Abstract

Background and Aims

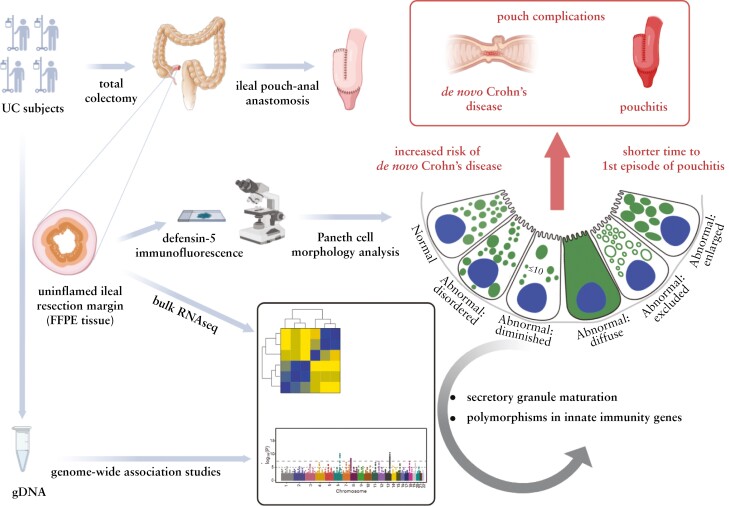

Biomarkers that integrate genetic and environmental factors and predict outcome in complex immune diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD; including Crohn’s disease [CD] and ulcerative colitis [UC]) are needed. We showed that morphological patterns of ileal Paneth cells (Paneth cell phenotype [PCP]; a surrogate for PC function) is one such cellular biomarker for CD. Given the shared features between CD and UC, we hypothesised that PCP is also associated with molecular/genetic features and outcome in UC. Because PC density is highest in the ileum, we further hypothesised that PCP predicts outcome in UC subjects undergoing total colectomy and ileal pouch-anal anastomosis [IPAA].

Methods

Uninflamed ileal resection margins from UC subjects with colectomy and IPAA were used for PCP and transcriptomic analyses. PCP was defined using defensin 5 immunofluorescence. Genotyping was performed using Immunochip. UC transcriptomic and genotype associations of PCP were incorporated with data from CD subjects to identify common IBD-related pathways and genes that regulate PCP.

Results

The prevalence of abnormal ileal PCP was 27%, comparable to that seen in CD. Combined analysis of UC and CD subjects showed that abnormal PCP was associated with transcriptomic pathways of secretory granule maturation and polymorphisms in innate immunity genes. Abnormal ileal PCP at the time of colectomy was also associated with pouch complications including de novo CD in the pouch and time to first episode of pouchitis.

Conclusions

Ileal PCP is biologically and clinically relevant in UC and can be used as a biomarker in IBD.

Keywords: Pouchitis, de novo Crohn’s disease, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Abnormal Paneth cell phenotype in ulcerative colitis subjects is associated with poor outcome, genetics, and ileal transcriptomic changes.

1. Introduction

The pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis [UC], a major subtype of inflammatory bowel disease [IBD], involves host genetic susceptibility, immune dysregulation, and potential environmental triggers.1 Identifying biomarkers that can synthesise the effects of these pathogenic factors and additionally correlate with clinical outcome will greatly improve clinical management of UC subjects.2 Several biomarkers have been shown to correlate with levels of tissue inflammation in UC [eg, oncostatin-M, PAI-1].3,4 However, whether these biomarkers predict disease course remains unclear.

We propose that biomarkers that are identified in uninflamed intestinal tissue at the time of sampling and can integrate the impact of various genetic and environmental factors, may advance our understanding of disease pathogenesis. This is because they are free of interference from direct effects of active inflammation and may provide unique molecular insight into disease trajectory. Using this approach, we previously showed that in Crohn’s disease [CD, another major IBD subtype], morphology patterns of Paneth cells [Paneth cell phenotype] can be used as a surrogate read-out for Paneth cell secretory function.5,6 Paneth cells predominantly reside in the small intestine,7 and are critical for innate immunity by producing, packaging, and secreting antimicrobial peptides that are highly resistant to proteolysis and persist as function forms throughout small intestine and colon.8–11 We showed that Type I [abnormal] Paneth cell phenotype in uninflamed ileal tissue correlates with CD genetics, environmental risk factors [cigarette smoking], mucosal microbiota, transcriptomic changes, and poor clinical outcome.12–16 Importantly, the association between abnormal Paneth cell phenotype and aggressive CD outcome has been reproduced by others.17,18

Given the shared pathological and genetic underpinnings between CD and UC, we hypothesised that abnormal Paneth cell phenotype correlates with clinical outcome in UC. UC is usually limited to colon, but those with medically refractive disease or UC-related dysplasia often require total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch-anal anastomosis [IPAA], in which diseased colon and rectum are removed and bowel continuity is restored through IPAA.1 These subjects often suffer from complications of the ileal pouch, such as pouchitis, which can affect half of these subjects.1,19,20 In addition, the development of de novo CD in the ileal pouch is associated with significant morbidity, including obstruction and pouch failure.20–23 As Paneth cell density is highest in the ileum, we further hypothesised that abnormal Paneth cell phenotype in uninflamed ileal tissue at the time of UC total colectomy would be associated with the development of pouch complications in IPAA.

Herein we showed that abnormal Paneth cell phenotype in uninflamed ileal tissue in UC subjects with IPAA is as prevalent as in CD subjects. By combining data from both UC and CD cohorts, we identified genetic factors and molecular pathways linked to abnormal Paneth cell phenotype. Finally, we showed that abnormal Paneth cell phenotype is associated with the development of de novo CD and time to first pouchitis episode. Paneth cell phenotype may therefore be applied as a universal cellular biomarker for poor disease course in IBD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study population and disease characteristics

In this retrospective study, UC subjects with total colectomy and IPAA construction performed between 2007 and 2019 were identified by review of medical records. The following demographic information was collected: age, gender, age at diagnosis, age at surgery, smoking status, indications for surgery [medically refractory disease versus dysplasia or cancer], and type of surgery [two-stage or three-stage total proctocolectomy with IPAA]. Subjects with less than 3 months of follow-up after surgery, or those prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs after colectomy, were excluded.

2.2. Diagnostic criteria for IBD and pouchitis

We used the following criteria to establish the diagnoses of IBD. [1] UC was diagnosed based on characteristic pattern of involvement of colon, lack of perianal fistula or fistulising disease, and no histological evidence of chronic injury in terminal ileum.1,19 [2] De novo CD of the pouch after IPAA was diagnosed either when mucosal inflammation involved the small-bowel mucosa proximal to the ileal pouch after surgery [more than 12 months post surgery], development of fistula 6–12 months after pouch construction, ie, late development of fistula, development of other perianal complication, or involvement of other sites in the gastrointestinal tract [skip lesions, or segmental disease].20,23 [3] Pouchitis was defined using a constellation of clinical, endoscopic, and histological features.20 Clinical symptoms included increase in stool frequency, bloody diarrhoea, tenesmus, urgency, and sometimes fever.19 The diagnosis of pouchitis was confirmed in all cases by pouchoscopy and histology with examination of the ileal afferent limb.19 Endoscopically, pouchitis was defined as having the following findings: erythema, loss of vascular pattern, erosions, or ulcerations with sparing of the afferent ileal segment.19 Acute pouchitis was defined as inflammation of the pouch that lasted less than 4 weeks and responded favourably to antibiotic treatment.19,20 Chronic pouchitis was defined as inflammation of the pouch lasting more than 4 weeks.19,20 Pouchitis was further classified based on the response to antibiotics into antibiotics-responsive, antibiotics-dependent, and antibiotics-refractory pouchitis.19,20

2.3. Paneth cell phenotype analysis

Paneth cell phenotype analysis was performed using tissue sections from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded [FFPE] tissue blocks of the proximal ileal resection margins of UC total colectomy. To be included in the study, the proximal ileal margin of a UC colectomy must [a] be histologically normal with no acute inflammation, ie, without backwash ileitis, and [b] have at least 50 well-oriented ileal crypts for Paneth cell phenotype evaluation as previously described.6

Human defensin 5 immunofluorescence was performed and interpreted in a blinded fashion as described previously.5,6,13,16 For each qualified ileal margin, every Paneth cell was classified into normal or one of the five abnormal categories, including: disordered, defined as abnormality in distribution and size of the granules; diminished, with ≤ 10 granules; diffuse, defined as a smear of defensin within the cytoplasm with no recognisable granules; excluded, where majority of the granules do not contain stainable material; and enlarged, with rare megagranules.6,13 Paneth cell phenotype of a patient was then defined by the percentage of total abnormal Paneth cells in the ileal margin. Type I Paneth cell phenotype was defined as 20% or more [≥ 20%] of total Paneth cells showing abnormal morphology patterns, whereas Type II Paneth cell phenotype was defined as less than 20% [< 20%] of total Paneth cells showing morphological defects.13–16

2.4. Transcriptomic profiling and analysis

Tissue sections of FFPE ileal resection margin were used to isolate RNA using RNeasy FFPE Kit [QIAGEN; # 73504] according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Transcriptomic profiling was performed at the Genome Technology Access Center at Washington University, which has previously performed bulk RNA sequencing [RNA-seq] on similar tissues in CD.15 Differential gene lists were analysed using CompBio.24 Please see Supplementary Methods for additional details regarding transcriptomic profiling and CompBio analysis.

2.5. Genetic association analysis with Paneth cell phenotype

A subset of the UC subjects with colectomy and IPAA had peripheral blood samples available for genotyping. Genotyping was performed using the Illumina Infinium Immunochip array per manufacturer’s protocol [Illumina, San Diego, CA]. Samples with first-degree relation, non-European ancestry [as defined by < 70% European admixture],25 genotype missingness > 5%, and single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs] with missingness > 5% and minor allele frequency [MAF] < 1% were excluded from analysis. Included in analysis were 111 713 variants and 723 IBD subjects [474 CD; 249 UC] with available Paneth cell phenotype. Please see Supplementary Methods for additional details regarding SNP genotyping. Pathway analysis was performed using CompBio [V2.0—PercayAI].24

2.6. Statistical analysis

Permutation test was used to establish significance of individual SNPs in genome-wide association studies [GWAS] and correct correlation among SNPs caused by linkage disequilibrium. Comparison of Paneth cell phenotype between different groups, as well as comparisons of demographics and key clinical factors between different groups, were performed using Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis tests followed by Dunn’s tests between groups. Correlations between Paneth cell phenotype and the development or not of de novo CD, various classes of pouchitis, were performed using Fisher’s exact test [for binary variables] or chi square test. Logistic regression was performed to analyse the predictive association of key clinical factors in the development of de novo CD and generate receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curve. Kaplan–Meier analysis and univariate and multivariable Cox regression analysis were used to correlate Paneth cell phenotype and time to pouchitis development. Time to first episode of pouchitis was defined as the period between subtotal colectomy and the onset of first episode of pouchitis. Proportional hazard assumption was checked and met when performing Cox regression analysis. All tests were two-tailed and a p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant. Data were plotted and analysed using GraphPad Prism [version 8.30] and SPSS [version 27.0.0.0]. All data represent mean ± standard deviation [SD]. All statistical details of the experiments can be found in the figure legends, including the statistical tests used and exact value of n.

2.7. Ethical statement

All research activities in this study were approved by the institutional review boards at Washington University School of Medicine [#201209047], University of Pittsburgh [#20050153], and Cedars-Sinai Medical Center [#3358].

2.8. Data deposition

Bulk RNA-seq data were deposited in ArrayExpress [accession number: E-MTAB-12826].

2.9. Sex as a biological variable

Our study examined male and female UC subjects with IPAA, and similar findings are reported for both sexes.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

The flowchart of the study is shown in Figure 1A. A total of 459 UC subjects from three medical centres who underwent total colectomy with IPAA and had no active inflammation at ileal resection margin were included. The mean age at surgery was 37 years [SD: 15]. There were 224 [49%] males. Because we previously observed the connection between cigarette smoking and Paneth cell defects in CD,15 we also defined the smoking status and found that 43 [10%] were active smokers and 63 [14%] former smokers. Subjects were followed for 49 months on average [interquartile range: 59 months]. Details of the subjects’ characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Type I Paneth cell phenotype was prevalent in UC subjects with IPAA. [A] Flowchart of UC subjects stratified by clinical outcome after colectomy and IPAA. [B] Diagram of Paneth cell phenotype classification under human defensin 5 immunofluorescence. Each Paneth cell can be classified into normal or one of the five abnormal categories: disordered, diminished, diffuse, excluded, and enlarged. Diagram was prepared in BioRender. [C] Representative photomicrographs of Paneth cells in specimens from UC subjects with Type I and II Paneth cell phenotypes. Type I Paneth cell phenotype was defined as ≥ 20% of total Paneth cells showing abnormal morphology patterns. Type II Paneth cell phenotype was defined as < 20% of total Paneth cells showing morphological defects. Green: human defensin 5; blue: Hoechst stain. Scale bars: 10 µm. Paneth cells are outlined in white. Crypt unit is outlined by dashed line in white. [D] Comparison of Paneth cell phenotype distribution between UC total colectomy and IPAA samples [n = 459] and CD resection samples [n = 420]. Both cohorts showed similar prevalence of type I Paneth cell phenotype [p > 0.05 by Fisher’s exact test]. UC, ulcerative colitis; IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; CD, Crohn’s disease.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of UC/IPAA subjects stratified by outcomes. Statistical analysis between subgroups was performed using Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables or Fisher’s exact test between groups for binary variables.

| Total | Neither pouchitis nor de novo CD | Pouchitis | De novo CD | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neither pouchitis nor de novo CD vs pouchitis | Pouchitis vs de novo CD | Neither pouchitis nor de novo CD vs de novo CD | |||||

| No. of subjects n [%] | 459 | 200 [44] | 134 [29] | 125 [27] | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Age at surgery [years; mean ± SD] | 37 ± 15 | 39 ± 15 | 36 ± 14 | 34 ± 15 | 0.074 | 0.45 | 0.01 |

| Male/female [n, %/n] | 224 [49]/235 | 95 [48]/105 | 70 [52]/64 | 59 [47]/66 | 0.435 | 0.456 | 1.0 |

| Duration of disease prior to colectomy [months; mean ± SD] | 123 ± 122 | 118 ± 117 | 155 ± 132 | 107 ± 119 | 0.029 | 0.006 | 0.333 |

| Stage of surgery; n [%] | 420 | 195 | 126 | 99 | <0.001 | 0.008 | 1.0 |

| 2-stage | 40 [10] | 11 [6] | 23 [18] | 6 [6] | |||

| 3-stage | 380 [90] | 184 [94] | 103 [82] | 93 [94] | |||

| Smoking status; n [%] | 443 | 192 | 129 | 122 | |||

| Never smoker | 337 [76] | 151 [79] | 92 [71] | 94 [77] | 0.146 | 0.780 | 0.316 |

| Former smoker | 63 [14] | 30 [16] | 16 [12] | 17 [14] | 0.516 | 0.747 | 0.852 |

| Active smoker | 43 [10] | 11 [6] | 21 [16] | 11 [9] | 0.004 | 0.268 | 0.092 |

UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease; IPAA, ileal pouch-anal anastomosis; N/A, non applicable; SD, standard deviation.

3.2. Type I [abnormal] Paneth cell phenotype was prevalent in UC

We first determined the prevalence of abnormal Paneth cell phenotype in uninflamed ileal resection margin in UC subjects with total colectomy and IPAA. A diagram of Paneth cell morphology patterns, based on human defensin 5 immunofluorescence,6 is shown in Figure 1B, and representative photomicrographs of Paneth cell staining patterns in UC subjects with Type I [abnormal] and Type II [normal] Paneth cell phenotypes are shown in Figure 1C. We found that the prevalence of Type I Paneth cell phenotype was 27% [124/459] in the uninflamed ileal resection margin in UC subjects with total colectomy and IPAA, which was comparable to 21% [90/420] observed in uninflamed ileal margins in adult CD resections13–16 [Figure 1D]. Type I Paneth cell phenotype was more often seen in females compared with Type II Paneth cell phenotype [73/124, 59% vs 162/335, 48%, respectively, p = 0.047; Supplementary Table 1]. Unlike our findings in CD, Paneth cell phenotype was not associated with smoking in UC [Supplementary Table 1], which is consistent with the different roles of smoking reported in CD and UC.1,26,27

3.3. Type I Paneth cell phenotype was associated with dysregulated secretory granule formation transcriptomic signatures in IBD

We then analysed transcriptomic alterations associated with Paneth cell phenotype in our cohort of UC colectomies that had additional ileal tissue available [n = 56] using bulk RNA-seq. Since Paneth cell phenotype was defined by human defensin 5 immunofluorescence, we first correlated Paneth cell phenotype with expression of alpha defensin 5 [DEFA5] and alpha defensin 6 [DEFA6]. Expression of DEFA5 and DEFA6 was similar in ileal margins with type I [abnormal] and type II Paneth cell phenotype [p > 0.05 for both, Student’s t test] [Supplementary Figure 1]. This is consistent with our previous data showing that Type I Paneth cell phenotype is associated with defective Paneth cell secretory function, rather than antimicrobial peptide production per se.5 The result also suggests that Paneth cell phenotype, rather than the expression of Paneth cell antimicrobial peptides, may be a more clinically relevant biomarker. However, the interpretation of this result may also reflect the limit of bulk RNA-seq in differentiating expression status in low-abundance cell type such as Paneth cells.

Bulk RNA-seq data were further analysed by a novel knowledge engine, CompBio,24 to define the molecular pathways associated with Paneth cell phenotype. Transcriptomic themes that positively associated with the percentages of normal Paneth cells included processes involving maturation of secretory granules [endosomal sorting complex required for transport; ESCRT28], SNARE complex,29 ubiquitin, spliceosome, and genes associated with circadian regulation, SWI/SNF chromatin-remodelling complex, and histone demethylation [Figure 2A]. Transcriptomic themes negatively associated with the percentages of normal Paneth cells included ionic channels and a variety of metabolic pathways [Supplementary Figure 2]. We also compared the findings with CD resection samples [n = 157] that we have previously analysed.30 Interestingly, when UC and CD datasets were compared, we found common transcriptomic themes that positively associated with the percentages of normal Paneth cells, including ESCRT, SNARE complex, vesicle scission, and clathrin-independent pinocytosis [Figure 2B; and Supplementary Table 2], suggesting these are molecular processes underlying Paneth cell phenotype defects in IBD.

Figure 2.

Transcriptomic themes associated with Paneth cells phenotypes in IBD subjects. [A] Transcriptomic themes that were positively associated with percentages of normal Paneth cells in UC samples included themes associated with secretory granule maturation, spliceosome, ubiquitination, and epigenetic regulations. [B] Overlapping themes between CD and UC that positively correlated with the percentages of normal Paneth cells. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease.

3.4. Genetic associations with Paneth cell phenotype in IBD

We next hypothesised that genetic susceptibility may be associated with Paneth cell phenotypes in IBD subjects, as we have shown in CD.5,13,16 We performed association analysis using both hypothesis-driven and hypothesis-free [unbiased] approaches that we have previously applied14 [Figure 3A] to expand our knowledge on known genes associated with Paneth cell phenotype and identify novel genetic determinants for Paneth cell defects in IBD.

Figure 3.

Genetic determinants of Paneth cell phenotype in IBD. [A] Flowchart demonstrating genes from both hypothesis-driven and hypothesis-free approaches were included in analysis. [B] Genes associated with Paneth cell phenotype were involved in the following molecular pathways: innate immunity signalling [autophagosome, inflammasome complex, antigen processing and presentation], Parkinsonism and neural development, aryl hydrocarbon receptor [AhR] signalling, mitochondria function, Rho/Rac cytoskeletal reorganisation, and ulcerative colitis. Analysis was performed using CompBio. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

The hypothesis-driven approach included analysis of genes known to affect Paneth cell function [including ATG16L1,5NOD2,31 and LRRK214], as well as the novel genes we identified by bulk RNA-seq analysis [Figure 2B; and Supplementary Table 2]. We observed association between single nucleotide polymorphisms [SNPs] in known genes and Paneth cell phenotype: ATG16L1 [rs3792106 in LD r2 = 0.8 with rs2241880/T300A pperm = 2.79 × 10-3], LRRK2 [rs4768224 pperm = 6.95 × 10-4; rs33995883/N2081D pperm = 3.99 × 10-3], and NOD2 [rs2066845/G908R pperm = 9.56 × 10-4] [Table 2]. Genetic associations with Paneth cell phenotype and variants in/near novel genes implicated by bulk RNA-seq analysis lent further support for a role for these genes in Paneth cell biology. Associations observed included EIF2AK2 [rs11895771, an eQTL for EIF2AK2 in whole blood, pperm = 3.31 × 10-3], and NPEPPS [rs4793978, an eQTL for NPEPPS in sigmoid and transverse colon, terminal ileum, and whole blood, pperm = 2.90 × 10-2], among others [Supplementary Table 3].

Table 2.

Genetic variants associated with Paneth cell phenotype in genes known to affect Paneth cell function. Hypothesis-driven analysis identified variants in genes previously implicated with Paneth cell function to be associated with Paneth cell phenotype.

| CHR | Position [hg19] | SNP | Gene | Allele | N | OR | 95% lower CI | 95% upper CI | p-value | Permuted p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 234190740 | rs3792106 | ATG16L1 | A | 723 | 1.25 | 1.08 | 1.45 | 3.52 × 10-3 | 2.79 × 10-3 |

| 12 | 40661403 | rs4768224 | LRRK2 | A | 723 | 5.97 | 2.12 | 16.79 | 7.58 × 10-4 | 6.95 × 10-4 |

| 12 | 40740686 | rs33995883 N2081D | LRRK2 | G | 723 | 1.86 | 1.30 | 2.67 | 8.08 × 10-4 | 3.99 × 10-3 |

| 16 | 50756540 | rs2066845 SNP12 G908R | NOD2 | G | 723 | 7.30 | 3.31 | 16.07 | 9.94 × 10-7 | 9.56 × 10-4b |

CHR, chromosome; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; allele, effect allele; N, sample size, inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] subjects included in analysis; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a1 M permutations unless otherwise noted.

b100 M permutations.

In contrast, the hypothesis-free approach [genome-wide association study; GWAS] evaluated SNPs associated with Paneth cell phenotype in IBD subjects on a genome-wide basis, without prior knowledge of phenotype-genotype association [Figure 3A]. Given the shared genetic pleiotropy between UC and CD, and to increase power and define genes that may inform Paneth cell function, we included data from a subset of the UC subjects in this cohort with genotype data [n = 249] and 474 CD subjects who had been previously genotyped and analysed for Paneth cell phenotype13,14 [Figure 3A]. We found that SNPs in 36 genomic loci [mapped to 53 genes] were associated with quantitative Paneth cell phenotype [pperm < 0.0001], including three nonsynonymous SNPs with pperm < 0.00001 in NXPE1 [rs10891692 pperm = 2.97 × 10-5], WDFY4 [rs61742644 pperm = 4.66 × 10-5], and FAM205A [rs117956208 pperm = 4.83 × 10-5] [Table 3]. Ten SNPs demonstrated genome-wide significance [punadjusted < 5 × 10-8], although no SNPs achieved genome-wide thresholds with permutation testing [Table 3], likely due to the limited sample size.

Table 3.

Variants associated with Paneth cell phenotype in IBD by GWAS. Hypothesis-free approach identified variants associated with Paneth cell phenotype [permuted p < 0.0001].

| CHR | Position [hg19] | SNP | Gene | Allele | N | OR | 95% lower CI | 95% upper CI | p-value | Permuted p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 151996692 | rs13001465 | LOC101929282;RBM43 | A | 580 | 1.14 | 1.08 | 1.20 | 1.93 × 10-6 | 6.00 × 10-7 |

| 3 | 159625545 | rs9872563 | IQCJ-SCHIP1;IL12A-AS1 | G | 580 | 1.28 | 1.18 | 1.39 | 1.51 × 10-9 | 1.55 × 10-6b |

| 17 | 38868948 | rs17556609 | KRT24;KRT25 | G | 723 | 24.41 | 12.34 | 48.23 | 4.14 × 10-19 | 3.66 × 10-6b |

| 5 | 35995504 | rs78502023 | UGT3A1 | A | 723 | 48.14 | 11.05 | 209.77 | 3.25 × 10-7 | 4.20 × 10-6b |

| 11 | 71221331 | rs7950649 | NADSYN1;KRTAP5-7 | A | 723 | 9.27 | 3.62 | 23.76 | 4.10 × 10-6 | 7.30 × 10-6 |

| 5 | 147219925 | rs4705206 | SPINK1;SCGB3A2 | G | 580 | 1.52 | 1.35 | 1.72 | 5.94 × 10-11 | 7.35 × 10-6b |

| 5 | 96025847 | rs152005 | CAST | G | 723 | 0.06 | 0.02 | 0.21 | 8.88 × 10-6 | 1.47 × 10-5 |

| 7 | 128729699 | rs77729114 | TPI1P2;LOC407835 | C | 723 | 26.66 | 12.73 | 55.76 | 2.03 × 10-17 | 1.66 × 10-5b |

| 1 | 22705781 | rs12748226 | MIR4418;ZBTB40 | A | 580 | 2.65 | 2.10 | 3.34 | 1.07 × 10-15 | 1.91 × 10-5b |

| 6 | 31345376 | rs2442744 | HLA-B;MICA | A | 723 | 5.07 | 2.43 | 10.58 | 1.77 × 10-5 | 2.00 × 10-5 |

| 14 | 96105893 | rs7157925 | LINC02318;TCL6 | G | 723 | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.30 | 2.10 × 10-5 | 2.17 × 10-5 |

| 6 | 128201396 | rs79385097 | THEMIS | A | 723 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.06 × 10-7 | 2.27 × 10-5b |

| 4 | 32606701 | rs1838624 | LINC02353;LOC101928622 | A | 723 | 1.35 | 1.17 | 1.57 | 6.77 × 10-5 | 2.35 × 10-5 |

| 11 | 114393652 | rs10891692 | NXPE1 | A | 723 | 3.23 | 1.87 | 5.59 | 3.06 × 10-5 | 2.97 × 10-5 |

| 6 | 41162891 | rs4711658 | TREML2 | G | 723 | 1.96 | 1.40 | 2.73 | 8.70 × 10-5 | 3.06 × 10-5 |

| 12 | 133434503 | rs4758911 | CHFR | C | 723 | 3.70 | 2.04 | 6.70 | 1.84 × 10-5 | 3.27 × 10-5 |

| 20 | 44765174 | rs6131021 | CD40;CDH22 | A | 723 | 92.48 | 33.78 | 252.90 | 9.05 × 10-18 | 3.42 × 10-5b |

| 7 | 24766507 | rs2721794 | DFNA5 | C | 723 | 3.43 | 2.13 | 5.51 | 4.89 × 10-7 | 4.34 × 10-5b |

| 10 | 50018765 | rs61742644 | WDFY4 | A | 723 | 3.55 | 2.32 | 5.44 | 8.93 × 10-9 | 4.66 × 10-5b |

| 9 | 34726821 | rs117956208 | FAM205A | C | 723 | 85.97 | 16.40 | 450.34 | 1.80 × 10-7 | 4.83 × 10-5b |

| 10 | 71590723 | rs11595284 | COL13A1 | G | 723 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.13 | 1.94 × 10-5 | 4.86 × 10-5 |

| 10 | 62362777 | rs9415604 | ANK3 | A | 723 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 1.70 × 10-6 | 5.09 × 10-5 |

| 21 | 23746907 | rs2263484 | LINC00308;MIR6130 | A | 580 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 1.38 × 10-4 | 5.40 × 10-5c |

| 11 | 637933 | rs72844728 | DRD4 | A | 723 | 2.94 | 1.74 | 4.97 | 6.10 × 10-5 | 5.99 × 10-5 |

| 5 | 71402339 | rs3806907 | MAP1B | G | 723 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 4.41 × 10-5 | 6.73 × 10-5 |

| 4 | 120156040 | rs13113112 | USP53 | A | 723 | 2.07 | 1.46 | 2.94 | 5.32 × 10-5 | 6.87 × 10-5 |

| 17 | 34262254 | rs17676662 | LYZL6 | G | 723 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.21 | 4.04 × 10-5 | 7.22 × 10-5 |

| 7 | 17186113 | rs7341411 | AGR3;AHR | G | 723 | 2.52 | 1.81 | 3.49 | 4.71 × 10-8 | 7.45 × 10-5** |

| 4 | 120563053 | rs7680914 | PDE5A;LINC01365 | G | 723 | 2.09 | 1.46 | 2.99 | 6.16 × 10-5 | 8.25 × 10-5 |

| 5 | 130407827 | rs7709727 | CHSY3;HINT1 | G | 723 | 1.94 | 1.51 | 2.51 | 4.50 × 10-7 | 8.42 × 10-5** |

| 6 | 152829175 | rs11155856 | SYNE1 | A | 723 | 3.07 | 2.11 | 4.48 | 8.21 × 10-9 | 8.46 × 10-5** |

| 16 | 30617688 | rs8044106 | ZNF689 | G | 580 | 2.41 | 1.90 | 3.07 | 2.46 × 10-12 | 8.55 × 10-5** |

| 8 | 136975349 | rs2317515 | KHDRBS3;LINC02055 | A | 723 | 0.30 | 0.17 | 0.55 | 1.02 × 10-4 | 8.90 × 10-5*** |

| 8 | 129280083 | rs17800434 | MIR1208;LINC00824 | T | 723 | 1.41 | 1.19 | 1.67 | 6.70 × 10-5 | 9.29 × 10-5 |

| 7 | 3109177 | rs12531570 | CARD11;LOC100129603 | A | 723 | 1.42 | 1.20 | 1.69 | 4.60 × 10-5 | 9.75 × 10-5 |

| 1 | 173377632 | rs6425229 | LOC100506023 | T | 723 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 9.54 × 10-5 | 9.97 × 10-5 |

GWAS, genome-wide association studies, CHR, chromosome; allele, effect allele; N, sample size, inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] subjects included in analysis; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

a10 M permutations unless otherwise noted.

b100 M permutations.

c1 M permutations.

We then integrated the lists of genes identified by both hypothesis-driven and hypothesis-free approaches and used CompBio to identify potential biological pathways underlying the genetic associations [Figure 3A]. We found that these genes were associated with innate immunity signalling [innate immunity, autophagosome, inflammasome complex formation, antigen processing and presentation], cytoskeletal reorganisation, Parkinsonism and neural development, mitochondria function, and aryl hydrocarbon [AhR] receptor signalling [Figure 3B].

3.5. Type I Paneth cell phenotype was associated with complications in ileal pouch

To examine the clinical relevance of Type I Paneth cell phenotype in UC subjects undergoing colectomy and IPAA, we investigated the association between Paneth cell phenotype and the development of postoperative ileal pouch complications. We first tested if abnormal Paneth cell phenotype would be associated with de novo CD in the pouch. A total of 125 subjects [27%] in our cohort developed de novo CD after total colectomy [Figure 1A and Table 1]. Subjects who developed de novo CD were younger at the time of surgery but did not have significant differences in other clinical metrics such as gender, disease duration, or smoking [Table 1]. We found that 35% [43/125] of the subjects who developed de novo CD had Type I Paneth cell phenotype at the time of colectomy, significantly higher than those who did not develop de novo CD [24%, 81/334; p = 0.034] [Figure 4A; and Supplementary Table 1]. Therefore, Paneth cell phenotype in uninflamed ileal resection margin at the time of colectomy is associated with future development of de novo CD.

Figure 4.

Type I Paneth cell phenotype was associated with higher risk in developing de novo CD and shorter time to first episode of pouchitis. [A] Subjects who developed de novo CD more commonly exhibited Type I Paneth cell phenotype [p = 0.034 by Fisher’s exact test]. [B] Both Paneth cell phenotype and age at surgery were significantly associated with the risk for de novo CD by multivariable logistic regression. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. [C] Receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curve of the model built with Paneth cell phenotype and age for predicting the development of de novo CD in ileal pouch. AUC: area under the ROC curve. [D] Among UC subjects who did not develop de novo CD, those with Type I Paneth cell phenotype [n = 63] showed shorter time to first episode of pouchitis compared with those with Type II Paneth cell phenotype [n = 213] [p = 0.02 by Kaplan–Meier analysis using log-rank test]. UC, ulcerative colitis; CD, Crohn’s disease.

We additionally performed univariate and multivariable logistic regression analysis to further investigate the associations between Paneth cell phenotype, demographics, or clinical parameters and the development of de novo CD [Table 4]. By univariate analysis, subjects with Type I Paneth cell phenotype at the time of surgery had a significantly increased risk for developing de novo CD (odds ratio [OR]: 1.64, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.05-2.56, p = 0.03) [Table 4]. In addition, there was an associated 1.7% decrease [OR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.97-1.0, p = 0.02] in the risk of developing de novo CD with 1-year increase in age [Table 4]. Although female subjects were more likely to have type I Paneth cell phenotype [Supplementary Table 1], we did not find an association between female gender and increased risk for developing de novo CD [p = 0.68] [Table 4]. We also did not find association between risk of developing de novo CD and smoking status, family history, or stage of surgery [p > 0.05 for all] [Table 4]. Multivariable analysis showed both Paneth cell phenotype and age at surgery remained significantly associated with the risk of de novo CD [Table 4 and Figure 4B]. Receiver operating characteristic [ROC] curve analysis of the model built with Paneth cell phenotype and age at surgery showed the area under the ROC curve [AUC] was 0.58 [95% CI: 0.53-0.65, p = 0.007 compared with chance] [Figure 4C].

Table 4.

Univariate and multivariable logistic regression for the development of de novo CD [N = 125].

| Univariate | Multivariable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | |

| Type I Paneth cell phenotype | 0.03 | 1.64 | 1.05-2.56 | 0.038 | 1.61 | 1.03-2.52 |

| Age at subtotal colectomy | 0.02 | 0.98 | 0.97-1.00 | 0.027 | 0.98 | 0.97-1.00 |

| Female gender | 0.68 | 0.92 | 0.61-1.38 | |||

| Family history of IBD | 0.49 | 1.18 | 0.74-1.86 | |||

| Dysplasia as indication of surgery | 0.76 | 1.11 | 0.56-2.21 | |||

| 2-stage of surgery | 0.19 | 0.55 | 0.22-1.39 | |||

| Smoking | ||||||

| Never smoker | Reference | 1 | ||||

| Former smoker | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.52-1.75 | |||

| Active smoker | 0.75 | 0.89 | 0.43-1.84 | |||

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CD, Crohn’s disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

We next investigated whether Paneth cell phenotype would be associated with other complications such as inflammation in the ileal pouch. The 334 subjects who did not develop de novo CD were analysed for associations with development of pouchitis [Figure 1A and Table 1]. Of note, the overall prevalence [29%] of pouchitis in this cohort [Table 1] was in keeping with what was reported in the literature.19 Subjects who developed pouchitis had significantly longer disease duration, more often had two-staged surgery, and were more often active smokers [p = 0.029, < 0.001, and 0.004, correspondingly] [Table 1]. Paneth cell phenotype was not associated with prevalence of pouchitis [Supplementary Table 1] but subjects with Type I Paneth cell phenotype at the time of surgery showed significantly shorter time to the first episode of pouchitis [p = 0.02] by univariate Cox regression analysis [Supplementary Table 4; and Figure 4D]. In multivariable Cox regression analysis, Type I Paneth cell phenotype was significantly associated with a shorter time to the first episode of pouchitis [hazard ratio: 1.73, 95% CI: 1.12-2.66, p = 0.01, Supplementary Table 4] after adjusting for age at colectomy, stage of surgery, and smoking. Therefore, Paneth cell phenotype correlates with time to first pouchitis episode.

4. Discussion

Previous studies from our group and others have shown that Type I Paneth cell phenotype is a predictive biomarker for more aggressive disease course in CD13–15 and is linked to the subjects’ genetic susceptibility and exposure to environmental risk factors.12–15 In this study we asked if Type I Paneth cell phenotype was also prevalent in UC, and if so, whether it could also predict complications in UC. We showed that the prevalence of Type I Paneth cell phenotype in UC was comparable to that of CD. We further identified common transcriptomic and genetic links of Type I Paneth cell phenotype across IBD. Finally, we showed that in UC subjects who received colectomy/IPAA, there was significant association with the development of de novo CD and time to first pouchitis episode.

Restorative proctocolectomy with IPAA is the preferred surgical procedure for subjects with UC who require a colectomy.1,19,20 Pouchitis is a common complication, whereas de novo CD is associated with significant morbidity.20,32 In this study, we collected subjects from three large IBD centres in the USA, and identified more than 450 study subjects over a span of 13 years with long-term clinical follow-up. We additionally collected genotyping data and qualified pathology material for transcriptomic and Paneth cell phenotype analyses. Our study represents one of the largest, retrospective, observational studies on pouch complications in UC [median number of subjects studied: 253, interquartile range: 561, n = 30 in meta-analysis by Heuthorst et al.33]. Our results demonstrated for the first time that ileal Paneth cell phenotype at the time of colectomy is a biomarker that correlates with the development of these complications.

It has been suggested that several clinical factors may predict the likelihood of pouchitis in UC/IPAA including paediatric onset,34 more severe disease activity at time of diagnosis, backwash ileitis, extraintestinal manifestations, appendiceal ulcerations, higher cumulative steroid dose,35–40 antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody [ANCA],41–43 and genetic polymorphisms in ATG16L1 and NOD2.44 Subjects included in this study all had preoperative diagnosis of UC without perianal fistula or fistulising disease. None of the samples possessed histological features of backwash ileitis. On the other hand, clinical factors that may predict de novo CD include younger age, previous smoking, female gender, preoperative diagnosis of indeterminate colitis, three-stage procedure, history of mouth ulceration, perianal fistula, colorectal stricture, and anal fissure.20,22,45,46 Our results also demonstrated that younger age at surgery correlated with increased risk of developing de novo CD, whereas female gender, stage of surgery, or smoking was not.

Major functions of Paneth cell are in host defence against pathogens and maintenance of small intestinal homeostasis through producing, packaging, and secreting antimicrobial peptides that regulate intestinal microbiome composition.8,10 Although our study, with its retrospective design, did not allow investigation of microbiota from the UC colectomy/IPAA cohort, recently several bacterial species have been shown to be differentially present in the faecal samples of UC subjects with pouchitis.47–49 Among these, the reductions of protective microbes Lachnospiraceae genera [Blautia]47,49 and Faecalibacterium48 and increased inflammatory microbes [eg, Fusobacteriaceae] are of particular interest, as these have been shown in our study to correlate with abnormal Paneth cell phenotype in CD.16 Likewise, reduction in Blautia was associated with the development of de novo CD.49 Previous studies additionally identified differences in transcriptomic signatures in areas of pouchitis vs no pouchitis.50–52 Taken together, these studies suggest a link between Paneth cell function and the development of pouchitis and de novo CD in UC subjects with IPAA. A separate study has shown that the UC pouch already displays transcriptomic changes before development of histological inflammation.52 Our data suggest the possibility that the ileal innate immunity landscape in UC subjects may modulate the susceptibility to further development of pouch inflammation and de novo CD. One clinical implication of this finding is that a pre-surgery ileal biopsy for Paneth cell phenotyping may be helpful in decision making for postoperative follow-up strategy. Future studies examining the temporal changes of Paneth cell phenotype in de novo CD subjects through follow-up studies and correlate with response to therapies would be of particular interest.

Our transcriptomic and genetic analyses incorporating both CD and UC subjects provided valuable insight into the pathogenesis of Paneth cell defects in IBD. Our results demonstrate associations in genes known to affect Paneth cell function and highlight novel candidate genes involved in Paneth cell biology. Across all analyses, associations with AGR3, MAP1B, and THEMIS are of particular interest. In mice, Agr3 expression is enriched at crypt base and associated with Lgr5 + intestinal stem cell signalling.53,54 MAP1B functions in microtubule assembly, and mutations are associated with intellectual disability, white matter deficit, and sensorineural hearing loss.55,56 MAP1B also plays a role in death-activated protein kinase-1 dependent autophagy and membrane blebbing.57 THEMIS is a T cell lineage-specific protein that mediates type 1 immune response in a context-dependent fashion58 and increases T cell receptor signalling in thymocyte selection stage by inhibiting the activity of tyrosine phosphatase SHP1.59 These data suggest potential cross-talk between Paneth cells and other cell types. Of note, a recent study has suggested a potential link between intraepithelial lymphocytes and Paneth cells.60 Future studies examining the causative relationship between these targets and Paneth cell function will be informative for understanding innate immunity regulation.

As Paneth cell function is regulated by both gene-environment interactions, we can now use this cellular biomarker to start identifying potential environmental factors that trigger Paneth cell dysfunction in UC, as we have shown in CD.15 Our study further illustrates the complementary values of biomarkers such as Paneth cell phenotype that can integrate gene-environment interactions with other omics read-outs. In addition, the study uses archived samples from routine pathology specimens, and therefore the transcriptomic data from bulk RNA-seq analysis provides a high-level view of potential molecular pathways associated with Paneth cell phenotype. Future prospective studies, including the sampling of mucosal microbiota and more in-depth analysis centred on Paneth cells themselves and other immune cell types by spatial transcriptomics, would be able to provide more granular details of the complex interactions between these different cell types and how the interactions shape Paneth cell function.

5. Conclusion

In summary, we show that ileal Paneth cell phenotype at the time of UC total colectomy correlates with future development of pouchitis and de novo CD. Together with previous studies on CD, these data suggest that abnormal Paneth cell phenotype is a cellular biomarker for aggressive disease course in IBD and is associated with underlying transcriptomic and genetic underpinning. Development of intervention strategies that target IBD subjects with Type I Paneth cell phenotype may provide better clinical management for these subjects.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Washington University Digestive Disease Research Core Center which is in part supported by grant P30 DK052574 from the NIH, and Genome Technology Access Center, and the Cedars-Sinai MIRIAD Biobank for assistance. The Cedars-Sinai MIRIAD IBD Biobank is supported by the F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute.

Contributor Information

Changqing Ma, Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Talin Haritunians, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Anas K Gremida, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Gaurav Syal, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Janaki Shah, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Shaohong Yang, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Claudia Ramos Del Aguila de Rivers, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Chad E Storer, Department of Genetics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Ling Chen, Division of Biostatistics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Emebet Mengesha, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Angela Mujukian, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Mary Hanna, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Phillip Fleshner, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

David G Binion, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Kelli L VanDussen, Department of Pediatrics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

Thaddeus S Stappenbeck, Department of Inflammation and Immunity, Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland, OH, USA.

Richard D Head, Department of Genetics, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Matthew A Ciorba, Department of Medicine, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Dermot P B McGovern, F. Widjaja Foundation Inflammatory Bowel Disease Institute, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Ta-Chiang Liu, Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, MO, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at the National Institute of Health [DK125296, DK124274, and DK136829 to TCL, DK062413 to DPBM, and P30DK052574], The Helmsley Charitable Trust [to DPBM], and a research grant from Pfizer [to TCL].

Conflict of Interest

TCL has research contracts from Interline Therapeutics and Denali Therapeutics. DPBM owns stock in Prometheus Biosciences. DPBM has consulted for Gilead, Pfizer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Qu Biologics, Bridge Biotherapeutics, Takeda, Palatin Technologies, and received grant support from Janssen. All other authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Author Contributions

CM, TH, MAC, DPBM, and TCL designed the study. CM, CRDAR, DGB, TH, EM, AKG, JS, KLV, TSS, and TCL collected data. TCL TH, EM, LC, CES, RDH, SY, GS, AM, MH, PF, and CM analysed the data. TCL TH, LC, CES, RDH, and CM wrote the manuscript. All the co-authors approved the manuscript.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. Bulk RNA-seq data were deposited in ArrayExpress [E-MTAB-12826].

References

- 1. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF.. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet 2017;389:1756–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mosli MH, Sandborn WJ, Kim RB, Khanna R, Al-Judaibi B, Feagan BG.. Toward a personalized medicine approach to the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:994–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaiko GE, Chen F, Lai CW, et al. Pai-1 augments mucosal damage in colitis. Sci Transl Med 2019;11:eaat0852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. West NR, Hegazy AN, Owens BMJ, et al. ; Oxford IBD Cohort Investigators. Oncostatin m drives intestinal inflammation and predicts response to tumor necrosis factor-neutralizing therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Med 2017;23:579–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, et al. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene ATG16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature 2008;456:259–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Liu TC, Gao F, McGovern DP, Stappenbeck TS.. Spatial and temporal stability of Paneth cell phenotypes in Crohn’s disease: implications for prognostic cellular biomarker development. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014;20:646–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ouellette AJ. Paneth cells and innate mucosal immunity. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010;26:547–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bevins CL, Salzman NH.. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2011;9:356–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Adolph TE, Tomczak MF, Niederreiter L, et al. Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature 2013;503:272–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Salzman NH, Hung K, Haribhai D, et al. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat Immunol 2010;11:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mastroianni JR, Ouellette AJ.. Alpha-defensins in enteric innate immunity: functional Paneth cell alpha-defensins in mouse colonic lumen. J Biol Chem 2009;284:27848–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cadwell K, Patel KK, Maloney NS, et al. Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn’s disease gene atg16l1 phenotypes in intestine. Cell 2010;141:1135–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. VanDussen KL, Liu TC, Li D, et al. Genetic variants synthesize to produce Paneth cell phenotypes that define subtypes of Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology 2014;146:200–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu TC, Naito T, Liu Z, et al. LRRK2 but not atg16l1 is associated with Paneth cell defect in japanese Crohn’s disease patients. JCI Insight 2017;2:e91917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu TC, Kern JT, VanDussen KL, et al. Interaction between smoking and ATG16l1t300a triggers Paneth cell defects in Crohn’s disease. J Clin Invest 2018;128:5110–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Liu TC, Gurram B, Baldridge MT, et al. Paneth cell defects in Crohn’s disease patients promote dysbiosis. JCI Insight 2016;1:e86907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jackson DN, Panopoulos M, Neumann WL, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction during loss of prohibitin 1 triggers Paneth cell defects and ileitis. Gut 2020;69:1928–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Khaloian S, Rath E, Hammoudi N, et al. Mitochondrial impairment drives intestinal stem cell transition into dysfunctional Paneth cells predicting Crohn’s disease recurrence. Gut 2020;69:1939–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lamb CA, Kennedy NA, Raine T, et al. ; IBD guidelines eDelphi consensus group. British society of gastroenterology consensus guidelines on the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults. Gut 2019;68:s1–s106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shen B, Kochhar GS, Kariv R, et al. Diagnosis and classification of ileal pouch disorders: consensus guidelines from the international ileal pouch consortium. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021;6:826–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Barnes EL, Kochar B, Jessup HR, Herfarth HH.. The incidence and definition of Crohn’s disease of the pouch: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2019;25:1474–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jackson KL, Stocchi L, Duraes L, Rencuzogullari A, Bennett AE, Remzi FH.. Long-term outcomes in indeterminate colitis patients undergoing ileal pouch-anal anastomosis: function, quality of life, and complications. J Gastrointest Surg 2017;21:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zaghiyan K, Kaminski JP, Barmparas G, Fleshner P.. De novo Crohn’s disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis and inflammatory bowel disease unclassified: long-term follow-up of a prospective inflammatory bowel disease registry. Am Surg 2016;82:977–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu TC, Kern JT, Jain U, et al. Western diet induces Paneth cell defects through microbiome alterations and farnesoid x receptor and type I interferon activation. Cell Host Microbe 2021;29:988–1001.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K.. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res 2009;19:1655–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Torres J, Mehandru S, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L.. Crohn’s disease. Lancet 2017;389:1741–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Piovani D, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Nikolopoulos GK, Lytras T, Bonovas S.. Environmental risk factors for inflammatory bowel diseases: an umbrella review of meta-analyses. Gastroenterology 2019;157:647–59.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vietri M, Radulovic M, Stenmark H.. The many functions of Escrts. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020;21:25–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yoon TY, Munson M.. Snare complex assembly and disassembly. Curr Biol 2018;28:R397–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Potdar AA, Li D, Haritunians T, et al. Ileal gene expression data from Crohn’s disease small bowel resections indicate distinct clinical subgroups. J Crohns Colitis 2019;13:1055–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ogura Y, Lala S, Xin W, et al. Expression of NOD2 in Paneth cells: a possible link to Crohn’s ileitis. Gut 2003;52:1591–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Shen B, Kochhar GS, Rubin DT, et al. Treatment of pouchitis, crohn’s disease, cuffitis, and other inflammatory disorders of the pouch: consensus guidelines from the international ileal pouch consortium. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022;7:69–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Heuthorst L, Wasmann K, Reijntjes MA, Hompes R, Buskens CJ, Bemelman WA.. Ileal pouch-anal anastomosis complications and pouch failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Open 2021;2:e074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rinawi F, Assa A, Eliakim R, et al. Predictors of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in pediatric-onset ulcerative colitis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;29:1079–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dharmaraj R, Dasgupta M, Simpson P, Noe J.. Predictors of pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2016;63:e58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fleshner P, Ippoliti A, Dubinsky M, et al. A prospective multivariate analysis of clinical factors associated with pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:952–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kalkan IH, Dagli U, Onder FO, et al. Evaluation of preoperative predictors of development of pouchitis after ileal-pouch-anastomosis in ulcerative colitis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol 2012;36:622–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lu H, Lian L, Navaneethan U, Shen B.. Clinical utility of c-reactive protein in patients with ileal pouch anal anastomosis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2010;16:1678–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Okita Y, Araki T, Tanaka K, et al. Predictive factors for development of chronic pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis in ulcerative colitis. Digestion 2013;88:101–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yantiss RK, Sapp HL, Farraye FA, et al. Histologic predictors of pouchitis in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol 2004;28:999–1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fleshner PR, Vasiliauskas EA, Kam LY, et al. High level perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody [panca] in ulcerative colitis patients before colectomy predicts the development of chronic pouchitis after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Gut 2001;49:671–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Singh S, Sharma PK, Loftus EV Jr, Pardi DS.. Meta-analysis: serological markers and the risk of acute and chronic pouchitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:867–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tyler AD, Milgrom R, Xu W, et al. Antimicrobial antibodies are associated with a Crohn’s disease-like phenotype after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:507–12.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tyler AD, Milgrom R, Stempak JM, et al. The nod2insc polymorphism is associated with worse outcome following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis. Gut 2013;62:1433–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Melton GB, Kiran RP, Fazio VW, et al. Do preoperative factors predict subsequent diagnosis of Crohn’s disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative or indeterminate colitis? Colorectal Dis 2010;12:1026–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fadel MG, Geropoulos G, Warren OJ, et al. Risks factors associated with the development of Crohn’s disease after ileal pouch-anal anastomosis for ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis 2023;17:1537–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Machiels K, Sabino J, Vandermosten L, et al. Specific members of the predominant gut microbiota predict pouchitis following colectomy and IPAA in UC. Gut 2017;66:79–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Reshef L, Kovacs A, Ofer A, et al. Pouch inflammation is associated with a decrease in specific bacterial taxa. Gastroenterology 2015;149:718–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tyler AD, Knox N, Kabakchiev B, et al. Characterization of the gut-associated microbiome in inflammatory pouch complications following ileal pouch-anal anastomosis. PLoS One 2013;8:e66934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ben-Shachar S, Yanai H, Baram L, et al. Gene expression profiles of ileal inflammatory bowel disease correlate with disease phenotype and advance understanding of its immunopathogenesis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2013;19:2509–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yanai H, Ben-Shachar S, Baram L, et al. Gene expression alterations in ulcerative colitis patients after restorative proctocolectomy extend to the small bowel proximal to the pouch. Gut 2015;64:756–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Huang Y, Dalal S, Antonopoulos D, et al. Early transcriptomic changes in the ileal pouch provide insight into the molecular pathogenesis of pouchitis and ulcerative colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2017;23:366–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kim TH, Saadatpour A, Guo G, et al. Single-cell transcript profiles reveal multilineage priming in early progenitors derived from LGR5[+] intestinal stem cells. Cell Rep 2016;16:2053–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Munoz J, Stange DE, Schepers AG, et al. The LGR5 intestinal stem cell signature: robust expression of proposed quiescent ‘+4’ cell markers. EMBO J 2012;31:3079–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cui L, Zheng J, Zhao Q, et al. Mutations of map1b encoding a microtubule-associated phosphoprotein cause sensorineural hearing loss. JCI Insight 2020;5:e136046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Walters GB, Gustafsson O, Sveinbjornsson G, et al. Map1b mutations cause intellectual disability and extensive white matter deficit. Nat Commun 2018;9:3456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Harrison B, Kraus M, Burch L, et al. Dapk-1 binding to a linear peptide motif in map1b stimulates autophagy and membrane blebbing. J Biol Chem 2008;283:9999–10014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang C, Blaize G, Marrocco R, et al. Themis enhances the magnitude of normal and neuroinflammatory type 1 immune responses by promoting TCR-independent signals. Sci Signal 2022;15:eabl5343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Choi S, Lee J, Hatzihristidis T, et al. Themis increases tcr signaling in CD4[+]CD8[+] thymocytes by inhibiting the activity of the tyrosine phosphatase SHP1. Sci Signal 2023;16:eade1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Matsuzawa-Ishimoto Y, Yao X, Koide A, et al. The gammadelta iel effector API5 masks genetic susceptibility to Paneth cell death. Nature 2022;610:547–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author. Bulk RNA-seq data were deposited in ArrayExpress [E-MTAB-12826].