Summary

Background

Current models for predicting intraoperative hemorrhage in cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSEP) are constrained by known risk factors and conventional statistical methods. Our objective is to develop an interpretable prediction model using machine learning (ML) techniques to assess the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage during CSEP in women, followed by external validation and clinical application.

Methods

This multicenter retrospective study utilized electronic medical record (EMR) data from four tertiary medical institutions. The model was developed using data from 1680 patients with CSEP diagnosed and treated at Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Chongqing Health Center for Women and Children, and Dezhou Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2023. External validation data were obtained from Liao Cheng Dong Chang Fu District Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2023. Random forest (RF), Lasso, Boruta, and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) were employed to identify the most influential variables in the model development data set; the best variables were selected based on reaching the λmin value. Model development involved eight machine learning methods with ten-fold cross-validation. Accuracy and decision curve analysis (DCA) were used to assess model performance for selection of the optimal model. Internal validation of the model utilized area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), sensitivity, specificity, Matthews correlation coefficient, and F1 score. These same indicators were also applied to evaluate external validation performance of the model. Finally, visualization techniques were used to present the optimal model which was then deployed for clinical application via network applications.

Findings

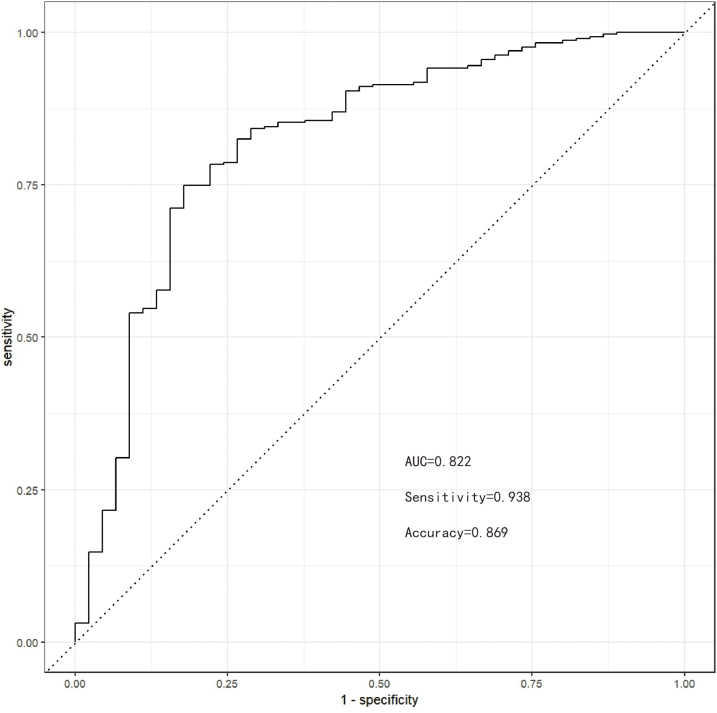

Setting λmin at the value of 0.003, the optimal variable combination containing 9 variables was selected for model development. The optimal prediction model (Bayes) had an accuracy of 0.879 (95% CI: 0.857–0.901) an AUC of 0.882 (95% CI: 0.860–0.904), a DCA curve maximum threshold probability of 0.41, and a maximum return of 7.86%. The internal validation accuracy was 0.869 (95% CI: 0.847–0.891), an AUC of 0.822 (95% CI: 0.801–0.843), a sensitivity of 0.938, a specificity of 0.422, a Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.392, and an F1 score of 0.925. In the external validation, the accuracy was 0.936 (95% CI: 0.913–0.959), an AUC of 0.853 (95% CI: 0.832–0.874), a sensitivity of 0.954, a specificity of 0.5, a Matthews correlation coefficient of 0.365, and an F1 score of 0.966. This indicates that the prediction model performed well in both internal and external validation.

Interpretation

The developed prediction model, deployed in the network application, is capable of forecasting the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage during CSEP. This tool can facilitate targeted preoperative assessment and clinical decision-making for clinicians. Prospective data should be utilized in future studies to further validate the extended applicability of the model.

Funding

Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province; Qilu Hospital of Shandong University.

Keywords: Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy, Intraoperative hemorrhage, Interpretable machine learning, Prediction model, Visualization

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The extent of hemorrhaging in patients with cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSEP) significantly impact surgical outcomes. We conducted a comprehensive search on PubMed and the Cochrane Library, without language restrictions, for studies published within the last decade that focused on predicting intraoperative bleeding in patients with CSEP, using the search terms “(CSEP or CSP) and (intraoperative hemorrhage) and (prediction)”. While some studies have investigated factors influencing intraoperative bleeding in patients with CSEP, most have utilized traditional statistical methods to perform multivariate analysis based on single factor and often overlooked potential covariance or nonlinear relationships between variables, thereby diminishing its effectiveness in addressing nonlinear problems.

Added value of this study

We developed a predictive model for intraoperative hemorrhage in patients with CSEP using 9 predictive variables derived from electronic medical record (EMR) data of four hospitals, and demonstrated its external validity. The Bayes algorithm yielded the highest accuracy (0.879), clinical net benefit (7.86%), and AUC (0.882).

Implications of all the available evidence

We demonstrated that leveraging EMR data as predictive variables and employing ML for predictive modeling could advance personalized medicine and enhance healthcare quality.

Introduction

Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy (CSEP) is a complication of pregnancy following cesarean section, characterized by early implantation in the scar tissue from a previous cesarean section.1 As gestational weeks progress, failure to detect and promptly address this condition through surgery may lead to late-stage uterine rupture, intraoperative hemorrhage, and potential jeopardy to the mother’s life.2 Regardless of the surgical approach employed for patients with CSEP, the extent of intraoperative bleeding significantly impacts surgical success.3 While recent studies have explored influencing factors of intraoperative bleeding in patients with CSEP using logistic regression for multivariate analysis based on single factors,4, 5, 6 this method often overlooks potential covariance or nonlinear relationships between variables, thereby diminishing its effectiveness in addressing nonlinear problems.7

In recent years, the machine learning (ML) approach derived from electronic medical records (EMR) has garnered attention and recognition from clinicians. The widespread utilization of EMR in healthcare facilities enables more precise and convenient collection of patients’ clinical data.8 Similarly, ML applications have experienced exponential growth and accelerated innovation in recent years.9 In comparison to traditional statistical methods, ML algorithms exhibit fewer constraints on data and possess the capability to effectively model complex datasets,10 leading to their increasing adoption in the medical domain. For instance, researchers have devised an acute kidney injury (AKI) prediction model capable of accurately forecasting moderate to severe AKI 48 h prior to its onset.11 Similarly, You Won Lee et al.12 developed six machine learning models and successfully applied them to predict malaria using patient information. However, due to the complexity of the ML model, specifically the presence of a so-called ‘black box’, direct explanation is challenging.13 Therefore, model interpretation tools play a crucial role. We utilized the model interpretation tool (ibreakdown) to construct a model interpreter and visually present the contribution of each variable concisely. Furthermore, this study also leverages the shiny web-based tool for deploying the model to a network application, facilitating direct utilization by clinicians for program prediction without requiring R installation or programming background knowledge.14

Methods

Study participants

This is a multicenter retrospective study that primarily comprises EMR data from four tertiary medical institutions. This study comprises three primary stages: the selection of research subjects and screening of predictive variables, the construction and evaluation of multiple prediction models, and the development of a web-based application for the optimal model. The model development data included 1118 patients with CSEP treated at Qilu Hospital of Shandong University between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2023; 189 patients with CSEP treated at Chongqing Health Center for Women and Children and 373 patients with CSEP treated at Dezhou Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital during the same period. The treatment methods are based on the diagnosis of transvaginal sonography combined with surgical strategies derived from extensive clinical experience at the hospital. These include ultrasound-guided suction curettage combined with hysteroscopy surgery, laparoscopic-assisted suction curettage combined with hysteroscopy surgery, and laparoscopic scar pregnancy lesion clearance combined with suction curettage. External validation data were obtained from Liao Cheng Dong Chang Fu District Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital for the period between January 1, 2021, and December 31, 2023. The hospital inclusion criteria are consistent, requiring patients to be aged between 25 and 40 years old with a history of cesarean section. Furthermore, patients firstly diagnosed with CSEP must have a confirmed single pregnancy via transvaginal ultrasonography, with absence of uterine rupture and stable hemodynamics. Additionally, those without surgical contraindications are required to undergo pregnancy termination and participate in follow-up care. Lastly, the study excluded individuals who were unable to tolerate surgery or had other malignancies.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure for model development was intraoperative hemorrhage, defined as a blood loss of 300 or more during the CSEP surgical procedure.3

Model predictors

Initially, 20 factors influencing major bleeding during CSEP were identified through systematic reviews, meta-analyses,15 and expert clinical opinions. These factors encompass demographic characteristics, reproductive history, medical background, clinical symptoms, and ultrasound examination features. Furthermore, candidate variables underwent additional screening based on principles of variable reduction to determine their inclusion in the model.16 Random Forest (RF) is a classification algorithm that consists of multiple decision trees. It builds machine learning models by randomly sampling the training data and searching for the optimal splitting solution. Each decision tree in RF is built using feature metrics aligned with the dataset attributes,17,18 effectively assessing the importance of each feature.19 Lasso can select variables and reduce model complexity through a series of parameters, thus preventing overfitting. The complexity of Lasso is controlled by λ, ultimately resulting in a model with fewer variables. It conducts 10-fold cross-validation to determine the λmin value, where the minimum error serves as the criterion for selecting predictive variables.20,21 In contrast to conventional feature selection algorithms, Boruta operates as a wrapper-based approach for selecting features. Its objective lies in identifying the feature set that exhibits maximum relevance to the dependent variable rather than focusing solely on creating an optimized compact subset tailored for specific models.22 Through iterative elimination of low-correlation features, it effectively mitigates signal noise and yields consistent classification performance.23 Meanwhile, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) stands out as an influential ensemble learning technique rooted in the framework of classification trees; it amalgamates lower-precision classifiers into higher-precision ones via iterative computations. The resulting integrated classifier takes shape as a decision tree interconnected by branches—a robust instrument for effective classification.24

Specifically, we employed RF, Lasso, Boruta, and XGBoost to model the 20 influencing factor variables. Subsequently, we ranked the variables with non-zero coefficients based on their impact on the outcome variables and identified common variables by taking the intersection of those selected by all four methods.

Statistics

The determination of an adequate minimum sample size for developing a multivariate predictive model hinges on ensuring a robust representation of individuals and outcome events in relation to predictor parameters.25 The combined sample size from four medical institutions provided ample support for utilizing 20 predictive variables in both modeling and validation phases. Specifically, there were 1680 cases in the modeling dataset, encompassing 197 (11.73%) patients who experienced intraoperative hemorrhage; while external validation involved 295 cases. Wang X et al.’s analysis26 demonstrated that given a known exposure proportion, a sample size calculator can be employed for computation purposes. When “Expected value of the (Cox-Snell) R-squared of the new model” is set to 0.9, “Number of candidate predictor parameters for potential inclusion in the new model” is set to 9, “Level of shrinkage desired at internal validation after developing the new model” is set to 0.9, “Overall outcome proportion (for a prognostic model) or overall prevalence (for a diagnostic model)” is set to 0.12, and “C-statistic reported in an existing prediction model study” is set to 0.8, we estimate the sample size to be 589. Additionally, we also refer to a widely applied principle, namely, 10 events per variable (10 EPV). Of course, for ML, the larger the sample size, the more robust the prediction model it can build. The study’s sample size aligns with analytical requisites. Continuous variables in the dataset are reported as means with standard deviations, whereas categorical variables are summarized as counts and percentages. The gaze function within the autoReg package is designed to automatically apply appropriate statistical methods based on the characteristics of the data (quantitative, qualitative, etc.) and generate descriptive statistics. All statistical analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.3.3.

Model development and comparison

Within the tidymodels framework, the modeling data were randomly partitioned into 80% for training and 20% for testing (internal validation). Subsequently, the data underwent preprocessing, with categorical variables being treated as dummy variables, near-zero variance variables being eliminated, and numerical variables being standardized to mitigate overfitting. Finally, a prediction model was constructed using the aforementioned 9 predictor variables. The mice and vim packages were employed for the processing of missing data. Among 1680 patients, 19 cases presented with partial missing data for some variables, with an overall missing rate of 1.13%. The data missing was entirely random. With the assistance of the RF algorithm, we carried out 5 imputations with 50 iterations on the original missing data and accomplished a sensitivity analysis. Eight machine learning models were utilized to forecast major bleeding during CSEP: naive bayes (Bayes), multi-layer perception (MLP), decision tree (DT), K-nearest neighbor algorithm (KNN), logistic regression (LR), RF, support vector machine (SVM), and XGBoost. Furthermore, the eight models were evaluated and compared using accuracy, the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and decision curve analysis (DCA). Internal and external validations of the optimal model were conducted using sensitivity, specificity, Matthews correlation coefficient, and F1 score.

Model interpretation and network application

Interpretability denotes elucidating how ML models produce results. The opacity inherent in ML models often impedes their effective utilization in clinical settings, prompting extensive inquiry into enhancing their interpretability.27,28 Herein, we have devised an intuitive model interpreter leveraging iBreakDown package capabilities; it not only expounds upon predictive factors but also interprets projected patient outcomes. This tool operates independently from any particular model and utilizes input predictor variables for result interpretation while enabling predictions for individual cases and generating partial dependence plots (PDP) for visualizing variable significance. Furthermore, employing Shiny package functionalities facilitated integrating 9 chosen predictive variables and optimal modeling into an interactive web application.

Ethics

The study reporting adheres to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines and has obtained informed consent from all participants, and only anonymous data was used in the analysis. The study has been reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Qilu Hospital, Shandong University, with approval number KYLL-202311-038.

Role of funding source

The funders of this study were not engaged in the study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, nor did they participate in the composition of the paper. All authors had the right to access the raw data, and the corresponding author was responsible for determining whether to publish.

Results

Population characteristics

The retrospective study utilized a sample size of 1680 patients with ectopic pregnancy in cesarean scar to develop the predictive model. Initially, 1889 patients were extracted from the EMR, but a subset was excluded from the sample, comprising 169 patients with drug pretreatment, 20 patients with gestational trophoblastic disease, 11 patients who underwent difficult surgery, and 9 patients with tumors. The remaining 1680 patients were randomly divided into separate training and test sets (internal validation set) in an 8:2 ratio. Additionally, an external validation was performed using a cohort of 295 patients. The AIC of the logistic regression models fitted by the 5 imputed data sets were 825.61, 825.73, 824.7, 825.61, and 825.56, respectively. Taking the third imputed data set with the smallest AIC as the control, the remaining 4 imputed data sets were compared with it, and the Deviances were −0.9099, −0.1246, 0.1270, and 0.0462, respectively, with small differences. Moreover, when these 5 imputed data sets were respectively compared with the original data, the p-values of the chi-square tests were 0.1111, 0.1199, 0.1138, 0.1032, and 0.1325, respectively, indicating no significant differences between the imputed data and the original data. Since the AIC of the third imputed data set was the smallest among all the imputed data sets, the third imputed data set was selected as the complete imputed data without missing values for analysis (Supplementary Fig. S1). Refer to Fig. 1 for a detailed description of the study design. Among the 1680 patients with CSEP, 197 (11.73%) experienced intraoperative hemorrhage. For intergroup comparison, the p values of gestational age, duration of vaginal bleeding before surgery, average diameter of the gestational sac or mass, anterior myometrium thickness, Serum hemoglobin (HGB) level, Serum β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) level, gestational sac or mass, vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain before admission, uterine arteriovenous fistula, placenta accrete spectrum disorders in early pregnancy, and blood flow grading on ultrasound imaging (Adler Grading) were all less than 0.05, indicating statistically significant differences. Please refer to Table 1 for demographic and clinical characteristics; Fig. 2 illustrates the correlation between variables; and Fig. 3 presents an impact diagram.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart for model development and validation.

Table 1.

Clinical data baseline table of study subjects grouped by intraoperative hemorrhage.

| Predictive variables | Levels | Without intraoperative hemorrhage (bleeding volume < 300 ml) (N = 1483) | Intraoperative hemorrhage (bleeding volume ≥ 300 ml) (N = 197) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | Mean ± SD | 33.7 ± 4.8 | 33.6 ± 4.7 | 0.632 |

| Gestational age (d) | Mean ± SD | 55.6 ± 19.0 | 72.7 ± 22.2 | <0.001 |

| Number of pregnancies | Mean ± SD | 3.8 ± 1.6 | 3.7 ± 1.6 | 0.608 |

| Number of miscarriages | Mean ± SD | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 1.9 ± 1.4 | 0.795 |

| Number of previous cesarean sections | Mean ± SD | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 0.376 |

| Time since last cesarean delivery (m) | Mean ± SD | 62.1 ± 44.0 | 61.9 ± 43.4 | 0.969 |

| Duration of vaginal bleeding before surgery (d) | Mean ± SD | 6.0 ± 10.2 | 12.2 ± 15.8 | <0.001 |

| Duration of abdominal pain (d) | Mean ± SD | 1.0 ± 4.1 | 1.9 ± 6.6 | 0.065 |

| Average diameter of the gestational sac or mass (cm) | Mean ± SD | 2.4 ± 1.5 | 4.9 ± 2.0 | <0.001 |

| Anterior myometrium thickness (cm) | Mean ± SD | 0.3 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| Serum HGB level (g/L) | Mean ± SD | 120.7 ± 14.4 | 111.6 ± 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Serum β-HCG level (mIU/ml) | Mean ± SD | 37329.2 ± 46169.7 | 50975.0 ± 66615.4 | 0.006 |

| Gestational sac or mass | Mass | 310 (20.9%) | 82 (41.6%) | <0.001 |

| Sac | 1173 (79.1%) | 115 (58.4%) | ||

| Past history of CSEP | Negative | 1454 (98%) | 196 (99.5%) | 0.248 |

| Positive | 29 (2%) | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Vaginal bleeding or abdominal pain before admission | None | 463 (31.2%) | 47 (23.9%) | <0.001 |

| Bleeding | 718 (48.4%) | 135 (68.5%) | ||

| Abdominal pain | 287 (19.4%) | 15 (7.6%) | ||

| Both | 15 (1%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| Fetal cardiac activity | Negative | 898 (60.6%) | 118 (59.9%) | 0.921 |

| Positive | 585 (39.4%) | 79 (40.1%) | ||

| Embryo bud | Negative | 754 (50.8%) | 101 (51.3%) | 0.971 |

| Positive | 729 (49.2%) | 96 (48.7%) | ||

| Uterine arteriovenous fistula | Negative | 1470 (99.1%) | 176 (89.3%) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 13 (0.9%) | 21 (10.7%) | ||

| Placenta accrete spectrum disorders in early pregnancy | Negative | 1472 (99.3%) | 180 (91.4%) | <0.001 |

| Positive | 11 (0.7%) | 17 (8.6%) | ||

| Blood flow grading on ultrasound imaging | None | 181 (12.2%) | 13 (6.6%) | <0.001 |

| Sparse | 371 (25%) | 25 (12.7%) | ||

| Rich | 292 (19.7%) | 82 (41.6%) | ||

| Very rich | 639 (43.1%) | 77 (39.1%) |

Quantitative variables are reported as means and standard deviations, whereas qualitative variables are expressed as counts (percentages). p-values for quantitative variables were calculated using the Student’s t-test to assess significance, while Pearson’s chi-square test was employed for qualitative variables. Total (n = 1680). CSEP: cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy; SD: standard deviation; p < 0.05.

Fig. 2.

The relationship between variables is depicted graphically using scatter plots, density plots, histograms, and box plots to gain insights into their distribution.

Fig. 3.

The Sankey diagram effectively illustrates the allocation of the research subject across various predictor variables.

Variable screening

The RF algorithm generated 500 trees, and each split of the decision tree randomly selected 4 predictive variables. The out-of-bag data misclassification rate was 10.18% (Supplementary Fig. S2). In comparison, mean decrease accuracy (MDA) utilized information entropy to address overfitting, while mean decrease gini (MDG) was suitable for high-dimensional or noisy data29; thus, this study opted for MDG. Ultimately, the 20 most influential predictive variables affecting the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage were ranked in descending order of importance (Supplementary Figs. S3 and S4).

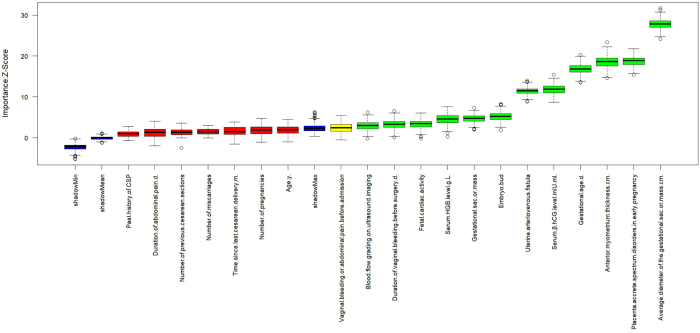

When λmin is set to 0.003 in the Lasso model, 15 predictive variables exhibit non-zero coefficients. The screening process is detailed in Supplementary Figs. S5 and S6. The model’s bias demonstrates minimal variation within the interval [λ1se, λmin].30 The ranking of non-zero predictive variables is presented in Supplementary Fig. S7, where the coefficient for anti-myometrium thickness is −4.95 and that for placental villus implantation in early prediction is 2.25, contributing significantly to forward and reverse prediction of main outcome measures respectively. Boruta iteratively removed statistically irrelevant features and identified all features that exhibited strong or weak correlations with the output variables.31 After 400 iterations of the algorithm, 12 important variables were confirmed. Please refer to Supplementary Figs. S8 and S9 for the changes in importance scores of each variable during Boruta operation and the evolution of Z-scores during operation. XGBoost’s faster computation speed is advantageous, leading to accurate training results and relaxed data requirements. The model demonstrated strong generalization ability and increased scalability,32 ultimately identifying 19 predictor variables. The importance of these variables is illustrated in Supplementary Fig. S10.

The predictive variables identified by RF, Lasso, Boruta, and XGBoost were selected as the common elements for developing the prediction model. Nine predictive variables were included: gestational age, duration of vaginal bleeding before surgery, average diameter of the gestational sac or mass, anterior myometrium thickness, Serum HGB level, Serum β-hCG level, uterine arteriovenous fistula, placenta accrete spectrum disorders in early pregnancy, and blood flow grading on ultrasound imaging. Please refer to Supplementary Fig. S11 for Wayne diagram.

Model development and performance comparison

In the training set, the Bayes model exhibited the highest accuracy at 0.879 (95% CI: 0.857–0.901), followed by the Logistic model at 0.818 (95% CI: 0.798–0.838). In terms of AUC value comparison, the Bayes model achieved a value of 0.882 (95% CI: 0.860–0.904), slightly lower than the maximum value of RF model at 0.888 (95% CI: 0.866–0.910). When considering net return rate, the Bayes model demonstrated a maximum threshold probability of 0.41 and a corresponding maximum return rate of 7.86%, surpassing all other models in this aspect. In the training set, when the cutoff value was set at 0.968, the sensitivity and specificity were 0.769 and 0.868 respectively (Supplementary Figs. S12–S14).

Internal and external validation of the final model

In internal validation, the accuracy of the Bayes model on the test set was 0.869 (95% CI: 0.847–0.891), AUC was 0.822 (95% CI: 0.801–0.843), sensitivity was 0.938, specificity was 0.422, Matthews correlation coefficient was 0.392, and F1 score was 0.925. In external validation, the accuracy of the Bayes model was 0.936 (95% CI: 0.913–0.959), AUC was 0.853 (95% CI: 0.832–0.874), sensitivity was 0.954, specificity was 0.5, and Matthews correlation coefficient was 0.365, with an F1 score of 0.966. This indicated that in external validation, the model had excellent ability to identify intraoperative hemorrhage in patients with CSEP. The ROC curves, Lift curves, and confusion matrices of the model in internal and external validations are shown in Supplementary Figs. S15–S20 respectively.

Interpretation of the model

The iBreakDown package can aid clinicians in making predictions. To begin with, PDP were utilized to elucidate the influence of individual predictive variables on the primary outcome measures. As depicted in Supplementary Figs. S21 and S22, there is a positive correlation between the average diameter of the gestational sac or mass and the prediction of intraoperative hemorrhage during CSEP surgery; specifically, a larger value corresponds to a higher risk of intraoperative hemorrhage in patients with CSEP during surgery. However, while there are fluctuations in the prediction of intraoperative hemorrhage during CSEP surgery when the anterior myometrium thickness is below 0.7 cm, it generally exhibits a negative correlation—indicating that a thinner myometrium is associated with an increased risk of intraoperative hemorrhage in patients with CSEP during surgery. This finding aligns with clinical practice. Furthermore, patient prediction results are primarily employed to forecast individual probabilities of experiencing intraoperative hemorrhage. By randomly selecting main outcome measures as individuals with and without intraoperative risk of significant adverse events and calculating their predicted probabilities (0 and 0.863 respectively), we obtained results consistent with those observed in actual main outcome measures (Supplementary Figs. S23 and S24).

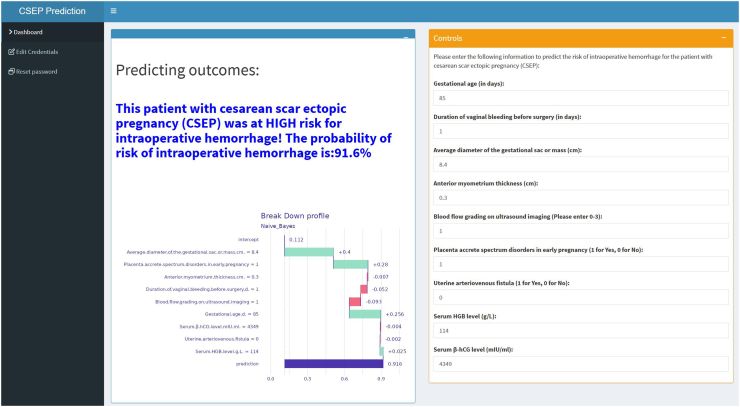

Development of convenient applications

Our developed prediction model can be executed locally or deployed on the Internet via Shiny, enabling the sharing of applications without the need for R-code software. Upon inputting the actual values of the 9 predicted variables required by the model, the application will automatically calculate the probability of intraoperative hemorrhage in patients with CSEP, as depicted in Fig. 4. The web application is accessible online (https://cnsdql.shinyapps.io/csep-prediction-model/, test account: SuperManagerr, password: QiLuhospitall). New users can also register for free using their personal email.

Fig. 4.

The application will automatically estimate the likelihood of intraoperative hemorrhage in CSEP patients. CSEP: cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy.

Discussion

This study has developed a ML model based on EMR data from multiple center hospitals, demonstrating strong discriminative ability and clinical utility in predicting the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage in patients with CSEP. The model’s performance has been externally validated at another medical institution. In comparison with previously published models, this novel model achieved superior predictive accuracy through rigorous variable selection, development, validation, interpretation, and network deployment. It is characterized by its convenience and practicality, offering substantial clinical value to guide rapid decision-making for clinicians. This can facilitate targeted preoperative preparations such as ensuring an adequate supply of blood transfusion units or selecting experienced surgical teams. Ultimately, these measures have the potential to significantly reduce intraoperative complications and improve surgical success rates while informing postoperative care priorities.

It is widely acknowledged that ML models offer superior predictive performance compared to traditional linear models.33 This advantage enables the construction of a relatively robust model from complex data.34 ML excels in handling heterogeneous multidimensional data, as demonstrated by the inclusion of nine predictive variables in this study, such as the average diameter of the gestational sac or mass and the thickness of the anterior myometrium, which exhibited high heterogeneity. Furthermore, the utilization of EMR data in this study ensured accuracy through manual review prior to implementation. Leveraging EMR data as predictive variables and employing ML for predictive modeling can facilitate personalized medicine and enhance care quality.35 Additionally, visualization strategies were employed to elucidate the predictive model and develop practical network applications. This step is essential for dispelling concerns regarding black box models and reinstating confidence in ML within the medical field.36 Moreover, during model development, cross-validation, internal validation, and external validation were utilized to maximize reproducibility by pre-setting random seeds—a prerequisite for ensuring clinical significance through model interpretability.37

Recent studies have focused on intraoperative hemorrhage among patients with CSEP. Yang F et al.5 utilized logistic regression analysis to develop a predictive model based on MRI indicators for three key influencing factors from a cohort comprising 187 cases across tertiary medical facilities in Southwest China aimed at assessing intraoperative hemorrhage risk during cesarean sections. Their model achieved an AUC value of 0.896 during training and 0.915 during validation; however, due to limited sample size and absence of external validation, further scrutiny is required regarding its predictive performance. Similarly, Lin Y et al.6 conducted an analysis using logistic regression within a tertiary medical institution involving only 55 cases, and identified clinical classification and gestational sac diameter as significant contributors towards major intraoperative bleeding. In addition to small sample sizes, in line with previous models utilizing similar methods, it was noted that logistical regression struggles with addressing variable nonlinearity.7 As emphasized by Lin Y, the findings necessitate additional confirmation through increased case numbers and randomized controlled trials.

We developed and externally validated an intraoperative hemorrhage prediction model for patients with CSEP using 9 clinical variables available in the EMR of 4 hospitals. RF, Lasso, Boruta, and XGBoost were employed to screen the 20 influential variables from the model development data with the aim of addressing collinearity through L1 regularization. We selected these 20 variables for specific reasons. First, the purpose of this study was to develop a practical predictive application that could be used in clinical settings, so we needed to select a small number of patient markers that were easily accessible. Considering practicality, if one marker can achieve the prediction goal, it should not include other variables. More importantly, these predictor variables are preoperative markers. Second, based on previous literature and meta-analysis results, these 20 variables are commonly used indicators in similar studies. Finally, it is worth noting that the data used in this study covers 15 years of patient information and was analyzed retrospectively; in addition, these 20 variables are the most comprehensive and easily accessible records in our electronic medical records. To identify the best fitting effect, we applied eight ML algorithms to fit each of the 9 predictive variables individually. Ultimately, the Bayes algorithm yielded a model with superior accuracy (0.879), clinical net benefit (7.86%), and AUC (0.882). Similarly, this model demonstrated excellent performance on both internal and external validation sets.

Ban Yet al.3 reported that the average diameter of the gestational sac or mass and anterior myometrium thickness were independent factors influencing intraoperative hemorrhage, and subsequently developed a clinical practical classification based on this finding. Our study yields consistent results, with these two variables emerging as primary indicators contributing significantly to intraoperative hemorrhage. This is further supported by our Shiny-developed network application.

Intraoperative hemorrhage during CSEP represents a significant surgical complication. Upon diagnosis, proactive measures must be implemented for its management. Equally crucial is the accurate prediction of false negative (missed diagnosis rate) and false positive (misdiagnosis rate) outcomes by the model, necessitating a high level of accuracy. Notably, the Bayesian model demonstrated superior performance. Intriguingly, the final cutoff value for the Bayesian model was 0.968, with a sensitivity of 0.769, specificity of 0.868, and a maximum Youden index of 0.637 achieved. This indicates that an individual prediction probability exceeding 0.968 is essential to fully confirm the risk of major bleeding. Furthermore, in accordance with ROC curve principles, reducing the cutoff value can enhance sensitivity while decreasing specificity. However, the outcome is a reduction in the missed diagnosis rate and an increase in the misdiagnosis rate. For instance, with a cutoff value of 0.5, the sensitivity is 0.924, specificity is 0.513, and the Youden index is 0.437; resulting in a missed diagnosis rate of 7.6% and a misdiagnosis rate of 48.7%. It should be noted that such adjustments are made under the premise that misdiagnosis will not significantly impact clinical benefits. Nevertheless, given that intraoperative hemorrhage as an outcome variable is binary, any non-zero result from the ibreakdown package for patients with CSEP indicates a risk of intraoperative hemorrhage.

We need to acknowledge several limitations of our study. Firstly, this study was conducted in China and the selection of study subjects was primarily based on local populations, with treatment strategies matched according to practical clinical types. Therefore, there may be potential biases in extrapolating the results to global populations, which is a common issue with such prediction models.7,8,38 However, it can be easily recalibrated for use in other countries39 and we welcome the opportunity to do so. Secondly, there is currently no standard for calculating sample size for ML-based prediction models,8 therefore, we have adopted multiple validation methods to enhance the model’s ability to predict intraoperative hemorrhage in patients undergoing CSEP surgery. Thirdly, the 9 predictive variables selected by the development model already exist at admission; however, in real-world clinical settings, intraoperative factors such as operation time and doctors’ experience also affect the risk of intraoperative massive bleeding. Additionally, as advancements have been made in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques over the past 15 years when our study subjects were treated, theoretically this could lead to a reduction in intraoperative bleeding during CSEP surgeries. Consequently when extrapolated to the general population it may result in an increased rate of misdiagnosis within our model. To address this issue we are collecting data from more hospitals over recent years and hope to further optimize the model using recent data from multiple centers.7 Finally, the data used for model development was obtained from patients admitted into a specific medical institution rather than large databases, which might introduce Berkson bias.40,41 Fortunately, compared with published studies,5,6 our sample size is relatively large. Therefore, we believe that developed model will help us better understand risk of major intra-operative bleeding among patient undergoing CSEP.

In conclusion, we have developed a clinically advantageous, convenient, and practical network application. While prospective validation is still necessary, it is now feasible to anticipate the risk of significant complications in CSEP surgery, thereby enabling physicians to make targeted clinical decisions proactively.

Contributors

Baoxia Cui and Qingqing Liu contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Xinli Chen, Siyuan Yang, Longyun Sun, Qingqing Liu, Yiping Hao, Xinlin Jiao, Teng Zhang, Wenjing Zhang, Yanli Ban, Guowei Tao, Dongxia Guo, Fanrong Meng, Bao Liu. The primary analysis was conducted by Chen Xinli and Cui Baoxia, while the initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by Chen Xinli. Baoxia Cui, Chen Xinli, Yanli Ban, Guowei Tao, Huan Zhang and Yugang Chi had access to and verify the underlying data reported in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The data and code that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (Baoxia Cui). The data are not publicly available due to containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this work.

Acknowledgements

We express our gratitude to the data providers involved in this study, including Qilu Hospital of Shandong University, Chongqing Health Center for Women and Children, Dezhou Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, and Liaocheng Dongchangfu District Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital. Additionally, we acknowledge the invaluable support from the School of Public Health of Shandong University in conducting data analysis. Furthermore, we extend our sincere appreciation to the patients who consented to utilize their anonymous medical records for this study; without their participation, this research would not have been feasible.

Footnotes

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102969.

Contributor Information

Guowei Tao, Email: taoguowei2006@126.com.

Baoxia Cui, Email: cuibaoxia@sdu.edu.cn.

Appendix ASupplementary data

Supplementary Fig. S1.

Supplementary Fig. S1. Data distribution after imputation. The values on the horizontal axis respectively represent the number of multiple imputations, among which 0 represents the original data. The values on the vertical axis represent the range of values of the variable. The red dots represent the post-imputation data. When the post-imputation data falls within the range of values on the vertical axis, it indicates that the imputed data has a high degree of credibility.

Supplementary Fig. S2.

Supplementary Fig. S2. The relationship between tree number and out-of-bag(20 characteristic variables).

Supplementary Fig. S3.

Supplementary Fig. S3. Descending order of importance of 20 predictive variables, with the left showing MDA, and the right showing MDG. MDA: mean decrease accuracy; MDG: mean decrease gini.

Supplementary Fig. S4.

Supplementary Fig. S4. List 20 predictive variables in descending order of importance.

Supplementary Fig. S5.

Supplementary Fig. S5. The screening process of predictive variables(coefficient distribution).

Supplementary Fig. S6.

Supplementary Fig. S6. The screening process of predictive variables(cross validation).

Supplementary Fig. S7.

Supplementary Fig. S7. 9 non-zero predictive variables selected by Lasso regression screening.

Supplementary Fig. S8.

Supplementary Fig. S8. The changing of importance scores of each variable during Boruta's running process. In these box plots, the red indicates the rejected features, the yellow indicates the features to be determined, and the blue respectively represents the significance of the minimum, average, and maximum shadow features, namely the magnitude of the Z-Score.

Supplementary Fig. S9.

Supplementary Fig. S9. The changing of Z-scores during the running of Boruta. These curves respectively indicate the changing trends of the Z-Scores of the rejected features (red), the features to be determined (yellow), and the minimum, average, and maximum shadow features (blue) when the algorithm iterates 400 times.

Supplementary Fig. S10.

Supplementary Fig. S10. The variables selected by XGBoost sorted by importance. XGBoost: Extreme Gradient Boosting.

Supplementary Fig. S11.

Supplementary Fig. S11. Variable Wayne diagram screened by four methods.

Supplementary Fig. S12.

Supplementary Fig. S12. The accuracy of each model. The error bars respectively represent the mean accuracy and the 95% confidence intervals of the eight models.

Supplementary Fig. S13.

Supplementary Fig. S13. The ROC curve of each model.

Supplementary Fig. S14.

Supplementary Fig. S14. The DCA curve of each model.

Supplementary Fig. S15.

Supplementary Fig. S15. The ROC curve for internal validation.

Supplementary Fig. S16.

Supplementary Fig. S16. The Lift curve for internal validation.

Supplementary Fig. S17.

Supplementary Fig. S17. Confusion matrices for internal validation.

Supplementary Fig. S18.

Supplementary Fig. S18. The ROC curve for external validation.

Supplementary Fig. S19.

Supplementary Fig. S19. The Lift curve for external validation.

Supplementary Fig. S20.

Supplementary Fig. S20. Confusion matrices for external validation.

Supplementary Fig. S21.

Supplementary Fig. S21. The PDP for the average diameter of the gestational sac or mass. PDP: partial dependence plots.

Supplementary Fig. S22.

Supplementary Fig. S22. The PDP for anterior myometrium thickness. PDP: partial dependence plots.

Supplementary Fig. S23.

Supplementary Fig. S23. Prediction probability of individuals without intraoperative hemorrhage.

Supplementary Fig. S24.

Supplementary Fig. S24. Prediction probability of individuals with intraoperative hemorrhage.

References

- 1.Liu L., Ross W.T., Chu A.L., Deimling T.A. An updated guide to the diagnosis and management of cesarean scar pregnancies. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;32(4):255–262. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan K.L., Jiang L., Chen Y.M., et al. Local intra-gestational sac methotrexate injection followed by dilation and curettage in treating cesarean scar pregnancy. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;302(2):439–445. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05619-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ban Y., Shen J., Wang X., et al. Cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy clinical classification system with recommended surgical strategy. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(5):927–936. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Braud L.V., Knez J., Mavrelos D., Thanatsis N., Jauniaux E., Jurkovic D. Risk prediction of major haemorrhage with surgical treatment of live cesarean scar pregnancies. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2021;264:224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2021.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang F., Yang X., Jing H., et al. MRI-based scoring model to predict massive hemorrhage during dilatation and curettage in patients with cesarean scar pregnancy. Abdom Radiol (NY) 2023;48(10):3195–3206. doi: 10.1007/s00261-023-03968-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin Y., Xiong C., Dong C., Yu J. Approaches in the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy and risk factors for intraoperative hemorrhage: a retrospective study. Front Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.682368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi Ying, Zhang Guangming, Ma Chiye, et al. Machine learning algorithms to predict intraoperative hemorrhage in surgical patients: a modeling study of real-world data in Shanghai, China. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23(1):156. doi: 10.1186/s12911-023-02253-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu J., Xu J., Li M., et al. Identification and validation of an explainable prediction model of acute kidney injury with prognostic implications in critically ill children: a prospective multicenter cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;68 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Zaiti S.S., Alghwiri A.A., Hu X., et al. A clinician’s guide to understanding and critically appraising machine learning studies: a checklist for Ruling Out Bias Using Standard Tools in Machine Learning (ROBUST-ML) Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2022;3:125–140. doi: 10.1093/ehjdh/ztac016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ren W., Li D., Wang J., Zhang J., Fu Z., Yao Y. Prediction and evaluation of machine learning algorithm for prediction of blood transfusion during Cesarean Section and Analysis of Risk factors of hypothermia during Anes-hesia Recovery. Comput Math Method Med. 2022;2022 doi: 10.1155/2022/8661324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 11.Dong J., Feng T., Thapa-Chhetry B., et al. Machine learning model for early prediction of acute kidney injury (AKI) in pediatric critical care. Crit Care. 2021;25(1):288. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03724-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee Y.W., Choi J.W., Shin E.H. Machine learning model for predicting malaria using clinical information. Comput Biol Med. 2021;129 doi: 10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azodi C.B., Tang J., Shiu S.H. Opening the black box: interpretable machine learning for geneticists. Trends Genet. 2020;36:442–455. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2020.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jiang Z., Cao W., Chu H., Bazerbachi F., Siegel L. RIMeta: an R shiny tool for estimating the reference interval from a meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2023;14(3):468–478. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Y. Risk factors for massive hemorrhage during the treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2021;303(2):321–328. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05877-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venkatesh K.K., Jelovsek J.E., Hoffman M., et al. Postpartum readmission for hypertension and pre-eclampsia: development and validation of a predictive model. BJOG. 2023;130(12):1531–1540. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farhadian M., Torkaman S., Mojarad F. Random forest algorithm to identify factors associated with sports-related dental injuries in 6 to 13-year-old athlete children in Hamadan, Iran-2018 -a cross-sectional study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2020;12(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13102-020-00217-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi G., Liu G., Gao Q., et al. A random forest algorithm-based prediction model for moderate to severe acute postoperative pain after orthopedic surgery under general anesthesia. BMC Anesthesiol. 2023;23(1):361. doi: 10.1186/s12871-023-02328-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nachouki M., Mohamed E.A., Mehdi R., Abou Naaj M. Student course grade prediction using the random forest algorithm:Analysis of predictors’ importance. Trends Neurosci Educ. 2023;33 doi: 10.1016/j.tine.2023.100214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J., Xu Y., Liu L., et al. Comparison of LASSO and random forest models for predicting the risk of premature coronary artery disease. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23(1):297. doi: 10.1186/s12911-023-02407-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kang J., Choi Y.J., Kim I.K., et al. LASSO-based machine learning algorithm for prediction of lymph node metastasis in T1 colorectal cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2021;53(3):773–783. doi: 10.4143/crt.2020.974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou H., Xin Y., Li S. A diabetes prediction model based on Boruta feature selection and ensemble learning. BMC Bioinf. 2023;24(1):224. doi: 10.1186/s12859-023-05300-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Y., Zhang Q., Yang Q., Yao M., Xu F., Chen W. Screening of gene expression markers for corona virus disease 2019 through Boruta_MCFS feature selection. Front Public Health. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2022.901602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moore A., Bell M. XGBoost, a novel explainable AI technique, in the prediction of myocardial infarction: a UK biobank cohort study. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2022;16 doi: 10.1177/11795468221133611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley R.D., Snell K.I., Ensor J., et al. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: PART II - binary and time-to-event outcomes. Stat Med. 2019;38(7):1276–1296. doi: 10.1002/sim.7992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X., Ji X. Sample size estimation in clinical research: from randomized controlled trials to observational studies. Chest. 2020;158(1S):S12–S20. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rudin C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat Mach Intell. 2019;1:206–215. doi: 10.1038/s42256-019-0048-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunter D.J., Holmes C. Where medical statistics meets artificial intelligence. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1211–1219. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2212850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greener J.G., Kandathil S.M., Moffat L., Jones D.T. A guide to machine learning for biologists. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022;23(1):40–55. doi: 10.1038/s41580-021-00407-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y., Su Y., Liu Y. Prognosis prediction of paraquat poisoning with Lasso-Logistic regression. Occup Health Emerg Rescue. 2022;40(3):259–264. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hamidi F., Gilani N., Arabi Belaghi R., et al. Identifying potential circulating miRNA biomarkers for the diagnosis and prediction of ovarian cancer using machine-learning approach: application of Boruta. Front Digit Health. 2023;5 doi: 10.3389/fdgth.2023.1187578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guan X., Du Y., Ma R., et al. Construction of the XGBoost model for early lung cancer prediction based on metabolic indices. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2023;23(1):107. doi: 10.1186/s12911-023-02171-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ota R., Yamashita F. Application of machine learning techniques to the analysis and prediction of drug pharmacokinetics. J Control Release. 2022;352:961–969. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2022.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou S.N., Jv D.W., Meng X.F., et al. Feasibility of machine learning-based modeling and prediction using multiple centers data to assess intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma outcomes. Ann Med. 2023;55(1):215–223. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2022.2160008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dubovitskaya A., Baig F., Xu Z., et al. ACTION-EHR: patient-centric blockchain-based electronic health record data management for cancer care. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8) doi: 10.2196/13598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parikh R.B., Obermeyer Z., Navathe A.S. Regulation of predictive analytics in medicine. Science. 2019;363:810–812. doi: 10.1126/science.aaw0029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Adali T.L., Calhoun V.D. Reproducibility and replicability in neuroimaging data analysis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2022;35:475–481. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000001081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu Yanke, Lin Jian, Muto Chieko, et al. Assessment of the utility of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic model for prediction of pharmacokinetics in Chinese and Japanese populations. Int J Med Sci. 2021;18(16):3718–3727. doi: 10.7150/ijms.65040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kitson S.J., Crosbie E.J., Evans D.G., et al. Predicting risk of endometrial cancer in asymptomatic women (PRECISION): model development and external validation. BJOG. 2024;131(7):996–1005. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.17729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Ron J., Fried E.I., Epskamp S. Psychological networks in clinical populations: investigating the consequences of Berkson’s bias. Psychol Med. 2021;51(1):168–176. doi: 10.1017/S0033291719003209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Laliberté V., Giguère C.E., Potvin S., Lesage A., Signature Consortium Berkson’s bias in biobank sampling in a specialised mental health care setting: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-035088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]