Abstract

Aim

To identify factors associated with resilience in family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia based on Luthar and Cicchetti's definition of resilience.

Design

Integrative review of resilience in family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia reported by studies with quantitative and qualitative research designs.

Data Sources

Databases used for the literature search included CINAHL, PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Google Scholar.

Review Methods

A total of 565 potentially relevant studies published between January 1985 and March 2024 were screened, and 27 articles met the inclusion criteria.

Results

Family caregivers were most commonly adult children of care recipients, female and providing care in their home. Two themes emerged from the review: factors associated with adversity (dementia severity, caregiver role strain, stigma, family stress, female gender, low income and low education) and factors associated with positive adaptational outcomes (positive aspect of caregiving, social support and religiosity/spirituality).

Conclusion

In our review of Asian research, four new factors—caregiver role strain, stigma, family stress and positive aspects of caregiving—emerged alongside those previously identified in Western studies. A paradigm shift was observed from a focus on factors associated with adversity to factors associated with positive adaptational outcomes, particularly after the issuance of the WHO's 2017 global action plan for dementia. However, a gap remains between WHO policy recommendations and actual research, with studies often neglecting to address gender and socioeconomic factors.

Impact

The review findings will broaden healthcare providers' understanding of resilience in dementia caregivers and use them to develop comprehensive programmes aimed at reducing factors associated with adversity and enhancing those associated with positive adaptational outcomes. This approach can be customized to incorporate Asian cultural values, empowering caregivers to navigate challenges more effectively.

No Patient or Public Contribution

This paper is an integrative review and does not include patient or public contributions.

Keywords: Asia, dementia, family caregivers, integrative review, resilience

1. INTRODUCTION

Dementia is a syndrome resulting from various diseases that progressively damage nerve cells and impair brain function, often leading to cognitive decline beyond what is considered typical for aging (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). The prevalence of dementia is increasing. Alzheimer's Disease International (ADI), 2021 reported that in 2020, more than 55 million people around the world were living with dementia. Furthermore, the number of people with dementia is expected to nearly double every 20 years, reaching 78 million in 2030. The fastest growth in dementia prevalence is seen in China, India and other countries of South Asia (ADI, 2021).

Dementia involves serious impairments in cognition, memory, thinking and judgement resulting in the inability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) without assistance (WHO, 2023). As dementia progresses, debilitating behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia such as agitation, aggression, depression and apathy also emerge (Budson & Solomon, 2021). Older adults with dementia require caregiver support in many ways (Mograbi et al., 2018), and providing this support can take a toll on the caregivers themselves. It is imperative to understand the caregiving needs of those who care for older people with dementia as well as how dementia caregivers can successfully adapt to their caregiving roles (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2021).

Informal caregivers, who provide unpaid care to recipients, are more common than paid formal caregivers (Boccardi & Mecocci, 2017). Informal caregivers usually live with the people with dementia and may be family members such as spouses, children or siblings (Boccardi & Mecocci, 2017). Family caregivers are required to spend much of their time—at least 40 h per week—in caregiving for older adults with dementia; considerably more caregiving time than is needed for an older people without dementia (Kim et al., 2018).

The work of caregiving requires much time and is often stressful, placing the caregiver at risk both physically and psychologically. Caregiving tasks can adversely affect the well‐being of caregivers, particularly those who are unable to adapt to stressful situations (Farina et al., 2017). However, some dementia caregivers encounter fewer negative consequences of caregiving than others and may even experience positive outcomes (Henry et al., 2018). In the United States, caregivers often form positive emotional bonds with care recipients that include expressions of love, appreciation, gratitude and shared emotions along with moments of familiarity (Sideman et al., 2023).

Caregivers who experience positive outcomes from caregiving are necessarily adaptable in overcoming caregiving challenges and thus show resilience (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000). Although the existing literature extensively explores various factors associated with resilience in caregivers, including those caring for individuals with dementia (Manzini et al., 2016; Palacio et al., 2020; Teahan et al., 2018), no review studies have specifically focused on delineating factors related to resilience in family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia. Therefore, further examination of the research to date is needed to advance our understanding of resilience in this population.

1.1. Background

We are using the definition of resilience offered by Luthar and Cicchetti (2000), who described resilience as ‘a dynamic process wherein individuals display positive adaptation despite experiences of significant adversity or trauma’ (p.2). This concept does not represent a personality trait or attribute of the individual (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000; Masten et al., 1999; Rutter, 1985). Rather, it is a two‐dimensional construct that implies exposure to adversity and manifestation of positive adaptational outcomes (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000). First, adversity typically encompasses adverse life circumstances that are known to be statistically associated with adjustment difficulties. In dementia caregiving, adversity refers to the burden that caregivers face when providing care for people with dementia (Duangjina et al., 2023; Poe et al., 2023). Even though caregiver burden can be perceived as either an adversity or an outcome of resilience, depending on the context, it may initially be seen as an adversity because it represents the challenges, stress and strain experienced by individuals who provide care to others (Duangjina et al., 2023; Poe et al., 2023).

Positive adaptation, the second construct, is typically defined as behaviorally manifested social competence, appropriate emotional or behavioural adjustment or success in achieving favourable outcomes (Luthar & Cicchetti, 2000). It involves not only surviving but also thriving in the face of adversity. Resilient individuals, as observed by Luthar and Cicchetti (2000), often experience fewer negative health outcomes and more positive ones compared to those who experience lower levels of resilience. In the context of dementia caregiving, positive adaptational outcomes can be understood as effective coping, adaptability, reduced mental disorders, decreased psychological health issues, improved overall well‐being or components of well‐being, and improved quality of life (Duangjina et al., 2023; Kobiske & Bekhet, 2018; Poe et al., 2023).

Windle and Bennett (2012) suggested that a person's resilience depends on the assets and resources accessible to them, given their individual coping style and sociocultural context. Asian countries are experiencing the most rapid growth in dementia (ADI, 2021). People in different Asian countries share somewhat similar cultural values based on familism, filial piety and collectivism. Familism is broadly defined as a strong identification with and attachment to nuclear and extended families (Schwartz et al., 2010). It consists of components, including (a) a sense of obligation to family, (b) regarding family as a first source of emotional support, (c) valuing interconnectedness among family members, (d) taking family into account when making important decisions, (e) managing behaviour to maintain family honour, and (f) willingly subordinating individual preferences for the benefit of the family (Campos et al., 2014).

Filial piety is another cultural value based on the moral obligation that children owe their parents and represents the practice of respecting and caring for one's parents in old age. In Asian cultures, most family caregivers are adult children, and their cultural and religious values shape their commitment to fulfilling their caregiving roles (Chan, 2010). Even though those religions have their own unique tenets, they all emphasize the importance of caring for parents to satisfy motivations related to reciprocity and filial piety (Tanggok, 2017).

In addition, Asian cultures are primarily collectivistic, emphasizing group identity over individual autonomy (Anngela‐Cole & Hilton, 2009; Pharr et al., 2014). Behaviour is viewed as a reflection of one's internal self and representation of the family and community. Individuals often face commentary from family and community members, leading to social comparisons for conformity (Anngela‐Cole & Hilton, 2009). Deviating from norms may result in personal disappointment, disapproval, shame and exclusion (Anngela‐Cole & Hilton, 2009).

Cultural values based on familism, filial piety and collectivism may affect the resilience of family caregivers in the Asian context. However, few literature reviews have addressed the resilience of family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia. One recent systematic review conducted by Teahan and colleagues in 2018 addressed global research on resilience and caregiving and included studies performed in some Asian countries. Their review included studies published from January 2006 to March 2016 and is now somewhat dated, especially since the WHO launched its global action plan for a public health response to dementia in 2017. One aim of the WHO action plan is to strengthen research and innovation regarding dementia caregivers (World Health Organization, 2017), and thus, a large number of new studies have recently emerged. Therefore, this integrative review advances the work performed by Teahan et al. (2018) by examining more recent research.

2. THE REVIEW

2.1. Aims

This integrative review aimed to delineate factors associated with resilience in family caregivers of older Asian adults with dementia. An additional goal was to identify research gaps in Asian countries.

2.2. Design

This review of published literature related to resilience in family caregivers of Asian older adults with dementia was guided by the integrative review methodology of Whittemore and Knafl (2005). This approach permitted inclusion of studies using a variety of research designs, including experimental, non‐experimental and qualitative studies, to more fully understand resilience in the population of interest. Using Whittemore and Knafl's (2005) method, the five following stages were followed: (1) problem identification, (2) data search, (3) data evaluation, (4) data analysis and (5) presentation. No a priori protocol for this review was registered in PROSPERO or any other registry, as protocol registration is typically not required for integrative reviews.

2.3. Search methods

2.3.1. Problem identification

We used the SPIDER tool to formulate a research question. SPIDER is an acronym composed of five components: (a) sample, (b) phenomenon of interest, (c) design, (d) evaluation and (e) research type (LoBiondo‐Wood et al., 2018). Our review focused on resilience of family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia.

2.3.2. Data sources

Four databases—CINAHL, PubMed, EMBASE and PsycINFO—were searched by the first author for original research published between January 1985 and March 2024. Moreover, to ensure a comprehensive review, Google Scholar and citation searches were performed to identify additional relevant studies. The publication timeframe was selected because the first known application of the concept of resilience was in research conducted by Rutter in 1985. Although Teahan et al. (2018) previous review addressed global studies in the topic area, it included research performed in only a few Asian countries and was limited to articles published through 31 March 2016. Since that time, however, many new studies have emerged due to the WHO's issuance of its global action plan for dementia (World Health Organization, 2017). Thus, an up‐to‐date review is needed of factors associated with resilience of family caregivers of older Asian people with dementia.

This integrative review builds on the knowledge shared in a 2022 conference abstract prepared by Duangjina and Gruss (2022), for which the search dates were limited to 2016 through 2021. To enrich our analysis with a broader historical perspective predating the WHO's 2017 global action plan for dementia, we here include 10 additional studies published from 1985 through 2015. Furthermore, we include two additional studies published in 2022. This approach not only provides valuable insights into earlier points of view on resilience but also better reflects trends in dementia caregiving research.

2.3.3. Search strategy

Our initial search strategy involved mapping medical subject heading (MeSh) terms related to the review focus. Search terms were selected so as to focus the search on resilience; family caregivers of older people with dementia; and the countries of the Middle East and Central, South and East Asia, as these regions share similar cultural values of filial piety. Examples of the search terms used are ‘Dementia’, ‘Alzheimer's disease’, ‘family caregivers’, ‘familial’ and ‘adult children’. Search details are presented in Table S1. The search was facilitated by consultation with a reference librarian specializing in the health sciences. Records were downloaded into EndNote 20, which is reference manager and Covidence, which is a systematic review software for screening against inclusion and exclusion criteria.

2.3.4. Study selection

Following the PRISMA guideline (Page et al., 2021), the first author began by searching four databases. All identified articles were exported into EndNote 20, and duplicates were electronically deleted. The first author then screened the articles' abstracts and titles based on the review's eligibility criteria. Next, first and second authors independently reviewed the full texts. The authors showed 93.75% agreement were resolved between the authors to achieve 100% consensus.

2.4. Study eligibility

To be eligible for inclusion in this review, studies had to be published in an English‐language, peer‐reviewed journal between January 1985 and March 2024. In addition, each study had to (1) be conducted with informal (unpaid) Asian family caregivers of older adults (at least 60 years of age) with dementia; (2) address factors associated with adversity or caregiver burden; (3) address factors associated with positive adaptational outcomes (reduced severity or incidence of mental disorders, decreased psychological health problems, enhanced well‐being or components of well‐being and improved quality of life); (4) be conducted in either a healthcare or community setting; (5) employ either a quantitative (descriptive, correlational, quasi‐experimental or experimental) or qualitative (phenomenological, ethnographic, grounded theory, historical, case study or action) research design. We excluded sources if they were (1) not peer‐reviewed, such as dissertations; (2) study protocols; (3) conference abstracts; (4) reviews of literature; or (5) expert opinions.

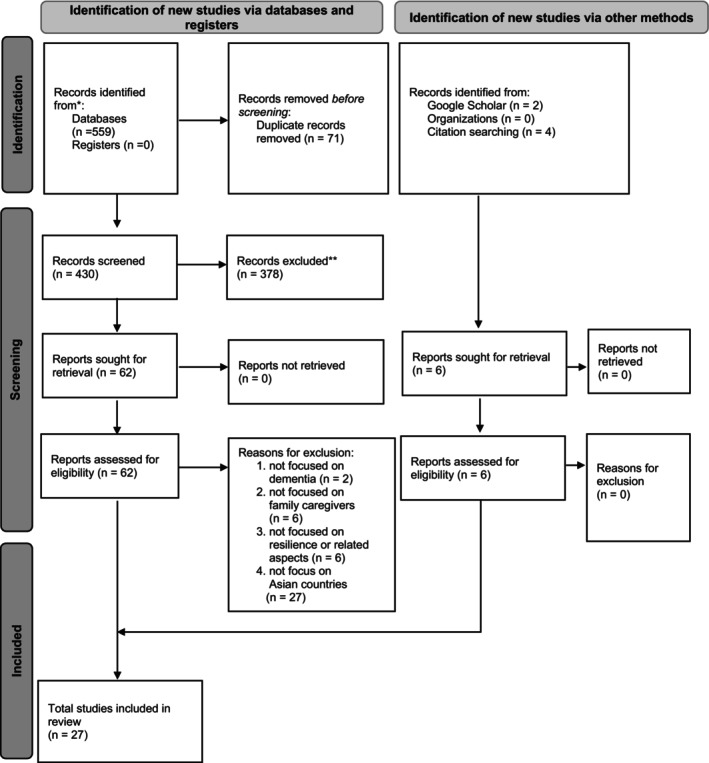

2.5. Search outcome

After a comprehensive search, 565 potentially relevant studies were identified: 559 studies from the four databases, two from Google Scholar and four studies from citation searching. After title and abstract screening, full texts of 69 articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. A total of 41 studies were excluded because they were not focused on dementia (n = 2), not focused on family caregivers (n = 6), not focused on resilience or related factors (n = 6) and/or not conducted in Asian countries (n = 27). Finally, 27 unique studies were included in this review. The study selection process is detailed in the PRISMA diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram for selection of review articles.

2.6. Quality appraisal

The team used tools developed by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) for Quality appraisal, including risk of bias, in the quantitative studies. The NIH tool was used for observational, cohort and cross‐sectional studies. The NHLBI tool (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [NHLBI], 2014) was used for quality appraisal of the controlled trials. These tools each provide a quality rating based on 14 items, where a score of 0–4 points signify poor, 5–9 points signify fair and 10–14 points signify good quality (NHLBI, 2014). To appraise the qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme was used (Singh, 2013). This tool provides a quality rating based on 10 items, where a score of 0–4 indicates that a study is not valuable and a score of 5–10 indicates that it is valuable (Singh, 2013). For each study, risk of bias was assessed by the first author and then confirmed by the second author based on tool guidelines. The authors showed 95% agreement on risk of bias assessment, so further discussions were conducted to resolve disagreements and achieve 100% consensus.

2.7. Data abstraction and synthesis

Data were analysed using thematic analysis (Lucas et al., 2007). Thematic analysis was selected as the most appropriate method for integrating study results because it allows the researcher to draw conclusions from heterogeneous studies. In the four‐step thematic synthesis process recommended by Lucas et al. (2007), the initial two steps involve the extraction of study data and coding. After the 25 articles were read several times by the first author to gain an overall understanding of the data, the first author extracted data using Garrard's matrix method (Garrard, 2017). The extracted data are presented in Table S2. Extracted data were coded and summarizes in themes and subthemes. The matrix provides information about the studies' authors and publication dates, countries, designs, family caregiver characteristics, types and severity of dementia and themes. In the third and fourth steps of the process, themes emerging from each study were identified and then synthesized into final themes. This was an iterative process performed in consultation with the co‐authors and involved continual engagement with the data as themes were formulated.

According to Luthar and Cicchetti (2000), and as mentioned previously, resilience is defined as a dynamic process characterized by positive adaptation in the face of significant adversity. This concept encompasses two key components: adversity and positive adaptational outcomes. Based on this conceptual framework, the final themes identified in our review were categorized into factors associated with adversity and factors associated with positive adaptational outcomes. More specifically, factors were classified as ‘factors associated with adversity’ if they pertained to caregiver burden. Conversely, factors were categorized as ‘factors associated with positive adaptational outcomes’ if they were significantly related to effective coping, adaptability, reduced mental disorders, decreased psychological health problems, enhanced positive emotional outcomes, improved well‐being or better quality of life (Duangjina et al., 2023; Kobiske & Bekhet, 2018; Poe et al., 2023). On the whole, factors were derived from quantitative data and were further explored and explained using qualitative data.

We synthesized study findings but did not perform a meta‐analysis because this review integrated diverse quantitative and qualitative studies, and it was not possible to use statistical methods to summarize the results. Consequently, quantitative synthesis was limited to descriptive statistics (means) for data collected using a single instrument. In studies reporting eligible quantitative data, we extracted data on statistical associations between factors and caregiver burden and between factors and positive adaptational outcomes. The extracted data are presented in Table S2. The results of final analyses—for example, final models in regression analyses—were used when available. In addition, the effects of potential confounders, such as sociodemographic factors, were considered simultaneously with the study results.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study characteristics

A total of 27 empirical studies conducted in 11 Asian countries were reviewed. The studies are summarized by country in Table 1. In addition, of the 27 studies, seven employed qualitative descriptive designs (Ali & Bokharey, 2015; Ar & Karanci, 2019; Bai et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2016; Netto et al., 2009; Sun, 2014; Yuan et al., 2023) and the remaining 20 used quantitative methods.

TABLE 1.

Summary of the studies by countries.

| Countries in which studies were conducted | Number of studies | References |

|---|---|---|

| China | 7 | Cheng et al., 2016; Sun, 2014; Tang et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2019; Xue et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Yu et al., 2016 |

| South Korea | 5 | Jeong et al., 2020; Han et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2018 |

| Singapore | 4 | Netto et al., 2009; Vaingankar et al., 2016; Tay et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2023 |

| Thailand | 3 | Ondee et al., 2013; Pankong et al., 2018; Pothiban et al., 2020 |

| Taiwan | 3 | Bai et al., 2024; Huang et al., 2006; Su & Chang, 2020 |

| Turkey | 1 | Ar & Karanci, 2019 |

| Pakistan | 1 | Ali & Bokharey, 2015 |

| Iran | 1 | Saffari et al., 2018 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 | Khusaifan & El Keshky, 2017 |

| India | 1 | Pandya, 2019 |

3.2. Participant characteristics

The family caregivers in the 27 studies totalled 7251 patients, with sample sizes ranging from 8 to 1425. Caregiver age estimates averaged 54.73 years old and ranged from 20 to 96 years old. The caregivers spent averages of 3.12 years and 9.50 h per day providing care. Most caregivers had at least high school‐level education. In addition, most caregivers were adult children of care recipients, female and provided care at home. In 11 studies, most caregivers had a religion/belief system, including Christianity, Confucianism, Buddhism, Hinduism or Islam; 16 studies did not report religions/belief systems. Among eight studies reporting income information, seven reported monthly income ranging from USD 0 (living on savings) to 12,000 and one reported that 86.7% of family caregivers had ‘adequate’ income (Kim et al., 2009); most studies did not report caregiver or household income values. Across the 27 studies, the most common type of dementia in care recipients was Alzheimer's disease, and in most recipients, dementia severity was moderate or advanced.

3.3. Quality assessment

The risk of bias was low in, 10 (50%) of the 20 quantitative studies, and were considered to be of good quality (scoring 10 or 11 of 14). 10 (50%) were of fair quality (scoring 8 or 9 of 14). The seven qualitative studies were assigned scores ranging from 8 to 10 of 10, indicating that they were of value. Supplementary Tables 3, 4 and 5 provide summaries of the quality appraisals for qualitative studies, observational cohort and cross‐sectional studies and intervention studies, respectively (Table S3).

3.4. Factors associated with resilience of family caregivers

In total, 10 factors were identified in the literature. These factors were organized into two overarching themes consistent with the dual constructs of resilience outlined by Luthar and Cicchetti (2000): factors associated with adversity and factors associated with positive adaptational outcomes.

3.4.1. Factors associated with adversity

In the context of dementia caregiving, the adversity faced by caregivers is regarded as caregiver burden (Duangjina et al., 2023; Poe et al., 2023). Factors associated with adversity are thus considered to be factors pertaining to caregiver burden. We identified seven factors associated with adversity, including (1) dementia severity, (2) caregiver role strain, (3) stigma, (4) family stress, (5) female gender, (6) low income and (7) low education.

Dementia severity

Six studies reported a correlation between dementia severity and caregiver burden (Kim et al., 2009; Ondee et al., 2013; Saffari et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2013; Vaingankar et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016). Dementia severity was measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating score (Tang et al., 2013) and in terms of deficiencies in activities of daily living (ADL) and the severity of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Among the studies, two found that lower levels of basic ADL were associated with higher caregiver burden (Kim et al., 2009; Ondee et al., 2013), while the other two reported that lower levels of instrumental ADL were related to increased caregiver burden (Kim et al., 2009; Saffari et al., 2018). Additionally, three studies identified a correlation between more severe behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia and higher caregiver burden (Ondee et al., 2013; Vaingankar et al., 2016; Yu et al., 2016).

Caregiver role strain

Three qualitative studies reported that caregiver role strain might be related to caregiver burden in dementia caregivers (Ar & Karanci, 2019;Cheng et al., 2016; Sun, 2014). In two of these studies, self‐imposed pressure that caregivers experienced might have been related to caregiver burden, as they held rigid expectations for their own caregiving as children of care recipients (Cheng et al., 2016; Sun, 2014). In all three studies, caregivers experienced additional burden due to excessive self‐sacrificing tendencies (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Cheng et al., 2016; Sun, 2014). In addition, one study reported that some caregivers felt anxious and guilty when they left their parents to spend time on recreational activities because of their moral sense of family responsibility (Ar & Karanci, 2019).

Findings of two qualitative studies revealed that changes in the caregiver‐recipient relationship might be related to caregiver burden (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Cheng et al., 2016). Most caregivers felt sadness as they experienced loss of the parent–child relationship with their care recipients; in particular, they felt the loss of the parental support they had received as children (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Cheng et al., 2016). Also, some caregivers reported role‐reversals, feelings of grief and pain when their care recipients' behaviours changed, and they acted ‘like a child’. (Ar & Karanci, 2019). Some caregivers felt hopeless and lonely because they could not have a meaningful conversation with their parents (Cheng et al., 2016).

Stigma

Five studies reported that stigma was related to caregiver burden, poor psychological health or diminished coping among family caregivers, as the caregivers had experienced self‐stigma and shame associated with care recipients' dementia symptoms (Cheng et al., 2016; Jeong et al., 2020; Saffari et al., 2018; Su & Chang, 2020; Sun, 2014). In one study, family caregivers reported discrimination and stigma towards older family members with dementia; the caregivers would not disclose the illness to neighbours or strangers in order to avoid prejudice, and they believed that when dementia people faced discrimination, dementia became a societal sickness (Sun, 2014). In three other studies, researchers found that affiliate stigma, or caregiver internalization of stigma associated with dementia, was positively associated with caregiver burden (Su & Chang, 2020) and decreased caregiver psychological health (Jeong et al., 2020; Saffari et al., 2018). In Su and Chang's (2020) study, compared to female caregivers, male caregivers showed higher levels of anxiety and heavier care burdens derived from a higher level of affiliate stigma. Additionally, Jeong et al. (2020) and Saffari et al. (2018) observed that caregivers with high affiliate stigma may not have been able to cope well with stressful caregiving situations and may have had negative psychological outcomes.

Family stress

Five studies reported that stress within the family might be associated with caregiver burden and with lower adaptability in family caregivers (Ali & Bokharey, 2015; Ar & Karanci, 2019; Cheng et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2018; Sun, 2014). A quantitative study conducted in South Korea revealed a correlation between elevated levels of family stress and decreased adaptability in caregivers of individuals with dementia (Kim et al., 2018). Also, in three of four qualitative studies, researchers found that family problems constituted a stressor within the family of people with dementia (Ali & Bokharey, 2015; Ar & Karanci, 2019; Sun, 2014). In addition, in three of the qualitative studies, family‐related stressors related to marital conflict, nuclear family problems, familial violence, discord with adult children and divorce (Ar & Karanci, 2019) as well as negotiating caregiving responsibilities and disagreeing over arrangements (Cheng et al., 2016; Sun, 2014). Cheng et al. (2016) reported that caregivers were sometimes so concerned about maintaining family harmony that they opted to perform all caregiving responsibilities so as not to burden their family members (Cheng et al., 2016).

Qualitative findings from two studies revealed that family caregivers expressed sadness and guilt in blaming themselves for lack of family harmony or for a failing marriage that ostensibly impacted their parents (Ali & Bokharey, 2015; Ar & Karanci, 2019). In one of these studies, caregivers believed they had not been good children because their failures had caused their parents to develop dementia (Ar & Karanci, 2019). Also in that study, some female caregivers of older adults experienced conflicts with husbands who were resentful about their wives' caregiving responsibilities, which consumed time and energy (Ar & Karanci, 2019). In addition, some caregivers in that study complained of mental exhaustion due to fear and anxiety regarding care recipients' safety, which could be jeopardized by domestic abuse from other family members (Ar & Karanci, 2019).

Female gender

In eight studies, researchers found that female caregivers perceived more caregiver burden and/or depression than male caregivers (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Han et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2006; Khusaifan & El Keshky, 2017; Kim et al., 2009; Tang et al., 2013; Yoon et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2016). Of those, four studies reported that female caregivers showed higher caregiver burden levels than male caregivers (Han et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2009; Yoon et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2016). Also, one study reported that the proportion of female caregivers with mild to severe caregiver burden levels was higher than that among male caregivers (Tang et al., 2013). In one qualitative study, many female caregivers reported experiencing fatigue due to their multiple responsibilities, such as caring for other elders, their children and their husbands (Ar & Karanci, 2019). Two of eight studies reported that female caregivers experienced significantly more severe depression than male caregivers (Han et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2006) while in a third study, female caregivers showed higher depression levels than male caregivers, but the difference was not significant (Khusaifan & El Keshky, 2017).

Low income

Four studies revealed that income was related to caregiver burden or health outcomes of family caregivers (Huang et al., 2006; Kim et al., 2009; Sun, 2014; Tay et al., 2016). Low income significantly increased caregiver burden (Kim et al., 2009) and depression (Huang et al., 2006). Tay et al. (2016) found that household income significantly influenced the environment domain of health‐related quality of life among family caregivers. Kim et al. (2009) also found that subjective sense of socioeconomic status (as good/fair/poor) was a stronger predictor of caregiver outcomes than actual income. Furthermore, in their qualitative study, Sun (2014) identified many sources of dementia‐related financial burden for family caregivers, including transportation to hospitals, medical examinations, prescription drugs (especially those imported from other countries), hospital bills, personal caretakers and domestic help and nursing home care.

Low education

Three quantitative studies explored the effect of education on caregiver burden among dementia caregivers (Kim et al., 2009;Yang et al., 2019; Yoon et al., 2018). In two of these studies, researchers found that family caregivers with less education experienced higher levels of caregiver burden (Yang et al., 2019; Yoon et al., 2018). Similarly, a third study reported that caregiver education of less than 6 years was associated with greater caregiver burden (Kim et al., 2009).

3.4.2. Factors associated with positive adaptational outcomes

Positive adaptational outcomes of dementia caregivers can be measured as effective coping, adaptability, reduced mental disorders, decreased psychological health problems, improved overall well‐being or components of well‐being (e.g. emotional well‐being, psychological well‐being), and improved quality of life (Duangjina et al., 2023; Kobiske & Bekhet, 2018; Poe et al., 2023). We identified three factors associated with such adaptational outcomes: (1) positive aspects of caregiving, (2) social support and (3) religiosity/spirituality.

Positive aspects of caregiving

Eight studies examined the relationship between positive aspects of caregiving (PAC) and increased resilience, positive emotional outcomes and improved psychological well‐being (Bai et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2016; Netto et al., 2009; Pankong et al., 2018; Pothiban et al., 2020; Xue et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2023). Two quantitative studies examined PAC using the Positive Aspects of Caregiving Questionnaire (PACQ) (mean score = 33.44, range = 9–45) (Pankong et al., 2018; Xue et al., 2018). Among the eight studies, PAC was found to potentially decrease caregiver burden (Xue et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2019), enhance positive appraisals of the caregiving experience (Cheng et al., 2016; Pankong et al., 2018), and improve psychological well‐being (Pankong et al., 2018). Furthermore, dementia caregivers perceived that maintaining a positive outlook towards dementia caregiving enabled them to derive satisfaction from their roles, experience happiness, become more aware of the importance of self‐care and develop a positive attitude towards care recipients (Yuan et al., 2023). Additionally, embracing PAC enabled caregivers to cultivate patience, deepen their understanding of dementia and caregiving, experience personal growth and develop resilience (Cheng et al., 2016; Netto et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2023).

Among the studies, two found that the intimacy and special bond between caregivers and care recipients potentially enhanced the psychological well‐being of caregivers (Cheng et al., 2016; Pothiban et al., 2020). As reported in four qualitative studies, caregivers often found that spending time caring for individuals with dementia was heart‐warming and fulfilling, leading to improved relationships with the care recipients (Bai et al., 2024; Cheng et al., 2016; Netto et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2023). Regardless of the challenges involved, some caregivers viewed dementia caregiving as a validation of their love for the care recipient (Cheng et al., 2016; Netto et al., 2009), and among children caring for their parents, it also served as a means of fulfilling their filial obligations (Cheng et al., 2016; Netto et al., 2009; Yuan et al., 2023). These positive relationships between caregivers and care recipients sustained caregivers' motivation and enriched their dementia caregiving (Bai et al., 2024).

Social support

In eight studies, dementia caregivers reported experiencing benefits from social support during their caregiving experiences in terms of effective coping, improved adaptability, improved life satisfaction, decreased depression and improved quality of life (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Han et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2006; Khusaifan & El Keshky, 2017; Kim et al., 2018; Pothiban et al., 2020; Sun, 2014; Wang et al., 2019). Researchers variously reported that a certain level of overall social support could alleviate the negative effect of depression on caregivers' life satisfaction (Khusaifan & El Keshky, 2017), had a positive indirect effect on family adaptation to caregiving and a positive direct effect on caregiver resilience (Kim et al., 2018), and showed a positive correlation with all aspects of caregivers' quality of life (Pothiban et al., 2020). Moreover, a study in Korea revealed that social interaction and affectionate support decreased caregiver depression, but that only tangible support decreased caregiver burden (Han et al., 2014). In four studies examining specific forms of social support, informal social support was found to be a major resource for family caregivers, especially support from family (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Khusaifan & El Keshky, 2017; Sun, 2014; Wang et al., 2019). Two quantitative studies reported that family support had positive effects on family caregivers. In one of these studies, social support from family and friends was positively correlated with caregivers' life satisfaction (Khusaifan & El Keshky, 2017); in the other, support from close family members was the strongest influencing factor for adaptation among family caregivers, followed by support from kin (extended family) (Wang et al., 2019).

In addition to family support, social support from care recipients themselves (Cheng et al., 2016), neighbours or the community (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Wang et al., 2019), paid in‐home caregiving assistants (Huang et al., 2006), healthcare providers (Ar & Karanci, 2019) and the government (Sun, 2014) was found to benefit family caregivers in both qualitative and quantitative research. In one qualitative study, although care recipients may not have been able to engage in meaningful conversations, caregivers—particularly spouses—often found the recipients to be valuable companions, confidantes and even sources of practical support despite their cognitive decline (Cheng et al., 2016). In a cross‐sectional study, researchers found that support from the community positively influenced family caregiver adaptation (Wang et al., 2019). In another qualitative study, family caregivers reported receiving caregiving assistance from neighbours or service providers and feeling warm and grateful as a result, especially when the assistance was unexpected (Ar & Karanci, 2019). In a quantitative study, family caregivers employing paid in‐home assistants showed better coping and general perceptions of their health than caregivers lacking such assistance (Huang et al., 2006). Finally, findings from a qualitative study revealed that government welfare assistance agencies played a positive role in the ability of family caregivers to cope with dementia‐related financial burdens (Sun, 2014).

Religiosity/spirituality

Six studies revealed that religiosity or spirituality was associated with decreased caregiver burden, decreased depressive symptoms, effective coping and improved resilience (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Netto et al., 2009; Pandya, 2019; Saffari et al., 2018; Sun, 2014; Yoon et al., 2018). Religious activity and intrinsic religiosity among caregivers decreased subjective burden (Yoon et al., 2018) and alleviated depressive symptoms (Saffari et al., 2018; Yoon et al., 2018). The effects of religiosity on burden and depressive symptoms differed by religious group (Yoon et al., 2018). Buddhist family caregivers experienced growth in their religious beliefs to the point where they attained greater compassion; they believed that they had transcended caring for their mother solely due to filial duty and had begun caring for her just because she was a human being (Netto et al., 2009). In addition, one study's implementation of a meditation programme improved resilience among Buddhist and Hindu caregivers; in a 5‐year follow‐up, female, spouse and Hindu caregivers continued to attend at least 75% of meditation lessons, and home meditation was the strongest predictor of the post‐test resilience score (Pandya, 2019).

Spirituality was also explored in two qualitative studies (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Sun, 2014). In one of these studies, family caregivers stated they believed that religious/fatalistic coping was the best way to manage stress related to dementia caregiving (Sun, 2014). In both studies, some caregivers believed that God had sent the disease to test them and to challenge them to fulfil their caregiving obligations; they accepted this situation as God‐given (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Sun, 2014). This faith in God helped them to accept the reality of the disease and the caregiving responsibilities that came with it (Ar & Karanci, 2019; Sun, 2014). Due to their religious beliefs, caregivers stated that they were not inclined to experience strong negative feelings towards their parent care recipients (Ar & Karanci, 2019).

4. DISCUSSION

This integrative review examined the literature on factors associated with resilience in Asian family caregivers of older adults with dementia. Resilience, as defined by Luthar and Cicchetti (2000), is characterized by a dynamic process in which individuals demonstrate positive adaptation despite experiencing significant adversity. Guided by this definition, our review revealed seven factors associated with adversity in the form of caregiver burden, (1) dementia severity, (2) caregiver role stain, (3) stigma, (4) family stress, (5) female gender, (6) low income and (7) low education, and three factors associated with positive adaptational outcomes, (1) PAC, (2) social support and (3) religiosity/spirituality. We conclude that when caregivers confront caregiver burden, they are presented with opportunities to strengthen their resilience. This adversity may prompt them to seek social support, adopt positive reframing strategies and employ religious or spiritual coping strategies. Caregivers who, despite these challenges, achieve positive outcomes such as reduced mental health disorders and improved well‐being are considered to be resilient.

Compared to the previous systematic review of resilience in family caregivers of people with dementia, most studies (80.77%) considered by Teahan et al. (2018) were conducted in the United States and other Western countries, while we included only studies conducted in Asian countries. Like Teahan and colleagues, we observed that dementia severity, female gender, low income and low education were all associated with resilience. Beyond these findings, we show that these factors are associated with adversity, which plays a crucial role in the process of developing resilience.

4.1. Dementia severity

In Asian dementia caregivers, adversity is viewed as a caregiver burden, which is contextual and associated with dementia severity. The dementia severity is presented in the forms of decreased ADL, and some case presents more severe behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. This raises the possibility that caregiver burden worsens with the progression of dementia because care recipients need more caregiving. A systematic review regarding caregiver burden among informal caregivers of people with dementia affirmed our hypothesis that when care recipients have a lower level of functional status, a higher prevalence of behavioural disturbances, and a higher level of neuropsychiatric symptoms, a higher level of caregiver burden is the result (Chiao et al., 2015).

4.2. Female gender

Compared to male caregivers, we discovered that female caregivers experienced more caregiver burden. Our findings are consistent with Teahan et al.' (2018) report of strong evidence of poorer caregiver outcomes among female caregivers, including caregiver burden and depressive symptoms. Another study by Mulud and McCarthy (2017), who examined family caregivers of people with mental illness, also supported our finding that family caregiver gender was associated with caregiver burden.

4.3. Low income and low education

Our review indicated that family caregivers with low income were likely to experience high levels of caregiver burden in various studies. Similarly, Teahan et al. (2018) previous systematic review reported that poor economic status potentially led to depressive symptoms and other adverse caregiver outcomes (reduced physical health and lack of access to support). Concerning caregiver education, we found that family caregivers with less education appeared to experience a high caregiver burden. However, Teahan et al. (2018) concluded that the relationship between education and resilience was unclear. Some studies reported a higher level of education yielded less burden and depression for the caregiver, but a few studies reported that higher education yielded higher depression and lower resilience (Teahan et al., 2018).

As in our study, Teahan et al. (2018) found that social support and religiosity/spirituality were positively associated with resilience. Our findings reveal that those factors may play a role in the process of developing resilience due to their associations with positive adaptational outcomes.

4.4. Social support

Informal social support, particularly when received from family members, was a strong predictor of adaptation among family caregivers in Asian countries. These findings may be explained by the strong intimacy and attachments typically found within Asian families as Asian countries share somewhat similar cultural values based on familism (Knight et al., 2002). The previous systematic review by Teahan et al. (2018) indicated that beyond family, friends were a significant source of social support for family caregivers. In addition, they found that formal support from healthcare services was related with lower caregiver burden, lower depression and higher resilience (Teahan et al., 2018). The benefits of formal support were emphasized in Teahan and colleagues' study, but we found that informal support from family was particularly beneficial in our review.

4.5. Religiosity and spirituality

Similar to our findings, Teahan et al. (2018) observed that religiosity/spirituality had a positive impact on caregiver outcomes. Specifically, they found that religiosity/spirituality increased positive attitudes towards caregiving and personal growth. We found that religiosity and spirituality decreased burden and depressive symptoms in caregivers. These findings were affirmed in a recent systematic review, which reported that religiosity/spirituality likely fostered resilience in persons with or without traumatic events (Schwalm et al., 2022).

Furthermore, we identified four factors related to resilience—caregiver role strain, stigma, family stress and positive aspects of caregiving (PAC)—that were not identified as such by Teahan and colleagues.

4.6. Caregiver role strain

We discovered that caregiver burden was influenced by caregiver role strain. Such strain occurs when caregivers experience stress and anxiety because they feel incapable of fulfilling their caregiving responsibilities to the best of their ability. Asian dementia caregivers often impose pressure on themselves regarding their caregiving performance, particularly adult child caregivers. In addition, Asian dementia caregivers often have many other roles in their work and family lives. When these roles are in conflict with their caregiving roles, they feel unable to perform as well as they wish in any role. A systematic review involving family caregivers of older adults with chronic illness supported our finding that caregiver role strain potentially contributes to caregiver burden (Isac et al., 2021).

4.7. Stigma

Our review revealed that Asian caregivers internalized feelings of stigma associated with dementia (affiliate stigma) and also faced social discrimination. Our finding is consistent with a conducted study by Schomerus et al. (2012), who found that family caregivers faced social stigma due to the psychiatric symptoms presented by people with mental disorder. One explanation for this finding is the presentation of neuropsychiatric symptoms in older people with dementia that kindle stigma in others (Li et al., 2014). Additionally, we discovered that caregiver burden favourably correlated with affiliate stigma. Similarly, a systematic review examining family caregivers of older people with mental illness performed by Shi et al. (2019) reported that affiliate stigma was positively correlated with caregiver burden.

4.8. Family stress

In our review, Asian family caregivers faced family conflict, especially the one related to dementia caregiving. Family stress negatively affected adaptation within the families of older people with dementia. Similarly, one qualitative study by O'Dwyer et al. (2013) reported that Australian caregivers of people with dementia who experienced family conflict appeared to be the least resilient. In addition, when Cassé et al. (2018) examined the associations between family conflict and components of resilience (self‐efficacy and self‐control) among high‐risk mothers, they found a negative association between family conflict and self‐efficacy among mothers with low self‐control.

4.9. Positive aspect of caregiving (PAC)

In our review, Asian family caregivers demonstrated a high level of PAC as assessed with the PACQ. Furthermore, our findings suggest that PAC among Asian family caregivers may play a role in decreasing adversity or caregiver burden, promoting resilience, enhancing positive emotional outcomes—specifically gratitude and expression of filial piety—and improving psychological well‐being. These conclusions are supported by a study conducted by Wong et al. (2019), who found that PAC buffered the effects of caregiving burden on depression, anxiety and overall psychological distress in family caregivers of frail older people.

When we compared studies published before and after WHO launched its global action plan for a public health response to dementia in 2017, we observed an attempt to shift the research paradigm to factors potentially enhancing resilience. Before WHO launched the global action plan, most studies focused on factors associated with adversity or caregiver burden, but after 2017, most studies emphasized factors related to positive adaptational outcomes. In addition, WHO's 2017 action plan aimed to implement public health responses to dementia by supporting gender, financial and educational equity in dementia caregiving. However, since the action plan was launched, few studies have focused on these factors' relationship to resilience in family caregivers of older people with dementia. Rather, the studies identifying female gender, low income and low education as associated with resilience mostly emerged before 2017.

5. STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

Among this review's strengths, the 27 included studies reflected diverse research methodologies, and our database search was conducted to maximize the review's scope. Previous reviews have limited their scope, for example, by excluding experimental studies (Teahan et al., 2018). Additionally, although previous reviews have included some Asian studies, our exclusive focus on Asian caregivers fully explores the Asian caregiving context, and, thus, our review offers a deeper understanding of Asian family caregiving. We compared key findings of published studies before and after WHO issued its 2017 global action plan for a public health response to dementia. While helping to fill the knowledge gap regarding dementia caregiving, our findings also revealed a gap between WHO policy and recent studies' inattention to gender‐related and socioeconomic factors impacting resilience.

As to our study's limitations, most quantitative studies included in our review were correlational studies, which are limited in their ability to establish causality among the results. In addition, we included only English‐language studies in our review, and thus potentially relevant studies published in Asian languages were not reviewed. Finally, in our exclusion of grey literature, we may have overlooked useful unpublished studies.

6. IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE, FUTURE RESEARCH AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

This review reveals two overarching factors associated with resilience: adversity and positive adaptational outcomes. We also found that the interventions conducted in Asian countries reported better resilience‐related outcomes when the interventions were provided in the home. Thus, nurses and other healthcare providers should consider providing interventions to family caregivers in the home setting. In addition, given the importance of religiosity/spirituality as a factor associated with positive adaptational outcomes, healthcare providers should familiarize themselves with the core tenets of Asian religions and belief systems so that they can provide culturally responsive care and tailor healthcare practices to accommodate them.

We show that several interrelated factors are associated with the resilience process among Asian dementia caregivers. In planning future interventional research for this population, healthcare providers should prioritize strategies aimed at both reducing factors associated with adversity or caregiver burden and maximizing factors that potentially contribute to positive adaptational outcomes. Moreover, it is essential to incorporate socio‐cultural values such as filial piety, collectivism, and familism into intervention designs to enhance their cultural relevance and effectiveness for Asian dementia caregivers. Additionally, in future studies, researchers should consider examining resilience as a personal attribute that enables individuals to overcome adversity, thus providing a more comprehensive understanding of resilience in this population. Furthermore, given the recommendations of WHO's 2017 global action plan, additional research is needed to investigate the relationships between resilience and both gender and SES among family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia.

Regarding dementia‐related policy, Asian countries should develop strategies for supporting dementia caregivers that are tailored to their particular religion and economic status. Moreover, public education policies should be devised to enhance dementia literacy by addressing social misconceptions about the disease; this approach may ultimately alleviate the affiliate stigma experienced by dementia caregivers.

7. CONCLUSION

In this review, we adopted Luthar and Cicchetti (2000) definition of resilience as the framework. This framework defines resilience as a dynamic process involving positive adaptation in the face of significant adversity. Our analysis of 27 studies identified seven factors associated with adversity and three factors related to positive adaptational outcomes. In the context of dementia caregiving, adversity is often viewed as a caregiver burden. At the same time, positive adaptational outcomes manifest as effective coping, adaptability, reduced severity or incidence of mental disorders, decreased psychological health problems, enhanced well‐being or components of well‐being and improved quality of life. Family caregivers who experience positive adaptational outcomes could be deemed resilient. Future intervention research should prioritize mitigating factors related to adversity while promoting those potentially contributing to positive adaptational outcomes. A gap persists between WHO policy recommendations and actual research on resilience in family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia, particularly concerning gender‐related and socioeconomic factors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.D., V.G., P.H., C.F. Made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. T.D. P.H. C.F. Involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content. T.D., V.G., P.H., C.F. Given final approval of the version to be published. Each author should have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content. T.D., C.F. Agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not‐for‐profit sector. However, the first author received an academic scholarship for her PhD programme from Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer‐review/10.1111/jan.16272.

Supporting information

Table S1.

Table S2.

Table S3.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors wish to acknowledge the editorial contributions of Mr. Jon Mann and Mr. Kevin Grandfield, University of Illinois Chicago, during this manuscript's development.

Duangjina, T. , Hershberger, P. E. , Gruss, V. , & Fritschi, C. (2025). Resilience in family caregivers of Asian older people with dementia: An integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 81, 156–170. 10.1111/jan.16272

Contributor Information

Thitinan Duangjina, Email: tduang2@uic.edu, Email: thitinan.d@cmu.ac.th.

Patricia E. Hershberger, Email: phersh@umich.edu

Valerie Gruss, Email: vgruss@uic.edu.

Cynthia Fritschi, Email: fritschi@uic.edu.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.

REFERENCES

- Ali, S. , & Bokharey, I. Z. (2015). Maladaptive cognitions and physical health of the caregivers of dementia: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well‐Being, 10(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer's Disease International . (2021). Dementia statistic . https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia‐facts‐figures/dementia‐statistics/

- Anngela‐Cole, L. , & Hilton, J. M. (2009). The role of attitudes and culture in family caregiving for older adults. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 28(2–3), 59–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ar, Y. , & Karanci, A. N. (2019). Turkish adult children as caregivers of parents with Alzheimer's disease: Perceptions and caregiving experiences. Dementia (London), 18(3), 882–902. 10.1177/1471301217693400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai, Y. L. , Shyu, Y. I. L. , Huang, H. L. , Chiu, Y. C. , & Hsu, W. C. (2024). The enrichment process for family caregivers of persons living with dementia: A grounded theory approach. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 80(1), 252–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boccardi, V. , & Mecocci, P. (2017). The aging caregiver in the aged world of dementia. Journal of Systems and Integrative Neuroscience, 3(5), 1–2. 10.15761/JSIN.1000177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Budson, A. E. , & Solomon, P. R. (2021). Memory loss, Alzheimer's disease, and dementia‐e‐book: A practical guide for clinicians. Elsevier Health Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- Campos, B. , Ullman, J. B. , Aguilera, A. , & Dunkel Schetter, C. (2014). Familism and psychological health: The intervening role of closeness and social support. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20(2), 191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassé, J. F. , Finkenauer, C. , Oosterman, M. , van der Geest, V. R. , & Schuengel, C. (2018). Family conflict and resilience in parenting self‐efficacy among high‐risk mothers. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(6), 1008–1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, S. W. C. (2010). Family caregiving in dementia: The Asian perspective of a global problem. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 30(6), 469–478. 10.1159/000322086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S. T. , Mak, E. P. , Lau, R. W. , Ng, N. S. , & Lam, L. C. (2016). Voices of Alzheimer caregivers on positive aspects of caregiving. Gerontologist, 56(3), 451–460. 10.1093/geront/gnu118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiao, C. Y. , Wu, H. S. , & Hsiao, C. Y. (2015). Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. International Nursing Review, 62(3), 340–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duangjina, T. , Fink, A. M. , & Gruss, V. (2023). Resilience in family caregivers of Asian older adults with dementia: A concept analysis. Advances in Nursing Science, 46(4), 145–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duangjina, T. , & Gruss, V. (2022). Resilience in family caregivers of Asian older adults with dementia: An integrative review. Innovation in Aging, 6(Suppl 1), 229. [Google Scholar]

- Farina, N. , Page, T. E. , Daley, S. , Brown, A. , Bowling, A. , Basset, T. , Livingston, G. , Knapp, M. , Murray, J. , & Banerjee, S. (2017). Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 13(5), 572–581. 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrard, J. (2017). Health sciences literature review made easy: The matrix method. Jones & Bartlett Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J. W. , Jeong, H. , Park, J. Y. , Kim, T. H. , Lee, D. Y. , Lee, D. W. , Ryu, S. H. , Kim, S. K. , Yoon, J. C. , Jhoo, J. , Kim, J. L. , Lee, S. B. , Lee, J. J. , Kwak, K. P. , Kim, B. J. , Park, J. H. , & Kim, K. W. (2014). Effects of social supports on burden in caregivers of people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(10), 1639–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, C. S. , Hubbard, R. L. , Struckmeyer, K. M. , & Spencer, T. A. (2018). Family resilience and caregiving. In Bailey W. A. & Harrist A. W. (Eds.), Family Caregiving: Fostering resilience across the life course (pp. 1–26). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. Y. , Musil, C. M. , Zauszniewski, J. A. , & Wykle, M. L. (2006). Effects of social support and coping of family caregivers of older adults with dementia in Taiwan. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 63(1), 1–25. 10.2190/72JU-ABQA-6L6F-G98Q [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isac, C. , Lee, P. , & Arulappan, J. (2021). Older adults with chronic illness–caregiver burden in the Asian context: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 104(12), 2912–2921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, J. S. , Kim, S. Y. , & Kim, J. N. (2020). Ashamed caregivers: Self‐stigma, information, and coping among dementia patient families. Journal of Health Communication, 25(11), 870–878. 10.1080/10810730.2020.1846641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khusaifan, S. J. , & El Keshky, M. E. (2017). Social support as a mediator variable of the relationship between depression and life satisfaction in a sample of Saudi caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(2), 239–248. 10.1017/S1041610216001824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, G. M. , Lim, J. Y. , Kim, E. J. , & Kim, S. S. (2018). A model of adaptation for families of elderly patients with dementia: Focusing on family resilience. Aging & Mental Health, 22(10), 1295–1303. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1354972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M. D. , Hong, S. C. , Lee, C. I. , Kim, S. Y. , Kang, I. O. , & Lee, S. Y. (2009). Caregiver burden among caregivers of Koreans with dementia. Gerontology, 55(1), 106–113. 10.1159/000176300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight, B. G. , Robinson, G. S. , Flynn Longmire, C. V. , Chun, M. , Nakao, K. , & Kim, J. H. (2002). Cross cultural issues in caregiving for persons with dementia: Do familism values reduce burden and distress? Ageing International, 27(1), 70–94. [Google Scholar]

- Kobiske, K. R. , & Bekhet, A. K. (2018). Resilience in caregivers of partners with young onset dementia: A concept analysis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(5), 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. L. , Hu, N. , Tan, M. S. , Yu, J. T. , & Tan, L. (2014). Behavioral and psychological symptoms in Alzheimer's disease. BioMed Research International, 2014(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LoBiondo‐Wood, G. , Haber, J. , Cameron, C. , & Singh, M. D. (2018). Nursing research in Canada. Methods, critical appraisal, and utilization. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, P. J. , Baird, J. , Arai, L. , Law, C. , & Roberts, H. M. (2007). Worked examples of alternative methods for the synthesis of qualitative and quantitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7(1), 1–7. 10.1186/1471-2288-7-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar, S. S. , & Cicchetti, D. (2000). The construct of resilience: Implications for interventions and social policies. Development and Psychopathology, 12(4), 857–885. 10.1017/s0954579400004156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzini, C. S. S. , Brigola, A. G. , Pavarini, S. C. I. , & Vale, F. A. C. (2016). Factors associated with the resilience of family caregivers of persons with dementia: A systematic review. Revista Brasileira de Geriatria e Gerontologia, 19, 703–714. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A. S. , Hubbard, J. J. , Gest, S. D. , Tellegen, A. , Garmezy, N. , & Ramirez, M. (1999). Competence in the context of adversity: Pathways to resilience and maladaptation from childhood to late adolescence. Development and Psychopathology, 11(1), 143–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mograbi, D. C. , Morris, R. G. , Fichman, H. C. , Faria, C. A. , Sanchez, M. A. , Ribeiro, P. C. , & Lourenço, R. A. (2018). The impact of dementia, depression and awareness on activities of daily living in a sample from a middle‐income country. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(6), 807–813. 10.1002/gps.4765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulud, Z. A. , & McCarthy, G. (2017). Caregiver burden among caregivers of individuals with severe mental illness: Testing the moderation and mediation models of resilience. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 31(1), 24–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute . (2014). Study quality assessment tools . https://www. nhlbi. nih. gov/health‐topics/study‐quality‐assessment‐tools

- Netto, N. R. , Jenny, G. Y. N. , & Philip, Y. L. K. (2009). Growing and gaining through caring for a loved one with dementia. Dementia, 8(2), 245–261. 10.1177/147130120910 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dwyer, S. , Moyle, W. , & van Wyk, S. (2013). Suicidal ideation and resilience in family carers of people with dementia: A pilot qualitative study. Aging & Mental Health, 17(6), 753–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ondee, P. , Panitrat, R. , Pongthavornkamol, K. , Senanarong, V. , Harvath, T. A. , & Nittayasudhi, D. (2013). Factors predicting depression among caregivers of persons with dementia. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 17(2), 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 88(2021), 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Palacio G, C., Krikorian, A. , Gómez‐Romero, M. J. , & Limonero, J. T . (2020). Resilience in caregivers: A systematic review. American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Medicine, 37(8), 648–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya, S. P. (2019). Meditation program enhances self‐efficacy and resilience of home‐based caregivers of older adults with Alzheimer's: A five‐year follow‐up study in two South Asian cities. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 62(6), 663–681. 10.1080/01634372.2019.1642278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pankong, O. , Pothiban, L. , Sucamvang, K. , & Khampolsiri, T. (2018). A randomized controlled trial of enhancing positive aspects of caregiving in Thai dementia caregivers for dementia. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 22(2), 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Pharr, J. R. , Dodge Francis, C. , Terry, C. , & Clark, M. C. (2014). Culture, caregiving, and health: Exploring the influence of culture on family caregiver experiences. ISRN Public Health, 2014(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Poe, A. A. , Vance, D. E. , Patrician, P. A. , Dick, T. K. , & Puga, F. (2023). Resilience in the context of dementia family caregiver mental health: A concept analysis. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 45(1), 143–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothiban, L. , Srirat, C. , Wongpakaran, N. , & Pankong, O. (2020). Quality of life and the associated factors among family caregivers of older people with dementia in Thailand. Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(4), 913–920. 10.1111/nhs.12746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter, M. (1985). Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorder. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 147(6), 598–611. 10.1192/bjp.147.6.598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saffari, M. , Koenig, H. G. , O'Garo, K. N. , & Pakpour, A. H. (2018). Mediating effect of spiritual coping strategies and family stigma stress on caregiving burden and mental health in caregivers of persons with dementia. Dementia, 1–18. 10.1177/1471301218798082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schomerus, G. , Schwahn, C. , Holzinger, A. , Corrigan, P. W. , Grabe, H. J. , Carta, M. G. , & Angermeyer, M. C. (2012). Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 125(6), 440–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwalm, F. D. , Zandavalli, R. B. , de Castro Filho, E. D. , & Lucchetti, G. (2022). Is there a relationship between spirituality/religiosity and resilience? A systematic review and meta‐analysis of observational studies. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(5), 1218–1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. J. , Weisskirch, R. S. , Hurley, E. A. , Zamboanga, B. L. , Park, I. J. , Kim, S. Y. , Umaña‐Taylor, A. , Castillo, L. G. , Brown, E. , & Greene, A. D. (2010). Communalism, familism, and filial piety: Are they birds of a collectivist feather? Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16(4), 548–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y. , Shao, Y. , Li, H. , Wang, S. , Ying, J. , Zhang, M. , Li, Y. , Xing, Z. , & Sun, J. (2019). Correlates of affiliate stigma among family caregivers of people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 26(1), 49–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sideman, A. B. , Merrilees, J. , Dulaney, S. , Kiekhofer, R. , Braley, T. , Lee, K. , Chiong, W. , Miller, B. , Bonasera, S. J. , & Possin, K. L. (2023). “Out of the clear blue sky she tells me she loves me”: Connection experiences between caregivers and people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 71(7), 2172–2183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J. (2013). Critical appraisal skills programme. Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics, 4(1), 76–77. 10.4103/0976-500X.107697 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.‐A. , & Chang, C.‐C. (2020). Association between family caregiver burden and affiliate stigma in the families of people with dementia. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 1–10. 10.3390/ijerph17082772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, F. (2014). Caregiving stress and coping: A thematic analysis of Chinese family caregivers of persons with dementia. Dementia, 13(6), 803–818. 10.1177/1471301213485593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang, B. , Harary, E. , Kurzman, R. , Mould‐Quevedo, J. F. , Pan, S. , Yang, J. , & Qiao, J. (2013). Clinical characterization and the caregiver burden of dementia in China. Value in Health Regional Issues, 2(1), 118–126. 10.1016/j.vhri.2013.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanggok, M. (2017). Filial piety in Islam and Confucianism: A comparative study between Ahadith and the Analects. Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities, 137(1), 95–109. 10.2991/icqhs-17.2018.15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tay, K. C. P. , Seow, C. C. D. , Xiao, C. , Lee, H. M. J. , Chiu, H. F. , & Chan, S. W. C. (2016). Structured interviews examining the burden, coping, self‐efficacy, and quality of life among family caregivers of persons with dementia in Singapore. Dementia, 15(2), 204–220. 10.1177/1471301214522047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teahan, Á. , Lafferty, A. , McAuliffe, E. , Phelan, A. , O'Sullivan, L. , O'Shea, D. , & Fealy, G. (2018). Resilience in family caregiving for people with dementia: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(12), 1582–1595. 10.1002/gps.4972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaingankar, J. A. , Chong, S. A. , Abdin, E. , Picco, L. , Jeyagurunathan, A. , Zhang, Y. , … Subramaniam, M. (2016). Care participation and burden among informal caregivers of older adults with care needs and associations with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(2), 221–231. 10.1017/S104161021500160X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q. , Sheng, Y. , Wu, F. , Zhang, Y. , & Xu, X. (2019). Effect of different sources support on adaptation in families of patient with moderate‐to‐severe dementia in China. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 34(6), 361–375. 10.1177/1533317519855154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore, R. , & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle, G. , & Bennett, K. M. (2012). Caring relationships: How to promote resilience in challenging times. In Ungar M. (Ed.), The social ecology of resilience: A handbook of theory and practice (pp. 219–231). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, D. F. K. , Ng, T. K. , & Zhuang, X. Y. (2019). Caregiving burden and psychological distress in Chinese spousal caregivers: Gender difference in the moderating role of positive aspects of caregiving. Aging & Mental Health, 23(8), 976–983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2017). The global action plan for the public health response to dementia in 2017‐2025. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/global‐action‐plan‐on‐the‐public‐health‐response‐to‐dementia‐2017‐‐‐2025

- World Health Organization . (2023). Dementia. https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/dementia

- Xue, H. , Zhai, J. , He, R. , Zhou, L. , Liang, R. , & Yu, H. (2018). Moderating role of positive aspects of caregiving in the relationship between depression in persons with Alzheimer's disease and caregiver burden. Psychiatry Research, 261, 400–405. 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.12.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, F. , Ran, M. , & Luo, W. (2019). Depression of persons with dementia and family caregiver burden: Finding positives in caregiving as a moderator. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 19(5), 414–418. 10.1111/ggi.13632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, K. H. , Moon, Y. S. , Lee, Y. , Choi, S. H. , Moon, S. Y. , Seo, S. W. , Park, K. W. , Ku, B. D. , Han, H. J. , Park, K. H. , Han, S. H. , Kim, E. J. , Lee, J. H. , Park, S. A. , Shim, Y. S. , Kim, J. H. , Hong, C. H. , Na, D. L. , … CARE (Caregivers of Alzheimer's Disease Research) Investigators . (2018). The moderating effect of religiosity on caregiving burden and depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 22(1), 141–147. 10.1080/13607863.2016.1232366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu, H. , Wu, L. , Chen, S. , Wu, Q. , Yang, Y. , & Edwards, H. (2016). Caregiving burden and gain among adult‐child caregivers caring for parents with dementia in China: The partial mediating role of reciprocal filial piety. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(11), 1845–1855. 10.1017/S1041610216000685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Q. , Zhang, Y. , Samari, E. , Jeyagurunathan, A. , Goveas, R. , Ng, L. L. , & Subramaniam, M. (2023). Positive aspects of caregiving among informal caregivers of persons with dementia in the Asian context: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.

Table S2.

Table S3.

Data Availability Statement

The data that supports the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article.