Abstract

Objective:

To examine trends in weight control practices from 1995 to 2005.

Method:

The Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System biennially assesses five weight control behaviors among nationally representative samples of United States high school students.

Results:

Across time, more females than males dieted (53.8% vs. 23.8%), used diet products (10% vs. 4.3%), purged (7.5% vs. 2.7%), exercised (66.5% vs. 46.9%), or vigorously exercised (42.8% vs. 36.8%). All weight control behaviors among males increased during the decade. Black females were less likely than Hispanic females, who were less likely than White females, to practice weight control. White males were less likely than Black males, who were less likely than Hispanic males, to practice weight control. The ethnic difference in weight control practices is consistent across time.

Conclusion:

All male adolescents are at increasing risk for developing eating disorder symptomatology, and Black females appear to continue to resist pressure to pursue thinness. © 2007 by Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Keywords: weight control, disordered eating, trends, ethnic differences, epidemiology, adolescents

Introduction

It has long been assumed that eating disorders in the United States are rare among ethnic minority populations.1 A prominent explanation for this assumption has been that ethnic minorities are less likely than White populations to be exposed to key risk factors such as the thin beauty ideal, social pressure to be thin, or dieting.1 Cross-cultural studies have shown, however, that globalization has brought the thin ideal and related social norms to many cultures and peoples and that, as a consequence, eating disorder symptoms ought to be expected to increase world wide.2 Smolak and Striegel-Moore hypothesized that the increasing “mainstreaming” of ethnic minorities into the popular culture, as reflected in the growing presence of ethnic minority fashion models, famous musicians, and television stars, will contribute to an increase in the prevalence of weight control behaviors among ethnic minority females.1

The gender difference in eating disorders and weight control behaviors is well established,2 but experts have hypothesized that eating pathology may be increasing among boys and men as well.3 There are indications of a proliferation of media images of unrealistic male bodies and of growing social pressure to achieve the muscular body ideal portrayed by the media. For example, using nationally representative cross-sectional samples from 1991 to 2001, Lowry et al.4 found that adolescent girls were consistently more likely than adolescent boys to be trying to lose weight, but the percentage of girls trying to lose weight did not change significantly throughout the 10 years, whereas the percentage of boys trying to lose weight increased significantly. However, Lowry et al. did not examine the prevalence of various unhealthy weight control behaviors, such as diet product use and purging.

Consistently, research has shown that eating disorders begin during adolescence, yet few epidemiological studies have been conducted among adolescent samples.5 However, studies have examined weight control practices among adolescents, as weight control behaviors have been suggested to trigger eating disorders and be indicative of an early stage of full-syndrome eating disorders.6,7 Daee et al.8 reviewed several studies published between 1991 and 2003 concerning the prevalence of weight control practices among adolescents. In examining their review, changes in prevalence over time are difficult to discern because the studies varied greatly in sample sizes, demographic composition of sample, recruitment procedures, and assessment methods. The present study examines whether weight control practices have become more common, particularly among ethnic minority groups, over the past decade.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the changes in the prevalence of weight control behaviors in nationally representative samples of high school students in the United States, particularly among ethnic minority groups, over the period from 1995 to 2005. We hypothesized that we would observe an increase in weight control behaviors among girls from ethnic minority populations, whereas the prevalence of these behaviors among White girls would remain relatively unchanged. We also hypothesized an increase in weight control behaviors among boys over the 10-year time period. Because of the lack of prior data on weight control behaviors in ethnic minority boys, we did not specify a hypothesis concerning the changes over time by ethnicity for boys. To achieve these aims, we capitalized on the availability of a large public access data base containing data collected as part of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System (YRBSS9).

Method

Participants

The YRBSS has been conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) biennially since 1991, and the present study utilized the data collected in 1995, 1997, 1999, 2001, 2003, and 2005. Each YRBSS used a three-stage cluster sample design to obtain a nationally representative sample of ninth to twelfth grade students in public and private high schools in the United States. In the first stage of sampling, counties were separated into primary sampling units (PSUs), with a county, a sub-area of a larger county, or several smaller adjacent counties forming one PSU. The PSUs were divided into sixteen strata based on the degree of urbanization and percentage of Black and Hispanic students. PSUs were selected from each strata with the probability of a PSU being selected proportional to the total number of students enrolled in that PSU. In the second stage of sampling, schools with at least one of the grades from nine through twelve were selected, once again with the probability of a school being selected proportional to the total number of students enrolled. Schools with higher percentages of Black and Hispanic students were over-sampled. In the third stage of sampling, one or two intact classes of either a required subject (e.g., English) or a required period (e.g., first period) were randomly selected from each grade in each school. No substitutes were found for schools that refused to participate. Further details about the YRBSS sampling method have been described previously.9 The number of students who completed questionnaires for the 1995 to 2005 YRBSS ranged from 10,904 to 16,262, and the overall response rate ranged from 60 to 69%. Sample characteristics ranged as follows: 45.2–51.3% female; 60.8–67.5% White; 12.5–14.6% Black; 9.8–16.6% Hispanic; 22.9–29.7% 9th grade; 23.9–26.1% 10th grade; 23.1–25.4% 11th grade; and 21.0–27.2% 12th grade.

Instrument and Procedure

An institutional review board at the CDC approved each YRBSS, and parental consent was obtained before survey administration. Participation was entirely voluntary, and responses were not associated with participant names. Surveys were administered by trained data collectors in classrooms, and students recorded responses on computer scannable answer sheets. Teachers left the classroom during survey administration, and students were seated as far apart as possible.

The YRBSS was designed to assess the prevalence of health-risk behaviors among youth. Variables of interest included demographic variables and weight control behavior variables (dieting, diet product use, purging, and exercise). Specific information is provided about each question because the wording or response choices of some questions changed across study years.

Demographic Variables.

In all six time points, demographic variables included sex and race/ethnicity (hereafter, “ethnicity”). The 1995 and 1997 surveys assessed ethnicity with the following mutually exclusive response choices: White—not Hispanic, Black—not Hispanic, Hispanic or Latino, Asian or Pacific Islander, American Indian or Alaskan Native, and Other. The 1999–2005 surveys allowed adolescents to choose more than one response category for ethnicity. The modified response choices were: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, and White. Adolescents were considered “White” if they only selected “White—not Hispanic” or “White” as their response; “Black” if they only selected “Black—not Hispanic” or “Black or African American” as their response; “Hispanic” if they selected “Hispanic or Latino” as one of their responses; and “Other” if they were not classified into one of the previous three categories. Adolescents categorized as “Other” were included in statistical analyses, but because this category is highly diverse, the results are not necessarily indicative of the prevalence rates of weight control behaviors among any particular ethnic minority group within the “Other” category and thus are not reported.

The 1999–2005 surveys also assessed height and weight with the questions “How tall are you without your shoes on?” and “How much do you weigh without your shoes on?” The 1995 and 1997 surveys did not assess height or weight. Height and weight were used to calculate body mass indices (BMI).

Weight Control Behaviors.

Dieting during the past 30 days was assessed in the 1995 and 1997 surveys with the question, “Did you diet to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?” The question was modified in the 1999–2005 surveys to “Did you eat less food, fewer calories, or foods low in fat to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?” Diet product use over the past 30 days was assessed in the 1995 and 1997 surveys with the question, “Did you take diet pills to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?” The question was modified in the 1999–2005 surveys to “Did you take any diet pills, powders, or liquids without a doctor’s advice to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?” Purging behavior over the past 30 days was assessed in each survey with the question, “Did you vomit or take laxatives to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?” Exercise in the past 30 days was assessed with the question, “Did you exercise to lose weight or to keep from gaining weight?” Response choices for all questions assessing weight control behaviors were “yes” and “no” across all study years.

Because the question assessing the 30-day prevalence of exercise did not inquire about the intensity of the exercise, we also examined trends in exercising vigorously for weight control purposes. The most recent guidelines for physical activity among adolescents, published in the Dietary Guidelines for America 2005, recommends adolescents to exercise vigorously at least 60 min daily.10 However, because previously, Healthy People 2010 recommended adolescents to exercise vigorously at least 20 min for 3 days per week,11 the 1995–2003 surveys assessed vigorous exercise according to this previous guideline. Specifically, the 1995, 1997, and 2001–2005 surveys assessed vigorous exercise with the question: “On how many of the past 7 days did you exercise or participate in sports activities for at least 20 min that made you sweat and breathe hard, such as basketball, jogging, fast dancing, swimming laps, tennis, fast bicycling, or similar aerobic activities?” The 1999 survey assessed vigorous exercise with a shortened version of the original question: “On how many of the past 7 days did you exercise or participate in sports activities for at least 20 min that made your sweat and breathe hard?” The response choices ranged from “0 days” to “7 days.” The present study considered adolescents as exercising vigorously for weight control if they responded to the question assessing exercise for weight control with “yes” and responded to the question assessing the frequency of vigorous exercise with “3 days” or above.

Statistical Analyses

Because of the well-established findings of gender differences both in prevalence of and risk factors for weight control behaviors,2 logistic regressions and post-hoc χ2 analyses were conducted separately for female and male adolescents. To allow the potential for linear and nonlinear change, time was treated as a continuous variable with linear, quadratic, and cubic aspects. The linear time variable was assigned coefficients that reflect the biennial administration of the survey: −5, −3, −1, 1, 3, 5. Coefficients for the quadratic time variable were the squares of the coefficients for the linear time variable, and coefficients for the cubic time variable were the cubes of the coefficients for the linear time variable. All predictors were center-coded.12 Sample weights were used in each individual analysis to correct for differences in the probability of selection and to adjust for nonresponse. Adjustments for the design effects were incorporated into the estimation process implemented by SAS (Version 9.1) survey procedures to generate accurate standard errors.13

The linear, quadratic, and cubic time variables, an ethnicity variable (White, Black, Hispanic, and Other), and a time-by-ethnicity interaction variable were entered into separate logistic regressions for female and male adolescents to test: (1) linear, quadratic, and cubic time trends in each behavior; (2) ethnic differences for each behavior; and (3), time-by-ethnicity interactions for each behavior. The linear, quadratic, and cubic time variables were also entered into separate logistic regressions for each gender- and ethnicity-specific subgroup to test time trends in each behavior among each subgroup. Post-hoc χ2 analyses were conducted for significant time trends and interactions. Trend βs were considered statistically significant if the two-tailed p-value was less than or equal to 0.05. Odds ratios (ORs) were considered statistically significant if the 95% confidence interval did not include 1.

Results

Female Adolescents

The prevalence rates of weight control behaviors among female adolescents, ORs with 95% confidence intervals of practicing weight control behaviors for each ethnic group, and regression coefficients for trends in weight control practices are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Weight control practices among U.S. female adolescents 1995–2005: Prevalence, odds ratios, and regression coefficients for trends

| Prevalence |

OR | 95% CI | Trend β |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | Average | Linear | Quadratic | Cubic | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Dieting (30 days) | 47.8 | 45.7 | 56.2 | 58.6 | 56.2 | 54.8 | 53.8 | 0.085*** | −0.009*** | −0.002** | ||

| White | 52.5 | 47.9 | 60.3 | 63.1 | 61.1 | 58.8 | 57.5 | Referent | 0.113*** | −0.009*** | −0.003*** | |

| Black | 31.9 | 33.9 | 43.4 | 40.2 | 39.0 | 39.6 | 38.2 | 0.5 | 0.4–0.6 | 0.014 | −0.010** | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 48.2 | 46.3 | 51.0 | 56.5 | 54.9 | 53.2 | 52.2 | 0.9 | 0.7–1.0 | 0.079** | −0.004 | −0.002 |

| Diet product use (30 days) | 8.7 | 8.0 | 10.9 | 12.6 | 11.3 | 8.1 | 10.0 | 0.098*** | −0.015*** | −0.004*** | ||

| White | 10.2 | 8.5 | 11.8 | 13.6 | 13.0 | 9.2 | 11.1 | Referent | 0.117*** | −0.012** | −0.005*** | |

| Black | 4.0 | 5.0 | 6.9 | 7.5 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 5.6 | 0.5 | 0.4–0.8 | 0.001 | −0.020* | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 8.6 | 9.6 | 11.0 | 13.5 | 11.7 | 7.5 | 10.4 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 | 0.078 | −0.019** | −0.004 |

| Purging (30 days) | 7.6 | 7.5 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 8.4 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 0.040 | −0.006 | −0.002* | ||

| White | 8.2 | 7.5 | 7.0 | 8.2 | 8.5 | 6.7 | 7.7 | Referent | 0.057 | −0.002 | −0.003* | |

| Black | 4.1 | 6.3 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 5.6 | 4.0 | 5.3 | 0.8 | 0.5–1.1 | −0.075 | −0.015 | 0.003 |

| Hispanic | 10.9 | 10.4 | 6.4 | 10.8 | 9.7 | 6.8 | 9.0 | 1.3 | 1.0–1.7 | 0.068 | −0.001 | −0.005* |

| Exercise (30 days) | 63.8 | 65.4 | 67.5 | 68.4 | 65.7 | 67.4 | 66.5 | −0.001 | −0.004* | 0.001 | ||

| White | 69.6 | 69.7 | 70.0 | 72.5 | 69.6 | 69.8 | 70.2 | Referent | 0.012 | −0.003 | −0.000 | |

| Black | 49.1 | 49.2 | 58.6 | 53.4 | 49.2 | 56.5 | 52.8 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.5 | −0.038 | −0.004 | 0.003* |

| Hispanic | 61.3 | 64.5 | 65.1 | 66.2 | 64.1 | 68.9 | 65.2 | 0.7 | 0.6–0.8 | −0.019 | −0.000 | 0.002 |

| Vigorous exercise (7 days) | 40.3 | 41.2 | 44.0 | 44.9 | 42.4 | 43.3 | 42.8 | 0.008 | −0.004* | 0.000 | ||

| White | 45.9 | 46.1 | 47.0 | 49.2 | 46.2 | 46.2 | 46.8 | Referent | 0.010 | −0.003 | −0.000 | |

| Black | 25.0 | 25.7 | 33.4 | 31.5 | 28.7 | 30.9 | 29.3 | 0.4 | 0.3–0.5 | 0.005 | −0.008* | 0.001 |

| Hispanic | 35.5 | 38.8 | 38.8 | 39.7 | 39.3 | 45.9 | 40.0 | 0.7 | 0.6–0.7 | −0.014 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

Dieting.

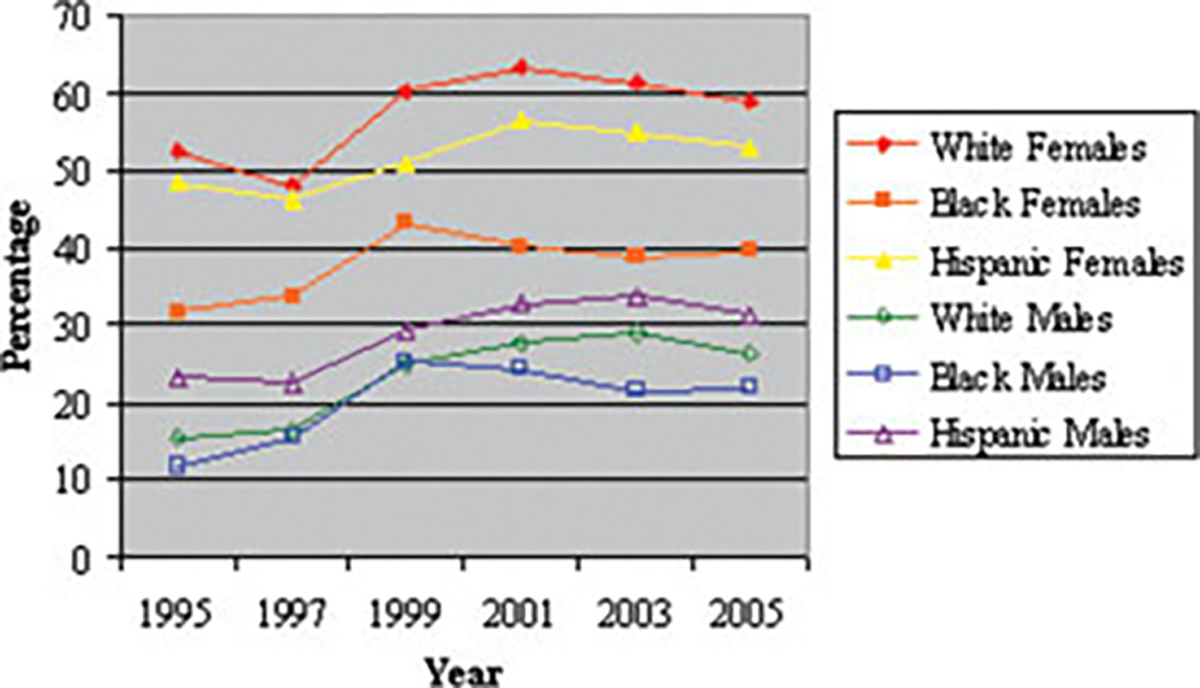

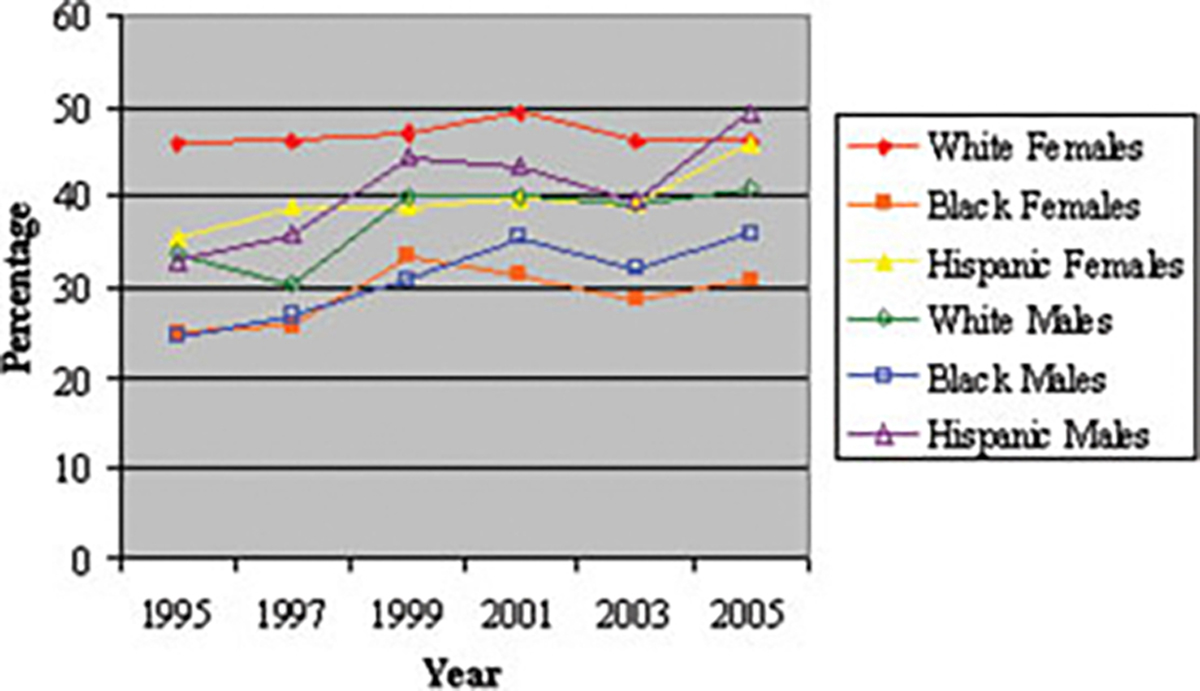

Figure 1 illustrates the prevalence rates of dieting by gender and ethnicity. The linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time on the 30-day prevalence of dieting among female adolescents were significant. Specifically, the prevalence of dieting among females significantly decreased early in the 10-year period (between 1995 and 1997), significantly increased in the middle of the 10-year period (between 1997 and 2001), and significantly decreased again in the most recent years of the survey (between 2001 and 2005). The significant positive linear trend further demonstrated an overall increase in rates of dieting across time despite these significant upward and downward changes in prevalence. Excluding the 2 years (1995 and 1997) that used a different question to assess dieting behavior, only the quadratic effect of time was significant (β = −0.039, p < .05). When examining dieting behavior by ethnicity, significantly fewer Black females than White or Hispanic females dieted for weight control. Further, the time-by-ethnicity interaction for dieting was not statistically significant, suggesting that these ethnic differences were consistent across time.

FIGURE 1. Prevalence of dieting among adolescents by gender and ethnicity. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.].

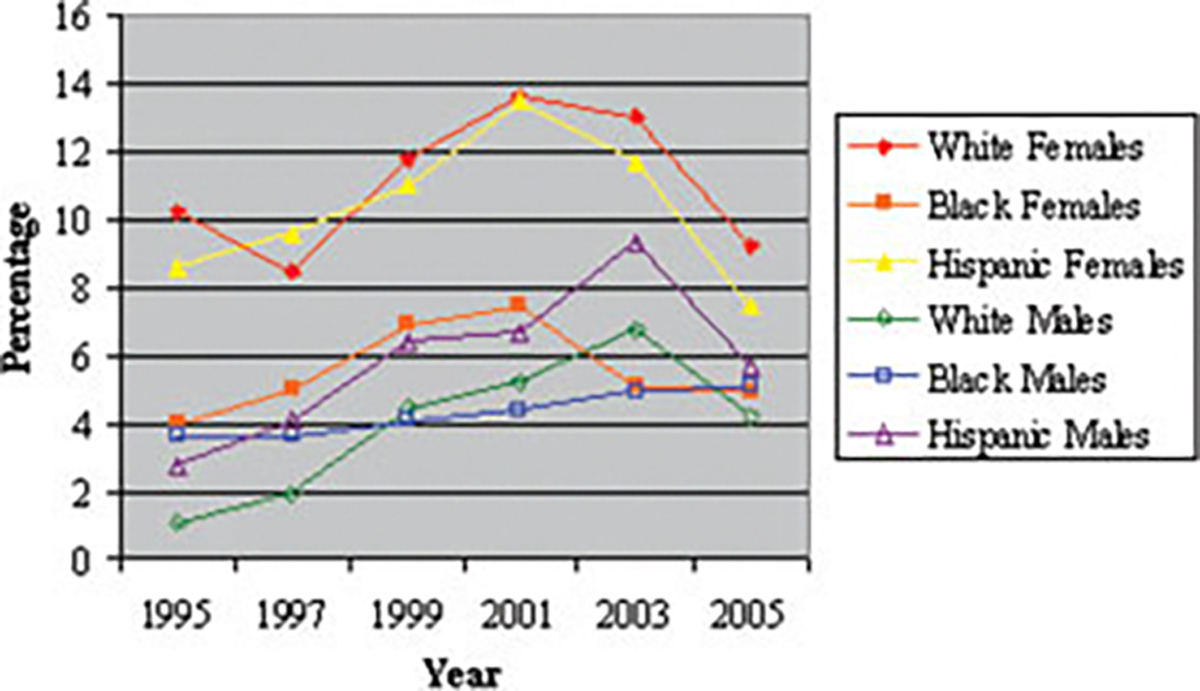

Diet Product Use.

Figure 2 illustrates the prevalence rates of diet product use by gender and ethnicity. The linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time on the 30-day prevalence of diet product use among female adolescents were significant. The prevalence of diet product use among females was similar early in the 10-year period (between 1995 and 1997), significantly increased in the middle of the 10-year period (between 1997 and 2001), and significantly decreased in the most recent years of the survey (between 2001 and 2005). The significant positive linear trend further demonstrated an overall increase in diet product use across time, despite these significant upward and downward changes in prevalence. Excluding the 2 years (1995 and 1997) that used a different question to assess dieting behavior, only the linear effect of time was significant (β = 0.083, p < .05). Again, significantly fewer Black females compared to their White or Hispanic counterparts used diet products for weight control. The time-by-ethnicity interaction for using diet products was not statistically significant, suggesting that these differences remained consistent across time.

FIGURE 2. Prevalence of diet product use among adolescents by gender and ethnicity. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.].

Purging.

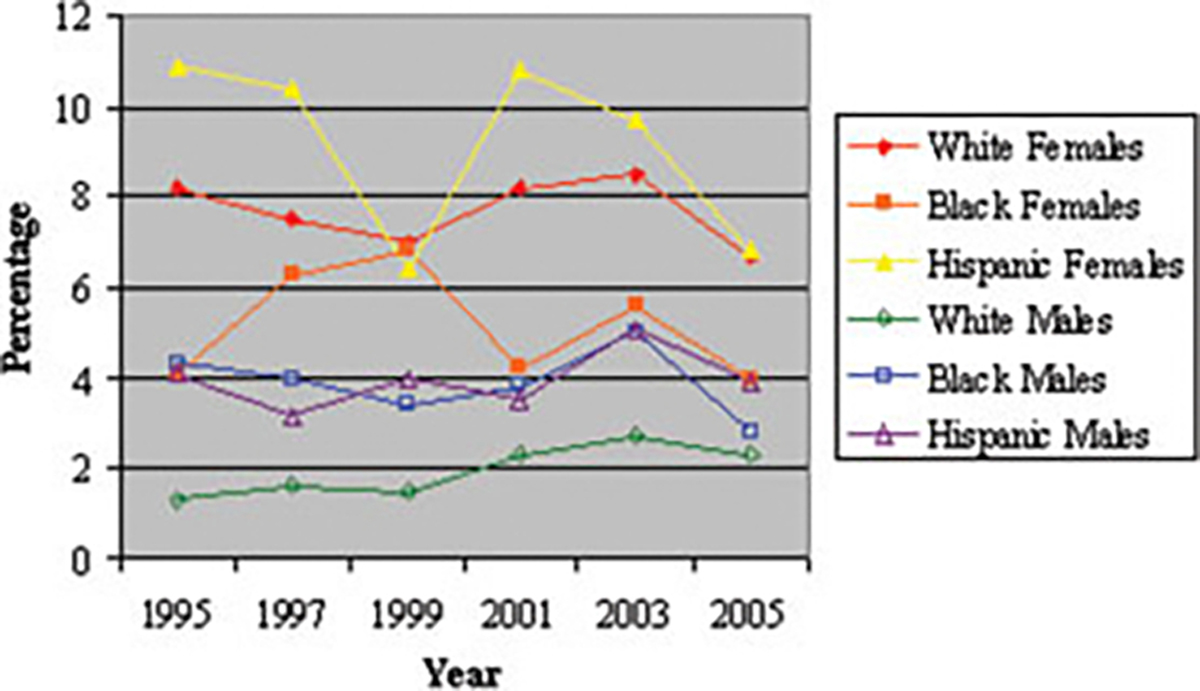

Figure 3 illustrates the prevalence of purging by gender and ethnicity. Only the cubic effect of time on the 30-day prevalence of purging among female adolescents was significant. Specifically, the prevalence of purging among females was stable during most of the decade (1995–2003) and significantly decreased in more recent years of the survey (2003–2005). Similar to findings for dieting and diet product use, significantly fewer Black females than Hispanic females purged for weight control. In contrast to the results for dieting and diet product use, the prevalence of purging among White females did not differ significantly from the prevalence of purging among Black or Hispanic females. The time-by-ethnicity interaction for purging was not statistically significant, suggesting that these differences were consistent across time.

FIGURE 3. Prevalence of purging among adolescents by gender and ethnicity. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.].

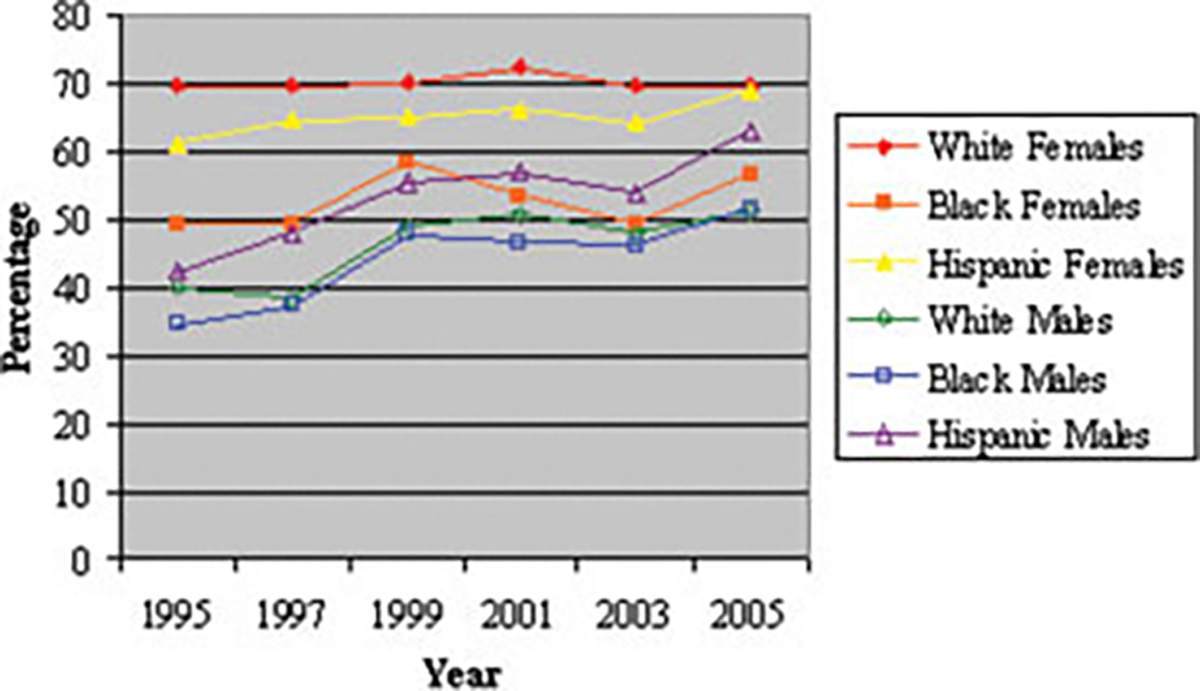

Exercise.

Figure 4 illustrates the prevalence of exercise by gender and ethnicity. The quadratic effect of time on 30-day prevalence of exercise among female adolescents was significant, showing substantial fluctuation across the 10 years. Specifically, the prevalence of exercise was stable between 1995 and 1997, increased significantly between 1997 and 1999, stabilized again between 1999 and 2001, decreased significantly between 2001 and 2003, and increased significantly again between 2003 and 2005. Again, significantly fewer Black females than White or Hispanic females exercised for weight control. Additionally, significantly fewer Hispanic females than White females exercised for weight control. The time-by-ethnicity interaction for exercise was not statistically significant, suggesting that these differences remained consistent across time.

FIGURE 4. Prevalence of exercise among adolescents by gender and ethnicity. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.].

Vigorous Exercise

Figure 5 illustrates the prevalence of vigorous exercise by gender and ethnicity. The quadratic effect of time on the 7-day prevalence of vigorous exercise among female adolescents was significant. Changes in the prevalence of vigorous exercise mirrored changes found in exercise, with the exception that the prevalence of vigorous exercise was stable between 2003 and 2005. Significantly fewer Black females than White or Hispanic females vigorously exercised for weight control, and significantly fewer Hispanic females than White females reported vigorous exercise. A significant time-by-ethnicity interaction (p < .01) showed that these ethnic differences were generally consistent across time except in the most recent year of the survey. In 2005, although the prevalence of vigorous exercise among Black females was still significantly lower than the prevalence among White or Hispanic females, the prevalence of vigorous exercise among White females was no longer significantly different from the prevalence among Hispanic females.

FIGURE 5. Prevalence of vigorous exercise among adolescents by gender and ethnicity. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.].

Body Mass Indices.

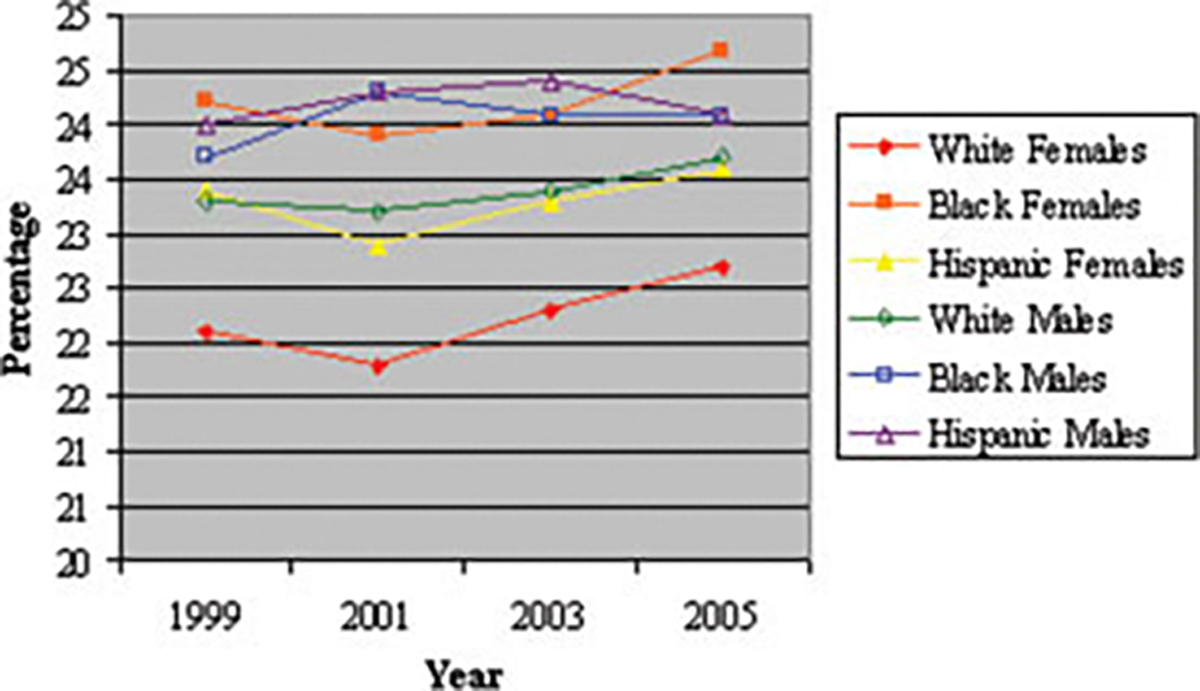

Table 2 shows the mean BMI among adolescents and regression coefficients for trends in BMI. The linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time on the BMI among female adolescents were significant. Specifically, the mean BMI significantly decreased from 1999 to 2001 and significantly increased from 2001 to 2005. The significant positive linear trend demonstrated an overall increase in mean BMI across time despite these significant upward and downward changes in prevalence. The mean BMI among White females was significantly lower than that among Black or Hispanic females (F(3) = 14.23, p < .0001). Figure 6 illustrates the mean BMI by gender and ethnicity.

TABLE 2.

Mean BMI among U.S. adolescents 1995–2005 and regression coefficients for trends

| Mean BMI (SD) |

Trend β |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | 1999–2005 | Linear | Quadratic | Cubic | |

|

| ||||||||

| Females | 22.6 (4.5) | 22.2 (4.3) | 22.7 (4.2) | 23.1 (4.6) | 22.6 (4.4) | −0.151** | 0.164*** | −0.020** |

| White | 22.1 (5.4) | 21.8 (4.7) | 22.3 (4.7) | 22.7 (5.2) | 22.2 (5.0) | −0.136 | 0.148** | −0.018* |

| Black | 24.2 (3.5) | 23.9 (4.5) | 24.1 (3.7) | 24.7 (4.1) | 24.2 (3.9) | −0.114 | 0.063 | −0.002 |

| Hispanic | 23.4 (2.9) | 22.9 (3.0) | 23.3 (3.6) | 23.6 (3.7) | 23.3 (3.3) | −0.249* | 0.197* | −0.024 |

| Males | 23.4 (4.9) | 23.5 (4.7) | 23.7 (4.9) | 23.7 (5.0) | 23.6 (4.9) | 0.036 | 0.023 | −0.004 |

| White | 23.3 (6.7) | 23.2 (5.3) | 23.4 (5.6) | 23.7 (5.6) | 23.4 (5.8) | −0.026 | 0.034 | −0.002 |

| Black | 23.7 (3.6) | 24.3 (4.3) | 24.1 (3.9) | 24.1 (4.1) | 24.0 (3.9) | 0.281 | −0.153 | 0.019 |

| Hispanic | 24.0 (3.0) | 24.3 (3.9) | 24.4 (4.1) | 24.1 (4.2) | 24.2 (3.8) | 0.152 | −0.021 | −0.003 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

FIGURE 6. Mean BMI among adolescents by gender and ethnicity. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.interscience.wiley.com.].

Male Adolescents

The prevalence rates of weight control behaviors among male adolescents, ORs with 95% confidence intervals of practicing weight control behaviors for each ethnic group, and regression coefficients for trends in weight control practices are shown in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Weight control practices among U.S. male adolescents 1995–2005: Prevalence, odds ratios, and regression coefficients for trends

| Prevalence |

OR | 95% CI | Trend β |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 1997 | 1999 | 2001 | 2003 | 2005 | Average | Linear | Quadratic | Cubic | |||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Dieting (30 days) | 16.0 | 17.6 | 25.0 | 28.2 | 28.9 | 26.8 | 23.8 | 0.118*** | −0.013*** | −0.002** | ||

| White | 15.7 | 16.6 | 25.1 | 27.6 | 29.1 | 26.4 | 23.3 | Referent | 0.130*** | −0.013*** | −0.002** | |

| Black | 11.7 | 15.6 | 25.3 | 24.5 | 21.8 | 22.0 | 20.5 | 1.0 | 0.8–1.3 | 0.033 | − 0.023*** | 0.002 |

| Hispanic | 23.5 | 22.6 | 29.4 | 32.7 | 33.7 | 31.5 | 29.5 | 1.5 | 1.3–1.8 | 0.107** | − 0.007 | −0.003 |

| Diet product use (30 days) | 1.9 | 2.4 | 4.4 | 5.5 | 7.1 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 0.219*** | − 0.023*** | −0.005** | ||

| White | 1.1 | 1.9 | 4.5 | 5.2 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 4.0 | Referent | 0.225*** | − 0.035*** | −0.003 | |

| Black | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 5.1 | 4.3 | 2.1 | 1.3–3.6 | 0.056 | 0.001 | −0.001 |

| Hispanic | 2.8 | 4.1 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 9.3 | 5.7 | 6.2 | 2.4 | 1.6–3.6 | 0.174** | − 0.022* | −0.004 |

| Purging (30 days) | 2.2 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 0.155*** | − 0.002 | −0.005** | ||

| White | 1.3 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 2.3 | 1.9 | Referent | 0.144* | − 0.005 | −0.004 | |

| Black | 4.3 | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.8 | 5.0 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 2.2–6.9 | 0.087 | − 0.003 | −0.005 |

| Hispanic | 4.1 | 3.2 | 4.0 | 3.5 | 5.1 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 3.2 | 2.1–5.0 | 0.102 | 0.002 | −0.004 |

| Exercise (30 days) | 39.3 | 39.9 | 49.5 | 51.0 | 49.0 | 52.9 | 46.9 | 0.059*** | − 0.006** | −0.000 | ||

| White | 39.9 | 38.6 | 48.7 | 50.9 | 48.1 | 51.2 | 46.0 | Referent | 0.072*** | − 0.006** | −0.001 | |

| Black | 34.6 | 37.5 | 47.6 | 46.6 | 46.1 | 51.6 | 44.5 | 0.8 | 0.7–1.0 | 0.033 | − 0.006 | 0.002 |

| Hispanic | 42.5 | 47.9 | 55.5 | 56.8 | 53.7 | 63.0 | 54.1 | 1.2 | 1.1–1.4 | 0.007 | − 0.004 | 0.003* |

| Vigorous exercise (7 days) | 32.4 | 31.0 | 39.0 | 39.5 | 38.5 | 41.2 | 36.8 | 0.053*** | − 0.004* | −0.001 | ||

| White | 33.7 | 30.4 | 40.0 | 40.0 | 39.3 | 40.9 | 37.2 | Referent | 0.070*** | − 0.004 | −0.001 | |

| Black | 24.6 | 26.9 | 30.9 | 35.6 | 32.0 | 36.2 | 31.2 | 0.7 | 0.6–0.8 | 0.044 | − 0.005 | 0.000 |

| Hispanic | 32.8 | 35.7 | 44.4 | 43.4 | 39.5 | 49.2 | 41.3 | 1.1 | 0.9–1.3 | −0.013 | − 0.003 | 0.003** |

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .0001.

Dieting.

The linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time on the 30-day prevalence of dieting among male adolescents were significant. Specifically, the prevalence of dieting significantly increased during the first half of the decade (between 1995 and 2001), was stable between 2001 and 2003, and decreased significantly between 2003 and 2005. The significant positive linear trend further indicated an overall increase in dieting across time, despite these significant upward and downward changes in prevalence. Excluding the 2 years (1995 and 1997) that used a different question to assess dieting behavior, only the linear effect of time was significant (β = 0.082, p < .01). When examining dieting behavior by ethnicity, significantly more Hispanic males than White or Black males dieted for weight control. The time-by-ethnicity interaction for dieting was not statistically significant, suggesting that these ethnic differences were consistent across time.

Diet Product Use.

The linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time on the 30-day prevalence of diet product use among male adolescents were significant. The prevalence of diet product use among male adolescents increased significantly throughout most of the decade (between 1995 and 2003) and decreased significantly in the most recent years of the survey (between 2003 and 2005). Despite the significant decrease in prevalence between 2003 and 2005, the significant positive linear trend further demonstrated an overall increase in diet product use across time. Excluding the 2 years (1995 and 1997) that used a different question to assess diet product use, only the linear (β = 0.135, p < .05) and cubic (β = −0.016, p < .05) effects of time were significant. Similar to the findings for dieting, significantly fewer White males than Hispanic males used diet products for weight control, but in contrast to the results for dieting, the prevalence of diet product use among Black males did not differ significantly from the prevalence among Hispanic males. A significant time-by-ethnicity interaction was found for diet product use among male adolescents (p < .01). While the prevalence of diet product use increased significantly among White and Hispanic boys, the prevalence of diet product use among Black boys was stable.

Purging.

The linear and cubic effects of time on the 30-day prevalence of purging among male adolescents were significant. Specifically, the prevalence of purging among male adolescents did not change significantly in the beginning of the 10-year period (between 1995 and 1999), increased significantly in the middle of the 10-year period (between 1999 and 2003), and decreased significantly in the most recent years of the survey (between 2003 and 2005). The significant positive linear trend further demonstrated an overall increase in purging across time. Similar to the findings for diet product use, significantly fewer White male adolescents than Black or Hispanic male adolescents purged for weight control. A significant time-by-ethnicity interaction for purging (p < .01) showed that these ethnic differences were generally consistent across time except in 2001 and 2005. In 2001, the prevalence of purging among White male adolescents was not significantly different from the prevalence among Hispanic male adolescents, although it was still significantly less than the prevalence among Black male adolescents; and, in 2005, the prevalence of purging among White male adolescents was not significantly different from the prevalence among Black male adolescents, although it was still significantly less than the prevalence among Hispanic male adolescents.

Exercise.

The linear and quadratic effects of time on the 30-day prevalence of exercise among male adolescents were significant. Similar to the trend among females, the prevalence of exercise among males fluctuated substantially across the 10 years. Specifically, the prevalence of exercise among male adolescents was stable between 1995 and 1997, increased significantly between 1997 and 1999, stabilized again between 1999 and 2001, decreased significantly between 2001 and 2003, and increased significantly again between 2003 and 2005. However, in contrast to the trend among females, the significant positive linear trend indicated an overall increase in exercise across time despite the significant fluctuation in prevalence. Similar to the findings for dieting regarding ethnic differences in prevalence rates, statistically significantly more Hispanic males than White or Black males exercised for weight control, but the small OR of 1.2 indicates that the magnitude of the difference in prevalence rates is small. The time-by-ethnicity interaction for exercise was not statistically significant, suggesting that these ethnic differences were consistent across time.

Vigorous Exercise.

The linear and quadratic effects of time on the 7-day prevalence of vigorous exercise among male adolescents were significant. Changes in the prevalence of vigorous exercise mirrored changes found in exercise, with the exception that the prevalence of vigorous exercise was stable between 1999 and 2003. Findings regarding ethnic differences in prevalence rates differed from findings for exercise: significantly fewer Black males vigorously exercised than White or Hispanic males. The time-by-ethnicity interaction for vigorous exercise was not significant, suggesting that these ethnic differences remained consistent across time.

Body Mass Indices.

The linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of time on the BMI among male adolescents were not significant, suggesting that the mean BMI was consistent across time. The mean BMI among White males was significantly lower than that among Black or Hispanic males (F(3) = 7.31, p < .0001).

Conclusion

The prevalence of dieting and diet product use among female adolescents and the prevalence of all weight control behaviors among male adolescents showed significant linear increases between 1995 and 2005. Excluding the 2 years that used a different question to assess dieting behavior, the linear effect of time on dieting among female adolescents was no longer significant, suggesting that the linear increase previously found for dieting among females was mainly a result of a change in the assessment question for dieting. The prevalence of all weight control behaviors among female and male adolescents also showed significant nonlinear changes in the 10-year period, although the specific changes differed greatly by gender and by behavior. Generally, the data suggest that among girls, Black female adolescents are the least likely to practice weight control, and White female adolescents are the most likely to practice weight control. In contrast, among males, White male adolescents are the least likely to practice weight control, and Hispanic male adolescents are the most likely to practice weight control. Lastly, the ethnic differences in weight control practices has not been decreasing across time.

The mean BMI among female adolescents has been increasing, and the lack of a corresponding linear change in dieting, exercise, and vigorous exercise among female adolescents indicates that female adolescents may not be properly dealing with their increasing weight. On the other hand, diet product use and purging are unhealthy behaviors that lead to severe medical complications,14,15 and the prevalence of these behaviors and the significant linear increase in diet product use among females are concerning. However, it is encouraging that the prevalence of diet product use and purging among female adolescents have decreased greatly in recent years, possibly because of the FDA ban on ephedra.16

Among male adolescents, the prevalence rates of all weight control behaviors have been rising. This result is consistent with reports of a growing percentage of males being admitted to an inpatient eating disorder treatment from 1984 to 199717 and findings of increasing muscularity of action figures18 and male magazine models.19,20 These results support that the social pressure for men to achieve unrealistic body ideals is growing and suggest that male adolescents are at increased risk of experiencing body dissatisfaction and developing eating disorder symptomatology. Considering that males have negative attitudes toward treatment-seeking and are less likely than females to seek treatment,21 efforts should be made to increase awareness of eating disorder symptomatology in male adolescents, and future prevention efforts should target male as well as female adolescents.

Interestingly, the prevalence rates of weight control behaviors, even those that show significant linear changes, fluctuated considerably throughout the 10-year period. We hypothesize that the prevalence of weight control practices may be inherently variable and/or sensitive to slight changes in certain aspects of culture, such as fashion and topics of media focus. Also, the time of administration of the YRBSS is not specified, and the fluctuation in the prevalence rates may reflect seasonal variation in the prevalence of weight control practices, as eating attitudes and behaviors change throughout the year.22,23

In terms of ethnic differences, similar to previous studies,24,25 we found that among female adolescents, Black females are the least likely and White females are the most likely to practice weight control. This result is consistent with findings that Black females have flexible concepts of beauty and emphasize “making what you’ve got work for you,” and thus are more satisfied and comfortable with their bodies.26,27

On the other hand, results for male adolescents showed almost the opposite pattern of ethnic differences, with White male adolescents being the least likely and Hispanic male adolescents being the most likely to practice weight control. Because of the lack of research on weight control practices and body image among ethnic minority males, we are not clear about why more ethnic minority males than White males reported weight control behaviors. We speculate that this may be a result of the higher prevalence of overweight among Hispanic male adolescents.28 Another possible reason might be the strong emphasis on athletic performance among Black males.29 Future studies need to investigate this and other possible explanations for Black and Hispanic male adolescents’ increased likelihood of practicing weight control behaviors.

The finding that ethnic differences in weight control behaviors are not decreasing not only is surprising considering the apparent growing media and cultural pressure for individuals of all ethnicities to adhere to a single thin beauty ideal, but also conflicts with recent research.30–32 Perhaps the emphasis on “making what you’ve got work for you” among Black females prevents them from being influenced by media messages. However, from another perspective, considering the toxic food environment that encourages high consumption of nutritionally deficient foods,33 consistently embracing one’s body type may carry its own risk. Black females’ and White males’ decreased tendency to practice weight control in general may put them at risk for becoming overweight. Indeed, Heinburg et al.34 proposed that some body image concern may be helpful because it may lead individuals to engage in healthy weight control practices.

The present study had several limitations. First, studies have found that patients with eating disorders tend to avoid participation in research,35 and the YRBSS’ low response rates, ranging from 60 to 69%, could indicate that the observed prevalence rates of weight control behaviors may be lower than the actual prevalence rate. Second, the percentage of ethnic minority students in a school may affect several aspects of acculturation, which has been linked to eating pathology.25,36 Thus, the over-sampling of schools with higher percentages of Black and Hispanic students may have also biased the results. Other limitations of the present study include the cross-sectional, instead of longitudinal, design; possible errors in self-report; the inconsistent phrasing of the assessment questions; and, the lack of assessment of related variables in all or some years, including BMI, binge eating, acculturation, and socioeconomic status.

Furthermore, future YRBSS assessments should include a more specific assessment of ethnicity and questions about the frequency and intensity of weight control behaviors. Many ethnicities, e.g. Cuban, Mexican, and Puerto Rican, are generally considered “Black” or “Hispanic,” but each of these ethnicities have distinct cultures that may differentially affect risk for developing weight concern.37 Also, an adequate amount of dietary restriction and exercise are necessary to maintain a healthy lifestyle, but extreme dieting and excessive exercising lead to serious health problems and can trigger eating disorders.6,38 Assessing the frequency and intensity of weight control behaviors will help us better understand the percentage of adolescents engaging in healthy or unhealthy weight control.

However, the limitations notwithstanding, this study is one of the first studies to utilize 10 years of data from large, nationally representative samples of adolescents to examine trends and ethnic differences in weight control behaviors. Males, especially ethnic minority males, are under studied in this field, and this study provides key information about the prevalence of weight control practices in a large, diverse sample of male adolescents and raises important questions about the factors contributing to the ethnic difference in weight control practices among male adolescents.

Footnotes

Presented as posters at the Eating Disorder Research Society 2006 Annual Meeting and the Academy of Eating Disorders 2007 International Conference on Eating Disorders.

References

- 1.Smolak L, Striegel-Moore R. Challenging the myth of the golden girl: Ethnicity and eating disorders. In: Striegel-Moore R, Smolak L, editors. Eating Disorders: Innovative Directions for Research and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001, pp. 111–132. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Striegel-Moore RH, Bulik CM. Risk factors for eating disorders. Am Psychol 2007;62:181–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey JA, Robinson JD. Eating disorders in men: Current considerations. J Clin Psychol Med Set 2003;10:297–306. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowry R, Galuska DA, Fulton JE, Burgeson CR, Kann L. Weight management goals and use of exercise for weight control among U.S. high school students, 1991–2001. J Adolesc Health 2005;36:320–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans DL, Foa EB, Gur RE, Hendin H, O’Brien CP, Seligman MEP, et al. Treating and Preventing Adolescent Mental Health Disorders: What We Know and What We Don’t Know: A Research Agenda for Improving the Mental Health of Our Youth. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davis C, Kennedy SH, Ravelski E, Dionne M. The role of physical activity in the development and maintenance of eating disorders. Psychol Med 1994;24:957–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walters EE, Kendler KS. Anorexia nervosa and anorexic-like syndromes in a population-based female twin sample. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:64–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daee A, Robinson P, Lawson M, Turpin JA, Gregory B, Tobias JD. Psychologic and physiologic effects of dieting in adolescents. South Med J 2002;95:1032–1041. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kolbe LJ, Kann L, Collins JL. Overview of the youth risk behavior surveillance system. Public Health Rep 1993;108(Suppl 1):2–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United States Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2005, 6th ed. Available from: http://purl.access.gpo.gov/GPO/LPS57108, last accessed 3 June 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2010. McLean, VA: International Medical Publishing, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraemer HC, Blasey CM. Centering in regression analyses: A strategy to prevent errors in statistical inference. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2004;13:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.SAS Institute. SAS 9.1 for Windows. Release 9.1. ed. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick L Eating disorders: A review of the literature with emphasis on medical complications and clinical nutrition. Altern Med Rev 2002;7:184–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rome ES, Ammerman S. Medical complications of eating disorders: An update. J Adolesc Health 2003;33:418–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FDA begins ban on dietary drugs using ephedra. Wall Street Journal, April 13, 2004, Sect. D.5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun DL, Sunday SR, Huang A, Halmi KA. More males seek treatment for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1999;25:415–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pope HG Jr, Olivardia R, Gruber A, Borowiecki J. Evolving ideals of male body image as seen through action toys. Int J Eat Disord 1999;26:65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Law C, Labre MP. Cultural standards of attractiveness: A thirty-year look at changes in male images in magazines. J Mass Commun Q 2002;79:697–711. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leit RA, Pope HG Jr, Gray JJ. Cultural expectations of muscularity in men: The evolution of playgirl centerfolds. Int J Eat Disord 2001;29:90–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Courtenay WH. Key determinants of the health and well-being of men and boys. Int J Men Health 2003;2:1–30. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eagles JM, McLeod IH, Mercer G, Watson F. Seasonality of eating pathology on the Eating Attitudes Test in a nonclinical population. Int J Eat Disord 2000;27:335–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lam RW, Goldner EM, Grewal A. Seasonality of symptoms in anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 1996;19:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, Falkner NH, Beuhring T, Resnick MD. Sociodemographic and personal characteristics of adolescents engaged in weight loss and weight/muscle gain behaviors: Who is doing what? Prev Med: Int J Devoted Pract Theory 1999;28:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crago M, Shisslak CM. Ethnic differences in dieting, binge eating, and purging behaviors among American females: A review. Eat Disord: J Treat Prev 2003;11:289–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katzman MA, Hermans KME, Hoeken DV, Hoek HW. Not your “typical island woman”: Anorexia nervosa is reported only in subcultures in Curacao. Cult Med Psychiatry 2004;28:463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker S, Nichter M, Nichter M, Vuckovic N, Sims C, Ritenbaugh C. Body image and weight concerns among African American and White adolescent females: Differences that make a difference. Hum Organ 1995;54:103–114. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ogden CL, Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in overweight among US children and adolescents, 1999–2004. JAMA 2002;288:1728–1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beamon K, Bell PA. “Going Pro”: The deferential effects of high aspirations for a professional sports career on African-American student athletes and White student athletes. Race Soc 2002;5:179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franko DL, Becker AE, Thomas JJ, Herzog DB. Cross-ethnic differences in eating disorder symptoms and related distress. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40:156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaw H, Ramirez L, Trost A, Randall P, Stice E. Body image and eating disturbances across ethnic groups: More similarities than differences. Psychol Addict Behav 2004;18:12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Regan PC, Cachelin FM. Binge eating and purging in a multi-ethnic community sample. Int J Eat Disord 2006;39:523–526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wadden TA, Brownell KD, Foster GD. Obesity: Responding to the global epidemic. J Consult Clin Psychol 2002;70:510–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heinberg LJ, Thompson JK, Matzon JL. Body image dissatisfaction as a motivator for healthy lifestyle change: Is some distress beneficial?. In: Striegel-Moore R, Smolak L, editors. Eating Disorders: Innovative Directions in Research and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beglin SJ, Fairburn CG. Women who choose not to participate in surveys on eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord 1992;12:113–116. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Becker AE, Fay K, Gilman SE, Striegel-Moore R. Facets of acculturation and their diverse relations to body shape concern in Fiji. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.George VA, Erb AF, Harris CL, Casazza K. Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders in Hispanic females of diverse ethnic background and non-Hispanic females. Eat Behav 2007;8:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patton GC, Selzer R, Coffey C, Carlin JB, Wolfe R. Onset of adolescent eating disorders: Population based cohort study over 3 years. Br Med J 1999;318:765–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]