Abstract

Microcystis spp. threaten freshwater ecosystems through proliferation of cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (cyanoHABs) and production of the hepatotoxin, microcystin. While microcystin and its biosynthesis pathway, encoded by the mcy genes, have been well studied for over 50 years, a recent study found that Microcystis populations in western Lake Erie contain a transcriptionally active partial mcy operon, in which the A2 domain of mcyA and mcyB-C are present but the mcyD-J genes are absent. Here, we investigate the potential biosynthetic products and evolutionary history of this partial operon. Our results reveal two candidate tetrapeptide constructs, with an X variable position, to be produced by strains with the partial operon. The partial operon appears necessary and sufficient for tetrapeptide biosynthesis and likely evolved from a single ancestor hundreds to tens of thousands of years ago. Bioactivity screens using Hep3B cells indicate mild elevation of some markers of hepatotoxicity and inflammation, suggesting the need to further assess the effects of these novel secondary metabolites on freshwater ecosystems and public health. The need to assess these effects is even more pressing given detection of tetrapeptides in both culture and Western Lake Erie, which is a vital source of fresh water. Results from this study emphasize previous findings in which novel bacterial secondary metabolites may be derived from molecular evolution of existing biosynthetic machinery under different environmental forcings.

Keywords: Harmful Algal Blooms, Lake Erie, secondary metabolites, tetrapeptide, multi-omics

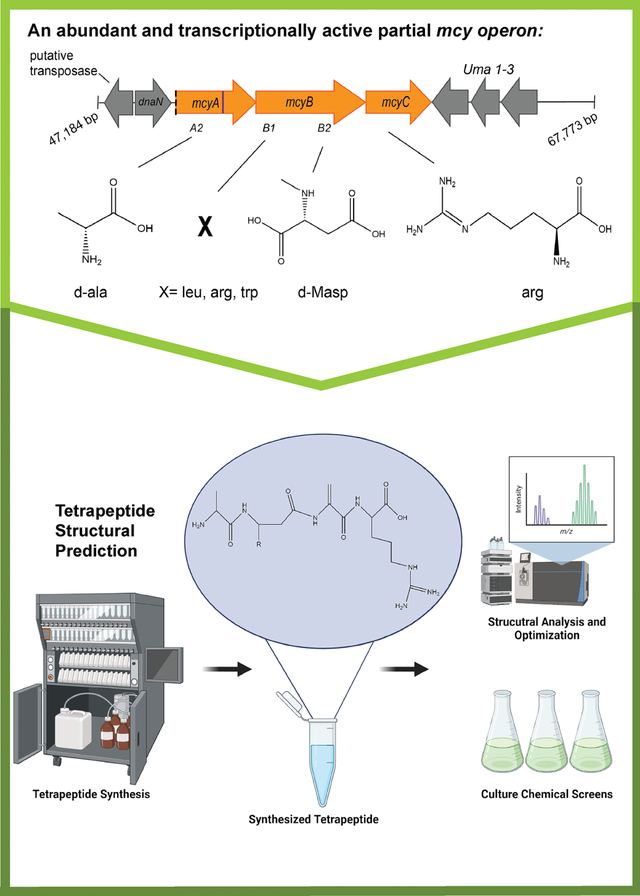

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Microcystin (MC), or the “fast-death-factor” was first identified in 19591 and is a potent hepatotoxin produced by cyanobacteria around the world within cyanobacteria harmful algal blooms (cyanoHABs)2–4. This cyanotoxin is responsible for the illness and death of humans5,6, as well as livestock including sheep, cows, and birds7,8. Dangerously high levels of MCs have also led to drinking water crises such as those in Toledo (USA) in 20149 and Wuxi (China) in 200710. While the toxicity of this molecule is caused via phosphatase inhibition11–13, its role in Microcystis and in natural communities remains elusive, with hypothesized functions including iron acquisition, grazer defense, allelopathy, oxidative stress protection, and others14.

MCs have been well studied over the last 50 years and account for about 90% of secondary metabolite research on cyanobacteria15. Following structural elucidation in the mid-1980s16, over 270 congeners have been identified2. To date, all characterized congeners are cyclic heptapeptides that derive from complete mcy operons in which at least 10 mcy genes (A-J) are present. Understanding congener diversity is important as slight structural changes can greatly impact potency and toxicity2,3. For example, a substitution from arginine in MC-LR to alanine in MC-LA results in significant increases in toxicity and lethality in mice 12.

The cyclic heptapeptide structure of MCs contains an unusual, non-proteinogenic amino acid, 3-amino-9-methoxy-2,6,8-trimethyl-10-phenyl- 4,6-decadienoic acid, (Adda)1,16,17, which is often the target for detection assays18. The X and Y positions are highly variable and can be substituted for various amino acids including leucine, arginine, tryptophan, and aspartic acid2. MCs are biosynthesized by a non-ribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS), polyketide synthase (PKS) multi-enzyme complex that contains hybrid NRPS-PKS, NRPS, tailoring, and ABC transporter modules19–21. Within Microcystis, this enzyme complex is encoded by the mcy gene cluster which consists of 10 genes and is about 55 kilobases in length19. Other cyanobacterial taxa are also known to produce MCs, and their biosynthetic machinery is largely the same as that in Microcystis, although there is some variation observed in gene cluster structure22. The genetic substructure of the mcy gene cluster is responsible, in part, for variation in congener production. For example, rearrangements, and point mutations in the highly dynamic mcyABC region can lead to the production of MC-LR, MC-RR, or congeners with demethylated Adda domains21,23. Complete loss of MC synthesis can also occur via transposable elements that cause insertions and deletions within the gene cluster 24,25.

Beyond genetic architecture of the mcy gene cluster, several other factors influence differential isoform production. The concentration and form of nitrogen influences production of congeners with N-rich amino acids26. Similarly, amino acid availability within the environment can also impact structure, particularly which amino acids are incorporated in the variable X and Y positions27. The C:N ratio of environmental nutrients affects congener production as well28. Finally, relaxed substrate binding specificity of the multi-enzyme biosynthetic complex allows for further variations of the MC structure23. While several factors influence the MC congener produced, the genes encoding its molecular assembly are valuable indicators of biosynthetic potential.

Recently, we detected a partial mcy genotype in which only the mcyA2 domain, mcyB, and mcyC genes are present29. This partial genotype is transcriptionally active, persistent across multiple years, and occasionally the most abundant mcy genotype in western Lake Erie cyanoHABs, suggesting that it is ecologically successful29. To our knowledge, only one axenic Microcystis culture is known to contains this genotype, PCC 9717 (NCBI Genbank: GCA_00312165.1), but the partial operon has also been detected in two xenic Microcystis strains isolated from western Lake Erie30. Here, based on the known biosynthetic pathway of MC, we predicted that the partial mcy genotype produces tetrapeptides (TPs), and tested this hypothesis by screening cultured Microcystis strains with varying mcy genotypes. We present evidence to support this hypothesis along with assessment of the evolutionary history of the partial haplotype and environmental occurrence and bioactivity of the tetrapeptide in terms of potential for hepatoxicity.

Materials and Methods

Partial Operon Annotation

The structure of the partial operon has previously been described and detected in the 2014 western Lake Erie cyanoHAB event29. To determine if culture isolates used within this study maintained the same genetic architecture observed in the field, several approaches were taken. The genome assembly of PCC 9717 (NCBI Genbank: GCA_00312165.1) was annotated with antiSMASH v. 631 to identify and annotate the partial operon and surrounding genes. Predicted amino acids from genes in the partial operon were aligned to the nonredundant protein database on NCBI using BLASTp32 to annotate proposed function and identity. Strains from the Western Lake Erie Culture Collection (WLECC)30, LE19–10.1 and LE19–251.1, were also annotated with antiSMASH v. 6, but due to poor assembly, the contiguous sequences containing partial mcy genes were fragmented and incomplete. To overcome limitations in assembly, paired end read mapping of WLECC strains onto the PCC 9717 partial operon and flanking genes was also completed to determine sequence structure and orientation using bbmap33 and visualized in Tablet v. 1.21.02.0834. Assembly statistics for PCC 9717, LE19–10.1, and LE19–251.1 are listed in Table S1. Additional alignments using BLASTn were completed to compare assembled genes found in WLECC strains and PCC 9717 and identify insertions or deletions. For both mapping approaches, a 95% identity and 80% alignment length cut off was used to count mapped reads. The singular top hit for each read was also mapped to prevent multimapping. In addition to mapping to PCC 9717, reads from LE19–10.1 and LE19–251.1 were mapped to the complete mcy operon from PCC 7806 (Genbank Accession: AF183408.1) to confirm the content and structure of this gene cluster (Fig. S1).

Structure Prediction and Chemical Synthesis

The product of the partial mcy operon was predicted based on the previously described biosynthesis pathways encoded in the complete mcy operon19,21,23. We hypothesized a tetrapeptide-construct to be the biosynthesis product of partial mcy operons based on the presence of mcyA2, mcyB and mcyC, all of which encode nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPSs), which are modular enzymes that incorporate amino acids into secondary metabolite structures35. The predicted product therefore was: Dala-X-DMAsp-Arg, where X= leucine (L), arginine (R), or tryptophan (Y) based on common MC congeners found in the 2014 western Lake Erie cyanoHAB9. TPs were chemically synthesized at the University of Michigan Proteomics and Peptide Synthesis Core. A summary of the 3 tetrapeptides including purity, molecular weight, and yield are summarized in Table S2.

Standard Optimization

Prepared TPs were analyzed using an online concentration HPLC triple quadrupole mass spectrometry method to detect and quantify in both field and culture samples. TP standards that were prepared as stated below and were analyzed on a Thermo TSQ Altis with an EQuan Max Plus system at the Lumigen Instrument Center at Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan, USA. The method used was a modified method from Birbeck et al. 201936. Briefly, the online concentration column was Hypersil GOLD aQ 20 × 2.1 mm, 12 μm, and the analytical column was an Accucore aQ 50 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm. The loading mobile phase for online concentration was 0.1% formic acid in MilliQ water and flowed at 1.5 mL/min during the injection of a 1 mL sample onto the column. Sample elution from the online concentration column onto the analytical column was completed using a gradient with 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B). The gradient flow was 0.5 mL/min, started at 10% B and was held for 1 minute. The gradient was increased from 10–50% B from 1–6.5 minutes, and then increased to 98% B from 6.51–7.5 minutes and brought down back to 10% B to equilibrate for the next injection. Mass spectrometer settings were the same as Birbeck et al., 201936.

Detection of the Tetrapeptide in Field Samples and Culture Isolates using HPLC/MS

Field data from the 2018 HAB Grab37 was screened for the detection of the TP constructs. This sample set was chosen based on the availability of samples for analysis. During the 2018 HAB Grab sampling period MC-RR and MC-LR were the most abundant MC congeners detected and were especially concentrated around the shoreline and shallow regions of the western basin with peak concentrations ranging from 8,000–12,000 ppt (Westrick and Birbeck, unpublished). For detection from the field, standard curves were generated for each tetrapeptide with a range of 0.5–500 part per trillion (ppt) for the LR and YR tetrapeptide and 50–500 ppt for the RR tetrapeptide. Both the particulate and dissolved fractions were analyzed for each sample as described above.

Select culture isolates of Microcystis from the WLECC, PCC, or NIES were also screened for the detection of the tetrapeptide constructs (Table 1). A variety of mcy genotypes were screened including the complete (all mcy genes present), the absent (no mcy genes present), the partial (mcyA2, mcyB-C present), and an mcyB knockout mutant (PCC 7806, ΔmcyB) to assess the necessity and sufficiency of the partial operon in tetrapeptide biosynthesis. Both axenic and xenic Microcystis isolates were screened for TPs to determine if the presence of associated bacteria, known to coexist with Microcystis in natural cyanoHABs, had impacts on biosynthesis. PCC and NIES strains were obtained from their respective culture collections, while WLECC strains were isolated from western Lake Erie and cultivated by the Geomicrobiology Lab at the University of Michigan30. A total of 11 Microcystis isolates were grown in BG11–2N38,39 at ~23°C (room temperature) and 40 μmol photons meter−2 second−1 on a 12:12 hour light:dark cycle. Cultures were transferred every 2 weeks to fresh media until sufficient biomass was accumulated (around 25 mL of dense culture). Cyanobacterial biomass was then collected onto GF/F filters (Whatman®, Maidstone, United Kingdom), and stored in at −80°C until mass spectrometry analysis could be completed as described in the section above. For detection in culture isolates, the limit of detection was 5 ppt for the YR construct, and 10 ppt for the LR and RR constructs.

Table 1:

Detection of the RR-tetrapeptide in Microcystis culture isolates from the Western Lake Erie Culture Collection (LE), Pasteur Culture Collection (PCC) or the National Intitute of Environmental Studies (NIES) ND indicates that the RR-tetrapeptide was not detected in that culture.

| Culture | RR tetrapeptide concentration (ppt) | mcy Genotype | Culture Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blank control | ND | - | - |

| BG-112N control | ND | - | - |

| MilliQ control | ND | - | - |

| LE19-251.1 | 946.98 | partial | xenic |

| LE19-10.1 | 4458.23 | partial | xenic |

| PCC 9717 | 2135.77 | partial | axenic |

| PCC 7806 ΔmcyB | ND | ΔmcyB | axenic |

| PCC 9806 | ND | absent | axenic |

| PCC 7005 | ND | absent | axenic |

| LE19-196.1 | ND | absent | xenic |

| PCC7806 | ND | complete | axenic |

| NIES-843 | ND | complete | axenic |

| LE18-22.4 | ND | complete | xenic |

| LE19-195.1 | ND | complete | xenic |

| Limit of Detection (ppt) | 10 | - | - |

Phylogenetic and Evolutionary Analysis of the Partial Haplotype

Several phylogenomic approaches were used to assess the evolutionary history of the partial haplotype. Nucleotide sequences for individual genes were aligned using MUSCLE40 as part of the MEGA11 workflow using default parameters. One thousand iterations were generated for each tree. Phylogenetic trees were reconstructed using MrBayes 3.2.7a, which implements Bayesian inference using Markov Chain Monte Carlo modeling approaches to reconstruct phylogenetic trees41. Sequences from the conserved mcyA region as well as the mcyB region were used for analysis. mcyC was omitted due to poor assembly quality from WLECC strains. For both mcyA and mcyB, consensus trees and time of divergence trees were reconstructed. In reconstructions of time of divergence trees, the substitution rate in MrBayes was calibrated based on previously estimated mutation rate for the intergenic spacer sequence (ITS) region.42 Based on consensus trees, in which the partial haplotypes were observed to be monophyletic, we pre-specified the partial haplotypes to form a monophyletic group in the time of divergence trees, which assumes that a single ancestor underwent a deletion event, in which the partial haplotype was the result. This was verified by confirming sequences upstream and downstream of the partial operon in PCC 9717, LE19–251.1 and LE19–10.1 were conserved, as these are the only publicly available strains with this genotype, as evidenced by read mapping of WLECC strain reads onto the PCC 9717 assembly of the partial operon (Table S3). In addition to single gene analyses, the same phylogenomic approaches were used on concatenated mcyA and mcyB sequences (from isolates in which these genes were assembled completely), since adjacent genes are expected to have the same evolutionary history. For all trees mcy sequences from Planktothrix agardhii NIVA-CYA 126/8 (Genbank Accession: AJ441056.1) and Anabaena sp. 90 (Genbank Accession: AY212249.1) were used as outgroups. A complete list of Genbank Accession identifiers for sequences used in phylogenomic analysis can be found in Table S4.

Bioassay Screening for Antibacterial Activity and Cytotoxicity

Bioassays were conducted to test for antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and for cytotoxicity against SW48 and HCT15 (both colorectal cancer) cell lines. In preparation for bioassay screening, stock solutions of each TP were suspended in DMSO for a final concentration of 10 mM, and stored at −20°C until use. HCT15 (CCl-225) and SW-48 (CCL-231) cells were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All cell lines were Mycoplasma free and independently authenticated by short tandem repeat profiling, performed by ATCC. Cells were grown and culture according to ATCC recommendations. HCT15 cells were cultured in RPMI1640 (30–2001) supplemented with 10% FBS (30–2020). SW48 cells were cultured in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (30–2008) containing 10% FBS. SW-48 cells were grown and treated in an incubator set for atmospheric conditions (no supplemental CO2 addition). For cell-based assays, cells were expanded and frozen into single use aliquots. For each assay cells were thawed at 37°C for 1 minute and then immediately re-suspended into 10ml of complete growth medium. Cells were then spun down at 300Xg for 5 minutes and then resuspended into cell specific growth medium and plated at 2,500 cells per well into Greiner 781080 white cell culture 384-well plates with total volume per well at 40ul. Natural product extracts or fractions were dissolved in DMSO at 15mg/ml and delivered into the assay plates using Echo 655 acoustic liquid handler instrumentation (Beckman Coulter). Extract and fraction testing concentrations were at 0.25%. For primary screening assays extract testing was performed n=1 at 0.25% final extract testing concentration (where original fraction is defined at 100%). Validation assay and fraction studies were performed in triplicate at similar testing concentrations. Negative controls medium only plus matching 0.25% DMSO were included in columns 1 and 2. The positive control for these studies was a 10uM treatment with staurosporine in columns 23 and 24 of each assay plate. On each plater samples were interrogated in wells A03 to P22. The high throughput data software Mscreen was utilized for primary hit, validation selection and for analysis of concentration response curve results (1). Following compound addition, cells were cultured for 48 hours at either 5% CO2 at 37°C for HCT15 cells or atmospheric air at 37°C for SW-48 cells. Cell viability was measured using a CellTiter-Glo luminescent kit (catalog no.G7571) from Promega as directed using a PHERAstar instrument from BMG Labtech.

Hep3B Cells

Human hepatocellular carcinoma Hep3B (liver epithelial) cells were acquired from ATCC (Cat. No. HB-8064, ATCC, VA, USA). The cells were grown in the recommended EMEM media (Cat. No. 30–2003, ATCC, VA, USA) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Cat. No. FBS-BBT, Rocky Mountain Biologicals, Montana, USA,) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin solution (Cat. No. PSL01–100ML, Caisson Labs, UT, USA,). The cells were grown and maintained in T-75 culture flasks incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2. For the purposes of experiments, the cells were grown and treated in 6-well plates.

Hep3B Cell Line Exposures to MCs and Tetrapeptides

After seeding the cells in 6-well plates and reaching the desired confluency, the FBS containing growth medium was replaced with 1 ml/well of serum-free media followed by incubation at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3 hrs. For exposure to the tetrapeptides and their appropriate controls, lyophilized MC-LR (Cat. No. 10007188, Cayman Chemicals, MI, USA) was dissolved in 1 ml of Ultrapure Distilled water (Cat. No. 10977–015, Invitrogen, MA, USA) to obtain a stock concentration of 1 mg/ml. For the experiment, the cells were treated with a final concentration of 1 or 10 μM of MC-LR. Similarly, lyophilized MC-RR (Cat. No. 10007868, Cayman Chemicals, MI, USA) was dissolved in 1 ml of Ultrapure Distilled water to obtain a stock concentration of 100 μg/ml and the cells were treated with a final concentration of 1 and 10 μM MC-RR exposure. For both tetrapeptide exposures, the above-mentioned 10 mM tetrapeptide stocks were diluted to 1000 μM working stocks using Ultrapure Distilled water and the cells were treated with a final concentration of 1 or 10 μM. An irrelevant control peptide (~20 amino acids) was used as a negative control at the same concentration as the tetrapeptides and full-length MCs and cells were collected at 6 and 24 hours after exposure. After the exposures, the cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 for appropriate time before proceeding to further experimental analysis.

RNA extraction and RealTime – PCR analysis

RNA was extracted from the cells using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Cat. No. 74136, Qiagen, MD, USA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA quality and purity was confirmed using nanodrop to measure 260/280 ratios and 260/230 ratios, which fell between the acceptable range indicating RNA purity. Approximately 500 ng of the extracted RNA was taken further to synthesize cDNA using QIAGEN’s RT2 First Strand Kit (Cat. No. 330401, Qiagen, MD, USA). Automated liquid handling workflow system QIAgility (for qPCR sample and reagent loading) was used as described previously43,44. The reaction set up using the automated liquid handling system QIAgility is described in Table S5. All samples were run in duplicate. qPCR was performed using Qiagen Rotor-Gene Q thermo-cycler. The cycle threshold values obtained in the process were used to calculate the fold change in the gene expression. 18S rRNA (Cat. 4319413E, Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as a housekeeping gene for normalization. The following Taqman primers obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific were used to assess hepatotoxicity in Hep3B cells: Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1 aka SerpinE1) (Hs00167155_m1), Alkaline Phosphatase (ALPL) (Hs01029144_m1), and Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (Tgf-β1) (Hs00998133_m1). The program settings for the qPCR runs are described in Table 2.

Table 2:

qPCR machine cycle settings for inflammation and hepatoxicity studies

| Temperature (°C) | Time (seconds) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Denaturation | 95 | 300 (5 min) | ||

| Cycling | Denature | 95 | 30 | 40x |

| Annealing | 60 | 90 | ||

| Extension | 72 | 30 | ||

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad PRISM 7 software (San Diego, CA, USA). For comparisons involving >2 groups, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed along with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc tests where applicable. All the data are presented as Mean ± Standard Error of Mean (S.E.M.) and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The Partial mcy Gene Cluster

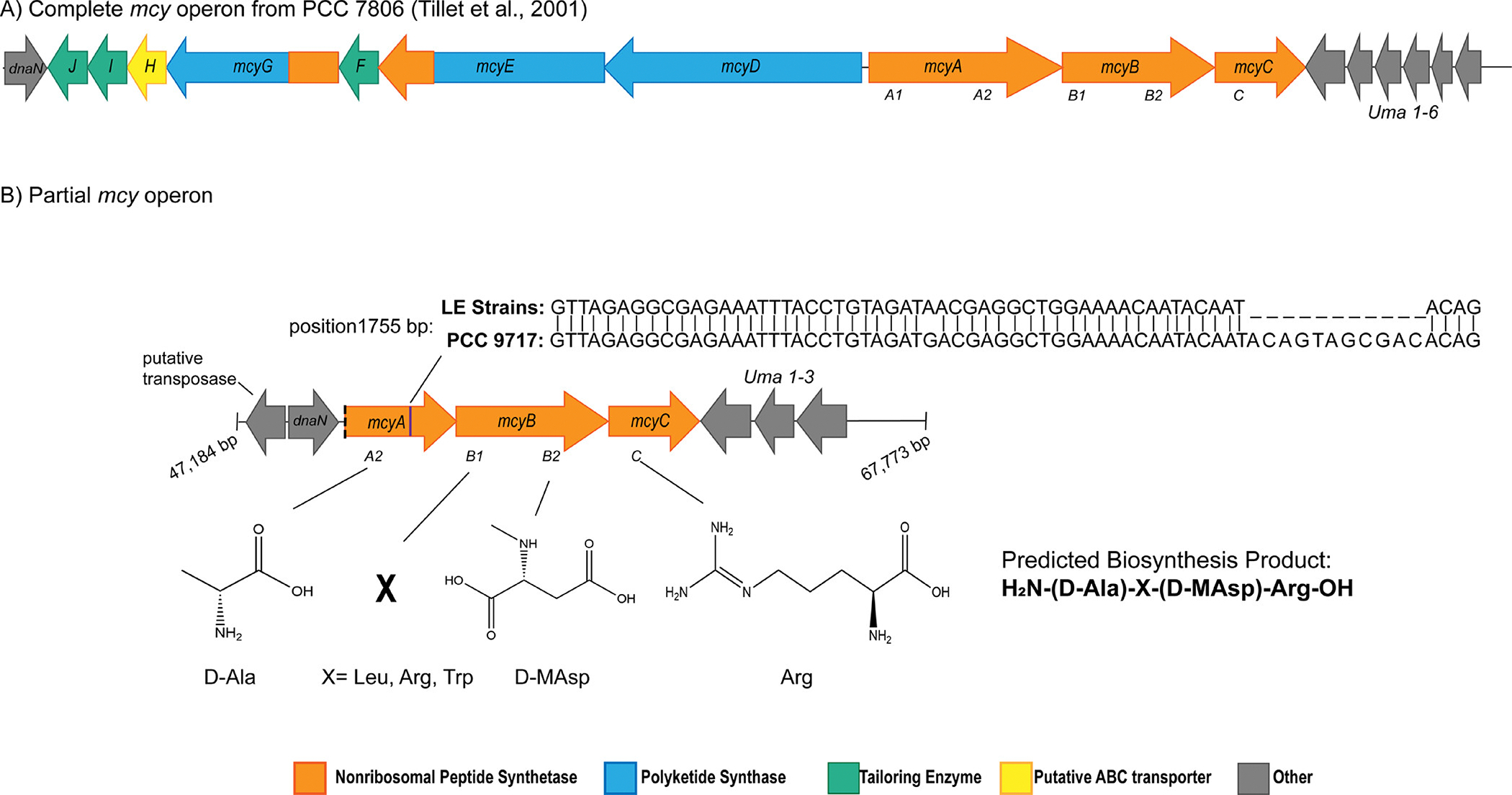

The partial mcy gene cluster, which was previously described in western Lake Erie cyanoHABs29, differs from the complete mcy operon (Fig. 1A) as it lacks mcyD-J, and the A1 domain of mcyA (Fig. 1B). The intact partial operon, which encodes NRPS enzymes, was hypothesized to incorporate four amino acids into a tetrapeptide molecule based on the known biosynthesis pathway in the complete mcy operon2,19. This tetrapeptide is predicted to contain a D-alanine (D-Ala), via the mcyA2 domain, an X variable amino acid (Leu, Arg, Trp) via the mcyB1 domain, N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (D-MAsp) via the mcyB2 domain, and an arginine via mcyC (Arg) (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1:

Gene schematics for A) the complete mcy operon and neighboring genes in Microcystis aeruginosa PCC 7806 (Genbank Accession: AF183408.1) which is known to encode the biosynthesis of microcystin, and B) the partial mcy operon. Based on the presence of conserved domains in gene mcyA-C, a tetrapeptide construct is the predicted biosynthesis product of this partial operon consisting of d-ala, an X variable position that may contain leu, arg, or trp, d-Masp, and arg. The partial operon is detected in PCC 9717 (NCBI Genbank: GCA 00312165.1), LE19–251.1 and LE19–10.1. These sequences are highly conserved, with an 11 bp insertion observed in mcyA in PCC 9717 at position 1755 bp. The partial operon is found on a contiguous sequence that is over 70,000 base pairs in length in PCC 9717. The 2 genes downstream of the partial operon include dnaN which encodes a DNA polymerase III beta subunit and a putative transposase. The 3 genes upstream of the partial operon putatively encode uma1–3.

The partial mcy operon has been identified in culture isolates PCC 9717, LE19–251.1, and LE19–10.1, the latter two being isolated from western Lake Erie29,30,45. Currently, the partial mcy operon has only been detected in these 3 publicly available culture isolates. The order and structure of genes in the partial operon is conserved with the complete operon as evidenced by complete assembly in PCC 9717 and paired end read mapping for LE19–251.1 and LE19–10.1 onto the complete mcy operon from PCC 7806 and flanking genes (Fig. 1B, Fig. S1, Table S1). The mcy gene sequences in the partial operons of these strains share 99–100% sequence identity at the nucleotide level. An 11 base pair insertion at position 1793 of the mcyA gene of PCC 9717 is not present in the western Lake Erie strains (Fig. 1B, Table S6). Complete assembly of the partial operon and neighboring genes within PCC 9717 reveals the presence of several flanking genes that are also adjacent to the complete mcy operon19; we identified uma1–3 genes upstream of mcyC and dnaN, which encodes a DNA polymerase III beta subunit, downstream of the truncated mcyA. We also identified a putative transposase adjacent to dnaN (Fig. 1, S1, and Table S7).

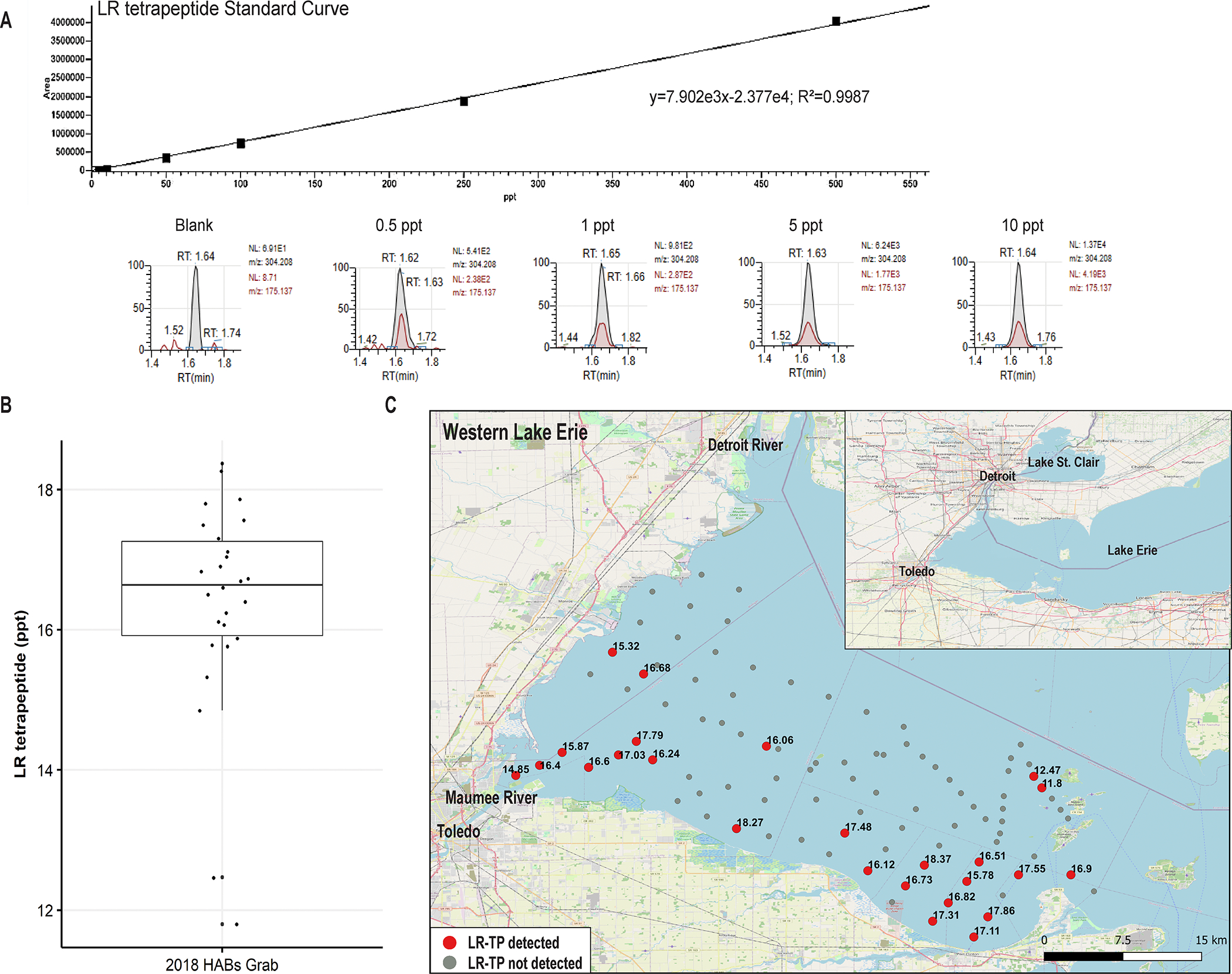

Detection of Tetrapeptides in Western Lake Erie

The three synthesized TP constructs were quantified in western Lake Erie samples (see Materials and Methods, Table S2, S8, Fig. 2A). The LR-tetrapeptide was detected in samples collected from western Lake Erie during the 2018 HABs Grab, a binational sampling effort aimed at resolving high spatial resolution during a single day37. Of the 123 samples collected during sampling, 29 had detectable amounts of the LR-tetrapeptide ranging from about 12–19 ppt (Fig. 2B, 2C, limit of detection=0.5 ppt). The LR-tetrapeptide was detected in samples largely along the southern coast of Ohio, with little detection in the center of the western basin (Fig. 2C). Detection only occurred in particulate fraction with microbial biomass, not in the dissolved filtrate fraction, providing evidence that the tetrapeptide is intracellular and suggesting it is a biosynthesis rather than degradation product. The partial genotype was detected in 5 of 26 available metagenomes from the HABs Grab, but at low levels of relative abundance29,37 (Table S8), which may explain low concentrations of the detected LR-tetrapeptide compared to concentrations of microcystin L,R (8,000–12,000 ppt, Zastepa et al., 2024, accepted at AEHM).

Figure 2:

Detection of the LR-tetrapeptide during the 2018 HAB Grab using HPLC/MS. A) Standard Curve for the LR tetrapeptide for quantification in HAB Grab 2018 samples. Various concentrations of the LR tetrapeptide (blank, 0.5 ppt, 1 ppt, 5 ppt, 10 ppt,) demonstrate accurate quantification of the LR tetrapeptide at the lowest reported values (~12 ppt). The retention time for the LR tetrapeptide was 1.62–1.65 minutes. B) Quantification of the LR tetrapeptide from 29 HAB Grab Samples, ranging from around 12–19 ppt. C) Map of western Lake Erie with sample points where the LR tetrapeptide (TP) was detected. Samples in which the LR-TP were detected are colored red. Concentrations at each time point are denoted in ppt. Samples where the tetrapeptide was not detected are colored gray. The Open Street Map [OSM] was used as the basis for the rendered map (https://wiki.osmfoundation.org/wiki/Main_Page).

Detection of Tetrapeptides in Culture Isolates

Culture isolates were screened for TP constructs to determine if the partial operon can be attributed with their biosynthesis. Of all the isolates screened, the RR-tetrapeptide was only detected in strains containing the partial operon genotype, regardless of culture status (axenic vs. xenic). We did not detect the LR- or YR-tetrapeptide from any of the culture isolates (Table 1). The concentration of the RR-tetrapeptide was high compared to field samples, ranging from 946.98–4458.23 ppt (Table 1, limit of detection=10 ppt). Based on the presence of the RR-tetrapeptide in cultures only containing the partial operon, these results suggest this genotype is necessary and sufficient for tetrapeptide biosynthesis. This result provides evidence that the tetrapeptide is a synthesis product and not a degradation product of complete microcystin molecules.

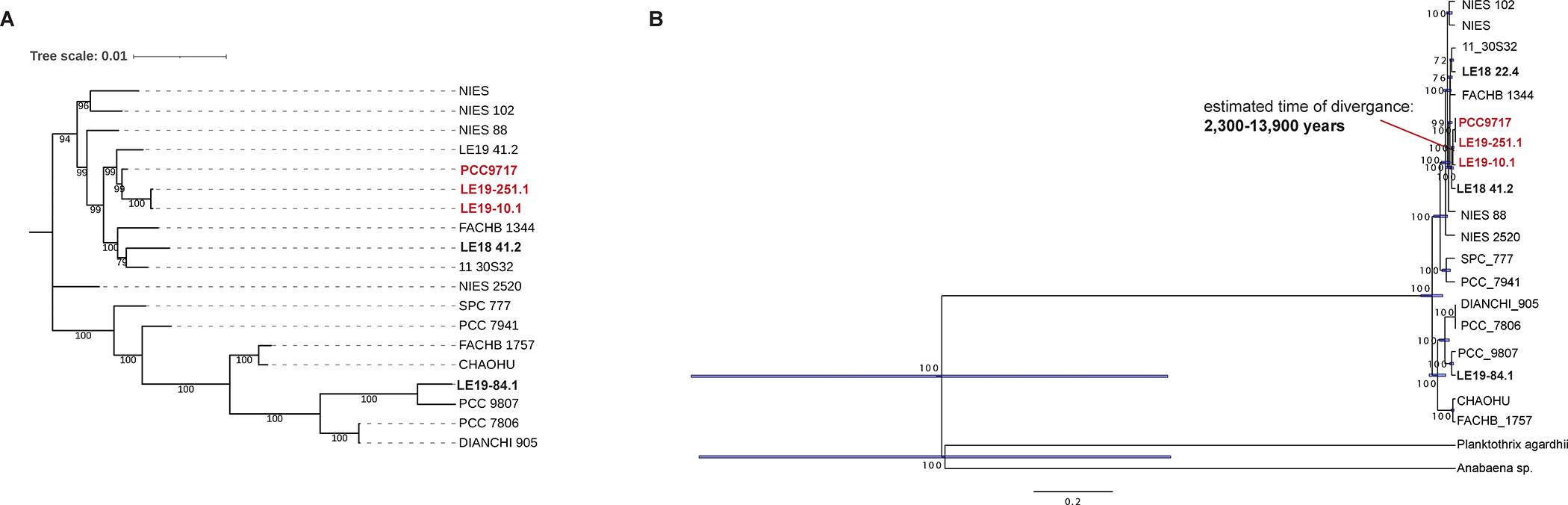

Phylogenomic and Evolutionary Analysis of the Partial Haplotype

To investigate the evolutionary history of the partial mcy gene cluster, various phylogenomic approaches were used to compare its relatedness to complete gene cluster sequences and estimate time of divergence. Due to the lower quality of assemblies from WLECC strains30, concatenated mcyA and mcyB sequences were analyzed as well as individual mcyA and mcyB genes, while mcyC was omitted. Consensus trees for concatenated genesconcatenated genes reveal that the partial haplotype sequences are found within monophyletic groups (posterior probability = 99), suggesting a shared deletion event in the common ancestor of the three strains (Fig. 3A). Observed differences in clustering based on mcyA and mcyB sequences may be explained by the dynamic and mosaic nature of this region of the mcy operon23, especially in mcyB where known recombination and replacements of entire domains have been observed21.

Figure 3:

Phylogenomic analyses of conserved sequences in the complete and partial haplotypes using concatenated mcyA and mcyB sequences from both the WLECC and publicly available Microcystis isolate genomes. Isolates with the partial gene cluster are bolded and red, while isolates from the WLECC with the complete operon are bolded and black. A) The tree on the left is a consensus tree constructed by MRBAYES. Posterior probabilities are shown at each node. B) The tree on the right represents time of divergence generated by MRBAYES. Based on the time tree and rate dating the partial haplotype diverged thousands of years ago from the complete haplotype. The red line points to the node representing the last common ancestor shared between strains with the complete or partial haplotype. To generate both trees, 1000 iterations were completed, and Planktothrix agardhii NIVA-CYA 126/8 (Genbank Accession: AJ441056.1) and Anabaena sp. 90 (Genbank Accession: AY212249.1) were used as outgroups. Note: outgroups have been hidden on consensus trees.

Time trees reveal that estimated times of divergence between the complete and partial haplotype range from hundreds to tens of thousands of years based on which sequence was analyzed. These trees were built on the assumption that the deletion happened once within a common ancestor, which is corroborated by conserved flanking regions on either end of the partial mcy operons in all three strains with this genotype (Fig. 1, Table S3, S4). For the mcyA sequence, estimated time of divergence between the complete and partial haplotype was calculated to be about 3,400 to 31,700 years ago (Fig. 3A). For the mcyB sequence, estimated time of divergence was determined to be 100–14,300 years ago (Fig. 3B). The variation in divergence times inferred from mcyA and mcyB may be explained by different rate of substitution or recombination between the two genes21,23. These estimations are in agreement with previous calculations of times of divergence based on upper and lower limits of observed bacterial mutation rates29.

Bioassay Screens to Assess Activity

Bioassays to test for antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), as measured by growth inhibition, and for cytotoxicity against SW48 and HCT15 cell lines, were both negative (data not shown).

Tetrapeptide MC-RR shows a mild hepatotoxic response in Hep3B cells

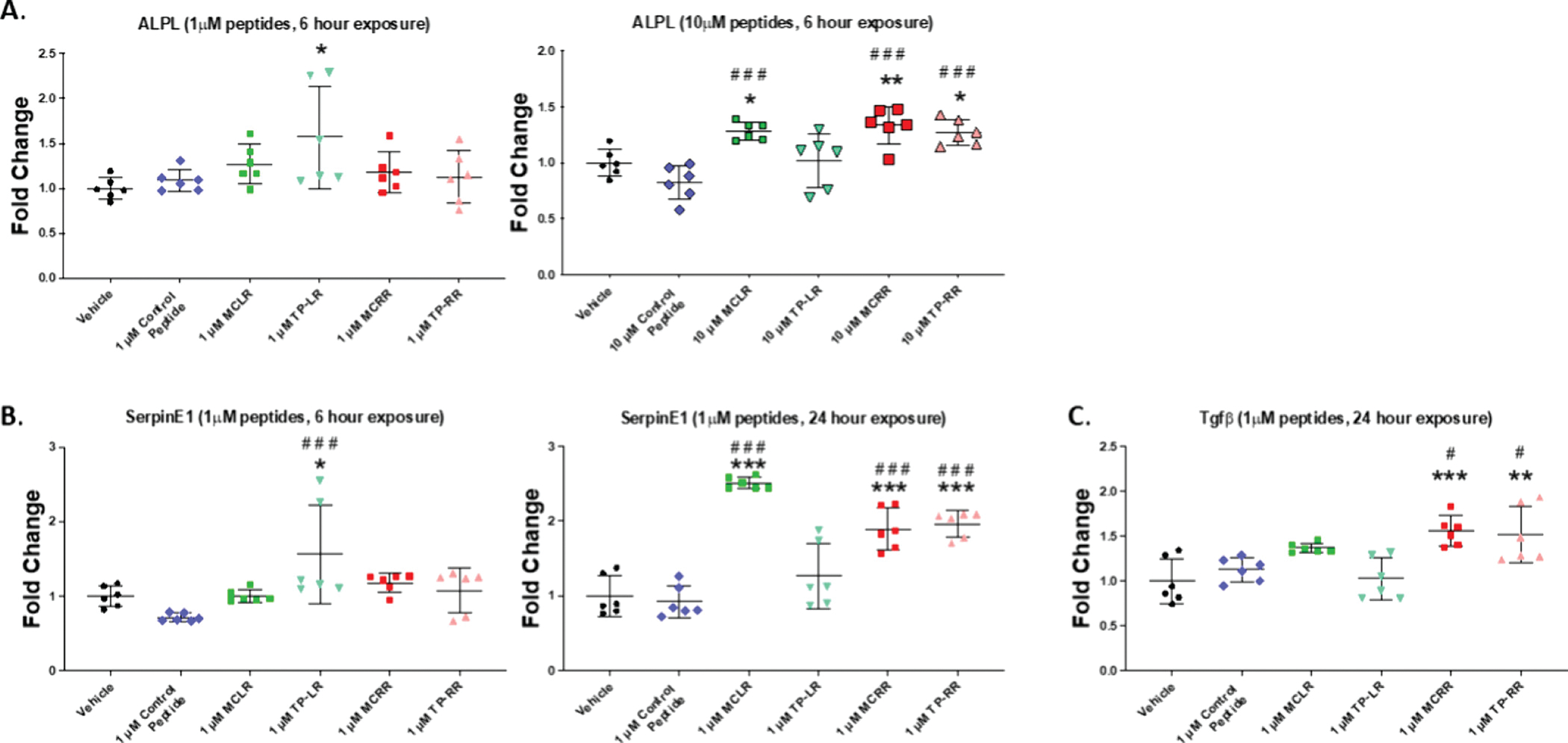

In order to screen for potential hepatotoxic effects of the LR and RR tetrapeptides, Hep3B human hepatocellular carcinoma cells were exposed to the TPs (as well as their full-length MC-LR and MC-RR counterparts) at 2 doses (1 and 10 μM) for either 6 or 24 hours and compared with both vehicle (water) and irrelevant peptide controls (Fig. S2). Quantitative PCR analysis was performed for markers of hepatotoxicity including PAI-1/SerpinE1, ALPL,and Tgfβ1 (Fig. 4A–C). After 6 hours of exposure, TP-LR (1 μM) exhibited significant increases in both ALPL (Fig. 4A) and SerpinE1 (Fig. 4B), while TP-RR (10 μM) exhibited significant increases in ALPL (Fig. 4A) relative to both vehicle and control peptide. After 24 hours of exposure, TP-RR (1 μM) exhibited significant increases in both SerpinE1 (Fig. 4B), and Tgfβ1 (Fig. 4C) relative to both vehicle and control peptide.

Figure 4:

Quantitative PCR analysis of markers of hepatotoxicity in Hep3B cells after exposure for either 6 hours or 24 hours to the indicated concentrations of microcystin tetrapeptides (TP), or full length microcystins vs vehicle (water) or irrelevant peptide controls. A) Alkaline Phosphatase (ALPL) expression after 6 hour exposure to 1μM (left) and 10 μM (right) of indicated peptides B) Plasminogen Activator Inhibitor-1 (PAI-1 aka SerpinE1) expression after 6 hour (left) and 24 hour (right) exposure to 1 μM of indicated peptides and C) Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (Tgf-β1) expression after 24 hour exposure to 1 μM of indicated peptides; *p≤0.05, ** p≤0.01, ***p≤0.001vs vehicle; #p≤0.05, ## p≤0.01, ###p≤0.001 vs control peptide.

Discussion

Our findings provide evidence that a tetrapeptide construct is biosynthesized from transcriptionally active partial mcy operons that have been observed in both field and culture samples29,30. These results challenge the notion that modified mcy gene clusters, either through insertion of transposable elements or deletion of entire genes, are non-functional24,25,46, transient artifacts of genome streamlining47–49. While the RR tetrapeptide was exclusively detected in culture, the LR tetrapeptide was detected only in the field, and the YR tetrapeptide was not detected at all, these results highlight the possibility for truncated mcy products to be biosynthesized under different conditions when varying substrates are available. The functional role and direct biomolecular target(s) of the tetrapeptide has yet to be established, and available field data on its environmental distribution is limited. However, these findings suggest the potential for a novel secondary metabolite to influence observed community dynamics within cyanoHABs where strains with the partial operon are present.

Interestingly, we only detect the LR tetrapeptide in the field and only the RR tetrapeptide in culture. This may be due to different substrates available in the natural freshwater environment versus nutrient replete culture media. During the 2018 HAB Grab in which the LR tetrapeptide was detected (Fig. 2), total nitrogen measurements at the time of sampling were comparatively lower to other bloom years9,29,37. Cultures in which the RR tetrapeptide was detected were grown in nutrient replete BG-112N, which contains 2 mM of NaNO338,39. Differences in available nitrogen may explain the incorporation of N-rich arginine into tetrapeptide constructs grown in culture compared to N-poor leucine in tetrapeptides detected in the field26–28,50.

The presence of additional variants of the tetrapeptide cannot be ruled out. LR, RR, and YR tetrapeptides were chosen for chemical synthesis as these were the most abundant complete MC congeners produced in western Lake Erie during the 2014 bloom9. However, in more recent blooms in western Lake Erie, the most abundant MC congeners have been LR, RR, and LA, while YR is in much lower abundance51. These recent trends, and the known diversity of MC congeners2, highlights the possibility of other tetrapeptide constructs to be biosynthesized. Future studies should consider the possibility of tetrapeptide constructs with LA in the X and Z variable positions as it has become more abundant in western Lake Erie blooms37,51, and complete MC-LA has been shown to persist longer in surface waters and has similar toxicity as MC-LR52.

Another need for future investigation is the source of D-MeAsp, which is part of the tetrapeptide construct (Fig. 1B). Previous work determined that an Asp racemase, encoded by mcyF, is necessary to switch the stereochemistry of the MeAsp from L to D conformation53,54. mcyF encodes the only known aspartate racemase in Microcystis genomes53, and it is lacking from strains with the partial genotype (Fig. 1B). Racemases encoded elsewhere in Microcystis genomes, outside of the mcy operon, may provide D-glutamate for complete MC biosynthesis54. However, searches for mcyF homologs in genomes that contain the partial genotype do not return any hits (data not shown), suggesting these strains lack aspartate racemases altogether, although novel isomerases cannot be ruled out. Alternatively, D-amino acids for tetrapeptide biosynthesis may be obtained exogenously from the environment, potentially through exometabolite exchange, as commonly observed in microbial communities55–57. However, it is unknown if Microcystis contain specific transporters for this function. If such transporters exist, this mechanism is feasible given that partial operon genotypes co-occur with Microcystis strains that have complete mcy operon, including the mcyF racemase in Western Lake Erie Blooms29.

Phylogenomic analysis, based on genes sequences of mcyA and mcyB, and conservation of flanking genes in strains with the partial operon provide evidence that this deletion occurred once in a common ancestor, hundreds to thousands of years ago, and has persisted through time (Fig. 3, Table S3). This is further supported by the fact that the partial operon was observed in western Lake Erie cyanoHABs from 2014 and 201829,30 and in PCC 9717, which was isolated from a water dam in Rochereau, La Vendée, France in 1996 (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France). It is well-established that the evolution and modification of biosynthetic gene clusters can give rise to new biosynthesis pathways and secondary metabolites. For example, the nodularin biosynthesis pathway is believed to be derived from the mcy operon via deletions of the second domain in mcyA and the first domain in mcyB and fusion of remaining modules into a singular gene, ndaA22,58. Horizontal gene transfer, mutation, and recombination of biosynthetic gene clusters59,60, along with evolutionary pressures due to limited pools of substrates in natural communities, may explain the modification and diversification of produced secondary metabolites that share similar evolutionary routes22,59.

While the deletion event in the partial operon was substantial, eliminating over half of the genes needed for complete MC biosynthesis, it’s persistence through time, transcriptional activity in the field29, and detection of proposed biosynthesis products provide evidence that the partial operon is functional and benefits fitness. Although the functional role of complete MCs is complex and likely multi-facted14, the partial operon may encode a truncated microcystin-like molecule that serves as a critical function in changing environments. One explanation for this functional intermediate is the tradeoff between producing N-rich MCs over none at all under deplete conditions. Environmental stress, including nitrogen limitation, has previously been shown to select for gene loss and genome streamlining in bacteria in marine systems, especially genes related to nitrogen metabolism61,62. The partial operon has been shown to dominate blooms in the late season in western Lake Erie, when bioavailable N is considerably lower29,37, suggesting a functional role under environmental stress and nitrogen limitation.

We evaluated the biological activity of the tetrapeptides using Hep3B cells, a cell line derived from human hepatocellular carcinoma and a well-established screening model for drug toxicity. Our preliminary studies showed that a final concentration of 10 μM could elicit a significant hepatotoxic response from the full-length MCs without affecting the viability of the cells and thus we assessed potential hepatotoxicity after short term (6 hours) and long term (24 hours) exposure of both low (1 μM) and high (10 μM) dose of the tetrapeptides. Previous work has demonstrated that microcystins effectively target and inhibit protein phosphatases 1 and 2A, although structural differences in congeners have varied effects on protein phosphatases.63 Hepatotoxicity was assessed by gene expression of several common markers identified in previous studies including SerpinE1, ALPL, and Tgf-β143,63. Results of this analysis demonstrated that both tetrapeptide-LR and tetrapeptide-RR showed mild but significant upregulation of these markers, albeit with slightly different dose and time points. It should be noted that the tetrapeptides did not appear to have a standard dose and time dependent relationship with the various markers of cytotoxicity. Interestingly, we and others have observed a similar trends with full length MC congeners wherein increases in the toxin concentration did not translate to an increase in the genetic expression of hepatotoxicity markers or the associated enzymatic activity of common hepatic injury enzymes such as alkaline phosphatase, but in some cases there was actually a suppression of this phenotype64,65. Based on these studies, and the fact that the putative target of these toxins are ubiquitous protein phosphatases which control a wide spectrum of cellular processes, further study is warranted to understand the exact mechanism whereby MC tetrapeptides may exert their cytotoxic effects. The fact that these effects were noted in the absence of the ubiquitous Adda domain in full length microcystin congeners suggests the need to characterize the impact of the tetrapeptides more thoroughly and other potential tetrapeptide congeners on both aquatic ecosystems as well as human and animal health as they may have the potential to alter protein phosphatase activity.

Results from this study highlight the dynamic nature of biosynthetic gene clusters encoded in Microcystis genomes, and that pathways that have been well studied for over 30 years are still rich sources for discovery, particularly through the use of multi-omic approaches. To our knowledge, these findings provide the first evidence of a tetrapeptide biosynthesis product from the partial mcyA-C gene cluster. Future work is needed to further assess bioactivity, as preliminary results suggest the potential for some tetrapeptide congeners to exhibit mild levels of hepatoxicity. Further screens will help determine threats to ecosystem function and access to clean drinking water. Additional work should also screen for the presence of the partial operon in Microcystis dominated cyanoHABs around the world to assess its presence and persistence on a global scale.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis.

Results presented here provide evidence for the production of a broader class of microcystin-related molecules that may negatively impact freshwater ecosystems, harmful algal bloom persistence, and public health.

Acknowledgements

We thank Robert Hein for the bioinformatic support. We thank Henriette Remmer for assistance in chemical synthesis of the tetrapeptides at the Proteomics and Peptide Synthesis Core at the University of Michigan. We thank McKenzie Powers, Katherine Polik, and Helena Nitschky for assistance in culturing and maintenance of the WLECC.

Funding

This work was supported by NIH and NSF awards to the Great Lakes Center for Fresh Waters and Human Health (NIH: 1P01ES028939–01, and 2P01ES028939–06; NSF: OCE-1840715 and OCE-2418066), the NOAA Great Lakes Omics program distributed through the UM Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research (NA17OAR4320152 and NA22OAR4320150., and the Hans W. Vahlteich Professorship. This material is based upon work supported by the U.S. Geological Survey under Grant/Cooperative Agreement No G23AC00555–00. Support was also provided by UM Natural Products Biosciences Initiative, the NOAA OAR Ocean Technology Development Initiative, and NIEHS 1R01ES034017. In addition, his research was funded by a Harmful Algal Bloom Research Initiative grant from the Ohio Department of Higher Education, the David and Helen Boone Foundation Research Fund, and the University of Toledo Women, and the Philanthropy Genetic Analysis Instrumentation Center. Support was also provided from the Center for urban Response to Environmental Stressors (CURES, NIEHS P30 ES036084, and 1R01ES034017)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

CEY was a graduate student at the time this research was completed, but is currently employed at New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA.

References

- (1).Bishop CT; Anet EFLJ; Gorham PR Isolation and Identification of the Fast-Death Factor in Microcystis Aeruginosa NRC-1. https://doi.org/10.1139/o59–047 1959, 37 (3), 453–471. 10.1139/O59-047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Bouaïcha N; Miles CO; Beach DG; Labidi Z; Djabri A; Benayache NY; Nguyen-Quang T Structural Diversity, Characterization and Toxicology of Microcystins. Toxins 2019, 11 (12), 714. 10.3390/toxins11120714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Díez-Quijada L; Prieto AI; Guzmán-Guillén R; Jos A; Cameán AM Occurrence and Toxicity of Microcystin Congeners Other than MC-LR and MC-RR: A Review. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2019, 125, 106–132. 10.1016/j.fct.2018.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Harke MJ; Steffen MM; Otten TG; Wilhelm SW; Wood SA; Paerl HW A Review of the Global Ecology, Genomics, and Biogeography of the Toxic Cyanobacterium, Microcystis Spp. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 4–20. 10.1016/J.HAL.2015.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Jochimsen EM; Carmichael WW; An J; Cardo DM; Cookson ST; Holmes CEM; Antunes MB; de Melo Filho DA; Lyra TM; Barreto VST; Azevedo SMFO; Jarvis WR Liver Failure and Death after Exposure to Microcystins at a Hemodialysis Center in Brazil. New England Journal of Medicine 1998, 338 (13), 873–878. 10.1056/nejm199803263381304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Pouria S; De Andrade A; Barbosa J; Cavalcanti RL; Barreto VTS; Ward CJ; Preiser W; Poon GK; Neild GH; Codd GA Fatal Microcystin Intoxication in Haemodialysis Unit in Caruaru, Brazil. Lancet 1998, 352 (9121), 21–26. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)12285-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Carbis CR; Simons JA; Mitchell GF; Anderson JW; McCauley I A Biochemical Profile for Predicting the Chronic Exposure of Sheep to Microscystis Aeruginosa, an Hepatotoxic Species of Blue-Green Alga. Research in Veterinary Science 1994, 57 (3), 310–316. 10.1016/0034-5288(94)90123-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Stewart I; Seawright AA; Shaw GR Cyanobacterial Poisoning in Livestock, Wild Mammals and Birds--an Overview. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 2008, 619, 613–637. 10.1007/978-0-387-75865-7_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Steffen MM; Davis TW; McKay RML; Bullerjahn GS; Krausfeldt LE; Stough JMA; Neitzey ML; Gilbert NE; Boyer GL; Johengen TH; Gossiaux DC; Burtner AM; Palladino D; Rowe MD; Dick GJ; Meyer KA; Levy S; Boone BE; Stumpf RP; Wynne TT; Zimba PV; Gutierrez D; Wilhelm SW Ecophysiological Examination of the Lake Erie Microcystis Bloom in 2014: Linkages between Biology and the Water Supply Shutdown of Toledo, OH. Environmental Science & Technology 2017, 51 (12), 6745–6755. 10.1021/acs.est.7b00856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Qin B; Zhu G; Gao G; Zhang Y; Li W; Paerl HW; Carmichael WW A Drinking Water Crisis in Lake Taihu, China: Linkage to Climatic Variability and Lake Management. Environmental Management 2010, 45 (1), 105–112. 10.1007/s00267-009-9393-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Dawson RM The Toxicology of Microcystins. Toxicon 1998, 36 (7), 953–962. 10.1016/S0041-0101(97)00102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Chernoff N; Hill D; Lang J; Schmid J; Le T; Farthing A; Huang H The Comparative Toxicity of 10 Microcystin Congeners Administered Orally to Mice: Clinical Effects and Organ Toxicity. Toxins 2020, Vol. 12, Page 403 2020, 12 (6), 403. 10.3390/TOXINS12060403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Honkanen RE; Zwiller J; Moore RE; Daily SL; Khatra BS; Dukelow M; Boynton AL Characterization of Microcystin-LR, a Potent Inhibitor of Type 1 and Type 2A Protein Phosphatases. J Biol Chem 1990, 265 (32), 19401–19404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Omidi A; Esterhuizen-Londt M; Pflugmacher S Still Challenging: The Ecological Function of the Cyanobacterial Toxin Microcystin – What We Know so Far. Toxin Reviews 2018, 37 (2), 87–105. 10.1080/15569543.2017.1326059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Janssen EML Cyanobacterial Peptides beyond Microcystins – A Review on Co-Occurrence, Toxicity, and Challenges for Risk Assessment. Water Research 2019, 151, 488–499. 10.1016/j.watres.2018.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Botes DP; Tuinman AA; Wessels PL; Viljoen CC; Kruger H; Williams DH; Santikarn S; Smith RJ; Hammond SJ The Structure of Cyanoginosin-LA, a Cyclic Heptapeptide Toxin from the Cyanobacterium Microcystis Aeruginosa. Journal of the Chemical Society, Perkin Transactions 1 1984, No. 0, 2311–2318. 10.1039/P19840002311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Rinehart KL; Namikoshi M; Choi BW Structure and Biosynthesis of Toxins from Blue-Green Algae (Cyanobacteria). J Appl Phycol 1994, 6 (2), 159–176. 10.1007/BF02186070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zeck A; Weller MG; Bursill D; Niessner R Generic Microcystin Immunoassay Based on Monoclonal Antibodies against Adda. Analyst 2001, 126 (11), 2002–2007. 10.1039/B105064H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Tillett D; Dittmann E; Erhard M; Von Döhren H; Börner T; Neilan BA Structural Organization of Microcystin Biosynthesis in Microcystis Aeruginosa PCC7806: An Integrated Peptide-Polyketide Synthetase System. Chemistry and Biology 2000, 7 (10), 753–764. 10.1016/S1074-5521(00)00021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Welker M; Von Döhren H Cyanobacterial Peptides - Nature’s Own Combinatorial Biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2006, 30 (4), 530–563. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Mikalsen B; Boison G; Skulberg OM; Fastner J; Davies W; Gabrielsen TM; Rudi K; Jakobsen KS Natural Variation in the Microcystin Synthetase Operon mcyABC and Impact on Microcystin Production in Microcystis Strains. Journal of bacteriology 2003, 185 (9), 2774–2785. 10.1128/jb.185.9.2774-2785.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Dittmann E; Fewer DP; Neilan BA Cyanobacterial Toxins: Biosynthetic Routes and Evolutionary Roots. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2013, 37 (1), 23–43. 10.1111/J.1574-6976.2012.12000.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Tooming-Klunderud A; Mikalsen B; Kristensen T; Jakobsen KS The Mosaic Structure of the mcyABC Operon in Microcystis. Microbiology 2008, 154 (7), 1886–1899. 10.1099/mic.0.2007/015875-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Pearson LA; Hisbergues M; Börner T; Dittmann E; Neilan BA Inactivation of an ABC Transporter Gene, mcyH, Results in Loss of Microcystin Production in the Cyanobacterium Microcystis Aeruginosa PCC 7806. Applied and environmental microbiology 2004, 70 (11), 6370–6378. 10.1128/AEM.70.11.6370-6378.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Christiansen G; Kurmayer R; Liu Q; Börner T Transposons Inactivate Biosynthesis of the Nonribosomal Peptide Microcystin in Naturally Occurring Planktothrix Spp. Applied and environmental microbiology 2006, 72 (1), 117–123. 10.1128/AEM.72.1.117-123.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Puddick J; Prinsep M; Wood S; Kaufononga S; Cary S; Hamilton D High Levels of Structural Diversity Observed in Microcystins from Microcystis CAWBG11 and Characterization of Six New Microcystin Congeners. Marine Drugs 2014, 12 (11), 5372–5395. 10.3390/md12115372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Tonk L; Van De Waal DB; Slot P; Huisman J; Matthijs HCP; Visser PM Amino Acid Availability Determines the Ratio of Microcystin Variants in the Cyanobacterium Planktothrix Agardhii. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2008, 65 (3), 383–390. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2008.00541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Liu J; Van Oosterhout E; Faassen EJ; Lürling M; Helmsing NR; Van de Waal DB Elevated pCO2 Causes a Shift towards More Toxic Microcystin Variants in Nitrogen-Limited Microcystis Aeruginosa. FEMS Microbiology Ecology 2016, 92 (2), 1–8. 10.1093/femsec/fiv159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Yancey CE; Smith DJ; Uyl PAD; Mohamed OG; Yu F; Ruberg SA; Chaffin JD; Goodwin KD; Tripathi A; Sherman DH; Dick GJ Metagenomic and Metatranscriptomic Insights into Population Diversity of Microcystis Blooms: Spatial and Temporal Dynamics of Mcy Genotypes, Including a Partial Operon That Can Be Abundant and Expressed. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2022. 10.1128/AEM.02464-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Yancey CE; Kiledal EA; Denef VJ; Errera RM; Evans JT; Hart L; Isailovic D; James W; Kharbush JJ; Kimbrel JA; Li W; Mayali X; Nitschky H; Polik C; Powers MA; Premathilaka SH; Rappuhn N; Reitz LA; Rivera SR; Zwiers CC; Dick GJ The Western Lake Erie Culture Collection: A Promising Resource for Evaluating the Physiological and Genetic Diversity of Microcystis and Its Associated Microbiome. bioRxiv October 22, 2022, p 2022.10.21.513177. 10.1101/2022.10.21.513177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Blin K; Shaw S; Kloosterman AM; Charlop-Powers Z; Van Wezel GP; Medema MH; Weber T antiSMASH 6.0: Improving Cluster Detection and Comparison Capabilities. Nucleic Acids Research 2021, 49 (W1), W29–W35. 10.1093/NAR/GKAB335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Madden T The BLAST Sequence Analysis Tool. 2013.

- (33).Bushnell B BBTools User Guide - DOE Joint Genome Institute. https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/ (accessed 2021-04-09).

- (34).Milne I; Stephen G; Bayer M; Cock PJA; Pritchard L; Cardle L; Shawand PD; Marshall D Using Tablet for Visual Exploration of Second-Generation Sequencing Data. Briefings in Bioinformatics 2013, 14 (2), 193–202. 10.1093/BIB/BBS012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Miller BR; Gulick AM Structural Biology of Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases. Methods Mol Biol 2016, 1401, 3–29. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3375-4_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Birbeck JA; Westrick JA; O’neill GM; Spies B; Szlag DC Comparative Analysis of Microcystin Prevalence in Michigan Lakes by Online Concentration LC/MS/MS and ELISA. Toxins 2019, Vol. 11, Page 13 2019, 11 (1), 13. 10.3390/TOXINS11010013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Chaffin JD; Bratton JF; Verhamme EM; Bair HB; Beecher AA; Binding CE; Birbeck JA; Bridgeman TB; Chang X; Crossman J; Currie WJS; Davis TW; Dick GJ; Drouillard KG; Errera RM; Frenken T; MacIsaac HJ; McClure A; McKay RM; Reitz LA; Domingo JWS; Stanislawczyk K; Stumpf RP; Swan ZD; Snyder BK; Westrick JA; Xue P; Yancey CE; Zastepa A; Zhou X The Lake Erie HABs Grab: A Binational Collaboration to Characterize the Western Basin Cyanobacterial Harmful Algal Blooms at an Unprecedented High-Resolution Spatial Scale. Harmful Algae 2021, 108, 102080. 10.1016/J.HAL.2021.102080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Humbert J-F; Barbe V; Latifi A; Gugger M; Calteau A; Coursin T; Lajus A; Castelli V; Oztas S; Samson G; Longin C; Medigue C; de Marsac NT A Tribute to Disorder in the Genome of the Bloom-Forming Freshwater Cyanobacterium Microcystis Aeruginosa. PLoS ONE 2013, 8 (8), e70747. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Allen MM Simple Conditions for Growth of Unicellular Blue-Green Algae on Plates1, 2. Journal of Phycology 1968, 4 (1), 1–4. 10.1111/j.1529-8817.1968.tb04667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Edgar RC MUSCLE: Multiple Sequence Alignment with High Accuracy and High Throughput. Nucleic Acids Research 2004, 32 (5), 1792–1797. 10.1093/NAR/GKH340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Huelsenbeck JP; Ronquist F MRBAYES: Bayesian Inference of Phylogenetic Trees. Bioinformatics 2001, 17 (8), 754–755. 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Segawa T; Takeuchi N; Fujita K; Aizen VB; Willerslev E; Yonezawa T Demographic Analysis of Cyanobacteria Based on the Mutation Rates Estimated from an Ancient Ice Core. Heredity 2018 120:6 2018, 120 (6), 562–573. 10.1038/s41437-017-0040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Lad A; Su RC; Breidenbach JD; Stemmer PM; Carruthers NJ; Sanchez NK; Khalaf FK; Zhang S; Kleinhenz AL; Dube P; Mohammed CJ; Westrick JA; Crawford EL; Palagama D; Baliu-Rodriguez D; Isailovic D; Levison B; Modyanov N; Gohara AF; Malhotra D; Haller ST; Kennedy DJ Chronic Low Dose Oral Exposure to Microcystin-LR Exacerbates Hepatic Injury in a Murine Model of Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Toxins 2019, 11 (9), 486. 10.3390/toxins11090486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Lad A; Hunyadi J; Connolly J; Breidenbach JD; Khalaf FK; Dube P; Zhang S; Kleinhenz AL; Baliu-Rodriguez D; Isailovic D; Hinds TD; Gatto-Weis C; Stanoszek LM; Blomquist TM; Malhotra D; Haller ST; Kennedy DJ Antioxidant Therapy Significantly Attenuates Hepatotoxicity Following Low Dose Exposure to Microcystin-LR in a Murine Model of Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11 (8), 1625. 10.3390/antiox11081625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Pearson LA; Dittmann E; Mazmouz R; Ongley SE; D’Agostino PM; Neilan BA The Genetics, Biosynthesis and Regulation of Toxic Specialized Metabolites of Cyanobacteria. Harmful Algae 2016, 54, 98–111. 10.1016/J.HAL.2015.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Christiansen G; Molitor C; Philmus B; Kurmayer R Nontoxic Strains of Cyanobacteria Are the Result of Major Gene Deletion Events Induced by a Transposable Element. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2008, 25 (8), 1695–1704. 10.1093/molbev/msn120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Giovannoni SJ; Tripp HJ; Givan S; Podar M; Vergin KL; Baptista D; Bibbs L; Eads J; Richardson TH; Noordewier M; Rappé MS; Short JM; Carrington JC; Mathur EJ Genome Streamlining in a Cosmopolitan Oceanic Bacterium. Science 2005, 309 (5738), 1242–1245. 10.1126/science.1114057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Lynch M Streamlining and Simplification of Microbial Genome Architecture. Annual Review of Microbiology 2006, 60 (1), 327–349. 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Lee M-C; Marx CJ Repeated, Selection-Driven Genome Reduction of Accessory Genes in Experimental Populations. PLOS Genetics 2012, 8 (5), e1002651. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Puddick J; Prinsep MR; Wood SA; Cary SC; Hamilton DP Modulation of Microcystin Congener Abundance Following Nitrogen Depletion of a Microcystis Batch Culture. Aquatic Ecology 2016, 50 (2), 235–246. 10.1007/s10452-016-9571-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Palagama DSW; Baliu-Rodriguez D; Snyder BK; Thornburg JA; Bridgeman TB; Isailovic D Identification and Quantification of Microcystins in Western Lake Erie during 2016 and 2017 Harmful Algal Blooms. Journal of Great Lakes Research 2020, 46 (2), 289–301. 10.1016/j.jglr.2020.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Zastepa A; Pick FR; Blais JM Fate and Persistence of Particulate and Dissolved Microcystin-LA from Microcystis Blooms. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal 2014, 20 (6), 1670–1686. 10.1080/10807039.2013.854138. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Cao D-D; Zhang C-P; Zhou K; Jiang Y-L; Tan X-F; Xie J; Ren Y-M; Chen Y; Zhou C-Z; Hou W-T Structural Insights into the Catalysis and Substrate Specificity of Cyanobacterial Aspartate Racemase McyF. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2019, 514 (4), 1108–1114. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Sielaff H; Dittmann E; Tandeau De Marsac N; Bouchier C; Von Döhren H; Borner T; Schwecke T The mcyF Gene of the Microcystin Biosynthetic Gene Cluster from Microcystis Aeruginosa Encodes an Aspartate Racemase. Biochemical Journal 2003, 373 (3), 909–916. 10.1042/bj20030396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Baran R; Brodie EL; Mayberry-Lewis J; Hummel E; Da Rocha UN; Chakraborty R; Bowen BP; Karaoz U; Cadillo-Quiroz H; Garcia-Pichel F; Northen TR Exometabolite Niche Partitioning among Sympatric Soil Bacteria. Nature Communications 2015 6:1 2015, 6 (1), 1–9. 10.1038/ncomms9289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Phelan VV; Liu W-T; Pogliano K; Dorrestein PC Microbial Metabolic Exchange—the Chemotype-to-Phenotype Link. Nat Chem Biol 2012, 8 (1), 26–35. 10.1038/nchembio.739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Zelezniak A; Andrejev S; Ponomarova O; Mende DR; Bork P; Patil KR Metabolic Dependencies Drive Species Co-Occurrence in Diverse Microbial Communities. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112 (20), 6449–6454. 10.1073/pnas.1421834112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Moffitt MC; Neilan BA Characterization of the Nodularin Synthetase Gene Cluster and Proposed Theory of the Evolution of Cyanobacterial Hepatotoxins | Applied and Environmental Microbiology. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2014, 70 (11), 6353–6362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Fewer DP; Metsä-Ketelä M A Pharmaceutical Model for the Molecular Evolution of Microbial Natural Products. The FEBS Journal 2020, 287 (7), 1429–1449. 10.1111/febs.15129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Gu L; Wang B; Kulkarni A; Geders TW; Grindberg RV; Gerwick L; Håkansson K; Wipf P; Smith JL; Gerwick WH; Sherman DH Metamorphic Enzyme Assembly in Polyketide Diversification. Nature 2009, 459 (7247), 731–735. 10.1038/nature07870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Simonsen AK Environmental Stress Leads to Genome Streamlining in a Widely Distributed Species of Soil Bacteria. ISME J 2022, 16 (2), 423–434. 10.1038/s41396-021-01082-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Grzymski JJ; Dussaq AM The Significance of Nitrogen Cost Minimization in Proteomes of Marine Microorganisms. ISME J 2012, 6 (1), 71–80. 10.1038/ismej.2011.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Chen Y-M; Lee T-H; Lee S-J; Huang H-B; Huang R; Chou H-N Comparison of Protein Phosphatase Inhibition Activities and Mouse Toxicities of Microcystins. Toxicon 2006, 47 (7), 742–746. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2006.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Su RC; Lad A; Breidenbach JD; Kleinhenz AL; Modyanov N; Malhotra D; Haller ST; Kennedy DJ Assessment of Diagnostic Biomarkers of Liver Injury in the Setting of Microcystin-LR (MC-LR) Hepatotoxicity. Chemosphere 2020, 257, 127111. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Solter P; Liu Z; Guzman R Decreased Hepatic ALT Synthesis Is an Outcome of Subchronic Microcystin-LR Toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2000, 164 (2), 216–220. 10.1006/taap.2000.8895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.