Abstract

Systematic crises may disrupt well‐designed nutrition interventions. Continuing services requires understanding the intervention paths that have been disrupted and adapting as crises permit. Alive & Thrive developed an intervention to integrate nutrition services into urban antenatal care services in Dhaka, which started at the onset of COVID‐19 and encountered extraordinary disruption of services. We investigated the disruptions and adaptations that occurred to continue the delivery of services for women and children and elucidated how the intervention team made those adaptations. We examined the intervention components planned and those implemented annotating the disruptions and adaptations. Subsequently, we detailed the intervention paths (capacity building, supportive supervision, demand generation, counselling services, and reporting, data management and performance review). We sorted out processes at the system, organizational, service delivery and individual levels on how the intervention team made the adaptations. Disruptions included decreased client load and demand for services, attrition of providers and intervention staff, key intervention activities becoming unfeasible and clients and providers facing challenges affecting utilization and provision of services. Adaptations included incorporating new guidance for the continuity of services, managing workforce turnover and incorporating remote modalities for all intervention components. The intervention adapted to continue by incorporating hybrid modalities including both original activities that were feasible and adapted activities. Amidst health system crises, the adapted intervention was successfully delivered. This knowledge of how to identify disruptions and adapt interventions during major crises is critical as Bangladesh and other countries face new threats (conflict, climate, economic downturns, inequities and epidemics).

Keywords: global health implementation research, infant and young child nutrition, intervention disruptions and adaptations, maternal, urban antenatal care services

An urban nutrition intervention delivering essential services for women and children during a major health system crisis in Dhaka, Bangladesh, endured outstanding disruptions at system, organizational, service delivery and individual levels. The intervention team adapted to continue all intervention components by incorporating original activities that were feasible and adapted activities.

Key messages

Well‐designed nutrition interventions may be disrupted by crises that affect the interventions themselves and the platforms on which they run.

Combining contextualized expertise in operational settings with a data‐driven decision‐making process can facilitate the timely identification of intervention disruptions and enable swift adaptations.

Continuity of nutrition services amidst crises is feasible by adopting hybrid modalities including both original and adapted implementation paths.

Visualizing adaptations to the intervention paths sheds light on how to deliver nutrition services during major systematic disruptions.

Knowledge of how to adapt nutrition interventions during crises is critical going forward to respond successfully in future disruptive events.

1. INTRODUCTION

Major disruptions in nutrition interventions can occur during systematic crises caused by climate events, armed conflicts, disease outbreaks or other major disruptive events (Gaffey et al., 2020; Sánchez, 2018; WHO Regional Office for South‐East Asia, UNICEF, UNFPA, 2020). Even well‐designed and well‐executed interventions can be severely disrupted by crises that affect the interventions themselves and the platform on which they run (Avula et al., 2022; Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021). When disruptions due to major systematic crises occur, continuing service delivery requires understanding the intervention paths that have been disrupted and adapting in response to those disruptions as crises permit (Aarons et al., 2012; WHO Regional Office for South‐East Asia, UNICEF, UNFPA, 2020). This may also occur within a well‐established government system. Service continuity modalities may vary and could include restoring the original intervention paths, working around those original paths that become unfeasible once crises hit, bringing in alternative intervention paths, or adopting a hybrid intervention modality of original and alternative/new paths (Aarons et al., 2012; National Nutrition Services, Institute of Public Health Nutrition & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2020; WHO Regional Office for South‐East Asia, UNICEF, UNFPA, 2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic is one example of a major crisis that has caused systematic disruptions of essential health and nutrition services worldwide, including Bangladesh (WHO, 2022).

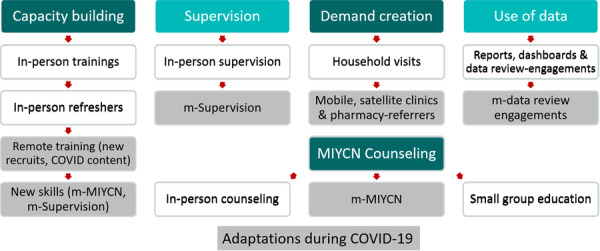

Alive & Thrive (A&T) is a global nutrition initiative to save lives, prevent illness and ensure healthy growth and development through improved maternal, infant and young child nutrition (Alive & Thrive, n.d). In 2019, A&T used its previous learnings (Sanghvi et al., 2022) and conducted formative research (Hasan et al., 2023) to develop an intervention to integrate maternal, infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) services into urban antenatal care (ANC) health services in Dhaka. The intervention aimed to address the high burden of malnutrition, the low coverage and the suboptimal quality of nutrition services in urban Bangladesh. The intervention was delivered by two experienced nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), Radda Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning Centre (RADDA) and Marie Stopes Bangladesh (MSB). RADDA and MSB are privately funded international organizations that deliver primary and comprehensive services independently. They are under the oversight of the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS) in Bangladesh. These NGOs each operated four facilities delivering urban health services in Dhaka. The intervention team comprised A&T, the two NGOs, and eight health facilities. The intervention sought to increase the use of services for women and children and to improve nutrition practices (Nguyen et al., 2023). Figure 1 shows the urban MIYCN intervention timeline.

Figure 1.

Urban maternal, infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) intervention timeline.

The original design of the intervention included components of capacity building, demand creation and MIYCN counselling (inter‐personal communication [IPC] as the core element of a social and behaviour change strategy). In alignment with the global recommendations on ANC nutrition services (WHO, 2016), IPC and MIYCN counselling focused on improving maternal diet and infant and young child feeding (IYCF) practices, the promotion and intake of iron‐folic‐acid (IFA) and calcium supplements, and weight measurements of mothers during ANC to monitor weight gain. The intervention also included strategic use of monitoring data (Alive & Thrive, 2014) for decision‐making and performance improvement (monitoring data and other data sources used are listed in the next section). Provision of the required equipment, tools and materials was a vital intervention process. At the facility level, the intervention included intensive capacity building, monitoring, data management, performance review and workforce strengthening by adding an MIYCN counsellor in each facility. At the community level, the community mobilization component of the intervention included home visits, community events led by community workers (CW) and phone follow‐up by the MIYCN counsellors (MC). MIYCN counselling was set to complete a minimum of 9 facility‐based contacts per client of 14 potential contacts over the first 1000 days (period from the start of the pregnancy until the young child is 2 years of age). The number of minimum contacts was set to be achieved by clients utilizing the counselling opportunities for improving practices on maternal nutrition, breastfeeding and complementary feeding (Nguyen et al., 2023). The MC, by design, were assigned two roles: follow‐up via phone calls and MIYCN counselling during facility‐based contacts.

The intervention, originally set for 2 years, started right at the onset of COVID‐19 in March 2020 (Figure 1). The intervention undertook measures to mitigate disruptions at system, organizational, service delivery and individual levels (described in the results section). These measures allowed to continue essential health services during crises by early identification of disruptions and incorporating timely adaptations at all levels built and contextualized from global, regional and country recommendations, with many important lessons emerging during the COVID‐19 response. The Bangladesh urban nutrition intervention provides an opportunity to (1) investigate the disruptions and adaptations that occurred to continue the delivery of services for women and children and (2) elucidate how the intervention team made those adaptations.

2. METHODS

For this study, disruption means an intervention interruption as the total or partial discontinuance of the intervention components, changes in the real or perceived needs the intervention was set to address, alterations in the platform through which the intervention functions and disturbances to providers and clients directly affecting their ability to deliver and utilize the intervention as originally designed. Adaptation means 'to make fit an intervention by modification for a specific or new use or situation' (Aarons et al., 2012; Greenhalgh et al., 2004) which comprises the use of recommendations to suit local conditions and situational awareness for incorporating modifications as crises evolve (WHO Regional Office for South‐East Asia, UNICEF, UNFPA, 2020). This work postulates that during crises, disruptions occur at system, organizational, service delivery and individual levels (WHO Regional Office for South‐East Asia, UNICEF, UNFPA, 2020). Continuity of service delivery is possible amidst a rapidly changing context by incorporating timely adaptations at these four levels in ways that disruptions are addressed strategically as these emerge on a day‐to‐day basis (Aarons et al., 2012). In this case, investigating the delivery of essential urban health and nutrition services in Dhaka, the four levels were system (i.e., the government and international organizations normative function and provision of guidelines); organizational (i.e., the A&T Initiative and the two implementing NGOs RADDA and MSB managing and contracting the provision of services); service delivery (i.e., the eight health facilities managing the workforce and delivering health and MIYCN services); and individuals (i.e., the service providers and clients who were pregnant and lactating women, PLW). These levels aligned with those in the framework of Alive & Thrive for achieving nutrition behaviour change at scale (Sanghvi et al., 2016), which employed the socio‐ecological model of behaviour change (McLeroy et al., 1988).

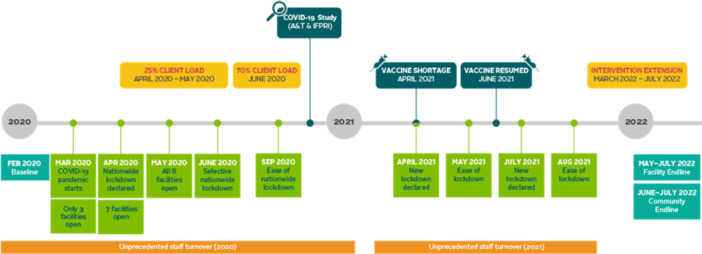

The intervention team (health facilities, NGOs, and A&T) utilized both qualitative and quantitative data (not shown) to monitor the intervention, understand the implications of the crises and make informed decisions. They tracked components of the intervention including capacity building, demand creation, service delivery and MIYCN counselling; data‐use; and supervision using monitoring tools (Table 1). In response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, additional monitoring included data on lockdowns, restrictions, guidelines, staff turnover, workforce, changes in client behaviour (e.g., fear among PLW and service providers), budget implications and environmental changes (e.g., rising food prices). The intervention team used multiple sources to stay informed about crisis impacts and the societal and environmental changes in the intervention areas. These sources included COVID‐19 studies, one study by the coauthors (Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021) and studies by others, and rapid situation reports tracking impacts of the pandemic on external food value chain, market dynamics and food security (FAO, 2020a; FAO, 2020b; FAO and IRRI, 2020; FAO, World Fish and GCIAR, 2020; IERDC and ICCDRB USAID and BMGF, 2020). A snapshot of the COVID‐19 and intervention monitoring data summary is shown in Figure 2.

Table 1.

Strategic use of data and MLE tools for the urban nutrition intervention.

| Tool | Name of tool | User | Frequency of use | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | MIYCN Counselor's Register | MIYCN Counselor | Daily |

|

| 2. | Group Education Register* | MIYCN Counselor | As required |

|

| 3. | Mobile Phone Communication Logbook | MIYCN Counselor and others as needed | Daily |

|

| 4. | MIYCN Counselor's Monthly Report | MIYCN Counselor | Monthly |

|

| 5. | Community Worker's Register | Community Worker | Daily |

|

| 6. | Demand Generation for MIYCN Counseling | Program Manager | As needed |

|

| 7. | Community Worker's Monthly Report | Community Worker | Monthly |

|

| 8. | Facility Assessment Checklist on MIYCN Services |

All managers (NGOs and A&T) |

Monthly |

|

| 9. | Supportive Supervision Checklist‐Community Level |

All managers (NGOs and A&T) |

Weekly |

|

| 10. | Monthly Progress Report on MIYCN services | Program Manager and A&T | Monthly |

|

| 11. | Disruptions due to COVID‐19 Monthly Report** | Program Manager, A&T and BMGF | Monthly |

|

| 12. | Quarterly Narrative Report | Program Manager and A&T | Quarterly |

|

| 13. | MIYCN Registration Card | Pregnant and lactating women (PLW) | As needed |

|

| 14. | MIYCN Counseling Quality Checklist | Program Manager and MLE staff | Weekly |

|

Group activities were discontinued during the three COVID‐19 waves, including group counselling sessions.

Report added in response to COVID‐19.

Figure 2.

COVID‐19 and intervention monitoring monthly reports.

To investigate the disruptions and adaptations that occurred to continue the delivery of services for women and children, the coauthors examined the core elements of the intervention as originally planned (Alive & Thrive, 2020) and as implemented, published elsewhere (Nguyen et al., 2023). Subsequently, the coauthors detailed the implementation process as an intervention implementation path by showing each of the intervention components (capacity building, supportive supervision, demand generation, MIYCN counselling services and reporting, data management and performance review) and identifying which elements were maintained as planned and which were adapted.

To elucidate how the intervention team made the adaptations, the coauthors sorted out processes at system, organizational, service delivery and individual levels, annotating the adaptation process conducted for all the intervention components that continued as hybrid modalities including both original and adapted implementation paths as feasible amidst an extraordinary evolving situation. The co‐authors followed an iterative process (IJzerman et al., 2023) involving regular technical‐team discussions on intervention status, progress, challenges and way forward. Throughout the intervention period, biweekly programme discussions were held involving the co‐authors and technical teams supporting Bangladesh, which prioritized the urban intervention. Additionally, the first author facilitated biweekly discussions with the A&T Bangladesh Monitoring, Learning, and Evaluation team (MLE team), monthly discussions with the urban intervention evaluation partner (International Food Policy Research Institute, IFPRI) and monthly discussions with the Bangladesh MLE specialist supporting fieldwork to develop the implementation paths. The implementation paths underwent three rounds of teamwork for drafting, review and updates, including in‐country sensitization and review discussions among the A&T and NGO intervention teams. The process included periodic review and feedback from A&T MLE teams and IFPRI. Finally, the first author conducted a validation interview with the two NGO programme managers and the A&T Bangladesh senior urban and MIYCN programme coordinator about the overall process of data use and the adaptations for the continuation of the intervention.

2.1. Ethics statement

This publication used deidentified information from reports and did not require ethical approval from an institutional review board.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Nutrition intervention disruptions and adaptations that occurred to continue the delivery of services for women and children

3.1.1. System‐level disruptions and adaptations

The nutrition intervention started in March 2020, right at the onset of COVID‐19 (Figure 1). Lockdown focusing on social distancing measures was imposed by the government of Bangladesh on March 26, 2020, initially declared as a 10‐day general holiday and extended until May 30, 2020 (Shammi et al., 2021). By April, the food basket cost had increased by 5‐10%; employment, income, food expenditure and food consumption were negatively affected (Rahman et al., 2021). By May, the population was mostly relying on rice, potatoes and vegetables to feed their families and could not afford fruit, eggs, fish or meat (FAO, 2020a).

Essential preventive nutrition services seemed deprioritized among the general public but ANC, the platform through which the MIYCN intervention was delivered, remained relevant since ANC is an essential health service per Ministry of Health guidelines in Bangladesh. According to Government of Bangladesh orders, a ward (average population of 100,000) was declared a ‘red zone’ if it had more than 40 COVID‐19 cases. Red zones adopted a total mandatory lockdown with strict stay‐at‐home orders and people's movements restricted for 15‐day periods. Educational institutions, offices and factories were closed, and there were restrictions on going to mosques (Jo et al., 2021; Khan et al., 2018; The Daily Star, 2020a, 2020b). By June 2020, 75% of Dhaka city was designated as a ‘red zone’.

Government food assistance programmes halted or were reduced, and women were without jobs more than men (FAO, 2020b). The Bangladesh National Nutrition Services (NNS) released new Guidance for the Continuity Essential Nutrition Services during COVID‐19 (National Nutrition Services, Institute of Public Health Nutrition. & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2020) also applicable for NGOs, including the eight NGO‐run facilities delivering the urban MIYCN intervention. In July 2020, food prices continued to rise, widespread job losses and a decrease in purchasing power occurred, government food assistance stopped and serious impacts on the food system arose, including negative effects in the agricultural sector, changes in consumer behaviour and food intake (e.g., further reduced ability to purchase chicken, fish and eggs) and increased demand for cheap and suboptimal ‘less nutritious’ foods (FAO, World Fish and GCIAR, 2020; Wageningen University & Research, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition and CGIAR, 2020). By August, 9% of the population in Dhaka had contracted COVID‐19 and slum dwellers were disproportionately affected (IERDC and ICCDRB USAID and BMGF, 2020). COVID‐19 impacted the rice value chain as it increased costs and delayed the rice harvest; limited extension services led to decreased rice yield and quality (FAO and IRRI, 2020). The lentil value chain was also significantly impacted, with negative consequences for the urban poor (FAO, 2020c). By November, access to health care remained a continuous challenge with low adherence to safety measures and changing and unmet community information needs (BBC, 2020). By December 2020, due to COVID‐19‐related decreased family income, child labour and child marriage had increased with great potential consequences including negatively affecting young women's empowerment (Tauseef & Sufian, 2024). Adolescent girls experienced unmet needs regarding health and access to nutritious foods and IFA supplements (BBC, 2020).

From the start of the pandemic in March 2020, PLW were not visiting facilities unless for critical care. Client load dropped to 25% of normal client load pre‐COVID‐19. Facilities were mostly receiving high‐risk cases and some returning clients for receiving MIYCN counselling. The combined impact of the pandemic on food supply, transportation and livelihoods exacerbated food insecurity among intervention households (Alive & Thrive, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). The main issues the urban MIYCN intervention was designed to address were deprioritized by the general public and PLW as survival became the priority. The demand for the intervention MIYCN services deteriorated. PLW were directly affected in their ability to use MIYCN services and indirectly by overarching disruptions in their daily lives. The intervention adapted to address new issues while safeguarding its original focus by aligning and contributing to the government's new priorities, addressing the populations' perceived needs. For example, strengthening liaisons with other organizations delivering food aid support and advancing food assistance alternatives for PLW in slum areas of Dhaka City.

3.1.2. Organizational‐level disruptions and adaptations

The nutrition intervention experienced an unprecedented staff turnover. The attrition of the service delivery workforce disrupted the intervention. Issues with retention of service providers and staff occurred at all levels throughout the life of the intervention. MC and CW were greatly affected. Specifically, RADDA reported six resignations affecting two facilities, and MSB reported six resignations affecting three facilities. Reasons for resignations during COVID‐19 included concern about on‐the‐job risks, family emergencies, childcare duties, family pressures to leave the workforce, maternity leave and another job opportunity. The intervention adapted by incorporating a permanent intervention component to manage workforce turnover (recruitment, hiring and training). Due to high staff turnover, the recently hired MC and CW received peer‐to‐peer training from previously trained MC. Intervention staff positions and role assignments adapted to meet in‐office capacity mandates and continue activities with personnel available at a time. Additionally, national mandates to reduce in‐facility staff and restrictions for large group gatherings made key intervention activities unfeasible. For example, to limit in‐facility staff, MC and CW worked 3 days per week instead of the originally planned 6 days per week.

The intervention adapted by updating the providers' organizational structure and work calendars. On the days MC were not available, general counsellors (GC) provided services of MIYCN counselling. CW provided assistance to MC and conducted mobile MIYCN counselling (m‐MIYCN). The implications of this adaptation for MC included adding m‐MIYCN to their original roles of follow‐up via phone calls and MIYCN counselling during facility‐based contacts when feasible. The intervention team (A&T, NGOs and facilities) was personally affected by the crises. Personnel were exhausted; got sick; lost colleagues, friends and relatives; and faced challenges related to stay‐home orders, specifically with taking care of young children, elders and ill family members while working from home. Female personnel were especially affected by the reported reasons for resignation listed above. Teams adapted to be flexible, extend the implementation timeline (Figure 1), and allow leave and mental health days as needed. Role redistribution, team support and opportunities to share struggles were incorporated in routine work activities. Staff needs and struggles were prioritized while trying to keep up with intervention demands. The implementing team incorporated an adapted monitoring process including remote monitoring by using mobile technology, as part of the intervention component strategic use of data. The intervention team conducted data‐driven decision‐making through the intervention period to meet targets by innovating and adapting.

3.1.3. Service delivery‐level disruptions and adaptations

Some service delivery and related intervention components became partially unfeasible during the crisis. The Urban MIYCN intervention adapted to continue by incorporating hybrid modalities including both original activities that were feasible and adapted activities.

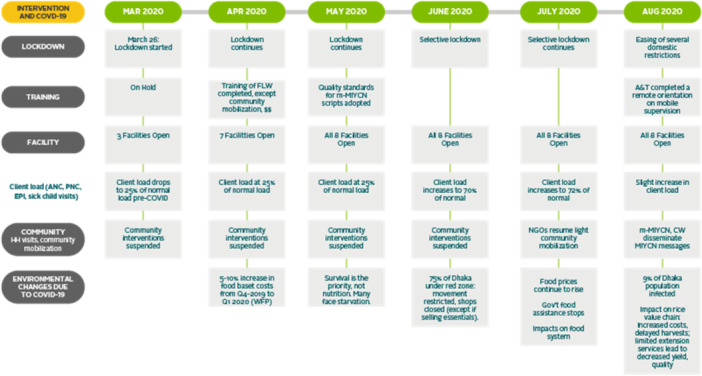

Capacity building (Figure 3) used the modalities of remote and in person when possible. Curricula contents were updated by incorporating new knowledge and skills (m‐MIYCN), remote monitoring and supervision through mobile phone, and crisis guidelines (government and organizational crises guidelines). Adapted virtual orientations, training and technical periodic refreshers were provided. Particularly, MC and CW were trained to complete updated roles, including telephone follow‐up with families that acknowledged and addressed challenges during crises, and provision of services as m‐MIYCN.

Figure 3.

Capacity building path (adaptations during COVID‐19 shown in grey boxes). A&T, Alive and Thrive; CW, community worker; FLW, frontline worker; FM, Facility Manager; FS, Field Supervisor; GC, general counsellor; MC, MIYCN Counsellor; MIYCN, maternal, infant and young child nutrition; PM, Programme Manager.

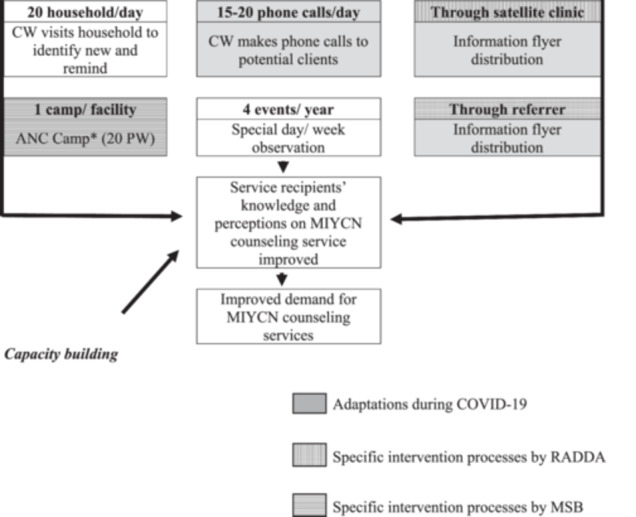

The demand generation strategy (Figure 4) via household visits (in person) became unfeasible. The adapted strategy used essential services facilities that remained open during lockdown and were receiving PLW (e.g., satellite clinics and pharmacies). The intervention team developed an MIYCN service information flyer to mobilize clients to facilities. The CW of RADDA distributed the flyers directly to the clients while visiting satellite clinics. CW of MSB distributed flyers via referrers including diagnostic centres, pharmacies and small clinics. The referrers further distributed flyers to potential new ANC clients when coming into contact with them (e.g., pregnant women or their kin visiting pharmacies during strict lockdown). Light community mobilization efforts included satellite clinic outreach (RADDA facilities only) and distribution of MIYCN flyers to community referrers (MSB facilities only) and monthly ANC camps for pregnant women (MSB facilities only). During strict lockdown and when home visits were not feasible, CW stayed positioned at the facility level and conducted mobile phone communications with the clients who were already registered in the system and recruited potential new clients for the intervention. Additionally, MC and CW continued to follow up with families and PLW via phone, as originally planned. Social mobilization, community events and group activities, as part of demand creation (Figure 4), were not feasible during the COVID‐19 waves. All community activities (local mass media campaigns, advocacy meetings, MIYCN fairs and film shows) were suspended. Events were substantially reduced to what was feasible, bringing community activities down to only four special events per year: Safe Motherhood Day, National Handwashing Day, National Nutrition Week and World Breastfeeding Week. Celebration modalities downgraded to only having a display of a banner, an online discussion, and a group discussion or demonstration when feasible.

Figure 4.

Demand generation path (adaptations during COVID‐19 shown in grey boxes, specific intervention processes by RADDA in vertical striped boxes, specific intervention processes by MSB in horizontal striped boxes). ANC, antenatal care; CW, community worker; MIYCN, Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition; PW, pregnant women. *ANC Camp: activity organized by partner NGO as an outreach service to provide antenatal care as part of routine maternal health service. MICYN community workers used the camp occasion to promote MIYCN services by informing and motivating women attending ANC Camps to receive ‘MIYCN counselling services’ in the nearby facility. ANC Camps occurred when feasible as part of demand‐generation activities.

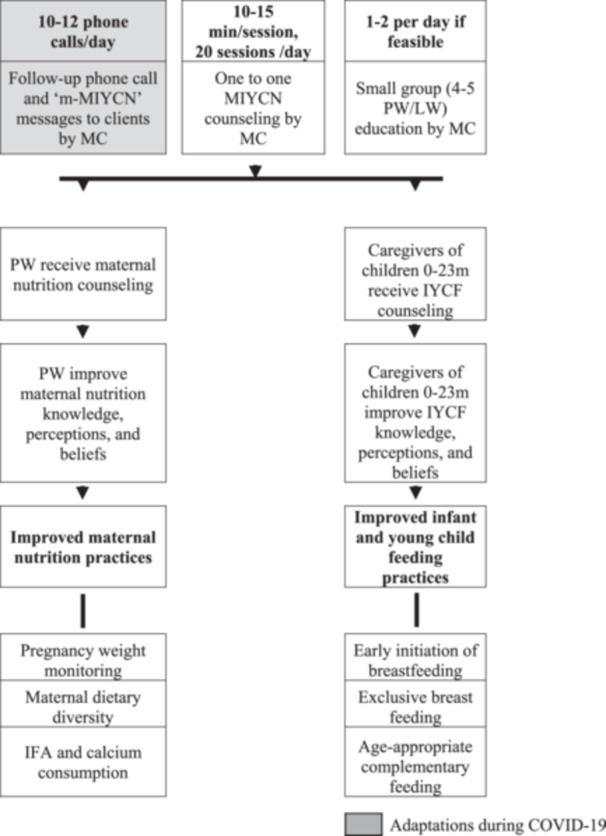

MIYCN counselling (Figure 5) was not feasible as originally planned due to health facilities client loads dropping as low as 25% of normal client loads before the pandemic. Upon the rollout of the adapted demand generation strategy described above, MC delivered via phone nutrition counselling services to PLW as m‐MIYCN and promoted the use of follow‐up counselling services in person at the facilities. MIYCN counselling follow‐up incorporated the use of mobile phones to give reminders about knowledge, practice, other information and the next visit. Counselling rooms set up and MIYCN counselling services in person at the health facilities occurred as per the original implementation guide (with the exception of group education) with the addition of messages in the context of COVID‐19. All group activities were discontinued. Social and behaviour change communication (SBCC) materials and job aids were updated to meet the updated intervention needs. For example, the intervention team developed a script for m‐MIYCN and for the use of the MIYCN flyer during demand generation activities.

Figure 5.

Maternal, infant and young child nutrition (MIYCN) counselling path (adaptations during COVID‐19 shown in grey boxes). IFA, iron and folic acid; IYCF, Infant and young child feeding; LW, lactating women; MC, MIYCN Counsellor; m‐MIYCN, Mobile Maternal, Infant and Young Child Nutrition counselling; PW, pregnant women.

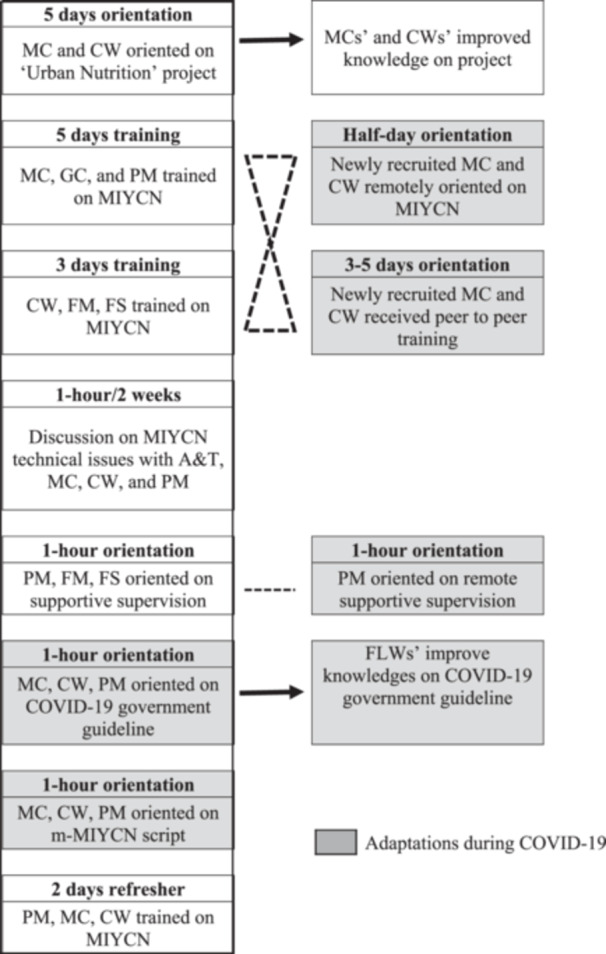

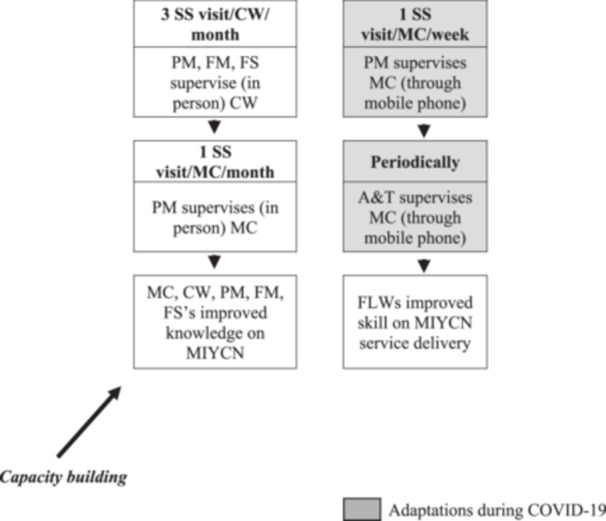

Supportive supervision (Figure 6) in person was not feasible. Remote and hybrid supervision were incorporated. Supervision included a modality for remote (mobile supervision) through which intervention managers supervised the MC through mobile phones using an updated checklist once per week. The remote supervision continued throughout the project implementation until in person was feasible. Supervisors periodically called the MC and CW.

Figure 6.

Supportive supervision (SS) path adaptations during COVID‐19 shown in grey boxes). A&T, Alive and Thrive; CW, community worker; FLW, frontline worker; FM, Facility Manager; FS, Field Supervisor; MC, MIYCN Counsellor; MIYCN, maternal, infant and young child nutrition; PM, Programme Manager.

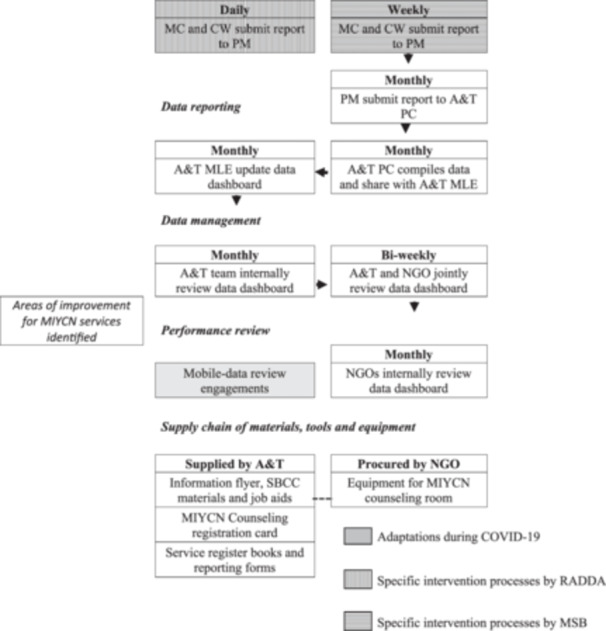

Strategic use of data as reporting, management and performance review (Figure 7) in person was not feasible; the intervention team incorporated the use of mobile phones for data review and problem‐solving. The original intervention (Alive & Thrive, 2020) had established a reporting, data management, and performance review process or strategic use of data (Alive & Thrive, 2014) using the tools listed in Table 1 and through which MC and CW compile daily performance data and challenges faced and share monthly with intervention and organizational managers and supervisors for overcoming or mitigating challenges, exchange feedback and advance performance improvement. A monthly report on the disruptions due to COVID‐19 was the only report added to the original intervention reports. This mechanism of strategic use of data facilitated incorporating during crises a constant process of identifying disruptions and operationalizing adaptations by addressing crises‐related challenges in the short term.

Figure 7.

Reporting, data management and performance review path (adaptations during COVID‐19 shown in grey boxes, specific intervention processes by Radda Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning Centre (RADDA) in vertical striped boxes, specific intervention processes by MSB in horizontal striped boxes). A&T, Alive and Thrive; CW, community worker; NGO, nongovernmental organization; MC, MIYCN counsellor; MIYCN, maternal, infant and young child nutrition; MLE, monitoring, learning and evaluation; PM, Programme Manager; SBCC, social behaviour change communication.

3.1.4. Individual‐level disruptions and adaptations

Service providers and PLW with specific characteristics and experiences faced multiple co‐occurring challenges. Our COVID‐19 study revealed that challenges among PLW included lack of transportation to health facility, scared to leave house, scared of getting infected at health facility, families did not want PLW to leave house and lack of access to personal protective equipment (PPE). Mothers reported sacrificing the consumption of preferred foods because of lack of resources (Alive & Thrive, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). Coping strategies included skipping meals, eating less desired foods or having smaller meals. Mothers reported devising ways to increase their income to buy food, including spending savings, reducing expenditures on other items or borrowing money from friends or relatives (Alive & Thrive, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). The intervention adapted by incorporating the promotion of food assistance alternatives and food aid support available for PLW from slum areas in Dhaka City. Providers also reported being scared to visit homes and no transportation (Alive & Thrive, 2021; Nguyen et al., 2021). Facilities adapted to provide ANC, IYCF and MIYCN counselling by phone, arranged immunization visits for children and used WhatsApp and phone text messages to communicate with mothers.

4. HOW THE INTERVENTION TEAM MADE THE ADAPTATIONS

The major health system crisis was faced by the intervention staff who conducted processes for the identification of disruptions and adaptations at four levels (Table 2). These levels included system (e.g., government of Bangladesh and international organizations norming and providing guidelines) organizational (e.g., A&T and NGOs—RADDA and MSB, managing and contracting the provision of services), service delivery (e.g., health facilities managing the workforce and providing health and MIYCN services) and individuals (e.g., health providers and PLW who were the users of services). The system level included mechanisms to receive, understand, incorporate crisis mandates, guidelines and recommendations and to perform collaborative work. The organizational level included crisis assessment and decision‐making early and short‐term, and constant mechanisms throughout the life of the project to repeat this process. Organizational‐level efforts also included local, specialized and connected resilient staff who were grounded and teamed up with country authorities. Critical organizational practices included flexibility and openness to update timelines and reset priorities amidst crises affecting staff and during which staff well‐being ought to be maximized. Service delivery level practices included identifying components disrupted and potential adaptations maximizing alignment with the intervention guide (Alive & Thrive, 2020) and standard operational procedures (e.g., nutrition counselling technique and contents) as well as meeting the minimum number of contacts (e.g., counselling delivered during early pregnancy, perinatal period and post‐delivery) and supportive supervision that effectively advances performance improvement of providers. The individual‐level practices comprised mechanisms for constant needs assessment maximizing the early identification of basic needs (e.g., food insecurity), physical needs (e.g., lack of transportation) and social barriers (e.g., fears and the changing and unmet community information needs). A snapshot of the COVID‐19 and intervention monitoring data summary used for adaptations is listed in Figure 2. For example, data revealed a significant initial decrease in facilities' client loads necessitating alternatives for demand generation, such as distributing flyers via pharmacies and satellite clinics instead of community activities and household visits. Additionally, data showed a sudden increase in food prices and food chain interruptions suggesting that MIYCN counselling would not suffice for PLW to adopt improved food intake practices. Intervention staff updated counselling contents by adding information on how to access and utilize food aid locally available for PLW in intervention areas.

Table 2.

System, organizational, service delivery and individual processes for the identification of disruptions and adaptations.

| Challenges due to the COVID‐19 pandemic | Disruption | Adaptation | Practices that advanced the urban MIYCN intervention adaptations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

System level: government and international organizations norming and providing guidelines |

Survival became the priority, all other issues, including essential preventive services, were deprioritized Lockdown and Dhaka city under the red zones Agricultural sector employment, income (with consequences on child labor and child marriage), food expenditure, food security and food consumption affected Dhaka and slum dwellers contracted COVID‐19 disproportionately |

Low client load and MIYCN services demand Healthcare showed low adherence to safety measures Changing and unmet community needs Exacerbated food insecurity among intervention households due to combined impacts of the pandemic on livelihoods, food supply, and transportation |

Adoption of new Guidance for the Continuity Essential Nutrition Services during COVID‐19 The intervention addressed new issues while safeguarding its original MIYCN focus by aligning and contributing to the government's new priorities, and addressing the populations’ perceived new priorities (e.g., liaison with those delivering food aid in slums areas of Dhaka City) |

System links and mechanisms established to receive, understand, and incorporate crises mandates, guidelines, recommendations and lessons Collaborative work among system actors including institutional and individual work relations Guidance for the Continuity Essential Nutrition Services during COVID‐19 was jointly developed by intervention staff, country partners, and global organizations supporting National Nutrition Services. These close collaborations allowed A&T to train service providers as soon as the Guidance was issued |

|

Organizational level: A&T and the two implementing NGOs, RADDA and MSB, managing and contracting the provision of services |

National mandates to reduce in‐facility staff and restrictions for large group gatherings |

Attrition of workforce, MIYCN Counselors and Community Workers were greatly affected Issues with retention of service providers and staff occurred at all levels The intervention team at all levels were personally affected by the crises Particular intervention staff positions and role assignments became unfeasible Portions of the intervention monitoring system became unfeasible Key intervention activities became unfeasible |

Incorporating a permanent intervention component to manage workforce turnover (recruitment, hiring, and training) New staff training modalities peer‐to‐peer training by previously trained counselors Update to all intervention staff positions, role assignments, organizational structure, and work calendars Team adapted to be flexible, extended timelines, and allowed leave and mental health days as needed Intervention monitoring and strategic use of data updated to include COVID‐19 domains and routine processes distilling short‐term actionable items Mechanisms for onboarding and working with new intervention allies (e.g., pharmacies and satellite clinics) |

Simplified purpose designed management (WHO, 2020) liaising system and intervention levels for receiving, understanding, and incorporating crises mandates, guidelines, recommendations and lessons Local, specialized, and connected resilient staff who were grounded/rotted and teamed up with national and local authorities Flexibility and openness to update timelines and reset priorities amidst crises indirectly and directly affecting staff at all levels. Staff wellbeing maximized Teams incorporated routine organizational processes for short‐term crises assessment and decision making Identifying the intervention components disrupted and recognizing adaptable characteristics of the intervention to be operationalized in the short‐term Financial restructuring and funds redistribution without additional funds |

|

Service delivery level: the eight health facilities managing the workforce and providing health and MIYCN services |

Some service delivery and related intervention components became partially unfeasible In‐person capacity building was not feasible Social mobilization, community events, and group activities were not feasible All community activities were suspended The demand generation strategy via household visits (in‐person) was not feasible During strict lockdown and when home visits were not feasible, Community Workers were unable to conduct activities as per the original intervention guide Supportive supervision in‐person was not feasible Strategic use of data (reporting, management, and performance review) in‐person was not feasible |

Hybrid capacity building via in‐person and virtual modalities with periodic refreshers; curricula contents updated by incorporating new knowledge and skills, and crises guidelines Social mobilization events reduced to what was feasible. Celebration modalities downgraded (banner, online discussion, and demonstration when feasible) The demand generation strategy used essential services facilities (satellite clinics and pharmacies) to reach PLW and distribute MIYCN services information flyers. Light community mobilization efforts included satellite clinic outreach, distribution of flyers via community referrers, and monthly ANC campsa Community Workers assigned with updated roles in‐facility to conduct mobile communications for demand generation, m‐MIYCN service delivery, and follow up of PLW Remote and hybrid supervision was incorporated, managers supervised MIYCN Counselors through mobile phones using an updated checklist The intervention team incorporated strategic use of data for data‐review and problem solving via mobile phones |

Continued perusal of adapted intervention paths as crises permitted with a ‘hybrid’ modality of original and alternative or new paths by going back and forth while facing three waves of COVID‐19 Intervention monitoring system updated to add the monthly tracking of COVID‐19 domains and adapted intervention components (e.g., mobile supportive supervision and m‐MIYCN counseling) Development of adapted intervention paths for all components as the ad‐doc roadmap by connecting inputs, outputs and outcomes addressing original and new priorities and visually showing the sequence of all intervention activities (Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7). |

|

|

Individual level: the service providers and clients as pregnant and lactating women (PLW) who were the users of services |

Service providers and PLW, with specific characteristics and experiences, faced multiple co‐occurring challenges | PLW challenges included lack of transportation to health facility, scared to leave house, scared of getting infected at health facility, families did not want mother/woman to leave house, and lack of access to PPE). Providers also reported being scared to visit homes and no transportation |

Facilities adapted to provide ANC, IYCF and MIYCN counseling by phone, arranged immunization visits for children, used WhatsApp and phone text messages to communicate with mothers The intervention was adapted by incorporating the promotion of food assistance alternatives and food aid support available for PLW from slum areas in Dhaka City |

Constant needs assessment maximizing needs were met or mitigated Continued and evolving action to address physical barriers (e.g., lockdown), basic needs (e.g., food insecurity), and social barriers (e.g., fears) Mechanisms for constant practice changes by discontinuing original practices that were not feasible and adopting updated, new and ‘hybrid’ practices |

ANC Camp: activity organized by partner NGO as an outreach service to provide antenatal care as part of routine maternal health service. MICYN community workers used the camp occasion to promote MIYCN services by informing and motivating women attending ANC Camps to receive ‘MIYCN counselling services’ in the nearby facility. ANC Camps occurred when feasible as part of demand‐generation activities.

5. DISCUSSION

The COVID‐19 pandemic disrupted health services worldwide (WHO, 2022). The urban MIYCN intervention in Bangladesh was also seriously disrupted (Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021). The continuation of essential health and nutrition services is credited to the intervention team (staff from A&T, the two implementing NGOs, and the eight health facilities) identifying disruptions and making real‐time adaptations at system, organization, service delivery and individual levels. This required early situation assessment, feasibility decisions, identification of adaptation opportunities by using the existing intervention organizational structure and update of all intervention components, which started by updating the capacity building curricula and tools to align with the adapted modalities of service delivery. The intervention in Bangladesh incorporated remote capacity building; m‐MIYCN counselling, remote supervision and demand creation for services via mobile phones; and community mobilization via satellite clinics and referrers. The intervention path used both original pre‐COVID‐19 and adapted intervention components.

This work has advanced our knowledge about the disruptions and adaptations that occurred to continue the delivery of essential services for women and children during a major health system crisis and has elucidated how the nutrition intervention team made those adaptations. This case in Bangladesh emphasizes the pivotal roles by the intervention staff, as the local experts, who used data strategically, collaborated with other in‐country partners, and capitalized on regional and global liaisons to distil and operationalize feasible alternative modalities for service delivery during crises. It was critical that all intervention adaptations followed the Bangladesh national guidelines and the global guidelines for health and nutrition services continuity during COVID‐19 (National Nutrition Services, Institute of Public Health Nutrition & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2020; WHO Regional Office for South‐East Asia, UNICEF, UNFPA, 2020). This work indicates that the identification of intervention disruptions and midcourse adaptations uses a dual process of contextualized expertise at work and data use for decision‐making. Contextualized expertise could be understood as a process led by country specialists in which the implemented strategies are adaptive to needs and opportunities as they arise (Hajeebhoy et al., 2013).

In the context of major crises, disruptions occur at the system, organizational, service delivery and individual levels (Gaffey et al., 2020; Sánchez, 2018; WHO Regional Office for South‐East Asia, UNICEF, UNFPA, 2020). In alignment with our experience in urban Bangladesh, others have reported system crises causing serious organizational‐level disruptions of staff shortages and staff mental health issues, among multiple other staff challenges in several countries, including rural Bangladesh, India, Somalia, Lebanon, Turkey, Italy, Germany, USA, UK, France, Ireland, Japan, Spain, Australia, Switzerland, China, Poland and other regions (Ahmad, 2021; Ahmed et al., 2021; Avula et al., 2022; Kang et al., 2022; Schmitt et al., 2021; Sinha et al., 2022). Service providers faced challenges at multiple levels upholding unprecedented responsibilities amidst the pandemic response while contending with ever‐present risks of getting infected, being exhausted, lacking essential PPE, facing moral and ethical dilemmas and encountering angry clients (Avula et al., 2022; Schmitt et al., 2021).

Adaptations at the organizational‐level among these cases also included staff restructuring measures and switching to virtual modalities for communication and training (Schmitt et al., 2021). Additionally, large organizational efforts were required to promote and support short‐term behaviour changes among health staff and clients (Ahmed et al., 2021).

At the service delivery‐level, similar to Bangladesh, others have reported disruptions like the interruptions of services (Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021), poor quality of services (Sinha et al., 2022), and general challenges to train personnel while meeting social distancing measures (Palmquist et al., 2020) and to deliver services that required proximity, such as those delivering services of nutrition counselling, child growth monitoring and immunization (Avula et al., 2022; Kang et al., 2022).

Adaptations by others have also included virtual education (Kang et al., 2022; Palmquist et al., 2020), excluding accompanying persons (Schmitt et al., 2021), social distancing and using PPE while delivering services in beneficiary homes, using telephones for communication (Avula et al., 2022; Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021), and the provision of ANC and nutrition counselling services over cell phones (Avula et al., 2022). In alignment with our experience in urban Bangladesh, the work by others (Kang et al., 2022) in rural Bangladesh—The Bangladesh Rajshahi Division of Maternal and Child Nutrition (BRDMCN; 2018–2020)—conducting SBCC together with an economic development of asset transfer component was scaled back due to the pandemic to reduce the frequency of activities as well as the number of participants, and incorporated virtual discussions (Kang et al., 2022).

At the individual‐level, others have also reported disruptions occurring widely among clients and providers. Like individual experiences in urban Bangladesh, clients in rural Bangladesh and India experienced feeling down, depressed, hopeless and fearful of contracting disease when visiting the health facility or during providers' household visits, lack of transportation and financial constraints (Kang et al., 2022; Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021; Sinha et al., 2022). Experiences in rural and urban Bangladesh have reported a substantial reduction in service utilization, including drops in facility visitations, health and nutrition counselling contacts, child weight measurements and immunizations (Kang et al., 2022; Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021). Others brought to attention disruptions in perinatal care services including limited access to breastfeeding education, skilled lactation support immediately post‐partum and counselling throughout the complete lactation period (Palmquist et al., 2020). Different from our experience in Bangladesh, additional challenges emerged in Lebanon such as the lack of internet access for clients (Ahmad, 2021), which further exacerbated service utilization disruptions in the context of efforts to improve infant and young child feeding in emergencies. Like with providers in Bangladesh, providers in Lebanon faced an increase in workload and the need for additional resources (Ahmad, 2021); providers in India faced fears, inadequate PPE, manpower shortages that challenged service provision, limited transportation and the need to walk long distances, and antagonistic behaviour of clients (Avula et al., 2022; Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021).

An example of adaptations by others in Lebanon to address disruptions among clients included educators and lactation specialists mobilized to scale up awareness raising and one‐to‐one and group counselling, both remotely and in person with infection prevention control measures in place, and a national hotline (Ahmad, 2021). This experience particularly differs from ours in urban Bangladesh, where all in person group activities were discontinued during the three COVID‐19 waves. In alignment with our adaptation practices in rural Bangladesh, others reported that providers' challenges were mitigated by incorporating social distancing, using PPE, telephones for communication (Avula et al., 2022; Nguyen, Sununtnasuk, et al., 2021) and the provision of services over cell phones (Ahmad, 2021; Avula et al., 2022).

The urban MIYCN intervention strengthening services in health facilities was a key work stream under A&T's overarching efforts in Bangladesh aimed at improving urban nutrition outcomes, bringing about strategic liaisons among key country partners and global organizations. In addition to the urban MIYCN intervention team (A&T lead agency and the NGOs RADDA and MSB implementing partners), the government and partners were leading national efforts in Bangladesh to advance urban health which were leveraged for a short‐term interorganizational response when crises occurred. Other government offices included the National Nutrition Services (NNS), the Institute of Public Health Nutrition, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, and the Ministry of Local Government, Rural Development & Cooperatives (MoLGRD&C), which operates the Urban Primary Health Care Services Delivery Project (UPHCSDP). Global partners included the World Bank, FAO, WFP, UNICEF and WHO. An example of how liaisons among intervention staff, in country partners and global organizations enabled to continue nutrition services is the jointly developed national ‘Nutrition Essential Services Continuity Guidelines during COVID‐19 Pandemic’ (National Nutrition Services, Institute of Public Health Nutrition. & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2020). Partners worked together during the early stages of the pandemic to support NNS to rapidly prepare the national guidelines that were issued by July 2020. The guidelines were operationalized in real‐time into the adapted urban MIYCN intervention model with specific guidelines on the nutrition services delivery at different levels (e.g., facilities and communities), service delivery modalities and key messages for pregnant women, breastfeeding mothers and caregivers of young children. The guidelines also established recommended practices in relation to essential supplies, coordination among relevant platforms and sectors, and monitoring and reporting (National Nutrition Services, Institute of Public Health Nutrition. & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2020).

In urban Bangladesh, our adapted intervention integrating nutrition into ANC services was successfully delivered with two thirds of recently delivered women (RDW) receiving ANC during the first trimester and three fourths receiving ≥4 ANC check‐ups (Nguyen et al., 2023). Our quasi‐experimental evaluation showed adequate weight gain (44 pp) and recorded appropriate child feeding (27 pp). Other impacts included the number of food groups consumed (DID: 1.1 food groups) and minimum dietary diversity (23 pp). The intervention had no impact on IFA and calcium consumption during pregnancy. Impacts occurred as improvements on early initiation of breastfeeding (20 pp), exclusive breastfeeding (45 pp), introduction of solid or semisolid foods (28 pp), and egg and/or flesh food consumption (33 pp) among children. Minimum dietary diversity and acceptable diet remained low (Nguyen et al., 2023). The intervention was shown to be a feasible model for addressing the urban health gap and for improving nutrition services coverage and key MIYCN practices (Nguyen et al., 2023). This MIYCN intervention case implemented by NGO‐run facilities proved that flexibility and adaptability are critical during crises. This flexibility and adaptability could potentially be challenging for health facilities operating within complex bureaucracies that may limit agility to make short‐term real‐time decisions during crises. This knowledge of how to identify disruptions and adapt interventions during major system crises is critical as countries face global conflicts, climate extremes, economic downturns, wealth inequities and threats of other epidemics. In such crises, the uninterrupted delivery of high‐quality essential health and nutrition services is fundamental to preserve lives and maximize well‐being. Leveraging these learnings can potentially prevent setbacks due to crises and speed progress on reaching the Sustainable Development Goals 2030 targets, specifically those under goal 2, to create a world free of hunger and food insecurity; and goal 3, to ensure healthy lives and promote well‐being for all at all ages (United Nations, 2015; United Nations, 2023).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jessica Escobar‐DeMarco conceptualized the manuscript, compiled and analysed information and wrote the manuscript. Phuong Nguyen and Edward A. Frongillo provided extensive input in the manuscript conceptualization and drafts. Jessica Escobar‐DeMarco and Gourob Kundu conceptualized Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Gourob Kundu created initial Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, 7. Gourob Kundu, Rowshan Kabir, Mohsin Ali, Santhia Ireen, Deborah Ash, Zeba Mahmud, and Celeste Sununtnasuk provided extensive input in the revised manuscript. All coauthors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Coauthors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful for the contributions of Alive & Thrive FHI 360 staff from the Bangladesh country office, the South Asia team and the Washington, DC, and Durham, NC, offices in the United States. We acknowledge the contributions from the Bangladesh country field teams from the nongovernmental organizations and health facilities, Radda Maternal and Child Health and Family Planning Centre (RADDA) and Marie Stopes Bangladesh (MSB). We are grateful for the contributions of users, pregnant and lactating women, and providers of services for women and children. The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1170427, INV‐006546) funded this work through the Alive & Thrive Initiative managed by FHI 360.

Escobar‐DeMarco, J. , Nguyen, P. , Kundu, G. , Kabir, R. , Ali, M. , Ireen, S. , Ash, D. , Mahmud, Z. , Sununtnasuk, C. , Menon, P. , & Frongillo, E. A. (2025). Disruptions and adaptations of an urban nutrition intervention delivering essential services for women and children during a major health system crisis in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 21, e13750. 10.1111/mcn.13750

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

REFERENCES

- Alive & Thrive . (n.d.) About us. https://www.aliveandthrive.org/en/about-us

- Aarons, G. A. , Green, A. E. , Palinkas, L. A. , Self‐Brown, S. , Whitaker, D. J. , Lutzker, J. R. , Silovsky, J. F. , Hecht, D. B. , & Chaffin, M. J. (2012). Dynamic adaptation process to implement an evidence‐based child maltreatment intervention. Implementation Science, 7(1), 32. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, B. (2021). Infant and young child feeding in emergencies: Programming adaptation in the context of COVID‐19 in Lebanon. Field Exchange, 65, 57–59. www.ennonline.net/fex/65/iycfecovid19lebanon [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, S. M. , Hussein, B. O. , & Barasa, E. (2021). Adapting infant and young child feeding interventions in the context of COVID‐19 in Somalia. Field Exchange, 65, 54–56. www.ennonline.net/fex/65/iycfecovid19somaliahttps://www.ennonline.net/attachments/3970/FEX-65-Web_01June2021-Final_54-56.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alive & Thrive . (2014). Strategic use of data as a component of a comprehensive program to achieve IYCF at scale. Alive & Thrive Initiative. https://www.aliveandthrive.org/sites/default/files/attachments/Program-brief-Strategic-use-of-data.pdf

- Alive & Thrive . (2020). Implementation Guide for Delivering MIYCN Counseling Services in Urban MNCH Services Setting in Bangladesh. Alive & Thrive. [Google Scholar]

- Alive & Thrive . (2021). Nutrition and Food Insecurity during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: The impact of the pandemic on MIYCN services in India and Bangladesh. https://www.aliveandthrive.org/en/resources/nutrition-and-food-insecurity-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-the-impact-of-the-pandemic-on-miycn

- Avula, R. , Nguyen, P. H. , Ashok, S. , Bajaj, S. , Kachwaha, S. , Pant, A. , Walia, M. , Singh, A. , Paul, A. , Singh, A. , Kulkarni, B. , Singhania, D. , Escobar‐Alegria, J. , Augustine, L. F. , Khanna, M. , Krishna, M. , Sundaravathanam, N. , Nayak, P. K. , Sharma, P. K. , … Menon, P. (2022). Disruptions, restorations and adaptations to health and nutrition service delivery in multiple states across India over the course of the COVID‐19 pandemic in 2020: an observational study. PLoS One, 17(7), e0269674. 10.1371/journal.pone.0269674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BBC . (2020). Media Action; Corona Kotha Issue 14, December 03, 2020.

- FAO . (2020a). Impact of COVID‐19 on food security & urban poverty. Situation Report, 13, 21–27. May and June, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO . (2020b). Leveraging the potential of Dhaka's wet markets to support food security and livelihoods, November 8, 2020.

- FAO . (2020c). The impact of COVID‐19 on the lentil value chain. Value Chain Report 3, August, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO and IRRI . (2020). The impact of COVID‐19 on the rice value chain. Value Chain Report 4, August, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, World Fish and GCIAR . (2020). The impact of COVID‐19 on the aquaculture value chain Value chain report 2, July, 2020.

- Gaffey, M. F. , Ataullahjan, A. , Das, J. K. , Mirzazada, S. , Tounkara, M. , Dalmar, A. A. , & Bhutta, Z. A. (2020). Researching the delivery of health and nutrition interventions for women and children in the context of armed conflict: lessons on research challenges and strategies from BRANCH consortium case studies of Somalia, Mali, Pakistan and Afghanistan. Conflict and Health, 14(2020), 69. 10.1186/s13031-020-00315-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajeebhoy, N. , Rigsby, A. , McColl, A. , Sanghvi, T. , Abrha, T. H. , Godana, A. , Roy, S. , Phan, L. T. H. , Vu, H. T. T. , Sather, M. , & Uddin, B. (2013). Developing evidence‐based advocacy and policy change strategies to protect, promote, and support infant and young child feeding. Food and Nutrition Bulletin, 34(3_Suppl.), S181–S194. 10.1177/15648265130343S205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh, T. , Robert, G. , Macfarlane, F. , Bate, P. , & Kyriakidou, O . (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. Milbank Quarterly, 2(4), 581–629. 10.1111/2Fj.0887-378X.2004.00325.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, A. M. R. , Selim, M. A. , Anne, F. I. , Escobar‐DeMarco, J. , Ireen, S. , Kappos, K. , Ash, D. , & Rasheed, S. (2023). Opportunities and challenges in delivering maternal and child nutrition services through public primary health care facilities in urban Bangladesh: A qualitative inquiry. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 1172. 10.1186/s12913-023-10094-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IERDC and ICCDRB USAID and BMGF . (2020). Study of the course of COVID among Dhaka city dwellers. 2020.

- IJzerman, R. V. H. , van der Vaart, R. , Breeman, L. D. , Arkenbout, K. , Keesman, M. , Kraaijenhagen, R. A. , Evers, A. W. M. , Scholte Op Reimer, W. J. M. , & Janssen, V. R. (2023). An iterative approach to developing a multifaceted implementation strategy for a complex ehealth intervention within clinical practice. BMC Health Services Research, 23(1), 1455. 10.1186/s12913-023-10439-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo, Y. , Baik, Y. , Shrestha, S. , Pennington, J. , Gomes, I. , Reja, M. , Islam, S. , Roy, T. , Hussain, H. , & Dowdy, D. (2021). Sub‐district level correlation between tuberculosis notifications and socio‐demographic factors in Dhaka city corporation, Bangladesh. Epidemiology and Infection, 149, e209. 10.1017/S0950268821001679 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y. , Kim, H. , Hossain, M. I. , Biswas, J. P. , Lee, E. , Ruel‐Bergeron, J. , & Cho, Y. (2022). Adaptive implementation of a community nutrition and asset transfer program during the COVID‐19 pandemic in rural Bangladesh. Current Developments in Nutrition, 6(5), nzac041. 10.1093/cdn/nzac041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S. I. , Khan, A. , Sarker, N. I. , Huda, N. , Zaman, R. , Nurullah, A. , & Rahman, Z. (2018). Traffic congestion in Dhaka city: suffering for city dwellers and challenges for sustainable development. European Journal of Social Sciences, 57(1), 116–127. http://www.europeanjournalofsocialsciences.com/

- McLeroy, K. R. , Bibeau, D. , Steckler, A. , & Glanz, K. (1988). An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Education Quarterly, 15(4), 351–377. 10.1177/109019818801500401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Nutrition Services, Institute of Public Health Nutrition. & Ministry of Health and Family Welfare . (2020). Guidance Document for Continuity of Nutrition Services during COVID‐19 Pandemic.

- Nguyen, P. H. , Kachwaha, S. , Pant, A. , Tran, L. M. , Walia, M. , Ghosh, S. , Sharma, P. K. , Escobar‐Alegria, J. , Frongillo, E. A. , Menon, P. , & Avula, R. (2021). COVID‐19 disrupted provision and utilization of health and nutrition services in uttar pradesh, India: insights from service providers, household phone surveys, and administrative data. The Journal of Nutrition, 151(8), 2021. 10.1093/jn/nxab135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P. H. , Sununtnasuk, C. , Christopher, A. , Ash, D. , Ireen, S. , Kabir, R. , Mahmud, Z. , Ali, M. , Forissier, T. , Escobar‐DeMarco, J. , Frongillo, E. A. , & Menon, P. (2023). Strengthening nutrition interventions during antenatal care improved maternal dietary diversity and child feeding practices in urban Bangladesh: results of a quasi‐experimental evaluation study. The Journal of Nutrition, 153(10), 3068–3082. 10.1016/j.tjnut.2023.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, P. H. , Sununtnasuk, C. , Pant, A. , Tran, L. M. , Kachwaha, S. , Ash, D. , Ali, M. , Ireen, S. , Kappos, K. , Escobar‐Alegria, J. , & Menon, P. (2021). Provision and utilisation of health and nutrition services during COVID‐19 pandemic in urban Bangladesh. Maternal & child nutrition, 2021, e13218. 10.1111/mcn.13218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmquist, A. E. L. , Parry, K. C. , Wouk, K. , Lawless, G. C. , Smith, J. L. , Smetana, A. R. , Bourg, J. F. , Hendricks, M. J. , & Sullivan, C. S. (2020). Ready, set, BABY live virtual prenatal breastfeeding education for COVID‐19. Journal of Human Lactation, 36(4), 614–618. 10.1177/0890334420959292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, H. Z. , Matin, I. , Banks, N. , & Hulme, D. (2021). Finding out fast about the impact of Covid‐19: the need for policy‐relevant methodological innovation. World development, 140, 105380. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M. V. (2018). Climate impact assessments with a lens on inequality. The Journal of Environment & Development, 27(3), 267–298. 10.1177/1070496518774098 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi, T. , Haque, R. , Roy, S. , Afsana, K. , Seidel, R. , Islam, S. , Jimerson, A. , & Baker, J. (2016). Achieving behaviour change at scale: Alive & Thrive's infant and young child feeding programme in Bangladesh. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 1(suppl 1), 141–154. 10.1111/mcn.12277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanghvi, T. , Nguyen, P. H. , Ghosh, S. , Zafimanjaka, M. , Walissa, T. , Karama, R. , Mahmud, Z. , Tharaney, M. , Escobar‐Alegria, J. , Landes Dhuse, E. , & Kim, S. S. (2022). Process of developing models of maternal nutrition interventions integrated into antenatal care services in Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia and India. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 18(4), e13379. 10.1111/mcn.13379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, N. , Mattern, E. , Cignacco, E. , Seliger, G. , König‐Bachmann, M. , Striebich, S. , & Ayerle, G. M. (2021). Effects of the Covid‐19 pandemic on maternity staff in 2020—a scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1364. 10.1186/s12913-021-07377-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shammi, M. , Bodrud‐Doza, M. , Islam, A. R. M. T. , & Rahman, M. M. (2021). Strategic assessment of COVID‐19 pandemic in Bangladesh: comparative lockdown scenario analysis, public perception, and management for sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 23(4), 6148–6191. 10.1007/s10668-020-00867-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha, B. , Dudeja, N. , Mazumder, S. , Kumar, T. , Adhikary, P. , Roy, N. , Rongsen Chandola, T. , Mehta, R. , Raina, N. , & Bhandari, N. (2022). Estimating the impact of COVID‐19 pandemic related lockdown on utilization of maternal and perinatal health services in an urban neighborhood in Delhi, India. Frontiers in Global Women's Health, 3, 816969. 10.3389/fgwh.2022.816969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tauseef, S. , & Sufian, F. D. (2024). The causal effect of early marriage on women's bargaining power: Evidence from Bangladesh. The World Bank Economic Review, 2024, lhad046. 10.1093/wber/lhad046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- The Daily Star . (2020a). Covid‐19 red zones: Strict rules for stay at home. Retrieved December 19, 2023, from https://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/news/covid-19-red-zones-strict-rules-stay-home-1910813

- The Daily Star . (2020b). Covid‐19 pandemic: Govt plans to divide country into red, yellow, green zones. Retrieved December 19, 2023, from https://www.thedailystar.net/coronavirus-covid-19-pandemic-govt-plans-divide-country-red-yellow-green-zones-1907405

- United Nations . (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly, 42809, 1–13. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . (2023).The sustainable development goals report 2023: Special edition. United Nations Statistics Division. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023 [Google Scholar]

- Wageningen University & Research, Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition and CGIAR . (2020). Rapid country assessment: Bangladesh. The impact of COVID‐19 on the food system. Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health, July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- WHO . (2016). WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241549912 [PubMed]

- WHO . (2022). Third round of the global pulse survey on continuity of essential health services during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Interim report. Health Services Performance Assessment, WHO Headquarters (HQ) WHO. WHO/2019‐ nCoV/EHS_continuity/s urvey/2022.1. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/351527/WHO-2019-nCoV-EHS-continuity-survey-2022.1-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- WHO (Regional office for South‐East Asia), UNICEF, UNFPA . (2020). Continuing essential Sexual Reproductive, Maternal, Neonatal, Child and Adolescent Health services during COVID‐19 pandemic (2020). World Health Organization. Reference number SRMNCAH Covid. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1275295/retrieve [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.