Abstract

Objective

We aimed to assess the prevalence of clonal haematopoiesis (CH) in patients with giant cell arteritis (GCA) compared with controls and individuals with other autoimmune diseases (AIDs) and to identify high-risk clinical/genetic profiles that could influence disease outcomes.

Methods

In a prospective observational study at three hospitals, we included 49 patients diagnosed with GCA, 48 patients with other AIDs and 27 control participants. We used next-generation sequencing to detect clonal haematopoiesis (CH) among them.

Results

CH was detected in 55.1% of patients with GCA, 59.3% of controls and 18.8% of patients with other AIDs. The most commonly mutated genes in GCA and control groups were DNMT3A and TET2. No significant differences in CH prevalence were found between patients with GCA and controls or other AID when adjusted for age and sex. Cluster analysis revealed two distinct groups within the patients with GCA, one of which displayed a higher prevalence of TET2 and JAK2 variants, and was associated with worse prognosis.

Conclusions

CH is prevalent among patients with GCA but does not differ significantly from controls or other autoimmune conditions. However, specific genetic profiles, particularly mutations in TET2 and JAK2, are associated with a higher risk cluster within the GCA cohort. This observation highlights the interest of detecting CH in patients with GCA in both routine practice and clinical trials for better risk stratification. Further prospective studies are needed to determine if management tailored to the genetic profile would improve outcomes.

Keywords: giant cell arteritis, vasculitis, epidemiology

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This study confirms the high prevalence of CH in patients with GCA, similar to control groups, and finds no significant difference in CH incidence between patients with GCA and those with other autoimmune diseases when adjusted for age and sex.

We found a specific genetic profile marked by TET2 and JAK2 mutations defining a high-risk cluster within the GCA cohort, which is associated with more frequent relapse.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The identification of genetic markers such as TET2 and JAK2 mutations in patients with GCA suggests a need for routine screening for CH in this patient group to improve risk stratification and potentially guide personalised treatment approaches.

Further research is needed to explore how management tailored to genetic risk profiles could enhance outcomes for patients with GCA, particularly those at high risk of relapse or severe complications.

Introduction

Giant cell arteritis (GCA) is a systemic granulomatous vasculitis affecting the aorta and its main branches, including carotid and vertebral arteries, among individuals aged 50 years and older.1 2 The natural course of the disease is marked by relapse and ophthalmic and cardiovascular complications, notably stroke and aortic events,3,6 necessitating early treatment with glucocorticoids (GC). The pathophysiology of the disease is still unclear but involves inflammatory infiltrates within vessel wall layers leading to vascular remodelling of arteries and systemic inflammation mostly driven by interleukin (IL)-6.7 Circulating monocytes might be key contributors to the inflammatory process8 by engaging with activated endothelial cells within the vasa vasorum and neovessels and expressing matrix metalloprotease-9, which degrades the basement membrane to open a gateway for incoming T cells and macrophages.9,11 The risk stratification remains a challenge among patients with GCA in the absence of well-documented predictive biomarkers. On the other hand, clonal haematopoiesis (CH) is an age-related phenomenon consisting of the expansion of somatic mutations in haematopoietic stem cells and has been linked with systemic inflammation, cardiovascular events and higher all-cause mortality among healthy individuals.12,14 Recent work showed that individuals with CH were at significantly higher risk of developing GCA, with TET2 mutations conferring an increasing risk of vision loss.15 Another study suggested that DNMT3A mutations might be associated with more frequent relapse among patients with GCA.16

In this study, we aimed to assess the prevalence of CH among patients with GCA compared with controls and other autoimmune diseases (AIDs) and explore, through cluster analysis, whether CH presence would allow us to identify high-risk clusters.

Materials and methods

Data collection and study population

We conducted a prospective observational study including 97 patients aged over 18 years at the three centres (Saint Antoine, Melun and Montfermeil hospitals), with a diagnosis of GCA or another AID among the following: Behçet disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), Takayasu’s arteritis, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis. Patients were diagnosed with GCA if they had at least six points from the 2022 American College of Rheumatology GCA classification.17 Patients were included between April 2021 and October 2022. None of the patients had a diagnosis of haematological malignancy at the beginning of the study. A control group of 27 patients with available DNA samples was created. Patients in the control group were hospitalised for reasons unrelated to any of the mentioned conditions and none had any history of underlying haematological malignancy. Baseline characteristics, including demographic, clinical, biological, radiological and outcome data were extracted from electronic medical records using a standardised data collection. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guidelines.18

DNA sequencing

Genomic DNA aberrations were identified through next-generation sequencing (NGS) analysis. Sample preparation and sequencing were conducted at the Department of Biology and Medical Pathology at the Gustave Roussy Institute, situated in Val-de-Marne, Île-de-France. DNA libraries based on Haloplex (Agilent) technology were prepared following the manufacturer’s protocols and sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq and NextSeq sequencing systems with an average sequencing depth of at least 500x. Two pipelines using machine learning algorithms to analyse variants from raw NGS data were employed: the in-house GRIO-DX and SOPHIA DDM (SophiaGenetics) softwares. The custom NGS panel comprised 74 genes, including 40 complete coding sequences and 34 targeted sequences. This panel encompassed genes encoding factors involved in molecular pathways commonly mutated in haematological malignancies, such as DNA methylation (DNMT3A, IDH1, IDH2, TET2), haematopoietic development (RUNX1, ETV6, GATA3, IKZF1), histone modification (SUZ12, EED, EZH2, SETD2, EP300) and cytokine receptor and RAS signalling (NRAS, KRAS, BRAF, NF1, SH2B3, PTPN11). The threshold for detecting allelic frequency variation was set at 2%.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are described as medians (IQRs), and binary variables are expressed as numbers (proportions). Quantitative and binary variables were compared using Kruskal-Wallis and Fisher’s exact tests, respectively. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regressions were used to analyse the association between GCA diagnosis and CH prevalence versus control individuals and other AIDs. Adjusted variable (age and sex) was chosen a priori according to their potential impact on CH prevalence. All logistic regression model assumptions were met adequately. No interaction was found between variables. Cumulative incidence curves for relapse or GC-dependency were generated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Relapse was defined as the reappearance of GCA symptoms or the appearance of new GCA symptoms, with a concomitant increase in inflammatory markers (defined as C reactive protein (CRP) >10 mg/L), requiring treatment adjustment. GC-dependence was defined as the presence of a daily dose of oral prednisone >20 mg/day (or 0.30 mg/kg) after 6 months or a daily dose of oral prednisone >10 mg/day (or 0.20 mg/kg) after 12 months or a treatment maintained >24 months because of a relapsing disease course. We used factor analysis of mixed data (FAMD) handling missing data with multiple imputations through the ‘missMDA’ package V.1.18.19 Then, we performed hierarchical cluster analysis based on FAMD coordinates using Euclidean distance. We identified an optimal cluster number of 2 through multiple methods detailed in the online supplemental methods 1 and 2. Two-sided testing was used, with p<0.05 considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using R software V.4.2.2 for Mac (Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Study population

We included 49 patients with GCA, 27 controls and 48 patients with other AID, including 24 patients (50%) with SLE, 10 (20.8%) patients with Behçet disease, five patients (10.4%) with Takayasu’s arteritis and nine patients (18.8%) with ANCA-associated vasculitis.

Patients with GCA were composed of 16 male patients (32.7%), with a median age of 76 years (IQR 73–84 years). There was no significant difference between GCA and controls patients regarding sex (12 (44.4%) male patients, p=0.33) and age (78 years (IQR 71–85 years), p=0.94). Among them, 24 (49.0%) patients had a positive temporal artery biopsy (TAB). In contrast, patients with another AID were younger (44 years (IQR 38–58 years), p<0.001) and tended to be less frequently male (n=8, 16.7%, p=0.10). We did not find any difference regarding haemoglobin level, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) and absolute monocyte count between patients with GCA and control patients (table 1), whereas patients with other AID had less ANC (3.46 G/L IQR (1.97, 5.69) vs 4.62 G/L IQR (3.80, 7.16), p=0.03).

Table 1. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients according to their status.

| Giant cell arteritis (n=49) | Control (n=27) | P value* | AID (n=48) | P value† | P value global | |

| Age (median (IQR)) | 76 (73, 84) | 78 (71, 85) | 0.94 | 44 (38, 58) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 16 (32.7) | 12 (44.4) | 0.33 | 8 (16.7) | 0.10 | 0.027 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 19 (55.9) | 20 (74.1) | 0.18 | 18 (40.0) | 0.18 | 0.018 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 15 (44.1) | 13 (48.1) | 0.80 | 4 (8.9) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 5 (14.7) | 5 (18.5) | 0.74 | 3 (6.7) | 0.28 | 0.27 |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | 7 (20.6) | 6 (22.2) | >0.99 | 7 (15.6) | 0.57 | 0.74 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (median (IQR)) | 23.30 (20.00, 25.00) | 25.00 (20.00, 26.60) | 0.41 | 25.00 (21.00, 27.00) | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 3 (8.8) | 1 (3.7) | 0.62 | 3 (6.7) | >0.99 | 0.89 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 4 (11.8) | 2 (7.4) | 0.69 | 4 (8.9) | 0.72 | 0.84 |

| History of cancer, n (%) | 8 (23.5) | 3 (11.1) | 0.32 | 6 (13.6) | 0.37 | 0.44 |

| Haemoglobin (g/L) (median (IQR)) | 119.0 (105.0, 124.0) | 120.0 (110.0, 120.0) | 0.55 | 120.0 (109.0, 130.0) | 0.69 | 0.83 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (G/L) (median (IQR)) | 4.62 (3.80, 7.16) | 4.91 (2.60, 6.20) | 0.43 | 3.46 (1.97, 5.69) | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| Absolute monocytes count (G/L) (median (IQR)) | 0.51 (0.20, 0.92) | 0.63 (0.50, 0.76) | 0.37 | 0.43 (0.31, 0.56) | 0.33 | 0.02 |

| Platelet (G/L) (median (IQR)) | 339 (246, 407) | 258 (181, 292) | 0.01 | 245 (196, 309) | 0.003 | 0.006 |

| CRP (mg/L) (median (IQR)) | 30.00 (14.00, 88.00) | 5.00 (4.00, 39.00) | <0.05 | 4.00 (3.00, 9.00) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) (median (IQR)) | 71.00 (64.00, 86.00) | 79.50 (62.75, 97.00) | 0.41 | 63.50 (55.25, 79.75) | 0.23 | 0.15 |

| CH, n (%) | 27 (55.1) | 16 (59.3) | 0.81 | 9 (18.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| VAF (%) (median (IQR)) if present | 9.00 (4.00, 16.00) | 11.00 (7.00, 21.75) | 0.50 | 5.00 (3.00, 6.00) | 0.05 | 0.048 |

| Number of variants if present (median (IQR)) | 1.00 (0.00, 2.00) | 1.00 (0.00, 1.50) | 0.89 | 0.00(0.00, 0.00) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| DNMT3A, n (%) | 9 (18.4) | 9 (33.3) | 0.17 | 1 (2.1) | 0.016 | <0.001 |

| TET2, n (%) | 6 (12.2) | 4 (14.8) | 0.74 | 0 (0.0) | 0.027 | 0.011 |

| ASXL1, n (%) | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.55 | 1 (2.1) | 0.62 | 0.54 |

| Spliceosome‡, n (%) | 5 (10.2) | 2 (7.4) | >0.99 | 0 (0.0) | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| TP53, n (%) | 3 (6.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.55 | 0 (0.0) | 0.24 | 0.23 |

| JAK2, n (%) | 3 (6.1) | 2 (7.4) | >0.99 | 0 (0.0) | 0.24 | 0.16 |

| Other variants, n (%) | 16 (32.7) | 8 (29.6) | 1.000 | 7 (14.6) | 0.06 | 0.087 |

GCA versus Ccontrol.

GCA versus others AIDs.

The category of spliceosome variants includes SF3B1, SRSF2.

AID, autoimmune disease; CH, clonal haematopoiesis; CRP, C reactive protein; GCA, giant cell arteritis; VAF, variant allele frequency

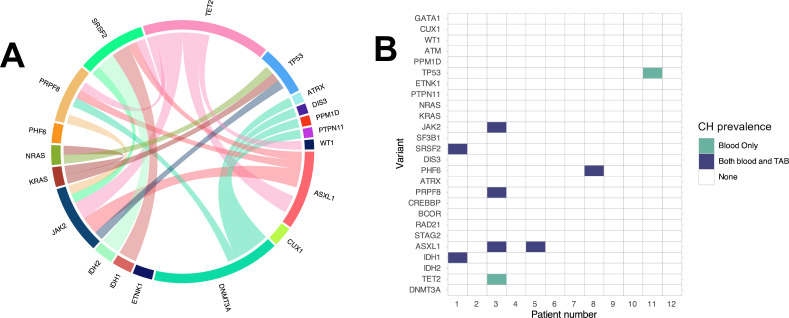

Clonal landscape

Clonal haematopoiesis (CH) incidence in GCA, control individuals and other patients with AID were 55.1% (27/49), 59.3% (16/27) and 18.8% (9/48), respectively. Among GCA and control patients, the most frequently mutated genes were DNMT3A (n=9, 18.4% in GCA, n=9, 33.3% in control) and TET2 (n=6, 12.2% in GCA, n=4, 14.8% in control). Regarding patients with another AID, we did not find any TET2 variant. Only one (2.1%) patient had a DNMT3A variant, the most frequently mutated gene being PRPF8 (figure 1A, table 1 and online supplemental table 1), a gene involved in pre-mRNA processing. We did not find any difference regarding the variant allele frequency (VAF) between GCA and control individuals (median: 9% (IQR 4–16) vs 11% (IQR 7–21.75), p=0.50), but patients with GCA tended to have higher VAF than other patients with AID (median: 9% (IQR 4–16) vs 5% (IQR 3–6), p=0.05), as shown in figure 1B. Among the three groups, 14 (28.6%) patients had more than one mutation in the GCA group (figure 1D) vs 7 (25.9%) among control individuals, whereas none of the other patients with AID had more than one mutation (figure 1C).

Figure 1. Sequencing analysis of GCA, AID and control individuals. (A) Number of patients stratified by the number of detected mutations among GCA, AID and control individuals. (B) Histogram of VAF among GCA, AID and control individuals. (C) Number of variants among GCA, AID and control individuals. (D) Forest plot of the ORs for GCA diagnosis and CH prevalence versus AID or control individuals. Adjustment covariates included age and sex. Regarding the comparison between GCA and AID, no individual variant comparison was performed due to the low number of events. Regarding the comparison between GCA and control individuals, variant analyses were not adjusted due to the low number of events. The category of spliceosome variants includes SF3B1, SRSF2 and PRPF8. AID, autoimmune disease; CH, clonal haematopoiesis; GCA, giant cell arteritis; VAF, variant allele frequency.

Patients with CH and GCA

CH prevalence was not associated with GCA, compared with other AID adjusted on the age and sex (adjusted OR 1.50 (95% CI 0.35 to 6.46), p=0.58) nor compared with controls (adjusted OR 0.87 (95% CI 0.31 to 2.42), p=0.79), neither was any variant (more details in figure 1D). Among the 49 patients with GCA, we did not find any significant difference between the 27 patients with CH and 22 patients without CH, except for haemoglobin, which was lower among patients with CH (median: 11.1 g/dL (IQR 10.4, 12.0) vs 12.1 mg/dL (IQR 11.6, 13.0), p=0.04). More information is available in online supplemental table 2 and figure 2A.

Figure 2. Clonal landscape of patient with GCA in the blood and in TAB. (A) Circular plot showing co-occurring variant pairs among patients with GCA. (B) Co-occurrence matrix of CH variants in blood and TAB among the 12 patients with GCA with available samples, where individuals are represented by one column. No patient had CH in TAB only. CH, clonal haematopoiesis; GCA, giant cell arteritis; TAB, temporal artery biopsy.

TAB samples were available for 12 patients with GCA. Among them, five (41.7%) patients had CH in the blood, four (80%) of whom also had CH in TAB. Regarding patients with CH in both blood and TAB, all mutations found in the blood were found in TAB except for one patient who was TET2, JAK2, PRPF8 and ASXL1 positive in the blood, but only lacked TET2 mutation in TAB that was positive in the blood (more details in figure 2B). Among patients who were CH positive in both blood and TAB, the median VAF was 6.0% (IQR 4.8, 12.8) in the blood and 4.50% (IQR 4.0, 6.8) in TAB. We did not find any differences in baseline characteristics between patients with CH positive in TAB only versus patients with CH positive in blood only.

GCA cluster analysis

Based on variables listed in online supplemental methods 1, we performed a hierarchical cluster analysis on the FAMD coordinates results of patients with GCA to obtain the dendrogram as shown in figure 3A. The optimal number of clusters was two, according to multiple methods shown in online supplemental methods 2: cluster 1 (n=31, 63.3%) and cluster 2 (n=18, 36.7%). Figure 3B shows the factorial map of individuals according to the three clusters obtained.

Figure 3. Cluster analysis and survival analysis among patients with GCA. (A) The hierarchical clustering on principal components analysis of patients with GCA revealed two clusters (variables included are listed in online supplemental material). (B) Factor map showing the individuals used to generate the dendrogram. (C) Kaplan-Meier survival curves of the cumulative incidence of relapse or GC-dependency by GCA cluster p value is provided using log-rank test. GC, glucocorticoids; GCA, giant cell arteritis.

Patients from cluster 1 had less frequent hypertension (n=7, 36.8% vs n=12, 80.0% in cluster 2, p=0.017), less frequent dyslipidaemia (n=5, 26.3% vs n=10, 66.7% in cluster 2, p=0.036), less frequently diabetes mellitus (n=0, 0.0% vs n=5, 33.3% in cluster 2, p=0.011) and had a significantly lower body mass index (median: 21.7 (IQR 19.9, 24.0) vs 25.0 (IQR 23.0, 25.0) in cluster 2, p=0.045). Patients from cluster 2 had also a more frequent history of stroke compared with patients from cluster 1 (n=4, 26.7% vs n=0, 0.0%, respectively, p=0.029) and needed more frequent biotherapy among follow-up (n=13, 81.2% vs n=2, 8.7%, p<0.001). More details are available in table 2.

Table 2. Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with GCA according to cluster identification.

| Cluster 1 (n=31) | Cluster 2 (n=18) | P value | |

| Age (median (IQR)) | 77 (74, 85) | 75 (72, 81) | 0.17 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 11 (35.5) | 5 (27.8) | 0.75 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 7 (36.8) | 12 (80.0) | 0.017 |

| Dyslipidaemia, n (%) | 5 (26.3) | 10 (66.7) | 0.036 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (33.3) | 0.011 |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 6 (40.0) | 0.028 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) (median (IQR)) | 21.65 (19.85, 24.00) | 25.00 (23.00, 25.08) | 0.045 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (20.0) | 0.08 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (26.7) | 0.029 |

| History of cancer, n (%) | 6 (31.6) | 2 (13.3) | 0.26 |

| Associated polymyalgia rheumatica, n (%) | 10 (43.5) | 14 (87.5) | 0.008 |

| Weight loss, n (%) | 5 (21.7) | 5 (31.2) | 0.71 |

| Fever, n (%) | 3 (13.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0.12 |

| Visual loss, n (%) | 8 (30.8) | 3 (17.6) | 0.48 |

| Aortitis, n (%) | 3 (13.0) | 6 (37.5) | 0.12 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) (median (IQR)) | 11.55 (10.49, 12.25) | 12.00 (10.50, 13.00) | 0.77 |

| Absolute neutrophil count (G/L) (median (IQR)) | 4.10 (3.70, 6.00) | 5.50 (4.55, 7.39) | 0.13 |

| Absolute monocytes count (G/L) (median (IQR)) | 0.25 (0.12, 0.93) | 0.61 (0.43, 0.79) | 0.14 |

| Platelet (G/L) (median (IQR)) | 367 (233, 406) | 301 (251, 414) | 0.90 |

| CRP (mg/L) (median (IQR)) | 20.00 (11.93, 83.50) | 40.00 (20.00, 95.00) | 0.33 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) (median (IQR)) | 68.00 (58.75, 81.00) | 73.00 (71.00, 86.00) | 0.13 |

| CH, n (%) | 19 (61.3) | 8 (44.4) | 0.37 |

| VAF (%) if present (median (IQR)) | 11.00 (4.00, 16.00) | 7.00 (4.75, 13.75) | 0.85 |

| Numbers or variant if present (median (IQR)) | 1.0 (0.0, 2.0) | 0.0 (0.0, 1.8) | 0.54 |

| DNMT3A, n (%) | 8 (25.8) | 1 (5.6) | 0.13 |

| TET2, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 5 (27.8) | 0.02 |

| ASXL1, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 2 (11.1) | 0.55 |

| SRSF2, n (%) | 4 (12.9) | 1 (5.6) | 0.64 |

| PRPF8, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (5.6) | >0.99 |

| JAK2, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (16.7) | 0.044 |

| IDH1, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.53 |

| IDH2, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.53 |

| KRAS, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| NRAS, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| PTPN11, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| ETNK1, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| TP53, n (%) | 2 (6.5) | 1 (5.6) | >0.99 |

| PPM1D, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| ATRX, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| PHF6, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | 0.37 |

| DIS3, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | 0.37 |

| WT1, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.6) | 0.37 |

| CUX1, n (%) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

| Corticosteroid, n (%) | 21 (91.3) | 15 (93.8) | >0.99 |

| DMARDs, n (%) | 2 (8.7) | 1 (6.2) | >0.99 |

| Biotherapy, n (%) | 2 (8.7) | 13 (81.2) | <0.001 |

| GC-dependency, n (%) | 1 (4.3) | 7 (43.8) | 0.004 |

| Relapse, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (31.2) | 0.008 |

| Death, n (%) | 1 (4.5) | 0 (0.0) | >0.99 |

CH, clonal haematopoiesis; CRP, C reactive protein; DMARD, disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; GC, glucocorticoids; GCA, giant cell arteritis; VAF, variant allele frequency

No significant difference was found regarding CH prevalence between both clusters (n=19, 61.3% in cluster 1 vs n=8, 44.4% in cluster 2, p=0.37), neither regarding median VAF (11.0% (IQR 4.0, 16.8) in cluster 1 vs 7.0% (IQR 4.75, 13.75), p=0.85). However, patients from cluster 2 had more frequent TET2 (n=5, 27.8% vs n=1, 3.2% in cluster 1, p=0.02) and JAK2 (n=3, 16.7% vs n=0, 0.0% in cluster 1, p=0.044) mutations.

Regarding survival analyses, patients from cluster 2 had significantly higher rates of relapse or need of GC-dependency (1-year relapse or GC-dependency rate: 39.1% (95% CI 8.9; 59.3) in cluster 2 vs 0.0% (95% CI 0.0; 0.0) in cluster 1; log-rank test p<0.001). Cumulative incidence curves are presented in figure 3C.

Discussion

In our study, the prevalence of CH among patients with GCA was not different from that in control individuals or patients with other AIDs, when controlled for age. More specifically, CH presence was not associated with a particular phenotype among patients with GCA. However, we identified two clusters, one of which was associated with TET2 and JAK2 variants and more frequent cardiovascular risk factors and stroke history. Interestingly, patients from this cluster required more frequent use of biotherapy and had a significantly higher risk of relapse and GC-dependency.

Previous authors investigated the relationship between CH and GCA.15 16 20 21A recent study showed an increased incidence of CH among patients with GCA from the UK biobank, adjusted on age, sex and smoking status.15 They also found a CH prevalence of 27.2% in the Massachusetts General Brigham GCA cohort among 114 patients, in line with other studies with a VAF cut-off of 2%.16 20 In our cohort, we found an increased prevalence of CH (55.1%), although our patients were slightly older than those from the previous studies, and CH prevalence did not differ between control and GCA, even adjusted on age. Compared with patients with other AIDs, we found no difference in CH prevalence between patients with GCA and controls when adjusted for age, consistent with the significant association of CH with age. As described in the literature, the most frequently associated mutations in GCA were DNMT3A, TET2 and ASXL1 suggesting the representativeness of our cohort.15 16 Regarding prognosis, CH has been reported to be associated with an increased risk of relapse, mainly due to DNMT3A-defined CH (82% of relapsed patients).16 Patients with GCA with TET2 mutations also tend to present more frequently vision loss (OR 4.33).15

Our study is the first to identify a high-risk profile in terms of relapse and GC-dependency, with increased prevalence of TET2 and JAK2 mutation, although CH prevalence did not differ between our two clusters. DNMT3A was not significantly different between both groups, although high-risk patients even tended to have less DNMT3A mutation (one mutation (5.6%) in the high-risk cluster vs eight mutations (25.8%) in the other group, p=0.13). Those results might suggest that TET2 is involved in the GCA inflammation, whereas DNMT3A might be secondary to the ageing process. Indeed, GCA pathophysiology involves both CD4+ T and myeloid cell pathways. Monocytes from patients with GCA release chemokines that facilitate the migration of monocytes and macrophages through the vascular endothelium, leading to localised inflammation. TET-2 mutation may exacerbate this phenomenon, as TET2-deficient monocytes and macrophages show an increased reaction to inflammatory stimuli, with high production of IL-6 and IL-1β.22,25 However, the causal relationship between GCA and CH remains unclear. The presence of CH, particularly TET2, could either reflect the inflammation or potentially exacerbate it, increasing the risk of relapse. We also found that the presence of CH in TAB at diagnosis was observed in nearly all patients who were CH-positive in the blood, with consistent variants, This suggests that the mutated immune cells were recruited to the temporal artery at diagnosis, as described in the litterature.16 Unfortunately, we were unable to assess their prognostic value due to the limited number of patients with available samples.

Patients with GCA face relapse risk and tend to be at higher cardiovascular risk compared with non-vasculitis patients.26,31 Many mechanisms are involved, including vascular wall inflammation, accelerated atherosclerosis due to chronic inflammation and GC exposure,32,35 leading to a higher risk of strokes and aortic complications.3236,40 Moreover, CH may play a role in the incidence of vascular events in GCA, as increasing evidence highlights the importance of inflammation as a key contributor to cardiovascular disease. Additionally, TET2 has been shown to be associated with various cardiovascular events.14 41 42 In a genomic subanalysis of the Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study trial,43 which showed that blockade of IL-1β using canakinumab reduced the rate of major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with a previous myocardial infarction and residual high-sensitivity CRP level >0.20 mg/dL, TET2 variants were more common than DNMT3A variants among CH-positive individuals. Furthermore, TET2-positive patients experienced fewer major adverse cardiovascular events when treated with canakinumab compared with those without CH.44 Some authors showed that myeloid cells carrying TET2 variants, as opposed to those with DNMT3A variants, exhibited increased IL-1β secretion when exposed to lipopolysaccharide, which could explain this greater event reduction.45 In our study, patients from the high-risk cluster had significantly more history of stroke and tended to have more myocardial infarction, although our conclusions are limited by the low number of events and by the higher prevalence of cardiovascular risk factor among them.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we identified a high-risk profile in patients with GCA with an increased prevalence of TET2 and JAK2 mutations, which are associated with cardiovascular risk factors, strokes and poor outcomes. Our study highlights the importance of detecting CH in patients with GCA, both in routine practice and clinical trials, for better risk stratification. Further research is needed to better determine the cardiovascular prognosis and response to biotherapy in these patients.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the support of the MSD-Avenir Fund, as well as the contributions of Edwige Leclercq and Cyril Gella to this project.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was partially funded by the MSD-Avenir Research Grant (Immuno-clone project).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Cochin Hospital Institutional Review Board (CLEP decision no.: AAA-2021-08040). It was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Participants provided informed consent before taking part in the study.

Patient and public involvement statement: Patients or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of our research.

Contributor Information

Alexis F Guedon, Email: guedonalexis@gmail.com.

Asmaa Ouafdi, Email: asmaa.ouafdi@aphp.fr.

Nabil Belfeki, Email: nabil.belfeki@ghsif.fr.

Azeddine Dellal, Email: azeddine.dellal@ght-gpne.fr.

Nouha Ghriss, Email: nouha.ghriss@ghsif.fr.

Marc Scheen, Email: marc.scheen@hug.ch.

Fadi Haidar, Email: fadi.haidar@hcuge.ch.

Olivier Espitia, Email: Olivier.espitia@chu-nantes.fr.

Jean-Yves Scoazec, Email: jean-yves.scoazec@gustaveroussy.fr.

Olivier Fain, Email: olivier.fain@aphp.Fr.

Christophe Marzac, Email: Christophe.Marzac@gustaveroussy.fr.

Olivier Hermine, Email: olivier.hermine@nck.aphp.fr.

Eric Solary, Email: eric.solary@gustaveroussy.fr.

Julien Rossignol, Email: julien.rossignol@aphp.fr.

Arsène Mekinian, Email: arsene.mekinian@aphp.fr.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. revised International Chapel Hill Consensus Conference Nomenclature of Vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1–11. doi: 10.1002/art.37715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li KJ, Semenov D, Turk M, et al. A meta-analysis of the epidemiology of giant cell arteritis across time and space. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23:82. doi: 10.1186/s13075-021-02450-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ostberg G. Morphological changes in the large arteries in polymyalgia arteritica. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1972;533:135–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agard C, Barrier J-H, Dupas B, et al. Aortic involvement in recent-onset giant cell (temporal) arteritis: a case-control prospective study using helical aortic computed tomodensitometric scan. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:670–6. doi: 10.1002/art.23577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prieto-González S, Arguis P, García-Martínez A, et al. Large vessel involvement in biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis: prospective study in 40 newly diagnosed patients using CT angiography. Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71:1170–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-200865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guédon AF, Froger C, Agard C, et al. Identifying Giant Cell Arteritis patients with higher risk of relapse and vascular events: a cluster analysis. QJM An Int J of Med. 2024 doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcae105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terrades-Garcia N, Cid MC. Pathogenesis of giant-cell arteritis: how targeted therapies are influencing our understanding of the mechanisms involved. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018;57:ii51–62. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kex423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Sleen Y, Wang Q, van der Geest KSM, et al. Involvement of Monocyte Subsets in the Immunopathology of Giant Cell Arteritis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:6553. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-06826-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foell D, Hernández-Rodríguez J, Sánchez M, et al. Early recruitment of phagocytes contributes to the vascular inflammation of giant cell arteritis. J Pathol. 2004;204:311–6. doi: 10.1002/path.1660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cid MC, Cebrián M, Font C, et al. Cell adhesion molecules in the development of inflammatory infiltrates in giant cell arteritis: inflammation-induced angiogenesis as the preferential site of leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:184–94. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200001)43:1<184::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe R, Maeda T, Zhang H, et al. MMP (Matrix Metalloprotease)-9-Producing Monocytes Enable T Cells to Invade the Vessel Wall and Cause Vasculitis. Circ Res. 2018;123:700–15. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaiswal S, Fontanillas P, Flannick J, et al. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2488–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaiswal S, Natarajan P, Silver AJ, et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis and Risk of Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:111–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1701719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaiswal S, Ebert BL. Clonal hematopoiesis in human aging and disease. Science. 2019;366:eaan4673. doi: 10.1126/science.aan4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robinette ML, Weeks LD, Kramer RJ, et al. Association of Somatic TET2 Mutations With Giant Cell Arteritis. Arthritis Rheumatol . 2024;76:438–43. doi: 10.1002/art.42738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, Wells KV, Jones AI, et al. Clonal haematopoiesis across the age spectrum of vasculitis patients with Takayasu’s arteritis, ANCA-associated vasculitis and giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83:508–17. doi: 10.1136/ard-2023-224933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponte C, Grayson PC, Robson JC, et al. 2022 American College of Rheumatology/EULAR classification criteria for giant cell arteritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:1647–53. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. The Lancet. 2007;370:1453–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61602-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Josse J, Husson F. missMDA : A Package for Handling Missing Values in Multivariate Data Analysis. J Stat Soft. 2016;70:1–31. doi: 10.18637/jss.v070.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Papo M, Friedrich C, Delaval L, et al. Myeloproliferative neoplasms and clonal haematopoiesis in patients with giant cell arteritis: a case-control and exploratory study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2022;61:775–80. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keab337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salzbrunn JB, van Zeventer IA, de Graaf AO, et al. Clonal haematopoiesis and UBA1 mutations in individuals with biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis and population-based controls. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2024;63:e45–7. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kead435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belizaire R, Wong WJ, Robinette ML, et al. Clonal haematopoiesis and dysregulation of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2023;23:595–610. doi: 10.1038/s41577-023-00843-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agrawal M, Niroula A, Cunin P, et al. TET2-mutant clonal hematopoiesis and risk of gout. Blood. 2022;140:1094–103. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022015384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Q, Zhao K, Shen Q, et al. Tet2 is required to resolve inflammation by recruiting Hdac2 to specifically repress IL-6. Nature New Biol. 2015;525:389–93. doi: 10.1038/nature15252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heimlich JB, Bhat P, Parker AC, et al. Multiomic profiling of human clonal hematopoiesis reveals genotype and cell-specific inflammatory pathway activation. Blood Adv. 2024;8:3665–78. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023011445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uddhammar A, Eriksson A-L, Nyström L, et al. Increased mortality due to cardiovascular disease in patients with giant cell arteritis in northern Sweden. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:737–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuenninghoff DM, Hunder GG, Christianson TJH, et al. Mortality of large-artery complication (aortic aneurysm, aortic dissection, and/or large-artery stenosis) in patients with giant cell arteritis: a population-based study over 50 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3532–7. doi: 10.1002/art.11480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tomasson G, Merkel PA. In response: risk for cardiovascular disease early and late after a diagnosis of giant-cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:73–80.:230. doi: 10.7326/L14-5015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amiri N, De Vera M, Choi HK, et al. Increased risk of cardiovascular disease in giant cell arteritis: a general population-based study. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2016;55:33–40. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, Neogi T, Jick S. Giant cell arteritis and vascular disease-risk factors and outcomes: a cohort study using UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017;56:753–62. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pariente A, Guédon A, Alamowitch S, et al. Ischemic stroke in giant-cell arteritis: French retrospective study. J Autoimmun. 2019;99:48–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2019.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Boysson H, Aouba A. An Updated Review of Cardiovascular Events in Giant Cell Arteritis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:1005. doi: 10.3390/jcm11041005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Skaggs BJ, Hahn BH, McMahon M. Accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with SLE--mechanisms and management. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2012;8:214–23. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2012.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tervaert JWC. Translational mini-review series on immunology of vascular disease: accelerated atherosclerosis in vasculitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2009;156:377–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.03885.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conrad N, Verbeke G, Molenberghs G, et al. Autoimmune diseases and cardiovascular risk: a population-based study on 19 autoimmune diseases and 12 cardiovascular diseases in 22 million individuals in the UK. The Lancet. 2022;400:733–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01349-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzalez-Gay MA, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, Gomez-Acebo I, et al. Strokes at Time of Disease Diagnosis in a Series of 287 Patients With Biopsy-Proven Giant Cell Arteritis. Medicine (Abingdon) 2009;88:227–35. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181af4518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Boysson H, Liozon E, Larivière D, et al. Giant Cell Arteritis-related Stroke: A Retrospective Multicenter Case-control Study. J Rheumatol. 2017;44:297–303. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.161033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zenone T, Puget M. Characteristics of cerebrovascular accidents at time of diagnosis in a series of 98 patients with giant cell arteritis. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:3017–23. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2814-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Boysson H, Daumas A, Vautier M, et al. Large-vessel involvement and aortic dilation in giant-cell arteritis. A multicenter study of 549 patients. Autoimmun Rev. 2018;17:391–8. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2017.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Espitia O, Bruneval P, Assaraf M, et al. Long-Term Outcome and Prognosis of Noninfectious Thoracic Aortitis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82:1053–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2023.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhattacharya R, Zekavat SM, Haessler J, et al. Clonal Hematopoiesis Is Associated With Higher Risk of Stroke. Stroke. 2022;53:788–97. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zekavat SM, Viana-Huete V, Matesanz N, et al. TP53-mediated clonal hematopoiesis confers increased risk for incident atherosclerotic disease. Nat Cardiovasc Res . 2023;2:144–58. doi: 10.1038/s44161-022-00206-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med . 2017;377:1119–31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1707914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svensson EC, Madar A, Campbell CD, et al. TET2-Driven Clonal Hematopoiesis and Response to Canakinumab: An Exploratory Analysis of the CANTOS Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2022;7:521–8. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2022.0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sano S, Oshima K, Wang Y, et al. CRISPR-Mediated Gene Editing to Assess the Roles of Tet2 and Dnmt3a in Clonal Hematopoiesis and Cardiovascular Disease. Circ Res. 2018;123:335–41. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request.