi: 10.3389/frsc.2023.1314426. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arif S.A., Khan M.I., Abid M.S., et al. Frequency and impact of individual symptoms on quality of life in dry eye disease in patients presenting to a tertiary care hospital. J Pak Med Assoc. 2021;71(4):1063–1068. doi: 10.47391/JPMA.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Atmosphere | Free Full-Text | Assessing Health Impacts of Winter Smog in Lahore for Exposed Occupational Groups. 2024. https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4433/12/11/1532 Accessed June 8, 2024.

- 26.Bowman V. Mass outbreak of ‘pink eye’ closes 56,000 schools in Pakistan. Telegraph. 2023 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/science-and-disease/pakistan-eye-infection-viral-conjunctivitis-outbreak-punjab/ Accessed June 8, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaudhry I.G. A. 86,133 pink eye cases in Punjab in September and counting. DAWN.COM. 06:59:08+05:00. 2024. https://www.dawn.com/news/1778214 Accessed June 8, 2024.

- 28.Li L., Zhu Y., Han B., et al. Acute exposure to air pollutants increase the risk of acute glaucoma. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1782. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14078-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chua S.Y.L., Khawaja A.P., Morgan J., et al. The relationship between ambient atmospheric fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and glaucoma in a large community cohort. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2019;60(14):4915–4923. doi: 10.1167/iovs.19-28346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grant A., Leung G., Aubin M.J., Kergoat M.J., Li G., Freeman E.E. Fine particulate matter and age-related eye disease: the canadian longitudinal study on aging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2021;62(10):7. doi: 10.1167/iovs.62.10.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Min K.B., Min J.Y. Association of ambient particulate matter exposure with the incidence of glaucoma in childhood. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;211:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2019.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jokhio A.H., Talpur K.I., Shujaat S., Talpur B.R., Memon S. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in rural Pakistan: A population based cross-sectional study. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2022;70(12):4364–4369. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_126_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ju M.J., Kim J., Park S.K., Kim D.H., Choi Y.H. Long-term exposure to ambient air pollutants and age-related macular degeneration in middle-aged and older adults. Environ Res. 2022;204(Pt A) doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2021.111953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jarrett S.G., Boulton M.E. Consequences of oxidative stress in age-related macular degeneration. Mol Aspects Med. 2012;33(4):399–417. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grzybowski A.E., Mimier M.K. Evaluation of the association between the risk of central retinal artery occlusion and the concentration of environmental air pollutants. J Clin Med. 2019;8(2):206. doi: 10.3390/jcm8020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang H.W., Lin C.W., Kok V.C., et al. Incidence of retinal vein occlusion with long-term exposure to ambient air pollution. PloS One. 2019;14(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kazmi S., Jabeen A., Gul R. Rising glaucoma burden in Pakistan: A wake-up call for nationwide screening? J Pak Med Assoc. 2022;72(5):1016. doi: 10.47391/JPMA.3722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashim A. In ‘Smog-istan’, not all Pakistanis are created equal. Al Jazeera. 2024 https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2020/1/23/in-smog-istan-not-all-pakistanis-are-created-equal Accessed November 7, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willers S.M., Jonker M.F., Klok L., et al. High resolution exposure modelling of heat and air pollution and the impact on mortality. Environ Int. 2016;89–90:102–109. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan Y., Fan B. Protective consumption behavior under smog: using a data-driven dynamic Bayesian network. Environ Dev Sustain. 2024;26(2):4133–4151. doi: 10.1007/s10668-022-02875-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu S., Chiang Y.T., Tseng C.C., Ng E., Yeh G.L., Fang W.T. The theory of planned behavior to predict protective behavioral intentions against PM2.5 in parents of young children from urban and Rural Beijing, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(10):2215. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15102215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters D.H., Garg A., Bloom G., Walker D.G., Brieger W.R., Rahman M.H. Poverty and access to health care in developing countries. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1136:161–171. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang K., Liu Y. Can Beijing fight with haze? Lessons can be learned from London and Los Angeles. Nat Hazards. 2014;72(2):1265–1274. doi: 10.1007/s11069-014-1069-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Almond D., Chen Y., Greenstone M., Li H. Winter heating or clean air? Unintended impacts of china’s huai river policy. Am Econ Rev. 2009;99(2):184–190. doi: 10.1257/aer.99.2.184. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jin Y., Andersson H., Zhang S. Air pollution control policies in China: a retrospective and prospects. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13(12):1219. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13121219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tajammul K.I. Critical review and comparative analysis of the government of Punjab’s ‘Policy on controlling smog, 2017’ with counterpart strategies in London, Beijing and Los Angeles. J Dev Policy Res Practice (JoDPRP) 2023:181–202. doi: 10.59926/jodprp.vol07/09. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Environment UN . 2024. BeatAirPollution: Beijing’s battle to clean up its air.https://www.unenvironment.org/interactive/beat-air-pollution/ Accessed November 7, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bank AD New Pakistan Clean Air Plan (PCAP) Announcement. 2021. https://www.adb.org/news/events/new-pakistan-clean-air-plan-pcap-announcement Accessed June 8, 2024.

- 50.PAKISTANCLEANAIRPROGRAMME.pdf. 2024. https://environment.gov.pk/SiteImage/Misc/files/Downloads/interventions/environmentalissues/PAKISTANCLEANAIRPROGRAMME.pdf Accessed June 8, 2024.

- 51.Can the Clean Air Plan clean up Pakistan’s air quality? 2024. https://www.iqair.com/newsroom/pakistan-clean-air-act Accessed June 8, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smart lockdown implemented in 10 Punjab districts as a countermeasure against rising smog levels. 2023. https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2023/11/24/smart-lockdown-implemented-in-10-punjab-districts-as-a-countermeasure-against-rising-smog-levels/ Accessed June 8, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Annex D2 Punjab Clean Air Action Plan_0.pdf. 2024. https://epd.punjab.gov.pk/system/files/Annex%20D2%20Punjab%20Clean%20Air%20Action%20Plan_0.pdf Accessed June 8, 2024.

- 54.Naveed A. Punjab declares smog emergency. Express Tribune. 2023 https://tribune.com.pk/story/2444194/punjab-declares-smog-emergency Accessed June 8, 2024. [Google Scholar]