Abstract

Numerous compounds that are scavengers of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) in Fenton systems have low solubility in water. Therefore, they are dissolved in organic solvents to reach suitable concentrations in the reaction milieu of the Fenton system. However, these solvents may react with •OH and iron, leading to significant errors in the results. We evaluated 11 solvents (4 alcohols, acetone, 4 esters, dimethyl-sulfoxide, and acetonitrile) at concentrations ranging from 0.105 µmol/L to 0.42 µmol/L to assess their effects on light emission, a recognized measure of •OH radical activity, in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Six solvents inhibited and four solvents enhanced light emission at all tested concentrations. Acetonitrile, which initially suppressed light emission, lost this effect at a concentration of 0.105 µmol/L, (−1 ± 13 (2; 0) %, p > 0.05). Methanol, at the lowest tested concentration, inhibited light emission by 62 ± 4% (p < 0.05), while butyl butyrate enhanced it by 93 ± 16% (p < 0.05). These effects may be explained by solvent-driven •OH-scavenging, inhibition or acceleration of Fe2+ regeneration, or photon emission from excited solvent molecules. Our findings suggest that acetonitrile seems suitable for preparing stock solutions to evaluate antioxidant activity in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system, provided that the final concentration of this solvent in the reaction milieu is kept below 0.105 µmol/L.

Keywords: chemiluminescence, Fenton system, hydroxyl radicals, organic solvents, aprotic solvents

1. Introduction

Hydroxyl radicals (•OH) are a type of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and are considered the most reactive ROS [1]. The chronic overproduction of ROS in tissues is believed to contribute to various pathologies including persistent inflammation, cancer, autoimmune disorders, as well as cardiovascular and neurological diseases [2,3,4,5,6]. Thus, normalizing ROS levels in the body could have beneficial effects in preventing and treating these diseases [7,8]. One potential approach is an introduction of chemical (or phytochemical) compounds into the body that can react with ROS, forming non-reactive or less reactive derivatives, thereby suppressing tissue ROS levels.

Candidate compounds for such therapies should be tested in vitro with systems generating individual ROS (e.g., •OH, H2O2, superoxide radical, singlet oxygen, hypochlorite, or peroxynitrite) before proceeding to experiments in cell cultures, animal models, and clinical trials to assess their safety and antioxidant effectiveness. The Fenton system, composed of Fe2+ and H2O2, or modified versions such as the Fe3+-EDTA (ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid)-H2O2-ascorbate system is a simple and effective generator of •OH radicals in aqueous solutions and is commonly used to evaluate the anti-•OH (antioxidant) activity of various compounds [9].

Since the direct detection of •OH radicals in aqueous environments is not feasible [10], numerous indirect methods have been developed to measure OH activity. These methods typically involve adding specific •OH probes (e.g., 2-deoxy-D-ribose, N, N’-(5-nitro-1,3-phenylene)-bis-glutaramide, salicylic acid, coumarin, dimethyl-sulfoxide, phthalhydrazide, and rhodamine-based probes) that react with •OH to form by-products in the reaction milieu. The level of these by-products is measured using techniques like spectroscopy, fluorescence, luminescence, or electron spin resonance (ESR) and is used as an indicator of the •OH activity in a given Fenton system with and without the tested antioxidant [9,10,11,12,13,14].

Plant polyphenols, which are recognized as natural antioxidants [15], have been extensively studied for their ability to protect biomolecules from peroxidative damage and therefore play a significant role in preventive medicine [16,17]. Over 8000 phenolic compounds have been identified in various plant species [16]. Since most polyphenols are highly soluble in organic solvents, they are typically extracted from plant materials using solvents such as methanol, ethanol, ethyl acetate, or acetone [18]. Stock solutions of polyphenols are often prepared in organic solvents for in vitro experiments because these solutions are more stable and convenient for laboratory work.

However, using these stock solutions or their aqueous dilutions introduces organic solvents into the Fenton system along with the tested phenolics, which can be the factor responsible for the apparent augmentation of its antioxidant activity or masking of its pro-oxidant effect. To overcome this problem, additional control systems are needed, including experiments with the solvent alone, the solvent with the Fenton system, and the solvent with the incomplete Fenton system. Furthermore, possible interactions between the solvent and the •OH probe should also be excluded. The common approach of subtracting the results obtained for a sample containing the Fenton system, •OH probe, and solvent from those for a mixture of the Fenton system, •OH probe, solvent, and the tested compound introduces errors because it does not account for the differing rates of reaction between the solvent and the tested compound with •OH radicals.

Recently, we developed a modified Fenton system composed of Fe2+-EGTA (ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N, N, N, N -tetraacetic acid) and H2O2 (Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system). In this system, •OH radicals generated through a Fenton reaction can react with ether bonds in an EGTA backbone structure, forming products that contain triplet-excited carbonyl groups [19]. The transition of these carbonyl groups from the excited state to the ground state is accompanied by ultra-weak chemiluminescence (UPE), which serves as an indirect measure of •OH radical activity [19]. By using the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system, we were able to evaluate the pro-oxidant (enhancing UPE) and antioxidant (inhibiting UPE) activities of aqueous solutions of various plant polyphenols [20] and ascorbic acid [21].

We also discovered that dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a commonly used solvent for phenolic solutions, inhibits UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system [19]. This finding suggests that antioxidant samples containing various solvents may produce results with significant errors. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the effect of six typical organic solvents (methanol, ethanol, acetone, ethyl acetate, propan-1-ol, and n-pentanol) and two polar aprotic solvents (acetonitrile and DMSO) at three concentrations (0.105 µmol/L, 0.21 µmol/L, and 0.42 µmol/L) on UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Our goal was to identify solvents that do not affect or minimally affect light emission from the system. Additionally, we tested three less commonly used solvents (benzyl acetate, amyl acetate, and butyl butyrate) to provide further insights into the potential mechanisms behind the effects of these solvents on UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system.

2. Results

All the tested organic solvents demonstrated a significant effect on light emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Six of them (methanol, ethanol, propan-1-ol, n-pentanol, DMSO, and benzyl acetate) inhibited UPE at all tested concentrations, whereas four (acetone, ethyl acetate, amyl acetate, and butyl butyrate) enhanced the light emission. Only acetonitrile, at the lowest concentration of 0.105 µmol/L, did not affect the light emission; however, at higher concentrations (0.21 µmol/L and 0.42 µmol/L), it showed an inhibitory effect (Table 1 and Table 2). These results indicate that the application of antioxidants (e.g., polyphenols and water-insoluble vitamins) dissolved in organic solvents may lead to significant errors and create difficulties in the interpretation of results when tested in the modified Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 Fenton system. Moreover, these findings suggest that there is an advantage of using aqueous solutions of potential antioxidants (even at very low concentrations) in testing antioxidant activity with the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system.

Table 1.

Effect of selected organic solvents on UPE in the complete (Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2) and incomplete (Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2) modified Fenton systems.

| Solvent | Final Solvent Concentration in Reaction Milieu [µmol/L] | Complete System Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 |

Incomplete System Fe2+-EGTA-H2O |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Without Solvent | With Solvent | Without Solvent | With Solvent | ||

| Solvents that inhibit light emission from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system | |||||

| Methanol | 0.105 | 4217 ± 79 (4203; 109) * | 1609 ± 130 (1563; 109) | 753 ± 18 (756; 21) | 786 ± 82 (756; 21) |

| 0.21 | 3925 ± 164 (3871; 108) * | 1202 ± 316 (1355; 365) | 740 ± 32 (727; 46) | 734 ± 17 (730; 23) | |

| 0.42 | 3109 ± 340 (3237; 353) * | 1142 ± 65 (1171; 60) | 654 ± 21 (655; 15) | 626 ± 11 (630; 16) | |

| Ethanol | 0.105 | 3971 ± 248 (3937; 198) * | 1890 ± 35 (1879; 23) | 812 ± 26 (815; 38) | 789 ± 15 (787; 19) |

| 0.21 | 4062 ± 91 (4033; 114) * | 1735 ± 56 (1746; 52) | 733 ± 20 (723; 16) | 725 ± 12 (728; 15) | |

| 0.42 | 3765 ± 165 (3778; 262) * | 1331 ± 47 (1337; 54) | 642 ± 21 (633; 31) | 618 ± 23 (627; 27) | |

| Propan-1-ol | 0.105 | 4214 ± 78 (4203; 101) * | 1457 ± 120 (1447; 90) | 672 ± 25 (673; 27) | 660 ± 16 (651; 23) |

| 0.21 | 4136 ± 175 (4254; 244) * | 1369 ± 86 (1392; 91) | 707 ± 16 (712; 27) | 710 ± 18 (715; 24) | |

| 0.42 | 3407 ± 198 (3389; 119) * | 1222 ± 58 (1230; 72) | 617 ± 14 (615; 10) | 640 ± 62 (631; 46) | |

| n-Pentanol | 0.105 | 2999 ± 206 (2939; 103) * | 1975 ± 106 (1967; 129) | 761 ± 31 (754; 20) | 752 ± 52 (737; 18) |

| 0.21 | 2829 ± 164 (2884; 172) * | 2116 ± 139 (2084; 1510) | 690 ± 15 (684; 15) | 679 ± 13 (680; 17) | |

| 0.42 | 2801 ± 159 (2741; 137) * | 1825 ± 55 (1819; 25) | 607 ± 17 (595; 30) | 579 ± 39 (567; 22) | |

| Acetonitrile | 0.105 | 3243 ± 361 (3353; 164) | 3249 ± 52 (3266; 49) | 794 ± 14 (787; 18) | 778 ± 11 (780; 18) |

| 0.21 | 3550 ± 110 (3577; 173) * | 2894 ± 51 (2872; 62) | 699 ± 20 (704; 30) | 705 ± 52 (683; 88) | |

| 0.42 | 3347 ± 188 (3254; 1420) * | 2576 ± 65 (2560; 92) | 603 ± 20 (601; 28) | 572 ± 13 (572; 16) | |

| DMSO | 0.105 | 3624 ± 242 (3650; 170) * | 1207 ± 46 (1197; 34) | 759 ± 52 (738; 26) | 754 ± 23 (761; 37) |

| 0.21 | 3921 ± 969 (3932; 663) * | 1200 ± 54 (1198; 71) | 708 ± 18 (705; 20) | 690 ± 19 (694; 15) | |

| 0.42 | 3641 ± 193 (3722; 172) * | 1072 ± 36 (1057; 46) | 625 ± 18 (631; 26) | 587 ± 20 (588; 12) | |

| Benzyl acetate | 0.105 | 3224 ± 144 (3246; 106) * | 2105 ± 131 (2116; 85) | 580 ± 17 (578; 26) | 551 ± 22 (560; 25) |

| 0.210 | 3125 ± 133 (3174; 171) * | 2144 ± 27 (2143; 29) | 689 ± 15 (681; 19) | 674 ± 14 (681; 13) | |

| 0.42 | 3173 ± 107 (3205; 124) * | 2017 ± 65 (2019; 87) | 580 ± 17 (578; 26) | 551 ± 22 (560; 25) | |

| Solvents that enhance light emission from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system | |||||

| Acetone | 0.105 | 3270 ± 96 (3243; 103) * | 4427 ± 135 (4454; 71) | 704 ± 17 (703; 20) | 715 ± 29 (711; 42) |

| 0.21 | 3015 ± 176 (2950; 197) * | 4174 ± 96 (4165; 110) | 681 ± 15 (682; 10) | 672 ± 19 (669; 20) | |

| 0.42 | 3240 ± 221 (3299; 271) * | 4179 ± 99 (4194; 96) | 639 ± 14 (637; 11) | 617 ± 14 (615; 21) | |

| Ethyl acetate | 0.105 | 3260 ± 184 (3196; 155) * | 5960 ± 196 (5932; 167) | 467 ± 20 (461; 33) | 463 ± 13 (459; 22) |

| 0.21 | 3528 ± 149 (3492; 148) * | 5377 ± 141 (5303; 193) | 710 ± 10 (714; 11) | 720 ± 5 (721; 5) | |

| 0.42 | 3043 ± 360 (3209; 500) * | 5280 ± 238 (5176; 3330 | 731 ± 18 (733; 27) | 702 ± 11 (705; 18) | |

| Amyl acetate | 0.105 | 3478 ± 222 (3439; 207) * | 4623 ± 213 (4651; 160) | 747 ± 18 (752; 24) | 749 ± 14 (750; 14) |

| 0.21 | 3057 ± 159 (3082; 135) * | 4153 ± 261 (4063; 380) | 736 ± 25 (731; 27) | 739 ± 18 (733; 26) | |

| 0.42 | 3125 ± 91 (3121; 66) * | 4193 ± 187 (4215; 98) | 595 ± 29 (600; 410 | 570 ± 18 (562; 19) | |

| Butyl butyrate | 0.105 | 3364 ± 117 (3406; 167) * | 6475 ± 462 (6372; 680) | 747 ± 18 (752; 24) | 749 ± 14 (750; 14) |

| 0.21 | 3315 ± 110 (3307; 163) * | 18,124 ± 1412 (18,633; 1751) | 727 ± 14 (727; 17) | 739 ± 28 (730; 17) | |

| 0.42 | 3303 ± 137 (3295; 204) * | 19,338 ± 738 (19,310; 761) | 686 ± 10 (687; 11) | 700 ± 21 (705; 20) | |

Table 2.

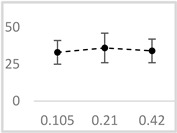

Inhibitory effect of selected organic solvents at final concentrations of 0.105 µmol/L, 0.21 µmol/L, and 0.42 µmol/L on UPE in 92.6 µmol/L Fe2+-185.2 µmol/L EGTA-2.6 mmol/L H2O2 system.

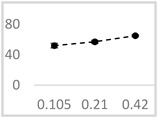

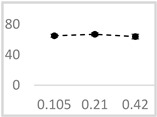

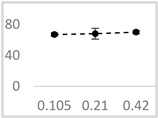

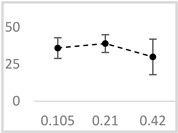

| Solvent | Chemical Structure | % Inhibition | Graph | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.105 µmol/L | 0.21 µmol/L | 0.42 µmol/L | |||

| Methanol |

|

62 ± 4 * (62; 2) | 69 ± 8 * (65; 9) | 63 ± 4 * (64; 3) |

|

| Ethanol |

|

52 ± 3 * (52; 3) | 57 ± 2 * (57; 20 | 65 ± 1 * (64; 2) |

|

| Propan-1-ol |

|

65 ± 2 * (66; 2) | 67 ± 2 * (66; 3) | 64 ± 3 * (64; 4) |

|

| n-Pentanol |

|

34 ± 6 * (32; 0) | 25 ± 5 * (26; 0) | 35 ± 2 * (32; 0) |

|

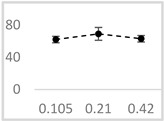

| Acetonitrile |

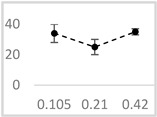

|

−1 ± 13 (2; 0) | 18 ± 3 * (19; 0) | 23 ± 5 * (21; 0) |

|

| DMSO |

|

67 ± 2 * (67; 1) | 68 ± 7 * (67; 5) | 70 ± 2 * (71; 3) |

|

| Benzyl acetate |

|

35 ± 8 * (35; 6) | 31 ± 3 * (31; 4) | 36 ± 4 * (37; 2) |

|

UPE—ultra-weak photon emission expressed in Relative Light Units (RLU). The tested solvent was mixed with EGTA and Fe2+, followed by the automatic injection of H2O2. The total light emission was then measured for 120 s. The results are presented as the mean and standard deviation (median; interquartile range) of the percentage inhibition of light emission, which was obtained from seven independent experiments. *—significant inhibition (p < 0.05) compared to the UPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system without the solvent.

The tested solvents were mixed with EGTA and Fe2+, followed by either automatic H2O2 or H2O injection. Total light emission was then measured for 120 s. The results are presented as the mean and standard deviation (and median and interquartile range) of the UPE (ultra-weak photon emission, expressed in Relative Light Units) obtained from 7 independent series of experiments. * indicates significant differences (p < 0.05) compared to the corresponding values for the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system with the solvent. The incomplete Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system with or without the appropriate solvent was used as a control.

2.1. Solvents That Inhibited Light Emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

Table 2 shows the solvents that suppressed UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. DMSO, methanol, ethanol, and propan-1-ol exhibited the strongest inhibitory effects on light emission. At the lowest tested concentration of 0.105 µmol/L, the inhibition ranged from 52 ± 3% for ethanol to 67 ± 2% for DMSO, with no significant increase observed at the concentration four times higher than that of the solvent (ethanol 65 ± 1% and DMSO 70 ± 2%) (Table 2). Benzyl acetate and n-pentanol were approximately half as effective (p < 0.05) at suppressing UPE in comparison to the four aforementioned solvents. Additionally, their inhibitory effects remained relatively unchanged across the concentration range of 0.105 µmol/L to 0.42 µmol/L. Acetonitrile at a concentration of 0.42 µmol/L was approximately 3 times less effective (p < 0.05) at inhibiting light emission than the strongest inhibitor. However, it was the only solvent that did not affect UPE at the lowest concentration of 0.105 µmol/L (Table 2).

2.2. Solvents That Enhanced Light Emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

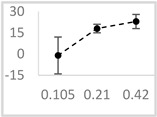

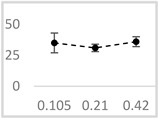

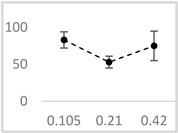

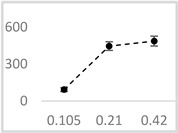

Butyl butyrate was the strongest enhancer of photon emission in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. At a concentration of 0.42 µmol/L, this solvent increased UPE by approximately fivefold (Table 3). The enhancing effect was concentration-dependent, with UPE increasing by only 1.93 times at the lower concentration of 0.105 µmol/L. The other solvents did not show a clear concentration-dependent effect. However, ethyl acetate exhibited a reduced enhancing effect at 0.21 µmol/L compared to 0.105 µmol/L and 0.42 µmol/L (p < 0.05) (Table 3). The remaining two solvents, acetone and amyl acetate, showed a moderate but consistent stimulation of UPE, with the mean enhancement not exceeding 40% at any tested concentration (Table 3).

Table 3.

Enhancing effect of selected solvents at final concentrations of 0.105 µmol/L, 0.21 µmol/L, and 0.42 µmol/L on UPE in 92.6 µmol/L Fe2+-185.2 µmol/L EGTA-2.6 mmol/L H2O2 system.

| Solvent | Chemical Structure | % Enhancement of UPE | Graph | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.105 µmol/L | 0.21 µmol/L | 0.42 µmol/L | |||

| Acetone |

|

36 ± 7 * (39; 8) | 39 ± 6 * (40; 5) | 30 ± 12 * (25; 14) |

|

| Ethyl acetate |

|

83 ± 11 * (84; 12) | 53 ± 8 * (52; 12) | 75 ± 20 * (75; 24) |

|

| Amyl acetate |

|

33 ± 8 * (35; 8) | 36 ± 10 * (40; 15) | 34 ± 8 * (37; 10) |

|

| Butyl butyrate |

|

93 ± 16 * (93; 12) | 446 ± 35 * (452; 40) | 487 ± 40 * (496; 53) |

|

UPE—ultra-weak photon emission expressed in Relative Light Units (RLU).

The tested solvent was mixed with EGTA and Fe2+, followed by the automatic injection of H2O2. The total light emission was then measured for 120 s. The results are presented as the mean and standard deviation (and median and interquartile range) of the percentage inhibition of light emission, which was obtained from seven independent experiments. * indicates significant inhibition (p < 0.05) compared to the UPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system without the solvent.

3. Discussion

3.1. Solvents That Inhibited Light Emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

Four of the seven solvents that inhibited UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system are aliphatic alcohols: methanol, ethanol, propan-1-ol, and n-pentanol. Methanol, ethanol, and propane-1-ol exhibited similar inhibitory effects on UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system, whereas n-pentanol was almost two-fold weaker in inhibiting •OH-dependent light emission across all the concentrations tested. Additionally, the percentage inhibition of UPE remained nearly constant regardless of the concentration for all four alcohols.

The reaction of aliphatic alcohols with •OH radicals involves hydrogen abstraction from both the hydroxyl (-OH) group and the aliphatic carbon chain that lacks the -OH group [22].

| R-OH + •OH → R-OH ∙∙∙ •OH (formation of the pre-reactive complex) (R=CH3, C2H5, C3H7) | (1) |

| R-OH ∙∙∙ •OH → R=O + H2O (hydrogen abstraction from -OH group) | (2) |

| R-OH ∙∙∙ •OH → R(-H)-OH + H2O (hydrogen abstraction from aliphatic carbon chain that lacks the -OH group) | (3) |

However, due to the high bond-dissociation energy of the hydroxyl O-H bond, the abstraction of hydrogen from an aliphatic carbon chain that lacks the -OH group by •OH radicals (reaction (3)) is preferred [23]. On the other hand, the formation of acetaldehyde in the course of ethanol oxidation by various systems generating •OH radicals [24] suggests that reaction (2)—hydrogen abstraction from the -OH group—may also occur as a result of the oxidative attack on ethanol (and potentially methanol) in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system.

Reaction (3) may result in the formation of unsaturated bonds between carbon atoms in the aliphatic chain of alcohols and carbon-centered radicals. These unsaturated bonds could be highly susceptible to further oxidative attack by •OH radicals through addition to the double bond [24]. In methanol, ethanol, and propanol, the rate of hydrogen abstraction by •OH radicals is the highest at the carbon atoms directly attached to the hydroxyl group, whereas, the hydrogen of the -OH group itself is less reactive [24]. The rate constant for the reaction of •OH radicals with alcohols was the highest for methanol, followed by ethanol and propanol [25]. The process of hydrogen abstraction by the •OH radical is a simple atom-transfer reaction in which the bond to the hydrogen atom is broken and a new bond to the oxygen atom of the OH radical is formed [26]. In the case of higher aliphatic alcohols, hydrogen atom abstraction can occur at any carbon atom (the energy barrier for hydrogen abstraction is similar and may result in the formation of various carbon-centered alcohol radicals (e.g., α-radical, β-radical)) [25,26]. This may be explained, for instance, by a similar energy barrier for •OH radical-induced abstraction of Hα (3.487 kcal/mol) and Hβ (8.029 kcal/mol) in ethanol, as well as abstraction of Hα (3.445 kcal/mol), Hβ (6.060 kcal/mol), and Hγ (8.463 kcal/mol) in propanol [26]. Although the bond-dissociation energy of the hydroxyl O-H bond is higher than that of the C-H bond, alkoxyl radicals can be formed in mixtures containing aliphatic alcohols and Fenton systems through the abstraction of hydrogen bonded to the oxygen atoms of the –OH groups [26]. The alcohol radicals can react with each other to give non-radical products [25]. Alcohols (e.g., methanol, ethanol, and propanol) can also react with the hydrogen generated during the regeneration of Fe2+ (Figure 1); however, the rate constants for this process are distinctly lower than those between •OH radicals and alcohols [25,27]. The formation of unsaturated bonds in the aliphatic chain of alcohols that are susceptible to oxidative attack by •OH radicals, the comparable bond-dissociation energy of C-H bonds, and the low reactivity of hydrogens in the -OH group may explain the similar inhibitory effects of methanol, ethanol, and propan-1-ol on UPE in the Fe²⁺-EGTA-H₂O₂ system across the tested concentration range of 0.105 µmol/L to 0.42 µmol/L.

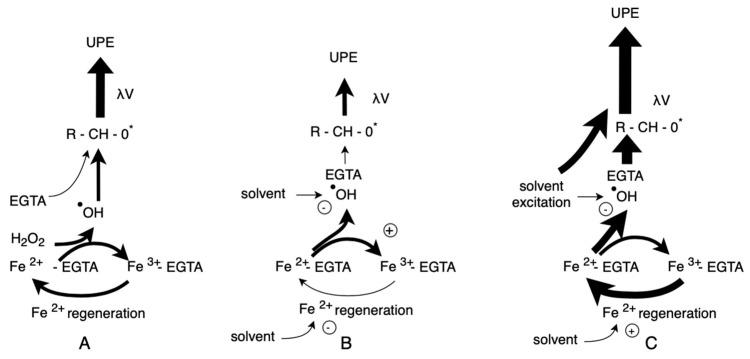

Figure 1.

Plausible mechanisms through which organic solvents affect UPE in the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 System. (A) Without the addition of solvent. In this case, the •OH radicals generated by the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 system attack ether bonds in the EGTA structure leading to the formation of products containing triplet-excited carbonyl groups (R-CH-O*), which results in light emission (UPE—ultra-weak photon emission). Simultaneously, Fe2⁺ is regenerated according to the following chemical equations: Fe3+-EGTA + O2•- → Fe2+-EGTA + O2 (1); H2O2 + Fe3+-EGTA → HO2• + H+ + Fe2+- EGTA (2); and HO2• + Fe3+-EGTA → O2 + H+ + Fe2+-EGTA (3). This regenerated Fe2⁺ contributes to the further production of •OH radicals and UPE. (B) With the addition of an organic solvent that inhibits UPE in the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 system. The solvent directly scavenges •OH radicals, thereby protecting the ether bonds in EGTA and inhibiting the formation of triplet-excited carbonyl-containing products, which reduces light emission. Some solvents (e.g., ethanol) may also inhibit Fe2⁺ regeneration (Equation (1)), further suppressing UPE. (C) With the addition of an organic solvent that enhances UPE in the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 system. The solvent accelerates Fe2⁺ regeneration. In some cases, such as with acetone, the solvent itself may emit light due to excitation to a triplet state. However, these solvents can simultaneously scavenge •OH radicals; therefore, the enhancing effect is observed when the rate of •OH radical generation, driven by accelerated Fe2⁺ regeneration, exceeds the loss of radicals due to the solvent’s scavenging activity.

In contrast, the higher molecular weight of n-pentanol and thus its lower molecular mobility and difficult access to the Fe2+-EGTA complex may result in a weaker inhibitory effect on light emission in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system.

Taking all the above into consideration, the studied aliphatic alcohols are recognized as effective scavengers of •OH radicals [28], which aligns with the results of our experiments. Ethanol has also been reported to strongly inhibit the reaction of Fe3+ with H2O2 [29], potentially leading to the regeneration of Fe2+ and the subsequent generation of •OH radicals as indicated by the following equations [30]:

| (4) |

| HO2• + Fe3+-EGTA → O2 + H+ + Fe2+-EGTA | (5) |

The inhibition of reaction (4) by ethanol, which may be due to the plausible formation of iron in a +5 oxidation state (FeO3+) [29], also results in the suppression of reaction (5). Both these processes may additionally contribute to the strong inhibition of UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. It cannot also be ruled out that other aliphatic alcohols (e.g., methanol, propan-1-ol, and n-pentanol) may exhibit a similar inhibitory effect on Fe2+ regeneration, thereby suppressing light emission in our modified Fenton system. However, further studies are required to confirm this additional inhibitory mechanism.

DMSO is well established as an excellent scavenger of •OH radicals [31] and the reaction between these two molecules leads to the formation of methanesulfinic acid [32,33]. Due to its small molecular size, DMSO can easily access the vicinity of the Fe2+- EGTA complex and compete with ether bonds for the •OH radicals, thereby inhibiting UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system.

Benzyl acetate, an acetate ester of benzyl alcohol, moderately inhibited photon emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system at all the concentrations tested. This suppression is likely due to •OH addition to the aromatic ring and subsequent cleavage of the benzene structure [34,35]. Although acetonitrile can react rapidly with •OH [36,37], little is known about the products of this reaction. It is assumed that the initial attack of •OH radicals on acetonitrile generates similar proportions of CH2CN and CH3C(OH)N [37]. On the other hand, some data suggest that in the presence of O2, these products may secondarily facilitate the formation of •OH radicals [37]. Nevertheless, the inhibitory effect of acetonitrile on the UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system decreased at lower concentrations and at the concentration of 0.105 µmol/L, no effect on light emission was observed. This indicates that antioxidant solutions in acetonitrile could be suitable for evaluating anti-•OH radicals activity, provided that the final concentration of acetonitrile in the reaction milieu does not exceed 0.105 µmol/L.

3.2. Solvents That Enhanced Light Emission from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

Acetone, ethyl acetate, amyl acetate, and butyl butyrate can all react with •OH radicals [38,39,40,41]. For instance, the reaction of acetone with •OH radicals primarily generates acetonyl radicals and, to a lesser extent, acetic acid (less than 1%) [42]. Therefore, one may expect that acetone and the other three esters would inhibit ultra-weak photon emission (UPE) in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Surprisingly, we observed the opposite effect: these solvents significantly enhanced light emission.

The bidirectional action of these compounds—which involves both scavenging •OH radicals and simultaneously enhancing their generation in the Fe²⁺-EGTA-H₂O₂ system—may explain the observed augmentation of UPE by the aforementioned solvents.

One likely mechanism responsible for this phenomenon is the acceleration of Fe²⁺ regeneration, allowing it to re-enter reactions that lead to the production of •OH radicals, and oxidative attack on the ether bonds in the EGTA backbone structure, resulting in the formation of products containing triplet-excited carbonyl groups and subsequent light emission [19]. This mechanism seems very plausible, particularly because our system had a 28-fold excess of H₂O₂ compared to Fe²⁺ ions. Consequently, each process of reducing Fe³⁺ to Fe²⁺ would enhance the emitted photon signal.

Acetone in combination with urea has been reported to reduce Fe3+ to Fe2+ under solvothermal conditions [43]. Moreover, acetone alone, as well as ethyl acetate in solutions exposed to light, has also been shown to reduce Fe3+ to Fe2+ [44,45]. While there is currently no data on the reduction of Fe³⁺ by amyl acetate or butyl butyrate, it cannot be ruled out that these esters may accelerate Fe2+ regeneration in the reaction mixture of the Fe2+- EGTA-H2O2 system.

Oxidation processes initiated by oxidants generated in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system (such as H2O2 and •OH radicals) could result in the formation of excited products derived from the tested solvents, potentially emitting light and enhancing UPE under the conditions of our experiments. This second mechanism of UPE augmentation appears to be the most likely physicochemical pathway for acetone that may be activated to the triplet state, leading to photon emission [46].

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Solutions

All chemicals used were of analytical grade. Sodium phosphate monobasic monohydrate (NaH2PO4 × H2O), sodium phosphate dibasic heptahydrate (Na2HPO4 × 7H2O), iron (II) sulfate heptahydrate (FeSO4 × 7H2O), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), ethylene glycol-bis (β-aminoethyl ether)-N, N, N′, N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), methanol, ethanol, acetone, ethyl acetate, propan-1-ol, n-pentanol, acetonitrile, isopentyl acetate, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). Benzyl acetate and n-butyl butyrate were obtained from Thermo Scientific (Kandel, Germany). A 30% H2O2 solution (w/w) was obtained from Chempur (Piekary Slaskie, Poland). Sterile deionized pyrogen-free water (freshly prepared, resistance > 18 MW/cm, HPLC H2O Purification System, USF Elga, Buckinghamshire, UK) was used throughout the study. Working aqueous solutions of 22.7 µmol/L, 11.35 µmol/L, and 5.675 µmol/L organic solvent (methanol, ethanol, acetone, ethyl acetate, propane-1-ol, n-pentanol, isopentyl acetate, benzyl acetate, and n-butyl butyrate) and aprotic solvent (acetonitrile, DMSO) were prepared before the assay. Other working solutions (5 mmol/L FeSO4,10 mmol/L EGTA, and 28 mmol/L H2O2) and 10 mmol/L phosphate buffer (pH = 6.6) were prepared as previously described [47].

4.2. Effect of Selected Solvents on Light Emission by the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 System

Chemical reactions in the 92.6 μmol/L Fe2+-185.2 μmol/L EGTA-2.6 mmol/L H2O2 system, which lead to ultraweak photon emission (UPE), were conducted in 10 mmol/L phosphate buffers (pH = 6.6) with and without the addition of organic solvents. UPE was measured using a multitube luminometer (AutoLumat Plus LB 953, Berthold, Germany), which was equipped with a Peltier-cooled photon counter covering a spectral range from 380 to 630 nm and operating at a temperature of 8 °C to ensure high sensitivity as well as a low and stable background noise levels.

Briefly, 20 μL of a 10 mmol/L EGTA solution was added to a tube (Lumi Vial Tube, 5 mL, 12 × 75 mm, Berthold Technologies, Bad Wildbad, Germany) containing 940 μL of a 10 mmol/L phosphate buffer (pH 6.6). Next, 20 μL of a 5 mmol/L FeSO4 solution was added, and after gentle mixing, the tube was placed in the luminometer and incubated for 10 min in the dark at 37 °C. Then, 100 μL of a 28 mmol/L H2O2 solution was added via an automatic dispenser, and the total light emission (expressed in Relative Light Units—RLU) was measured for 120 s. This measurement represented the baseline signal generated by the complete reaction system in the absence of a solvent. The final concentrations of FeSO4, EGTA, and H2O2 in the reaction mixture were 92.6 µmol/L, 185.2 µmol/L, and 2.6 mmol/L, respectively.

To evaluate the solvent’s effect on the UPE of the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 system, 20 µL of the working solvent solution was added immediately after the FeSO4 solution. The solvent was prepared at three initial concentrations: 22.7 µmol/L, 11.35 µmol/L, and 5.675 µmol/L in water. This resulted in three final solvent concentrations in the reaction mixture: 0.105 µmol/L, 0.21 µmol/L, and 0.42 µmol/L. The controls included an incomplete system (Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O, where H2O2 was not introduced) and an incomplete system with a solvent (Fe2⁺-EGTA-solvent- H2O, where H2O2 was also omitted) (Table 2). The number of control experiments was reduced compared to our previous study [21], as these experiments had previously excluded the possible interactions of the tested compounds with H2O2 alone (which did not produce any spurious light emission) and the contribution of singlet-oxygen decay to UPE in the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 system [48]. The percentage inhibition and enhancement of UPE by a given solvent were calculated using the following formulas:

| % inhibition = (UPE of Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2) − (UPE of Fe2⁺-EGTA-solvent-H2O2)/(UPE of Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O); |

| % enhancement = (UPE of Fe2⁺-EGTA-solvent-H2O2) − (UPE of Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2)/(UPE of Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O). |

The results were obtained from 7 series of separate experiments. In one set of experiments, all the samples (1–4; Table 4) were analyzed simultaneously to minimize inter-assay variability.

Table 4.

Design of experiments on the effect of various organic solvents on light emission in the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 system.

| Number | Sample | Working Solutions Added to Luminometer Tube (µL) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A PB |

B EGTA |

C FeSO4 |

D Solvent |

E H2O2 |

F H2O |

||

| 1 | Complete system | 940 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 2 | Complete system + solvent | 920 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 100 | 0 |

| 3 | Incomplete system | 940 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| 4 | Incomplete system + solvent | 920 | 20 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 100 |

The working solutions were mixed in the following order: 10 mM/L phosphate buffer (PB, pH 6.6); 10 mmol/L aqueous solution of ethylene glycol-bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N, N, N′, N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA); 5 mmol/L solution of FeSO4; and 22.7 µmol/L, 11.35 µmol/L, or 5.675 µmol/L solvent dissolved in water. The final concentrations of the solvent in the entire reaction mixture (1080 µL) were 0.105 µmol/L, 0.21 µmol/L, and 0.42 µmol/L. After gentle mixing, the tube was placed into the luminometer, incubated for 10 min at 37 °C in the dark, and then (28 mmol/L aqueous solution of H2O2) or (H2O) was automatically injected using a dispenser, and the total light emission was measured for 2 min.

4.3. Statistical Analyses

The results (UPE—total light emission) for the % inhibition or % enhancement by the solvent are expressed as relative light units (RLU) and shown as the means (and standard deviations) and medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). Comparisons between the UPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system and the light emission from the corresponding samples of the modified system (a complete system with solvent or incomplete system with and without solvent) were analyzed using the independent-sample (unpaired) t-test or the Mann–Whitney U test, depending on the data distribution, which was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov–Lilliefors test. The Brown–Forsythe test, used to analyze the equality of the group variances, was applied before the unpaired t-test. If the variances were unequal, Welch’s t-test was used instead of the standard t-test. Comparisons of the % inhibition or % enhancement of UPE caused by the evaluated organic solvents were analyzed in the same way. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

5. Conclusions

All the tested solvents (n = 11) affected the UPE of the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Seven of the solvents inhibited photon emission from the modified Fenton system, while four enhanced it. These effects were observed at all three tested concentrations (0.105 µmol/L, 0.21 µmol/L and 0.42 µmol/L). Notably, only acetonitrile at the lowest concentration of 0.105 µmol/L completely lost its inhibitory effect on UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. This suggests that stock solutions of the tested compounds in acetonitrile could be used under conditions where the final concentration of this solvent in the reaction milieu is below 0.105 µmol/L.

Figure 1 summarizes the inhibitory (Figure 1B) and enhancing (Figure 1C) effects of the tested solvents on UPE. Inhibition was primarily attributed to the direct scavenging of •OH radicals, while the enhancement of photon emission appeared to be due to accelerated regeneration of Fe2⁺ ions.

In a recent study, we examined the •OH-scavenging properties of various polyphenols using the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 system. Aqueous polyphenol solutions (without organic solvents) exhibited both pro- and antioxidant activities across a concentration range of 5–50 µmol/L [20]. Five of the seventeen tested polyphenols at a concentration of 5 µmol/L showed no significant effect on UPE in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system [20]. In contrast, 10 of the 11 tested organic solvents significantly modulated (either inhibited or enhanced) the •OH-dependent UPE at much lower concentrations (0.105 µmol/L)—almost 47 times lower than the polyphenol concentrations. This finding suggests that organic solvents are more potent modulators of •OH-induced reactions in the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system than some phytochemicals (e.g., polyphenols and vitamins) [19,21].

Furthermore, it can be concluded that the most suitable approach for evaluating the pro- or antioxidant activities of various compounds in the Fe2⁺-EGTA-H2O2 system, or in other modified Fenton systems, is to use aqueous solutions of these compounds. While aqueous polyphenol solutions may result in lower compound concentrations in the in vitro reaction mixture compared to organic solvent-based working solutions, these concentrations are closer to those found in human plasma, the portal circulation, and the intracellular fluid of enterocytes following fruit or vegetable consumption [48,49]. Thus, the use of aqueous solutions of potential antioxidants better reflects the in vivo conditions in human plasma.

Author Contributions

K.S. and D.N. conceived and designed the experiments. K.S., A.S. and A.W. conducted the experiments. K.S. and M.N. analyzed the data. K.S., M.N., A.S., A.W. and D.N. contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. K.S. and D.N. drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funder had no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by 503/1-079-01/503-11-001 Medical University Lodz.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Bergendi L., Benes L., Duracková Z., Ferencik M. Chemistry, physiology and pathology of free radicals. Life Sci. 1999;65:1865–1874. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(99)00439-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brieger K., Schiavone S., Miller F.J., Jr., Krause K.H. Reactive oxygen species: From health to disease. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2012;142:13659. doi: 10.4414/smw.2012.13659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Islam S., Mir A.R., Arfat M.Y., Khan F., Zaman M., Ali A., Moinuddin F. Structural and immunological characterisation of hydroxyl radical modified human IgG: Clinical correlation in rheumatoid arthritis. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018;194:194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2018.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jomova K., Vondrakova D., Lawson M., Valko M. Metals, oxidative stress and neurodegenerative disorders. Mol. Cell Biochem. 2010;345:91–104. doi: 10.1007/s11010-010-0563-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jomova K., Valko M. Advances in metal-induced oxidative stress and human disease. Toxicology. 2011;283:65–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng F.C., Jen J.F., Tsai T.H. Hydroxyl radical in living systems and its separation methods. J. Chromatogr. B Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2002;781:481–496. doi: 10.1016/S1570-0232(02)00620-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hajhashemi V., Vaseghi G., Pourfarzam M., Abdollahi A. Are antioxidants helpful for disease prevention? Res. Pharm. Sci. 2010;1:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y.J., Gan R.Y., Li S., Zhou Y., Li A.N., Xu D.P., Li H.B. Antioxidant phytochemicals for the prevention and treatment of chronic diseases. Molecules. 2015;20:21138–21156. doi: 10.3390/molecules201219753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Apak R., Calokerinos A., Gorinstein S., Segundo M.A., Hibbert D.B., Gülçin I., Çekiç S.D., Güçlü K., Özyürek M., Çelik S.E., et al. Methods to evaluate the scavenging activity of antioxidants toward reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (IUPAC Technical Report) Pure Appl. Chem. 2022;94:87–144. doi: 10.1515/pac-2020-0902. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Backa S., Jansbo K., Reitberger T. Detection of hydroxyl radicals by a chemiluminescence method—A critical review. Holzforschung. 1997;51:557–564. doi: 10.1515/hfsg.1997.51.6.557. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ran Y., Moursy M., Hider R.C., Cilibrizzi A. The colourimetric detection of the hydroxyl radical. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:4162. doi: 10.3390/ijms24044162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rutely C.B.C., Jean M.F., Walter Z.T., Xochitl D.B., Mika S. Towards reliable quantification of hydroxyl radicals in the Fenton reaction using chemical probes. RSC Adv. 2018;8:5321–5330. doi: 10.1039/C7RA13209C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernandez-Castro P., Vallejo M., San Roman M.F., Ortiz I. Insight on the fundamentals of advanced oxidation processes. Role and review of the determination methods of reactive oxygen species. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015;90:796–820. doi: 10.1002/jctb.4634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen X., Wang F., Hyun J.Y., Wei T., Qiang J., Ren X., Shin I., Yoon J. Recent progress in the development of fluorescent, luminescent and colourimetric probes for detection of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016;45:2976–3016. doi: 10.1039/C6CS00192K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen N., Wang T., Gan Q., Liu S., Wang L., Jinc B. Plant flavonoids: Classification, distribution, biosynthesis, and antioxidant activity. Food Chem. 2022;383:132531. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pandey K.B., Rizvi S.I. Plant polyphenols as dietary antioxidants in human health and disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2009;5:270–278. doi: 10.4161/oxim.2.5.9498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rana A., Samtiya M., Dhewa T., Mishra V., Aluko R.E. Health benefits of polyphenols: A concise review. J. Food. Biochem. 2022;46:e14264. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.14264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haminiuk C.W., Plata-Oviedo M.S., de Mattos G., Carpes S.T., Branco I.G. Extraction and quantification of phenolic acids and flavonols from Eugenia pyriformis using different solvents. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014;5:2862–2866. doi: 10.1007/s13197-012-0759-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowak M., Tryniszewski W., Sarniak A., Wlodarczyk A., Nowak P.J., Nowak D. Light emission from the Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system: Possible application for the determination of antioxidant activity of plant phenolics. Molecules. 2018;23:866. doi: 10.3390/molecules23040866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowak M., Tryniszewski W., Sarniak A., Wlodarczyk A., Nowak P.J., Nowak D. Concentration dependence of the anti- and pro-oxidant activity of polyphenols as evaluated with a light-emitting Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system. Molecules. 2022;27:3453. doi: 10.3390/molecules27113453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowak M., Tryniszewski W., Sarniak A., Wlodarczyk A., Nowak P.J., Nowak D. Effect of physiological concentrations of vitamin C on the inhibition of hydroxyl radical-induced light emission from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 and Fe3+-EGTA-H2O2 systems In vitro. Molecules. 2021;26:1993. doi: 10.3390/molecules26071993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jara-Toro R.A., Hernández F.J., Garavagno M.L.A., Taccone R.A., Pino G.A. Water Catalysis of the reaction between hydroxyl radicals and linear saturated alcohols (ethanol and n-propanol) at 294 K. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018;20:27885–27896. doi: 10.1039/C8CP05411H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feierman D.E., Winston G.W., Cederbaum A.I. Ethanol oxidation by hydroxyl radicals: Role of iron chelates, superoxide, and hydrogen peroxide. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 1985;9:95–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1985.tb05525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gligorovski S., Strekowski R., Barbati S., Vione D. Environmental implications of hydroxyl radicals ((•)OH) Chem. Rev. 2015;115:13051–13092. doi: 10.1021/cr500310b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alam M.S., Rao B.S.M., Janata E. •OH reactions with aliphatic alcohols: Evaluation of kinetics by direct optical absorption measurement. A pulse radiolysis study. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 2003;67:723–728. doi: 10.1016/S0969-806X(03)00310-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hatipoğlu A., Çinar Z. A QSAR study on the kinetics of the reactions of aliphatic alcohols with the photogenerated hydroxyl radicals. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 2003;631:189–207. doi: 10.1016/S0166-1280(03)00248-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alam M.S., Rao B.S.M., Janata E. A pulse radiolysis study of H atom reactions with aliphatic alcohols: Evaluation of kinetics by direct optical absorption measurement. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2001;3:2622. doi: 10.1039/b101385h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L., Li B., Dionysiou D.D., Chen B., Yang J., Li J. Overlooked formation of H2O2 during the hydroxyl radical-scavenging process when using alcohols as scavengers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022;56:3386–3396. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.1c03796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kremer M.L. Strong Inhibition of the Fe3+ + H2O2 reaction by ethanol: Evidence against the free radical theory. Prog. React. Kinet. Mech. 2017;42:397–413. doi: 10.3184/146867817X14954764850496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pan S., Cao B., Yuan D., Jiao T., Zhang Q., Tang S. Complexes of cupric ion and tartaric acid enhanced calcium peroxide Fenton-like reaction for metronidazole degradation. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2024;35:109185. doi: 10.1016/j.cclet.2023.109185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brömme H.J., Zühlke L., Silber R.E., Simm A. DCFH2 interactions with hydroxyl radicals and other oxidants—Influence of organic solvents. Exp. Gerontol. 2008;43:638–644. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2008.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steiner M.G., Babbs C.F. Quantitation of the hydroxyl radical by reaction with dimethyl sulfoxide. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1990;278:478–481. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(90)90288-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scaduto R.C., Jr. Oxidation of DMSO and methanesulfinic acid by the hydroxyl radical. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;18:271–277. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)E0139-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bernard F., Magneron I., Eyglunent G., Daële V., Wallington T.J., Hurley M.D., Mellouki A. Atmospheric chemistry of benzyl alcohol: Kinetics and mechanism of reaction with OH radicals. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013;47:3182–3189. doi: 10.1021/es304600z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan X.M., Schuchmann M.N., von Sonntag C. Oxidation of benzene by the OH radical. A product and pulse radiolysis study in oxygenated aqueous solution. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 1993;2:289–297. doi: 10.1039/p29930000289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hynes A.J., Wine P.H. Kinetics and mechanism of the reaction of hydroxyl radicals with acetonitrile under atmospheric conditions. J. Phys. Chem. 1991;95:1232–1241. doi: 10.1021/j100156a037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Galano A. Mechanism of OH radical reactions with HCN and CH3CN: OH regeneration in the presence of O2. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2007;111:5086–5091. doi: 10.1021/jp0708345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams D.C., O’Rji L.N., Daniel A. Stone: Kinetics of the reactions of OH radicals with selected acetates and other esters under simulated atmospheric conditions. Int. J. Chem. Kinet. 1993;25:539–548. doi: 10.1002/kin.550250704. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallington T.J., Dagaut P., Liu R., Kurylo M.J. The gas phase reactions of hydroxyl radicals with a series of esters over the temperature range 240–440 K. J. Chem. Kinet. 1988;20:177–186. doi: 10.1002/kin.550200210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piao M.J., Yoon W.J., Kang H.K., Yoo E.S., Koh Y.S., Kim D.S., Lee N.H., Hyun J.W. Protective effect of the ethyl acetate fraction of Sargassum muticum against ultraviolet B-irradiated damage in human keratinocytes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011;12:8146–8160. doi: 10.3390/ijms12118146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamath D., Mezyk S.P., Minakata D. Elucidating the elementary reaction pathways and kinetics of hydroxyl radical-induced acetone degradation in aqueous phase advanced oxidation processes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:7763–7774. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ranajit K., Talukdar R.K., Gierczak T., McCabe D.C., Ravishankara A.R. Reaction of hydroxyl radical with acetone. 2. products and reaction mechanism. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:5021–5032. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Belén F.A., Trobajo C., Piqué C., García J.R., Blanco J.A. From dihydrated iron(III) phosphate to monohydrated ammonium–iron(II) phosphate: Solvothermal reaction mediated by acetone–urea mixtures. J. Solid State Chem. 2012;196:458–464. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prasad M., Bavdekar P.R. The photo-reduction of ferric chloride in the presence of aqueous acetone and anhydrous ether. Proc. Indian Acad. Sci. 1943;18:373–382. doi: 10.1007/BF03051288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szafert S., Lis T., Drabent K., Sobota P. Photochemical reduction of iron trichloride in ethyl acetate: Synthesis, Mössbauer spectra and the crystal structure at 80 K of hexakis(ethyl acetate)iron(II) bis-tetrachloroironate(III) J. Chem. Crystallogr. 1994;24:197–202. doi: 10.1007/BF01672410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heicklen J., Noyes W.A., Jr. The photolysis and fluorescence of acetone and acetone-biacetyl mixtures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1959;81:3858–3863. doi: 10.1021/ja01524a016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sasak K., Nowak M., Wlodarczyk A., Sarniak A., Tryniszewski W., Nowak D. Light emission from Fe2+-EGTA-H2O2 system depends on the pH of the reaction milieu within the range that may occur in cells of the human body. Molecules. 2024;29:4014. doi: 10.3390/molecules29174014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manach C., Williamson G., Morand C., Scalbert A., Rémésy C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005;81:230S–242S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.1.230S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steensma A., Faassen-Peters M.A., Noteborn H.P., Rietjens I.M. Bioavailability of genistein and its glycoside genistin as measured in the portal vein of freely moving unanesthetized rats. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:8006–8012. doi: 10.1021/jf060783t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.