Abstract

Background

The aim was to evaluate and validate a bowel disease questionnaire in patients attending an out-patient gastroenterology clinic in Greece.

Methods

This was a prospective study. Diagnosis was based on detailed clinical and laboratory evaluation. The questionnaire was tested on a pilot group of patients. Interviewer-administration technique was used. One-hundred-and-forty consecutive patients attending the out-patient clinic for the first time and fifty healthy controls selected randomly participated in the study. Reliability (kappa statistics) and validity of the questionnaire were tested. We used logistic regression models and binary recursive partitioning for assessing distinguishing ability among irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), functional dyspepsia and organic disease patients.

Results

Mean time for questionnaire completion was 18 min. In test-retest procedure a good agreement was obtained (kappa statistics 0.82). There were 55 patients diagnosed as having IBS, 18 with functional dyspepsia (Rome I criteria), 38 with organic disease. Location of pain was a significant distinguishing factor, patients with functional dyspepsia having no lower abdominal pain (p < 0.001). Significant factors distinguishing between IBS and functional dyspepsia were relief of pain by either antacids or defecation (19% vs 71% and 66% vs 0% respectively). Awakening from pain at night was also a factor distinguishing between IBS and organic disease groups (26% vs 61%, p < 0.01).

Conclusions

This questionnaire for functional bowel disease is a valid and reliable instrument that can distinguish satisfactorily between organic and functional disease in an out-patient setting.

Introduction

Functional bowel disorders form a heterogeneous group of clinical syndromes related to the gastrointestinal tract that present no histological, endoscopic or imaging abnormalities and are not the result of infectious or metabolic disease. Due to our limited understanding of their pathogenesis, functional bowel disorders remain largely a diagnosis of exclusion. This fact, together with a feeling of uncertainty on the part of the physician, may lead to many unnecessary and expensive tests and examinations in order to rule out cancer or a possibly serious organic disease [1,2]. If there is a situation where the medical history makes an essential contribution towards reaching the correct diagnosis, this holds true for the patient with functional bowel disorders. The need for simple and valid diagnostic criteria for these disorders which are best defined by their symptoms, has led to the search of clusters of positive symptoms that are thought of as characteristic for patients with functional disorders [3,4]. A symptom-based diagnostic classification system has recently been developed by multinational working teams, better known as Rome Committees, resulting in diagnostic criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders [5].

In order to elicit symptoms relevant to functional disorders, the administration of questionnaires has been proved as valuable. It has been shown that a bowel disease questionnaire may be of value in the gastroenterology outpatient setting, where functional bowel symptoms are commonly reported. Several questionnaires have been evaluated assessing the two major functional bowel disorders, i.e. the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional dyspepsia (non-ulcer dyspepsia), and trying to distinguish them both from organic diseases and from each other [6-8].

The aim of the present study was 1) to evaluate a bowel disease questionnaire that had been designed for Greek patients attending an out-patient gastroenterology clinic and 2) to analyze the data obtained.

Methods

Geography and health system

The island of Crete, which has approximately 550,000 inhabitants, is divided into four administration prefectures. Each prefecture has a local hospital but there is only one tertiary care hospital: the University Hospital, in Heraklion. The prefecture of Heraklion has approximately 280,000 inhabitants, of which 150,000 are urban and the remaining 130,000 are rural residents. The Gastroenterology Department of the University Hospital of Heraklion is the referral centre for gastrointestinal patients of the island. At the same time it fulfils the function of a primary care centre for subjects with gastrointestinal complaints who are residents of the prefecture of Heraklion. This is due to the structure of the Greek National Health System, according to which subjects from a prefecture are entitled to attend outpatient clinics of a tertiary care Hospital without referral from their general practitioners or rural physicians.

Questionnaire creation and mode of administration

We created a questionnaire based on the symptom-oriented questionnaire described by Talley et al [9], with several adaptations, and the consensus Rome I criteria [10]. The text of symptom-related questions was formulated by a physician with extensive experience in the management of gastrointestinal outpatients (NF). Two gastroenterologists (IM, PS) revised the text and made necessary changes by eliminating ambiguous questions and expressions in order to get a clear and relevant questionnaire. After reaching the final version, the questionnaire was tested on a pilot group of 30 out-patients using self-administration technique. Only 12 out of the 21 returned questionnaire forms were adequately filled-in so as they could be further evaluated. In order to get reliable results we decided to continue the study using the interviewer-administration technique. Our decision was buttressed by the fact that in a group of 15 patients where it was possible to use both administration techniques, we obtained identical results. The interviewer for all patients was a final year medical student (AK).

Participants

One-hundred-and-forty consecutive patients attending the outpatient Gastroenterology clinic of the University Hospital of Heraklion for the first time and complaining of abdominal pain, discomfort or disturbed stool movements were invited to provide responses to the questionnaire. There was a refusal rate of 8.6% (12 patients). Fifty healthy controls were randomly selected from visitors to the Orthopedic department of the same hospital. None of them had visited a physician for gastrointestinal symptoms during the last three years. After one to two weeks, the questionnaire was given to be completed for a second time in 12 patients whose symptoms remained stable during this period and in 6 controls in order to check for the concordance of the answers (reliability). After a period of one to three month of clinical evaluation and follow up, a diagnosis was provided by two experienced gastroenterologists (IM, NF). Responses to the questionnaire were not used for the final diagnosis. Healthy controls did not undergo any clinical tests. The final diagnosis was made independently of the questionnaire responses and was based on the results of the clinical and laboratory investigation. All patients underwent endoscopic evaluation of upper or/and lower digestive tract, and ultrasound of upper abdomen, while CT scan was performed when needed. The Rome I diagostic criteria as described in [10] were used, consisting for IBS in the followings: at least 3 months of continuous or recurrent symptoms of 1. Abdominal pain or discomfort that is a) relieved with defecation; and/or b) associated pain with a change in frequency of stool and/or c) associated with a change in consistency of stool; and/or 2. Two or more of the following, at least one-fourth of occasions or days: a)altered stool frequency; b)altered stool form;c)altered stool passage; d)passage of mucus; e) bloating or feeling of abdominal distention [10]. Patients were reached by telephone call 1.5–2 years after diagnosis for a further confirmation of the final diagnosis. In four cases no conclusive diagnosis was reached. Fourteen patients were lost to follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Pearson's chi-square tests were performed to assess whether the patients differed from the control subjects with respect to qualitative sociodemographic variables. The factors assessed were gender, marital status, occupation, birth rank, educational and area of residence. Comparisons of the age distribution between patients and controls were made using the Student's t-test. One-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was used to assess possible differences in age distribution between the patient groups. Subsequently, the applicability of the bowel disease questionnaire in distinguishing between the three bowel disease groups was investigated. Initially, logistic regression models were fitted to examine differences in responses between the disease groups for each of the questionnaire items separately, having adjusted for possible age and sex effects. The significance of each of the factors was obtained by calculating the decrease in deviance when the factor was included in the model (given the null model including age and sex only) and comparing this to the appropriate chi-square distribution. In those questions involving abdominal pain, a separate category was included within each item for those patients who did not respond that they had abdominal pain more than six times in the previous year.

In order to determine whether the three patient groups could be separated on the basis of their questionnaire responses, classification rules for the diagnostic groups based on patient responses were derived. Models were fitted using binary recursive partitioning. With these classification models, the initial split is on the most significant predictor and the construction method chooses the next split in an optimal way. In order to determine whether the model could be made more parsimonious without sacrificing its goodness-of-fit, the least important splits were removed using the cost-complexity measure Dα(T')=D(T') + a size(T'), where D(T') is the deviance of sub-tree T', size(T') is the number of terminal nodes of T' and a is the cost-complexity parameter. For the present study, with three classification groups, taking a = 4 enables one to find the subtree with minimum Akaike's Information Criterion, (this criterion penalizes minus twice the log-likelihood by twice the number of independent parameters) [11]. Finally, cross-validation was performed by splitting the data into ten mutually exclusive sets.

The test-retest reliability of the questionnaire was judged with the use of the Kappa statistic to assess concordance between questionnaire responses on two separate occasions. A kappa value of 1 corresponds to a perfect concordance and a value of 0 to a concordance not different from chance [12].

The statistical packages used were SPSS version 7.5 and S-Plus (version 4.5).

Results

The mean time for interview and completion of the questionnaire was 18 minutes. The subjects who participated understood and answered the questions easily. On re-testing, which was performed on 18 persons at an interval of 7–14 days, significant agreement on all answers was obtained. Median kappa statistic for all questions was 0.82 (range 0.56 to 1.0).

There were 55 patients diagnosed as having IBS, 18 patients with functional dyspepsia, both groups according to the Rome criteria [13], and 38 patients with organic disease (14 with peptic ulcer or gastroesophageal reflux disease, 7 with diseases of the biliary tract, 6 with inflammatory bowel disease, 2 with self-limited infectious colitis, 3 with bacterial overgrowth syndrome, and the remaining 6 patients with various diseases, among these 2 malignancies: cancer of the ampulla of Vater, and of the colon). The one patient who was diagnosed as having both functional dyspepsia and organic disease was excluded from the statistical analysis. Also excluded were the 18 subjects that did not completed the evaluation (14 lost to follow-up and 4 with no conclusive diagnosis).

The demographic characteristics of the patients and controls are presented in Table 1. There was no significant difference in age or in sex ratios between patients (median age 54 years, 43% males) and controls (median age 50 years, 58% males). More patients than expected (p < 0.0005) were educated at most to primary level; 74% of patients (95 observed, 85 expected) compared to 46% (23 observed, 33 expected) of the control group (υ2 = 12.81 on 1 df). Also, more than expected patients came from rural areas (p = 0.012), 73 observed versus 65 expected (υ2 = 6.4 on 1 df). The homogeneity between the patient groups with regard to their demographic characteristics is indicated by the percentages presented in Table 1. The only significant difference between groups was with respect to age distribution, with organic disease patients being older than those suffering from IBS (p = 0.002).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients and controls answering bowel disease questionnaires

| Irritable bowel syndrome patients | Functional dyspepsia patients | Organic disease patients | Patients lost to follow-up | All Patientss | Control group | |

| Number of subjects | 55 | 17 | 37 | 14 | 128 | 50 |

| Sex | ||||||

| male (%) : female (%) | 18 (33) : 37 (67) | 9 (53) : 8 (47) | 19 (51) : 18 (49) | 7 (50) : 7 (50) | 56 (43) : 72 (57) | 29 (58) : 21 (42) |

| Residence | ||||||

| rural (%) | 34 (62) | 8 (47) | 23 (62) | 6 (43) | 73 (57) | 18 (36) |

| Education | ||||||

| none or primary (%) | 39 (71) | 14 (82) | 29 (78) | 11 (79) | 95 (74) | 23 (46) |

| Age, median (mean, SE) | 46 (49, 1.6) | 58 (56, 3.3) | 63 (58, 2.8) | 54 (56, 4.3) | 54 (53, 1.3) | 50 (48, 2.5) |

sOf the 128 patients who agreed to participate and answered the questionnaire, no conclusive diagnosis was reached for four subjects and one person diagnosed as having both dyspepsia and organic disease was omitted from the study. The only evidence of a difference between the patient groups for the demographic variables was in the age distributions. *p < 0.05, chi-square **p < 0.0005, chi-square test

The prevalence of symptoms in the subgroups of patients with IBS, functional dyspepsia and organic disease and also in the control group is presented in table 2. Having had abdominal pain on at least six occasions in the previous year was a very common symptom (over 88%) in every disease group. It can be seen that the location of the abdominal pain is a significant distinguishing factor, with patients with functional dyspepsia having no lower abdominal pain (p < 0.001). Other significant factors distinguishing the IBS from the functional dyspepsia group were whether there was pain relief by antacids (19% in IBS, 71% in functional dyspepsia patients), whether pain was relieved on defecation (66% in IBS, 0 in functional dyspepsia patients) and having more stools when the pain began (49% in IBS, 6% in functional dyspepsia patients). For the IBS versus organic disease comparisons, awaking from the pain at nighttime was significantly more often present in patients with organic disease (26% in IBS, 61% in organic disease patients, p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Prevalence of signs and symptoms in patients with IBS, functional dyspepsia or organic disease and controls, and comparisons of IBS with dyspepsia and organic disease patients using logistic regression models.

| IBS (n = 55) | Functional dyspepsia (n = 17) | Organic disease (n = 37) | Healthy controls (n = 50) | IBS vs Dyspepsia | IBS vs Organic Disease | |

| % | % | % | % | × 2statistic (change df), p-value | × 2statistic (change df), p-value | |

| Abdominal pain >6 times last year | 96 | 100 | 89 | 36 | ns | ns |

| Location of pain*: | ||||||

| Upper abdomen | 4 | 94 | 55 | 50 | 58.01 (2), p < 0.0001 | 32.70 (2), p < 0.001 |

| Lower abdomen | 45 | 0 | 15 | 22 | 17.70 (2), p < 0.001 | 30.42 (2), p < 0.001 |

| All abdomen | 51 | 6 | 30 | 28 | 13.33 (2), p < 0.001 | 12.87 (2), p < 0.001 |

| Presence of pain*: | ||||||

| <1 year | 34 | 29 | 55 | 28 | ns | ns |

| <2 years | 17 | 24 | 18 | 17 | ns | ns |

| >2 years | 49 | 47 | 27 | 56 | ns | ns |

| Duration of pain*: | ||||||

| >6 hours | 40 | 35 | 39 | 17 | ns | ns |

| Frequency of pain*: | ||||||

| > once a week | 74 | 77 | 70 | 22 | ns | ns |

| Pain reflection*: | ||||||

| No reflection | 73 | 70 | 61 | 88 | ns | ns |

| Spine | 6 | 12 | 21 | 6 | ns | ns |

| Hips | 13 | 6 | 12 | 6 | ns | ns |

| Elsewhere | 8 | 12 | 6 | 0 | ns | ns |

| Night pain (wakes subject)* | 26 | 71 | 61 | 28 | 9.76 (2), p < 0.01 | 9.48 (2), p < 0.01 |

| Pain relieved by antacids* | 19 | 71 | 36 | 50 | 17.48 (2), p < 0.001 | 6.06 (2), p < 0.05 |

| Pain affected by eating* | 30 | 77 | 46 | 50 | 13.13 (2), p < 0.01 | ns |

| Pain appears after meal* | 21 | 47 | 36 | 22 | 7.30 (2), p < 0.05 | ns |

| Pain alleviated by eating* | 6 | 24 | 6 | 33 | ns | ns |

| Pain made worse by eating* | 19 | 41 | 21 | 11 | ns | ns |

| Pain relieved by defecation* | 66 | 0 | 39 | 33 | 29.05 (2), p < 0.001 | 7.24 (2), p < 0.05 |

| More stools when pain begins* | 49 | 6 | 30 | 17 | 14.82 (2), p < 0.001 | ns |

| Looser stools when pain begins* | 53 | 6 | 33 | 17 | 13.72 (2), p < 0.05 | ns |

| Pain worse after defecation* | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ns | ns |

| Change noticed in bowel habits in the last year | 24 | 6 | 35 | 4 | 3.91 (1), p < 0.05 | ns |

| >3 bowel movements/day | 16 | 0 | 35 | 4 | 6.46 (1), p < 0.05 | ns |

| <3 bowel movements/week | 20 | 18 | 11 | 20 | ns | ns |

| Have both constipation and diarrhoea | 24 | 12 | 16 | 6 | ns | ns |

| Take medication for constipation | 16 | 6 | 11 | 6 | ns | ns |

| Stools often hard | 40 | 41 | 27 | 20 | ns | ns |

| Have difficulty defecating | 51 | 29 | 30 | 14 | ns | ns |

| Stools often loose & watery | 38 | 12 | 38 | 10 | 5.07 (1), p < 0.05 | ns |

| Feeling of incomplete emptying | 47 | 12 | 32 | 4 | 9.22 (1), p < 0.01 | ns |

| Often feel that can't delay defecation | 36 | 18 | 35 | 8 | 4.14 (1), p < 0.05 | ns |

| Passage of mucus | 27 | 0 | 24 | 2 | 7.48 (1), p < 0.01 | ns |

| See blood on defecation: | 31 | 6 | 24 | 14 | ns | ns |

| when wiping | 29 | 6 | 22 | 14 | ns | ns |

| in stools | 15 | 6 | 16 | 2 | ns | ns |

| Have haemorrhoids | 36 | 12 | 24 | 16 | ns | ns |

| Need to defecate wakes subject | 9 | 6 | 22 | 0 | ns | ns |

| Incontinence | 4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ns | ns |

| Abdominal distension | 82 | 88 | 51 | 28 | ns | 5.58 (1), p < 0.05 |

| Have previously visited physician for one of the problems mentioned | 86 | 94 | 70 | 12 | ns | ns |

*For pain related questions, the percentages displayed are the percentages of those subjects who have the pain symptom (55 IBS, all 17 functional dyspepsia, 33 organic disease, 18 controls)

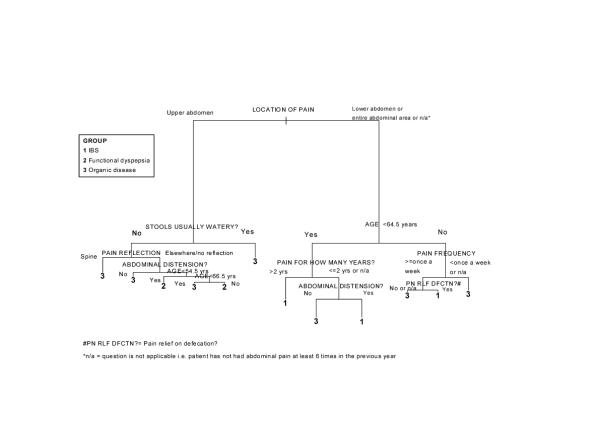

An example of classification using the model provided in fig. 1 is as follows: a subject aged 45 presenting with pain in the lower abdomen which he/she has had for less than two years, feeling bloated, the pain not being related to eating a meal, would be classified as having IBS (with a probability greater than 0.99) as opposed to having functional dyspepsia or organic disease. If the same subject stated that the pain was related to eating a meal, he/she would again be classified as having IBS using the model, but the probability is now 0.625 versus 0.375 of having organic disease. When the model in fig. 1 was subjected to cost-complexity pruning, the pruned model had nine terminal nodes, with the splits following the pain reflection question now not included (i.e. feeling bloated and the subject's age). The cost of increasing the simplicity of the model was that the misclassification rate rose from 20% to 24%. Cross-validation that was performed on the model indicated that perhaps the most important questions contained in the questionnaire were the presence and location of the abdominal pain and having loose bowel movements.

Figure 1.

A graphical depiction of the recursive partitioning model classifying gastrointestinal patients as having IBS, functional dyspepsia or organic disease based on responses to a bowel disease questionnaire.

Discussion

In this study we evaluated a questionnaire that was developed for patients attending a Gastroenterology out-patient Clinic in Greece. In the design of our questionnaire several instruments proposed by other authors were taken into account [4,8,14-19]. As most of these studies were performed in selected populations, the question has been already raised whether the results might not be representative for persons belonging to other groups [20]. We intended to elaborate an instrument that could differentiate among patients with functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome and organic gastrointestinal disease. We had to adapt our instrument for use within the Greek linguistic and cultural milieu. To provide a disease questionnaire for respondents belonging to other groups requires adaptation, modification and establishing its validity within a different cultural context [21].

In the present study we took these steps under the guidance of a panel of physicians familiar with functional bowel disease. The instrument was validated in subjects having an open access to a Gastroenterology Department and coming from a referral area of 250.000 inhabitants, both rural and urban. Rural residents and subjects with only primary educational level were met more often in the patients' group than in that of healthy controls, the latter consisting of visitors to hospitalized patients. This fact reflects the constitution of the patients' group, which was representative of the whole referral area, in contrast to the controls who came from the urban area of the Hospital. Besides, the control group represented a random sample of the population, thus explaining the fact that several of the controls met the Rome IBS criteria. It has to be reminded that surveys of Western populations have revealed IBS in 15–20% of adolescents and adults [22].

Due to a low yield of answered questionnaires when self-administered mode was first undertaken, we used the interviewer-administered technique. All respondents understood the items without difficulty. The instrument was shown to discriminate well among the disease groups of organic disease, functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome. For reasons of consistency and applicability of the results of this study, we used the Rome I criteria for IBS [10]. The questionnaire for functional bowel disease was shown to be reliable: persons who were asked at two different occasions gave comparable answers.

Concerning the symptoms differentiating between IBS and functional dyspepsia, the most important features in our patients were 1) the location of pain, 2) whether the pain was relieved on defecation or by antacids and 3) whether there were more stools when the pain began. In distinguishing between IBS and organic disease, the most prominent features were the awaking from the pain at night and whether the pain was relieved by defecation or antacids. Our results, and especially the criterion referring to pain being relieved by defecation, can be considered as a further validation of the Rome II criteria distinguishing IBS from other groups [22].

When trying to interpret our results, the recursive partitioning model offers the advantage of simplification. Figure 1 is a graphical representation of the model used to discriminate between the three disease groups forming the hospital outpatient sample. The discrimination rules and corresponding probabilities of being in each disease group are presented. There are 13 terminal nodes. The model has a correct classification rate of 80% (22 patients misclassified out of 109). The most significant binary split in the discrimination process is the question related to the location of abdominal pain, and more specifically whether pain is present in the upper abdomen. On the basis of this question alone, the model splits the patients in two groups: those with either IBS or organic disease and those with functional dyspepsia or organic disease. The other significant factors in distinguishing between possible IBS and organic disease patients are the age of the subject, the duration of time for which they have had such a pain, the feeling of bloatedness, the frequency of the pain and whether pain is relieved on defecation.

Having determined the localization of pain, significant factors in distinguishing between possible functional dyspepsia and organic disease are the presence of loose stools, whether or not there was reflection of pain to the spine, the presence of bloating and the age of the subject. An important advantage of the recursive partitioning approach over logistic regression is that enables the IBS, functional dyspepsia and organic disease groups to be modeled simultaneously. At the same time, the rules derived are easy to interpret. A summary of the rules derived from the model is provided in Additional File:Appendix.

There are a few drawbacks in this study, some of them being shared with similar studies. The model we used assumes that patients fall into exactly one of the three categories, excluding the possibility that a patient may not have any of the three conditions or may have two of them. In fact, only one patient in this study had both organic and functional disease. As this coincidence may not be a rarity in other, differently selected, populations, it constitutes a drawback of this kind of model. A more important point may be the finding that the results of bowel disease questionnaires were not reproduced in comparable and unselected populations [23]. Therefore, the diagnostic value of our instrument may also have little external validity. A further drawback of this study may be the small number of the sample, especially the group with functional dyspepsia. This fact may influence the validity of the comparisons concerning functional dyspepsia but not those concerning functional as opposed to organic diseases. At last, self-administration of the questionnaire, a process that is considered both unbiased for the patient and time-saving for the doctor, was not feasible in the context of this study. None the less, the interview technique proved to be time-saving and to give a better yield of answers and a minimal rate of uncompleted questions.

In conclusion, our study showed that the questionnaire for functional bowel disease we have developed is a valid and reliable instrument in the particular cultural and linguistic setting of Greek patients. This questionnaire can distinguish satisfactorily between organic and functional disease. The classification oriented model derived from the evaluation of the results obtained is easy to interpret and it could be used in the out-patient setting.

Conpeting interests

None declared.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Supplementary Material

Appendix. Rules for the classification of gastrointestinal patients into one of three disease groups derived from a recursive partitioning model.

Contributor Information

Ioannis A Mouzas, Email: mouzas@med.uoc.gr.

Nikolaos Fragkiadakis, Email: pansk@caramail.com.

Joanna Moschandreas, Email: joanna@med.uoc.gr.

Andreas Karachristos, Email: pansk@caramail.com.

Panagiotis Skordilis, Email: skordilis@her.forthnet.gr.

E Kouroumalis, Email: kouroum@med.uoc.gr.

Orestes N Manousos, Email: mouzas@med.uoc.gr.

References

- Talley NJ, Gabriel SE, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Evans RW. Medical costs in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1736–41. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90738-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, et al. Irritable bowel syndrome: the view from general practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:689–92. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WG, Heaton KW. Functional bowel disorders in apparently healthy people. Gastroenterology. 1980;79:283–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning AP, Thompson WG, Heaton KW, et al. Towards positive diagnosis of the irritable bowel. Br Med J. 1978;2:653–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6138.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome II process. Gut. 1999;45:1–5. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler RS, Drossman DA, Nathan HP, et al. Symptom complaints and health care seeking behavior in subjects with bowel dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:314–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svedlund J, Sjodin I, Dotevall G. GSRS – A clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;93:129–34. doi: 10.1007/BF01535722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Sandler RS, McKee DC, et al. Bowel patterns among subjects not seeking health care. Use of a questionnaire to identify a population with bowel dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:529–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J, et al. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:671–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-8-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Richter JE, Talley NJ, eds et al. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates. 1 1994. The functional gastrointestinal disorders: diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment. [Google Scholar]

- Venables WN, Ripley BD. Berlin: Springer. 2 1997. Modern applied statistics with S-PLUS. [Google Scholar]

- Koran LM. The reliability of clinical methods, data and judgements. N Engl J Med. 1975;293:642–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197509252931307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DA, Richter JE, Talley NJ, et al. The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology and Treatment. Boston: Little, Brown, 1994.

- Thompson WG. Gastrointestinal symptoms in the irritable bowel compared with peptic ulcer and inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1984;25:1089–92. doi: 10.1136/gut.25.10.1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks JC, de Dombal FT. Clinical presentation of patients with "dyspepsia": detailed symptomatic study of 360 patients. Gut. 1978;19:19–26. doi: 10.1136/gut.19.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruis W, Thieme CH, Weinzierl M, et al. A diagnostic score for the irritable bowel syndrome. Its value in the exclusion of organic disease. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw M, Talley NJ, Adlis S, et al. Development of a digestive health status instrument: tests of scaling assumptions, structure and reliability in a primary care population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:1067–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dogan UB, Unal S. Kruis scoring system and Manning's criteria in diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome: is it better to use combined? Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1996;59:225–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruis W. Irritable bowel syndrome: questionnaires and scores. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14:42C–4C. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman DE. A questionnaire for functional bowel disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:627–9. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-8-627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streiner DL, Norman GR. Devising the items. In: Streiner DL, Norman GR, editor. Health measurement scales. A practical guide to their development. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 15–27. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson WG, Longstreth GF, Drossman DA, et al. Functional bowel disorders and functional abdominal pain. Gut. 1999;45:43–47. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2008.ii43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starmans R, Muris JW, Fijten GH, et al. The diagnostic value of scoring models for organic and non-organic gastrointestinal disease, including the irritable-bowel syndrome. Med Decis Making. 1994;14:208–16. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9401400302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix. Rules for the classification of gastrointestinal patients into one of three disease groups derived from a recursive partitioning model.