Abstract

Objectives

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common chronic condition that is often undiagnosed or diagnosed after many years of symptoms and has an impact on quality of life and several health factors. We estimated the Canadian national prevalence of OSA using a validated questionnaire and physical measurements in participants in the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA).

Methods

The method used individual risk estimation based upon the validated STOP-BANG scale developed for OSA. This stratified population sample spans Canada to provide regional estimates.

Results

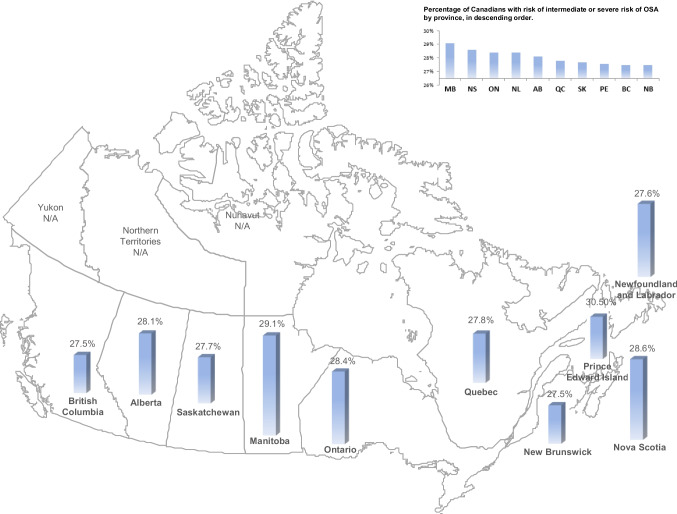

In this sample of adults aged 45 to 85 years old, the overall prevalence in 2015 of combined moderate and severe OSA in the 51,337 participants was 28.1% (95% confidence intervals, 27.8‒28.4). The regional prevalence varied statistically between Atlantic Canada and Western Canada (p < 0.001), although clinically the variations were limited. The provincial prevalence for moderate and severe OSA ranged from 27.5% (New Brunswick and British Columbia) to 29.1% (Manitoba). Body mass index (BMI) was the dominant determinant of the variance between provinces (β = 0.33, p < 0.001). Only 1.2% of participants had a clinical diagnosis of OSA.

Conclusion

The great majority (92.9%) of the participants at high risk of OSA were unrecognized and had no clinical diagnosis of OSA.

Keywords: Sleep, Obstructive sleep apnea, Epidemiology, Population health, Health care, STOP-BANG questionnaire, CLSA

Résumé

Objectifs

Le syndrome de l’apnée du sommeil (SAS) est une maladie chronique courante qui est souvent non diagnostiquée ou diagnostiquée plusieurs années après l’apparition de symptômes et qui a un impact sur la qualité de vie ainsi que plusieurs autres facteurs de santé. Nous avons estimé la prévalence nationale canadienne du SAS à l’aide d’un questionnaire validé et de mesures physiques chez les participants de l’Étude longitudinale canadienne sur le vieillissement (ÉLCV).

Méthodes

L’étude mesure l’estimation du risque individuel du SAS basée sur l’échelle validée STOP-BANG qui a été développée pour l’évaluation du SAS. Cet échantillon de population stratifié couvre tout le Canada et permet de fournir des estimations régionales.

Résultats

Dans cet échantillon d’adultes âgés de 45 à 85 ans, la prévalence globale du SAS modéré et sévère chez les 51 337 participants était de 28,1 % en 2015 (intervalles de confiance à 95 %: 27,8‒28,4). La prévalence régionale variait statistiquement entre le Canada atlantique et l’ouest du Canada (p < 0,001), bien que les variations cliniques soient limitées. La prévalence provinciale du SAS modéré et sévère variait entre 27,5 % (Nouveau-Brunswick et Colombie-Britannique) et 29,1 % (Manitoba). L’indice de masse corporelle représentait le facteur dominant de la variance entre les provinces (β = 0,33, p < 0,001). Seulement 1,2 % des participants avaient un diagnostic clinique du SAS.

Conclusion

La grande majorité (92,9 %) des participants présentant un risque élevé du SAS n’étaient pas identifiés auparavant et n’avaient aucun diagnostic clinique du SAS.

Mots-clés: Sommeil, apnée du sommeil, épidémiologie, santé de la population, soins de santé, questionnaire STOP-BANG, ÉLCV

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a chronic disorder characterized by repetitive collapse of the upper airway during sleep. Recurring respiratory events during sleep result in hypoxemia, arousals, and increased intrathoracic pressure (Morgenstern et al., 2014). The resulting changes in blood pressure and sympathetic overstimulation contribute to daytime hypertension and disturbance of glucose metabolism (Gonzaga et al., 2015). OSA is an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome disorder (Marin et al., 2005; Yenokyan et al., 2010). Severe OSA may be associated with increased mortality—particularly death from cardiovascular disease in older populations (Salari et al., 2022). Aging is also associated with oropharyngeal anatomy resulting in higher sleep apnea severity and upper airway collapsibility (D’Angelo et al., 2023). Furthermore, studies implicate OSA as a contributor to developing more severe COVID-19 (Chung et al., 2021; Najafi et al., 2021).

The prevalence across Canada of major chronic disorders such as hypertension, coronary artery disease, heart failure, obesity, and diabetes is well known. Trends are often published and have a crucial impact on public health policy and funding. The prevalence of OSA is rising worldwide in parallel with the global increase in obesity (Lyons et al., 2020). It is a treatable chronic disease that has an important impact on quality of life but is usually diagnosed after an average of 9 years of symptoms (Bailes et al., 2009). The phenotypes of OSA have been well documented and have varying impacts on long-term mortality if left untreated (Chen et al., 2020; Coughlin et al., 2020; Lyons et al., 2020; Testelmans et al., 2021).

There is a need to recognize strategies that are more successful at identifying and managing OSA (Gonzaga et al., 2015). Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has been shown to produce a significant reduction in blood pressure in relatively short-term randomized controlled trials. Severe OSA and hypertension are both associated with an increase in arterial stiffness, with cumulative effects when the two diseases coexist (Galerneau et al., 2020; Labarca et al., 2021; Salman et al., 2020; Tokunou & Ando, 2020). CPAP treatment has been shown to improve arterial stiffness in patients with OSA (Chalegre et al., 2020). Sleepiness is associated with longitudinal accumulation of brain amyloid in older subjects, contributing to cognitive decline and increased cerebral cortical thinning in cognitively normal late middle-aged and older adults (Mullins et al., 2020). This suggests that prevention or early intervention could be more effective for reducing the impacts of OSA on vascular aging (Drager et al., 2007; Jelic & Le Jemtel, 2008; McArdle et al., 2007; Yim-Yeh et al., 2010).

To better evaluate the burden of this chronic disease, we sought to estimate the prevalence and regional distribution of OSA in Canada. This was through the stratified population sample established by the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) in adults across the nation. The CLSA was designed to be a national, longitudinal research platform that includes 51,338 participants, aged 45–85 years at enrolment, from all ten Canadian provinces, and collects comprehensive data and biological samples that will support a wide variety of aging-related research questions (Raina et al., 2019). CLSA consists of two cohorts: The Comprehensive Cohort involves participants who were randomly selected within age/sex strata from among individuals residing within 25 km of a data collection site (or 50 km in lower density cities) in ten sites across Canada. Participants in the Comprehensive Cohort were interviewed in their homes with computer-assisted interview instruments and in data collection sites for additional comprehensive assessments (e.g., physical measures, biological samples). The Tracking Cohort consists of a randomly (within age/sex strata) selected sample from the ten Canadian provinces that completed telephone interviews only. Most items of the STOP-BANG instrument (see Modified STOP-BANG questionnaire section, below), originally validated against polysomnography with Canadian participants, were available in the CLSA dataset which we used to estimate the prevalence of OSA (Chung et al., 2016). This questionnaire has been well validated across different geographical regions and in diverse populations (Chen et al., 2021; Hwang et al., 2021; Pivetta et al., 2021).

Methods

Participants

The CLSA cohort recruited by 2015 a total of 51,337 persons (26,155 females, 25,182 males) across all ten provinces (Raina et al., 2009, 2019). The primary analysis of this study is based upon the comprehensive cohort consisting of 30,097 participants (15,320 women, 14,777 men). This cohort was established in seven provinces through face-to-face interviews, questionnaires, and visits to local sites for physical measurements: Victoria, Vancouver, Surrey (British Columbia); Calgary (Alberta); Winnipeg (Manitoba); Hamilton, Ottawa (Ontario); Montreal, Sherbrooke (Quebec); Halifax (Nova-Scotia); and St. John’s (Newfoundland and Labrador). For the three remaining provinces (Saskatchewan, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island), participants were among the 21,240 participants of the tracking cohort who answered mailed questionnaires. Data were not collected from the Canadian territories (Northwest Territories, Nunavut, and Yukon), which account for 0.3% of Canada’s population.

Measures

Modified STOP-BANG questionnaire

The STOP-BANG questionnaire (Chung et al., 2016) is a validated estimate of the risk of OSA based upon risk factors for OSA: snoring, tiredness, observed apnea during sleep, hypertension, body mass index (BMI) > 35 kg/m2, age over 50 years, neck circumference, and gender. The CLSA collected seven of the eight elements of the STOP-BANG questionnaire; neck circumference was not measured but is well known to be highly correlated to BMI. We used the simplified STOP-BAG scale which has been validated as an equivalent risk estimate for moderate and severe OSA (Waseem et al., 2022). Participants were classified into low (STOP-BAG score of 2 or lower), intermediate (score of 3 or 4), and high risk (score of 5 or greater).

Self-reported long-term physical condition diagnosed by a health professional

This item inquired about clinical diagnoses: “Do you have any other long-term physical or mental condition that has been diagnosed by a health professional? If yes, please specify.” This item was used to track the presence of a clinical diagnosis of OSA.

Centre for epidemiological studies depression scale (CES-D-10)

This measure of depressive symptoms (Zhang et al., 2012) has a range of 0 to 30, where a score of 10 or higher indicates the presence of significant depressive symptoms.

Tiredness

This was measured with the K10 scale. Participants were asked “About how often during the past 30 days did you feel tired out for no good reason — would you say all of the time, most of the time, some of the time, a little of the time, or none of the time?” The question was scored as positive if they answered as tired “all of the time” or “most of the time.” This was then factored into the calculation of risk for OSA. This was done because those who were the most tired would most likely be affected by OSA and potentially benefit from intervention.

Statistical analyses

The strategy for prevalence estimation is based upon over a decade of research validating the regional estimation of chronic disease when multiple important risk factors have been measured for the individuals in the population. This approach can estimate the regional prevalence of chronic diseases such as diabetes and chronic obstructive lung disease (Goodman, 2010; Jia et al., 2004; Srebotnjak et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2014, 2015). The individual risk of moderate or severe OSA was calculated for each participant (Waseem et al., 2022). The total regional prevalence was then calculated by averaging individual risk for all participants in the region.

For the 21,240 participants of the tracking cohort, questions about snoring, tiredness, and witnessed apnea were not collected. To estimate the prevalence of OSA, these missing questionnaire elements were imputed by regression from complete data available in neighbouring provinces. Multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) approach was used to impute the three missing values. The objective of MICE is to analyze missing data in a way that results in valid statistical inference and has become a basis for analytics for large data samples which frequently have missing values (Rubin, 1996). From the comprehensive cohort in neighbouring provinces, age, sex, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, and depression were used as predictors for imputation models. This approach consisted of three steps: replacing missing values with multiple sets of simulated values to complete the data (imputation step), applying standard analyses to each completed dataset (data analysis step), and adjusting the obtained parameter estimates for missing-data uncertainty (pooling step). The predictive mean matching method was selected for continuous variables and logistic regression for categorical variables.

Logistic regression analysis was used to examine the relative odds (OR) of exposures to known risk factors such as ethnicity, obesity, hypertension, diabetes, stroke, measures of depression, and alcohol consumption. The factors associated with a clinical diagnosis of OSA within those at intermediate or high risk of OSA were analyzed. The ordinal regression models were used to provide crude and adjusted OR and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

Analytic sampling weights were used to account for unequal probability of selection and to ensure the findings were generalizable to the Canadian population. Robust standard error estimates were computed by the Taylor linearization technique (Demnati & Rao, 2004) to account for multistage complex survey design effects such as stratification and clustering inherent within the study design. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics 28.0.

Results

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the CLSA sample. Of the 51,337 eligible participants, 580 (195 females, 385 males) reported a diagnosis of OSA. Only 1.1% (95%CI, 1.0‒1.2) of Canadians in this sample were diagnosed by their physicians. The rates of clinical diagnosis varied from 0.79% in Saskatchewan to 1.41% in Newfoundland and Labrador. There was a significant difference between provinces in the rate of diagnosis of OSA (p < 0.001). Of those already diagnosed with OSA, 50% (289/578) are treated for hypertension and 32.2% (186/578) are treated for diabetes.

Table 1.

Demographic and sleep parameters by province

| British Columbia | Alberta | Saskatchewan | Manitoba | Ontario | Quebec | New Brunswick | Nova Scotia | Prince Edward Island | Newfoundland and Labrador | Canada Mean value or percent (95%CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | 8874 | 5064 | 1392 | 4597 | 11,140 | 9672 | 1359 | 4630 | 1142 | 3467 | |

| Age, years (SD) | 63.10 (10.5) | 63.07 (10.4) | 62.89 (10.7) | 62.98 (10.3) | 63.10 (10.5) | 62.89 (10.4) | 62.81 (10.9) | 62.87 (10.2) | 62.45 (10.7) | 62.87 (10.4) | 62.98 [62.9–63.1] |

| Sex, n (% male) | 4370 (49.2) | 2463 (48.6) | 686 (49.3) | 2226 (48.4) | 5522 (49.6) | 4699 (48.6) | 646 (47.5) | 2315 (50.0) | 574 (50.3) | 1681 (48.5) | 49.1 [48.6–49.5] |

| BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 27.40 (5.2) | 27.73 (5.3) | 27.54 (5.4) | 28.39 (5.9) | 27.86 (5.3) | 27.69 (5.2) | 27.62 (5.4) | 28.27 (5.5) | 27.44 (5.2) | 28.30 (5.6) | 27.83 [27.8–27.9] |

| BMI (> 35), n (%) | 708 (7.98) | 431 (8.51) | 126 (9.05) | 526 (11.44) | 1081 (9.70) | 820 (8.48) | 122 (8.98) | 472 (10.19) | 112 (9.81) | 367 (10.59) | 8.2 [7.9–8.4] |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 3092 (35.0) | 1890 (37.5) | 539 (38.7) | 1784 (39.0) | 4184 (37.6) | 3703 (38.5) | 502 (37.0) | 1751 (38.2) | 428 (37.5) | 1329 (38.4) | 37.6 [37.1–38.0] |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1614 (18.2) | 791 (15.7) | 206 (14.8) | 839 (18.3) | 1921 (17.3) | 1574 (16.3) | 227 (16.7) | 870 (18.9) | 194 (17.0) | 626 (18.1) | 17.3 [17.0–17.6] |

| Depression, mean CES-D-10 score (SD) | 5.35 (4.7) | 5.21 (4.5) | 5.5 (4.7) | 5.45 (4.7) | 5.31 (4.7) | 5.48 (4.9) | 5.54 (4.8) | 5.19 (4.6) | 5.50 (4.8) | 5.11 (4.6) | 5.34 [5.30–5.38] |

| Snoring, n (% yes) | 2265 (25.5) | 1402 (27.7) | 389 (27.9) | 1430 (31.1) | 3181 (28.6) | 2577 (26.6) | 372 (27.4) | 1366 (29.5) | 342 (29.9) | 1034 (29.8) | 28.0 [27.7–28.3] |

| Tired, n (% yes) | 639 (7.2) | 365 (7.2) | 79 (5.7) | 352 (7.7) | 858 (7.7) | 667 (6.9) | 102 (7.5) | 293 (6.3) | 65 (5.7) | 220 (6.3) | 7.1 [6.8–7.4] |

| Observed apnea, n (% yes) | 1334 (15.0) | 762 (15.0) | 184 (13.2) | 702 (15.3) | 1684 (15.1) | 1420 (14.7) | 214 (15.7) | 725 (15.7) | 161 (14.1) | 493 (14.2) | 15.1 [14.8–15.4] |

| STOP-BAG Score, mean ± SD | 2.30 ± 1.21 | 2.33 ± 1.24 | 2.30 ± 1.21 | 2.42 ± 1.25 | 2.37 ± 1.23 | 2.32 ± 1.20 | 2.30 ± 1.19 | 2.38 ± 1.24 | 2.31 ± 1.18 | 2.37 ± 1.23 | 2.34 [2.31–2.37] |

| STOP-BAG ≤ 2, n (%) | 5396 (61.0) | 2968 (58.9) | 828 (59.9) | 2562 (56.0) | 6418 (57.9) | 5708 (59.3) | 807 (59.8) | 2665 (57.8) | 675 (59.5) | 2012 (58.3) | 58.8 [58.5–59.1] |

| STOP-BAG ≥ 5, n (%) | 421 (4.8) | 267 (5.3) | 59 (4.3) | 273 (6.0) | 593 (5.4) | 438 (4.6) | 56 (4.1) | 248 (5.4) | 38 (3.3) | 184 (5.3) | 5.0 [4.7–5.3] |

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median, and interquartile range and frequency (percentage), where appropriate

BMI, body mass index; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea

The national prevalence of moderate and severe OSA in Canada is 28.1% (95%CI, 27.8‒28.4). The regional prevalence estimates for risk vary between provinces (Fig. 1 and Table 2; F = 4.245, p < 0.001). Obesity, especially moderate-to-severe obesity (BMI > 35 kg/m2), is the dominant determinant of the variance between provinces (β = 0.33, p < 0.001).

Fig. 1.

CLSA map of Canada, with estimated prevalence of moderate or severe OSA

Table 2.

Frequency estimates of participants at high risk of intermediate or severe OSA, as well as not diagnosed with OSA, by province

| High risk of moderate or severe OSA, % (95%CI) | Diagnosed clinically with OSA, n (%) | High risk of OSA not yet diagnosed with OSA, n (% of population) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 27.5 (26.9–28.0) | 105 (1.2) | 531 (6.0) |

| Alberta | 28.1 (27.3–28.8) | 52 (1.0) | 344 (6.8) |

| Saskatchewan | 27.7 (26.3–29.1) | 11 (0.8) | 95 (6.8) |

| Manitoba | 29.1 (28.3–29.9) | 58 (1.3) | 351 (7.6) |

| Ontario | 28.4 (27.9–28.9) | 133 (1.8) | 764 (6.9) |

| Quebec | 27.8 (27.3–28.4) | 96 (1.0) | 584 (6.0) |

| New Brunswick | 27.5 (26.7–28.3) | 14 (1.0) | 91 (6.7) |

| Nova Scotia | 28.6 (27.2–30.0) | 51 (1.1) | 321 (6.9) |

| Prince Edward Island | 27.6 (26.1–29.2) | 11 (1.0) | 68 (6.0) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 28.4 (27.5–29.3) | 49 (1.4) | 249 (7.2) |

Values are expressed as frequency (percentage of provincial population sample)

OSA, obstructive sleep apnea

The categories of STOP-BAG risk reveal that the majority of participants across Canada who are at intermediate (11,627/20,017 = 58.1%) or high (3113/3586 = 86.8%) risk of OSA had hypertension. For these participants at intermediate risk of OSA, 23% experience hyperglycemia (4600/20,039) and 40.9% at higher risk of OSA have hyperglycemia (1469/3588). Furthermore, ordinal regression models predicting OSA risk (mild, intermediate, and severe) were significantly associated with diabetes and hypertension. The association of diabetes alone and OSA risk was also statistically significant after adjusting for confounding variables (p < 0.0001).

Moreover, we found that 92% of participants at high risk of OSA in Canada were unrecognized and not diagnosed. This led us to explore factors that may affect accessibility to sleep testing. To do this, we compared characteristics between participants who received a diagnosis of OSA and participants who are at intermediate or high risk of OSA but have no diagnosis of sleep apnea. Lower educational attainment was associated with being undiagnosed (Table 3). Younger age, obesity, and depressive symptoms seemed to favour a diagnosis of OSA being made. Rural vs. urban residence, ethnicity, and alcohol use were not associated with being undiagnosed. Most participants were Caucasian (97.2%), limiting the statistical power for analysis of ethnicity.

Table 3.

Clinical variables in relation to diagnosed participants with OSA among those at moderate or high risk of OSA

| Diagnosed, n (%) | Undiagnosed, n (%) | OR | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||||

| Female | 195 (33.6) | 3758 (28.3) | 2.07 | 1.74–2.46 | 0.005 |

| Male | 385 (66.4) | 9536 (71.7) | |||

| Age | |||||

| ≥ 65 | 206 (1.8) | 11,215 (98.2) | 0.81 | 0.45–1.45 | 0.56 |

| < 65 | 374 (3.0) | 12,078 (97.0) | |||

| Income (Canadian dollars) | |||||

| Less than $20,000 | 14 (4.2) | 736 (5.9) | 1.35 | 0.76–2.39 | 0.33 |

| $20,000–$50,000 | 74 (22.0) | 2942 (23.6) | |||

| $50,000–$100,000 | 123 (36.6) | 4535 (36.3) | |||

| $100,000–$150,000 | 74 (22.0) | 2346 (18.8) | |||

| Over $150,000 | 51 (15.2) | 1922 (15.4) | |||

| Location | |||||

| Rural | 31 (8.9) | 2393 (8.1) | 1.05 | 0.92–1.19 | 0.50 |

| Suburban | 17 (4.9) | 1195 (4.1) | |||

| Urban core | 300 (86.2) | 25,782 (87.8) | |||

| BMI | |||||

| BMI > 35 | 188 (4.6) | 3902 (95.4) | 3.92 | 2.11–7.27 | < 0.001 |

| BMI ≤ 35 | 386 (2.0) | 19,313 (98.0) | |||

| Depression (CES-D-10) | |||||

| CES-D-10 ≥ 10 | 145 (25.0) | 8191 (16.2) | 1.722 | 1.43–2.08 | < 0.001 |

| CES-D-10 < 10 | 435 (75.0) | 42,325 (83.8) | |||

| Alcohol | |||||

| 1 drink per month or less | 109 (33.9) | 9010 (31.0) | 1.02 | 0.99–1.07 | 0.43 |

| 2–4 drinks per month | 66 (20.5) | 6225 (21.4) | |||

| 2–3 drinks per week | 68 (21.1) | 6066 (20.9) | |||

| 4–7 drinks per week | 79 (24.5) | 7760 (26.7) | |||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Caucasian | 244 (98.8) | 8883 (97.1) | 0.56 | 0.27–1.18 | 0.13 |

| Asian | 2 (0.8) | 128 (1.4) | |||

| African | 1 (0.4) | 75 (0.8) | |||

| Hispanic | 0 | 40 (0.4) | |||

| Other | 0 | 25 (0.3) | |||

| Education | |||||

| No post-secondary education, or less than a bachelor degree | 134 (42.0) | 5453 (49.2) | 0.75 | 0.60–0.94 | 0.012 |

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 185 (58.0) | 5641 (50.8) |

Discussion

This is the first study to estimate the national prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea. Although 28.1% have moderate or severe OSA, only 1.1% of the Canadian sample was diagnosed with OSA, leaving an estimated 27% with unrecognized OSA. The provincial prevalence for moderate and severe OSA ranged from 27.5% (New Brunswick and British Columbia) to 29.1% (Manitoba). The major factor determining regional prevalence of OSA is obesity. This is in line with the recent population prevalence estimates elsewhere (Gottlieb & Punjabi, 2020; Lechat et al., 2022). Hypertension, impaired glucose tolerance, obesity, and depressive symptoms were associated with OSA or the risk of OSA.

Our findings suggest that OSA is significantly underdiagnosed in the Canadian population and the actual disease burden is much greater than expected. Underdiagnosis of OSA continues to be a concern; co-morbid diabetes, hypertension, and obesity are clearly associated with the risk of OSA. Very few patients actually had been diagnosed with OSA by their health care providers. This appears to be a result of concomitant social determinants of health such as older age and lower education.

The public health implications of our study are profound. Huyett and Bhattacharyya studied American adults with a diagnosis of a sleep disorder within the 2018 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (Huyett & Bhattacharyya, 2021). They showed that those with sleep disorders were associated with ethnicity, with a higher proportion with public insurance, and with more comorbid conditions. The authors subsequently cross-referenced the sleep disorder database to the consolidated expenditures file to assess differences in health care utilization among patients with and without sleep disorders. Their results showed that adults with sleep disorders were found to have twice the office visits (16.3 ± 0.8 vs 8.7 ± 0.3, p < 0.001), more emergency room visits (0.52 ± 0.03 vs 0.37 ± 0.02, p < 0.001), and more prescriptions (39.7 ± 1.2 vs 21.9 ± 0.4, p < 0.001) than those without sleep disorders. They estimated the overall yearly incremental health care costs of sleep disorders in the United States at approximately $94.9 billion.

Braley et al. (2018) demonstrated in the USA a significant gap in OSA assessment for older patients, highlighting the magnitude of OSA under-diagnosis and under-treatment within this population. They assessed the proportion of older Americans at-risk for OSA who underwent sleep studies and OSA treatment. Their results showed that increased OSA risk often exists among older Americans but is seldom investigated, contributing to its public health burden (Demnati & Rao, 2004).

The traditional indicators of OSA including snoring, drowsiness, and hypertension may predispose physicians to refer select patients for testing. We found that diabetes and metabolic syndrome may be considered in the decision for testing. The elderly, ethnic minorities, women, patients with psychiatric disorders, and patients of lower socio-economic status may require tailored approaches to diagnose OSA. For instance, traditional risk factors for OSA (snoring, sleepiness, and hypertension) are often overlooked as consequences of natural aging, and older patients with such symptoms may not be referred for sleep testing (Bailes et al., 2009; Braley et al., 2018; Gosselin et al., 2019; Tarasiuk et al., 2008; Young et al., 2002).

Each provincial government directs a provincial health care system with a large population burden of OSA to manage as a chronic disease. Future planning for the establishment of adequate resources now has a basis of evidence for each province. This study demonstrates an important nationwide need to improve access to care for patients with OSA. Recent American regional estimates of underdiagnosis of OSA where a population prevalence is estimated at 25% consider that similar social determinants of health are related to lack of diagnosis, and may, if remediated, improve population health to an important degree (Stansbury et al., 2022).

Limitations

The method used to determine prevalence was not explicit sleep testing of each participant but assessment of individual risk and then averaging of the risk across the large regional population samples. We used this strategy as it is valid for national and regional estimates with a validated risk function of measured risk factors. Local health authorities currently use regional high-quality health survey data to predict regional prevalences in planning health care programs and allocating resources. Model-based prevalence estimates based upon survey data including sleep behaviours and measures of obesity and hypertension are reliable and valid at the regional level for predicting chronic health outcomes. This approach has been validated against direct measurement of chronic diseases with good precision at the city-district level for diabetes (Congdon & Lloyd, 2010), hypertension (Wang et al., 2017), and chronic obstructive lung disease (Zhang et al., 2014). This method to estimate current regional prevalence remains feasible compared to the great expense of national surveys with polysomnography which may suffer from important night-to-night variation in sleep apnea (Lechat et al., 2022) and selection bias (Lutsey et al., 2016). This method is distinct from the use of the STOP-BANG questionnaire to stratify an individual’s risk of OSA into low, moderate, or high as previously published (Chung et al., 2016; Pivetta et al., 2021). Even if an individual is scored at the highest risk of OSA, the sensitivity and specificity are only 6% and 98% respectively but the overall diagnostic utility is very good (Raina et al., 2009). Our estimates for moderate to severe OSA are in keeping with recent studies of similar populations in the USA (Donovan & Kapur, 2016).

The overwhelming majority of participants of the CLSA were classified as Caucasian, which leaves samples of other ethnicities too small to draw any conclusions about ethnicity and lack of diagnosis of OSA, a relationship that has been established in the USA (Stanchina, 2022). Unfortunately, data were not collected from the northern territories or the First Nations. A recent study showed that in a First Nation community in Saskatchewan, mild, moderate, or severe OSA was present in 45.1% of participants (Dosman et al., 2022).

Conclusion

We found that the prevalence of moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea in Canada was high, largely driven by obesity, and that the individuals at higher risk of OSA often had hypertension or diabetes. The great majority of the participants at high risk of OSA were undiagnosed. We propose that accessibility to care of OSA needs to be improved in Canada.

Contributions to knowledge

What does this study add to existing knowledge?

This is the first study to estimate the national prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) which shows an estimated 27% Canadians are living with undiagnosed moderate or severe OSA.

The major factor determining regional prevalence of OSA is obesity.

What are the key implications for public health interventions, practice, or policy?

This study demonstrates an important nationwide need to improve access to care for patients with OSA.

Improving the identification of OSA will likely improve population health to an important degree.

Acknowledgements

This research was made possible using the data/biospecimens collected by the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA).

We would like to thank Nadia Gosselin for her invaluable contribution with respect to conceptualization, initial investigation of the database, and comments on the manuscript; Ernest Lo for his advice on the method of regional prevalence estimate; and Punam Pahwa for her invaluable guidance in the data analysis.

The opinions expressed in this manuscript are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging.

Author contributions

Rizzo and Baltzan: study design, data analysis, interpretation of results, preparation of the manuscript. Sirpal, Kaminska, and Chung: interpretation of results, preparation of the manuscript. Dosman: preparation of the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This was not an industry-supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. Funding for the Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) is provided by the Government of Canada through the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) under grant reference: LSA 94473 and the Canada Foundation for Innovation.

Availability of data and material

Data can be made available upon request.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This research has been conducted using the CLSA Comprehensive Baseline dataset version 4.0 and Tracking Baseline dataset version 3.7, under Application Number 1906008. The CLSA is led by Drs. Parminder Raina, Christina Wolfson, and Susan Kirkland.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dorrie Rizzo and Marc Baltzan contributed equally to this work.

References

- Bailes, S., Baltzan, M., Rizzo, D., Fichten, C. S., Grad, R., Wolkove, N., Creti, L., Amsel, R., & Libman, E. (2009). Sleep disorder symptoms are common and unspoken in Canadian general practice. Family Practice,26(4), 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braley, T. J., Dunietz, G. L., Chervin, R. D., Lisabeth, L. D., Skolarus, L. E., & Burke, J. F. (2018). Recognition and diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in older Americans. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society,66(7), 1296–1302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalegre, S. T., Lins-Filho, O. L., Lustosa, T. C., França, M. V., Couto, T. L., Drager, L. F., Lorenzi-Filho, G., Bittencourt, M. S., & Pedrosa, R. P. (2020). Impact of CPAP on arterial stiffness in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: A meta-analysis of randomized trials. Sleep and Breathing, 25(3), 1195–1202. 10.1007/s11325-020-02226-7 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chen, H., Eckert, D. J., van der Stelt, P. F., Guo, J., Ge, S., Emami, E., Almeida, F. R., & Huynh, N. T. (2020). Phenotypes of responders to mandibular advancement device therapy in obstructive sleep apnea patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews,49, 101229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L., Pivetta, B., Nagappa, M., Saripella, A., Islam, S., Englesakis, M., & Chung, F. (2021). Validation of the STOP-Bang questionnaire for screening of obstructive sleep apnea in the general population and commercial drivers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep and Breathing,25(4), 1741–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, F., Abdullah, H. R., & Liao, P. (2016). STOP-Bang questionnaire: A practical approach to screen for obstructive sleep apnea. Chest,149(3), 631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung, F., Waseem, R., Pham, C., Penzel, T., Han, F., Bjorvatn, B.,... Partinen, M., and International COVID Sleep Study (ICOSS) group. (2021). The association between high risk of sleep apnea, comorbidities, and risk of COVID-19: A population-based international harmonized study. Sleep Breath, 25(2), 849–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Congdon, P., & Lloyd, P. (2010). Estimating small area diabetes prevalence in the US using the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. Journal of Data Science,8(2), 235–252. [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin, K., Davies, G. M., & Gillespie, M. B. (2020). Phenotypes of obstructive sleep apnea. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America,53(3), 329–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, G. F., de Mello, A. A., Schorr, F., Gebrim, E., Fernandes, M., Lima, G. F., Grad, G. F., Yanagimori, M., Lorenzi-Filho, G., & Genta, P. R. (2023). Muscle and visceral fat infiltration: A potential mechanism to explain the worsening of obstructive sleep apnea with age. Sleep Medicine,104, 42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demnati, A., & Rao, J. (2004). Linearization variance estimators for survey data. Survey Methodology,30(1), 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, L. M., & Kapur, V. K. (2016). Prevalence and characteristics of central compared to obstructive sleep apnea: Analyses from the Sleep Heart Health study cohort. Sleep,39(7), 1353–1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosman, J. A., Karunanayake, C. P., Fenton, M., Ramsden, V. R., Seeseequasis, J., Skomro, R., Kirychuk, S., Rennie, D. C., McMullin, K., & Russell, B. P. (2022). Obesity, sex, snoring and severity of OSA in a First Nation community in Saskatchewan, Canada. Clocks & Sleep,4(1), 100–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drager, L. F., Bortolotto, L. A., Figueiredo, A. C., Silva, B. C., Krieger, E. M., & Lorenzi-Filho, G. (2007). Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, and their interaction on arterial stiffness and heart remodeling. Chest,131(5), 1379–1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galerneau, L.-M., Bailly, S., Borel, J.-C., Jullian-Desayes, I., Joyeux-Faure, M., Benmerad, M., Bonsignore, M. R., Tamisier, R., & Pépin, J.-L. (2020). Long-term variations of arterial stiffness in patients with obesity and obstructive sleep apnea treated with continuous positive airway pressure. PLoS ONE,15(8), e0236667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzaga, C., Bertolami, A., Bertolami, M., Amodeo, C., & Calhoun, D. (2015). Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Journal of Human Hypertension,29(12), 705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, M. S. (2010). Comparison of small-area analysis techniques for estimating prevalence by race. Preventing Chronic Disease, 7(2), A33. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gosselin, N., Baril, A.-A., Osorio, R. S., Kaminska, M., & Carrier, J. (2019). Obstructive sleep apnea and the risk of cognitive decline in older adults. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine,199(2), 142–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb, D. J., & Punjabi, N. M. (2020). Diagnosis and management of obstructive sleep apnea: A review. JAMA,323(14), 1389–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huyett, P., & Bhattacharyya, N. (2021). Incremental health care utilization and expenditures for sleep disorders in the United States. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine,17(10), 1981–1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, M., Zhang, K., Nagappa, M., Saripella, A., Englesakis, M., & Chung, F. (2021). Validation of the STOP-Bang questionnaire as a screening tool for obstructive sleep apnoea in patients with cardiovascular risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Respiratory Research,8(1), e000848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jelic, S., & Le Jemtel, T. H. (2008). Inflammation, oxidative stress, and the vascular endothelium in obstructive sleep apnea. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine,18(7), 253–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H., Muennig, P., & Borawski, E. (2004). Comparison of small-area analysis techniques for estimating county-level outcomes. American Journal of Preventive Medicine,26(5), 453–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labarca, G., Schmidt, A., Dreyse, J., Jorquera, J., Enos, D., Torres, G., & Barbe, F. (2021). Efficacy of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and resistant hypertension (RH): Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 58, 101446. 10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101446 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lechat, B., Naik, G., Reynolds, A., Aishah, A., Scott, H., Loffler, K. A., Vakulin, A., Escourrou, P., McEvoy, R. D., & Adams, R. J. (2022). Multinight prevalence, variability, and diagnostic misclassification of obstructive sleep apnea. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine,205(5), 563–569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lutsey, P. L., Norby, F. L., Gottesman, R. F., Mosley, T., MacLehose, R. F., Punjabi, N. M., Shahar, E., Jack, C. R., Jr., & Alonso, A. (2016). Sleep apnea, sleep duration and brain MRI markers of cerebral vascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC). PLoS ONE,11(7), e0158758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, M. M., Bhatt, N. Y., Pack, A. I., & Magalang, U. J. (2020). Global burden of sleep-disordered breathing and its implications. Respirology,25(7), 690–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin, J. M., Carrizo, S. J., Vicente, E., & Agusti, A. G. (2005). Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: An observational study. The Lancet,365(9464), 1046–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle, N., Hillman, D., Beilin, L., & Watts, G. (2007). Metabolic risk factors for vascular disease in obstructive sleep apnea: A matched controlled study. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine,175(2), 190–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern, M., Wang, J., Beatty, N., Batemarco, T., Sica, A. L., & Greenberg, H. (2014). Obstructive sleep apnea: An unexpected cause of insulin resistance and diabetes. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics,43(1), 187–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullins, A. E., Kam, K., Parekh, A., Bubu, O. M., Osorio, R. S., & Varga, A. W. (2020). Obstructive sleep apnea and its treatment in aging: Effects on Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers, cognition, brain structure and neurophysiology. Neurobiology of Disease, 145, 105054. 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.105054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Najafi, A., Sadeghniiat-Haghighi, K., Akbarpour, S., Samadi, S., Rahimi, B., & Alemohammad, Z. B. (2021). The effect of apnea management on novel coronavirus infection: A study on patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep Health,7(1), 14–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pivetta, B., Chen, L., Nagappa, M., Saripella, A., Waseem, R., Englesakis, M., & Chung, F. (2021). Use and performance of the STOP-Bang questionnaire for obstructive sleep apnea screening across geographic regions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Network Open,4(3), e211009–e211009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina, P., Wolfson, C., Kirkland, S., Griffith, L. E., Balion, C., Cossette, B., Dionne, I., Hofer, S., Hogan, D., & Van Den Heuvel, E. (2019). Cohort profile: The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). International Journal of Epidemiology,48(6), 1752–1753j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina, P. S., Wolfson, C., Kirkland, S. A., Griffith, L. E., Oremus, M., Patterson, C., Tuokko, H., Penning, M., Balion, C. M., & Hogan, D. (2009). The Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA). Canadian Journal on Aging,28(3), 221–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, D. B. (1996). Multiple imputation after 18+ years. Journal of the American Statistical Association,91(434), 473–489. [Google Scholar]

- Salari, N., Khazaie, H., Abolfathi, M., Ghasemi, H., Shabani, S., Rasoulpoor, S., Mohammadi, M., Rasoulpoor, S., & Khaledi-Paveh, B. (2022). The effect of obstructive sleep apnea on the increased risk of cardiovascular disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurological Sciences,43(1), 219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salman, L. A., Shulman, R., & Cohen, J. B. (2020). Obstructive sleep apnea, hypertension, and cardiovascular risk: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. Current Cardiology Reports,22(2), 1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srebotnjak, T., Mokdad, A. H., & Murray, C. J. (2010). A novel framework for validating and applying standardized small area measurement strategies. Population Health Metrics,8(1), 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanchina, M. L. (2022). Health inequities and racial disparity in obstructive sleep apnea diagnosis: A call for action. Annals of the American Thoracic Society, 19(2), 169–170. 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202108-984ED [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stansbury, R., Strollo, P., Pauly, N., Sharma, I., Schaaf, M., Aaron, A., & Feinberg, J. (2022). Underrecognition of sleep-disordered breathing and other common health conditions in the West Virginia Medicaid population: A driver of poor health outcomes. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine,18(3), 817–824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarasiuk, A., Greenberg-Dotan, S., Simon-Tuval, T., Oksenberg, A., & Reuveni, H. (2008). The effect of obstructive sleep apnea on morbidity and health care utilization of middle-aged and older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society,56(2), 247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testelmans, D., Spruit, M., Vrijsen, B., Sastry, M., Belge, C., Kalkanis, A., Gaffron, S., Wouters, E., & Buyse, B. (2021). Comorbidity clusters in patients with moderate-to-severe OSA. Sleep and Breathing, 26(1), 195–204. 10.1007/s11325-021-02390-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tokunou, T., & Ando, S.-i. (2020). Recent advances in the management of secondary hypertension—obstructive sleep apnea. Hypertension Research, 43(12), 1338–1343. 10.1038/s41440-020-0494-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y., Holt, J. B., Zhang, X., Lu, H., Shah, S. N., Dooley, D. P., Matthews, K. A., & Croft, J. B. (2017). Comparison of methods for estimating prevalence of chronic diseases and health behaviors for small geographic areas: Boston Validation Study, 2013. Preventing Chronic Disease,14, E99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waseem, R., Salama, Y., Baltzan, M., & Chung, F. (2022). Comparison of STOP-Bang and STOP-Bag questionnaires in stratifying risk of obstructive sleep apnea. Canadian Journal of Respiratory, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine, 6(6), 359–366. 10.1080/24745332.2022.2057883

- Yenokyan, D. J. G. G., Newman, A. B., O’Connor, G. T., Punjabi, N. M., Quan, S. F., Redline, S., Resnick, H. E., Tong, E. K., Diener-West, M., & Shahar, E. (2010). A prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: The Sleep Health Heart Study. Circulation,122(4), 352–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yim-Yeh, S., Rahangdale, S., Nguyen, A. T. D., Jordan, A. S., Novack, V., Veves, A., & Malhotra, A. (2010). Obstructive sleep apnea and aging effects on macrovascular and microcirculatory function. Sleep,33(9), 1177–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young, T., Shahar, E., Nieto, F. J., Redline, S., Newman, A. B., Gottlieb, D. J., Walsleben, J. A., Finn, L., Enright, P., & Samet, J. M. (2002). Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: The Sleep Heart Health Study. Archives of Internal Medicine,162(8), 893–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W., O’Brien, N., Forrest, J. I., Salters, K. A., Patterson, T. L., Montaner, J. S., Hogg, R. S., & Lima, V. D. (2012). Validating a Shortened Depression Scale (10 item CES-D) among HIV-positive people in British Columbia, Canada. Plos One,7(7), e40793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Holt, J. B., Lu, H., Wheaton, A. G., Ford, E. S., Greenlund, K. J., & Croft, J. B. (2014). Multilevel regression and poststratification for small-area estimation of population health outcomes: A case study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease prevalence using the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. American Journal of Epidemiology,179(8), 1025–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X., Holt, J. B., Yun, S., Lu, H., Greenlund, K. J., & Croft, J. B. (2015). Validation of multilevel regression and poststratification methodology for small area estimation of health indicators from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. American Journal of Epidemiology,182(2), 127–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be made available upon request.

Not applicable.