Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the frequency and duration of technology use by autistic children, their primary activities when engaging with technology, and the association between technology use and quality of life. We assumed that technology serves as a means of communication with peers, and it is associated with an improved quality of life.

Methods

The study sample consisted of 61 parents of autistic children aged 5–10 years old. The Quality of Life for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Scale was used to measure children's quality of life based on parent report, and the Technology Use Scale was used to measure the amount of time spent using technology and its purpose. Data collected were analyzed to identify correlations between technology use and quality of life.

Results

Findings indicate that autistic children primarily use technology for relaxation purposes and a smaller proportion of children in the sample used technology for socialization. A positive correlation was found between technology use for social interactions and higher parental perceptions of quality of life. These findings suggest that while social use of technology is less frequent, it is associated with improved well-being.

Conclusions

We concluded that technology use among autistic children is predominantly for leisure activities; however, when used for socialization, it is linked to a better perceived quality of life. Future research should further explore the specific benefits and potential risks of technology use for communication and socialization in autistic children. Additionally, the efficacy of technology-based interventions in improving social skills and overall well-being should be evaluated.

Keywords: Screen time, quality of life, autistic children, technology use, interpersonal relationships

Introduction

Quality of life for autistic children

Quality of life refers to one's well-being or satisfaction across life domains, such as emotional and physical well-being, social inclusion, interpersonal relationships, and self-determination.1,2 Over the last several decades, quality of life has received increased attention in the field of autism research. Specifically, researchers have demonstrated that autistic individuals, including children, have a lower quality of life than neurotypical individuals across life domains (e.g. Ayres et al.; 3 Van Heijst and Geurts 4 ). For example, Kuhlthau et al. 5 reported an average overall health-related quality of life score significantly lower for autistic children compared to the quality-of-life score in a normative sample of typical children. Furthermore, Limbers, Heffer, and Varni 6 found that children with Asperger syndrome had a significantly lower quality of life than their healthy peers.

To better understand the lower quality of life of autistic children, researchers have examined the influence of various personal and environmental factors, such as age, gender, autism severity, race/ethnicity, intelligence quotient (IQ), and executive functioning on the quality of life in autistic children, adolescents, and adults with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) (e.g. De Vries and Geurts; 7 Kim and Bottema-Beutel; 8 Oakley et al. 9 ). For example, De Vries and Geurts 7 investigated the overall quality of life of autistic children and the impact of the IQ language abilities, autistic characteristics, and executive functioning on their perceived quality of life. Despite adjusting for variances in IQ, the authors concluded that delayed language acquisition, heightened language impediments by the age of 5 years old, more conspicuous autistic traits, and deficits in executive functioning result in (a) a poorer well-being in various domains of quality of life, including physical and emotional well-being, social inclusion, and (b) lower academic performance compared to their neurotypical peers.

Furthermore, factors such as the severity of ASD, psychiatric comorbidities, and adaptive behavior impairments have been associated with lower levels of quality of life in autistic children. 10 For example, Schneider et al. examined the effect of adaptive behavior, psychiatric comorbidities, and autism severity on the quality of life of 32 autistic children using standardized measures. Their results showed no association between the level of autism severity in autistic children and their quality of life. In contrast, psychiatric comorbidities were associated with poor school adjustment. Researchers have also demonstrated an association between age, gender, race/ethnicity, and quality of life. Specifically, Chezan et al. 11 evaluated the quality of life in 1317 autistic children ages 5–10 years old using the Quality of Life for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Scale (QOLASD-C 12 ). Their results indicated that younger autistic children, children with less severe levels of autism, and minority children had a higher quality of life than older children, children with higher levels of autism severity, and majority autistic children. In addition, no association was found between quality of life and gender.

A large body of literature has examined the quality of life across the lifespan for autistic individuals. For example, Van Heijst and Geurts conducted a meta-analysis on quality of life of 486 autistic people and 17,776 controls included in 10 studies published between 2004 and 2012. Their findings revealed that autistic individuals had a lower quality of life than neurotypical individuals, and the most affected quality-of-life domain for autistic individuals was social functioning. 4 Van Heijst and Geurts also highlighted the limited research on quality of life for older autistic individuals and the need for additional studies on this topic.

The studies mentioned previously have advanced our understanding of the level of quality of life experienced by autistic children and the personal and environmental factors that may contribute to a lower level of quality of life in this population. Therefore, researchers have emphasized the importance of providing comprehensive and appropriate supports and services to enhance and evaluate the quality of life of individuals with disabilities, including autistic children, in the fields of education, health care, and social services.13,14 For example, Alasiri et al. 15 examined the effect of various support programs on the quality of life in autistic children. Their findings indicated that comprehensive support systems significantly enhance (a) multiple domains of quality of life, including physical well-being, emotional well-being, social inclusion, and (b) academic performance and, thus, underscored the importance of tailored interventions and supportive environments in improving the overall quality of life in autistic children. However, to our knowledge, there are no published studies that investigated the effect of technology use on the quality of life of autistic children as perceived by their parents.

The impact of technology

Valencia et al. 16 conducted a systematic literature review of 94 studies published between 2009 and 2019 that examined how technological approaches used in education address user experience, usability, accessibility, and the integration of game elements to enhance learning environments and skill development in autistic individuals. Their findings revealed that the development of applications for autistic individuals has shown considerable promise and the use of technological advancements, such as virtual agents, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and augmented reality, has created an enriched learning environment for this population of individuals. 16 In addition, Valencia et al. categorized the reviewed studies according to specific learning topics to better understand the contribution of technology to the education of autistic individuals based on specific target skills. The topics analyzed in their review included (a) conceptual skills such as language, money, colors, mathematics, programming, and science; (b) practical skills such as health, daily life, and transportation; (c) social skills such as communication, emotions, and interpersonal relationships; and (d) general skills. Their results showed that language, interpersonal skills, and emotions were the skills most often taught using technology. 16

However, a very limited body of literature exists on the technology habits of autistic children and adolescents. Moreover, the authors of published studies on this topic reported mixed results. Specifically, several studies have suggested that autistic youth often engage in extensive screen use by dedicating numerous hours to activities that are not inherently social, such as playing video games and watching television.17,18 Furthermore, autistic children tend to spend more time on screen-related activities than their non-autistic siblings, neurotypical peers, and youth with other disabilities.17,19–21 Other studies have revealed no discernible differences in daily screen time between autistic and non-autistic children, although both groups surpassed recommended screen time limits. 22 The mixed results reported in the published literature on the use of technology by autistic individuals reveal the complex nature of the patterns of technology use in this population of individuals and, thus, highlight the need for further investigation and updated empirical insights. For example, educational apps designed for autistic individuals are found to be beneficial for developing social skills or academic performance in some studies, especially when tailored to individual needs. 23 Yet, other studies suggested that technologies may need to reach a high standard of design quality to effectively engage people. 24

Several researchers have indicated that autistic children and youth spend a substantial time engaged with screen-based electronic media, including televisions, computers, and video games.16,18,25–27 In addition, preliminary empirical evidence has suggested several potential benefits of technology use for autistic children across social and cognitive domains, including children's engagement when electronic media was used to deliver intervention.16,18,26,28 Nonetheless, researchers have expressed concerns regarding the potential for problematic technology use among autistic individuals in contrast to their neurotypical peers, particularly related to their engagement in screen-based activities.20,27,29 Although guidelines regarding technology use have been published, 30 these guidelines have predominantly focused on neurotypical children without considering the unique needs of autistic children. Considering the limited empirical evidence on the risks and benefits of technology use in autistic individuals and the lack of specific technology guidelines for this population, additional research is needed to further investigate this topic.

To better understand the risks and benefits of technology use in autistic children, Cardy et al. 25 conducted a study to examine parental attitudes towards children's technology use. Their findings revealed a multifaceted spectrum of emotions encompassing enjoyment, guilt, and frustration. Specifically, parents of autistic children exhibited a broader range of sentiments, including excitement, hope, and relief, which may have been influenced by the evolving technologies and their preference for technology. However, despite these positive views, many parents reported feelings of guilt and frustration, particularly when screen time exceeded recommended existing guidelines. The findings also revealed that technology use among younger children often evoked positive emotions from parents, whereas use among older children was associated with negative feelings such as anger and worry. 25 These negative sentiments were possibly the result of negative consequences associated with technology use, including disruptions in sleep, academic work, and social activities. Additionally, although the use of technology by boys during weekends was not significantly different from the use of technology by girls, parents perceived it as more bothersome potentially due to differences in content types or platforms. Furthermore, the authors of this study underscored the impact of sociodemographic factors such as ethnicity, household income, and parental education on parental attitudes towards technology use. 25

As mentioned previously, one of the most important benefits of technology use in autistic children is engagement during activities involving technology. For example, Laurie et al. 31 conducted a survey to identify activities in which autistic children reported the highest engagement. Their findings indicated that autistic children reported high engagement levels during various activities, including watching videos, taking photos and videos, listening to music, and playing video games. Furthermore, the findings of the study showed that autistic children spend more time in front of screens and used technology for therapeutic and educational purposes than neurotypical children. Based on the findings of their study, Laurie et al. 31 have suggested that entertainment activities, such as watching videos and playing video games, could contribute to the development of social skills and socio-cultural knowledge in autistic children and, thus, promote the acquisition of skills needed for social interactions with peers. Another important benefit of technology use in autistic children relates to vocal and motor imitation. For example, Shane and Albert 32 found that over half of autistic children engage in some form of vocal or motor imitation while watching TV programs or movies. The authors suggested that children may benefit from observational learning through screen-based media.

The benefits of technology use highlighted in the studies mentioned previously are significant considering their potential to enhance the effective functioning of autistic children in the natural environment and their quality of life. For example, the opportunity to engage in behaviors such as vocal and motor imitation or observational learning during technology use could promote language and social skills acquisition. Although technology-mediated social interactions are not traditionally favored over face-to-face social interactions, they provide an alternative means of connecting with others that may be more accessible and supportive for a broader range of individuals. 32 However, it is important to note that these observations are based on parents’ perspectives related to technology use in autistic children. 32 It is also critical to consider the negative consequences associated with excessive use of screen media in autistic children including the tendency to spend less time in activities such as outdoor play, educational games, reading and completing homework, socializing with others, or engaging in physical activity.20,32 Additionally, an aspect that needs to be examined in future studies is the perspective of neurodivergent individuals on this topic to ensure that the relevance and importance of certain activities, such as face-to-face socializing, reflect the preferences and values of this community. 32

Considering the potential benefits of digital technologies on the acquisition of social communication skills and emotion recognition, the improved academic performance,33–36 and the paucity of existing empirical evidence on this topic, 28 it is critical to conduct additional research investigating the technology use in autistic children and its effects on their quality of life. 28 Therefore, our main purpose in this study was to identify the activities in which young autistic children engage during technology use and the impact of technology use on the quality of life of autistic children as perceived by their parents. Our research questions were as follows:

How much time do autistic children spend using technology?

What are the main activities in which autistic children engage when using technology?

Do autistic children use technology for socializing or for relaxation purposes?

Is technology use associated with a higher level of quality of life in autistic children when used to communicate with a group of peers?

Method

Participants

The sample included in this study consisted of 61 parents of autistic children aged 5–10 years old (M = 7.38, SD = 3.08). In this study, we aimed to obtain a medium effect size (r = 0.30) and, therefore, a sample size of approximately 60–80 participants was adequate according to G*Power. Because we targeted a vulnerable population (i.e. autistic children) and only a small number of autistic children in the population met our inclusion criteria, it was inherently harder to recruit a larger sample size. The population may have been geographically dispersed or only available through specialized clinics or programs. We distributed an electronic questionnaire to multiple inclusive centers and to teachers and parents of autistic children in the northwestern region in Romania. Data were collected online over 3 months between March and May 2024.

To be included in this study, parents had to (a) have a child with autism between the ages of 5 and 10 years old and (b) have lived with their child for at least one year. We used the following exclusion criteria to ensure the integrity of the sample and the validity of the findings concerning parents of autistic children: presence of sensorial comorbidities, non-autistic diagnosis, and age outside the specified range. Of the 61 children whose descriptive data were reported by parents, nine children were 5 years old, two children were 6 years old, nine children were 7 years old, 10 children were 8 years old, eight children were 9 years old, and 23 children were 10 years old. The average age of the children included in this study was 7.5 years old. Of the participating children, 18 were females and 43 were males. Out of the 61 children, 28 children were educated in mainstream schools, 30 children attended special schools, and three children were homeschooled. Regarding the level of support required by children, 11 children required limited support, 25 children required substantial support, and 21 children required very substantial support. Parents who agreed to participate in the study signed an electronic informed consent and were directed to the first section of the questionnaire. Parents who did not provide the consent were thanked for their interest in the study. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Babes-Bolyai University (code 39574, date 6 February 2024).

Instruments

In this study, we used one electronic questionnaire that consisted of two scales. The first scale (i.e. QOLASD-C) evaluated children's quality of life. The second scale measured children's technology use and hardware preferences. In addition, parents were asked to report demographic information related to their children's age, gender, education, diagnosis, and severity of autism symptoms. We used Qualtrics to create and administer the survey electronically. A link and a QR code were provided to parents.

QOLASD-C Scale. We used the QOLASD-C developed by Cholewicki et al. 12 and further revised by Chezan et al. 37 The scale consists of 16 items through which parents rate the quality of life using Likert-type responses (i.e. 1 = Strongly disagree, 2 = Moderately disagree, 3 = Moderately agree, and 4 = Strongly agree). Parents evaluate the quality of life of autistic children aged between 5 and 10 years old across three subscales: Interpersonal Relationships (measures different levels of interactions, affection, family life, social support, and maintaining friendships); Self-Determination (measures choice-making opportunities, decision-making, abilities, and personal control); and Emotional Well-Being (measures self-concept, spirituality, wellbeing, satisfaction, and level of contentment). Psychometric data indicate high internal consistency for the overall scale (ϖ = 0.957; α = 0.90) and for the three subscales (ϖ = 0.944 and α = 0.87 for Interpersonal Relationships; ϖ = 0.932 and α = 0.81 for Self-Determination; ϖ = 0.871 and α = 0.67 for Emotional Well-Being).11,37 For our sample, the instrument demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = .907), indicating a strong correlation among the items measured.

Technology Use Scale. The Technology Use Scale was specifically developed for this study and consisted of 52 questions on a 4- or 5-point Likert scale (see Supplementary File). The purpose of the scale was to measure the media use on electronic screens (hereinafter referred to as technology use) in autistic children. We created the scale based on a model proposed by Cardy et al. 25 Using the models from the aforementioned study, we developed each of the 52 questions, categorized the questions into different sections of the scale, and adapted the questions for children aged between 5 and 10 years old. The questions were classified in eight sections: time spent using technology, use by type of device, purpose of use, the frequency of technology use in different activities, time not allocated to other activities due to technology use, impact of technology use on quality of life, areas in which the child benefits from technology use, and feelings/emotions experienced by parents when their child uses technology. The instrument demonstrated excellent internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = .912) indicating a strong correlation among the items measured.

Research design

Data were collected using Qualtrics, an encrypted platform for creating and administering electronic surveys. The survey was anonymous and was deployed to parents through social media channels, e-mail distribution, and word of mouth. In the recruitment announcement, we provided potential participants brief information about inclusion criteria, the voluntary participation, their rights to withdraw from the study without penalty, and a link to access the questionnaire. Data collection lasted from March to May 2024. Once data were collected, access to the link posted on social media was closed, and the recorded data were used for testing hypotheses and conducting data analysis. The informed consent was provided by parents in an electronic format, and the study was approved by The Research Ethics Board of University.

A correlational research design was used to examine the relation between two or more variables without establishing a causal relation between them. We analyzed variables related to the purpose of technology use and their effect on the three domains of quality of life (i.e. Emotional Well-Being, Interpersonal Relationships, and Self-Determination). This type of design focuses on measuring the degree and direction of the relation between variables and providing information on how they change together. The choice of this research design has several advantages, including the ability to determine the strength and direction of the relations between variables and the ability to predict scores based on previous knowledge. In addition, a correlational research design does not require complex procedures, the time for conducting the study is reduced, and the ecological validity is high, and it allows for the evaluation of multiple outcomes and risk factors.

Results

We used descriptive statistics, including mean frequency and standard deviations, to report our results. Although the quality-of-life scores decrease with increased levels of support, the participants in our sample reported a good quality of life of autistic children according to Chezan et al. 37 A one-way between-subject ANOVA was conducted to compare quality of life across children with different levels of support (i.e. limited support, substantial support, and very substantial support). There was a significant difference between the three groups at a P < 0.05 level for the three levels of support (F(3, 57) = 14.07, P < 0.01). Similar results were reported across the three subscales, namely interpersonal relationships (F(3, 57) = 9.95, P < 0.01); self-determination (F(3, 57) = 9.13, P < 0.01); and emotional well-being (F(3, 57) = 7.25, P < 0.01). Table 1 presents data related to the quality of life of autistic children included in this study who required different levels of support (i.e. 11 children required limited support, 25 children required substantial support, and 25 children required very substantial support).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviations for the QOLASD-C scale across levels of support for autistic children.

| Level of support Mean (SD) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | Mean (SD) | Limited support | Substantial support | Very substantial support |

| Interpersonal relationships | 16.67 (4.08) |

20.18 (2.63) |

16.96 (3.31) |

14.09 (3.70) |

| Self-determination | 16.40 (3.51) |

18.63 (2.76) |

16.32 (2.41) |

14.04 (3.16) |

| Emotional well-being | 11.87 (1.99) |

13.36 (1.62) |

11.60 (1.63) |

10.85 (1.82) |

| Quality of life (total score) | 44.95 (8.15) |

52.18 (6.40) |

44.88 (5.72) |

39.00 (6.80) |

Technology usage: Time, device, and purpose

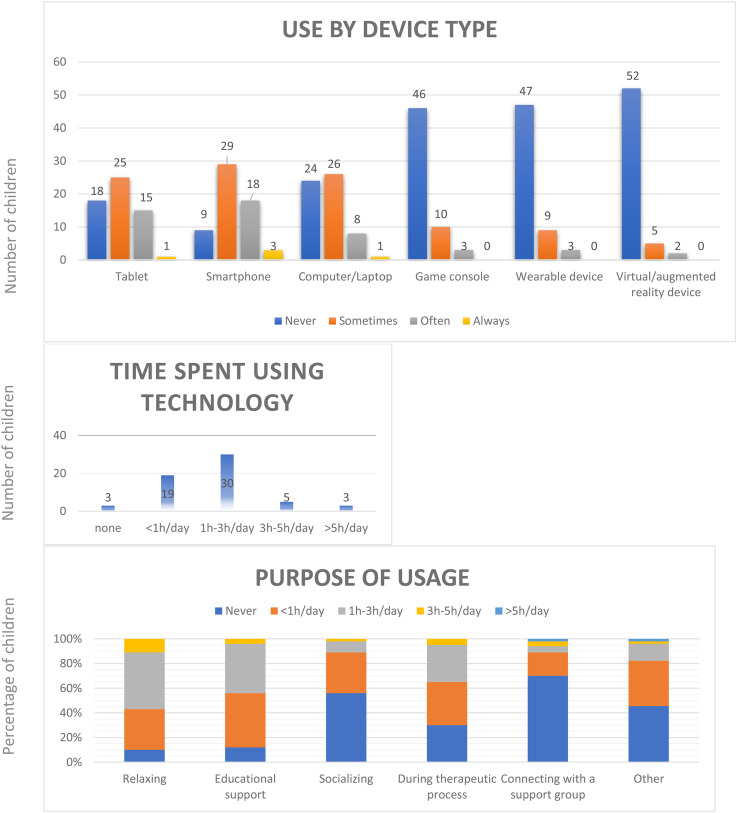

Our data revealed that 30% of the children enrolled in the study used technology less than 1 h a day and an average of 47% of the children used technology daily more than 1 h but not exceeding 3 h. Data also revealed that only 4% of children used technology more than 5 h a day. Therefore, we can conclude that most of the children included in the study sample used technology less than 1 h a day but not more than 3 h a day. Regarding the type of device used, parents reported smartphones to be the most preferred and used technology device by children. Tablets (64%) and smartphones (78%) were also used very often, whereas virtual reality systems, game consoles, and wearable devices were rarely used (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Time spent using technology, purpose of usage, and type of device used by autistic children (y axis: number of children; x axis: type of technology).

Relaxation (80%) and educational supports (78%) were the most frequently reported reasons for technology use based on parents’ report. Autistic children rarely used technology to connect with a support group or to socialize. Our results revealed that children used technology during the therapeutic process between 1 and 3 h a day but never more than 5 h a day regardless of the purpose. Data showed that although children used the technology devices more for leisure and educational support, most of them did not spend more than an average of 1–3 h per day. However, six parents reported that their children spent between 3 and 5 h per day engaged with technology for relaxation purposes (see Figure 1).

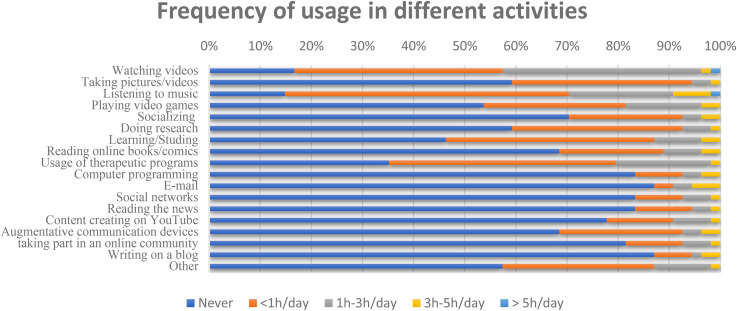

Regarding the frequency of technology use across different activities, data revealed that children spent between 1 and 3 h per day watching videos, less than 1 h daily listening to music and for therapy, playing video games, socializing trough Skype, FaceTime, and others, learning, and studying by reading books and news. Parent-reported data showed that autistic children almost never used technology devices for writing a blog or an e-mail, for computer programming, connecting to social networks, or reading the news. Considering the amount of time spent in technology-based activities, the children included in our sample reached an average of minimum 1 h to a maximum of 5 h per day (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Types of activities while using technologies and the frequency of usage (y axis: type of activity; x axis: hours of usage per day).

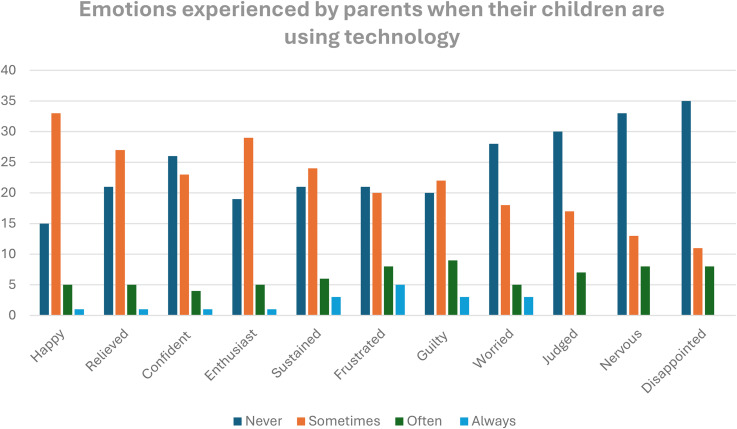

Parents’ reports revealed that they felt more often positive emotions including happiness, relief, confidence, enthusiasm, and support, and less often negative emotions such as frustration, guilty, worry, judge, nervousness, and disappointment (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Emotions experienced by parents when their children were using technology (y axis: number of children; x axis: emotions using technology).

Results indicated a significant positive correlation between interpersonal relationships and the use of technology for socialization purposes (r = 0.277, P < 0.05) suggesting that children's quality of life increased when using technology to communicate with others. Our results also showed a significant correlation between self-determination and socialization as a purpose for technology use (r = 0.348, P < 0.001). A significant correlation was identified between self-determination and emotional well-being in relation to support group (r = 0.281; r = 0.307, P < 0.05). Specifically, children who used technology for socialization purposes tended to experience a higher level of quality of life. We also found a strong correlation between interpersonal relationships and support group (r = 0.369, P < 0.001). Spearman correlations among the investigated variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Associations between quality of life and technology use (purpose of use).

| Quality of life | Technology use—purpose of use | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 1. Interpersonal relationships | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Self-determination | 0.511** | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Emotional well-being | 0.592** | 0.574** | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Relaxation | 0.131 | 0.093 | 0.087 | 1 | |||||

| 5. Educational help | 0.171 | 0.029 | 0.124 | 0.264* | 1 | ||||

| 6. Socialization | 0.277* | 0.348** | 0.207 | 0.074 | 0.288** | 1 | |||

| 7. In therapy | −0.063 | −0.105 | 0.059 | −0.162 | 0.474** | 0.273* | 1 | ||

| 8. Support group | 0.369** | 0.281* | 0.307* | −0.009 | 0.362** | 0.641** | 0.435** | 1 | |

| 9. Other activities | 0.146 | 0.126 | 0.138 | 0.061 | 0.308* | 0.438** | 0.325* | 0.537** | 1 |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Results also showed two moderate significant positive correlations between technology use for taking pictures or videos and interpersonal relationships, respectively self-determination (r = 0.364; P < 0.05; r = 0.378, P < 0.001). A significant correlation was also identified between the use of technology for taking pictures or videos and emotional well-being (r = 0.344, P < 0.05). Results did not differ significantly when investigating communications in relation to interpersonal relationships and self-determination (r = 0.493; r = 0.501, P < 0.001). We also have found a significant correlation between the technology use for creating videos and the three domains evaluated by the QOLASD-C Scale (interpersonal relationships r = 0.435, P < 0.001; self-determination r = 0.554, P < 0.001; emotional well-being r = 0.325, P < 0.05). A moderate significant correlation was identified between the technology use for studying and interpersonal relationships and self-determination (r = 0.338, P < 0.05; r = 0.333, P < 0.05). Two additional strong significant correlations were identified between augmentative and alternative communication in relation to interpersonal relationships (r = 0.425, P < 0.001) and the contribution to online communities in relation to self-determination (r = 0.457, P < 0.001). We found a strong correlation between augmentative and alternative communication and self-determination (r = 0.351, P < 0.001) and the contribution to online communities and interpersonal relationships (r = 0.367, P < 0.001). These associations show the importance of using augmentative systems to communicate in establishing social relations and improving quality of life. Spearman correlation coefficients among the investigated variables are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Associations between quality of life and technology use (frequency of use in different activities).

| Quality of life | Technology use—frequency of use in different activities | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| Interpersonal relationships | 1 | |||||||||||

| Self-determination | 0.511** | 1 | ||||||||||

| Emotional well-being | 0.592** | 0.574** | 1 | |||||||||

| Pictures or videos | 0.364* | 0.578** | 0.344* | 1 | ||||||||

| Communication | 0.493** | 0.501** | 0.329* | 0.421** | 1 | |||||||

| Information search | 0.320* | 0.477** | 0.345* | 0.413** | 0.550** | 1 | ||||||

| Studying | 0.338* | 0.333* | 0.285* | 0.411** | 0.328* | 0.641** | 1 | |||||

| Reading news | 0.387** | 0.444** | 0.314* | 0.572** | 0.649** | 0.455** | 0.368** | 1 | ||||

| Create videos | 0.435** | 0.554** | 0.325* | 0.563** | 0.586** | 0.454** | 0.413** | 0.844** | 1 | |||

| Augmentative communication | 0.425** | 0.351** | 0.324* | 0.436** | 0.518** | 0.517** | 0.474** | 0.693** | 0.540** | 1 | ||

| Contribute communities | 0.367** | 0.457** | 0.405** | 0.516** | 0.640** | 0.486** | 0.382** | 0.835** | 0.696** | 0.640** | 1 | |

| Write a blog | 0.294* | 0.361** | 0.275* | 0.512** | 0.530** | 0.387** | 0.332** | 0.879** | 0.729** | 0.623** | 0.839** | 1 |

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Our purpose in this study was to identify the most common activities regarding the use of technology in autistic children and the association between the reported activities and quality of life. The results of this study underscore the importance of various forms of engagement with technology among autistic children and their impact on the quality-of-life domains. Findings indicated that most children spent time using technology no more than 1–3 h per day. The most frequently used devices were smartphones, followed by tablets and computers. Results also revealed that virtual reality systems, game consoles, and wearable devices were rarely or never used. According to parental reports, relaxation and education were the two main reasons for children's use of technology. In addition, most autistic children used technology for therapeutic reasons. Technology use for social purposes among autistic children was minimal. Possible explanations for this finding may be related to the mean age (7.5 years old) of our sample and the difficulties experienced by autistic children when engaging in face-to-face or virtual social interactions with their peers. The use of social platforms can present difficulties for autistic children of 7 years old due to the absence of visual cues, which may hinder their ability to interpret others’ emotional states or grasp the structural components of conversations.38,39

Our results revealed that the quality of life of the children included in our sample was above the QOLASD-C Scale cutoff score suggesting that they had a good quality of life, even when children needed substantial support. This finding contradicts previous reports in the literature showing that autistic children who require substantial and very substantial levels of support experience lower quality of life.40,41 One potential explanation for this finding may be related to the values, beliefs, and cultural norms in the Romanian society. Specifically, researchers have suggested that one's perceived quality of life may be influenced by the norms and contextual factors associated with their culture. 42 For example, although researchers have consistently reported that African American and Hispanic autistic children have higher quality of life compared to White autistic children,43,44 a paucity of empirical evidence exists on the quality of life of autistic children from different ethnic groups, including Romanian children. Therefore, additional investigations are needed to advance our understanding of the contribution of race/ethnicity to the quality of life of autistic children. Furthermore, the parents in our study reported an extremely positive change in the quality of life of the children when using technology; however, a limited body of research exists on the impact of technology use on the quality of life of autistic children. Considering the technological advances in recent years and the use of technology for therapeutic, educational, and entertainment purposes, future studies should be conducted to further examine the impact of technology on the quality of life of autistic children.

Because the progress and development of novel applications for autistic individuals created numerous educational, therapeutic, and recreational possibilities for technology use, findings of published studies have shown that autistic youth are often involved in extensive screen use and dedicate significant hours to activities that are not inherently social.17,18 Our results have shown that autistic children use technology more often for relaxation and educational support rather than for reaching out to their social groups. This finding is expected considering the challenges experienced by autistic individuals in interpreting vocal and nonvocal responses and in identifying appropriate moments to initiate, maintain, or terminate conversations with social partners. 45

Previous studies have demonstrated that autistic children tend to spend more time on screen-related activities than their non-autistic siblings, neurotypical peers, and youth with other disabilities.16,17,19,26,28 Furthermore, findings of published studies have shown that autistic children spend a substantial amount of time engaged with screen-based electronic media, including televisions, computers, and video games.18,20,27,32,46 Our results indicated that autistic children spent between 1 and 3 h per day (i.e. a smaller amount of time than the one reported in previous studies) watching videos. Moreover, results revealed that autistic children spent less than 1 h per day listening to music, receiving therapy, taking pictures/videos, learning, studying, or reading books and news. However, they did not spend more than 3 h a day playing video games or socializing through Skype, FaceTime, and other social media channels.

Considering the amount of time spent by autistic children in technology-related activities, it is essential to ensure that children also engage in other nontechnology-related activities that have the potential to promote social interaction, physical activity, and cognitive development. Encouraging alternative activities such as outdoor play, sports, art, and music has the potential to promote positive health outcomes and overall well-being. 47 Therefore, supervising technology use to access age-appropriate content and promoting breaks for alternative activities involving motor movements and face-to-face interactions are vital in preventing overuse of technology in autistic children and fostering a balanced and healthy lifestyle. By advocating for a well-rounded approach to technology use and offering a variety of activities, parents and caregivers can support children's development and well-being in the digital era. Our results suggested a strong association between interpersonal relationships and the use of technology to connect with a support group. However, this result should be interpreted with caution, considering that only 30% of parents reported that their children use technology for keeping in contact with their support group.

At least two practical implications related to the association between quality of life and use of technology in autistic children warrant discussion. First, based on the association between interpersonal relationships and the use of technology for socialization purposes, it is critical to consider the role of technology in enhancing the social functioning of autistic children in the natural environment. Platforms like social media, messaging apps, and video calls could be used by practitioners and parents as educational tools for promoting social interaction and friendships between autistic children and their neurotypical peers. Moreover, the autonomy of choosing a preferred social interaction approach through technology may enhance children's motivation and engagement in conversations and interactions with social partners. Second, promoting social interactions and valued membership in their communities may lead to an improved emotional well-being in autistic children. The technology use can offer them a safe space for them to share their experiences and seek for support.

An important finding is the association between the usage of technology for taking photos or videos and increased positive interpersonal relationships. One potential explanation for this finding is that capturing and sharing unique personal moments with others can serve as a form of emotional expression and validation. Another potential explanation is that taking photos can be seen as a hobby or special interest facilitated by one's motivation to engage in preferred activities. For example, researchers have suggested that hobbies can (a) provide structure and organization to social reality, (b) foster a sense of belonging and valued membership in one's community, and (c) an avenue for engaging in social interactions. 48 Considering the potential benefits of technology use as a mechanism for facilitating engagement in hobbies or specific interests and its impact on the quality of life of by autistic children, it is critical for parents and educators to facilitate the appropriate use of digital technologies in this population of individuals.

The findings of this study provide initial empirical evidence on the potential benefits of technology use related to an enhanced functioning of autistic children in various domains. However, further research is needed to fully understand the impact of technology use on their quality of life. Recommendations for future studies on the quality of life for autistic children include conducting longitudinal studies on the effects of digital technologies on quality of life, examining its specific impacts on the language acquisition and social communication skills of autistic children, and developing interventions tailored to address the executive functioning deficits and autistic traits. In terms of technology use, future research could focus on understanding the specific benefits and risks of different types of technology, evaluating the effectiveness of technology-based interventions for promoting communication and socialization skills, and investigating how technology can contribute to the overall well-being of autistic children. It is also essential to involve autistic individuals in research on technology use to ensure that interventions align with their preferences, values, and needs. It is important to acknowledge that the conclusions drawn from this study are based on a specific sample population and may not be representative of the entire population of autistic children. Further research with larger and more diverse samples is necessary to replicate the findings of this study. While the study provides valuable insights, caution should be taken when generalizing the conclusions to broader populations.

Limitations

Although the findings of this study provide valuable insights into the relationship between technology use and the quality of life of autistic children, it is important to interpret these findings within the context of several limitations. One notable limitation is the lack of comprehensive demographic information of the parents enrolled in the study regarding their specific role (i.e. mothers versus fathers). This demographic detail could have provided a deeper understanding of parental influences on children’s technology use and quality of life. Additionally, we did not account for socioeconomic status as a variable in the analysis. Socioeconomic factors may significantly influence both the quality of life and the digital media usage patterns among families of autistic children.49,50 Future research should consider including socioeconomic status as a covariate to better understand its potential confounding effects on the outcomes measured in this study. By addressing these demographic aspects, subsequent studies can enhance the robustness and generalizability of findings related to technology use and quality of life in autistic children. Finally, we relied solely on the perspectives of parents regarding the impact of technology on their children’s quality of life. While parental insights are valuable, they may not fully capture the subjective experiences and preferences of the autistic children themselves. Therefore, the exclusion of self-reports from the children is a significant limitation because their personal experiences and viewpoints are crucial for a comprehensive understanding of how technology affects their daily lives and well-being. Future studies should include self-reports from autistic children, where possible, to provide a more comprehensive and informed perspective.

Conclusion

Autistic children spend most of their time using technology for relaxation purposes, which can provide an opportunity to escape the cognitive and social demands of their daily lives. Although a limited number of autistic children in our sample used technology for socialization purposes, we found a positive association between quality of life perceived by their parents and the children's use of technology for socialization. Based on our findings, we recommend the use of technology both for educational purposes and for leisure purposes while emphasizing the need for active parental involvement, consideration of its impact on social relationships, and ongoing monitoring of academic performance.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241304885 for Assessing technology usage in relation to the quality of life of autistic children by Cristina Costescu, Ioana Tufar, Laura Chezan, Mălina Șogor and Alexandra Confederat in DIGITAL HEALTH

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results is in the frame of the PN-IV-P8-8.1-PRE-HE-ORG-2023-0133 project, which has received funding from the UEFISCDI, Romania.

Footnotes

Contributorship: CC, LC, and IT supervised data collection, co-designed the study, performed analyses, wrote the original draft, and reviewed the manuscript. MȘ and AC collected data, performed preliminary analyses, and reviewed the manuscript. CC supervised analyses and reviewed the manuscript. LC co-designed the study, supervised analyses, and reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to sensitive information gathered from the participants (i.e. diagnosis) but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval: The study received the ethical visa from the Ethical Committee of “Babes-Bolyai” University, and all the participants signed an informed consent prior to data collection. The research was performed according to the Guidelines from Declaration of Helsinki describing human rights.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Unitatea Executiva pentru Finantarea Invatamantului Superior, a Cercetarii, Dezvoltarii si Inovarii (grant number PN-IV-P8-8.1-PRE-HE-ORG-2023-0133).

ORCID iD: Ioana Tufar https://orcid.org/0009-0008-0333-5187

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Schalock RL, Alonso MAV. Handbook on quality of life for human service practitioners. Washington, DC: American Association on Mental Retardation, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schalock RL, Keith KD, Verdugo MAet al. et al. Quality of life model development and use in the field of intellectual disability. In: Kober R. (eds) Enhancing the quality of life of people with intellectual disabilities: from theory to practice. Dordrecht: Springer, 2011, pp.17–32. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ayres M, Parr JR, Rodgers J, et al. A systematic review of quality of life of adults on the autism spectrum. Autism 2018; 22: 774–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Heijst BFC, Geurts HM. Quality of life in autism across the life span: a meta-analysis. Autism 2015; 19: 158–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kuhlthau K, Kahn R, Hill KS, et al. The well-being of parental caregivers of children with activity limitations. Matern Child Health J 2010; 14: 155–163. Erratum in: Matern Child Health J. 2011;20(9):1485–1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Limbers CA, Heffer RW, Varni JW. Health-related quality of life and cognitive functioning from the perspective of parents of school-aged children with Asperger’s syndrome utilizing the PedsQL. J Autism Dev Disord 2009; 39: 1529–1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vries M, Geurts HM. Influence of autism traits and executive functioning on quality of life in children with an autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord 2015; 45: 2734–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim SY, Bottema-Beutel K. A meta regression analysis of quality-of-life correlates in adults with ASD. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2019; 63: 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oakley BFM, Tillman J, Ahmad J, et al. How do core autism traits and associated symptoms relate to quality of life? Findings from the longitudinal European autism project. Autism 2021; 25: 389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider S, Clément C, Goltzene MA, et al. Determinants of the evolution of behaviours, school adjustment, and quality of life in autistic children in an adapted school setting: an exploratory study with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). BMC Psychiatry 2022; 22: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chezan LC, Liu J, Drasgow E, et al. The Quality of Life for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder scale: factor analysis, MIMIC modeling, and cut-off score analysis. J Autism Dev Disord 2023; 53: 3230–3245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cholewicki J, Drasgow E, Chezan LC. Parental perception of quality of life for children with autism spectrum disorder. J Dev Phys Disabil 2019; 31: 575–592. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chiang H, Wineman I. Factors associated with quality of life in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a review of literature. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2014; 8: 974–986. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schalock RL, Verdugo M. The impact of the quality-of-life concept on the field of intellectual disability. In: Wehmeyer ML. (ed) The Oxford handbook of positive psychology and disability. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2013, pp.37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alasiri RM, Albarrak DA, Alghaith DM, et al. Quality of life of autistic children and supported programs in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Cureus 2024; 16: e51645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Valencia K, Rusu C, Quiñones Det al. et al. The impact of technology on people with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic literature review. Sensors (Basel) 2019; 19: 4485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazurek MO, Shattuck PT, Wagner Met al. et al. Prevalence and correlates of screen-based media use among youths with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2012; 42: 1757–1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuo MH, Orsmond GI, Coster WJet al. et al. Media use among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2014; 18: 914–923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong HY, Wang B, Li HH, et al. Correlation between screen time and autistic symptoms as well as development quotients in children with autism spectrum disorder. Front Psychiatry 2021; 12: 619994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazurek MO, Wenstrup C. Television, video game and social media use among children with ASD and typically developing siblings. J Autism Dev Disord 2013; 43: 1258–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Must A, Phillips SM, Curtin C, et al. Comparison of sedentary behaviors between children with autism spectrum disorders and typically developing children. Autism 2014; 18: 376–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Montes G. Children with autism spectrum disorder and screen time: results from a large, nationally representative US study. Acad Pediatr 2016; 16: 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.López-Díaz JM, Camarena IG, Custodio NF. Analysis of the impact of ICT through apps on students with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Inf Educ Technol 2024; 14: 785–790. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasupuleti MB, Adusumalli HP. High technological design and application for autistic children: an analysis of digitalized therapeutic technologies. Int J Health Sci 2022; 6: 4590–4601. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardy R, Smith C, Suganthan H, et al. Patterns and impact of technology use in autistic children. Res Autism Spectr Disord 2023; 108: 102253. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Finke EH, Hickerson B, McLaughlin E. Parental intention to support video game play by children with autism spectrum disorder: an application of the theory of planned behavior. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch 2015; 46: 154–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazurek MO, Engelhardt CR. Video game use in boys with autism spectrum disorder, ADHD, or typical development. Pediatrics 2013; 132: 260–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grynszpan O, Weiss PLT, Perez-Diaz Fet al. et al. Innovative technology-based interventions for autism spectrum disorders: a meta-analysis. Autism 2014; 18: 346–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Craig F, Crippa A, Ruggiero M, et al. Characterization of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) subtypes based on the relationship between motor skills and social communication abilities. Hum Mov Sci 2021; 77: 102802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chassiakos YLR, Radesky J, Christakis D, et al. Children and adolescents and digital media. Pediatrics 2016; 138: e20162593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Laurie MH, Warreyn P, Uriarte BV, et al. An international survey of parental attitudes to technology use by their autistic children at home. J Autism Dev Disord 2019; 49: 1517–1530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shane HC, Albert PD. Electronic screen media for persons with autism spectrum disorders: results of a survey. J Autism Dev Disord 2008; 38: 1499–1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramdoss S, Lang R, Mulloy A, et al. Use of computer-based interventions to teach communication skills to children with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. J Behav Educ 2011; 20: 55–76. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramdoss S, Machalicek W, Rispoli M, et al. Computer-based interventions to improve social and emotional skills in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic review. Dev Neurorehabil 2012; 15: 119–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berggren S, Fletcher-Watson S, Milenkovic N, et al. Emotion recognition training in autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review of challenges related to generalizability. Dev Neurorehabil 2018; 21: 141–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pennington RC. Computer-assisted instruction for teaching academic skills to students with autism spectrum disorders: a review of literature. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 2010; 25: 239–248. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chezan LC, Liu J, Cholewicki JM, et al. A psychometric evaluation of the Quality of Life for Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder scale. J Autism Dev Disord 2022; 52: 1536–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benford P. The use of internet-based communication by people with autism [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Nottingham; 2008. Available from: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33564096.pdf.

- 39.Gillespie-Lynch K, Kapp SK, Shane-Simpson C, et al. Intersections between the autism spectrum and the internet: perceived benefits and preferred functions of computer-mediated communication. Intellect Dev Disabil 2014; 52: 456–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kamio Y, Inada N, Koyama T. A nationwide survey on quality of life and associated factors of adults with high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Autism 2013; 17: 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pisula E, Danielewicz D, Kawa Ret al. et al. Autism spectrum quotient, coping with stress and quality of life in a nonclinical sample—an exploratory report. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015; 13: 173–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jenaro C, Verdugo MA, Caballo C, et al. Cross-cultural study of person-centered quality of life domains and indicators: a replication. J Intellect Disabil Res 2005; 49: 734–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Moran ML, Hagiwara M, Raley SK, et al. Self-determination of students with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. J Dev Phys Disabil 2021; 33: 887–908. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shogren KA, Shaw LA, Raley SKet al. et al. Exploring the effect of disability, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic status on scores on the self-determination inventory: student report. Except Child 2018; 85: 10–27. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spence SH. Social skills training with children and young people: theory, evidence and practice. Child Adolesc Ment Health 2003; 8: 84–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Menezes M, Pappagianopoulos J, Cross Ret al. et al. Relations among screen time and commonly co-occurring conditions in autistic youth. J Dev Phys Disabil 2023; 36: 409–421. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morsonuto S, Peluso Cassese F, Tafuri Fet al. et al. Outdoor education, integrated soccer activities, and learning in children with autism spectrum disorder: a project aimed at achieving the sustainable development goals of the 2030 agenda. Sustainability 2023; 15: 13456. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lizon A, Taels L, Vanheule S. Specific interests as a social boundary and bridge: a qualitative interview study with autistic individuals. Autism 2023; 28: 1150–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsiao YJ. Autism spectrum disorders: family demographics, parental stress, and family quality of life. J Policy Pract Intellect Disabil 2018; 15: 70–79. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kumm AJ, Viljoen M, de Vries PJ. The digital divide in technologies for autism: feasibility considerations for low- and middle-income countries. J Autism Dev Disord 2022; 52: 2300–2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-dhj-10.1177_20552076241304885 for Assessing technology usage in relation to the quality of life of autistic children by Cristina Costescu, Ioana Tufar, Laura Chezan, Mălina Șogor and Alexandra Confederat in DIGITAL HEALTH