ABSTRACT

Pentalogy of Cantrell (PC) presents a distinctive challenge for clinicians and surgeons. In this case report, we have discussed the presentation, management, and literature review of a case of PC in a 17-month-old female child. The child was successfully managed with single-stage operation by a multidisciplinary team without any postoperative complications.

KEYWORDS: Case report, multidisciplinary team, pentalogy of Cantrell

INTRODUCTION

Pentalogy of Cantrell (PC) is a congenital rare thoracoabdominal wall closure defect, first described by Cantrell et al. in 1958.[1] It occurs in 5.5 per 1,000,000 live births, globally.[1] Approximately 185 cases have been reported around the world.

The PC consists of five congenital midline anomalies and presents a distinctive challenge for clinicians and surgeons. This syndrome is characterized by defects that involve the supraumbilical abdominal wall, the lower region of the sternum, ventral diaphragm, diaphragmatic pericardium, and different cardiac defects.[2]

Toyama[3] classified the anomalies into three clinical groups: Class I, definite diagnosis (all five defects present); Class II, probable diagnosis (four defects present, including ventral wall abnormalities and cardiac defects); and Class III, incomplete expression (various combinations of defects present including sternal abnormality). We present a case of Class I PC in a 17-month-old female child.

CASE REPORT

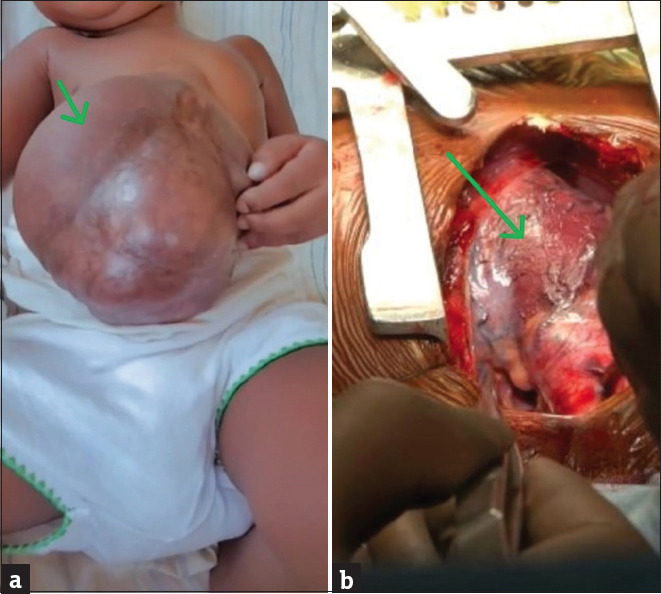

A 17-month-old female child referred from a peripheral hospital because of an abnormally positioned heart and abdominal wall defect. She was delivered term through cesarean section with birth weight of 3.8 kg to an unmarried primi mother with no antenatal checkups. There was no history of consanguinity or exposure to teratogenic substances. The parents are healthy, with no family history suggestive of birth defects. After delivery, the baby was noted to have congenital malformation of the anterior chest wall and abdomen. She was admitted at a local neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) and was diagnosed with congenital heart disease at 3 days of life. She was treated in the NICU conservatively for 2 weeks and discharged after establishing oral feeds with stable vitals. She is well-developed for her age but experiences intermittent episodes of shortness of breath and cyanotic spells. On initial examination at our hospital, there was an obvious lower chest wall defect with cardiac pulsation visible at the epigastrium. The manubrium was palpable, but the lower end of the sternum was not appreciated and there was a measuring 12 cm × 5 cm, extending proximally to the epigastrium [Figure 1a].

Figure 1.

(a) The clincal photograph showing large omphalocele (green arrow) and (b) intra operative photograph showing pericardial defect (green arrow)

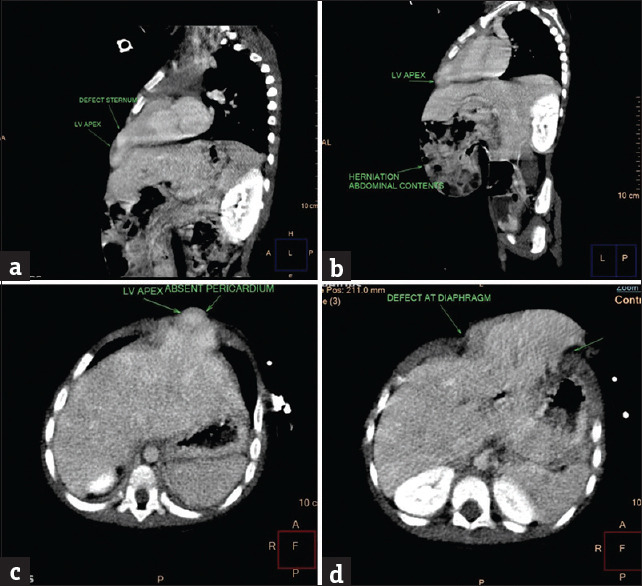

There were no other external congenital malformations detected. Her respiratory rate was 38 breaths/min and saturations were 68%–70% on room air. She had a heart rate of 132 beats/min with the apex beat palpable over the epigastrium and a systolic thrill felt at the epigastrium. The echocardiography showed multiple intracardiac defects: transposition of great arteries with large ventricular septal defect amounting to single ventricle, pulmonary atresia, left pulmonary artery (LPA) stenosis, restrictive patent ductus arteriosus (PDA). Computerized tomography (CT) scan findings showed the absence of the distal segment of the sternum [Figure 2a], the presence of anterior abdominal wall defect with protrusion of the bowel loops into the abdominal swelling [Figure 2b], left ventricular apex herniation with absent pericardium [Figure 2c], and the defect in the diaphragm [Figure 2d].

Figure 2.

(a) Defect in sternum, (b) herniation of abdominal contents, (c) absent pericardium, and (d) defect at diaphragm

The child was managed at our hospital by a multidisciplinary team: pediatric surgeon, pediatric cardiothoracic surgeon, pediatric cardiologist, cardiac anesthetist, and pediatric team. The incision was made through median sternotomy and thymus excised. Care was taken neither to injure the unprotected heart nor to break the peritoneum when separating adhesions between the subcutaneous tissues and the cardiac surface. The anterior pericardium was incised and marsupialized, both pulmonary arteries were mobilized up to their respective hila, and the superior vena cava was mobilized up to the innominate vein junction. intracardiac repair, including a bidirectional glenn shunt, pda ligation, and lpa plasty, was performed first using cardiopulmonary bypass, as shown in [Figure 1b]. Heart with marsupialized pericardium is completely repositioned back into the thoracic cavity with no hemodynamic changes and then the ends of the sternum were approximated with stainless steel wire after placing chest drains and pacing wires. Subsequently, the same midline chest wall incision was extended to the lower end of the abdominal defect. A small defect (4 cm × 2 cm) was noted in the anteromedial part of the left hemidiaphragm, and the defect was sutured directly using a 3-0 Prolene. Both domes of the diaphragm were apart and anterior plication was done. Thorough dissection was done layer by layer, the bowel contents were pushed back into the abdominal cavity, and the excess skin along with sac layer was excised. The lower sternal defect was left unrepaired, and the abdominal wall muscles were sutured in two layers using 2-0 prolene with interrupted sutures, following the placement of a drain in the dead space. Total duration of surgery was approximately 10 h and surgery was uneventful. The child was transferred intubated and ventilated postoperatively to the intensive care unit and continued on minimal ventilatory settings, which were weaned and was successfully extubated to low-flow oxygen on postoperative day (POD) 1.

The child was commenced on clear liquids on POD 2 and slowly increased as tolerated along with soft diet. Chest drain was removed on the 3rd POD and abdominal drain was removed on the 4th POD. The child was discharged after 12 days in hemodynamically stable condition with saturations >94% on room air.

DISCUSSION

PC is a rare condition occurring in 5.5 in 1 million live births.[1] Approximately 185 cases have been reported around the world. There is a male predominance with a male-to-female ratio of 2.7:1; however, our case involves a female.

Cantrell et al. suggested that the pattern of malformation in this syndrome might be a result of defective formation and differentiation of the ventral mesoderm at about 14–18 days of gestation.[1] Most cases are sporadic, and no recurrences have been reported.

PC is a congenital malformation characterized by (1) lower sternum defect, (2) anterior diaphragm defect, (3) parietal pericardium defect, (4) omphalocele, and (5) congenital heart anomalies. Ectopia cordis might or might not be associated with PC.[5] This pentalogy occurs with various degrees of severity, ranging from incomplete to severe expression with involvement of other organ systems.[4] This case is a full spectrum of the PC.

Diagnosis of PC is possible on antenatal sonography in the first trimester of pregnancy.[6] Postnatally, intracardiac anomalies are identified on the echocardiogram, and a ct scan can help assess the thoracic contour. however, diagnosing a pericardial defect based on imaging findings alone is challenging and is more reliably detected during surgery. CT pulmonary angiography also plays an important role in evaluating the abnormal heart and blood vessel structures. Therefore, combining ultrasound and CT angiography could improve preoperative planning.[7]

The management of patients with PC necessitates the coordination of a number of subspecialties who should be involved from the prenatal diagnosis until completion of the surgical repair, including neonatal resuscitation, temporary coverage of the defects, and palliative or corrective intracardiac repair along with thoracoabdominal reconstruction.

Early surgical intervention may be a risk factor for mortality, and stable neonatal patients may benefit from initial conservative management including prophylactic antibiotics and daily dressing changes to allow epithelialization of the omphalocele sac.[2] Critically ill neonates require full life support and timely surgical intervention and should be managed by a multidisciplinary team in the NICU.

The procedures and surgical approaches depend on the severity of cardiovascular malformation, the cardiopulmonary function, the presence and severity of ectopia cordis, the size of the abdominal wall defect, and the patient’s ability to tolerate the operation. The decision of operative repair should be made after a comprehensive evaluation and the best treatment strategy is well planned and uniquely individualized to achieve both structural integrity and hemodynamic stability. Both multistage and single-stage surgical repairs have been described and adopted in complete and incomplete syndromes of PC.[8] The basic principle in unstable patients is to focus on saving the child’s life and thus a multistage operation may be preferable. According to Saxena and van Tuil, staged repair may significantly reduce postoperative respiratory insufficiency, ventilator dependency, and even decrease mortality.[9] Although different opinions exist regarding which anomaly should be repaired first in PC, intracardiac anomalies are given priority and typically corrected first to prevent cardiac trauma and since the fragile heart function may be further affected by the thoracoabdominal reconstruction.[10] Subsequently, thoracoabdominal wall defects are repaired. On the other hand, a single-stage operation is possible and advisable in patients with noncomplex intracardiac anomalies and if the heart position can be successfully restored without hemodynamic changes.[11,12,13] In our case, we successfully did a single-stage operation without hemodynamic changes and any postoperative complications.

In our case, upper median sternotomy was done. Anterior pericardium was incised and marsupialized. Intracardiac repair, including a bidirectional glenn shunt, pda ligation, and lpa plasty, was performed using cardiopulmonary bypass. Heart with marsupialized pericardium is completely repositioned back into the thoracic cavity. Anterior part of both domes of diaphragm were plicated using 2-0 Prolene. Large omphalocele defect was excised and the abdomen was sutured using 2-0 Prolene in 2 layers with tension-free interrupted sutures. Mesh was not used during abdominal wall repair.

The prognosis depends primarily on the type and severity of associate malformations and intracardiac anomalies, but also on the location of the ectopic heart. Complete Cantrell syndrome and significant ectopia cordis are associated with a more dismal prognosis and carry a higher mortality as opposed to probable and incomplete syndromes without heart defects.[14] Very few patients with PC and significant ectopia cordis survive surgical repair, and the main causes of death include tachyarrhythmias, bradycardia, hypotension, rupture of the diverticulum, and heart failure.[15] However, the survival rate has improved to 61% with considerable advances in pediatric surgery and neonatal intensive care.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cantrell JR, Haller JA, Ravitch MM. A syndrome of congenital defects involving the abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1958;107:602–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vazquez-Jimenez JF, Muehler EG, Daebritz S, Keutel J, Nishigaki K, Huegel W, et al. Cantrell's syndrome: A challenge to the surgeon. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;65:1178–85. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00089-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toyama WM. Combined congenital defects of the anterior abdominal wall, sternum, diaphragm, pericardium, and heart: A case report and review of the syndrome. Pediatrics. 1972;50:778–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen CP. Syndromes and disorders associated with omphalocele (II): OEIS complex and Pentalogy of Cantrell. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46:103–10. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(07)60003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Laberge JM. Definition of Pentalogy of Cantrell. Commentary On Araujo Júnior et al. Diagnosis of Pentalogy of cantrell by three-dimensional ultrasound in third trimester of pregancy (fetal diagn ther 2006 21 544-547) Fetal Diagn Ther. 2008;23:168. doi: 10.1159/000111601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liang RI, Huang SE, Chang FM. Prenatal diagnosis of Ectopia Cordis at 10 weeks of gestation using two-dimensional and three-dimensional ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;10:137–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1997.10020137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Van Hoorn JH, Moonen RM, Huysentruyt CJ, van Heurn LW, Offermans JP, Mulder AL. Pentalogy of Cantrell: Two patients and a review to determine prognostic factors for optimal approach. Eur J Pediatr. 2008;167:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s00431-007-0578-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakasai Y, Thang BQ, Kanemoto S, Takahashi-Igari M, Togashi S, Kato H, et al. Staged repair of Pentalogy of Cantrell with Ectopia Cordis and ventricular septal defect. J Card Surg. 2012;27:390–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2012.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxena AK, van Tuil C. Delayed three-stage closure of giant omphalocele using pericard patch. Hernia. 2008;12:201–3. doi: 10.1007/s10029-007-0264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison MR, Filly RA, Stanger P, de Lorimier AA. Prenatal diagnosis and management of omphalocele and Ectopia Cordis. J Pediatr Surg. 1982;17:64–6. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(82)80329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang X, Xing Q, Sun J, Hou X, Kuang M, Zhang G. Surgical treatment and outcomes of pentalogy of Cantrell in eight patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1335–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maier HC, Bortone F. Complete failure of sternal fusion with herniation of pericardium;Report of a case corrected surgically in infancy. J Thorac Surg. 1949;18:851–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lampert JA, Harmaty M, Thompson EC, Sett S, Koch RM. Chest wall reconstruction in thoracoabdominal Ectopia Cordis: Using the pedicled osteomuscular latissimus dorsi composite flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;65:485–9. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181d376a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mallula KK, Sosnowski C, Awad S. Spectrum of Cantrell's pentalogy: Case series from a single tertiary care center and review of the literature. Pediatr Cardiol. 2013;34:1703–10. doi: 10.1007/s00246-013-0706-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz JH. Perioperative management of neonatal Ectopia Cordis: Report of three cases. Anesth Analg. 1992;75:833–7. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199211000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]