Abstract

Patients with chronic limb threatening ischemia are at high risk for cardiovascular events, mortality, and adverse limb events. A 62-year-old man with diabetes and peripheral artery disease presented with a new foot ulcer with suspicion of infection. Leveraging evidence-based practices, a multidisciplinary team conducted a prompt and thorough evaluation. This collaborative approach facilitated comprehensive medical therapy and interventions for optimal limb outcomes and secondary prevention. The coexistence of diabetes, infection, and ischemia significantly augments the complexity of chronic limb threatening ischemia management. Addressing each of these components in concert with recent clinical practice guidelines and randomized trials can promote optimal outcomes.

Key Words: CLTI, multidisciplinary team, lipid, PAD, rivaroxaban, WIfI

Graphical Abstract

History of Presentation

A 62-year-old man with diabetes and prior right lower extremity revascularization for chronic limb threatening ischemia (CLTI) was referred for evaluation of left first toe discoloration and pain. Ten days before presentation, he noticed left calf pain at rest and black discoloration of his left first toe, with skin redness and tenderness spreading to the foot dorsum. Associated symptoms included chills and sweats, but not documented fever, 2 days before presentation. There was no history of trauma, atrial fibrillation, left ventricular thrombus, or abdominal aortic aneurysm. He was hemodynamically stable and afebrile with no acute distress. His blood pressure was 126/67 mm Hg and heart rate was 91 beats/min. On exam, his heart rhythm was regular with no murmurs. He had 2+ femoral pulses bilaterally, but only right palpable popliteal and dorsalis pedis pulses. Left dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial Doppler signals were monophasic. The left great toenail appeared slightly avulsed, and there was dark discoloration at the nail bed with purulent discharge. The foot dorsum was erythematous, tracking up the shin.

Take-Home Messages

-

•

Key aspects in assessing patients with CLTI include determining the degree of ischemia, evaluating the presence of infection, managing hyperglycemia, and addressing cardiovascular risk factor management.

-

•

A multidisciplinary approach to address all these aspects in CLTI management is essential to improve cardiovascular and limb outcomes.

Past Medical History

He was a former smoker with a 15-year history of diabetes. He had a recent diagnosis of peripheral artery disease (PAD), with right leg CLTI, requiring intervention. His medical treatment included daily aspirin 81 mg, atorvastatin 40 mg, glipizide, metformin, metoprolol succinate, and lisinopril. Statin therapy was recently started with PAD diagnosis.

Differential Diagnosis

This patient with diabetes and known PAD presented with new left leg rest pain and ulcer with signs of infection. The etiology and contributing factors of the ulcer included ischemia, diabetes, and infection. A diagnostic plan was developed to address the presence and severity of each component and guide a therapeutic strategy.

Investigation

The patient was admitted to expedite management. For evaluation of ischemia, vascular studies showed left ankle brachial index of 1.2, toe pressure of 48 mm Hg, and moderately dampened pulse volume recording waveforms (Figure 1). Adequate great saphenous vein conduit was not demonstrated on vein mapping. Computed tomography angiography showed a left mid superficial femoral artery (SFA) occlusion with above-knee popliteal reconstitution, and patent tibial and peroneal arteries. Regarding infection, the white blood cell count was 10.1 109/L, C-reactive protein was 142 mg/L, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 37 mm/h. An x-ray demonstrated soft tissue forefoot swelling without osteomyelitis. However, magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated acute osteomyelitis of the first left toe. Blood glucose was 327 mg/dL, HbA1C was 9.8 %, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol was 113 mg/dL. Interventional cardiology, infectious disease, wound care, and endocrinology were consulted.

Figure 1.

Physiological Vascular Test at Presentation

ABI = ankle brachial index; PPG = photoplethysmography; PVR = pressure volume recording.

Management

A comprehensive treatment plan was constructed. Revascularization with an endovascular approach was pursued given technical feasibility and lack of great saphenous vein conduit. The SFA occlusion was successfully crossed retrograde from distal SFA access and treated with nitinol-caged and drug-coated balloon angioplasty (Figure 2). His below-knee arterial disease did not appear clinically significant with 50% focal anterior tibial stenosis. Small vessel disease in the foot was seen. Following intervention, the patient was treated with aspirin, clopidogrel, high-intensity statin, and twice-daily 2.5 mg rivaroxaban with a plan to discontinue clopidogrel 30 days following revascularization.

Figure 2.

Left Leg Angioplasty

The patient’s angioplasty on day 3 from presentation. (A) Occluded mid SFA on anterograde angiography. (B) Retrograde angiography of distal SFA (distal SFA access). (C) Left SFA is patent with <10% residual stenosis following angioplasty using nitinol and drug-coated balloons. ∗SFA occlusion. SFA = superficial femoral artery.

Bone biopsy was deferred given concerns of inadequate wound healing due to small vessel disease and lack of sepsis. An empiric 6-week course of antibiotics was started with intravenous daptomycin and ceftriaxone, and oral metronidazole. Insulin treatment was initiated for hyperglycemia. The patient was discharged with multidisciplinary follow-up. Vascular testing for patency and cardiovascular risk factor management was planned with vascular medicine. The wound clinic was considered instrumental to the follow-up plan as was endocrinology to manage diabetes. Infectious disease aimed to oversee infection control Finally, a case manager was assigned to facilitate the coordination of the team (Figures 3 and 4).

Figure 3.

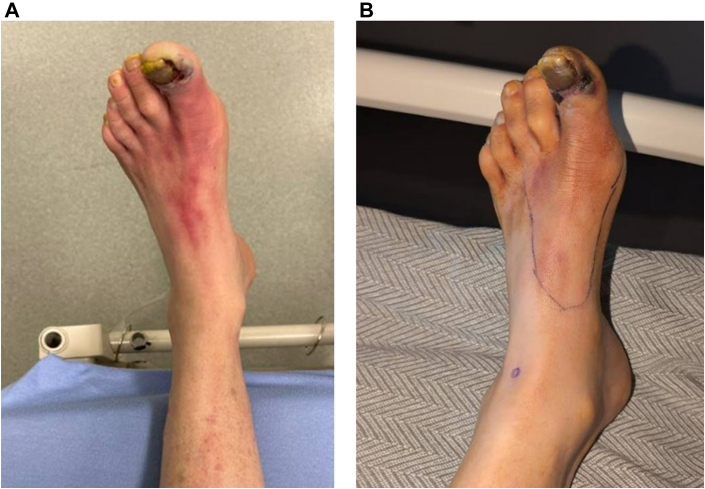

Patient’s Left Foot at Presentation and on Discharge

Patient’s left foot at presentation (A). Left foot with reduced erythema following 5 days of antibiotic therapy and 1 day from revascularization (B).

Figure 4.

CLTI Treatment Goals and Components of Care

CLTI = chronic limb threatening ischemia.

Discussion

CLTI poses a substantial clinical challenge, with 1-year mortality or major amputation rates of 22%.1 To avoid these adverse outcomes, multidisciplinary management is required.

The wound, ischemia, and foot infection (WIfI) classification combines prognostic variables such as wound extent, degree of ischemia, and the presence of infection into 4 stages, corresponding with projected 1-year amputation risk and benefit from revascularization.2 This patint’s WIfI score indicated high amputation risk and expected benefit despite lower calculated grade of ischemia (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Patient’s WIfI Classification at Presentation

Patient’s WIfI grading and stage. (A) Wound grade 2, ischemia grade 1, and foot infection grade 2 are combined to high-risk clinical stage that reflects high risk of amputation (B) and high likelihood of benefit from revascularization (C). H = high risk; L = low risk; M = moderate risk; SBP = systolic blood pressure; SIRS = systemic inflammatory response syndrome; TcPO2 = transcutaneous oxygen pressure; TP = toe pressure; VL = very low risk; WIfI = wound, ischemia, and foot infection; other abbreviation as in Figure 1. ◯ = patient’s grade/stage. (B) Reproduced with permission from Elsevier.2

In patients with CLTI, revascularization is typically pursued to restore blood flow to the affected limb, thus alleviating ischemia and promoting tissue viability. The optimal revascularization strategy for CLTI continues to be investigated. In the BEST-CLI (Best Endovascular versus Best Surgical Therapy for Patients with Critical Limb Ischemia) trial, there was a 32% relative reduction in death or major adverse limb event in 1,434 patients with CLTI caused by infrainguinal PAD, who had an adequate venous conduit randomized to surgical revascularization vs an endovascular approach.3 However, the BASIL-2 (Responses to the Main Critiques of the Bypass Versus Angioplasty in Severe Ischemia of the Leg) trial found a 35% increase in major amputation or death in the surgery group compared with the endovascular arm in patients with CLTI caused by below-knee PAD with or without more proximal infrainguinal disease.4 The 2024 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association PAD guidelines do not endorse a single revascularization strategy but recognize several considerations to direct management decisions, such as the presence of suitable autologous vein conduit, PAD anatomy, and a patient’s comorbidities and preference.1 In the presented case, the revascularization approach was considered during his evaluation, with the assessment of his arterial disease anatomy and the presence of a suitable conduit vein on vein mapping.

Diabetes is associated with higher rates of amputation, CLTI, and mortality in patients with PAD. Similarly, PAD significantly worsens the prognosis in patients with diabetes-related foot ulcer.5 In considering management of patients with PAD and diabetes, both glucagon-like peptide (GLP)-1 agonist and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor medication classes were shown to reduce major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in this population.1 Furthermore, a reduction in amputations was suggested with liraglutide (a GLP-1 receptor agonist) in patients with type 2 diabetes and high risk of MACEs.6 In this patient, adding a GLP-1 agonist and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, with close endocrinology follow-up, was planned.

Active infection presents another barrier to achieve optimal limb outcomes in CLTI, and infectious disease involvement in the diagnosis and treatment of soft tissue infection and osteomyelitis is imperative.5 Follow-up for the assessment of infection severity and the need for minor amputation as part of infection control was planned in this case.5

For patients with severe atherothrombotic disease, such as CLTI, optimal medical therapy and cardiovascular risk factor modification can reduce future limb and cardiovascular events.7, 8, 9 The VOYAGER PAD (Vascular Outcomes Study of ASA Along With Rivaroxaban in Endovascular or Surgical Limb Revascularization for Peripheral Artery Disease) trial showed a reduction in the primary outcome composite of acute limb ischemia, major vascular amputation, myocardial infarction, or ischemic stroke, with rivaroxaban 2.5 mg twice daily vs placebo on a background of aspirin in 6,564 patients with symptomatic PAD following revascularization.9 Current guidelines endorse this approach,1 which was implemented in this case.

Lipid-lowering therapy has also been shown to decrease MACE and limb outcomes in PAD.1 For example, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors have yielded promising results. The FOURIER (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Patients With Elevated Risk) trial demonstrated 27% lower MACE and 37% fewer limb events with evolocumab vs placebo in 3,642 patients with PAD.7 Similarly, in the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES (ODYSSEY Outcomes: Evaluation of Cardiovascular Outcomes After an Acute Coronary Syndrome During Treatment With Alirocumab) trial, alirocumab demonstrated a numerically greater absolute risk reduction in MACE vs placebo among those with polyvascular disease.8 Achieving guideline-recommended low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goals of <70 mg/dL often requires combination therapy.10 Ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitor should be considered in this patient, to optimize risk reduction.1

Follow-up

Eight weeks following discharge, first left toe amputation was completed given evidence of ongoing osteomyelitis. Tisue cultures were initially negative but later culture from debridement grew methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and antibiotic management was changed according to culture results and sensitivities. Following amputation, and with comprehensive medical treatment and follow-up, the patient showed adequate wound healing and improved risk-factors control for secondary prevention. A functional limb had been preserved.

Conclusions

This case underscores the critical role of a multidisciplinary team in CLTI management (Figure 4). Revascularization, infection control, diabetes optimization, and pragmatic aggressive risk factor modification are essential components for optimal limb outcomes and preventing future MACEs and major adverse limb events.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

The authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

References

- 1.Gornik H.L., Aronow H.D., Goodney P.P., et al. 2024 ACC/AHA/AACVPR/APMA/ABC/SCAI/SVM/SVN/SVS/SIR/VESS guideline for the management of lower extremity peripheral artery disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2024;149(24):e1313–e1410. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills JL Sr, Conte M.S., Armstrong D.G., et al. The Society for Vascular Surgery Lower Extremity Threatened Limb Classification System: risk stratification based on wound, ischemia, and foot infection (WIfI) J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(1):220–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.08.003. e1-210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farber A., Menard M.T., Conte M.S., et al. Surgery or endovascular therapy for chronic limb-threatening ischemia. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2305–2316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2207899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradbury A.W., Moakes C.A., Popplewell M., et al. A vein bypass first versus a best endovascular treatment first revascularisation strategy for patients with chronic limb threatening ischaemia who required an infra-popliteal, with or without an additional more proximal infra-inguinal revascularisation procedure to restore limb perfusion (BASIL-2): an open-label, randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10390):1798–1809. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00462-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Senneville E., Albalawi Z., van Asten S.A., et al. IWGDF/IDSA guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diabetes-related foot infections (IWGDF/IDSA 2023) Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2024;40(3) doi: 10.1002/dmrr.3687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhatariya K., Bain S.C., Buse J.B., et al. The impact of liraglutide on diabetes-related foot ulceration and associated complications in patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events: results from the LEADER Trial. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(10):2229–2235. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonaca M.P., Nault P., Giugliano R.P., et al. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering with evolocumab and outcomes in patients with peripheral artery disease: insights from the FOURIER Trial (Further Cardiovascular Outcomes Research With PCSK9 Inhibition in Subjects With Elevated Risk) Circulation. 2018;137(4):338–350. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jukema J.W., Szarek M., Zijlstra L.E., et al. Alirocumab in patients with polyvascular disease and recent acute coronary syndrome: ODYSSEY OUTCOMES trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(9):1167–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonaca M.P., Bauersachs R.M., Anand S.S., et al. Rivaroxaban in peripheral artery disease after revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):1994–2004. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess C.N., Nehler M.R., Daffron A., et al. Pragmatic implementation science to assess lipid optimization in peripheral artery disease: primary results of the OPTIMIZE PAD-1 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81(8):2105. [Google Scholar]