Abstract

Purpose

This descriptive analysis evaluated the 2022 assisted reproductive technology (ART) data collected by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology registry.

Methods and Results

In 2022 (cutoff date 30 November 2023), 634 of 635 registered ART facilities participated; 602 implemented ART treatment, with 543 630 registered cycles and 77 206 neonates (9.1% and 10.6% increases from the previous year). For fresh cycles, freeze‐all in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles increased, resulting in 2183 and 2822 neonates, respectively. In total, 275 296 cycles resulted in oocyte retrieval, with 158 247 (57.5%) freeze‐all cycles. Total single embryo transfer (ET) and singleton pregnancy rates were 82.4% and 97.2%, respectively. The singleton live birth rate was 97.4%. The number of frozen–thawed ET (FET) cycles was 264 412, with 98 348 pregnancies and 72 201 neonates. The single ET rate was 85.3%. The rate of singleton pregnancies was 96.9%; that of singleton live births was 96.9%. Per registered cycle, women had a mean age of 37.6 (standard deviation: 4.8) years; 210 322 cycles (38.7%) were conducted for women aged ≥40 years.

Conclusions

Significant growth in ART cycles and outcomes reflects the impact of recent expanded insurance coverage.

Keywords: assisted reproductive technologies, fertility rate, in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injections, Japan

In 2022, 634 of 635 registered ART facilities participated; 602 implemented ART treatment, with 543 630 registered cycles and 77 206 neonates (9.1% and 10.6% increases from the previous year). Significant growth in ART cycles and outcomes reflects the impact of recent expanded insurance coverage.

1. INTRODUCTION

Fertility rates in Japan have been trending downward over the past four decades, 1 with rapidly declining birth rates and accelerated aging. By 2020, the total fertility rate in Japan had decreased to 1.33 births per woman, 2 lower than the previous record of 1.36 in 2019 and significantly down from the 1.44 rate in 2016. 2 More recent data indicate that the total fertility rate in Japan has continued to decrease yearly to historically low rates of 1.26 and 1.20 births per woman in 2022 and 2023. 3 The World Bank reported a global fertility rate of 2.4 in 2019, 2.3 in 2020, and 2.3 in 2022, depicting a similar global trend in declining fertility rates. 4 The underlying causes of this phenomenon are complex, with a range of factors thought to have impacted fertility and birth rates in Japan. These may include tendencies to marry late or not at all, 5 , 6 increasing trends in later childbearing that accompany women's empowerment in education and the workforce, 7 increased burdens of parenting and rising costs of raising children, difficulties women experience in continuing to work, 8 increases in the rate of irregular employment, 9 , 10 and growth of a super‐aged population. 11 , 12

The Japanese government has made extensive efforts to reverse these fertility trends, among which perhaps the most impactful measures might be the doubling of government spending on child‐related programs and coverage of assisted reproductive technology (ART) and male infertility treatments by public insurance since April 2022. 13 , 14 Given the increasing trend toward later childbearing, Japan's ART field has seen significant advancements and changes over the years, reflecting evolving societal attitudes and advancements in medical technology. 14 , 15 Indeed, Japan is a leading country in the use of ART. 16 In 2021, 498 140 cycles of ART were performed in Japan, which led to 69 797 live births, representing increases of 10.7% and 15.5%, respectively, from the numbers reported in 2020. 17

The Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology (JSOG) has been monitoring and reporting developments in ART since 1986. In 2007, it implemented an online ART registration system. The committee publishes an annual report that provides a comprehensive overview of ART practices, trends, and ethical considerations in Japan. This examination of data from registered ART facilities may be helpful in updating policymakers, health care providers, and the public about the evolving landscape of reproductive medicine. The following report will examine the detailed findings and implications of the 2022 ART data collected by the JSOG and compare the present results with those from previous years.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Data source and data collection

The JSOG registry collects data from registered ART facilities across Japan. It collects demographic and background characteristics of patients, clinical information such as infertility diagnosis, treatment information, and pregnancy and obstetric outcomes following treatment as ART‐cycle‐specific data. 18 The present descriptive analysis investigated registered cycle characteristics and treatment outcomes using data from the Japanese ART registry in 2022 with a cutoff date of 30 November 2023.

2.2. Variables of interest

Data for the following variables by fertilization method (in vitro fertilization [IVF], intracytoplasmic sperm injection [ICSI], and frozen–thawed embryo transfer [FET]) were collected, analyzed, and compared with data from previous years: number of registered cycles, oocyte retrievals, embryo transfer (ET) cycles, freeze‐all‐embryo/oocyte cycles, and numbers of pregnancies and neonates. Characteristics of registered cycles and pregnancy outcomes were described for fresh and FET cycles. Fresh cycle data were stratified by fertilization method (i.e., IVF and ICSI).

2.3. Outcomes

The list and definitions of the treatment outcomes analyzed and compared were as follows: pregnancy (confirmation of a gestational sac in utero), miscarriage (spontaneous or unplanned loss of a fetus from the uterus before 22 weeks of gestation), live birth (delivery of at least one live neonate after 22 weeks of gestation), and multiple pregnancy rates.

The pregnancy outcomes analyzed and compared were ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancy, artificially induced abortion, stillbirth, and fetal reduction. The following outcomes were also analyzed by patient age: pregnancy, live birth, miscarriage, and multiple pregnancy rates. Treatment outcomes for FET cycles using frozen–thawed oocytes were also analyzed.

2.4. Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using the STATA MP statistical package, version 18.5 (Stata, College Station). Statistical testing was not conducted as this study focuses on descriptive analysis.

3. RESULTS

In 2022, of the 635 registered ART facilities, 634 participated in the JSOG registry and, of these, 602 actually implemented ART treatment.

Table 1 summarizes the main trends in the numbers of registered cycles, egg retrievals, pregnancy, and neonate births categorized by IVF, ICSI, and FET cycles in Japan (2007–2022). In 2022, 543 630 cycles were registered for IVF, ICSI, and FET, and a total of 77 206 neonates were recorded in Japan, representing 9.1% and 10.6% increases from the previous year. Of note, the number of IVF cycles registered increased by 3.4%, and ICSI cycles increased by 10.3% from the numbers reported in 2021.

TABLE 1.

Trends in numbers of registered cycles, oocyte retrieval, pregnancy, and neonates based on IVF, ICSI, and frozen–thawed embryo transfer cycles in Japan, 2007–2022.

| Year | IVF a | ICSI b | FET cycle c | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of registered cycles | No. of egg retrievals | No. of freeze‐all cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | No. of registered cycles | No. of egg retrievals | No. of freeze‐all cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | No. of registered cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | No. of neonates | |

| 2007 | 53 873 | 52 165 | 7626 | 28 228 | 7416 | 5144 | 61 813 | 60 294 | 11 541 | 34 032 | 7784 | 5194 | 45 478 | 43 589 | 13 965 | 9257 |

| 2008 | 59 148 | 57 217 | 10 139 | 29 124 | 6897 | 4664 | 71 350 | 69 864 | 15 390 | 34 425 | 7017 | 4615 | 60 115 | 57 846 | 18 597 | 12 425 |

| 2009 | 63 083 | 60 754 | 11 800 | 28 559 | 6891 | 5046 | 76 790 | 75 340 | 19 046 | 35 167 | 7330 | 5180 | 73 927 | 71 367 | 23 216 | 16 454 |

| 2010 | 67 714 | 64 966 | 13 843 | 27 905 | 6556 | 4657 | 90 677 | 88 822 | 24 379 | 37 172 | 7699 | 5277 | 83 770 | 81 300 | 27 382 | 19 011 |

| 2011 | 71 422 | 68 651 | 16 202 | 27 284 | 6341 | 4546 | 102 473 | 100 518 | 30 773 | 38 098 | 7601 | 5415 | 95 764 | 92 782 | 31 721 | 22 465 |

| 2012 | 82 108 | 79 434 | 20 627 | 29 693 | 6703 | 4740 | 125 229 | 122 962 | 41 943 | 40 829 | 7947 | 5498 | 119 089 | 116 176 | 39 106 | 27 715 |

| 2013 | 89 950 | 87 104 | 25 085 | 30 164 | 6817 | 4776 | 134 871 | 134 871 | 49 316 | 41 150 | 8027 | 5630 | 141 335 | 138 249 | 45 392 | 32 148 |

| 2014 | 92 269 | 89 397 | 27 624 | 30 414 | 6970 | 5025 | 144 247 | 141 888 | 55 851 | 41 437 | 8122 | 5702 | 157 229 | 153 977 | 51 458 | 36 595 |

| 2015 | 93 614 | 91 079 | 30 498 | 28 858 | 6478 | 4629 | 155 797 | 153 639 | 63 660 | 41 396 | 8169 | 5761 | 174 740 | 171 495 | 56 888 | 40 611 |

| 2016 | 94 566 | 92 185 | 34 188 | 26 182 | 5903 | 4266 | 161 262 | 159 214 | 70 387 | 38 315 | 7324 | 5166 | 191 962 | 188 338 | 62 749 | 44 678 |

| 2017 | 91 516 | 89 447 | 36 441 | 22 423 | 5182 | 3731 | 157 709 | 155 758 | 74 200 | 33 297 | 6757 | 4826 | 198 985 | 195 559 | 67 255 | 48 060 |

| 2018 | 92 552 | 90 376 | 38 882 | 20 894 | 4755 | 3402 | 158 859 | 157 026 | 79 496 | 29 569 | 5886 | 4194 | 203 482 | 200 050 | 69 395 | 49 383 |

| 2019 | 88 074 | 86 334 | 40 561 | 17 345 | 4002 | 2974 | 154 824 | 153 014 | 83 129 | 24 490 | 4789 | 3433 | 215 203 | 211 758 | 74 911 | 54 188 |

| 2020 | 82 883 | 81 286 | 42 530 | 13 362 | 3094 | 2282 | 151 732 | 150 082 | 87 697 | 19 061 | 3626 | 2596 | 215 285 | 211 914 | 76 196 | 55 503 |

| 2021 | 88 362 | 86 901 | 42 016 | 13 219 | 3115 | 2268 | 170 350 | 168 659 | 86 992 | 19 740 | 3875 | 2850 | 239 428 | 236 211 | 87 174 | 64 679 |

| 2022 | 91 402 | 89 807 | 49 433 | 12 211 | 3007 | 2183 | 187 816 | 185 489 | 108 814 | 19 299 | 3878 | 2822 | 264 412 | 260 101 | 98 348 | 72 201 |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; FET, frozen–thawed embryo transfer; GIFT, gamete intrafallopian transfer; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF, in vitro fertilization.

Including GIFT and other.

Including split‐ICSI cycles.

Including cycles using frozen–thawed oocyte.

In contrast with 2021, freeze‐all IVF and ICSI increased by 17.7% and 25.1%, respectively. The number of neonates born by IVF‐ET cycles was 2183 and 2822 by ICSI, representing slight decreases (3.7% and 1.0%) from the previous year. The continuously increasing trend seen for FET cycles since 2007 was maintained in 2022, with a 10.4% increase. The number of FET cycles was 264 412, with 98 348 pregnancies and 72 201 neonates.

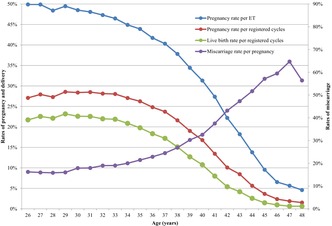

Figure 1 shows the age distributions for all registered cycles and different subgroups of cycles for ET, pregnancy, and live births in 2022. The mean patient age for registered cycles was 37.6 years (standard deviation [SD] ± 4.8); the mean age for pregnancy and live birth cycles was 35.7 years (SD ± 4.3) and 35.2 years (SD ± 4.2), respectively. In 2022, 38.7% of ART cycles (210 322 cycles) registered were undertaken for women aged 40 years or over. Of note, there was a peak in registered cycles (46095) among patients aged 42 years.

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of maternal age from all registered cycles, cycles for ET, cycles leading to pregnancy, and cycles leading to live births in 2022. Adapted from the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology ART Databook 2022 (https://www.jsog.or.jp/activity/art/2022_JSOG‐ART.pdf). ET, embryo transfer.

3.1. Treatment and pregnancy outcomes

The detailed characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered fresh cycles are shown in Table 2. In 2022, 85 124 IVF cycles, 34 581 split‐ICSI cycles, 150 958 ICSI cycles using ejaculated spermatozoa, 2277 ICSI cycles using testicular sperm extraction (TESE), 2628 cycles for oocyte freezing, and 3650 other cycles were registered. In total, 275 296 cycles resulted in oocyte retrieval, of which 158 247 (57.5%) were freeze‐all cycles. The pregnancy rate was 24.6% per ET cycle of IVF, and 19.2% for ICSI using ejaculated spermatozoa. The total single ET rate was 82.4%, and the pregnancy rate following a single ET cycle was 22.6%. Live birth rates per ET were 17.4% for IVF, 19.0% for split‐ICSI, 13.5% for ICSI using ejaculated spermatozoa, and 8.6% for ICSI with TESE. There were 6556 singleton pregnancies and 4758 singleton live births. In 2022, 2628 cycles for oocyte freezing were registered, and 2608 oocyte retrievals were conducted. Of these, 2402 cycles led to successfully frozen oocytes. The singleton pregnancy rate was 97.2%, and the singleton live birth rate was 97.4%.

TABLE 2.

Characteristics and treatment outcomes of registered fresh cycles in assisted reproductive technology in Japan, 2022.

| Variables | IVF | Split‐ICSI | ICSI | Frozen oocyte | Other a | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ejaculated sperm | TESE | ||||||

| No. of registered cycles | 85 124 | 34 581 | 150 958 | 2277 | 2628 | 3650 | 279 218 |

| No. of egg retrievals (0 or more) | 83 586 | 34 293 | 148 923 | 2273 | 2608 | 3613 | 275 296 |

| No. of fresh ET cycles (1 or more) | 11 951 | 2907 | 16 088 | 304 | 0 | 260 | 31 510 |

| No. of freeze‐all cycles | 45 068 | 27 010 | 80 436 | 1368 | 2402 | 1963 | 158 247 |

| No. of cycles with pregnancy | 2942 | 752 | 3084 | 42 | 0 | 65 | 6885 |

| Pregnancy rate per ET | 24.6% | 25.9% | 19.2% | 13.8% | 25.0% | 21.9% | |

| Pregnancy rate per egg retrieval | 3.5% | 2.2% | 2.1% | 1.9% | 1.8% | 2.5% | |

| Pregnancy rate per egg retrieval excluding freeze‐all cycles | 4.5% | 3.6% | 2.7% | 2.6% | 2.0% | 3.3% | |

| SET cycles | 10 321 | 2529 | 12 721 | 186 | 220 | 25 977 | |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 2586 | 686 | 2515 | 32 | 61 | 5880 | |

| Rate of SET cycles | 86.4% | 87.0% | 79.1% | 61.2% | 84.6% | 82.4% | |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 25.1% | 27.1% | 19.8% | 17.2% | 27.7% | 22.6% | |

| Miscarriages | 709 | 158 | 785 | 14 | 12 | 1678 | |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 24.1% | 21.0% | 25.5% | 33.3% | 18.5% | 24.4% | |

| Singleton pregnancies b | 2801 | 720 | 2931 | 41 | 63 | 6556 | |

| Multiple pregnancies b | 74 | 20 | 90 | 0 | 2 | 186 | |

| Twin pregnancies | 73 | 20 | 88 | 0 | 0 | 183 | |

| Triplet pregnancies | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| Quadruplet pregnancies | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Multiple pregnancy rate | 2.6% | 2.7% | 3.0% | 0.0% | 3.1% | 2.8% | |

| Live births | 2082 | 553 | 2172 | 26 | 50 | 4883 | |

| Live birth rate per ET | 17.4% | 19.0% | 13.5% | 8.6% | 19.2% | 15.5% | |

| Total no. of neonates | 2133 | 568 | 2228 | 26 | 50 | 5005 | |

| Singleton live births | 2031 | 538 | 2113 | 26 | 50 | 4758 | |

| Twin live births | 51 | 15 | 56 | 0 | 0 | 122 | |

| Triplet live births | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Quadruplet live births | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ectopic pregnancies | 39 | 4 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 84 | |

| Heterotopic pregnancies | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Artificial abortions | 11 | 4 | 19 | 1 | 1 | 36 | |

| Still births | 12 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 22 | |

| Fetal reductions | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Cycles with unknown pregnancy outcomes | 57 | 27 | 47 | 0 | 1 | 132 | |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; IVF, in vitro fertilization; SET, single embryo transfer; TESE, testicular sperm extraction; ZIFT, zygote intrafallopian transfer.

Others include ZIFT.

Singleton, twin, triplet, and quadruplet pregnancies were defined on the basis of the number of gestational sacs in utero.

Table 3 summarizes the characteristics and treatment outcomes of FET cycles. In 2022, a total of 264 015 cycles were registered. Of these, 262 146 were registered as FET cycles. Of the latter, 258 217 FETs were conducted. With a pregnancy rate of 37.8%, FET cycles resulted in 97 664 pregnancies. FET cycles resulted in 24 969 miscarriages. The miscarriage rate per pregnancy was 25.6%, and the live birth rate per FET increased slightly to 27.0% from 26.6% observed in 2021. The single ET rate was 85.3%, somewhat higher than in 2021 (84.9%), resulting in a slightly increased pregnancy rate of 38.8% from 38.1% in 2021. The rate of singleton pregnancies was 96.9%, and singleton live births was 96.9%.

TABLE 3.

Characteristics and treatment outcomes of frozen cycles in assisted reproductive technology in Japan, 2022.

| Variables | FET | Other a | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of registered cycles | 262 146 | 1869 | 264 015 |

| No. of FET | 258 217 | 1688 | 259 905 |

| No. of cycles of pregnancy | 97 664 | 643 | 98 307 |

| Pregnancy rate per FET | 37.8% | 38.1% | 37.8% |

| SET cycles | 220 292 | 1386 | 221 678 |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 85 432 | 538 | 85 970 |

| Rate of SET cycles | 85.3% | 82.1% | 85.3% |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 38.8% | 38.8% | 38.8% |

| Miscarriages | 24 969 | 181 | 25 150 |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 25.6% | 28.2% | 25.6% |

| Singleton pregnancies b | 93 406 | 617 | 94 023 |

| Multiple pregnancies b | 3000 | 16 | 3016 |

| Twin pregnancies | 2939 | 16 | 2955 |

| Triplet pregnancies | 54 | 0 | 54 |

| Quadruplet pregnancies | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Quintuplet pregnancies | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Multiple pregnancy rate | 3.1% | 2.5% | 3.1% |

| Live births | 69 834 | 435 | 70 269 |

| Live birth rate per FET | 27.0% | 25.8% | 27.0% |

| Total no. of neonates | 71 733 | 446 | 72 179 |

| Singleton live births | 67 646 | 424 | 68 070 |

| Twin live births | 2018 | 11 | 2029 |

| Triplet live births | 17 | 0 | 17 |

| Quadruplet live births | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ectopic pregnancies | 476 | 1 | 477 |

| Heterotopic pregnancies | 23 | 0 | 23 |

| Artificial abortions | 436 | 4 | 440 |

| Stillbirths | 239 | 5 | 244 |

| Fetal reductions | 18 | 0 | 18 |

| Cycles with unknown pregnancy outcomes | 1430 | 8 | 1438 |

Abbreviations: FET, frozen–thawed embryo transfer; SET, single embryo transfer.

Including cycles using frozen–thawed oocytes.

Singleton, twin, triplet, and quadruplet pregnancies were defined on the basis of the number of gestational sacs in utero.

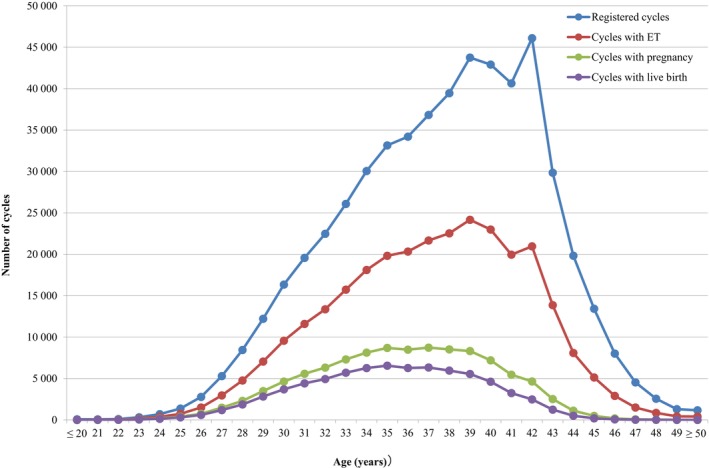

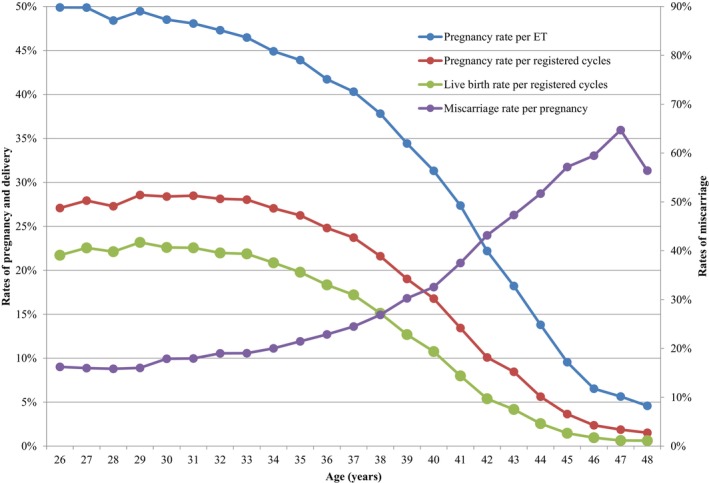

3.2. Outcomes by patient age

Table 4 shows the treatment outcomes of registered cycles by patient age in Japan in 2022. The pregnancy rate per ET exceeded 40% for women aged between 21 and 37 years. Gradual decreases in pregnancy rates per ET were observed with increasing maternal age, starting at age 26 years. Rates fell below 30% for women aged >41 years, below 20% among women aged >43 years, below 10% for women aged >45 years, and below 5% for women aged >48 years. The miscarriage rates tended to be below 20% for all women aged between 22 and 34 years and increased gradually with increasing maternal age. Women in their early forties had miscarriage rates generally between 33% and 52%, while women in their mid‐forties had miscarriage rates over 57%. The live birth rate per registered cycle was the highest for women aged 29 years (23.2%). Rates declined sharply to below 15.0% at 39 years of age and below 10.0% among women >41 years of age.

TABLE 4.

Treatment outcomes of registered cycles based on patient age in Japan, 2022.

| Age (years) | No. of registered cycles | No. of ET cycles | No. of cycles with pregnancy | Multiple pregnancies | Miscarriage | Cycles with live birth | Pregnancy rate/registered ET (%) | Pregnancy rate/registered cycles (%) | Live birth rate/registered cycles | Miscarriage rate (%) | Multiple pregnancy rate (%) a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤20 | 80 | 8 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 50.0 | 5.0 | 3.8 | 25.0 | 0.0 |

| 21 | 73 | 32 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 40.6 | 17.8 | 12.3 | 15.4 | 8.3 |

| 22 | 106 | 46 | 25 | 1 | 7 | 18 | 54.4 | 23.6 | 17.0 | 28.0 | 4.0 |

| 23 | 321 | 155 | 72 | 3 | 10 | 60 | 46.5 | 22.4 | 18.7 | 13.9 | 4.2 |

| 24 | 704 | 379 | 182 | 6 | 37 | 141 | 48.0 | 25.9 | 20.0 | 20.3 | 1.7 |

| 25 | 1375 | 730 | 386 | 24 | 50 | 317 | 52.9 | 28.1 | 23.1 | 13.0 | 3.5 |

| 26 | 2777 | 1507 | 752 | 20 | 122 | 603 | 49.9 | 27.1 | 21.7 | 16.2 | 2.0 |

| 27 | 5290 | 2961 | 1477 | 72 | 236 | 1193 | 49.9 | 27.9 | 22.6 | 16.0 | 3.4 |

| 28 | 8452 | 4764 | 2306 | 92 | 365 | 1869 | 48.4 | 27.3 | 22.1 | 15.8 | 2.7 |

| 29 | 12 217 | 7054 | 3489 | 148 | 559 | 2831 | 49.5 | 28.6 | 23.2 | 16.0 | 3.1 |

| 30 | 16 342 | 9563 | 4639 | 196 | 830 | 3692 | 48.5 | 28.4 | 22.6 | 17.9 | 3.3 |

| 31 | 19 571 | 11 596 | 5574 | 215 | 1000 | 4415 | 48.1 | 28.5 | 22.6 | 17.9 | 2.7 |

| 32 | 22 481 | 13 366 | 6323 | 236 | 1201 | 4939 | 47.3 | 28.1 | 22.0 | 19.0 | 2.5 |

| 33 | 26 083 | 15 732 | 7312 | 312 | 1391 | 5704 | 46.5 | 28.0 | 21.9 | 19.0 | 3.0 |

| 34 | 30 060 | 18 109 | 8132 | 319 | 1628 | 6268 | 44.9 | 27.1 | 20.9 | 20.0 | 2.9 |

| 35 | 33 153 | 19 818 | 8702 | 394 | 1867 | 6558 | 43.9 | 26.3 | 19.8 | 21.5 | 3.0 |

| 36 | 34 198 | 20 337 | 8486 | 392 | 1940 | 6271 | 41.7 | 24.8 | 18.3 | 22.9 | 3.3 |

| 37 | 36 825 | 21 664 | 8734 | 389 | 2138 | 6335 | 40.3 | 23.7 | 17.2 | 24.5 | 3.2 |

| 38 | 39 450 | 22 535 | 8522 | 416 | 2290 | 5960 | 37.8 | 21.6 | 15.1 | 26.9 | 3.6 |

| 39 | 43 750 | 24 167 | 8320 | 377 | 2517 | 5550 | 34.4 | 19.0 | 12.7 | 30.3 | 3.4 |

| 40 | 42 903 | 22 990 | 7199 | 337 | 2344 | 4616 | 31.3 | 16.8 | 10.8 | 32.6 | 3.3 |

| 41 | 40 639 | 19 954 | 5460 | 231 | 2047 | 3249 | 27.4 | 13.4 | 8.0 | 37.5 | 3.3 |

| 42 | 46 095 | 20 960 | 4651 | 219 | 2007 | 2484 | 22.2 | 10.1 | 5.4 | 43.2 | 3.2 |

| 43 | 29 849 | 13 859 | 2524 | 98 | 1194 | 1246 | 18.2 | 8.5 | 4.2 | 47.3 | 2.6 |

| 44 | 19 824 | 8085 | 1116 | 45 | 577 | 508 | 13.8 | 5.6 | 2.6 | 51.7 | 2.5 |

| 45 | 13 425 | 5131 | 490 | 13 | 280 | 197 | 9.6 | 3.6 | 1.5 | 57.1 | 1.7 |

| 46 | 8019 | 2908 | 190 | 7 | 113 | 77 | 6.5 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 59.5 | 1.6 |

| 47 | 4542 | 1506 | 85 | 3 | 55 | 29 | 5.6 | 1.9 | 0.6 | 64.7 | 0.0 |

| 48 | 2561 | 851 | 39 | 1 | 22 | 16 | 4.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 56.4 | 0.0 |

| 49 | 1302 | 432 | 17 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 3.9 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 47.1 | 11.8 |

| ≥50 | 1163 | 412 | 12 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 2.9 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 50.0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 543 630 | 291 611 | 105 233 | 4571 | 26 844 | 75 172 | 36.1 | 19.4 | 13.8 | 25.5 | 3.1 |

Abbreviation: ET, embryo transfer.

Multiple pregnancies were defined on the basis of the number of gestational sacs in utero.

Figure 2 shows the rates of pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage by patient age in all registered cycles in 2022. Of note, the pregnancy rate per ET was around 50% at ages 26 and 27 and generally above 45% between ages 28 and 34 years. There was then a progressive decline from that point, which became even more marked beyond the age of 40 years, similar to that reported in the previous year. Similar trends were observed for pregnancy and live birth rates (below 30% and 25%, respectively), with progressive declines starting as early as 35 years of age. Conversely, miscarriage rates gradually increased from the early thirties up to 38 years of age and increased rapidly thereafter until the late forties.

FIGURE 2.

Pregnancy, live birth, and miscarriage rates according to patient age in all registered cycles 2022. Adapted from the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology ART Databook 2022 (https://www.jsog.or.jp/activity/art/2022_JSOG‐ART.pdf). ET, embryo transfer.

3.3. Treatment outcomes for FET cycles using frozen–thawed oocytes

Table 5 shows the primary treatment outcomes of embryo transfers using frozen–thawed oocytes in Japan in 2022. In 2022, 397 cycles using frozen–thawed oocytes were registered in Japan, of which 196 FETs were actually implemented. Forty‐one pregnancies were achieved, with a pregnancy rate per FET of 20.9% and a live birth rate of 10.2%. The miscarriage rate per pregnancy was 39.0%.

TABLE 5.

Treatment outcomes of embryo transfers using frozen–thawed oocyte in assisted reproductive technology in Japan, 2022.

| Variables | Embryo transfers using frozen–thawed oocytes |

|---|---|

| No. of registered cycles | 397 |

| No. of ET | 196 |

| No. of cycles with pregnancy | 41 |

| Pregnancy rate per ET | 20.9% |

| SET cycles | 120 |

| Pregnancy following SET cycles | 29 |

| Rate of SET cycles | 61.2% |

| Pregnancy rate following SET cycles | 24.2% |

| Miscarriages | 16 |

| Miscarriage rate per pregnancy | 39.0% |

| Singleton pregnancies a | 36 |

| Multiple pregnancies a | 1 |

| Twin pregnancies | 1 |

| Triplet pregnancies | 0 |

| Quadruplet pregnancies | 0 |

| Multiple pregnancy rate | 2.7% |

| Live births | 20 |

| Live birth rate per ET | 10.2% |

| Total number of neonates | 22 |

| Singleton live births | 18 |

| Twin live births | 2 |

| Triplet live births | 0 |

| Quadruplet live births | 0 |

| Ectopic pregnancies | 0 |

| Intrauterine pregnancies coexisting with ectopic pregnancy | 0 |

| Artificial abortions | 1 |

| Still births | 1 |

| Fetal reductions | 0 |

| Cycles with unknown pregnancy outcomes | 2 |

Abbreviations: ET, embryo transfer; SET, single embryo transfer.

Singleton, twin, triplet, and quadruplet pregnancies were defined on the basis of the number of gestational sacs in utero.

4. DISCUSSION

We described the characteristics and outcomes of ART cycles registered in the Japanese ART registry system during 2022 and compared the present results with those from 2021 17 and previous years. 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 The main findings of the Japanese ART registry in 2022 were as follows: in 2022, 543 630 cycles were registered; 105 233 pregnancies and a total of 77 206 neonate births were recorded by the JSOG in Japan.

In 2022, there were significant increases in ART cycles. IVF cycles increased by 3.4%, and ICSI cycles increased by 10.3%. Freeze‐all cycles accounted for 57.5% of cycles with oocyte retrieval, resulting in a 3.7% decrease in neonates born from IVF‐ET cycles and a 1.0% decrease in those born from ICSI cycles. FET cycles also increased by 10.4%. A total of 210 322 cycles (38.7%) were for cycles in women aged 40 years or over. The total single ET and singleton pregnancy rates for fresh cycles were 82.4% and 97.2%, respectively, and the singleton live birth rate was 97.4%. For frozen cycles, the single ET rate was 85.3%. The rates of singleton pregnancies and singleton live births were both 96.9%.

This report also reflects the impact of the first year since the expansion of insurance coverage for ART (April 2022). This expansion is perhaps the most impactful influence on the increase in the number of ART treatments in Japan, with an increased number of cycles and live births in 2022 (543 630 and 77 206, respectively) compared with 2021 (498 140 and 69 797, respectively). 17 This coverage marks a significant improvement in access to fertility treatments in Japan. It not only alleviates the financial burden on patients but also represents a crucial step toward equity in reproductive health care. For low‐income couples who aspire to become parents, the cost of ART can be prohibitively high, often leading to emotional distress and limiting their options. With insurance coverage, these couples can pursue treatments without the constant worry of overwhelming expenses, thereby fostering a more supportive environment for family planning. In addition, young couples, who may be navigating the challenges of establishing their careers and finances, also stand to benefit significantly. By reducing the out‐of‐pocket costs associated with ART, insurance coverage enables them to make informed decisions about starting a family without the immediate pressure of financial constraints.

Additionally, the implementation of the “High‐cost Medical Expense Benefit” is a noteworthy aspect of this initiative. If the copayment, calculated on the basis of certain standards, exceeds the maximum, the excess amount will be paid as High‐cost Medical Care Benefits. This program provides further financial support to individuals who face very high medical expenses, ensuring that those requiring extensive ART services are not unduly burdened. 23 By minimizing the financial risks associated with fertility treatments, this benefit can enhance treatment adherence and, ultimately, improve reproductive outcomes.

Some patients may face greater financial strain, even under the new insurance coverage system. Several local governments have started offering subsidies for advanced ART treatments not covered by public insurance. Such treatments are combined with ART procedures and are usually paid for entirely by the patient. The effect of those additional subsidies—especially for boosting the fertility rate—are, as yet, unknown. Despite being the most accessible region for ART treatments, Tokyo has the lowest fertility rate. 24 This suggests that simply reducing the financial burden of ART may not be enough to improve fertility trends.

The current system is well organized, but concerns have been raised about developing new ART treatments. Individual clinics usually innovate and develop new ART treatments, but insurance coverage seems to focus on standardized procedures. This could be, in part, because standardized treatments have established success rates and are easier to regulate and cover under insurance policies. As new treatments emerge, integrating them into the existing system, which currently leans toward standard ART, may pose certain challenges.

Another important factor that may limit families from receiving the ART insurance coverage benefit is that the couple's relationship is also scrutinized. 25 In Japan, there is no specific legislation governing the use of third‐party gametes or embryos for ART. JSOG provides guidelines, but these are not legally binding. 26 , 27 Thus, ongoing discussion is needed regarding the creation of more comprehensive regulations. 28

In 2022, out of 2628 oocyte freezing cycles, 2402 resulted in successfully frozen oocytes, while in 2021, out of 1103 cycles, 830 resulted in the successful freezing of oocytes. This represents success rates of approximately 91.4% in 2022 and approximately 75.2% in 2021, indicating a considerable increase in the success rate of oocyte freezing from 2021 to 2022. 17

Several factors could contribute to this improvement. Fertility preservation in Japan, especially for medical reasons such as cancer, has become more popular. The Japanese government has established subsidy systems to support this. Patients can apply for subsidies from both local and central governments to help cover the costs of fertility preservation and subsequent ART. 29 , 30 Advances in cryopreservation techniques, such as vitrification, have improved oocyte survival rates during freezing and thawing, 31 , 32 with live birth rates varying based on the age at which oocytes were frozen. 31 The higher number of oocyte freezing in 2022 compared with 2021 underscores the positive impact of both technological advancements and diffusion of fertility preservation using ART in Japan.

The pregnancy rate per FET cycle has shown a secular trend, with a slight increase from 36.9% in 2021 to 37.8% in 2022. This trend is an interesting finding and might be influenced by the introduction of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT‐A) in Japan, following a clinical trial conducted by the JSOG. 33 PGT‐A helps select chromosomally normal embryos, potentially improving implantation and pregnancy rates per embryo transfer. 34 Because of this technique, the single ET rate might increase for FET. In the future, it may be beneficial to assess pregnancy rates separately by PGT‐A status in FET cycles.

This study has some strengths and limitations that have been previously reported. 17

The main strength is that registered ART facilities nationwide must provide annual reports, leading to high reporting compliance. Furthermore, the standardization of procedures and definitions for cycle‐specific information across registered ART facilities has reduced reporting bias. A major limitation is that some data for which collection is not standardized, such as background information, may be more likely incomplete or missing. Furthermore, the registration procedure is somewhat cumbersome in that participating ART facilities are assumed to register cycle‐specific information manually one‐by‐one. Therefore, it is possible that burdens relating to data input are very high and that errors might occur. To address this, the JSOG has launched a subcommittee to debate an effective registration system from 2024, and aims to introduce a batch registration system in the near future.

The 2022 ART data analysis from the Japanese ART registry administered by the JSOG highlights significant growth in ART cycles and outcomes, reflecting the impact of the recent expansion of insurance coverage. Despite the increase in ART cycles, success rates and outcomes vary by age, emphasizing the need for continued advancements and monitoring regarding ART treatments. The data underscore the importance of age in ART outcomes, with higher pregnancy and live birth rates among younger age groups. The expansion of insurance coverage and local government subsidies have contributed to a notable increase in ART use in Japan. However, financial strain and regional disparities in fertility rates suggest that further measures are needed to address underlying challenges and improve overall fertility trends. This annual analysis is essential to comprehending the changing trends and patterns in ART, especially given the continuously declining fertility rate, growing elderly population, and decreasing population growth worldwide, particularly in Japan. As Japan continues to lead ART, integrating new treatments into the standardized insurance‐covered procedures will be crucial. Addressing the financial and logistical barriers faced by patients, especially in regions with lower fertility rates, will be essential for sustaining and enhancing the success of ART programs.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose about the present work. “Seung Chik, Jwa”, “Akira, Iwase”, “Takeshi, Iwasa”, are an Editorial Board member of Reproductive Medicine and Biology and a coauthor of this article. To minimize bias, they were excluded from all editorial decision‐making related to the acceptance of this article for publication.

HUMAN RIGHTS STATEMENTS AND INFORMED CONSENT

All procedures were performed according to the ethical standards of the relevant committees on human experimentation (institutional and national), as well as the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.

ANIMAL RIGHTS

This report contains no studies performed by any authors that included animals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank all of the registered facilities for their cooperation in providing their responses and encourage these facilities to continue promoting the use of the online registry system and assisting us with our research. The authors also thank Keyra Martinez Dunn, MD of Edanz (www.edanz.com), for providing medical writing support.

Katagiri Y, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, Iwasa T, Ono M, Kato K, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: A summary report for 2022 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2024;23:e12620. 10.1002/rmb2.12620

REFERENCES

- 1. National Institute of Population and Social Security Research . 2020. [Cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.ipss.go.jp/syoushika/tohkei/Popular/Popular2020.asp?chap=0

- 2. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Handbook of Health and Welfare Statistics 2023. Table 1‐20 Total fertility rates by year. 2021. [Cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db‐hh/1‐2.html

- 3. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare . Summary of vital statistics. [Cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db‐hw/populate/index.html

- 4. World Bank Group . Fertility rate, total (births per woman). [Cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN

- 5. Ghaznavi C, Sakamoto H, Yamasaki L, Nomura S, Yoneoka D, Shibuya K, et al. Salaries, degrees, and babies: trends in fertility by income and education among Japanese men and women born 1943‐1975‐analysis of national surveys. PLoS One. 2022;17(4):e0266835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Okui T. Marriage and fertility rates of Japanese women according to employment status: an age‐period‐cohort analysis. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2020;67(12):892–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Frejka T, Jones GW, Sardon JP. East Asian childbearing patterns and policy developments. Popul Dev Rev. 2010;36(3):579–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Imai Y, Endo M, Kuroda K, Tomooka K, Ikemoto Y, Sato S, et al. Risk factors for resignation from work after starting infertility treatment among Japanese women: Japan‐female employment and mental health in assisted reproductive technology (J‐FEMA) study. Occup Environ Med. 2020;78(6):426–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Atoh M. Thinking about very low fertility rate in Japan, based upon its demographic analysis. J Health Care Soc. 2017;27(1):5–20. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 10. Okui T, Nakashima N. Exploring the association between non‐regular employment and adverse birth outcomes: an analysis of national data in Japan. Ann Occup Environ Med. 2024;36:e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Parsons AJQ, Gilmour S. An evaluation of fertility‐ and migration‐based policy responses to Japan's ageing population. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baba S, Goto A, Reich MR. Looking for Japan's missing third baby boom. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44(2):199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . Support for infertility treatment. [Cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/000901931.pdf

- 14. Harada S, Yamada M, Shirasawa H, Jwa SC, Kuroda K, Harada M, et al. Fact‐finding survey on assisted reproductive technology in Japan. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2023;49(11):2593–2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Katagiri Y, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, Iwasa T, Ono M, Kato K, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report for 2020 by the ethics Committee of the Japan Society of obstetrics and gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2023;22(1):e12494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kupka MS, Chambers GM, Dyer S, Zegers‐Hochschild F, de Mouzon J, Ishihara O, et al. International Committee for Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technology world report: assisted reproductive technology, 2015 and 2016. Fertil Steril. 2024;112(24):875–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Katagiri Y, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, Iwasa T, On M, Kato K, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report for 2021 by the ethics Committee of the Japan Society of obstetrics and gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2023;23(1):e12552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Irahara M, Kuwahara A, Iwasa T, Ishikawa T, Ishihara O, Kugu K, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report of 1992‐2014 by the ethics committee, Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2017;16(2):126–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ishihara O, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, Katagiri Y, Kuwabara Y, Hamatani T, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report for 2018 by the ethics Committee of the Japan Society of obstetrics and gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2020;20(1):3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ishihara O, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, Katagiri Y, Kuwabara Y, Hamatani T, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report for 2017 by the ethics Committee of the Japan Society of obstetrics and gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2019;19(1):3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ishihara O, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, Ishikawa T, Kugu K, Sawa R, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report for 2016 by the ethics Committee of the Japan Society of obstetrics and gynecology. Reprod. Med Biol. 2018;18(1):7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saito H, Jwa SC, Kuwahara A, Saito K, Ishikawa T, Ishihara O, et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report for 2015 by the ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2017;17(1):20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Central Medical Council . Revision of medical remuneration. Individual Matters (No. 4). 2022. [Cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12404000/001171707.pdf

- 24. Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan . Overview of the annual report (estimated figures) of the population dynamics statistics monthly report for the year 2023. Table 5. [Cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/geppo/nengai23/dl/kekka.pdf

- 25. Taisho Pharmaceutical . Infertility treatment is now covered by insurance! What changed? What are the advantages, disadvantages, and challenges? [Cited 2024 Oct 10]. Available from: https://www.taisho‐kenko.com/column/84/

- 26. Yamamoto N, Hirata T, Izumi G, Nakazawa A, Fukuda S, Neriishi K, et al. A survey of public attitudes towards third‐party reproduction in Japan in 2014. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0198499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Croydon S. Reluctant rulers: policy, politics, and assisted reproduction technology in Japan. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2023;32:289‐299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Semba Y, Chang C, Hong H, Kamisato A, Kokado M, Muto K. Surrogacy: donor conception regulation in Japan. Bioethics. 2010;24(7):348–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ono M, Takai Y, Harada M, Horie A, Dai Y, Kikuchi E, et al. Out‐of‐pocket fertility preservation expenses: data from a Japanese nationwide multicenter survey. Int J Clin Oncol. 2024;29:1959–1966. 10.1007/s10147-024-02614-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Harada M, Kimura F, Takai Y, Nakajima T, Ushijima K, Kobayashi H, et al. Japan Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guidelines 2017 for fertility preservation in childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer patients: part 1. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;27:265–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hirsch A, Hirsh Raccah B, Rotem R, Hyman JH, Ben‐Ami I, Tsafrir A. Planned oocyte cryopreservation: a systematic review and meta‐regression analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2024;30(5):558–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Han E, Seifer DB. Oocyte cryopreservation for medical and planned indications: a practical guide and overview. J Clin Med. 2023;12(10):3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Iwasa T, Kuwahara A, Takeshita T, Taniguchi Y, Mikami M, Irahara M. Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy and chromosomal structural rearrangement: a summary of a nationwide study by the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod Med Biol. 2023;22(1):e12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tian Y, Li M, Yang J, Chen H, Lu D. Preimplantation genetic testing in the current era, a review. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;309(5):1787–1799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]