Abstract

Background

The use of fidaxomicin is recommended as first-line therapy for all patients with Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI). However, real-world studies have shown conflicting evidence of superiority.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective single-center study of patients diagnosed with CDI between 2011 and 2021. A primary composite outcome of clinical failure, 30-day relapse, or CDI-related death was used. A multivariable cause-specific Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate fidaxomicin compared to vancomycin in preventing the composite outcome. A separate model was fit on a subset of patients with C. difficile ribotypes adjusting for ribotype.

Results

There were 598 patients included, of whom 84 received fidaxomicin. The primary outcome occurred in 8 (9.5%) in the fidaxomicin group compared to 111 (21.6%) in the vancomycin group. The adjusted multivariable model showed fidaxomicin was associated with 63% reduction in the risk of the composite outcome compared to vancomycin (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], .17–.80). In the 337 patients with ribotype data after adjusting for ribotype 027, the results showing superiority of fidaxomicin were maintained (HR = 0.19; 95% CI, .05–.77).

Conclusions

In the treatment of CDI, we showed that real-world use of fidaxomicin is associated with lower risk of a composite end point of treatment failure.

Keywords: Clostridioides difficile, fidaxomicin, ribotype 027, CDI, oral vancomycin

This study evaluated the treatment effectiveness of fidaxomicin compared to vancomycin in a single-center real-world study. Our results showed that fidaxomicin was associated with a reduced risk of Clostridioides difficile infection recurrence even after adjusting for ribotype 027.

Clostridioides difficile is a leading cause of nosocomial infectious diarrhea worldwide and is associated with frequent recurrences [1, 2]. Infection with different C. difficile strains can contribute to recurrences. Between 2000 and 2010, the increasing rates of C. difficile infection (CDI), recurrence and treatment failure with vancomycin and metronidazole was attributed partially to the emergence of a hypervirulent strain of C. difficile known as NAP1/B1/027 [3–6].

Metronidazole and vancomycin have been the mainstay of treatment until the licensure of fidaxomicin. Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) showed that fidaxomicin was associated with higher rates of sustained clinical cure and reduced risk of recurrence [7–10]. However, real-world experience with fidaxomicin has shown mixed results. A meta-analysis of real-world studies demonstrated no significant difference in treatment outcomes between fidaxomicin and vancomycin, but the results were limited by substantial between-study variability [11].

Therefore, we examined the real-world experience of the clinical effectiveness of fidaxomicin compared to vancomycin in a large cohort of patients with CDI treated at an academic medical center. In addition, to better understand the role of ribotypes in treatment response, we reviewed a subset of patient outcomes who had ribotype data. Our previously published study comparing fidaxomicin to vancomycin in immunocompromised hosts represented a subset of the patients analyzed from the entire cohort [12].

METHODS

Study Setting

All adult patients diagnosed with CDI between 1 March 2011 and 31 December 2021 at Tufts Medical Center, a 415-bed tertiary academic hospital in Boston, MA, were identified. The study excluded patients younger than 18 years, those with toxic megacolon at time of diagnosis, those who did not receive any treatment for CDI, treated with metronidazole only or fecal microbiota transplant, and those who received treatment for longer than 30 days. Patients who were treated for longer than 30 days were excluded to minimize immortal time bias, because all received only vancomycin and none received fidaxomicin. The Tufts Medical Center Institutional Review Board approved this study (SUDY00001199). Informed consent was waived.

We collected C. difficile isolates initially as part of surveillance for fidaxomicin susceptibility required by the Food and Drug Administration between 2011 and 2016 and then as part of our internal surveillance program [13, 14]. The Special Studies Laboratory at Tufts Medical Center obtained and cultured stools from patients who had CDI [15]. The isolates of C. difficile were ribotyped by polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based fragment analysis at the Walk Laboratory as previously described [15].

Definitions

CDI was defined as a diarrheal illness or ileus with a positive stool test. A test was considered positive if both glutamate dehydrogenase antigen and a toxin assay were positive, or the nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) was positive [16]. In our institution, testing conducted during the study period used a 2-step algorithm starting with toxin/antigen assay followed by NAAT for indeterminate results. In August 2020, NAAT for indeterminate results required approval by the antimicrobial stewardship team or an infectious disease physician [17]. Indeterminate tests that were not reflexed to NAAT were not included in this study. CDI test types were divided in the analysis to those with positive toxin test or positive NAAT.

Clinical failure was defined as any conversion or addition of antimicrobials more than 72 hours after initiation of therapy by the treating physician for perceived treatment failure. Relapse at 30 days was defined as recurrence of diarrhea and/or the need to restart CDI treatment within 30 days of stopping therapy for the index CDI case as determined by the treating physician with or without a positive test. Relapse at 90 days was defined as recurrence of diarrhea and/or the need to restart CDI treatment between 30 and 90 days of stopping therapy for the index CDI case as determined by the treating physician with or without a positive test, excluding relapses that occurred before 30 days. Total relapse was defined as recurrence of diarrhea and/or the need to restart CDI treatment within 90 days of stopping therapy for the index CDI case as determined by the treating physician with or without a positive test.

Death related to CDI was defined as any death that was attributed to CDI within 30 days of initial diagnosis. The cause of death was determined by physician (M. A.) review of death certificates. and discharge summaries. Death from other cause, a competing risk to the primary outcome, was defined as any death that was not associated with CDI within 30 days of CDI diagnosis. This included cardiac, pulmonary, or cancer-related deaths.

Severe CDI was defined based on Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) criteria, that is leukocytosis with white cell count (WBC) of ≥ 15 000 cells/mL or serum creatinine (SCr) > 1.5 mg/dL [16]. Health care-associated CDI was defined as infection diagnosed after 48 hours following admission to the hospital or prior health care exposure within 30 days prior to diagnosis. Immunocompromised status was defined as having at least 1 of the following at the time of CDI diagnosis: (1) solid organ or hematologic stem cell transplant, (2) undergoing active chemotherapy, or (3) being on immunomodulator agents.

For the definition of CDI treatment, patients were classified as having been treated with fidaxomicin or vancomycin if they received at least 72 hours of the agent. Hospital-wide guidelines for CDI treatment during the study recommended the use of fidaxomicin for patients with increased risk of recurrence including those with immunocompromising conditions, history of CDI, chronic kidney disease, and patients older than 65 years, while vancomycin was recommended for everyone else.

Data Collection

Patient demographic and clinical data, including age, sex, race, ethnicity, comorbid conditions, history of prior CDI, the use of gastric acid suppression, toxin test positivity, location prior to and at the time of CDI diagnosis, laboratory data and intensive care unit (ICU) admission, were collected manually from the hospital medical records during the study period. We reviewed inpatient and outpatient clinical notes and discharge summaries to confirm a clinical syndrome consistent with CDI. We also confirmed treatment durations from the medication/pharmacy record. Antecedent antibiotic exposure was limited to the 30 days prior to CDI diagnosis as recorded in the medical/pharmacy records. The Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was used to describe patients based on their comorbidities [18]. Probiotic use was not collected. The authors were not blinded to the treatment when collecting death outcome data. However, the data were collected in 2 rounds. In the first round, 1 of the authors (M.A.) and a research assistant extracted the clinical data. Then in a second round, causes of death were collected from death certificates and discharge summaries. Although it was not blinded, we identified patients who had the diagnosis of toxic megacolon, fulminant colitis, sepsis, septic shock, or CDI as a cause of death as CDI-related death. The study data were collected using REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) hosted by Tufts Medical Center [19].

Statistical Analysis

The primary study outcome was a composite outcome of clinical failure, relapse within 30 days following completion of initial CDI treatment, or having died due to CDI. The composite outcome was prespecified. It was chosen as a clinical representation of CDI treatment failure and to increase power to enable us to perform multivariable adjustments for confounding variables. Secondary outcomes included the components of the composite outcome separately in addition to relapse at 90 days and total relapse following completion of initial CDI treatment. The date of last contact with the medical team following CDI diagnosis was documented. A secondary subgroup analysis including patients with ribotype data was conducted to evaluate the relationship between ribotypes and the composite clinical outcome.

Patients’ demographic and clinical characteristics were presented as frequencies and medians with interquartile ranges according to treatment group and the composite outcome; we tested for between group differences using χ2 and Mann-Whiney tests.

For the primary composite outcome, a cause-specific Cox proportional hazards model was used to account for competing risk of death from other causes. Patients without an event were censored at 30 days of treatment completion or patients were censored earlier based on time of last known follow-up. First, possible confounding variables were tested by a univariate screen and included in the model if the P value was less than .1. Second, the multivariable model was built using backwards selection of variables, which included age, sex, CCI, history of CDI, gastric acid suppression, location prior to diagnosis, dialysis, CDI test type, and ICU stay. Immunocompromised status was added to the model and tested as an effect modifier of the relationship between treatment and the composite outcome. We conducted a subgroup analysis examining the impact of CDI test type on the relationship between treatment and the composite outcome. Additionally, in a secondary subgroup analysis, the detection of ribotype 027 was added to the model as a potential confounder. We also performed a sensitivity analysis in which patients from whom we had follow-up isolates able to be ribotyped. Those in whom the ribotype was different from the original case ribotype were classified as a new infection and thus did not meet our case definition of relapse.

The secondary outcomes were examined individually using cause-specific Cox proportional hazards models. The proportional hazards assumptions were checked using the graphical assessment of Schoenfeld residuals [20].

Patients with missing values were included in all analyses through the use of multiple imputation under the missing at random assumption [20–22]. Ten data sets were imputed, and pooled estimates are presented. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis evaluating the first dose of CDI therapy administered on the composite outcome to assess any intention-to-treat effect.

All statistical analyses were completed using either R Studio software version 4.1.2 (R Core Team) or SPSS version 28. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise indicated.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

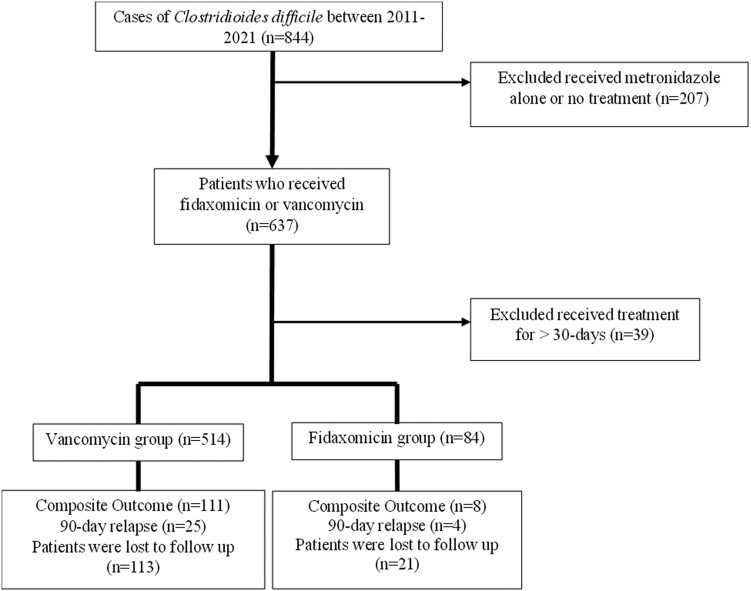

There were 844 patients diagnosed with CDI during the study period; 598 patients met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The majority of CDI cases (90.8%) were primary episodes. Patients treated with fidaxomicin were more likely to be older (68.2 years vs 65.0 years, P = .043), male (63.1% vs 49.0%, P = .018), and have had a diagnosis of prior CDI (7.1% vs 1.8%, P < .05) compared to the vancomycin group (Table 1). There were 168 (28.1%) patients treated longer than 14 days, 25 (29.8%) in the fidaxomicin group and 143 (27.8%) in the vancomycin group. Severe CDI occurred in 62% of cases based on WBC criteria, the rest was based on creatinine criteria in the setting of chronic kidney disease (14%) or acute on chronic kidney disease (24%), with no statistically significant differences between groups. There were 134 patients censored at the time of last known follow-up, 21 (25%) in the fidaxomicin group and 113 (22.0%) in the vancomycin group with no difference in the proportion of censorship between groups. There were no statistically significant differences in missing values between the treatment groups with respect to markers of severity including WBC count, ICU stay, location of testing, or toxin positivity.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study patient selection.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients by Treatmenta

| Characteristics | Fidaxomicin (n = 84) | Vancomycin (n = 514) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age, y, median (Q1, Q3)b | 68.2 (57.4, 76.7) | 65 (54.2, 73.1) | .04 |

| Male, n (%) | 53 (63.1) | 252 (49.0) | .02 |

| White, n (%) | 68 (81.0) | 382 (74.3) | .23 |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 4 (4.8) | 25 (4.9) | .96 |

| Immunocompromised, n (%) | 38 (45.2) | 189 (36.8) | .15 |

| CCI, median (Q1, Q3)b | 5 (4, 7) | 5 (2.5, 7) | .08 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 13 (15.5) | 43 (8.4) | .04 |

| Gastric acid suppression, n (%) | 55 (65.5) | 279 (54.3) | .06 |

| ICU stay, n (%) | 21 (25.0) | 144 (28.0) | .59 |

| Loss to follow-up, n (%) | 21 (25.0) | 113 (22.0) | .54 |

| Time to loss of follow-up, d, median (Q1, Q3)b,c | 8 (4, 20.5) | 11 (3, 38) | .39 |

| CDI characteristics | |||

| CDI in past 6 mo, n (%) | 6 (7.1) | 9 (1.8) | .009 |

| Any history of CDI, n (%) | 18 (21.4) | 47 (9.1) | .001 |

| Location prior to diagnosis, n (%) | .08 | ||

| Health care associated | 69 (82.1) | 373 (72.6) | |

| Community acquired | 15 (17.9) | 141 (27.4) | |

| CDI test type, n (%) | .16 | ||

| Toxin and antigen assay | 39 (46.4) | 280 (54.5) | |

| NAAT, toxin gene | 45 (53.6) | 234 (45.5) | |

| Severe CDI, n (%) | 42 (50.0) | 236 (45.9) | .54 |

| Antecedent antibiotic use, n (%) | 63 (75.0) | 379 (73.7) | .87 |

| No. of antecedent antibiotics, median (Q1, Q3)b | 1 (0, 3) | 2 (0, 2) | .17 |

| Antibiotics during treatment, n (%) | 40 (47.6) | 273 (53.1) | .34 |

| Ribotype 027 d, n (%) | 8 (20.0) | 46 (15.5) | .45 |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; ICU, intensive care unit; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3.

aχ2 was used for all testing unless otherwise specified.

bMann-Whitney U test.

cOnly for patients lost to follow-up.

dTotal number 337.

Clinical Outcomes

A total of 119 (19.9%) patients developed the composite outcome. The most common outcome was relapse at 30 days (72 events), followed by deaths attributed to CDI (32 events), and clinical failure (15 events). There were 29 cases of relapse at 90 days.

There were 8 (9.5%) patients in the fidaxomicin group who developed the composite outcome compared to 111 (21.6%) patients in the vancomycin group. For the secondary outcomes, in the fidaxomicin group compared to vancomycin, 3 (3.6%) patients developed clinical failure compared to 12 (2.3%). There were 2 (2.4%) and 4 (4.8%) who relapsed at 30 and 90 days, respectively, in the fidaxomicin group compared to 70 (13.6%) and 25 (4.9%) in the vancomycin group. A total of 32 CDI-related deaths occurred, 3 (3.6%) in the fidaxomicin group versus 29 (5.6%) in the vancomycin group.

The distribution of the primary and secondary outcomes is shown in Table 2. All patients with 30-day relapse were treated. There were 51 (70.8%) patients who had positive toxin test, 10 (13.9%) who had positive NAAT, and 11 (15.3%) who were treated without testing.

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes by Treatment Group

| Outcome | Fidaxomicin (n = 84) | Vancomycin (n = 514) | Total (n = 598) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Composite outcomea | 8 (9.5) | 111 (21.6) | 119 (19.9) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Clinical failure | 3 (3.6) | 12 (2.3) | 15 (2.5) |

| 30-day relapseb | 2 (2.4) | 70 (13.6) | 72 (13.1) |

| 90-day relapsec | 4 (4.8) | 25 (4.9) | 29 (6.1) |

| Total relapse | 6 (7.1) | 95 (18.5) | 101 (18.3) |

| Death related to CDI | 3 (3.6) | 29 (5.6) | 32 (5.5) |

| Other causes of death | 7 (8.3) | 15 (2.9) | 22 (3.7) |

Data are No. (%).

Abbreviation: CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection.

aComposite outcome: failure to achieve clinical cure, relapse at 30 days, and death related to CDI.

bNo. after exclusion of patients who had clinical failure or died (n = 551).

cNo. after exclusion of patients who had clinical failure, died, or had 30-day relapse (n = 479).

Patients who developed the composite outcome were more likely to have stayed in the ICU and had a positive toxin test compared to those who did not (Table 3).

Table 3.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Patients by the Composite Outcome a

| Characteristic | Composite Outcome (n = 119) | No Composite Outcome (n = 479) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | |||

| Age, y, median (Q1, Q3)b | 64.6 (55.6, 75.2) | 65.5 (54.3, 74.5) | .47 |

| Male, n (%) | 69 (58.0) | 236 (49.3) | .09 |

| White, n (%) | 91 (76.5) | 359 (74.9) | .72 |

| Hispanic, n (%) | 7 (5.9) | 23 (4.8) | .76 |

| Immunocompromised, n (%) | 42 (35.3) | 185 (38.6) | .52 |

| CCI, median (Q1, Q3)b | 5 (3, 7) | 5 (2, 7) | .84 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 13 (10.9) | 43 (9.0) | .52 |

| Gastric acid suppression, n (%) | 66 (55.5) | 268 (55.9) | .94 |

| ICU stay, n (%) | 43 (36.1) | 123 (25.7) | .03 |

| CDI characteristics | |||

| CDI in past 6 mo, n (%) | 5 (4.2) | 10 (2.1) | .17 |

| Any prior CDI, n (%) | 13 (11.3) | 52 (11.0) | .94 |

| Location prior to diagnosis, n (%) | .28 | ||

| Health care associated | 83 (69.7) | 359 (74.9) | |

| Community acquired | 36 (30.3) | 120 (25.1) | |

| CDI test type, n (%) | <.001 | ||

| Toxin and antigen assay | 78 (65.5) | 241 (50.3) | |

| NAAT, toxin gene | 41 (34.5) | 238 (49.7) | |

| Severe CDI, n (%) | 57 (47.9) | 221 (46.1) | .79 |

| Antecedent antibiotic use, n (%) | 89 (74.8) | 352 (73.5) | .77 |

| No. of antecedent antibiotics, median (Q1, Q3)b | 1 (1, 2) | 1 (0, 2) | .61 |

| Antibiotics during treatment, n (%) | 57 (47.9) | 256 (53.4) | .31 |

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; ICU, intensive care unit; NAAT, nucleic acid amplification test; Q1, quartile 1; Q3, quartile 3.

aχ2 was used for all testing unless otherwise specified.

bMann-Whitney U test.

Multivariable Model

In the multivariable adjusted model, fidaxomicin was associated with a 63% reduction in the development of the composite outcome compared to vancomycin (hazard ratio [HR] = 0.37; 95% confidence interval [CI], .17–.80). Similarly, fidaxomicin use was significantly associated with reducing the hazards of 30-day and total relapse (Table 4). Being immunocompromised, evaluated as an effect modifier, was not shown to be statistically significant (P = .49).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and Adjusted Cause-Specific Proportional Hazard Model for Fidaxomicin Compared to Vancomycin

| Outcomes | Unadjusted Model, Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

Adjusted Model,a Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Composite outcomeb | ||

| Fidaxomicin | 0.43 (.21–.88) | 0.37 (.17–.80) |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Clinical failure | 1.54 (.44–5.47) | 2.05 (.53–8.03) |

| 30-day relapse | 0.17 (.04–.69) | 0.16 (.04–.66) |

| 90-day relapse | 0.96 (.33–2.79) | 0.70 (.34–2.09) |

| Total relapse | 0.37 (.16–.85) | 0.33 (.14–.75) |

| CDI-related death | 0.64 (.19–2.09) | 0.42 (.10–1.77) |

Other causes of death adjusted hazard ratio 2.35 (95% CI, .91–6.02).

Abbreviations: CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

aAdjusted for sex, age, history of CDI, ICU stay, and immunocompromised status.

bComposite outcome: clinical failure, relapse at 30 days, and death related to CDI.

A subgroup analysis was conducted to evaluate the impact of CDI diagnostic test on the relationship between the clinical outcome and treatment. Fidaxomicin significantly reduced the hazard of the composite outcome in the toxin-positive group (HR = 0.20; 95% CI, .05–.80) but not in the NAAT-positive group (HR = 0.68; 95% CI, .25–1.88) after adjusting for sex, age, history of CDI, ICU stay, and immunocompromised status.

We conducted an intent-to-treat sensitivity analysis to evaluate early switches in treatment (within 72 hours of starting). There were 94 patients who received fidaxomicin as a first dose compared to 465 patients who received vancomycin. The hazards of the composite outcome remained similar to the main analysis in which fidaxomicin (HR = 0.33; 95% CI, .17–.66) remained superior to vancomycin.

Ribotype Subgroup Analysis

There were 337 (56%) patients in whom stool isolates were ribotyped, of whom 40 received fidaxomicin and 297 received vancomycin. The most common ribotype isolated was 027 (n = 54, 16.0%) followed by 014-020 (n = 47, 13.9%), and 106 (n = 46, 13.6%). Of the patients with 027 isolates, 27.8% developed the composite outcomes compared to 11.9% for ribotype 014-020 and 12.2% for ribotype 106 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Clinical outcomes by ribotype.

In a multivariable model that included only the 337 patients with isolates available for ribotyping, after controlling for ribotype 027, fidaxomicin was still associated with a reduction in the development of the composite outcome compared to vancomycin (HR = 0.19; 95% CI, .05–.77). Similarly, fidaxomicin use was significantly associated with reducing the hazards of 30- and 90-day relapse (Table 5).

Table 5.

Adjusted Cause-Specific Proportional Hazard Model for Fidaxomicin Compared to Vancomycin for Subpopulation With Ribotypes After Controlling for Ribotype 027

| Outcome | Clinical Outcome for Ribotype 027 (n = 54, %) | Clinical Outcome for Other Ribotypes (n = 283, %) | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) for Adjusted Modela |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Composite outcomeb | 15 (27.8) | 45 (15.9) | 0.19 (.05–.77) |

| Secondary outcomes | |||

| Clinical failure | 1 (1.9) | 4 (1.4) | … |

| 30-day relapse | 13 (25.0) | 22 (8.5) | 0.12 (.02–.86) |

| 90-day relapse | 3 (7.7) | 9 (3.8) | 0.56 (.10–3.13) |

| Total relapse | 16 (30.8) | 31 (11.9) | 0.24 (.07–.79) |

| CDI-related death | 1 (1.9) | 19 (6.8) | … |

Abbreviations: CDI, Clostridioides difficile infection; CI, confidence interval; ICU, intensive care unit.

aAdjusted for sex, age, history of CDI, ICU stay, immunocompromised status, and ribotype 027.

bComposite outcome: clinical failure, relapse at 30 days, and death related to CDI.

There were 23 patients, 1 in the fidaxomicin group and 22 in the vancomycin group, who had samples ribotyped during their relapse. There were 5 patients, all in the vancomycin group, who were found to have a different ribotype compared to the initial sample. A sensitivity analysis was conducted by excluding them as a relapse. The composite outcome occurred in 8 (9.5%) patients in the fidaxomicin group and 108 (21%) patients in the vancomycin group. In the multivariable analysis, fidaxomicin continued to show a reduction in the development of the composite outcome (HR = 0.20; 95% CI, .05–.83), 30-day relapse (HR = 0.12; 95% CI, .02–.93), and total relapse (HR = 0.27; 95% CI, .08–.90).

Patients infected with ribotype 027 had significantly increased risk of 30-day relapse (HR = 3.5; 95% CI, 1.62–7.64) and total relapse (HR = 3.17; 95% CI, 1.57–6.40) compared to other ribotypes in the multivariable model. Ribotypes 014-020, 106, and 053-163 were not associated with worse clinical outcomes.

DISCUSSION

The populations included in RCTs might not be representative of the general population and real-world experience in the treatment of CDI, so we conducted this study to evaluate fidaxomicin for the treatment of CDI. Our findings suggest that treatment failure as defined by our composite outcome of clinical failure, 30-day relapse, or having died due to CDI was reduced in patients who received fidaxomicin when compared to vancomycin. In addition, the hazards of 30-day relapse and total relapse were reduced following the use of fidaxomicin compared to vancomycin. Although there was a slightly higher rate of clinical failure with fidaxomicin it was not statistically significant. This might be due to the fidaxomicin group having more patients with a prior history of CDI and thus be at increased risk of failure. Furthermore, there was a bias toward failure in the fidaxomicin group in terms of underlying risk factors. Despite this bias, fidaxomicin was superior to vancomycin in our modeling. Although the rate of relapse in our study was lower than other RCTs comparing fidaxomicin to vancomycin, the relative risk of relapse in the vancomycin group was comparable to other studies [8].

There have been several real-world retrospective studies evaluating the efficacy of fidaxomicin, which have shown mixed results. Retrospective studies on CDI treatment outcomes are varied in methodology, definitions of outcomes, and populations studied, which may explain some of these differences [11]. The variability of the results could also stem from confounding by indication in which fidaxomicin might be preferentially used for patients with the highest risk of treatment failure, which could attenuate the treatment effect of fidaxomicin.

The 2 largest real-world studies conducted in the United States used the Veterans Health Administration data warehouse (VA) [23, 24]. The first study evaluated a propensity score-matched set of mostly outpatients who received fidaxomicin or vancomycin following their first or second CDI recurrence. Their multivariate analysis did not show a difference in the combined outcome of clinical failure or 90-day recurrence between the use of either agent [23]. A second VA study evaluated treatment of severe CDI using a propensity-matched cohort, and also found no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups for the composite outcome of clinical failure or recurrence within 90 days of treatment [24]. The differences in the results between our study and the VA cohorts could be due to differences in patient characteristics, given that our study predominantly included patients with primary CDI, which may have contributed to the increased efficacy of fidaxomicin.

The benefit of fidaxomicin in this study was only seen in patients with a positive toxin test but not positive NAAT. Given that the positive toxin test is more specific for CDI disease, this underscores the benefit of the use of fidaxomicin. A positive NAAT might reflect colonization, which may have diluted the potential treatment benefit of fidaxomicin. The 2 VA studies included both toxin- and NAAT-positive patients, which may have also contributed to the differences in results. In addition, the primary outcomes of our study evaluated 30-day relapse while the VA studies evaluated 90-day relapse. In contrast to the VA studies, our secondary outcome did show a reduction in the hazards of any relapse within 90 days of diagnosis.

There are several smaller real-world studies, which demonstrated a reduction in treatment failure following the use of fidaxomicin, similar to our analysis. A single-center retrospective study of 271 patients concluded that patients treated with fidaxomicin showed higher rates of sustained clinical cure compared to vancomycin, metronidazole, or their combination [25]. Another multicenter retrospective study showed fidaxomicin to be significantly associated with lower recurrence rates in the management of severe CDI (6.8% vs 17.6%) [26]. Lastly, fidaxomicin was associated with 67% reduction in the adjusted odds of 90-day readmission in another study [27].

The association between ribotype and clinical outcomes has been established for a few ribotypes. Our study is consistent with previous literature showing increased risk of recurrence with ribotype 027 compared to other ribotypes [28, 29]. There are fewer data on clinical outcomes following infection with ribotypes 014-020 and 106. Ribotype 106 has been linked to less severe disease compared to ribotype 027, but potentially showed an increased risk of recurrence [30]. On the other hand, ribotype 014-020 was previously associated with better clinical outcomes compared to ribotype 027 [31, 32]. We did not find statistically significant association between ribotype 106 or 014-020 and clinical outcomes.

Our study has several strengths. It included a large cohort of patients with strict definitions of treatment success and failure. Furthermore, statistical modeling with survival analysis was employed to control for potential confounders of the outcome and account for the competing risk of death from other causes. We also explored our data in a subset of patients using the ribotype of C. difficile strain obtained at the time of the episode and assessed the impact on clinical outcomes and response to therapy.

Our study does have several potential limitations. The retrospective nature of the design led to some patients being lost to follow-up, which was addressed by censoring patients at the time of last known follow-up using survival analysis. There were also some missing laboratory and clinical data, which we addressed with multiple imputation. There were no significant differences between those with and without missing data in terms of markers of CDI severity or differences in loss to follow-up. Although we adjusted for confounders in the multivariable model, it is possible that residual confounding remained such as confounding by indication. In addition, due to the limited number of outcomes, there may be limited power for the adjustment of confounders. Although death related to CDI was determined by an unblinded single author (M.A.), we used objective criteria to determine the cause of death.

In conclusion, our study shows that fidaxomicin reduces the risk of CDI treatment failure defined by our composite outcome of clinical failure, 30-day relapse, and CDI-related death and reduces the risk of relapse. This study supports the 2021 IDSA guideline [33].

Contributor Information

Majd Alsoubani, Division of Geographic Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; The Stuart B. Levy Center for the Integrated Management of Antimicrobial Resistance, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Jennifer K Chow, Division of Geographic Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Angie Mae Rodday, Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Laura A McDermott, Division of Geographic Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Seth T Walk, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Montana State University, Bozeman, Montana, USA.

David M Kent, Predictive Analytics and Comparative Effectiveness Center, Tufts Medical Center/Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

David R Snydman, Division of Geographic Medicine and Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Tufts Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts, USA; The Stuart B. Levy Center for the Integrated Management of Antimicrobial Resistance, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Notes

Disclaimer . The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Financial support. This work was supported by Merck & Co; the Francis P. Tally, MD Fellowship in Infectious Disease at Tufts Medical Center; the Tupper Research Fund; and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (grant number UL1TR002544 to M. A.).

References

- 1. Polage CR, Solnick JV, Cohen SH. Nosocomial diarrhea: evaluation and treatment of causes other than Clostridium difficile. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:982–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Crook DW, Walker AS, Kean Y, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection: meta-analysis of pivotal randomized controlled trials. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:S93–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile—more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:1932–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McDonald LC, Killgore GE, Thompson A, et al. An epidemic, toxin gene-variant strain of Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2005; 353:2433–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pépin J, Valiquette L, Gagnon S, Routhier S, Brazeau I. Outcomes of Clostridium difficile-associated disease treated with metronidazole or vancomycin before and after the emergence of NAP1/027. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102:2781–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pépin J, Alary M-E, Valiquette L, et al. Increasing risk of relapse after treatment of Clostridium difficile colitis in Quebec, Canada. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:1591–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mikamo H, Tateda K, Yanagihara K, et al. Efficacy and safety of fidaxomicin for the treatment of Clostridioides (Clostridium) difficile infection in a randomized, double-blind, comparative phase III study in Japan. J Infect Chemother 2018; 24:744–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Louie TJ, Miller MA, Mullane KM, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:422–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cornely OA, Crook DW, Esposito R, et al. Fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for infection with Clostridium difficile in Europe, Canada, and the USA: a double-blind, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:281–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Guery B, Menichetti F, Anttila V-J, et al. Extended-pulsed fidaxomicin versus vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection in patients 60 years and older (EXTEND): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3b/4 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2018; 18:296–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dai J, Gong J, Guo R. Real-world comparison of fidaxomicin versus vancomycin or metronidazole in the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2022; 78:1727–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Alsoubani M, Chow JK, Rodday AM, Kent D, Snydman DR. Comparative effectiveness of fidaxomicin vs vancomycin in populations with immunocompromising conditions for the treatment of Clostridioides difficile infection: a single-center study. Open Forum Infect Dis 2023; 11:ofad622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Thorpe CM, McDermott LA, Tran MK, et al. U.S.-based national surveillance for fidaxomicin susceptibility of Clostridioides difficile-associated diarrheal isolates from 2013 to 2016. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother 2019; 63:e00391-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Snydman DR, McDermott LA, Jenkins SG, et al. Epidemiologic trends in Clostridium difficile isolate ribotypes in United States from 2010 to 2014. Open Forum Infect Dis 2017; 4(Suppl 1):S391. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Snydman DR, McDermott LA, Jenkins SG, et al. Epidemiologic trends in Clostridioides difficile isolate ribotypes in United States from 2011 to 2016. Anaerobe 2020; 63:102185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis 2018; 66:e1–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Khuvis J, Alsoubani M, Mae Rodday A, Doron S. The impact of diagnostic stewardship interventions on Clostridiodes difficile test ordering practices and results. Clin Biochem 2023; 117:23–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Diseases 1987; 40:373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42:377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rao SR, Schoenfeld DA. Survival methods. Circulation 2007; 115:109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Martijn W, Heymans IE. Applied missing data analysis with SPSS and R studio. Amsterdam, 2019. https://bookdown.org/mwheymans/bookmi/. Accessed 23 January 2023.

- 22. Allison PD. Missing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage publications, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tieu JD, Williams RJ II, Skrepnek GH, Gentry CA. Clinical outcomes of fidaxomicin vs oral vancomycin in recurrent Clostridium difficile infection. J Clin Pharm Ther 2019; 44:220–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gentry CA, Nguyen PK, Thind S, Kurdgelashvili G, Skrepnek GH, Williams RJ II. Fidaxomicin versus oral vancomycin for severe Clostridium difficile infection: a retrospective cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019; 25:987–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Polivkova S, Krutova M, Capek V, Sykorova B, Benes J. Fidaxomicin versus metronidazole, vancomycin and their combination for initial episode, first recurrence and severe Clostridioides difficile infection—an observational cohort study. Int J Infect Dis 2021; 103:226–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Summers BB, Yates M, Cleveland KO, Gelfand MS, Usery J. Fidaxomicin compared with oral vancomycin for the treatment of severe Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea: a retrospective review. Hosp Pharm 2020; 55:268–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gallagher JC, Reilly JP, Navalkele B, Downham G, Haynes K, Trivedi M. Clinical and economic benefits of fidaxomicin compared to vancomycin for Clostridium difficile infection. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother 2015; 59:7007–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Appaneal HJ, Caffrey AR, Beganovic M, Avramovic S, LaPlante KL. Predictors of Clostridioides difficile recurrence across a national cohort of veterans in outpatient, acute, and long-term care settings. Am J Health System Pharm 2019; 76:581–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Falcone M, Tiseo G, Iraci F, et al. Risk factors for recurrence in patients with Clostridium difficile infection due to 027 and non-027 ribotypes. Clin Microbiol Infect 2019; 25:474–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Carlson TJ, Blasingame D, Gonzales-Luna AJ, Alnezary F, Garey KW. Clostridioides difficile ribotype 106: a systematic review of the antimicrobial susceptibility, genetics, and clinical outcomes of this common worldwide strain. Anaerobe 2020; 62:102142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Almutairi MS, Gonzales-Luna AJ, Alnezary FS, et al. Comparative clinical outcomes evaluation of hospitalized patients infected with Clostridioides difficile ribotype 106 vs. other toxigenic strains. Anaerobe 2021; 72:102440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aitken SL, Alam MJ, Khaleduzzuman M, et al. In the endemic setting, Clostridium difficile ribotype 027 is virulent but not hypervirulent. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2015; 36:1318–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Johnson S, Lavergne V, Skinner AM, et al. Clinical practice guideline by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA): 2021 focused update guidelines on management of Clostridioides difficile infection in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e1029–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]