Abstract

Objective

Steroidogenic factor-1 (SF1) neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus play key roles in the regulation of food intake, body weight and glucose metabolism. The bile acid receptor Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) is expressed in the hypothalamus, where it determines some of the actions of bile acids on food intake and body weight through still poorly defined neuronal mechanisms. Here, we examined the role of TGR5 in SF1 neurons in the regulation of energy balance and glucose metabolism.

Methods

We used a genetic approach combined with metabolic phenotyping and molecular analyses to establish the effect of TGR5 deletion in SF1 neurons on meal pattern, body weight, body composition, energy expenditure and use of energy substrates as well as on possible changes in glucose handling and insulin sensitivity.

Results

Our findings reveal that TGR5 in SF1 neurons does not play a major role in the regulation of food intake or body weight under standard chow, but it is involved in the adaptive feeding response to the acute exposure to cold or to a hypercaloric, high-fat diet, without changes in energy expenditure. Notably, TGR5 in SF1 neurons hinder glucose metabolism, since deletion of the receptor improves whole-body glucose uptake through heightened insulin signaling in the hypothalamus and in the brown adipose tissue.

Conclusions

TGR5 in SF1 neurons favours satiety by differently modifying the meal pattern in response to specific metabolic cues. These studies also reveal a novel key function for TGR5 in SF1 neurons in the regulation of whole-body insulin sensitivity, providing new insight into the role played by neuronal TGR5 in the regulation of metabolism.

Keywords: Bile acids, TGR5 receptor, SF1 neurons, Food intake, Glucose metabolism, Insulin sensitivity

Highlights

-

•

TGR5 in SF1 neurons favours satiety by modifying meal pattern responses to cold and high-fat diet.

-

•

These findings strengthen the general satietogenic role played by neuronal TGR5.

-

•

Loss of TGR5 in SF1 neurons heightens insulin signaling in the hypothalamus and brown adipose tissue.

-

•

Opposite to its action in the periphery, TGR5 in SF1 neurons hinders glucose metabolism.

1. Introduction

Bile acids (BA) are cholesterol-derived molecules produced by the liver to help digest fat during the meals. Beyond this classic function, BA exert hormone-like effects by acting both in peripheral organs [1] and, as recent studies have suggested [2,3], also in the brain to regulate body weight and participate in the pathophysiology of obesity [1]. BA act mainly through their binding to the nuclear Farnesoid X receptor and the membrane-bound G protein-coupled bile acid receptor 1 (Gpbar1), also known as the Takeda G protein-coupled receptor 5 (TGR5) [1]. Previous work investigating the action of BA in peripheral organs has shown for instance that BA-dependent activation of TGR5 in adipocytes favors browning and induces thermogenesis, participating in the regulation of body weight in mice [[4], [5], [6]]. Furthermore, TGR5 activation in the periphery improves glucose homeostasis by various mechanisms, such as the release of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) by intestinal L-cells [7,8] and pancreatic α-cells [9], and of insulin by pancreatic β-cells [10,11]. Consequently, TGR5 is considered a potential target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes [12].

Beyond the periphery, TGR5 is expressed in the hypothalamus [2,3,13,14], a major center of convergence and integration of nutrient and hormonal signals and of environmental cues, which participates in whole-body metabolic control [[15], [16], [17], [18]]. Recent studies we have carried out have shown that BA can reach the brain postprandially and activate a negative-feedback loop controlling satiety via hypothalamic TGR5 [2]. In other studies, we have demonstrated that hypothalamic BA-TGR5 signaling exert a protective action against obesity by engaging a top-down neural mechanism, with increased sympathetic activity promoting negative energy balance [3]. However, the role of TGR5 in specific hypothalamic neuronal populations remains understudied. TGR5 is expressed in different types of hypothalamic neurons [3]. Our work has revealed that satietogenic effects of BA require TGR5 in agouti-related peptide (AgRP) neurons, rather than in Pro-opio-melanocortin (POMC) neurons of the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus [2]. Whether TGR5 may modulate feeding by acting on other hypothalamic neuronal types is uncharted. In addition, although it is known that TGR5 improves glucose homeostasis through peripheral mechanisms [7,10,11], whether TGR5 may modulate whole-body glucose handling through its action in specific hypothalamic neurons, remains unknown.

Beyond AgRP and POMC neurons [2], TGR5 is also expressed in steroidogenic factor-1 (SF1; gene name Nr5a1) neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus (VMH) [3]. SF1 neurons participate to the regulation of energy balance and glucose homeostasis, as shown by a number of studies investigating the function of this neuronal population [[19], [20], [21], [22], [23], [24]]. For instance, SF1 neurons mediate the action of the hormone leptin on whole-body metabolism [[25], [26], [27]]. SF1 neurons also regulate sympathetic activity and brown adipose tissue thermogenesis [[28], [29], [30]] and play key roles in the regulation of glucose metabolism and the prevention of hypoglycemia, through glutamate release and other mechanisms [25,[31], [32], [33], [34], [35]]. Accordingly, recent work has shown that acute chemogenetic activation of SF1 neurons decreases food intake, while increasing energy expenditure and insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues [36].

By using a genetic approach combined with metabolic phenotyping, here we have investigated the role of TGR5 in SF1 neurons in the regulation of energy balance and glucose metabolism. Our findings reveal that TGR5 in this neuronal population does not play a major role in the regulation of food intake or body weight under standard chow, but it is involved in the adaptive feeding response to the acute exposure to cold or to a hypercaloric, high-fat diet (HFD). Notably, and opposite to its action in the periphery, TGR5 in SF1 neurons hinder glucose metabolism, since deletion of the receptor improves glucose handling through heightened insulin signaling in the hypothalamus and greater insulin sensitivity in peripheral organs.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

Experiments were conducted in strict compliance with the European Union recommendations (2013/63/EU) and ARRIVE guidelines and were approved by the French Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries and the local ethical committee of the University of Bordeaux. Maximal efforts were made to reduce the suffering and the number of animals used.

Conditional mutant mice lacking the TGR5 gene in SF1-positive cells (SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl) were generated by a three-step backcrossing method, as already described [37], crossing SF1-Cre mice [25,37] with mice carrying a loxP-flanked TGR5 allele [7]. All mice used were male littermates (Cre negative TGR5fl/fl were used as controls, hereafter called TGR5fl/fl) and were on a C57BL/6N genetic background. Mice were individually housed with enrichment at 22 °C ± 2 °C, with a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle (light off at 1400 h). Animals had ad libitum access to water and standard chow (Standard Rodent Diet A03, 3.2 kcal/g, SAFE, France) as well as to HFD (D12492, 5.24 kcal/g, Research Diets, USA) for specific studies. Number and ages of animals used for the different experiments are detailed in the paragraphs below.

2.2. Tissue collection

At the end of the experiments, mice were killed to obtain either fresh or perfused tissues, as described in the Supplementary Methods.

2.3. Stereotaxic surgery

Complete details for stereotaxic administration of a pAAV-hSyn-DIO-mCherry (Addgene, USA, #50459-AAV8) used to confirm the expression of the Cre recombinase in SF1 neurons of the VMH, are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

2.4. Single molecule fluorescent in situ hybridization (smFISH)

Description of smFISH of SF1 mRNA, to control that TGR5 deletion does not alter the number of SF1 neurons, is provided in the Supplementary Methods.

2.5. Body composition analysis, food intake and body weight

9 TGR5fl/fl and 17 SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl 7-9 weeks-old mice fed chow and 10 TGR5fl/fl and 9 SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl 9 weeks-old mice chronically fed a HFD were used to study body composition, food intake and body weight. In vivo assessment of lean and fat mass by nuclear echo magnetic resonance imaging whole-body composition analysis (EchoMRI 900; EchoMedical Systems, USA) was performed as in [3]. Food intake and body weight were recorded daily using a scale (OHAUS Scout SKX 1200 g/10 mg). Measurements were taken during the light phase.

2.6. Indirect calorimetry, locomotor activity and meal pattern analysis

9 TGR5fl/fl and 13 SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice were placed in individual metabolic cages (24 phenomaster cages, TSE Systems GmbH, Bad Homburg, Germany) where locomotor activity, food intake and gas exchanges were measured under controlled conditions of illumination, temperature and humidity [3]. O2 consumption and CO2 production were measured every 20 min to calculate the respiratory exchange ratio (RER= VCO2/VO2) and total energy expenditure (EE in kcal/h). In each cage, a basket of food and a bottle of water were attached to sensors that enabled continuous measurement of consumption. Locomotor activity was determined using an infrared system in the long axis of the cage, and body weight was measured every day. In general, the animals were fed a standard chow and maintained at 22 °C. To calculate basal metabolic rate, the housing temperature was increased to thermoneutrality (33 °C) for 2 days. Only the values measured on the light phase of the second day were used for the calculations of basal metabolic rate. To measure the response of mice to cold, the cage temperature was lowered to 4 °C for 24 h. To characterize the response to a hypercaloric diet, mice were fed a HFD for 24 h then returned to the standard chow diet. All interventions were made at the beginning of the nocturnal phase. Energy expenditure for physical activity (PAEE), thermic effect of food (TEF), cold-induced thermogenesis (CIT) and basal metabolic rate (BMR) were calculated as previously described [38]. Further details for these calculations are provided in the Supplementary Methods. Meal patterns were analyzed by defining a meal as the consumption of more than 0.03g of food, separated from the next feeding episode by at least 10 min [38]. Meal structures included the number of meals, meal size and intermeal interval (time difference between the end of one meal and the initiation of the next meal). The satiety ratio was calculated as the average intermeal interval divided by the average meal size [39] and food intake corresponded to the total consumption of food during the meals. Mice displaying a meal in which more than 0.4g of food was consumed were excluded, since it revealed food spillage. These mice were also excluded from the energy expenditure calculations. Since spillage can take place independently during the diurnal and nocturnal phase, number of animals can differ between figures showing diurnal and nocturnal energy expenditure and/or meal analysis.

2.7. Glucose tolerance test (GTT) and insulin tolerance test (ITT)

8 TGR5fl/fl and 13 SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl chow-fed mice (starting at 10 weeks old) were used. Blood samples were collected from the tail vein and glucose was measured using glucose strips (OneTouch, Vita, France). Plasma insulin was determined by ELISA kit (Mercodia 10-1132-01).

First, blood glucose and plasma insulin levels were determined in mice after a 5 h fast. These measurements were used to calculate the index of homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR).

For the GTT, mice were fasted for 5 h and injected i.p. with 2 g/kg lean mass of d-Glucose (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO). Blood glucose was measured at baseline, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min after the administration of glucose.

For the ITT, mice were fasted for 5 h and were injected i.p. with 0.75 U/kg lean mass of insulin (Umuline Rapide, Lilly, France). Blood glucose was measured at baseline, 10, 20, 30, 60, 90 and 120 min after the administration of insulin. The glucose disappearance rate (KITT) was calculated as the slope of the decreasing line of blood glucose levels over 30 min from insulin administration, as previously described [40,41].

An additional group of 10 TGR5fl/fl and 9 SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice underwent a GTT after 15 weeks of HFD. Mice were fasted overnight and injected i.p. with 1.5 g/kg lean mass of d-Glucose. Blood glucose was measured at baseline, 15, 30, 60 and 120 min after the administration of glucose.

2.8. Western blot

4 TGR5fl/fl and 7 SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl chow-fed mice were fasted for 5 h and received an i.p. injection of 2 g/kg lean mass of d-Glucose (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO), similarly to what previously done in [42]. 10 min later, they were killed and samples collected for the hypothalamus, liver, inguinal white adipose tissue (iWAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT). Details for western blot analysis are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

2.9. Assessment of Cre recombination by PCR

Perfused brain slices containing the VMH from 9 TGR5fl/fl and 8 SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice (27 weeks old) were genotyped by PCR to evaluate recombination in genomic DNA. Tissue from naïve C57BL/6J mice (wild type, WT) was used as a negative control. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

2.10. Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR)

Liver samples from chow-fed mice were homogenized in Tri-reagent (Euromedex, France). RNA was isolated using a standard chloroform/isopropanol protocol and purified by incubation with Turbo DNA-free (Fisher Scientific) [3]. Further details are provided in the Supplementary Methods.

2.11. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using the GraphPad Prism Software version 10.2.1 for Windows (La Jolla, CA, USA). Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. When comparing 2 groups, data were analyzed by an unpaired Student’s t-test (Shapiro–Wilk test for normality), or a Mann–Whitney U test (nonparametric). Glucose and insulin tolerance tests were analyzed by two-way repeated measures ANOVA considering treatment and time as factors. Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons tests were run when applicable for identifying differences amongst groups. Tests were considered significant when p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Role of TGR5 in SF1 neurons in the regulation of energy balance

SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl and their control TGR5fl/fl littermates were obtained through the use of classic cre/lox genetic recombination methodology and breeding strategy [7,25]. By using PCR, we then verified the presence of appropriate genetic recombination in the hypothalamus of SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice, which was absent in controls (Figure 1A). To further confirm the expression of the Cre recombinase in SF1 neurons of the VMH, SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice were also stereotaxically injected with a pAAV-hSyn-DIO-mcherry to label with red fluorescence (mcherry) Cre-expressing cells (Figure 1B). Besides, global distribution and number of SF1 positive cells was comparable in the VMH of SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice and their TGR5fl/fl littermates (Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

Deletion of TGR5 in SF1 neurons of the VMH does not affect body weight and food intake. (A) DNA gel image showing recombination in hypothalamic brain slices of SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice (n = 9) but not of control TGR5fl/fl mice (n = 10). Band around 1900 bp indicates TGR5fl/fl genotype, whilst the lower thinner band at 400 bp indicates recombination/TGR5 gene excision. H2O: negative loading control; WT: C57BL/6J mice as further control (band expected at 1730 bp). (B) Representative image showing that Cre-expressing cells (presence of red fluorescent mcherry) are present in the VMH in SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice injected with pAAV-hSyn-DIO-mcherry (scale bar: 100 μm; 3V: third ventricle; boundaries of tissue section were delineated). Mean body weight (C), fat mass (D), lean mass (E) and daily food intake (F) in 16 weeks old TGR5fl/fl (n = 9) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 17) mice fed with chow diet. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

SF1 neurons play a role in the regulation of food intake, body weight and energy expenditure [23,43,44], processes in which hypothalamic TGR5 has been recently involved [2,3]. We therefore investigated the impact of loss of TGR5 expression in SF1 neurons on these processes.

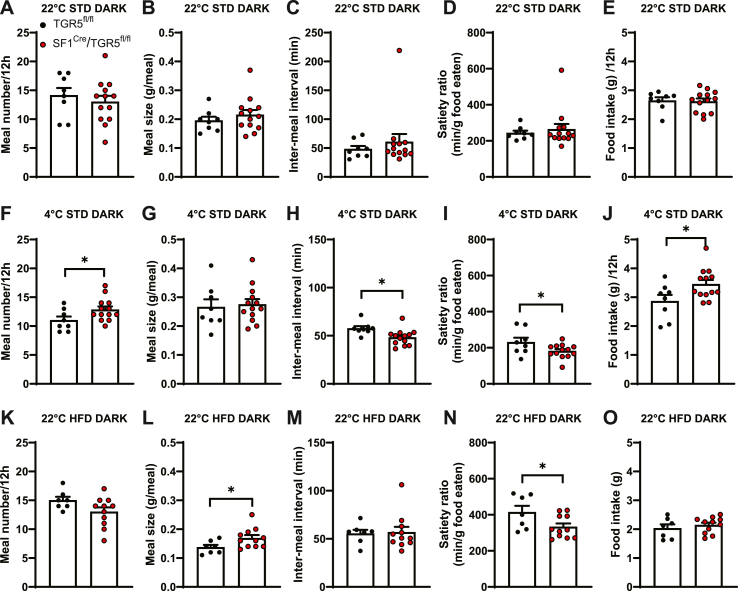

Under standard housing conditions (22 °C), chow-fed, male adult SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl and their control littermates did not show any difference in their body weight (Figure 1C), body composition (Figure 1D–E) or daily food intake (Figure 1F). Further investigation of meal patterns as well as of energy expenditure (including analysis of its different components PAEE, TEF, CIT and BMR), use of substrates in vivo through respiratory quotient analysis and of locomotor activity did not reveal any differences between genotypes, during either the nocturnal (Figure 2A–E, and Figure 3A–C) or the diurnal phases (Fig. S2A–E, and Fig. S3A–C).

Figure 2.

Acute cold or HFD exposure alters nocturnal meal patterns in mice with TGR5 deletion in SF1 neurons. Meal number (A, F, K), average meal size (B, G, L), average inter-meal interval (C, H, M), satiety ratio (defined as average inter-meal interval divided by average meal size; D, I, N) and total food intake (E, J, O) during the 12 h dark phase, respectively in TGR5fl/fl (n = 8) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 13) mice at 22 °C fed with STD (A–E), in TGR5fl/fl (n = 8) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 13) mice exposed to 4 °C for 24 h and fed with STD (F–J), and in TGR5fl/fl (n = 7) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 11) mice at 22 °C fed with HFD for 24 h (K–O). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. Unpaired t-tests or Mann–Whitney tests were carried out. ∗p < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Deletion of TGR5 in SF1 neurons does not affect nocturnal energy expenditure during a cold or HFD challenge. Components of energy expenditure in A, D and G with physical activity (PAEE; green), thermic effect of food (TEF; red), cold-induced thermogenesis (CIT; blue) and basal metabolic rate (BMR; grey) as well as respiratory exchange ratio (RER) in B, E and H and locomotor activity in C, F and I during the dark phase, respectively in TGR5fl/fl (n = 8) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 13) mice at 22 °C fed with STD (A–C), in TGR5fl/fl (n = 8) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 13) mice at 4 °C for 24 h and fed with STD (D–F), and in TGR5fl/fl (n = 7) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 11) mice at 22 °C fed with HFD for 24 h (G–I). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

We then evaluated whether acute metabolic challenges could modify any of the studied parameters.

As compared to control littermates, during exposure to cold (4 °C for 24 h), SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice increased the number of meals in the dark, active phase (Figure 2F), with no changes in meal size (Figure 2G). SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice also showed decreased inter-meal interval (Figure 2H) and satiety ratio (Figure 2I) with consequent increase in the 12 h food intake (Figure 2J). Thus, while the overall amount of food ingested was similar in each meal, suggesting preserved satiation, in response to cold, SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice had decreased satiety, as they ate more frequently, eating more in total (Figure 2J). Cold exposure did not reveal any genotype differences in the meal pattern during the light phase (Fig. S2 F-J) or in the different components of energy expenditure, use of energy substrates and locomotor activity during either the dark (Figure 3D–F) or light phases (Fig. S3 D-F).

The same analyses were then repeated by exposing SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice and their control littermates to a HFD for 24 h. During the dark phase, SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice fed a HFD showed an increase in meal size (Figure 2L) and a decrease in the satiety ratio (Figure 2N), as compared to control littermates, overall implying impaired satiation. However, there were no significant differences in the number of the meals (Figure 2K), in the inter-meal interval (Figure 2M) or in the total 12 h food intake (Figure 2O) between genotypes. While eating HFD, the 2 genotypes had also comparable meal pattern during the light phase (Fig. S2 K-O) and similar changes in the different components of energy expenditure, use of substrates and locomotor activity, in both the dark (Figure 3G–I) and the light phases (Fig. S3 G-I). Thus, TGR5 in SF1 neurons plays a different role in the regulation of the meal pattern depending on the specific metabolic demand.

3.2. Role of TGR5 in SF1 neurons in the regulation of glucose metabolism

Beyond energy balance, SF1 neurons play important roles in glucose metabolism [31,32,36,45]. Acute modulation of SF1 neurons through opto- or chemo-genetic approaches rapidly alters glycemic control, with effects on glycemia that seem related to the technique used and potential subgroup of SF1 neurons targeted [32,36]. In particular, chemogenetic activation of SF1 neurons decreases circulating glucose via an increased insulin-dependent uptake of glucose by peripheral tissues [36], while chemogenetic inhibition of SF1 neurons increases glucose levels during a GTT [33].

SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl and control chow-fed littermates had similar fasting glucose levels (Figure 4A). However, fasting plasma insulin was significantly decreased in SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice as compared to controls (Figure 4B), suggesting that genetic deletion of TGR5 from SF1 neurons may infer heightened sensitivity to the action of insulin. Accordingly, the HOMA-IR was significantly lower in SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice than in controls (Figure 4C). In agreement with these findings, dynamic tests of glucose metabolism showed that SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice had greater glucose tolerance to an i.p. injection of glucose (Figure 4D) and greater insulin sensitivity, as indicated by higher KITT (Figure 4F), during an ITT (Figure 4E). Based onto this evidence, we wondered whether loss of TGR5 expression in SF1 neurons confers higher sensitivity to the action of insulin in target organs. Accordingly, we found that peripheral administration of glucose rapidly (after 10 min) led to greater phosphorylation of the insulin receptor in the hypothalamus of SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice as compared to controls (Figure 4G), implying heightened activity of the insulin pathway in this brain structure. This was accompanied by greater phosphorylation of Akt, a critical molecular mediator of insulin signalling, in the BAT of SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice as compared to controls (Figure 4H), while no significant changes were observed in the iWAT (Figure 4I) and the liver (Figure 4J).

Figure 4.

Deletion of TGR5 in SF1 neurons improves glucose metabolism. (A–F) Blood glucose (A) and insulin (B) after 5 h fasting and related Homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR; C), glucose tolerance test (GTT; D), insulin tolerance test (ITT; E) and related glucose disappearance rate for ITT (KITT; F) in TGR5fl/fl (n = 8) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 13) mice. (G–J) Protein quantification of phosphorylated and total insulin receptor (pIR and IR, respectively) in the hypothalamus (G) and of phosphorylated and total Akt (pAkt and Akt respectively) in the BAT (H), iWAT (I) and liver (J) of TGR5fl/fl (n = 4) and SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl (n = 7) mice 10 min after glucose administration. Blots are shown to the left of each histogram. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. A repeated-measures two-way ANOVA (D and E) and a two-way unpaired t-test (A-C and F-J) were carried out. ∗p < 0.05.

In addition to modulating glucose uptake in peripheral organs like the BAT [36,46], activation of SF1 neurons regulate glucose production in the liver, by modulating hepatic gluconeogenesis among other responses [36]. Hence, we evaluated possible changes in response to glucose in the expression of gluconeogenesis markers in the liver, including glucose-6-phosphatase catalytic subunit 1 (G6Pase) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase 1, cytosolic (PEPCK), whose mRNA levels were however comparable between genotypes (Fig. S4A).

Thus, in chow-fed mice TGR5 in SF1 neurons may restrain the hypothalamic and peripheral action of insulin, thereby affecting whole-body glucose metabolism, without altering glucose and insulin-dependent responses in the liver.

Finally, chronic exposure to HFD led to comparable changes in body weight, fat mass and glucose metabolism in SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl and TGR5fl/fl mice (Figs. S4B–D), suggesting that once diet-induced obesity is established, TGR5 in SF1 neurons becomes dispensable for glucose control.

4. Discussion

In this study we have investigated the role of the BA receptor TGR5 in hypothalamic SF1 neurons, revealing that TGR5 in this neuronal population controls the feeding behaviour response to specific environmental challenges (change in external temperature, change in type of diet), which are known to impact this behaviour. Our work also details a key function for TGR5 in SF1 neurons in the regulation of whole-body insulin sensitivity.

Previous investigations have shown that BA, whose circulating and hypothalamic levels increase with the consumption of food [2,47], induce satiety by activating TGR5 expressed on vagal afferents [48] and on AgRP/NPY neurons, reducing the release of the orexigenic AgRP and NPY neuropeptides [2]. Earlier work has also shown that acute, chemogenetic activation of SF1 neurons at the onset of the dark reduces food intake, implying a role for this neuronal population in satiety [36]. Other studies have further demonstrated that SF1 neurons modulate the competing motivations of feeding and avoidance of potentially dangerous environments [44]. Our current findings expand the role of SF1 neurons in the regulation of food intake and specifically suggest that SF1 neurons are involved in the acute adaptation of feeding behaviour to cold and to HFD, with a key action of TGR5 under both conditions. More precisely, TGR5 in SF1 neurons favours satiety and satiation in response to cold and to HFD, respectively, whilst not altering feeding behaviour under non-stimulated conditions. Overall, these effects are in line with a general satietogenic role played by neuronal TGR5 [2,48] and are unrelated to potential changes in energy expenditure. Further studies are nevertheless required to define the underlying neuronal circuit driving these behavioural responses, with the recently identified VMH to paraventricular thalamus as potential candidate circuit involved [49].

This study also pinpoints a key role for TGR5 in SF1 neurons in controlling hypothalamic molecular sensitivity to the action of insulin, consequently affecting insulin sensitivity in the whole body. Previous work has illustrated a role for SF1 neurons in both the counterregulatory response to hypoglycemia [31,32,35] as well as in the increase in glucose utilization and insulin sensitivity in some peripheral tissues and in particular in the BAT via increased sympathetic activity [36,46,50]. These dichotomic actions exerted by SF1 neurons on the regulation of glucose homeostasis, favouring on one hand the increase in circulating glucose level and on the other its decrease, may be explained by the heterogeneous nature of this group of neurons in respect to their response to glucose. Indeed, this neuronal population includes glucose-responsive neurons that are either intrinsically or not intrinsically sensitive to changes in glucose. Among the intrinsically glucose sensitive neurons, a subset increases its electrical activity (commonly referred to glucose excited or GE neurons) and the other decreases its activity (commonly referred to glucose inhibited or GI neurons), as the glucose level changes [22,24]. Among the not intrinsically glucose sensitive VMH neurons, some are presynaptically excited in response to decreased extracellular glucose levels while some are presynaptically excited or inhibited in response to increased extracellular glucose [51,52]. Hypoglycemia-induced counterregulatory effects have been associated with changes in the activity of GI neurons [22,53]. Conversely, increased activity of GE SF1 neurons heightens insulin sensitivity in the periphery, through molecular mechanisms in SF1 cells involving glucose-dependent increased function of uncoupling protein 2 (UCP2) and mitochondrial fission [33]. Of note, we previously reported that TGR5 is only expressed in a subgroup of SF1 neurons [3]. This evidence, together with the above-mentioned studies and the insulin-sensitive phenotype we describe here would lead to suggest that TGR5 is expressed on GE neurons, where the BA receptor would hinder neuronal responses to glucose. Future electrophysiology studies are however needed to confirm that this is indeed the case. This would also imply that BA-TGR5 signalling in SF1 neurons counteracts the action of the hormone leptin acting on the same SF1 neurons to increase glucose uptake in peripheral organs [54]. Besides, the central action of BA-TGR5 signalling in SF1 neurons would in some ways offset the known beneficial effect of the same signalling pathway on glucose metabolism through its multiple actions in peripheral organs, including increasing glycolytic flux in the muscle [55] and stimulating the release of both GLP-1 and insulin [[7], [8], [9], [10], [11]]. The effects of the BA-TGR5 signalling on SF1 neurons may be therefore interpreted as a way for the BA-TGR5 system to fine-tune peripheral responses to these hormones. This role is however lost under diet-induced obesity, since lack of TGR5 in SF1 neurons is not anymore sufficient to modify responses to a GTT. Concerning the molecular mechanisms possibly mediating the action of TGR5 in SF1 neurons, it needs to be pointed out that, once activated, TGR5 recruits several different molecular pathways (e.g. PKA, ERK, mTOR, AMPK), membrane channels (such as KATP; [7,10]), and other intracellular signalling in a cell-type specific matter, modifying mitochondrial function and biogenesis and having an impact on intracellular use of substrates [56]. Based on this evidence, it is possible that TGR5 in SF1 neurons may modulate actual glucose sensing by modulating the glycolytic flux and function of associated enzymes, as shown in muscle [55] and by doing so, the action of insulin on its molecular targets, as effects of insulin on VMH neurons depend upon glucose concentration [57]. Besides, glucose sensing in the VMH requires AMPK and changes in the activity of this kinase are relevant for VMH-dependent effects on peripheral organs, and in particular on the BAT [28,58]. Activation of TGR5 can increase AMPK activity in certain types of cells in peripheral organs [59,60]. Thus, the metabolic phenotype described here in chow-fed mice may also be due to likely decreased activity of AMPK in SF1 neurons in the absence of TGR5.

Further studies are therefore necessary to provide greater understanding of the role of hypothalamic BA-TGR5 signalling and its molecular underpinnings in the regulation of whole-body glucose metabolism. Besides, SF1 neurons play sex-dependent roles in metabolism and behaviour [61,62]. Additional investigations will need to address the effects of BA-TGR5 signalling in female mice. Finally, although our neuroanatomical analysis did not reveal any alteration in the structure of the VMH or in the number of SF1 neurons in SF1Cre/TGR5fl/fl mice, it cannot be excluded at this time that the constitutive deletion of TGR5 may have affected some developmental aspects in SF1 neurons, possibly resulting in altered functioning of the circuitry regulating insulin sensitivity and food intake.

Collectively, our results highlight the relevance of studying the BA-TGR5 signalling in the brain to further grasp and pinpoint the different roles of this system in both physiology and pathology. Through better knowledge of the neuronal circuitry engaged by TGR5 and of the integration of these actions with the well-known peripheral effects of the receptor, may come better, more efficient ways to therapeutically target TGR5 and its signalling for the treatment of metabolic disorders, including obesity and type 2 diabetes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Philippe Zizzari: Software, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Ashley Castellanos-Jankiewicz: Investigation, Formal analysis. Selma Yagoub: Investigation, Formal analysis. Vincent Simon: Methodology, Investigation. Samantha Clark: Investigation. Marlene Maître: Investigation. Nathalie Dupuy: Investigation. Thierry Leste-Lasserre: Investigation. Delphine Gonzales: Investigation. Kristina Schoonjans: Resources. Valérie S. Fénelon: Writing – review & editing, Supervision, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Daniela Cota: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Supervision, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding sources

This work was supported by INSERM (D.C.), Nouvelle Aquitaine Region (D.C.), Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR-17-CE14-0007, ANR-18-CE14-0029, ANR-21-CE14-0018, ANR-10-EQX-008-1 OPTOPATH, to D.C.), University of Bordeaux’s IdEx ‘Investments for the Future’ program/GPR BRAIN_2030 (to D.C.), Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale, FRM-EQU202303016291 (D.C.) and by a PhD extension grant LabEX BRAIN (A.C-J.).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank the animal housing and genotyping facilities of INSERM U1215 Neurocentre Magendie, funded by INSERM, LabEX BRAIN ANR-10-LABX-43 and University of Bordeaux’s IdEx ‘Investments for the Future’ program/GPR BRAIN_2030 for animal care, genotyping and PCR studies. We thank E. Huc (INSERM U1215) for breeding and genotyping of our mice colonies. We also thank F. Corailler and R. Racunica (INSERM U1215) for animal care. We thank the biochemistry and biophysics facility of the Bordeaux Neurocampus funded by the LabEX BRAIN and GPR BRAIN_2030 for use of western blot equipment. We thank Dr G. Marsicano (INSERM U1215) for the kind gift of the pAAV-hSyn-DIO-mCherry.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molmet.2024.102071.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is/are the supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Perino A., Demagny H., Velazquez-Villegas L., Schoonjans K. Molecular physiology of bile acid signaling in health, disease, and aging. Physiol Rev. 2021;101(2):683–731. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00049.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perino A., Velázquez-Villegas Laura.A., Bresciani N., Sun Y., Huang Q., Fénelon V.S., et al. Central anorexigenic actions of bile acids are mediated by TGR5. Nat Metab. 2021;3(5):595–603. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00398-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Castellanos-Jankiewicz A., Guzmán-Quevedo O., Fénelon V.S., Zizzari P., Quarta C., Bellocchio L., et al. Hypothalamic bile acid-TGR5 signaling protects from obesity. Cell Metabol. 2021;33(7):1483–1492.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2021.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carino A., Cipriani S., Marchianò S., Biagioli M., Scarpelli P., Zampella A., et al. Gpbar1 agonism promotes a Pgc-1α-dependent browning of white adipose tissue and energy expenditure and reverses diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13102-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Velazquez-Villegas L.A., Perino A., Lemos V., Zietak M., Nomura M., Pols T.W.H., et al. TGR5 signalling promotes mitochondrial fission and beige remodelling of white adipose tissue. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):245. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Broeders E.P.M., Nascimento E.B.M., Havekes B., Brans B., Roumans K.H.M., Tailleux A., et al. The bile acid chenodeoxycholic acid increases human Brown adipose tissue activity. Cell Metabol. 2015;22(3):418–426. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomas C., Gioiello A., Noriega L., Strehle A., Oury J., Rizzo G., et al. TGR5-Mediated bile acid sensing controls glucose homeostasis. Cell Metabol. 2009;10(3):167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parker H., Wallis K., le Roux C., Wong K., Reimann F., Gribble F. Molecular mechanisms underlying bile acid-stimulated glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion: GPBA stimulation of L-cells. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;165(2):414–423. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar D.P., Asgharpour A., Mirshahi F., Park S.H., Liu S., Imai Y., et al. Activation of transmembrane bile acid receptor TGR5 modulates pancreatic islet α cells to promote glucose homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2016;291(13):6626–6640. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.699504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maczewsky J., Kaiser J., Gresch A., Gerst F., Düfer M., Krippeit-Drews P., et al. TGR5 activation promotes stimulus-secretion coupling of pancreatic β-cells via a PKA-dependent pathway. Diabetes. 2019;68(2):324–336. doi: 10.2337/db18-0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar D.P., Rajagopal S., Mahavadi S., Mirshahi F., Grider J.R., Murthy K.S., et al. Activation of transmembrane bile acid receptor TGR5 stimulates insulin secretion in pancreatic β cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;427(3):600–605. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.09.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bhimanwar R.S., Mittal A. TGR5 agonists for diabetes treatment: a patent review and clinical advancements (2012-present) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2022;32(2):191–209. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2022.1994551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doignon I., Julien B., Serrière-Lanneau V., Garcin I., Alonso G., Nicou A., et al. Immediate neuroendocrine signaling after partial hepatectomy through acute portal hyperpressure and cholestasis. J Hepatol. 2011;54(3):481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X.-Y., Zhang S.-Y., Hong Y.-Z., Chen Z.-G., Long Y., Yuan D.-H., et al. TGR5-mediated lateral hypothalamus-dCA3-dorsolateral septum circuit regulates depressive-like behavior in male mice. Neuron. 2024;112:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2024.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cota D., Proulx K., Seeley R.J. The role of CNS fuel sensing in energy and glucose regulation. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(6):2158–2168. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brüning J.C., Fenselau H. Integrative neurocircuits that control metabolism and food intake. Science. 2023;381(6665) doi: 10.1126/science.abl7398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waterson M.J., Horvath T.L. Neuronal regulation of energy homeostasis: beyond the hypothalamus and feeding. Cell Metabol. 2015;22(6):962–970. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Timper K., Brüning J.C. Hypothalamic circuits regulating appetite and energy homeostasis: pathways to obesity. Dise Model Mechan. 2017;10(6):679–689. doi: 10.1242/dmm.026609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fosch A., Zagmutt S., Casals N., Rodríguez-Rodríguez R. New insights of SF1 neurons in hypothalamic regulation of obesity and diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(12):6186. doi: 10.3390/ijms22126186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khodai T., Luckman S.M. Ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus neurons under the magnifying glass. Endocrinology. 2021;162(10):1–13. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hirschberg P.R., Sarkar P., Teegala S.B., Routh V.H. Ventromedial hypothalamus glucose-inhibited neurones: a role in glucose and energy homeostasis? J Neuroendocrinol. 2020;32 doi: 10.1111/jne.12773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shimazu T., Minokoshi Y. Systemic glucoregulation by glucose-sensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus (VMH) J Endocr Soc. 2017;1(5):449–459. doi: 10.1210/js.2016-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi Y.-H., Fujikawa T., Lee J., Reuter A., Kim K.W. Revisiting the ventral medial nucleus of the hypothalamus: the roles of SF-1 neurons in energy homeostasis. Front Neurosci. 2013;7:71. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Routh V.H. Glucose sensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus. Sensors. 2010;10(10):9002–9025. doi: 10.3390/s101009002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cardinal P., André C., Quarta C., Bellocchio L., Clark S., Elie M., et al. CB1 cannabinoid receptor in SF1-expressing neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus determines metabolic responses to diet and leptin. Mol Metabol. 2014;3(7):705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhillon H., Zigman J.M., Ye C., Lee C.E., McGovern R.A., Tang V., et al. Leptin directly activates SF1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body-weight homeostasis. Neuron. 2006;49(2):191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bingham N.C., Anderson K.K., Reuter A.L., Stallings N.R., Parker K.L. Selective loss of leptin receptors in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus results in increased adiposity and a metabolic syndrome. Endocrinology. 2008;149(5):2138–2148. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seoane-Collazo P., Roa J., Rial-Pensado E., Liñares-Pose L., Beiroa D., Ruíz-Pino F., et al. SF1-Specific AMPKa1 deletion protects against diet-induced obesity. Diabetes. 2018;67:2213–2226. doi: 10.2337/db17-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milbank E., Dragano N.R.V., González-García I., Garcia M.R., Rivas-Limeres V., Perdomo L., et al. Small extracellular vesicle-mediated targeting of hypothalamic AMPKα1 corrects obesity through BAT activation. Nat Metab. 2021;3(10):1415–1431. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00467-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim K.W., Zhao L., Donato J., Kohno D., Xu Y., Elias C.F., et al. Steroidogenic factor 1 directs programs regulating diet-induced thermogenesis and leptin action in the ventral medial hypothalamic nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(26):10673–10678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102364108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tong Q., Ye C., McCrimmon R.J., Dhillon H., Choi B., Kramer M.D., et al. Synaptic glutamate release by ventromedial hypothalamic neurons is part of the neurocircuitry that prevents hypoglycemia. Cell Metabol. 2007;5(5):383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meek T.H., Nelson J.T., Matsen M.E., Dorfman M.D., Guyenet S.J., Damian V., et al. Functional identification of a neurocircuit regulating blood glucose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113(14):E2073–E2082. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1521160113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toda C., Kim J.D., Impellizzeri D., Cuzzocrea S., Liu Z.-W., Diano S. UCP2 regulates mitochondrial fission and ventromedial nucleus control of glucose responsiveness. Cell. 2016;164(5):872–883. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang R., Dhillon H., Yin H., Yoshimura A., Lowell B.B., Maratos-Flier E., et al. Selective inactivation of Socs3 in SF1 neurons improves glucose homeostasis without affecting body weight. Endocrinology. 2008;149(11):5654–5661. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Borg W.P., During M.J., Sherwin R.S., Borg M.A., Brines M.L., Shulman G.I. Ventromedial hypothalamic lesions in rats suppress counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia. J Clin Invest. 1994;93(4):1677–1682. doi: 10.1172/JCI117150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coutinho E.A., Okamoto S., Ishikawa A.W., Yokota S., Wada N., Hirabayashi T., et al. Activation of SF1 neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus by DREADD technology increases insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. Diabetes. 2017;66(9):2372–2386. doi: 10.2337/db16-1344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bellocchio L., Soria-Gómez E., Quarta C., Metna-Laurent M., Cardinal P., Binder E., et al. Activation of the sympathetic nervous system mediates hypophagic and anxiety-like effects of CB 1 receptor blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(12):4786–4791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218573110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hassouna R., Zizzari P., Viltart O., Yang S.-K., Gardette R., Videau C., et al. A natural variant of obestatin, Q90L, inhibits Ghrelin’s action on food intake and GH secretion and targets NPY and GHRH neurons in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang L., Stengel A., Goebel M., Martinez V., Gourcerol G., Rivier J., et al. Peripheral activation of corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 2 inhibits food intake and alters meal structures in mice. Peptides. 2011;32(1):51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2010.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alquier T., Poitout V. Considerations and guidelines for mouse metabolic phenotyping in diabetes research. Diabetologia. 2018;61(3):526–538. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4495-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zizzari P., He R., Falk S., Bellocchio L., Allard C., Clark S., et al. CB1 and GLP-1 receptors cross talk provides new therapies for obesity. Diabetes. 2021;70(2):415–422. doi: 10.2337/db20-0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim J.D., Toda C., D’Agostino G., Zeiss C.J., DiLeone R.J., Elsworth J.D., et al. Hypothalamic prolyl endopeptidase (PREP) regulates pancreatic insulin and glucagon secretion in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(32):11876–11881. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim K.W., Sohn J.-W., Kohno D., Xu Y., Williams K., Elmquist J.K. SF-1 in the ventral medial hypothalamic nucleus: a key regulator of homeostasis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;336(1–2):219–223. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2010.11.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Viskaitis P., Irvine E.E., Smith M.A., Choudhury A.I., Alvarez-Curto E., Glegola J.A., et al. Modulation of SF1 neuron activity coordinately regulates both feeding behavior and associated emotional states. Cell Rep. 2017;21(12):3559–3572. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaneko K., Lin H.-Y., Fu Y., Saha P.K., De la Puente-Gomez A.B., Xu Y., et al. Rap1 in the VMH regulates glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest Insight. 2021;6(11) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.142545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sudo M., Minokoshi Y., Shimazu T. Ventromedial hypothalamic stimulation enhances peripheral glucose uptake in anesthetized rats. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metabol. 1991;261(3):E298–E303. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1991.261.3.E298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sonne D.P., Van Nierop F.S., Kulik W., Soeters M.R., Vilsbøll T., Knop F.K. Postprandial plasma concentrations of individual bile acids and FGF-19 in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metabol. 2016;101(8):3002–3009. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu X., Li J.-Y., Lee A., Lu Y.-X., Zhou S.-Y., Owyang C. Satiety induced by bile acids is mediated via vagal afferent pathways. JCI Insight. 2020;5(14) doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.132400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J., Chen D., Sweeney P., Yang Y. An excitatory ventromedial hypothalamus to paraventricular thalamus circuit that suppresses food intake. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6326. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20093-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Takahashi A., Sudo M., Minokoshi Y., Shimazu T. Effects of ventromedial hypothalamic stimulation on glucose transport system in rat tissues. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1992;263(6):R1228–R1234. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.263.6.R1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song Z., Levin B.E., McArdle J.J., Bakhos N., Routh V.H. Convergence of pre- and postsynaptic influences on glucosensing neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Diabetes. 2001;50(12):2673–2681. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hanna L., Kawalek T.J., Beall C., Ellacott K.L.J. Changes in neuronal activity across the mouse ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus in response to low glucose: evaluation using an extracellular multi-electrode array approach. J Neuroendocrinol. 2020;32(3) doi: 10.1111/jne.12824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fioramonti X., Song Z., Vazirani R.P., Beuve A., Routh V.H. Hypothalamic nitric oxide in hypoglycemia detection and counterregulation: a two-edged sword. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2011;14(3):505–517. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Minokoshi Y., Haque M.S., Shimazu T. Microinjection of leptin into the ventromedial hypothalamus increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues in rats. Diabetes. 1999;48:287–291. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sasaki T., Watanabe Y., Kuboyama A., Oikawa A., Shimizu M., Yamauchi Y., et al. Muscle-specific TGR5 overexpression improves glucose clearance in glucose-intolerant mice. J Biol Chem. 2021;296 doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.016203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lun W., Yan Q., Guo X., Zhou M., Bai Y., He J., et al. Mechanism of action of the bile acid receptor TGR5 in obesity. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2024;14(2):468–491. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2023.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Garcia S.M., Hirschberg P.R., Sarkar P., Siegel D.M., Teegala S.B., Vail G.M., et al. Insulin actions on hypothalamic glucose-sensing neurones. J Neuroendocrinol. 2021;33(4) doi: 10.1111/jne.12937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Martínez-Sánchez N., Seoane-Collazo P., Contreras C., Varela L., Villarroya J., Rial-Pensado E., et al. Hypothalamic AMPK-ER stress-JNK1 Axis mediates the central actions of thyroid hormones on energy balance. Cell Metabol. 2017;26(1):212–229.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang Q., Wang G., Wang B., Yang H. Activation of TGR5 promotes osteoblastic cell differentiation and mineralization. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:1797–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.08.093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang X.X., Edelstein M.H., Gafter U., Qiu L., Luo Y., Dobrinskikh E., et al. G protein-coupled bile acid receptor TGR5 activation inhibits kidney disease in obesity and diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;27(5):1362–1378. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014121271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cheung C.C., Krause W.C., Edwards R.H., Yang C.F., Shah N.M., Hnasko T.S., et al. Sex-dependent changes in metabolism and behavior, as well as reduced anxiety after eliminating ventromedial hypothalamus excitatory output. Mol Metabol. 2015;4(11):857–866. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2015.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu Y., Nedungadi T.P., Zhu L., Sobhani N., Irani B.G., Davis K.E., et al. Distinct hypothalamic neurons mediate estrogenic effects on energy homeostasis and reproduction. Cell Metabol. 2011;14(4):453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.