Abstract

Ectopic pregnancy is a gynaecological emergency. While its identification and management are monumental, it also impacts the patient’s future fertility. Ectopic pregnancy is one of the leading causes for maternal deaths in the first trimester. The rate of ectopic pregnancy in the United Kingdom is reported to be 11 per 1000 pregnancies, with a maternal mortality of 0.2 per 1000 estimated ectopic pregnancies and two-thirds of these deaths are associated with substandard care. Literature is replete with risk factors leading to ectopic pregnancy, such as tubal disease, previous pelvic surgery, tubal surgery, assisted reproduction, smoking and so on. The paper employs case scenarios of recurrent ectopic pregnancies in two patients with triple recurrent ecotpic pregnacies. It discusses the risk factors and preventive measures to avoid multiple recurrences.

Keywords: Recurrent ectopic, risks of recurrent

Introduction

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is a gynaecological emergency with implications on future fertility. We present two patients with occurrence of three recurrent ectopic pregnancies (REPs) in each. This is followed by a literature review of risk factors of incidence of REPs and to address preventive measures to avoid multiple recurrences.

Case reports

Case report 1

The first patient is a 32-year-old housewife (G6, P1+4) with a history of three ectopic pregnancies. She has had six pregnancies; the first pregnancy resulted in ventouse delivery of a female infant at term. She then had three consecutive ectopic pregnancies and two first-trimester miscarriages. She attained menarche at age 17 and had a regular menstrual cycle of 4/30 days with no history of dysmenorrhea, inter-menstrual or post-coital bleeds. She was up-to-date with her cervical screening with normal cytology. She has denied any history of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). However, previous laparoscopic examinations revealed features consistent with pelvic infection (pelvic and peri-hepatic adhesion consistent with Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome). She was not on any contraceptive and was a non-smoker with allergies to penicillin.

First EP

This occurred at age 22 when she was gravida 2 para 1 (3-year-old baby). She presented with a triad of 7-week amenorrhoea, abdominal pain and 16 days of vaginal bleeding with clots. The β-hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) was 734iu/L, and she was haemodynamically stable. The abdomen was tender, with minimal vaginal bleeding, closed cervix and reflex excitation tenderness was elicited. A transvaginal ultrasound scan demonstrated a right adnexal irregular complex mixed echo mass measuring 66 × 88 × 88 mm and significant free fluid in the Pouch of Douglas (POD). Within 24 hours of admission, she began to show signs of a rupture, including tachycardia and hypotension. Haemoperitoneum (500ml), a right spontaneous tubal miscarriage and bilateral tubal adhesion were noted at laparoscopy. Peritoneal lavage was performed, and the tubal abortus was retrieved and sent for histology. A right tubal EP diagnosis with spontaneous tubal miscarriage and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) was made. Histology confirmed products of conception from the fimbrial end of the right fallopian tube. She required two units of blood transfusion and postoperative antibiotics. Serum β-hCG on the fifth postoperative day was 36 IU/L. Five months later, a planned interval laparoscopy, adhesiolysis, salpingolysis, and methylene blue tubal insufflation revealed peri-hepatic violin string adhesions, minimal para-tubal adhesions and minimal adhesions in POD. Adhesiolysis resulted in a normal uterus, ovaries, and free and bilaterally patent fallopian tubes on methylene blue insufflation

Second EP

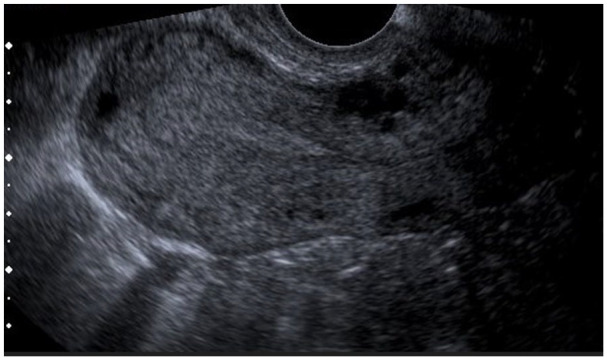

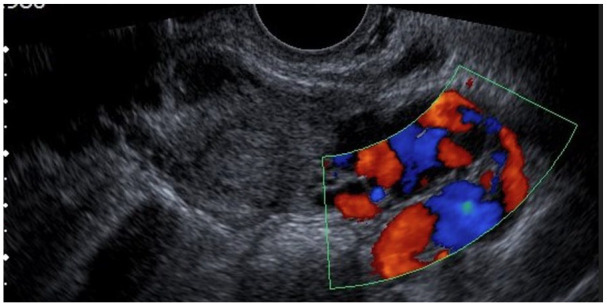

Her subsequent pregnancy was at age 26 (G4 para 1) in her fifth pregnancy, having had one miscarriage at 6 weeks’ gestation. She presented with left-sided abdominal pain, mild vaginal bleeding and collapse. Given previous EP, tubal surgery and PID, EP was suspected. Clinically, there was guarding and rebound tenderness, and pelvic assessment revealed minimal vaginal bleeding, bulky uterus, closed cervical os, and left adnexal and excitation tenderness. The urine pregnancy test was positive, and the serum β-hCG was 1588 IU/L (result obtained after her emergency operation). The ultrasound scan showed no evidence of intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), no free fluid in the POD or adnexal masses. However based on a thickened endometrium and guided by high suspicion due to the previous history of ectopic and PID, the patient was taken for diagnostic laparoscopy (see Figures 1 and 2). Laparoscopy revealed a left ampullary EP (see Figure 3) with a normal right tube and normal ovaries. Laparoscopic left salpingectomy was performed, and the postoperative period was uneventful. EP was confirmed on histology. She was counselled for recurrence risk and advised about self-referral to the early pregnancy assessment unit (EPAU) in her subsequent pregnancy.

Figure 1.

Thickened endometrium, no intrauterine pregnancy.

Figure 2.

No free fluid in POD.

Figure 3.

Left ampullary ectopic pregnancy.

Third EP

Six months later, she presented to the EPAU for an early ultrasound scan assessment because of a history of asymptomatic amenorrhoea and serum β-hCG of 1359 IU/L. Transvaginal scan (TVS) showed no evidence of IUP and endometrial thickness (ET) of 11 mm, and she was managed expectantly. The β-hCG was 2424 IU/L after 48 hours, representing a rise of 56%. She later became symptomatic at home with vaginal bleeding and abdominal pain. A repeat TVS was inconclusive. Laparoscopy showed an unruptured right tubal EP (see Figure 4), some haemoperitoneum, Fitz-Hugh–Curtis syndrome and an absent left fallopian tube. She underwent laparoscopic salpingectomy.

Figure 4.

Right unruptured tubal ectopic pregnancy.

Case report 2

In our second case, we present a 27-year-old lady. She is G3, P0 with history of three previous miscarriages and investigations for primary sub-fertility. She also had a past medical history of having an intrauterine contraceptive device and PID with numerous antibiotic therapies. She had three previous laparoscopies and adhesiolysis for chronic PID. She was allergic to plaster.

First EP

She presented with her first EP when she had a 3-day history of brownish vaginal discharge and lower abdominal pain. She was unsure of her dates but thought it was less than 4 weeks and had a negative urine pregnancy test, but a faintly positive test on admission. Clinically, the abdomen was tender in the right iliac fossa. Brownish vaginal discharge and closed cervical os were revealed at a vaginal examination. There was bilateral reflex cervical excitation tenderness. The ultrasound scan showed a bulky uterus, thickened endometrium and no evidence of in utero pregnancy. At laparoscopy, a haemoperitoneum and a right tubal mass measuring 3 × 2 cm with bilateral florid tubo-ovarian adhesive complex was revealed. At laparotomy, the right tube was incised, the pregnancy was evacuated and haemostasis was achieved with diathermy and the tube was closed with continuous nylon suture (open salpingostomy). EP was confirmed in histology.

Second EP

Five months later, at age 28+, she presented with amenorrhoea, jelly-like, brownish vaginal discharge and abdominal discomfort. Her periods were irregular lasting 2–3 days and occurring every 4–6 weeks. There was accompanied dyspareunia and she was not on any contraception. A home pregnancy test was negative. An abdominopelvic examination was unremarkable as well as a pelvic ultrasound scan. She was discharged home for a follow-up. She returned 13 days later to the hospital with suprapubic pain, brownish vaginal discharge and a positive pregnancy test. On examination, the abdomen was tender with guarding and rebound phenomena in the upper right abdomen. An ultrasound showed no evidence of IUP but a right adnexal mass. She underwent a laparoscopy and laparotomy and right salpingectomy. At operation, there was 100 mL of haemoperitoneum and a right tubal EP, measuring 6 × 3 cm and the left tube was normal. The histology confirmed ectopic.

Third EP

This occurred at age 33, now gravida 8, para 2, with two ectopic pregnancies and four miscarriages. The main complaint at the EPAU was a slight left iliac fossa (LIF) discomfort, no bleeding, a regular cycle following 6 weeks of amenorrhoea and a positive urine pregnancy test. She was managed expectantly initially. The ultrasound scan showed no IUP and an ET of 13.2 mm and serum β-hCGs were 443 IU/L, 539 IU/L, 731 IU/L on admission and at 48 and 96 hours, respectively. On review in the EPAU on the fifth day, she had brownish vaginal discharge and bleeding and increased lower abdominal pain, especially in the LIF and β-hCG of 731 IU/L. Due to high clinical suspicion, patient symptoms and sub-optimal HCG rise, she underwent a laparoscopy. A left cornual ectopic 3 × 3 cm was noted and a resection was performed at laparotomy. She was discharged home on the second day of the operation. She returned about 4 years later with history of further pain and underwent adhesiolysis secondary to multiple laparoscopic surgeries.

A summary of both case reports with age at presentation, order of presentation, site of ectopic and intervention is provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of ectopic pregnancy event and intervention in both case reports.

| Events | Case 1 | Case 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years | Intervention | Intervals | Age in years | Intervention | Intervals | |

| First | 22 | Right laparoscopic milking | 27 | Laparoscopy and laparotomy and right salpingotomy | ||

| Second | 26 | Left laparoscopic salipingectomy | 4 years | 28 | Laparoscopy, laparotomy and right salpingectomy | 6 months |

| Third | 27 | Right laparoscopic salpingectomy | 6 months | 33 | Laparoscopy, laparotomy and left cornual resection | 5 years |

| Risk factors | Evidence of PID at the first laparoscopy | Primary infertility, previous use of IUCD, chronic PID, laparoscopic adhesiolysis, smoker |

||||

PID: pelvic inflammatory disease; IUCD: intrauterine contraceptive device.

Discussion and literature review

Incidence of EP and REP

The rate of EP in the United Kingdom is reported to be 11 per 1000 pregnancies,1,2 with a maternal mortality of 0.2 per 1000 estimated ectopic pregnancies.3,4 Incidence of REP varies from 10% to 27%5,6 representing a 5- to 15-fold increase in the general population. 5 The recurrence rate of ectopic is represented in Table 2. The trend of EP in our unit is given in Table 3. Most (93%) of the ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tube, and only 10% account for occurrence in non-tubal sites such as adnexa, ovary, intramural or cornual. Of these, 70% are in the ampulla, 12% in the isthmus and 11% in the fimbriae. 2 Non-tubal ectopic pregnancies are often referred to as unusual site ectopic pregnancies (see Table 4). They occur in about 7% pregnancies and account for significantly higher morbidity and mortality as they are more difficult to diagnose and tend to present later than tubal pregnancies.

Table 2.

| No previous EP | 1%–3% |

| Recurrence of EP after one previous EP | 10-15% |

| Recurrence of EP after two previous EPs | 27% |

| Recurrence of EP following one salpingotomy for EP on ipsilateral tube | 15.4%

10

(15% persistent EP) |

EP: ectopic pregnancy.

Table 3.

Trend of ectopic pregnancy in Diana Princess of Wales Hospital. 1

| Triennium | Total ectopic pregnancies | Ectopic: delivery ratio | Ectopic pregnancies per 1000 pregnancies (rate) |

No of deaths from ectopic pregnancies | Death rate /1000 estimated ectopic pregnancies |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit | UK | Unit | UK | UK | UK | |

| 1994–1996 | 46 | 33,550 | 1:130 | 11.5 | 12 | 0.358 |

| 1997–1999 | 38 | 31,946 | 1:173 | 11.1 | 13 | 0.407 |

| 2000–2002 | 55 | 30,100 | 1:109 | 11.0 | 11 | 0.365 |

| 2003–2005 | 57 | 32,100 | 1:117 | 11.1 | 10 | 0.312 |

| 2006–2008 | 56 | 35,496 | 1:132 | 11.3 | 6 | 0.169 |

| 2009–2011 | 72 | 37,650 | 1:526 | 11.0 | 2014 Cemace has early pregnancy mortality. Individual rate of mortality from ectopic pregnancy is not available | |

Unit: Northern Lincolnshire and Goole Hospitals, NHS Foundation Trust, Diana, Princess of Wales Hospital, Grimsby, UK.

Table 4.

Non-tubal ectopic pregnancy (adapted from Bolaji et al. 2 ).

| Term | Definitions | Incidence | Importance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interstitial pregnancy a | The implantation of the conceptus within the interstitial portion of the fallopian tube which is surrounded by the muscular wall of the uterus 11 | 2% to 6% of all ectopic pregnancies | Account for almost a fifth of all deaths caused by ectopic pregnancies due to haemorrhage 12 |

| Cornual pregnancy | The implantation of a blastocyst within the cornua of a bicornuate or septate uterus | Less than 1% of all ectopic pregnancies 13 | Rupture of cornual pregnancy may happen at later gestations and therefore results in catastrophic haemorrhage |

| Cervical pregnancy a | The implantation of the conceptus within the cervix, below the level of internal os | Less than 1% of all ectopic pregnancies | Could be difficult to distinguish from cervical phase of miscarriage |

| Caesarean section scar ectopic | Implantation into myometrium of a deficient uterine caesarean section scar | 1: 1800–2200 pregnancies 14 | Those that progress into the third trimester are likely to be complicated by placenta previa/accrete 15 |

| Ovarian pregnancy | Means implantation on the surface or inside the ovary | Around 0.5%–6.0% of all ectopic pregnancies 16 | They are notoriously difficult to diagnose by ultrasound |

| Abdominal pregnancy | The implantation of the conceptus within the peritoneal cavity excluding the uterus, ovaries or fallopian tubes | Around 1% of ectopic pregnancies | Could be either primary, that is, pouch of douglas, bowel or omentum, or secondary, that is, originating as tubal pregnancies which then reimplant inside the abdomen 17 |

Cervical and interstitial pregnancies are the most common form of ectopic pregnancies following artificial reproductive technology treatment.

Clinical presentation

The classic triad of symptoms are abdominal pain, amenorrhea and vaginal bleeding, which occur in only 50% of patients with index and REP. 6 In clinical presentation, the first case displayed the classic symptoms of EP, which are also the same for REP. Similar case reports of REP in patients from India and Iran supported this presentation.6,18 However, in our case reports, the second case presented with brownish vaginal discharge as opposed to vaginal bleeding, which must be noted to avoid its exclusion from clinical diagnostic criteria. Hence, (lower) abdominal pain and delayed menstrual bleeding should be the two most important features to make a differential diagnosis of an index or REP.

There is a tendency for REP to more likely present at an earlier gestation, with a lower β-hCG level and less haemoperitoneum. The earlier gestation presentation is attributable to the robust safety netting and patient education on the risk of recurrence. Therefore, offering ultrasound at very early gestation could be a confounding factor. 7

Risk factors

The main risk factors for EP are tubal damage by pelvic infection or surgery, smoking, assisted reproduction3,4,19 and other reproductive tract procedures that is use of intrauterine device (IUD) at conception. 4 Although identified risk factors for REP are previous occurrence of EP and abnormal anatomy of fallopian tube other definitive causes and risk factors remain unclear. 6 Understanding the risk factors of REP will help caregivers with the opportunity to counsel and evaluate patients and offer management options accordingly.

As per some case–control and cohort studies, Table 5 demonstrates a list of the summary of the risk factors for primary EP (PEP) versus risk factors for REP in Table 6. In theory, all risk factors for PEP should account for recurrence as well. A conspicuous risk factor noted in REP was history of previous tubal surgery or previous pelvic surgery. 5 One study proposed that history of PID was seen in both REP and PEP but, significant number of patients with REP had pelvic and peritubal adhesions. 19 They have inferred that this may suggest a substantial element of under diagnosis and treatment of PID. Hence, effective treatment of PID has its implications of PEP and thereby REP. In a case–control study that assessed subsequent REP pregnancies, patients who had two previous ectopic pregnancies by natural conception and treated with salpingectomy or salpingostomy were found to have a 10-fold increased risk of further REP as compared to those with one prior. 19 The same study findings revealed that compared to the patients in the PEP group, REP patients had significantly lower education (p = 0.001), higher proportion of previous infertility (p < 0.001) and significantly higher occurrences of pelvic and peritubal adhesions (p < 0.05). Further multiple regression analysis showed that lower educational background, nulliparity, history of salpingotomy were significant risk factors for REP. 5

Table 5.

Table 6.

| Low annual income

5

Lower educational background 19 |

| Lack of contraception 19 |

| Consanguinity20,23 |

| Higher gravidity, previous miscarriage, higher number of previous abortions, previous dilatation and curettage, previous evacuation of retained products of conception3,5,20,21 |

| Nulliparity, history of infertility or tubal infertility 19 |

| Previous adnexal surgery or salpingotomy for previous EP 21 |

| Pelvic adhesions noted at the time of primary ectopic management5,19 |

| Tubal damage by pelvic infection, for example, Chlamydia trachomatis and salpingitis, pelvic surgery5,21,24 |

| Previous medical management (e.g. methotrexate treatment) for previous EP 22 |

| Late diagnosis of previous EP and developing complications 22 |

EP: ectopic pregnancy.

Management of REP

Management options for REP are like that of PEP. The choice could invariably depend on the management method employed in managing primary ectopic and the patient’s choice. Options include expectant, medical and surgical management, such as salpingostomy, fimbrial milking and salpingectomy. A retrospective cohort study showed a higher incidence of REP with medical management than with interventional management. 22 Among the surgical management, REP is more prevalent in the salpingostomy group than the salpingectomy group. 25 In a 5-year follow-up cohort study, salpingectomy when compared to salpingostomy, and laparoscopy when compared with laparotomy, were found to be associated with a lower risk of REP. 23 An extensive systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) has shown no significant difference in fertility prospective in salpingostomy compared with salpingectomy. 25 Where the contralateral tube is appearing healthy, salpingectomy is favoured over salpingostomy.3,25

Medical management with systemic methotrexate (MTX) represents an option for REP. However, there have been reports from a logistic regression analysis of study data of many patients with ectopic pregnancies treated with single-dose MTX. REP was the only independent variable found to be associated with treatment failure. Therefore, it is advisable to consider surgical options for managing REP 24 where feasible unless the risks of surgery are higher than medical management. The site of the ectopic, gestation at identification, patient symptoms and co-morbidities significantly impacts the clinical decisions followed by patient choice. As such, there is no delineated mode of management of REP, and patient risk factors, choice and clinical feasibility should guide clinicians. 16

Managing cornual ectopic

In total, 2%–4% of EPs are cornual, while less-common forms include cervical, ovarian and peritoneal. Cornual pregnancy refers to the implantation and development of a gestational sac in one of the upper and lateral portions of the uterus. Conversely, an interstitial pregnancy is a gestational sac that implants within the proximal, intramural portion of the fallopian tube that is enveloped by the myometrium. Diagnosis is often difficult because the implantation site is still intrauterine in the cornua or intrauterine portion of the fallopian tube. 26 Invasion through the uterine wall makes this pregnancy challenging to differentiate from an IUP on ultrasound. Because of their anatomical position, vascularity, risk of bleeding and incomplete resection, they are not always manageable surgically. Options around medical or surgical management are decisions made in light of gestation of diagnosis, HCG level and patient co-morbidities for surgery. Traditional cornual resection by laparotomy was an option. More conservative methods, such as cornuostomy by laparoscopy or laparotomy approach, are being performed with success 26 with or without injecting vasopressin to reduce blood loss. Medical management methods with an option of injecting intra-amniotic injection of potassium chloride (KCl) and then intra-placental injection of MTX had good success.27,28 Systemic MTX injection is another most common conservative treatment for managing early EP with a success rate of 91% and up to 66.7% in cornual ectopic.29,27

Recurrence in cornual ectopic are extremely rare and their exact figures are unknown. 29 The main etiological factor for recurrence is tubal disease and others are assisted conception and non-invasive management of cornual pregnancy. 29 However there has been case report of recurrence of interstitial ectopic following surgical management of cornual ectopic. Most conservative surgical and medical management techniques do not remove the interstitial portion of fallopian tubes. It is advisable to be cognisant of persistent trophoblastic tissue and recurrence in future pregnancies. 29

Managing ipsilateral tubal ectopic

Ipsilateral ectopic occurs after total salpingectomy or adnexectomy and can occur in either the isthmic part of the tube (stump ectopic) or the interstitial part of the tube. Isthmic EP is a gynaecological emergency, with mortality rates around 2.0%–2.5% in contrast to other ectopic pregnancies where mortality rates are around 0.14%. 30 Ipsilateral tubal stump ectopic pregnancies give appearances similar to cornual ectopic. Various hypotheses have been postulated for ipsilateral ectopic pregnancies. These include transperitoneal migration of spermatozoa or embryo through the patent tube to the side of the damaged tube, the oocyte from the normal ovary may be fertilised normally in the patent tube and then later implant in the stump via intrauterine migration. It is also possible that despite the surgical excision of the tube following salpingectomy, there is some degree of patency in the remaining interstitial part. 31 There have been studies that endo-loop ligation is as good as electrosurgery for haemostasis, and it prevents visceral injury related to the use of diathermy.32,33 It also enables reduced operating times and reduced postoperative pain. However, there are case-reports that endo-loop usage can lead to residual tubal stump due to technical difficulties. 33 It has also been suggested that the use of electrosurgery to excise the proximal tube, followed by endo-loop for total salpingectomy to reduce the risk of recurrence of ectopic in tubal stump. 33 The residual portion of the tube can be minimised by fulguration of the remnant stump.

Conclusion

REP has a significant impact on the reproductive health of patients. With a 10%–20% recurrence rate, once a patient has a history of EP, identifying any risk factors for future REP should be considered. This should start with the management of PE. Robust measures for identifying PID signs and prompt treatment with a test of cure and contact tracing should be the doctrine. Considering adhesiolysis, checking for tubal patency is an employable measure before planning future conception.

Ultrasound at very early gestation to locate the pregnancy is prudent. In cases of REP, medical management seems less effective. While medical management of cornual EP had a good success rate, the risk of failed treatment requiring repeat injections and increased risk of uterine rupture because of the eccentric location should be anticipated, and the patient counselled accordingly. Also, the need for repeated attendance for blood tests and patient compliance to this is a significant hurdle in the successful management of ectopic pregnancies. Gestation at which the EP has been identified has a momentous role to play as much as patient choice. All surgical management of ectopic pregnancies should justify a salpingectomy over salpingostomy unless the contralateral tube appears diseased.3,13 Nevertheless the risk of recurrence is still high. At salpingectomy, care should be taken to ensure no residual tubal stump is left to avoid an ipsilateral tubal stump ectopic.

Footnotes

Contributors: Ibrahim Bolaji, Caleb Igbenehmi, Mary Oluwakemisola Awoniyi.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethics approval: Not applicable.

Permission from patient(s) or subject(s) obtained in writing for publishing their case report: Yes.

Permission obtained in writing from patient or any person whose photo is included for publishing their photographs and images: Yes.

Confirm that you are aware that permission from a previous publisher for reproducing any previously published material will be required should your article be accepted for publication and that you will be responsible for obtaining that permission: Yes.

Guarantor: Aparna Yandra.

ORCID iD: Aparna Yandra  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2817-1947

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2817-1947

References

- 1. BJOG: Centre for maternal and child enquiries (Excecutuve summary) . London; Oxford: National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU); University of Oxford, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bolaji I, Manju S, Goodard R. Sonographic signs in ectopic pregnancy-Update. Ultrasound 2012; 20: 192–210. [Google Scholar]

- 3. NICE guidance ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage diagnosis and management: NICE clinical knowledge summary, 2023, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng126

- 4. Panelli DM, Phillips CH, Brady PC. Incidence, diagnosis and management of tubal and nontubal ectopic pregnancies: a review. Fertil Res Pract 2015; 1: 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Petrini A, Spandorfer S. Recurrent ectopic pregnancy: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health 2020; 12: 597–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ghomian N, Rastin Z. A report of three consecutive recurrent ectopic pregnancies in two patients. Hormozgan Med J 2020; 24: e95745. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fourie H, Bobdiwala S, Al-Memar M, et al. OP11.08: the management of recurrent ectopic pregnancy: a multicentre observational study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017; 50: 82–82. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hurrell A, Reeba O, Funlayo O. Recurrent ectopic pregnancy as a unique clinical sub group: a case control study. SpringerPlus 2016; 5: 265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yao M, Tulandi T. Current status of surgical and nonsurgical management of ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1997; 67: 421–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Oron G, Tulandi T. A pragmatic and evidence-based management of ectopic pregnancy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2013; 20: 446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Boer CN, van Dongen PWJ, Willemsen WNP, et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1992; 47: 164–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cantwell R, Clutton-Brock T, Cooper G, et al. Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer: 2006-2008. The Eighth Report of the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. BJOG 2011; 118: 1–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tulandi T. Reproductive performance of women after two tubal ectopic pregnancies. Fertil Steril 1988; 50: 164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Seow KM, Hwang JL, Tsai YL. Ultrasound diagnosis of a pregnancy in a Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2001; 18: 547–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ben Nagi J, Ofili-Yebovi D, Marsh M, et al. First-trimester cesarean scar pregnancy evolving into placenta previa/accreta at term. J Ultrasound Med 2005; 24: 1569–1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bouyer J, Coste J, Fernandez H, et al. Sites of ectopic pregnancy: a 10 year population-based study of 1800 cases. Hum Reprod 2002; 17: 3224–3230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Atrash HK, Friede R, Hogue CJR. Abdominal pregnancy in the United States: frequency and maternal mortality. Obstet Gynecol 1987; 69: 333–337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Prabhudev P, Sapna IS, Mudegoud SM. A rare case report of recurrent ectopic pregnancy. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2020; 9: 1753–1757. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang X, Huang L, Yu Y, et al. Risk factors and clinical characteristics of recurrent ectopic pregnancy: a case–control study. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2020; 46: 1098–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ibecheozor C, Kurup S, Lulseged E, et al. Identifying the Various Risk Factors for Recurrent Ectopic Pregnancy. J Natl Med Assoc 2020; 112: S37. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang D, Shi W, Li C, et al. Risk factors for recurrent ectopic pregnancy: a case–control study. BJOG Int J Obstet Gynaecol 2016; 123: 82–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kaplan S, Kaplan E, Türkler C, et al. Recurrent ectopic pregnancy risk factors and clinical features: a case-control study in Turkey. J Health Inequalities 2021; 7: 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ellaithy M, Asiri M, Rateb A, et al. Prediction of recurrent ectopic pregnancy: a five-year follow-up cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2018; 225: 70–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Levin G, Dior UP, Shushan A, et al. Success rate of methotrexate treatment for recurrent vs. primary ectopic pregnancy: a case-control study. J Obstet Gynaecol 2020; 40: 507–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mol F, van Mello NM, Strandell A, et al. Salpingotomy versus salpingectomy in women with tubal pregnancy (ESEP study): an open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014; 383: 1483–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dagar M, Srivastava M, Ganguli I, et al. Interstitial and cornual ectopic pregnancy: conservative surgical and medical management. J Obstet Gynaecol India 2018; 68: 471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tuncay G, Karaer A, Coskun EI, et al. Treatment of unruptured cornual pregnancies by local injections of methotrexate or potassium chloride under transvaginal ultrasonographic guidance. Pak J Med Sci 2018; 34: 1010–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tinelli R, Stomati M, Surico D, et al. Laparoscopic management of a cornual pregnancy following failed methotrexate treatment: case report and review of literature. Gynecol Endocrinol 2020; 36: 743745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sahoo S, Jose J, Shah N, et al. Recurrent cornual ectopic pregnancies. Gynaecol Surg 2009; 6: 389–391. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lakhotia S, Yussof SM, Aggarwal I. Recurrent ectopic pregnancy at the ipsilateral tubal stump following total salpingectomy case report and review of literature. Singapore: Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Takeda A, Manabe S, Mitsui T, et al. Spontaneous ectopic pregnancy occurring in the isthmic portion of the remnant tube after ipsilateral adnexectomy: report of two cases. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2006; 32: 190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Rizos A, Eyong E, Yassin A. Recurrent ectopic pregnancy at the ipsilateral fallopian tube following laparoscopic partial salpingectomy with endo-loop ligation. J Obstet Gynaecol 2003; 23: 678–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lim Y-H, Soon PN, Ng PHO, et al. Laparoscopic salpingectomy in tubal pregnancy: prospective randomized trial using endoloop versus electrocautery. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2007; 33: 855–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]