Abstract

The nucleoprotein (NP) of influenza B virus is 50 amino acids longer at the N-terminus than influenza A virus NP and lacks homology to the A virus protein over the first 69 residues. We have deleted the N-terminal 51 and 69 residues of the influenza B/Ann Arbor/1/66 virus NP and show that nuclear accumulation of the protein is unaffected. This indicates that the nuclear localization signal is not located at the extreme N terminus, as in influenza A virus NP. To determine if the N-terminal mutants could support the expression and replication of a model influenza B virus RNA, the genes encoding the subunits of the viral RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PA, PB1, and PB2) were cloned. Coexpression of NP and the P proteins in 293 cells was found to permit the expression and replication of a transfected model RNA based on segment 4 of B/Maryland/59, in which the hemagglutinin-coding region was replaced by a chloramphenicol acetyltransferase gene. The expression and replication of the synthetic RNA were not affected by the replacement of NP with NP mutants lacking the N-terminal 51 or 69 residues, indicating that the N-terminal extension is not required for transcription or replication of the viral RNA. In addition, we report that the influenza B virus NP cannot be functionally replaced by type A virus NP in this system.

Influenza A and B viruses have segmented genomes, each comprising eight negative-strand RNAs. The virion RNAs are complexed with nucleoprotein (NP) and subunits of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (PA, PB1, and PB2) to form viral ribonucleoproteins (vRNPs) (18). After the entry and uncoating of the virus, vRNPs enter the cell nucleus, where transcription and replication of the viral RNA takes place. The NP facilitates the nuclear import of vRNPs by interacting with proteins belonging to the karyopherin α family of nuclear transport factors (NPI-1 and NPI-3) (27–29). In addition, the NP of influenza A virus has been implicated in the determination of host range (32), the initiation of viral mRNA synthesis (3), RNA elongation (11), and the switch between mRNA and cRNA synthesis (antitermination) (5).

The region of the influenza A virus NP responsible for RNA binding has been mapped to the N-terminal third of the protein, specifically between residues 1 and 77 and 79 and 180 (1, 17). Recently, it was reported that the N terminus of influenza A virus NP also contains a nonconventional nuclear localization signal (NLS) (25, 34). Significantly, influenza B virus NP lacks homology to the A virus protein at the N terminus. For all influenza B virus isolates for which the sequences are available (7, 9, 13, 20, 31), the NP is 50 amino acids longer at the N terminus than the A virus protein, and indeed lacks homology to influenza A virus NP over the first 69 residues (Fig. 1). The length and amino acid sequence of the N-terminal extension are highly conserved among influenza B virus NPs, implying that it may have a conserved function.

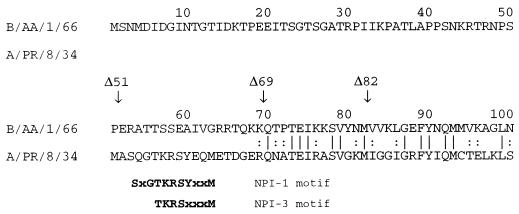

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the amino acid sequences of the influenza A/PR/8/34 and B/AA/1/66 virus NPs at the N-termini. The alignment was generated with the FASTA program (Genetics Computer Group, University of Wisconsin) and predicts 37.7% identity and 76.2% similarity of the proteins in a 496-amino-acid overlap. The residues in influenza A/PR/8/34 virus NP reported by Wang et al. (34) to interact with NPI-1 and NPI-3 are shown in boldface below the influenza A virus sequence. Neumann et al. (25) have separately reported that residues Lys7 and Arg8 are crucial for nuclear import of the A/WSN/33 NP. Arrows indicate the extent of the N-terminal deletions in the type B virus NP made in this study, vertical lines denote amino acid identity, and colons refer to conservative changes.

Recently, the amino acid residues in influenza A virus NP that interact with nuclear transport factors NPI-1 and NPI-3 were identified (34). The NPI-1 and NPI-3 binding motifs are located in the N-terminal 13 residues of influenza A virus NP (Fig. 1) but are absent from this position in the type B virus NP and are not found elsewhere in the protein. The NP of influenza B virus also lacks classical mono- and bipartite NLSs such as those described for the large T antigen of simian virus 40 and nucleoplasmin, respectively (26). It is therefore of interest to investigate the function of the conserved N-terminal extension of influenza B virus NP, and in particular to determine if this region contains an NLS.

Cloning of the influenza B/AA/1/66 virus NP gene.

To assess the role of the N-terminal residues of influenza B virus NP, the cDNA for the B/AA/1/66 NP gene was amplified by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) with primers based on the published sequence (9). Influenza B/AA/1/66 virus was grown at 34°C in 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs and purified from the allantoic fluid 48 h postinfection by centrifugation through a 30% sucrose cushion. The virus was resuspended in TMK (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl), lysed by the addition of sodium dodecyl sulfate to 0.3%, and then digested with 2 U of proteinase K (GIBCO/BRL) for 10 min at 56°C. The viral RNA was then purified by phenol extraction and precipitated with ethanol. Approximately 200 ng of viral RNA was used for reverse transcription with 100 ng of an oligonucleotide (NPstart; 5′ gcgcgcaagcttATCAAAATGTCCAACATG 3′) annealing to residues 53 to 70 of the segment 5 RNA which encodes the NP (numbering for all oligonucleotides listed here is of the positive-sense RNA). Reverse transcription was performed with a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, the four dNTPs (1 mM each), 30 U of human placental RNase inhibitor (Pharmacia), and 5 U of avian myeloblastosis virus reverse transcriptase (GIBCO/BRL). The product was amplified by PCR with NPstart and an oligonucleotide (NPstop; 5′ gcgcgcgtcgacGTTGCTTTAATAATCGAG 3′) annealing to residues 1730 to 1747 with Vent DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). The NP gene was then cloned on a HindIII-SalI fragment into mammalian expression vector pcDNA3 (Invitrogen) under the control of the human cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter/enhancer, generating plasmid pcDNA3-NP.

Next, we made deletions which removed the N-terminal extension (NPΔ51) and all of the nonhomologous sequence at the N terminus (NPΔ69) (Fig. 1). The NPΔ51 mutant lacks amino acid residues 2 to 51 and was generated by PCR with oligonucleotide 5′ gcgcgcaagcttATCAAAATGGAAAGGGCAACCACAAGC 3′ and NPstop, with pcDNA3-NP as the template. The product was cloned into pcDNA3 as described for NP, giving pcDNA3-NPΔ51. Mutant NPΔ69 lacks amino acids 2 to 69 and was generated with oligonucleotide 5′ gcgcgcaagcttATCAAAATGCAAACCCCGACAGAG 3′ and NPstop, giving pcDNA3-NPΔ69. We also deleted further into the protein (residues 2 to 82) by PCR with oligonucleotide 5′ gcgcgcaagcttATCAAAATGGTAGTGAAACTGGGT 3′ and NPstop, giving pcDNA3-NPΔ82. Proteins of the expected size were synthesized in in vitro translation reactions with T7 run-off transcripts from SmaI-linearized pcDNA3-NP, pcDNA3-NPΔ51, pcDNA3-NPΔ69, and pcDNA3-NPΔ82 (Fig. 2A).

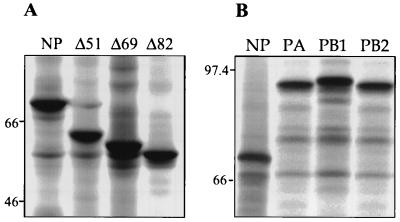

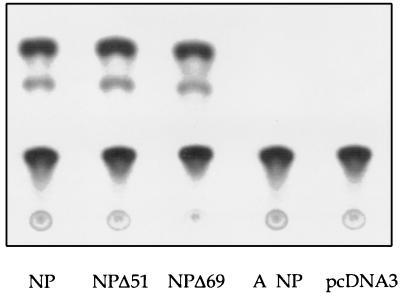

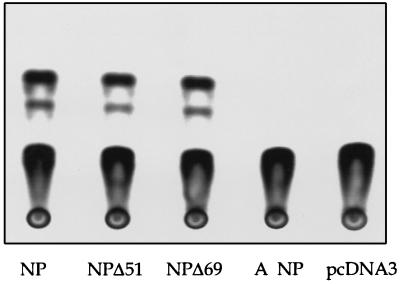

FIG. 2.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of the influenza B/AA/1/66 virus NP and NP deletion mutants (A) and of influenza B/AA/1/66 virus polymerase proteins (B) synthesized in vitro. Rabbit reticulocyte lysates (Promega) were primed with 50 ng of T7 transcripts from SmaI-linearized templates in the presence of [35S]methionine according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Proteins were resolved on an SDS–10% PAGE gel and visualized by autoradiography. Numbers refer to the sizes in kilodaltons of protein standards.

N-terminal deletions in influenza B virus NP do not affect nuclear accumulation.

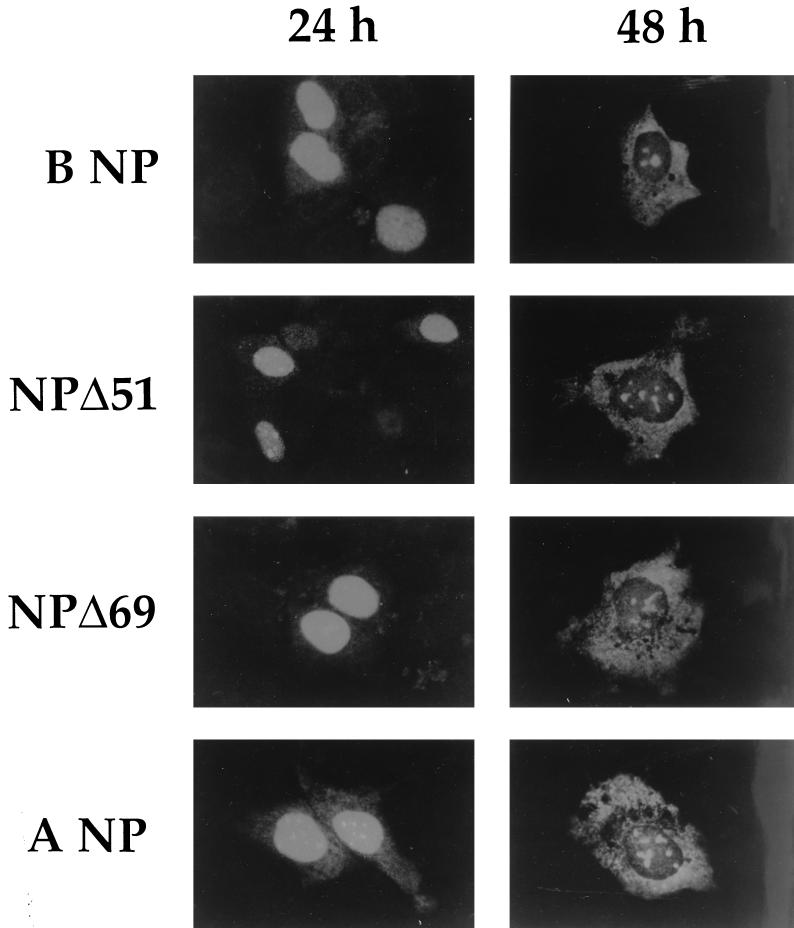

Plasmids for the expression of NP, NPΔ51, NPΔ69, and NPΔ82 were transfected into MDCK cells, and the proteins were visualized by indirect immunofluorescence with a mouse anti-B virus NP monoclonal antibody (MAb) and an anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate. We were unable to detect NPΔ82 with either of two different anti-B virus NP MAbs (data not shown), which may indicate that the protein is unstable when expressed in mammalian cells. In cells fixed 24 h posttransfection, NP, NPΔ51, and NPΔ69 were found to accumulate mostly in the nucleus (Fig. 3). However, in cells fixed 48 h posttransfection NP, NPΔ51, and NPΔ69 were distributed mostly in the cytosol. This pattern was also observed upon transfection of plasmid pHMG-NP, which contains the influenza A/PR/8/34 virus NP gene under the control of a mouse hydroxymethylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase promoter (kindly supplied by J. Pavlovic, University of Zürich, Zürich, Switzerland) (Fig. 3), and is consistent with observations that NP expressed in the absence of other virus proteins is capable of shuttling between the nucleus and cytosol (25, 35).

FIG. 3.

Localization of NP and NP deletion mutants in MDCK cells. MDCK cells (American Type Culture Collection; CCL 34) were grown on glass coverslips to 50 to 70% confluency and were transfected with 5 μg of pcDNA3-NP, pcDNA3-NPΔ51, pcDNA3-NPΔ69, or pHMG-NP (encoding A/PR/8/34 NP), by using 30 μg of Pfx-2 lipofection reagent (Invitrogen) in serum-free Eagle’s minimal essential medium. Twenty-four or forty-eight hours after transfection the cells were fixed and permeabilized with −20°C absolute ethanol for 5 min and then analyzed by indirect immunofluorescence with a mouse anti-B virus NP MAb (MAS774b; Harlan Sera-lab) and an anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-fluorescein isothiocyanate conjugate. Samples were mounted with Mowiol 40-88 and 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (Aldrich) and analyzed with a Zeiss Axiovert 135 fluorescence microscope and a 100× oil immersion lens. The same localization of NP or the NP deletion mutants was observed if the cells were fixed with 3% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde and permeabilized with 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (data not shown).

Our data indicate that the N-terminal extension of influenza B virus NP does not contain the sole NLS. The region of the influenza A virus NP responsible for nuclear accumulation has been mapped by Wang et al. (34) to residues 1 to 13 and separately by Neumann et al. (25) to residues 1 to 38. In both cases, the N-terminal residues have been shown to possess NLS activity, since they can target a normally cytoplasmic protein to the nucleus (25, 34). However, the authors of both reports concede that mutants lacking part or all of the NLS still enter the nucleus, indicating that other, perhaps weaker, NLSs exist in the protein.

Earlier results with influenza A virus NP had suggested that a motif which determines the accumulation of NP in the nuclei of Xenopus oocytes was located between residues 327 and 345 (8). This region is conserved in the NP of influenza B/AA/1/66 virus; however, its importance in determining the nuclear accumulation of type A virus NPs in mammalian cells is contested (25, 34). The identification of the sequence(s) responsible for the nuclear accumulation of the influenza B virus NP awaits further mutagenesis of the protein.

A plasmid-based system to study the expression and replication of influenza B virus RNAs.

A number of systems to study the expression and replication of influenza virus RNAs have been described. Luytjes et al. (21) first reported that RNP complexes reconstituted in vitro with purified NP and P proteins and a synthetic influenza virus RNA containing a cat gene could give rise to CAT activity following transfection into helper virus-infected cells. It has since been shown that functional RNP complexes can be reconstituted in vivo, since cells which supply NP and the P proteins in trans from plasmids, vaccinia virus, or simian virus 40 recombinants, can support the expression and replication of a transfected model influenza A virus RNA (6, 10, 12, 15, 22, 38). To establish such a system for influenza B virus, the genes encoding PA, PB1, and PB2 were cloned from B/AA/1/66 into pcDNA3.

The PA gene was amplified by reverse transcription from B/AA/1/66 viral RNA and PCR with oligonucleotides PAstart (5′ gcgcgcgaattcGCCATAATGGATACTTTT 3′) and PAstop (5′ gcgcgcgtcgacCTTCTTTCATTCATCCAT 3′), which anneal to residues 24 to 41 and 2199 to 2116, respectively. The PB1 gene was amplified with oligonucleotides PB1start (5′ gcgcgcgaattcTTTAAGATGAATATAAATCC 3′) and PB1stop (5′ gcgcgcgtcgacCGAAGCTTATATGTGCCC 3′), which anneal to residues 16 to 35 and 2269 to 2286, respectively. Both the PA and PB1 RT-PCR products were cloned on EcoRI-SalI fragments into pcDNA3. We were unable to amplify the full-length PB2 gene from B/AA/1/66 viral RNA by RT-PCR; therefore, the gene was cloned in two halves, by making use of primers PB2start (5′ gcgcgcgaattcTTCAAGATGACATTGGCC 3′ [anneals to residues 18 to 35]) and PB26 (5′ gcgcgcGAAtTCCTCTTCTCCG 3′ [1103 to 1118]) and primers PB27 (5′ gcgcgcGAaTTCCATGTAAGATG 3′ [1113 to 1129]) and PB2stop (5′ gcgcgcgtcgacTTTATATTAGCTCAAGGC 3′ [2324 to 2342]). Oligonucleotides PB26 and PB27 introduce a silent change (G→A at position 1115) to generate an EcoRI site. The product of RT-PCR with PB2start and PB26 was first cloned into the EcoRI site of pcDNA3, and then the PB27 and PB2stop RT-PCR product was cloned into this plasmid on an EcoRI-SalI fragment.

To confirm that the cloned cDNAs for the B/AA/1/66 NP and P genes encode proteins of the expected size, in vitro translation reactions were performed with T7 transcripts from SmaI-linearized pcDNA3-NP, pcDNA3-PA, pcDNA3-PB1, and pcDNA3-PB2. With the exception of PB2, the electrophoretic mobilities of the proteins correlated with their predicted molecular weights (Fig. 2B). The PB2 protein migrated at a rate below that expected on the basis of its predicted molecular weight; however, this has also been noted for the PB2 protein of B/Panamá/45/90 (13). Proteins corresponding in size to the influenza B/AA/1/66 virus NP and P proteins were identified in a preparation of purified radiolabeled B/AA/1/66 virus (data not shown).

To test the activities of the cloned NP and P proteins, plasmids pcDNA3-NP, pcDNA3-PA, pcDNA3-PB1, and pcDNA3-PB2 were cotransfected into 293 cells and the cells were transfected at intervals thereafter with a synthetic influenza B virus RNA (HABCAT). The HABCAT RNA is based on segment 4 of B/Md/59 and contains a negative-sense cat gene in place of the hemagglutinin coding region (4). We observed that chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) activity could be detected if the cells were transfected with the plasmids and the RNA at the same time, but not if the RNA was added three or more hours after the plasmids (Fig. 4). The ability to detect CAT indicates that the transfected RNA was reconstituted intracellularly into functional RNPs capable of synthesizing mRNA. The level of CAT activity obtained on transfection of the HABCAT RNA into cells supplying NP and the P proteins in trans was comparable to the levels achieved on transfection of the naked RNA into helper virus-infected cells (data not shown). The amounts of the model RNA and plasmids for the expression of NP and P proteins which yielded the highest levels of CAT conversion were pcDNA3-PA, 0.5 μg; pcDNA3-PB1, 0.5 μg; pcDNA3-PB2, 0.5 μg; pcDNA3-NP, 1 μg; and HABCAT RNA, 1 μg. No CAT activity was detected if the HABCAT RNA alone was transfected, or if any one of the four plasmids was omitted (data not shown). This is consistent with the observation by Jambrina et al. (13) that NP and the three P proteins are the minimum set of influenza B virus proteins required for the expression of a model RNA.

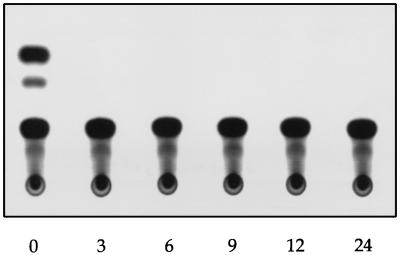

FIG. 4.

Expression of HABCAT RNA in cells supplying PA, PB1, PB2, and NP in trans. Approximately 106 293 cells in 35-mm-diameter dishes were transfected with 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PA, 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PB1, 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PB2, and 1 μg of pcDNA3-NP by using 20 μg of Lipofectamine (GIBCO/BRL) in serum-free Eagle’s minimal essential medium (EMEM) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. At time zero and at 3, 6, 9, 12, and 24 h after transfection of the plasmids a separate mixture of 1 μg of HABCAT RNA and 20 μg of Lipofectamine was added. HABCAT RNA was synthesized in vitro in a 25-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μg of HgaI-linearized pT3HABCAT (4), 40 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl, 8 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM spermidine, the four dNTPs (1 mM each), 30 U of human placental RNase inhibitor, and 50 U of T3 RNA polymerase. After incubation at 37°C for 1 h, 2 U of RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega) was added to remove the template and the RNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. After 24 h at 37°C the cells were supplemented with 1 ml of EMEM containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. Forty-eight hours posttransfection the cells were harvested into 100 μl of 250 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and lysed by freezing and thawing three times. Lysates (50 μl) were then processed for the detection of CAT as described elsewhere (21).

N-terminal deletions in influenza B virus NP do not affect the expression of HABCAT RNA.

To determine if the N-terminal extension plays a role in the ability of NP to support the expression of a model influenza B virus RNA, 293 cells were transfected with HABCAT RNA, the polymerase clones, and plasmids for the expression of either NP, NPΔ51, or NPΔ69. Wild-type levels of CAT conversion were observed when NPΔ51 or NPΔ69 was supplied (Fig. 5). We also obtained approximately equal levels of CAT conversion when pcDNA3-NP, pcDNA3-NPΔ51, and pcDNA3-NPΔ69 were supplied at a range of suboptimal amounts while keeping the concentrations of the P clones and HABCAT RNA the same (data not shown). This indicates that the N-terminal extension of influenza B virus NP is not involved in the binding of NP to the RNA or the initiation and elongation of transcription.

FIG. 5.

Expression of HABCAT RNA is not affected by the removal of the N-terminal extension of influenza B virus NP. 293 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PA, 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PB1, 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PB2, and 1 μg of either pcDNA3-NP, pcDNA3-NPΔ51, pcDNA3-NPΔ69, pHMG-NP, or pcDNA3 by using 20 μg of Lipofectamine. Immediately after, a separate mixture of 1 μg of HABCAT RNA and 20 μg of Lipofectamine was added.

The influenza B virus plasmid-based system can be used to study the replication of viral RNA.

It has been reported that cells which supply the influenza A virus NP and P proteins in trans are capable of synthesizing viral RNA from a transfected model cRNA template (12). In order to determine if the cloned influenza B virus NP and P proteins can synthesize viral RNA, 293 cells were cotransfected with plasmids for the expression of the NP and P proteins and a synthetic RNA corresponding to the cRNA intermediate of HABCAT RNA replication. We were able to detect CAT activity in the transfected cells, at levels comparable to those achieved with negative-sense HABCAT RNA (Fig. 6). A low level of CAT activity could be detected if the HABCAT cRNA was cotransfected into cells with pcDNA3 in place of the NP and P plasmids, indicating that the RNA can be weakly translated. The ability to detect elevated levels of CAT in the cells supplying NP and P proteins suggests that viral RNA was synthesized from the input RNA and was subsequently transcribed to give mRNA. We observed that deletion of the N-terminal 51 or 69 residues of the NP did not affect its ability to support the replication of the transfected model RNA in this system (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Replication of HABCAT RNA is not affected by removal of the N-terminal extension of influenza B virus NP. In order to synthesize the cRNA intermediate of HABCAT replication, the HABCAT cDNA was cloned under a T3 promoter in the reverse orientation to that in pT3HABCAT (4) by PCR with oligonucleotides 5′ gcgcgcaagcttgacgcatcgaAGTAGTAACAAGAGC 3′ and 5′ gcgcgcgaattcaattaaccctcactaaaAGCAGAAGCAGAGC 3′. 293 cells were transfected with 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PA, 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PB1, 0.5 μg of pcDNA3-PB2, and 1 μg of either pcDNA3-NP, pcDNA3-NPΔ51, pcDNA3-NPΔ69, pHMG-NP, or pcDNA3 by using 20 μg of Lipofectamine. Immediately after, a separate mixture of 1 μg of HABCAT cRNA and 20 μg of Lipofectamine was added.

Influenza B virus NP cannot be functionally replaced by type A virus NP.

We also investigated if the influenza A virus NP is capable of replacing the type B virus NP in the plasmid-based system by supplying pHMG-NP in place of pcDNA3-NP. Plasmid pHMG-NP encodes the A/PR/8/34 NP and has been used to drive the expression of an influenza A virus model RNA in the plasmid-based system described by Pleschka et al. (30). No CAT activity was detected in the transfection by using pHMG-NP, the influenza B virus P clones, and either HABCAT RNA (Fig. 5) or the cRNA intermediate of HABCAT replication (Fig. 6), indicating that the influenza A virus NP cannot form functional RNP complexes with the B virus polymerase proteins and a model influenza B virus RNA. It is known, however, that the four influenza A virus core proteins can form functional RNPs with a model influenza B virus RNA, whether this complex is reconstituted in vitro (19, 24) or in vivo (13).

The finding that type A and B virus NPs are not interchangeable is consistent with the observations of Jambrina et al. (13) and indicates that there are type-specific interactions between NP and the P proteins that are essential for the expression and replication of the virus genome. This notion is supported by the finding that natural reassortment of the NP and P genes of influenza A and B viruses is not observed (14, 23). We consider this surprising, as the sequences of the type A and B virus NPs have 37.7% identity and 76.2% similarity over a 496-amino-acid overlap. It seems unlikely that the N-terminal extension of influenza B virus NP is involved in type-specific interactions with the type B virus P proteins, since its removal does not affect the activity of the RNP complex.

It is possible that the N-terminal extension of type B virus NP has a role in the specific incorporation of vRNPs into influenza B virus particles. It has been reported that, while type A and B virus NPs may exist in the same RNP complex in vivo, these phenotypically mixed forms are not incorporated into virions (33). Since the NPs of type A and B viruses differ most at their N termini, the N-terminal extension may be involved in the selection of RNPs containing only type B virus NP.

The type-specific nature of the interaction of NP with the P proteins may be influenced by differences in the posttranslational processing of the influenza A and B virus NPs. It is known that influenza A virus NP is modified by phosphorylation (2, 16) and by proteolytic cleavage (36). The extent of these modifications varies with the virus strain, the cell line on which the virus is grown, and the phase of the replication cycle (16, 36, 37). The type B virus NP is also proteolytically cleaved, but in a manner distinct from that in which influenza A virus NPs are cleaved (37).

Posttranslational processing of the NP may also modulate the nuclear import and export of the protein. There is evidence that the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the influenza A virus NP may be controlled by phosphorylation, since protein kinase inhibitor H7 causes the redistribution of NP (expressed in the absence of other virus proteins) from the cytosol to the nucleus (25). So far nothing is known of the sites and extent of phosphorylation of type B virus NP, or whether the proteolytic processing of NP is relevant to its activity. The plasmid-based system described here may prove useful in assessing the importance of posttranslational modifications of the NP, and in identifying those regions of the influenza B virus NP that are involved in type-specific interactions with the P proteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant to W.S.B. from the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom (G9508170).

REFERENCES

- 1.Albo C, Valencia A, Portela A. Identification of an RNA binding region within the N-terminal third of the influenza A virus nucleoprotein. J Virol. 1995;69:3799–3806. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3799-3806.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arrese M, Portela A. Serine 3 is critical for phosphorylation at the N-terminal end of the nucleoprotein of influenza virus A/Victoria/3/75. J Virol. 1996;70:3385–3391. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.3385-3391.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bárcena J, Ochoa M, de la Luna S, Melero J A, Nieto A, Ortín J, Portela A. Monoclonal antibodies against influenza virus PB2 and NP polypeptides interfere with the initiation step of viral mRNA synthesis in vitro. J Virol. 1994;68:6900–6909. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.6900-6909.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barclay W S, Palese P. Influenza B viruses with site-specific mutations introduced into the HA gene. J Virol. 1995;69:1275–1279. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.2.1275-1279.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beaton A R, Krug R M. Transcription antitermination during influenza viral template RNA synthesis requires the nucleocapsid protein and the absence of a 5′ capped end. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:6282–6286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.17.6282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biswas S K, Nayak D P. Mutational analysis of the conserved motifs of influenza A virus polymerase basic protein 1. J Virol. 1994;68:1819–1826. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1819-1826.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briedis D J, Tobin M. Influenza B virus genome: complete nucleotide sequence of the influenza B/Lee/40 virus genome RNA segment 5 encoding the nucleoprotein and comparison with the B/Singapore/222/79 nucleoprotein. Virology. 1984;133:448–455. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(84)90412-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davey J, Dimmock N J, Colman A. Identification of the sequence responsible for the nuclear accumulation of the influenza virus nucleoprotein in Xenopus oocytes. Cell. 1985;40:667–675. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeBorde D C, Donabedian A M, Herlocher M L, Naeve C W, Maassab H F. Sequence comparison of wild-type and cold-adapted B/Ann Arbor/1/66 influenza virus genes. Virology. 1988;163:429–443. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90284-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Luna S, Martín J, Portela A, Ortín J. Influenza virus naked RNA can be expressed upon transfection into cells co-expressing the three subunits of the polymerase and the nucleoprotein from simian virus 40 recombinant viruses. J Gen Virol. 1993;74:535–539. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-74-3-535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honda A, Uéda K, Nagata K, Ishihama A. RNA polymerase of influenza virus: role of NP in RNA chain elongation. J Biochem. 1988;104:1021–1026. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang T-S, Palese P, Krystal M. Determination of influenza virus proteins required for genome replication. J Virol. 1990;64:5669–5673. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.11.5669-5673.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jambrina E, Bárcena J, Uez O, Portela A. The three subunits of the polymerase and the nucleoprotein of influenza B virus are the minimum set of viral proteins required for expression of a model RNA template. Virology. 1997;235:209–217. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaverin N V, Varich N L, Sklyanskaya E I, Amvrosieva T V, Petrik J, Vovk T C. Studies on heterotypic interference between influenza A and B viruses: a differential inhibition of the synthesis of viral proteins and RNAs. J Gen Virol. 1983;64:2139–2146. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-64-10-2139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kimura N, Nishida M, Nagata K, Ishihama A, Oda K, Nakada S. Transcription of a recombinant influenza virus RNA in cells that can express the influenza virus RNA polymerase and nucleoprotein genes. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1321–1328. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-6-1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kistner O, Müller K, Scholtissek C. Differential phosphorylation of the nucleoprotein of influenza A viruses. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:2421–2431. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-9-2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobayashi M, Toyoda T, Adyshev D M, Azuma Y, Ishihama A. Molecular dissection of influenza virus nucleoprotein: deletion mapping of the RNA binding domain. J Virol. 1994;68:8433–8436. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.8433-8436.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb R A. Genes and proteins of the influenza viruses. In: Krug R M, editor. The influenza viruses. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1989. pp. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee Y-S, Seong B L. Mutational analysis of influenza B virus RNA transcription in vitro. J Virol. 1996;70:1232–1236. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1232-1236.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Londo D R, Davis A R, Nayak D P. Complete nucleotide sequence of the nucleoprotein gene of influenza B virus. J Virol. 1983;47:642–648. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.3.642-648.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luytjes W, Krystal M, Enami M, Parvin J D, Palese P. Amplification, expression, and packaging of a foreign gene by influenza virus. Cell. 1989;59:1107–1113. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90766-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mena I, de la Luna S, Albo C, Martín J, Nieto A, Ortín J, Portela A. Synthesis of biologically active influenza virus core proteins using a vaccinia-T7 RNA polymerase expression system. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:2109–2114. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-8-2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mikheeva A, Ghendon Y Z. Intrinsic interference between influenza A and B viruses. Arch Virol. 1982;73:287–294. doi: 10.1007/BF01318082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muster T, Subbarao E K, Enami M, Murphy B R, Palese P. An influenza A virus containing influenza B virus 5′ and 3′ noncoding regions on the neuraminidase gene is attenuated in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5177–5181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.12.5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neumann G, Castrucci M R, Kawaoka Y. Nuclear import and export of influenza virus nucleoprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:9690–9700. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9690-9700.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nigg E A. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: signals, mechanisms and regulation. Nature. 1997;386:779–787. doi: 10.1038/386779a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Neill R E, Palese P. NPI-1, the human homolog of SRP-1, interacts with influenza virus nucleoprotein. Virology. 1995;206:116–125. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(95)80026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Neill R E, Jaskunas R, Blobel G, Palese P, Moroianu J. Nuclear import of influenza virus RNA can be mediated by viral nucleoprotein and transport factors required for protein import. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22701–22704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palese P, Wang P, Wolff T, O’Neill R E. Host-viral protein-protein interactions in influenza virus replication. In: McCrae M A, Saunders J R, Smyth C J, Stow N D, editors. Molecular aspects of host-pathogen interactions, SGM Symposium 55. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1997. pp. 327–340. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pleschka S, Jaskunas S R, Engelhardt O G, Zürcher T, Palese P, García-Sastre A. A plasmid-based reverse genetics system for influenza A virus. J Virol. 1996;70:4188–4192. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.6.4188-4192.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rota P A. Sequence of a cDNA clone of the nucleoprotein gene of influenza B/Ann Arbor/1/86. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:3595. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.9.3595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scholtissek C, Bürger H, Kistner O, Shortridge K F. The nucleoprotein as a possible major factor in determining host specificity of influenza H3N2 viruses. Virology. 1985;147:287–294. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90131-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sklyanskaya E I, Varich N L, Amvrosieva T V, Kaverin N V. Virions and intracellular nucleocapsids produced during mixed heterotypic influenza infection of MDCK cells. J Virol. 1985;53:679–683. doi: 10.1128/jvi.53.2.679-683.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang P, Palese P, O’Neill R E. The NPI-1/NPI-3 (karyopherin α) binding site on the influenza A virus nucleoprotein NP is a nonconventional nuclear localization signal. J Virol. 1997;71:1850–1856. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1850-1856.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whittaker G, Bui M, Helenius A. Nuclear trafficking of influenza virus ribonucleoprotein in heterokaryons. J Virol. 1996;70:2743–2756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2743-2756.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhirnov O P, Bukrinskaya A G. Two forms of influenza virus nucleoprotein in infected cells and virions. Virology. 1981;109:174–179. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(81)90482-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhirnov O P, Bukrinskaya A G. Nucleoproteins of animal influenza viruses, in contrast to those of human strains, are not cleaved in infected cells. J Gen Virol. 1984;65:1127–1134. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-65-6-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zobel A, Neumann G, Hobom G. RNA polymerase I catalysed transcription of insert viral cDNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:3607–3614. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.16.3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]