Henry Maudsley, doyen of 19th century British psychiatry, believed that people with epilepsy were particularly prone to violence and criminality,1 a view shared by many leading psychiatrists and neurologists today.2 Epilepsy is typically claimed to be about two to four times more common in prisoners than in the general population, but the epidemiological evidence cited to support this claim is of uncertain validity. Previous surveys of prisoners have involved unrepresentative populations, proxy measures (such as use of anticonvulsant drugs), and secondhand respondents (such as prison medical officers). To help clarify the evidence, we conducted a meta-analysis of available surveys based on personal clinical interviews in general prison populations.

Methods and results

We sought studies of the prevalence of epilepsy, fits, convulsion, or seizures in approximately general prison populations (that is, excluding studies of prisoners referred for neuropsychiatric assessment) reported between January 1966 and August 2001 by computer based searches (Embase, PsycINFO, Medline), scanning of relevant reference lists, and hand searching of forensic psychiatry journals and other relevant journals. We used combinations of keywords relating to epilepsy (for example, epilep*, seizure, fit, convulsion) and to prisoners (for example, inmate, sentenced, remand, detainee, felon). Eligible studies reported on an adult history of chronic epilepsy (defined as a condition characterised by two or more recurrent seizures, unprovoked by any immediately identifiable cause).w1-w7 Two investigators independently extracted the following data according to a fixed protocol: geographical location, year of survey, number of prisoners, sampling strategy, response rate, diagnostic criteria, mean age and sex of prisoners, and number of prisoners reporting a history of epilepsy in adult life. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion and by correspondence with authors of surveys. Calculation of confidence intervals and data synthesis involved standard methods, as previously described.3

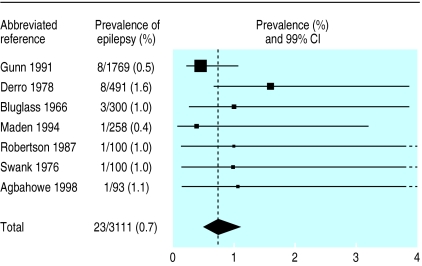

We identified seven relevant surveys (3111 prisoners).w1-w7 Reported sampling strategies included complete sampling of entire prisons (584 prisoners),w2,w7 stratified random sampling (2027),w1,w4 and inclusion of consecutive prisoners (500).w3,w5,w6 Six studies reported response rates in excess of 90%,w1-w6 and one study reported a response in excess of 75%.w7 All studies were based on clinical interviews (none was supplemented by neurological examination or other medical investigation). All respondents were sentenced inmates, the weighted mean age was 29 years, 90% were men, and 22% had been convicted of violent offences. Three surveys were conducted in the United Kingdom (2297 prisoners),w1,w3,w4 two in the United States (591),w2,w6 and one each in Canada (100)w5 and Nigeria (93).w7 Overall, 23 of the prisoners in these surveys reported a history of chronic epilepsy, yielding a prevalence rate of 0.7% (95% confidence interval 0.5% to 1.1%) (figure), and we found no significant heterogeneity among the seven surveys (χ26=8.3; P>0.10).

Comment

In contrast with claims widely published in standard texts and other sources,2 this synthesis of seven surveys involving more than 3000 participants in general prison populations indicates that only about 1% reported a history of chronic epilepsy. The prevalence rate in general populations is also approximately 1% for men aged 25-35 years, according to community based surveys that used definitions of epilepsy most comparable to those used in the studies reviewed here.4,5 Any publication bias in the reports contributing to this meta-analysis would probably tend to exaggerate the prevalence rates of epilepsy among prisoners, which reinforces our conclusion that the available epidemiological evidence provides no good support for the alleged link between epilepsy and criminality.

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Prevalence of epilepsy in prisoners found in seven surveys

Acknowledgments

The following investigators provided additional data: S Agbahowe, G Hannon, N Singleton, C Taylor. C Meux commented helpfully. P Appleby plotted the figure.

Footnotes

Funding: SF was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust. JD was supported by the Raymond and Beverly Sackler Research Award in the Medical Sciences.

Competing interests: None declared.

Additional references appear on bmj.com

References

- 1.Maudsley H. Body and mind. London: Macmillan; 1873. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toone B. Epilepsy. In: Gelder M, Lopez-Ibor J, Andreasen N, editors. The new Oxford textbook of psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 1153–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fazel S, Danesh J. Serious mental disorder among 23 000 prisoners: a systematic review of 62 surveys. Lancet. 2002;359:545–550. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07740-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sander G, Shorvon S. Epidemiology of the epilepsies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1996;61:433–443. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.61.5.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rowan A, Hyman H, French JH. The prevalence of epilepsy in a large heterogeneous urban population (The Bronx, New York, January 8, 1975) Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1976;101:281–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.