Abstract

The use of a rapid, easy‐to‐use intervention could improve needle‐related procedural pain management practices in the context of the Emergency Department (ED). As such, the Buzzy device seems to be a promising alternative to topical anesthetics. The aim of this study was to determine if a cold vibrating device was non‐inferior to a topical anesthetic cream for pain management in children undergoing needle‐related procedures in the ED. In this randomized controlled non‐inferiority trial, we enrolled children between 4 and 17 years presenting to the ED and requiring a needle‐related procedure. Participants were randomly assigned to either the cold vibrating device or topical anesthetic (4% liposomal lidocaine; standard of care). The primary outcome was the mean difference (MD) in adjusted procedural pain intensity on the 0–10 Color Analogue Scale (CAS), using a non‐inferiority margin of 0.70. A total of 352 participants were randomized (cold vibration device n = 176, topical anesthetic cream n = 176). Adjusted procedural pain scores' MD between groups was 0.56 (95% CI:−0.08–1.20) on the CAS, showing that the cold vibrating device was not considered non‐inferior to topical anesthetic. The cold vibrating device was not considered non‐inferior to the topical anesthetic cream for pain management in children during a needle‐related procedure in the ED. As topical anesthetic creams require an application time of 30 min, cost approximately CAD $40.00 per tube, are underused in the ED setting, the cold vibrating device remains a promising alternative as it is a rapid, easy‐to‐use, and reusable device.

Keywords: children, cold and vibration, emergency, medical device, needle‐related procedures, pain management, pediatric

1. INTRODUCTION

Needle‐related procedures are considered by children to be painful and distressing. 1 , 2 , 3 Inadequate pain management during procedures can be harmful to children and can result in needle phobia. 4 , 5 Long‐term consequences include increased pain perceptions, 6 avoidance of medical care, 7 and noncompliance with vaccinations, 8 among others.

In previous decades, there has been a plethora of evidence evaluating the effectiveness of pharmacological and non‐pharmacological interventions for pain management in children undergoing needle‐related procedures. Despite efficacy of some interventions, procedural pain management remains often suboptimal, and their use remains limited, 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 particularly in the emergency department (ED) where it is a significant challenge due to time constraints, limited resources, and interruption in the continuity of care. 14 , 15 Additionally, some strategies may be expensive and require additional training. 15 , 16

The current recommended pharmacological intervention for needle‐related procedure, at the study's site, is the application of a topical anesthetic cream at the insertion site prior to the procedure. 17 Despite ample data showing benefit, 18 , 19 , 20 the required application time, ranging from 30 to 60 min, limits its implementation and routine use in the ED setting. 9 , 21 Papa & Zempsky 22 aimed to evaluate nurses' perception on pain management during needle‐related procedures through online surveys (N = 2187). Only 28% of the ED nurses acknowledged using a topical anesthetic cream for pain management during needle‐related procedures in children. Most of the nurses reported avoiding the use of topical anesthetic cream because of the associated delays related to the application time, as well as perceived vasoconstriction of blood vessels with some cream, despite the use of topical anesthetic proven to reduce procedural time and increasing success on first attempt. 22 A more recent study, by Alobayli & Blackman 23 also underlined the time constraint relating to topical anesthetic creams showing that procedural factors such as time concerns had a significant and direct influence on the use of topical anesthetics with a path coefficient of 0.26.

The optimal intervention for needle‐related pain management in the ED setting should be rapid, easy‐to‐use with few adverse effects. To satisfy these criteria, a device combining cold and vibration (Buzzy®, MMJ Labs, Atlanta, Georgia, USA) has been developed specifically for needle‐related pain management in children. This bee‐shaped device, combining a battery‐operated vibrating motor with removable ice wings, is based on two pain control mechanisms: the Gate Control Theory 24 and the diffuse noxious inhibitory controls, 25 both playing a role in the modulation of the transmission of pain. 26 The mechanical and thermal effect generated by the cold‐vibrating device stimulates the A‐α and A‐ß fibers which communicate the information they receive faster than the other fibers (A‐γ and B) which are responsible for the transmission of pain, with the belief effect of closing the gates to painful impulses generated by the needle‐related procedure. 24

A systematic review 24 showed that despite the majority of trials supporting the efficacy of the cold vibrating device for needle‐related pain and distress management in children, the quality of evidence was very low; the sample size of study limited the possibility to draw statistically significant results for 3/5 of the secondary outcomes measured (Success of the procedure at the first attempt (RR = 0.71; 95% CI: 0.35–1.43; I 2 = 0%; p = 0.34), Satisfaction (SMD: 0.40; 95% CI:−0.17 to 0.96; p = 0.17) and Side effects Adverse events (SMD: 0.40; 95% CI:−0.17 to 0.96; p = 0.17)). Therefore, high quality randomized controlled trials with improved methodology are essential to demonstrate the non‐inferiority of such a device. The primary objective of this trial was to determine if a device combining cold and vibration is non‐inferior (no worse) to liposomal lidocaine anesthetic cream for pain management in children undergoing needle‐related procedures in the ED. This agent is the standard treatment for needle‐related procedures at the study's site.

2. METHODS

The full study protocol 25 was published and the trial was registered (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT02616419). An authorization from the Medical Device Bureau of Health Canada was granted (#272708). The funding organization, Quebec Network on Research on Nursing Interventions‐Réseau de Recherche en Interventions en Sciences Infirmières du Québec (RRISIQ), had an independent role within this trial.

2.1. Trial design and study setting

This study was an open‐labeled randomized controlled non‐inferiority trial with two parallel groups and a 1:1 allocation ratio. The study setting was the ED of a Canadian university teaching pediatric tertiary care hospital in Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Ethics approval was obtained from the research ethics board (REB) of the institution.

2.2. Participants

Children were eligible for inclusion if they were: (1) 4–17 years old (The Buzzy device selected for this study could not be used on children younger than 4 years); (2) presenting to the ED and requiring a needle‐related procedure (venipuncture or intravenous (IV) catheter insertion); (3) able to communicate in either French or English and (4) accompanied by at least one parent/legal guardian who could understand, read and speak French or English. Children were excluded if they had: (1) a diagnosed neurocognitive disability (children with neurocognitive disability may have difficulty to self‐report their pain level 27 ); (2) inability to self‐report pain; (3) critical or unstable health status (Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale of 1 or 2); (4) Raynaud's syndrome or sickle cell disease with extreme sensitivity to cold; (5) a break or abrasion on the skin where the device would have been applied; (6) or nerve damage with limited sensation in the extremity where the needle‐related procedure would be performed. Parents and/or legal guardians provided written informed consent and assent was obtained from children over 7 years old.

2.3. Interventions

Children were randomly assigned, in a 1:1 allocation ratio, either to the experimental or control group. Participants assigned to the experimental group received the device intervention (Buzzy®, MMJ Labs, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Model # 56921 00300), a bee‐shaped device combining cold (removable and reusable ice wings) and vibration (body of the bee). The cold vibrating device was used in accordance with the manufacturer's recommendations: (1) Immediately before the needle‐related procedure, a set of ice wings were retrieved from the freezer; (2) Ice wings were installed on the back of the device through the elastic band; (3) The device was placed as close as possible to the insertion site (3–5 cm) with a reusable tourniquet and the vibrating mode was activated; (4) The device was maintained in place throughout the needle‐related procedure. All clinicians were trained to use the Buzzy and the lidocaine cream by the nurse clinician educator in the emergency room. Children assigned to the control group had 4% liposomal lidocaine topical anesthetic cream (Maxilene, RHR Pharma, LaSalle, Ontario, Canada) applied over the insertion site at least 30 min before the needle‐related procedure. Both interventions were tried only at first attempt. In case of multiple attempts, participants were excluded from the study.

2.4. Randomization and allocation

The randomization sequence was generated by an independent biostatistician using a computer‐generated random listing of the two interventions with a permuted block design and stratification by age‐group (4–7 years; 8–12 years; 13–17 years). Allocation concealment was ensured using sequentially numbered, sealed, opaque envelopes containing the intervention assignment which were opened once eligibility criteria were met, and consent was obtained. Blinding of participants and personnel was not possible due to the nature of both interventions.

2.5. Outcomes

The primary outcome was the mean difference (MD) in pain scores during the needle‐related procedure between groups. It was assessed immediately after the procedure using the self‐reported 0–10 Color Analogue Scale (CAS). 26

Pre‐specified secondary outcomes included: (1) MD between groups for procedural distress as assessed by proxy with Procedure Behavior Check List (PBCL) 28 and self‐reported with the Children's Fear Scale (CFS), 29 (2) Proportion of nurses experiencing success of the procedure on the first attempt, (3) Caregiver's and nurses satisfaction regarding both interventions using tailored questionnaires developed for the needs of the study, (4) MD in pain scores between groups was assessed by a research assistant, trained by the pain clinic, through a phone call 24 h after the needle‐related procedure (recall of pain) using the Faces Pain Scale Revised (FPS‐R) and 5) adverse events.

2.6. Sample size

A sample size of 352 participants provided 90% power to show the non‐inferiority of the cold vibrating device compared to a topical anesthetic cream, considering a one‐sided alpha level of 0.025 with the use of a non‐inferiority margin of 0.70 for the measure of pain intensity during the procedure. 25

2.7. Determination of the non‐inferiority margin

To determine the non‐inferiority margin, an electronic survey was sent to 34 pediatric emergency physicians, members of the Pediatric Emergency Research Canada, working in a pediatric ED setting in Quebec or Ontario. All of the physicians responded to the survey. The following scenario and question were presented: “You are seeing a four‐year‐old female requiring an intravenous catheter for drug delivery. You are considering two interventions for pain management during the needle‐related procedure: a topical anesthetic application (liposomal lidocaine 4% cream) or the Buzzy device. You need to assume that both of these interventions have the potential for reducing needle‐related pain.” “What is the smallest difference in mean pain reduction, on a numerical rating scale from 0 to 10cm, between the topical anesthetic (liposomal lidocaine 4% cream) and the Buzzy device you are willing to accept to routinely adopt the use of the Buzzy device over the topical anesthetic (liposomal lidocaine 4% cream) for needle‐related procedures”? Respondents had to choose a difference ranging from 0.1 to 1.5 cm with 0.1 increments. The mean answer was 0.70; consequently, this value was chosen as the non‐inferiority margin. 25 We did not account for dropouts. The sample size was calculated using the G*Power software version 3.0.10.

2.8. Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed using R for Macintosh Version 2022.7.1 and data analysis was only on participants first attempt.

The primary outcome was analyzed by calculating the confidence interval (CI) of the adjusted MD in pain scores between study groups. The cold vibrating device would be considered non‐inferior to the topical anesthetic cream if the upper limit of the two‐sided 95% CI (1–2α × 100% CI) for the adjusted MD in pain scores between groups is less than the predetermined non‐inferiority margin of ∆ 0.70. 25 We performed both a primary intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis and a secondary per‐protocol (PP) analyses, as required for non‐inferiority trials. 30 Both analyses were also performed with adjustment (covariance analyses) according to their respective baseline scores. A pre‐specified explanatory subgroup analysis according to age‐groups was also performed to determine if the intervention was more effective in a specific age‐group.

All secondary outcomes were designed to test the superiority of the cold vibrating device over the topical anesthetic cream and were analyzed on an ITT basis. Analyses of covariance was performed for procedural distress scores with adjustments for baseline scores. The Fisher's Exact Test was used to compare the proportion of participants whose procedure succeeded on the first attempt. The Mann–Whitney Test was performed to compare the MD on pain recall between groups as these results were not normally distributed. Descriptive statistics were used to report satisfaction scores.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Characteristics of participants

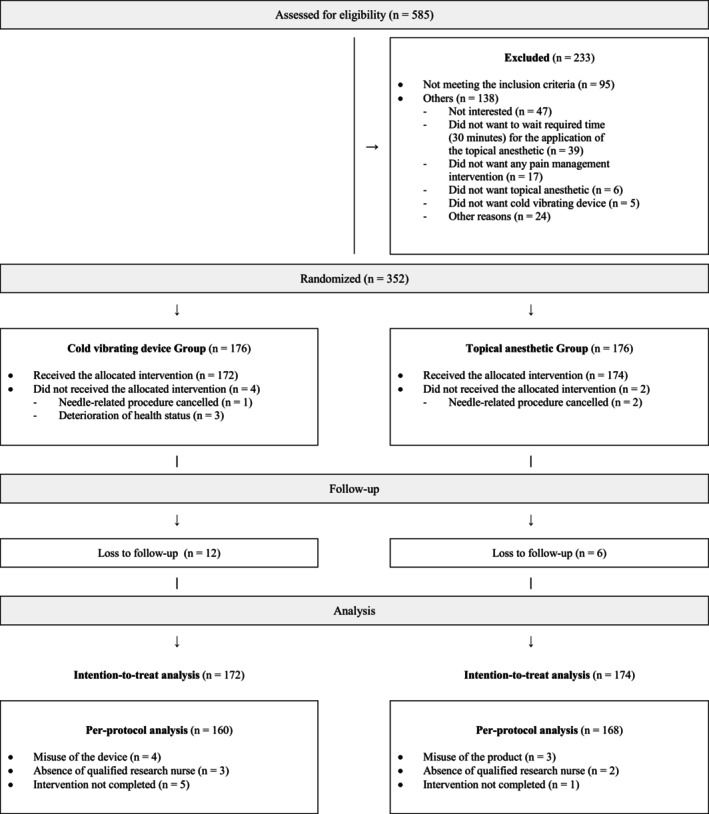

From April 2017 through September 2018, a total of 585 children were screened for eligibility. Of these, 352 were enrolled and randomly assigned to the intervention group (n = 176), or to the control group (n = 176). Among them, a total of 346 participants were included in the primary ITT analyses and 328 participants were included in the PP analyses (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart.

The baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants included in the ITT analysis were similar in both groups (Table 1, Table S1). Mean age of participants and standard deviation (SD) was 9.8 (3.9) years and a slight majority were female (51.2%, n = 177/346). The most common needle‐related procedure was venipuncture (73.0%, n = 251/346) (Table 1). Baseline characteristics of the PP sample are shown in Table S1.

TABLE 1.

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of participants.

| Participants' characteristics | Cold vibrating device (n = 172) | Topical anesthetic (n = 174) | Total (n = 346) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) Mean (SD) | 9.7 (3.9) | 10.0 (3.9) | 9.8 (3.9) |

| Sex n (%) | |||

| Girls | 87 (50.6) | 90 (49.4) | 177 (51.2) |

| Boys | 85 (49.4) | 84 (48.3) | 169 (48.8) |

| Types of needle‐related procedure n (%) | |||

| Venipuncture | 119 (70.0) | 132 (75.9) | 251 (73.0) |

| IV catheter | 51 (30.0) | 42 (24.1) | 93 (27.0) |

| Previous experience(s) with needle‐related procedure(s) a n (%) | |||

| Yes | 112 (65.5) | 111 (64.2) | 223 (64.8) |

| No | 59 (34.5) | 62 (35.8) | 121 (35.2) |

| Analgesia in the last 4 h n (%) | |||

| Yes | 66 (38.6) | 63 (36.6) | 129 (37.6) |

| No | 105 (61.4) | 107 (62.2) | 212 (61.8) |

| Don't know | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.2) | 2 (0.6) |

| Site of the needle‐related procedure n (%) | |||

| Antecubital | 126 (73.7) | 132 (77.2) | 258 (75.4) |

| Hand | 32 (18.7) | 36 (21.0) | 68 (19.9) |

| Wrist | 12 (7.0) | 2 (1.2) | 14 (4.1) |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) |

| Position during needle‐related procedure n (%) | |||

| Dorsal decubitus | 101 (58.7) | 73 (42.7) | 174 (50.7) |

| Sitting alone | 54 (31.4) | 70 (40.9) | 124 (36.2) |

| Sitting on parents | 11 (6.4) | 20 (11.7) | 31 (9.0) |

| Dorsal decubitus with restraint | 6 (3.5) | 7 (4.1) | 13 (3.8) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Non‐pharmacological co‐intervention n (%) | |||

| Yes | 30 (17.4) | 33 (19.0) | 63 (18.2) |

| No | 142 (82.6) | 138 (79.3) | 280 (80.9) |

| Pre‐procedural pain (CAS) Mean (SD) | 2.9 (2.6) | 2.6 (2.7) | 2.7 (2.6) |

| Pre‐procedural pain (FPS‐R) Mean (SD) | 2.8 (2.6) | 2.7 (2.9) | 2.8 (2.8) |

| Pre‐procedural distress (PBCL) Mean (SD) | 9.6 (3.4) | 9.0 (2.5) | 9.3 (3.0) |

| Pre‐procedural distress (CFS) Mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.6 (1.4) |

Abbreviations: CAS, color analogue scale; CFS, children's fear scale; FPS‐R, faces pain scale revised; PBCL, procedure behavioral check list.

Previous experience(s) with needle‐related procedure(s) excluding vaccination related to the Quebec immunization program.

3.2. Primary outcome

As per ITT analyses, the adjusted mean per‐procedural pain scores for both the cold vibrating and 4% liposomal lidocaine cream groups were respectively 3.77 and 3.22, thus a Mean Difference (MD) of 0.56 (95% CI: −0.08–1.20) between groups on the CAS scale. Therefore, the cold vibrating device was not considered non‐inferior to the topical anesthetic cream for decreasing per‐procedural pain scores, as the upper limit of the CI was not lower than the predetermined non‐inferiority margin (∆ 0.70). 25 Results of univariate analyses for per‐procedural pain yielded similar results. In the PP analysis, adjusted MDs in per‐procedural pain scores were slightly decreased between both groups. Adjusted subgroups analyses according to age‐groups showed similar results among the 8–12‐year‐old and 13–17 year old age‐groups. The adjusted subgroups analyses of 4–7‐year age‐group showed higher per‐procedural pain scores with a significantly higher MD for children of the intervention group (p = 0.04). (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Adjusted pain scores according to study groups and age‐groups analyses.

| Outcomes | n | Cold vibrating device Mean (SE) | n | Topical anesthetic Mean (SE) | Mean difference MD [95% CI] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural pain CAS | |||||||

| Intention‐to‐treat analysis | 158 | 3.77 | (0.231) | 161 | 3.22 | (0.228) | 0.56 [−0.08–1.20] |

| Per‐protocol analysis | 149 | 3.71 | (0.234) | 157 | 3.13 | (0.227) | 0.57 [−0.07–1.21] |

| Age group analysis | |||||||

| 4–7 years old a (n = 116) Intention‐to‐treat analysis | |||||||

| 46 | 5.04 | (0.504) | 47 | 3.54 | (0.499) | 1.50 [0.08–2.92] | |

| 8–12 years old (n = 133) | |||||||

| Intention‐to‐treat analysis | 66 | 3.72 | (0.335) | 65 | 3.27 | (0.335) | 0.46 [−0.49–1.40] |

| 13–17 years old (n = 97) | |||||||

| Intention‐to‐treat analysis | 46 | 2.74 | (0.344) | 49 | 2.69 | (0.333) | 0.05 [−0.90–1.00] |

Note: Adjusted analysis: All Procedural Pain. CAS scores have been adjusted with their respective Pre‐procedural Pain CAS score collected at baseline.

Abbreviations: CAS, color analogue scale; CI: confidence interval; SE, standard error; MD, mean difference.

The CAS scale is not validated for use with 4‐year‐olds. All results reported on the CAS by 4‐year‐old participants have therefore been replaced with missing values.

3.3. Secondary outcomes

Main results on secondary outcomes are presented below and summarized in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Secondary outcomes.

| Outcomes | n (172) | Cold vibrating device Mean (SD) | n (174) | Topical anesthetic Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p value (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Procedural pain FPS‐R | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 167 | 3.95 (3.41) | 170 | 3.46 (3.26) | 0.49 [−0.22–1.21] | 0.175 |

| Adjusted mean | 3.90 | 3.47 | 0.43 [−0.26–1.13] | 0.219 | ||

| Procedural distress PBCL | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 171 | 12.77 (6.36) | 170 | 11.35 (5.17) | 1.41 [0.18–2.65] | 0.025* |

| Adjusted mean | 12.50 | 11.60 | 0.89 [−0.18–1.97] | 0.104 | ||

| Procedural distress CFS | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 170 | 1.70 (1.46) | 171 | 1.56 (1.39) | 0.14 [−0.17–0.44] | 0.370 |

| Adjusted mean | 1.69 | 1.58 | 0.11 [−0.15–0.36] | 0.421 | ||

| Success of the procedure at first attempt | ||||||

| n (%) | 172 | 136 (79.1) | 172 | 137 (79.7) | – | 1.000 |

| Pain recall FPS‐R | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 75 | 3.55 (3.41) | 79 | 3.01 (3.02) | 0.53 [−0.49–1.56] | 0.305 |

Note: Adjusted mean: All procedural scores have been adjusted with their respective pre‐procedural scores collected at baseline.

Abbreviations: CI, Confidence interval; CFS, Children's Fear Scale; FPS‐R: faces pain scale revised; PCBL, procedure behavioral check list; SD: Standard deviation.

3.3.1. Procedural distress hetero‐evaluation and reported fear

For the per‐procedural distress, adjusted MD between groups were not statistically significant on the PBCL scale (MD = 0.89 [95% CI: −0.18–1.97], p = 0.104) and for reported fear on CFS (MD = 0.11 [95% CI: −0.15–0.36], p = 0.421) scale.

3.3.2. Procedural pain (FPR‐S)

Procedural pain measured with the FPS‐R showed no statistically significant adjusted MDs between groups (MD = 0.43 [95% CI:−0.26–1.13], p = 0.219).

3.3.3. Success of procedure at first attempt

Success of the needle‐related procedure at first attempt occurred in 136 of the 172 children (79.1%) in the cold and vibration group and in 137 of the 172 children (79.7%) in the topical anesthetic cream group. Difference between both groups was not statistically significant (p = 1.000).

3.3.4. Pain recall (memory)

There was no significant difference between groups on the adjusted mean scores for pain recall (memory) 24 h after the needle‐related procedure (MD = 0.53 [95% CI: −0.49–1.56], p = 0.305). Since 56% of values were missing (n = 192), it can be assumed that they were missing at random and that the estimate was unbiased, as they were balanced in both groups.

3.3.5. Parents' satisfaction

A majority of parents from both groups reported being highly satisfied with the allocated intervention, cold vibrating device mean (SD) = 7.81 (2.67), topical anesthetic cream mean (SD) = 8.14 (2.40) (Table 4). Parents of both groups, cold vibrating device (88.2%, n = 149/169) and topical anesthetic cream (91.2%, n = 156/171), mentioned that they would opt for the same intervention for a subsequent needle‐related procedure.

TABLE 4.

Parents' satisfaction.

| Question | Cold vibrating device n (%) | Topical anesthetic n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Would you agree to reuse this intervention during a future needle‐procedure with you child? | |||||||

| Yes | 149 (88.2) | 156 (91.2) | |||||

| No | 14 (8.3) | 8 (4.7) | |||||

| No parent or guardian | 6 (3.6) | 7 (4.1) | |||||

| Outcomes | n (172) | Cold vibrating device mean (SD) | n (176) | Topical anesthetic Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | p‐value (α = 0.05) | |

| Satisfaction | |||||||

| 0: 10 | 171 | 7.8 (2.7) | 170 | 8.1 (2.4) | −0.34 [−0.89–0.22] | 0.257 | |

3.3.6. Nurses' satisfaction

Overall, nurses reported high levels of satisfaction with both interventions during needle‐related procedures (Table 5). Most nurses (71.4%, n = 15/21) mentioned that the cold vibrating device was adapted to the ED environment. Most nurses (76.2%, n = 16/21) agreed to use the cold vibrating device again to perform needle‐related procedures. Finally, more than half of the nurses (65.0%, n = 13/20) indicated that they preferred the cold vibrating device over the topical anesthetic cream for pain management in children during needle‐related procedures.

TABLE 5.

Nurses' satisfaction regarding both interventions.

| Statements | Cold vibrating device n (%) | Topical anesthetic n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of utilizations of trial interventions during the study period | ||

| 0–5 times | 11 (50.0) | 4 (19.0) |

| 5–10 times | 5 (22.7) | 8 (38.1) |

| 10–15 times | 1 (4.5) | 2 (9.5) |

| >−15 times | 4 (18.2) | 6 (28.6) |

| The intervention helped children to control their pain during the procedure | ||

| Strongly agree | 1 (4.8) | 4 (18.2) |

| Agree | 16 (76.2) | 12 (54.5) |

| Disagree | 4 (19.0) | 5 (27.3) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) |

| The intervention helped children to control their distress during the procedure | ||

| Strongly agree | 2 (9.5) | 2 (9.1) |

| Agree | 16 (76.2) | 14 (63.6) |

| Disagree | 3 (14.3) | 5 (27.3) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0.0) | 1 (4.5) |

| The intervention helped children to cooperate during the procedure | ||

| Strongly agree | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.5) |

| Agree | 17 (81.0) | 18 (81.8) |

| Disagree | 2 (9.5) | 3 (13.6) |

| Strongly disagree | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| I would agree to reuse the intervention for subsequent department | ||

| Strongly agree | 7 (33.3) | 8 (36.4) |

| Agree | 9 (34.6) | 8 (36.4) |

| Disagree | 3 (14.3) | 5 (22.7) |

| Strongly disagree | 2 (9.5) | 1 (4.5) |

| The intervention is tailored to the emergency department | ||

| Strongly agree | 8 (38.1) | 3 (13.6) |

| Agree | 7 (33.3) | 7 (31.8) |

| Disagree | 5 (23.8) | 7 (31.8) |

| Strongly disagree | 1 (4.8) | 5 (22.7) |

| Nurses' preference | 13 (65.0) | 7 (35.0) |

3.3.7. Adverse events

No adverse events occurred in the cold vibrating device group. A participant in the topical anesthetic cream group reported redness and swelling at the insertion site the day after the needle‐related procedure. However, this could be associated with the IV catheter insertion itself and not necessarily related to the topical anesthetic cream.

4. DISCUSSION

In this randomized controlled non‐inferiority trial comparing two interventions for pain management in children undergoing needle‐related procedures in the ED setting, the cold vibrating device was not considered non‐inferior to 4% liposomal lidocaine anesthetic cream.

Further, considering that children are known to report moderate‐to‐high pain intensity during needle‐related procedures, 2 , 5 it is important to highlight that the cold vibrating device control procedural pain within a moderate intensity level (CASadjusted = 3.77). 31 Also, recalled pain scores remained low but it remains in accordance to other studies with the same procedure. 32 In addition, the cold vibrating device has some advantages over the topical anesthetic cream for the ED environment. For instance, it does not require a pre‐procedure application time, it is easy‐to‐use, reusable and with no reported adverse events within participants of this study. Considering that the topical anesthetic cream requires a minimum application time of 30 min, the device represents a feasible alternative to optimize procedural pain control, especially when time is limited. 18 , 22

Other randomized controlled trials 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 have demonstrated the efficacy of the cold vibrating device for needle‐related pain management in children. However, as shown in a systematic review, 24 these studies presented a high risk of biases and represented a very low quality of evidence. Among these studies, some have compared the efficacy of the cold vibrating device to a topical anesthetic cream in the ED. 37 , 38 One of these trials, 38 involving children aged between 18 months and 6 years old, compared the efficacy of the device to an anesthetic lidocaine/prilocaine patch for pain management during IV catheter insertions. Mean pain scores and standard deviation (device mean [SD] = 8.5/13 [2.6], patch mean [SD] = 7.2/13 [2.4], p < 0.001), showed that the cold vibrating device was not significantly different than the topical anesthetic cream. The second trial 37 demonstrated the non‐inferiority of the cold vibrating device over 4% topical lidocaine cream for pain and distress management during needle‐related procedures. However, this study presented some limitations concerning the trial design. Firstly, the choice of the non‐inferiority margin was not justified adequately and was too large, which could have introduced a greater risk of mistakenly concluding a truly inferior intervention as non‐inferior. 39 Further, they used a two‐sided CI of 90% instead of the 95% recommended. 30

Our results showed that the small sample of nurses in this study preferred the cold vibrating device over the topical anesthetic cream used. They also reported that it was more tailored and adapted to the ED environment, which represents a good indicator of its possible implementation and uptake in daily practice. As nurses are playing a critical role in the pain management process, it is important to provide them with tools that are adapted to their clinical environment.

5. LIMITATIONS

Finally, our study has several limitations that must be acknowledged. First, blinding of participants and personnel was not possible considering the nature of both interventions. The lack of blinding could have influenced the behavior and responses of children to subjective outcomes. To minimize the performance bias, we used 4% liposomal lidocaine in order to generate similar expectation ratings from participants in both groups. Second, the choice of the non‐inferiority margin of 0.70 may have been too small and it may explain the inconclusive results. 30

6. CONCLUSION

In this non‐inferiority trial, we found that the device combining cold and vibration was not considered non‐inferior to a topical anesthetic cream for pain management in children undergoing needle‐related procedures. The trial demonstrated that the device had the potential to control pain and distress experienced by children during needle‐related procedures and possibly to improve nurses' pain management practices in the ED setting. As the device was highly appreciated by parents and nurses, it has a potential to be implemented and uptake this setting. Finally, since most of the available topical creams for needle‐related procedures require supplementary application time, the cold vibrating device may be a feasible option in pediatric ED settings.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTORS

Study supervision SLM; Study concept and design AB, CK; NP, EDT, BB; Analysis and interpretation of the data AB; Drafting of the manuscript AB; Critical revision of the manuscript AB, CL, OF, EG, EDT, BB, NP, SLM; Statistical expertise AB, OF, SLM; Acquisition of funding‐SLM.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This study was supported by the Réseau de recherche sur les interventions en sciences infirmières du Québec (RRISIQ).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to this article to disclose. The trial had no commercial support, and the manufacturer of the device had no implication in the trial design, data collection, data analysis, or manuscript preparation and no access to the trial data. The authors have no financial relationship relevant to this article to disclose.

Supporting information

Table S1.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to acknowledge the research nurses (Mrs Maryse Lagacé, Ramona Cook and Marie‐Christine Auclair) for their valuable involvement in the recruitment and data collection phases. We are also grateful to all the ED staff, as the study would have not been possible without their support. We also thank all the recruited children and their family for participation. We acknowledge the Applied Clinical Research Unit (URCA) of the CHU Sainte‐Justine, Aude‐Christine Guédon and Golsa Dehghan, for their assistance with statistical analyses. AB was financially supported by the following agencies: Fonds de recherche Santé – Québec (FRS‐Q), ministère de l'Éducation et de l'Enseignement supérieur du Québec (MEES), and Quebec Network on Nursing Intervention Research. AB, CK and SLM are part of the Pain in Child Health Strategic Training Consortium (PICH), sponsored by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Ballard A, Khadra C, Fortin O, et al. Cold and vibration for children undergoing needle‐related procedures: A non‐inferiority randomized clinical trial. Paediatr Neonatal Pain. 2024;6:164‐173. doi: 10.1002/pne2.12125

REFERENCES

- 1. Jeffs D, Wright C, Scott A, Kaye J, Green A, Huett A. Soft on sticks: an evidence‐based practice approach to reduce children's needlestick pain. J Nurs Care Qual. 2011;26(3):208‐215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ortiz MI, López‐Zarco M, Arreola‐Bautista EJ. Procedural pain and anxiety in paediatric patients in a Mexican emergency department. J Adv Nurs. 2012;68(12):2700‐2709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Birnie KA, Chambers CT, Fernandez CV, et al. Hospitalized children continue to report undertreated and preventable pain. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(4):198‐204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McMurtry CM, Pillai Riddell R, Taddio A, et al. Far From Just a Poke. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(10):S3‐S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Taddio A, Ipp M, Thivakaran S, et al. Survey of the prevalence of immunization non‐compliance due to needle fears in children and adults. Vaccine. 2012;30(32):4807‐4812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Armfield JM, Milgrom P. A clinician guide to patients afraid of dental injections and numbness. SAAD Dig. 2011;27:33‐39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Taddio A, McGrath P, Finley A. Effects of early pain experience: the human literature. Progress in Pain Research and Management. 1999;13:57‐74. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wright S, Yelland M, Heathcote K, Ng SK, Wright G. Fear of needles—nature and prevalence in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2009;38(3):172‐176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chidambaran V, Sadhasivam S. Pediatric acute and surgical pain management: recent advances and future perspectives. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 2012;50(4):66‐82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stinson J, Yamada J, Dickson A, Lamba J, Stevens B. Review of systematic reviews on acute procedural pain in children in the hospital setting. Pain Res Manag. 2008;13(1):51‐57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Birnie KA, Noel M, Chambers CT, Uman LS, Parker JA. Psychological interventions for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10:CD005179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stevens BJ, Harrison D, Rashotte J, et al. Pain assessment and intensity in hospitalized children in Canada. J Pain. 2012;13(9):857‐865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Uman LS, Birnie KA, Noel M, et al. Psychological interventions for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD005179. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pretorius A, Searle J, Marshall B. Barriers and enablers to emergency department nurses' management of patients' pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(3):372‐379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fein JA, Zempsky WT, Cravero JP, et al. Relief of pain and anxiety in pediatric patients in emergency medical systems. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):e1391‐e1405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Trottier ED, Ali S, Thull‐Freedman J, et al. Treating and reducing anxiety and pain in the paediatric emergency department‐TIME FOR ACTION‐the TRAPPED quality improvement collaborative. Paediatr Child Health. 2018;23(5):e85‐e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Procédures mineures: prise en charge de la douleur et de la détresse procédurales—Urgence CHU Sainte‐Justine. 2023. https://www.urgencehsj.ca/protocoles/analgesie‐procedures‐mineures/.

- 18. Taddio A, Gurguis MG, Koren G. Lidocaine‐prilocaine cream versus tetracaine gel for procedural pain in children. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36(4):687‐692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shah V, Taddio A, Rieder MJ. Effectiveness and tolerability of pharmacologic and combined interventions for reducing injection pain during routine childhood immunizations: systematic review and meta‐analyses. Clin Ther. 2009;31:S104‐S151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fetzer SJ. Reducing venipuncture and intravenous insertion pain with eutectic mixture of local anesthetic: a meta‐analysis. Nurs Res. 2002;51(2):119‐124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alobayli FY. Factors influencing nurses' use of local anesthetics for venous and arterial access. J Infus Nurs. 2019;42(2):91‐107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Papa A, Zempsky W. Nurse perceptions of the impact of pediatric peripheral venous access pain on nurse and patient satisfaction: results of a National Survey. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2010;32(3):226‐233. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Alobayli FY, Blackman I. Modelling nurses' use of local anaesthesia for intravenous cannulation and arterial blood gas sampling: a cross‐sectional study. Heliyon. 2020;6(3):e03428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ballard A, Khadra C, Adler S, Trottier ED, Le May S. Efficacy of the buzzy device for pain management during needle‐related procedures: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Clin J Pain. 2019;35(6):532‐543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ballard A, Khadra C, Adler S, et al. External cold and vibration for pain management of children undergoing needle‐related procedures in the emergency department: a randomised controlled non‐inferiority trial protocol. BMJ Open. 2019;9(1):e023214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McGrath PA, Seifert CE, Speechley KN, Booth JC, Stitt L, Gibson MC. A new analogue scale for assessing children's pain: an initial validation study. Pain. 1996;64(3):435‐443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Breau LM, Burkitt C. Assessing pain in children with intellectual disabilities. Pain Res Manag. 2009;14(2):116‐120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. LeBaron S, Zeltzer L. Assessment of acute pain and anxiety in children and adolescents by self‐reports, observer reports, and a behavior checklist. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1984;52(5):729‐738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McMurtry CM, Noel M, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ. Children's fear during procedural pain: preliminary investigation of the Children's fear scale. Health Psychol. 2011;30(6):780‐788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mauri L, D'Agostino RB Sr. Challenges in the design and interpretation of noninferiority trials. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1357‐1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Tsze DS, Hirschfeld G, Dayan PS, Bulloch B, Von Baeyer CL. Defining No pain, mild, moderate, and severe pain based on the faces pain scale–revised and color analog scale in children with acute pain. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2018;34(8):537‐544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nilsson S, Finnström B, Kokinsky E, Enskär K. The use of virtual reality for needle‐related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents in a paediatric oncology unit. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2009;13(2):102‐109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Redfern RE, Chen JT, Sibrel S. Effects of thermomechanical stimulation during vaccination on anxiety, pain, and satisfaction in pediatric patients: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr Nurs. 2018;38:1‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Inal S, Kelleci M. The effect of external thermomechanical stimulation and distraction on reducing pain experienced by children during blood drawing. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2020;36(2):66‐69. https://journals.lww.com/00006565‐900000000‐98623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Moadad N, Kozman K, Shahine R, Ohanian S, Badr LK. Distraction using the buzzy for children during an IV insertion. J Pediatr Nurs. 2016;31(1):64‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Schreiber S, Cozzi G, Rutigliano R, et al. Analgesia by cooling vibration during venipuncture in children with cognitive impairment. Acta Paediatr. 2016;105(1):e12‐e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Potts DA, Davis KF, Elci OU, Fein JA. A vibrating cold device to reduce pain in the pediatric emergency department: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(6):419‐425. https://journals.lww.com/00006565‐900000000‐98807‐98807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bourdier S, Khelif N, Velasquez M, et al. Cold vibration (Buzzy) versus anesthetic patch (EMLA) for pain prevention during cannulation in children: a randomized trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2021;37(2):86‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ, Altman DG, Group C . Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: extension of the CONSORT 2010 statement. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2594‐2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1.