Abstract

Background

Isolated complex perianal fistulas, without luminal evidence of inflammatory bowel disease in the gastrointestinal tract, pose diagnostic and treatment dilemmas for gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons. For patients who develop recurrent complex fistulas, a presumptive diagnosis of Crohn’s disease may be made. It is unclear whether these cases of isolated perianal disease in the absence of luminal inflammation truly represent isolated severe cryptoglandular fistulas or rather an early presentation of Crohn’s disease. We aimed to investigate the clinical course and outcomes of patients with isolated complex perianal fistulas.

Methods

In this retrospective multicenter case series across 6 institutions in the United States, we report the clinical course of patients with isolated recurrent complex perianal fistulas, including their diagnostic evaluation, medical and surgical therapies, and clinical outcomes.

Results

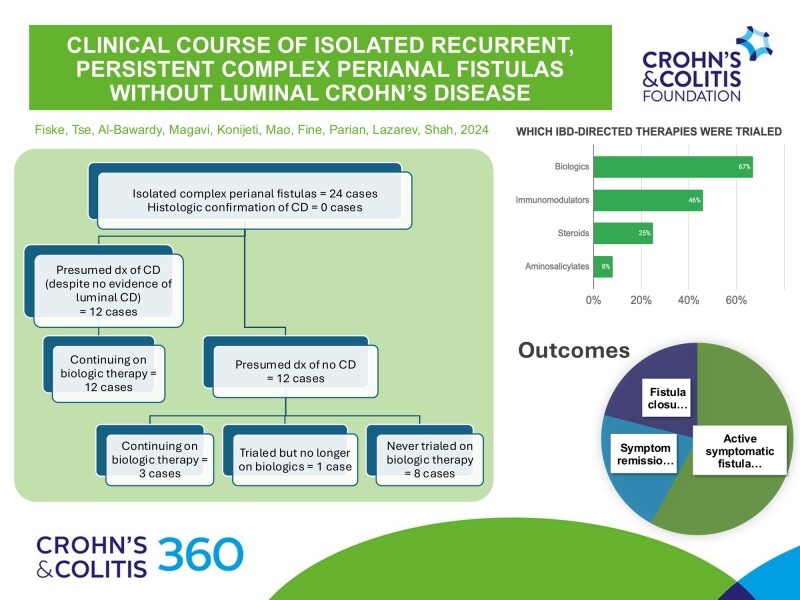

All patients (n = 24) required incision and drainage of perirectal abscesses. The majority received setons (n = 19, 79%), more intensive surgical interventions (n = 15, 62.5%, including fistulotomy/sphincterotomy, advancement flap, and ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract), antibiotics (n = 17, 71%), and biologic therapy (n = 16, 67%). Nine patients (37.5%) underwent a combined medical-surgical approach with biologics and intensive surgical intervention. Despite surgical and/or medical management, active symptomatic complex perianal fistulas persisted in 58% (n = 14) of patients at follow-up (median 5.5 years, interquartile range 2.5-10 years); symptom remission was achieved in 21% (n = 5), and fistula closure in 21% (n = 5).

Conclusions

These cases highlight a multidisciplinary and multimodal approach when treating isolated complex perianal fistulas and their propensity to persist despite the incorporation of advanced therapies.

Keywords: perianal fistula, isolated perianal Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Complex perianal fistulas are abnormal connections between the epithelial surfaces of the anal canal and the perianal area above the dentate line (intersphincteric, transsphincteric, extrasphincteric, or suprasphincteric) and may be associated with multiple external openings, may involve the rectum or vagina, and may be present with perianal abscess or anal stenosis.1 Based on data from population-based studies, between 20% and 25% of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD) typically develop perianal fistulas, though isolated perianal CD is rare.2,3 To add to the diagnostic dilemma, an initial presentation of isolated complex perianal fistula may precede the development of luminal CD. In a single-center study of 13 patients with isolated perianal Crohn’s disease, 4 (31%) had persistent fistulas after a median 10-year follow-up between 1980 and 2000, prior to the biologic era.4 Empirical evidence is lacking on the clinical course of isolated complex perianal fistulas in the 21st century, whereupon the introduction and widespread use of biologic therapies and advancement of surgical techniques changed the landscape of CD care.5,6 In this study, we aimed to investigate the clinical course and outcomes of patients with isolated complex perianal fistulas.

Materials and Methods

We herein describe a case series of the clinical course of 24 adults with isolated complex perianal fistula without luminal CD, treated with a combination of medical and surgical therapies from 2004 to 2024. These cases are uncommon and can be difficult to treat, so stand out to their gastroenterologists. In this case series, patients were identified by their providers by a variety of methods: ICD-10 code search (n = 9, 37.5%), physician recall (n = 9, 37.5%), or opportunity/convenience sampling (n = 6, 25%; the provider took note whenever patients with isolated perianal fistulas presented to clinic or endoscopy; they recorded the patients’ MRNs in a private list within the EMR as they were identified). Patients were subsequently evaluated via chart review and were determined to have an absence of luminal inflammation based on a combination of ileocolonoscopy, cross-sectional imaging, and capsule endoscopy.

Ethical Considerations

This study is original and has not been published previously. All authors significantly contributed to the design of the study, data analysis, and drafting and approved the final version of the manuscript. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of this study.

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (protocol #IRB00210084).

Results

Twenty-four adults (9 male and 15 female) with a median age of 33 years (interquartile range [IQR] 27.5-42 years) and no prior gastrointestinal (GI) diseases presented between 2004 and 2024 to 6 academic medical centers in the United States. On exam, each patient was found to have an isolated complex perianal fistula in the absence of any luminal findings of CD (Table 1). Presenting symptoms were perianal pain (n = 22, 92%), abdominal pain (n = 6, 25%), diarrhea (n = 6, 25%), and arthralgia (n = 4, 17%). None of the patients had evidence of inflammation on colonoscopy, colonic biopsies, or imaging via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). Eight patients (33%) underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), ruling out upper GI Crohn’s. Eleven patients (46%) underwent discrete small bowel imaging with either computed tomography enterography (CTE), magnetic resonance enterography (MRE), or video capsule endoscopy (VCE), with no evidence of luminal GI inflammation.

Table 1.

Summary table.

| PT # |

Initial presentation | Diagnostic evaluations | Subsequent diagnosis | Medical therapies attempted | Surgical procedures | Ultimate diagnosis and plan |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases with a current presumptive diagnosis of CD, despite lack of evidence of luminal CD: | ||||||

| Continuing on biologic therapy | ||||||

| (1) 34M |

Abdominal pain, diagnosed with sigmoid diverticulitis | Colonoscopy + bx CT MRI MRE EUA |

Refractory perianal fistula with abscess |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x16mo (continuing) Ustekinumab x10mo Tacrolimus Azathioprine Non-CD medical therapies: Metronidazole Ciprofloxacin Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid |

I&D Seton |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Isolated perianal disease in the setting of presumed CD Timeline: 13 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Chronic tx with chronic, cyclical abx (Ciprofloxacin or Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid) CD-directed therapy (Azathioprine + Infliximab; will consider Upadacitinib once approved by the FDA) Planning for surgical f/u |

| (2) 24F |

Perianal pain, diagnosed as perianal abscess with fistula; also presented with rheumatologic symptoms | Colonoscopy + bx MRI EUA |

Refractory perianal abscess; inflammatory arthropathy |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Adalimumab x46mo Infliximab x12mo (continuing) Azathioprine Non-CD medical therapies: Ciprofloxacin Metronidazole |

I&D Seton |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Presumed CD with perianal disease and inflammatory arthropathy Timeline: 9 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Infliximab + Azathioprine) Planning for surgical f/u |

| (3) 50F |

Diarrhea and rectal ulcers, presumed to have CD; also presented with rheumatologic symptoms | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) CT MRI EUA |

Refractory perianal fistula with abscess |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x39mo (continuing) Non-CD medical therapies: Colchicine Prednisone |

I&D Seton Perineal debridement Fistulotomy |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Presumed CD with perianal disease Timeline: 5 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Infliximab) |

| (4) 21F |

Ischiorectal abscess and posterior anal fissure, diagnosed with isolated perianal CD | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) MRI EUA Fecal calprotectin (within normal limits) |

Isolated perianal CD |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x16mo (continuing) Mercaptopurine Non-CD medical therapies: Ciprofloxacin Metronidazole |

I&D Seton Transanal advancement flap Penrose drain placement Foley catheter placed into perianal abscess cavity Diverting colostomy |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Presumed isolated perianal CD and lymphocytic colitis Timeline: 6 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Infliximab + Mercaptopurine) |

| (5) 34F |

Abdominal pain, constipation, and hematochezia, given presumptive diagnosis of unspecified IBD | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) US MRI MRE EUA Fecal calprotectin (mild elevation) |

Refractory perianal fistula with abscess |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Ustekinumab x9mo (continuing) Mesalamine Non-CD medical therapies: Trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole |

I&D Seton |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Presumed unspecified IBD with refractory perianal disease Timeline: 4.5 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Ustekinumab) |

| (6) 16F |

Isolated perianal fistula with abscess, presumed to have isolated perianal CD; family history of Crohn’s disease | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) MRI EUA Fecal calprotectin (elevated) |

Isolated perianal CD |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x64mo (continuing) Non-CD medical therapies: Ciprofloxacin Metronidazole |

I&D Seton |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Presumed isolated perianal CD Timeline: 5.5 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Infliximab) |

| (7) 36M |

Chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, and isolated perianal fistula with abscess presumed to have isolated perianal CD; also presented with spondyloarthropathy. | EGD Colonoscopy + bx MRE EUA |

Isolated perianal CD |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x16mo Ustekinumab x32mo (continuing) Azathioprine Non-CD medical therapies: Ciprofloxacin |

I&D Seton Diverting loop ileostomy LIFT Stem cell injections |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Presumed isolated perianal CD Timeline: 18 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Ustekinumab with stem cell injections) |

| (8) 43M |

Perianal fullness and pain, with episodes of drainage, diagnosed with recurrent perianal fistula | Colonoscopy + bx MRI EUA |

Isolated perianal CD |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x44mo (continuing) Non-CD medical therapies: Ciprofloxacin |

I&D Seton |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Presumed isolated perianal CD Timeline: 5 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Infliximab) Planning for surgical f/u |

| (9) 30F |

Pilonidal cyst with anal fistula | EGD Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) MRI Fecal calprotectin (mild elevation) |

Complex, recurrent perianal fistula |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x17mo Mercaptopurine Adalimumab x50mo (continuing) Non-CD medical therapies: Ciprofloxacin Metronidazole Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid Budesonide |

I&D Seton Cystectomy Fistulotomy |

Outcome: Fistula symptom remission Diagnosis: Presumed chronic fistulizing perianal CD; in steroid-free clinical and biochemical remission Timeline: 9 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Adalimumab) |

| (10) 27M |

Perianal abscess in the setting of long history of anal fissures; family history of Crohn’s disease | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) MRI MRE |

Isolated perianal CD |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x24mo Mercaptopurine x6mo |

I&D Seton Sphincterotomy |

Outcome: Fistula closure (clinical closure) Diagnosis: Presumed isolated perianal CD; no recurrence of fistula or fissure Timeline: 2.5 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Infliximab) |

| (11) 41F |

Perianal fistula in the setting of long history of abdominal pain and alternating diarrhea and constipation; family history of Crohn’s disease | EGD Capsule Flexible sigmoidoscopy Colonoscopy + bx (including rectal bx) CTE EUA |

Unclear dx |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Adalimumab x1mo (continuing) Non-CD medical therapies: Undefined abx |

I&D Seton |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Presumed isolated perianal CD; continues to develop recurrent fistulas Timeline: 1 year after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (adalimumab) Undefined abx |

| (12) 28F |

Perianal fistula with abscess developed after birth of first child, had previous history of recurrent abscesses; diagnosed with presumed isolated perianal CD | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) MRI MRE CT EUA Fecal calprotectin (within normal limits) |

Still considering as isolated perianal CD despite lack of luminal disease and normal fecal calprotectin |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Adalimumab x7mo Infliximab x41mo (continuing) Azathioprine Non-CD medical therapies: Amoxicillin-clavulanic acid |

I&D Seton Mallinckrodt drain Fistulotomy x2 |

Outcome: Fistula symptom remission Diagnosis: Presumed isolated perianal CD; MRI shows healing of fistula Timeline: 7 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Infliximab), planning to discontinue with close monitoring in the near future given MRI showing healing |

| Cases with no current presumptive diagnosis of CD | ||||||

| Continuing on biologic therapy | ||||||

| (13) 69M |

Recurrent diverticulitis with perianal abscess and fistula | EGD Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) CT CTE MRI MRE Fecal calprotectin (elevated) |

Ileitis with recurrent perianal disease |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Adalimumab x11mo (continuing) |

I&D Seton LIFT |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Ileitis with recurrent perianal disease, no luminal CD Timeline: 13 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Adalimumab) MRE pending |

| (14) 30F |

Perianal fistula; family history of Crohn’s disease | EGD Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) MRI Fecal calprotectin (within normal limits) |

Ileitis with recurrent perianal abscess |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Adalimumab x52mo (continuing) |

I&D FMT |

Outcome: Fistula symptom remission Diagnosis: Ileitis with recurrent perianal abscess, no luminal CD, complicated by recurrent Clostridioides difficile; clinically in symptom remission Timeline: 8 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Adalimumab) FMT |

| (15) 18F |

Perianal pain found to have perianal fistula w/ abscess, no other GI symptoms; some intermittent rheumatologic sx | EGD Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) Flexible sigmoidoscopy CT MRI MRE EUA Fecal calprotectin (within normal limits) |

Unclear dx |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Infliximab x53mo Non-CD medical therapies: Amoxicillin Hyperbaric oxygen |

I&D Seton Mushroom drain Fistulotomy |

Outcome: Fistula symptom remission Diagnosis: Isolated perianal disease Timeline: 5.5 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: CD-directed therapy (Infliximab) |

| Trialed but no longer on biologic therapy | ||||||

| (16) 39F |

Painful perianal mass, presumed to be an abscess or hemorrhoids | Flexible sigmoidoscopy Colonoscopy + bx (including rectal bx) MRI EUA |

Refractory perirectal and rectovaginal fistula with abscess (diagnosed following childbirth via cesarean section, not vaginal delivery) |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Adalimumab x9mo Methotrexate Non-CD medical therapies: Ciprofloxacin Metronidazole Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid Prednisone |

I&D Seton Fistulectomy + sphincterotomy Diverting sigmoid colostomy Fistulotomy |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Do not suspect CD; nonhealing cryptoglandular anal fistula c/b surgery Timeline: 3 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Discontinued CD therapy given lack of clinical improvement; off all medical tx Planning for surgical f/u with consideration of transperitoneal repair vs clinical trial of stem cell injection |

| Never trialed on biologic therapy | ||||||

| (17) 43M |

Painful perianal mass, presumed to be a rectal abscess | Colonoscopy + bx MRI EUA |

Refractory perianal abscess |

Non-CD medical therapies:

Amoxicillin-Clavulanic acid |

I&D |

Outcome: Fistula symptom remission Diagnosis: Isolated cryptoglandular abscess with proctitis and internal hemorrhoids Timeline: 2.5 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: No need for chronic antibiotics; off all medical tx Sitz baths and Preparation H as needed If symptoms worsen will plan for surgical f/u |

| (18) 28F |

Perianal abscess and fistula in ano in the setting of lifelong diarrheal illness and known lymphocytic colitis, concern for CD; family history of ulcerative colitis | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) CT MRI EUA Fecal calprotectin (mild elevation) |

Microscopic colitis with refractory perianal fistula with abscess |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Balsalazide Mesalamine Non-CD medical therapies: Amitriptyline Bismuth Subsalicylate Budesonide CBD oil |

I&D Seton Collagen plug placement Fibrin glue Fistulotomy Cystoscopy + laser lithotripsy Stem cell injection |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Microscopic colitis Timeline: 13 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Continuing mesenchymal stem cell injections as part of clinical trial |

| (19) 32M |

Perianal fistula with drainage; family history of ulcerative colitis | EGD Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) VCE MRE EUA Fecal lactoferrin (mild elevation) |

Refractory perianal fistula with abscess |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Methotrexate Non-CD medical therapies: Budesonide |

I&D Seton Fistulotomy Advancement flap procedure LIFT |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Refractory perianal dz Timeline: 12 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Budesonide taper with plan to start CD-directed therapy (anti-TNF combination therapy) Patient was unfortunately lost to follow-up |

| (20) 35F |

IBS, rectal pain and perianal drainage | EGD Flexible sigmoidoscopy Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) VCE MRI EUA Fecal calprotectin (within normal limits) |

Complex perianal fistula |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Methotrexate Non-CD medical therapies: Ciprofloxacin Metronidazole Budesonide |

I&D Seton Endorectal advancement flap Fistulotomy |

Outcome: Fistula closure (clinical closure) Diagnosis: Isolated perianal disease; status post successful surgery with closure of fistula Timeline: 11 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Not on treatment |

| (21) 59F |

Pilonidal cyst, found to have 2 draining perianal fistulas; family history of Crohn’s disease | Capsule Flexible sigmoidoscopy Colonoscopy + bx (including rectal bx) MRI EUA |

Isolated perianal CD |

Biologics, aminosalicylates, and immunomodulators:

Mercaptopurine x6-9mo |

I&D Fistulotomy |

Outcome: Fistula closure (clinical + radiologic closure) Diagnosis: Cryptoglandular fistula, no luminal CD; no further drainage, fistulas closed Timeline: 1.5 years after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Not on treatment |

| (22) 44M |

Recurrent rectal abscess | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) CT MRI MRE EUA Fecal calprotectin (elevated) |

Unclear dx |

Non-CD medical therapies:

Ciprofloxacin Metronidazole |

I&D Seton Endoanal advancement flap |

Outcome: Fistula closure (clinical and radiologic closure) Diagnosis: Cryptoglandular fistula, no luminal CD; abscess resolved w/o fistula Timeline: 1 year after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Not on treatment |

| (23) 22M |

Perirectal abscess | Colonoscopy + bx MRI EUA |

Unclear dx |

Non-CD medical therapies:

Undefined abx |

I&D |

Outcome: Fistula closure (clinical closure) Diagnosis: Cryptoglandular fistula, no luminal CD; abscess resolved w/o fistula Timeline: 1 year after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Not on treatment |

| (24) 28F |

Perianal abscess in the setting of abdominal pain and intermittent diarrhea | Colonoscopy + bx (including ileal and rectal bx) MRI EUA |

Unclear dx |

Non-CD medical therapies:

Undefined abx |

I&D Fistulotomy + marsupialization |

Outcome: Active perianal fistula Diagnosis: Cryptoglandular fistula, no luminal CD; persistent fistula Timeline: 1 year after initial presentation Treatment Plan: Undefined abx |

Abbreviations: Bx, biopsies; C/B, complicated by; CD, Crohn’s disease; EUA, exam under anesthesia; F, female; FMT, fecal microbiota transplantation; F/U, follow-up; I&D, incision and drainage; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; LIFT, ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract; M, male; MRE, magnetic resonance elastography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; VCE, video capsule endoscopy.

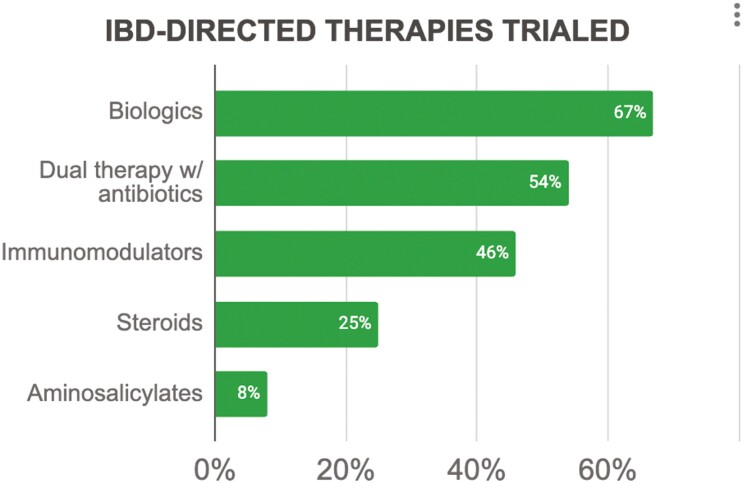

All patients received medical therapy, with just over half receiving a combination of antibiotics and CD-directed therapies (n = 13, 54%), 17% receiving antibiotics alone (n = 4), and 29% receiving CD-directed therapies alone (n = 7). The most common antibiotics used were ciprofloxacin (n = 10, 42%), metronidazole (n = 8, 33%), and amoxicillin/amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (n = 6, 25%) (Table 1). Crohn’s disease-directed therapies (Figure 1) included biologics (n = 16, 67%; dual therapy with antibiotics: n = 13, 54%), immunomodulators (n = 11, 46%), and aminosalicylates (n = 2, 8%); steroids were used in 25% (n = 6) (Table 1). Biologic therapy was continued for a mean of 17 months (range 1-64 months), and included infliximab (n = 11, 46%; median 24 months, IQR 16-44 months), adalimumab (n = 7, 29%; median 11 months, IQR 7-50 months), and ustekinumab (n = 3, 12.5%; median 10 months, IQR 9.5-21 months). Combination therapy with biologics and immunomodulators was used for 33% (n = 8) of the patients.

Figure 1.

The IBD-directed therapies which were trialed.

All patients had exam under anesthesia (EUA) with incision and drainage (I&D) of perirectal abscesses. Setons were placed in 79% (n = 19) of patients. More intensive surgical interventions were pursued in 62.5% (n = 15) of patients, with nearly half of all patients (n = 10, 42%) undergoing fistulotomy, while < 20% underwent advancement flap (n = 4, 17%) or ligation of the intersphincteric fistula tract (LIFT) (n = 3, 12.5%) (Table 1). Two patients (8%) were trialed on stem cell therapy via injection. Overall, 9 patients (37.5%) had a combined medical-surgical approach, undergoing treatment with both biologics and more intensive surgical interventions.

We examined the proportion of patients with active perianal fistula (persistent perianal drainage and/or recurrent abscess), fistula symptom remission (cessation of drainage and no abscess) and fistula closure (clinical and/or radiological closure of the fistula tract) on follow-up. Despite surgical and medical management, active perianal fistula was noted in 58% (n = 14) of patients after a median of 5.5 years (range 1-18 years, IQR 2.5-10 years). Fistula symptom remission was achieved in 21% (n = 5), and full fistula closure in 21% (n = 5; all 5 with fistula closure on clinical exam, and 2 of the 5 with confirmed radiologic closure). Of the 10 patients who achieved symptom remission or fistula closure (Table 1), 70% (n = 7) had undergone more definitive surgical closure with fistulotomy or sphincterotomy (n = 6) or advancement flap (n = 2). Half (n = 5, 50%) had been treated with biologic therapy throughout the duration of the follow-up period; 40% (n = 4) had combination therapy with both biologics and more intensive surgical intervention.

Among the 9 patients who had been treated with a combined approach of biologics and intensive surgical interventions, 44% (n = 4) achieved fistula symptom remission (n = 3) or fistula closure (n = 1). Of the 15 patients who underwent more intensive surgical interventions, 47% (n = 7) achieved fistula symptom remission (n = 3) or fistula closure (n = 4). For the 16 patients trialed on biologics, 15 (94%) continued biological treatment at the end of the follow-up period, though only 5 (31%) achieved fistula symptom remission (n = 4) or fistula closure (n = 1). Of those 5 patients, 3 had success with infliximab and 2 with adalimumab; all 5 are continuing with biologic monotherapy. Eight patients were never trialed on biologics; of these patients, 3 continue to have active perianal fistula, 4 had successful surgeries resulting in fistula closure, and 1 is in symptomatic remission.

While 50% (n = 12) of the patients currently carry a presumptive diagnosis of CD (ie, presumed isolated perianal CD with complex fistula; some labeled with CD for obtaining prior authorization to use biologics), none to date have histologic confirmation of CD. Of the other 12 patients without a presumed CD diagnosis, 2 (8% of the total) were found to have persistent nonspecific ileitis without clear histologic evidence of CD. Although neither of these 2 patients is currently suspected to have CD, both are being continued on biologic therapy. While ileitis is often caused by CD, there are numerous mimickers that ought to be considered in patients without histologic confirmation of CD. Ileitis may be secondary to infectious disease, vasculitis, infiltrative disorders, ischemia, malignancy, or medications, among others.

Discussion

Isolated perianal disease describes complex perianal fistulas in the absence of the luminal inflammation characteristically found in CD. Etiologies of isolated complex perianal fistulas ruled out for the patients in this study, include hidradenitis suppurativa, tuberculosis, actinomycosis, lymphogranuloma venereum, HIV, diverticulitis, postoperative fistula, trauma associated with childbirth, pelvic malignancy or subsequent irradiation therapy, and cryptoglandular abscess.7,8 Cryptoglandular abscesses are formed when there is impaired drainage of anal glands, leading to infection and formation of perianal abscesses. If abscesses are incompletely drained, then fistulas form.8 These fistulas, occurring in the absence of an underlying disease process, are typically simple fistulas (singular, transient, and low-lying). Recurrent complex fistulas are often presumed to be perianal CD and therefore may end up being treated with biologic therapy.

A diagnostic dilemma remains as to whether isolated perianal disease represents severe cryptoglandular fistula or CD (either an isolated perianal phenotype or an early manifestation prior to luminal disease).9 More than a third of patients with small bowel CD develop perianal symptoms before overt luminal disease.10–12 In a population-based cohort study of 85 CD patients with perianal or rectovaginal fistulas, 40% of patients developed their first fistula before or at the time of initial diagnosis of CD.13

For patients newly presenting with fistulas, diagnostic evaluation encompasses radiographic studies and direct visualization techniques. These tools may be employed to further evaluate the fistula (eg, EUA, proctosigmoidoscopy, or endoscopic anorectal ultrasound [US]), examine for luminal inflammation (eg, VCE), or both (eg, CT scan or pelvic MRI with contrast). Video capsule endoscopy can be a useful tool to identify mild small bowel disease that was not picked up on CT or MR.10 In a case series of 25 patients with persistent perianal disease without evidence of inflammation on colonoscopy, VCE revealed 24% of patients had aphthous ulcerations, linear ulcers, and circumferential ulcers indicative of active CD.10 Exam under anesthesia is another invaluable tool for the physician, with a diagnostic accuracy of 90% for fistulizing perianal CD.2 Exam under anesthesia allows for simultaneous surgical treatments, such as abscess I&D, seton placement, fistulotomy, fistulectomy, and as a last resort, proctectomy or colectomy.

Perianal fistulas are treated medically and surgically. In a year-long study of 22 patients with isolated perianal disease and 44 with perianal CD, treatment with tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-antagonists resulted in fistula healing in 43% of patients with perianal CD and 19% of patients with isolated perianal disease.9 This corresponds to the 31% response rate to biologics in our present case series of patients with isolated perianal disease. The use of steroids in patients without a clear diagnosis of luminal CD is not recommended; in fact, corticosteroids have been shown to decrease fistula healing.14 While treatment options for perianal fistulas are varied, relapse is common; in CD patients, data has shown that only 1/3rd of patients achieve remission of their fistulas.4,15

Conclusions

This case series underscores the difficulty of managing isolated perianal fistulas and highlights the importance of considering a multimodal approach to treatment. While anti-TNF agents did not consistently result in fistula symptom remission or fistula closure, the findings from this case series suggest that their incorporation into the patient’s treatment regimen may be critical in achieving eventual remission. There were several limitations to this study. The small sample size (n = 24) naturally limits the generalizability of our findings. Given the rarity of isolated perianal fistulas, each patient in this study was memorable and stood out easily to the referring gastroenterologist. However, 37.5% of the patients were identified from provider memory alone; the nature of this method of patient identification can result in a recall/selection bias. The absence of luminal inflammation was determined via ileocolonoscopy, cross-sectional imaging, and capsule endoscopy; as this was a retrospective case series, examinations were not uniform across patients within this study. We cannot exclude the possibility of future development of luminal CD in this case series, though on repeat evaluations (median of 5.5 years [IQR 2.5-10 years]) none of the patients had yet to develop luminal disease. Of note, however, 15 of the patients discussed have been maintained on biologic therapy, which could be a factor in their disease control and the continued absence of luminal findings. Additionally, not all patients were subject to thorough and consistent small bowel evaluation, so our follow-up time does not preclude the missed diagnosis of small bowel CD. Given the similarity in management, it is important to consider CD in the differential for isolated perianal disease patients even without luminal findings.

Contributor Information

Hannah W Fiske, Department of Internal Medicine, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

Chung Sang Tse, Division of Gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Badr Al-Bawardy, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; College of Medicine, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Division of Gastroenterology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA.

Pooja Magavi, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Gauree Gupta Konijeti, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, CA, USA.

Eric Mao, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of California Davis School of Medicine, Sacramento, CA, USA.

Sean Fine, Division of Gastroenterology, The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

Alyssa Parian, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Mark Lazarev, Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD, USA.

Samir A Shah, Gastroenterology Associates Inc. (Powered by GI Alliance), The Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA.

Author Contributions

H.W.F.: Conception and design of the study, analysis of data, drafting of the article, final approval; C.S.T., B.A.-B., P.M., G.G.K., E.M., S.F., A.P., and M.L.: Acquisition of data, critical revision of the article, final approval of the submitted version; S.A.S.: Conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, critical revision of the article, final approval of the submitted version.

Funding

None declared.

Conflicts of Interest

H.W.F.: no CoI to declare. C.S.T.: supported by grant funding from the American Gastroenterological Association and the Crohn’s and Colitis Foundation. B.A.-B.: Speaker fees from AbbVie, Takeda, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Hikma; Advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, AbbVie, and Eli Lilly. B.A.-B. holds the position of Editor/Global Perspectives for Crohn’s & Colitis 360 and has been recused from reviewing or making decisions for the manuscript. P.M.: No CoI to declare. G.G.K.: Consultant for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and WellTheory; Speaker’s bureau for Takeda and Eli Lilly. E.M.: No CoI to declare. S.F.: Advisory board for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Takeda, and AbbVie. A.P.: no CoI to declare. M.L.: Advisory board for Johnson and Johnson. S.A.S.: Board of trustees for American College of Gastroenterology; Consultant for Roche Information Systems.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available within the article itself. Any additional data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Human Subjects Research

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins Hospital (protocol #IRB00210084).

References

- 1. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement: perianal Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125(5):1503-1507. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gionchetti P, Dignass A, Danese S, et al. ; ECCO. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn’s disease 2016: Part 2: surgical management and special situations [published correction appears in J Crohns Colitis. 2022 Aug 16]. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(2):135-149. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsai L, McCurdy JD, Ma C, Jairath V, Singh S.. Epidemiology and natural history of perianal Crohn’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based cohorts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(10):1477-1484. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ibd/izab287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Molendijk I, Nuij VJ, van der Meulen-de Jong AE, van der Woude CJ.. Disappointing durable remission rates in complex Crohn’s disease fistula. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20(11):2022-2028. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laureti S, Gionchetti P, Cappelli A, et al. Refractory complex Crohn’s perianal fistulas: a role for autologous microfragmented adipose tissue injection. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(2):321-330. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ibd/izz051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vogel JD, Johnson EK, Morris AM, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of anorectal abscess, fistula-in-ano, and rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(12):1117-1133. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Amato A, Bottini C, De Nardi P, et al. ; Italian society of colorectal surgery. Evaluation and management of perianal abscess and anal fistula: a consensus statement developed by the Italian Society of Colorectal Surgery (SICCR). Tech Coloproctol. 2015;19(10):595-606. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10151-015-1365-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oliveira I, Kilcoyne A, Price M, Harisinghani M.. MRI features of perianal fistulas: is there a difference between Crohn’s and non-Crohn’s patients?. Abdom Radiol. 2017;42(4):1162-1168. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s00261-016-0989-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCurdy JD, Parlow S, Dawkins Y, et al. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors may have limited efficacy for complex perianal fistulas without luminal Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2020;65(6):1784-1789. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10620-019-05905-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Adler SN, Yoav M, Eitan S, Yehuda C, Eliakim R.. Does capsule endoscopy have an added value in patients with perianal disease and a negative work up for Crohn’s disease? World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;4(5):185-188. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.4253/wjge.v4.i5.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sangwan YP, SchoetzDJ, Jr, Murray JJ, Roberts PL, Coller JA.. Perianal Crohn’s disease. Results of local surgical treatment. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39(5):529-535. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02058706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Williams DR, Coller JA, Corman ML, Nugent FW, Veidenheimer MC.. Anal complications in Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1981;24(1):22-24. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1007/BF02603444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Park SH, Aniwan S, Scott Harmsen W, et al. Update on the natural course of fistulizing perianal Crohn’s disease in a population-based cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(6):1054-1060. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ibd/izy329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Irving PM, Gearry RB, Sparrow MP, Gibson PR.. Review article: appropriate use of corticosteroids in Crohn’s disease [published correction appears in Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 Mar 15;27(6):528-9]. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26(3):313-329. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03379.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Panes J, Reinisch W, Rupniewska E, et al. Burden and outcomes for complex perianal fistulas in Crohn’s disease: systematic review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(42):4821-4834. doi: https://doi.org/ 10.3748/wjg.v24.i42.4821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available within the article itself. Any additional data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.