Abstract

The fifth increased branching ramosus (rms) mutant, rms5, from pea (Pisum sativum), is described here for phenotype and grafting responses with four other rms mutants. Xylem sap zeatin riboside concentration and shoot auxin levels in rms5 plants have also been compared with rms1 and wild type (WT). Rms1 and Rms5 appear to act closely at the biochemical or cellular level to control branching, because branching was inhibited in reciprocal epicotyl grafts between rms5 or rms1 and WT plants, but not inhibited in reciprocal grafts between rms5 and rms1 seedlings. The weakly transgressive or slightly additive phenotype of the rms1 rms5 double mutant provides further evidence for this interaction. Like rms1, rms5 rootstocks have reduced xylem sap cytokinin concentrations, and rms5 shoots do not appear deficient in indole-3-acetic acid or 4-chloroindole-3-acetic acid. Rms1 and Rms5 are similar in their interaction with other Rms genes. Reciprocal grafting studies with rms1, rms2, and rms5, together with the fact that root xylem sap cytokinin concentrations are reduced in rms1 and rms5 and elevated in rms2 plants, indicates that Rms1 and Rms5 may control a different pathway than that controlled by Rms2. Our studies indicate that Rms1 and Rms5 may regulate a novel graft-transmissible signal involved in the control of branching.

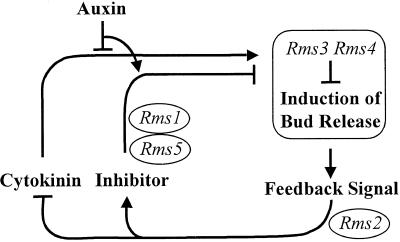

Compared with wild-type (WT) plants, the ramosus (rms) mutants of pea (Pisum sativum; rms1 through rms4) display increased branching at most nodes on the shoot (for review, see Beveridge, 2000). The rms mutants are the only increased-branching mutants that have been well characterized for involvement of long-distance signals, known and unknown, in branching control. This was achieved by investigating grafting responses with WT, shoot auxin level and transport, auxin responses, and root xylem sap cytokinin concentrations. These various analyses have lead us to conclude that two novel graft-transmissible signals are involved in branching control. One appears to be a feedback signal and the other acts as a branching inhibitor (Foo et al., 2001). We have developed a hypothesis for branching control that incorporates novel long-distance signals together with auxin and cytokinin (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Model of branching regulation in pea. Results presented herein indicate that Rms5 acts similarly to Rms1. Rms1 through Rms4 gene action is based on our previous studies (Beveridge et al., 1994, 1996, 1997a, 1997b, 2000; Beveridge, 2000; Foo et al., 2001). Small arrowheads indicate branching promotion; flat-end lines indicate branching inhibition.

Auxin levels in nodes of different developmental stages in rms1, rms2, rms3, and rms4 shoots are not reduced, and in rms1 and rms2, these levels are sometimes elevated (Beveridge et al., 1994, 1996, 1997b). In a similar manner, polar auxin transport is not reduced in these mutants (Beveridge et al., 2000; Beveridge, 2000). In contrast, root xylem sap cytokinin concentration in rms1, rms3, and rms4 plants is considerably reduced (Beveridge et al., 1997a, 1997b; Beveridge, 2000). Grafting different shoot and rootstock combinations demonstrates that two of these mutations, rms1 and rms2, cause increased branching through alteration of the level or transport of long-distance signals (Fig. 1). As root xylem sap cytokinin and shoot auxin levels are not increased or reduced, respectively, in rms1 plants, the long distance signal regulated by Rms1 appears to be novel.

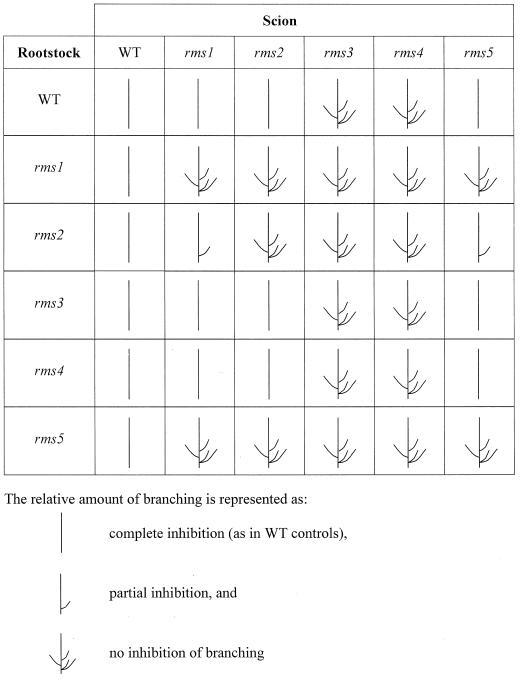

As discussed above, Rms1 and Rms2 act in the rootstock and shoot to control graft-transmissible signals (Beveridge et al., 1994, 1996, 1997b; Fig. 1). In contrast, Rms3 and Rms4 action is largely confined to the shoot because rms3 or rms4 scions display a branching phenotype, regardless of rootstock genotype (Beveridge et al., 1996, 1997a; Fig. 1).

Reciprocal grafts among rms mutants have demonstrated interaction of Rms gene products or signals they regulate. For example, branching occurs in rms2 scions grafted to rms1 rootstocks, but not in rms1 scions grafted to rms2 rootstocks. As Rms1 and Rms2 do not appear to act on the same biosynthetic pathway (Beveridge et al., 1997b; discussed below), Rms1 may control a signal moving from root to shoot, and Rms2 may control a different signal moving from shoot to root (Beveridge et al., 1997b; Fig. 1). As described above, neither of these signals is likely to be auxin (Beveridge et al., 1997b), yet both are required for a normal auxin response (Beveridge et al., 2000). More complex grafting procedures have led us to propose that Rms1 controls a signal that acts as a branching inhibitor and moves acropetally in the shoot (Foo et al., 2001).

Apart from rms2 shoots that do not cause a decrease in cytokinin export, branching in pea is associated with the down-regulation of xylem sap cytokinin export from roots. This finding is based on reciprocal grafting studies of rms1, rms3, and rms4 with WT plants, and effects of benzyl adenine-induced bud release in WT plants (Beveridge et al., 1997a; Beveridge, 2000). We consider the shoot-to-root signal that down-regulates cytokinin export from the roots as an autoregulatory feedback signal (Fig. 1). Once again, this feedback signal is probably not auxin, as the decrease in cytokinin export from roots is not associated with elevated shoot auxin level or transport as predicted by auxin/cytokinin models (Li et al., 1995). Rms2 may control this feedback signal because rms2 is the only mutant shown to have elevated root xylem sap cytokinin concentrations (Beveridge et al., 1997b). The additive phenotype of the rms1 rms2 double mutant, together with its high root xylem sap [9R]Z concentration, also supports the hypothesis that Rms1 and Rms2 control different but interdependent pathways rather than acting on different steps in the same pathway (Beveridge, 2000).

Here we describe the phenotype of rms5 plants and the interaction of Rms5 with other Rms genes. This work has lead to the addition of Rms5 to our branching model (Fig. 1).

RESULTS

Phenotype of rms5 and rms1 rms5 Mutant Plants

Three mutants, rms5-2, rms5-3, and rms1-4, derived from the dwarf WT cv Paloma, were compared in detail. Under 18-h photoperiod conditions, rms5-3 and rms1-4 plants produced substantial first order laterals (Fig. 2) at nodes 1 and 2, whereas basal branching in comparable WT plants was variable and less vigorous (Figs. 3 and 4). Mutant rms5-3 and rms1-4 plants also produced at least two first order laterals from the same leaf axil at nodes 1 and/or 2 (data not shown). First order laterals at nodes 3 to 9 were up to 6-fold longer (P < 0.05) in rms1-4 plants compared with rms5-3 plants (Fig. 4). The number and length of first order laterals in rms5-2 plants was similar to rms5-3 (data not shown; P > 0.05; n = 7–10). The total length of second order laterals, which arose from basal first order laterals, was similar in rms1 and rms5 mutants (Fig. 4). Both mutants had a similar number of second order laterals at nodes 1 and 2, but rms1-4 plants produced more second order laterals at node 3 (data not shown). The ratio of lateral length to main stem length was significantly less (P < 0.05) in rms5-3 than rms1-4 plants for first and second order laterals (Table I).

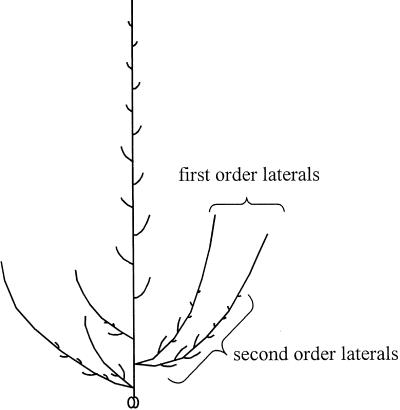

Figure 2.

Architecture of a typical dwarf rms garden pea shoot illustrating lateral branching. First order laterals arise from leaf axils on the main stem, whereas second order laterals arise from nodes along the stem of first order laterals. More than one lateral can grow out from the same leaf axil. Only laterals >1 mm are shown. Leaves are not represented.

Figure 3.

Phenotype of 26-d-old (left to right) cv Paloma, rms1-4, rms5-3, and rms1-4 rms5-3 double-mutant plants.

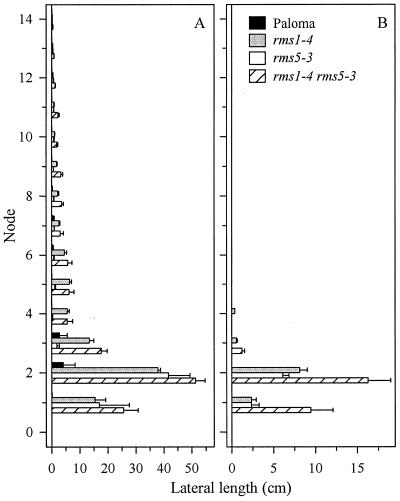

Figure 4.

Length of first order laterals (A) and second order laterals (B) at each node of the 40-d-old cv Paloma, rms1-4, rms5-3, and rms1-4 rms5-3 plants shown in Table I. Only 14 nodes are represented. Data are means ± se; n = 5.

Table I.

Phenotypic comparison between WT (cv Paloma), rms1-4, rms5-3, and rms1-4 rms5-3 plants at 40 d

| Genotype | Ratio of Lateral Length to Main Stem Length

|

No. of Leaves Expanded | Main Stem Length | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First order laterals | Second order laterals | |||

| cm | ||||

| WT | 0.46 ± 0.09 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 16.5 ± 0.24 | 39.7 ± 1.06 |

| rms1-4 | 3.80 ± 0.24a | 0.47 ± 0.06 | 14.2 ± 0.04a | 24.3 ± 0.93 |

| rms5-3 | 2.15 ± 0.11 | 0.28 ± 0.02 | 14.0 ± 0.26a | 30.2 ± 1.26a |

| rms1-4 rms5-3 | 4.33 ± 0.28a | 0.90 ± 0.13 | 15.0 ± 0.22 | 29.5 ± 1.44a |

Data shown are means ± se; n = 5. Values within a column that have the same letter are not significantly different at the P = 0.05 level.

Double-mutant rms1-4 rms5-3 plants had increased branching compared with the single-mutant parents (Table I; Figs. 3 and 4). Double mutants branched profusely from nodes 1 to 3 on the main stem, producing up to three laterals per node (data not shown). A single lateral greater than 1 cm was produced from nodes 4 to 12, and then all laterals above this node were less than 1 cm. However, the additive effects of the two mutations rms1-4 and rms5-3 were most clearly apparent from data on second order laterals. Based on the ratio of lateral length to main stem length, the index for the double mutant was only marginally elevated (P > 0.05) for first order laterals, but was at least twice that of either single mutant for second order laterals (Table I). The double mutant produced significantly longer second order laterals at nodes 1 and 2 compared with rms1-4 and rms5-3 plants (P < 0.05; Fig. 4B). Double mutants also produced significantly (P < 0.05) more second order laterals than rms1-4 or rms5-3 plants at node 2, and more second order laterals at node 3 than rms5-3 plants (P < 0.05; data not shown).

Plants of all mutant genotypes had fewer leaves expanded and a significantly (P < 0.05) shorter main stem than the WT parent plant, cv Paloma, with rms1-4 plants significantly shorter than rms5-3 or rms1-4 rms5-3 plants (Table I). All mutant and WT plants flowered at about node 18 under an 18-h photoperiod (data not shown).

To observe the effect of an rms5 mutation on the phenotype of a tall (Le) plant, dwarf rms5-3 plants were crossed with tall cv Torsdag. Like tall rms1 plants, tall F2 rms5-3 plants branched at basal and at aerial nodes, producing a main stem approximately 10% shorter than WT plants (P < 0.01), despite having a similar number of leaves expanded (data not shown; WT, n = 8, rms5-3, n = 8). These results are similar to those reported by Murfet and Symons (2000a), except that a few tall rms5 segregants produced only aerials laterals in that study.

Grafting Studies

WT (cv Paloma) rootstocks substantially inhibited branching at nodes 1 to 6 in rms5-2 scions compared with self-grafted rms5-2 plants (Fig. 5). In all graft combinations, laterals were less than 10 mm long above node 6. In a similar manner, WT rootstocks inhibited branching in rms1-4 scions. Mutant rms1-4 and rms5-2 rootstocks did not promote branching in WT shoots. Branching was not inhibited in shoots of reciprocally grafted rms1-4 and rms5-2 plants. Instead, lateral lengths increased about 2-fold at node 2 of rms5-2/rms1-4 (notation; scion/rootstock) plants when compared with rms5-2 self-grafted plants (P < 0.05). This increase in branching at certain nodes was not observed in rms1-4 scions of the reciprocal graft combination or in rms5-3/rms1-1 plants (data not shown; Fig. 6A). This slight difference in the branching pattern may be due to the different genetic background of rms5-3 (cv Paloma) and rms1-1 (cv Parvus) plants rather than to a direct effect of the Rms genes themselves.

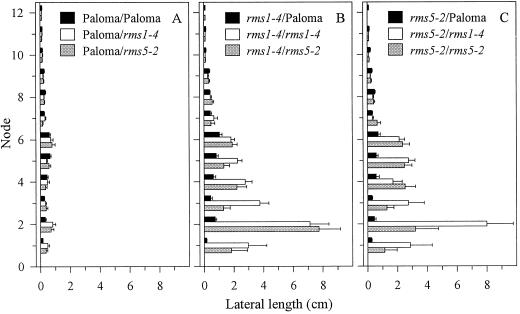

Figure 5.

First order lateral lengths at consecutive nodes of cv Paloma (A), rms1-4 (B), and rms5-2 scions (C) grafted to cv Paloma, rms1-4, or rms5-2 rootstocks. The plants were 36 d old at the time of scoring. Data are means ± se; n = 10 to 13. Notation is scion/rootstock.

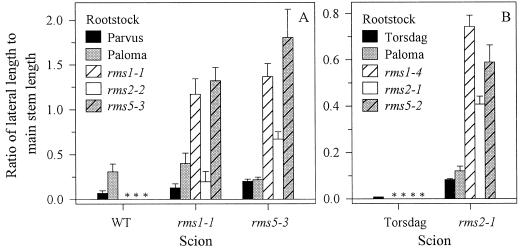

Figure 6.

Ratio of first order lateral length to main stem length of reciprocally grafted WT (cv Parvus and cv Paloma), rms1-1, rms2-2, and rms5-3 plants (A) and WT (cv Torsdag and cv Paloma), rms1-4, rms2-1, and rms5-2 plants (B). A and B represent separate experiments in which 59- and 37-d-old plants were scored, respectively. Data are means ± se; n = 6 to 12. Notation is scion/rootstock. An asterisk denotes graft combinations not performed in this study, but see Figure 10.

The interactions of long-distance signals regulated by Rms genes were investigated by reciprocally grafting rms1 and rms5 with a third mutant, rms2. As previously shown (Fig. 5; Beveridge et al., 1997b), branching in rms1-1, rms2-1, and rms5-3 scions was significantly reduced by grafting to their respective WT rootstocks (cv Parvus, cv Torsdag, or cv Paloma; Fig. 6). Compared with mutant self-grafts, branching in rms1-1 and rms5-3 scions was reduced by grafting to rms2-2 rootstocks (Fig. 6A). It is interesting that branching in rms5-3/rms2-2 plants was not reduced to the same level as branching in rms1-1/rms2-2, but this may be due to genetic background variation (rms5-3, cv Paloma; rms1-1 and rms2-2, cv Parvus). In contrast, rms2-1/rms5-2 and rms2-1/rms1-4 plants branched slightly more than rms2-1 self-grafted plants (Fig. 6B).

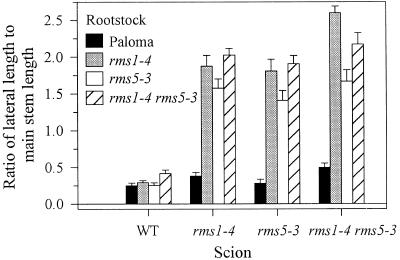

Like grafting responses with the single mutants, branching in rms1-4 rms5-3 double-mutant scions was inhibited when grafted to WT rootstocks (Fig. 7). Likewise, rms1-4 rms5-3 rootstocks did not significantly promote branching in WT scions (Fig. 7). In some graft combinations, scions were more highly branched when grafted to other mutant rootstocks than in self-graft combinations (Fig. 7). For example, rms5-3/rms1-4 rms5-3 plants branched more than rms5-3 self-grafts (P < 0.01).

Figure 7.

Ratio of first order lateral length to main stem length of reciprocally grafted WT (cv Paloma), rms1-4, rms5-3, and rms1-4 rms5-3 plants. The plants were 41 d old at the time of scoring. Data are means ± se; n = 9 to 12. Notation is scion/rootstock.

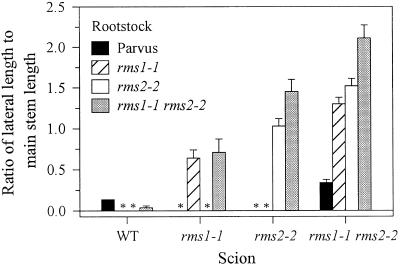

As observed with the other graft combinations described above, WT rootstocks inhibited branching in rms1-1 rms2-2 double-mutant scions (Fig. 8). When rms1-1, rms2-2, and rms1-1 rms2-2 were reciprocally grafted, branching was not inhibited in any scion to the level caused by WT rootstocks. Double-mutant rootstocks caused a significant (P < 0.05) increase in branching of rms2-2 scions when compared with rms2-2 self-grafts. rms1-1 and rms2-2 rootstocks reduced branching in rms1-1 rms2-2 scions by approximately one-third compared with double-mutant self-grafts. This decrease in branching in rms1-1 rms2-2/rms1-1 and rms1-1 rms2-2/rms2-2 combinations was accentuated by expressing lateral lengths relative to main stem length (Fig. 8), as double-mutant self-grafts were significantly shorter than all other double-mutant scion graft combinations (P < 0.005; data not shown).

Figure 8.

Ratio of first order lateral length to main stem length of reciprocally grafted WT (cv Parvus), rms1-1, rms2-2, and rms1-1 rms2-2 plants. The plants were 41 d old at the time of scoring. Data are means ± se; n = 8 to 12. Notation is scion/rootstock. An asterisk denotes graft combinations not performed in this study, but see Figure 10.

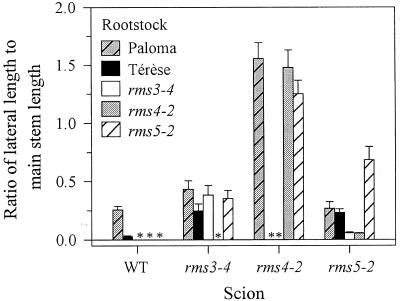

Mutant rms3-4 and rms4-2 rootstocks inhibited branching in rms5-2 scions to a greater extent than WT (cv Paloma and cv Térèse) rootstocks (P < 0.01), whereas WT or rms5-2 rootstocks could not inhibit branching in rms3-4 or rms4-2 scions (Fig. 9). A summary of these and other single-mutant graft responses generated from this and our previous work is presented in Figure 10.

Figure 9.

Ratio of first order lateral length to main stem length of reciprocally grafted cv Paloma, cv Térèse, rms3-4, rms4-2, and rms5-2 plants. The plants were 36 d old at the time of scoring. Data are means ± se; n = 10 to 12. Notation is scion/rootstock. An asterisk denotes graft combinations not performed in this study, but see Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Branching phenotype of reciprocally grafted WT and rms mutant plants. This figure represents results from grafting studies with many alleles and different genotypes. Data presented are from Figures 5, 6, and 9 and Beveridge et al. (1994, 1996, 1997a, 1997b).

Hormone Analyses

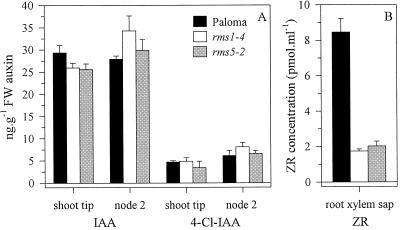

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-selected ion monitoring (GC-MS-SIM) analysis was used to determine endogenous indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) and 4-chloroindole-3-acetic acid (4-Cl-IAA) levels in the shoot tip and node 2 of 8-d-old (approximately three leaves expanded) cv Paloma, rms1-4, and rms5-2 plants (Fig. 11A). At this stage the mutants were undergoing bud release. The shoot tip and node 2 tissue of rms1-4 and rms5-2 plants had a similar amount of IAA and 4-Cl-IAA when compared with WT plants. 4-Cl-IAA was included in this study, as it has been associated with rapidly dividing tissue in young pea seedlings (Schneider et al., 1985; Magnus et al., 1997).

Figure 11.

Hormone levels in WT (cv Paloma), rms1-4, and rms5-2 plants. A, Auxin content (IAA and 4-Cl-IAA) in the shoot tip (above the third expanded leaf) and node 2 of 8-d-old plants. B, Zeatin riboside ZR concentration in root xylem sap of 24-d-old plants. Data represented are the means ± se of three pools of 18 to 20 plants.

To make a direct comparison with our previous reports of cytokinin levels in pea (Beveridge et al., 1997a, 1997b), only the concentration of zeatin riboside ([9R]Z) in the root xylem sap is reported here (Fig. 11B). The root xylem sap [9R]Z concentration was determined from 24-d-old (approximately eight leaves expanded) WT (cv Paloma), rms1-4 and rms5-2 plants using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS-MS) analysis. The [9R]Z concentration in rms5-2 plants was decreased by 4-fold compared with WT (cv Paloma) plants. This decrease was similar to that in comparable rms1-4 plants.

DISCUSSION

Our previous studies have indicated that Rms1 may regulate branching in pea by controlling a novel graft-transmissible signal and that Rms2 may control a second novel signal involved in feedback down-regulation of cytokinin export from the roots and up-regulating the Rms1 signal (Beveridge et al., 1994, 1997b; Fig. 1). We have now demonstrated that like Rms1 and Rms2, Rms5 also regulates the level or transport of a graft-transmissible signal (Fig. 1). Rms5 can act in the shoot and rootstock, as branching was inhibited in rms5 scions grafted to WT rootstocks and in WT scions grafted to rms5 rootstocks (Fig. 5).

Mutation at the Rms1 or Rms5 locus produced plants with a highly branched phenotype, particularly at basal nodes in dwarf backgrounds, but also at aerial nodes in tall backgrounds (Fig. 4; Arumingtyas et al., 1992; Beveridge et al., 1997b; Murfet and Symons, 2000a). Other effects on plant growth and development were relatively minor, but included a decrease in main stem length of mutant plants compared with WT plants (Table I; Murfet and Symons, 2000a).

The rms1-4 rms5-3 double mutant produced longer first and second order laterals (P < 0.05) than either parent, causing the double mutants to appear “bushier” (Figs. 3 and 4). Based on this increase in branching, the rms1-4 rms5-3 phenotype can be described as weakly transgressive (additive). A transgressive phenotype would be predicted if both genes acted on the same pathway and if both mutations were leaky or there was genetic redundancy. However, a transgressive branching phenotype could also indicate that these genes act on different pathways.

The weakly transgressive phenotype of the rms1 rms5 double mutant (Table I; Fig. 3) is in contrast to the strongly transgressive phenotype of tall (Le) rms1 rms2 plants (Beveridge et al., 1997b) and particularly the rms2 rms5 and rms2 rms4 double mutants (Murfet and Symons, 2000a, 2000b). This indicates that the cause of the transgressive phenotypes may differ among these double mutants. The highly branched phenotype of rms2 rms5 plants indicates that Rms2 and Rms5 may act on different pathways. This was further supported by grafting studies with the rms1 rms2 and rms1 rms5 double mutants (Figs. 7 and 8).

Reciprocal grafting studies support the notion that the Rms1 and Rms5 genes interact to inhibit branching, perhaps by acting closely on the same pathway (Fig. 1). Branching is inhibited in shoots of reciprocally grafted mutant and WT plants, but not inhibited in reciprocal grafts between rms1 and rms5.

Grafting studies were performed with several other rms mutants to examine interactions between Rms5 and the other Rms genes. We also examined whether different mutant alleles and genetic backgrounds produced the same grafting response. Any differences in branching observed in graft combinations with tall (Le) and dwarf (le) genotypes are unlikely to be due directly to differences at the Le locus because Le does not have a graft-transmissible effect (Reid et al., 1983).

Grafting studies with rms1, rms2, rms5, and WT seedlings provided further evidence for similarities in action of Rms1 and Rms5, as both mutants responded similarly when grafted with rms2 (Fig. 6; Beveridge et al., 1997b). This indicates that in rms2 scions grafted to rms1 or rms5 rootstocks, the rms2 mutation may block the action of Rms1 and Rms5, resulting in a branching phenotype. In a reciprocal manner, branching is inhibited in rms1 or rms5 scions grafted to rms2 rootstocks because Rms1 and Rms5 genes present in the rms2 rootstock are able to facilitate synthesis or transport of the graft-transmissible signal. We suggest that branching is controlled by an autoregulatory loop comprising shoot-to-root and root-to-shoot signals and that a block in any part of this loop results in branching (Fig. 1).

Grafting responses of the rms1 rms2 and rms1 rms5 double mutants with WT plants were similar. As expected, branching was inhibited in double-mutant scions grafted to WT rootstocks, but not inhibited, or only slightly inhibited, in double-mutant self-grafts or grafts of double mutants with single mutants (Figs. 7 and 8). Grafting rms1-4, rms5-3, and rms1-4 rms5-3 scions to rms1-4 rootstocks generally resulted in a slightly greater ratio of lateral length to main stem length than when these scions were grafted to rms5-3 rootstocks (Fig. 7; P < 0.05). The biological significance, if any, of these small differences caused by rms1-4 and rms5-3 mutant rootstocks is unknown at this stage.

Grafting studies also provide further evidence that Rms3 and Rms4 act largely in the shoot (Beveridge et al., 1996), as mutant rms5 rootstocks did not inhibit branching in rms3 and rms4 scions, but rms3 and rms4 rootstocks inhibited branching in rms5 scions (Fig. 9). Mutant rms3 and rms4 rootstocks were more effective than WT rootstocks at inhibiting branching in rms5 scions. This was also observed in rms2 scions grafted to rms3 and rms4 rootstocks (Beveridge et al., 1996), demonstrating that Rms3 and Rms4 genes or their products may also act in the rootstock.

The rms5 mutant is the fourth rms mutant characterized with low root xylem sap cytokinin ([9R]Z) concentrations (Fig. 11B; Beveridge et al., 1997a, 1997b; Beveridge, 2000). The 4-fold decrease in [9R]Z concentration of 24-d-old rms5-2 and rms1-4 plants compared with cv Paloma (Fig. 11B) is smaller than the 15-fold reduction previously reported for 28-d-old rms1-1 compared with cv Parvus plants (Beveridge et al., 1997b). Genetic background or developmental stage of mutant axillary buds at the time of harvest may explain this difference.

Like the other four rms mutants previously characterized, rms5 did not appear to be deficient in IAA in the shoot tip or node 2 (Fig. 11A; Beveridge et al., 1996, 1997b) at the time of basal bud release (8-d-old). In a similar manner, 4-Cl-IAA levels were not reduced in these plants (Fig. 11A). The similar auxin levels measured for rms1-4 and WT differ from previous results where IAA content of rms1-1 plants in the shoot tip and nodal tissues was 2- to 3-fold higher than for WT plants (Beveridge et al., 1997b). This difference may again be explained by the different age and genotype of the plants. These new results demonstrate that decreased auxin levels do not necessarily accompany bud outgrowth in rms1 and rms5 plants.

The collective evidence from studies with rms mutants clearly indicates that graft-transmissible signals are major components of shoot branching control. As we have suggested previously (Beveridge et al., 1994, 1996, 1997a, 1997b, 2000; Napoli et al., 1999; Beveridge, 2000), the concept of auxin and cytokinin as sole regulators of bud outgrowth is insufficient to explain our results. At least two additional novel signals appear to be involved in the control of branching, one under the control of Rms1 and Rms5, and a second controlled by Rms2 (Fig. 1). The indirect action of auxin in inhibiting bud outgrowth following decapitation is explained by effects of these novel signals (Beveridge et al., 2000). As Rms1 and Rms5 probably control the same novel graft-transmissible signal involved in branching regulation, we predict that rms5 may also have a reduced auxin response. Further examination of rms5 plants, including interstock, two-rootstock, and Y-grafting studies similar to those performed with rms1 plants (Foo et al., 2001), will indicate whether Rms5 also controls an acropetally transported branching inhibitor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

All plants used in this study have a late-flowering, quantitative, long-day habit. The rms mutants are recessive and display increased branching (Arumingtyas et al., 1992). Mutant lines used in this study were derived from various cultivars of pea (Pisum sativum) by authors given in Table II. The double-mutant line HL295, with the genotype rms1-4 rms5-3, was derived from the cross, Wt15236 × Wt15241. Backcrossing to each single-mutant parental line and growing seven F1 plants of each backcross confirmed the genotype of the candidate double-mutant plant. The double mutant rms1-1 rms2-2 (HL252) was described by Beveridge et al. (1997b).

Table II.

Origin of the mutant lines used in this study (from Symons and Murfet, 1997)

| Mutant Allele | Mutant Line | Initial Line | Mutagenic Agent | Author of Mutant Line |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rms1-1 | WL5237 | Parvus | X-rays | S. Blixt |

| rms1-4 | Wt15236 | Paloma | Fast neutrons and NEU | W.K. Swiecicki |

| rms2-1 | K524 | Torsdag | EMS | K.K. Sidorova |

| rms2-2 | WL5951 | Parvus | EMS | S. Blixt |

| rms3-4 | T2-30 | Térèse | EMS | C. Rameau |

| rms4-2 | Wt15242 | Paloma | NEU | W.K. Swiecicki |

| rms5-2 | Wt10852 | Paloma | NEU | W.K. Swiecicki |

| rms5-3 | Wt15241 | Paloma | NEU | W.K. Swiecicki |

Cv Parvus and cv Torsdag are tall (Le), and cv Paloma and cv Térèse are dwarf (le). Térèse is also afila (af), having tendrils in place of leaflets. Mutagenic agents: EMS, ethyl methane sulfonate; NEU, N-nitroso-N-ethyl urea.

Growing Conditions

All plants were grown in a greenhouse at 26°C ± 4°C/18°C ± 2°C day/night temperatures with the natural photoperiod extended to 18 h with weak incandescent (60 W) lights. Unless otherwise stated, seeds were planted two per pot in 15-cm pots containing a 1:1 (v/v) mixture of pasteurized sand/peat potting mix and perlite or in a peat blend potting mix (7:2:1, pine bark fines:peat:sand). Osmocote (2 g per pot; Scotts, Baulkam Hills, Australia) was incorporated into the potting mix.

Phenotype Measurement

Nodes were numbered acropetally from the first scale leaf (node 1). Total main stem length was measured from node 1 to the main shoot apex. Lateral (axillary shoot) lengths were measured from the base of the lateral (in the leaf axil) to the lateral shoot apex. Laterals arising from the leaf axils of the main stem are termed first order laterals and laterals arising at nodes along the stem of first order laterals are termed second order laterals (Fig. 2). In some strongly branched plants, more than one lateral grew from the same leaf axil (Fig. 2). The node of flower initiation was the first node that initiated a flower on the main stem of the plant. Lateral length in Figures 5 through 9 is based on first order laterals only. The ratio of lateral length to main stem length was used (Table I; Figs. 6–9) to compensate for height differences, e.g. between tall (Le) and dwarf (le) plants. Other branching terminology and a detailed diagram illustrating a branching pea plant is given by Murfet and Symons (2000a).

Grafting Technique

Epicotyl-to-epicotyl wedge grafts were performed on 6- to 7-d-old seedlings as described by Beveridge et al. (1994). All lateral bud growth from the cotyledonary node of the rootstock was removed. Only vigorous plants were included in the analysis. Because some graft combinations were performed with plants from different genetic backgrounds, control grafts often included combinations with more than one WT line. All grafting experiments, with the exception of the double-mutant grafts, were repeated at least twice, usually with different mutant alleles.

Harvest of Plant Material

The shoot tip and node 2 were harvested from 8-d-old plants (approximately three leaves expanded). The node 2 portion consisted of stem tissue, approximately 5 mm, on each side of the node 2 leaf axil. The shoot tip consisted of all tissue above and including node 3. The root xylem sap was harvested from 24-d-old plants (approximately eight leaves expanded) using a syringe-suction method described by Beveridge et al. (1997a). Plants were decapitated below node 1 and sap was collected over a period of 1 to 2 h, usually yielding 100 to 200 μL per plant. Harvested shoot tissue and sap was frozen in liquid nitrogen and was stored at −80°C.

Auxin Extraction, Purification, and GC-MS-SIM Analysis

Frozen tissue (1–2 g) was extracted as described by Batge et al. (1999), except extracts were eluted from the C18 Sep-Pak cartridge (Waters, Rydalmere, Australia) with 10 mL of methanol:water (1:1). One hundred nanograms of [13C6]-IAA (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, UK) and 150 ng of [2H4]-4-Cl-IAA (Dr. Magnus, custom synthesis by MSD Isotopes, St. Louis) internal standard was added.

Purified samples were methylated and trimethylsilylated (at 80°C for 20 min), followed by GC-MS-SIM analysis as described by Ross (1998). For quantification of endogenous IAA and 4-Cl-IAA, the peak area ratio for the ion pair 202/208 and 236/240, respectively, was measured. Calculations were performed as described by McKay et al. (1994) and Magnus et al. (1997), taking into account the isotopic enrichment of the internal standard.

Cytokinin Extraction, Purification, and LC-MS-MS Analysis

The volume of xylem sap in each pool was estimated and 2 ng mL−1 of [2H5]-zeatin riboside ([2H5]-[9R]Z) (Apex Organics, Honiton, UK) was added as an internal standard. Sap extracts were reacted with 60 units of alkaline phosphatase (Sigma, St. Louis) for 2 to 3 h at 37°C. Subsequent analysis of [9R]Z, therefore, included [9R]Z and zeatin riboside 5′-monophosphate ([9R-5′P]Z). Following the phosphatase reaction, extracts were passed through a C18 Sep-Pak cartridge as described by Turnbull et al. (1997) and were then evaporated to dryness under vacuum. Immunopurification of cytokinins was performed as described by Faiss et al. (1997) except that preimmune and isoprenoid cytokinin immunoaffinity columns were also used (OlChemIM, Olomouc, Czech Republic). The samples were evaporated to dryness under vacuum.

LC-MS-MS analyses were performed largely as described by Prinsen et al. (1995) with the exception that [9R]Z was chromatographically separated using a 5-cm polar-linked triple endcapped Zorbax Bonus-RP column (5 cm × 2.1 mm id; 5-μm particle size; Hewlett-Packard, Australia) over a 5.3-min gradient from 5% (v/v) acetonitrile:ammonium acetate (0.01 m; 90:10, v/v) in ammonium acetate (0.01 m) to 100% (v/v) acetonitrile:ammonium acetate (0.01 m; 90:10, v/v) at a flow rate of 0.3 mL min−1. The HPLC system (Shimadzu LC-10AT binary gradient system) was connected to an API 3000 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (PE Biosystems, Thornhill, Canada) with an ion-spray (pneumatically assisted electrospray) interface used in positive ionization mode (ion spray potential 5500 V; orifice potential 35 V; ring potential 200 V; 30 eV collision energy). Quantitation was essentially as described by Prinsen et al. (1995), including correction for isotopic purity and application of the linear calibration curve.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Drs. John Ross and Greg Symons for GC-MS-SIM (auxin) analysis; Alun Jones for LC-MS-MS (cytokinin) analysis; and Rachael Eddy, Narelle Maugeri, Benjamin Morris, and Jai Perroux for technical assistance.

Footnotes

This work was funded by an Australian Research Council Large Grant, by an Australian Postgraduate Award (to S.E.M.), and by an Australian Research Council Fellowship (to C.A.B.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Arumingtyas EL, Floyd RS, Gregory MJ, Murfet IC. Branching in Pisum: inheritance and allelism tests with 17 ramosus mutants. Pisum Genet. 1992;24:17–31. [Google Scholar]

- Batge SL, Ross JR, Reid JB. Abscisic acid levels in seeds of the gibberellin-deficient mutant lh-2 of pea (Pisum sativum) Physiol Plant. 1999;105:485–490. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge CA. Long-distance signalling and a mutational analysis of branching in pea. Plant Growth Regul. 2000;32:193–203. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge CA, Murfet IC, Kerhoas L, Sotta B, Miginiac E, Rameau C. The shoot controls zeatin riboside export from pea roots: evidence from the branching mutant rms4. Plant J. 1997a;11:339–345. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge CA, Ross JJ, Murfet IC. Branching mutant rms-2 in Pisum sativum: grafting studies and endogenous indole-3-acetic acid levels. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:953–959. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.3.953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge CA, Ross JJ, Murfet IC. Branching in pea: action of genes Rms3 and Rms4. Plant Physiol. 1996;110:859–865. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.3.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge CA, Symons GM, Murfet IC, Ross JJ, Rameau C. The rms1 mutant of pea has elevated indole-3-acetic acid levels and reduced zeatin riboside content but increased branching controlled by graft-transmissible signal(s) Plant Physiol. 1997b;115:1251–1258. [Google Scholar]

- Beveridge CA, Symons GM, Turnbull CGN. Auxin inhibition of decapitation-induced branching is dependent on graft-transmissible signals regulated by genes Rms1 and Rms2. Plant Physiol. 2000;123:689–697. doi: 10.1104/pp.123.2.689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faiss M, Zalubilova J, Strnad M, Schmülling T. Conditional transgenic expression of the ipt gene indicates a function for cytokinins in paracrine signalling in whole tobacco plants. Plant J. 1997;12:401–415. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1997.12020401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo E, Turnbull CGN, Beveridge CA. Long-distance signalling and the control of branching in the rms1 mutant of pea. Plant Physiol. 2001;126:203–209. doi: 10.1104/pp.126.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C-J, Guevara E, Herrera J, Bangerth F. Effect of apex excision and replacement by 1-naphthylacetic acid on cytokinin concentration and apical dominance in pea plants. Physiol Plant. 1995;94:465–469. [Google Scholar]

- Magnus V, Ozga JA, Reinecke DM, Pierson GL, LaRue TA, Cohen JD, Brenner ML. 4-Chloroindole-3-acetic and indole-3-acetic acids in Pisum sativum. Phytochemistry. 1997;46:675–681. [Google Scholar]

- McKay MJ, Ross JJ, Lawrence NL, Cramp RE, Beveridge CA, Reid JB. Control of internode length in Pisum sativum: further evidence for the involvement of indole-3-acetic acid. Plant Physiol. 1994;106:1521–1526. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.4.1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murfet IC, Symons GM. Double mutant rms2 rms5 expresses a transgressive, profuse branching phenotype. Pisum Genet. 2000a;32:33–38. [Google Scholar]

- Murfet IC, Symons GM. The pea rms2-1 rms4-1 double-mutant phenotype is transgressive. Pisum Genet. 2000b;32:59–60. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli C, Beveridge CA, Snowden KC. Re-evaluating concepts of apical dominance and the control of axillary bud outgrowth. Curr Topics Dev Biol. 1999;44:127–169. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60469-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinsen E, Redig P, van Dongen W, Esmans EL, van Onckelen HA. Quantitative analysis of cytokinins by electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1995;9:948–953. [Google Scholar]

- Reid JB, Murfet IC, Potts WC. Internode length in Pisum: II. Additional information on the relationship and action of loci Le, La, Cry, Na and Lm. J Exp Bot. 1983;34:349–364. [Google Scholar]

- Ross JJ. Effects of auxin transport inhibitors on gibberellins in pea. J Plant Growth Regul. 1998;17:141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider EA, Kazakoff CW, Wightman F. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry evidence for several endogenous auxins in pea seedling organs. Planta. 1985;165:232–241. doi: 10.1007/BF00395046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Symons GM, Murfet IC. Inheritance and allelism tests on six further branching mutants in pea. Pisum Genet. 1997;29:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull CGN, Raymond MAA, Dodd IC, Morris SE. Rapid increases in cytokinin concentration in lateral buds of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) during release of apical dominance. Planta. 1997;202:271–276. [Google Scholar]