Abstract

Objective

To evaluate chronic conditions as leading predictors of economic burden over time among older adults with incident primary Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC) using machine learning methods.

Methods

We used a retrospective cohort of older adults (age ≥ 67 years) diagnosed with MCC between 2009 and 2019. For these elderly MCC patients, we derived three phases (pre-diagnosis, during-treatment, and post-treatment) anchored around cancer diagnosis date. All three phases had 12 months baseline and 12-months follow-up periods. Chronic conditions were identified in baseline and follow-up periods, whereas annual total and out-of-pocket (OOP) healthcare expenditures were measured during the 12-month follow-up. XGBoost regression models and SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) methods were used to identify leading predictors and their associations with economic burden.

Results

Congestive heart failure (CHF), chronic kidney disease (CKD) and depression had the highest average incremental total expenditures during pre-diagnosis, treatment, and post-treatment phases, respectively ($25,004, $24,221, and $16,277 (CHF); $22,524, $19,350, $20,556 (CKD); and $21,645, $22,055, $18,350 (depression)), whereas the average incremental OOP expenditures during the same periods were $3703, $3,013, $2,442 (CHF); $2,457, $2,518, $2,914 (CKD); and $3,278, $2,322, $2,783 (depression). Except for hypertension and HIV, all chronic conditions had higher expenditures compared to those without the chronic conditions. Predictive models across each of phases of care indicated that CHF, CKD, and heart diseases were among the top 10 leading predictors; however, their feature importance ranking declined over time. Although depression was one of the leading drivers of expenditures in unadjusted descriptive models, it was not among the top 10 predictors.

Conclusion

Among older adults with MCC, cardiac and renal conditions were the leading drivers of total expenditures and OOP expenditures. Our findings suggest that managing cardiac and renal conditions may be important for cost containment efforts.

Keywords: Merkel cell carcinoma, healthcare expenditures, chronic conditions, XGBoost, SHAP, SEER-Medicare

Introduction

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare and aggressive neuroendocrine skin cancer that predominantly affects older adults, with a higher incidence in non-Hispanic White males, individuals with immunosuppression, and those with extensive sun exposure.1 The disease often presents as a rapidly growing, pink-red nodule on sun-exposed areas, such as the head and neck, upper limbs, or trunk.1 Prognosis for MCC is generally poor due to its high propensity for early metastasis and recurrence; the 5-year survival rate is around 51% for localized disease, with a significant drop at advanced stages.2,3 Treatment options for MCC vary based on the stage at diagnosis. Surgical excision with or without radiotherapy is the standard approach for localized cases, although recurrence rates remain high.2 For advanced or metastatic MCC, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as pembrolizumab and nivolumab, have shown promising results in improving outcomes, offering significant survival benefits compared to traditional chemotherapy, which is associated with high toxicity and limited duration of response.2,3

In the United States, cancer imposes a significant financial burden on patients, families, payers, and society.4 As the number of cancer survivors grow each year due to the changing treatment landscape and subsequent improvements in survival, cancer survivors continue to consume healthcare resources for cancer survivorship care.5 In 2010, the national estimate of cancer costs in the United States was $158 billion; in 2018, they soared to $183 billion, and are projected to be $245 billion by 2030.6,7

As the cancer treatment landscape is becoming costly, a greater portion of cancer and survivorship care is shifting to the patient, resulting in a significant financial burden for many cancer patients in the US. Immunotherapy became the treatment of choice for advanced MCC.8 However, a recent study found that total costs, driven by pharmacy costs, were higher for ICIs compared to chemotherapy, while other departmental costs were similar for both ICIs and chemotherapy.9 It is estimated that 22–64% of patients report financial struggles following a cancer diagnosis.6 After all, the national patient economic burden of cancer care is estimated at $21.09 billion in the United States and includes $16.22 billion in out-of-pocket (OOP) and $4.87 billion in patient indirect expenditures (patient out-of-pocket and time costs).10 Adult patients and caregivers spent on average $180 and $2,600 per month, and about 42% to 16% of their annual income on OOP expenses, respectively.11

With the over 200 types of cancer, there is no “one-size-fits all” approach to cancer management,12 and thus the economic burden can vary by cancer type, cancer stage, and phase of cancer.11,13,14 However, many studies included in a recent review have focused on the highly prevalent breast, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers.15 Studies on MCC, a rare and aggressive form of non-melanoma skin cancer, diagnosed in the elderly are limited.2,16,17 The investigation of the economic burden of MCC has largely focused on cost of treatment among advanced stages. Total annual average healthcare expenditures per patient were $56,124 for surgery (SRx) only, $93,830 for radiotherapy (RTx) only, and $154,506 for chemotherapy (CTx) only.18 Total annual healthcare costs based on poly-therapeutic regimens including RTx and SRx only averaged $104,980, whereas regimens with SRx, RTx, and CTx only averaged $134,730.18 Moreover, with the improvement in 5-year overall survival rates of MCC as a result of novel therapies (~80% in local stages; >50% in regional stages; ~40% in distant stages),19 the cost may continue to increase beyond the initial treatment.

Furthermore, the cost of care for elderly MCC patients is driven primarily by age, and comorbidities.12,20 Older adults make up 62% of the overall cancer survivor population. In this population, moderate physical comorbidities range from 13% to 72.9%, whereas severe comorbidities range from 2.5% to 68.2%.21 These comorbidities affect cancer care as older cancer patients are less likely to be offered curative treatment and instead are administered less vigorous and nonstandard treatment.21 In cancer survivors with chronic conditions – often labeled as “super patients”20, comorbidities affect the cancer stage in an unknown manner.22 An acute cancer diagnosis with an underlying chronic conditions creates unforeseen treatment complications and competing healthcare demands in terms of negotiating silos across medical management teams.23

Evaluating the impact of chronic conditions on healthcare expenditures among elderly MCC patients is important for several reasons. Policy efforts such as the introduction of value-based care model (a care model aiming to improve health outcomes achieved per dollar spent)24 by the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services have aimed at improving care coordination25 and by extent mitigate the high costs of cancer care. Furthermore, a major federal policy has been the institution of accountable care organizations (ACO) to control rising costs, and these organizations need risk adjustments to determine expenditure benchmarks for shared savings from Medicare. Studies that provide information on cost of cancer per beneficiary during various phases are important for such risk adjustment. Furthermore, in the literature, expenditures comparison typically includes the initial phase of care (first year of diagnosis), the end-of-life phase, and the maintenance phase (between the initial and end-of-life phase). Thus, a difference in expenditure predictors in the short term would be more informative of their immediate burden. Therefore, the primary objective of the study is to estimate healthcare expenditures associated with chronic conditions and evaluate whether chronic conditions continue to influence total and OOP healthcare expenditures over three phases of cancer care (pre-diagnosis, during-treatment, and post-treatment) among older adults with incident MCC.

Methods

Study Design

This study employed a retrospective cohort study of older adults (≥67 years at incident MCC diagnosis date) identified using the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition histologic (ICD-O-3[8247]) and behavior (ICD-O-3[3]) codes in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry.

Data Sources

This study used the SEER-Medicare database, which is a private database acquired from the division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences of the National Cancer Institute in the United States. The West Virginia University Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained (#2203549606). Patient consent was not deemed necessary by the IRB.

SEER-Medicare data combine the following databases: 1) 18 registries pooled into the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry; 2) Enrollment files from Medicare; 3) Medicare service claims; and 4) zip code census data for Medicare beneficiaries of interest. We further augmented the dataset with county-level area health resource files (AHRF), and County Health Ranking data (CHRF) by linking with county identifiers available in SEER-Medicare. The SEER registry records cancer site, stage, diagnosis date, vital status, and cause of death for residents in its catchment areas. Medicare enrollment files include demographic data, coverage details (Parts A, B, D, Medicare Advantage, and dual Medicaid/Medicare). Medicare claims data cover diagnosis, treatment, and payments, including hospital care, physician services, durable medical equipment, hospice, and home health care. Part D prescription drug event data track payments and dates for oral prescription drugs.

Cancer data obtained from the SEER registry were cross-referenced with Medicare claims, employing encrypted patient identifiers. Socioeconomic indicators at the zip code level, such as income and educational attainment, were supplied by SEER and subsequently harmonized with individual patient records utilizing the zip codes of residence derived from Medicare claims. County and regional data from the Area Health Resources File (AHRF) and the County Health Rankings and Roadmaps File (CHRF) were linked to the SEER-Medicare dataset via Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS) state and county codes. The AHRF provides comprehensive county-level information encompassing healthcare infrastructure, healthcare workforce, resource availability, health status, economic activities, health education programs, and socioeconomic characteristics. In contrast, the CHRF delivers county-level insights into health-related behaviors, clinical care, societal and economic determinants, as well as the physical environment.

Study Period

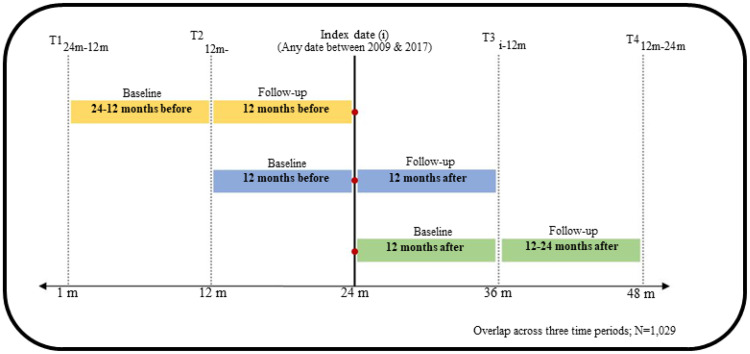

The observation period spanned from 2007 through 2019 for incident MCC diagnosed between 2009 and 2017. The availability of Medicare Part D in 2007 influenced this decision. Using the diagnosis date as an anchor point, we defined the following four time points as shown in Figure 1: 24 months before diagnosis (pre-diagnosis), 12 months before diagnosis, 12 months after diagnosis (during-treatment), and 24 months after diagnosis (post-treatment). We selected three different phases of two years each, where we longitudinally followed MCC beneficiaries (based on continuous Medicare enrollment). The three study phases, namely pre-diagnosis, during-treatment, and post-treatment included 1,742, 1,466, and 1,221 elderly MCC patients who met our inclusion criteria. Across all phases, 1,029 beneficiaries met all the inclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Study Design, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims files, Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries with Incident Merkel Cell Carcinoma, 2009–2017.

Each phase had baseline and follow-up periods. The pre-diagnosis phase contained 24 months before cancer diagnosis with 12 months baseline and 12 months follow-up. The treatment phase consisted of 12 months before cancer diagnosis and 12 months following cancer diagnosis (henceforth referred as during-treatment). The post treatment phase contained 24 months following diagnosis, with 12 months baseline and 12 months follow-up. As we sought to include patients enrolled in Medicare Part D (starting availability in 2007) at least 24 months before diagnosis, we selected incident primary MCC diagnosed between 2009 and 2017. The first year of each phase was defined as the baseline period and the second year as the follow-up period. Healthcare expenditures were calculated during the follow-up periods for all cohort. Demographics, census tract, AHRF and CHRF characteristics were collected at baseline. Treatment and presence of chronic conditions were identified at baseline and follow-up periods. We used a 12-months baseline and follow-up periods for several reasons: 1) to reasonably capture comorbid conditions; 2) define the baseline period near the measurement of outcomes (expenditures), and 3) to minimize attrition due to longer baseline and follow-up periods, and 4) to measure follow-up period expenditures to support policy decisions, which typically require annual financial estimates.

Study Cohort: Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

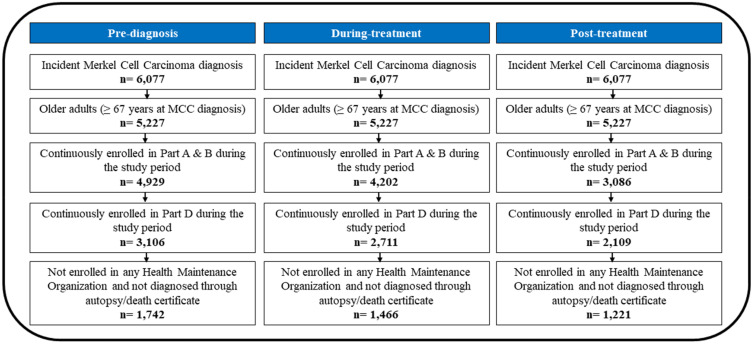

Medicare beneficiaries aged 67 years or older at the index date, who had a confirmed diagnosis of MCC prior to this date, were subject to the following inclusion criteria: 1) a primary incident diagnosis of MCC; 2) uninterrupted enrollment in Medicare Parts A, B, and D throughout the study period; and 3) no enrollment in health maintenance organizations (HMOs) at any point during the study period. Patients with prior cancer diagnoses, as well as those diagnosed solely through death certificates or autopsy findings, were excluded from the study. The cohort attrition flow diagram for all three study phases is shown in Figure 2. For pre-diagnosis, during-treatment and post-treatment, the final study cohort consisted, respectively, of 1,742, 1,466, and 1,221 incident primary MCC cases.

Figure 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria, Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims files, 2009–2017.

Measures

Dependent or Target Variables

Total Healthcare Expenditures (Medicare Payments)

Total annual healthcare expenditures comprised Medicare payments for inpatient, carrier, outpatient, durable medical equipment, prescription drugs, and home health agency services. All expenditures were estimated at follow-up for each cohort. Medical services prices published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics were used to adjust all expenditures to 2019 constant dollars.26 Total healthcare expenditures were log-transformed using a natural logarithm to reduce the spread of the distribution.

Out-of-Pocket Expenditures (Patient Responsibility)

Total annual OOP included payments made by the patients or their families. These included patient deductible, coinsurance, and copay amounts as per the methodology recommended by ResDAC.27 Patient payments for inpatient, carrier, outpatient, prescription drug, and durable medical equipment services were aggregated. All OOP expenditures were converted to real dollars using the medical services index and expressed in 2019 USD. OOP were log-transformed using a natural logarithm to reduce the spread of the distribution.

Independent Variable or Predictors

To understand the factors associated with total healthcare and total OOP expenditures among incident primary elderly MCC patients, we used the determinants of health model.28

This framework explores various determinants of healthcare expenses, including biological (sex and age), socioeconomic (race, marital status, census-level education, income, and poverty), and access-related factors (insurance coverage, pain specialist visits, fragmentation of care). The fragmentation of care index (FCI) was derived using a modified version of the Bice-Boxerman continuity of care index.29,30 Care fragmentation represents the concentration of visits per patient among health care providers based on visit number, proportion of encounters to each provider, and total number of visits. Multiple encounters with a single provider would result in a score of zero; however, multiple encounters among several health care providers would result in a score approaching 1. Care fragmentation was measured at baseline.

The choice of medical conditions was informed by the Goodman Framework. Medical conditions of interest included asthma, arthritis, congestive heart failure (CHF), coronary artery disease (CAD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cardiac dysrhythmias (CARR), diabetes, heart failure, hypertension, HIV, hepatitis, high cholesterol, stroke, thyroid disease, anxiety, and depression. All conditions were identified at baseline and follow-up using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM codes from Medicare inpatient and outpatient claims. We mapped these conditions to fewer, relevant categories using the Clinical Classification Software (CCS mapped to ICD-9-CM) and the Clinical Classification Software Refined (CCSR mapped to ICD-10-CM) categorization schemes. A single variable accounting for each chronic condition’s diagnosis made either at baseline or follow-up was created.

Medical treatment factors encompassed the entirety of medications administered at both baseline and follow-up, identified through their generic names as recorded in Medicare Part D claims. We introduced a variable called “generic drug count”, which quantified the number of drugs taken at baseline and identified using the CanMED system. Cancer treatments, specifically SRx, RTx, CTx, HTx, and ITx, were assessed across all study phases except the pre-diagnosis phase. This decision was grounded in the expectation that cancer-specific treatments would have no significant impact on healthcare expenditures before the diagnosis date, as cancer management typically commences afterward. In instances where cancer care was used as an independent variable in the models at baseline and follow-up, it was included as distinct, individual variables.

Other medical treatment factors involved the cancer stage, which was identified through data obtained from the SEER registry. We structured this variable into three levels, classifying MCC cases as localized, regional, or distant. Behavioral factors were characterized by alcohol and tobacco use and recognized through the assignment of ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM codes.

External environmental factors considered the presence of screening and oncology centers at the county level, as well as the categorization of the SEER region into Northeast, South, Midwest, and West.

Analysis

Descriptive analysis

We conducted a descriptive analysis of average annual total and OOP expenditures for each of the chronic conditions and other important covariates such as age, sex, race, cancer stage, dual Medicaid coverage, diagnosis year, region, urban/rural residence. Excess expenditures were derived by using the cost of illness approach. Under this approach, incremental expenditures associated with chronic conditions can be computed by subtracting average healthcare expenditures of those with a chronic condition of interest, and those without the chronic condition of interest. For practical reasons, only the incremental expenditures associated with chronic conditions are reported.

Machine Learning: XGBoost

Statistical or traditional methods often necessitate hands-on selection of variables and a prespecified plan of analysis to avoid certain type of biases (type I or II errors) and maintain rigor in inferential statements. Confronted with vast amounts of data, the statistical approach can be time-consuming and error laden. Machine learning (ML) techniques, with a vast array of feature reduction technique bypass this requirement and offer an efficient way to handle high-dimensional data.31

In this study, we used Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), which is a decision-tree ensemble ML algorithm. One-hot encoding was used to transform categorical variables into a numerical format suitable for ML.32 The dataset was split into training and test sets, each, respectively, consisting of 70% and 30% of the dataset. Based on the conceptual framework, 170 variables were initially selected. We used recursive feature elimination (RFE) to select for the 50 top ranked features for inclusion in our models. RFE is a systematic feature reduction technique, which is used to reduce the number of features in a model by selecting those of higher rank and relevance.33,34 The XGBoost model was trained with 10-fold cross validation using the best hyperparameters identified using grid search. Performance metrics for the regression models included the root mean square error (RMSE) and R2, as they, respectively, assess the error and goodness of fit of the model. The interpretability of our regression model outputs was facilitated by the use of Shapley additive explanations (SHAP).35 SHAP values have a global and local interpretation. Globally, they explain positive or negative contribution of each feature to the dependent variable, whereas locally, they advise on the by-patient contribution of features. SHAP dependency plots and interaction plots (Xgbfir package) were created. Feature importance and partial dependence plots were generated using TreeSHAP in Python 3.11.4.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. Across all time periods, the majority of elderly MCC patients were male (57,4%, 58.1%, 56.8%), lived in metro areas (92.5%), with no dual Medicaid coverage (83.1%, 83.8%, 84.3%) and with local MCC (59.2%, 63.7%, 65.8%). In the during-treatment period, 96.6% of elderly MCC patients received SRx, 63.6 received RTx, 31.7% CTx, 10.2% had ITx, and 13.5% received HTx. In the post-treatment period, 64.0% of elderly MCC patients had SRx, 21.5% had RTx, 31.9% received CTx, 12.5% had ITx, and 14.3% had HTx.

Table 1.

Selected Sample Characteristics Among Fee-for-Service Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries (Age ≥67 Years at Index Date) with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims Files, 2009

| Pre-diagnosis | During-treatment | Post-treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| ALL | 1742 | 100.0 | 1466 | 100.0 | 1221 | 100.0 |

| Biological determinants | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1000 | 57.4 | 852 | 58.1 | 693 | 56.8 |

| Female | 742 | 42.6 | 614 | 41.9 | 528 | 43.2 |

| Age | ||||||

| 66–69 | 118 | 6.8 | 129 | 8.8 | 118 | 9.7 |

| 70–74 | 323 | 18.5 | 305 | 20.8 | 265 | 21.7 |

| 75–79 | 336 | 19.3 | 309 | 21.1 | 265 | 21.7 |

| 80–84 | 338 | 19.4 | 300 | 20.5 | 260 | 21.3 |

| 85+ | 627 | 36.0 | 423 | 28.9 | 313 | 25.6 |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 1616 | 92.8 | 1361 | 92.8 | 1137 | 93.1 |

| Non-White | 126 | 7.2 | 105 | 7.2 | 84 | 6.9 |

| Social determinants of health | ||||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 843 | 48.4 | 734 | 50.1 | 629 | 51.5 |

| Not Married | 899 | 51.6 | 732 | 49.9 | 592 | 48.5 |

| Dual Medicaid coverage | ||||||

| Yes | 294 | 16.9 | 238 | 16.2 | 192 | 15.7 |

| No | 1448 | 83.1 | 1228 | 83.8 | 1029 | 84.3 |

| Rural/Urban Residence | ||||||

| Metro | 1611 | 92.5 | 1363 | 93.0 | 1143 | 93.6 |

| Non-Metro | 131 | 7.5 | 103 | 7.0 | 78 | 6.4 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 730 | 41.9 | 619 | 42.2 | 541 | 44.3 |

| South | 287 | 16.5 | 237 | 16.2 | 184 | 15.1 |

| Midwest | 143 | 8.2 | 128 | 8.7 | 100 | 8.2 |

| West | 582 | 33.4 | 482 | 32.9 | 396 | 32.4 |

| Clinical variables | ||||||

| Cancer Stage | ||||||

| Local | 1031 | 59.2 | 934 | 63.7 | 803 | 65.8 |

| Regional | 409 | 23.5 | 356 | 24.3 | 279 | 22.9 |

| Distant | 148 | 8.5 | 69 | 4.7 | 41 | 3.4 |

| Unknown | 154 | 8.8 | 107 | 7.3 | 98 | 8.0 |

| Polypharmacy | ||||||

| Yes | 975 | 56.0 | 812 | 55.4 | 705 | 57.7 |

| No | 767 | 44.0 | 654 | 44.6 | 516 | 42.3 |

| Chronic conditions | ||||||

| Asthma | ||||||

| Yes | 1527 | 87.7 | 1269 | 86.6 | 1057 | 86.6 |

| No | 215 | 12.3 | 197 | 13.4 | 164 | 13.4 |

| Arthritis | ||||||

| Yes | 535 | 30.7 | 384 | 26.2 | 311 | 25.5 |

| No | 1207 | 69.3 | 1082 | 73.8 | 910 | 74.5 |

| Congestive heart failure | ||||||

| Yes | 1244 | 71.4 | 1022 | 69.7 | 834 | 68.3 |

| No | 498 | 28.6 | 444 | 30.3 | 387 | 31.7 |

| Coronary artery disease | ||||||

| Yes | 702 | 40.3 | 557 | 38.0 | 461 | 37.8 |

| No | 1040 | 59.7 | 909 | 62.0 | 760 | 62.2 |

| Cardiac dysrhythmias | ||||||

| Yes | 897 | 51.5 | 713 | 48.6 | 587 | 48.1 |

| No | 845 | 48.5 | 753 | 51.4 | 634 | 51.9 |

| Chronic kidney disease | ||||||

| Yes | 1280 | 73.5 | 1057 | 72.1 | 880 | 72.1 |

| No | 462 | 26.5 | 409 | 27.9 | 341 | 27.9 |

| COPD | ||||||

| Yes | 1170 | 67.2 | 928 | 63.3 | 766 | 62.7 |

| No | 572 | 32.8 | 538 | 36.7 | 455 | 37.3 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| Yes | 857 | 49.2 | 723 | 49.3 | 622 | 50.9 |

| No | 885 | 50.8 | 743 | 50.7 | 599 | 49.1 |

| Heart diseases | ||||||

| Yes | 1117 | 64.1 | 844 | 57.6 | 667 | 54.6 |

| No | 625 | 35.9 | 622 | 42.4 | 554 | 45.4 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| Yes | 308 | 17.7 | 414 | 28.2 | 468 | 38.3 |

| No | 1434 | 82.3 | 1052 | 71.8 | 753 | 61.7 |

| HIV | ||||||

| Yes | 216 | 12.4 | 352 | 24.0 | 437 | 35.8 |

| No | 1526 | 87.6 | 1114 | 76.0 | 784 | 64.2 |

| Hepatitis | ||||||

| Yes | 785 | 45.1 | 641 | 43.7 | 603 | 49.4 |

| No | 957 | 54.9 | 825 | 56.3 | 618 | 50.6 |

| High cholesterol | ||||||

| Yes | 296 | 17.0 | 213 | 14.5 | 179 | 14.7 |

| No | 1446 | 83.0 | 1253 | 85.5 | 1042 | 85.3 |

| Osteoporosis | ||||||

| Yes | 1393 | 80.0 | 1187 | 81.0 | 974 | 79.8 |

| No | 349 | 20.0 | 279 | 19.0 | 247 | 20.2 |

| Stroke | ||||||

| Yes | 1431 | 82.1 | 1200 | 81.9 | 1010 | 82.7 |

| No | 311 | 17.9 | 266 | 18.1 | 211 | 17.3 |

| Thyroid | ||||||

| Yes | 1121 | 64.4 | 876 | 59.8 | 699 | 57.2 |

| No | 621 | 35.6 | 590 | 40.2 | 522 | 42.8 |

| Depression | ||||||

| Yes | 1386 | 79.6 | 1123 | 76.6 | 930 | 76.2 |

| No | 356 | 20.4 | 343 | 23.4 | 291 | 23.8 |

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Yes | 1453 | 83.4 | 1125 | 76.7 | 912 | 74.7 |

| No | 289 | 16.6 | 341 | 23.3 | 309 | 25.3 |

| Lifestyle determinants | ||||||

| Alcohol abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 27 | 1.5 | 24 | 1.6 | 11 | 0.9 |

| No | 1715 | 98.5 | 1442 | 98.4 | 1210 | 99.1 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Yes | 33 | 1.9 | 46 | 3.1 | 13 | 1.1 |

| No | 1709 | 98.1 | 1420 | 96.9 | 1208 | 98.9 |

| Health care use | ||||||

| Pain specialist visits | ||||||

| Yes | 467 | 26.8 | 401 | 27.4 | 955 | 78.2 |

| No | 1275 | 73.2 | 1065 | 72.6 | 266 | 21.8 |

| Psychologist visits | ||||||

| Yes | 133 | 7.6 | 107 | 7.3 | 97 | 7.9 |

| No | 1609 | 92.4 | 1359 | 92.7 | 1124 | 92.1 |

| Emergency room use | ||||||

| Yes | 653 | 37.5 | 548 | 37.4 | 536 | 43.9 |

| No | 1089 | 62.5 | 918 | 62.6 | 685 | 56.1 |

| Continuous Variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| Age at diagnosis | 80.94 | 7.78 | 79.67 | 7.49 | 78.54 | 7.14 |

| Care fragmentation | 0.74 | 0.16 | 0.75 | 0.15 | 0.81 | 0.12 |

| Total expenditures | 25,792.20 | 42,402.70 | 49,844.58 | 45,486.10 | 28,297.71 | 35,880.28 |

| Out-of-pocket expenditures | 5,201.88 | 6,802.72 | 10,450.31 | 6,895.69 | 6,050.14 | 6,427.89 |

The prevalence of chronic conditions was based on baseline and follow-up at each time period. The most predominant chronic conditions included asthma (87.0%), stroke (82.2%), osteoporosis (80.3%), chronic kidney disease (72.6%), and congestive heart failure (69.8%). Anxiety (78.3%), depression (77.5%) prevalence were particularly high. The mean age was 80.94 ± 7.78 pre-diagnosis, 79.67 ± 7.49 during-treatment, and 78.54 ± 7.14 post-treatment. The mean fragmentation of care index was 0.74 ± 0.16 pre-diagnosis, 0.75 ± 0.15 during-treatment, and 0.81 ± 0.12 post-treatment.

Average Healthcare Expenditures

The average total healthcare expenditures were highest during-treatment ($49,844.58 ± $45,486.10) followed by pre-diagnosis ($25,792.20 ± $42,402.70), and post-treatment $28,297.71 ± $35,880.28. The same trend was observed for the mean average OOP expenditures, with the mean OOP during-treatment ($10,450.31±$6,895.69) at least double those of the previous chronological cohorts ($5,201.88 ± $6,802.72) and still higher than the mean OOP post-treatment ($6,050.14 ± $6,427.89). Unadjusted average annual total and OOP expenditures by other important covariates are summarized in Tables S1 and S2.

In terms of chronic conditions (Table 2), the highest average total expenditures were incurred by elderly MCC patients with depression ($66,739.9), CHF ($66,730.0), anxiety ($64,142.5), CKD ($63,796.4), and heart diseases ($61,124.1) during-treatment. With respect to total OOP, CHF ($12,551.2), stroke ($12,378.9), CKD ($12,266.1), depression ($12,229), anxiety ($11,995.9) during-treatment. Pre-diagnosis and post-treatment, asthma became one of the top 5 chronic conditions with the largest increase in total and OOP expenditures. Visual representation in terms of kernel density is provided in Figure S1.

Table 2.

Selected Average Total Healthcare and OOP Expenditures Across Chronic Conditions Among Fee-for-Service Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries (Age ≥67 Years at Index Date) with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims Files, 2009–2017

| Pre-diagnosis | During-treatment | Post-treatment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenditures | |||

| Depression | |||

| Yes | $ 43,013.9 | $ 66,739.9 | $ 46,494.6 |

| No (ref) | $ 21,368.7 | $ 44,684.2 | $ 28,144.8 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Yes | $ 38,027.2 | $ 64,142.5 | $ 43,778.4 |

| No (ref) | $ 23,358.7 | $ 45,510.7 | $ 28,702.9 |

| Congestive heart failure | |||

| Yes | $ 43,648.4 | $ 66,730.0 | $ 43,636.1 |

| No (ref) | $ 18,644.0 | $ 42,508.8 | $ 27,359.0 |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

| Yes | $ 42,342.9 | $ 63,796.4 | $ 47,334.3 |

| No (ref) | $ 19,818.5 | $ 44,446.0 | $ 26,776.8 |

| Heart diseases | |||

| Yes | $ 39,300.8 | $ 61,124.1 | $ 42,528.5 |

| No (ref) | $ 18,233.7 | $ 41,531.9 | $ 24,203.6 |

| OOP expenditures | |||

| Congestive heart failure | |||

| Yes | $ 7,846.5 | $ 12,551.2 | $ 8,328.3 |

| No (ref) | $ 4,143.2 | $ 9,537.6 | $ 5,886.5 |

| Chronic kidney disease | |||

| Yes | $ 7,829.5 | $ 12,266.1 | $ 8,760.8 |

| No (ref) | $ 4,253.5 | $ 9,747.7 | $ 5,846.5 |

| Stroke | |||

| Yes | $ 7,142.3 | $ 12,378.9 | $ 8,417.3 |

| No (ref) | $ 4,780.2 | $ 10,022.8 | $ 6,293.4 |

| Depression | |||

| Yes | $ 7,810.4 | $ 12,229.0 | $ 8,780.4 |

| No (ref) | $ 4,531.9 | $ 9,907.0 | $ 5,997.1 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Yes | $ 6,978.3 | $ 11,995.9 | $ 8,486.0 |

Abbreviations: OOP, Out of Pocket Expenditures; SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare.

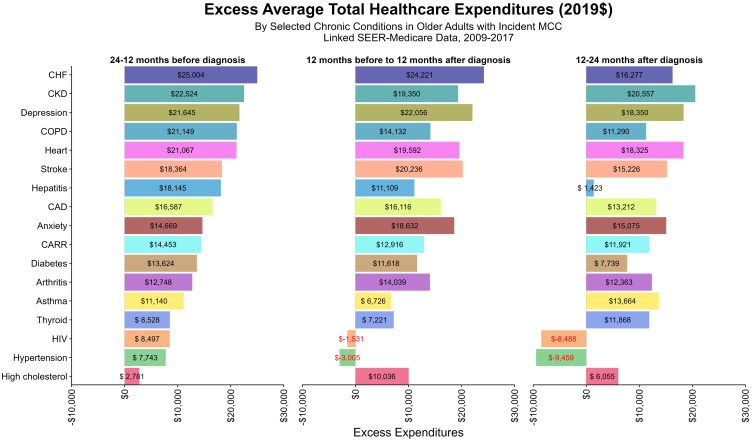

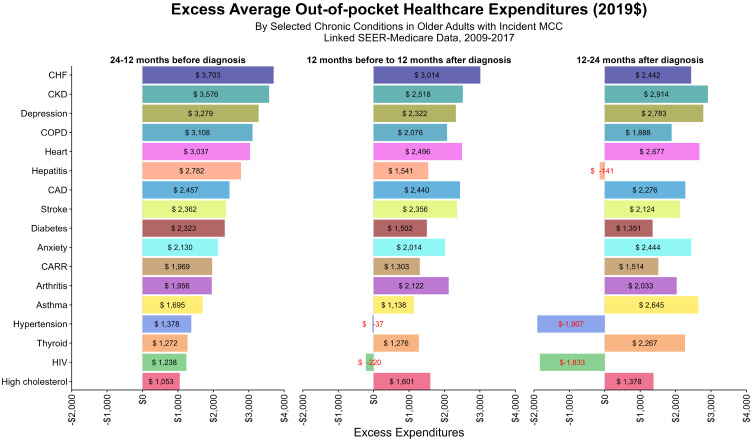

We also examined the excess total expenditures and OOP for elderly MCC patients who also had chronic conditions (Figures 3 and 4). In general, the highest excess mean expenditures were found pre-diagnosis, with the exception of beneficiaries with arthritis ($12,748.11 vs $14,039.32), high cholesterol ($2,780.7 vs $10,036.4), stroke ($18,364.3 vs $20,236.3), depression ($21,645.2 vs $22,055.7), and anxiety ($14,668.6 vs.14,668.6 vs $18,631.8), which had mean higher excess expenditures during-treatment. The same trend was observed for total OOP. The largest depressions in total and OOP expenditures were observed for hepatitis, HIV, and hypertension. For HIV and hypertension in particular, those without these respective conditions had higher (negative excess as shown in Figures 3 and 4) total and OOP expenditures than those diagnosed with them.

Figure 3.

Excess Average Total Healthcare Expenditures.

Figure 4.

Excess Average OOP Healthcare Expenditures.

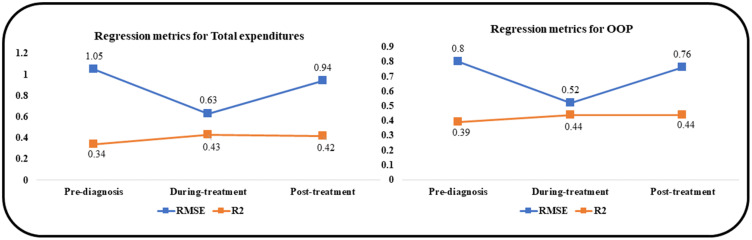

Model Performance

The performance metrics used to evaluate XGBOOST regression models included the RMSE and the R2. The RMSE measures the accuracy of a model by quantifying how close the predictions are to the actual values on average. A RMSE value of zero indicates that the predicted values perfectly match the actual values. The R2 represents the goodness of fit of a regression model. R2 values of 1 close to 1 indicate how perfectly or very well the model fits the data. Figure 5 shows our performance metrics. The RMSE ranged from 0.63 (during-treatment) to 1.05 (pre-diagnosis) for total healthcare expenditures and from 0.52 (during-treatment) to 0.8 (pre-diagnosis) for OOP. The R2 ranged from 0.34 (pre-diagnosis)– 0.43 (during-treatment) for total healthcare expenditures and from 0.39 (pre-diagnosis) to 0.44 (during-treatment and post-treatment) for OOP.

Figure 5.

Performance Metrics of XGBoost Models, Among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries (≥67 years old) with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims, 2009–2017.

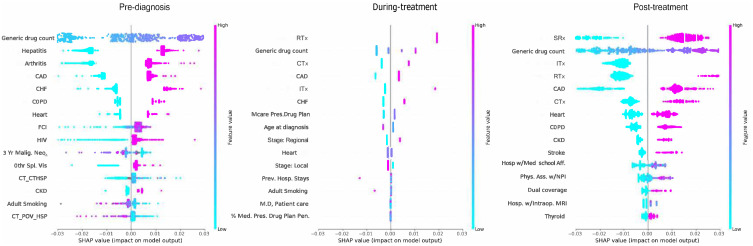

ML Model Interpretation: Global Feature Importance and Association of Chronic Conditions with Healthcare Expenditures - SHAP Summary Plots

Common top 10 predictors (Figure 6) of total healthcare expenditures pre-diagnosis, during-treatment, and post-treatment, respectively, featured: CHF (4th, 2nd, 8th), heart diseases (8th, 6th, 7th), and CKD (9th, 10th, 10th). Chronic conditions amounted, respectively, to 8, 4, and 5 out of 10 of the top 10 features pre-diagnosis, during-treatment, and post-treatment.

Figure 6.

Summary Plot with top 15 Leading Predictors of Total Expenditures, Among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries (≥67 years old) with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims files, 2009–2017. The x-axis represents the marginal contribution of a feature to the change in log odds of type of treatment. Based on older adults (age ≥67 years diagnosis data) with MCC diagnosed between 2009–2017, who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B & D during baseline period and follow up period; SEER- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Cancer Registry; FCI: Fragmentation of care; 3Yr Malig. Neo: 3 year number of malignant neoplasms; CT_CTHSP: census tract % of Hispanics; Mcar. Ben.Hosp. Read: % of Medicare beneficiaries Readmissions Rate; Prev. Hosp Stays: Preventable Hospital Stays; %Mcare. Adv. Plan: % with Medicare Penetration Advantage Plan; Phys. Assistants w/NPI: Number of physicians assistants with National Provider Identification; Psychiatry, Patient Care: Number of hospitals providing psychiatric patient care; Rad. Oncology: Number of hospitals with radiation oncology centers; Stage- Regional: Regional MCC.

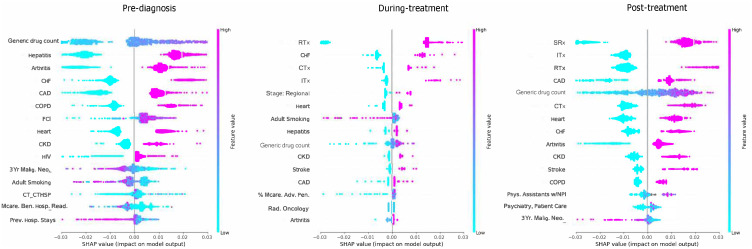

Only one chronic condition common to all three cohorts featured in the top 10 predictors of total OOP (Figure 7) namely, heart diseases (7th, 10th, 7th respectively pre-diagnosis, during-treatment, and post-treatment). Top individual predictors did not vary pre-diagnosis between the total expenditures and OOP; however, notable changes were seen during-treatment with the exclusion of CKD for OOP. Post-treatment, stroke and COPD replaced CHF and arthritis. All chronic conditions had positive associations with total healthcare and OOP expenditures.

Figure 7.

Shapley Additive exPlanations - Summary Plot with top 15 Leading Predictors of OOP, Among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries (≥67 years old)) with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims files, 2009–2017. The x-axis represents the marginal contribution of a feature to the change in log odds of type of treatment. Based on older adults (age ≥67 years diagnosis data) with MCC diagnosed between 2009–2017, who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Parts A, B & D during baseline period and follow up period; SEER- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Cancer Registry FCI: Fragmentation of care; 3Yr Malig. Neo: 3 year number of malignant neoplasms; CT_CTHSP: census tract % of residents who are Hispanics; CT_POV_HSP: census tract % of residents living below poverty for Hispanics; Othr.Spl. Vis: Other specialist visists; Mcar. Ben.Hosp. Read: % of Medicare beneficiaries Readmissions Rate; Prev. Hosp Stays: Preventable Hospital Stays; Mcare. Presc.Drug Plan: Number with Medicare prescription drug plan; M.D, Patient Care: Number of Medical doctors for Patient Care.; %Med.Pres. Drug Plan Pen: % of with Medicare prescription drug plan penetration; Hosp w/Med School Aff: Number of hospitals with medical school affiliates; Phys. Ass. w/NPI: Number of physicians assistants with National Provider Identification; Hosp. w/Intraop. MRI: Number of hospitals with intraoperative MRI.

ML Model Interpretation: Partial Dependence Plots of Chronic Conditions

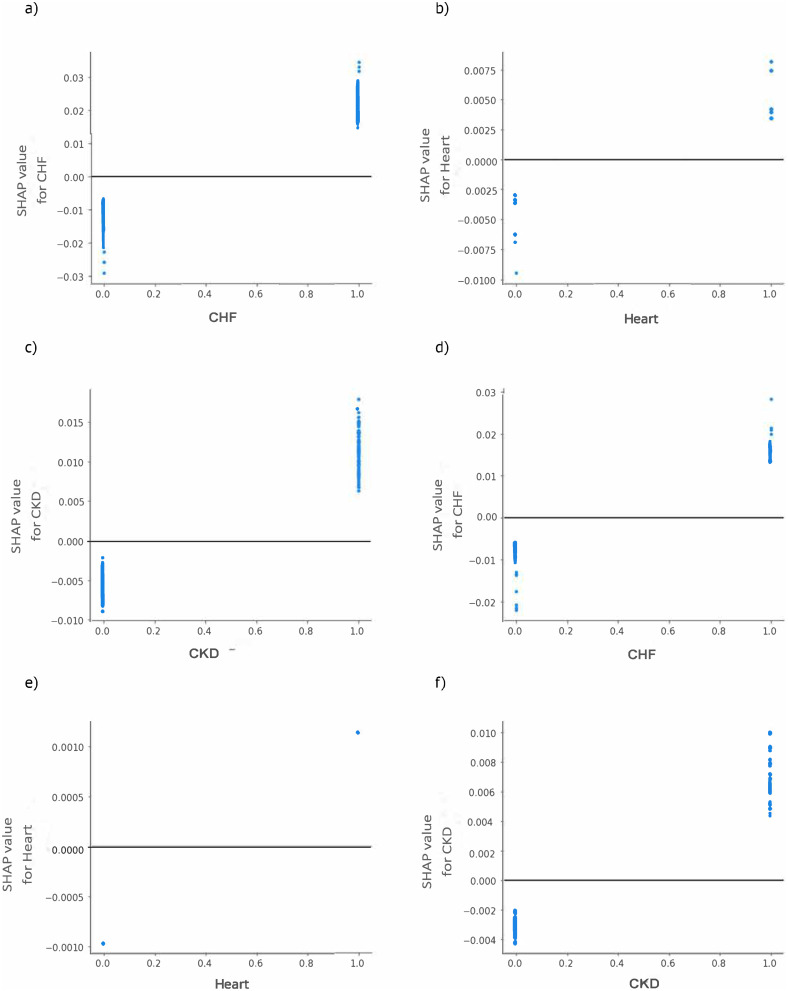

Our partial dependence plots in Figure 8 show that the direction of association between CHF, heart and CKD and expenditures was homogenous; that is, the presence of any of these conditions was associated with high total healthcare and OOP expenditures.

Figure 8.

Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) dependence plots, Among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries (≥67 years old) with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims files, 2009–2018. Each point on the plot corresponds to a prediction in a patient (a) and (d) SHAP dependence plot of log-odds SHAP values of CHF on total expenditures and OOP respectively; (respectively; (b) and (e) The main effect of heart diseases on total expenditures and OOP; (c) and (f) The main effect of CKD on total expenditures and OOP. Based on older adults (age ≥67 years at index date) with incident MCC diagnosed between 2009–2017, who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A, B and D during the baseline and follow up periods. SEER- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Cancer Registry.

ML Model Interpretation: Feature Interactions with Chronic Conditions

Table 3 shows the top five interactive associations across all cohort, which included generic drug count and care fragmentation, cancer treatment and chronic conditions. Pre-diagnosis, care fragmentation interacted with arthritis. During-treatment, generic drug count interacted with CAD, whereas the % of Medicare advantage penetration interacted with hepatitis. Post-treatment, ITx and generic drug count interacted distinctly with CAD. Interactions between chronic conditions and other features included a different type of conditions than those featured in the list of top 10 predictors.

Table 3.

Key Feature Interactions Among Fee-for-Service Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries (Age ≥67 Years at Index Date) with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims Files, 2009 to 2017

| Interaction | Gain | F1 Score | Weighted F1 | Gain Rank | F1 Score Rank | Weighted F1 Score Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenditures | ||||||

| Pre-diagnosis | ||||||

| CT_CTHSP | Generic drug count | 10.97 | 8 | 0.78 | 1 | 1 | 17 |

| FCI | Generic drug count | 10.41 | 7 | 1.37 | 2 | 2 | 10 |

| FCI | FCI | 8.22 | 7 | 1.55 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Arthritis | FCI | 7.12 | 6 | 1.46 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| FCI | Primary Care Provider rate | 6.78 | 5 | 0.07 | 5 | 7 | 55 |

| During-treatment | ||||||

| RTx | Adult Smoking | 2.27 | 7 | 2.21 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| % Medicare Adv. Pen. | RTx | 1.03 | 3 | 0.83 | 2 | 2 | 8 |

| CTx | Generic drug count | 0.71 | 3 | 2.07 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| CAD | Generic drug count | 0.63 | 2 | 0.03 | 4 | 4 | 20 |

| % Mcare Adv. Pen. | Hepatitis | 0.6 | 2 | 0.73 | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Post-treatment | ||||||

| CAD | ITx | 5.12 | 9 | 7.1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CAD | Generic drug count | 3.48 | 8 | 2.36 | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| RTx | SRx | 2.46 | 5 | 3.29 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| ITx | SRx | 2.08 | 4 | 2.51 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| SRx | Generic drug count | 1.87 | 4 | 1.15 | 5 | 5 | 14 |

| OOP expenditures | ||||||

| Pre-diagnosis | ||||||

| CT_CTHSP | HIV | 9.62 | 2 | 0.01 | 1 | 11 | 60 |

| CT_CTHSP | Generic drug count | 8.17 | 3 | 0.09 | 2 | 3 | 35 |

| FCI | Generic drug count | 5.76 | 7 | 3.06 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Generic drug count | Preventable Hospital Stays | 3.46 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Arthritis | Primary Care Provider rate | 3.39 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 24 | 73 |

| During-treatment | ||||||

| RTx | Adult Smoking | 1.77 | 7 | 2.16 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| % Medicare Adv. Pen. | RTx | 0.63 | 3 | 0.79 | 2 | 5 | 8 |

| CTx | Generic drug count | 0.41 | 3 | 2.04 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| CAD | Generic drug count | 0.38 | 2 | 0.01 | 4 | 8 | 7 |

| % Medicare Adv. Pen. | Hepatitis | 0.45 | 2 | 0.71 | 5 | 4 | 10 |

| Post-treatment | ||||||

| CAD | ITx | 6.91 | 10 | 8.6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| SRx | Generic drug count | 4.8 | 10 | 3.43 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| CAD | Generic drug count | 4.63 | 10 | 3.73 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| RTx | Generic drug count | 4.17 | 8 | 5.3 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| CAD | SRx | 3.46 | 8 | 2.8 | 5 | 5 | 8 |

Note: CT_CTHSP: census tract percentage of Hispanics; Adult Smoking: Percentage of adult smokers per the AHRF data; FCI: fragmentation care index; % Mcare Adv. Pen: Percentage of Medicare Advantage Penetration; SRx: surgery; CTx: chemotherapy; RTx: Radiotherapy; CAD: coronary artery disease; OOP: Out of Pocket Expenditures; SEER: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare.

ML Model Interpretation: Interpretation of Other Features

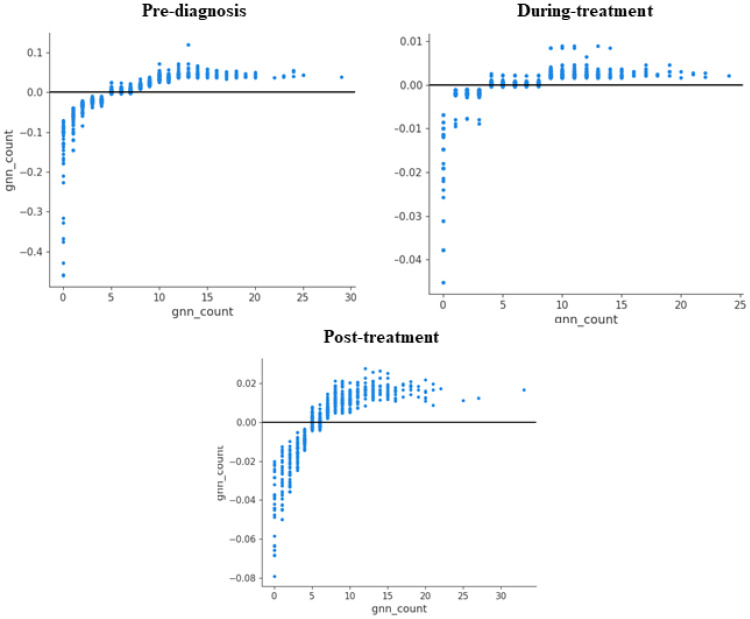

Generic drug count was the 1st, 9th, and 5th top predictor (Figure 6) of total healthcare expenditures pre-diagnosis, during-treatment, and post-treatment. For OOP, it was, respectively, the 1st, 2nd, and 2nd top predictor across the same cohorts. Figure 9 shows the partial dependence plots for generic drug count across all time periods for total expenditures. They show that at a certain threshold between 5 and 10 drugs, the relationship with expenditures is heterogeneous, but apart from this range, it was positive.

Figure 9.

Shapley additive explanations (SHAP) dependence plots for Generic Drug Count, Among Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries (≥67 years old)) with Merkel Cell Carcinoma, Linked SEER Cancer Registry and Medicare Claims files, 2009–2018. Each point on the plot corresponds to a prediction in a patient (pre-diagnosis) top left; (during treatment) top right and (post-diagnosis) bottom; Y value is SHAP value for generic drug count. Based on older adults (age ≥67 years at index date) with incident MCC diagnosed between 2009–2017, who were continuously enrolled in Medicare Part A, B and D during the baseline and follow up periods. SEER- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Cancer Registry.

RTx and CTx were among the top 10 common predictors in the during-treatment (1st, 3rd), and post-treatment (3rd, 6th) cohorts for total expenditures. SRx was the top predictor of total expenditures in the during-treatment cohort. Common OOP top 10 treatment predictors between the during-treatment and post-treatment included CTx (3rd, 6th) and ITx (5th, 3rd). Regional stage and adult smoking were the 6th and 8th top predictors of total healthcare expenditures during-treatment cohort. Care fragmentation was the 7th predictor of total expenditures pre-diagnosis and did not feature across any other cohort. Medicare Penetration Drug Plan and age at diagnosis were, respectively, the 7th and 8th top predictors of OOP during-treatment. Most top 10 predictors had a positive relationship with total healthcare and OOP expenditures, with three exceptions. Generic drug count, Medicare Penetration Drug Plan and age at diagnosis had a mixed relationship with expenditures (Figures 6 and 7).

Sensitivity Analysis

We followed the same beneficiaries (N = 1,029) across the three different phases. Leading predictors are presented in Figures S2 and S3. Generally, the leading predictors were consistent with our primary analysis. However, differences were noted in terms of ranking, and additional predictors. For example, CTx ranked lower (15th vs 3rd) during treatment phase. Local stage of MCC is ranked 12th leading predictor during treatment.

Discussion

This study is the first to examine the total healthcare and OOP expenditures in elderly MCC patients at three different time periods in order to determine the differential across patient-level characteristics and to elicit the predictors of these costs. Elderly MCC patients were significantly burdened by chronic conditions,36 with the added strain of cancer, it became crucial to observe the changes in predictors of healthcare expenditures before, after and during the cancer journey. Expenditures were the highest in the during the first year after diagnosis, and the lowest 12 months before diagnosis. A previous study showed that direct healthcare costs among advanced MCC patients quadrupled in the first four months after diagnosis and rose to a 12-fold increase when comparing baseline and follow-up at 12 months, respectively.37 Herein, the median total 12-month direct healthcare costs were US$48,006, which is within the range of the average total expenditures obtained in this study $49,844.58. Excluding the last year of life (end-of-life cancer death phase), studies have shown that among older cancer adults with Medicare coverage, the initial care during the first year after diagnosis is often the costliest.5,38 A study conducted among older adults, with cancer using SEER-Medicare database found average annualized costs of $41,800, which were within the range of the average total healthcare expenditures of $49,844.58 obtained in our study.5 Using the SEER-Medicare linkage data and the Medical Panel Expenditure Survey data, a study found that across several cancer sites, OOP expenditures were the highest in the first 12 months of diagnosis for medical services and prescription drugs ($2,200 and $243).39 The same pattern was observed in melanoma, where the initial phase of treatment (12 months after index) was higher than the continuing phase of treatment among elderly cancer patients (65 years or above).40

Excess average total and OOP costs showed that auto- acquired immune disorders (hepatitis and HIV) and metabolic disorders (hypertension) had the largest decrease in expenditures across time. Future studies need to disentangle the survivor bias in these two conditions.

Approximately 62% of cancer survivors (65 and older) living in the United States are 65 and older, and they are expected to grow to 74%. Around 62% of elderly patients (65 and above) have multiple chronic conditions (three or more).41 Our findings show that physical chronic conditions such as CHF, CKD, stroke, and heart diseases led to the highest increase in expenditures. This matches previous reports in the literature.42 A previous study showed that the largest increase in annual expenditures was associated with heart disease and stroke.42 In another study of adults with cancer in the US, stroke, CAD, CARR, and diabetes were the chronic conditions with the highest expenditures.43 Among Medicaid beneficiaries with cancer, the largest excess total cost of care for physical chronic conditions over a period of 6 months were reported for respiratory diseases ($5,040 to $8,155), diabetes ($7483 to $7714).44 The mental chronic conditions identified in this study (depression and anxiety) incurred a higher increase in costs over time compared to the physical chronic conditions, and this is consonant with previous findings in the literature.44,45 A systematic review on the impact of chronic conditions on cancer survivors uncovered that mental health disorders excess costs were also the highest when compared to physical chronic conditions ($11,009 vs $8,0004).44,45 They uncovered that mental health conditions had the highest hospital, long-term care and ambulatory care costs compared to other conditions.44,45 In our study, there was no major change over time (and cohorts) among the conditions with the highest excess expenditures, except for the inclusion of asthma. However, a previous study has listed respiratory diseases as one of the causes of high excess costs in adults with cancer.44

It appears thus that the effect of cancer on chronic conditions or vice-versa depends on the type of condition. In this study, most of the identified conditions were pre-existing before MCC. Evidence suggests that patients with comorbidity may be less likely to receive curative treatment and find it difficult to comply with treatment regimens or to tolerate their side effects.46,47 This could prolong their time in the health systems and lead to higher expenditures compared to those without comorbidities. Thus, although most of the conditions identified herein had been pre-existing prior to cancer diagnosis, their presence is as relevant to cancer management regardless of when the diagnosis occurred.

The predictors of total annual expenditures and annual OOP expenditures differed vastly across the three cohorts. Pre-diagnosis cohort, the top 10 predictors featured mostly different chronic conditions, generic drug count, care fragmentation, and the 3-year prevalence malignant neoplasms. The most obvious difference between the latter cohort and the following two is the rise to prominence of cancer care in the form of SRx (post-treatment), RTx (during-treatment, post-treatment), CTx (during-treatment, post-treatment), and ITx (during-treatment, post-treatment). Although no study has evaluated before the predictors of costs in MCC, previous studies have identified certain type of costs that significantly increase the initial cancer expenditures in the first 12 months after diagnosis.48 While examining the trends in costs in colorectal, lung and breast cancer, a study conducted using the SEER-Medicare linkage data uncovered that the rising prices of treatment and the subsequent strain it places on the Medicare program stems in large part from the increased use of CTx use and RTx during the first year after diagnosis.48 A previous study on advanced MCC patients also showed that CTx drove the cost during the first year after diagnosis.37 In another study featuring MCC patients, in which the Veterans Health Administration database was used, the mean costs per patients in the ITx and CTx cohorts were driven at 49.5% and 13.5%, respectively, by MCC-therapy related services.49 In a study that used the Premier Healthcare Database to assess costs in a metastatic MCC population (which received as treatment ITx or CTx only), the authors found that the costs, albeit higher for those who had ITx, were primarily driven by pharmacy medication costs.50 This could explain why MCC treatments (SRx, RTx, CTx, and ITx) were among the top 10 predictors during-treatment and post-treatment for all expenditure type. The same phenomenon is common in melanoma, where increases in costs over a five-year period after cancer presentation are driven by the use of adjuvant therapy, targeted therapy or CTx.51

These findings highlight the theory of competing demands that cancer patients are faced with. Cancer comorbidities not only influence treatment but can also affect economic burden among elderly MCC patients. An acute cancer diagnosis with an underlying chronic condition creates unforeseen treatment complications and competing healthcare demands in terms of negotiating silos across medical management teams.23 Therefore, the impact of chronic conditions on economic burden can vary by the phases of cancer care. In this case (our study), we observe that in the during-treatment phase and post-treatment phase, cancer care became dominant, and this may lead to the neglect of non-cancer chronic condition care.

The model performance was moderate given the range of R2 and RMSE values obtained. Boosting the sample size could help obtain better results. However, this shows the ability to use ML algorithms in small samples of rare cancers such as MCC. XGBoost applicability demands further replication, however, it proves its use as an explanatory modelling tool when the features are large (N = 50) and the sample size is small.

This study has many strengths. We are the first to compare the total healthcare expenditures and total OOP across three phases of cancer care as well as the predictors of said costs and investigate their association with the presence of chronic conditions. We use a large registry dataset linked with claims data for this purpose, namely SEER-Medicare data, which contains near-complete census information on all cancers among elderly cancer patients (≥65 years). We used a retrospective cohort design and employed ML algorithm to identify the leading predictors of healthcare expenditures. Chronic conditions were mapped with fidelity using a high standard categorization scheme (CCS and CCS-R).

This study has several limitations. Healthcare expenditures were limited to the direct medical costs. Indirect and tangible could not be assessed given the nature of the data source. This implies that our findings are probably an underestimation of the actual expenditures. We use the term “out-of-pocket expenditures” interchangeably with beneficiary responsibility. It is possible that some portion of the beneficiary responsibility may be covered by secondary insurance, and this may lead to an overestimation of out-of-pocket expenditures. The potential for measurement errors when identifying chronic conditions in 2015 during which there was a transition from the ICD-9-CM to the ICD-10-CM system in the US existed. Further, our findings may not be generalizable to the entire MCC population as we only included elderly at least 65 years older. Moreover, claims-based measures of depression, drugs, alcohol, and tobacco use have been known to have low sensitivity, as noted on the SEER-Medicare website.52 We may not have captured the recent impact of the use of targeted therapies in MCC as our linkage data extended only to 2019.

Conclusion

This study showed that chronic conditions significantly drive healthcare expenditures among elderly MCC patients before cancer diagnosis and continue to do so at varying degrees during- and post-treatment periods. However, cancer treatments ranked higher than chronic conditions in influencing economic burden during-treatment and post-treatment phases. The interactions between comorbidities and cancer care in MCC require more in-depth investigation into those management patterns that increase the financial burden on Medicare programs and patients. This would require, among other strategies, making older patients with comorbidities a priority in clinical trials and practice settings.

Acknowledgment

The collection of cancer incidence data used in this study was supported by the California Department of Public Health pursuant to California Health and Safety Code Section 103885; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Program of Cancer Registries, under cooperative agreement 1NU58DP007156; the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program under contract HHSN261201800032I awarded to the University of California, San Francisco, contract HHSN261201800015I awarded to the University of Southern California, and contract HHSN261201800009I awarded to the Public Health Institute. The ideas and opinions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the State of California, Department of Public Health, the National Cancer Institute, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or their Contractors and Subcontractors.

The authors would like to thank Dr Murtuza Bharmal for his advice, involvement, and assistance towards the performance of the study.

The abstract of this paper was presented at the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research conference 2024 as a poster with interim findings. The poster’s abstract was published in ‘ISPOR Abstracts 2024’ in the journal ‘Value in Health’.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the EMD Serono Research & Development Institute, Inc.

Ethics Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West Virginia University (#2203549606).

Disclosure

Dr. Murtuza Bharmal was an employee of EMD Serono at the time the study was conducted. Dr Khalid Kamal reports grants from Cerevel Therapeutics, Pfizer/Cytel, and honorarium from Pharmacy Times and Continuing Education, outside the submitted work. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Pozzi V, Molinelli E, Campagna R, et al. Knockdown of nicotinamide N-methyltransferase suppresses proliferation, migration, and chemoresistance of Merkel cell carcinoma cells in vitro. Hum Cell. 2024;37(3):729–738. doi: 10.1007/s13577-024-01047-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mazziotta C, Badiale G, Cervellera CF, et al. All-trans retinoic acid exhibits anti-proliferative and differentiating activity in Merkel cell carcinoma cells via retinoid pathway modulation. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38(7):1419–1431. doi: 10.1111/jdv.19933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhan S, Nguyen M, Hollsten J. Immune checkpoint inhibition therapy as first-line treatment for localized eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma in a nonsurgical candidate. Can J Ophthalmol. 2024;59(2):e183–e184. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjo.2023.10.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callahan R, Darzi A. Five policy levers to meet the value challenge in cancer care. Health Aff. 2015;34(9):1563–1568. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mariotto AB, Enewold L, Zhao J, Zeruto CA, Robin Yabroff K. Medical care costs associated with cancer survivorship in the United States. Canc Epide Biomarkers Prev. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-1534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunn AH, Sorenson C, Greenup RA. Navigating the high costs of cancer care: opportunities for patient engagement. Future Oncol. 2021;17(28):3729–3742. doi: 10.2217/fon-2021-0341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yabroff KR, Lund J, Kepka D, Mariotto A. Economic burden of cancer in the United States: estimates, projections, and future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh N, McClure EM, Akaike T, et al. The evolving treatment landscape of Merkel cell carcinoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2023;24(9):1231–1258. doi: 10.1007/s11864-023-01118-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y, Yu T, Mackey RH, et al. Clinical outcomes, costs, and healthcare resource utilization in patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma treated with immune checkpoint inhibitors vs chemotherapy. Clinic Outcomes Res. 213–226. DOI: 10.2147/CEOR.S290768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuehn BM. Cancer Care Creates Substantial Costs for US Patients. JAMA. 2021;326(22):2251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iragorri N, de Oliveira C, Fitzgerald N, Essue B. The out-of-pocket cost burden of cancer care—a systematic literature review. Current Oncol. 2021;28(2):1216–1248. doi: 10.3390/curroncol28020117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network. Costs Canc. 2020;2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGarvey N, Gitlin M, Fadli E, Chung KC. Increased healthcare costs by later stage cancer diagnosis. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1155. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-08457-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen S, Cao Z, Prettner K, et al. Estimates and Projections of the Global Economic Cost of 29 Cancers in 204 Countries and Territories From 2020 to 2050. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9(4):465–472. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2022.7826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pisu M, Henrikson NB, Banegas MP, Yabroff KR. Costs of cancer along the care continuum: what we can expect based on recent literature. Cancer. 2018;124(21):4181–4191. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ren K, Yin X, Zhou B. Effects of surgery on survival of patients aged 75 years or older with Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer Med. doi: 10.1002/cam4.4437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bahar F, DeCaprio JA. Why do we distinguish between virus-positive and virus-negative Merkel cell carcinoma? Br J Dermatol. 2024;190(6):785–786. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljae086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kearney M, Thokagevistk K, Boutmy E, Bharmal M. Treatment patterns, comorbidities, healthcare resource use, and associated costs by line of chemotherapy and level of comorbidity in patients with newly-diagnosed Merkel cell carcinoma in the United States. J Med Econ. 2018;21(12):1159–1171. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2018.1517089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McEvoy AM, Lachance K, Hippe DS, et al. Recurrence and Mortality Risk of Merkel Cell Carcinoma by Cancer Stage and Time From Diagnosis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(4):382–389. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.6096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.European Social Insurance Platform. Cancer Comorbidities and Complications: proposals for a. New Appr Health Insurers. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 21.George M, Smith A, Sabesan S, Ranmuthugala G. Physical Comorbidities and Their Relationship with Cancer Treatment and ItsOutcomes in Older Adult Populations: systematic Review. JMIR Cancer. 2021;7(4):e26425. doi: 10.2196/26425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gurney J, Sarfati D, Stanley J. The impact of patient comorbidity on cancer stage at diagnosis. Br J Cancer. 2015;113(9):1375–1380. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duthie K, Strohschein FJ, Loiselle CG. Living with cancer and other chronic conditions: patients’ perceptions of their healthcare experience. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2017;27(1):43–48. doi: 10.5737/236880762714348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsevat J, Moriates C. Value-Based Health Care Meets Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(5):329–332. doi: 10.7326/M18-0342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balasubramanian BA, Higashi RT, Rodriguez SA, Sadeghi N, Santini NO, Lee SC. Thematic Analysis of Challenges of Care Coordination for Underinsured and Uninsured Cancer Survivors With Chronic Conditions. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(8):e2119080–e2119080. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.19080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Home CPI US Bureau of Labor Statistics; 2019. Avaialbe from: https://www.bls.gov/cpi/Accessdate:09.20.23. Accessed October 25, 2024.

- 27.Definitions of “Cost” in Medicare Utilization Files | resDAC. Avaialbe from: https://resdac.org/articles/identifying-medicare-managed-care-beneficiaries-master-beneficiary-summary-or-denominatorAccessdate:09.20.23. Accessed October 25, 2024.

- 28.Andersen RM. National Health Surveys and the Behavioral Model of Health Services Use. Med Care. 2008;46(7):647–653. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817a835d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bice TW, Boxerman SB. A quantitative measure of continuity of care. Med Care. 1977;15(4):347–349. doi: 10.1097/00005650-197704000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu CW, Einstadter D, Cebul RD. Care fragmentation and emergency department use among complex patients with diabetes. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(6):413–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hunter DJ, Holmes C, Drazen JM, Kohane IS, Leong T-Y. Where Medical Statistics Meets Artificial Intelligence. N Engl J Med. 2023;389(13):1211–1219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2212850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Workflow of a Machine Learning Project | By Ayush Pant | Towards Data Science. Towards Data Science. Avaialbe from: https://towardsdatascience.com/workflow-of-a-machine-learning-project-ec1dba419b94. Accessed October 25, 2024.

- 33.Shi X, Wong YD, Li MZF, Palanisamy C, Chai C. A feature learning approach based on XGBoost for driving assessment and risk prediction. Accid Anal Prev. 2019;129:170–179. doi: 10.1016/J.AAP.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ogunleye A, Wang QG. XGBoost Model for Chronic Kidney Disease Diagnosis. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2020;17(6):2131–2140. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2019.2911071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lundberg SM, Allen PG, Lee SI. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. Adv Neural Inf Process Syst. doi: 10.5555/3295222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bluethmann SM, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH. Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: prevalence Trajectories and Comorbidity Burden among Older Cancer Survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2016;25(7):1029–1036. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steuten L, Garmo V, Phatak H, Sullivan SD, Nghiem P, Ramsey SD. Treatment Patterns, Overall Survival, and Total Healthcare Costs of Advanced Merkel Cell Carcinoma in the USA. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2019;17(5):733–740. doi: 10.1007/s40258-019-00492-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown ML, Riley GF, Schussler N, Etzioni R. Estimating Health Care Costs Related to Cancer Treatment from SEER-Medicare Data. Med Care. 2002;40(8):IV104–IV117. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yabroff KR, Mariotto A, Tangka F, et al. Annual Report to the Nation on the Status of Cancer, Part 2: patient Economic Burden Associated With Cancer Care. JNCI J National Cancer Inst. 2021;113(12):1670–1682. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djab192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seidler AM, Pennie ML, Veledar E, Culler SD, Chen SC. Economic Burden of Melanoma in the Elderly Population: population-Based Analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER)–Medicare Data. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(3):249–256. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang C, Deng L, Karr MA, et al. Chronic comorbid conditions among adult cancer survivors in the United States: results from the National Health Interview Survey, 2002-2018. Cancer. 2022;128(4):828–838. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33981 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guy GP, Yabroff KR, Ekwueme DU, Rim SH, Li R, Richardson LC. Economic Burden of Chronic Conditions Among Survivors of Cancer in the United States. J clin oncol. 2017;35(18):2053–2061. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.9716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Davis-Ajami ML, Lu ZK, Wu J. Multiple chronic conditions and associated health care expenses in US adults with cancer: a 2010–2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):981. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4827-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rim SH, Guy GPJ, Yabroff KR, McGraw KA, Ekwueme DU. The impact of chronic conditions on the economic burden of cancer survivorship: a systematic review. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;16(5):579–589. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2016.1239533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Subramanian S, Tangka FKL, Sabatino SA, et al. Impact of chronic conditions on the cost of cancer care for Medicaid beneficiaries. Medicare Medic Res Rev. 2012;2(4):E1–E21. doi: 10.5600/mmrr.002.04.a07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fowler H, Belot A, Ellis L, et al. Comorbidity prevalence among cancer patients: a population-based cohort study of four cancers. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):2. doi: 10.1186/s12885-019-6472-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Søgaard M, Thomsen RW, Bossen KS, Sørensen HT, Nørgaard M. The impact of comorbidity on cancer survival: a review. Clin Epidemiol. 2013;5(sup1):3–29. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S47150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warren JL, Yabroff KR, Meekins A, Topor M, Lamont EB, Brown ML. Evaluation of trends in the cost of initial cancer treatment. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(12):888–897. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chandra S, Zheng Y, Pandya S, et al. Real-world outcomes among US Merkel cell carcinoma patients initiating immune checkpoint inhibitors or chemotherapy. Future Oncol. 2020;16(31):2521–2536. doi: 10.2217/fon-2020-0453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zheng Y, Yu T, Mackey RH, et al. Clinical Outcomes, Costs, and Healthcare Resource Utilization in Patients with Metastatic Merkel Cell Carcinoma Treated with Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors vs Chemotherapy. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2021;13:213–226. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S290768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alexandrescu DT. Melanoma costs: a dynamic model comparing estimated overall costs of various clinical stages. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15(11):1. doi: 10.5070/D353F8Q915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.National Cancer Institute. SEER-Medicare Linked Data Resource; 2023. Avaialbe from: https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/seermedicare/. Accessed April 12, 2023