Abstract

Previous evidence has suggested that SPA1 is a signal transduction component that appears to require phytochrome A for function in seedling photomorphogenesis. Using digital image analysis, we examined the time course of growth inhibition induced by red light in spa1 mutants to test the interpretation that SPA1 functions early in a phyA-specific signaling pathway. By comparing wild-type and mutant responses, we found that SPA1 caused an increase in hypocotyl growth rate after approximately 2 h of continuous red light, whereas the onset of phyA-mediated inhibition was detected within several minutes. Thus, SPA1-dependent growth promotion began after phyA started to inhibit growth. The action of SPA1 persisted for approximately 2 d of red light, a period well beyond the time when the phyA photoreceptor and its influence on growth have both decayed to undetectable levels. Also, SPA1 promoted growth for many hours in the complete absence of a light stimulus when red-light-grown seedlings were shifted to darkness. We propose that SPA1 functions in a light-induced mechanism that promotes growth and thereby counteracts growth inhibition mediated by phyA and phyB. Our finding that spa1 seedlings do not display growth promotion in response to end-of-day pulses of far-red light, even in a phyA-null background, supports this interpretation. Combined, these results lead us to the view that the rate of hypocotyl elongation in light is determined by at least two independent, opposing processes; an inhibition of growth by the phytochromes and a promotion of growth by light-activated SPA1.

The phytochromes are a family of photoreceptors that mediate many aspects of plant growth and development (Neff et al., 2000; Smith, 2000). They are encoded by a small multigene family in Arabidopsis designated PHYA through PHYE (Sharrock and Quail, 1989; Clack et al., 1994). Soon after this gene family was identified, mutations in some of the members were isolated and used in studies of hypocotyl growth that indicated phyB is primarily responsible for the effects of continuous red light (Rc), whereas phyA exclusively regulates responses to continuous far-red (FR) light (FRc; Smith, 1995; Quail, 1998; Whitelam et al., 1998). Screens for photomorphogenesis-related phenotypes also identified numerous downstream components specific to red-light and/or FR-light sensing (for review, see Neff et al., 2000), and very recent findings have further expanded this list of loci important to phyA and phyB signaling (PAT1, Bolle et al., 2000; EID1, Büche et al., 2000; HFR1, Fairchild et al., 2000; RSF1, Fankhauser and Chory, 2000; SUB1, Guo et al., 2001; SRL1, Huq et al., 2000; and REP1, Soh et al., 2000). The rapidly growing number of components implicated thus far in phytochrome signal transduction clearly points to a growing need for understanding how they function and where they are placed in a phytochrome-mediated light-signaling network.

SPA1 is one such downstream element that is thought to be a component of phyA-specific signal transduction (Hoecker et al., 1998). It was identified by a recessive mutation that suppresses the long-hypocotyl phenotype of an impaired phyA photoreceptor, yielding a seedling with a normal hypocotyl length when grown under FRc. In a wild-type background, the spa1 mutation results in hypersensitivity to both Rc and FRc, suggesting that SPA1 acts normally as a negative regulator of light signaling. SPA1 is a WD-repeat protein that shares some sequence similarity to protein kinases, and appears to be nuclear localized (Hoecker et al., 1999). The current model maintains that SPA1 acts early and specifically in phyA signal transduction. This proposition is supported by the observation that SPA1 appears to require phyA for its function and participates in other aspects of de-etiolation such as anthocyanin formation and FR-preconditioned block of greening in continuous white light. In addition, evidence that spa1 mutants are hypersensitive to Rc resulting from the action of phyA has led to the idea that SPA1 may play a key role in confining the sensory specificity of phyA to FRc. This and observations that spa1 mutations did not affect other phyB-meditated responses such as flowering time provided additional evidence that SPA1 is specific to phyA-mediated signal transduction.

It is important to emphasize that the interpretation of most photomorphogenic mutants including spa1 has rested upon the assessment of phenotypes visible after several days of growth under specific light conditions. Although this has clearly been a productive approach, it unavoidably overlooks features of the response that occur during the experimental period. We reasoned that monitoring the progression of the response under study could expose important information about how photoreceptors and putative signaling molecules act during photomorphogenesis. To access this period of potentially important information, we assembled an image analysis system having the sensitivity required to monitor the hypocotyl growth rate of Arabidopsis seedlings. Combined with the ability to deliver precisely defined light treatments, this technology enables accurate studies of the kinetics of light-regulated growth with resolution on the order of a few minutes. With this approach, we were able to show that the cryptochrome 1 blue-light receptor (cry1) contributes to growth inhibition induced by blue light but not until 45 min after the response has begun (Parks et al., 1998). Some other unidentified photoreceptor is responsible for initiating the first, rapid phase of growth inhibition. This meaningful complexity was necessarily undetected by standard hypocotyl length measurements. In particular regard to the present work are our similar studies of the control of hypocotyl growth in phytochrome mutants (Parks and Spalding, 1999). We recently demonstrated that even though the majority of the response to Rc is dictated by phyB, the initial period of light treatment is perceived exclusively through phyA. This control of growth in Rc is balanced so that as the influence of phyA begins to fade 3 h after the onset of Rc, it is supplanted by an increasing influence of phyB. Thus, our analysis of response kinetics has revealed an unexpected coordinated action of photoreceptors in the earliest stages of both blue- and red-light-induced aspects of photomorphogenesis.

These findings on the timing and duration of phyA and phyB action in Rc suggested to us a means of testing a proposed role of SPA1 as a component that acts early and negatively in the phyA-specific signaling pathway. Analyzing the time courses of growth inhibition displayed by spa1 and wild-type seedlings showed the time course of SPA1 action, which was then compared with the time courses of phyA and phyB actions. Our findings presented here will necessitate a reassessment of SPA1's role in phyA signaling and simultaneously give new insight into the photocontrol of stem elongation for an emerging seedling. A view that hypocotyl growth rate is controlled by competing positive and negative influences, both induced by light, is supported by this study.

RESULTS

The Development of SPA1 Influence on Growth Rate in Rc Light

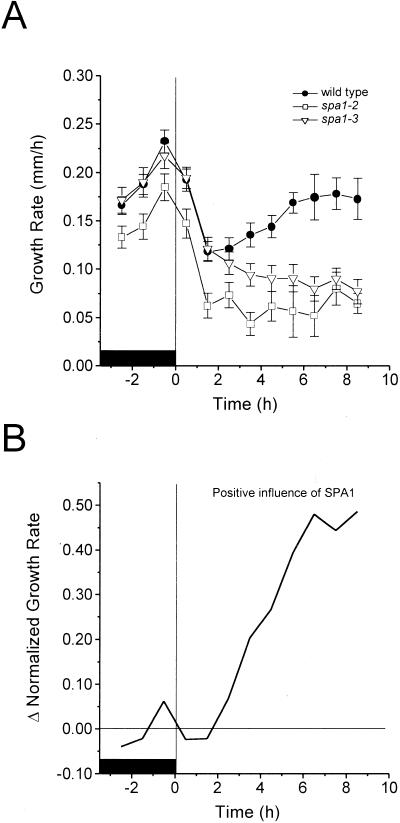

Rc was chosen as the stimulus because our previous kinetic studies indicated that it inhibits growth via phyA for 3h and thereafter via phyB (Parks and Spalding, 1999). If SPA1 functions specifically in downstream phyA signaling, it should exert its effect within the initial 3 h of Rc. Figure 1A shows the growth responses of two independent spa1 alleles and the parental wild type when subjected to Rc. The initial decrease in growth rate induced by Rc, previously shown to be mediated solely by phyA during the first 3 h of illumination, was similar in the wild type and two spa1 mutants. Thus, the spa1 mutations did not affect the ability of phyA to inhibit growth. The two alleles of spa1 displayed similar patterns of response although spa1-2 grew more slowly in general. Growth slowed to approximately 50% of the growth rate in darkness after 1.5 h of continuous illumination in all genotypes. The effect of the spa1 mutation was detected after approximately 1.5 h, with spa1-2 and spa1-3 displaying progressively slower growth rates, whereas the wild type began to grow faster. The form of the mutant response was similar over a fluence rate range of 2.5 to 250 μmol m−2 s−1, although lower fluence rates of Rc produced less growth inhibition (data not shown). From these time series of growth rate measurements, the contribution of wild-type SPA1 to hypocotyl growth as a function of time can be determined by an analytical method described in “Materials and Methods.” Subtracting the spa1-3 growth response time series from that of the wild type yielded a curve showing the development of SPA1 influence on growth before and after the onset of Rc (Fig. 1B), and this result was essentially the same for spa1-2 (data not shown). The influence of SPA1 on growth was negligible in the dark but became detectable after approximately 2 h of Rc. SPA1 influence increased linearly over time for at least the next 7 h. The partial escape from inhibition displayed by wild-type seedlings after approximately 2 h of Rc (Fig. 1A) apparently results from a positive influence on growth by SPA1 that counteracts phytochrome-mediated inhibition.

Figure 1.

Growth responses of spa1 and wild-type seedlings to Rc. Results are shown for two independent mutant alleles of spa1. Red light fluence rate was 250 μmol m−2 s−1. A, Sample sizes for wild type, spa1-2, and spa1-3 were 37, 24, and 24, respectively. Bars represent one se. B, The derived kinetics of SPA1 influence on growth rate. The time series in A were normalized to 1 for the average rate of growth in darkness. The normalized series for spa1-3 was then subtracted from the wild type as described in “Materials and Methods.” For A and B, the black box represents the period of growth in darkness.

SPA1 and phyB Function Independently of Each Other

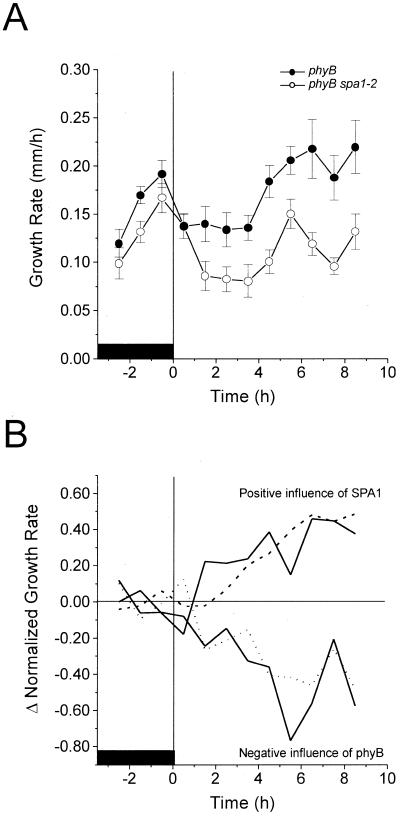

Our finding that SPA1 promoted growth during a period in which phyA has no detectable influence seems inconsistent with SPA1 functioning as an early acting component of a phyA-specific signal transduction chain leading to inhibition of hypocotyl elongation. SPA1 had its greatest impact on growth during a time period when phyB acts most strongly (Parks and Spalding, 1999). This opened the possibility that SPA1 acts downstream of phyB such that its influence could require phyB activity. To test this, the growth responses to Rc of a phyB mutant and a double mutant lacking both phyB and SPA1 (phyB-1 spa1-2) were measured and are displayed in Figure 2A. The phyB-1 spa1-2 double mutant showed more inhibition in Rc than phyB-1, but was less inhibited by Rc than the spa1-2 mutant (see Fig. 1A). Subtracting the phyB-1 spa1-2 time series from that of phyB-1 (Fig. 2B) isolated the action, or influence on growth of SPA1 in a background lacking phyB. The close agreement of this resultant curve (upper solid line) with the SPA1 action time course obtained in a normal phyB background (dashed line) indicates that the presence or absence of phyB did not significantly influence the activity of SPA1 during the 10-h irradiation with Rc (Fig. 2B). Therefore, SPA1 affects hypocotyl growth independently of phyB.

Figure 2.

Growth response of phyB and phyB spa1 seedlings to Rc. Red light fluence rate was 250 μmol m−2 s−1. A, Sample sizes for single and double mutant were 11 and 12, respectively. Bars represent one se. B, The derived kinetics of SPA1 and phyB influences as they develop in the absence of phyB and SPA1, respectively. The time series in A and Figure 1A were normalized to 1 for the average rate of growth in darkness. The normalized time series for phyB-1 spa1-2 was then subtracted from that of either phyB-1 or spa1-2 (from Fig. 1A) to expose the increasing influence of SPA1 or phyB in the absence of phyB or SPA1, respectively (solid lines). For comparisons, the normalized time series for phyB-1 was subtracted from the wild type (Fig. 1A) to show the increasing phyB influence (RLD background) in the presence of SPA1 (dotted line), whereas the data showing the development of SPA1 influence in the presence of phyB are replotted from Figure 1B (dashed line). For A and B, the black box represents the phase of growth in darkness.

We were also able to use these time series to quantify the time course by which phyB influences growth in the absence of SPA1 (Fig. 2B). By subtracting the response of phyB-1 spa1-2 from that of spa1-2 shown in Figure 1A, the resultant curve (lower solid line) shows that in a background lacking SPA1, phyB begins to inhibit growth after approximately 1 h and that this effect progresses to approximately 70% inhibition. Previous studies had indicated that phyB begins to act after approximately 3 h of Rc (Parks and Spalding, 1999). The difference between these two reported lag times for phyB action indicates that either SPA1 influences the activity of phyB or that ecotypic differences exist between RLD used here and Landsberg used previously. Because we found no noteworthy differences between this resultant curve and one showing the influence of phyB in a wild-type RLD background (Fig. 2B, dotted line), these data indicate that SPA1 functions similarly with or without phyB. Therefore, the functions of SPA1 and phyB appear mutually independent.

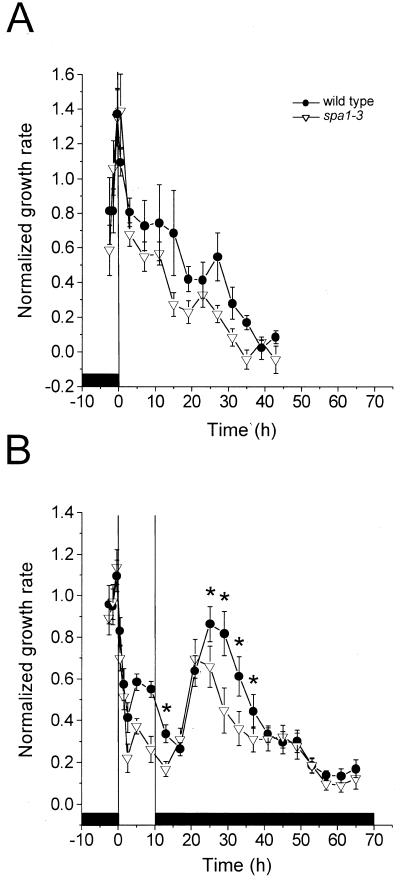

SPA1 Influences Growth in the Absence of Light Signaling

The results presented to this point indicate a role for SPA1 as an independently functioning positive regulator of growth for the following reasons. First, the influence of SPA1 on growth rate during Rc treatment extended beyond the time period (first 3 h) over which phyA inhibits growth, and it persisted strongly during a time when phyA has been degraded substantially. Second, although the influence of SPA1 extended into a period where phyB is known to exert primary control on growth inhibition, there was no indication that SPA1 or phyB influence each other. Although previous work found that the induction and production of SPA1 depends on phyA (Hoecker et al., 1999), the above results suggest that SPA1 function is uncoupled from subsequent downstream phyA signaling. This prompted us to test whether continuous light input is required for the maintenance of SPA1 function, or if light-activated SPA1 can sustain its influence on growth independent of persistent light signaling. We compared the growth rates of wild-type and spa1-3 seedlings over an extended period before and after a limited exposure to red light. Figure 3 shows the growth rate time series acquired for both wild-type and spa1-3 seedlings that were either maintained in Rc for approximately 2 d or that were treated with 10 h of red light before return to darkness for 2 d. As was seen in Figure 1, red light initially led to similar growth inhibition in both genotypes until approximately 2 h when spa1-3 seedlings began to show greater inhibition of growth rate (Figs. 3A and 3B). For seedlings that were maintained in Rc, growth continued to decrease with time until approximately 40 h when both genotypes had essentially stopped growing (Fig. 3A). Over this time period in Rc light, the parental wild type always grew more rapidly than spa1-3 seedlings, again demonstrating that the positive influence on growth rate of SPA1 persisted during long-term light treatments. When wild-type and spa1-3 seedlings were returned to darkness after a 10-h red light treatment, the difference in growth rates between these genotypes was maintained for approximately the first 5 h in darkness before the growth of both seedling groups began to accelerate (Fig. 3B). The lag time for the acceleration was longer for the wild type than for spa1-3, but the two genotypes displayed similar growth rates during the ensuing 5 h of faster growth. However, following this growth spurt, and approximately 10 h after the seedlings had been returned to darkness, wild-type seedlings again grew faster than spa1-3, and this difference persisted over the next 30 h as growth slowed. Statistical analysis confirmed that the growth rates for wild-type and spa1-3 seedlings were significantly different in the second phase of darkness (P < 0.05) before and for approximately 16 h after the postillumination growth burst. These data indicate that the influence of SPA1 on growth rate was detectable for more than a day following the removal of all light stimuli.

Figure 3.

Long-term growth responses of spa1 and wild-type seedlings to continuous or limited red light. A, The growth responses of wild type and spa1-3 to Rc illumination. Sample sizes for wild type and spa1-3 were 8 for each genotype. B, The long-term measurement of growth for wild-type and spa1-3 seedlings that received a 10-h red light treatment. Sample sizes for wild type and spa1-3 were 16 and 18, respectively. For A and B, the bars represent one se and the red light fluence rate was 250 μmol m−2 s−1. All time series were normalized to 1 for the average rate of growth in darkness. The black boxes represent the periods of growth in darkness. The symbol legend applies to A and B. Asterisks in B denote points in the second phase of darkness that are significantly different to a confidence level of P < 0.05.

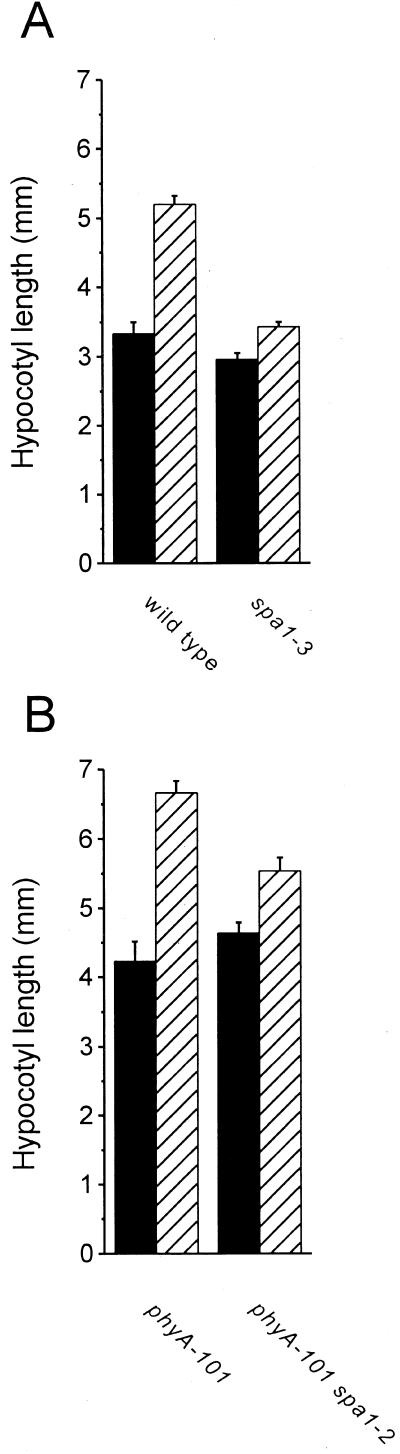

spa1 Seedlings Lack an End-of-Day (EOD)-FR Response

Wild-type seedlings grown under a light/dark photocycle grow taller if the light phase of each cycle ends with a brief FR pulse (Smith, 1994). Studies of this EOD-FR response using photoreceptor mutants have shown that seedlings lacking phyB do not grow taller in response to an EOD-FR treatment (Parks and Quail, 1993). It may be that a phyB mutation or treatment of wild-type seedlings with an EOD-FR pulse reduces PfrB-induced growth inhibition sufficiently to allow a concomitant growth-promoting influence to lengthen the hypocotyl. The source of this positive influence could be the abundant and persistently active SPA1 now present in these light-grown seedlings. We reasoned that if SPA1 were part of a growth promotion that antagonizes phyB-dependent growth inhibition, then spa1 seedlings that are deficient in this promotive influence should be defective in the EOD-FR response. Figure 4A shows the lengths of wild-type and spa1-3 hypocotyls in seedlings grown in light/dark cycles with and without a 15-min FR treatment at the end of each light phase for 4 d. Although wild-type seedlings displayed a clear response to EOD-FR by growing taller compared with controls, spa1-3 did not respond similarly to the same FR treatment, indicating that SPA1 acts as a component of a photomorphogenic response in which phyA has no known role.

Figure 4.

EOD-FR responses of Arabidopsis photomorphogenic mutants. A, Comparison of the EOD-FR response in wild-type versus spa1-3 seedlings. B, Comparison of the EOD-FR response in phyA-101 versus phyA101 spa1-2 mutant seedlings. Seedlings were grown on vertical plates as described in “Materials and Methods.” After planting and storage for 2 d at 4°C, plates were placed under fluorescent white lamps for 1 d at 25°C. The experimental groups (hatched bars) were then treated with 15 min of FR light before removal to darkness, while control groups (solid bars) were immediately placed in darkness. All plates remained in darkness for an additional 13.75 h before subsequent treatment with 10 h of white light. Following this period of growth in white light, experimental and control groups were again transferred to darkness according to the protocol stated above. This cycle was repeated through four rounds of darkness. Digital images of the seedlings were recorded at the end of the experiment and seedling hypocotyl lengths were measured as described in “Materials and Methods” using analysis software. Minimum sample sizes for each group were 11. Error bars represent one se.

These data pointing to a role for SPA1 in the EOD-FR response seemed at odds with the previous demonstration that phyA-null mutants display a normal EOD-FR response (Parks and Quail, 1993) because activation of SPA1 is thought to require phyA (Hoecker et al., 1999). According to the interpretation of the data presented here, one would not expect a phyA-null mutant to display a normal EOD-FR response because it should also be deficient for functional SPA1. This apparent inconsistency might be explained if SPA1 could be partially and sufficiently activated by a different photoreceptor over the course of long-term growth in light to affect this particular response. In support of this possibility, we found that a phyA-null spa1-2 double mutant was also deficient in the EOD-FR response (Fig. 4B), indicating that the normal EOD-FR response seen in the single phyA-null mutant occurred as a result of SPA1 acting in these seedlings containing no phytochrome A.

Together, these findings indicate a role for SPA1 in the EOD-FR and suggest that this response results from a change in the balance between two opposing and mutually independent influences on growth rate. In wild-type seedlings, a terminal FR treatment will rapidly convert phyB primarily to the inactive Pr form. This treatment would reduce the inhibitive influence of phyB on growth so that the promotive influence of SPA1 becomes more prominent, resulting in a greater net growth rate during the dark period for these FR-treated seedlings.

DISCUSSION

The goal of the studies reported here is an understanding of the hypocotyl growth phenotype resulting from the spa1 mutation. In an otherwise wild-type background, this mutation renders hypocotyls more sensitive to red light, leading to seedlings with shorter hypocotyls. One model originally proposed to explain this phenotype postulated that SPA1 negatively regulates phyA signaling so that removal of SPA1 by mutation would enhance the inhibitory action of phyA on hypocotyl growth. Based on this model, one would predict that a kinetic examination of SPA1 would find it acting during the phyA-dependent phase of growth inhibition, which was previously found to begin within minutes of Rc and end 3 h later (Parks and Spalding, 1999). However, the results obtained here with new high-resolution techniques for measuring growth indicate that SPA1 does not begin to affect growth until approximately 2 h of Rc and its effect persists for many hours after phyA control of growth has ceased. SPA1 action was found to increase as both the phyA photoreceptor and its influence on growth decayed to undetectable levels (Parks and Spalding, 1999). Furthermore, SPA1 clearly acted for many hours in the complete absence of light (Fig. 3B), and in the EOD FR response where phyA has no detectable contribution (Fig. 4). To reconcile these observations with the original model requires invoking a strong function for trace amounts of phyA that may remain after hours of Rc, as well as signaling by this trace pool that persists for hours in the absence of light.

We believe the data better fit a model in which SPA1 functions independently as a positive regulator of growth. Once SPA1 has been induced and activated by phytochrome, it acts subsequently to promote growth persistently and counteract the inhibitory influence of the phytochromes. A role for SPA1 acting in this manner represents the simplest and least complicated explanation of our data. This interpretation differs importantly from the interpretation that considers SPA1 to be a component that functions early in a phyA-specific signaling pathway leading to growth inhibition. Although it is correct to view SPA1 as a component of phyA-specific signaling in the sense that phyA can activate SPA1, our present data oppose a role for SPA1 as a negative regulator of subsequent downstream phyA signaling.

The present data showing how SPA1 is necessary for a normal EOD-FR response also favor a mechanism in which SPA1 acts as a positive growth regulator. The findings here indicating that SPA1 can function in the absence of phyA (Fig. 4B) suggest that SPA1 acts independently of phyA to promote growth. SPA1 appears to require light in order to function because spa1 mutants have no phenotype in darkness. However, its activation by light does not appear to occur strictly through phyA, nor does it appear to regulate a phyA-specific signaling pathway because it affects the outcome of a response in which phyA has no known role.

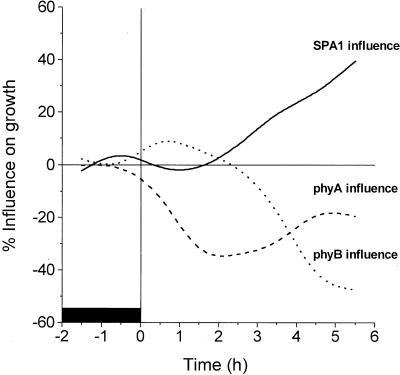

The growth-promoting role for SPA1 does not explain the rapid elongation of etiolated seedlings because activated SPA1 is not present in plants that have never been exposed to light and because spa1 mutants grown in darkness do not differ phenotypically from wild type. Thus, SPA1-dependent growth promotion appears to be an exclusive characteristic of de-etiolated seedlings, and therefore the process of de-etiolation includes a shift to a SPA1-dependent mechanism for controlling the rate of hypocotyl elongation. The activation of phytochromes by light not only leads to the onset of growth inhibition, but also triggers a separate light-dependent signal cascade that causes the promotion of growth through the action of SPA1. In this sense, therefore, the phytochromes appear to lie at the beginning of a set of signaling steps that eventually produce antagonistic results. These opposing influences on growth are diagrammed in Figure 5. Here, we see that the influence of phyA on growth acts first and negatively (inhibition) before it is succeeded by the negative influence of phyB, which appears after approximately 3 h of growth in Rc. The transition to phyB-regulated growth inhibition is joined at approximately the same time by the light-dependent development of a growth-promoting SPA1 influence. The presence of these opposing influences on growth in light-grown plants draws further distinction between the growth mechanics of etiolated versus green seedlings. The introduction of a light-induced positive growth regulator indicates that viewing growth in the light as a partially inhibited “dark state” of growth is too simplistic and incomplete. Rather, the growth of a green seedling actually represents a balance between new and opposing cellular processes that are both induced by light and result in a net rate of elongation that is lower than the rate in darkness.

Figure 5.

Time course for the changing degrees of influence on growth in Rc exerted by phyA, phyB, and SPA1. Data used to generate the kinetics of influence for phyA and phyB were taken from Parks and Spalding (1999) and converted into a percent influence on growth in the same manner described in Figure 1 and “Materials and Methods.” The curve for the progression of SPA1 influence is replotted from Figure 1. All curves were generated from the data using a cubic B-spline connection. The fluence rate of red light was 250 μ mol m−2 s−1. The black box represents the phase of growth in darkness.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Lines

The RLD ecotype of Arabidopsis was used for all experiments. Wild-type and spa1-3 seed were generously provided by Peter H. Quail (Plant Gene Expression Center, Albany, CA). The phyA spa1 double mutant was produced as described previously (Hoecker et al., 1998). The phyB spa1 double mutant was produced by crossing spa1-2 phyA-105 (ecotype RLD) to phyB-1, which had been backcrossed into the RLD background at least twice. In the F2 generation, plants with the genotype PHYA PHYA phyB-1 phyB-1 were identified using restriction site polymorphisms generated by the phyA-105 (Hoecker et al., 1998) and phyB-1 mutations. To determine the genotype at the SPA1 locus, PHYA PHYA phyB-1 phyB-1 F3 seedlings were grown in FRc (1 μmol m−2 s−1) and lines that segregated for the spa1 mutation and thus had broken the linkage between the loci SPA1 and PHYB were identified. Progeny from homozygous SPA1 wild-type or spa1 mutant siblings were used in the experiments as phyB or phyB spa1 mutants, respectively. These lines are also homozygous mutant for the erecta mutation, which is very closely linked to phyB-1.

Growth Measurements and Light Treatments

Seeds were planted and seedlings grown on vertical petri plates containing 1% (w/v) agar supplemented with 1 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm KCl. After incubation in darkness at 4°C for at least 2 d, seedlings were grown for approximately 1 d in darkness at 24°C, at which point they were approximately 1 mm tall. They were gently lifted from the agar surface and transferred to a fresh plate containing the same agar medium to form a row of developmentally uniform seedlings. This plate with seedlings was then placed vertically in a mount that held the row of seedlings horizontal and perpendicular to the optical path of a CCD camera (EDC-1000N; Electrim, Princeton, NJ) equipped with a close-focus zoom lens (D52274; Edmund Scientific, Barrington, NJ) and interfaced with a computer. Backlighting the seedlings with diffuse irradiation from an infrared light-emitting diode (peak output at 948 nm) produced the images that were acquired by the computer at user-specified time intervals before and during the red light treatment. This apparatus, capable of achieving a resolution of 5 μm per pixel, was described previously in a related study (Parks and Spalding, 1999).

A bank of light-emitting diodes (QB13105-670-735; Quantum Devices, Barneveld, WI) supplied the actinic red (670-nm) illumination from above. Cool-white fluorescent tubes (F20T12/CW, Sylvania, Danvers, MA) provided white irradiation (60 μmol m−2 s−1) for EOD-FR experiments. FR irradiation at a fluence rate of 0.4 μmol m−2 s−1 was supplied by a fluorescent bulb (F20T12/232/VHO, Sylvania) filtered through one layer of FR-transmitting Plexiglas (cutoff at 690 nm, FRS700, Westlake Plastics, Lenni Mills, PA).

Analytical Method

Hypocotyl lengths were measured manually from the digital images using analysis software (Image Tool version 1.28, University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio). Growth rate at any given time was calculated from the amount of elongation that occurred over the time interval separating successive digital images. The plots of these hypocotyl growth rates versus time are referred to hereafter to as a response time series. For wild-type seedlings, such time series may be viewed as the result of all light-dependent growth regulatory activities combined. A simple expression can be written to represent the time series of the wild-type growth response:

|

1 |

where GRWT(t) represents the response time series of wild-type seedlings. The contribution of phyA to the wild-type response at each point in time is given by phyA(t); the contributions of phyB and SPA1 are similarly represented. All other entities that contribute to the growth response in a wild-type seedling are represented by etc. A plant lacking functional SPA1, for example, would be represented as in Equation 1 except the SPA1(t) term would be absent (Eq. 2). Subtracting Equation 2 from Equation 1 isolates the time course of SPA1's contribution to the wild-type response:

|

A plot of the difference displays the time series of SPA1 action. To facilitate this analytical approach, the response time series were first normalized to 1 for the average rate of growth in darkness. Normalization of the data enables direct comparisons of independent trials and is a legitimate practice because all genotypes consistently accelerated to a growth rate of approximately 0.2 mm h−1 before the onset of illumination. This analytical approach is also based on an assumption that the entities under consideration act independently, that removing one component by mutation does not alter the activity or levels of others to a significant degree. The results presented provide evidence that this assumption is valid in the case of SPA1.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (grant no. 99–01833 to B.M.P. and E.P.S.) and by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (grant to U.H.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Bolle C, Koncz C, Chua N-H. PAT1, a new member of the GRAS family, is involved in phytochrome A signal transduction. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1269–1278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Büche C, Poppe C, Schäfer E, Kretsch T. eid1: A new Arabidopsis mutant hypersensitive in phytochrome A-dependent high-irradiance responses. Plant Cell. 2000;12:547–558. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clack T, Mathews S, Sharrock RA. The phytochrome apoprotein family in Arabidopsis is encoded by five genes: the sequences and expression of PHYD and PHYE. Plant Mol Biol. 1994;25:413–427. doi: 10.1007/BF00043870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairchild CD, Schumaker MA, Quail PH. HFR1 encodes an atypical bHLH protein that acts in phytochrome A signal transduction. Genes Dev. 2000;14:2377–2391. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser C, Chory J. RSF1, an Arabidopsis locus implicated in phytochrome A signaling. Plant Physiol. 2000;124:39–45. doi: 10.1104/pp.124.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Mockler T, Duong H, Lin C. SUB1, an Arabidopsis Ca2+-binding protein involved in cryptochrome and phytochrome coaction. Science. 2001;291:487–490. doi: 10.1126/science.291.5503.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoecker U, Tepperman JM, Quail PH. SPA1, a WD-repeat protein specific to phytochrome A signal transduction. Science. 1999;284:496–499. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoecker U, Xu Y, Quail PH. SPA1: a new genetic locus involved in phytochrome A-specific transduction. Plant Cell. 1998;10:19–33. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.1.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huq E, Kang Y, Halliday KJ, Qin M, Quail PH. SRL1: a new locus specific to the phyB-signaling pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2000;23:461–470. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neff MM, Fankhauser C, Chory J. Light: an indicator of time and place. Genes Dev. 2000;14:257–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks BM, Cho MH, Spalding EP. Two genetically separable phases of growth inhibition induced by blue light in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 1998;118:609–615. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks BM, Quail PH. hy8, a new class of long hypocotyl mutants deficient in phytochrome A. Plant Cell. 1993;5:39–48. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.1.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks BM, Spalding EP. Sequential and coordinated action of phytochromes A and B during Arabidopsis stem growth revealed by kinetic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14142–14146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quail PH. The phytochrome family: dissection of functional roles and signalling pathways among family members. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1998;353:1399–1403. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharrock RA, Quail PH. Novel phytochrome sequences in Arabidopsis thaliana: structure, evolution, and differential expression of a plant regulatory photoreceptor family. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1745–1757. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.11.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. Sensing the light environment: the functions of the phytochrome family. In: Kendrick R, Kronenberg G, editors. Photomorphogenesis in Plants. Ed 2. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 377–416. [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. Physiological and ecological function within the phytochrome family. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1995;46:289–315. [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. Phytochromes and light signal perception by plants: an emerging synthesis. Nature. 2000;407:585–591. doi: 10.1038/35036500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soh M-S, Kim Y-M, Han S-J, Song P-S. REP1, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, is required for a branch pathway of phytochrome A signaling in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2000;12:2061–2073. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.11.2061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitelam GC, Patel S, Devlin PF. Phytochromes and photomorphogenesis in Arabidopsis. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B. 1998;353:1445–1453. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1998.0300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]