Abstract

Early, mild and young COPD concepts are not clearly defined and are often used interchangeably to refer to the onset of the disease. Objective: To describe and compare the characteristics of mild, young and early COPD in a large sample of COPD from primary and secondary care. Methods: Pooled analysis of individual data from four multicenter observational studies of patients with stable COPD (≥40 years, FEV1/FVC < 0.7, smoking ≥ 10 pack-years). Mild COPD was defined as FEV1% ≥ 65%; young COPD as <55 years; and early COPD as <55 years and smoking ≤ 20 pack-years. The relationship between FEV1(%), age and pack-years was analyzed with linear regression equations. Results: We included 5468 patients. Their mean age was 67 (SD: 9.6) years, and 85% were male. A total of 1158 (21.2%) patients had mild COPD; 636 (11.6%) had young COPD and 191 (3.5%) early COPD. The three groups shared common characteristics: they were more frequently female, younger and with less tobacco exposure compared with the remaining patients. Early COPD had fewer comorbidities and fewer COPD admissions, but no significant differences were found in ambulatory exacerbations. In linear regression analysis, the decline in FEV1(%) was more pronounced for the first 20 pack-years for all age groups and was even more important in younger patients. Conclusions: Mild, young and early COPD patients were more frequently women. The steepest decline in FEV1(%) was observed in individuals <55 years and smoking between 10 and 20 pack-years (early COPD), which highlights the importance of an early detection and implementation of preventive and therapeutic measures.

Keywords: COPD, young, early, mild, prognosis

1. Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a highly prevalent disease and one of the leading causes of death [1]. Epidemiological studies have estimated a prevalence of COPD of 11.8% in adults in Spain [2] and 13% worldwide [3], with a high rate of underdiagnosis, especially in women and younger adults [4]. The natural history of COPD is not yet fully understood and can be very variable; although smoking is still a major culprit [5], other genetic, environmental and developmental factors may exert their effects during the growing years by reducing the maximally attained forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) or accelerating FEV1 decline in adult life or both, thus increasing the risk of COPD [6].

The identification of young individuals at risk of developing COPD or at early stages of the disease could help to implement smoking cessation strategies and tackle symptom and exacerbation management and, hence, improve prognosis [7,8,9].

The concept of early disease is generally used to refer to disease of recent onset; however, in COPD, this concept is usually reserved for individuals who present with the disease at a young age irrespective of the time elapsed since the initiation of symptoms [10,11,12,13,14,15]. On the other hand, mild COPD is defined by a relatively preserved FEV1, irrespective of the age of the patient. As a consequence, the terms of mild and early COPD are sometimes confused with COPD in young subjects, or “young COPD” [16,17].

During the last years, operational definitions of early COPD have been proposed [18,19] that usually include young age (relative to the middle age of patients with COPD), airflow limitation and a significant smoking burden. In fact, the main difference between these proposed definitions of early COPD and the definition of COPD in general is the age range, but they do not take into account the time elapsed since the beginning of symptoms or the initiation of the causative exposure, which is predominantly smoking in most developed countries.

The objective of the present study was to describe and compare the characteristics of mild, young and early COPD on a large sample of Spanish COPD patients from primary and secondary care.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design of the Study

This was a pooled analysis of individual-level data from 4 multicenter, cross-sectional, observational studies [19,20,21,22]. In summary, all studies included COPD patients recruited while in a stable state in both primary care and pneumology outpatient clinics. All individuals were ≥40 years old, smokers or former smokers of at least 10 pack-years with a spirometrically confirmed diagnosis of COPD defined by a post-bronchodilator [FEV1]/forced vital capacity [FVC] ≤ 0.7 and FEV1(%) of 80% or less.

2.2. Variables

Sociodemographic, clinical and functional data, as well as the number of exacerbations and hospital admissions due to COPD in the previous year, were collected. Dyspnea was assessed using the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnea scale [23], which is a questionnaire that consists of five statements about perceived breathlessness: grade 1, “I only get breathless with strenuous exercise”; grade 2, “I get short of breath when hurrying on the level or up a slight hill”; grade 3, “I walk slower than people of the same age on the level because of breathlessness or have to stop for breath when walking at my own pace on the level”; grade 4, “I stop for breath after walking 100 yards or after a few minutes on the level”; and grade 5, “I am too breathless to leave the house”. The impact of the disease was assessed using the COPD assessment test (CAT) [24], which is a validated, short, self-administered questionnaire that measures the impact of the disease in patients with 8 questions; the score ranges from 0 to 40, with 40 being the worst possible health state and 0 the best. The BODEx (body mass index, airway obstruction, dyspnea and exacerbations) index was also included [25]; this is a severity score with prognostic value for exacerbations and mortality, with a score range from 0 to 9 units, with 9 being the worst prognosis. Self-reported comorbid conditions were registered according to the Charlson comorbidity index [26]; in general, absence of comorbidity is considered to be 0–1 point, low comorbidity 2 points and high comorbidity 3 or more points.

2.3. Definitions

The inclusion criteria of the selected studies included an age of at least 40 years and a post-bronchodilator FEV1(%) of 80% or less, and thus, mild COPD was arbitrarily defined as an FEV1(%) above 65% predicted, and young COPD was defined as the group of patients younger than 55 years old. We defined low smoking intensity as having an exposure between 10 to 20 pack-years, while >20 pack-years was considered high-intensity exposure. Therefore, early COPD was defined as an age younger than 55 years and smoking exposure of less than 20 pack-years. Although we are aware that in some patients COPD may start very early in life [27], with this definition we wanted to identify individuals who develop COPD at earlier stages of the disease compared to the remaining population. In order to further analyze the independent impact of age and smoking on the severity of airway limitation, patients were divided into four groups: (1) young low-intensity smokers (YLS), also defined as early COPD (<55 years old and ≤20 pack-years); (2) young high-intensity smokers (YHS) (<55 years old with >20 pack-years); (3) old low-intensity smokers (OLS) (≥55 years with ≤20 pack-years) and (4) old high-intensity smokers (OHS) (≥55 years old with >20 pack-years). According to current guidelines, severe COPD is defined by an FEV1(%) 30–50% and very severe COPD by an FEV1(%) < 30% [28].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The categorical variables were described with absolute frequencies and percentages. The description of quantitative variables was carried out using the mean and standard deviation (SD). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate the normality of the distributions. Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics were compared according to the age of the participants, tobacco consumption (pack-years) and lung function. In the case of quantitative variables, the Mann–Whitney U or Kruskal–Wallis tests, with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons, were carried out. The Chi-squared test (Fisher test for frequencies <5) was used for the comparison of categorical variables. Linear regression equations were performed to analyze the relationship between FEV1(%), age and pack-years. For all tests, p values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The R Studio statistical package (V4.3.3) was used for the analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Population

We screened 7520 patients with COPD, and among these, 5468 (72.7%) had complete and valid data on age, pulmonary function and smoking habit and were included in this analysis. The mean age was 67 (SD: 9.6) years, and 85% were male with a mean smoking consumption of 43.9 pack-years (25.4) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the population and comparisons between mild COPD and the remaining patients with COPD.

| Parameter | Subjects (N = 5468) |

Mild COPD * N = 1160 |

COPD with FEV1 < 65% N = 4308 |

p-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 67 (9.6) | 65.4 (10.1) | 67.4 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years | 43.9 (25.4) | 39.1 (23.1) | 45.2 (25.7) | <0.001 |

| Sex, male (%) | 4669 (85.4) | 876 (75.5) | 3788 (88.0) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.6 (4.6) | 27.7 (4.6) | 27.5 (4.5) | 0.249 |

| Charlson index | 2 (1.1) | 2.01 (1.0) | 2.04 (1.0) | 0.232 |

| mMRC | 1.50 (0.9) | 1.22 (0.6) | 1.58 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (mL) | 1519 (583) | 2213 (508) | 1340 (452) | <0.001 |

| FEV1(%) | 50.6 (17) | 75 (8.1) | 44.1 (12.1) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 53.6 (11.1) | 61.9 (6.7) | 51.3 (10.9) | <0.001 |

| Ambulatory exacerbations | 1.6 (1.9) | 1.59 (1.6) | 1.65 (1.9) | 0.943 |

| Admissions | 0.8 (1.4) | 0.54 (1.0) | 0.90 (1.5) | <0.001 |

| Total exacerbations | 2.5 (2.7) | 2.12 (2.1) | 2.55 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| CAT | 18.3 (8.6) | 15.9 (8.7) | 18.9 (8.4) | <0.001 |

| BODEx index | 2.6 (1.7) | 0.8 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.5) | <0.001 |

Footnote: * Mild COPD is defined as FEV1(%) ≥ 65%. Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. Kruskal–Wallis test a. Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index, mMRC, modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score, FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second, CAT, COPD assessment test; BODEx, body mass index, airway obstruction, dyspnea, exacerbation.

3.2. Mild COPD

A total of 1158 (21.2%) patients had mild COPD. Compared to more severe patients, those with mild COPD were younger (65.4 (10.1) vs. 67.4 (SD: 9.4) years, p < 0.001), more frequently female (24.4% vs. 12%, p < 0.001) and had lower tobacco exposure (39.1 (23.2) vs. 45.2 (25.8) pack-years; p < 0.001). As expected, they also had fewer symptoms, with lower mMRC and CAT scores and significantly less frequent exacerbations and hospital admissions. There were no differences in comorbidities recorded with the Charlson index (Table 1).

3.3. Young COPD

The group of young COPD consisted of 636 (11.6%) individuals younger than 55 years old. They were more frequently female (31% vs. 12.5%, p < 0.001) and with lower tobacco exposure (32.4 (19.0) vs. 45.5 (25.7) pack-years, p < 0.001). They also had fewer symptoms, with a lower CAT score. Differences in BODEx and FEV1, although statistically significant, were of small magnitude. No differences were found regarding the history and type of exacerbations (Table 2).

Table 2.

Comparisons of characteristics between mild COPD and the remaining patients with COPD.

| Parameter | Age < 55 Years Old N = 636 |

Age ≥ 55 Years Old N = 4827 |

p-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 50.3 (3.5) | 69.2 (7.9) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years | 32.4 (19.0) | 45.5 (25.7) | <0.001 |

| Sex, male (%) | 439 (69.0) | 4225 (87.5) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27 (5.3) | 27.6 (4.4) | <0.001 |

| Charlson index | 1.64 (0.8) | 2.08 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| mMRC | 1.32 (0.7) | 1.59 (0.7) | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (mL) | 1797 (644) | 1482 (564) | <0.001 |

| FEV1(%) | 54.5 (17.9) | 50.1 (16.8) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 55.1 (10.9) | 53.4 (11.1) | <0.001 |

| Ambulatory exacerbations | 1.65 (1.9) | 1.59 (1.6) | 0.557 |

| Admissions | 0.69 (1.3) | 0.84 (1.4) | 0.021 |

| Total exacerbations | 2.27 (2.5) | 2.49 (2.7) | 0.063 |

| CAT | 16.6 (8.6) | 18.5 (8.6) | <0.001 |

| BODEx index | 2.2 (1.7) | 2.6 (1.6) | <0.001 |

Footnote: Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. Kruskal–Wallis test a. Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index, mMRC, modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score, FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second, CAT, COPD assessment test; BODEx, body mass index, airway obstruction, dyspnea, exacerbation.

3.4. Early COPD

The group defined as early COPD consisted of 191 patients (3.5%), who were more frequently women (42.4% vs. 13.6%, p < 0.001) and had fewer comorbidities measured by the Charlson index than the remaining patients (1.5 (0.8) vs. 2.1 (1.1), p < 0.001). The FEV1(%) was better preserved in the early COPD group (58.4% (18.3%) vs. 50.4% (16.9%), p < 0.001), and they had fewer COPD admissions (0.5 (1.1) vs. 0.8 (1.4), p < 0.001), but no significant differences were found in the ambulatory COPD exacerbations (1.5 (1.9) vs. 1.6 (1.9), p = 0.418) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparisons of characteristics between early COPD and the remaining patients with COPD.

| Parameter | Early COPD * (N = 191) |

No Early COPD (N = 5272) |

p-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 49.7 (3.9) | 67.6 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Pack-years | 15.3 (3.7) | 45 (21.2) | <0.001 |

| Sex, male (%) | 110 (57.6) | 4554 (86.4) | < 0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 (4.7) | 27.6 (4.5) | <0.001 |

| Charlson index | 1.5 (0.8) | 2.1 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| mMRC | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| FEV1 (mL) | 1848 (641) | 1508 (577) | <0.001 |

| FEV1(%) | 58.4 (18.3) | 50.4 (16.9) | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC | 56.7 (11.1) | 53.5 (11) | <0.001 |

| Ambulatory exacerbations | 1.5 (1.9) | 1.6 (1.9) | 0.418 |

| Admissions | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Total exacerbations | 2 (2.4) | 2.5 (2.8) | 0.009 |

| CAT | 16.6 (8.3) | 18.3 (8.7) | 0.026 |

| BODEx index | 1.9 (1.6) | 2.6 (1.7) | <0.001 |

Footnote: * Early COPD is defined as age < 55 years and smoking exposure ≤ 20 pack-years. Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. a Mann–Whitney, o Chi-square test. Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index, mMRC, modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score, FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second, CAT, COPD assessment test, BODEx, body mass index, airway obstruction, dyspnea, exacerbation.

3.5. Comparison Between Groups Classified According to Age and Smoking Intensity

As previously described, younger patients were more frequently female, but even among younger patients, those with lower smoking exposure were significantly more frequently female compared with the high-intensity smoker young COPD patients (42.4% vs. 26.1%; p < 0.001).

There was a clear effect of age on comorbidities, with both groups of elderly patients (OLS and OHS) having a higher Charlson index compared to younger patients. However, a significant effect of smoking on comorbidities was only observed in young patients (1.5 (0.8) in YLS versus 1.7 (0.9) in YHS; p < 0.001).

Regarding lung function, not surprisingly, OHS had the worse FEV1(%) (49.7%) and YLS the best FEV1(%) (58.4%); but interestingly, FEV1(%) values did not significantly differ between YHS and OLS (52.8% vs. 52.6%). Nonetheless, dyspnea was significantly worse in OLS compared with YHS (mMRC of 1.5 (0.9) vs. 1.3 (0.9); p < 0.001). Dyspnea did not differ according to smoking but only according to age, and the same was true for symptoms measured by the CAT scores.

We observed no significant differences in the frequency of exacerbations among the four groups, but there was a combined effect of age and smoking on severe exacerbations, with only YLS having significantly less frequent severe exacerbations compared to the two groups of older patients (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of demographic, functional and clinical characteristics of patients according to age and accumulated smoking consumption.

| Young Patients | Old Patients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Young and Low Smoking (Early COPD) (N = 191) |

Young and High Smoking (N = 445) |

Old and Low Smoking (N = 740) |

Old and High Smoking (N = 4092) |

p-Value a |

| Age (years) | 49.7 (3.9) | 50.6 (3.3) | 68.1 (8.1) | 69.3 (7.9) | <0.001 cdfg |

| Pack-years | 15.3 (3.7) | 39.8 (18.2) | 15.5 (3.8) | 50.8 (24.2) | <0.001 bdfg |

| Sex, male (%) | 110 (57.6) | 329 (73.9) | 567 (76.6) | 3658 (89.5) | <0.001 bcd |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.6 (4.7) | 27.2 (5.6) | 27.6 (4.4) | 27.6 (4.5) | <0.001 cd |

| Charlson index | 1.5 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.9) | 2.1 (1.1) | 2.1 (1.1) | <0.001 cdef |

| mMRC | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.9) | <0.001 cdef |

| FEV1 (mL) | 1848 (640) | 1776 (645) | 1520 (562) | 1476 (564) | <0.001 cde |

| FEV1(%) | 58.4 (18.3) | 52.8 (17.1) | 52.6 (17.4) | 49.7 (16.7) | <0.001 bcdfg |

| FEV1/FVC | 56.7 (11.1) | 54.4 (10.7) | 54.9 (11) | 53.1 (11) | <0.001 bdg |

| Ambulatory exacerbations | 1.5 (1.9) | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.7 (1.9) | 1.6 (1.9) | 0.873 |

| Admissions | 0.5 (1.1) | 0.8 (1.5) | 0.9 (1.7) | 0.8 (1.4) | <0.001 cd |

| Total exacerbations | 2 (2.4) | 2.4 (2.6) | 2.6 (3.1) | 2.5 (2.7) | 0.023 c |

| CAT | 16.6 (8.3) | 16.6 (8.8) | 18.2 (8.8) | 18.5 (8.6) | 0.001 f |

| BODEx index | 1.9 (1.6) | 2.3 (1.8) | 2.4 (1.7) | 2.7 (1.7) | <0.001 cdfg |

Footnote: Data are presented as mean (SD) unless otherwise specified. Kruskal–Wallis test a. Abbreviations: BMI: body mass index, mMRC, modified Medical Research Council dyspnea score, FEV1: forced expiratory volume in one second, CAT, COPD assessment test; BODEx, body mass index, airway obstruction, dyspnea, exacerbation. (YLS vs. YHS) b, (YLS vs. OLS) c, (YLS vs. OHS) d, (YHS vs. OLS) e, (YHS vs. OHS) f, (OLS vs. OHS) g.

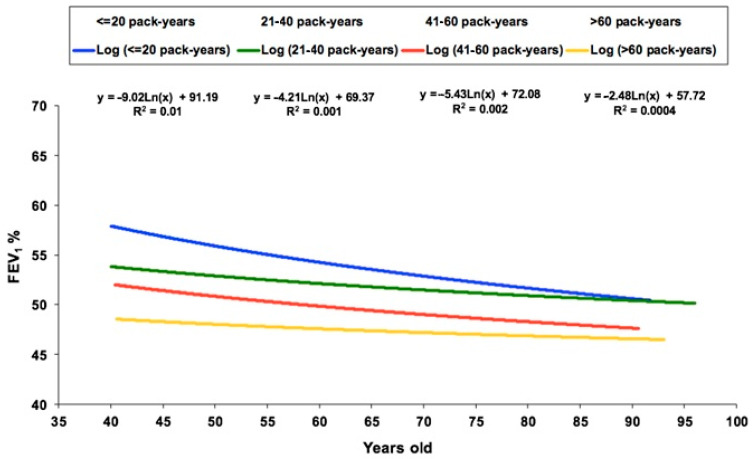

When plotting FEV1(%) versus age for the participants divided into four groups according to smoking consumption, we observed that at a younger age there were important differences in FEV1(%) according to the pack-years of smoking, but these differences progressively reduced with increasing age. In particular, there was a clear reduction in FEV1(%) with age in smokers of less than 20 pack-years, whereas the line was almost flat for smokers of more than 60 pack-years (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Linear regression equations of FEV1(%) and age according to the different groups of smoking exposure.

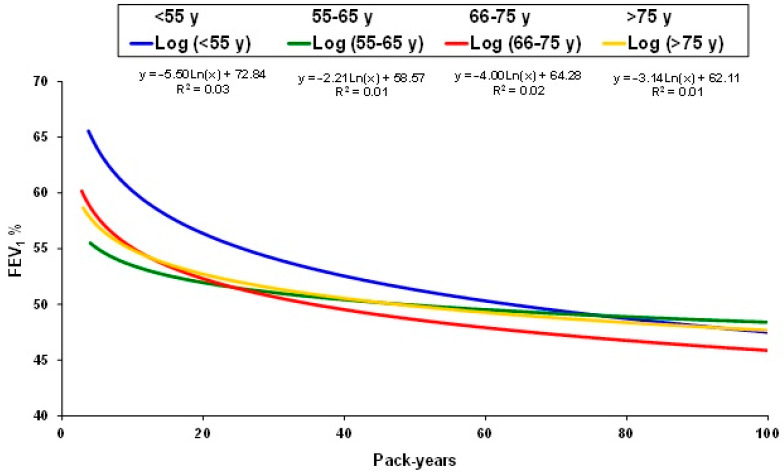

When plotting FEV1(%) versus pack-years by age subgroups, we observed that for all age groups the slope of decline in FEV1(%) was more pronounced for the first 20 pack-years, and again, this was more important in younger patients. Furthermore, this effect was more pronounced in individuals younger than 55 years old with less than 20 pack-years (early COPD) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Linear regression equations of FEV1(%) and smoking exposure according to the different age groups.

4. Discussion

In our large population of patients with COPD, around one fifth had mild COPD, and these patients were younger, more frequently female, with lower tobacco exposure and less symptomatic. Similarly, young COPD patients were also more frequently female, with lower tobacco exposure, less symptomatic and with a lower CAT score. On the other hand, patients defined as early COPD had a higher proportion of women and fewer comorbidities, their FEV1(%) was better preserved and they had fewer COPD admissions. However, differences in the frequency of ambulatory COPD exacerbations were not significantly different among the previous three groups of patients and the remaining patients with COPD. When analyzing the effect of age and tobacco exposure, we observed that the presence of comorbidities and symptoms were mainly influenced by age more than by smoking habits. In contrast, no differences were observed in the frequency of ambulatory exacerbations among the four different groups according to age and smoking exposure, while severe exacerbations were more frequent in elderly patients with high tobacco exposure.

Our large database provided an ideal opportunity to analyze different aspects of patients with COPD at early stages of the disease. First, we studied the characteristics of patients considered mild according to their level of impairment in FEV1(%). The most accepted definition of mild COPD includes patients with a post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC < 0.7 and a FEV1(%) > 80% predicted [28,29,30]. However, older definitions of mild disease, such as that used in the Lung Health Study by Anthonisen et al. [31], included patients with a FEV1(%) between 55–90%. Likewise, in other studies, the term “mild–moderate” was used for patients with a FEV1(%) ≥ 50% or GOLD II [32,33,34]. Since the population included in our study had a FEV1(%) below 80% as an inclusion criterion, we arbitrarily set the cut-off point for “mild COPD” at FEV1(%) ≥ 65%. Consequently, our results in mild COPD may not be completely comparable to other series defined by FEV1(%) > 80%. In any case, it may be useful to compare the characteristics of patients who have a less affected pulmonary function with the remaining “more severe” COPD patients. If we compare our group of mild COPD with other studies [8,32], we observe that they share common characteristics, such as having a higher proportion of women and less tobacco exposure. However, our mild patients had fewer symptoms than the groups classified as GOLD II, probably explained by the more preserved FEV1 of our cohort (65–80%). Conversely, our cohort of mild COPD had a higher exacerbation rate compared with the GOLD I-II patients described in the systematic review of Maltais et al. [8], which could be explained by the older mean age of our patients.

Several studies define young COPD as patients younger than 50 years old [12,35,36,37]; however, we used the threshold of 55 years because all our population was >40 years, and there were very few patients between 40 and 50 years of age. Nevertheless, our results were similar to those of other series [35,36,37], showing that young COPD patients were more frequently female, with less tobacco exposure and with a more preserved FEV1 than older patients. Interestingly, we found that the relationship between smoking and FEV1(%) showed the steepest slope in FEV1(%) in subjects <55 years compared with the other age groups. This is in agreement with previous studies that suggest that COPD may progress more rapidly in younger patients with a significant smoking history [10]. If we compare our data with a recent study by Tan et al. [37], who defined young COPD as patients between 20–50 years old, we find that our patients were more symptomatic. This may be explained, at least in part, because in their series 75% were never smokers, and the mean average of tobacco consumption among the smokers was only 5 pack-years. Moreover, their young COPD patients had a significant FEV1(%) reversibility and preserved diffusion capacity, which suggests that some of these patients might be affected by asthma instead. To avoid the misdiagnoses of young COPD in subjects with asthma, a significant smoking history or other exposures should be required.

Early COPD has gained increasing attention during recent years, although the lack of a universally accepted definition hinders the comparison of studies. An operational definition of early COPD has been proposed [12] as individuals younger than 50 years with 10 or more pack-years of smoking and one or more of the following abnormalities: (1) early airflow limitation, (2) compatible computerized tomography abnormalities and/or (3) a rapid decline in FEV1 (>60 mL/year). However, other definitions use only age, smoking and airflow limitation [10]. For example, Çolak et al. [38] and Cosío et al. [35] defined early COPD as individuals under 50 years of age with obstructive spirometry and a 10 pack-year or greater tobacco consumption.

As previously indicated, we used a threshold of 55 years in our series, and, since all our patients had at least 10 pack-years of tobacco exposure, we limited smoking to 20 pack-years in the definition of the early COPD group. This limit was established because some smokers may have already accumulated a substantial number of pack-years at a young age and, therefore, should not be considered to be initiating the damage to their lungs. Therefore, we defined early COPD as <55 years old and ≤20 pack-years, because these characteristics might select individuals closer to a real initial stage of the disease.

With our definition, we found that the patients classified as early COPD were more frequently women, with fewer comorbidities and with a better preserved FEV1(%) compared with the remaining COPD patients. Nonetheless, no significant differences were found in the frequency of ambulatory COPD exacerbations, which could be explained, in part, by a possible diagnostic bias, because in our early COPD cohort, patients were recruited after seeking care for symptoms or exacerbations; therefore, early COPD patients with lower symptom levels or without exacerbations may have remained undiagnosed.

When comparing our cohort of early COPD with other series [35,38], due to our definition, our patients were older and had less tobacco exposure. Despite that, the FEV1(%) of our patients was lower than that described by Çolak et al. [38], and, in addition, our population was more symptomatic and with a higher CAT score (16.6 vs. 12.5) than the early COPD patients described by Cosío et al. [35]. The higher severity of our population of early COPD (despite a lower smoking consumption) may be explained not only by the older mean age but also because our population consisted of previously diagnosed COPD patients followed in outpatient pulmonology clinics, while the previously described series derived from automatically generated lists of smokers from primary care [35] and from a population-based cohort [38]. Moreover, other characteristics, such as the proportion of asthma–COPD overlap patients in the different groups or the adherence to inhaled therapy, were not registered in the original studies and therefore could not be assessed in the current pooled analysis [39]. Our early COPD patients are surely in more initial stages than the rest of the group, but their mean FEV1(%) of 54.8% suggests that they are already in a moderately advanced stage of the disease. To truly identify patients in early stages of COPD, we should improve the early diagnosis of COPD, probably through case detection strategies [40,41,42,43].

These findings are relevant, because mild, young and early COPD patients presented a similar rate of moderate exacerbations compared to more severe or elderly patients, and exacerbations are associated with a more rapid decline in lung function, worse quality of life and decreased exercise capacity [44,45,46]. Moreover, we observed a steeper decline in FEV1(%) in individuals under 55 years of age with less than 20 pack-years, which highlights the importance of an early detection and implementation of preventive and therapeutic measures.

Our definitions of mild, young and early COPD are not mutually exclusive, and, therefore, patients included in these categories share several common characteristics. The most important of these shared characteristics is the higher prevalence of females compared with the remaining patients, and they are also less symptomatic, with a better CAT score and less frequent severe exacerbations. The higher frequency of women in early stages of the disease has also been observed in other studies [47,48] and could be due to a greater susceptibility of women to smoking [49]. Furthermore, the rate of underdiagnoses of COPD is greater in women [4,50], in part due to differences in the attitudes of physicians towards women with respiratory symptoms, with the risk of being mislabeled as asthmatics [51]. Therefore, accurately identifying this group of patients should be of particular interest for early diagnosis and treatment.

A combined effect of age and smoking was observed with the Charlson comorbidity index. Increasing age has been correlated with an increase in comorbidities [52,53], and, similarly, a higher smoking load has also been associated with more comorbidities. In contrast, we found no significant differences in the frequency of ambulatory exacerbations according to age and smoking exposure, but age had a significant impact on severe exacerbations, in agreement with the widely recognized effect of aging as a risk factor for admissions [54].

The main limitation of our analysis is that our data were cross-sectional, and therefore we could not analyze the natural course of the different forms of COPD. Furthermore, due to the inclusion criteria of the selected studies, our definitions of mild, young and early COPD may differ from other definitions, which could make direct comparisons between studies more challenging. However, we believe that the large study sample from all areas from Spain and from primary and secondary care provides a unique opportunity to characterize these “mild” patients.

5. Conclusions

The definition of early COPD should include variables that identify patients in a stage close to the onset of the disease. The concepts of mild or young patients may not be accurate enough to define this group. Among the young and mild patients, there are more women than in the rest of the groups, a characteristic that is shared with our definition of early COPD. The steepest decline in FEV1(%) was observed in individuals under 55 years of age with less than 20 pack-years of smoking, which highlights the importance of an early detection and implementation of preventive and therapeutic measures. These results must be confirmed in longitudinal studies.

Acknowledgments

Cristina Aljama is a recipient of a SEPAR (Spanish Society of Pneumology and Thoracic Surgery) 2023-2024 Research Fellowship.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.A., C.E., M.M. and M.B.; methodology, C.A., C.E., M.M. and M.B.; software, C.A. and C.E.; validation and formal analysis, C.A., C.E., M.B. and M.M.; investigation, C.A., C.E., E.L., G.G., A.N., A.L.-G., M.M. and M.B.; resources and data curation, C.A., C.E., E.L., G.G., A.N., A.L.-G., M.M. and M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, C.A., C.E., M.M., G.G. and M.B.; writing—review and editing, C.A., C.E., E.L., G.G., A.N., M.M. and M.B.; visualization, C.A., C.E., E.L., G.G., A.N., A.L.-G., M.M. and M.B.; supervision, M.M. and M.B.; project administration M.M. and M.B. All authors contributed to the data analysis, the result interpretation and drafting and revising the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The four studies analyzed in the current work were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hospital Clínic (Barcelona, Spain), protocol code 2012/7962, on the date 22 November 2012 for the FyCEPOC study; Hospital Clínic (Barcelona, Spain), protocol code 2007/3793, on the date 19 July 2007 for the NEREA study; Hospital Clínic (Barcelona, Spain), protocol code 2009/5252, on the date 10 September 2009 for the INSEPOC study; and Hospital Clínic (Barcelona, Spain), protocol code 2011/6645, on the date 28 April 2011 for the DEPREPOC study.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Cristina Aljama has received speaker fees from FAES farma, Chiesi, AstraZeneca, Zambon, GSK and CSL Behring. Galo Granados has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Zambon and GlaxoSmithKline. Marc Miravitlles has received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, Menarini, Rovi, Bial, Kamada, Takeda, Sandoz, Zambon, CSL Behring, Specialty Therapeutics, Janssen, Grifols and Novartis; consulting fees from AstraZeneca, Atriva Therapeutics, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Bial, Gebro Pharma, CSL Behring, Inhibrx, Laboratorios Esteve, Ferrer, Menarini, Mereo Biopharma, Verona Pharma, Spin Therapeutics, ONO Pharma, pH Pharma, Palobiofarma SL, Takeda, Novartis, Sanofi and Grifols; and research grants from Grifols. Miriam Barrecheguren has received speaker fees from CSL Behring, Grifols, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline and Menarini and consulting fees from CSL Behring and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Funding Statement

The FyCEPOC and INSEPOC studies were funded by Laboratorios Esteve S.A (Barcelona, Spain). The NEREA study was funded by an unrestricted grant from J. Uriach y Compañía S.A (Barcelona, Spain). The DEPREPOC study was funded by Grupo Ferrer (Barcelona, Spain). No funding was received for the analysis, writing or submission of the current manuscript. The funding bodies had no involvement in the analysis and interpretation of data, the writing of the report or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.GBD Chronic Respiratory Disease Collaborators Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020;8:585–596. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30105-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Castillo E.G., Pérez T.A., Peláez A., González P.P., Miravitlles M., Alfageme I., Casanova C., Cosío B.G., de Lucas P., García-Río F., et al. Trends of COPD in Spain: Changes Between Cross Sectional Surveys 1997, 2007 and 2017. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023;59:142–151. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2022.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blanco I., Diego I., Bueno P., Casas-Maldonado F., Miravitlles M. Geographic distribution of COPD prevalence in the World displayed by Geographic Information System maps. Eur. Respir. J. 2019;54:1900610. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00610-2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scicluna V., Han M. COPD in Women: Future Challenges. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023;59:3–4. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2022.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rey-Brandariz J., Pérez-Ríos M., Ahluwalia J.S., Beheshtian K., Fernández-Villar A., Represas-Represas C., Piñeiro M., Alfageme I., Ancochea J., Soriano J.B., et al. Tobacco Patterns and Risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: Results From a Cross-Sectional Study. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023;59:717–724. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2023.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lange P., Celli B., Agusti A., Boje Jensen G., Divo M., Faner R., Guerra S., Marott J.L., Martinez F.D., Martinez-Camblor P., et al. Lung-function trajectories leading to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015;373:111–122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Melén E., Faner R., Allinson J.P., Bui D., Bush A., Custovic A., Garcia-Aymerich J., Guerra S., Breyer-Kohansal R., Hallberg J., et al. Lung-function trajectories: Relevance and implementation in clinical practice. Lancet. 2024;403:1494–1503. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00016-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maltais F., Dennis N., Chan C.K. Rationale for earlier treatment in COPD: A systematic review of published literature in mild-to-moderate COPD. COPD J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2013;10:79–103. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2012.719048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Çolak Y., Afzal S., Nordestgaard B.G., Lange P., Vestbo J. Importance of Early COPD in Young Adults for Development of Clinical COPD: Findings from the Copenhagen General Population Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021;203:1245–1256. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202003-0532OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rennard S.I., Drummond M.B. Early chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Definition, assessment, and prevention. Lancet. 2015;385:1778–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60647-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Soriano J.B., Polverino F., Cosio B.G. What is early COPD and why is it important? Eur. Respir. J. 2018;52:1801448. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01448-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Martinez F.J., Han M.K., Allinson J.P., Barr R.G., Boucher R.C., Calverley P.M., Celli B.R., Christenson S.A., Crystal R.G., Fagerås M., et al. At the Root: Defining and Halting Progression of Early Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;197:1540–1551. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201710-2028PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kostikas K., Price D., Gutzwiller F.S., Jones B., Loefroth E., Clemens A., Fogel R., Jones R., Cao H. Clinical Impact and Healthcare Resource Utilization Associated with Early versus Late COPD Diagnosis in Patients from UK CPRD Database. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2020;15:1729–1738. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S255414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curtis J.L., Bateman L.A., Murray S., Couper D.J., Labaki W.W., Freeman C.M., Arnold K.B., Christenson S.A., Alexis N.E., Kesimer M., et al. Design of the SPIROMICS Study of Early COPD Progression: SOURCE Study. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2024;11:444–459. doi: 10.15326/jcopdf.2023.0490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim T., Kim J., Kim J.H. Characteristics and Prevalence of Early Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease in a Middle-Aged Population: Results from a Nationwide-Representative Sample. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021;16:3083–3091. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S338118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhatt S.P. Early Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or Early Detection of Mild Disease? Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018;198:411–412. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201802-0257LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siafakas N., Bizymi N., Mathioudakis A., Corlateanu A. EARLY versus MILD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) Respir. Med. 2018;140:127–131. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang W., Li F., Li C., Meng J., Wang Y. Focus on Early COPD: Definition and Early Lung Development. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2021;16:3217–3228. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S338359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miravitlles M., Naberan K., Cantoni J., Azpeitia A. Socioeconomic status and health-related quality of life of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respiration. 2011;82:402–408. doi: 10.1159/000328766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miravitlles M., Barrecheguren M., Román-Rodríguez M. Frequency and characteristics of different clinical phenotypes of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis. 2015;19:992–998. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miravitlles M., Llor C., de Castellar R., Izquierdo I., Baró E., Donado E. Validation of the COPD severity score for use in primary care: The NEREA study. Eur. Respir. J. 2009;33:519–527. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00087208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miravitlles M., Molina J., Quintano J.A., Campuzano A., Pérez J., Roncero C. Factors associated with depression and severe depression in patients with COPD. Respir. Med. 2014;108:1615–1625. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bestall J.C., Paul E.A., Garrod R., Garnham R., Jones P.W., Wedzicha J.A. Usefulness of the Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea scale as a measure of disability in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Thorax. 1999;54:581–586. doi: 10.1136/thx.54.7.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones P.W., Harding G., Berry P., Wiklund I., Chen W.H., Leidy N.K. Development and first validation of the COPD Assessment Test. Eur. Respir. J. 2009;34:648–654. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Soler-Cataluña J.J., Martínez-García M.A., Sánchez L.S., Tordera M.P., Sánchez P.R. Severe exacerbations and BODE index: Two independent risk factors for death in male COPD patients. Respir. Med. 2009;103:692–699. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charlson M.E., Pompei P., Ales K.L., MacKenzie C.R. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J. Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmoud O., Granell R., Peralta G.P., Garcia-Aymerich J., Jarvis D., Henderson J., Sterne J. Early-life and health behaviour influences on lung function in early adulthood. Eur. Respir. J. 2023;61:2001316. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01316-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agustí A., Celli B.R., Criner G.J., Halpin D., Anzueto A., Barnes P., Bourbeau J., Han M.K., Martinez F.J., de Oca M.M., et al. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2023 Report: GOLD Executive Summary. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023;59:232–248. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2023.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radovanovic D., Contoli M., Braido F., Maniscalco M., Micheletto C., Solidoro P., Santus P., Carone M. Future Perspectives of Revaluating Mild COPD. Respiration. 2022;101:688–696. doi: 10.1159/000524102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brems J.H., Balasubramanian A., Raju S., Putcha N., Fawzy A., Hansel N.N., Wise R.A., McCormack M.C. Changes in Spirometry Interpretative Strategies: Implications for Classifying COPD and Predicting Exacerbations. Chest. 2024;166:294–303. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2024.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anthonisen N.R., Connett J.E., Kiley J.P., Altose M.D., Bailey W.C., Buist A.S., Conway W.A., Enright P.L., Kanner R.E., O’hara P., et al. Effects of smoking intervention and the use of an inhaled anticholinergic bronchodilator on the rate of decline of FEV1. The Lung Health Study. JAMA. 1994;272:1497–1505. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03520190043033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barrecheguren M., González C., Miravitlles M. What have we learned from observational studies and clinical trials of mild to moderate COPD? Respir. Res. 2018;19:177. doi: 10.1186/s12931-018-0882-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woodruff P.G., Barr R.G., Bleecker E., Christenson S.A., Couper D., Curtis J.L., Gouskova N.A., Hansel N.N., Hoffman E.A., Kanner R.E., et al. Clinical Significance of Symptoms in Smokers with Preserved Pulmonary Function. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;374:1811–1821. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de-Torres J.P., Casanova C., Marín J.M., Cabrera C., Marín M., Ezponda A., Cosio B.G., Martínez C., Solanes I., Fuster A., et al. Impact of Applying the Global Lung Initiative Criteria for Airway Obstruction in GOLD Defined COPD Cohorts: The BODE and CHAIN Experience. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2024;60:10–15. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2023.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cosío B.G., Pascual-Guardia S., Borras-Santos A., Peces-Barba G., Santos S., Vigil L., Soler-Cataluña J.J., Martínez-González C., Casanova C., Marcos P.J., et al. Phenotypic characterisation of early COPD: A prospective case-control study. ERJ Open Res. 2020;6:00047–02020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00047-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinez F.J., Agusti A., Celli B.R., Han M.K., Allinson J.P., Bhatt S.P., Calverley P., Chotirmall S.H., Chowdhury B., Darken P., et al. Treatment Trials in Young Patients with Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease and Pre-Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Patients: Time to Move Forward. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022;205:275–287. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202107-1663SO. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tan L., Li Y., Wang Z., Wang Z., Liu S., Lin J., Huang J., Liang L., Peng K., Gao Y., et al. Comprehensive appraisal of lung function in young COPD patients: A single center observational study. BMC Pulm. Med. 2024;24:358. doi: 10.1186/s12890-024-03165-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Çolak Y., Afzal S., Nordestgaard B.G., Vestbo J., Lange P. Prevalence, Characteristics, and Prognosis of Early Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. The Copenhagen General Population Study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2020;201:671–680. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201908-1644OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polverino F., Celli B. Challenges in the Pharmacotherapy of COPD Subtypes. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2023;59:284–287. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2022.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shen X., Liu H. Using machine learning for early detection of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A narrative review. Respir. Res. 2024;25:336. doi: 10.1186/s12931-024-02960-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schnieders E., Ünal E., Winkler V., Dambach P., Louis V.R., Horstick O., Neuhann F., Deckert A. Performance of alternative COPD case-finding tools: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2021;30:200350. doi: 10.1183/16000617.0350-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Su K.C., Hsiao Y.H., Ko H.K., Chou K.T., Jeng T.H., Perng D.W. The Accuracy of PUMA Questionnaire in Combination with Peak Expiratory Flow Rate to Identify At-risk, Undiagnosed COPD Patients. Arch. Bronconeumol. 2024. in press . [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Llordés M., Zurdo E., Jaén A., Vázquez I., Pastrana L., Miravitlles M. Which is the best screening strategy for COPD among smokers in Primary Care? COPD J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2017;14:43–51. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2016.1239703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Santus P., Di Marco F., Braido F., Contoli M., Corsico A.G., Micheletto C., Pelaia G., Radovanovic D., Rogliani P., Saderi L., et al. Exacerbation Burden in COPD and Occurrence of Mortality in a Cohort of Italian Patients: Results of the Gulp Study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2024;19:607–618. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S446636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Soler-Cataluña J.J., Izquierdo J.L., Juárez Campo M., Sicras-Mainar A., Nuevo J. Impact of COPD Exacerbations and Burden of Disease in Spain: AVOIDEX Study. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023;18:1103–1114. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S406007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Anzueto A. Impact of Exacerbations on Copd. Eur. Respir. Rev. 2010;19:113–118. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00002610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prescott E., Bjerg A.M., Andersen P.K., Lange P., Vestbo J. Gender difference in smoking effects on lung function and risk of hospitalization for COPD: Results from a Danish longitudinal population study. Eur. Respir. J. 1997;10:822–827. doi: 10.1183/09031936.97.10040822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roche N., Deslée G., Caillaud D., Brinchault G., Court-Fortune I., Nesme-Meyer P., Surpas P., Escamilla R., Perez T., Chanez P., et al. Impact of gender on COPD expression in a real-life cohort. Respir. Res. 2014;15:20. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-15-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buttery S.C., Zysman M., Vikjord S.A.A., Hopkinson N.S., Jenkins C., Vanfleteren L.E.G.W. Contemporary perspectives in COPD: Patient burden, the role of gender and trajectories of multimorbidity. Respirology. 2021;26:419–441. doi: 10.1111/resp.14032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenkins C.R., Chapman K.R., Donohue J.F., Roche N., Tsiligianni I., Han M.K. Improving the Management of COPD in Women. Chest. 2017;151:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2016.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chapman K.R., Tashkin D.P., Pye D.J. Gender bias in the diagnosis of COPD. Chest. 2001;119:1691–1695. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.6.1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Divo M.J., Martinez C.H., Mannino D.M. Ageing and the epidemiology of multimorbidity. Eur. Respir. J. 2014;44:1055–1068. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00059814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Agustí A., Noell G., Brugada J., Faner R. Lung function in early adulthood and health in later life: A transgenerational cohort analysis. Lancet Respir. Med. 2017;5:935–945. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(17)30434-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Qian Y., Cai C., Sun M., Lv D., Zhao Y. Analyses of Factors Associated with Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Review. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023;18:2707–2723. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S433183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.