ABSTRACT

We aimed to explore the predictive value of total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) and beta‐2‐microglobulin (B2M) levels in patients with follicular lymphoma (FL) with a high tumor burden receiving standard first‐line immunochemotherapy. We analyzed 125 patients with the following characteristics: median age, 61 years (55; 67), advanced‐stage disease, 88.8%; high FLIPI, 49.6%; TMTV, > 510 cm3; B2M, > 3 mg/L (24.8%); and R‐CHOP‐like treatment, 86.4%. We defined the following categories: low‐risk (36%), TMTV ≤ 510 cm3 and B2M ≤ 3 mg/L; intermediate‐risk (45.6%), TMTV > 510 cm3 or B2M > 3 mg/L; and high‐risk (18.4%), TMTV > 510 cm3 and B2M > 3 mg/L. The 5‐year overall survival rates were estimated to be 96.1%, 89.1% and 73.7% for low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk patients, respectively (p = 0.003). Patients at intermediate and high risk according to the TMTV/B2M score were at high risk of disease progression within 24 months of treatment initiation (HR = 2.45 [95% CI: 1.23–4.85] and HR = 3.75 [95% CI: 1.7–8.2], respectively). This TMTV/B2M score may identify patients with the highest unmet medical needs.

Keywords: beta‐2‐microglobulin, follicular lymphoma, POD24, prognosis, total metabolic tumor volume

1. Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) is the most common low‐grade lymphoma subtype, accounting for approximately 6% of all mature B‐cell lymphomas in Western countries, with a median age at diagnosis of 64 years [1, 2]. Although the median survival is approximately 20 years, the evolution of the disease is extremely heterogeneous. Currently, FL is still considered an indolent and noncurable lymphoma with a risk of early or late relapse and aggressive histological transformation, which results in a poor prognosis. Thus, indications for initial treatment are still based on the GELF (Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires) criteria, which define high‐burden FL [3]. Obinutuzumab or rituximab in combination with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone (CHOP) or bendamustine followed by 2 years of rituximab or obinutuzumab maintenance [4, 5, 6] remains the gold standard treatment. If there is evidence of a more aggressive clinical course, ESMO guidelines recommend applying obinutuzumab/rituximab‐CHOP [6]. Multiple prognostic scores accounting for clinical and biological criteria, including the FLIPI, FLIPI‐2, PRIMA‐PI and m‐7 FLIPI scores, have been developed over the years [7, 8, 9, 10]. These tools are effective in identifying populations at greater risk but are of limited clinical value because they lack the precision needed to select individual patients who may benefit from a more aggressive treatment strategy or closer follow‐up. More recently, the concept of disease progression events within the first 2 years following first‐line treatment (POD24) was used to define a group of approximately 20% of FL patients with impaired overall survival (OS) and the highest unmet medical need [11, 12]. However, predictors of POD24 have not yet been validated for routine use, and standard first‐line treatment for patients at higher risk of POD24 (including high FLIPI scores and male sex) remains the same as that for other patients.

18F‐FDG PET‒CT has been recommended as a staging assessment for follicular lymphoma for less than 10 years [13]. Its superiority over CT has been demonstrated for baseline staging of patients and follow‐up of the response to first‐line induction immunochemotherapy, with more sensitive and specific detection of pathological sites. The predictive ability of nonclassical PET markers, such as total metabolic tumor volume (TMTV) and total tumor glycolysis (TLG), is less recognized in FL than in other subtypes of NHL, especially diffuse large B‐cell lymphoma (DLBCL) [14, 15, 16]. Nevertheless, Meignan et al. demonstrated that the baseline TMTV is a strong independent predictor of outcomes in FL patients, with markedly inferior survival in 29% of patients with a TMTV > 510 cm3 [17]. The main prognostic scores used in routine clinical practice do not refer to these radiomic tools. To date, the PRIMA‐PI score is the simplest scoring system for FL based on baseline beta‐2‐microglobulin (B2M) levels and the results of bone marrow biopsy (BMB) and has shown relevant prognostic value [10]. BMB in the context of FL is not a common practice among hematological care centers because the procedure is considered invasive and has no direct therapeutic impact. Moreover, the interpretation is closely linked to the quality of the biopsy. Thus, the main predictor of the outcome of the PRIMA‐PI score appears to be the B2M level. Moreover, B2M was one of the covariates permitting the highest inclusion frequencies in the bootstrap procedure to elaborate the FLIPI score and was therefore considered the covariate with the most relevant prognostic weight. Therefore, the B2M level was included in additional analyses to build the FLIPI‐2 score [8]. Because the TMTV and B2M score individually showed prognostic value in several studies, we aimed to evaluate the prognostic relevance of a new score that combines the evaluation of baseline TMTV and B2M levels in FL patients with high tumor burdens.

2. Materials and Methods

Consecutive patients admitted to the Henri Becquerel Center (Rouen, France) between January 1, 2006, and December 31, 2018, were included in this retrospective analysis if they met the following eligibility criteria: age ≥ 18 years, newly diagnosed and histologically confirmed grade 1–3A FL with high tumor burden according to the GELF criteria, treatment with first‐line standard immunochemotherapy (rituximab [R] or obinutuzumab [G] associated with the CHOP regimen or bendamustine [B] or lenalidomide), available baseline PET‒CT and patient nonopposition statements. Patients who presented with Grade 3B FL, histological arguments for high‐grade/aggressive lymphoma transformation or concomitant neoplasia were excluded from this analysis. We collected data from the electronic medical files of the patients in the hospital database. Baseline clinical and biological characteristics at the time of treatment, including Ann Arbor staging, B symptoms, bone marrow and extranodal involvement, FLIPI and PRIMA‐PI prognostic scores, albumin levels, hemoglobin levels, LDH, and B2M, were analyzed.

All patients underwent 18F‐FDG PET/CT with acquisitions performed according to the Society of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging (SNMMI) and the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM) guidelines [18]. Patients were instructed to fast for at least 6 h before 18F‐FDG injection. Injection was not performed unless the blood glucose level was below < 1.8 g/L. Approximately 2.5–4 MBq/kg 18F‐FDG was intravenously injected to ensure a maximum activity of 450 MBq after 30 min of rest as a function of the PET/CT device used: Biograph 16 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA), Biograph 40 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA), Discovery 710 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) or Biograph Vision‐600 (Siemens Medical Solutions, Knoxville, TN, USA). Scans were acquired approximately 60 min (± 5 min) after injection. CT scans for attenuation correction and anatomic localization were acquired from the mid‐thigh toward the base of the skull in most cases, and whole‐body acquisition in helical mode was conducted in all other cases, with 100–120 kV and 100–150 mAs (based on the patient's weight). Contrast media was not injected. Images were reconstructed with validated and commercially available iterative algorithms (ordered‐subset expectation maximization iterative reconstruction). The PET systems were normalized daily, and the calibration coefficient was validated if the day‐to‐day variation remained below 0.3%. The global quantification, from the dose calibrator to the imaging system, was measured internally on a quarterly basis and double checked by the EARL's quality assurance program.

18F‐FDG PET/CT data were anonymized and collected in DICOM format. All the data were then retrospectively reviewed and integrated into an eCRF. Quantitative PET parameters and measurements were performed and extracted by a trained nuclear physician who was unaware of the clinical outcome or patient characteristics. The data were analyzed via the plug‐in PET/CT viewer for FIJI (ImajeJ), which is freeware from the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Division of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging [7, 19]. Forty‐one percent of the maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) was applied as a threshold [8]. First, segmentation was performed automatically via the software and was then checked visually to confirm the inclusion of only pathological lesions. Manual verification and adaptation were then performed if needed. The lesion sites were identified via visual assessment with 18F‐FDG PET/CT images scaled to a fixed SUV display and color table. Each hypermetabolic focus suspected of malignant disease localization was segmented on fused PET/CT images. Segmentations of the hypermetabolic lymph nodes, spleen, bone and other pathological foci were saved separately.

Lesions considered pathological were identified visually as areas of increased uptake outside areas of physiological uptake (e.g., the brain, heart, and urinary system). For bone marrow and spleen involvement, only focal uptake was included. However, in the case of diffuse and intense spleen uptake, the whole spleen was included if its SUV exceeded 150% of the liver background [20].

Response to first‐line treatment was assessed according to the international standardized Lugano classification [21].

To assess the primary objective, we designed a new score that combines the baseline TMTV and B2M levels with the following risk categories:

-

–

Low risk: TMTV less than or equal to 510 cm3 in our cohort and B2M level less than or equal to 3 mg/L

-

–

Intermediate risk: TMTV strictly exceeding 510 cm3 or B2M level strictly exceeding 3 mg/L

-

–

High risk: TMTV strictly exceeding 510 cm3 and B2M level strictly exceeding 3 mg/L

The TMTV value was specifically retained at 510 cm3 as the main threshold based on previous studies with this cutoff value [17, 22].

The B2M threshold was set to 3 mg/L according to its prognostic value in the PRIMA‐PI score [10, 23]. The primary endpoints were OS and PFS according to the three risk categories.

The secondary endpoints included risk factors associated with OS, PFS and POD24 occurrence.

This retrospective study was approved by our internal review board (N°2005B) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

3. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed via R software, version 4.0.0. The characteristics of the sample are described as numbers and percentages for qualitative variables and as the mean, standard deviation (SD), median, first quartile and third quartile for quantitative variables.

Continuous data were compared via the Wilcoxon rank sum test for independent samples, and categorical data were compared via the chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test if appropriate. The OS and progression‐free survival (PFS) of FL patients with a large tumor burden were estimated from Day 1 infusion of immunochemotherapy treatment (R‐CHOP/R‐CHOP‐like). Survival probabilities and general survival curves were estimated via the Kaplan‒Meier method. A log‐rank test was performed to estimate differences between the distributions of survival curves according to the different modalities of potential prognostic factors. Univariate regression Cox models were also used, and the results are presented in the corresponding summary tables with the associated HRs (95% CIs). Multivariate regression Cox models were estimated by retaining significant variables in univariate analysis while minimizing the AIC/BIC and nonredundant variables (not including individual parameters that are within the definitions of different scores). POD24 was defined for all patients who experienced a progression event within 24 months after the start of treatment. The POD24 risk factors were explored via univariate logistic regression models. ORs and their 95% CIs are presented in a table along with the sample size on which each model was estimated, showing the proportion of missing data for some variables. In accordance with Casulo et al. [12], we evaluated OS according to POD24 status with a 24‐month landmark model. For this analysis, patients who died or were censored within 24 months were excluded. The baseline axis timepoint of the Kaplan‒Meier curves corresponds to 24 months after the start of treatment. We therefore removed five POD24+ patients and five POD24‐ patients from the analysis. A two‐tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Population

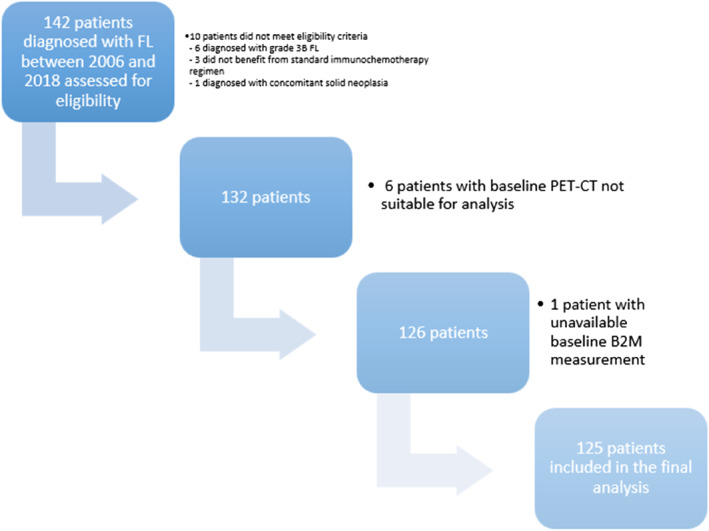

Initially, 142 patients were identified for inclusion in the study. Ten patients were not enrolled because they did not meet the eligibility criteria. Baseline PET‒CT scans were not suitable for analysis in 6 patients, and baseline B2M values at the time of treatment information were not available for 1 patient. Thus, the final population included 125 FL patients (Figure 1). The characteristics of the studied population are provided in Table 1. The median (q1; q3) age at the time of treatment was 61 (55; 67) years, and the sex ratio was relatively balanced. Patients frequently presented with advanced‐stage disease (88.8%), a good ECOG performance status of 0–1 (92%), and a median number of extranodal involvement of 1 (0; 2). Among the patients evaluated by MBM, fifty‐nine (48.8%) presented with bone marrow involvement. The B2M level was > 3 mg/L in 31 patients (24.8%). The R‐CHOP/R‐CHOP‐like regimen was the most commonly used immunochemotherapy (86.4%). Approximately two‐thirds of patients received maintenance therapy with an anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody (63.2%). The median time between diagnosis and Day 1 (D1) of treatment was 56 days (34; 92). According to the PRIMA‐PI score categories, 49 (40.8%), 40 (33.3%) and 31 patients (25.8%) were considered low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk, respectively. The median SUVmax and TMTV were 11.8 (10; 16) and 600 cm3 (261; 1213), respectively. At the time of last follow‐up, 70 patients (56.5%) were in first complete remission (CR). The median follow‐up time in the cohort was 99 months (64.7; 123.8).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the study.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the studied FL population.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| N (NA) | FL with GELF criteria |

| N (%) | N = 125 |

| Mean ± SD | |

| Median (IQR) | |

| Age at time of treatment (years) | 125 (0) |

| 60.7 (± 10.2) | |

| 61 (55; 67) | |

| Sex | 125 (0) |

| Male | 60 (48) |

| Female | 65 (52) |

| Histology | 125 (0) |

| Grade 1 | 39 (31.2) |

| Grade 2 | 72 (57.6) |

| Grade 3A | 14 (11.2) |

| Ann Arbor stage | 125 (0) |

| I–II | 14 (11.2) |

| III–IV | 111 (88.8) |

| B symptoms | 125 (0) |

| Yes | 103 (82.4) |

| No | 22 (17.6) |

| ECOG | 125 (0) |

| 0–1 | 115 (92) |

| 2–4 | 10 (8) |

| Bone marrow involvement | 121 (4) |

| Yes | 59 (48.8) |

| No | 62 (51.2) |

| Number of extranodal involvement | 125 (0) |

| 5.6 (± 2.4) | |

| 6 (3; 8) | |

| Biological parameters at time of treatment | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 125 (0) |

| 13.4 (± 1.6) | |

| 13.5 (13; 14) | |

| Albumin (g/L) | 122 (3) |

| 40.7 (± 5.6) | |

| 41 (38; 44) | |

| B2M (mg/L) | 125 (0) |

| 2.9 (± 2.5) | |

| 2.4 (2; 3) | |

| B2M (in class) | 125 (0) |

| ≤ 3 mg/L | 94 (75.2%) |

| > 3 mg/L | 31 (24.8%) |

| LDH (UI/L) | 124 (1) |

| 147.6 (± 142.3) | |

| 91.5 (72; 136) | |

| Metabolic parameters | |

| SUVmax | 125 (0) |

| 13.6 (± 5.5) | |

| 11.8 (10; 16) | |

| TMTV (cm3) | 125 (0) |

| 858 (± 726) | |

| 600 (261; 1213) | |

| TMTV (in class) | 125 (0) |

| ≤ 510 cm3 | 52 (41.6%) |

| > 510 cm3 | 73 (58.4%) |

| FLIPI‐score | 125 (0) |

| Low risk | 12 (9.6) |

| Intermediate risk | 51 (40.8) |

| High risk | 62 (49.6) |

| PRIMA‐PI score | 120 (5) |

| Low risk | 49 (40.8) |

| Intermediate risk | 40 (33.3) |

| High risk | 31 (25.8) |

| First‐line treatment | 125 (0) |

| R‐CHOP | 108 (86.4) |

| G‐CHOP | 2 (1.6) |

| R‐BENDAMUSTINE | 5 (4) |

| G‐BENDAMUSTINE | 1 (0.8) |

| R‐LENALIDOMIDE | 9 (7.2) |

| Maintenance treatment | 125 (0) |

| Yes | 79 (63.2) |

| No | 46 (36.8) |

| Delay between diagnosis and D1 of treatment (days) | 125 (0) |

| 194.6 (± 501) | |

| 56 (34; 92) | |

| Status at time of last news | 124 (1) |

| 1st CR | 70 (56.5) |

| PR | 2 (1.6) |

| Progression/relapse | 25 (20.2) |

| ≥ 2 CR or more | 27 (21.8) |

| Death | 25 (4) |

| Death related to progression disease | 11 (52.4) |

| Toxicity | 2 (9.5) |

| Others | 8 (38.1) |

Abbreviations: B2M, beta‐2‐microglobulin; CR, complete response; G, obinutuzumab; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PR, partial response; R, rituximab; TMTV, total metabolic tumor volume.

4.2. Outcomes and Risk Factors

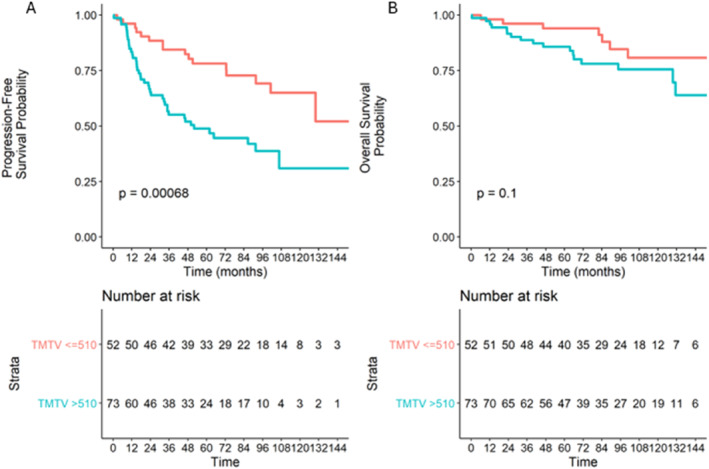

The median PFS was 101.2 months (72.6; NA), and the median OS was not reached in the overall population. At 5 years, the PFS rate was 61.1% (95% CI: 53–70.5). Twenty‐eight patients (22.4%) experienced a POD24 event, and 31 patients (24.4%) experienced a progression event or died within 24 months after the initial diagnosis. The TMTV did not significantly affect OS but did have a significant effect on PFS (p < 0.006): the 5‐year PFS was estimated at 71.9% (95% CI: 61.4; 84.2) for patients who had a TMTV less than or equal to 510 cm3 compared with 50.2% (95% CI: 39.0; 64.7) for patients who had a TMTV greater than 510 cm3 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Overall (A) and progression‐free (B) survival according to baseline TMTV (cutoff set at 510 cm3).

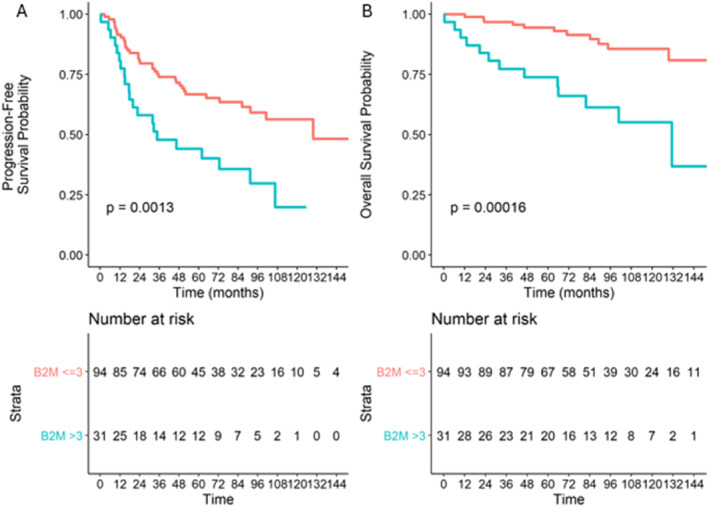

With respect to the B2M level, a significant difference was observed for both OS and PFS: the 5‐year PFS and OS rates were estimated at 44.1% (95% CI: 29.5; 66.1) and 73.8% (95% CI: 59.7; 91.2) for patients who had baseline B2M values strictly higher than 3 mg/L versus 66.8% (95% CI: 57.7; 77.3) and 94.4% (95% CI: 89.8; 99.3) for patients who had B2M values less than or equal to 3 mg/L (Figure 3), respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Overall (A) and progression‐free (B) survival according to the baseline B2M level.

Neither OS nor PFS significantly differed according to bone marrow involvement status at diagnosis (Figure S1). Moreover, we compared bone marrow involvement data with 18F‐FDG PET/CT and bone marrow biopsy data, which revealed metabolic bone marrow involvement in approximately one in five patients for whom the biopsy was negative (Table S1).

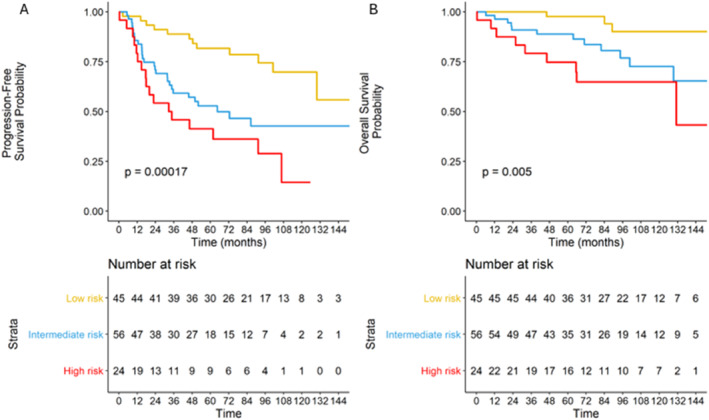

4.3. Prognostic Score Combining TMTV and B2M

According to the 3 predefined risk categories of the TMTV + B2M score with a TMTV cutoff of 510 cm3, 45 (36%), 56 (44.8%) and 24 (19.2%) patients were considered low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk, respectively. Overall, the 5‐year PFS rates were estimated to be 81.7% (95% CI: 71–94), 52.8% (95% CI: 40.8–68.3) and 41.3% (95% CI: 25.5–66.8) for low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk patients, respectively (Figure 4B). In addition, the 5‐year OS rates were estimated to be 96.1% (95% CI: 91–100), 88.9% (95% CI: 80.9–97.7) and 74.8% (95% CI: 59.2–94.5) for low‐, intermediate‐ and high‐risk patients, respectively (p = 0.005) (Figure 4A). We also demonstrated that these results were consistent in the R‐CHOP‐treated population group (Tables S1 and S2).

FIGURE 4.

Overall (A) and progression‐free (B) survival according to the TMTV + B2M score risk groups.

4.4. Univariate and Multivariate Analyses for PFS and OS

The following parameters were associated with an increased risk of progression events in the univariate analysis: baseline TMTV strictly greater than 510 cm3 (HR 2.65; 95% CI: 1.48; 4.76), B2M level strictly greater than 3 mg/L (HR 2.5; 95% CI: 1.5; 4.4), TMTV/B2M intermediate‐risk group (HR 2.79; 95% CI: 1.41; 5.53), TMTV/B2M high‐risk group (HR 4.41; 95% CI: 2.09; 9.33), high‐risk PRIMA‐PI score (HR 2.8; 95% CI: 1.4; 5.3), hemoglobin rate at the time of treatment (HR 0.4; 95% CI: 0.2; 0.8) and male sex (HR 2.3; 95% CI: 1.3; 4.1).

To avoid multicollinearity in regression models due to adjustment for redundant factors, PRIMA PI was not included in multivariate models because the score TMTV/B2M included the of B2M level, which is also a parameter of the PRIMA‐PI score. Moreover, after an analysis of the AIC (Akaike information criterion) and BIC (Bayesian information criterion) for goodness of fit, the PRIMA PI score did not minimize these criteria. After these analyses, the most adequate multivariate regression model was adjusted for male sex (HR 2.22; 95% CI: 1.27–3.90), the hemoglobin rate at the time of treatment (HR 0.46; 95% CI: 0.22–0.97), the TMTV/B2M intermediate‐risk group (HR 2.5; 95% CI: 1.26–4.96) and the TMTV/B2M high‐risk group (HR 3.51; 95% CI: 1.62–7.62); these parameters were associated with an increased risk of progression or death adjusted for male sex and hemoglobin at the time of treatment (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Prognostic factors associated with PFS.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | Inf 95% CI | Sup 95% CI | p | HR | Inf 95% CI | Sup 95% CI | p | |

| TMTV max at diagnosis (> 510 cm3, ref: ≤ 510) | 2.65 | 1.48 | 4.76 | 0.001 | ||||

| B2M at diagnosis (> 3, ref: ≤ 3 mg/L) | 2.59 | 1.50 | 4.47 | 6e−04 | ||||

| Score TMTV (cutoff 510 cm3) + B2M—intermediate risk (ref: low risk) | 2.79 | 1.41 | 5.53 | 0.003 | 2.50 | 1.26 | 4.96 | 0.009 |

| Score TMTV (cutoff 510 cm3) + B2M—High risk (ref: low risk) | 4.41 | 2.09 | 9.33 | < 0.001 | 3.51 | 1.62 | 7.62 | 0.002 |

| SUVmax at diagnosis (> 12, ref: ≤ 12) | 0.93 | 0.55 | 1.57 | 0.8 | ||||

| Bone marrow invasion (Yes ref: No) | 1.35 | 0.79 | 2.31 | 0.3 | ||||

| PRIMA PI—intermediate (ref: Low) | 1.38 | 0.70 | 2.7 | 0.4 | ||||

| PRIMA PI—high (ref: Low) | 2.8 | 1.45 | 5.39 | 0.002 | ||||

| Hemoglobin at time of treatment (≥ 12, ref: < 12 g/dL) | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.46 | 0.22 | 0.97 | 0.04 |

| LDH at time of treatment (> ULN, ref: < ULN) | 1.20 | 0.59 | 2.45 | 0.6 | ||||

| Sex (M, ref: F) | 2.38 | 1.36 | 4.15 | 0.002 | 2.22 | 1.27 | 3.90 | 0.005 |

| FLIPI—intermediate (ref: Low) | 0.89 | 0.33 | 2.39 | 0.8 | ||||

| FLIPI—high (ref: Low) | 1.57 | 0.61 | 4.03 | 0.3 | ||||

Note: Values are bolded when they are considered statistically significant, meaning they are associated with a p‐value less than 0.05.

Abbreviations: B2M, beta‐2‐microglobulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TMTV, total metabolic tumor volume.

The following parameters were associated with an increased risk of death according to the univariate analysis: baseline B2M level strictly greater than 3 mg/L (HR 4.3; 95% CI: 1.96–9.49), the TMTV/B2M intermediate‐risk group (HR 4.13; 95% CI: 1.18–14.53), the TMTV/B2M high‐risk group (HR 7.03 95% CI: 1.90–26.04), a high‐risk PRIMA‐PI score (HR 6.2; 95% CI: 2–19.2) and male sex (HR 4.06; 95% CI: 1.5–10.8).

In the multivariate analysis, male sex (HR 2.13; 95% CI: 1.22–3.74), the TMTV/B2M intermediate‐risk group (HR 2.46; 95% CI: 1.24–4.89) and the TMTV/B2M high‐risk group (HR 4.13; 95% CI: 1.96–8.73) were associated with an increased risk of death adjusted for male sex and hemoglobin at the time of treatment (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Prognostic factors associated with OS.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | Inf 95% CI | Sup 95% CI | p | HR | Inf 95% CI | Sup 95% CI | p | |

| B2M at diagnosis (> 3, ref: ≤ 3 mg/L) | 4.31 | 1.96 | 9.49 | 3e−04 | ||||

| Score TMTV (cutoff 510 cm3) + B2M—intermediate risk (ref: low risk) | 4.13 | 1.18 | 14.53 | 0.03 | 2.46 | 1.24 | 4.89 | 0.01 |

| Score TMTV (cutoff 510 cm3) + B2M—High risk (ref: low risk) | 7.03 | 1.90 | 26.04 | 0.003 | 4.13 | 1.96 | 8.73 | < 0.001 |

| SUVmax at diagnosis (> 12, ref: ≤ 12) | 1.32 | 0.6 | 2.92 | 0.5 | ||||

| Bone marrow invasion (Yes ref: No) | 1.07 | 0.47 | 2.42 | 0.9 | ||||

| PRIMA PI—intermediate (ref: Low) | 2.0 | 0.58 | 6.83 | 0.3 | ||||

| PRIMA PI—high (ref: Low) | 6.26 | 2.04 | 19.24 | 0.001 | ||||

| Hemoglobin at time of treatment (≥ 12, ref: < 12 g/dL) | 0.48 | 0.18 | 1.28 | 0.1 | ||||

| LDH at time of treatment (> ULN, ref: < ULN) | 1.10 | 0.38 | 3.23 | 0.9 | ||||

| Sex (M, ref: F) | 4.06 | 1.52 | 10.83 | 0.005 | 2.13 | 1.22 | 3.74 | 0.008 |

| FLIPI—intermediate (ref: Low) | 0.85 | 0.18 | 3.98 | 0.8 | ||||

| FLIPI—high (ref: Low) | 1.31 | 0.30 | 5.77 | 0.7 | ||||

Note: Values are bolded when they are considered statistically significant, meaning they are associated with a p‐value less than 0.05.

Abbreviations: B2M, beta‐2‐microglobulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TMTV, total metabolic tumor volume.

4.5. POD24 Analysis

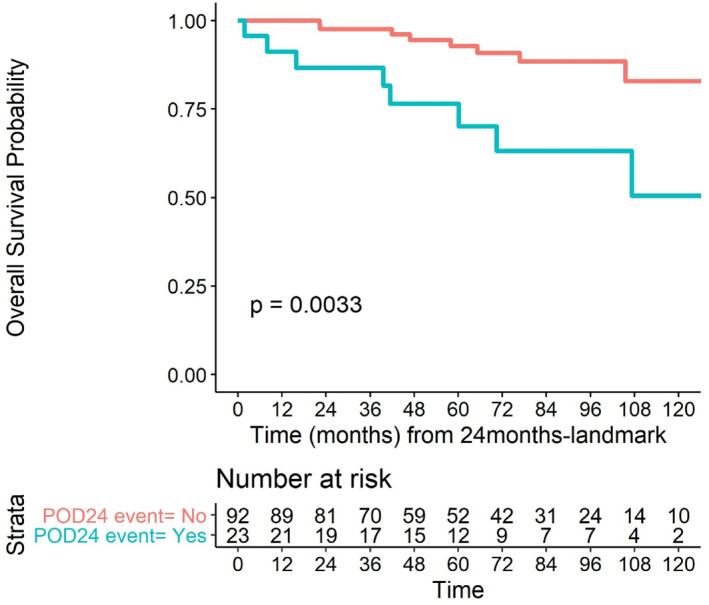

The 5‐year (from Day 1 infusion of immunochemotherapy) survival probability for patients whose disease progressed within the first 24 months was 86.7% (95% CI, 73.8–100), whereas it was 97.6% (95% CI, 94.4–100) for patients who were progression free at 24 months (p = 0.0033) (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Overall survival according to POD24 status (landmark model).

In univariate logistic regression analysis, a hemoglobin level ≥ 12 g/dL (OR 0.32: 95% CI: 0.11; 0.9), a B2M level > 3 mg/L (OR 2.66; 95% CI: 1.07; 6.59), a TMTV > 510 cm3 (OR 4.32; 95% CI: 1.52; 12.3), an intermediate TMTV/B2M value and a high‐risk TMTV/B2M value (OR 3.42; 95% CI: 1.04; 11.25 and OR 7.32; 95% CI: 1.98; 27.1, respectively) were significantly associated with the occurrence of POD24 events. In a multivariate regression model, only the TMTV/B2M score remained significantly associated with POD24 (intermediate risk category: OR 3.18; 95% CI: 0.96; 10.56); high‐risk category: OR 5.83; 95% CI: 1.49; 22.82 (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Factors associated with POD24 (logistic regression model).

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (CI 95%) | P (Wald's test) | Adj. OR (95% CI) | P (Wald's test) | |

| Sex: M (ref: F) | 1.58 (0.67; 3.72) | 0.297 | ||

| Ann Arbor stage: III–IV (ref: I–II) | 1.07 (0.28; 4.12) | 0.926 | ||

| Age at time of treatment (> 61 years) | 0.85 (0.37; 1.97) | 0.703 | ||

| ECOG: 2–4 (ref: 0–1) | 2.53 (0.66; 9.68) | 0.176 | ||

| FLIPI (ref: low risk) | ||||

| Intermediate risk | 0.93 (0.17; 5.07) | 0.933 | ||

| High risk | 2.05 (0.41; 10.28) | 0.385 | ||

| PRIMA‐PI (ref: low risk) | ||||

| Intermediate risk | 0.94 (0.32; 2.80) | 0.916 | ||

| High risk | 2.44 (0.87; 6.86) | 0.089 | ||

| Biological parameters at time of treatment | ||||

| Hemoglobin ≥ 12 (ref: < 12 g/dL) | 0.32 (0.11; 0.9) | 0.03 | ||

| B2M: > 3 (ref: ≤ 3 mg/dL) | 2.66 (1.07; 6.59) | 0.03 | ||

| LDH (> ULN) | 1.74 (0.59; 5.1) | 0.312 | 0.5 (0.17,1.51) | 0.22 |

| Metabolic parameters | ||||

| TMTV at diagnosis (> 510 cm3) | 4.32 (1.52; 12.3) | 0.006 | ||

| TMTV (510 cm3) + B2M (ref: low risk) | ||||

| Intermediate risk | 3.42 (1.04,11.25) | 0.043 | 3.18 (0.96,10.56) | 0.059 |

| High risk | 7.32 (1.98,27.1) | 0.003 | 5.83 (1.49,22.82) | 0.011 |

Note: Values are bolded when they are considered statistically significant, meaning they are associated with a p‐value less than 0.05.

Abbreviations: B2M, beta‐2‐microglobulin; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TMTV, total metabolic tumor volume.

5. Discussion

In this study, we explored outcomes in a relatively homogeneous series of 125 FL patients with high tumor burdens treated with standard first‐line immunochemotherapy; the median PFS was approximately 8 years, and the median OS was not reached. Overall, 22% of patients experienced a POD24 event, and our data are consistent with those previously reported in the literature [11, 12, 24]. However, overall better OS was observed in our cohort than in the recently reported pooled analysis of clinical trial data, which validated POD24 as a robust indicator of poor FL survival [12].

To our knowledge, this study is the first to evaluate the combination of baseline TMTV and B2M values as an approach to predict the prognosis of patients with high tumor burden FL. In contrast to the PRIMA‐PI score, the TMTV/B2M score did not require invasive bone marrow biopsy and was sufficiently powerful to predict PFS, OS and POD24 in multivariate models. We selected a TMTV cutoff of 510 cm3 to homogenize our data with other previously published studies of this value [22].

Rituximab and obinutuzumab prolong survival for most FL patients, but predicting the individual prognosis of patients with FL remains challenging due to the heterogeneity of the patients. In addition, lymphoma remains the main cause of death in FL patients, especially after disease transformation and POD24 events [25]. The prognostic value of the TMTV has already been studied in FL. Meignan et al. demonstrated that patients who had a baseline TMTV > 510 cm3 generally had more advanced‐stage disease and extranodal involvement, including bone marrow involvement. Compared with patients with a baseline TMTV < 510 cm3, the 5‐year PFS was clearly reduced [26]. Given its dynamic capacity and precision in detecting lesions, PET‒CT and radiomic analysis seem to be the most promising prognostic tools to study and build on for years to come. These metabolic‐based prognostic models are currently under investigation because one of their main limitations is the harmonization of daily practice concerning the evaluation of tumor volumes. The classical segmentation method, which refers to the SUV41% model used for volume contouring [27], increases the risk of an underestimation of true lesion volumes if the FDG uptake is very heterogeneous. Conversely, a low SUVmax value increases the risk of overestimation of the TMTV of lesions Another method of segmentation based on an SUV threshold of 4 has already been discussed and applied in other subtypes of lymphomas [28, 29, 30] to differentiate benign and malignant lesions. However, this method may not be as sensitive in detecting all metabolically active lesions and, to date, has not been validated in FL cohorts. In the future, the use of modern software may help practitioners obtain volume computations with precision in a very short time.

Moreover, we found that male sex was associated with a negative prognostic impact on OS and PFS in our FL population. This sex effect has already been reported in numerous studies. For example, male sex was clearly identified as a risk factor for histological transformation in the FL population [31, 32]. Other studies have suggested that the larger distribution volume in men has an impact on rituximab pharmacokinetics, resulting in faster clearance in the male DLBCL population than in the female DLBCL population [33, 34]. More generally, male sex is a well‐known risk factor for developing solid tumors that are directly linked to increased exposure to toxic smoking or alcohol consumption and to cardiovascular comorbidities. These underlying mechanisms remain unclear for the population suffering from hematological malignancies, and other studies are necessary to explain differences in incidence and excess mortality within the male population [35].

These considerations lead us to rethink therapeutic strategies in this category of high‐risk patients with early disease progression. First, confirming the diagnosis with a new biopsy, when feasible, seems important to exclude histological transformation. Over the last few years, one of the most commonly considered salvage options has been autologous stem cell transplant (ASCT) for eligible fit patients. Casulo et al. evaluated the role of ASCT by comparing survival between patients with early therapy failure who received ASCT and those who did not. The 5‐year overall survival did not differ between these groups, whereas a subgroup analysis showed that the 5‐year OS was significantly better, estimated at 73%, for patients who received early ASCT within 12 months of treatment failure than for patients who did not receive ASCT (OS 60%) [23]. For patients who are not candidates for transplant, many other studies have evaluated the efficacy of salvage regimens alone or in combination with obinutuzumab, an alkylating agent such as bendamustine [36], lenalidomide [37] or inhibitors of PI3K [38, 39]. Thus, we can question the importance of innovative therapies such as CAR‐T cells and bispecific antibodies in FL treatment strategies. Early use of this type of treatment is an option for DLBCL patients. For example, axicabtagene ciloleucel is now recommended for DLBCL patients with refractory/relapse disease within the first year after initial first‐line immunochemotherapy [40]. The combination of bispecific anti‐CD3/anti‐CD20 antibodies and the traditional R‐CHOP first‐line regimen is currently being investigated in ongoing clinical trials (NCT04980222; NCT05578976).

Several limitations may affect the general relevance of our results. First, work this was a single‐center retrospective study, which, by its very nature, may have created selection and sampling bias and could partly explain missing data, especially regarding some biological characteristics. The FLIPI‐2 score could not be exploited in our cohort because of missing data concerning the largest diameter of affected lymph nodes. Second, POD24 survival data must be interpreted with caution. The population included in the analysis was clearly selected via a landmark approach because 10 patients were excluded. A The survival probabilities may have been overestimated because we only considered patients who were still alive at the 24‐month follow‐up after the start of initial treatment. Third, our work lacks a mechanistic or biological study to explore the underlying mechanisms associated with elevated TMTV and B2M values and early disease progression. An ancillary study concerning the molecular data of this FL population based on the m7‐FLIPI model, circulating tumoral DNA and mutational profiles of these tumors is underway. Finally, our findings need to be confirmed in a larger prospective model study with a dedicated external validation cohort.

6. Conclusion

Combining the baseline TMTV and B2M values as a prognostic tool in previously untreated FL patients with high tumor burdens may help physicians identify very high‐risk patients with the poorest outcomes. Novel first‐line therapeutic approaches are warranted in this population. A large prospective cohort study is needed to reproduce and confirm the relevance of this prognostic scoring system.

Author Contributions

A.Z. participated in the clinical data collection and data interpretation and wrote the manuscript. S.D.‐C., P.D., S.B. and D.T. performed the PET‒CT review and TMTV measurement. E.L. performed the statistical analysis. V.C. designed the study, coordinated the work, interpreted the data and edited the manuscript. A.Z., S.D., V.C., F.J., H.T., and P.V. were involved in the care of the patients and interpreted the data. All the authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics Statement

This retrospective study was approved by the Center Henri Becquerel internal review board (N°2005B).

Consent

Patients' statements of consent were obtained from all living participants. The publisher is hereby granted permission from the authors to publish the work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Peer Review

The peer review history for this article is available at https://www.webofscience.com/api/gateway/wos/peer-review/10.1002/hon.70010.

Code Availability (Software Application or Custom Code)

Not applicable.

Supporting information

Supporting Information S1

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families. We thank Julie Libraire, a clinical data manager at the Clinical Research Unit, Centre Henri Becquerel, and Doriane Richard, a CRA manager, for support in this study. We thank the Centre de Traitement des Données du Cancéropôle Nord‐Ouest (CTD‐CNO) for data management support. We thank Nathan Lapel for its support in data collection. We also thank Romain Modzelewski for imaging data management in this study.

Funding: The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available for review upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Alaggio R., Amador C., Anagnostopoulos I., et al., “The 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms,” Leukemia 36, no. 7 (2022): 1720–1748, 10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Szumera‐Ciećkiewicz A., Wojciechowska U., Didkowska J., et al., “Population‐Based Epidemiological Data of Follicular Lymphoma in Poland: 15 Years of Observation,” Scientific Reports 10, no. 1 (2020): 14610, 10.1038/s41598-020-71579-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Brice P., Bastion Y., Lepage E., et al., “Comparison in Low‐Tumor‐Burden Follicular Lymphomas Between an Initial No‐Treatment Policy, Prednimustine, or Interferon Alfa: A Randomized Study From the Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe d'Etude des Lymphomes de l'Adulte,” Journal of Clinical Orthodontics 15, no. 3 (1997): 1110–1117, 10.1200/jco.1997.15.3.1110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Salles G., Seymour J. F., Offner F., et al., “Rituximab Maintenance for 2 Years in Patients With High Tumour Burden Follicular Lymphoma Responding to Rituximab Plus Chemotherapy (PRIMA): A Phase 3, Randomised Controlled Trial,” Lancet 377, no. 9759 (2011): 42–51, 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)62175-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bachy E., Seymour J. F., Feugier P., et al., “Sustained Progression‐Free Survival Benefit of Rituximab Maintenance in Patients With Follicular Lymphoma: Long‐Term Results of the PRIMA Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 37, no. 31 (2019): 2815–2824, 10.1200/jco.19.01073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dreyling M., Ghielmini M., Rule S., et al., “Newly Diagnosed and Relapsed Follicular Lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow‐Up,” Annals of Oncology 32, no. 3 (2020): 298–308, 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Solal‐Céligny P., Roy P., Colombat P., et al., “Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index,” Blood 104, no. 5 (2004): 1258–1265, 10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Federico M., Bellei M., Marcheselli L., et al., “Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index 2: A New Prognostic Index for Follicular Lymphoma Developed by the International Follicular Lymphoma Prognostic Factor Project,” Journal of Clinical Orthodontics 27, no. 27 (2009): 4555–4562, 10.1200/jco.2008.21.3991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pastore A., Jurinovic V., Kridel R., et al., “Integration of Gene Mutations in Risk Prognostication for Patients Receiving First‐Line Immunochemotherapy for Follicular Lymphoma: A Retrospective Analysis of a Prospective Clinical Trial and Validation in a Population‐Based Registry,” Lancet Oncology 16, no. 9 (2015): 1111–1122, 10.1016/s1470-2045(15)00169-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bachy E., Maurer M. J., Habermann T. M., et al., “A Simplified Scoring System in De Novo Follicular Lymphoma Treated Initially With Immunochemotherapy,” Blood 132, no. 1 (2018): 49–58, 10.1182/blood-2017-11-816405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Casulo C., Byrtek M., Dawson K. L., et al., “Early Relapse of Follicular Lymphoma After Rituximab Plus Cyclophosphamide, Doxorubicin, Vincristine, and Prednisone Defines Patients at High Risk for Death: An Analysis From the National LymphoCare Study,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 33, no. 23 (2015): 2516–2522, 10.1200/jco.2014.59.7534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Casulo C., Dixon J. G., Le‐Rademacher J., et al., “Validation of POD24 as a Robust Early Clinical Endpoint of Poor Survival in FL From 5,225 Patients on 13 Clinical Trials,” Blood 139, no. 11 (2022): 1684–1693. 10.1182/blood.2020010263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Metser U., Hussey D., and Murphy G., “Impact of 18F‐FDG PET/CT on the Staging and Management of Follicular Lymphoma,” British Journal of Radiology 87, no. 1042 (2014): 20140360, 10.1259/bjr.20140360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cottereau A.‐S., Lanic H., Mareschal S., et al., “Molecular Profile and FDG‐PET/CT Total Metabolic Tumor Volume Improve Risk Classification at Diagnosis for Patients With Diffuse Large B‐Cell Lymphoma,” Clinical Cancer Research 22, no. 15 (2016): 3801–3809, 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-15-2825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cottereau A. S., Versari A., Luminari S., et al., “Prognostic Model for High‐Tumor‐Burden Follicular Lymphoma Integrating Baseline and End‐Induction PET: A LYSA/FIL Study,” Blood 131, no. 22 (2018): 2449–2453, 10.1182/blood-2017-11-816298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thieblemont C., Chartier L., Dührsen U., et al., “A Tumor Volume and Performance Status Model to Predict Outcome Before Treatment in Diffuse Large B‐Cell Lymphoma,” Blood Advances 6, no. 23 (2022): 5995–6004, 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Meignan M., Cottereau A. S., Versari A., et al., “Baseline Metabolic Tumor Volume Predicts Outcome in High–Tumor‐Burden Follicular Lymphoma: A Pooled Analysis of Three Multicenter Studies,” Journal of Clinical Orthodontics 34, no. 30 (2016): 3618–3626, 10.1200/jco.2016.66.9440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li H., Wang M., Zhang Y., et al., “Prediction of Prognosis and Pathologic Grade in Follicular Lymphoma Using 18F‐FDG PET/CT,” Frontiers in Oncology 12 (2022): 943151, 10.3389/fonc.2022.943151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Yang Q., Luo Y., Zhang Y., Zhang W., and Zhou D., “Baseline [18F]FDG PET/CT May Predict the Outcome of Newly Diagnosed Follicular Lymphoma in Patients Managed With Initial ‘Watch‐And‐Wait’ Approach,” European Radiology 32, no. 8 (2022): 5568–5576, 10.1007/s00330-022-08624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Delbeke D., Coleman R. E., Guiberteau M. J., et al., “Procedure Guideline for Tumor Imaging With 18F‐FDG PET/CT 1.0,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 47, no. 5 (2006): 885–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheson B. D., Fisher R. I., Barrington S. F., et al., “Recommendations for Initial Evaluation, Staging, and Response Assessment of Hodgkin and Non‐Hodgkin Lymphoma: The Lugano Classification,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 32, no. 27 (2014): 3059–3067, 10.1200/jco.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Delfau‐Larue M.‐H., van der Gucht A., Dupuis J., et al., “Total Metabolic Tumor Volume, Circulating Tumor Cells, Cell‐Free DNA: Distinct Prognostic Value in Follicular Lymphoma,” Blood Advances 2, no. 7 (2018): 807–816, 10.1182/bloodadvances.2017015164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Federico M., Guglielmi C., Luminari S., et al., “Prognostic Relevance of Serum Beta2 Microglobulin in Patients With Follicular Lymphoma Treated With Anthracycline‐Containing Regimens. A GISL Study,” Haematologica 92, no. 11 (2007): 1482–1488, 10.3324/haematol.11502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bachy E., Cerhan J. R., and Salles G., “Early Progression of Disease in Follicular Lymphoma Is a Robust Correlate but Not a Surrogate for Overall Survival,” Blood Advances 5, no. 6 (2021): 1729–1732, 10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sarkozy C., Maurer M. J., Link B. K., et al., “Cause of Death in Follicular Lymphoma in the First Decade of the Rituximab Era: A Pooled Analysis of French and US Cohorts,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 37, no. 2 (2019): 144–152, 10.1200/jco.18.00400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Meignan M., Cottereau A. S., Versari A., et al., “Baseline Metabolic Tumor Volume Predicts Outcome in High–Tumor‐Burden Follicular Lymphoma: A Pooled Analysis of Three Multicenter Studies,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 34, no. 30 (2016): 3618–3626, 10.1200/jco.2016.66.9440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Boellaard R., Delgado‐Bolton R., Oyen W. J. G., et al., “FDG PET/CT: EANM Procedure Guidelines for Tumour Imaging: Version 2.0,” European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 42, no. 2 (2015): 328–354, 10.1007/s00259-014-2961-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Heek L., Stuka C., Kaul H., et al., “Predictive Value of Baseline Metabolic Tumor Volume in Early‐Stage Favorable Hodgkin Lymphoma ‐ Data From the Prospective, Multicenter Phase III HD16 Trial,” BMC Cancer 22, no. 1 (2022): 672, 10.1186/s12885-022-09758-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barrington S. F., Zwezerijnen B. G. J. C., de Vet H. C. W., et al., “Automated Segmentation of Baseline Metabolic Total Tumor Burden in Diffuse Large B‐Cell Lymphoma: Which Method Is Most Successful? A Study on Behalf of the PETRA Consortium,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 62, no. 3 (2021): 332–337, 10.2967/jnumed.119.238923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Driessen J., Zwezerijnen G. J. C., Schöder H., et al., “The Impact of Semiautomatic Segmentation Methods on Metabolic Tumor Volume, Intensity, and Dissemination Radiomics in 18F‐FDG PET Scans of Patients With Classical Hodgkin Lymphoma,” Journal of Nuclear Medicine 63, no. 9 (2022): 1424–1430, 10.2967/jnumed.121.263067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Casulo C., Herold M., Hiddemann W., et al., “Risk Factors for and Outcomes of Follicular Lymphoma Histological Transformation at First Progression in the GALLIUM Study,” Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia 23, no. 1 (2023): 40–48, 10.1016/j.clml.2022.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sarkozy C., Trneny M., Xerri L., et al., “Risk Factors and Outcomes for Patients With Follicular Lymphoma Who Had Histologic Transformation After Response to First‐Line Immunochemotherapy in the PRIMA Trial,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 34, no. 22 (2016): 2575–2582, 10.1200/jco.2015.65.7163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Müller C., Murawski N., Wiesen M. H. J., et al., “The Role of Sex and Weight on Rituximab Clearance and Serum Elimination Half‐Life in Elderly Patients With DLBCL,” Blood 119, no. 14 (2012): 3276–3284, 10.1182/blood-2011-09-380949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pfreundschuh M., Müller C., Zeynalova S., et al., “Suboptimal Dosing of Rituximab in Male and Female Patients With DLBCL,” Blood 123, no. 5 (2014): 640–646, 10.1182/blood-2013-07-517037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Radkiewicz C., Bruchfeld J. B., Weibull C. E., et al., “Sex Differences in Lymphoma Incidence and Mortality by Subtype: A Population‐Based Study,” American Journal of Hematology 98, no. 1 (2023): 23–30, 10.1002/ajh.26744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sehn L. H., Chua N., Mayer J., et al., “Obinutuzumab Plus Bendamustine Versus Bendamustine Monotherapy in Patients With Rituximab‐Refractory Indolent Non‐Hodgkin Lymphoma (GADOLIN): A Randomised, Controlled, Open‐Label, Multicentre, Phase 3 Trial,” Lancet Oncology 17, no. 8 (2016): 1081–1093, 10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andorsky D. J., Yacoub A., Melear J. M., et al., “Phase IIIb Randomized Study of Lenalidomide Plus Rituximab (R2) Followed by Maintenance in Relapsed/Refractory NHL: Analysis of Patients With Double‐Refractory or Early Relapsed Follicular Lymphoma (FL),” Journal of Clinical Orthodontics 35, no. 15_suppl (2017): 7502, 10.1200/jco.2017.35.15_suppl.7502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Salles G., Schuster S. J., de Vos S., et al., “Efficacy and Safety of Idelalisib in Patients With Relapsed, Rituximab‐ and Alkylating Agent‐Refractory Follicular Lymphoma: A Subgroup Analysis of a Phase 2 Study,” Haematologica 102, no. 4 (2017): e156–e159, 10.3324/haematol.2016.151738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lynch R. C., Avigdor A., McKinney M. S., et al., “Efficacy and Safety of Parsaclisib in Patients With Relapsed or Refractory Follicular Lymphoma: Primary Analysis From a Phase 2 Study (CITADEL‐203),” Blood 138, no. Supplement 1 (2021): 813, 10.1182/blood-2021-147918. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Locke F. L., Miklos D. B., Jacobson C. A., et al., “Axicabtagene Ciloleucel as Second‐Line Therapy for Large B‐Cell Lymphoma,” New England Journal of Medicine 386, no. 7 (2022): 640–654, 10.1056/nejmoa2116133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting Information S1

Data Availability Statement

All data are available for review upon request to the corresponding author.