Abstract

The disruption of a specific gene in Candida albicans is commonly used to determine the function of the gene product. We disrupted AAF1, a gene of C. albicans that causes Saccharomyces cerevisiae to flocculate and adhere to endothelial cells. We then characterized multiple heterozygous and homozygous mutants. These null mutants adhered to endothelial cells to the same extent as did the parent organism. However, mutants with presumably the same genotype revealed significant heterogeneity in their growth rates in vitro. This heterogeneity was not the result of the transformation procedure per se, nor was it caused by differences in the expression or function of URA3, a marker used in the process of gene disruption. The growth rate among the different heterozygous and homozygous null mutants was positively correlated with in vivo virulence in mice. It is possible that the variable phenotypes of C. albicans were due to mutations outside of the AAF1 coding region that were introduced during the gene disruption process. These results indicate that careful phenotypic characterization of mutants of C. albicans generated through targeted gene disruption should be performed to exclude the introduction of unexpected mutations that may influence pathogenicity in mice.

A general approach to determining the contribution of a gene product to the virulence of Candida albicans is the production of null mutants. Because C. albicans is a diploid species, both alleles of the gene must be deleted (5). The resultant null mutant can then be tested for the absence of the phenotype for which the gene is putatively responsible, as well as reduction in virulence in a relevant animal model.

We have been working to characterize potential adhesins that mediate the attachment of C. albicans to human endothelial cells. Using complementation cloning, we identified a candidal gene that when expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae causes the transformed organisms to flocculate and exhibit increased adherence to endothelial cells (6). This gene was found to be identical to AAF1, a gene discovered by Barki et al. that causes S. cerevisiae to adhere to plastic and buccal epithelial cells (2).

Although AAF1 induces an adherent phenotype in S. cerevisiae, it appears to encode a regulatory factor rather than an adhesin expressed on the cell surface. For example, when AAF1 is expressed in S. cerevisiae, its gene product localizes to the cytoplasm and nucleus but not the cell wall (6). Also, the predicted Aaf1 protein lacks features typical of a surface protein such as a transmembrane sequence or a signal peptide (6).

In this study, to examine the function of the AAF1 gene product in C. albicans, we constructed multiple heterozygous and homozygous aaf1 null mutants and characterized their growth rates, their interactions with endothelial cells in vitro, and their virulence in the mouse model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis. We discovered that the phenotypes of different clones of these null mutants varied significantly, even though the mutants were predicted to be genotypically identical. Although the cause of this phenotypic variability remains uncertain, the presence of this variability suggests that multiple independent clones should be characterized when the effects of gene disruption on the pathogenicity of C. albicans are evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

The strains of C. albicans used in this investigation are described in Tables 1 and 2. C. albicans CAI-4 is an ura-negative derivative of SC5314 (5). CAI-4 was used for disruption of AAF1. The coding sequence of AAF1 with the flanking regions for the disruption construct were cloned from C. albicans ATCC 36082 as well as SC5314. The phenotypic features of the aaf1 mutants were compared to those of SC5314. CAI-12, a URA3 revertant strain of CAI-4, was kindly provided by William Fonzi (Georgetown University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.).

TABLE 1.

Strains of C. albicans used and/or created in which the AAF1 disruption cassette was constructed with DNA from C. albicans 36082

| Strain | Genotype | Endothelial cell adherencea (%) | Doubling timea (h) | Survival timeab (days) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC5314 | AAF1/AAF1 URA3/URA3 | 25 (12–32) | 1.38 (1.26–1.53) | 2 | W. A. Fonzi |

| 36082 | AAF1/AAF1 URA3/URA3 | 35 (26–43) | —c | — | ATCC |

| CAI-4 | AAF1/AAF1 Δura3::imm43/Δura3::imm43 | — | — | — | W. A. Fonzi |

| CAI-12 | AAF1/AAF1 Δura3::imm434/URA3 | — | 1.37 (1.34–1.40) | W. A. Fonzi | |

| CU1 | AAF1/Δaaf1::hisG-URA3-hisG Δura3::imm43/Δura3::imm43 | 23 (14–26) | 1.68 (1.56–1.79)d | 5e | This work |

| CU2 | AAF1/Δaaf1::hisG-URA3-hisG Δura3::imm43/Δura3::imm43 | 15 (14–17) | 1.58 (1.50–1.71)d | 6e | This work |

| CU4 | AAF1/Δaaf1::hisG-URA3-hisG Δura3::imm43/Δura3::imm43 | 21 (12–29) | 1.75 (1.64–1.97)d | 9e | This work |

| CU5 | AAF1/Δaaf1::hisG-URA3-hisG Δura3::imm43/Δura3::imm43 | 35 (28–41) | 1.95 (1.66–2.17)d | >16e | This work |

| CU6 | AAF1/Δaaf1::hisG-URA3-hisG Δura3::imm43/Δura3::imm43 | 32 (20–33) | 1.91 (1.69–2.04)d | 13e | This work |

| CHU18 | Δaaf1::hisG/Δaaf1::hisG-URA3-hisG Δura3::imm43/Δura3::imm43 | 42 (31–45) | 1.62 (1.48–1.68) | 7e | This work |

| CHR1 | Δaaf1::hisG/Δaaf1::hisG AAF1 URA3 Δura3::imm43/Δura3::imm43 | 33 (32–34) | 1.53 (1.34–1.83) | 3 | This work |

Results are medians, and numbers in parentheses are the first to third quartiles.

Survival time of mice after intravenous infection with the indicated strain.

—, not determined.

P < 0.016 in comparison to SC5314.

P < 0.004 in comparison to SC5314.

TABLE 2.

Strains of C. albicans created in which the AAF1 disruption cassette was constructed with DNA from C. albicans SC5314

|

C. albicans strain

|

Endothelial cell adherencea (%) | Doubling timea (h) | Source | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent (AAF1/AAF1) | Heterozygote (AAF1/Δaaf1) | Homozygote (Δaaf1/Δaaf1) | |||

| SC5314 | 31 (29–34) | 1.31 (1.22–1.47) | W. A. Fonzi | ||

| H1 | —b | 1.46 (1.31–1.48) | This work | ||

| NM11 | — | 1.45 (1.25–1.55) | This work | ||

| NM12 | 34 (32–35) | 1.41 (1.33–1.69) | This work | ||

| H3 | — | 1.56 (1.55–1.65)c | This work | ||

| NM31 | 28 (27–31) | 1.81 (1.50–1.99)c | This work | ||

| H4 | — | 1.59 (1.48–1.81) | This work | ||

| NM41 | — | 1.83 (1.62–1.97)d | This work | ||

| NM42 | — | 1.80 (1.54–1.97)d | This work | ||

| H6 | — | 1.42 (1.28–1.57) | This work | ||

| NM61 | — | 1.48 (1.33–1.66) | This work | ||

| NM62 | — | 1.44 (1.27–1.47) | This work | ||

Values are medians, and numbers in parentheses are the first to third quartiles.

—, not determined.

P < 0.04 compared to SC5314.

P < 0.002 compared to SC5314.

Growth media and conditions.

All C. albicans strains were maintained on YPD medium (1% yeast extract [Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.], 2% Bacto Peptone [Difco], 2% [wt/vol] glucose). For long-term storage, the organisms were kept in 17% glycerol at −70°C. Minimal defined medium (YNB) consisted of 2% glucose, 1× yeast nitrogen base broth without ammonium sulfate (Difco), and 0.5% ammonium sulfate. The growth rates of SC5314, CAI-12, and the different aaf1 mutants were determined in YPD with or without supplemental uridine.

Construction of the aaf1 null mutants.

AAF1 was deleted from C. albicans CAI-4 via targeted mutagenesis by the method of Fonzi and Irwin (5). Plasmid pMB7 containing the hisG::URA3::hisG cassette was digested with HindIII. This hisG::URA3::hisG cassette was inserted into the NheI and KpnI sites of AAF1, leaving the flanking regions of the AAF1 gene locus on either end of the hisG::URA3::hisG sequence (Fig. 1A). This construct was then linearized by digestion with XhoI and used to transform C. albicans CAI-4 by the lithium acetate-polyethylene glycol (LiAc-PEG) method as described by Gietz and Schiestl (8). Transformants were selected by plating on YNB agar without uridine. Several of these aaf1 (hisG::URA3::hisG)/AAF1 heterozygous mutants were then grown on YNB medium supplemented with uridine and 5′-fluoorotic acid to select for the loss of the URA3 gene due to intrachromosomal hisG recombination (2). These ura3-negative aaf1 (hisG)/AAF1 heterozygous mutants were again transformed with the hisG::URA3::hisG cassette and selected as described above for deletion of the second AAF1 allele.

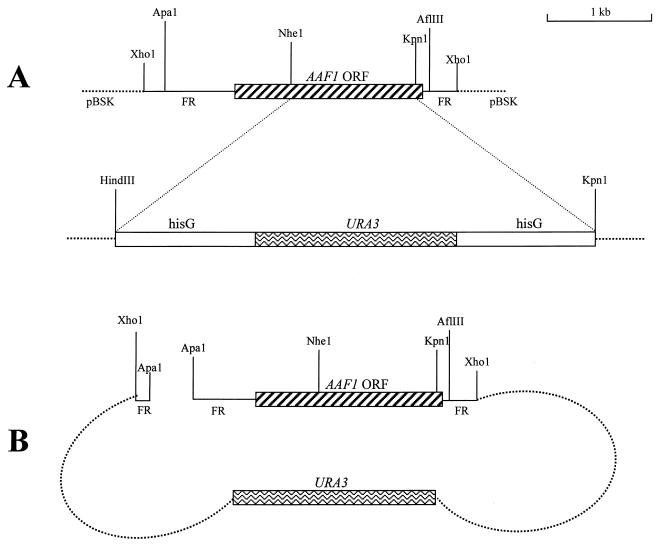

FIG. 1.

Disruption and reintroduction of AAF1 in C. albicans. (A) Construction of the AAF1 disruption cassette. A 1.2-kb segment in the AAF1 open reading frame was disrupted by the hisG::ura3::hisG cassette. (B) Construction of the cassette used to reintroduce AAF1 into the null mutant. ORF, open reading frame; FR, flanking region.

AAF1 was reintroduced into the aaf1 null mutant strain by using a modified pBSK vector containing AAF1 and URA3. The pBSK vector was modified by destroying the ApaI site. The 2.9-kb AAF1 gene was cloned into this modified vector at the XhoI site. URA3 was acquired from pMB7 by PCR using the following primers: 5′ AGCTCTAGAAGGACCAC 3′ and 5′ GCTCTAGATAAGCTACTAATAGGAAT 3′. Both primers were designed to contain XbaI sites. URA3 was then cloned into the pBSK vector at the XbaI site. This vector, containing AAF1 and URA3, was then linearized by digestion with ApaI at a site in the flanking region (Fig. 1B) and transformed into the homozygous aaf1 null mutant. URA3 functioned as the selection marker for positively transformed cells.

A second series of aaf1 null mutants was constructed using the 2.9-kb AAF1 sequence from C. albicans SC5314. This second series of mutants was constructed to minimize any changes in the regions flanking AAF1 that may have been introduced during the disruption procedure. AAF1 with the flanking region was acquired from SC5314 by using High Fidelity PCR (Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.) with the following primers: 5′ TCACCT CGAGAATTGGGATACA 3′ and 5′ AGAGTTGGGACT CGAGTTGATA 3′. All gene disruptions were confirmed by Southern blot analysis.

Growth rate determination.

C. albicans SC5314, the aaf1 mutants, and CAI-12 were grown in YPD medium without supplemental uridine for 18 h on a rotary shaker (200 rpm) at 30°C. The cells were then washed in saline and counted with a hemacytometer. They were adjusted to a cell count of 104 per ml and used to inoculate 250 ml of fresh YPD medium without supplemental uridine to a final optical density of 0.015 to 0.020 at 600 nm. The optical density was measured every hour until the stationary phase of the growth curve was reached. The doubling time during the log phase was determined by the following formula: ln 2 × t/(ln b − ln a) (t is the time period in hours; a is the optical density at the beginning of time period; b is the optical density at the end of time period) (17).

Endothelial cells.

Endothelial cells were obtained from human umbilical cord veins by the method of Jaffe et al. (13). The cells were grown in M-199 medium (Gibco, Grand Island, N.Y.) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Intergen, Purchase, N.Y.), 10% defined bovine calf serum (HyClone, Logan, Utah), l-glutamine, penicillin, and streptomycin. Second-passage cells were grown to confluence in 6- or 24-well tissue culture plates (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, N.J.) coated with 0.2% gelatin. All endothelial cell cultures were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37°C. All reagents were tested for endotoxin in a chromogenic Limulus amebocyte lysate assay (BioWhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, Md.). The endotoxin concentrations were less than 0.01 IU/ml.

In vitro adherence to endothelial cells.

The adherence of C. albicans SC5314 and aaf1 mutants to endothelial cells was determined by our previously described method, using six-well tissue culture plates (12). Briefly, 3 × 102 organisms in Hanks balanced salt solution (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, Calif.) were added to each well of endothelial cells. The inoculum size was verified by quantitative culture on YPD agar plates. After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 30 min, the nonadherent organisms were aspirated and the endothelial cell monolayer was rinsed twice with Hanks balanced salt solution. The wells were then overlaid with YPD agar and incubated at 30°C for 24 h. The number of adherent organisms was determined by colony counting, and adherence was expressed as a percentage of the original inoculum.

Animal model.

To determine the role of AAF1 in the virulence of C. albicans, 18- to 20-g male BALB/c mice (Harlan, San Diego, Calif.) were used. The mice were housed five per cage, and food and water were given ad libitum. The aaf1 mutants and the parent strain SC5314 were grown in YPD at 30°C overnight. The organisms were washed with nonpyrogenic Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline solution (Irvine Scientific) and resuspended in this buffer at 2 × 106 organisms per ml. Ten animals per group were inoculated with 0.5 ml of the suspension intravenously via the tail vein. The cages were monitored for dead or moribund mice three times daily. Moribund mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation.

Statistical analysis.

All in vitro experiments were carried out in triplicate, and the experiments were repeated at least two times on different days. The median and the first and third quartiles (interquartile range) were calculated. The data were analyzed by using the Wilcoxon rank sum test and corrected for multiple comparisons with the Bonferroni correction. For correlation among the putative virulence factors, we used Spearman’s rank sum test. A P value of <0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Disruption of one allele of AAF1 results in heterogeneity of phenotypes among the mutants.

Previously, we isolated a clone containing AAF1 from a genomic library from C. albicans 36082 by its ability to enhance the adherence of S. cerevisiae to endothelial cells (6). To construct an aaf1 null mutant, we transformed the ura3-negative C. albicans strain CAI-4 with a construct containing AAF1 from C. albicans 36082 in which a 1.2-kb segment of the coding region of this gene was replaced with hisG::URA3::hisG (Fig. 1). This procedure disrupted one allele of AAF1. Five different transformants (CU1, CU2, CU4, CU5, and CU6) were selected. Their genotypes were confirmed by Southern blot hybridization, which demonstrated the correct insertion of the hisG::URA3::hisG disruption construct into the AAF1 locus (data not shown).

Because our original intention was to determine the role of the AAF1 gene product in adherence, we compared the abilities of these heterozygous null mutants to adhere to endothelial cells. There was significant day-to-day variability in the adherence of these mutants. However, the endothelial cell adherence of the five heterozygous mutants was not consistently different from that of the parent strain, SC5314 (Table 1).

Importantly, there was an unanticipated variability in the growth rates of the five heterozygous null mutants. The median doubling times of these heterozygous null mutants ranged from 1.58 to 1.95 h, significantly longer than that of the parent strain SC5314 (Table 1).

The variability in growth rate was not due to the source of AAF1.

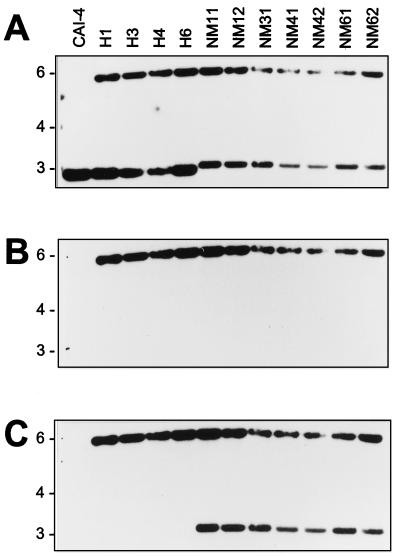

We next explored the possibility that the observed heterogeneity in growth rates among the different heterozygous aaf1 mutants was caused by strain-to-strain differences in the flanking region of AAF1. We therefore used PCR to clone AAF1 and its flanking regions from SC5314, the parent strain of CAI-4, and used this DNA fragment to construct a second disruption cassette. This cassette was then used to transform CAI-4 to produce additional aaf1 mutants. Four different heterozygous null mutants (H1, H3, H4, and H6 [Table 2]) were selected. Southern blotting confirmed that the disruption construct had integrated into the expected location in the genome (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Southern blot analysis of aaf1 mutants of C. albicans (second series). Genomic DNA from the indicated strains of C. albicans was digested with XhoI and then hybridized with a 2.9-kb XhoI fragment encompassing the AAF1 open reading frame and flanking region (A), URA3 (B), and hisG (C). The blot shows the correct insertion of the hisG::URA3::hisG knockout construct into the AAF1 locus in all mutants.

Next, we tested the growth rates of these presumably isogenic mutants. Similar to our findings with the previous heterozygous mutants, the doubling time of the new heterozygous mutants varied from 1.42 to 1.59 h (Table 2). There was a trend toward a lower growth rate in all of the heterozygous mutants compared to SC5314. However, this difference in growth rate achieved statistical significance only in strain H3. These results suggest that the observed variability in growth rates of the heterozygous mutants was not the result of transformation with a disruption cassette that was constructed using a heterologous allele of AAF1.

The transformation procedure did not influence growth heterogeneity of mutants.

Next, we examined the possibilities that either there was intrinsic variability in the growth rate of different clones of CAI-4 or the LiAc-PEG transformation procedure contributed to the differences in growth rates among the mutants. C. albicans CAI-4 was mock transformed by the standard LiAc-PEG technique except that the disruption cassette was omitted. The growth rates were then determined for seven randomly chosen mock-transformed CAI-4 colonies in YPD medium supplemented with 30 μg of uridine per ml. We found that the doubling times of these mock transformants were very similar (range, 1.92 to 2.04 h). These doubling times were also similar to that of CAI-4 that had not undergone the mock transformation procedure (median, 1.97 h; interquartile range, 1.64 to 2.12). These findings suggest that C. albicans CAI-4 has a uniform growth rate and that transformation by the LiAc-PEG method does not result in clonal variability in growth rates.

In these experiments, we also observed that all clones of CAI-4 grew more slowly than the parent strain SC5314, even in the presence of supplemental uridine. The lower growth rate of CAI-4 is almost certainly due to the uridine auxotrophy of this mutant, because when URA3 is reintroduced into CAI-4 (to generate CAI-12), its growth rate is similar to that of SC5314 (Table 1).

Examining the role of URA3 in growth rate heterogeneity.

To investigate whether differences in URA3 activity among the various mutants could contribute to the differences in growth rates, we compared the doubling times of representative fast-growing (CU2) and slow-growing (CU5) heterozygous aaf1 mutants in YPD containing 0, 30, and 60 μg of supplemental uridine per ml. We found that the concentration of uridine in the medium had no effect on the growth rates of the two mutants (data not shown).

We also examined the growth rate of CAI-12, a URA3 revertant strain of CAI-4, to evaluate the effect of URA3 reinserted into the genome. We chose seven colonies of CAI-12 and determined their growth rates. There was no significant difference in their doubling times. Also, these organisms grew at the same rate as did the parent strain, SC5314 (data not shown). Taken together, these results indicate that the heterogeneity in growth rates of the aaf1 null mutants was not the result of variation in the URA3 function.

Characterization of the homozygous aaf1 null mutants.

As our original intent was to determine the role of AAF1 in the adherence of C. albicans to endothelial cells, we constructed homozygous aaf1 null mutants. The first homozygous null mutant was CHU18, which was generated from the heterozygote CU5 by using a disruption cassette constructed with AAF1 from C. albicans 36082. From CHU18, we constructed an AAF1 revertant strain (CHR1) by transforming a ura3 mutant of CHU18 with the linearized pBSK vector containing AAF1 and URA3 (Fig. 1). Southern blotting confirmed that the constructs integrated into the expected sites (data not shown).

All four heterozygous aaf1 null mutants of the second series were used to generate homozygous null mutants as described above, except that the disruption cassette was derived from AAF1 of C. albicans SC5314. The null mutants of this second series were NM11, NM12, NM31, NM41, NM42, NM61, and NM62 (Table 2; Fig. 2).

The levels of endothelial cell adherence of the aaf1 null mutants CHU18, NM12, and NM31 as well as the revertant strain, CHR1, were not statistically different from that of the parent strain SC5314 (Tables 1 and 2). Therefore, we were unable to determine a role for AAF1 in conferring the ability of C. albicans to adhere to endothelial cells under the conditions tested.

There was significant variability in the growth rates of the homozygous null mutants, and the growth rates of these mutants were not always similar to those of the heterozygotes from which they were derived. For example, the doubling time of CU5, the aaf1 heterozygote, was significantly longer than that of SC5314. However, the doubling time of CHU18, the aaf1 homozygote derived from CU5, was intermediate to those of CU5 and SC5314 (Table 1). Conversely, the doubling time of H4, another aaf1 heterozygote, was not significantly longer than that of SC5314. In contrast, the doubling times of NM41 and NM42, the homozygous aaf1 mutants generated from H4, were significantly longer than that of SC5314 (Table 2).

To determine the virulence of the different null mutants, we examined the survival time of mice challenged with mutants constructed in the first knockout series compared to the parent strain SC5314. The survival studies revealed heterogeneous results as well. Mice infected with either C. albicans SC5314 or the AAF1 revertant strain CHR1 had similar survival times (Table 1). The survival time of mice infected with the heterozygous strains varied from 5 to >16 days. Finally, the homozygous aaf1 null mutant, CHU18, was significantly less virulent than the parent strain but more virulent than some of the aaf1 heterozygotes. Therefore, the virulence of the different mutants was unrelated to the number of functional copies of AAF1 that they contained.

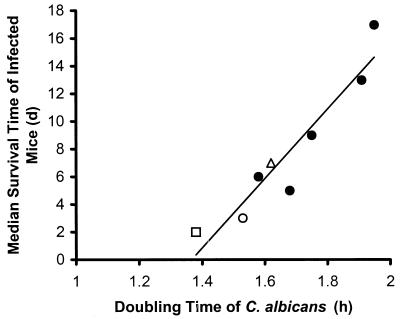

The factor most strongly associated with the virulence of these different strains was their growth rate. AAF1 heterozygotes that grew slowly were much less virulent than heterozygotes that grew rapidly (Table 1). There was a linear relationship between the doubling time of the mutants and the median survival time of the mice infected with the different mutants (r = 0.87; P = 0.014) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Relationship between the doubling times of the strains listed in Table 1 and the median survival time of mice infected with these strains. Symbols: open square, SC5314; closed circles, aaf1 heterozygotes; open triangle, aaf1 homozygote; open circle, AAF1 revertant. d, days.

DISCUSSION

In previous studies, where we expressed AAF1 in S. cerevisiae, we determined that this gene likely encodes a regulatory factor (6). To establish a possible function of AAF1 in C. albicans, multiple heterozygous and homozygous aaf1 null mutants were constructed. Although these null mutants exhibited variable phenotypes in terms of growth rate and virulence, their adherence to endothelial cells was consistently similar to that of the parent strain, SC5314. These results suggest that either AAF1 does not regulate endothelial cell adherence in C. albicans or compensatory adherence mechanisms in C. albicans are up-regulated when AAF1 is disrupted.

The characteristics that varied among the heterozygous and homozygous aaf1 null mutants included their doubling times in vitro and their virulence in the mouse model. This phenotypic variability made it extremely difficult to determine the contribution of AAF1 to the virulence of C. albicans in vivo. Furthermore, if only one disruptant had been characterized, then potentially erroneous conclusions would likely have been drawn. These findings suggest that when gene disruption is used to determine the contribution of a given gene product to in vivo virulence, more than one series of mutants should be made, and multiple characteristics of these organisms, especially growth rate, should be evaluated.

One possible explanation for the phenotypic heterogeneity that we observed is that during the disruption process, mutations were introduced into the regions of the genome flanking AAF1. Even though Southern blotting indicated that the deletion constructs all integrated into the same region of the genome, this procedure would not be expected to detect small mutations that could have been introduced into the regions of the genome flanking AAF1 by the disruption process. It is possible that these flanking regions are unusually unstable or contain a gene or regulatory sequence that is critical for the normal growth and virulence of C. albicans.

Our experiments aimed at determining possible mechanisms by which one or more mutations in the AAF1 flanking region could have been introduced ruled out two possibilities. The first possibility investigated was that a mutation in the AAF1 flanking regions was introduced by the heterologous allele of AAF1 contained within the disruption cassette used to construct the first set of null mutants. These mutants were derived from C. albicans SC5314, and AAF1 was disrupted by using a cassette that contained an allele from C. albicans 36082. We therefore constructed a second set of null mutants in which the disruption cassette was constructed by using homologous DNA from C. albicans SC5314. The variability in growth rate of this second set of null mutants was similar to that of the first set. These results suggest that any strain-dependent differences in AAF1 or its flanking regions in the disruption cassette were not the main cause of the observed variability in phenotypes.

The second possibility examined was that the LiAc-PEG transformation procedure alone contributed to the phenotypic variability. We found that clones of CAI-4 that were subjected to the transformation procedure in the absence of the disruption cassette all had similar growth rates. This finding also indicates that under normal circumstances, there is little clone-to-clone variability in growth rate of C. albicans.

The possibility that differences in the activity of the URA3 gene product contributed to the growth heterogeneity of the mutants was also excluded by our finding that varying the concentration of uridine in the medium had no effect on the growth rate of the mutants.

To our knowledge, this phenotypic variability in the growth rate and virulence of null mutants of C. albicans has not been reported previously. For example, when Bulawa et al. (4) examined the role of the gene encoding chitin synthase 3 (CHS3) in the virulence of C. albicans, several heterozygous and homozygous null mutants were constructed and characterized. The different mutants had no obvious alterations in growth rates, sugar assimilation, or chlamydospore formation. However, most other studies of C. albicans null mutants have reported only the characteristics of one null mutant; whether multiple mutants were evaluated in these studies is not clear (1, 10, 11, 14). Nevertheless, our results concerning the heterogeneity of supposedly isogenic mutants should be considered when other null mutants are being constructed.

Of the characteristics of the aaf1 null mutants that were evaluated, the doubling time in vitro correlated most closely with virulence in vivo. However, even a 14% increase in doubling time, while not statistically significant, was associated with a marked reduction in mortality when mice were infected with the slower-growing organism. This finding suggests that for characterization of null mutants of C. albicans, determining the doubling time of the mutants may be a method to screen for the introduction of some unexpected mutations. The growth rate of any mutant should be very similar to that of the parent strain, because even a relatively minor difference in doubling time may significantly reduce the virulence of the organism in the standard murine model of hematogenously disseminated candidiasis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank William Fonzi for helpful advice and discussion, the Perinatal nurses at the Harbor-UCLA and Torrance Memorial Medical Centers for collecting umbilical cords, and Alison Orozco for helping with tissue culture.

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants AI19990, AI37194, AI040636, and RR00425 from the National Institutes of Health. A.S.I. is supported by a fellowship (1099-FI2) from the American Heart Association, Greater Los Angeles Affiliate.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey D A, Feldmann P J F, Bovey M, Gow N A R, Brown A J. The Candida albicans HYR1 gene, which is activated in response to hyphal development, belongs to a gene family encoding yeast cell wall proteins. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:5353–5360. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.18.5353-5360.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barki M, Koltin Y, Yanko M, Tamarkin A, Rosenberg M. Isolation of a Candida albicans DNA sequence conferring adhesion and aggregation on Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5683–5689. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5683-5689.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boeke J D, LaCroute F, Fink G R. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;197:345–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00330984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bulawa C E, Miller D W, Henry L K, Becker J M. Attenuated virulence of chitin-deficient mutants of Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10570–10574. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fonzi W A, Irwin M Y. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics. 1993;134:717–728. doi: 10.1093/genetics/134.3.717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fu Y, Filler S G, Spellberg B J, Fonzi W A, Ibrahim A S, Kanbe T, Ghannoum M A, Edwards J E., Jr Cloning and characterization of CAD1/AAF1, a gene that induces adherence to endothelium when expressed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2078–2084. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2078-2084.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghannoum M A, Filler S G, Ibrahim A S, Fu Y, Edwards J E., Jr Modulations of interactions of Candida albicans and endothelial cells by fluconazole and amphotericin B. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2239–2244. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gietz R D, Schiestl R H. High efficiency transformation of intact yeast cells using single stranded nucleic acids as a carrier. Curr Genet. 1989;16:339–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00340712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gillum A M, Tsay E Y H, Kirsch D R. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E.coli pyrF mutations. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;198:179–182. doi: 10.1007/BF00328721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gow N A R, Robbins P W, Lester J W, Brown A J P, Fonzi W A, Chapman T, Kinsman O S. A hyphal-specific chitin synthase gene (CHS2) is not essential for growth, dimorphism, or virulence of Candida albicans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6216–6220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.6216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hube B, Sanglard D, Odds F C, Hess D, Monod M, Schäfer W, Brown A J P, Gow N A R. Disruption of each of the secreted aspartyl proteinase genes SAP1, SAP2, and SAP3 of Candida albicans attenuates virulence. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3529–3538. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3529-3538.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibrahim A S, Mirbod F, Filler S G, Banno Y, Cole G T, Kitajima Y, Edwards J E, Jr, Nozawa Y, Ghannoum M A. Evidence implicating phospholipase as a virulence factor in Candida albicans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1993–1998. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.5.1993-1998.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffe E A, Nachman R L, Becker C G, Ninick C R. Culture of human endothelial cells derived from umbilical veins: identification by morphologic and immunologic criteria. J Clin Investig. 1973;52:2745–2756. doi: 10.1172/JCI107470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo H-J, Köhler J R, DiDomenico B, Loebenberg D, Cacciapuoti A, Fink G R. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell. 1997;90:939–949. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80358-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pla J, Gil C, Moteoliva L, Navarro-Garcia F, Sanchez M, Nombela C. Understanding Candida albicans at the molecular level. Yeast. 1996;12:1677–1702. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(199612)12:16%3C1677::AID-YEA79%3E3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sanglard D, Hube B, Monod M, Odds F C, Gow N A R. A triple deletion of the secreted aspartyl proteinase genes SAP4, SAP5, and SAP6 of Candida albicans causes attenuated virulence. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3539–3546. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3539-3546.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Willett H P. Physiology of bacterial growth. In: Joklik W K, Willett H P, Amos D B, editors. Zinsser microbiology. 17th ed. New York, N.Y: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1980. p. 88. [Google Scholar]