Abstract

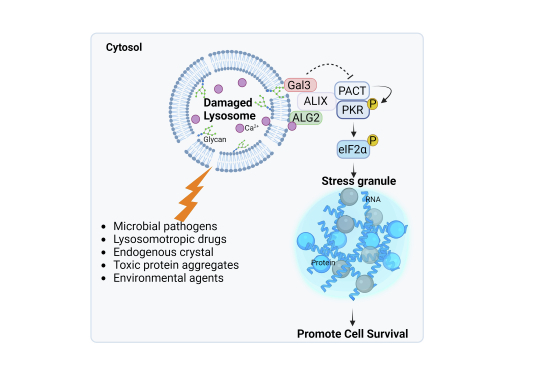

Lysosomal damage induces stress granule (SG) formation. However, the importance of SGs in determining cell fate and the precise mechanisms that mediate SG formation in response to lysosomal damage remain unclear. Here, we describe a novel calcium-dependent pathway controlling SG formation, which promotes cell survival during lysosomal damage. Mechanistically, the calcium-activated protein ALIX transduces lysosomal damage signals to SG formation by controlling eIF2α phosphorylation after sensing calcium leakage. ALIX enhances eIF2α phosphorylation by promoting the association between PKR and its activator PACT, with galectin-3 inhibiting this interaction; these regulatory events occur on damaged lysosomes. We further find that SG formation plays a crucial role in promoting cell survival upon lysosomal damage caused by factors such as SARS-CoV-2ORF3a, adenovirus, malarial pigment, proteopathic tau, or environmental hazards. Collectively, these data provide insights into the mechanism of SG formation upon lysosomal damage and implicate it in diseases associated with damaged lysosomes and SGs.

Keywords: Lysosomal Damage, Stress Granules, Calcium-dependent Pathway, ALG2-ALIX, PACT-PKR-eIF2α

Subject terms: Microbiology, Virology & Host Pathogen Interaction; Organelles

Synopsis

Stress granules (SGs) form in response to diverse environmental signals. Here, the signaling pathways that connect lysosomal stress to SG formation are characterized.

A calcium-dependent pathway initiates SG formation in response to lysosomal damage.

ALIX, a sensor of calcium release from damaged lysosomes, controls the initial stages of SG formation, particularly eIF2α phosphorylation.

Modulation of eIF2α phosphorylation involves opposing effects of ALIX and galectin-3 on PKR-PACT association.

SG formation promotes cell survival upon lysosomal damage induced by various endogenous, viral, or environmental factors.

Lysosome damage is a critical internal physiological trigger for stress granule formation.

Introduction

Lysosomes are acidic hydrolase-rich membrane-bound organelles that play a vital role in cellular degradation and signaling (Ballabio and Bonifacino, 2020; Lamming et al, 2019; Lawrence and Zoncu, 2019; Yang et al, 2021). Damage to lysosomes can be triggered by numerous physiological and pathological conditions (Nakamura et al, 2021; Papadopoulos et al, 2017; Yang and Tan, 2023). These include microbial pathogens (Ghosh et al, 2020; Montespan et al, 2017; Thurston et al, 2012), environmental pollutants (Hornung et al, 2008; Mossman and Churg, 1998; J. Wang et al, 2017), toxic protein aggregates (Flavin et al, 2017; Papadopoulos et al, 2017), endogenous crystals (Hui et al, 2012; Maejima et al, 2013), and many lysosomotropic drugs (Marceau et al, 2012; Pisonero-Vaquero and Medina, 2017). These agents, along with various others, damage lysosomes, leading to the leakage of acidic contents and the disruption of cellular functions, thereby threatening cell survival (Patra et al, 2023; Saftig and Puertollano, 2021; Wang et al, 2018). Lysosomal damage is strongly linked to various human diseases, e.g., cancer, infectious, and neurodegenerative diseases (Amaral et al, 2023; Ballabio and Bonifacino, 2020; Bonam et al, 2019; Fehrenbacher et al, 2005). Although lysosomal damage is of physiological importance and pathological relevance, understanding of how cells respond to this damage remains largely unknown (Papadopoulos and Meyer, 2017).

Cells can detect lysosomal damage through several mechanisms, including the identification of calcium leakage or the exposure of luminal glycan (Aits et al, 2015; Radulovic et al, 2018; Skowyra et al, 2018). Minorly damaged lysosomes can be repaired through multiple cellular systems, including annexins (Ebstrup et al, 2023; Yim et al, 2022), sphingomyelin turnover (Niekamp et al, 2022), microautophagy (Ogura et al, 2023), ER-lysosome lipid transfer (Radulovic et al, 2022; Tan and Finkel, 2022) as well as ESCRT (the endosomal sorting complexes required for transport) machinery (Radulovic et al, 2018; Skowyra et al, 2018). Notably, the protein ALIX (ALG-2-Interacting Protein X), a key ESCRT component, can detect lysosomal damage by sensing calcium release, a function it performs alongside its partner, ALG2 (Apoptosis-Linked Gene-2) (Chen et al, 2024; Maki et al, 2016; Sun et al, 2015). Upon detecting such damage, ALIX facilitates the recruitment of other ESCRT components to the site of damage for repair (Chen et al, 2024; Radulovic et al, 2018; Skowyra et al, 2018). Severely damaged lysosomes can be removed by selective autophagy (Chauhan et al, 2016; Maejima et al, 2013), noncanonical autophagy (Boyle et al, 2023; Kaur et al, 2023), or lysosomal exocytosis (Domingues et al, 2024; Wang et al, 2023). Master regulators mTORC1 (mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1) and AMPK (AMP-activated protein kinase), located on lysosomes (Sancak et al, 2010; Zhang et al, 2014), are finely tuned to respond to lysosomal damage, subsequently activating downstream processes e.g., autophagy and lysosomal biogenesis (Jia et al, 2018; Jia et al, 2020a, 2020b; Jia et al, 2020c). These mechanisms collectively safeguard lysosomal quality, maintaining cellular homeostasis (Jia et al, 2020d).

Recently, we reported that lysosomal damage induces the formation of stress granules (SGs) (Jia et al, 2022; Jia et al, 2023). SGs are membrane-less organelles identified as ribonucleoprotein condensates that are believed to serve as protective responses in cells under adverse conditions (Ivanov et al, 2019; McCormick and Khaperskyy, 2017; Riggs et al, 2020). Consequently, dysfunctional SGs have been implicated in various human diseases e.g., neurodegenerative and infectious diseases(Advani and Ivanov, 2020; Protter and Parker, 2016; Wang et al, 2020). SG formation is triggered by specific kinases, such as PKR (Protein Kinase R), that sense various stress stimuli, leading to the phosphorylation of eIF2α (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2) (Kedersha et al, 1999; Srivastava et al, 1998). Phosphorylated eIF2α (p-eIF2α) halts global translation, resulting in the accumulation of untranslated mRNA (Jackson et al, 2010). Simultaneously, it promotes the selective expression of stress response proteins, a process known as the integrated stress response (Costa-Mattioli and Walter, 2020; Pakos-Zebrucka et al, 2016). SG formation can also occur through mTORC1-mediated translational shutdown, independent of p-eIF2α (Emara et al, 2012; Fujimura et al, 2012; McCormick and Khaperskyy, 2017). RNA-binding proteins G3BP1/2 (GAP SH3 Domain-Binding Protein 1/2) detect untranslated mRNA and collectively initiate SG formation through an RNA-protein network, driven by liquid-liquid phase separation (Hyman et al, 2014; Ivanov et al, 2019).

Despite the extensive knowledge of SG composition and dynamics, an understanding of the functional consequences of SG formation remains limited (Riggs et al, 2020). SG formation has often been investigated under non-physiological conditions such as arsenic stress or heat shock (Jain et al, 2016; Sidrauski et al, 2015; Turakhiya et al, 2018; Verma et al, 2021; Yang et al, 2020). Notably, our study (Jia et al, 2022) which originally revealed lysosomal damage as a critical internal physiological trigger for SGs, underscores the need to better understand the nature of SG formation in disease contexts. In addition, this new connection between damaged lysosomes and SGs provides a novel perspective on the interaction between membrane-bound and membrane-less organelles (Zhao and Zhang, 2020). For example, recent research suggests that SGs have the ability to plug and stabilize damaged lysosomes (Bussi et al, 2023). However, the precise regulation of SG formation in response to lysosomal damage and its consequential impact on cell fate remains largely unexplored.

In this study, we employed unbiased approaches to investigate how lysosomal damage signals are transduced to induce SG formation and to elucidate the cytoprotective role of SG formation in promoting cell survival against lysosomal damage. Our findings revealed a novel function of ALIX, which senses calcium release from damaged lysosomes, in controlling the phosphorylation of eIF2α through PKR and its activator on damaged lysosomes, thereby initiating SG formation. This process is critical for cell survival in response to lysosomal damage caused by microbiological, pathological, and environmental agents including SARS-CoV-2ORF3a, adenovirus, Malaria hemozoin, proteopathic tau and silica. In conclusion, our study uncovers a calcium-dependent signaling mechanism that transmits lysosomal damage signals to induce SG formation and reveals the cytoprotective role of SG formation in response to lysosomal damage caused by diverse stresses.

Results

Stress granule formation promotes cell survival in response to lysosomal damage

How does SG formation affect cell fate during lysosomal damage? We utilized SG deficient U2OS cells (human osteosarcoma epithelial cell line) genetically lacking both G3BP1 and G3BP2 (ΔΔG3BP1/2) (Kedersha et al, 2016), which are essential factors for SG formation (Guillén-Boixet et al, 2020; Kedersha et al, 2016; Yang et al, 2020) (Fig. EV1A). We quantified the number of SGs using the canonical SG marker polyA RNA (Ivanov et al, 2019) via high-content microscopy (HCM) and verified the depletion of SG formation in ΔΔG3BP1/2 cells when exposed to the lysosome-specific damaging agent L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester (LLOMe) (Jia et al, 2022; Tan and Finkel, 2022; Thiele and Lipsky, 1990) (Fig. EV1B(i)). We also found that depleting G3BP1 and G3BP2 does not impact lysosomal biogenesis, as indicated by the expression and puncta formation of the lysosomal integrated protein LAMP2 (Figs. EV1A, 1B(ii)). A propidium iodide (PI) uptake assay measuring plasma membrane integrity (Crowley et al, 2016; Liu et al, 2023) was adapted to quantify cell survival during lysosomal damage using HCM. We found significant cell death upon LLOMe treatment in ΔΔG3BP1/2 cells compared to wild type (WT) U2OS cells (Fig. 1A). This was additionally confirmed by using a lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay measuring non-specific leak from cells (Chan et al, 2013; Kumar et al, 2018) (Fig. 1B). Further, we pharmacologically blocked SG assembly through the use of cycloheximide which freezes ribosomes on translating mRNAs and reduces the accumulation of free untranslated mRNA (Freibaum et al, 2021; Kedersha et al, 2000). Consistent with previous reports (Bussi et al, 2023; Jia et al, 2022), cycloheximide treatment inhibited SG formation in U2OS cells, as evidenced by the absence of G3BP1 puncta following LLOMe treatment (Fig. EV1C). This suppression of SG formation led to reduced cell survival, as indicated by increased LDH release in the face of lysosomal damage (Fig. EV1D). Previously we reported that LLOMe treatment induced phosphorylation of eIF2α (Jia et al, 2022), a critical signal for SG formation (Ivanov et al, 2019; Kedersha et al, 2000). The small molecule ISRIB (integrated stress response inhibitor) can also act as an SG inhibitor, effectively counteracting the downstream effects of eIF2α phosphorylation, such as ATF4 (Activating transcription factor 4) expression (Rabouw et al, 2019; Sidrauski et al, 2015). We prevented SG formation using ISRIB upon lysosomal damage (Fig. EV1E) and observed a corresponding reduction in ATF4 expression levels in THP-1 cells (the human monocytic cell line) (Fig. EV1F). The prevention of SG formation by ISRIB also caused a decrease in cell survival in THP-1 cells (Fig. EV1G). Furthermore, the cell death effect during lysosomal damage caused by the loss of SG formation can be rescued. This is evidenced by the reduced cell death, as measured by the PI uptake assay, when G3BP1 and G3BP2 were overexpressed in ΔΔG3BP1/2 cells (Fig. EV1H).

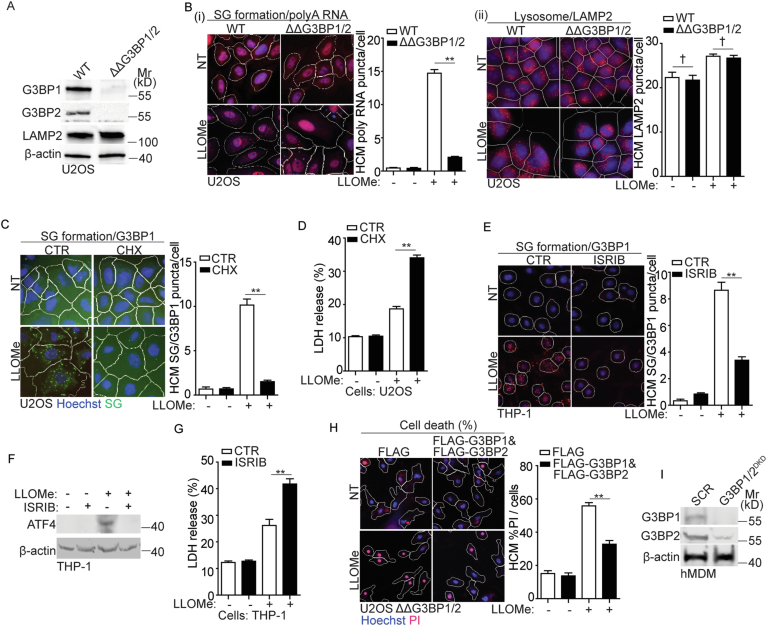

Figure EV1. Stress granule formation is important for cell survival during lysosomal damage.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of G3BP1 and G3BP2 in U2OS WT and ΔΔG3BP1/2 cells. (B) Quantification by high-content microscopy (HCM) of polyA RNA (Cy3-oligo[dT]) by FISH (i) and LAMP2 (ii) in U2OS WT and ΔΔG3BP1/2 cells. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries (primary objects); red masks, computer-identified polyA RNA or LAMP2 puncta respectively (target objects). (C) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (D) Cell death analysis of supernatants of U2OS cells by a LDH release assay. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml CHX for 30 min. (E) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in human monocytic THP-1 cells. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe in the presence or absence of 200 nM ISRIB for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (F) Immunoblot analysis of ATF4 in THP-1 cells treated with 1 mM LLOMe in the presence or absence of 200 nM ISRIB for 30 min. (G) Cell death analysis of supernatants of THP-1 cells by a LDH release assay. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe in the presence or absence of 200 nM ISRIB for 30 min. (H) Quantification of cell death by HCM using a propidium iodide (PI) uptake assay in U2OS G3BP1&2 double knockout (ΔΔG3BP1/2) cells overexpressing either FLAG or FLAG-G3BP1 & FLAG-G3BP2. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min, and then stained with propidium iodide (PI) (dead cells) and Hoechst-33342 (total cells). White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified PI+ nuclei. (I) Immunoblot analysis of the protein level of G3BP1 and G3BP2 in hMDM transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or G3BP1 and G3BP2 siRNA for double knockdown (DKD). CTR, control; NT, untreated cells. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Fig. 1.

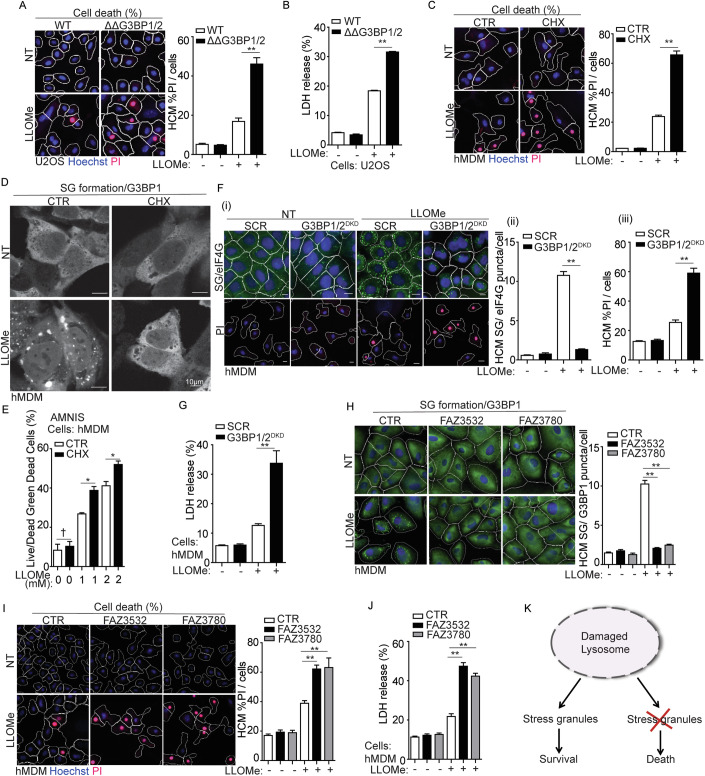

Figure 1. Stress granule formation promotes cell survival in response to lysosomal damage.

(A) Quantification by high-content microscopy (HCM) of cell death by a propidium iodide (PI) uptake assay in U2OS wild type (WT) and G3BP1&2 double knockout (ΔΔG3BP1/2) cells. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min, and then stained with propidium iodide (PI) (dead cells) and Hoechst-33342 (total cells). White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries (primary objects); red masks, computer-identified PI+ nuclei (target objects). (B) Cell death analysis of supernatants of U2OS WT and ΔΔG3BP1/2 cells by a LDH release assay. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. (C) Quantification by HCM of cell death by a PI uptake assay in human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDM). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe in the presence or absence of 10 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) for 30 min, and then stained with PI (dead cells) and Hoechst-33342 (total cells). (D) Confocal microscopy analysis of G3BP1 (Alexa Fluor 488) in hMDM treated with 2 mM LLOMe with or without CHX for 30 min. Scale bar, 10 μm. (E) Quantification using AMNIS of cell death by Live/DeadTM stain kit in hMDM. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe with or without CHX for 30 min, and then stained using Live/DeadTM stain kit (ThermoFisher). (F) Quantification by HCM of cell death by a PI uptake assay and SG formation by eIF4G in hMDM transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or G3BP1 and G3BP2 siRNA for double knockdown (DKD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min, and then stained with PI (dead cells), Hoechst-33342 (total cells) or eIF4G. (i) HCM images: white masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified eIF4G puncta; red masks, computer-identified PI+ nuclei (target objects); (ii and iii) corresponding HCM quantification. Scale bar, 10 μm. (G) Cell death analysis of supernatants of hMDM transfected with either scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or G3BP1 and G3BP2 siRNA for double knockdown (DKD) using a LDH release assay. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. (H) Quantification by HCM of SG formation by G3BP1 in hMDM treated with 20 µM FAZ3532 or 20 µM FAZ3780 for 20 min, followed by exposure to 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Control cells were treated with DMSO. Green masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (I) Quantification by HCM of cell death by a PI uptake assay in hMDM treated with 20 µM FAZ3532 or 20 µM FAZ3780 for 20 min, followed by exposure to 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Control cells were treated with DMSO. Red masks, computer-identified PI+ nuclei. (J) Cell death analysis of supernatants of hMDM treated with 20 µM FAZ3532 or 20 µM FAZ3780 for 20 min, followed by exposure to 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min using a LDH release assay. Control cells were treated with DMSO. (K) Schematic summary of the findings in Fig. 1 and EV1. CTR, control; NT, untreated cells. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Fig. EV1. Source data are available online for this figure.

The protective effects of SG formation in response to lysosomal damage were also observed in primary cells using human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDM). This includes that the significant increase in cell death during LLOMe treatment, as quantified by the PI uptake assay when SG formation was inhibited by cycloheximide in hMDM (Fig. 1C,D). This was further confirmed by measuring the viability of live hMDM (without the fixation) using an AMNIS imaging flow cytometer (Fig. 1E). Knockdown of both G3BP1 and G3BP2 in hMDM (G3BP1/2DKD) resulted in a reduction of SG formation as evaluated by a key SG marker, eIF4G puncta, during LLOMe treatment (Figs. 1F (i, ii) and EV1I). Elevated cell death, as quantified by PI uptake assay (Fig. 1F (i, iii)) and the LDH release assay (Fig. 1G), was detected in G3BP1/2DKD in response to LLOMe treatment.

To further validate the protective role of SG formation during lysosomal damage, we employed G3BP small-molecule inhibitors FAZ3532 and FAZ3780. These inhibitors bind to the dimerization domain of G3BP1/2, specifically disrupting the co-condensation of RNA, G3BP and SG network (Freibaum et al, 2024). First, we treated hMDM with these inhibitors and observed that they effectively inhibited SG formation induced by LLOMe individually (Fig. 1H). In addition, we found that FAZ3532/FAZ3780-induced SG deficiency significantly increased cell death upon lysosomal damage, as demonstrated by PI uptake assay (Fig. 1I) and LDH release assay (Fig. 1J). These data emphasize that SG assembly itself is necessary for cell survival during lysosomal damage. In summary, SG formation is a cytoprotective response to lysosomal damage (Fig. 1K).

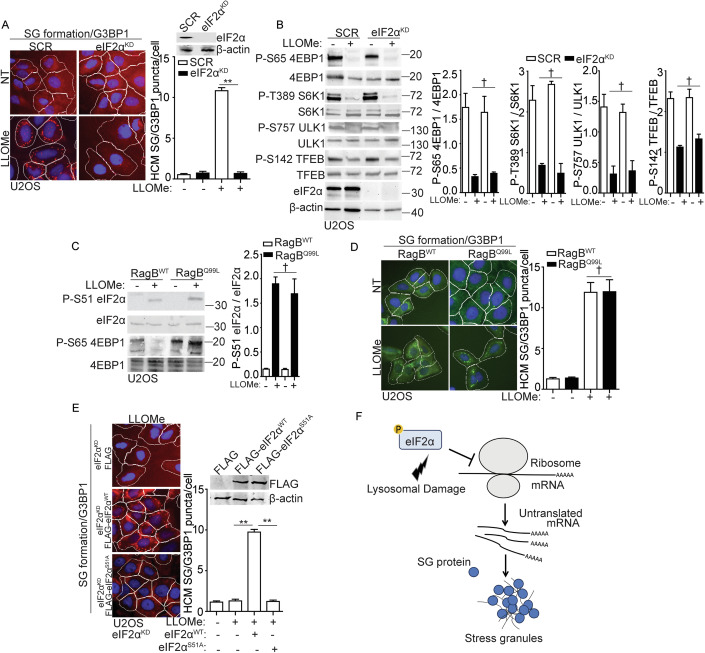

Stress granule formation is controlled by eIF2α pathway but not mTORC1 pathway during lysosomal damage

Considering the significance of SG formation during lysosomal damage, what mechanisms regulate SG formation in response to such damage? SG formation occurs as a consequence of protein translation arrest during cellular stress (Riggs et al, 2020; Youn et al, 2019). eIF2α phosphorylation and mTORC1 inactivation are two key upstream events that lead to protein translation arrest and subsequently trigger SG formation (Cotto and Morimoto, 1999; Emara et al, 2012; McCormick and Khaperskyy, 2017). Consistent with our earlier studies (Jia et al, 2018; Jia et al, 2022), we confirmed that LLOMe treatment induced eIF2α phosphorylation and mTORC1 inactivation (as assessed by the decreased phosphorylation of its substrates: 4EBP1 (Ser65), S6K (Thr389), ULK1 (Ser757), and TFEB (Ser142)), in a dose-dependent manner in U2OS cells (Fig. EV2A). To investigate the role of eIF2α and mTORC1 pathways in regulating SG formation upon lysosomal damage, we initially knocked down eIF2α in U2OS cells (eIF2αKD) (Fig. 2A). This revealed that eIF2α is necessary for SG formation upon lysosomal damage, which was reflected by the depletion of SG formation in eIF2αKD cells during LLOMe treatment (Fig. 2A). In addition, mTORC1 activity in eIF2αKD cells was examined by detecting the phosphorylation of its substrates 4EBP1 (Ser65), S6K (Thr389), ULK1 (Ser757) and TFEB (Ser142), revealing that mTORC1 inactivation was not affected by eIF2α depletion upon lysosomal damage (Fig. 2B). This indicates that eIF2α phosphorylation and mTORC1 inactivation are two uncoupled events during lysosomal damage. This was further confirmed by the lack of change in eIF2α phosphorylation upon lysosomal damage in cells expressing constitutively active RagBQ99L, which keeps mTORC1 in an active state (Abu-Remaileh et al, 2017; Sancak et al, 2010) (Fig. 2C). In addition, SG formation was not affected in cells expressing RagBQ99L in response to lysosomal damage (Fig. 2D). This uncoupled relationship between eIF2α phosphorylation and mTORC1 inactivation in SG formation is also reflected in various cellular stress conditions, including amino acid starvation and arsenic stress (Fig. EV2B,C). We found that amino acid starvation resulted in mTORC1 inactivation (assessed by mTOR dissociation from the lysosomes (Abu-Remaileh et al, 2017; Jia et al, 2022) but not eIF2α phosphorylation or SG formation as in previous reports (Prentzell et al, 2021; Wang and Proud, 2008) (Fig. EV2B,C). In contrast, arsenic stress led to eIF2α phosphorylation and SG formation while activating mTORC1 activity, consistent with earlier studies (Chen and Costa, 2018; Prentzell et al, 2021; Thedieck et al, 2013) (Fig. EV2B,C). The key role of eIF2α phosphorylation in SG formation during lysosomal damage was further demonstrated by the ability to complement eIF2α WT but not its phosphorylation site mutant (eIF2α S51A) (Kedersha et al, 1999) in eIF2αKD cells to restore SG formation (Fig. 2E). In summary, eIF2α phosphorylation is a major upstream event for SG formation in response to lysosomal damage (Fig. 2F).

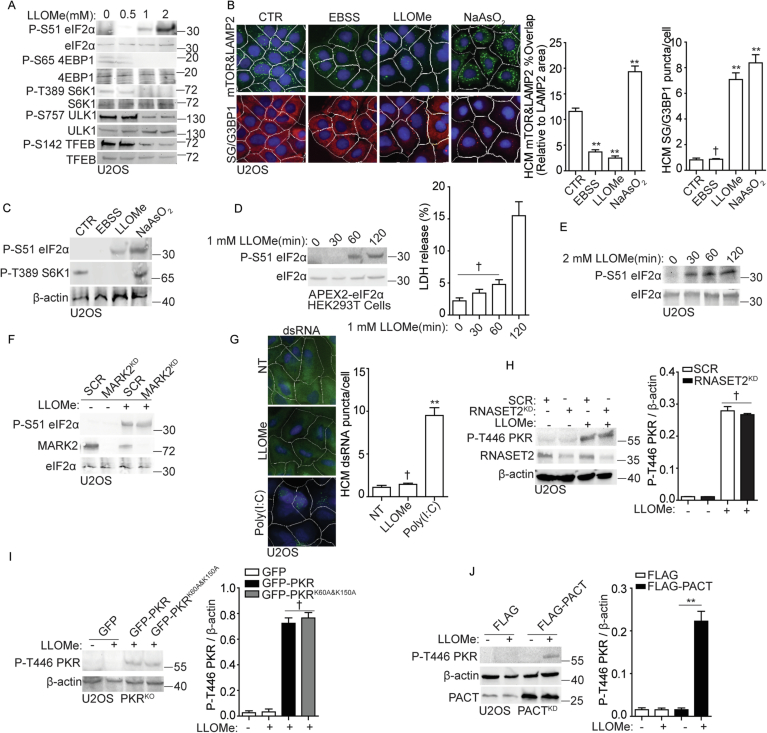

Figure EV2. PACT-PKR- eIF2α pathway controls stress granule formation in response to lysosomal damage.

(A) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51), 4EBP1 (Ser65), S6K (Thr389), ULK1 (Ser757) and TFEB (Ser142) in U2OS cells treated with the indicated dose of LLOMe for 30 min. (B) Quantification by HCM of overlaps between mTOR and LAMP2 or G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells. Cells were treated with EBSS, 2 mM LLOMe or 100 µM NaAsO2 for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified overlap between mTOR and LAMP2; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (C) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and S6K1 (T389) in U2OS cells treated as in (B). (D) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and cell death analysis by a LDH release assay in HEK293T cells expressing APEX2-eIF2α. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for the indicated durations. (E) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS cells. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for the indicated durations. (F) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or MARK2 siRNA for knockdown (MARK2KD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. (G) Quantification by HCM of dsRNA puncta in U2OS cells. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe or 100 ng/mL Poly (I:C) for 30 min. Green masks, computer-identified dsRNA puncta. (H) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of PKR (T446) in U2OS cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or RNASET2 siRNA for knockdown (RNASET2KD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. The level of phosphorylation of PKR (T446) was quantified based on three independent experiments. (I) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of PKR (T446) in PKRKO U2OS G3BP1-GFP cells, overexpressing GFP, GFP-PKR and GFP-PKRK60A&K150A. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. The level of phosphorylation of PKR (T446) was quantified based on three independent experiments. (J) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of PKR (T446) in U2OS PACT knockdown cells (PACTKD) overexpressing FLAG or FLAG-PACT. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. The level of phosphorylation of PKR (T446) was quantified based on three independent experiments. CTR, control. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Figs. 2 and 3.

Figure 2. Stress granule formation is controlled by eIF2α pathway but not mTORC1 pathway during lysosomal damage.

(A) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or eIF2α siRNA for knockdown (eIF2αKD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (B) Immunoblot analysis of mTORC1 activity by phosphorylation of 4EBP1 (Ser65), S6K (Thr389), ULK1 (Ser757), and TFEB (Ser142) in U2OS cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or eIF2α siRNA for knockdown (eIF2αKD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Quantification is based on three independent experiments. (C) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS cells overexpressing wild-type RagB (RagBWT) or constitutively active RagB mutant (RagBQ99L) treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Quantification is based on three independent experiments. (D) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells overexpressing wild-type RagB (RagBWT) or constitutively active RagB mutant (RagBQ99L). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (E) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in eIF2α knockdown (eIF2αKD) U2OS cells transfected with FLAG, FLAG- eIF2αWT or FLAG- eIF2αS51A. Cells were treated with 2 Mm LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (F) Schematic summary of the findings in Figs. 2 and EV2. NT, untreated cells. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Fig. EV2. Source data are available online for this figure.

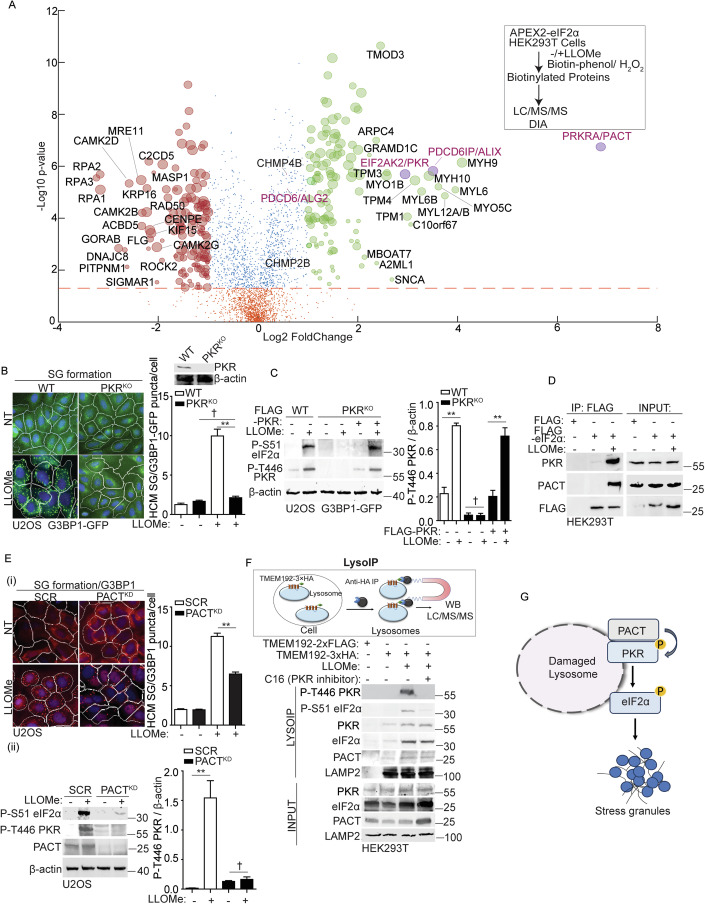

Proteomics proximity analysis of eIF2α upon lysosomal damage reveals that its phosphorylation is driven by PKR and PACT

To further investigate the mechanisms that trigger eIF2α phosphorylation in response to lysosomal damage, we conducted a dynamic proteomic analysis using proximity biotinylation with APEX2-eIF2α fusion. First, we tested the kinetics of eIF2α phosphorylation upon LLOMe treatment in HEK293T cells expressing APEX2-eIF2α. We found that a 1 mM LLOMe treatment for 1 h initiated eIF2α phosphorylation in these cells without triggering cell death (Fig. EV2D). In contrast, treatment with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min in U2OS cells initiated both eIF2α phosphorylation (Fig. EV2E) and the onset of cell death (Fig. 1A,B). Next, we identified and compared the interacting partners of eIF2α through LC/MS/MS in HEK293T cells expressing APEX2-eIF2α, under both control and 1 mM LLOMe 1 h treatment conditions (for a total of three independent experiments) to capture the early events of eIF2α phosphorylation (Dataset EV1). The volcano plot of this proteomic analysis showed dynamic changes in the proximity of cellular proteins to APEX2-eIF2α during lysosomal damage (Fig. 3A). Within the top twenty candidates showing increased association with eIF2α in response to lysosomal damage, we found the expected candidate PKR (EIF2AK2), which was previously reported by our group as a potential upstream kinase responsible for eIF2α phosphorylation during lysosomal damage (Jia et al, 2022) (Fig. 3A). Previously we knocked down four widely recognized upstream kinases of eIF2α (HRI, PKR, PERK, and GCN2) (Pakos-Zebrucka et al, 2016), and found that only the knockdown of PKR resulted in the inhibition of eIF2α phosphorylation and SG formation (Jia et al, 2022). Recently, MARK2 was identified as the fifth kinase responsible for eIF2α phosphorylation in response to proteotoxic stress (Lu et al, 2021). However, we found that MARK2 did not regulate eIF2α phosphorylation during lysosomal damage (Fig. EV2F). To confirm these findings, we generated a CRISPR knockout of PKR (PKRKO) in SG reporter cells (U2OS G3BP1-GFP). In these PKRKO cells, the formation of SG induced by lysosomal damage was completely inhibited, as quantified by the puncta of G3BP1-GFP using HCM (Fig. 3B). In line with this, the phosphorylation of eIF2α and PKR was also abolished (Fig. 3C). Conversely, the overexpression of PKR in PKRKO cells led to a restoration of phosphorylation of eIF2α and PKR during lysosomal damage (Fig. 3C). It is known that PKR can be activated by double-stranded (ds) RNA or protein activator such as PACT (PRKRA) (Gal-Ben-Ari et al, 2019; Patel and Sen, 1998; Peters et al, 2001). First, we tested if dsRNA can regulate PKR activation during lysosomal damage. However, we could not detect the presence of dsRNA in response to LLOMe treatment (Fig. EV2G). In addition, knocking down lysosomal RNase RNASET2 (Haud et al, 2011) did not affect the activation of PKR upon LLOMe treatment (Fig. EV2H), which aligns with our previous observation that RNASET2 did not affect SG formation during lysosomal damage (Jia et al, 2022). Furthermore, we generated a PKR mutant deficient in dsRNA-binding ability, PKRK60A&K150A (McMillan et al, 1995; Patel et al, 1996). However, the overexpression of PKRK60A&K150A in PKRKO cells still led to the restoration of eIF2α phosphorylation and PKR activation during lysosomal damage (Fig. EV2I). Thus, these data suggest that dsRNA is not the trigger for PKR activation in response to lysosomal damage.

Figure 3. PKR and its activator PACT regulate eIF2α phosphorylation on damaged lysosomes.

(A) Quantitative liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC/MS/MS) using the data-independent acquisition (DIA) technique to identify eIF2α binding partners that were proximity-biotinylated by APEX2-eIF2α during lysosomal damage (1 mM LLOMe for 1 h). Scatter (volcano) plot shows log2 fold change (LLOMe/CTR; spectral counts) and –log10 p value for the proteins identified and quantified in three independent experiments. Green dots indicate increase in proximity to eIF2α (log2 fold change ≥ 1), and red dots indicate decrease in proximity to eIF2α (log2 fold change ≤ −1) during LLOMe treatment. Orange dots indicate values below the statistical significance cut-off (P ≥ 0.05). Bubble size represents a normalized value for the total amount of spectral counts for the protein indicated. PACT, PKR and ALIX proteins are highlighted as purple circles (see Dataset EV1). (B) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1-GFP puncta in wild type (WT) or PKR knockout (PKRKO) U2OS G3BP1-GFP cells. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (C) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and PKR (T446) in WT or PKRKO U2OS G3BP1-GFP cells, as well as in cells overexpressing FLAG-PKR in PKRKO U2OS G3BP1-GFP cells. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. The level of phosphorylation of PKR (T446) was quantified based on three independent experiments. (D) Co-IP analysis of interactions between eIF2α and PKR/PACT during lysosomal damage. HEK293T cells expressing FLAG (control) or FLAG-eIF2α were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. (E) (i) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or PACT siRNA for knockdown (PACTKD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta; (ii) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and PKR (T446) in SCR or PACTKD cells; 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. The level of phosphorylation of PKR (T446) was quantified based on three independent experiments. (F) Analysis of proteins associated with purified lysosomes (LysoIP; TMEM192-3xHA) from HEK293T cells treated with 1 mM LLOMe in the presence or absence of 210 nM imidazolo-oxindole C16 for 1 h. TMEM192-2xFLAG, control. The level of PKR, eIF2α and PACT in LysoIP was quantified based on three independent experiments shown in Fig. EV3B. (G) Schematic summary of the findings in Figs. 3 and EV3. NT, untreated cells. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Fig. EV3. Source data are available online for this figure.

Interestingly, the protein activator of PKR, PACT, prominently emerged with the most significant fold increase following lysosomal damage (Fig. 3A). PACT is known to facilitate the stress-induced phosphorylation and activation of PKR through direct interaction (Patel and Sen, 1998; Singh and Patel, 2012). This interaction disrupts PKR’s self-inhibition, leading to PKR autophosphorylation including at Thr446, which converts it into its fully active form capable of phosphorylating protein substrates, such as eIF2α (Chukwurah et al, 2021; Sadler and Williams, 2007). We confirmed increased interactions of PKR and PACT with eIF2α upon lysosomal damage by co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) of FLAG-eIF2α with endogenous PKR and PACT (Fig. 3D). Next, we examined whether PKR and PACT are functionally necessary for eIF2α phosphorylation triggered by lysosomal damage. We observed a decrease in PKR activation, eIF2α phosphorylation, and SG formation observed in U2OS cells with PACT knockdown (PACTKD) during lysosomal damage (Fig. 3E). Overexpression of PACT in PACTKD cells restores PKR activation during lysosomal damage (Fig. EV2J). This finding aligns with the role of PKR in controlling eIF2α phosphorylation and SG formation. Thus, both PKR and its activator PACT regulate eIF2α phosphorylation for SG formation during lysosomal damage.

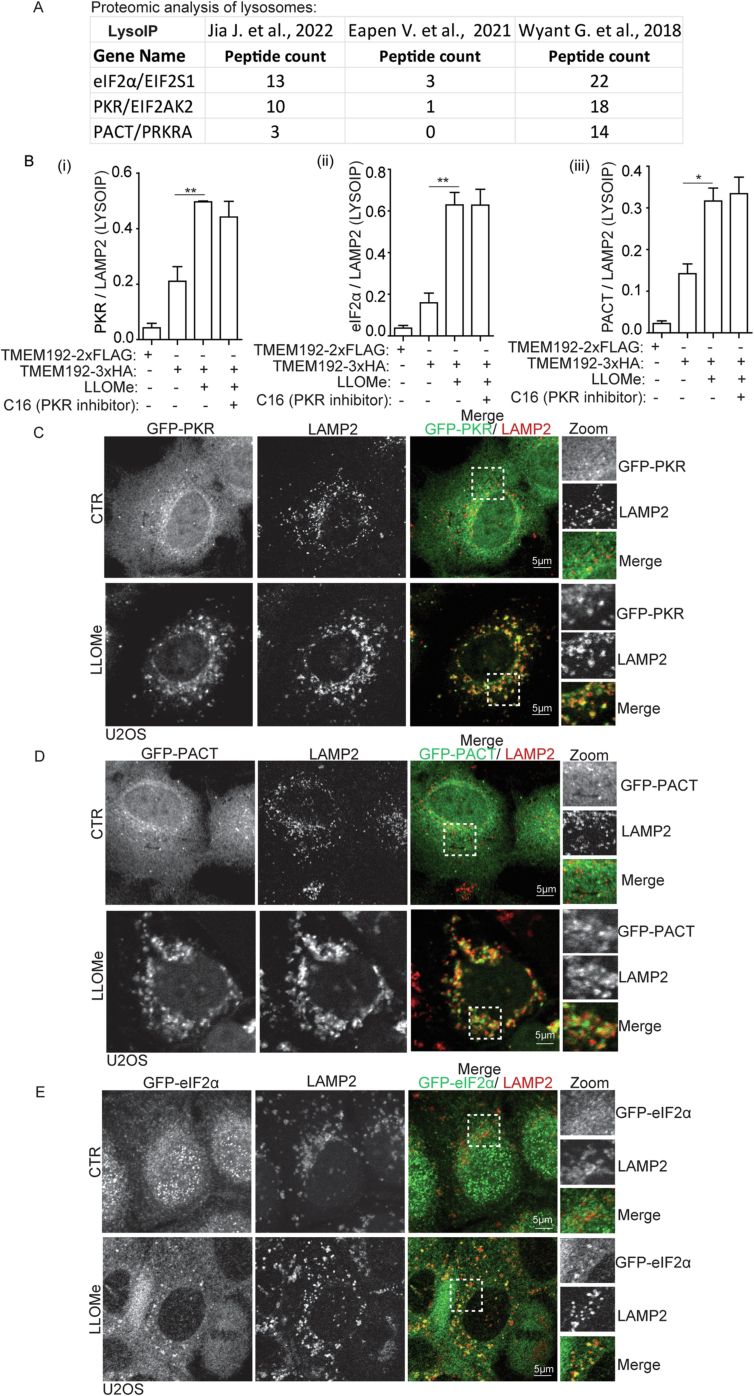

PKR and PACT control eIF2α phosphorylation on damaged lysosomes

We previously performed proteomic analyses of lysosomes that were purified using LysoIP (Jia et al, 2022), a well-established approach to isolate lysosomes by the lysosomal membrane protein TMEM192 (Abu-Remaileh et al, 2017; Jia et al, 2020c). These analyses indicate the presence of PKR, PACT, and eIF2α on lysosomes (Fig. EV3A). This finding is further supported by similar results from LysoIP proteomic analysis conducted by other research groups (Eapen et al, 2021; Wyant et al, 2018) (Fig. EV3A). Using LysoIP immunoblotting, we confirmed the presence of PKR, PACT and eIF2α on lysosomes and found an elevation in their association with damaged lysosomes (Figs. 3F and EV3B). We also observed that the phosphorylation of both PKR and eIF2α occurred on damaged lysosomes (Fig. 3F). Notably, this effect was effectively blocked by a specific PKR’s inhibitor, imidazolo-oxindole C16, known for its ability to inhibit PKR’s autophosphorylation by binding to PKR’s ATP-binding pocket(Gal-Ben-Ari et al, 2019; Jammi et al, 2003; Tronel et al, 2014) (Fig. 3F). Moreover, through confocal fluorescence microscopy, an increased association of PKR, PACT, and eIF2α was detected with damaged lysosomes (Fig. EV3C–E). In summary, we conclude that PKR and its activator, PACT, regulate eIF2α phosphorylation on damaged lysosomes (Fig. 3G).

Figure EV3. PKR, PACT and eIF2α are associated with damaged lysosomes.

(A) Summary of the literature on the detected peptide count of PKR, PACT and eIF2α in the proteomic analysis of lysosomes based on LysoIP LC/MS/MS analysis. (B) Quantification of Fig. 3F; the level of PKR, eIF2α and PACT in LysoIP was quantified based on three independent experiments. (C) Confocal microscopy imaging of GFP-PKR and LAMP2 in U2OS cells treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Scale bar, 5 μm. (D) Confocal microscopy imaging of GFP-PACT and LAMP2 in U2OS cells treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Scale bar, 5 μm. (E) Confocal microscopy imaging of GFP-eIF2α and LAMP2 in U2OS cells treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Scale bar, 5 μm. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Fig. 3.

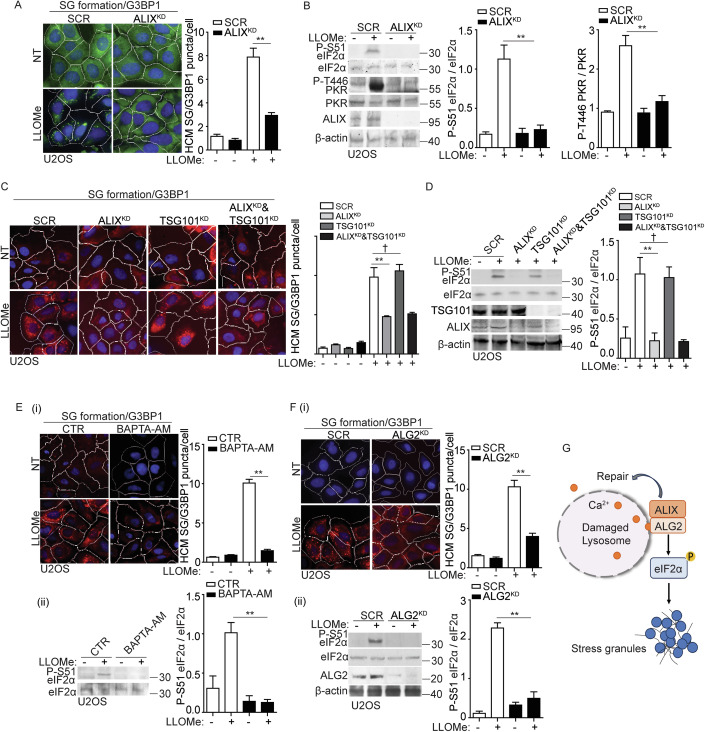

ALIX and ALG2 are required for stress granule formation by sensing calcium release from damaged lysosomes

In our proteomic analysis of eIF2α binding partners (Fig. 3A), we observed an increased association between eIF2α and ESCRT components such as ALIX, CHMP2B, and CHMP4B following lysosomal damage. Specifically, ALIX showed a greater than 10-fold increase (Fig. 3A). We next determined whether these ESCRT components were involved in eIF2α phosphorylation and SG formation triggered by lysosomal damage. Upon lysosomal damage, we observed a significant reduction in SG formation upon knockdown of ALIX in U2OS cells (ALIXKD), as quantified by G3BP1 puncta using HCM (Fig. 4A,C). This was also reflected in the decreased phosphorylation of eIF2α and PKR in ALIXKD cells during LLOMe treatment (Fig. 4B,D), indicating an impact of ALIX on the upstream signaling of SG formation. In addition, we have tested the effect of ALIX knockdown on lysosomal biogenesis and observed no significant change in the overall number of lysosomes, as measured by the lysosomal marker LAMP2 in ALIXKD cells (Fig. EV4A). This aligns with our previous observations that the depletion of ALIX does not affect lysosomal function, as measured by the acidification of lysosomes using the Lysotracker assay and the activity of cathepsin B using the Magic Red assay (Jia et al, 2020c). However, the knockdown of CHM2B or CHMP4B had no discernible effect on SG formation and its upstream events (Fig. EV4B,C). Previous studies showed that the depletion of both ALIX and TSG101 effectively impedes lysosomal repair by eliminating ESCRT recruitment (Niekamp et al, 2022; Radulovic et al, 2018; Skowyra et al, 2018). We found that TSG101 has no effect on the regulation of SG formation upon lysosomal damage. This is supported by the absence of any significant changes in SG formation and eIF2α phosphorylation in TSG101 knockdown U2OS cells (TSG101KD) (Fig. 4C,D). ALIX has been reported to sense lysosomal damage through the detection of calcium leakage, which is facilitated by its calcium binding partner, ALG2 (Chen et al, 2024; Jia et al, 2020a; Niekamp et al, 2022; Skowyra et al, 2018). Notably, ALG2 exhibited increased proximity to eIF2α upon lysosomal damage (Fig. 3A). To further determine the regulatory role of ALIX in SG formation upon lysosomal damage, we utilized BAPTA-AM, the calcium chelator and ALG2 knockdown U2OS cells (ALG2KD) to prevent the recruitment of ALIX to damaged lysosomes as previously reported (Jia et al, 2020a; Skowyra et al, 2018). This was confirmed by the observed decrease in ALIX puncta formation upon lysosomal damage in cells treated with BAPTA-AM or in ALG2KD cells (Fig. EV4D). Importantly, we also observed a significant reduction in SG formation and eIF2α phosphorylation in cells treated with BAPTA-AM, or in ALG2KD cells during lysosomal damage (Fig. 4E,F). Furthermore, overexpression of ALIX in ALIXKD cells and overexpression of ALG2 in ALG2KD cells both restored SG formation and eIF2α phosphorylation, respectively, during lysosomal damage (Fig. EV4E,F). Thus, we conclude that ALIX and its partner, ALG2, modulate eIF2α phosphorylation by sensing calcium leakage as lysosomal damage signal, thereby initiating SG formation (Fig. 4G).

Figure 4. ALIX and ALG2 are required for stress granule formation by sensing calcium release from damaged lysosomes.

(A) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or ALIX siRNA for knockdown (ALIXKD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (B) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and PKR (T446) in U2OS cells transfected with either scrambled siRNA as control (SCR) or ALIX siRNA for knockdown (ALIXKD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. The level of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and PKR (T446) was quantified based on three independent experiments. (C) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), ALIX siRNA for knockdown (ALIXKD) or TSG101 siRNA for knockdown (TSG101KD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (D) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), ALIX siRNA for knockdown (ALIXKD) or TSG101 siRNA for knockdown (TSG101KD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. The level of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) was quantified based on three independent experiments. (E) (i) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells pre-treated with 15 µM BAPTA-AM for 1 h, subjected to 2 mM LLOMe treatment for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (ii) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS cells as described in (i) and was quantified based on three independent experiments. (F) (i) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), or ALG2 siRNA for knockdown (ALG2KD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (ii) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS cells as described in (i) and was quantified based on three independent experiments. (G) Schematic summary of the findings in Figs. 4 and EV4. NT, untreated cells. CTR, control. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Fig. EV4. Source data are available online for this figure.

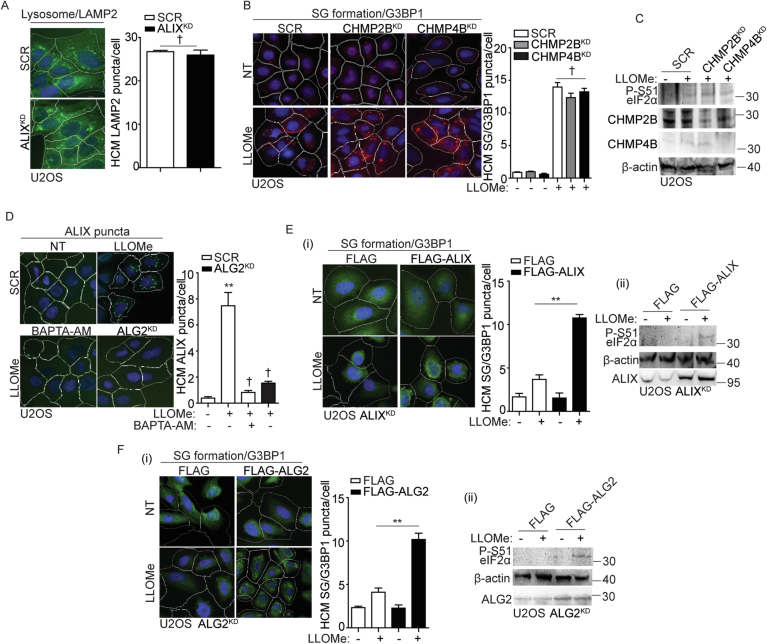

Figure EV4. ALIX regulates stress granule formation during lysosomal damage.

(A) Quantification by HCM of LAMP2 in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), or ALIX siRNA for knockdown (ALIXKD). White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified LAMP2 puncta. (B) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), CHMP2B siRNA for knockdown (CHMP2BKD) or CHMP4B siRNA for knockdown (CHMP4BKD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (C) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), CHMP2B siRNA for knockdown (CHMP2BKD) or CHMP4B siRNA for knockdown (CHMP4BKD), subjected to 2 mM LLOMe treatment for 30 min. (D) Quantification by HCM of ALIX puncta in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), or ALG2 siRNA for knockdown (ALG2KD), or pre-treated with 15 µM BAPTA-AM for 1 h. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified ALIX puncta. (E) (i) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS ALIX knockdown cells (ALIXKD) overexpressing FLAG or FLAG-ALIX. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (ii) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS cells as described in (i). (F) (i) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS ALG2 knockdown cells (ALG2KD) overexpressing FLAG or FLAG-ALG2. Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (ii) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) in U2OS cells as described in (i). NT, untreated cells. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Fig. 4.

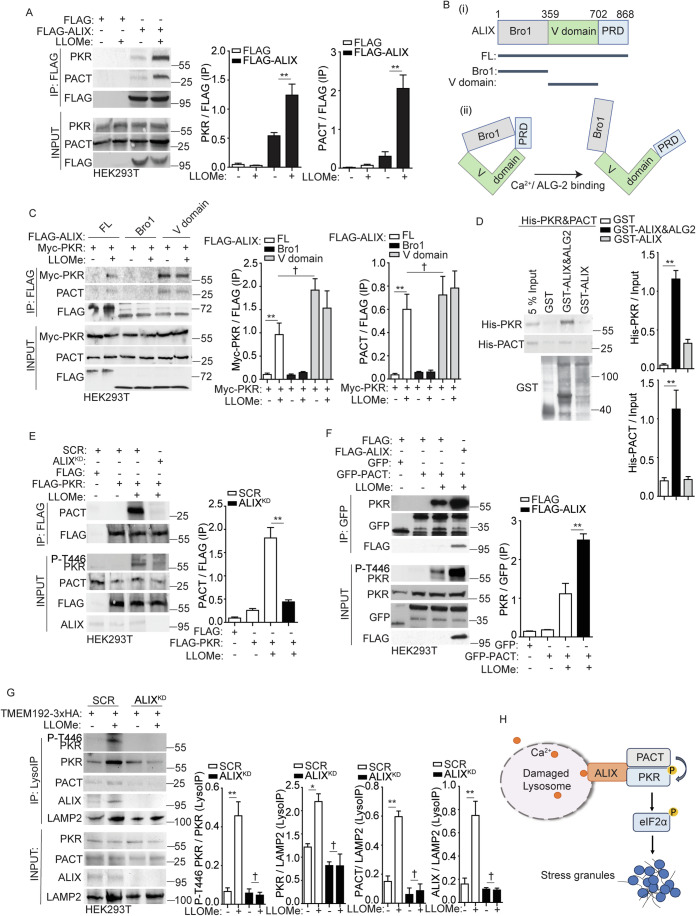

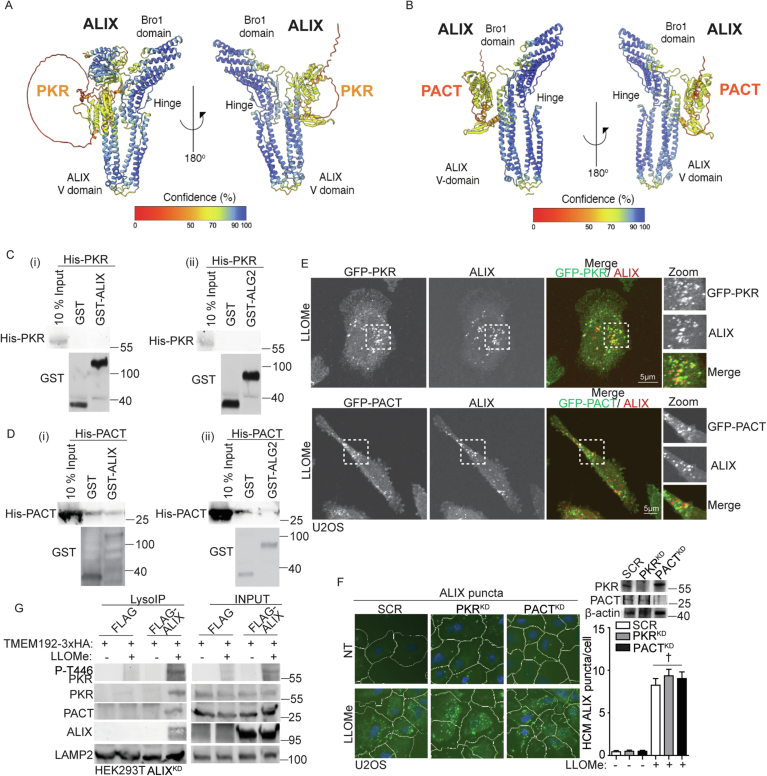

ALIX associates with PKR and PACT in response to lysosomal damage

Given that eIF2α phosphorylation is initiated by its upstream kinase PKR, and its activator PACT (Fig. 3), our subsequent investigation delved into exploring the relationship among ALIX, PKR and PACT. Using a co-IP assay, we tested the interaction between FLAG-ALIX and endogenous PKR and PACT. Their interactions were notably enhanced following treatment with LLOMe (Fig. 5A). ALIX is composed of three distinct domains: Bro1 domain, V domain, and proline-rich domain (PRD) (Fig. 5B). These domains have the potential to remain inactive due to intramolecular interactions but can be activated through interaction with ALG2 in a calcium-dependent manner (Maki et al, 2016; Scheffer et al, 2014; Sun et al, 2015; Vietri et al, 2020) (Fig. 5B). Next, we generated the domain deletions of ALIX (Fig. 5B(i)). The mapping analysis of ALIX domains necessary for binding to PKR and PACT revealed the indispensable role of the V domain in their interaction (Fig. 5C). In addition, increased associations among full-length ALIX, PKR and PACT were observed upon LLOMe treatment (Fig. 5A,C), suggesting that lysosomal damage activates ALIX by releasing its V domain for association with PKR and PACT. This is corroborated by the interaction of the V domain of ALIX with PKR and PACT, even in cells that were not subjected to lysosome damage induced by LLOMe (Fig. 5C). The interaction between the V domain of ALIX with PKR or PACT was also predicted using AlphaFold 2 (Jumper et al, 2021) (Fig. EV5A,B). While co-IP results indicate that ALIX, PACT and PKR can form protein complexes (Fig. 5A,C), GST pulldown assays showed that ALIX or its partner ALG2 individually did not directly interact with PACT or PKR (Fig. EV5C,D). However, we found that ALIX and ALG2 together can directly interact with the PACT and PKR complex (Fig. 5D). This suggests that conformational changes, possibly induced by ALG2 exposing the V domain of ALIX (Sun et al, 2015) and PACT promoting PKR dimerization (Li et al, 2006), are important for the direct interaction. Nevertheless, a model emerges where ALIX and ALG2 interaction enables their direct binding to the PACT-PKR complex during calcium efflux caused by lysosome damage. Furthermore, by confocal fluorescence microscopy, we observed the association among ALIX, PKR, and PACT during lysosomal damage (Fig. EV5E). Thus, ALIX interacts with PKR and PACT in response to lysosomal damage.

Figure 5. ALIX promotes the association between PKR and its activator PACT on damaged lysosomes.

(A) Co-IP analysis of interactions among ALIX, PKR and PACT during lysosomal damage. HEK293T cells expressing FLAG (control) or FLAG-ALIX were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. Quantification of IP analysis based on three independent experiments. (B) (i) Schematic diagram of ALIX mutants used in this study. FL (full length); Bro1 (Bro1 domain); V domain; PRD (proline-rich domain). Numbers, residue positions. (ii) Schematic illustration of the Ca2+/ALG-2-induced open conformation of ALIX. (C) Co-IP analysis of interactions among ALIX mutants, PKR and PACT during lysosomal damage. HEK293T cells expressing FLAG tagged ALIX mutants and Myc-PKR were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. Quantification of IP analysis based on three independent experiments. (D) GST pulldown assay of in vitro translated His-tagged PKR and His-tagged PACT with GST, GST-tagged ALIX, with or without GST-tagged ALG2 in the presence of 10 μM CaCl2. Quantification of the GST pulldown (the corresponding protein relative to its input) was performed based on three independent experiments. (E) Co-IP analysis of interactions between FLAG-PKR and PACT in HEK293T cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), or ALIX siRNA for knockdown (ALIXKD) during lysosomal damage. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. Quantification of IP analysis based on three independent experiments. (F) Co-IP analysis of interactions between PKR and GFP-PACT in HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG, or FLAG-ALIX during lysosomal damage. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. Quantification of IP analysis based on three independent experiments. (G) Analysis of proteins associated with purified lysosomes (LysoIP; TMEM192-3xHA) from HEK293T cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), or ALIX siRNA for knockdown (ALIXKD). Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Quantification of LysoIP analysis based on three independent experiments. (H) Schematic summary of the findings in Figs. 5 and EV5. See also Fig. EV5. †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ANOVA. Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV5. PKR and PACT associate with ALIX during lysosomal damage.

(A) AlphaFold 2 predicted the interaction between PKR and ALIX, with the C-terminal PRD domain removed. (B) AlphaFold 2 predicted the interaction between PACT and ALIX, with the C-terminal PRD domain removed. (C) GST pulldown assay of in vitro translated His-tagged PKR with GST or GST-tagged ALIX (i) or ALG2 (ii) in the presence of 10 μM CaCl2. (D) GST pulldown assay of in vitro translated His-tagged PACT with GST or GST-tagged ALIX (i) or ALG2 (ii) in the presence of 10 μM CaCl2. (E) Confocal microscopy imaging of GFP-PKR/PACT and ALIX in U2OS cells treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Scale bar, 5 μm. (F) Quantification by HCM of ALIX puncta in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), PKR siRNA for knockdown (PKRKD), or PACT siRNA for knockdown (PACTKD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified ALIX puncta. (G) Analysis of proteins associated with purified lysosomes (LysoIP; TMEM192-3xHA) from HEK293T ALIX knockdown cells (ALIXKD) overexpressing FLAG or FLAG-ALIX. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 1 h. NT, untreated cells. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). †p ≥ 0.05 (not significant), ANOVA. See also Fig. 5.

ALIX promotes the association between PKR and its activator PACT on damaged lysosomes

Next, we quantified by HCM the ALIX puncta response to lysosomal damage in cells where PKR or PACT had been knocked down. We observed that the presence or absence of PKR and PACT did not affect ALIX response to lysosomal damage (Fig. EV5F). This suggests that ALIX may potentially precede PKR and PACT for eIF2α phosphorylation upon lysosomal damage. Considering the decrease in the phosphorylation of PKR in ALIXKD cells and the increased association among ALIX, PKR, and PACT following lysosomal damage (Figs. 4B,D and 5A), we hypothesize that ALIX regulates PKR phosphorylation by modulating the association between PKR and its activator, PACT, during lysosomal damage. Using co-IP assays, we confirmed the formation of complexes between FLAG-PKR and endogenous PACT during lysosomal damage (Fig. 5E). However, this interaction was reduced in ALIXKD HEK293T cells (Fig. 5E), resulting in decreased PKR phosphorylation during LLOMe treatment. Conversely, the overexpression of ALIX led to a further enhancement in the increased association between GFP-PACT and endogenous PKR, and this was accompanied by an increase in PKR phosphorylation during lysosomal damage (Fig. 5F). These data indicates that ALIX is essential for PKR phosphorylation by controlling the interaction between PKR and PACT during lysosomal damage. Next, we examined whether this regulatory event occurred on damaged lysosomes by conducting LysoIP immunoblotting in ALIXKD HEK293T cells. In this assay, we observed that ALIXKD HEK293T cells no longer displayed PKR phosphorylation on damaged lysosomes, accompanied by a reduced recruitment of PKR and PACT to lysosomes, as determined by Western blot analysis of lysosomes isolated using LysoIP (Fig. 5G). In contrast, ALIX overexpression in ALIXKD HEK293T cells reinstated PKR and PACT recruitment to damaged lysosomes and restored PKR phosphorylation on these organelles (Fig. EV5G). This suggests that ALIX is responsible for the recruitment and regulation of PKR and PACT on damaged lysosomes. In summary, we conclude that ALIX recruits PKR and its activator, PACT, to damaged lysosomes and regulates the activation of PKR by enhancing its association with PACT, consequently leading to eIF2α phosphorylation and SG formation (Fig. 5H).

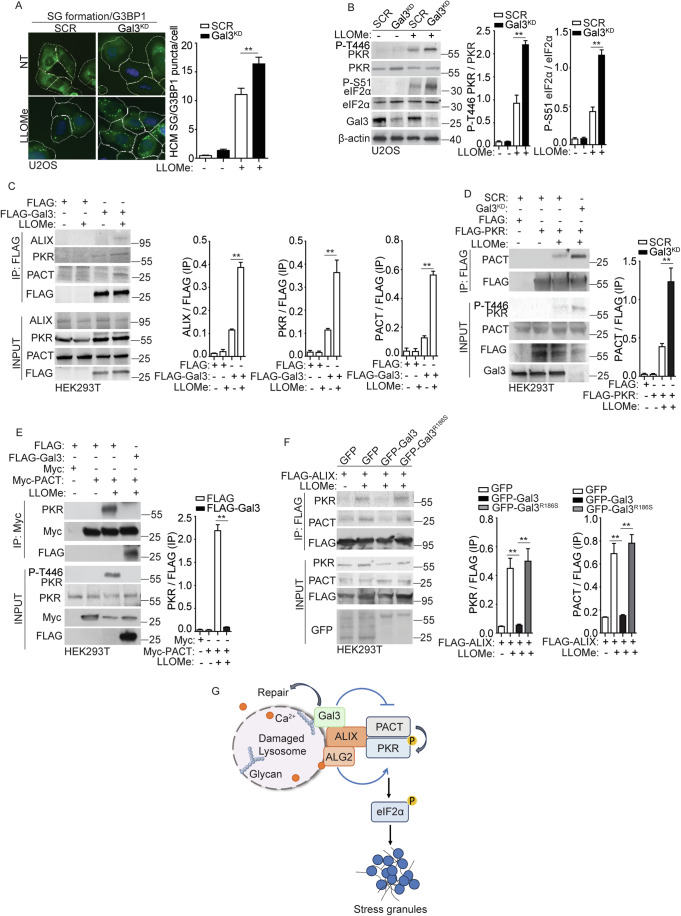

Galectin-3 inhibits stress granule formation by reducing the association between PKR and PACT during lysosomal damage

Previously, we reported that galectin-3 (Gal3), a β-galactoside-binding protein that recognizes damage-exposed glycan, can recruit ALIX to damaged lysosomes and promote ESCRT function for lysosomal repair and restoration (Jia et al, 2020d). We examined whether Gal3 is involved in the regulatory process of SG formation during lysosomal damage. In U2OS cells subjected to Gal3 knockdown (Gal3KD), we observed an elevated level of SG formation, quantified by the formation of G3BP1 puncta using HCM (Fig. 6A). This result was consistent with our earlier report showing an increase in SGs in Gal3 knockout HeLa cells (Jia et al, 2022). Here, we further detected the upstream signaling events leading to SG formation in Gal3KD U2OS cells and observed a significant increase in the phosphorylation of PKR and eIF2α in the absence of Gal3 following LLOMe treatment (Fig. 6B). These data indicate that Gal3 has a negative effect on the activation of PKR and eIF2α, thereby affecting SG formation during lysosomal damage. Next, the relationship among Gal3, PKR, and PACT was tested. The co-IP results showed that Gal3 can be in protein complexes with ALIX, PKR, and PACT upon lysosomal damage (Fig. 6C). When determining if Gal3 can control the association between PKR and PACT, we found a marked increase in their association in the absence of Gal3 (Fig. 6D). This was further confirmed by the increased PKR phosphorylation under the same conditions. On the contrary, when Gal3 was overexpressed, it led to a significant reduction in the interaction between PKR and PACT, consequently resulting in reduced PKR phosphorylation upon LLOMe treatment (Fig. 6E). We interpret the inhibitory role of Gal3 in the association between PKR and PACT as a result of their competition for ALIX. Consistent with this interpretation, we observed a significantly reduced interaction among ALIX, PACT, and PKR in Gal3-overexpressing cells during LLOMe treatment (Fig. 6F). However, when we overexpressed the Gal3R186S mutant, which has been previously shown to lose the ability to recognize damaged lysosomes (Aits et al, 2015), it failed to regulate the protein complex of ALIX, PACT, and PKR upon lysosomal damage (Fig. 6F). Moreover, given our previous finding that Gal3 facilitates ESCRT-mediated lysosomal repair via ALIX (Jia et al, 2020d), these observations provide evidence of Gal3’s role in balancing ALIX-mediated lysosomal repair and ALIX-mediated SG formation (Fig. 6G). Thus, we conclude that the recruitment of Gal3 to damaged lysosomes plays an inhibitory effect on the regulation of the upstream processes of SG formation by decreasing the association between PKR and PACT (Fig. 6G).

Figure 6. Galectin-3 inhibits stress granule formation by reducing the association between PKR and PACT during lysosomal damage.

(A) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), or galectin-3 (Gal3) siRNA for knockdown (Gal3KD). Cells were treated with 2 mM LLOMe for 30 min. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; green masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (B) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and PKR (T446) in U2OS cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), or galectin-3 (Gal3) siRNA for knockdown (Gal3KD), subjected to 2 mM LLOMe treatment for 30 min. The level of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and PKR (T446) was quantified based on three independent experiments. (C) Co-IP analysis of interactions among FLAG-Gal3, ALIX, PKR and PACT in HEK293T cells during lysosomal damage. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. Quantification of IP analysis for ALIX, PKR, and PACT based on three independent experiments. (D) Co-IP analysis of interactions between FLAG-PKR and PACT in HEK293T cells transfected with scrambled siRNA as control (SCR), or Gal3 siRNA for knockdown (Gal3KD) during lysosomal damage. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. Quantification of IP analysis based on three independent experiments. (E) Co-IP analysis of interactions between Myc-PACT and PKR in HEK293T cells transfected with FLAG, or FLAG-Gal3 during lysosomal damage. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. Quantification of IP analysis based on three independent experiments. (F) Co-IP analysis of interactions among FLAG-ALIX, PKR and PACT in HEK293T cells transfected with GFP, GFP-Gal3 or GFP-Gal3R186S during lysosomal damage. Cells were treated with 1 mM LLOMe for 30 min. Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and immunoblotted for indicated proteins. Quantification of IP analysis based on three independent experiments. (G) Schematic summary of the findings in Fig. 6. NT, untreated cells. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). **p < 0.01, ANOVA. Source data are available online for this figure.

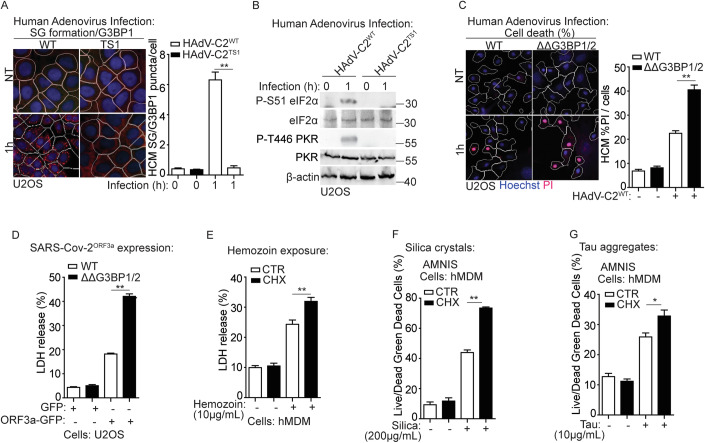

Stress granule formation promotes cell survival in response to lysosomal damage in the context of disease states

Lysosomal damage serves as both a cause and consequence of many disease conditions, including infectious and neurodegenerative diseases (Amaral et al, 2023; Ballabio and Bonifacino, 2020; Bonam et al, 2019; Fehrenbacher et al, 2005). We tested whether the above molecular and cellular processes that transduce lysosomal damage signals to induce SG formation are important for cell survival in disease contexts. Lysosomal damage can occur from viral infections including those caused by non-enveloped adenovirus and enveloped SARS-CoV-2 infections (Aits et al, 2013; Barlan et al, 2011; Daussy and Wodrich, 2020; Thurston et al, 2012; Wang et al, 2018). Adenovirus enters cells through endocytosis and damages lysosomes by releasing its protease, which allows access to the cytosol and subsequently the nucleus for replication (Barlan et al, 2011; Greber et al, 1996; Pied et al, 2022; Wiethoff and Nemerow, 2015). We employed the wild type human adenovirus species C2 (HAdV-C2WT) and its protease-deficient mutant TS1 (HAdV-C2TS1), the latter lacking the ability to damage lysosomes (Gallardo et al, 2021; Greber et al, 1996; Martinez et al, 2015). U2OS cells were infected with either HAdV-C2WT or HAdV-C2TS1 and the lysosomal damage marker LysoTracker Red (LTR), which measures lysosomal acidification (Chazotte, 2011; Jia et al, 2020a; Pierzyńska‐Mach et al, 2014), was quantified by HCM in infected cells. Consistent with earlier findings (Luisoni et al, 2015; Martinez et al, 2015; Pied et al, 2022), HAdV-C2WT led to a reduction in LTR+ profiles, whereas HAdV-C2TS1 did not show such an effect (Appendix Fig. S1A). In addition, SG formation and the phosphorylation of eIF2α and PKR were detected in cells infected with HAdV-C2WT but not in those infected with HAdV-C2TS1 (Fig. 7A,B). These results imply that lysosomal damage triggered by HAdV-C2 infection can activate the PKR-eIF2α pathway, resulting in SG formation. We then tested whether SG formation is important for cell survival during HAdV-C2 infection. In SG-deficient U2OS (ΔΔG3BP1/2) cells, compared to wild-type U2OS cells, we observed an elevated level of cell death, using a PI uptake assay, during HAdV-C2WT infection (Fig. 7C). In addition, we expanded on our previous investigations showing that lysosomal damage induced by the expression of SARS-CoV-2 ORF3a protein (SARS-CoV-2ORF3a) can also trigger SG formation (Jia et al, 2022). Following the overexpression of SARS-CoV-2ORF3a in U2OS cells, a notable rise in cell death was observed through an LDH release assay in ΔΔG3BP1/2 cells compared to control cells (Fig. 7D). Collectively, SG formation triggered by lysosomal damage emerges as a crucial process for cell survival during the viral infections examined.

Figure 7. Stress granule formation promotes cell survival in response to lysosomal damage during disease states.

(A) Quantification by HCM of G3BP1 puncta in U2OS cells infected with wild-type human adenovirus C2 (HAdV-C2WT) or C2 TS1 mutant (HAdV-C2TS1) at MOI = 10 for 1 h. White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified G3BP1 puncta. (B) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylation of eIF2α (S51) and PKR (T446) in U2OS cells infected with wild type human adenovirus C2 (HAdV-C2WT) or C2 TS1 mutant (HAdV-C2TS1) at MOI = 10 for 1 h. (C) Quantification by HCM of cell death by a propidium iodide (PI) uptake assay in U2OS wild type (WT) and G3BP1&2 double knockout (ΔΔG3BP1/2) cells during adenovirus infection. Cells were infected with wild-type human adenovirus C2 (HAdV-C2WT) at MOI = 10 for 1 h, and then stained with propidium iodide PI (dead cells) and Hoechst-33342 (total cells). White masks, algorithm-defined cell boundaries; red masks, computer-identified PI+ nuclei. (D) Cell death analysis of supernatants of U2OS WT and ΔΔG3BP1/2 cells by a LDH release assay during SARS-Cov-2ORF3a expression. Cells were transfected with the GFP-SARS-Cov-2ORF3a construct overnight. (E) Cell death analysis of supernatants of human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDM) by a LDH release assay during hemozoin exposure. Cells were treated with 10 µg/ml hemozoin for 4 h in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX). (F) Quantification using AMNIS of cell death by Live/DeadTM stain kit in hMDM during silica treatment. Cells were treated with 200 µg/mL silica for 4 h in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX), and then stained using Live/DeadTM stain kit (ThermoFisher). (G) Quantification using AMNIS of cell death by Live/DeadTM stain kit in hMDM during the treatment of tau oligomer. Cells were treated with 10 µg/mL tau oligomer for 4 h in the presence or absence of 1 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX), and then stained using Live/DeadTM stain kit (ThermoFisher). CTR, control. Data, means ± SEM (n = 3); HCM: n ≥ 3 (each experiment: 500 valid primary objects/cells per well, ≥5 wells/sample). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ANOVA. See also Appendix Fig. S1. Source data are available online for this figure.

In addition, other disease-associated agents in the context of human parasitic infections were examined that have the potential to damage lysosomes, such as malarial pigment (hemozoin). This parasitic agent is a crystalline and insoluble byproduct of hemoglobin digestion by Plasmodial species that is phagocytosed by circulating monocytes and neutrophils, and tissue macrophages, thus promoting immunopathological effects in human malaria (Anyona et al, 2022; Coronado et al, 2014; Guerra et al, 2019; Moore et al, 2004; Schwarzer et al, 1992; Weissbuch and Leiserowitz, 2008). Treatment of human monocytic THP-1 with physiological concentrations of hemozoin (0.1, 1.0, and 10.0 µg/mL) for 4 h, dose-dependently induced lysosomal damage, monitored by ALIX puncta formation serving as a lysosomal repair marker (Jia et al, 2020c; Radulovic et al, 2018; Skowyra et al, 2018) (Appendix Fig. S1B). While a previous report showed that hemozoin is rapidly ingested by human monocytes and exclusively localized in normally acidified phagolysosomes (Schwarzer et al, 2001), our findings suggest that hemozoin can perturb lysosomal membranes. Differences in the studies may be due to cell types, dosage, and treatment duration. In addition, stimulation with hemozoin (10.0 µg/mL) for 4 h, resulted in both SG formation and the phosphorylation of eIF2α and PKR (Appendix Fig. S1C, D). Blocking SG formation with cycloheximide in hMDM cells, showed an increased cell death as measured by LDH release assay in response to hemozoin treatment (10.0 µg/mL) (Fig. 7E). Moreover, we examined other lysosomal damaging agents, such as silica crystals associated with silicosis (Hornung et al, 2008; Mossman and Churg, 1998; Wang et al, 2017) and tau aggregates implicated in Alzheimer’s disease (Flavin et al, 2017; Papadopoulos et al, 2017). We have previously reported that both silica crystals and tau aggregates induce lysosomal damage, leading to SG formation (Jia et al, 2022). This effect was further confirmed by detecting the phosphorylation of eIF2α and PKR in hMDM cells in response to the treatment of silica crystals or tau aggregates (Appendix Fig. S1D). The prevention of SG formation with cycloheximide during the treatment of silica crystals or tau aggregates led to augmented cell death, as assessed using an AMNIS imaging flow cytometer in hMDM cells (Fig. 7F,G). Similarly, the application of another SG inhibitor, ISRIB to inhibit SG formation triggered by silica crystals or tau aggregate, produced a comparable effect on cell death of hMDM cells, measured by PI uptake assay (Appendix Fig. S1E,F). To further emphasize the role of the PKR-eIF2α pathway in controlling SG formation and promoting cell survival in disease contexts, we employed the PKR inhibitor C16 and assessed its impact on cell death in U2OS and hMDM cells via LDH release assay. We observed that C16 treatment increased cell death when cells were exposed to various physiological agents that induce lysosomal damage (Appendix Fig. S1G–K). These findings also align with the role of SGs in promoting cell survival. In summary, our findings suggest that SG formation induced by lysosomal damage is important for cell survival against diverse pathogenic challenges associated with major human diseases.

Discussion

In this study, we uncovered the regulation and significance of SG formation in response to lysosomal damage, providing insights into the interaction between membrane-bound organelles and membrane-less condensates. Through unbiased approaches, including proteomic analysis and high content microscopy, we defined a novel signaling pathway that transmits calcium leakage from damaged lysosomes to induce eIF2α phosphorylation, ultimately leading to SG formation, thus promoting cell survival. This study aligns with recent research indicating the role of SGs in plugging damaged membranes and aiding in lysosomal repair (Bussi et al, 2023), underscoring SG formation as a vital cellular protective mechanism against lysosomal damage, essential for survival.

How does the cell detect lysosomal damage to initiate SGs? Our study revealed the significant involvement of a calcium signal in this process. Lysosomes function as key intracellular calcium reservoirs for various cellular activities (Lloyd-Evans et al, 2020; Xu and Ren, 2015). We found that ALIX and ALG2 sense calcium leakage from damaged lysosomes, which activates ALIX’s role in regulating PKR’s activity. This ultimately leads to eIF2α phosphorylation and SG formation. In addition, our study indicates that PKR activation in response to lysosomal damage is independent of dsRNA but relies on its endogenous activator PACT. Under cellular stress, PACT directly binds to PKR, promoting PKR dimerization and conformational changes that lead to its autophosphorylation and enzymatic activation (Chukwurah et al, 2021). Notably, PKR activation is also observed in response to monosodium urate exposure (Lu et al, 2012), which is known to cause lysosomal damage (Maejima et al, 2013). Moreover, we found that ALIX controls the association between PKR and PACT, resulting in the phosphorylation of eIF2α. Importantly, we found that the role of ALIX and ALG2 in controlling eIF2α phosphorylation is distinct from their established function in ESCRT-mediated lysosomal repair. This suggests the multifaceted roles of ALIX and ALG2 as calcium sensors in coordinating cellular responses to lysosomal damage. Furthermore, our findings also indicate the intricate and adaptable nature of calcium signaling pathways in coordinating various cellular defense mechanisms against lysosomal damage. This extends beyond their involvement in TFEB nuclear translocation and phosphoinositide-mediated rapid lysosomal repair (Medina et al, 2015; Nakamura et al, 2020; Tan and Finkel, 2022).

SGs consist of RNA-binding proteins and untranslated mRNA, both playing a crucial role in the process of phase separation (Millar et al, 2023). In addition to the calcium signal we reported here as a trigger for SG formation during lysosomal damage, a recent study suggests that a decrease in pH can also induce SG formation on damaged lysosomes (Bussi et al, 2023). This is in line with the reported role of pH in G3BP1-driven SG condensation (Guillén-Boixet et al, 2020). However, the latter report indicates that pH may not directly regulate the RNA-binding affinity of G3BP1 but instead influences protein-protein interactions. It is worth noting that these experiments were conducted in an in vitro system and the presence of mRNA. Therefore, it raises the possibility that multiple mechanisms may collaborate to trigger SG formation by controlling protein-protein interaction or the accumulation of untranslated mRNA in response to lysosomal damage. To understand the signaling mechanism responsible for the accumulation of untranslated mRNA, our study suggests a calcium-dependent pathway that induces untranslated mRNA for SG formation by controlling eIF2α phosphorylation. Thus, both pH and calcium-dependent pathways can collaboratively contribute to SG formation during lysosomal damage. Moreover, considering the central role of lysosomes as the main degradation center for diverse cellular components (Lawrence and Zoncu, 2019), and the recognition of lysosomal damage that can be sensed by various cellular mechanisms (Aits et al, 2015; Jia et al, 2022; Napolitano and Ballabio, 2016; Chrisovalantis Papadopoulos et al, 2017), the leakage of certain lysosomal contents or the activation of other lysosomal damage sensors may also contribute to the activation of PKR, eIF2α phosphorylation, or the regulation of SG formation.

Phosphorylation of eIF2α is a key event in SG formation as it causes the shutdown in global translation and the accumulation of untranslated mRNA, which triggers the phase separation, ultimately leading to SG formation (Ivanov et al, 2019; Riggs et al, 2020). However, there are instances of SG formation that occur independently of eIF2α phosphorylation, potentially regulated by translational shutdown through the mTORC1 pathway (Emara et al, 2012; Fujimura et al, 2012). Nevertheless, this does not appear to be the case for SG formation in response to lysosomal damage. Our data indicate that upon lysosomal damage, eIF2α phosphorylation is the primary driver for SG formation, though the impact of mTORC1 inactivation on translation shutdown and SG formation cannot be entirely ruled out. Importantly, the uncoupled relationship between mTORC1 inactivation and eIF2α phosphorylation in SG formation may be attributed to their differential impacts on protein translation events and mRNA entry into SGs. For example, mTORC1 inactivation primarily inhibits the translation pre-initiation, while eIF2α phosphorylation can impede the recruitment of the large ribosomal subunit to mRNA (Holz et al, 2005; Jackson et al, 2010). Recent research suggests that having just one large ribosomal subunit on mRNA is enough to prevent the recruitment of mRNA into SGs, while extended ribosome-free regions on mRNA are insufficient for SG formation (Fedorovskiy et al, 2023). Thus, mTORC1 inactivation may result in ribosome-free regions on mRNA, but alone, it is insufficient to prompt mRNA entry into SGs. The prevention of large ribosomal subunits on mRNA through eIF2α phosphorylation appears to be a crucial factor triggering this process and contributing to SG formation in the context of lysosomal damage. In addition, through the examination of SG formation in galectin knockout cells, we recently showed (Jia et al, 2022) that galectin-8 does not influence SG formation. This finding supports the premise that eIF2α phosphorylation and mTORC1 inactivation are dissociated events during lysosomal damage, as we have previously reported that galectin-8 can modulate mTORC1 activity under similar conditions (Jia et al, 2018). Recent research has highlighted lysosomes as pivotal hubs in metabolic signaling, involving mTORC1 and AMPK pathways (Carroll and Dunlop, 2017; Jia et al, 2018; Jia et al, 2020b; Zoncu et al, 2011). While PKR and eIF2α activation can occur in various cellular locations, our findings on eIF2α phosphorylation regulation on damaged lysosomes, combined with our earlier observations of mTORC1 inactivation on damaged lysosomes (Jia et al, 2018), suggest a novel role for lysosomes as central command centers in orchestrating protein translation signaling during stress conditions.

The understanding of how SGs contribute to cell survival during stress, especially in the context of lysosomal damage, remains limited. A recent report highlights the reparative role of SGs through their association with damaged lysosomes (Bussi et al, 2023). This finding aligns with our prior research; however, in our study, we observed SGs at a distance from damaged lysosomes (Jia et al, 2022). Our observation challenges the notion of SGs primarily serving as plugs and suggests a broader spectrum of roles for SGs in response to lysosomal damage. Given the significance of SG formation in supporting cell survival during lysosomal damage, as reported here, it is highly likely that SGs undertake multiple tasks in restoring cellular homeostasis for survival. For example, considering SGs sequester non-translating mRNA (Khong et al, 2017), they may play roles in protecting mRNA and controlling mRNA fate of the transcriptome during lysosomal damage. Moreover, SG formation intersects with the integrated stress response (ISR), which can optimize the cell response by reprogramming gene expression to promote cellular recovery (Pakos-Zebrucka et al, 2016). The impact of SG formation on ISR may also enhance cellular fitness. In addition, the involvement of SGs in various cellular processes, e.g., intracellular transport dynamics, ribosome biogenesis, and cell signaling (Gorsheneva et al, 2024; Ripin et al, 2023; Zhang et al, 2024), may further contribute to cell survival upon lysosomal damage.

Recognizing lysosomal damage as a critical internal physiological trigger for SGs highlights the importance of enhancing our understanding of SG formation in disease contexts. We detected the role of SG formation in cell survival within disease-specific contexts using a series of pathological reagents to induce lysosomal damage. Given the strong association of these reagents with both lysosomal damage and SG formation, delving into the molecular mechanisms governing the interaction between lysosomal damage and SGs may provide valuable insights for future therapeutic efforts.

Methods

Reagents and tools table

| Reagent/Resource | Reference or Source | Identifier or Catalog Number |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Models cell lines | ||

| U2OS WT and ΔΔG3BP1/2 | (Kedersha et al, 2016) | N/A |

| U2OS Flp-In | This study | N/A |

| hMDM (human peripheral blood monocyte-derived macrophages) | This study | N/A |

| U2OS G3BP1-GFP PKRKO | This study | N/A |

| HEK293T | ATCC | CRL-3216 |

| HEK293T-TMEM192-2xFLAG | This study | N/A |

| HEK293T-TMEM192-3xHA | This study | N/A |

| THP-1 | THP-1 | TIB-202 |

| HEK293T-APEX2-eIF2α | This study | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLJC5-TMEM192-3xHA | Addgene | #102930 |

| pLJC5-TMEM192-2xFLAG | Addgene | #102929 |

| pCMV-VSV-G | Addgene | #8454 |

| psPAX2 | Addgene | #12260 |

| pOG44 | This work | N/A |

| eIF2α1 | Addgene | #21807 |

| eIF2α2 | Addgene | #21808 |

| pDEST-FLAG-G3BP1 | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-G3BP2 | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP-G3BP1 | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-Flp-G3BP1-GFP | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-RagB | (Jia et al, 2018) | N/A |

| pDEST- FLAG-RagBQ99L | (Jia et al, 2018) | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP-eIF2α | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-eIF2α | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-eIF2ΑS51A | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-PKR | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-Myc-PKR | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP-PKR | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP-PKRK60A&K150A | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-ALIX | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-ALG2 | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP-PACT | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-PACT | This work | N/A |

| pDEST-FLAG-Gal3 | (Jia et al, 2020c) | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP-Gal3 | (Jia et al, 2020c) | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP-Gal3R186S | (Jia et al, 2020c) | N/A |

| pDEST-GFP-ORF3a | This work | N/A |

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit Phospho-eIF2α (Ser51) | Cell Signaling Technology | #9721 |

| Rabbit eIF2α | Cell Signaling Technology | #9722 |

| Rabbit Phospho-p70 S6 Kinase (Thr389) (108D2) | Cell Signaling Technology | #9234 |

| Rabbit p70 S6 Kinase (49D7) | Cell Signaling Technology | #2708 |

| Rabbit Phospho-4EBP1(Ser65) | Cell Signaling Technology | #9451 |

| Rabbit 4EBP1 | Cell Signaling Technology | #9644 |

| Rabbit TFEB | Cell Signaling Technology | #4240 |

| Rabbit Phospho-ULK1 (Ser757) | Cell Signaling Technology | #6888 |

| Rabbit ULK1 (D8H5) | Cell Signaling Technology | #8054 |

| Rabbit GST (91G1) | Cell Signaling Technology | #5475 |

| Rabbit PKR | Cell Signaling Technology | #3072 |

| Rabbit PACT (D9N6J) | Cell Signaling Technology | #13490 |

| Mouse Myc (9B11) | Cell Signaling Technology | #2276 |

| Rabbit mTOR (7C10) | Cell Signaling Technology | #2983 |

| Rabbit ATF4(D4B8) | Cell Signaling Technology | #11815 |

| Rabbit G3BP2 | Cell Signaling Technology | #31799 |