Abstract

Background:

Superficial cutaneous fungal infections are common dermatologic conditions. A significant proportion do not present with typical clinical findings. However, the 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) smear, a simple bedside test, is often underused when diagnosing cutaneous fungal infections.

Aims:

We aimed to evaluate whether KOH smear results altered dermatologists’ diagnosis and management, and the factors that influenced its ability to detect cutaneous fungal infections.

Methods:

A total of 373 patients with suspected cutaneous fungal infection were identified retrospectively from the dermatology database of inpatient referrals in a Singapore tertiary hospital between 1 January 2017 and 30 June 2020. The dermatologists’ eventual diagnoses, based on their assessment until 2 months post-discharge to allow consideration of KOH smear results and response to treatment, were taken as a gold standard. Statistical analyses evaluated for changes between initial and eventual diagnoses and management relative to the KOH smear. Use of topical steroids, topical and/or systemic antifungals before skin sampling, and whether sampling was done by dermatologically-trained personnel, were assessed for association with KOH smear positivity in eventually diagnosed cases.

Results:

The percentage of uncertain diagnoses was reduced, and the use of topical antifungal as the sole treatment significantly changed after the KOH smear result was available. The adjusted odds ratio of a positive KOH smear in eventually diagnosed cases was 0.19 when systemic antifungals were used before skin sampling, and 3.03 if sampling was performed by a dermatologically-trained person.

Limitations:

Limitations of our study include dependence on retrospective medical records which may result in misclassification bias and the limited generalisability of our results to patients managed by non-dermatologists.

Conclusions:

KOH smear is a useful adjunct in diagnosing and managing cutaneous fungal infections. Clinicians should consider the presence of confounders affecting KOH smears when making an overall clinical diagnosis. Focused training of personnel on skin sample collection may improve the detection rate of KOH smear.

KEY WORDS: Candidiasis, dermatomycoses, Malassezia, potassium hydroxide, tinea

Introduction

Cutaneous fungal infections are one of the most common dermatological conditions referred to a dermatologist for diagnosis and management.[1] Although the majority of cases demonstrate characteristic morphology and distribution of cutaneous lesions, there is still a significant number of cases where there may be diagnostic dilemmas.

A skin scraping of a suspected skin lesion followed by 10% potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation to identify fungal elements is a non-invasive and relatively low-risk investigation that can quickly confirm a diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection.[2] Experts recommend confirming a clinical diagnosis of superficial cutaneous fungal infections by the use of direct microscopy, culture or histology before genus/species-targeted treatment.[3,4] In clinical practice, however, treatment is often instituted on purely clinical grounds, with a decreasing number of dermatologists in the United States (US) utilising KOH smears over the years.[5] One contributing factor is the perception that a dermatologist’s clinical diagnosis sufficed.[6]

Indeed, as there is no universally accepted laboratory investigation with a 100% sensitivity or specificity, an experienced clinician’s opinion has been held as either a stand-alone gold standard, or in conjunction with other mycologic investigations, against which to evaluate the sensitivity and specificity of KOH smear for detection of tinea pedis, onychomycosis and oral candidiasis in research and clinical trials.[7,8,9] Yet, it has been found that even US board-certified dermatologists were able to clinically diagnose only 4 out of 13 dermatophytosis cases accurately more than 75% of the time.[10] A prospective survey of patients who experienced errors of diagnosis or management of their cutaneous disease before a dermatologist’s assessment found that 88% of these mistakes were in diagnosis, with a propensity towards overdiagnosis of infectious conditions such as cutaneous fungal infections.[11] Additionally, 35.3% of lesions stratified by a dermatologist to have a low clinical suspicion of tinea pedis yielded at least 1 positive KOH smear out of 3 repeated tests.[12] These illustrate that an irrefutable diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection cannot be made purely on clinical findings.

The utility of a KOH smear in terms of altering the initial diagnosis and subsequent management has rarely been studied. Stratification of lesions based on clinical suspicion of cutaneous fungal infection affects the positivity rate of KOH smear, though whether the eventual diagnosis is altered after KOH smear results remains unknown.[12] Therefore, we sought to evaluate whether the KOH smear added value to dermatologists’ assessment and management of suspected cutaneous fungal infection, overall and in clinical suspicion-stratified situations. We sought also to determine whether the use of antifungals before skin sampling and the experience of the person performing skin sampling could influence the detection rate of KOH smear for cutaneous fungal infections.

Patients and Methods

Study design

We retrospectively analysed changes in dermatologists’ clinical diagnosis of suspected cutaneous fungal infection and management relative to KOH smear results in a defined cohort based on clinical records. Ethics approval, with a waiver of informed consent, was obtained from the local research ethics board before the commencement of this study.

Setting and inclusion criteria [Supplementary Table S1]

Supplementary Table S1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| 1. All inpatient referrals to Dermatology service between 1 January 2017 and 30 June 2020 in whom a cutaneous fungal infection was suspected on initial review by the dermatologist. |

| 2. Cutaneous fungal infections included in our study are: |

| a. Superficial dermatophyte infections such as tinea |

| b. Superficial yeast infections such as pityrosporum folliculitis |

| c. Intertrigo for which cutaneous fungal infection was suspected and evaluated for |

| d. Deep cutaneous fungal infections or disseminated cutaneous fungal infections such as disseminated candidiasis |

| 3. KOH smear was recommended by the dermatologist to evaluate the suspected cutaneous fungal infection and was performed. |

| 4. The result of the KOH smear was reviewed by the dermatologist within the same admission. |

| 5. Management plans were given after the KOH smear result was reviewed. |

| Exclusion criteria |

| 1. Patients who were receiving systemic antifungals for reasons other than suspected cutaneous fungal infection, such as for prophylaxis in an immunocompromised patient |

| 2. Mucosal fungal infections |

| 3. Onychomycosis |

| 4. Patients whose KOH smear results were not reviewed by the dermatologist within the same admission and thus did not receive timely management plans from the dermatologist |

The cohort was defined to include all inpatients of a tertiary hospital in Singapore who had been referred to the dermatology service between 1 January 2017 and 30 June 2020, in whom a cutaneous fungal infection was suspected upon initial review by a dermatologist and KOH smear was performed. Outpatients were excluded due to the lack of a routine compilation of records in this setting. The medical records of included patients were reviewed between the date on which they were first assessed by a dermatologist to potentially have cutaneous fungal infection, until 2 months after discharge.

Data collection

Potential cases were identified from the cohort using the search terms ‘tinea’, ‘candida’, ‘fungus’, ‘fungal’, ‘scrape’, ‘intertrigo’, ‘versicolor’ and ‘folliculitis’. Two independent authors (XQK, HRH) assessed individual cases for suitability for inclusion. The following information was obtained: whether the referring physician suspected a cutaneous fungal infection, the dermatologist’s level of clinical suspicion of cutaneous fungal infection and initial diagnosis, the use of topical steroids or antifungals before review by the dermatologist, after an initial review by the dermatologist but before KOH smear result, and after the result was reviewed by the dermatologist. Whether skin sampling was done by dermatologically-trained or non-dermatologically-trained personnel and if the test was repeated in the same setting, as well as the eventual diagnosis, and clinical outcome in the same admission and within 2 months of discharge, were also collected. Diagnoses were categorised into ‘superficial dermatophyte’, ‘superficial yeast’, ‘intertrigo’, ‘deep fungal infection’ and ‘uncertain’.

Qualitative variables [Supplementary Table S2]

Supplementary Table S2.

Definitions in this study

| Definition of clinical suspicion group |

| 1. High clinical suspicion of cutaneous fungal infection: |

| a. The dermatologist recommended to start topical or systemic antifungal treatment before the result of the KOH smear was available, for the purposes of treating the suspected cutaneous fungal infection, without specifying to stop treatment in the event of a negative KOH smear. |

| b. The dermatologist starts treatment with topical or systemic antifungal for clinically diagnosed cutaneous fungal infection despite a negative KOH smear |

| 2. Medium clinical suspicion of cutaneous fungal infection: |

| a. The dermatologist recommended to start topical or systemic antifungal treatment before the result of KOH smear was available, for the purposes of treating the suspected cutaneous fungal infection, but specified on initial documentation to stop treatment in the event of a negative KOH smear. |

| b. The dermatologist recommended to wait for the KOH smear result and to start treatment in accordance with the result. |

| 3. Low clinical suspicion of cutaneous fungal infection: |

| a. The dermatologist does not start topical or systemic antifungal until he/she has reviewed the KOH result and made a revised diagnosis. |

| b. The dermatologist recommended to start treatment for an alternative diagnosis that was deemed likelier, before the result of the KOH smear. This may include conditions that are also sometimes treated with antifungal agents but are not considered cutaneous fungal infections, such as seborrheic dermatitis. |

| Definition of topical antifungal agent |

| - The following classes of antifungals were classified under antifungal treatment in this study: |

| • Imidazoles |

| • Polyenes |

| • Thiocarbamates |

| • Benzoxaborole |

| • Ciclopirox olamine |

| • Morpholine |

| - Broad-spectrum antiseptics such as fucidic acid, clioquinol, mupirocin were not considered to be antifungal treatments. |

| - In cases where combination creams were used, each separate active ingredient was documented accordingly, for example, miconazole with hydrocortisone would have been documented as both topical steroid and topical antifungal. |

We retrospectively classified the dermatologist’s initial clinical suspicion of cutaneous fungal infection to be high, medium or low. For brevity, ‘high clinical suspicion’, ‘medium clinical suspicion’ and ‘low clinical suspicion’ will henceforth refer to the clinical suspicion of cutaneous fungal infection.

Patients who were recommended by the dermatologist to start antifungal treatment either upon initial review before the KOH smear result, or even after a negative result, were classified as having high clinical suspicion. Patients who were given instructions to either empirically start antifungal treatment and stop in the event of a negative KOH smear result or to await results for guidance, were classified as medium clinical suspicion. Patients who were recommended treatment for other likelier non-fungal diagnoses on initial review with KOH smear requested chiefly to rule out cutaneous fungal infection as a differential diagnosis of the primary diagnosis, and who were not recommended antifungals before the result was reviewed, were classified as low clinical suspicion.

Skin sampling was categorised as being performed by non-dermatologically-trained or dermatologically-trained personnel. As a tertiary teaching hospital, non-subspecialised junior doctors rotate between teams and would be closely supervised by the permanent staff of the dermatology service. For simplicity, persons not part of the contemporaneous dermatology team (comprising of junior doctor, dermatology resident, dermatology technician and dermatologist), were considered non-dermatologically-trained personnel.

The dermatologist’s initial diagnosis on the first review before the KOH smear was defined to be positive for cutaneous fungal infection in those suspected to have high clinical suspicion, negative in those suspected to have low clinical suspicion, and uncertain in those suspected to have medium clinical suspicion. The dermatologist’s eventual diagnosis was defined to be the last documented diagnosis about the initial suspected cutaneous fungal infection, at the last clinical entry by the dermatologist within 2 months of discharge. This was chosen to be the gold standard diagnosis as the dermatologist would have had time to first formulate the initial clinical diagnosis, then refine the diagnosis based on KOH smear results, and finally conclude the diagnosis based on clinical evolution in tandem with treatment.

The dermatologist’s management was also defined according to these phases of clinical care. The initial management refers to the dermatologist’s decision regarding antifungal treatment based upon the first review before the KOH smear result was available. The eventual management refers to that recommended by the dermatologist after the KOH smear result was reviewed.

Bias

Two main potential biases of our study were selection bias and differential loss to follow-up. As our study included only those referred to and assessed by a dermatologist in an inpatient setting, selection bias may improve the predictive values of the KOH test. There is no statistical method that can control for this bias, and this will be discussed as a limitation. By selecting only inpatients and analysing the parameters during and up to 2 months after their hospitalisation, the effect of differential loss to follow-up would be minimal on the data required for evaluating our objectives.

Statistical methods

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS®. McNemar-Bowker test of independence was used to compare changes in diagnosis and management. Logistic regression was evaluated for the association of potential confounders with the detection rate of KOH smear in diagnosed cases. Significance was assessed at a level of 0.05.

Results

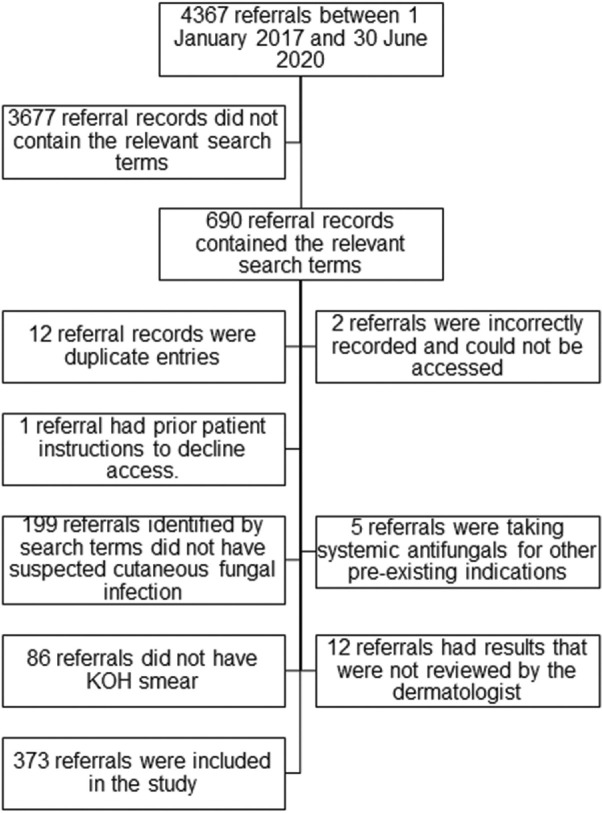

Our dermatology service received 4367 inpatient referrals between 1 January 2017 and 30 June 2020. Of these, 690 referral records were identified using the specified search terms. After the exclusion of ineligible records, 373 referrals were included in this study [Figure 1]. The number of referrals assessed to have high, medium, and low clinical suspicion were 229, 80 and 64, respectively.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants included and excluded from the study

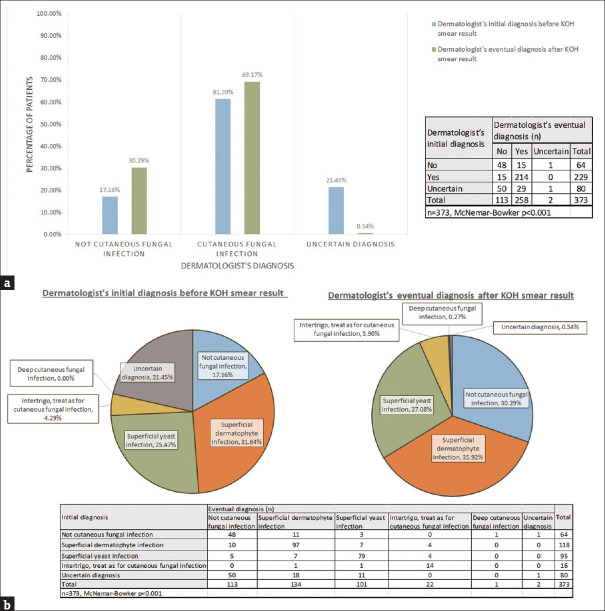

Change in eventual diagnosis after KOH smear [Figure 2a and b]

Figure 2.

Comparison of the dermatologist’s initial and eventual diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection before and after KOH smear result a: Comparison of the dermatologist’s initial and eventual diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection before and after KOH smear result in the entire cohort b: Comparison of the dermatologist’s initial and eventual diagnosis of the specific type of cutaneous fungal infection before and after KOH smear result in the entire cohort

There was a significant reduction in the percentage of eventual uncertain diagnoses, and a significant difference in the number of patients eventually diagnosed with cutaneous fungal infections after the KOH smear result was available [Figure 2a, P < 0.001]. The specific type of cutaneous fungal infection eventually diagnosed was significantly changed with the knowledge of KOH smear result, particularly in the medium and low suspicion groups [Figure 2b, P < 0.001]. In the high suspicion group, the eventual type of specific cutaneous infection was also altered by the KOH smear result [Supplementary Figure S1].

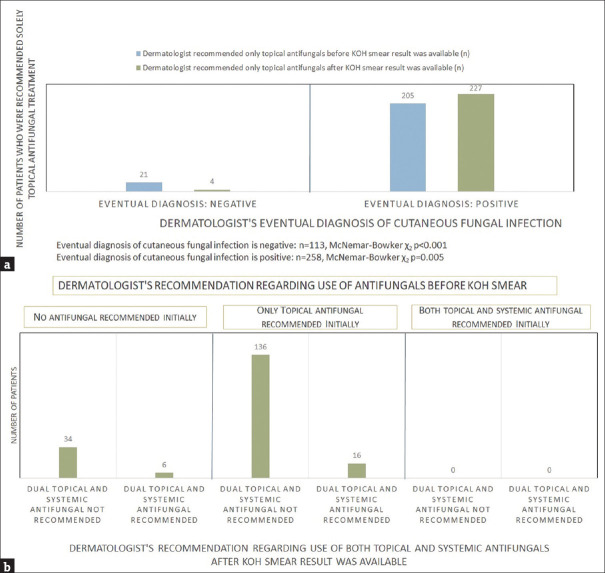

Change in eventual management (comparison of antifungal use) after KOH smear [Figure 3a and b]

Figure 3.

Comparison of the dermatologist’s management before and after KOH smear result was available a: Comparison of the dermatologist’s recommendation for the use of only topical antifungals before and after KOH smear result was available b: Comparison of the dermatologist’s recommendation for the use of topical and systemic antifungals before and after KOH smear result was available in those with positive KOH Smear and an eventual diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection

The dermatologist’s recommendation for only topical antifungal treatment significantly differed before compared to after the KOH result was reviewed, following the eventual diagnosis (Figure 3a, P < 0.001 when the eventual diagnosis was negative, P = 0.005 when eventual diagnosis was positive). Four exceptions were noted, where patients who received an eventual negative diagnosis for cutaneous fungal infection were still recommended topical antifungal treatment by the dermatologist [Supplementary Table S3]. When comparing the use of only systemic antifungal treatment, there was no significant change before compared to after the KOH smear result was available (n = 2 vs n = 3, P = 1). Seventeen of those diagnosed with a cutaneous fungal infection, who had been given only topical antifungal prior (n = 204), were recommended for dual topical and systemic treatment after KOH smear result (16/17 positive). Seven of those who did not receive empiric antifungal and were subsequently diagnosed (n = 52) were recommended dual topical and systemic antifungal, of whom 6 had positive KOH smear results [Figure 3b].

Supplementary Table S3.

Patients who were recommended topical antifungal treatment despite a negative eventual diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection

| Patient | Clinical suspicion group | Initial diagnosis and management before results of KOH smear | KOH Smear result | Eventual diagnosis and treatment | Rationale for continued use of topical antifungal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low | Seborrhoeic dermatitis, to exclude tinea faciei. No empiric treatment with topical antifungal. | Negative | Seborrhoeic dermatitis | Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis |

| 2 | Low | Seborrhoeic dermatitis, to exclude pityrosporum folliculitis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus infection who previously had pityrosporum folliculitis of the face. No empiric treatment with topical antifungal. | Negative | Seborrhoeic dermatitis | Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis |

| 3 | High | Tinea corporis, differential of irritant contact dermatitis. Empiric treatment with a combination cream of antifungal and steroid. | Negative | Eczema | The steroid component of the combination cream had resulted in adequate clinical response at the outpatient review. The same combination cream was continued in view of the patient’s preference to continue the same combination cream rather than to purchase a new steroid-only cream. |

| 4 | High | Tinea pedis, tinea manuum, tinea cruris. Empiric topical antifungal, with instructions to consider systemic antifungal if KOH smears positive. | Negative | Xerotic eczema | Given initial high clinical suspicion, after KOH smear result was available when the patient was still hospitalised, the dermatologist advised the inpatient primary physician to continue topical antifungal treatment despite the negative KOH smear. The final diagnosis was revised on outpatient review to xerotic eczema in view of poor response to topical antifungal-only cream. The negative KOH smear result in this case was therefore initially regarded as a false negative, but with the clinical monitoring and lack of response to topical antifungal, contributed to the revision of the patient’s eventual diagnosis. |

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) of KOH smear [Table 1A and B]

Table 1.

Factors that affect the detection rate of KOH smear

| 1A) Sensitivity, specificity, PPV and NPV of KOH smear | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Dermatologist’s clinical suspicion of cutaneous fungal infection | Dermatologist’s eventual diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection after KOH smear result available (N) | Total | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Negative | Positive | Uncertain | ||||||||

| High | KOH smear result | Negative | 15 | 65 | 0 | 80 | ||||

| Positive | 0 | 149 | 0 | 149 | ||||||

| Total | 15 | 214 | 0 | 229 | ||||||

| Medium | KOH smear result | Negative | 50 | 0 | 1 | 51 | ||||

| Positive | 0 | 29 | 0 | 29 | ||||||

| Total | 50 | 29 | 1 | 80 | ||||||

| Low | KOH smear result | Negative | 48 | 1 | 1 | 50 | ||||

| Positive | 0 | 14 | 0 | 14 | ||||||

| Total | 48 | 15 | 1 | 64 | ||||||

| Total | KOH smear result | Negative | 113 | 66 | 2 | 181 | ||||

| Positive | 0 | 192 | 0 | 192 | ||||||

| Total | 113 | 258 | 2 | 373 | ||||||

| Overall sensitivity of KOH smear: 0.74 | ||||||||||

| Overall specificity of KOH smear: 1 | ||||||||||

| Overall PPV of KOH smear: 1 | ||||||||||

| Overall NPV of KOH smear: 0.62 | ||||||||||

| NPV of KOH smear in high suspicion group: 0.19 | ||||||||||

| NPV of KOH smear in medium suspicion group: 0.98 | ||||||||||

| NPV of KOH smear in low suspicion group: 0.96 | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| 1B) Logistic regression to evaluate the relationship between the individual variables and the probability of a positive KOH smear result in those who had an eventual diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Variable | P | Odds ratio (OR) | 95% confidence interval (CI) for OR | |||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Lower | Upper | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Skin sampled by dermatologically-trained personnel (yes) | 0.001 | 3.03 | 1.58 | 5.81 | ||||||

| Topical steroids used before skin sampling (yes) | 0.12 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 1.17 | ||||||

| Topical antifungals used before skin sampling (yes) | 0.24 | 0.67 | 0.35 | 1.30 | ||||||

| Systemic antifungal used before skin sampling (yes) | 0.015 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.73 | ||||||

The overall sensitivity of the KOH smear was 0.74, specificity and PPV were both 1 and NPV was 0.62. NPV was high in those with medium and low suspicion but low in those with high suspicion (Table 1A, 0.98, 0.96 and 0.19, respectively). The use of topical steroids, topical antifungals or systemic antifungals was associated with reduced odds of positive KOH smear, but only the use of systemic antifungals before collection of skin sample achieved statistical significance (OR = 0.19, 95% CI [0.05,0.73], P = 0.015). Skin sampling by a dermatologically-trained person was significantly associated with increased odds of positive KOH smear, after adjustment for use of medications before skin sampling (OR = 3.03, 95% CI [1.58,5.81], P = 0.001) [Table 1B].

Discussion

Primary objective: Whether results of KOH smear altered dermatologists’ eventual clinical diagnosis and management of patients with initially suspected superficial cutaneous fungal infection

Our findings of an overall sensitivity of 0.74 for KOH smear are similar to that previously evaluated in the detection of tinea pedis.[7] The high specificity and PPV of KOH smear in our cohort suggest that KOH smear functions best as a rule-in test to confirm cutaneous fungal infection. As a rule-out test, the NPV of KOH smear was high when utilised for cases of medium and low suspicion, but poor when there was no prior stratification of the level of clinical suspicion. This affirms the importance of clinical assessment by a dermatologically-trained clinician in making the diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infection, with a KOH smear being an adjunctive diagnostic aid.[7-9,12]

Despite the poor sensitivity and overall NPV of the KOH smear test, the KOH smear test had a high clinical utility in our cohort. The proportion of cases with uncertain diagnoses was much reduced with the aid of KOH smear results. The KOH smear result also helped to refine the specific type of cutaneous fungal infection. Additionally, the majority of those who were eventually recommended dual topical and systemic antifungals had a positive KOH smear, suggesting that the positive result lent confidence to the dermatologist to initiate necessary systemic treatment for those whose disease severity met the clinical indication.

Secondary objective: Whether other factors influence the detection rate of KOH smear

In our cohort, the use of systemic antifungals before skin sampling significantly reduced the detection rate of KOH smear. Inferring from this, should a patient be considered for systemic antifungal treatment for suspected cutaneous fungal infection? It may be prudent to perform a KOH smear first if none was done previously or if the previous result was negative, even if the patient has received pre-treatment with topical steroids or antifungals.

Our cohort also observed a significantly increased detection rate of KOH smear when performed by dermatologically trained persons. This underscores the importance of adequate training and suggests that focused training of non-dermatologically-trained clinicians on proper sample collection may improve the detection rate of KOH smear.

Limitations

As a retrospective study, errors in medical documentation could have resulted in a wrong interpretation of the dermatologist’s initial impressions. The lack of a gold standard test that is independent of a clinician’s assessment also makes the sensitivity assessment of KOH smear inherently flawed. However, by analysing retrospectively with an additional buffer of 2 months post-discharge, our study uniquely reduces the element of subjectivity in determining the patient’s ultimate diagnosis, as dermatologists would have had the benefit of observing the patient’s response to management before concluding their eventual diagnosis.

A second limitation is the varying experience of personnel sampling the skin for KOH smear. Our study assumed that anyone outside of the contemporaneous dermatology team had limited dermatological experience, and contrarywise to a junior doctor in the dermatology team who may have only recently joined but would be closely supervised by a permanent staff of the dermatology service. Should this be significantly untrue? the number of false negative results could have been skewed either way. Nonetheless, this study provides a snapshot of the diagnostic accuracy of the KOH smear test in the real-world setting in a tertiary teaching hospital.

Third, to optimise the pre-test probability, our study included and stratified patients based on a dermatologist’s initial clinical impression, rather than that of a non-dermatologically-trained doctor. Hence, the results of this study highlight the utility of the KOH smear to a dermatologist and are not generalisable to a non-dermatologically-trained clinician.

External validity

The sensitivity of the KOH smear determined in our study is similar to that reported by Levitt et al.[7] via pooled analysis of the sensitivity of KOH smear in tinea pedis from clinical trials, although our specificity, PPV and NPV are considerably higher (PPV 1 vs 0.7, NPV 0.62 vs 0.47, respectively). The main differences that resulted in differences in specificity, PPV and NPV between our study and Levitt et al.,[7] are that our study was conducted in a real-world setting where the threshold to treat a potential false positive or negative result with topical antifungals is low.[13]

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates how the KOH smear can be a useful tool in the armamentarium of a dermatologist. Caution in the interpretation of KOH smear should be exercised when the collection of skin samples is compromised by prior use of systemic antifungal or questionable technique. Selected training of non-dermatologically-trained clinicians in proper KOH smear sample collection techniques may potentially improve the detection rate of the test.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Comparison of the dermatologist's initial and eventual diagnosis of the specific type of cutaneous fungal infection before and after KOH smear result in the high suspicion group

References

- 1.Tan HH. Superficial fungal infections seen at the National Skin Centre, Singapore. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2005;46:77–80. doi: 10.3314/jjmm.46.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solovastru L. [Examenul micologic direct in micozele cutanate superficiale. Direct mycologic examination in superficial cutaneous mycoses. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2003;107:921–4. Romanian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saunte DML, Piraccini BM, Sergeev AY, Prohić A, Sigurgeirsson B, Rodríguez-Cerdeira C, et al. A survey among dermatologists: Diagnostics of superficial fungal infections-What is used and what is needed to initiate therapy and assess efficacy? J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:421–7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Panthagani AP, Tidman MJ. Diagnosis directs treatment in fungal infections of the skin. Practitioner. 2015;259:25–9, 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guzman AK, Kaffenberger BH. Office-based dermatologic diagnostic procedure utilization in the United States Medicare population from 2000-2016. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:1317–22. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murphy EC, Friedman AJ. Use of in-office preparations by dermatologists for the diagnosis of cutaneous fungal infections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:798–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levitt JO, Levitt BH, Akhavan A, Yanofsky H. The sensitivity and specificity of potassium hydroxide smear and fungal culture relative to clinical assessment in the evaluation of tinea pedis: A pooled analysis. Dermatol Res Pract. 2010;2010:764843. doi: 10.1155/2010/764843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karimzadegan-Nia M, Mir-Amin-Mohammadi A, Bouzari N, Firooz A. Comparison of direct smear, culture and histology for the diagnosis of onychomycosis. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48:18–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2007.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu L, Zhou P, Zhao W, Hua H, Yan Z. Fluorescence staining vs. routine KOH smear for rapid diagnosis of oral candidiasis-A diagnostic test. Oral Dis. 2020;26:941–7. doi: 10.1111/odi.13293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yadgar RJ, Bhatia N, Friedman A. Cutaneous fungal infections are commonly misdiagnosed: A survey-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:562–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pariser RJ, Pariser DM. Primary care physicians'errors in handling cutaneous disorders. A prospective survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:239–45. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70198-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Karaman BF, Topal SG, Aksungur VL, Ünal İ, İlkit M. Successive potassium hydroxide testing for improved diagnosis of tinea pedis. Cutis. 2017;100:110–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ecemis T, Degerli K, Aktas E, Teker A, Ozbakkaloglu B. The necessity of culture for the diagnosis of tinea pedis. Am J Med Sci. 2006;331:88–90. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200602000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Comparison of the dermatologist's initial and eventual diagnosis of the specific type of cutaneous fungal infection before and after KOH smear result in the high suspicion group