Abstract

Objectives:

Guidelines recommend addressing health behaviors, mental health, and social needs in primary care. However, it is unclear how often patients want support to address these risks. As part of a randomized trial comparing enhanced care planning versus usual care, we evaluated what risks patients wanted to address.

Methods:

All patients with multiple chronic conditions, 1 or more of which was uncontrolled, from 81 clinicians in 30 primary care practices. Using My Own Health Report (MOHR), patients identified and prioritized their health risks to create a care plan.

Results:

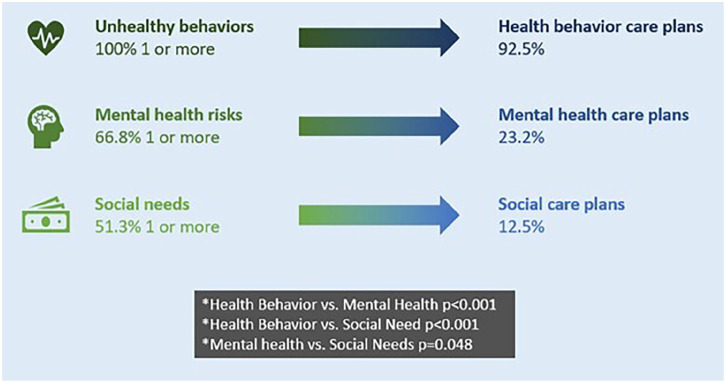

All patients had at least 1 unhealthy behavior (100%) and most had a mental health risk (66.8%) and a social need (51.3%). Participants more often chose to create care plans addressing unhealthy behaviors (92.5%) rather than mental health (23.2%), or social needs (12.5%). The most frequently created care plans were for exercise (65.1%), weight loss (37.2%), and nutrition (36.2%).

Conclusion:

All patients had 1 or more unhealthy behaviors, mental health risks, or social needs, and were more likely to address health behaviors. We need to better understand these patient choices, and change the culture to normalize the integration of mental health and social care into primary care.

Keywords: chronic disease, patient preferences, primary care, care planning, patient navigation

Introduction

Efforts focused on addressing and helping patients improve the root causes of poor health could potentially save more lives than society’s current heavy investment in conventional medical advances. 1 Calls to address health behaviors, mental health, and social needs have been issued by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM), World Health Organization (WHO), and many others.2 -7 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) has multiple recommendations to screen and counsel for unhealthy behaviors and mental health, such as screening and counseling for unhealthy alcohol use, promoting weight loss to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality, and screening for depression and anxiety. 8 Many of the USPSTF recommendations also address social needs or incorporate social risks throughout their recommendations. 9 The NASEM recommends to screen for social needs and integrate social needs care into the delivery of healthcare. 10 However, it is difficult to address these root causes of poor health in primary care and it remains unclear how to best integrate these difficult services into routine practice.

Focusing on people with uncontrolled chronic medical conditions may be one strategy to identify the people who may benefit the most from these services. Many people with poorly controlled multiple chronic conditions (MCC) also have unhealthy behaviors, mental health challenges, and unmet social needs. Conventional medical management of MCC may be less effective if individuals are struggling to meet these basic needs. The primary purpose of this paper is to examine: (a) the frequency of different health risks including unhealthy behaviors, mental health, and social needs; (b) patient preferences about improving unhealthy behaviors, mental health risks, and social needs in primary care; (c) the strategies they selected as part of their care plan; and (d) variation based on sociodemographic factors.

Methods

This analysis was conducted as part of a clinician level randomized control trial (RCT) to test whether care planning to address root causes of poor health improves control of chronic conditions more than conventional biomedical care. 11 While the study was an RCT, this paper focused only on an analysis about improvement of chronic disease control with the intervention group. We assessed the health behavior, mental health, and social risks of participants; how often they created care plans to address risks; the strategies they selected as part of their care plan; and any variation based on sociodemographic factors. Our study was approved by the Virginia Commonwealth University Institutional Review Board (HM20015553).

Study Population

We recruited 81 clinicians from 30 practices in the Virginia Ambulatory Care Outcomes Research Network (ACORN) primary care practices located in the Greater Richmond region and Northern Virginia areas. ACORN has academic affiliations with over 500 primary care practices, 53 of which are located in the Greater Richmond Region. Practices range in size from 2 to 18 providers and operate under diverse ownership and insurance models. Clinicians were matched by age and sex and randomized to usual care (control condition) or care planning with patient navigation (intervention). From the electronic health record (EHR) and patient survey screener, we identified all patients age 18 years and older with two or more chronic conditions, with at least one that was uncontrolled, including cardiovascular disease or risks, diabetes, obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or depression. We focused on these multiple chronic conditions because they had measurable outcomes that we could collect from the patient’s electronic health record to show that they were improving control in response to our enhanced care planning intervention. The percentage of patients with each MCC were as follows: depression (36.4%), hyperlipidemia (82.9%), diabetes (35.3%), hypertension (73.3%), obesity (61.0%), and heart disease (18.7%). All patients meeting inclusion criteria were emailed or mailed an invitation to participate in the study. This analysis only included intervention patients, as control patients did not complete a health risk assessment (HRA) and thus did not create care plans. Research coordinators contacted patients by phone to obtain informed consent and enroll them for this study.

Intervention

The intervention includes two components. First, patients were connected with a patient navigator to help patients throughout the process. Navigators were nurses, medical students, patient access representatives, social workers, and community program managers supported by the research team. Research team members provided patient navigation training to practices, as well as ongoing consultation to patient navigators during the care planning process. Part of the navigation training included providing navigators with a patient navigator guide, 12 a registry on all of the community resources to address the root causes of poor health, and conducting biweekly navigator meetings in which navigators discussed difficult cases and shared best practices and lessons learned.

Second, patients completed an enhanced Health Risk Assessment (HRA) and care planning tool called My Own Health Report (MOHR) either on their own or with the help of the patient navigator. MOHR screens patients for unhealthy behaviors (fruit and vegetable intake, fast food, soda consumption, weekly exercise, obesity, tobacco use, alcohol use, and illegal drug use), mental health risks (depression, anxiety, loneliness, and poor sleep), and social needs (financial needs, employment status, food security, access to transportation, housing stability, dental care, home, and neighborhood safety). Once risks were identified, patients could create a care plan for up to two risks.

Outcomes

From MOHR, we determined the frequency of risks for (1) health behavior, (2) mental health, and (3) social needs. We also assessed the frequency of care plan creation for identified risks, and the total number of unique evidence-based strategies patients selected to address risks.

Data Elements

The following patient-level variables from MOHR were used for analysis: (1) demographics, (2) health risks, (3) care plans, and (4) evidence-based strategies selected.

Statistical Analysis

All patient-level characteristics were summarized as frequencies and percentages. The number of health risks, care plans, and evidence-based strategies were summarized as means, minimums and maximums. A post hoc mixed-effect logistic regression model was used with the dependent variable of creating a care plan and independent variable of having each health risk. A patient-level random effect was included to account for dependence from repeated measurements. The model-based percentages, confidence intervals, and P-value are reported, with the latter multiplicity-adjusted using the Tukey Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) approach.

Results

The overall analytic sample included 187 patients that created 1 or more care plan. A majority of patients were female (63.6%), aged 40 to 64 years (55.1%), White (63.6%), and non-Hispanic (81.3%; Table 1). Many patients had completed some graduate work or degree (38.5%) and were employed full-time (32.6%). The patient population was 30.0% Black, 63.6% White, 1.6% Asian, and 4.8% Other or Unknown.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| Patient Characteristics | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Total, N | 187 |

| Age (years) | |

| 18-39 | 8 (4.3) |

| 40-64 | 103 (55.1) |

| >64 | 73 (39.0) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 119 (63.6) |

| Male | 66 (35.3) |

| Race | |

| Asian | 3 (1.6) |

| Black | 56 (30.0) |

| White | 119 (63.6) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 3 (1.6) |

| Non-Hispanic | 152 (81.3) |

| Unknown | 32 (17.1) |

| Education | |

| Less than high school graduate | 8 (4.3) |

| High school graduate or GED | 15 (8.0) |

| Some college | 29 (15.5) |

| Associates or technical degree | 21 (11.2) |

| 4 year college degree | 41 (21.9) |

| Graduate work or degree | 72 (38.5) |

| Employment a | |

| Disabled | 5 (2.7) |

| Full-time | 61 (32.6) |

| Homemaker | 27 (14.4) |

| Part-time | 17 (9.1) |

| Retired | 2 (1.1) |

| Student | 22 (11.8) |

| Unemployed | 9 (4.8) |

| Other | 14 (7.5) |

| Unknown | 46 (24.6) |

Percentages do not sum to 100% as individuals because unknowns were removed for age, gender, race, and education due to the small number of individuals in these categories and individuals could have multiple employment selections.

All patients included in the study had at least 1 unhealthy behavior, mental health risk, or social need. Fully, 100% of patients had 1 or more unhealthy behavior and 92.5% created a health behavior care plan; 66.8% of patients had 1 or more mental health risk and 23.2% created a mental health care plan; and 51.3% of patients had at least 1 social need and 12.5% created a social needs care plan (Figure 1). There were 17 patients (9.1%) who created care plans for mental health and unhealthy behaviors; 2 patients (1.1%) created a care plan for mental health, health behavior, and social needs, and 6 patients (3.2%) created care plans for unhealthy behaviors and social needs. The difference in the likelihood of creating a health behavior versus mental health care plan if a risk was present was statistically significant (P < .001); similarly for creating a health behavior versus social need care plan (P < .001), and a mental health versus social needs care plans (P = .048).

Figure 1.

Percent of patients with a health behavior, mental health, and social risk and percent who create care plans for these risks.

Overall, the n = 187 patients had 580 unhealthy behavior risks, 240 mental health risks, and 205 social needs, and they created 236 care plans for health behavior, 29 care plans for mental health, and 12 care plans for social needs. On average, patients had 5.9 unhealthy behaviors, mental health risks, or social needs. Of patients with unhealthy behaviors, 3.2% had 1 risk, 18.2% had 2 risks, 49.7% had 3 risks, 24.1% had 4 risks, 3.7% had 5 risks, and 1.1% had 6 risks. Among patients with mental health risks, 33.6% had 1 risk, 40.8% had 2 risks, and 25.6% had 3 risks. For patients with social needs, 43.8% had 1 risk, 19.8% had 2 risks, 19.8% had 3 risks, 12.5% had 4 risks, and 4.2% had 5 risks.

As shown in Table 2, the most common unhealthy behaviors were poor nutrition (98.9%), insufficient exercise (81.7%), obesity (64.7%), smoking (14.4%), unhealthy alcohol use (44.4%), and drug use (6.4%). Patients most commonly selected exercise for creating care plans and at least 1 patient picked a care plan for every health behavior risk except drug use. The most common mental health risks were depression and anxiety (44.9%), loneliness (43.9%), and poor sleep (39.6%). All patients created a care plan. At least 1 patient picked a care plan for every mental health topic and sleep was the most selected. The most common social needs were financial risk (33.7%), limited transportation (23.0%), food insecurity (18.2%), no dental care (18.2%), safety risk (11.8%), and housing insecurity (4.9%). No patient created a care plan for food insecurity, but all other social needs were selected. The most selected social need for care plans was housing insecurity. Patients picked a range of evidence-based strategies as part of their care plan (Appendix 1).

Table 2.

Specific Patient Health Risks and Care Plan Selection.

| Need/risk | # at risk/# intervention Pts (%) | #Care plans/# at risk (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral needs/risks | ||

| Any behavioral need/risk (at least 1) | 187/187 (100) | 173/187 (92.5) |

| Nutrition | 185/187 (98.9) | 67/185 (36.2) |

| Exercise a | 152/186 (81.7) | 99/152 (65.1) |

| Weight loss a | 121/186 (64.7) | 45/121 (37.2) |

| Smoking | 27/187 (14.4) | 4/27 (14.8) |

| Alcohol | 83/187 (44.4) | 7/83 (8.4) |

| Drug use | 12/187 (6.4) | 1/12 (8.3) |

| Social needs/risks | ||

| Any social need/risk (at least 1) | 96/187 (51.3) | 12/96 (12.5) |

| Financial | 63/187 (33.7) | 5/63 (7.9) |

| Food security | 34/187 (18.2) | 0/34 (0.0) |

| Transportation | 43/187 (23.0) | 1/43 (2.3) |

| Housing security | 9/185 (4.9) | 1/9 (11.1) |

| Dental | 34/187 (18.2) | 3/34 (8.8) |

| Safety | 22/187 (11.8) | 2/22 (9.1) |

| Mental health needs/risks | ||

| Any mental health need/risk (at least 1) | 125/187 (66.8) | 29/125 (23.2) |

| Anxiety or depression | 84/187 (44.9) | 10/84 (11.9) |

| Loneliness | 82/187 (43.9) | 8/82 (9.8) |

| Sleep | 74/187 (39.6) | 11/74 (14.9) |

“Exercise” has 1 CP and “Weight Loss” has 12 CPs without a respective HR that are not included in the #Care Plans numerator.

While there were differences in the frequency of risks or likelihood of creating care plans by age, gender, race, ethnicity, and education, no differences were statistically significant by these demographic categories; however, the sample size lacked power to detect differences (Figure B1).

Discussion

All patients with at least 1 uncontrolled MCC had at least 1 unhealthy behavior, mental health risk, or social need, and on average, patients had a total of 5.9 needs across the 3 domains. This suggests that addressing these root causes of poor health may be essential to improving control of or even preventing MCC. While we had a relatively higher number of patients with graduate level education or work experience compared to the overall sample, there were no statistically significant differences in the frequency of risks or likelihood of creating care plans by education.

Our findings of greater hesitancy to create care plans for mental health and especially social needs are consistent with the published literature. While there is growing recognition among clinicians and patients on the need and value of screening and addressing mental health and social needs,13,14 there are multiple reasons why patients may be hesitant to seek assistance addressing these topics in primary care. Mental health and social needs are more sensitive topics, and patients have more concerns about the privacy and confidentiality of their mental health and social information. 13 Additionally, mental health and social needs are associated with stigma and negative stereotypes, both externally- and self-imposed, which reinforces avoidance. 15 Patients commonly describe negative experiences and discrimination when trying to access resources and help for mental health and social needs. 16 Conversely, having received help in the past for mental health and social needs increases patients comfort with asking for help as does seeking help in the context of a trusted relationship. 17

We have published previously on semi-structured interviews conducted to inform the design of our study, patients who expressed hesitancy to discuss needs outside of “traditional primary care” (eg, mental health and social needs). 18 In our prior work, factors that patients said would make them more comfortable discussing these needs included having a strong patient-clinician relationship to create a trusted and safe space for discussion, adequate time for discussion during visits, knowing their clinician’s practice could provide resources to help them, and ensuring appropriate high quality referrals. 18 To address these concerns, we prospectively designed our intervention to facilitate such discussions, provide information in an integrated way on these factors to both patients and clinicians, connect patients with a patient navigator, a community health worker, and many dozens of potential community support programs.11,19 Early in the study, navigators recognized that patients gravitated towards creating health behavior care plans and began to encourage patients to address mental health and social needs when they had risks, explaining how these are critical issues to their health and their clinician could help them address these needs. Even with these suggestions, patients more often focused on health behavior over mental health and social needs care plans.

The lower patient interest in creating mental health and social needs care plans is not totally unexpected. While patients knew they were enrolling in a study to address health behavior, mental health, and social needs (see Figure C1, Patient Recruitment Flyer), they were not proactively seeking care to address these needs. However, screening for mental health and social needs, as currently recommended, would similarly identify people with needs, but not necessarily seeking care. There is a need to develop and test innovations to change the culture to normalize the integration of mental health and social care into primary care. Past successful paradigm shifts such as integrating behavioral health professionals in primary care have been a positive step in this direction, but additional multi-level efforts to address the stigma of mental health and social needs are needed.

Conclusions

Patients prioritize addressing health behaviors than mental health and social needs. We need to better understand the impact of these patient choices and develop and test innovations to change the primary care culture to normalize the integration of mental health and social care into primary care.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to the participating clinicians, practices, and patients who made this study and analysis possible.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

The Evidence-Based Strategies Patients Selected to Improve the Top 3 Unhealthy Behavior, Mental Health, and Social Needs Risks.

| Care plan topic | Number of patients who created a care plan | Number of evidence-based strategies selected | Number of evidence-based strategies | Frequency of top strategies (%) | Top strategies selected |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Min, max | ||||

| Unhealthy behaviors | |||||

| Nutrition | 67 | 7.2 (4.7) | (0, 21) | 49/67 (73.1) 36/67 (53.7) 35/67 (52.2) 35/67 (52.2) |

Eat more vegetables Find healthy recipes online Research more about nutrition on your own Stop or eat fewer unhealthy snacks |

| Physical activity | 100 | 5.8 (3.2) | (0, 16) | 61/100 (61) 55/100 (55) 52/100 (52) |

Develop an exercise routine Walk more every day Make exercise part of every day |

| Weight loss | 57 | 9.5 (5.1) | (1, 25) | 37/57 (64.9) 33/57 (57.9) 32/57 (56.1) |

Eat more vegetables Walk more every day Stop or eat fewer unhealthy snacks |

| Smoking | 4 | 5 (2.9) | (2, 9) | 2/4 (50) 2/4 (50) 2/4 (50) 2/4 (50) 2/4 (50) 2/4 (50) |

Figure out your pitfalls (what makes you smoke) and come up with a plan to not smoke when you encounter a pitfall Get help from a telephone counselor by calling 1-800-quit-now Make a quit plan at https://smokefree.gov/build-your-quit-plan Set a quit date Talk with your doctor about nicotine replacement Talk with your doctor about options |

| Alcohol use | 7 | 2.3 (2.0) | (0, 5) | 4/7 (57.1) 2/7 (28.6) 2/7 (28.6) |

Plan for more days when you have no drinks *Connect with a case manager for increased support Set a goal and keep track of how much you drink |

| Drug use | 1 | 0 | (0, 0) | n/a | n/a |

| Any unhealthy behavior | 173 | 9.4 (7.3) | (0, 46) | ||

| Social needs | |||||

| Financial | 5 | 4.4 (7.1) | (0, 17) | 3/5 (60) 3/5 (60) 2/5 (40) |

*Learn from a financial counselor Build a financial plan *Get free legal information about money and debt |

| Food security | 0 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Transportation | 1 | 0 | (0, 0) | n/a | n/a |

| Housing | 1 | 8 | (8, 8) | 1/1 (100) 1/1 (100) 1/1 (100) |

*Apply for assistance with your bills - gas, electric, phone, internet *Apply for public housing voucher to help with rent *Connect with a case manager or housing counselor for help |

| 1/1 (100) 1/1 (100) 1/1 (100) 1/1 (100) 1/1 (100) |

*Enroll in a program to find permanent housing *Find transitional housing *Get guidance on reducing housing costs and maintenance *Get help with a loan, mortgage, or subsidy to buy a home *Learn how to better manage your finances |

||||

| Dental | 3 | 6.7 (2.5) | (4, 9) | 3/3 (100) 3/3 (100) 2/3 (66.7) 2/3 (66.7) 2/3 (66.7) 2/3 (66.7) |

*Find a dentist *Find free or reduced fee dental care near you *Get help paying a dental bill Stop or drink less soda Talk to your doctor or dentist about options to help you Visit the dentist at least twice a year |

| Safety | 2 | 3 (4.2) | (0, 6) | 1/2 (50) 1/2 (50) 1/2 (50) 1/2 (50) 1/2 (50) 1/2 (50) |

*Call a hotline *Create a safety plan *Find a shelter near you *Get a referral for counseling to cope with what happened to you *Learn about ways to improve financial security Change where or who you live with |

| Any social | 12 | 4.7 (5.1) | (0, 17) | ||

| Mental health | |||||

| Anxiety or depression | 10 | 7.1 (3.5) | (3, 13) | 7/10 (70) 7/10 (70) 6/10 (60) |

Practice putting things in perspective and recognize what you can and cannot control Talk to your doctor about whether you might benefit from a medication *Try meditation or mindfulness |

| Loneliness | 8 | 4.4 (2.7) | (2, 9) | 5/8 (62.5) 4/8 (50.0) 3/8 (37.5) 3/8 (37.5) 3/8 (37.5) 3/8 (37.5) 3/8 (37.5) 3/8 (37.5) |

Call, text, or email people in your life Make time every day to get together with friends and family *Get a referral for counseling *Join a social or service club *Try meditation or mindfulness Adopt a pet Find an organization you want to help and volunteer Talk to your doctor about ways to reduce loneliness |

| Sleep | 11 | 7.1 (4.7) | (2, 16) | 7/11 (63.6) 6/11 (54.5) 6/11 (54.5) |

*Get more exercise Do a calming routine every night before you go to bed Use a Fitbit or wearable to track your sleep |

| Any mental | 29 | 6.3 (3.9) | (2, 16) | ||

Figure B1.

Health risks and care plans by patient demographics.

Figure C1.

Patient recruitment flyer.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this study is provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1RO1HS026223-01) and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (ULTR002649). The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the funders.

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent Statement: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Virginia Commonwealth University and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

ORCID iDs: Jennifer L. Gilbert  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4369-026X

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4369-026X

Alex H. Krist  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4060-9155

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4060-9155

Data Availability Statement: Data is provided in the manuscript.

References

- 1. Woolf SH, Johnson RE, Phillips RL, Philipsen M. Giving everyone the health of the educated: an examination of whether social change would save more lives than medical advances. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(4):679-683. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.084848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. US Preventive Services Task Force, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;328(15):1534-1542. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. US Preventive Services Task Force, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2023;329(23):2057-2067. doi: 10.1001/jama.2023.9297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Preventive Services Task Force, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, et al. Screening for anxiety in children and adolescents: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2022;328(14):1438-1444. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.16936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. US Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, et al. Behavioral counseling interventions to promote a healthy diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults with cardiovascular risk factors: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2020;324(20):2069-2075. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Siu AL, US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380-387. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Behavioral weight loss interventions to prevent obesity-related morbidity and mortality in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1163-1171. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.13022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krist AH, Davidson KW, Ngo-Metzger Q. What evidence do we need before recommending routine screening for social determinants of health? Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(10):602-605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Davidson KW, Kemper AR, Doubeni CA, et al. Developing primary care-based recommendations for social determinants of health: methods of the U.S. preventive services task force. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(6):461-467. doi: 10.7326/M20-0730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Care Services; Committee on Integrating Social Needs Care into the Delivery of Health Care to Improve the Nation’s Health. Integrating Social Care into the Delivery of Health Care: Moving Upstream to Improve the Nation’s Health. National Academies Press; 2019. Accessed July 4, 2024. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK552597/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Krist AH, O’Loughlin K, Woolf SH, et al. Enhanced care planning and clinical-community linkages versus usual care to address basic needs of patients with multiple chronic conditions: a clinician-level randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):517. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04463-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Study-resources. Accessed October 17, 2024. https://ecpvirginia.squarespace.com/study-resources

- 13. Gruß I, Varga A, Brooks N, Gold R, Banegas MP. Patient interest in receiving assistance with self-reported social risks. J Am Board Fam Med JABFM. 2021;34(5):914-924. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2021.05.210069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anastasia EA, Guzman LE, Bridges AJ. Barriers to integrated primary care and specialty mental health services: perspectives from Latinx and non-Latinx White primary care patients. Psychol Serv. 2022;20:48-63. doi: 10.1037/ser0000639 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51 Suppl:S28-S40. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. De Marchis EH, Hessler D, Fichtenberg C, et al. Part I: a quantitative study of social risk screening acceptability in patients and caregivers. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6 Suppl 1):S25-S37. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Swavely D, Whyte V, Steiner JF, Freeman SL. Complexities of addressing food insecurity in an urban population. Popul Health Manag. 2019;22(4):300-307. doi: 10.1089/pop.2018.0126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. O’Loughlin K, Shadowen HM, Haley AD, et al. Patient preferences for discussing and acting on health-related needs in primary care. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13:21501319221115946. doi: 10.1177/21501319221115946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shadowen H, O’Loughlin K, Cheung K, et al. Exploring the relationship between community program location and community needs. J Am Board Fam Med JABFM. 2022;35(1):55-72. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2022.01.210310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]