Classic Bladder Exstrophy – Timing of initial closure and technical highlights

The timing for initial reconstruction of the bladder and abdominal wall in Classic Bladder Exstrophy (CBE) has typically been performed in the immediate newborn period, in both the Modern Staged Repair of Exstrophy (MSRE) or the Complete Primary Repair of Exstrophy (CPRE) protocols. The benefit of immediate surgical closure (typically in the first 72 hours) was due to the fact that many children could be managed without resorting to osteotomy, due to the malleability of the pelvis. The concerns about the potential short and longer term impact of osteotomy have largely waned due to improvements in the orthopedic surgical management1, use of external fixation, and ability to provide sedation and pain control to infants and children2. Additionally, ongoing understanding on how to protect the bladder template and permitting a too-small-to-close bladder template time to grow also influences the reasoning behind the timing of initial bladder closure. Two other social factors have also led to delaying immediate reconstruction – the desire to provide time for maternal/parental-child bonding and the accessibility of an appropriate center for care with experts in the management of exstrophy.

Delay in initial closure until 3 – 4 months of age is now the norm for most infants in the United States. Though this represents a substantial change from historical teaching there seems to be consensus that initial bladder closure after the first 72 hours with the use of osteotomy and very secure 1-month-long postoperative immobilization provides equivalent successful outcome. The most common complication noted in a large series of closures performed after the first 30 days of life was unanticipated transfusion3. Studies on the children undergoing closure at various time points in the first year of life seem to indicate a negative impact on bladder growth among those closed beyond 9 months of age4.

The ideal timing for primary bladder closure is thus now considered to be in the first year of life, preferably before the ninth month. This timing, however, is not possible in many parts of the world, where patients may not present until well beyond this ideal time and/or available intensive immediate post operative care for infants may be lacking. When closure is delayed due to unforeseen or unchangeable circumstances, the primary goal should be to provide a secure bladder and abdominal wall closure at the first operation, as repeated attempts at closure further compromise long term bladder growth.

Multiple techniques exist for the primary reconstruction of Classic Bladder Exstrophy. The staged repair, described initially by Jeffs5, has had the longest clinical experience and continues to demonstrate a very high degree of success. Over the years, considerable changes have been made to the initial described approach and timing of the various parts of the staged reconstruction. In its current iteration, the Modern Staged Repair of Exstrophy (MSRE) proceeds in two (in females) or three (in males) separate surgeries: one, initial secure abdominal wall and bladder closure (males and females); two, epispadias repair before 24 months (males only); and three, a definitive continence procedure using a Young-Dees-Leadbetter bladder neck reconstruction when the child is able to participate in an appropriate voiding program (males and females). This modified staged approach has also been widely accepted and has had good outcomes in terms of maintenance of a secure abdominal wall closure, cosmetic and functional penile outcomes, and eventual continence.

Primary bladder closure and abdominal wall reconstruction

The initial step in the MSRE is the secure closure of the bladder and abdominal wall, which sets the stage for future procedures and ultimately urinary continence. In the MSRE, the birth defect is converted from a bladder exstrophy to a proximal epispadias. An intrinsic aspect of every stage of exstrophy management is a dedicated, well-trained, and highly knowledgeable team with expertise in all aspects of exstrophy management. This includes pediatric urologists or surgeons, pediatric orthopedic surgeons, pediatric anesthesiologists adept in postoperative pain management, expert pre-, intra-, and post-operative nurses, psychologists or psychiatrists that have experience in managing complex medical conditions, and social workers that can assist the family through a very challenging multi-staged reconstructive process.

Preoperative evaluation and management

Preoperative preparation should include a comprehensive evaluation of the child’s medical status, including determination of normal blood counts and metabolic profiles. Ultrasound evaluation of the kidneys prior to closure is useful to demonstrate normal renal anatomy. Studies have shown that 2.8% of children with CBE have associated renal anomalies6. While not an exclusion criterion for staged reconstruction, knowledge of renal anomalies will help in postoperative fluid management and also allow for ongoing monitoring of renal outcomes. Preservation of renal function in classic bladder exstrophy remains a key determinant of the success of reconstruction7. Where available, magnetic resonance imaging, has been utilized to evaluate the pelvic floor and its changes that occur with successful reconstruction8, 9.

Bladder evaluation and protection

At birth or on initial evaluation, careful evaluation of the patient and the bladder template are crucial to determine the best time for surgical reconstruction. The bladder template is evaluated in the infant by carefully inverting the bladder template into the abdomen using a sterile technique. Some templates may already present inverted, and in this case, there may be more bladder template that is evident on exam than visually noted before the exam. If the exstrophied bladder template can be easily inverted well into the abdomen and pushed underneath the abdominal wall fascia with gentle pressure, then the template is considered large enough to close. Another general rule of thumb is that the closed bladder should be able to fit around a 10Fr Malecot catheter. This typically translates to at least a 3cm diameter bladder template. The presence of polyps on the bladder template should also be noted, as these may be so numerous that they compromise the amount of template available for closure. Polyps were noted more commonly in those patients that had delay in closure10, and typically were associated with squamous metaplastic change, although no dysplasia was noted10. Resection of the polyps at the time of closure is appropriate.

A very small bladder template < 3cm in diameter at birth is a reason to consider delaying closure. When closure was delayed in this circumstance, later closure with osteotomies and external fixation was very successful11. Despite the successful delayed closure, the time to continence was prolonged due to slower bladder growth and most patients eventually required a catheterization regimen using a continent channel (i.e., a Mitrofanoff) to be dry11. Other studies indicated that while a small bladder template will grow following closure, the eventual capacity that is achieved will still be smaller than those starting with a larger bladder template12.

Since immediate postnatal closure is becoming more infrequent, protection of the bladder template becomes more crucial to prevent damage and metaplastic changes to the bladder mucosa. This protection should start at birth by avoiding large plastic clips to clamp the umbilical cord. A more suitable alternative is to use silk ties to ligate the umbilical cord; this will prevent damage to the bladder template. Additionally, the bladder template must be covered with a protective barrier. Using saline to moisten the bladder template and then using non adherent thin plastic wrap will prevent drying of the mucosa and keratinization. Alternatives to plastic wrap include a gauze saturated in petroleum-based ointment. An uncovered bladder template can be very sensitive and painful, and is subject to metaplastic changes.

Good parental preparation is critical to ensure that families understand the extent of the surgical undertaking and the lengthy postoperative course that is typically required for success. Additionally, having good family and social supports plays an integral part in the eventual surgical and clinical success of the child with exstrophy.

Initial surgical management closes the bladder and proximal urethra and places it deep in the pelvis, which allows for tension free closure of the abdominal wall. This is best achieved with the use of osteotomy if the closure is beyond the first 72 hours of life.

Intraoperative management

An experienced operative team is very important to the eventual successful outcome. Strict attention to detail remains a hallmark for success and includes accurate placement of postoperative drainage catheters and exact placement of epidural catheters and osteotomy pins. Access to intraoperative fluoroscopic imaging is helpful for successful placement of epidural catheters as well as rapid evaluation of pin location during osteotomy. All patients are managed with a combined general and epidural analgesia approach13. Placement of central intravenous access is very helpful in the immediate post operative phase to provide fluids, antibiotics, and pain medications, particularly when the patient is not receiving oral intake. Placement of central lines is also made easier by using intraoperative fluoroscopy.

The entire lower aspect of the child below the chest is prepped into the operative field. This permits all aspects of the procedure to be performed without the need for repreparation and draping. Osteotomies are performed and pins are placed in the various fragments following the osteotomy. The bladder template can then be dissected and closed along with the posterior urethrovesical junction.

The bladder template and paraexstrophy skin flaps are identified by their mucosal-like or pinkish appearance relative to the normal skin tone lateral to the bladder plate and urethra. The umbilical stump is typically included in the initial dissection. This stump can serve as an anchor for a holding stitch or instrument to aide exposure and provide traction; the stump is transected before bladder closure. Below the skin, the surgeon should take care to identify the rectus fascia (which will be diastatic), the peritoneum, and the right and left umbilical arteries. The most technically challenging component of the case is the separation of the intersymphyseal bands; their complete dissection is crucial to ensure that the posterior urethra/vesicourethral unit can be placed deep in the pelvis. The intersymphyseal bands are identified as shiny white tissue originating from the pubic symphysis and passing medially toward and inserting on the epispadiac posterior urethra and bladder neck. Failure to release these bands could lead to bladder prolapse or complete wound dehiscence, which happens because the vesicourethral unit is still tethered anteriorly by these bands. The bands’ color and texture appears almost like fascia. A surgical tip to evaluate whether the intersymphyseal bands are appropriately dissected is for the surgeon to run their finger along the medial aspect of the pubis. If there is a tight, distinct piece of fibrous tissue, then more dissection is required. However, extreme care and a slow, deliberate, and measured dissection as the surgeon approaches the inferior aspect of the pubic symphysis is absolutely required. This is because the corpora cavernosa are attached to the inferior aspect of the pubic ramus; failure to identify the corpora could result in ischemic injury to the penis. Given the bony pelvic abnormality in exstrophy, the corpora are more anterior or close to the skin surface that typical. Their rounded, rod-like structure and soft feel is distinct from the shiny, white intersymphyseal bands. It should also be noted that at the time of bladder closure using the MSRE, the bladder neck does not undergo any reconstruction or tapering as is frequently done in the CPRE.

Approximation of the pubic bones is best done with a No. 2 nylon modified horizontal mattress suture on a large tapered needle14. Erosion of the intrapubic stitch into the soft tissues is possible, but this can be minimized by using a modified mattress-type suture placement (Figures 1a and 1b). A large, tapered needle should be used, and the suture passed to keep it and the knot on the anterior surface of the pubis.

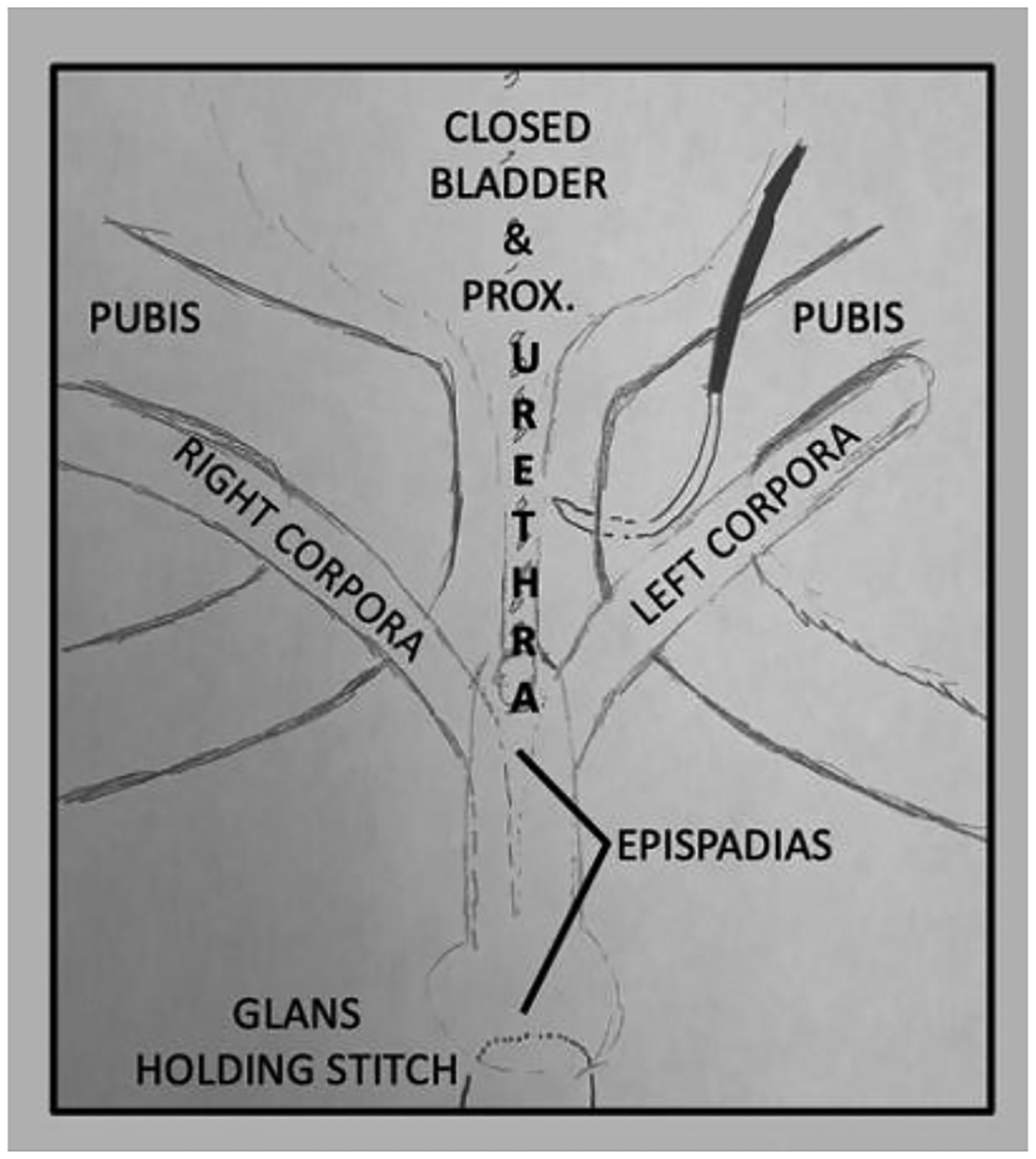

FIGURE 1a:

Anatomy prior to pubic closure

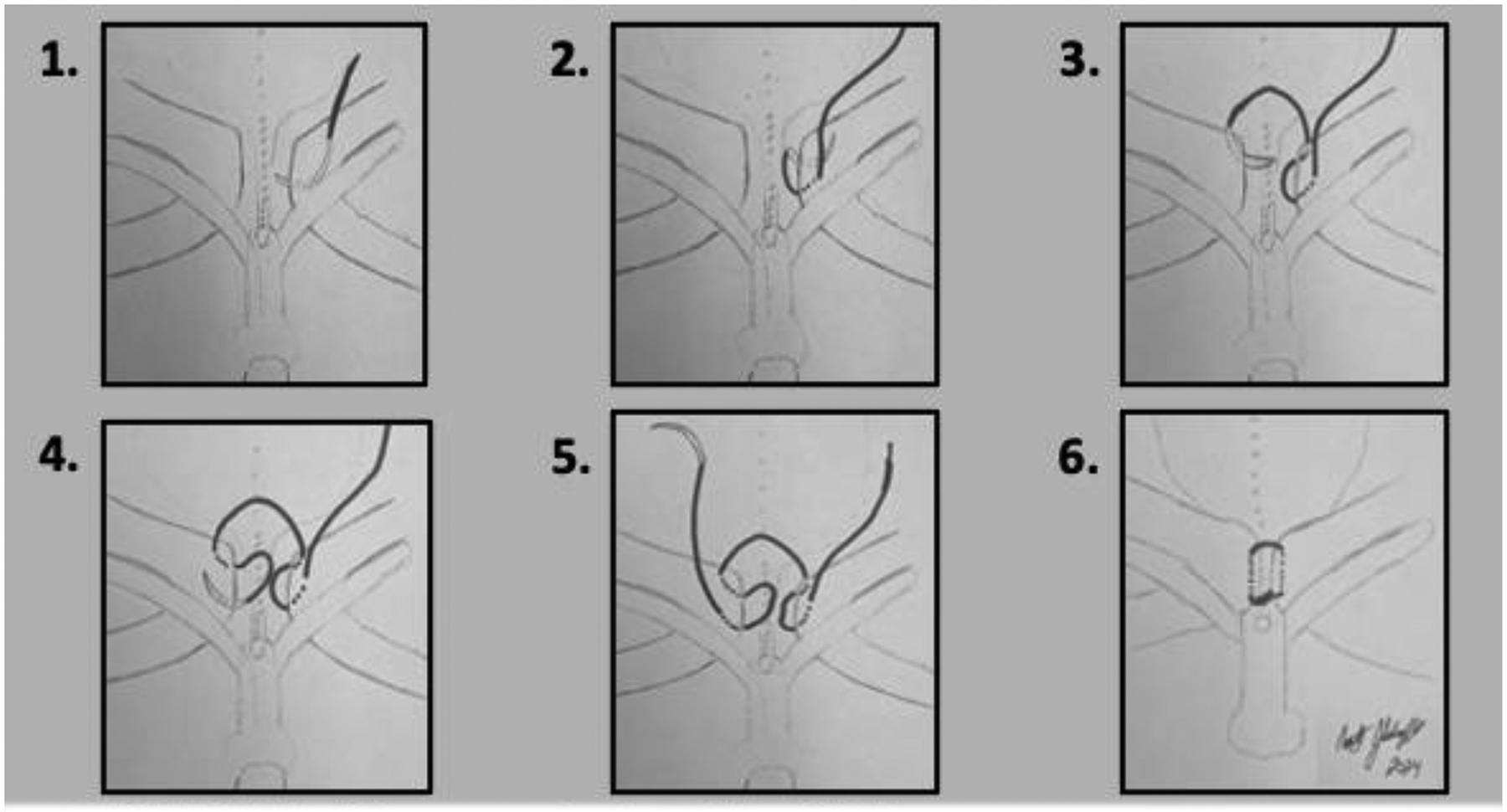

FIGURE 1b: Placement of pubic stitch.

A modified horizontal mattress stitch using #2 nylon on a large tapered needle is placed to lower risk of stitch erosion into urethra or bladder. No stitch crosses directly over the closed bladder/urethra, and the knot is on anterior side of closed pubis.

An off-the-shelf regenerative tissue matrix (such as Alloderm RTM, Allergan Aesthetics, an Abbvie Company, Lake Bluff, IL, USA) can be used, if desired, as an additional protective layer between the closed urethra and bladder. This serves to reduce the possibility of stitch erosion into the soft tissues. A small rectangle of the regenerative tissue matrix is be laid over the closed proximal urethra and bladder neck and sewn to more lateral soft tissue. Three surgeons are needed to successfully tie the pubic stitch: one surgeon places their index fingers on the greater trochanters and their thumb on the pubis/pubic rami and rotates the pelvis anterior and medially, thereby reducing the pubic diastasis; a second surgeon exposes the apposed pubis and removes any fluid with suction; and the third surgeon ties the knot. Tying the pubic stitch introduces a slight bend in the corpora cavernosa, which places them at risk for venous congestion. The surgeon must observe the penis. If it stays ischemic, the pubic stitch should be removed and a fresh stitch placed more anteriorly in the pubis, which moves the stitch farther away from the corpora, reduces their bend, and lowers the risk of penile loss. Bladder drainage is maintained with ureteral stents and suprapubic tubes. Good bladder drainage is important to the stability of the bladder and abdominal wall closures. Ensuring that tubes and stents are in excellent position and draining well prior to completion of the procedure lessens the concern for postoperative problems caused by inadequate drainage.

Combining bladder closure and epispadias repair is considered in select older boys. While this is done as a standard component of the “complete” repair (also referred to as the Complete Primary Repair of Exstrophy (CPRE)) as described by Grady et al15, 16, this has also been successfully used in the context of the staged reconstruction in select older boys. Epispadias repair is performed using the Cantwell-Ransley technique17, 18. Limiting the use of this technique (i.e., combined bladder closure and epispadias repair) to older boys has avoided the issues of penile and corporal tissue loss, a devastating and irreversible complication seen with other techniques19, 20.

Postoperative management

Postoperative traction and immobilization with an external fixation device is instituted at the end of the operative procedure, and care is required during patient transfer out of the operative theater to make sure that the pelvis remains stable for 4 – 6 weeks. Traction is performed using a modified Buck’s technique as described by Sponseller et al21. Intermittent radiologic evaluation is performed to make sure that pelvic healing is progressing. Transfusion may be required to accommodate for blood loss from the osteotomies22, 23. The reader is directed to other manuscripts in this edition of the journal for more details on pelvic osteotomies and multimodal postoperative pain management.

Other aspects of successful postoperative management include reducing abdominal distension with the use of nasogastric drainage to decrease tension on the abdominal wall closure. Also, central venous access will permit hydration in the immediate postoperative period and can also be used for parenteral nutrition in those patients that have delay in return of bowel function. They can also be critical is providing pain control in the event of early dislodgement of epidural catheters.

The success of postoperative management is highly dependent on a well-trained nursing staff with experience administering care and recognizing and troubleshooting problems in exstrophy patients after their initial closure. The first 72 hours are best managed in an intensive care setting (i.e., with a 1:1 nurse-to-patient ratio), with gradual reduction in intensive care needs after the patient’s pain control regimen becomes apparent, bowel function returns, and their overall medical situation stabilizes. The nurses ability to rapidly identify and successfully act upon problems such as dusky appearance of the penis, the lack of drainage from ureteral and suprapubic catheters, significant patient discomfort leading to increased movement of the pelvis, or noticeable increases in abdominal girth (from possible ileus) are critical to the success of the operative procedure and cannot be minimized.

Failure of Reconstruction

Multiple factors have been identified that lead to failure of reconstruction. These include intraoperative factors such as inadequate dissection of the pelvic floor, leading to superficial placement of the bladder and posterior urethra24, and lack of good bladder drainage with appropriate stents and tubes25. Arguably the most important factor in failure of initial reconstruction, however, seems to be lack of good pelvic fixation and use of osteotomies26.

Failure of reconstruction has significant short and long term impacts on the patient and family. Failure of initial reconstruction has been associated with decreased potential for bladder growth and voided continence27, 28. Although reclosure with the use of osteotomies has been shown to have good success rates, successful initial closure, remains a crucial first step for the attainment of functional success in classic bladder exstrophy reconstruction.

Conclusions

The timing of initial surgical reconstruction for bladder and abdominal wall closure is determined by multiple factors. Immediate newborn closure, while reducing the need for osteotomy, may not be easily achievable. Delaying closure, may have the benefit of allowing parental bonding and providing care at a center of excellence. Improvements in the surgical management of Classic Bladder Exstrophy, using a staged reconstructive approach, have been shown to provide excellent surgical and functional outcomes, that can be reproduced in most clinical settings.

Table 1:

Important considerations regarding primary bladder exstrophy closure

| 1) Historical teaching suggested that all bladder exstrophy closures should be performed with great urgency within the first 72 hours postnatally. When closed within this timeframe, pelvic osteotomies are most often not required. |

| 2) Today, delayed primary bladder exstrophy closure (within the first 9 months of life) is the new norm in the United States. |

| 3) Delayed closure advantages include parent-child bonding and more easy scheduling of procedure. The main disadvantage of delayed primary bladder closures, however, is that it uniformly requires pelvic osteotomies, which adds additional morbidity. |

4) Key maneuvers the promote success of the initial bladder closure include:

|

5) The following healthcare providers are crucial components of a multidisciplinary exstrophy team:

|

FUNDING:

Dr. Schaeffer is supported in part by career development award NIH DK00119535.

Abbreviations

- CBE

Classic Bladder Exstrophy

- MSRE

Modern Staged Repair of Exstrophy

- CPRE

Complete Primary Repair of Exstrophy

Footnotes

- R.I.M. contributed to the outline and study design, and wrote all versions of the manuscript

- A.J.S. contributed to the outline and study design, created the figures, and reviewed and edited all versions of the manuscript

- J.P.G. reviewed the final draft of the manuscript

- This work is not under submission at any other scientific journal and has not been published previously.

- This is our original work.

- The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

-

The authors declare that this submission is in accordance with the principles laid down by the Responsible Research Publication Position Statements as developed at the 2nd World Conference on Research Integrity in Singapore, 2010.This narrative review/study is exempt from Institutional Review Board approval because it did not involve human subjects.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sholklapper TN, Crigger C, Haney N, et al. Orthopedic complications after osteotomy in patients with classic bladder exstrophy and cloacal exstrophy: a comparative study. J Pediatr Urol. Oct 2022;18(5):586.e581–586.e588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khandge P, Wu WJ, Hall SA, et al. Osteotomy in the newborn classic bladder exstrophy patient: A comparative study. J Pediatr Urol. Aug 2021;17(4):482.e481–482.e486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morrill CC, Manyevitch R, Haffar A, et al. Complications of delayed and newborn primary closures of classic bladder exstrophy: Is there a difference? J Pediatr Urol. Jan 4 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu WJ, Maruf M, Harris KT, et al. Delaying reclosure of bladder exstrophy leads to gradual decline in bladder capacity. J Pediatr Urol. Jun 2020;16(3):355.e351–355.e355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeffs RD. Functional closure of bladder exstrophy. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1977;13(5):171–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stec AA, Baradaran N, Gearhart JP. Congenital renal anomalies in patients with classic bladder exstrophy. Urology. Jan 2012;79(1):207–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaeffer AJ, Stec AA, Baradaran N, Gearhart JP, Mathews RI. Preservation of renal function in the modern staged repair of classic bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol. Apr 2013;9(2):169–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aboul Ela W, El Zoheiry M, Shouman A, et al. Assessment of the anterior osteotomy role in the restoration of normal pelvic floor anatomy for bladder exstrophy patients using pre and postoperative pelvic floor MRI. J Pediatr Urol. Dec 2020;16(6):835.e831–835.e839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tekes A, Ertan G, Solaiyappan M, et al. 2D and 3D MRI features of classic bladder exstrophy. Clin Radiol. May 2014;69(5):e223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Novak TE, Lakshmanan Y, Frimberger D, Epstein JI, Gearhart JP. Polyps in the exstrophic bladder. A cause for concern? J Urol. Oct 2005;174(4 Pt 2):1522–1526; discussion 1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Carlo HN, Maruf M, Jayman J, Benz K, Kasprenski M, Gearhart JP. The inadequate bladder template: Its effect on outcomes in classic bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Urol. Oct 2018;14(5):427.e421–427.e427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arena S, Dickson AP, Cervellione RM. Relationship between the size of the bladder template and the subsequent bladder capacity in bladder exstrophy. J Pediatr Surg. Feb 2012;47(2):380–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kost-Byerly S, Jackson EV, Yaster M, Kozlowski LJ, Mathews RI, Gearhart JP. Perioperative anesthetic and analgesic management of newborn bladder exstrophy repair. J Pediatr Urol. Aug 2008;4(4):280–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sussman JS, Sponseller PD, Gearhart JP, Valdevit AD, Kier-York J, Chao EY. A comparison of methods of repairing the symphysis pubis in bladder exstrophy by tensile testing. Br J Urol. Jun 1997;79(6):979–984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grady RW, Carr MC, Mitchell ME. Complete primary closure of bladder exstrophy. Epispadias and bladder exstrophy repair. Urol Clin North Am. Feb 1999;26(1):95–109, viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grady RW, Mitchell ME. Newborn exstrophy closure and epispadias repair. World J Urol. 1998;16(3):200–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baird AD, Mathews RI, Gearhart JP. The use of combined bladder and epispadias repair in boys with classic bladder exstrophy: outcomes, complications and consequences. J Urol. Oct 2005;174(4 Pt 1):1421–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gearhart JP, Mathews R, Taylor S, Jeffs RD. Combined bladder closure and epispadias repair in the reconstruction of bladder exstrophy. J Urol. Sep 1998;160(3 Pt 2):1182–1185; discussion 1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cervellione RM, Husmann DA, Bivalacqua TJ, Sponseller PD, Gearhart JP. Penile ischemic injury in the exstrophy/epispadias spectrum: new insights and possible mechanisms. J Pediatr Urol. Oct 2010;6(5):450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Husmann DA, Gearhart JP. Loss of the penile glans and/or corpora following primary repair of bladder exstrophy using the complete penile disassembly technique. J Urol. Oct 2004;172(4 Pt 2):1696–1700; discussion 1700–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wild AT, Sponseller PD, Stec AA, Gearhart JP. The role of osteotomy in surgical repair of bladder exstrophy. Semin Pediatr Surg. May 2011;20(2):71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Preece J, Asti L, Ambeba E, McLeod DJ. Peri-operative transfusion risk in classic bladder exstrophy closure: Results from a national database review. J Pediatr Urol. Aug 2016;12(4):208.e201–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maruf M, Jayman J, Kasprenski M, et al. Predictors and outcomes of perioperative blood transfusions in classic bladder exstrophy repair: A single institution study. J Pediatr Urol. Oct 2018;14(5):430.e431–430.e436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Frimberger D, Gearhart JP, Mathews R. Female exstrophy: failure of initial reconstruction and its implications for continence. J Urol. Dec 2003;170(6 Pt 1):2428–2431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bertin KD, Serge KY, Moufidath S, et al. Complex bladder-exstrophy-epispadias management: causes of failure of initial bladder closure. Afr J Paediatr Surg. Oct–Dec 2014;11(4):334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novak TE. Failed exstrophy closure. Semin Pediatr Surg. May 2011;20(2):97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massanyi EZ, Shah BB, Baradaran N, Gearhart JP. Bladder capacity as a predictor of voided continence after failed exstrophy closure. J Pediatr Urol. Feb 2014;10(1):171–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Novak TE, Costello JP, Orosco R, Sponseller PD, Mack E, Gearhart JP. Failed exstrophy closure: management and outcome. J Pediatr Urol. Aug 2010;6(4):381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]