Abstract

Introduction

Understanding the lived experience of illness is important for empowering patients and informing health care practitioners. This study investigated the impact of a book-length comic memoir, My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s, by Peter Dunlap-Shohl, on patients’ mental health, knowledge, and attitudes about living with Parkinson’s disease (PD). The authors further explored which patients found the book to be beneficial and why.

Methods

In this convergent mixed methods study, patients with PD were recruited from a multidisciplinary movement disorders clinic in 2019–2020 and were eligible if cognitively intact; English-speaking; had stage I, II, or III PD; and < 12 months had elapsed since diagnosis. Participants received My Degeneration to read at home, measures were obtained pre- and postintervention, and participants were interviewed within approximately 1 month.

Results

Thirty participants completed the study (13 males and 17 female; mean age = 59 years). Four qualitative themes emerged: Reading My Degeneration 1) validated the experience of living with PD, 2) reinforced practical behaviors that support well-being, 3) provided insight about the illness experience, and 4) was emotionally and physically taxing. There were no statistically significant pre-/postintervention changes in knowledge, self-efficacy, hope, or emotional distress. Book “endorsers” appreciated Dunlap-Shohl’s dark humor and resonated with his experience; “detractors” found the book to be blunt and sometimes frightening.

Discussion/Conclusion

Participants who liked the book—the “endorsers”—revealed that it deeply resonated with them and helped them realize they were not alone with the disease. Many commented that Dunlap-Shohl’s story was in some ways their story—and that this was both practically and emotionally reassuring. My Degeneration has the potential to benefit patients who appreciate comics, enjoy dark humor, and are not overly pessimistic.

Keywords: Graphic Medicine, Comics, Parkinson’s Disease, patient experience, visual communication, quality of life

Introduction

Understanding the subjective or lived experience of illness is important for empowering patients and informing health care practitioners.1 One means of understanding what it feels like to live with illness or disease is through reading people’s stories of their experiences—that is, illness narratives or “pathographies.” These stories not only give voice to and validate people’s experiences with disease but also can offer insight into how to improve the care of patients and their quality of life (QoL).2 As such, pathographies can be valuable resources for practitioners and patients alike.

In recent years, a growing number of illness narratives have been communicated visually, using the medium of comics, giving rise to the field of “graphic medicine.”3 One story that has received acclaim for realistically portraying patients’ lived experience of Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the graphic memoir, My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s by Peter Dunlap-Shohl.4 The book portrays Dunlap-Shohl’s experience with PD from diagnosis to treatment with deep brain stimulation. A deeply personal account, it presents in words and pictures what it feels like to live with the disease and its impact on QoL. In doing so, the book also reveals universal themes related to human suffering.

Previously, the authors’ multidisciplinary team conducted a study to explore the utility of My Degeneration for clinicians who treat patients with PD. The authors reported in this journal that reading the graphic memoir helped health care practitioners better understand patients’ experience with PD.5 Moreover, clinicians maintained that this book could be a helpful resource for patients, though they felt more research was necessary to determine its value and its appropriate audience.

Accordingly, the authors conducted a study of My Degeneration with patients themselves. Using a mixed methods research design, the authors investigated PD patients’ response to reading this graphic memoir, using interviews to understand their experience with the book, as well as survey measures to learn whether reading My Degeneration would 1) increase knowledge about PD, 2) improve confidence in relaying their disease-related challenges and experiences, 3) validate their own experiences with PD, and 4) decrease emotional distress about the impact of PD. The authors report here the results of this investigation.

Methods

Overview of study design

The authors used a convergent mixed methods study design (with an explanatory sequential component) to gather qualitative and quantitative data concurrently.6 These data were analyzed separately, then merged to compare and contrast conclusions from each dataset. In addition, the authors explored qualitative themes within participant groupings based on their quantitative ratings of the book to explain differences in scores and to identify the characteristics of patients who found the book beneficial.

Description of the intervention

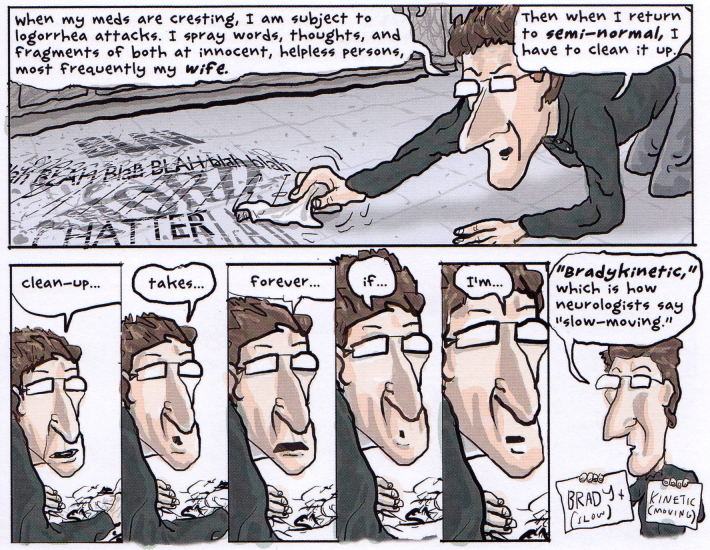

The intervention was the abovementioned graphic memoir My Degeneration. By combining words and pictures to describe the impact of Dunlap-Shohl’s PD diagnosis (Figure 1, pg 6), the effects of his illness on his personal life (Figure 2, pg 19), and the challenges of managing symptoms, Dunlap-Shohl presents a personal perspective through visual storytelling. The memoir has received positive reviews both within7 and outside8 the PD community, but it has not been previously studied as a PD intervention for patients.

Figure 1:

Reproduced with permission from Peter Dunlap-Shohl, My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s (University Park).4 p6 Copyright © 2015 The Pennsylvania State University. Reprinted courtesy of the publisher.

Figure 2:

Reproduced with permission from Peter Dunlap-Shohl, My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s (University Park).4 p19 Copyright © 2015 The Pennsylvania State University. Reprinted courtesy of the publisher.

Sample and study logistics

Participants were recruited from a movement disorders clinic in an academic health care setting from April 2019 to March 2020. Patients were eligible if they had stage I, II, or III PD and excluded if they were < 12 months from their initial PD diagnosis, were cognitively impaired, or non-English speakers.

This was a convenience sample of patients with PD, identified during clinic appointments by an attending physician who was part of the study team (SDJ). Patients who were eligible and receptive were contacted by the project’s study coordinator (MH), who explained the study, elicited informed consent, administered baseline and postintervention measures, and conducted interviews (either by phone or in-person). Participants received a $25 gift card after completing questionnaires, as well as an additional $25 after completing an interview.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

This study was submitted to the Human Subjections Protection Office at Penn State College of Medicine who determined that the research met the criteria for exempt research according to institutional policies and federal regulations. The study received grant support from the Translational Brain Research Center at Penn State College of Medicine, and none of the authors reported any conflicts of interest.

Study Design

The convergent mixed methods design involved collecting quantitative outcomes pre- and postintervention and qualitative data postintervention. Participants completed measures at baseline, reviewed the book independently, then repeated the measures 1–4 weeks later.

Quantitative measures

All quantitative measures can be found in the Supplementary Materials. To assess basic knowledge of PD, the authors modified a 13-item true/false tool that addressed common facts/myths about PD.9 Self-efficacy was assessed using a scale developed for this project that was based on Bandura’s general framework.10 The measure was designed to address participants’ confidence across 5 items, such as explaining what it is like to live with PD and communicating concerns about PD with doctors. Response options ranged from 0 to 100, where 0 = “cannot do it at all” and 100 = “highly certain I can do it.”

Mental health was evaluated using the emotion thermometer,11 where participants used a pictorial thermometer to indicate their feelings of “distress,” “anxiety,” “depression,” and “anger,” with 0 = “none” and 10 = “extreme.” A separate thermometer was used to assess QoL. Hope was measured with the validated 12-item Herth Hope Index,12,13 which has been used across diverse populations, including among individuals with life-threatening illness. The authors included an additional single item to assess current feelings of hope on a scale of 1–10, where 1 = “no hope” and 10 = “filled with hope.”

Worry and concern about the potential consequences of PD, including disability, dependency, stigmatization etc, were assessed using a 15-item instrument also modified from Moore and Knowles9 that used a 4-point scale: 1 = “not at all,” 2 = “very little,” 3 = “somewhat,” and 4 = “a great deal.” A single summative score was generated to represent overall worry and concern.

Two instruments measured attitudes toward comics: 1) a 9-point Comic Attitude Scale modified from Hosler and Boomer,14 and 2) a semantic differential scale created for this study.15 Semantic differential scales have been widely used to measure peoples’ reactions to contrasting words (eg, good vs bad) in order to derive attitudes toward a concept or subject (in this case, comics).

Overall satisfaction with the book was assessed by the single item Net Promoter Score (NPS), an instrument widely used in marketing to measure satisfaction with a brand or product.16,17 The authors asked respondents to give a rating between 0 (not at all likely) and 10 (extremely likely) to the question, “How likely is it that you would recommend My Degeneration to a family member or friend?”

Semistructured interviews

A semistructured interview guide (see the Supplementary Material) explored participants’ experiences upon reading the book, the impact of the book on participants’ knowledge and perceptions about PD, and the participants’ opinions about the comics format.

Quantitative analysis

All variables were collected pre- and postintervention except the demographic measures (collected at baseline only) and the NPS (collected at postintervention only). All variables were summarized, and the distributions of continuous variables were assessed using histograms and normal probability plots. The authors used a Wilcoxon signed rank test to make comparisons between pre- and postintervention means. The change from pre- to postintervention was calculated for each subject and compared between genders (male vs female), good health status (yes vs no), disease duration (< 10 vs ≥ 10 years), or baseline attitude score (< 20 vs ≥ 20) using a linear regression model comparing group means. The model included the preintervention response for adjustment in addition to the group variable for comparison. The authors also examined whether any of these outcomes were affected by demographic characteristics (age, gender, years since diagnosis) or attitudes toward comics. All quantitative analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Qualitative analysis

The qualitative data (n = 26 transcripts) were analyzed using inductive content analysis to identify emergent themes. Two members of the research team (BS, DRG) independently reviewed transcripts from 1/3 of the interviews to create broad concepts and codes that were later organized into a preliminary codebook with definitions and exemplar quotes (BS, DRG, KRM, LVS). The coding team (BS, DRG) then used the constant comparison method18 to apply this codebook to the data. Data saturation was achieved after the review of 18 transcripts. Reliability was assessed using Cohen’s kappa; differences in coding were iteratively discussed and resolved until kappa < 0.7 was achieved. The codebook was iteratively revised to refine reliability of coding patterns. Then, the final codebook was used to code the remainder of the dataset (2 coders per transcript). Final codes were reviewed by the entire research team and collapsed into themes. Qualitative analyses utilized NVivo 12 software.

Mixed methods analysis

To understand differences between participants who liked and did not like the book, the authors examined the qualitative data stratifying it by the NPS—that is, satisfaction. An independent analyst (LVS) reviewed coding patterns using Nvivo 12 crosstab matrix displays to examine coding patterns based on NPS scores, gender, and other demographic variables. Participants with scores of 9–10 were labeled “endorsers,” 0–6 as “detractors,” and 7–8 as “passives.” Participants were then stratified into categories of “endorsers” or “detractors” and then again by gender. Coding patterns between groups were compared. Additionally, data integration was achieved through a process called weaving,19 in which the analyst looks back-and-forth between quantitative and qualitative datasets to connect concepts and explain findings.

Results

The research team identified 68 potential participants and, of these, 44 said “yes” to participating and 24 said “no.” Reasons for declining included the following concerns: home stressor (n = 1), anxiety about reading the book (n = 1), travel distance (n = 1), interest in other studies (n = 2), concern about the small print in the book (n = 1), not being interested in reading (n = 1), and no specific details provided (n = 17). Thirty-three participants enrolled in the study at baseline, but only 30 completed follow-up measures and 26 were interviewed. The final cohort included 13 males and 17 females, and the mean age was 59.2 ± 10.9 years. One hundred percent were white and 95% had some college education. The average length of time since PD diagnosis was 10.4 years (range, 3–27 years). Participant demographics are found in Table 1.

Table 1:

Demographics

| Variable | N = 30 |

|---|---|

| Age (y), mean ± SD | 59.2 ± 10.9 |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 13 (43.3) |

| Female | 17 (56.7) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| High school or less | 2 (6.7) |

| Some college | 4 (13.3) |

| College graduate | 12 (40.0) |

| Grad school | 12 (40.0) |

| Current living arrangement, n (%) | |

| Lives alone in my home or apartment | 4 (13.3) |

| Live with someone else | 23 (76.7) |

| Live in facility | 3 (10.0) |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Retired | 20 (66.7) |

| Part-time employment | 1 (3.3) |

| Full-time employment | 2 (6.7) |

| Other | 7 (23.3) |

| PD diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Before 2010 | 14 46.7) |

| After 2010 | 15 (50.0) |

| Missing | 1 (3.3) |

| Self-rated QoL, n (%) | |

| Very good | 4 (13.3) |

| Good | 19 (63.3) |

| Neither good nor poor | 6 (20.0) |

| Poor | 1 (3.3) |

| Religion/spirituality, n (%) | |

| Extremely important | 10 (33.3) |

| Very important | 10 (33.3) |

| Moderately important | 7 (23.3) |

| Slightly important | 2 (6.7) |

| Not at all important | 1 (3.3) |

PD, Parkinson’s disease; QoL, quality of life; SD, standard deviation.

Pre-/Postintervention Changes in Quantitative Outcomes

In this highly educated sample (80% attended college or graduate school), participants’ baseline knowledge about PD was high (mean knowledge score = 89.4 on a scale of 0–100), and scores did not increase after reading My Degeneration (89.8). At baseline, participants were also moderately to highly confident (self-efficacy) that they could 1) explain to someone else what it is like to live with PD (mean score = 71.2 on a scale of 0–100), 2) communicate their concerns about PD to their doctors (mean = 83.0), 3) understand treatment options (mean = 79.1), 4) cope with the challenges of PD (mean = 68.9), and 5) find others who could relate to what they are experiencing with PD (mean = 58.7). After reading My Degeneration, self-efficacy scores rose slightly, but this increase was not statistically significant (P = 0.28).

Mental distress (as reflected by the emotional thermometer scores) in this cohort was fairly low (1–3 on a 1–10 scale), and there was no change postintervention. Likewise, hope was in the moderate range and did not change after reading the book, nor were there changes to participants’ worry and concern regarding impact of PD (Table 2).

Table 2:

Comparison of pre- to postintervention outcome measures

| Outcome | N | Prea | Posta | Changea | P value b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Knowledge (0–100) | 30 | 89.5 (86.1, 92.9) | 89.8 (86.5, 93.0) | 0.3 (–2.4, 3.0) | 0.929 |

| Self-efficacy (0–100) | 30 | 73.3 (67.6, 79.1) | 77.1 (72.3, 81.9) | 3.8 (–1.2, 8.8) | 0.283 |

| Distress (0–10) | 30 | 2.7 (1.8, 3.6) | 3.1 (2.1, 4.0) | 0.4 (–0.8, 1.5) | 0.436 |

| Anxiety (0–10) | 29 | 3.3 (2.4, 4.3) | 3.8 (2.7, 4.8) | 0.5 (–0.5, 1.5) | 0.392 |

| Depression (0–10) | 28 | 2.9 (1.7, 4.1) | 2.5 (1.8, 3.3) | –0.3 (–1.3, 0.6) | 0.560 |

| Anger (0–10) | 30 | 1.5 (0.8, 2.2) | 1.5 (0.8, 2.2) | 0.0 (–0.8, 0.9) | 0.870 |

| Quality of life (0–10) | 30 | 6.7 (6.0, 7.5) | 6.7 (6.1, 7.3) | 0.0 (–0.8, 0.7) | 0.863 |

| Hope (Herth Hope Index) (1–10) | 19 | 36.4 (33.8, 38.9) | 37.4 (35.2, 39.6) | 1.1 (–1.2, 3.3) | 0.328 |

| Hopefulness (1–10) | 29 | 7.2 (6.6, 7.9) | 7.2 (6.6, 7.8) | 0.0 (–0.5, 0.5) | 1.0 |

| Worry and concern (15–60) | 20 | 39.9 (35.5, 44.2) | 39.9 (36.3, 43.5) | 0.1 (–2.2, 2.3) | 0.963 |

| Attitudes toward comics (9–45) | 29 | 19.6 (17.7, 21.6) | 19.5 (17.1, 21.9) | –0.1 (–2.6, 2.3) | 0.577 |

The numbers in these columns refer to: mean (95% CI).

Wilcoxon signed rank test.

CI, confidence interval.

In analysis of covariates, little of significance emerged.

Qualitative Findings

In this analysis of the interview transcripts, the authors identified 4 main themes regarding the impact of My Degeneration on patients.

Theme 1: Reading My Degeneration validated people’s lived experiences with PD

Participants felt the book’s content validated the practical challenges and day-to-day struggles they face as people living with PD. They related to the frustrations articulated by Dunlap-Shohl and found some depictions cathartic and comforting:

I feel like I've always had my ducks in order. And now I feel like somebody came along and shot my ducks, and they’re all scattered everywhere and I can’t get them together. (Female; 63 years old; diagnosed 2008; NPS = 10)

I could just thumb through it and say, “Well, I can relate to that,”’ or “I can relate to that,” or “I understand this,” or “Now I’m going through this stage.” (Female; 73 years old; diagnosed 2017; NPS = 10)

. . . when he described an intense emotional reaction to something, kind of, you know, out of the blue—finding yourself weeping about something...I’ve been experiencing that without ever attributing it to Parkinson’s. And it was reassuring to know that that’s, you know, why, where that’s coming from. (Female; 67 years old; diagnosed 2004; NPS = 8)

In particular, participants appreciated Dunlap-Shohl’s willingness to honestly examine the darker sides of living with PD:

. . . one area that’s been kind of left silent is the depression aspect of it. At least that’s what I’ve been facing. There doesn’t seem to be a lot of recognition of that—that it is a major player in a Parkinson’s patient’s life. And he again, he definitely, you know, brought that out. (Male; 63 years old; diagnosed 2010; NPS not available)

Theme 2: The process of reading the book reinforced practical behaviors to support patients’ well-being, both in the present and in the future

Participants appreciated Dunlap-Shohl’s describing his own incremental adaptations to living with PD. This theme helped participants think more concretely about practical behaviors that might support their own well-being and resilience:

I got kind of a reminder that I need to be more conscious of things like exercise and speech therapy. (Male; 54 years old; diagnosed 2015; NPS = 10)

Probably will make me be more aware of things to ask and how to approach them and if they don’t suggest it, I’ll suggest it. Like next time I go back to see my doctor, I’m going to ask her about the [physical therapy], I’m going to ask her about speech . . . . (Female; 70 years old; diagnosed 2014; NPS = 9)

So, I think the book really strengthened my sense that I’ve really got to start planning aggressively for . . . the last part of my life. And how that works in terms of with my wife and all that. (Male; 63 years old; diagnosed 2010; NPS not available)

There was also a sense that participants gained specific medical knowledge that could influence their future care—for instance, by asking informed questions of their doctors on future visits, particularly about deep brain stimulation:

Well, I’ve been delaying the deep brain surgery because I didn’t feel it was necessary yet and I wasn’t increasing my medication or anything but I think it may have opened that discussion again. (Male; 70 years old; diagnosed 2009; NPS = 7)

Theme 3: There was value in sharing the book with others (ie, caregivers, family, friends) as a means of providing insight into the illness experience

Many participants said that, after finishing the book, they felt compelled to pass it along to the people closest to them. They viewed this act as serving to inform and educate, build greater understanding/empathy for the particular challenges of living with PD, and create opportunities for conversation:

When I finished reading it, the first thing I thought of was I really want my family and friends to read this because I think they’ll understand what I go through and why, you know, maybe sometimes I can’t do certain things. (Female; 60 years old; diagnosed 2009; NPS = 10)

Right now, I have my lady friend reading it so she’ll understand. She knew pretty well but sometimes when you say “this hurts” or whatever,. . . the book, the cartoon thing, explains it better than I can. She’ll read it and we’ll talk about it. Her input will be different than mine. (Male; 81 years old; diagnosed 1997; NPS = 9)

When . . . family members and friends . . . see when you’re well and you’re not . . . [t]his [comic] would really help fill them in [on] the reality of it. I mean, they just see me being tired, they don’t know about the anxiety and the depression and all the other stuff. (Male; 67 years old; diagnosed 2011; NPS = 9)

Beyond social circles, participants felt their health care teams would benefit from reading the book. Some readers recommended the book to hospital personnel:

I’ve gone a step beyond and can see how important it is for—I told the gals who run the support group at the hospital they should have a copy of it for themselves. Because I think that caregivers should read it. (Female; 84 years old; diagnosed 2017; NPS = 10)

Some participants did express hesitation about sharing the book with persons newly diagnosed with PD, as well as with children. There was a sense that the darker aspects of the content could be upsetting and create unduly negative expectations about the illness’s progression:

It probably could be very difficult for a newbie to read and anticipate some of these things. They might be hearing some of these things that they’re not really ready to hear with regard to the prognosis. But he only tells the truth. (Female; 69 years old; diagnosed 2002; NPS = 10)

Theme 4: The reading experience was emotionally and physically taxing

Although participants largely expressed feeling validated by the book’s unsparing depictions of living with PD, they also found it emotionally difficult. Part of the burden resulted from the comics medium itself, as participants felt specific cartoon images provocatively used by Dunlap-Shohl (eg, a scene where he contemplates committing suicide by offering himself to wild bears in the woods) were jarring (and hyperbolic):

This business about how Parkinson’s wants to take everything, from buttoning your shirt, which I have problems with sometimes, to the ability to talk and write legibly,. . . to smile, your income, your marriage, your family, it’ll want everything. I mean, when you start to think about it in those terms it’s pretty . . . scary. (Male; 54 years old; diagnosed 2015; NPS = 10)

With respect to the comics medium, some participants also felt the act of reading the graphic narrative was more physically taxing than a standard book:

I like the comic book style that he uses, although sometimes I found it was hard to read. My eyes are pretty bad right now. The font was kind of small for me. Sometimes I was reading things, and it didn’t make sense, and I had to re-read it a couple times . . . so that the brain could engage in some significant information intake. (Female; 69 years old; diagnosed 2002; NPS = 10)

You know what was hard to read? I constantly battled this—this may be part of the Parkinson’s—the comics. I kept questioning, am I reading them in the right way? In other words, you start in the top-left corner of the page, read left to right. But inadvertently, many times, I’d want to continue all the way across the page, to the second page. And it seemed like my mind was battling. Kind of disconcerting because I’m trying to think, I mean, if I did it once I had to do it ten times. Look at the paragraph before and then after each split to make sure it made sense that I was following it the right way. (Male; 63 years old; diagnosed 2010; NPS not available)

Others found the intellectual content of the book to be somewhat daunting and questioned whether it was too advanced for some readers:

[I think it was] written on a little bit too high of a level for the average person. (Female; 70 years old; diagnosed 2014; NPS = 9)

Mixed Methods Results

Mixed methods analysis revealed that participants’ perception of My Degeneration (as examined via differences in coding patterns) varied by gender. Of the 10 males interviewed in the study, 90% described that they felt emotionally validated by the book, whereas only 56% of the women indicated similar feelings of validation (Table 3).

Table 3:

Descriptive characteristics based on gender (column percentages)

| Variable | Men (N = 10) | Women (N = 16) | Row total (N = 26) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative coding patterns (no. of participants endorsing this code, %) | |||

| Likes comic format | 7 (70.0) | 12 (75.0) | 19 |

| Dislikes comic formata | 3 (30.0) | 4 (25.0) | 7 |

| Humor | 5 (50.0) | 6 (37.5) | 11 |

| Pessimism | 3 (30.0) | 9 (56.3) | 12 |

| Validating | 9 (90.0) | 9 (56.3) | 18 |

Percentages represent “column percentage.”

Not mutually exclusive with “likes” comics.

Analysis of Net Promotor Scores found that 12 participants were categorized as “endorsers,” 5 were “detractors,” and the remainder were categorized as “passives.” As expected, perceptions of, and responses to, the book differed by group category. Though positive comments dominated the dataset in their scope and detail, detractors expressed more negative perceptions. The use of dark humor by Dunlap-Shohl was particularly polarizing. Although half of the endorsers discussed their appreciation for Dunlap-Shohl’s humor, none of the detractors affirmed the use of humor or felt the comic was humorous in any way (Table 4).

Table 4:

Descriptive characteristics based on net promoter score

| Variable | Endorsers (N = 12) | Detractors (N = 5) | Missing NPS score (N = 2) | Row total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 4 (33.3) | 1 (20.0) | 3 (42.9) | 2 (100.0) |

| Female | 8 (66.7) | 4 (80.0) | 4 (57.1) | 0 (0) |

| Qualitative coding patterns (no. of participants endorsing this code, %) | ||||

| Likes comic format | 12 (100.0) | 2 (40.0) | 2 (100.00) | 19 |

| Dislikes comic formata | 0 (0) | 4 (80.0) | 0 (0) | 7 |

| Humor | 6 (50.0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50.0) | 11 |

| Pessimism | 3 (25.0) | 4 (80.0) | 0 (0) | 12 |

| Validating | 8 (66.7) | 3 (25.0) | 2 (100.0) | 18 |

Percentages represent “column percentage.”

Not mutually exclusive with “likes” comics.

NPS, Net Promoter Score.

For example, one endorser remarked how he enjoyed that Dunlap-Shohl

was able to take the disease and work through the hard things . . . but yet threw some comedy in there that kind of relieved some of the tension and pressure . . . (Male; 67 years old; diagnosed 2011; NPS = 9)

In contrast, a detractor noted that

some may think the format is vulgar or offending or be put off by it. He thinks Parkinson’s is a laughing matter. Why would someone put this in a comic book? (Male; 59 years old; diagnosed 2005; NPS = 5)

Relatedly, whereas endorsers embraced Dunlap-Shohl’s wit in depicting challenging situations, detractors were put off by how he focused too bluntly on negative and unpleasant aspects of living with PD:

I think he conveyed negative reality better than hope . . . it hit the nail on the head. But hitting the nail on the head doesn’t mean it’s a rosy picture. (Female; 72 years old; diagnosed 2013; NPS = 5)

Endorsers’ and detractors’ variance was primarily related to their divergent views about the use of dark humor and their like or dislike for the comic format itself.

Discussion

The use of comics-based material as health interventions is a growing area of research. Although My Degeneration is not the only comic dealing with PD (see A Cell’s Life; https://erccomics.com/comics/a-cells-life), the authors of this study were unaware of other studies investigating comics as an intervention for patients who have PD. That said, comics have been used in a variety of contexts for disease prevention and health promotion, including self-management of chronic conditions,20 support for informed decision-making,21,22 or promotion of organ donation.23 As interventions, comics have been shown to be particularly helpful for people who are less engaged or self-motivated.24

In the mixed methods study presented here, the authors explored the impact of using the graphic memoir My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s as an intervention for patients living with PD. Quantitatively, the authors investigated whether reading the book could increase knowledge, improve mental health, and alter attitudes about living with this degenerative disease. Qualitatively, the authors examined patients’ reactions to this book with regard to these same constructs and examined reasons why some endorsed the book but others did not.

The analysis of quantitative data indicated that reading My Degeneration had no statistically significant impact on participants’ knowledge, mental health, or attitudes. This finding may be influenced in part by the participants’ high educational level and long duration living with illness. Even so, as is often the case with mixed methods studies, the rich qualitative data provided information not captured by quantitative findings. Those who liked the book—the “endorsers”—revealed that it deeply resonated with them and helped them realize they were not alone with the disease. Many readers commented that Dunlap-Shohl’s story was in some ways their story—and that this was both practically and emotionally reassuring. Many participants appreciated the helpful tips Dunlap-Schohl provided for managing the illness and affirmed the importance of asserting oneself with practitioners and family members. These individuals found the book to be an effective and accessible way to share their experience with family and friends, and they believed that these groups should read it to get a better sense of what it is really like to have PD.

Reading the book was not always an easy or pleasant experience. Analysis of detractors’ comments suggested that Dunlap-Shohl’s bluntness and use of explicit examples from his life was sometimes off-putting, and his unvarnished—and at times comically hyperbolic—portrayal of PD was frightening. Most detractors did not appreciate the attempts at humor and disliked the comic format and its attendant challenges.

These findings add to a growing literature on the uses of graphic medicine in clinical settings.24,25 My Degeneration is but one example of myriad graphic pathographies that give voice to people’s illness experiences and other health challenges.26 As a multimodal medium that uses both words and images to communicate a story, comics connect differently (and often more deeply) with readers than other formats, an observation confirmed by many of the study participants. By employing visual metaphors, humor, and imagination, comics are particularly well-suited to depicting difficult, complex, and ambiguous subject matter27 and, in doing so, often break down communication barriers, explore taboos, and challenge the status quo.28 These very qualities can be both a source of power and a limitation of the medium, as not everyone will react the same to stories told in this manner.

In this regard, the present study revealed that My Degeneration appealed to some persons with PD but alienated others. Participants who seemed to appreciate and benefit most were males who enjoyed the medium of comics and/or those who had a wry sense of humor that makes space for laughter in dark situations. In contrast, people who seemed less likely to benefit from the book were those who did not have an affinity for the comic format, disliked dark humor, and had a pessimistic outlook in general. With this in mind, motivated clinicians could curate a library of stories from a variety of perspectives and styles, so as to promote a tailored approach to information sharing that avoids a one-size-fits-all mentality.

For practitioners considering the use of My Degeneration in a clinical setting, it would behoove them to identify in advance those patients who would be most receptive to the material. Doing so would require learning more about the patients’ preferences regarding stories, comics, and humor, but the payoff would be patients who felt less alone with the illness. Even for those who did not enjoy the book, reading My Degeneration neither increased anxiety nor adversely affected worries about the disease, so there is no apparent harm in recommending this different kind of intervention with patients.

Limitations

Like all research, this study had limitations. First, the sample size was small, and the authors recruited participants from a single institution and practitioner. Future research could focus on recruiting a larger and more diverse sample, as this would improve generalizability. Second, newly diagnosed patients were excluded because clinicians in this initial study expressed concern that this book would not be appropriate for patients at that stage of their illness, so the authors lacked data about this population. Of note, Dunlap-Shohl intended the book to be “guardedly optimistic” (MJG personal communication, April 15, 2024) and excluding newly diagnosed individuals from the study could be viewed as paternalistic. Whether newly diagnosed individuals would benefit or be harmed by the book is an empirical question that could be settled with further research. Third, this study's cohort was highly educated, and this may reflect who has the resources to seek treatment in this specialized environment. Though difficult to speculate about those who did not participate, it is possible that less-educated individuals were disinclined to participate in a study that used a book as an intervention. Whether less-educated individuals would benefit from a comic is an area ripe for further analysis. This study’s sample was also limited by a lack of racial and ethnic diversity, a dynamic reflecting the region in which the study took place. That said, the study had numerous strengths, including an innovative research question and a robust mixed methods design that included detailed comments by the participants themselves.

Moving forward, the promising findings suggest that a fertile area of future inquiry would be to focus on the value of this graphic memoir for family members of patients with PD. Because many participants indicated they thought their spouses, children, or friends should read the book, it would be worthwhile to see if reading did in fact change loved ones’ knowledge and attitudes toward PD and, ultimately, whether this had an impact on the QoL of the patients themselves. Future research could assess how persons with PD share the book, and the effects the book may have across social networks.

Conclusion

My Degeneration is a graphic memoir with potential to benefit select patients with PD. As a story told using a wry wit, a dark sense of humor, visual metaphors, and examples from Dunlap-Shohl’s own life, the book may not appeal to all readers. However, for those who like comics, have a similar comedic sensibility, and are not overly pessimistic, the book holds promise as a helpful complement to traditional PD care, and clinicians could recommend it with enthusiasm as a means of helping educate and connect with patients.

Supplementary Material

online supplementary file 1:

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Michael J Green, MD, participated in conceptualization of the study design, drafting and editing the manuscript, overseeing the analysis of data, and submission of the final manuscript. Sol De Jesus, MD, participated in data acquisition, referral of study participants, and drafting and editing the manuscript. Daniel R George, PhD, and Kimberly R Myers, PhD, participated in conceptualization of the study design, analysis of qualitative data, and drafting and editing the manuscript. Margaret Hopkins, MA, participated in project administration, data acquisition, and drafting and editing the manuscript. Erik Lehman, MS, participated in study design and quantitative data analysis. Lauren Van Scoy, MD, participated in study design, conceptualization of the mixed methodology, and drafting and editing the final manuscript. Bethany Snyder, MPH, participated in qualitative data analysis and drafting and editing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the Translational Brain Research Center at Penn State College of Medicine, in Hershey, PA. When My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s was published in 2015 by Penn State University Press, Michael J Green, MD, and Kimberly R Myers, PhD, were noncompensated members of the Graphic Medicine editorial collective for the book series.

Data-Sharing Statement: Data are available upon request. Readers may contact the corresponding author to request underlying data.

References

- 1.Vescovelli F, Sarti D, Ruini C. Subjective and psychological well-being in Parkinson’s disease: A systematic review. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;138(1):12–23. 10.1111/ane.12946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Charon R. Narrative medicine: A model for empathy, reflection, profession, and trust. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1897–1902. 10.1001/jama.286.15.1897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green MJ, Myers KR. Graphic medicine: Use of comics in medical education and patient care. BMJ. 2010;340:c863. 10.1136/bmj.c863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunlap-Shohl P. My Degeneration: A Journey Through Parkinson’s. The Pennsylvania State University Press; 2015. 10.1515/9780271085791 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Myers KR, George DR, Huang X, et al. Use of a graphic memoir to enhance clinicians’ understanding of and empathy for patients with Parkinson disease. Perm J. 2019;24:19.060. 10.7812/TPP/19.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Creswell J. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beidler P. My Degeneration, A Journey Through Parkinson’s. [Internet] Mercer I, ed. Northwest Parkinson’s Foundation; Accessed 15 January 2016. https://nwpf.org/stay-informed/blog/book-review-my-degeneration/." [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goidsenhoven L, Dunlap-Shohl P. My Degeneration, A Journey through Parkinson’s. 2016:88–91. 10.1515/9780271085791 [DOI]

- 9.Moore S, Knowles S. Beliefs and knowledge about Parkinson’s disease. E-JAP. 2006;2(1):15–21. 10.7790/ejap.v2i1.32 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A. Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Pajares F, Urdan T, eds. Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. 5., Information Age Pub., Inc; 2006:307–337. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harju E, Michel G, Roser K. A systematic review on the use of the emotion thermometer in individuals diagnosed with cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28(9):1803–1818. 10.1002/pon.5172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: Development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17(10):1251–1259. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1992.tb01843.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoner M. Measuring hope. In: Frank-Stomborg M, Olsen S, eds. Instruments for Clinical Health-Care Research. 3rd ed. Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2004:215–228. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hosler J, Boomer KB. Are comic books an effective way to engage nonmajors in learning and appreciating science? CBE Life Sci Educ. 2011;10(3):309–317. 10.1187/cbe.10-07-0090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osgood C, Suci G, Tannenbaum P. The Measurement of Meaning. University of Illinois Press; 1957. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reichheld F. The one number you need to grow. Harv Bus Rev. 2003;81(12):46–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsden P, Samson A, Upton N. Advocacy drives growth: Customer advocacy drives UK business growth. Brand Strategy. 2005;198:45–47. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glaser BG. The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems. 1965;12(4):436–445. 10.2307/798843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fetters M, Curry L, Creswell J. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs—Principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 pt 2):2134–2156. 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tjiam AM, Asjes-Tydeman WL, Holtslag G, et al. Implementation of an educational cartoon (“the Patchbook”) and other compliance-enhancing measures by orthoptists in occlusion treatment of amblyopia. Strabismus. 2016;24(3):120–135. 10.1080/09273972.2016.1205101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Furuno Y, Sasajima H. Medical comics as tools to aid in obtaining informed consent for stroke care. Medicine. 2015;94(26):e1077. 10.1097/MD.0000000000001077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brand A, Hornig C, Crayen C, et al. Medical graphics to improve patient understanding and anxiety in elderly and cognitively impaired patients scheduled for transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Clin Res Cardiol. 2023:38117299. 10.1007/s00392-023-02352-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Irwin J, Roughley M, Smith K. “To donate or not to donate? That is the question!”: An organ and body donation comic. J Vis Commun Med. 2020;43(3):103–118. 10.1080/17453054.2020.1770059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alemany-Pagès M, Azul AM, Ramalho-Santos J. The use of comics to promote health awareness: A template using nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Eur J Clin Invest. 2022;52(3):e13642. 10.1111/eci.13642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mendelson A, Rabinowicz N, Reis Y, et al. Comics as an educational tool for children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2017;15(1):69. 10.1186/s12969-017-0198-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graphic Medicine . Graphic Medicine International Collective. Accessed 25 February 2022. https://www.graphicmedicine.org/comic-reviews/

- 27.Williams ICM. Graphic medicine: Comics as medical narrative. Med Humanit. 2012;38(1):21–27. 10.1136/medhum-2011-010093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Venkatesan S, Murali C. Graphic medicine and the critique of contemporary U.S. healthcare. J Med Humanit. 2022;43(1):27–42. 10.1007/s10912-019-09571-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

online supplementary file 1: