Abstract

Introduction:

Deep mycoses acquired by penetrating trauma to the skin can have varied and sometimes atypical morphological presentations resulting in diagnostic dilemmas and delay in treatment onset. Histopathology can be a useful tool in not only diagnosing but also differentiating various deep mycoses.

Aims and Objectives:

To observe various morphological presentations and histopathological features of deep fungal infections.

Materials and Methods:

A retrospective multi-centric study was conducted from 2010 to 2020 at 16 centres. The cases with diagnoses of various deep mycoses were included in the study. The patients presenting with cutaneous manifestations were included in the study. Their demographic details, history, presenting signs and symptoms, morphological presentations, histopathological features and treatment details were collected from the case sheets.

Results:

A total of 124 cases were found from the case records. The most common type was chromoblastomycosis (42) followed by mycetoma (28) and rhinosporidiosis (17). The mean age was 43.76 ± 5.44 years. The average duration of symptoms before presentation was between 2 months to 10 years (average 2.5 ± 1.33 years). Male to female ratio was 1:0.7. Prior history of trauma was recorded in 36% of cases. Chromoblastomycosis cases presented with verrucous to atrophic plaques with black dots on the surface and histopathology findings included pesudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, epithelioid cell granulomas, copper penny bodies within granulomas and abscesses. Rhinosporidiosis cases had polypoid grape-like lesions in the nose and eyes most commonly with histopathology findings of abundant thick-walled sporangia in dermis packed with thousands of spores. Eumycetoma patients had pigmented, indurated swelling with multiple sinuses discharging black granules and histopathology showed dermal abscesses and foreign body granulomatous reaction with PAS-positive hyphae. Histoplasmosis patients presented with few to multiple nodulo-pustular lesions on skin and palatal ulcers while small basophilic bodies packed in the cytoplasm of histiocytes were noted in histopathology. Phaeohyphomycosis cases presented as deep-seated cystic lesions and biopsy revealed deepithelialized cysts in the dermis or hypodermis with lumen showing necro inflammatory debris and fungal hyphae. Sporotrichosis cases had erythematous, tender nodules and papules either as single lesions or as multiple lesions arranged in a linear fashion and histopathology showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of epidermis, loose to well-defined epithelioid cell granulomas and microabscesses. Spores were found in two cases. Cryptococcosis patient had multiple umbilicated lesions resembling giant molluscum contagiosum loose epithelioid cell granulomas and medium-sized spores lying in both intra and extracellularly on histopathology. Penicilliosis patients had nodulo-pustular lesions and histopathology showed an admixture of histiocytes, epithelioid cells, plasma cells, lymphocytes and polymorphs in the dermis with the presence of yeast-like spores in the cytoplasm of histiocytes and epithelioid cells. Entomophthoromycosis cases presented with asymptomatic subcutaneous firm swelling with loss of skin pinchability.

Conclusion:

Though clinical findings of deep fungal infections are characteristic similar morphology and atypical presentations can be sometimes confusing. Histopathology is useful for confirming the diagnosis.

KEY WORDS: Clinical presentation, deep mycoses, histopathology, morphologies

Background

Deep mycoses, though not common, are encountered frequently in hot and humid climates of tropics and subtropics, specifically in the north-eastern parts of India.[1] The deep fungal infections encountered include chromoblastomycosis, sporotrichosis, rhinosporidiosis, myecetoma, histoplasmosis, subcutaneous pheohyphomycosis, mucormycosis hyalohyphomycosis, entomophthoromycosis, penicilliosis and cryptococcosis. They often cause prolonged morbidity. These can present to the dermatologist with variable presentations such as nodulo-pustular lesions, cysts, indurated masses with surface changes such as discharging sinuses or verrucosity and ulcers. The variable clinical presentation can pose diagnostic challenges.[1,2] Many cases of deep mycosis are often misdiagnosed or diagnosed late which can lead to several local and systemic complications. Deep mycosis like mycetoma can invade deeply and involve the underlying bones leading to irreversible bony deformity and disability. By the time the patient is diagnosed with deep mycosis, the complications caused are usually irreversible. Hence there is always a need for early diagnosis and treatment.[1,2] There are very few studies describing the clinico-histopathological features of deep mycoses from the Indian subcontinent. In the present study, we have emphasised the importance of morphological presentations and subtle histopathologic features in diagnosing deep mycosis.

This retrospective cross-sectional study was devised to observe the various morphological presentations and histopathological features of the cases of deep mycoses presented to various centres across India.

Aim and Objective

To observe various morphological presentations and histopathological features of deep fungal infections.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective descriptive cross-sectional type data study was conducted from 2010 to 2020 at multiple Centres in Kolkata, Patna, Agartala, Midnapore, Prayagraj, Bengaluru and Mizoram.

The cases with the diagnosis of various deep mycoses presenting with cutaneous manifestation were included in the study. Their demographic details, history, presenting signs and symptoms, morphological presentation, histopathological features and treatment details were collected from the case sheets. A total of 124 patients of deep mycoses over a period of 10 years period were included in the study. The data were analysed using SPSS. Simple statistics were used to analyse data. The mean with standard deviation was calculated for numerical data and the percentage was calculated for descriptive variables.

Results

A total of 124 cases were found from the case records. Out of them, 42 of chromoblastomycosis, 28 mycetoma, 17 rhinosporidiosis, 10 of histoplasmosis, 10 of phaeohyphomycosis, 8 of sporotrichosis, 4 cases of hyalohyphomycosis, 1 cryptococcosis, 2 penicilliosis and 2 entomophthoromycosis cases were encountered [Table 1]. The age ranged from 16 to 65 years, average 43.76 ± 5.44 years. The average duration of symptoms before presentation was between 2 months to 10 years (average 2.5 ± 1.33 years). The majority of our patients were male (94/124, 75.8%). Prior history of trauma was recorded in 45 patients (45/124, 36.3%). The lower limb was the most common site of involvement (67%). Only two patients had immunosuppression in the form of HIV infection.

Table 1.

The various types of deep mycoses encountered in our study

| Type of deep mycoses | No of cases |

|---|---|

| Chromomycosis | 42 |

| Rhinosporidiosis | 17 |

| Mycetoma | 28 |

| Histoplasmosis | 10 |

| Phaeohyphomycosis | 10 |

| Sporotrichosis | 8 |

| Hyalohyphomycosis | 4 |

| Cryptococcosis | 1 |

| Penicilliosis | 2 |

| Entomophthoromycosis | 2 |

Morphological presentations

The commonest morphological presentations of chromoblastomycosis were verrucous plaques in the lower extremities followed by atrophic plaque lesions on the upper and lower extremities. Plaque lesions on the face were the third common manifestation, especially in patients of the north-eastern hilly regions of India. Two cases (2/42, 4.8%) presented as ulcers, one on the forearm and one on the lower leg. Blackish granular pigmentation was present on the surface in the case of most verrucous lesions as well as in the case of ulcers of the forearm. However, such pigment was absent in the case of an ulcer on the leg [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

A case of chromoblastomycosis showing an ulcer over the lower leg

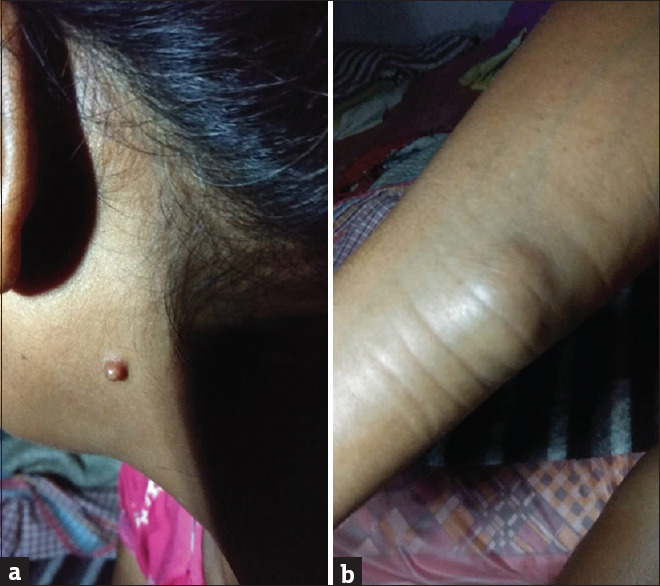

Rhinosporidiosis cases presented as polypoid grape-like lesions in the nose and eyes most commonly. In one (1/17, 5.9%) case, there were disseminated lesions on various parts of the body. These lesions were multiple skin-coloured, sessile or pedunculated papulo-nodular lesions [Figure 2a and b].

Figure 2.

(a) Disseminated lesions of rhinosporidiosis on various parts of the body-pedunculated lesion behind the ear (b) Disseminated lesions of rhinosporidiosis on various parts of the body-subcutaneous nodule on the arm (same patient)

Eumycetoma presented as firm swelling with discharging sinuses, with discharge of black granules [Figure 3]. The swelling was woody and hard pigmented with multiple solid papules beneath the swelling which would rupture on the surface with a small opening, discharging black-coloured granules. The swellings were painless to start with and in due course of time few patients complained of intermittent bony pain. In 33.3% of cases of eumycetoma, the radiological findings showed osteosclerotic and osteolytic lesions.

Figure 3.

Eumycetoma presenting as firm swelling with sinuses discharging black granules over the dorsal and plantar aspect of the foot

Patients with histoplasmosis presented with low-grade fever, weakness, dry cough and few to multiple nodulo-pustular lesions on the skin [Figure 4]. Two patients had presented with palatal ulcers.

Figure 4.

Histoplasmosis presenting with multiple nodulo-pustular lesions on skin

Firm, mobile, deep-seated cystic lesions with minimal surface change were the common presentation for phaeohyphomycosis. Most lesions are presented on the lower extremity [Figure 5]. One had presented on the back of the trunk.

Figure 5.

Deep-seated cyst of phaeohyphomycosis on the lateral aspect of the dorsum of the foot

Sporotrichosis cases presented with erythematous, tender nodules, plaques and papules either as single lesions or as multiple lesions arranged in a linear fashion [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

Sporotrichosis presented as linear erythematous, nodules, plaques and papules over the lateral aspect of the trunk

The cases of hyalohyphomycosis presented as deep-seated swelling or abscesses. In two cases, cysts were observed on the cut section.

The case of cryptococcosis had presented as multiple umbilicated lesions resembling giant molluscum contagiosum [Figure 7].

Figure 7.

Cryptococcosis with multiple umbilicated lesions resembling giant molluscum contagiosum

The two cases of penicilliosis had HIV infection. One patient had umbilicated nodulo-pustular lesions on the body. The other had small nodular lesions on the body [Figure 8].

Figure 8.

Umbilicated nodulo-pustular lesions of penicilliosis on the body

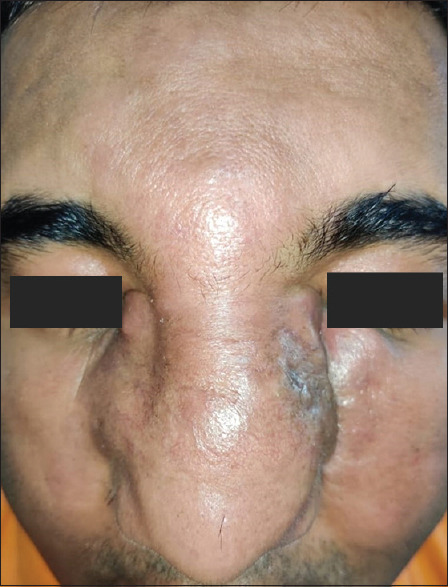

Of the two cases of entomophthoromycosis, one presented with asymptomatic subcutaneous firm swelling which was removed as a tumour from below the chest wall and another presented as a thickened plate-like subcutaneous swelling on the face with loss of skin pinchability on the surface [Figure 9].

Figure 9.

Thickened plate-like subcutaneous swelling on the face with loss of skin pinchability on the surface of entomopthoromycosis

Histopathological findings

All cases of chromoblastomycosis showed pesudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with loose epithelioid cell granulomas admixed with neutrophilic abscesses, plasma cells, eosinophils, histiocytes and lymphocytes in the dermis. Thick-walled brownish fungal spores referred to as copper penny bodies were found within granulomas, microabscesses and within the cytoplasm of foreign body giant cells. In most (75%) cases the spores were identified on routine haematoxylin and eosin (H and E) satin alone but in (25%) cases where the fungal load was low or when the diagnosis was not suspected clinically due to atypical presentation, a periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain proved useful in identifying the spores [Figure 10].

Figure 10.

Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain showing the thick-walled spores of chromoblastomycosis. (H and E ×400)

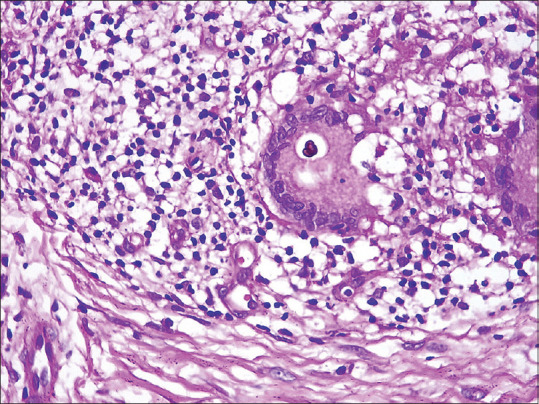

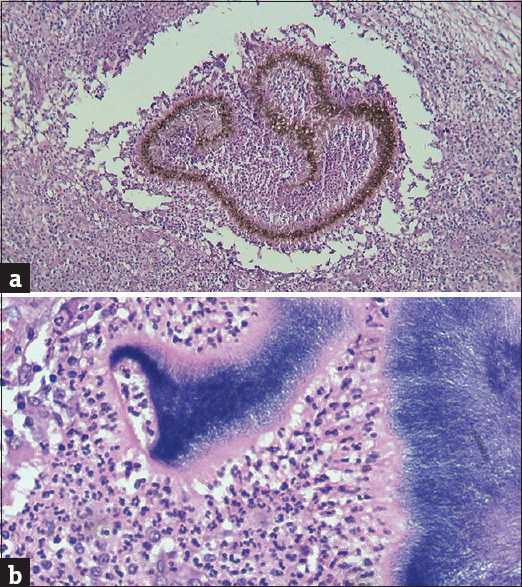

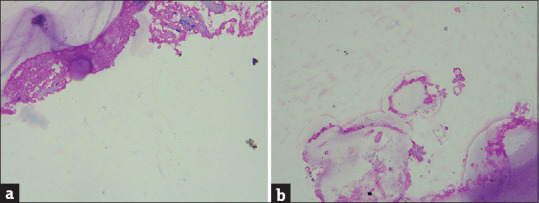

Rhinosporidiosis cases had abundant thick-walled sporangia lying in the dermis which were in turn packed with thousands of spores. The granulomatous reaction was present focally around the sporangia [Figure 11].

Figure 11.

(H and E x100): Showing abundant thick-walled sporangia lying in the dermis which are in turn packed with thousands of spores of rhinosporidiosis

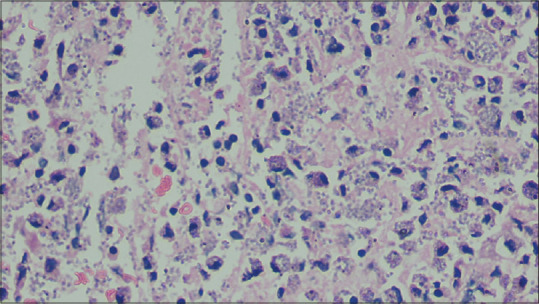

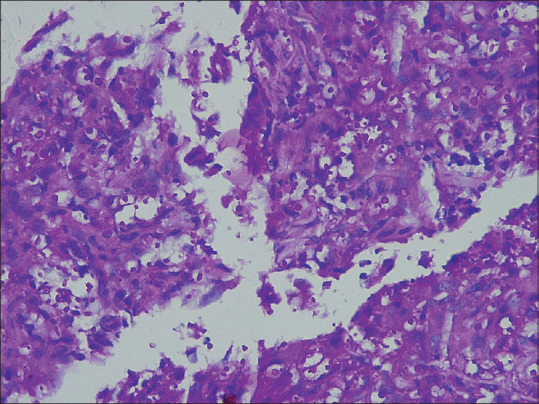

In all cases of eumycetoma, dermal abscesses and foreign-body granulomatous reactions were noted. These cases were subjected to special stains, namely, Gram’s, PAS and Gomori methanamine silver (GMS) stains. In eumycetoma, the fungal grains could be identified due to the presence of brown-coloured fungal hyphae which were broader than the bacterial filaments of actinomycetoma [Figure 12a and b]. In histoplasmosis, small basophilic bodies were noted packed in the cytoplasm of histiocytes. The infiltrate in the dermis ranged from sheets of histiocytes with the exclusion of most other inflammatory cells to loose ill-defined granulomas along with chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate like plasma cells, lymphocytes and eosinophils [Figure 13].

Figure 12.

(a) (H and E x100): Eumycotic fungal hyphae are identified easily here due to their brown pigment (b) (H and E x400): Basophilic bacterial filaments in a case of Actinomycetoma

Figure 13.

(H and E x1000): Round basophilic bodies of histoplasmosis present intracellularly within macrophages and extracellularly within the dermal interstitium

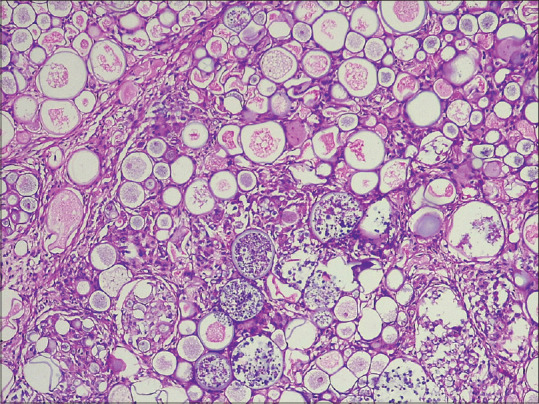

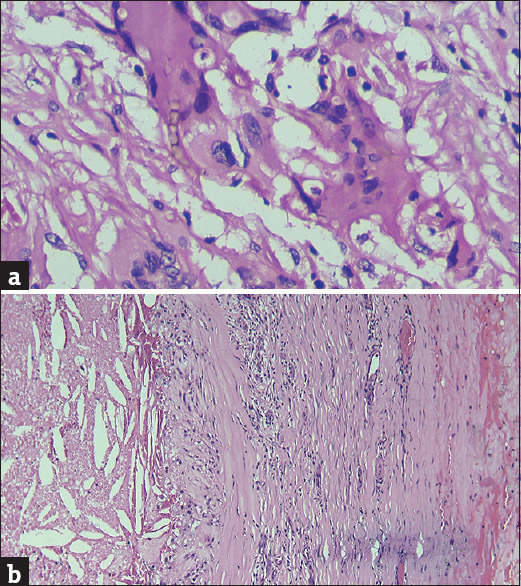

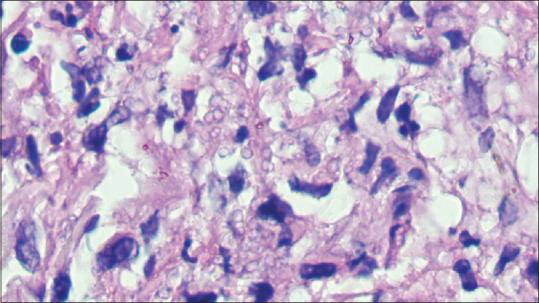

All cases of phaeohyphomycosis showed deep-seated deepithelialized cysts in the dermis or hypodermis. The cyst wall was largely fibrocollagenous and showed tuberculoid epithelioid cell granulomas along with mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate. Most cases showed cholesterol clefts in the wall. The cyst lumen showed necroinflammatory debris and fungal hyphae could be identified both within the cyst lumen as well as in the tissue of the cyst wall [Figure 14a and b].

Figure 14.

(a) (H and E x400): Brown-coloured septate and branched fungal hyphae present within cytoplasm of a giant cell (b) (H and E x100): Fibrocollagenous cyst wall of phaeohyphomycosis showing cholesterol clefts

Sporotrichosis cases showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis. The dermis showed oedema, loose to well-defined epithelioid cell granulomas and microabscesses. Typical pink asteroid bodies could not be found in any case, however, few acellular hyalinised structures with irregular spikes on the outer aspect were found. A cluster of PAS-positive fungal spores could be found in two cases [Figure 15]. A good clinicopathological correlation was the mainstay for diagnosis.

Figure 15.

PAS-positive spores of sporotrichosis in clusters as well as lying discretely. (H and E ×200)

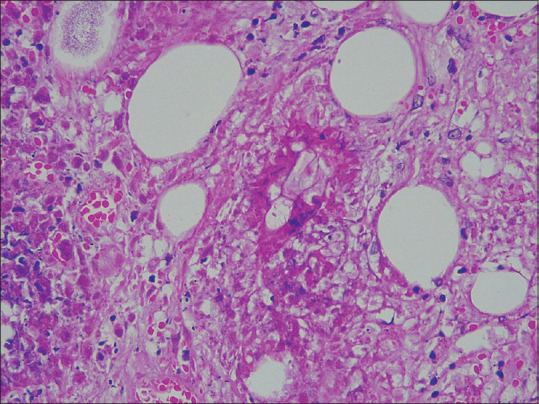

Hyalohyphomycosis cases showed cyst formations similar to phaeohyphomycosis and/or granuloma and abscess formations in the deep dermis and subcutaneous fat along with giant cells. The hyaline septate hyphae were found within cysts and abscesses [Figure 16a and b].

Figure 16.

(a) (H and E x100): Cyst lumen showing numerous hyaline hyphae of hyalohyphomycosis (b) (H and E x400): High power view of the same

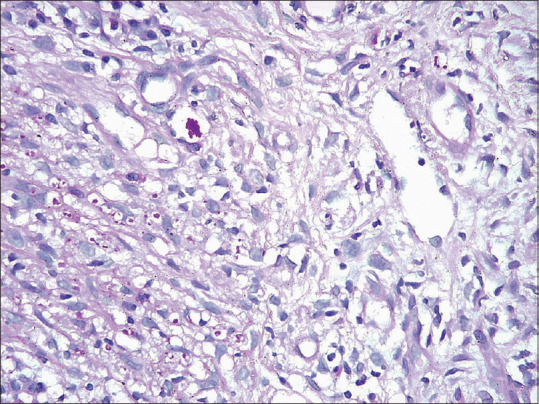

In cryptococcosis, the dermis showed loose epithelioid cell granulomas and medium-sized spores lying extracellularly [Figure 17].

Figure 17.

Showing PAS-positive variably sized spores of cryptococcus. (H and E ×400)

In penicilliosis, both of which were HIV positive, the dermis showed an admixture of histiocytes, epithelioid cells, plasma cells, lymphocytes and polymorphs. The cytoplasm of histiocytes and epithelioid cells showed the presence of yeast-like spores, some of which exhibited transverse septa formation giving rise to sausage-shaped spores [Figure 18].

Figure 18.

(PAS × 1000) showing sausage-shaped spores of penicilliosis with clearly visualised transverse septa formation

In entomophthoromycosis, the dermis and subcutaneous fat showed marked inflammation with microabscesses and epithelioid granuloma formations interspersed with eosinophils and plasma cells. Areas of necrosis were seen. Many eosinophilic and pale staining broad ribbon-like pauciseptate fungal hyphae were seen within the granulomas and the cytoplasm of giant cells. The fungal hyphae demonstrated the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon [Figure 19].

Figure 19.

(PAS × 400): Showing broad ribbon-like pauciseptate hyphae of entomopthoromycosis surrounded by Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon

Discussion

Deep fungal infections have a chronic indolent course, with variable and often overlapping clinical presentations. As per depth of invasion, they can be classified into two groups: subcutaneous and systemic. Subcutaneous types of mycoses present with various cutaneous manifestations. In the case of systemic infections, primary infection occurs in the lungs from where it disseminates to other organs of the body via hemato-lymphogenous route. Subcutaneous mycoses, also called implantation mycoses, are seen sporadically mainly in the tropics and subtropics. There is usually a preceding history of penetrating trauma. They can result in chronic disability.[1,2]

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic cutaneous or subcutaneous deep fungal infection. Infection is acquired by traumatic inoculation in exposed parts of the body.[3] The fungus is ubiquitous in nature and is found in our surroundings in dead and decaying matter, including solid and dead plants. People engaged in agricultural work are at risk and the lower extremity is the commonest site of infection.[4] Characteristic histologic features consist of pseudoepitheliomatous epidermal hyperplasia. The dermis shows oedema and areas of micro abscess formation along with ill-defined epithelioid cell granulomas which contain both foreign body and Langhan’s giant cells. The characteristic sclerotic bodies or copper penny bodies are best visualised in a routine H and E stain where the thick-walled spores clustered together can be recognised due to the brown pigment in their walls. Normally the histopathologic diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis can be easily made, however, when the fungal load is low, they can be missed. All layers of the skin must be examined carefully and sometimes spores may be found sitting in the stratum corneum because of the phenomenon of trans epidermal elimination.[5] Special stains are not routinely required for identifying the spores as the spores contrast well in the H and E stains. However, a PAS stain may help when the fungal load is low and the melanin content is less. Chromoblastomycosis was the most common deep fungal infection in our study. Infections are most commonly presented in the extremities followed by the face. The most common clinical presentation was a verrucous lesion and in approximately 50% of the cases, the first clinical diagnosis was tuberculosis verrucosa cutis (TBVC). In one case, the verrucous proliferation was so florid that the lesion was excised completely with margins marked by sutures. Two cases had presented as ulcers on the extremities. The ulcer histology was, however, typical of chromoblastomycosis.

Rhinosporidiosis was the third most common deep fungal infection in our study. Its most common clinical presentation was as polypoid friable masses hanging from the nasal cavity. Two of the cases had ocular fungal masses and in one case disseminated Rhinosporidiosis with multiple deep nodules all over the body was found. This patient did not have any nasal lesions of rhinosporidiosis. Infection is caused by Rhinosporidium Seeberi which gains entry through traumatic injury of delicate mucosal skin of humans. Patients usually give a history of taking a bath in a pond. Sessile or pedunculated polyps can occur in the nose, nasopharynx and soft palate. Cutaneous involvement without any preceding nasal mucosal lesion is rare and usually occurs in the form of warty masses.[6] In our study, a single case had disseminated rhinosporidiosis, and presented with multiple superficial and deep-seated nodules. The histology of rhinosporidiosis is so characteristic that a reliable tissue diagnosis can be rendered with confidence. The dermis reveals the thick-walled sporangia which in turn are packed with spores. Granuloma formation was not very robust as maximum dermal tissue space is packed with sporangia.

Eumycetoma caused by true fungi was the second most common deep mycoses documented in our study. It usually presents as woody hard swelling that undergoes tumefaction and later develops multiple discharging sinuses.[7] Granules are typically discharged from the sinuses. On histology, beneath a hyperplastic epidermis, the dermis shows foci of suppuration surrounded by lymphocytes, plasma cells and histiocytes. At the centre of the abscesses, the sulfur granules are found which comprise filamentous bacteria (actinomycetoma) or broad septate hyphae (eumycetoma). Special stains like Gram stain, PAS stain and GMS stains should be liberally applied to distinguish between actinomycetoma and eumycetoma. Differentiating between the two is important as the treatment modalities vary.[8] All cases of eumycetoma in the current study had woody hard pigmented swelling with multiple solid papules beneath the swelling which used to rupture on the surface with a small opening, discharging whitish or pigmented granules. The swellings were painless to start with and in due course of time few patients complained of intermittent bony pain. The consistency was firm to soft and the surface showed sero-purulent discharge with black granules from sinuses. Eumycetoma is often confused with actinomycosis which is caused by the spread of infection from Actinomyces spp. which is a gram-positive anaerobic filamentous bacteria and is a commensal in the mouth, digestive system and genitals. It can also cause cutaneous manifestations in the shoulder girdle, pelvic girdle or cervicofacial regions which can be confused clinically with mycetoma.[9] Gram staining is useful in identifying the bacterial colonies where filamentous branching bacteria are seen at the periphery of the granule.[10]

Phaeohyphomycosis is a subcutaneous fungus caused by dematiaceous mycelia-forming fungus and its most common presentation is in the form of deep-seated cyst in the lower leg on the dorsum of the foot or around the ankle.[11] Because of its presentation, it is most often misdiagnosed as an epidermal cyst and excised in toto. In our study, apart from the lower legs, one was located on the lower back. On histology, a deep-seated cyst is seen devoid of epithelial lining. The cyst wall is fibrocollagenous and shows epithelioid cell granulomas with giant cells. Very often cholesterol clefts are present in the wall and this finding is a novel observation made by the first author (Subhra Dhar). Probably the location of the cyst in the subcutaneous fat with resultant breakdown of fat due to host inflammatory response or virulence of the fungus is responsible for this finding. Pigmented fungal hyphae with thick septations make the fungus easily recognisable. Melanin which is the source of pigmentation is also responsible for its virulence like in all dematiaceous fungi.[12] The phaeohyphomycosis usually occurs due to direct traumatic injury and in one of our cases, the incriminating wood splinter was found in the cyst lumen.

Sporotrichosis is typically classified as cutaneous or extracutaneous. The cutaneous form has three subtypes: lymphocutaneous, fixed and disseminated. In lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis, the primary lesion occurs at the site of inoculation mostly in the distal upper extremities and new lesions appear along the lymphatic tracts in a linear pattern subsequently. The fixed cutaneous form is characterized by a painless violaceous or erythematous plaque that may ulcerate or become verrucous. Disseminated cutaneous form is usually seen in immunosuppressed individuals.[13] In our study, the most common presentation was lymphocutaneous type on the upper limbs followed by the chest. Pseudo-epitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with abscesses and loose to well-formed tuberculoid granulomas accompanied by fibrosis in the dermis are present histologically. Star-like eosinophilic material or asteroid bodies were not a frequent finding in our study. However, clusters of round to oval spores that showed narrow-based budding were found in four cases. These spores were not easily identifiable in routine H and E stains and special stains like PAS and GMS should be liberally applied to identify them.[14] Though cigar-shaped spores have been described in sporotrichosis, round budding yeast forms were most commonly found in our study.

Histoplasmosis is widely distributed throughout the world. The organism lends itself to easy recognition on histology but a high degree of awareness for the fungus helps in its correct identification in tissue sections. Common cutaneous presentations include polymorphic papules, plaques with or without crusts, pustules, nodules, mucosal ulcers, erosions and punched-out ulcers associated with fever and malaise.[15] Of the ten cases in our study, five had presented as palatal ulcers and the remaining five had papulonodular lesions on the skin. Histoplasma is a dimorphic fungus and is endemic in West Bengal and the organism has been isolated from the soil in the Gangetic plain.[16] Humans acquire infection when microaeroliospores are released from the soil and are inhaled into the respiratory tract. Soil rich in bird and bat droppings are ideal for the growth of histoplasma. Of importance is the fact that fresh faeces of birds do not contain the fungus, rather the decomposed faeces of birds and bats make the soil nitrogenous which promotes the growth and sporulation of the fungus. Birds themselves are not carriers of the fungus however, bats can harbour the fungus. Caves are rich in bat droppings therefore cave explorers or spelunkers are at increased risk of histoplasmosis. Once the spores reach the lungs the host immune response kicks in which decides the course of infection. Skin manifestations are usually seen with disseminated histoplasmosis. Unlike in the West where histoplasmosis is an opportunistic infection in HIV/AIDS, in India disseminated infections have been seen in non-immunocompromised hosts too.[17] The histopathology ranged from suppurative granulomas to just sheets of histiocytes being present in the dermis depending on the immunogenic response mounted by the host. The organisms were found within the cytoplasm of histiocytes/epithelioid cells or even extracellularly. On histology, histoplasmosis is often misdiagnosed as leishmaniasis which is a protozoal infection.[18] The round basophilic LD bodies are similar in appearance to the histoplasma spores, but they do not show budding and are negative for PAS and GMS.

There were two cases of penicilliosis both of which were HIV positive and were from the north-eastern states of India. P. marneffei is the third most common opportunistic infection in HIV infection after tuberculosis and cryptococcosis. Fever, weight loss, anaemia and generalised papulonodular lesions all over the body are its common manifestations. After the first isolation of P. marneffei from bamboo rats in Vietnam, its subsequent isolation in four species of bamboo rats in China, Thailand, and Vietnam points towards their importance in epidemiologic studies. This is further substantiated by the fact that the geographic distribution of these four species of bamboo rats correlates with the distribution of P. marneffei. In India, the bamboo rat species of the genus Cannomys have been found in Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Manipur and Tripura.[19] However, there is no clear consensus on the role of bamboo rats in transmission of the disease to humans and soil is the most probable reservoir.[19] In cutaneous lesions, the fungus elicits a granulomatous suppurative response just like histoplasmosis. Its yeast form is the form in which it is found in human tissues either intracellularly in histiocytes or extracellularly can be confused with histoplasmosis because of its size, however, it can be distinguished by the presence of intracellular cell wall unlike histoplasma, Penicillium divides by fission.[20] It is the observation of the first author (SD) that the central septation is better visualised under the oil immersion lens of the microscope.

Hyalohyphomycosis is a heterogeneous group of mycoses present in the tissue as hyaline hyphae. The term has been coined as opposed to pheohyphomycosis in which pigmented septate hyphae are found in the tissues. The term is particularly useful when the causative agent that is hyaline septate hyphal forms has just been observed in the tissues without any accompanying culture studies. A number of organisms have been implicated in causing hyalohyphomycosis including Fusarium, Penicillium, Scedosporium, Acremonium, Aspergillus and others. Localised infections occur due to traumatic implantation like in other subcutaneous mycosis with similar histologic findings. Disseminated forms are common in immunocompromised hosts.[21] In our study, we found five cases of hyalohyphomycoses of which three were deep-seated cysts in the lower legs and two presented as abscesses in the lower and upper limbs. Tissue histopathology showed a mix of suppurative and granuloma formation with giant cells. The hyaline septate hyphae were found within cysts and abscesses.

Cryptococcosis is an opportunistic fungal infection, clinically manifesting as pulmonary infection or meningoencephalitis. Cryptococcus neoformans and C. gattii cause human infection of Cryptococcus neoformans is responsible for meningitis in CD4+ deficient patients. Cryptococcus thrive in soil contaminated by guano. It has sexual and asexual forms of which the asexual or yeast form is found in the infected human body. Cryptococcosis is an opportunistic infection in immunosuppressed individuals like patients of AIDS, transplant patients and those on immunosuppressive therapy who can have disseminated disease.[22] Skin lesions are markers of disseminated disease however primary cutaneous lesions can occur in non-immunocompromised hosts. The skin lesions may be papules, pustules, nodules, abscesses, oedema, panniculitis, ulcers and cellulitis-like and molluscum contagiosum-like lesions.[23] No skin lesion is characteristic of cryptococcosis making biopsy evaluation a must. Patients with cutaneous involvement should be investigated for systemic involvement, particularly in the lungs and CNS. In histopathology, the yeast forms of cryptococcosis are usually widely separated by their thick mucoid capsules. PAS stain decorates the yeasts and mucicarmine stain decorates the highly characteristic gelatinous capsule a bright pink.[24] In our case, the dermis showed loose epithelioid cell granulomas and medium-sized spores lying extracellularly.

Cutaneous entomophthoromycosis usually affects immunocompetent patients and is of two types: Basidiobolomycosis and conidiobolomycosis. The spores of the fungus are present in moist, decomposing, or rotting plants/vegetation and faecal matter of amphibians/reptiles. The infection is acquired by trauma and following inhalation of spores. Clinical presentation includes subcutaneous firm swelling with loss of skin pinchability.[25] In histopathology, eosinophilic granulomatous tissue reaction patterns with PAS-positive broad aseptate hyphae with Splendore–Hoeppli phenomenon are often found.[25] In our cases there was marked inflammation in the dermis and subcutaneous fat with microabscess and epithelioid granuloma formations interspersed with eosinophils and plasma cells. Many eosinophilic and pale staining broad ribbon-like pauciseptate fungal hyphae were seen within the granulomas and also within the cytoplasm of giant cells along with the presence of Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon.

The most important risk groups for deep mycoses include farmers, rangers and gardeners as the fungi are usually found in soil and decaying materials. Other risk factors include alcoholism, diabetes and other conditions of immunosuppression.[26]

Clinical differentials of deep mycoses include osteomyelitis, squamous cell carcinoma, botryomycosis and cutaneous tuberculosis. Clinically and histopathologically, tuberculosis verrucosa cutis is the differential diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis. The presence of brown spores in tissue biopsy clinches the diagnosis. Histopathological differentials of phaeohyphomycosis are other deep mycoses where hyphal forms are found in deep tissue, such as aspergillosis and zygomycosis. Similarly, the histopathological differential of rhinosporidiosis is coccidioidomycosis caused by Coccidioides immitis, which has smaller spores and spherules. Myosperulosis is characterised by clusters of RBCs in tissue spaces.

Direct microscopy with potassium hydroxide can demonstrate the fungi in spores or tissue fragments or discharge material, but sensitivity is low. Culture is the gold standard, as it helps in the definitive identification of the causative organism and further molecular identification, if available. In resource-poor settings, such facilities may not be always available, and in such cases, histopathology of tissue biopsy can be of immense help in diagnosis and special stains will help in differentiating from other close clinical differentials. The first author (SD) prefers PAS stain over GMS to confirm the presence of fungus in tissues as in GMS stains the normal collagen fibres can be mistaken for fungal hyphae. This observation is similar to Guarnes and Brandt.[14]

In the literature review, we came across a study by Verma S et al., from northeast India.[1] The age distribution was similar to our study. The majority of the patients in our study were male, possibly because of more outdoor habits, the chance of acquiring infections through traumatic injury was higher in them. Another interesting point was except for two, all our cases were immunocompetent individuals, which was similar to the study by Verma S et al. The study by Verma S et al. showed chromoblastomycosis to be the most common deep fungal infection, in our study too chromoblastomycosis was the commonest. Histopathology played an important role in the diagnosis of cases in their study like that of ours. In another study by Bhat RM et al., chromoblastomycosis (64%) was the most common followed by mycetoma (16%) which is similar to our study.[27] The most common site in this study was also lower limbs (64%) like ours. Males (64%) outnumbered females, like in our study. Most patients in their study were agricultural workers, but history of trauma was less.[28] Similarly, Borodoloi P et al. also reported chromoblastomycosis (40%) as the commonest, followed by hyalohyphomycosis (20%), however in our study eumycetoma was second most common.[29]

Table 2 gives a comparison of the characteristics of our study to the previous Indian studies.

Table 2.

Comparison between the Indian studies

| Characteristics | Verma et al. | Bhat et al. | Borodoloi et al. | Our study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total participants | 70 | 25 | 15 | 124 |

| Region | North-east | South | North-east | Eastern |

| Gender ratio | 44: 26 | 64: 36 | - | 94: 30 |

| Occupation | Agriculture worker, 92% | Agriculture worker | - | Agriculture worker |

| Previous trauma | 76% | 3/25 | - | 45/124, 36.3% |

| Most common site involved | Lower limb, 46% | Lower limb, 64% | - | Lower limb 83/124, 67% |

| Most common type of mycoses | Chromoblastomycosis, 30/70 | Chromoblastomycosis, 64% | Chromoblastomycosis, 6/15, 40% | Chromoblastomysosis 42/124 |

| Investigation used for diagnosis confirmation | Histopathology | Clinical | Histopathology, culture | Histopathology |

| Fungal culture positivity | 55.7% | - | - | - |

Conclusion

Our study highlights a few unique histological features helpful in diagnosing deep mycoses which were hitherto undescribed in the literature to the best of our knowledge. This is a very large study from various parts of India with varied morphological and interesting histopathological features.

Strength of the study

New clinico-morphological variants of chromoblastomycosis have been described. We found that penicilliosis is better identified under the oil immersion microscope as the transverse septae can be easily identified. We have described cholesterol clefts within the phaeohphomycotic cyst.

Limitations of the study

This is a retrospective data analysis only. There was no confirmation of fungi by parallel culture studies.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Verma S, Thakur BK, Raphael V, Thappa DM. Epidemiology of subcutaneous mycoses in Northeast India: A retrospective study. Indian J Dermatol. 2018;63:496–501. doi: 10.4103/ijd.IJD_16_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Samaila MO, Abdullahi K. Cutaneous manifestations of deep mycosis: An experience in a tropical pathology laboratory. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56:282–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.82481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal R, Singh G, Ghosh A, Verma KK, Pandey M, Xess I. Chromoblastomycosis in India: Review of 169 cases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005534. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandran V, Sadanandan SM, Sobhanakumari K. Chromoblastomycosis in Kerala, India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:728–33. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.102366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo TY, Rasmussen JE. Disorders of transepidermal elimination. Part 1. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:267–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1985.tb05781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shenoy MM, Girisha BS, Bhandari SK, Peter R. Cutaneous rhinosporidiosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2007;73:179–81. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.32742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elkheir LYM, Haroun R, Mohamed MA, Fahal AH. Madurella mycetomatis causing eumycetoma medical treatment: The challenges and prospects. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14:e0008307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alam K, Maheshwari V, Bhargava S, Jain A, Fatima U, Haq EU. Histological diagnosis of madura foot (mycetoma): A must for definitive treatment. J Glob Infect Dis. 2009;1:64–7. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.52985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sadeghi S, Azaïs M, Ghannoum J. Actinomycosis presenting as macroglossia: Case report and review of literature. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:327–30. doi: 10.1007/s12105-018-0966-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma S, Hashmi MF, Valentino DJ., III . StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Jan, [[Updated 2023 Feb 19]]. Actinomycosis. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482151 . [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chintagunta S, Arakkal G, Damarla SV, Vodapalli AK. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis in an immunocompetent Individual: A case report. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2017;8:29–31. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.198770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Isa-Isa R, García C, Isa M, Arenas R. Subcutaneous phaeohyphomycosis (mycotic cyst) Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:425–31. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahajan VK, Sharma NL, Shanker V, Gupta P, Mardi K. Cutaneous sporotrichosis: Unusual clinical presentations. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76:276–80. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.62974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247–80. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00053-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang P, Rodas C. Skin lesions in histoplasmosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:592–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2012.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dhar S, Dutta Roy RKD, Todi SK, Roy S, Dhar S. Seven cases of histoplasmosis: Cutaneous and extracutaneous involvements. Ind J Dermatol. 2006;51:137–9. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gupta A, Ghosh A, Singh G, Xess I. A twenty-first-century perspective of disseminated histoplasmosis in India: Literature review and retrospective analysis of published and unpublished cases at a tertiary care hospital in North India. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:1077–93. doi: 10.1007/s11046-017-0191-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deepe GS., Jr Outbreaks of histoplasmosis: The spores set sail. PLoS Pathog. 2018;14:e1007213. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh PN, Ranjana K, Singh YI, Singh KP, Sharma SS, Kulachandra M, et al. Indigenous disseminated Penicillium marneffei infection in the state of Manipur, India: Report of four autochthonous cases. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2699–702. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2699-2702.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baradkar V, Kumar S, Kulkarni SD. Penicillium Marneffei: The pathogen at our doorstep. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:619–20. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.57733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stephen Y, Wong N, Wong KF. Penicillium marneffei Infection in AIDS. Pathol Res Int. 2011;2011:764293. doi: 10.4061/2011/764293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tortorano AM, Richardson M, Roilides E, van Diepeningen A, Caira M, Munoz P, et al. ESCMID and ECMM joint guidelines on diagnosis and management of hyalohyphomycosis: Fusarium spp., Scedosporium spp. and others. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20((Suppl 3)):27–46. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akram SM, Koirala J. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Jan, [[Updated 2023 Feb 25]]. Cutaneous Cryptococcus. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448148/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, Enokihara MMSES, Porro AM. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: Report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92((5 Suppl 1)):69–72. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/cryptococcosis-pathology .

- 26.Singh S, Shahid R, Pradhan S, Kumar T, Gupta R. Cutaneous entomophthoromycosis from Bihar: A report of three cases and review of literature. Indian J Dermatol. 2022;67:610–3. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_439_22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bhat RM, Monteiro RC, Bala N, Dandakeri S, Martis J, Kamath GH, et al. Subcutaneous mycoses in coastal Karnataka in south India. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:70–8. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh TJ, Dixon DM. Spectrum of Mycoses. In: Baron S, editor. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. Galveston (TX): University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston; 1996. Chapter 75. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK7902/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bordoloi P, Nath R, Borgohain M, Huda MM, Barua S, Dutta D, et al. Subcutaneous mycoses: An aetiological study of 15 cases in a tertiary care hospital at Dibrugarh, Assam, northeast India. Mycopathologia. 2015;179:425–35. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9861-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]