Abstract

Background

Low back pain (LBP) is the most common medical cause of disability among adults 65 or older. No previous study has characterized health care costs and treatment patterns of LBP among Medicare beneficiaries.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study quantifies health care utilization costs among Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed LBP, compares costs between patients managed operatively and nonoperatively, identifies costs associated with treatment guideline nonadherence, and characterizes opioid prescribing patterns. Patients were queried via ICD codes from a 20% random sample of Medicare claims records. Patients with concomitant or previous “red flag” diagnoses, neurological deficits, or diagnoses that could cause nondegenerative LBP were excluded. Total costs of care in the year of diagnosis were calculated and stratified by operative versus nonoperative management. To assess for guideline adherence, utilization and costs of different services were tabulated. Opioid prescription patterns were characterized by quantity, cost, duration, and medication type.

Results

About 1,269,896 patients were identified; 23,919 (1.8%) underwent surgery. These accounted for 7% of the cohort's total cost ($514 million total, $21,496 per person). Patients treated nonoperatively accounted for over $7 billion in costs ($5,880 per person; p<.001). Within the nonoperative cohort, 626,896 (50.3%) patients were nonadherent to current guidelines for conservative management of LBP. Guideline nonadherence increased total annual costs by $4,012 per person ($7,873 for nonadherent vs. $3,861 for adherent patients, p<.001). About 460,867 opioid prescriptions were filled for 303,796 unique patients (23.9%) within 30 days of LBP diagnosis. Within the nonsurgical cohort, patients nonadherent to imaging guidelines were more likely to have an opioid prescription within this window than adherent patients (26.5% vs. 21.2%; p<.001).

Conclusions

Nonoperative management of LBP is associated with significantly lower costs per patient. Early imaging and opioid prescription are significant drivers of excess cost. Adherence to proposed treatment guidelines can save over $2.8 billion in total health care costs.

Keywords: Guideline adherence, Health care utilization, Imaging, Low back pain, Medicare, Nonoperative management

Introduction

The 2017 National Population Projections of the U.S. Census Bureau predicted that by 2030, 1 in 5 adults in the United States will be 65 years or older [1]. This increase presents challenges to the United States’ health care system, especially to the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) [2]. An aging population increases the number of Medicare beneficiaries; understanding health care expenditures and utilization patterns for this population is necessary to both project future expenditures and identify opportunities for cost containment.

Among older adults, low back pain (LBP) is the most common medical cause of pain and disability [3] with studies suggesting a prevalence in musculoskeletal pain reaching up to 85% [4,5]. Musculoskeletal conditions including LBP remain one of the largest areas of national health expenditures [6]. The American College of Physicians favors conservative management of LBP [7].

A retrospective analysis of over 2 million patients enrolled in commercial health insurance plans revealed that surgical intervention and early imaging were the greatest drivers of cost among patients with newly diagnosed LBP and lower extremity pain (LEP) [8]. In this study, we build upon these methods to analyze the costs and modalities of treatment among Medicare beneficiaries of ages 65 years and older with newly diagnosed LBP. To our knowledge, this is the first study to characterize health care costs and treatment patterns of newly diagnosed LBP among Medicare beneficiaries. In addition to determining health care utilization of operative and nonoperative management of LBP in Medicare beneficiaries, we also calculate the added costs associated with guideline nonadherence in the nonoperative management of LBP. Finally, we characterize opioid prescribing patterns as recent guidelines note that providers should refrain from providing opioids unless other pain control modalities fail [[9], [10], [11], [12]].

Methods

Study design and database

This retrospective longitudinal cohort study uses de-identified data from a 20% random sample of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Medicare databases of over 18 million individuals. We executed the study by querying the MEDPAR, Outpatient, and Part D files which contain detailed cost information, medical record details, and prescription drug data described by International Classification of Diseases (ICD), Common Procedural Terminology (CPT), and National Drug Codes (NDC). These databases assign patients a unique identification number, enabling longitudinal analysis and linkage between data sets. The Stanford Institutional Review Board approved this study. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline [13].

Cohort definition

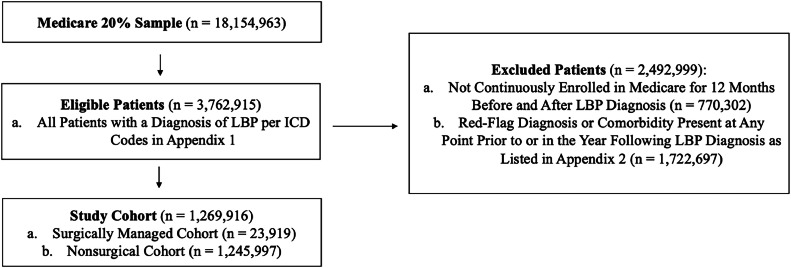

We queried the Medicare database to identify patients ages 65 and older with diagnoses of new-onset LBP using ICD codes from both the MEDPAR and Outpatient databases from 2006 to 2018 (Appendix 1). The initial visit, which served as a proxy for time of LBP onset, was defined as the first visit during which a beneficiary had a claim with an ICD-9-CM (or ICD-10-CM) code that met the criteria of LBP without previous inclusion diagnoses in the 12 months prior to this visit. A 12-month continuous enrollment window before and after the initial visit was required for inclusion. Patients were excluded if they had concomitant or previous diagnoses that could cause LBP of nonmechanical etiologies at any point before or in the year following the initial visit (Appendix 2). These “red-flag” diagnoses were identified by individual ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, with pre-existing variables in CMS’ Chronic Conditions Data Warehouse, or as one of the comorbidities required to generate the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index. Patients were excluded if any of these diagnoses were recorded at any point before or in the year following a patient's LBP diagnosis. The cohort selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Cohort construction flowchart.

Outcomes and covariates

The primary outcome measure in this study was a continuous variable denoting total health care spending in the year of a patient's LBP diagnosis. Costs were reported according to whether a patient received spinal surgery, the pattern of conservative management, and the types of health care services used. Costs were defined as the total amount paid by Medicare for all claims corresponding to a given patient in the year of their LBP diagnosis. All costs were adjusted for medical inflation to represent costs in dollars in the first quarter of 2023. Patients were classified into a “surgical” or “nonsurgical” cohort to denote whether the patient underwent spine surgery in the year of their initial LBP diagnosis. The terms “nonsurgical spending” and “surgical spending” are used to refer to aggregate costs from the nonsurgical and surgical cohorts, respectively. Using this definition, costs associated with nonsurgical interventions (e.g., imaging) for patients who eventually underwent surgery were included in surgical spending.

Next, we explored the potential economic impact of deviation from LBP management guidelines among patients who did not receive surgery. To do so, we selected the following 2 measurable examples of widely recommended LBP management guidelines: (1) imaging should not be obtained within 30 days of diagnosis and (2) imaging should not be obtained without or before a trial of physical therapy (PT). Similarly, we assessed the frequency, amount, and associated costs of opioids prescribed to patients receiving new-onset LBP diagnoses, as recently published guidelines and trials note that opioids should not be prescribed unless other pain control modalities are found ineffective, and that opioids are not superior to placebo for the management of acute LBP [[9], [10], [11], [12]]. Next, we characterized the distribution of interventions (e.g., epidural steroid injection [ESI], imaging, PT) and the associated 12-month costs in patients with LBP who underwent surgical and nonsurgical treatment. For each group of patients receiving a particular set of interventions, we calculated the aggregate value of their 12-month costs and the percentage of its dollar amount in the context of the total nonsurgical or surgical spending. We also investigated the frequency at which patients with new-onset LBP received spinal imaging with no further intervention (ESI, PT, spinal surgery) recorded at any point in their Medicare enrollment.

Patient-level covariates included age in years, sex, comorbidities (based on a validated update to the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index), types of spine imaging obtained, other procedures related to LBP or LEP diagnoses (ESI, PT), spinal surgery status (i.e., surgery or no surgery), type(s) of surgery received (if applicable), and the presence of concomitant opioid prescriptions. Spinal surgery was defined as a static, rather than time-varying, variable (e.g., if patients received surgery at 6 months after diagnosis, they were considered patients treated surgically throughout their follow-up period rather than classified as patients treated nonsurgically before surgery and recategorized as patients treated surgically afterward).

The primary outcome was total costs of care in the year of the patient's diagnosis, stratified by whether the patient underwent spinal surgery during that year. We defined spinal surgery as the occurrence of any procedure following LBP diagnosis as identified by the CPT codes listed in Appendix 3. Secondary outcomes were rates of adherence to published guidelines regarding the conservative management of LBP and subsequent costs, as well as rates and quantities of opioid prescriptions following LBP diagnosis.

Statistical analysis

Summary statistics for relevant variables in the study cohort were computed and reported via the TableOne package. We used χ2 tests to compare differences for categorical variables, while we assessed differences between continuous variables using paired t tests or Wilcoxon rank sum tests. We used standardized mean difference (SMD) as a measure of effect size. SMD reflects the magnitude of differences in characteristics between groups and the magnitude of effect is described as small, medium, or large for SMD values of 0.2, 0.5, or 0.8, respectively [14]. Adjusted costs were computed by constructing multivariable linear regression models that included age, sex, and ECI as covariates: total costs in the year following LBP diagnosis were the outcome in each model. Each model also contained a predictor of interest. These were a categorical variable indicating whether a patient underwent spinal surgery, a categorical variable indicating whether a patient was adherent to imaging guidelines, and a categorical variable indicating whether an opioid prescription was filled within thirty days of LBP diagnosis. The model coefficients for these predictors of interest were reported as adjusted costs. No additional variables were constructed or used in regression analysis. The threshold used to assess statistical significance throughout all analyses was p<.05. All tests were 2-sided. All statistical analyses were conducted in the R Environment for Statistical Computing (Vienna, Austria). No imputation of missing data (less than 1%) was performed at any point throughout this study.

Results

Cohort characteristics

A total of 1,269,896 patients met our inclusion criteria. 1,245,997 (98.2%) patients were managed nonoperatively while 23,919 (1.8%) patients underwent spinal surgery. Patients receiving spinal surgery were slightly older than their nonsurgical cohort counterparts (68.81 vs. 67.38, SMD=0.124, p<.001). Females comprised 55.7% of the patients diagnosed with new-onset LBP but made up a minority (49.8%) of the cohort receiving surgical intervention (SMD=0.118, p<.001). Expenditures attributable to patients treated nonoperatively, the majority (98.2%) of our study population, accounted for 93.4% of the total 12-month spending ($9.95 billion). The remaining 6.6% of the total 12-month cost ($698 million) was spent among the 1.8% patients who underwent surgery. After adjusting for age, sex, and comorbidity, the per-patient 12-month cost was significantly higher for the surgical cohort compared with the nonsurgical cohort (Estimate: $22,017.66, 95% Confidence Interval: $21,763–22,272) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparing surgical patients to nonsurgical patients.

| Nonsurgical | Surgical | Standardized mean difference (SMD) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size (% of full cohort) | 12,45,997 (98.1) | 23,919 (1.9) | ||

| Age (mean (SD)) | 67.38 (13.35) | 68.81 (9.61) | 0.124 | <.001 |

| Female (%) | 693,397 (55.7) | 11,902 (49.8) | 0.118 | <.001 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities (median (IQR)) | 2.00 [1.00, 4.00] | 2.00 [1.00, 4.00] | 0.128 | <.001 |

| ESI (%) | 40,099 (3.2) | 2,866 (12.0) | 0.335 | <.001 |

| Physical therapy (%) | 304,948 (24.5) | 9,699 (40.5) | 0.348 | <.001 |

| Any imaging (%) | 673,129 (54.0) | 23,919 (100.0) | 1.305 | <.001 |

| XR (%) | 497,429 (39.9) | 20,999 (87.8) | 1.149 | <.001 |

| CT (%) | 169,029 (13.6) | 11,374 (47.6) | 0.794 | <.001 |

| MRI (%) | 226,913 (18.2) | 18,278 (76.4) | 1.435 | <.001 |

| Decompression (%) | 7,699 (32.2) | |||

| Fusion (%) | 16,220 (67.8) | |||

| Receiving opioid prescription within 30 days of diagnosis (%) | 296,925 (23.8) | 6,871 (28.7) | 0.111 | <.001 |

| Total annual cost following LBP diagnosis (mean [SD]) | 7,985.65 (20561.03) | 29,192.02 (37230.51) | 0.705 | <.001 |

Cost breakdown of the surgical and nonsurgical cohorts

Among patients treated nonsurgically, 33.7% did not receive PT, imaging, or ESI. They accounted for 17.7% ($1.76 billion) of the nonsurgical 12-month health care expenditures ($9.95 billion). Patients who received imaging only (39.7%) accounted for 49.2% of the 12-month total costs in the nonsurgical cohort ($4.89 billion). Patients managed with PT alone or PT with imaging made up 11.3% and 12.1% of the nonsurgical cohort and made up 7.0% ($699 million) and 22.1% ($2.20 billion) of total nonsurgical cohort costs (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Number of patients and percentage of total 12-month costs based on different management patterns for patients in the nonsurgical cohort.

Within the nonsurgical cohort, 356,344 patients (28.6% of the nonsurgical cohort) underwent imaging but did not receive any further interventions (PT, ESI, spine surgery) during the period of follow-up. 89,285 patients received a CT scan, 105,342 underwent MRI, and 265,159 had radiographs taken. The cost of these scans that did not result in additional management (PT, ESI, or surgery) totaled $44,162,552 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Assessing rates and cost losses of in patients receiving imaging followed by no other interventions (sample size nonsurgical cohort: 1245997).

| Any imaging with no additional interventions | CT with no additional interventions | MRI with no additional interventions | Radiograph with no additional interventions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (% of nonsurgical cohort) | 356,344 (28.6) | 89,285 (7.2) | 105,342 (8.5) | 265,159 (21.3) |

| Estimated additional costs to healthcare system | $44,162,522.02 | $12,102,581.75 | $21,275,923.74 | $10,784,016.53 |

Additional interventions include PT, ESI, or spinal surgery at any time point in the patient's Medicare enrollment.

Cost estimates were derived by multiplying number of patients receiving intervention multiplied the 2023 fee listed in Medicare's physician schedule for the service. The CPT codes employed were: 72131 (CT Lumbar Spine without Contrast; Cost: $135.55), 72148 (MRI Lumbar Spine without Contrast; Cost: $201.97), and 72100 (X-Ray Lumbar Spine 2-3 Views; Cost: $40.67).

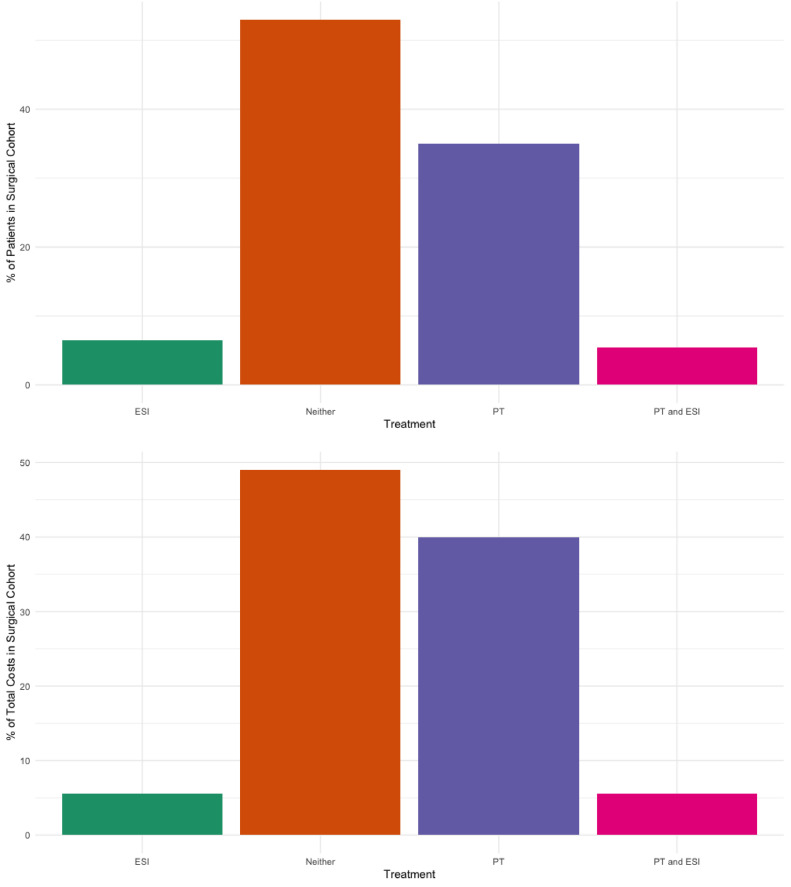

Among the surgical cohort, 53.0% did not receive either PT or ESI. These patients had health care expenditures of $342 million as a group (mean per patient, $26,991) during the first 12 months after diagnosis. Aggregate 12-month costs from patients who underwent surgery and received PT only (35.0%) amounted to $278 million, with per-patient costs of $33,284. Patients who underwent surgery and received ESI without PT (6.5%) collectively had a total 12-month cost of $38 million (mean per patient, $25,006) and those who had both PT and ESI (5.5%) also cost $38 million as a group (mean per patient, $29,261) during the first 12-month period (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Number of patients and sum of total 12-month costs based on different management patterns for patients in the surgical cohort.

Guideline nonadherence in the nonsurgical cohort

Within the nonsurgical cohort, 626,896 (50.3% of nonsurgical cohort) patients appeared to be nonadherent to current imaging guidelines for conservative management of LBP. Patients that were nonadherent to imaging guidelines were older (68.04 years vs. 66.70 years, SMD=0.1, p<.001) and had a slightly greater Elixhauser comorbidity burden (median comorbidities nonadherent group: 2.0, interquartile range 1.0–5.0 vs. adherent group: 2.0, interquartile range 1.0–4.0, SMD = 0.148). 460,099 patients in the nonsurgical cohort (30.9% of nonsurgical cohort) underwent imaging within 30 days of diagnosis, while 619,473 patients (49.7% of nonsurgical cohort) received imaging before a trial of physical therapy (Table 3). Guideline adherent patients mean annual costs were $5,225 per person, while nonadherent patients cost $10,711 per person on average (SMD=0.27, p<.001). When adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities, guideline nonadherence was associated with a $4,538 increase in per person annual costs (Table 4). Guideline adherence could have potentially saved over $2.84 billion in total health care costs over the study period.

Table 3.

Comparing Imaging guideline adherent patients to nonadherent patients in the nonsurgical cohort (sample size of the nonsurgical cohort: 1245997).

| Nonadherent | Adherent | SMD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size (% of full cohort) | 626,896 (50.3) | 619,101 (49.7) | ||

| Age (mean [SD]) | 68.04 (13.25) | 66.70 (13.42) | 0.1 | <.001 |

| Female (%) | 1.56 (0.50) | 1.56 (0.50) | 0.006 | .001 |

| Elixhauser comorbidities (median [IQR]) | 2.00 [1.00, 5.00] | 2.00 [1.00, 4.00] | 0.148 | <.001 |

| ESI (%) | 24,631 (3.9) | 15,388 (2.5) | 0.083 | <.001 |

| Physical therapy (%) | 114,510 (18.3) | 190,438 (30.8) | 0.294 | <.001 |

| Any imaging (%) | 626,896 (100.0) | 46,233 (7.5) | 4.978 | <.001 |

| XR (%) | 467,716 (74.6) | 29,713 (4.8) | 2.036 | <.001 |

| CT (%) | 153,380 (24.5) | 15,649 (2.5) | 0.678 | <.001 |

| MRI (%) | 212,252 (33.9) | 14,661 (2.4) | 0.896 | <.001 |

| Early imaging (%) | 460,099 (73.4) | |||

| Imaging before PT (%) | 619,473 (98.8) | |||

| Receiving opioid prescription within 30 days of diagnosis (%) | 165,905 (26.5) | 131,020 (21.2) | 0.125 | <.001 |

| Total annual cost following LBP diagnosis (mean [SD]) | 10,711.28 (25274.36) | 5,225.70 (13742.61) | 0.27 | <.001 |

Table 4.

Assessing rates of imaging guideline nonadherence and associated costs in the nonsurgical cohort (nonsurgical cohort: 1245997).

| Number of nonadherent patients | Number of adherent⁎ patients | Total annual cost following LBP diagnosis for nonadherent group | Total annual cost following LBP diagnosis for adherent group | SMD | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Imaging (%) | 460,099 (36.9) | 785,898 (63.1) | 8,551.04 (21737.95) | 7,019.90 (18336.98) | 0.076 | <.001 |

| Imaging Before/Without PT (%) | 619,473 (49.7) | 626,524 (50.3) | 10,704.09 (25308.64) | 5,297.80 (13889.03) | 0.265 | <.001 |

| Early Imaging or Imaging Before/Without PT (%) | 626,896 (50.3) | 619,101 (49.7) | 10,711.28 (25274.36) | 5,225.70 (13742.61) | 0.27 | <.001 |

Adherent means that a patient did not receive imagining within 30 days of LBP diagnosis or imaging before PT.

Opioid prescription patterns

Within the entire study cohort (surgical and nonsurgical), 460,867 prescriptions for opioids were filled for 303,796 unique patients (23.9%) within thirty days of their initial LBP diagnosis. Patients in the nonsurgical cohort that were not adherent to imaging guidelines were more likely to have an opioid prescription within this window (26.5% of nonadherent patients vs. 21.2% of adherent patients, SMD=0.125, p<.001). The mean length of opioid prescriptions was 14.04 days (SD: 11.91), and each prescription cost Medicare a mean of $24.39 per prescription, amounting to over $11 million in direct drug costs (Table 5). Moreover, when adjusted for age, sex, and comorbidities, being prescribed any opioid medication within 30 days of LBP diagnosis was associated with a $1,019 increase in annual costs per patient, which corresponds to over $309 million in total costs associated with the prescription of opioids for LBP throughout the study. Hydrocodone (53.3%), oxycodone (23.9%), and tramadol (18.5%) were the most prescribed medications.

Table 5.

Opioid prescribing patterns in the study cohort.

| Number of opioid prescriptions filled within 30 days of LBP diagnosis | 460,867 |

|---|---|

| Mean length of prescription in days (SD) | 14.04 (11.91) |

| Mean cost of prescription to medicare (SD) | $24.39 (95.64) |

| Types of opioids prescribed (% of all prescriptions) | |

| Hydrocodone | 245,534 (53.3) |

| Hydromorphone | 7,011 (1.5) |

| Morphine | 12,227 (2.7) |

| Oxycodone | 110,037 (23.9) |

| Oxymorphone | 863 (0.2) |

| Tramadol | 85,195 (18.5) |

Discussion

This analysis of more than 1.25 million Medicare patients shows that surgical intervention, guideline nonadherent imaging, and early opioid utilization are the main drivers of cost in Medicare beneficiaries with newly diagnosed LBP. Our findings reveal that a change in management of nonoperative patients could significantly reduce costs of care. These findings illustrate the value of guideline adherent medical management of older adults with LBP.

A previous study explored health care utilization among commercially insured patients with low back and low extremity pain [8]. This earlier study had similar cohort characteristics to our study population with the key difference being that the previous cohort of patients were commercially insured, and our patients are Medicare beneficiaries. Median age of LBP diagnosis of the earlier cohort was 47 years old and is 67 years old in the present study.

The distribution of surgical vs nonsurgical patients across both studies was similar with a surgical cohort comprising 1.2% of the patients in the previous study and the present surgical cohort corresponding to 1.8% of our study population. There were significant high rates of guideline nonadherence among our nonsurgical cohort. In Kim and colleagues’ 2019 study, 32.3% of patients received imaging within 30 days of diagnosis. In our cohort, 30.9% of nonsurgical patients also underwent early imaging, reinforcing that guideline nonadherence remains a significant driver of health care costs across different insurance types.

Kim and colleagues found surgical intervention and early imaging to be among the greatest drivers of cost among their patient population. In the present cohort of Medicare beneficiaries this remains true: Within our nonsurgical cohort, nearly 30% of patients underwent imaging but did not receive further intervention. Imaging of patients who did receive further intervention contributed to over $44 million dollars in costs.

In the present cohort, patients who underwent surgery within the year or their LBP diagnosis were more likely to fill opioid prescriptions following diagnosis. Within our nonsurgical cohort, those whose care was nonadherent to imaging guidelines were also more likely to have opioid prescriptions. Being prescribed opioid medications within 30 days of LBP diagnosis was associated with an excess of $309 million in total health care costs throughout the study.

A reason for guideline nonadherence in LBP treatment may be physicians lacking knowledge about current guidelines. Many primary care physicians may be the first to encounter patients with LBP. A previous study by Schectman and colleagues explored how to increase primary care physician awareness of acute LBP treatment guidelines to reduce health care costs [15]. Their randomized controlled trial measured the effect of a physician education on resource utilization of radiologic and specialty services for LBP pain management. Physicians in the study were randomized to receive (1) guideline education and feedback, (2) materials for patient education, (3) both, or (4) neither. Guideline adherence and resource utilization were measured over a 12-month period before and after their intervention. The researchers found that physician education and feedback led to a 5.4% increase in guideline adherence. Patient education did not significantly change guideline adherence, but patient characteristics including prior LBP history and duration of pain were predictors of guideline adherence and resource utilization.

Another reason for guideline nonadherence may be physicians’ desires to satisfy patient requests for further diagnostic work up or treatment. A qualitative study in the Netherlands explored which factors lead to nonadherence through physician and patient interviews [16]. Surprisingly, the researchers found that most physicians were well-informed and agreed with treatment guidelines even when deviating from them. When interviewed, physicians stated that they did not adhere to guidelines because they felt the need to comply with patient demands. This included requests for further imaging, a significant driver of cost in our study.

Our study has found that guideline nonadherence is a major driver of Medicare costs in our LBP population. Medicare beneficiaries have more than doubled in the last 15 years, and Medicare is projected to cover 60% of the eligible population by 2030 [17]. Our study is the first to characterize health care costs and treatment patterns of newly diagnosed LBP among Medicare beneficiaries. Because of this growing number of Medicare beneficiaries, it is crucial to identify which barriers remain to improve guideline adherence and lower associated health care costs. Our study highlights the need for interventions that promote guideline adherence in LBP management among Medicare beneficiaries.

Limitations

This study is a retrospective review of a large database, which have multiple well-documented limitations [18]. One key limitation specific to our study is that CMS data does not enable us to determine if patients had a LBP diagnosis prior to entering Medicare. We have tried to address this by only including patients diagnosed with LBP after a 12-month continuous enrollment window, which would allow time for those previously diagnosed with LBP and commercially insured to transition their care to Medicare without being included in our cohort. The validity of these results relies on proper documentation of ICD and CPT codes, which is a limitation present in all retrospective claims database studies. Another limitation of this study is the inability to assess regional variations in practice patterns due to the lack of geographic identifiers in our dataset. Prior research has demonstrated significant regional differences in surgical rates and healthcare utilization, which may have influenced our findings but could not be analyzed in this study. Additionally, our data lacks granularity to assess whether MRIs or other imaging was ordered and performed within the same practice, limiting our ability to investigate potential conflicts of interest or utilization patterns in this regard. Finally, due to constraints in our dataset, our analysis treated spinal surgery as a static variable, meaning patients who eventually underwent surgery were classified as having received surgical treatment for the entire follow-up period, even if they initially received nonsurgical care. This does not reflect the time-varying nature of treatment decisions and progression, which may have implications for interpreting the outcomes we reported.

Conclusions

In a 20% sample of CMS patients, nonoperative management of LBP was associated with significantly lower per patient expenditures. Potentially unnecessary imaging and opioid prescription are significant drivers of excess cost. Adherence to proposed treatment guidelines may save billions of dollars in public expenditure.

Funding

This project was supported by a grant from the Vin Gupta Family Foundation. Data for this project were accessed using the Stanford Center for Population Health Sciences Data Core. The Population Health Sciences Data Core is supported by a National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Science Clinical and Translational Science Award (grant UL1 TR001085) and from internal Stanford funding.

Declarations of competing interests

One or more of the authors declare financial or professional relationships on ICMJE-NASSJ disclosure forms.

Footnotes

FDA device/drug status: Not applicable.

Author disclosures: MIBG: Nothing to disclose. TJ: Nothing to disclose. GDRC: Nothing to disclose. YW: Nothing to disclose. EAN: Nothing to disclose. JKR: Consulting: Stryker Spine (C), Alphatec (C), Mirus Spine (C).

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.xnsj.2024.100565.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Vespa J, Medina L, Armstrong D. U.S. Census Bureau; Washington, DC: 2020. Demographic turning points for the united states: population projections for 2020 to 2060 population estimates and projections current population reports.https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.pdf Accessed March 15, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Get started with Medicare | Medicare. www.medicare.gov. https://www.medicare.gov/basics/get-started-with-medicare#:∼:text=Medicare%20is%20health%20insurance%20for Accessed March 15, 2024.

- 3.Wong AYL, Karppinen J, Samartzis D. Low back pain in older adults: risk factors, management options and future directions. Scoliosis Spinal Disord. 2017;12:14. doi: 10.1186/s13013-017-0121-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bressler HB, Keyes WJ, Rochon PA, Badley E. The prevalence of low back pain in the elderly. A systematic review of the literature. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1999;24(17):1813–1819. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199909010-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Podichetty VK, Mazanec DJ, Biscup RS. Chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain in older adults: clinical issues and opioid intervention. Postgrad Med J. 2003;79(937):627–633. doi: 10.1136/pmj.79.937.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dieleman JL, Baral R, Birger M, et al. US spending on personal health care and public health, 1996-2013. JAMA. 2016;316(24):2627–2646. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–530. doi: 10.7326/M16-2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim LH, Vail D, Azad TD, et al. Expenditures and health care utilization among adults with newly diagnosed low back and lower extremity pain. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones CMP, Day RO, Koes BW, et al. Opioid analgesia for acute low back pain and neck pain (the OPAL trial): a randomised placebo-controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. Lancet. 2023;402(10398):304–312. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00404-X. 2023 Aug 19;402(10402):612] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dowell D, Ragan KR, Jones CM, Baldwin GT, Chou R. CDC clinical practice guideline for prescribing opioids for pain - United States, 2022. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2022;71(3):1–95. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7103a1. Published 2022 Nov 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiarotto A, Koes BW. Nonspecific low back pain. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(18):1732–1740. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp2032396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Humphreys K, Shover CL, Andrews CM, et al. Responding to the opioid crisis in North America and beyond: recommendations of the Stanford-Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2022;399(10324):555–604. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02252-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):806–808. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39335.541782.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen J. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schectman JM, Schroth WS, Verme D, Voss JD. Randomized controlled trial of education and feedback for implementation of guidelines for acute low back pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):773–780. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.10205.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schers H, Wensing M, Huijsmans Z, van Tulder M, Grol R. Implementation barriers for general practice guidelines on low back pain a qualitative study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26(15):E348–E353. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200108010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochieng N, Damico A. Medicare advantage in 2023: enrollment update and key trends. KFF. 2023 https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/medicare-advantage-in-2023-enrollment-update-and-key-trends/ Published August 9, 2023. Accessed March 10, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haut ER, Pronovost PJ, Schneider EB. Limitations of administrative databases. JAMA. 2012;307(24):2589–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.6626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.