Abstract

The ability of human immunodeficiency virus strain MN (HIVMN), a T-cell line-adapted strain of HIV, and X4 and R5 primary isolates to bind to various cell types was investigated. In general, HIVMN bound to cells at higher levels than did the primary isolates. Virus bound to both CD4-positive (CD4+) and CD4-negative (CD4−) cells, including neutrophils, Raji cells, tonsil mononuclear cells, erythrocytes, platelets, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), although virus bound at significantly higher levels to PBMC. However, there was no difference in the amount of HIV that bound to CD4-enriched or CD4-depleted PBMC. Virus bound to CD4− cells was up to 17 times more infectious for T cells in cocultures than was the same amount of cell-free virus. Virus bound to nucleated cells was significantly more infectious than virus bound to erythrocytes or platelets. The enhanced infection of T cells by virus bound to CD4− cells was not due to stimulatory signals provided by CD4− cells or infection of CD4− cells. However, anti-CD18 antibody substantially reduced the enhanced virus replication in T cells, suggesting that virus that bound to the surface of CD4− cells is efficiently passed to CD4+ T cells during cell-cell adhesion. These studies show that HIV binds at relatively high levels to CD4− cells and, once bound, is highly infectious for T cells. This suggests that virus binding to the surface of CD4− cells is an important route for infection of T cells in vivo.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) is known to infect T cells by a sequence of events including binding of gp120 to CD4 and chemokine receptors, membrane fusion, reverse transcription, and integration. Four forms of infectious virus particles have been shown to be present in vivo, and all could be important for infection of CD4+ target cells. These forms include cell-associated virus, cell-free virus, immune-complexed virus, and cell-bound virus. During HIV replication, progeny virions assemble and bud from the surface of infected cells. The assembling and budding virus on the surface of infected cells is generally referred to as cell-associated virus and has been shown to be highly infectious to neighboring target cells (2, 33). Transmission of cell-associated virus to target cells can be >100 times more efficient than that of cell-free virus (2, 4). Virus released from infected cells is considered cell free and can reach high levels (>106 RNA copies/ml) in blood (6). The cell-free virus half-life in plasma is less than 110 min, but the exact turnover mechanism(s) remains poorly understood (31). Several studies have shown that a portion of the cell-free virus exists as immune complexes (HIV IC) resulting from binding of specific antibody and/or complement deposition on the virion surface (7, 22, 24, 36, 37).

HIV may also bind to CD4-negative (CD4−) cells in vivo, which we refer to as cell-bound virus. While binding of HIV to CD4− cells has been studied less than virus binding to CD4-positive (CD4+) cells, several CD4− cell lines and primary cell types have been shown to bind HIV even though they do not become infected. Mondor et al. demonstrated that the amount of HIV binding to CD4− HeLa cells was equivalent to that of virus binding to HeLa cells that express high levels of CD4 (23). Fujiwara et al. demonstrated that isolated follicular dendritic cells (FDC) capture HIV that is not in immune complexes but do not become infected (11). Erythrocytes from some individuals are reported to bind HIV through the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (19). Binding of HIV to CD4− cells could have functional consequences such as induction of signals in cells or induction of apoptosis. Also, since most CD4− cells do not support virus replication, some have speculated that HIV binding to uninfectable cells could provide a mechanism for clearance of virus from circulation (23). Alternatively, several studies have demonstrated that virus bound to the surface of cells remains infectious for T cells. Thus, HIV IC bound to FDC can infect T cells (11) even in the presence of neutralizing antibody (13). A non-syncytium-inducing strain of HIV bound to erythrocytes through the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines was shown to infect peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) (19). Infection of T cells with HIV IC bound to B cells was 10- to 100-fold more efficient than cell-free virus infection of T cells (15, 16). The mechanism of infection of T cells by virus bound to CD4− cells may vary depending on the cell type but could represent an important pathway of HIV infection in vivo.

The goal of the current study was to determine if HIV binds to CD4− primary cells and cell lines. Furthermore, we determined if virus bound to CD4− cells can infect CD4+ T lymphocytes and investigated the mechanism of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and isolation of primary cells.

The T-lymphocytic H9 (HTB-176) and B-lymphocytic Raji (CCL-86) cell lines used were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, Va.). Cells were grown in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Whittaker M. A. Bioproducts, Walkersville, Md.) and gentamicin (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) at 50 μg/ml. Antibodies to leukocyte function-associated antigen type 1β (LFA-1β; CD18) and CD14 were obtained from the TS1/18.1.2.11 hybridoma (HB-203; ATCC) and the 261C hybridoma (HB-246; ATCC), respectively. Each antibody was purified using an Affinity Pak Immobilized Protein A column (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

PBMC obtained from healthy donors were isolated by Ficoll-Hypaque gradient centrifugation (Whittaker M. A. Bioproducts). Stimulated PBMC were produced by culture in medium containing phytohemagglutinin (PHA; 3.0 μg/ml) for 2 days, followed by culture in medium containing interleukin-2 at 20 U/ml. Human recombinant interleukin-2 was obtained through the AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, from Maurice Gately, Hoffman-La Roche, Inc. (20). Erythrocytes were collected from the bottom layer of the density gradients and washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline.

Neutrophils were isolated from healthy donors by Ficoll-Hypaque centrifugation. The bottom layer was collected, and erythrocytes were lysed by three treatments with ice-cold deionized water, followed by treatment with 2× Hanks balanced salt solution containing 5 mM HEPES buffer (Gibco BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.). To isolate platelets, blood was drawn in acid-citrate-phosphate-dextrose anticoagulant (Biowhittaker) and centrifuged at 400 × g. The plasma fraction containing platelets was centrifuged (800 × g), washed twice with acid-citrate-phosphate-dextrose in 0.85% NaCl solution (1:6, vol/vol), and resuspended in 0.85% NaCl until use, when the platelets were resuspended in complete medium.

Fresh tonsil tissues were obtained from the Pathology Department of Rush Medical Center. Tonsil mononuclear cells were isolated by teasing the tissues. Cells were washed and passed through a 70-μm nylon Spectra/Mesh filter (Spectrum Medical Industry, Inc., Houston, Tex.) to remove aggregated cells.

CD4+ T cells were positively isolated from fresh PBMC using anti-CD4 antibody-conjugated Dynabeads M-450 and CD4/CD8 DETACHaBEAD (Dynal, Oslo, Norway) in accordance with the manufacturer's protocols. After an additional positive selection of CD4+ T cells, the remaining cells were used as CD4− PBMC. The composition of the CD4+ and CD4− cell population as measured by flow cytometry, was >99% CD4+ and <1% CD4+ (data not shown).

Virus stocks.

T-cell line-adapted (TCLA) HIV-1 strain MN (HIV-1MN; AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program [no. 317], contributed by Robert Gallo) was grown in H9 cells. The 8E5/LAV cell line (AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program [no. 95], contributed by Thomas Folks) was used to derive reverse transcriptase-defective virus and DNA for PCR standards (8). The primary isolates of HIV (HIVGP [X4] and HIVTH [R5]) were produced in PHA-stimulated PBMC as previously described (38).

Binding of HIV to cells.

To measure binding of HIV to cells, a pellet of 5 × 106 erythrocytes or platelets or 1 × 106 Raji cells, neutrophils, total PBMC, CD4-depleted PBMC, purified CD4+ T cells, or tonsil mononuclear cells was incubated with 50 μl of virus containing approximately 1,000 pg of p24 for 2 h on ice. Cells were washed to remove unbound virus and transferred to fresh tubes since some virus binding to tubes occurred during incubation. Pelleted cells were treated with 0.5% Triton X-100, and the amount of virus bound to cells was detected by p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; National Institutes of Health AIDS Vaccine Program, Frederick, Md.). To protect neutrophil-bound HIV-1 p24 from proteolytic degradation, the protease inhibitors leupeptin (2 μg/ml), aprotinin (10 μg/ml), and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (2 mM; Sigma) were added to the Triton X-100 solution. Tonsil-derived cells and PBMC were gamma irradiated with 5,000 rads before being used in HIV binding and replication experiments.

For some virus binding experiments, pelleted Raji cells were first fixed in a 0.5% formaldehyde solution for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were washed four times with serum-free medium, resuspended in complete medium, and then incubated with virus.

Infection of T cells by cell-bound and cell-free HIV.

Washed cells with bound virus (see above) or dilutions of cell-free virus were added to cultures of 2.5 × 105 H9 cells or PHA-stimulated PBMC in round-bottom polypropylene tubes (12 by 75 mm; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.). After 12 h, the cells were washed and cultured in 48-well cell culture plates (Corning Inc., Corning, N.Y.) for an additional 6 days and collected on day 7. The total volume for all experiments was 500 μl. HIV-1 replication was assessed by measuring the p24 antigen in culture supernatants. In some experiments, to assess the effects of adhesion molecules on HIV replication, anti-LFA-1β or anti-CD14 antibody was added at 1 μg/ml to H9 cells or PHA-stimulated PBMC 20 min prior to coculture with cell-bound virus. Antibody was maintained at 1 μg/ml throughout the coculture.

PCR amplification of HIV-1 DNA.

Cells in cultures containing Raji cells with bound virus, H9 cells infected with cell-free virus, or H9 cells infected with Raji-bound virus were pelleted and washed. Genomic DNA was isolated using DNAzol (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio). DNA from approximately 40,000 cells (10 μl) was amplified by PCR using primers SK38 (forward, 5′-ATA ATC CAC CTA TCC CAG TAG GAG AAA T-3′) and SK39 (reverse, 5′-TTT GGT CCT TGT CTT ATG TCC AGA ATG C-3′) (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, Iowa), which amplify a 115-bp region of HIV-1 gag DNA (18, 27). DNA dilutions from 8E5/LAV cells were used as standards. The PCRs were performed in a Perkin-Elmer (Norwalk, Conn.) 2400 automated thermocycler. The total reaction volume was 100 μl and consisted of 1× PCR buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl, 500 mM KCl, pH 9.3) containing final concentrations of 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 0.5 μM each primer, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Gibco BRL Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.). The thermocycle profile consisted of 30 cycles of denaturation at 95°C, annealing at 55°C, and extension at 72°C (30 s each). In addition, a 5-min hold denaturing step was added to the beginning and a 5-min hold extension step was added to the end. Amplified products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel (Ultrapure; Gibco BRL Life Technologies). After ethidium bromide staining, amplified DNA was visualized by UV fluorescence.

RESULTS

CD4− cells bind HIV-1.

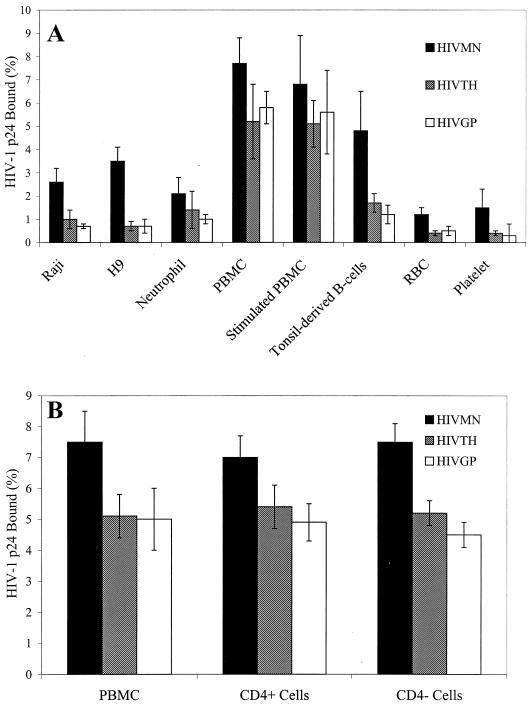

Studies were performed to determine if TCLA HIVMN or primary isolates of HIV could bind to CD4− and CD4+ cell lines. The amount of HIVMN binding to CD4− Raji cells (2.6% of input, Fig. 1A) was slightly lower but not significantly different from the amount binding to CD4+ H9 T cells (3.5%; P = 0.32, t test). Primary isolates of HIV also bound to both Raji and H9 cells (Fig. 1A). The levels of X4 HIVGP and R5 HIVTH binding to Raji and H9 cells were similar (P = 0.18 for binding to Raji cells and P = 0.5 for binding to H9 cells, t test), although the overall binding of primary isolates to these cells was lower than that of TCLA HIVMN (P = 0.003, t test). Therefore, TCLA HIVMN and primary isolates of HIV bound to both CD4− Raji B cells and CD4+ H9 T cells.

FIG. 1.

Binding of HIV to cell lines and primary blood cells. HIVMN or primary isolates of HIV (R5 HIVTH and X4 HIVGP) were incubated with Raji cells, H9 cells, neutrophils, freshly isolated or PHA-stimulated PBMC, tonsil mononuclear cells, erythrocytes (RBC), or platelets (A) or with freshly isolated PBMC or CD4-enriched or -depleted PBMC (B) for 2 h on ice. Cells were washed to remove unbound virus and transferred to fresh tubes. Cells were lysed with Triton X-100, and bound virus was measured by p24 ELISA. The percentage of virus bound to cells was calculated by dividing the total amount of virus added into the amount of virus bound. The values shown indicate the amount of virus bound to 106 cells. The results shown are the mean ± the standard deviation of at least three experiments for each cell type.

Binding of HIV to primary cells isolated from peripheral blood and tonsil tissue was also analyzed. Interestingly, CD4− neutrophils, erythrocytes, and platelets all bound significant levels of both TCLA and primary isolates of HIV (Fig. 1A). Tonsil mononuclear cells consisting of approximately 60% B lymphocytes and 40% T lymphocytes also bound both TCLA and primary isolates of HIV. The amount of virus binding to PBMC was greater than that binding to the other primary cell types tested (P < 0.001 for both HIVTH and HIVGP, t test). The percentages of HIVMN, HIVTH, and HIVGP binding to PBMC were 7.7, 5.2, and 5.8%, respectively. Stimulation of PBMC with PHA for 2 days did not significantly change virus binding. The binding of HIVMN was consistently higher than binding of primary isolates for all of the cells tested (P < 0.001, t test). Although primary isolate binding varied depending on the cell type, there was no significant difference between HIVGP and HIVTH in binding to cells (P = 0.06, paired t test).

Since HIV bound at higher levels to PBMC, we determined whether the CD4-depleted fraction of PBMC could also bind HIV. PBMC depleted of CD4 cells by magnetic bead separation (99% CD4−) had levels of virus binding essentially equivalent to those of purified CD4 cells (99% CD4+) or unseparated PBMC (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that both TCLA and primary isolates of HIV could bind to cells independently of CD4 expression.

Cell-bound HIV efficiently infects T cells during coculture.

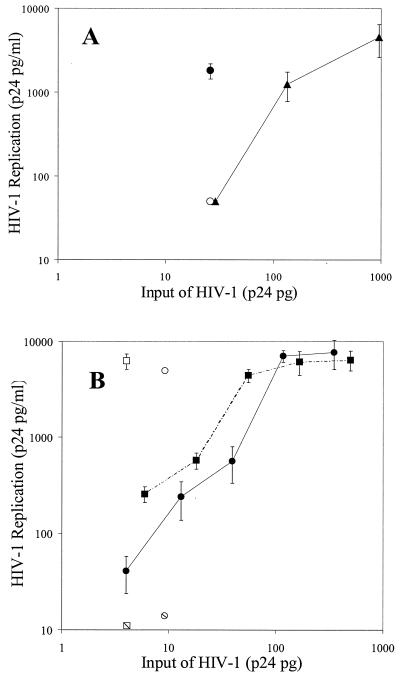

Since HIV bound to CD4− cells, we investigated the possibility that the cell-bound virus could infect CD4+ T cells. Cell-bound virus was cultured with T cells for 7 days, and levels of replication were assessed. For comparison, T cells were infected with several dilutions of cell-free HIV. To determine if CD4− cells were infected, the cells with bound virus were also cultured alone. When Raji cells, with 26 pg of p24 of bound virus, were cocultured with H9 cells, there was marked virus replication, resulting in 1,808 pg of p24/ml (Fig. 2A; Table 1). No virus replication was detected in cultures containing only Raji cells with bound HIVMN. In contrast, infection of H9 cells with the same concentration of cell-free virus (estimated from the curve generated by dilutions of cell-free virus) resulted in low HIV replication (<30 pg/ml). In six experiments, an average of 17-fold more virus replication was observed in H9 cells cultured with Raji cell-bound virus than in cultures with the same amount of cell-free virus (Table 1). We also estimated that 10-fold more cell-free virus was required to produce virus replication in H9 cells similar to that observed with Raji-bound virus infection of H9 cells. These results indicated that virus bound to Raji cells is highly infectious for H9 T cells.

FIG. 2.

Infection of T cells by cell-bound and cell-free HIV. (A) HIVMN was incubated with Raji cells. Cells were washed and then cultured alone (open circle) or with H9 T cells (filled circle) for 7 days. H9 cells were also cultured with several dilutions of cell-free virus (filled triangles). (B) HIVGP (circles) and HIVTH (squares) primary isolates were incubated with neutrophils. Cells were washed and then cultured alone (hatched symbols) or with autologous PHA-stimulated PBMC (open symbols). Stimulated PBMC were also cultured with dilutions of cell-free viruses (closed symbols). For both panels A and B, virus replication was assessed by measuring p24 levels in culture supernatants. The values shown are the mean ± the standard deviation of three determinates in one representative experiment. At least three experiments were performed.

TABLE 1.

Infection of T cells by cell-bound virusa

| Virus | Amt (pg) of p24/ml

|

Infectivity ratiod | |

|---|---|---|---|

| T-cell cocultureb | No T cellsc | ||

| Raji cell-bound HIVMN | 3,365 | 21 | 17 ± 1 |

| Neutrophil bound | |||

| HIVTH | 7,067 | 21 | 9 ± 1.4 |

| HIVGP | 8,256 | 19 | 6 ± 0.5 |

| Unstimulated PBMC bound | |||

| HIVTH | 7,400 | 56 | 10 ± 1.5 |

| HIVGP | 7,300 | 57 | 8 ± 1.5 |

| Stimulated PBMC bound | |||

| HIVTH | 7,350 | 728 | 9 ± 1.3 |

| HIVGP | 8,233 | 1,202 | 7 ± 2 |

| Tonsil mononuclear cell bound | |||

| HIVTH | 5,821 | 23 | 9 ± 1.8 |

| HIVGP | 6,039 | 23 | 12 ± 1.3 |

| Erythrocyte bound | |||

| HIVTH | 1,073 | 15 | 2 ± 0.6 |

| HIVGP | 2,520 | 31 | 2 ± 0.6 |

| Platelet bound | |||

| HIVTH | 1,830 | 30 | 3 ± 1.0 |

| HIVGP | 2,898 | 36 | 2 ± 0.6 |

Cells with bound virus were cultured with or without T cells. The virus replication levels were compared to cell-free infection of T cells for 7 days. In each experiment, at least three dilutions of cell-free virus were used to infect cells.

The T cells used for cocultures or cell-free virus infection were H9 cells in the Raji cell experiments and PHA-stimulated autologous PBMC for all other cell types. For tonsil cells, the PHA-stimulated PBMC were not autologous.

Cells with bound virus were cultured alone to determine if infection occurred.

The infectivity ratio was calculated by dividing the number of picograms of p24 per milliliter obtained after 7 days of T-cell coculture with cell-bound virus by the number of picograms of p24 per milliliter obtained when T cells were cultured with the same amount of cell-free virus. The amount of cell-free virus infection was estimated using polynomial regression analysis of p24 production levels of three to five dilutions of cell-free virus. The results shown are the mean ± the standard error of three to six experiments.

The ability of neutrophil-bound HIV primary isolates to infect PHA-stimulated T cells was also tested. Coculture of neutrophil cell-bound virus (9 pg of HIVTH or 7 pg of HIVGP) with autologous PHA-stimulated PBMC resulted in HIV replication of 6,519 and 7,082 pg of p24/ml in culture supernatants (Fig. 2B; Table 1). No virus replication was detected in cultures containing only neutrophils with bound virus (Fig. 2B). Virus replication due to neutrophil-bound HIVTH and HIVGP was nine- and sixfold greater, respectively, than infection of PBMC with the same amount of cell-free virus (Table 1). Approximately, 12- and 7-fold more cell-free HIVTH and HIVGP, respectively, was needed to produce virus replication similar to neutrophil-bound virus infection of stimulated PBMC.

Replication of virus bound to fresh or PHA-stimulated PBMC was also assessed. Since the PBMC contain CD4+ cells that could be infected and contribute to virus replication in cocultures, the PBMC were irradiated to suppress infection of these cells before virus binding. Coculture of virus bound to irradiated fresh PBMC with PHA-stimulated PBMC resulted in 10- and 8-fold higher virus replication than similar amounts of cell-free HIVGP or HIVTH, respectively (Table 1). Only background levels of virus production were observed in cultures containing irradiated fresh PBMC with bound HIV. Virus bound to irradiated PHA-stimulated PBMC resulted in nine- and sevenfold higher virus replication than similar amounts of cell-free HIVGP and HIVTH, respectively (Table 1). However, irradiation only partially prevented virus replication in stimulated PBMC (Table 1). Similarly, virus bound to tonsil mononuclear cells also resulted in 9- and 12-fold increases in virus replication for HIVTH and HIVGP, respectively (Table 1). No virus replication was observed in irradiated tonsil cells cultured alone with bound virus.

Lastly, we assessed the ability of erythrocyte- and platelet-bound HIV to infect stimulated PBMC. Although erythrocyte- and platelet-bound virus was able to efficiently infect T cells, the enhancement over replication of cell-free virus was only two- to threefold (Table 1).

Bound HIV does not productively infect CD4− Raji cells.

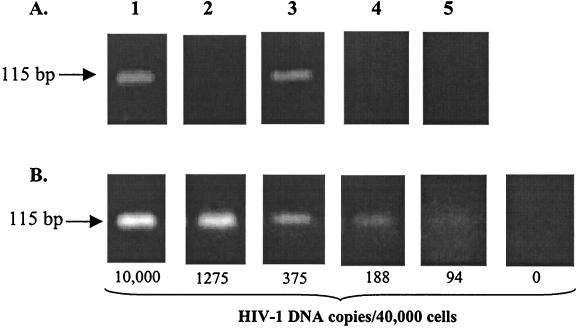

Culture of virus bound to CD4− cells with T cells resulted in marked increases in virus replication over replication due to cell-free virus. Experiments were performed to determine the mechanism of the enhanced virus replication. Since some reports have shown that HIV can infect B cells, we first determined whether replication of virus in Raji cells contributed to the increased virus production. Culture of Raji cells with bound virus for 7 days resulted in only background levels of virus replication (Fig. 2A and Table 1), indicating little or no infection of Raji cells. Since the assay of p24 in culture supernatants may not have been sensitive enough to detect low levels of virus infection in Raji cells, we used a previously described PCR method to detect HIV DNA in cultured Raji cells (27). While HIV DNA was detected in cocultures of Raji and H9 cells and in cultures with cell-free infection of H9 cells, no viral DNA was detected in Raji cells cultured alone with virus (Fig. 3). Since a faint band was observed with 94 copies of integrated viral DNA per 40,000 cells (Fig. 3B), fewer than 94 Raji cells were infected in cultures containing Raji cells alone with bound virus. In contrast, 375 to 1,250 HIV DNA copies per 40,000 cells were observed in cultures containing Raji and H9 cells.

FIG. 3.

HIV DNA in cells cultured with virus. Raji cells were incubated with HIVMN, washed, and cultured alone or with H9 cells as described in the legend to Fig. 2. After 7 days, DNA was isolated and the amount of DNA corresponding to 40,000 cells was PCR amplified using primers SK38 and SK39 (18, 27). Samples were run on agarose gels, and bands corresponding to the 115-bp amplified product were visualized by ethidium bromide staining. (A) HIV-1 DNA PCR. Images: 1, Raji cells with bound HIVMN cultured with H9 cells; 2, Raji cells with bound HIVMN cultured alone; 3, H9 cells infected with a large dose of cell-free HIVMN; 4, uninfected H9 cells; 5, Raji cells without virus. (B) Dilutions of 8E5/LAV cell DNA (numbers of HIV-1 DNA copies per 40,000 cells). For example, the image labeled 10,000 contained 10,000 8E5/LAV cells and 30,000 Raji cells as filler cells.

Raji cells do not stimulate virus replication in H9 cells.

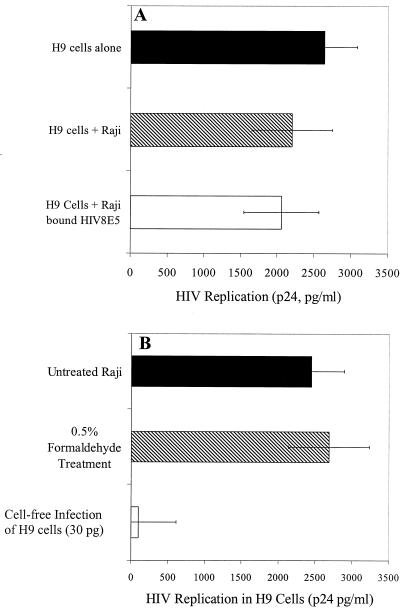

Another possible explanation for the increased virus replication in cultures of T cells with virus bound to Raji cells was that Raji cells may have enhanced virus replication by stimulating infected T cells through either cell-cell contact or release of soluble factors. To determine if Raji cells stimulate increased virus replication in H9 cells, H9 cells were infected with HIVMN and then cultured in the presence or absence of Raji cells. HIV replication in infected H9 cells was slightly suppressed by addition of Raji cells (Fig. 4A) (2,638 and 2,200 pg of p24/ml, respectively; P = 0.2, t test). To determine if virus binding could stimulate Raji cells and, in turn, stimulate virus expression in infected H9 cells, Raji cells were incubated with replication-defective HIV derived from 8E5/LAV cells before incubation with infected H9 cells. There was no increase in virus expression in the H9 cells when they were cocultured with Raji cells that had previously bound replication-defective virus (Fig. 4A; P = 0.58, t test).

FIG. 4.

Effect of Raji cells on virus replication in H9 T cells. (A) H9 cells were infected by overnight incubation with HIVMN. The next day, H9 cells were washed and cultured either alone or with untreated Raji cells or with Raji cells that had been incubated with noninfectious HIV8E5 and then washed. (B) Untreated Raji cells and Raji cells fixed with 0.5% formaldehyde were incubated with HIVMN, washed, and then cocultured with H9 cells. After 7 days, HIV replication in cultures was determined by p24 ELISA. In this experiment, 27 pg of p24 bound to unfixed Raji cells while 22 pg of p24 bound to fixed Raji cells. For comparison, virus replication levels are shown for H9 cells infected with 30 pg of cell-free virus. For both panels A and B, the results shown are the mean ± the standard deviation of replicate samples of one experiment that is representative of at least two experiments.

To further demonstrate that Raji cells did not produce virus or secreted molecules that enhanced HIV replication in H9 cells, we metabolically fixed the Raji cells with formaldehyde. We next bound virus to fixed Raji cells and subsequently cocultured them with H9 cells. The amount of virus binding to fixed Raji cells was similar to the amount of binding to untreated Raji cells (data not shown), and the levels of HIV replication during coculture were comparable to untreated Raji cell-bound infection of H9 cells (Fig. 4B). These results indicate that it is unlikely that a signal induced by Raji cells enhances virus replication in H9 cells.

Raji cells do not selectively bind infectious virus.

Another possible mechanism that could account for enhanced virus infection in the coculture system is Raji cell binding of only infection-competent virus particles. To determine whether Raji cells bind only infectious virus, we incubated HIVMN with Raji cells to allow virus binding. Cells were pelleted, and the remaining unbound virus was successively bound to fresh Raji cells for a total of three cycles. After each cycle of binding, the cells were washed and the percentage of bound virus was determined. Each successive round of Raji cell-bound virus was cocultured with H9 cells to determine the level of virus replication. Virus binding to Raji cells was similar (2.3, 2.6, and 2.5%) for each exposure of virus to Raji cells. The fold increase in virus infection due to the first round of bound virus (100%) was similar to that due to the successive two rounds of Raji-bound virus (91 and 118%), indicating that selective binding of infection-competent virus to Raji cells did not occur.

Blocking of cell-cell interactions inhibits cell-bound virus infection of T cells.

We next determined whether cell-cell interaction could mediate efficient transfer of virus from CD4− cells to T cells. Since previous studies showed that anti-LFA-1 antibody blocked HIV transfer from FDC to T cells, anti-CD18 (LFA-1β) antibody was added to the target T cells before coculture with virus bound to Raji cells and maintained throughout the culture. At 1 μg/ml, anti-LFA-1 antibody inhibited Raji-bound virus infection of H9 cells by 82% while a control antibody did not affect virus replication significantly (Table 2). Since incorporation of ICAM in HIV virions has been shown to enhance virus infectivity (9, 10), we also assessed the effect of anti-LFA-1 antibody treatment of T cells in cell-free virus infection. Consistent with previous studies, anti-LFA-1 antibody reduced cell-free infection of H9 cells, but by only 26% (Table 2). To determine if cell-cell interactions also contributed to the efficient infection of primary virus bound to primary cell types, PHA-stimulated PBMC were treated with anti-LFA-1 antibody before incubation with virus bound to neutrophils or tonsil mononuclear cells. As shown in Table 2, there was 70 to 93% inhibition of virus replication in PBMC that had been cultured in the presence of LFA-1 antibody. These experiments indicate that the interaction between cells plays an important role in transfer of virus from CD4− cells to CD4+ cells.

TABLE 2.

Blocking of cell adhesion through LFA-1 inhibits cell-bound virus infection of T cellsa

| Virus | % Inhibition

|

|

|---|---|---|

| LFA-1β antibody | CD14 isotype control antibody | |

| Cell-free HIVMN | 26 | 9 |

| Raji-bound HIVMN | 82 | 14 |

| Neutrophil bound | ||

| R5 HIVTH | 93 | NDb |

| X4 HIVGP | 93 | ND |

| Tonsil mononuclear cell bound | ||

| R5 HIVTH | 70 | ND |

| X4 HIVGP | 90 | ND |

Prior to cell-bound or cell-free virus infection, T cells were cultured with or without anti-LFA-1β antibody or an isotype control antibody to CD14. The percent inhibition of virus replication was determined.

ND, not determined.

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that TCLA HIV-1MN and primary isolates bind to cells that lack CD4. Although CD4 is considered to be the receptor for HIV, our data showing that HIV binds to neutrophils, Raji cells, CD4− PBMC, erythrocytes, and platelets indicate that binding of HIV can be independent of CD4. However, in CD4+ cells, including T cells, CD4 may be important for virus binding. For example, Mondor et al. showed that an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody partially blocked HIV binding to a T-cell line (23). Receptor-independent binding of virus particles to cells has been observed for several other viruses, including vesicular stomatitis virus (34, 35), Rous sarcoma virus (25, 29), and murine leukemia virus (MLV) (30). Studies by Pizzato et al. (30) showed that early phases of MLV attachment to cells did not require expression of virus receptors on the host cell. Furthermore, envelope-defective virus binding to cells was similar to binding of wild-type MLV. Studies with HIV suggest that CD4 is not always essential for virus attachment to cells. Mondor et al. (23) demonstrated that CD4− HeLa cells bind HIV at levels equivalent to HeLa cells expressing high or moderate levels of CD4. Studies by Saphire et al. showed that gp120-deficient HIV particles could bind to CD4+ HeLa cells, suggesting that the virus envelope proteins were not required for virus attachment (32). Glycoaminoglycans, specifically, heparan sulfates (14, 23, 26, 28), virus-incorporated adhesion molecules (9), and recently cyclophilin A (32), have been implicated as molecules responsible for the attachment of HIV to cells, although it is not known if HIV binds to all CD4− cells through these mechanisms.

The fact that HIV binds to a variety of cell types has significant implications. The observed binding could contribute to clearance of virus from plasma, since most of the cells in blood are CD4−. Virus binding could also lead to CD4-independent infection, induction of signaling pathways, and even apoptosis. We compared the infectivity of cell-bound virus with that of cell-free virus and found that cell-bound virus is highly infectious for T cells. The enhanced infectivity of cell-bound virus was not due to infection of CD4− cells, signaling, or selection of infectious particles. In contrast, anti-LFA-1 antibody significantly inhibited cell-bound virus infectivity but only marginally inhibited cell-free virus infection. Although other cell surface molecules could be important in virus transmission from cell to cell, our findings are consistent with other studies that demonstrated the importance of LFA-1 in cell-associated HIV transmission to target cells. Tsunetsugu-Yokota et al. showed that transmission of dendritic-cell (DC)-associated virus to T cells was substantially inhibited when LFA-1–ICAM-1 or LFA-3–CD2 interactions were blocked (39). Similarly, Kacani et al. demonstrated that anti-CD18 antibody inhibited transmission of non-syncytium-inducing strains of HIV from DCs to monocyte-derived macrophages (17). In those studies, immature DCs were more efficient than mature DCs at transferring HIV to monocyte-derived macrophages. The efficiency of virus transfer correlated with expression of β2 integrins CD11b, CD11c, and CD18.

In vivo, CD4+ T cells interconvert between a nonadherent state when in circulation to an adherent cell type when in lymphoid and other tissues (5). As CD4+ cells circulate through sites of inflammation, they become adherent and bind to a variety of antigen-presenting cells (APC) and non-APC. Although the interaction of CD4+ T cells with non-APC is transient (less than 30 min), this may allow virus transfer while, in contrast, antigen-dependent adhesion of cells can occur for hours to days (1, 5). In cell culture, stimulated T lymphocytes are capable of binding tightly to non-APC (5). When stimulated T lymphocytes bind to non-APC, the close proximity of cell membranes is likely to facilitate a much more efficient transfer of virus from the CD4− cell to the T cell. In contrast, at low concentrations of cell-free virus, the probability that a similar number of cell-free virus particles will bind to CD4+ T cells is low, due to Brownian motion and electrostatic inhibition (3). In our studies, CD4− cells with bound virus did not have to be metabolically active since formaldehyde fixation of the cells did not affect virus transfer. This interaction is analogous to the ability of formaldehyde-fixed APC to present antigen to T cells (40). Thus, fixed cells can participate in cell-cell adhesion. A recent study by Liao et al. demonstrated that 293 cells could bind and transfer HIV to permissive cells (21). When ICAM was expressed in these cells, the ability to bind virus was enhanced and, more importantly, the infection of permissive cells during coculture was substantially increased.

Since DCs are specialized to interact with T cells during antigen presentation, it is interesting to consider how the transfer of virus to T cells in our study compares to previous reports of DC transfer of virus to permissive cells. Several studies compared the efficiency of infection of DC-bound virus to that of cell-free virus. In those studies, enhanced infection by DC-bound virus, compared to cell-free infection, was similar to that observed in our study. For example, Kacani et al. (17) showed that DC-bound virus infection of monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages required 10-fold less virus than cell-free infection. Similarly, an earlier study by Tsunetsugu-Yokota et al. (39) demonstrated a 10-fold increase in virus replication over cell-free infection when T cells were infected by DC-bound HIV. Similar to our findings, both of those studies demonstrated that blocking of adhesion interactions during coculture reduced virus infection. Although the studies cited above revealed an efficiency of virus transfer to permissive cells similar to that shown by our studies, there appear to be several unique differences between DCs and the cells we studied. Thus, DCs express CD4 as well as X4 and R5. In addition, recent studies reported that DCs bind and capture virus through the DC-specific type C lectin (DC-SIGN) and internalize virus (12). Further, under some conditions, DCs become infected with HIV and therefore could cause cell-associated infection of neighboring cells, which is a mechanism of infection significantly different from the cell-bound enhancement of infection observed in our study. Furthermore, in addition to delivering virus, it is also possible that DCs can stimulate permissive cells to enhance HIV replication (17, 39).

Interestingly, it appears that the efficiency of virus infection of T cells depends on the type of cells with bound virus. In our studies, virus bound to neutrophils and lymphocytes more efficiently infected T cells than did virus bound to platelets and erythrocytes. This suggests that some cell types, including nonnucleated erythrocytes and platelets, have less contact with T cells while other cell types express relatively higher levels of complementary adhesion and immune recognition molecules and participate in more interactions with CD4+ T cells. Therefore, it stands to reason that cells with tighter cell-cell binding with CD4+ T cells can transfer virus to T cells more efficiently.

Binding of HIV to CD4− cells could be important during transmission of HIV infection. During transmission, numerous uninfected cell types could carry bound virus into the new host or cell-free virus could bind to a variety of CD4− host cells. Additionally, cell-free virus that is transferred during transmission is more likely to come into contact with CD4− cells since they are more predominant. For example, cell-free virus introduced into the bloodstream of an uninfected subject would most likely bind to erythrocytes, platelets, and neutrophils since <0.1% of blood cells are CD4+. Although CD4− cells may be nonpermissive to HIV infection, our studies suggest that bound virions remain infectious to CD4+ T cells. Moreover, some CD4− cell types with bound virus could distribute virus to sites that contain activated target cells. Another implication of these findings is that plasma viremia does not accurately represent the total virus load in blood since only cell-free virus is measured. Since cell-bound virus more efficiently infects T cells, this undetected population of virus could represent a potentially important reservoir of virus in vivo.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant AI-31812 from the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.

We thank Neeta Shenoy for assistance in isolating neutrophils and Shauna Lasky for help with pilot studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ben-Sasson S Z, Lipscomb M F, Tucker T F, Uhr J W. Specific binding of T lymphocytes to macrophages. III. Spontaneous dissociation of T cells from antigen-pulsed macrophages. J Immunol. 1978;120:1902–1906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carr J M, Hocking H, Li P, Burrell C J. Rapid and efficient cell-to-cell transmission of human immunodeficiency virus infection from monocyte-derived macrophages to peripheral blood lymphocytes. Virology. 1999;265:319–329. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chuck A S, Clarke M F, Palsson B O. Retroviral infection is limited by Brownian motion. Hum Gene Ther. 1996;7:1527–1534. doi: 10.1089/hum.1996.7.13-1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimitrov D S, Willey R L, Sato H, Chang L J, Blumenthal R, Martin M A. Quantitation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection kinetics. J Virol. 1993;67:2182–2190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.2182-2190.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dustin M L, Springer T A. Role of lymphocyte adhesion receptors in transient interactions and cell locomotion. Annu Rev Immunol. 1991;9:27–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finzi D, Silliciano R F. Viral dynamics in HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1998;93:665–671. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fiscus S A, Folds J D, van der Horst C M. Infectious immune complexes in HIV-1-infected patients. Viral Immunol. 1993;6:135–141. doi: 10.1089/vim.1993.6.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Folks T M, Powell D, Lightfoote M, Koenig S, Fauci A S, Benn S, Rabson A, Daugherty D, Gendelman H E, Hoggan M D, et al. Biological and biochemical characterization of a cloned Leu-3-cell surviving infection with the acquired immune deficiency syndrome retrovirus. J Exp Med. 1986;164:280–290. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.1.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fortin J F, Cantin R, Lamontagne G, Tremblay M. Host-derived ICAM-1 glycoproteins incorporated on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are biologically active and enhance viral infectivity. J Virol. 1997;71:3588–3596. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.3588-3596.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fortin J F, Cantin R, Tremblay M J. T cells expressing activated LFA-1 are more susceptible to infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 particles bearing host-encoded ICAM-1. J Virol. 1998;72:2105–2112. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2105-2112.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujiwara M, Tsunoda R, Shigeta S, Yokota T, Baba M. Human follicular dendritic cells remain uninfected and capture human immunodeficiency virus type 1 through CD54-CD11a interaction. J Virol. 1999;73:3603–3607. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.5.3603-3607.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geijtenbeek T B, Kwon D S, Torensma R, van Vliet S J, van Duijnhoven G C, Middel J, Cornelissen I L, Nottet H S, KewalRamani V N, Littman D R, Figdor C G, van Kooyk Y. DC-SIGN, a dendritic cell-specific HIV-1-binding protein that enhances trans-infection of T cells. Cell. 2000;5:587–597. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80694-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heath S L, Tew J G, Szakal A K, Burton G F. Follicular dendritic cells and human immunodeficiency virus infectivity. Nature. 1995;377:740–744. doi: 10.1038/377740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ibrahim J, Griffin P, Coombe D R, Rider C C, James W. Cell-surface heparan sulfate facilitates human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry into some cell lines but not primary lymphocytes. Virus Res. 1999;60:159–169. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(99)00018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jakubik J J, Saifuddin M, Takefman D M, Spear G T. B lymphocytes in lymph nodes and peripheral blood are important for binding immune complexes containing HIV-1. Immunology. 1999;96:612–619. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00304.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jakubik J J, Saifuddin M, Takefman D M, Spear G T. Immune complexes containing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolates bind to lymphoid tissue B lymphocytes and are infectious for T lymphocytes. J Virol. 2000;74:552–555. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.552-555.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kacani L, Frank I, Spruth M, Schwendinger M G, Müllauer B, Sprinzl G M, Steindl F, Dierich M P. Dendritic cells transmit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. J Virol. 1998;72:6671–6677. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6671-6677.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kwok S, Sninsky M D H, J J, Ehrlich G D, Poiesz B J, Dock N L, Alter H J, Mildvan D, Grieco M H. Diagnosis of human immunodeficiency virus in seropositive individuals: enzymatic amplification of HIV viral sequences in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. New York, N.Y: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lachgar A, Jaureguiberry G, Le Buenac H, Bizzini B, Zagury J F, Rappaport J, Zagury D. Binding of HIV-1 to RBCs involves the Duffy antigen receptors for chemokines (DARC) Biomed Pharmacother. 1998;52:436–439. doi: 10.1016/s0753-3322(99)80021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lahm H W, Stein S. Characterization of recombinant human interleukin-2 with micromethods. J Chromatogr. 1985;326:357–361. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)87461-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liao Z, Roos J R, Hildreth J E K. Increase infectivity of HIV type 1 particles bound to cell surface and solid-phase ICAM-1 and VCAM-1 through acquired adhesion molecules LFA-1 and VLA-4. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2000;16:355–366. doi: 10.1089/088922200309232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McDougal J S, Hubbard M, Nicholson J K, Jones B M, Holman R C, Roberts J, Fishbein D B, Jaffe H W, Kaplan J E, Spira T J, et al. Immune complexes in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): relationship to disease manifestation, risk group, and immunologic defect. J Clin Immunol. 1985;5:130–138. doi: 10.1007/BF00915011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mondor I, Ugolini S, Sattentau Q J. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 attachment to HeLa CD4 cells is CD4 independent and gp120 dependent and requires cell surface heparans. J Virol. 1998;72:3623–3634. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3623-3634.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morrow W J, Wharton M, Stricker R B, Levy J A. Circulating immune complexes in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome contain the AIDS-associated retrovirus. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1986;40:515–524. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(86)90196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Notter M F, Leary J F, Balduzzi P C. Adsorption of Rous sarcoma virus to genetically susceptible and resistant chicken cells studied by laser flow cytometry. J Virol. 1982;41:958–964. doi: 10.1128/jvi.41.3.958-964.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ohshiro Y, Murakami T, Matsuda K, Nishioka K, Yoshida K, Yamamoto N. Role of cell surface glycosaminoglycans of human T cells in human immunodeficiency virus type-1 (HIV-1) infection. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:827–835. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ou C Y, Kwok S, Mitchell S W, Mack D H, Sninsky J J, Krebs J W, Feorino P, Warfield D, Schochetman G. DNA amplification for direct detection of HIV-1 in DNA of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Science. 1988;239:295–297. doi: 10.1126/science.3336784. . (Erratum, 240:240.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patel M, Yanagishita M, Roderiquez G, Bou-Habib D C, Oravecz T, Hascall V C, Norcross M A. Cell-surface heparan sulfate proteoglycan mediates HIV-1 infection of T-cell lines. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1993;9:167–174. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piraino F, Krumbiegel E R, Wisniewski H J. Serologic survey of man for avian leukosis virus infection. J Immunol. 1967;98:702–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pizzato M, Marlow S A, Blair E D, Takeuchi Y. Initial binding of murine leukemia virus particles to cells does not require specific Env-receptor interaction. J Virol. 1999;73:8599–8611. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8599-8611.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ramratnam B, Bonhoeffer S, Binley J, Hurley A, Zhang L, Mittler J E, Markowitz M, Moore J P, Perelson A S, Ho D D. Rapid production and clearance of HIV-1 and hepatitis C virus assessed by large volume plasma apheresis. Lancet. 1999;354:1782–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02035-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saphire A C, Bobardt M D, Gallay P A. Host cyclophilin A mediates HIV-1 attachment to target cells via heparans. EMBO J. 1999;18:6771–6785. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.23.6771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sato H, Orenstein J, Dimitrov D, Martin M. Cell-to-cell spread of HIV-1 occurs within minutes and may not involve the participation of virus particles. Virology. 1992;186:712–724. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90038-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlegel R, Wade M. Neutralized vesicular stomatitis virus binds to host cells by a different “receptor.”. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1983;114:774–778. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(83)90848-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schlegel R, Willingham M C, Pastan I H. Saturable binding sites for vesicular stomatitis virus on the surface of Vero cells. J Virol. 1982;43:871–875. doi: 10.1128/jvi.43.3.871-875.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sullivan B L, Knopoff E J, Saifuddin M, Takefman D M, Saarloos M N, Sha B E, Spear G T. Susceptibility of HIV-1 plasma virus to complement-mediated lysis. Evidence for a role in clearance of virus in vivo. J Immunol. 1996;157:1791–1798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sullivan B L, Takefman D M, Spear G T. Complement can neutralize HIV-1 plasma virus by a C5-independent mechanism. Virology. 1998;248:173–181. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takefman D M, Sullivan B L, Sha B E, Spear G T. Mechanisms of resistance of HIV-1 primary isolates to complement-mediated lysis. Virology. 1998;246:370–378. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsunetsugu-Yokota Y, Yasuda S, Sugimoto A, Yagi T, Azuma M, Yagita H, Akagawa K, Takemori T. Efficient virus transmission from dendritic cells to CD4+ T cells in response to antigen depends on close contact through adhesion molecules. Virology. 1997;239:259–268. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ziegler K, Unanue E R. Identification of a macrophage antigen-processing event required for I-region-restricted antigen presentation to T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1981;127:1869–1875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]