Abstract

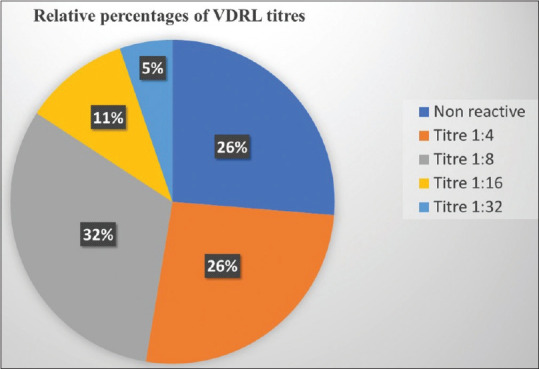

The non-treponemal tests like VDRL and RPR hold an important place in the diagnosis of syphilis. In many countries, these tests are used for screening, with positive results being subsequently confirmed by treponemal or specific tests like TPHA or FTA-ABS. Recent observations of low-titer VDRL or RPR positivity (<1:8) or negative results in patients with clinically active syphilis are becoming a cause for concern especially in the backdrop of a resurgence of the disease. Such a scenario might undermine the usefulness of VDRL or RPR as effective screening test and for treatment monitoring. We studied the titers of non-treponemal serological test (VDRL) in non-HIV-positive, untreated cases of secondary syphilis (diagnosed clinically and confirmed serologically with specific treponemal tests like TPHA or FTA-ABS). It was an OPD-based cross-sectional study, which included patients presenting with muco-cutaneous lesions suggestive of secondary syphilis, confirmed serologically with positive specific treponemal tests, who were seronegative for HIV1 and 2 and had not received treatment with injectable benzathine penicillin. Their VDRL titers were noted. Information regarding duration of lesions and any previous genital ulcer was obtained, and additional information was sought regarding any medications taken during the last two months. Nineteen patients (12 males, 4 females, and 3 transgender individuals) between the ages of 18 and 46 years were included in the study. Ten of these cases (52.63%) had a VDRL titer of less than 1:8 (non-reactive in 5 patients, titer of 1:4 in 5 patients). Among the remaining nine cases, a titer of 1:8 was observed in six, 1: 16 in two, and 1:32 in one case. Our observations raise concerns regarding the possibility that a significant number of patients with active syphilis and potential to transmit the disease are being left untreated because of low or negative titers in the screening tests. This may account for the slow resurgence of syphilis as documented by increase in case rates and incidence of congenital syphilis in different parts of the world.

KEY WORDS: Secondary syphilis, treponemal tests, VDRL titer

Introduction

Syphilis, the oldest known sexually transmitted disease, has been justifiably awarded the epithet of “the great imitator” because of its protean manifestations. The varying presentations of the disease, which depend on the clinical stage, interspersed with phases of latency when the patient may be free of any signs and symptoms, often make this condition difficult to diagnose. Diagnosis rests on demonstration of treponemes under dark field microscope or serological tests, which may be specific or nonspecific. Besides being difficult to perform, dark ground microscopy is useless in chancres which are healing, oral syphilitic lesions, and dry cutaneous lesions of secondary syphilis (SS). Hence, in most cases, serological tests form the cornerstone for diagnosis. In many countries, including India, the venereal disease research laboratory test (VDRL) or rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests which are the nontreponemal tests for syphilis are used for screening followed by more specific tests like Treponema Pallidum Hemagglutination Assay (TPHA) and Fluorescent Treponemal Antibody Absorption (FTA-ABS) for confirmation of a positive report.[1,2] Generally a titer of 1:8 or higher is considered to determine a positive reaction. In recent years, concerns have been voiced that a number of patients with syphilis are presenting with titers less than 1:8 and hence are remaining undiagnosed and untreated. This scenario is a cause of worry, more so in the backdrop of resurgence of syphilis, which is being observed the world over. Most of the studies in this respect are laboratory based, where TPHA or TPPA positivity has been demonstrated in sera non-reactive or low-reactive for VDRL or RPR, the so-called phenomenon of “serological discordance”. The fallacy of these studies lies in the fact that previous treatment for syphilis and early or late stage of the disease also demonstrate this serological profile. Keeping this background in mind we report our OPD-based experience, where the serological findings of a series of previously untreated patients presenting with SS are presented.

Aims and Objectives: We studied the titers of non-treponemal serological test (VDRL) in non-HIV-positive, untreated cases of SS (diagnosed clinically and confirmed serologically with specific treponemal tests (TPHA or FTA-ABS).

Materials and Methods

All consecutive patients with lesions suggestive of SS presenting in the Dermatology and STD OPD of two tertiary care hospitals in Kolkata (KPC Medical College and Hospital and JIMS Medical College and Hospital) in a period of one year (1st December 2022 to 30 November 2023) were evaluated. History regarding previous treatment with benzathine penicillin injection was obtained and both non-treponemal (VDRL) and treponemal (TPHA or FTA-ABS) tests were performed for confirmation of diagnosis along with serology for HIV 1 and 2. Patients who had already received injection penicillin, those who had a negative TPHA or FTA-ABS serology and those testing positive for HIV-1 and 2 were excluded from the study. This study didn’t include patients presenting with primary, latent, or tertiary syphilis, or those with isolated reactive treponemal and non-treponemal tests without any mucocutaneous lesions. Thus, only HIV seronegative and treatment naive cases of secondary syphilis were included in this OPD-based cross-sectional study.

Information regarding duration of lesions and any previous genital ulcer was obtained and additional details were sought regarding medications taken during the last two months or for the treatment of genital symptoms. Appropriate informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Results

In a period of one year, twenty-two patients presented with serologically confirmed untreated SS in the Dermatology and STD OPD of the two hospitals. Of these, three patients had positive HIV serology and were excluded. Thus, nineteen non-HIV-positive patients with untreated SS (twelve males, four females, and three transgender individuals) were included in the study. One female patient had been referred from the antenatal clinic while the others attended the OPD on their own. Their ages varied from 18 to 46 years. Most of the patients presented with macular lesions on palms and soles or a generalized maculo-papular rash [Figures 1 and 2]. Condyloma lata was seen in four cases while only eleven recalled a history of ulcer [Figure 3].

Figure 1.

Predominantly papular lesions of secondary syphilis on trunk with macular eruptions on palms

Figure 2.

Macular lesions of secondary syphilis limited to palms and soles

Figure 3.

Condyloma Lata over vulva

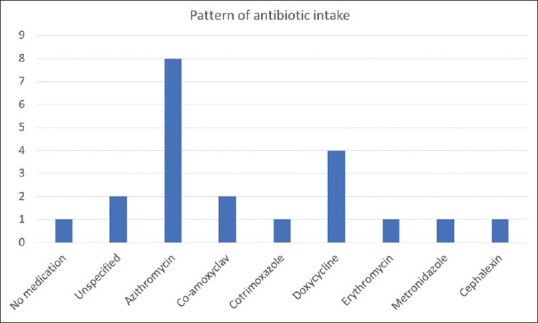

Significantly, ten of these nineteen cases (52.63%) had a VDRL titer of less than 1:8 of which five were non-reactive even after exclusion of prozone phenomenon, while the other five reported a titer of 1:4. Among the remaining nine cases a titer of 1:8 was observed in six (31.57%), 1:16 in two (10.52%) and 1:32 in one (5.26%) [Figure 4]. All the patients were reactive with TPHA/FTA-ABS and were subsequently treated with the recommended dose of benzathine penicillin, leading to resolution of clinical lesions. Interestingly, sixteen of the patients had a history of prior intake of antibiotics (azithromycin, doxycycline, co-trimoxazole, erythromycin, amoxycillin + clavulanate, cephalosporin, and metronidazole) in the last two months, while three others could not specify the medications taken [Figure 5]. The details of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Relative proportions of VDRL titers observed among the study patients (N = 19)

Figure 5.

Pattern of antibiotic usage among the study patients (N = 18, Two patients had received more than one class of antibiotic)

Table 1.

Clinical and serological characteristics and history of drug intake among the patients

| Age (in years) | Sex | Clinical lesions | History of prior ulcer | VDRL titer | Prior medication taken | Specific test done |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | M | Generalized Macular rash, Inguinal Lymphadenopathy, Condyloma lata | Not recalled | Non-reactive | Azithromycin (1 gram as single dose) | TPHA positive |

| 19 | M | Macular lesions on palms and soles | 5 weeks back | 1:8 | Doxycycline 100 mg OD for 2 weeks | TPHA positive |

| 20 | M | Generalized Maculopapular rash | Not recalled | 1:4 | Erythromycin (dose not specified) | TPHA positive |

| 30 | T | Healed ulcer, Macular Lesions on palms | 4 weeks back | Non-reactive | Azithromycin 500 mg once a day for <1 week | TPHA positive |

| 22 | F | Macular lesions on palms and soles | Not recalled | 1:16 | Could not specify | TPHA positive |

| 32 | T | Generalized Macular rash, Condyloma lata (perianal) | 2 months back | 1:4 | Azithromycin 500 mg OD or BD irregularly | TPHA positive |

| 27 | T | Macular lesions on palms and soles | Not recalled | Non-reactive | Doxycycline 100 mg OD for 3 weeks | TPHA positive |

| 28 | M | Condyloma lata, Mucosal patches (oral) | Present but time not specified | 1:32 | Nil | TPHA positive |

| 29 | M | Macular Lesions on palms and soles, Lymphadenopathy (cervical, epitrochlear) | Not recalled | 1:4 | Coamoxyclav Could not specify dose | TPHA positive |

| 21 | M | Macular Lesions on palms and soles. Generalized maculopapular rash | 4 weeks back | 1:8 | Cephalexin 500 twice for 7-10 days | TPHA positive |

| 26 | F | Macular Lesions on palms and soles (Antenatal) | Present for last 2 weeks | 1:8 | Azithromycin + unspecified drug Dose not known | TPHA positive |

| 30 | M | Erythematous macules on palms and soles | 3 weeks back | 1:4 | Azithromycin 1 g once and repeated after a week | TPHA positive |

| 36 | M | Macular Lesions on palms and soles | Not recalled | 1:8 | Doxycycline Dose not specified | TPHA positive |

| 24 | F | Condyloma lata (vulval) Inguinal Lymphadenopathy, Macular lesion on palms | Not recalled | 1:8 | Coamoxyclav 625 + metronicazole 400 mg BD for 7 days | FTA-ABS positive |

| 18 | M | Macular Lesions on palms and soles | >6 weeks | 1:4 | Doxycycline 100 mg irregularly for 4 weeks (for acne) | TPHA positive |

| 29 | F | Generalized maculopapular rash with lesions on palms and soles | Around 8 weeks back | Non-reactive | Azithromycin Dose unspecified | TPHA positive |

| 38 | M | Macular lesions on palms Healed penile ulcer | 2 weeks back | 1:16 | Cotrimoxazole (dose unspecified) + Azithromycin 250 mg twice for 5 days | TPHA positive |

| 46 | M | Macular palmoplantar rash, Mucous patches | 1 month back | Non-reactive | Could not specify | TPHA positive |

| 20 | M | Generalized maculopapular rash, Lymphadenopathy (inguinal and cervical) | Not recalled | 1:8 | Azithromycin 500 mg once a day for 6 days | TPHA positive |

Discussion

The diagnosis of syphilis is based on serology in nearly all cases. The non-treponemal tests for syphilis (VDRL and RPR) serve the dual function of initial screening and case detection, as well as monitoring of response to treatment. Their main disadvantage stems from the chances of biological false positive reaction, hence, a minimum cut-off of 1:8 is usually considered to label a positive titer. Raising this cutoff increases the specificity but lowers the sensitivity and vice versa. The sensitivity of a non-treponemal test also depends on the stage of syphilis, varying from approximately 78% during the primary stage to nearly 100% during the secondary, then dropping to 71% during the tertiary stage.[3]

The recent trend of increasing case rates and incidence of congenital syphilis from all over the world points to the fact that the disease is showing a slow but definite resurgence.[4] With this background, it is of great concern that several patients with active disease are presenting with titers less than the commonly accepted cut-off of 1:8. Based on the findings of VDRL alone these patients would be stamped as non-positives without undergoing any further confirmatory testing or treatment. The fact that HIV-positive individuals may have low VDRL titers has been recognized for a long time.[5] We however were surprised to find negative (<1:8) VDRL reports in almost half of our patients with untreated SS none of whom were HIV-positive. Interestingly, the low titers in these patients at presentation could not be attributed to the duration or stage of their disease as all the patients were clinically in the secondary stage when titers of both non-specific and specific treponemal antibodies are at their highest. It is unlikely that titers in these patients would have risen further in future. All our cases presented with muco-cutaneous lesions suggestive of SS, had positive specific treponemal tests (TPHA/FTA-ABS) and the lesions resolved clinically after treatment with benzathine penicillin thus confirming the diagnosis. The cases where VDRL was non-reactive or positive in very low titers could be monitored only clinically with no significant changes observed on serology. The magnitude of similar “serologically negative, clinically active” cases in community is unknown, and our study might have revealed just the tip of the iceberg.

Till date, there has been no study exploring this problem from the clinical perspective although a few studies exist, which have tried to explore this problem from the serological aspect. One such study by Gupta et al.[6] reports sixteen (40%) samples as TPHA-positive among forty samples showing low-titer (<1:8) VDRL positivity. In a hospital based study Kashyap et al.[7] reported that a staggering 100 of 173 (57.8%) VDRL reactive sera showed a low titer (<1:8) of which 55% turned out to be TPHA positive. Earlier, a similar finding had been described by Bala et al.[8] where 68 out of 80 VDRL positive sera demonstrated a titer of less than 1:8 and TPHA positivity was observed in 59 out of 68 samples. All these studies suffer from the lack of clinical data regarding the stage of the disease, history of treatment, or any concomitant HIV seropositivity. As specific treponemal tests remain positive forever while VDRL titers decrease after adequate treatment of syphilis, a serological discordance showing low or non-reactive VDRL with a positive TPHA test is expected in treated cases of syphilis. Also, VDRL titers may be low or undetectable in early or later stages of the disease. As such, it is difficult to extrapolate these purely serological data to practical clinical scenario.

In our study, we excluded HIV-positive patients and patients with primary, tertiary, or latent stages of syphilis to avoid the confounding effects of HIV co-infection and stage or duration of disease on non-treponemal test titers. Yet we are unable to explain the cause underlying the low or negative titers in our patients with SS. Whether it reflects a change in virulence or immunogenicity of the organism is a matter of conjecture.

Interestingly, we found a history of oral antibiotic intake in sixteen out of our nineteen patients. One had been treated with azithromycin and one with doxycycline for their previous ulcer, while others had taken it on their own or for unrelated infections. Azithromycin, erythromycin, doxycycline, and amoxycillin are known to act against Treponema pallidum.[9,10,11] Azithromycin in doses of 2 g or 1 g (single dose) or 500 mg daily for 10 days[9] and doxycycline 100 mg twice in a day for 15 to 30 days have been studied to be effective.[10] Amoxycillin (500 mg thrice in a

day as monotherapy or in combination with probenecid) has also been shown to be effective and is part of certain guidelines.[11] In our country, it is not unusual to find that patients have consumed these medications in comparable doses, albeit sometimes for totally unrelated conditions, especially as antibiotics are one of the commonest prescribed class of drugs and are also easily available over the counter without prescriptions. Hence, we hypothesize that the intake of such antibiotics may leave patients with syphilis partially treated, unable to halt subsequent progression of the disease but leading to a low level of immune response. The rampant use of antibiotics in our country can lead to a significant magnitude of such patients.

In the light of our observation, clinicians need to develop a high index of clinical suspicion for syphilis and interpret a low-titer VDRL positivity with caution, further testing these cases with specific treponemal tests, especially in background of a high pre-test probability.

Conclusion

Cases of syphilis remaining untreated due to inadequate serological evidence would increase the case load in the population with resultant increase in transmission of the disease. This might contribute to the resurgence of syphilis that we are witnessing. To shed light on the magnitude and implications of the problem, larger studies exploring the problem from a clinical standpoint are the need of the hour.

Limitations

Possibility of recall bias cannot be excluded. Being a descriptive cross-sectional study without a control group, formal sample size estimation was not done. A future well-controlled study with a proper sample size will certainly add more value to these findings.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Sexually Transmitted Infection Treatment Guidelines 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Syphilis; Laboratory Manual for Diagnosis of Sexually Transmitted and Reproductive Tract Infections: National AIDS Control Organisation; Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Government of India 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantor A, Nelson HD, Daeges M, Pappas M. Screening for Syphilis in Nonpregnant Adolescents and Adults: Systematic Review to Update the 2004 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2016. Report No.: 14-05213-EF-1. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK368468/table/ch1.t3/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moseley P, Bamford A, Eisen S, Lyall H, Kingston M, Thorne C, et al. Resurgence of congenital syphilis: New strategies against an old foe. Lancet Infect Dis. 2024;24:e24–35. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(23)00314-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sharma S, Chaudhary J, Hans C. VDRL v/s TPHA for diagnosis of syphilis among HIV sero-reactive patients in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2014;3:726–30. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gupta K, Bhardwaj A, Dash S, Kaur IR. Role of Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay for diagnosis of syphilis in low titers of VDRL-reactive sera: A prospective study from a large tertiary care center of East Delhi. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7:1594–5. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_258_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kashyap B, Goyal N, Gupta N, Singh N P, Kumar V. Evaluation of Treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay among varying titers of the venereal disease research laboratory test. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:479–83. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_595_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bala M, Toor A, Malhotra M, Kakran M, Muralidhar S, Ramesh V. Evaluation of the usefulness of Treponema pallidum hemagglutination test in the diagnosis of syphilis in weak reactive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory sera. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2012;33:102–6. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.102117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quirk M. Oral azithromycin for syphilis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:676. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dai T, Qu R, Liu J, Zhou P, Wang Q. Efficacy of doxycycline in the treatment of syphilis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61:e01092–16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01092-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ando N, Mizushima D, Omata K, Nemoto T, Inamura N, Hiramoto S, Takano M, Aoki T, Watanabe K, Uemura H, Shiojiri D. Combination of amoxicillin 3000 mg and probenecid versus 1500 mg amoxicillin monotherapy for treating syphilis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus: An open-label, randomized, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;77:779–87. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciad278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]