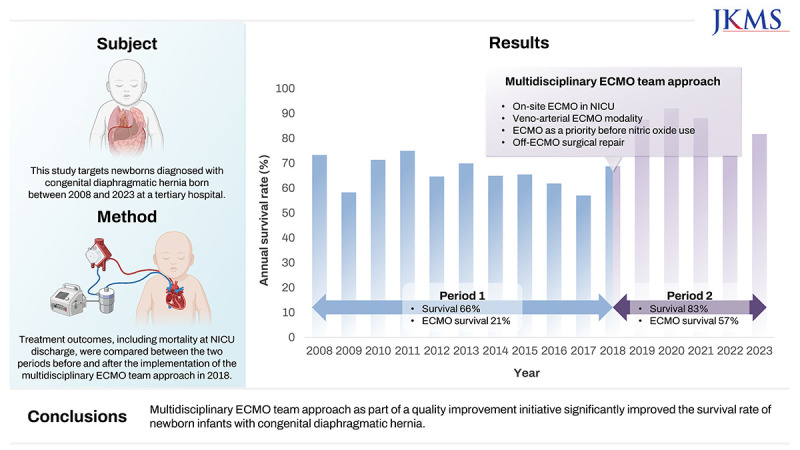

Abstract

Background

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is the only treatment option that can stabilize patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) with severe pulmonary hypertension. This study assessed the effects of a multidisciplinary ECMO team approach (META) as part of a quality improvement initiative aimed at enhancing the survival rates of neonates with CDH.

Methods

The medical records of infants with CDH treated at a tertiary center were retrospectively reviewed. Patients were categorized into two groups based on META implementation. The META group (P2) were given key interventions, including on-site ECMO management within the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), use of venoarterial modality, ECMO indication as a priority even before the use of inhaled nitric oxide, and preplanned surgery following ECMO discontinuation. These approaches were compared with standard protocols in the pre-META group (P1) to assess their effects on clinical outcomes, particularly in-hospital mortality.

Results

Over a 16-year period, 322 patients were included. P2 had a significantly higher incidence of non-isolated CDH and higher rate of cesarean section compared with P1. Moreover, P2 had delayed time to surgical repair (9.4 ± 8.0 days) compared with P1 (6.7 ± 7.3 days) (P = 0.004). The overall survival rate at NICU discharge was 72.7%, with a significant improvement from P1 (66.3%, 132/199) to P2 (82.9%, 102/123) (P = 0.001). Among the 68 patients who received ECMO, P2 had significantly lower baseline oxygenation index and serum lactate levels before ECMO cannulation than P1. The survival rate of patients who received ECMO also remarkably improved from P1 (21.1%, 8/38) to P2 (56.7%, 17/30). Subgroups who could be weaned from ECMO before 2 weeks after cannulation showed the best survival rate.

Conclusion

META significantly improved the survival rate of newborn infants with CDH. Further interventions, including prenatal intervention and novel ECMO strategies, may help improve the clinical outcomes and quality of life.

Keywords: Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation, Survival Rate, Quality Improvement

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) is a rare condition that occurs in approximately 1 in 4,000 newborns.1 Despite advances in neonatal intensive care, CDH has a high mortality rate of 20–30%.2,3 Severe pulmonary hypertension resulting from lung compression by intestinal herniation is a major risk factor contributing to CDH mortality. To reduce early mortality in CDH, effective cardiopulmonary support, particularly in improving pulmonary hypertension in the early postnatal period, is important. Maximal cardiopulmonary support strategies include effective ventilator therapy and the administration of vasoactive agents and pulmonary hypertension medications, including inhaled nitric oxide (iNO). Nevertheless, severe pulmonary hypertension, which is primarily caused by severe pulmonary hypoplasia in utero, is not easily reversible and can result in refractory hypoxemia and hypercarbia, which are two major pathologic conditions that warrant extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO).

Over the past three decades, ECMO has remained as the last treatment option for patients unable to maintain cardiopulmonary function with supportive care; however, the survival benefit of ECMO in neonates with CDH is debatable.4,5 According to the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO) registry data, CDH accounts for approximately 50% of neonatal respiratory ECMO cases and has the lowest survival rate compared with other respiratory diseases indicated for neonatal ECMO.6 However, CDH outcomes in Korea have not reached the levels observed in international literature, and no reports have demonstrated increased survival rates in severe cases undergoing ECMO.7,8,9,10

Therefore, the present study aimed to examine the treatment outcomes of CDH at a single tertiary center and to assess the effects of a multidisciplinary ECMO team approach (META) as part of a quality improvement (QI) initiative aimed at enhancing survival rates in neonates with CDH.

METHODS

Study population and data selection

The medical records of neonates diagnosed with CDH who were born and managed in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) of Asan Medical Center between January 2008 and December 2023 were reviewed. Asan Medical Center is a university-affiliated tertiary hospital and the major referral center for fetal diagnosis of CDH in South Korea. It has a 62-bed NICU and 24-bed pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) with ECMO capability. The exclusion criteria included postoperative diagnosis of Morgagni hernia, hiatal hernia, and diaphragmatic eventration.

The following demographic and clinical characteristics were collected: antenatal ultrasound data including observed/expected lung-to-head ratio (O/E LHR). O/E LHR data were available since 2014, and all data were obtained in the 2nd and/or 3rd trimester as previously described.10 The value obtained by manual tracing of lung margins (O/E LHR trace) was selected. Other perinatal parameters included gestational age, anthropometric measurements at birth, sex, mode of delivery, 1- and 5-min APGAR scores, and associated major structural or genetic abnormalities (i.e., non-isolated CDH). Treatment data included the use of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation (HFOV), iNO, and surfactant. Surgical data included date, repair type, and presence of herniation of the liver into the thorax. ECMO-related data encompassed the initial mode (venoarterial [VA] or veno-veno [VV]), baseline blood gas analysis data, oxygenation index (OI) before cannulation, ECMO duration, severe neurological injury on brain magnetic resonance imaging prior to NICU discharge, and survival upon NICU discharge.

Patients were divided into two groups based on the establishment of the neonatal ECMO team at our center: period 1 (P1, from January 2008 to August 2018) and period 2 (P2, from September 2018 to December 2023). The mortality rate at NICU discharge was compared between the two periods.

Supportive care and ECMO management protocol for infants with CDH

The medical management and ECMO protocols were described previously.11 Briefly, all inborn neonates were intubated at birth and admitted to the NICU for mechanical ventilation. HFOV was given if the target preductal saturation (85–95%) or arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (45–60 mmHg) was not achieved with a conventional ventilator with a high peak inspiratory pressure (up to 25–30 cmH2O) and respiratory rate (> 40–60/min). Meanwhile, ECMO was indicated for infants with a gestational age of ≥ 34 + 0 weeks or birth weight ≥ 2,000 g without lethal congenital anomalies; severe intracranial hemorrhage or brain injury; and severe cardiorespiratory failure as evidenced by 1) OI > 40, 2) failure to wean from 100% oxygen, 3) echocardiographic evidence of severe pulmonary hypertension and/or cardiac dysfunction, or 4) pressor-resistant hypotension and/or shock despite maximal cardiopulmonary support (i.e., iNO and inotropes).

Changes in management protocol through META

A multidisciplinary team meeting, including neonatologists, pediatric surgeons, pediatric cardiologists, a ECMO nurse specialist, and pediatric cardiac surgeons, was held to address the lack of improvement in the survival rate of patients with CDH requiring ECMO. The ECMO management protocol for CDH was revised in 2018, with the following major changes from P1 to P2: 1) In P1, patients requiring ECMO were moved from the NICU to the PICU for cannulation and ECMO run, unless otherwise indicated. In P2, patients requiring ECMO were cannulated and managed in the NICU. 2) In P1, the initial ECMO modality was VV or VA ECMO at the preference of the pediatric cardiac surgeon. In P2, all patients were initially supported with VA ECMO. 3) In P1, ECMO was used as a last resort after iNO with HFOV. In P2, ECMO was considered as priority even before the use of iNO. 4) In P1, surgical repair timing for patients on ECMO was not protocolized and mostly performed on ECMO. In P2, repair was planned for patients who could be weaned off ECMO (off-ECMO repair). On-ECMO repair was attempted only in patients who could not be weaned from ECMO after 2 to 3 weeks of age.

The initial flow rate of ECMO was initially set between 100 mL/kg/min and 140 mL/kg/min and adjusted based on the level of pulmonary or cardiac support. The target mixed venous saturation was 65–80%. Anticoagulation was performed using unfractionated heparin with a target activated clotting time of 180–220 seconds, which was often reduced to 160–180 seconds for controlling bleeding. An activated partial thromboplastin of 1.5–2.5, which falls within the normal neonatal reference range, was also used to adjust anticoagulation. Once adequate pump flow was established, ventilatory support was reduced to “rest setting.” Continuous morphine and intermittent or continuous infusions of vecuronium were administered to all patients on ECMO. In VA ECMO, a trial off is recommended when ECMO flow drops below 30–50 mL/kg/min and the sweep gas flow rate is low (< 0.2–0.3 L/min) while increasing the ventilator setting.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of neonates in the two study periods were summarized using descriptive statistics. Means with standard deviations were used to present continuous variables, whereas frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. The χ2 test (or Fisher’s exact test) and independent t-test were used for categorical and continuous variables, respectively, to compare the two study periods. To identify variables independently associated with mortality, Cox proportional-hazards regression analysis was performed. In-hospital mortality was the dependent variable, and baseline characteristics that were significant in the univariate analysis were the independent variables. The overall survival rate was calculated using Kaplan–Meir survival estimate curves and compared between the two periods using a log-rank test in patients requiring ECMO. Statistical significance was considered at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center, South Korea and the requirement for informed consent was waived (IRB No. 2023-1916).

RESULTS

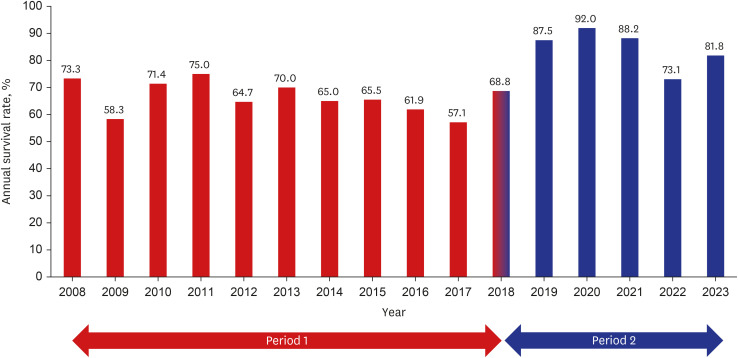

During the study period, 329 patients were diagnosed with CDH. After excluding Morgagni type hernia (n = 3), hiatal hernia (n = 2), and diaphragmatic eventration (n = 2), 322 patients were included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics were similar between P1 (n = 199) and P2 (n = 123). However, a higher rate of cesarean section and non-isolated type was observed in P2 (Table 1). The O/E LHR, a prenatal indicator of disease severity, was available in 212 cases (65.8%) and did not differ between the periods. The use of surfactant, HFOV, and iNO significantly decreased from P1 to P2. No significant differences were observed in the percentage of patients requiring ECMO between P1 (n = 38, 19.1%) and P2 (n = 30, 24.4%). The time to surgical repair was delayed in P2 (9.4 ± 8.0 days) than in P1 (6.7 ± 7.3 days). The patch repair frequency was significantly greater in P2 than in P1. The overall survival rate at NICU discharge was 72.7%, with a significant improvement from P1 (66.3%) to P2 (82.9%) (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Comparison of baseline characteristics in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia between period 1 and period 2.

| Variables | Period 1 (n = 199) | Period 2 (n = 123) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 113 (56.8) | 73 (59.3) | 0.651 |

| Cesarean section | 125 (62.8) | 103 (83.7) | < 0.001 |

| Outborn | 9 (4.5) | 2 (1.6) | 0.140 |

| Gestational age, wk | 37.8 ± 2.3 | 37.8 ± 1.9 | 0.860 |

| Birth weight, g | 2,867.7 ± 594.9 | 2,903.3 ± 577.1 | 0.767 |

| Non-isolated | 18 (9.0) | 23 (18.7) | 0.012 |

| Small for gestational age (< 10p) | 36 (18.1) | 18 (14.6) | 0.420 |

| 1-min APGAR score, median (IQR) | 6 (4–7) | 5 (3–6) | 0.004 |

| 5-min APGAR score, median (IQR) | 8 (6–8) | 7 (6–8) | 0.014 |

| Left-sided | 167 (83.9) | 99 (80.5) | 0.285 |

| Right-sided | 31 (15.6) | 21 (17.1) | |

| Bilateral | 1 (0.5) | 3 (2.4) | |

| O/E LHRa | 53.4 ± 17.6 | 51.2 ± 19.4 | 0.392 |

| Surfactant use | 29 (14.6) | 5 (4.1) | 0.003 |

| Air leak syndrome | 24 (12.1) | 9 (7.3) | 0.173 |

| HFOV use | 153 (76.9) | 53 (43.1) | < 0.001 |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | 96 (48.2) | 34 (27.6) | < 0.001 |

| ECMO | 38 (19.1) | 30 (24.4) | 0.258 |

| Operability | 164 (82.4) | 106 (86.2) | 0.372 |

| Age at repair, daysb | 6.7 ± 7.3 | 9.4 ± 8.0 | 0.004 |

| Open repairb | 95 (57.9) | 62 (58.5) | 0.927 |

| Liver upb | 48 (29.3) | 41 (38.7) | 0.108 |

| Patch repairb | 50 (30.5) | 54 (50.9) | 0.001 |

| Mortality at NICU discharge | 67 (33.7) | 21 (17.1) | 0.001 |

Values are presented as means ± standard deviation or numbers with percentages or ranges in parentheses.

IQR = interquartile range, O/E LHR = observed/expected lung-to-head ratio, HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, NICU = neonatal intensive care unit.

aData were available in 212 cases: period 1 (n = 96) and period 2 (n = 116).

bData were available in 270 cases who underwent surgical repair.

Fig. 1. Changes in survival rates of congenital diaphragmatic hernia during the ECMO era. The numbers indicate the annual survival rate in period 1 (red bars) and period 2 (blue bars).

ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

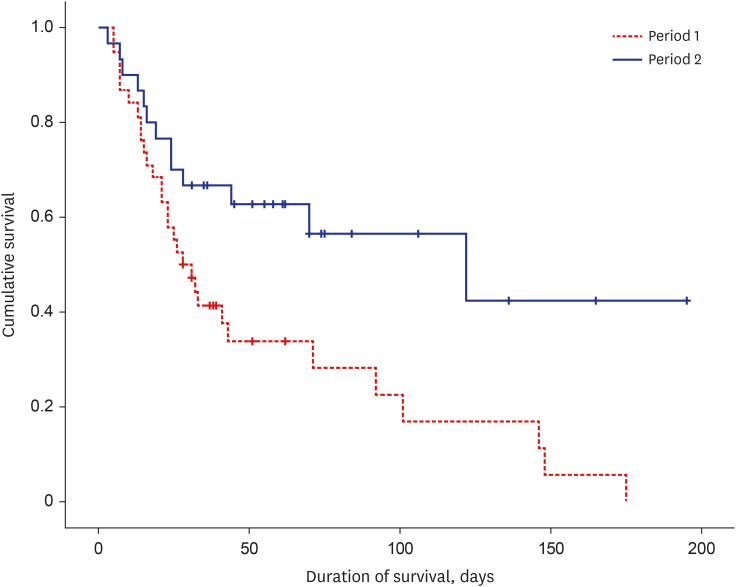

Out of the 68 patients (21.1%) who received ECMO, 9 (13.2%) were classified as non-isolated CDH, which included cystic adenomatoid malformation (n = 1), congenital heart disease (n = 3), severe bilateral hydronephrosis (n = 1), esophageal atresia with tracheoesophageal fistula (n = 1), imperforate anus (n = 1), duodenal atresia (n = 1), and suspected chromosomal abnormalities (n = 1). The patients enrolled in each period had comparable baseline perinatal characteristics, except for the rate of cesarean section and APGAR scores (Table 2). No differences were observed in the postnatal hours to start ECMO cannulation between P1 and P2. However, P2 had significantly lower baseline OI and serum lactate levels before ECMO cannulation than P1. As expected per META protocol regarding surgical repair, the age at repair in patients requiring ECMO was significantly delayed in P2 (15.7 ± 7.3 days) than in P1 (4.9 ± 3.9 days). In P1, 94.7% (36/38) patients underwent repair, whereas 26.7% (8/28) patients who did not undergo repair died. Among patients who underwent CDH repair (n = 58), the rate of off-ECMO repair was significantly lower in the early (< 7 days after birth) repair group (11/33, 33.3%) than in the delayed (≥ 7 days after birth) repair group (22/25, 75.9%) (P = 0.007). The survival rate of patients who received ECMO also remarkably improved from P1 (21.1%) to P2 (56.7%) (Fig. 2). Among survivors, the ECMO duration was significantly longer in P2 (12.3 ± 6.7 days) than in P1 (6.4 ± 1.5 days) (P = 0.024). The incidence of severe neurologic injury did not differ between P1 (0/8, 0%) and P2 (4/17, 23.5%) among survivors (P = 0.269).

Table 2. Comparison of patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia supported by ECMO between period 1 and period 2.

| Variables | Period 1 (n = 38) | Period 2 (n = 30) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 25 (65.8) | 17 (56.7) | 0.442 |

| Cesarean section | 26 (68.4) | 27 (90.07) | 0.042 |

| Gestational age, wk | 38.4 ± 1.4 | 37.5 ± 1.3 | 0.860 |

| Birth weight, g | 3,071.1 ± 451.1 | 2,938.0 ± 472.8 | 0.767 |

| Non-isolated | 4 (10.5) | 5 (16.7) | 0.493 |

| Small for gestational age (< 10p) | 6 (15.8) | 4 (13.3) | 1.000 |

| 1-min APGAR score, median (IQR) | 5 (4–6) | 4 (3–4) | < 0.001 |

| 5-min APGAR score, median (IQR) | 7 (6–8) | 6 (5–7) | < 0.001 |

| Right-sided | 7 (18.4) | 6 (20.0) | 0.869 |

| O/E LHR tracinga | 41.5 ± 13.4 | 37.4 ± 9.2 | 0.229 |

| ECMO in NICU | 2 (5.3) | 30 (100) | < 0.001 |

| ECMO start, postnatal hours | 23.8 ± 20.9 | 29.4 ± 44.9 | 0.504 |

| Pre-ECMO pH | 7.06 ± 0.20 | 7.05 ± 0.16 | 0.794 |

| Pre-ECMO PaCO2 | 66.5 ± 28.3 | 74.2 ± 28.9 | 0.275 |

| Pre-ECMO lactate | 7.50 ± 5.02 | 3.94 ± 3.25 | 0.001 |

| Pre-ECMO oxygenation index | 118.4 ± 111.1 | 60.2 ± 37.9 | 0.005 |

| Surfactant use | 11 (28.9) | 2 (6.7) | 0.029 |

| Air leak syndrome | 6 (15.8) | 3 (10.0) | 0.721 |

| HFOV use | 38 (100.0) | 22 (73.3) | 0.001 |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | 38 (100.0) | 21 (70.0) | < 0.001 |

| Initial modality with venoarterial | 16 (42.1) | 30 (100) | < 0.001 |

| Operabilityb | 36 (94.7) | 22 (73.3) | 0.018 |

| Repair on ECMOb | 23 (63.9) | 2 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

| Age at repair, daysb | 4.9 ± 3.9 | 15.7 ± 7.3 | < 0.001 |

| Age at repair < 7 days | 27 (75.0) | 2 (9.1) | < 0.001 |

| Open repairb | 35 (97.2) | 21 (95.5) | 1.000 |

| Liver upb | 21 (58.3) | 16 (72.7) | 0.268 |

| Patch repairb | 24 (66.7) | 21 (95.5) | 0.011 |

| Mortality at NICU discharge | 30 (78.9) | 13 (43.3) | 0.002 |

Values are presented as means ± standard deviation or numbers with percentages or ranges in parentheses.

IQR = interquartile range, O/E LHR = observed/expected lung-to-head ratio, ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, NICU = neonatal intensive care unit, HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation.

aData were available in 46 cases: period 1 (n = 16) and period 2 (n = 30).

bData were available in 58 cases who underwent surgical repair.

Fig. 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves for congenital diaphragmatic hernia comparing period 1 and period 2.

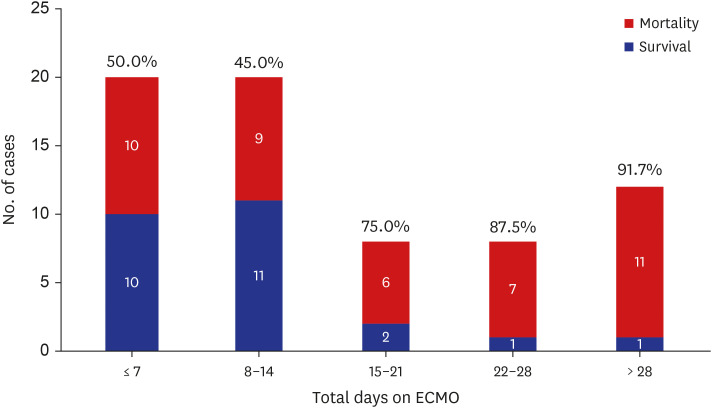

The risk factors of mortality among ECMO cases are shown in Table 3. In univariate analysis, mortality was significantly associated with pre-ECMO blood gas analysis parameters including pH, and lactate levels, OI before ECMO, initial modality with VA ECMO, repair on ECMO, and age at repair. In multivariate analysis, the factors associated with mortality included pre-ECMO lactate level, pre-ECMO OI, and early (< 7 days after birth) repair (Table 4). Subgroups that were able to wean from ECMO before 2 weeks after cannulation had the highest survival rate during the study period. There were no survivors when the patients were dependent on ECMO for more than 5 weeks (Fig. 3).

Table 3. Analysis of mortality risk factors in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia who underwent ECMO.

| Variables | Survivors (n = 25) | Non-survivors (n = 43) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, male | 15 (60.0) | 27 (62.8) | 1.000 |

| Cesarean section | 19 (76.0) | 34 (79.1) | 0.770 |

| Gestational age, wk | 37.9 ± 1.1 | 38.6 ± 1.4 | 0.062 |

| Birth weight, g | 3,051.2 ± 493.7 | 2,989.8 ± 447.3 | 0.601 |

| Non-isolated | 1 (4.0) | 8 (18.6) | 0.139 |

| Small for gestational age (< 10p) | 2 (8.0) | 8 (18.6) | 0.304 |

| 1-min APGAR score, median (IQR) | 4 (3–6) | 4 (3–6) | 0.717 |

| 5-min APGAR score, median (IQR) | 7 (6–7.5) | 7 (6–8) | 0.984 |

| Right-sided | 7 (28.0) | 6 (14.0) | 0.156 |

| O/E LHR tracinga | 39.8 ± 10.1 | 38.1 ± 11.5 | 0.621 |

| Surfactant use | 3 (12.0) | 10 (23.3) | 0.345 |

| Air leak syndrome | 2 (8.0) | 7 (16.3) | 0.468 |

| HFOV use | 19 (76.0) | 41 (95.3) | 0.044 |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | 20 (80.0) | 39 (90.7) | 0.272 |

| ECMO in NICU | 19 (76.0) | 13 (30.2) | < 0.001 |

| ECMO start, postnatal hours | 30.4 ± 40.1 | 23.9 ± 29.2 | 0.448 |

| Pre-ECMO pH | 7.12 ± 0.13 | 7.01 ± 0.20 | 0.016 |

| Pre-ECMO PaCO2 | 59.0 ± 28.3 | 76.2 ± 28.7 | 0.016 |

| Pre-ECMO lactate | 3.59 ± 2.84 | 7.29 ± 4.98 | < 0.001 |

| Pre-ECMO oxygenation index | 52.9 ± 34.4 | 115.8 ± 106.9 | 0.001 |

| Initial modality with VA ECMO | 21 (84.0) | 25 (58.1) | 0.028 |

| Repair on ECMOb | 8 (32.0) | 17 (51.5) | 0.137 |

| Age at repairb | 12.3 ± 7.8 | 6.5 ± 6.3 | 0.003 |

| Age at repair < 7 days | 6 (24.0) | 23 (69.7) | 0.001 |

| Open repairb | 24 (96.0) | 32 (97.0) | 1.000 |

| Liver upb | 16 (64.0) | 21 (63.6) | 0.997 |

| Patch repairb | 21 (84.0) | 24 (72.7) | 0.358 |

| Period 2 (vs. Period 1) | 17 (68.0) | 13 (30.0) | 0.002 |

Values are presented as means ± standard deviation or numbers with percentages or ranges in parentheses.

ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, IQR = interquartile range, O/E LHR = observed/expected lung-to-head ratio, HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, NICU = neonatal intensive care unit, VA = venoarterial.

aData were available in 46 cases: period 1 (n = 16) and period 2 (n = 30).

bData were available in 58 cases who underwent surgical repair.

Table 4. Cox proportional-hazards analysis for mortality in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia who underwent ECMO.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Sex, male | 1.300 | 0.696–2.431 | 0.411 | - | - | - |

| Cesarean section | 0.926 | 0.444–1.932 | 0.837 | - | - | - |

| Gestational age, wk | 1.272 | 0.955–1.962 | 0.099 | - | - | - |

| Birth weight, g | 1.000 | 0.999–1.001 | 0.800 | - | - | - |

| Non-isolated | 1.579 | 0.728–3.425 | 0.248 | - | - | - |

| Small for gestational age (< 10p) | 1.198 | 0.557–2.580 | 0.644 | - | - | - |

| 1-min APGAR score, median (IQR) | 1.023 | 0.852–1.229 | 0.808 | - | - | - |

| 5-min APGAR score, median (IQR) | 1.016 | 0.834–1.238 | 0.875 | - | - | - |

| Right-sided | 0.576 | 0.246–1.346 | 0.202 | - | - | - |

| O/E LHR tracinga | 1.002 | 0.966–1.040 | 0.895 | - | - | - |

| Surfactant use | 1.642 | 0.797–3.380 | 0.179 | - | - | - |

| Air leak syndrome | 1.419 | 0.636–3.166 | 0.393 | - | - | - |

| HFOV use | 2.285 | 0.622–8.393 | 0.213 | - | - | - |

| Inhaled nitric oxide | 1.174 | 0.432–3.191 | 0.753 | - | - | - |

| ECMO in NICU | 0.389 | 0.203–0.747 | 0.005 | - | - | - |

| ECMO start, postnatal hours | 1.001 | 0.993–1.010 | 0.753 | - | - | - |

| Pre-ECMO pH | 0.087 | 0.015–0.509 | 0.007 | - | - | - |

| Pre-ECMO PaCO2 | 1.017 | 1.007–1.028 | 0.002 | - | - | - |

| Pre-ECMO lactate | 1.126 | 1.059–1.198 | < 0.001 | 1.098 | 1.027–1.175 | 0.007 |

| Pre-ECMO oxygenation index | 1.006 | 1.003–1.008 | < 0.001 | 1.005 | 1.002–1.008 | < 0.001 |

| Initial modality with VA ECMO | 0.579 | 0.314–1.066 | 0.079 | - | - | - |

| Repair on ECMOb | 2.685 | 1.312–5.496 | 0.007 | - | - | - |

| Age at repair < 7 days | 3.401 | 1.613–7.143 | 0.001 | 2.646 | 1.217–5.780 | < 0.001 |

| Open repairb | 0.595 | 0.110–3.211 | 0.546 | - | - | - |

| Liver upb | 0.799 | 0.388–1.645 | 0.543 | - | - | - |

| Patch repairb | 0.573 | 0.263–1.245 | 0.159 | - | - | - |

| Period 2 (vs. Period 1) | 0.443 | 0.231–0.851 | 0.015 | - | - | - |

Values are presented as means ± standard deviation or numbers with percentages or ranges in parentheses.

ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval, IQR = interquartile range, O/E LHR = observed/expected lung-to-head ratio, HFOV = high-frequency oscillatory ventilation, NICU = neonatal intensive care unit, VA = venoarterial.

aData were available in 46 cases: period 1 (n = 16) and period 2 (n = 30).

bData were available in 58 cases who underwent surgical repair. The Cox proportional-hazard analysis model included subjects who did not undergo surgical repair as one category level, but hazard ratio estimates for the category level is not presented.

Fig. 3. Mortality rate and duration of ECMO run. The numbers within and on top of each bar represent the number of cases and mortality rate, respectively.

ECMO = extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

DISCUSSION

Herein, we report the results of a 16-year review of 322 patients with CDH, including 68 patients who underwent ECMO at a single institution. To the best of our knowledge, this series represents the largest reported cohort of neonatal ECMO in Korea. We found that META as a QI initiative significantly contributed to the improved survival rate in patients with CDH. The survival rate (82.9%) in P2 is comparable to that of a recent large international cohort2,3 and is superior to previous reports in Korea, including our previous studies.7,8,9,10

The difference in increase in survival rates from P1 to P2 could not be attributed to a less severe disease activity in P2 than in P1. Rather, the disease severity appears to be greater in P2 than in P1, as evidenced by lower APGAR scores and a higher incidence of non-isolated CDH. Although the time to ECMO initiation did not differ between the two periods, a trend toward a safer transition to ECMO was observed, as reflected by significantly lower pre-ECMO OI and lactate levels in P2 than in P1. In neonatal respiratory failure, ECMO should be initiated before hypoxic injury occurs. This principle may be better adhered to in P2 than in P1, where each attending physician decided to ECMO run and had relatively little experience with ECMO. It is also possible that patients treated in P1, wherein most were transported for ECMO cannulation on a transport ventilator with high settings or a manual positive pressure bagging with 100% oxygen, were exposed to more unstable respiratory support and uncontrolled high positive pressure, although for a shorter period, compared with patients treated in P2. The lower pre-ECMO blood lactate levels in P2 than in P1 suggest that the risk of potential myocardial and/or brain injury could be reduced in patients treated with ECMO in P2 than in P1. Among adult patients who underwent VA ECMO for cardiogenic shock, initiating ECMO in a less deteriorated baseline clinical condition, reflected by lower pre-ECMO lactate levels, was associated with lower mortality.12,13 This is also consistent with a pre-ECMO model that predicted mortality in CDH, wherein pre-ECMO blood gas data and mean airway pressure were significant predictors.14

In this study, the timing of repair, particularly early (< 7 days) repair, was significantly associated with in-hospital mortality among patients who underwent ECMO. Despite the arbitrary classification, the rate of on-ECMO repair was significantly higher among patients who received early repair than among those who received delayed (≥ 7 days) repair. In P2, off-ECMO repair was one of the major changes of META in terms of the surgical management strategy for CDH. The optimal timing for diaphragm repair among patients with CDH who are undergoing ECMO has long been a topic of debate. Theoretically, repairing the diaphragm on ECMO may improve respiratory and cardiac function by restoring herniated intra-abdominal organs. However, on-ECMO repair is associated with an increased risk of bleeding complications. Our findings are in line with those of previous studies, which reported that delaying CDH repair until after weaning from ECMO improves survival and reduces ECMO duration.15,16,17,18 However, some institutions prefer an early repair approach, typically within 72 hours after ECMO run.19,20,21 Among the study groups favoring early repair, Steen et al.22 reported a higher survival rate with a super-early (< 24 hours) repair strategy compared with an early (24–72 hours) repair strategy. Theoretically, the super-early strategy may maximize the advantage of normalizing the thoracic anatomy, which allows the lungs to expand and the heart to position correctly. This approach can minimize non-repair risk by allowing a less technically demanding operation before the development of generalized edema caused by reduced cardiac and renal function. In the present study, the survival rate of early on-ECMO repair, mostly performed in P1, was poor, and a significant proportion of patients succumbed to post-repair bleeding complications. However, a subset of patients with severe CDH may benefit from early repair on ECMO, or even before ECMO cannulation.

Between P1 and P2, the main changes in treatment prior to ECMO initiation were the use of iNO and surfactant. In P1, iNO was applied in all patients before ECMO. However, in P2, the frequency of iNO use was significantly reduced according to META, which considers ECMO before iNO use. Nevertheless, iNO use was not associated with mortality among patients who underwent ECMO. This finding is consistent with the results of the Neonatal Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study, which showed that iNO did not improve oxygenation and survival in the subgroup of patients with CDH with a gestational age of 34 weeks or later, but instead led to a higher incidence of ECMO requirement.23 Recent studies using the CDH Study Group registry data have shown that iNO use is associated with increased mortality and ECMO requirement, even after controlling for risk factors such as pulmonary hypertension status and defect size.24,25 These results suggest that iNO may not be effective and may even worsen clinical status in CDH. There are several possible explanations for the lack of efficacy of iNO in CDH. CDH-associated pulmonary hypertension results from the abnormal development of the pulmonary vasculature and disruption of the nitric oxide signaling pathway compared with other causes of early pulmonary hypertension in neonates.26 Moreover, the use of pulmonary vasodilators may worsen left ventricular dysfunction in patients with CDH by increasing left atrial pressure, resulting in pulmonary venous congestion and edema.27 Surfactant use was significantly lower in P2 than in P1. However, it is unlikely that differences in surfactant use contributed to differences in pre-ECMO blood gas analysis results or mortality among patients with severe hypoxia requiring ECMO. Based on observational and nonrandomized studies, the role of surfactant in CDH remains controversial.28,29,30 The pattern of surfactant maturation is not impaired in human fetuses with CDH.31 An analysis of large registry data revealed no survival benefit, but rather a risk in both term and preterm infants with CDH.28,30 Moreover, a recent study demonstrated a trend toward decreased mortality and ECMO in patients with CDH who received surfactant therapy after fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion.29 In addition to these two major changes identified in our study, we cannot completely exclude the possibility that the improved stabilization of the patient’s condition before ECMO in P2 than in P1 was due to the evolution of other intensive care provided by physicians and nurses over time.

In the present study, VA ECMO was used as the primary modality of ECMO in all cases born in P2 with a significantly higher proportion compared with that in P1. According to ELSO data, VA ECMO is preferred by more than 80% in CDH cases.32 Theoretically, VA ECMO is superior to VV ECMO in providing cardiac support, particularly in left ventricular dysfunction. However, no randomized controlled trial has compared the two modalities in CDH. Previous reports have not shown whether VA ECMO has a survival advantage over VV ECMO in CDH.33,34 Moreover, these studies were limited by their retrospective nature, lack of risk stratification based on cardiac dysfunction severity, and small but inevitable proportion of modality conversion from VV to VA. In the present study, META did not initially plan to use VA ECMO. As the double-lumen catheter required for VV ECMO has been unavailable in our country since 2018, we were forced to begin with VA ECMO instead. Moreover, there is a concern that VA ECMO may increase the risk of neurological complications. Theoretically, the higher incidence of intracranial hemorrhage in VA ECMO than in VV ECMO may be associated with the change in cerebral hemodynamics resulting from the abrupt cessation of cerebral blood flow by carotid artery cannulation and the increased cerebral venous pressure because of internal jugular vein ligation in VA ECMO cannulation.35 However, aside from the improvement in survival rate, the incidence of severe neurologic complications in survivors did not differ between P1 and P2.

In this study, subgroups who were weaned from ECMO before 2 weeks after cannulation had the best survival rate. The survival rate decreased as ECMO run days increased, with no survivors after 5 weeks of ECMO run. This finding is consistent with that of previous studies, which have shown extremely low chances of survival for patients who are ECMO-dependent for more than 6 weeks.36,37 However, it is important to consider various factors when deciding to discontinue treatment, including whether repair surgery was performed and the possibility of second ECMO after weaning failure. Clear communication between medical staff and families regarding ECMO initiation and termination should be made before ECMO runs. Additionally, providing unnecessary life-sustaining treatment to extremely poor prognostic groups should be avoided. The primary factor to consider is the extremely low O/E LHR (e.g., < 15%). Several early prognostic markers including the lowest PaCO2 concentration during the first few hours of life should also be also taken into account.38

The limitations of our study include the single-center, retrospective design and small number of cases. However, this is the largest study regarding neonatal ECMO reported in Korea to date, and the number of cases (more than an average of 20 cases per year) is comparable to that of other large international centers. It is impossible to fully account for changes in treatment-related variables over the study period other than the major changes associated with META. These variables may include early intensive care strategies, evolving surgical techniques, the introduction of new medications for pulmonary hypertension, and, most importantly, differences in the level of care provided by nursing teams that cannot be easily defined by specific variables. Fetal endoscopic tracheal occlusion was not available in our center during the study period.

In conclusion, our study highlights the positive impact of META as a QI initiative on CDH survival, including on-site ECMO management, use of VA) modality, ECMO indication as a priority before the use of pulmonary vasodilators, and the policy of post-ECMO repair in newborn infants with CDH. Further interventions for severe cases, including prenatal intervention and novel ECMO strategies, may help improve the survival rate and quality of life.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank all members of the multidisciplinary ECMO team for congenital diaphragmatic hernia at Asan Medical Center for their dedicated participation.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Lee BS, Jung E, Namgoong JM, Kim DY.

- Data curation: Kim H, Lee HN, Jeong J, Kwon H.

- Formal analysis: Lee BS, Jung E.

- Methodology: Lee BS, Jung E, Kim SH.

- Writing - original draft: Lee BS, Jung E, Kim H, Kim SH, Lee HN, Kwon H, Namgoong JM.

- Writing - review & editing: Lee BS, Jung E, Jeong J, Kim DY.

References

- 1.Pober BR. Overview of epidemiology, genetics, birth defects, and chromosome abnormalities associated with CDH. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2007;145C(2):158–171. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smithers CJ, Zalieckas JM, Rice-Townsend SE, Kamran A, Zurakowski D, Buchmiller TL. The timing of congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation impacts surgical bleeding risk. J Pediatr Surg. 2023;58(9):1656–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta VS, Harting MT, Lally PA, Miller CC, Hirschl RB, Davis CF, et al. Mortality in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a multicenter registry study of over 5000 patients over 25 years. Ann Surg. 2023;277(3):520–527. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000005113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morini F, Goldman A, Pierro A. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a systematic review of the evidence. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 2006;16(6):385–391. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-924751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mugford M, Elbourne D, Field D. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe respiratory failure in newborn infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(3):CD001340. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001340.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guner YS, Harting MT, Jancelewicz T, Yu PT, Di Nardo M, Nguyen DV. Variation across centers in standardized mortality ratios for congenital diaphragmatic hernia receiving extracorporeal life support. J Pediatr Surg. 2022;57(11):606–613. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2022.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeon S, Jeong MH, Jeong SH, Park SJ, Lee N, Bae MH, et al. Perinatal prognostic factors for congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a Korean single-center study. Neonatal Med. 2022;29(2):76–83. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hwang JH, Kim CY, Park HW, Namgoong JM, Kim DY, Kim SC, et al. Trends in treatment outcome and critical predictors of mortality for congenital diaphragmatic hernia in a single center. Perinatology. 2018;29(2):72–77. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahn JH, Jung YH, Shin SH, Kim HY, Kim EK, Kim HS. Respiratory severity score as a predictive factor for the mortality of congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Neonatal Med. 2018;25(3):102–108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim BE, Ha EJ, Kim YA, Kim S, Park JJ, Yun TJ, et al. Four cases of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Korean Soc Neonatol. 2009;16(1):64–70. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong J, Lee BS, Cha T, Jung E, Kim EA, Kim KS, et al. Prenatal prognostic factors for isolated right congenital diaphragmatic hernia: a single center’s experience. BMC Pediatr. 2021;21(1):460. doi: 10.1186/s12887-021-02931-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim E, Sodirzhon-Ugli NY, Kim DW, Lee KS, Lim Y, Kim MC, et al. Prediction of 6-month mortality using pre-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation lactate in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing veno-arterial-extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Chest Surg. 2022;55(2):143–150. doi: 10.5090/jcs.21.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mungan İ, Kazancı D, Bektaş Ş, Ademoglu D, Turan S. Does lactate clearance prognosticates outcomes in ECMO therapy: a retrospective observational study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2018;18(1):152. doi: 10.1186/s12871-018-0618-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guner YS, Nguyen DV, Zhang L, Chen Y, Harting MT, Rycus P, et al. Development and validation of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation mortality-risk models for congenital diaphragmatic Hernia. ASAIO J. 2018;64(6):785–794. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Partridge EA, Peranteau WH, Rintoul NE, Herkert LM, Flake AW, Adzick NS, et al. Timing of repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia in patients supported by extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(2):260–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robertson JO, Criss CN, Hsieh LB, Matsuko N, Gish JS, Mon RA, et al. Comparison of early versus delayed strategies for repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(4):629–634. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2017.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bryner BS, West BT, Hirschl RB, Drongowski RA, Lally KP, Lally P, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: does timing of repair matter? J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(6):1165–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delaplain PT, Harting MT, Jancelewicz T, Zhang L, Yu PT, Di Nardo M, et al. Potential survival benefit with repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) after extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in select patients: Study by ELSO CDH Interest Group. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(6):1132–1137. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dassinger MS, Copeland DR, Gossett J, Little DC, Jackson RJ, Smith SD, et al. Early repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernia on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45(4):693–697. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fallon SC, Cass DL, Olutoye OO, Zamora IJ, Lazar DA, Larimer EL, et al. Repair of congenital diaphragmatic hernias on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO): does early repair improve patient survival? J Pediatr Surg. 2013;48(6):1172–1176. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glenn IC, Abdulhai S, Lally PA, Schlager A Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Early CDH repair on ECMO: Improved survival but no decrease in ECMO duration (A CDH Study Group Investigation) J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(10):2038–2043. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steen EH, Lee TC, Vogel AM, Fallon SC, Fernandes CJ, Style CC, et al. Congenital diaphragmatic hernia repair in patients on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: how early can we repair? J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(1):50–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The Neonatal Inhaled Nitric Oxide Study Group (NINOS) Inhaled nitric oxide and hypoxic respiratory failure in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatrics. 1997;99(6):838–845. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.6.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Putnam LR, Tsao K, Morini F, Lally PA, Miller CC, Lally KP, et al. Evaluation of variability in inhaled nitric oxide use and pulmonary hypertension in patients with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(12):1188–1194. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noh CY, Chock VY, Bhombal S, Danzer E, Patel N, Dahlen A, et al. Early nitric oxide is not associated with improved outcomes in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Pediatr Res. 2023;93(7):1899–1906. doi: 10.1038/s41390-023-02491-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohseni-Bod H, Bohn D. Pulmonary hypertension in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2007;16(2):126–133. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakshminrusimha S, Keszler M. Persistent Pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. Neoreviews. 2015;16(12):e680–e692. doi: 10.1542/neo.16-12-e680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lally KP, Lally PA, Langham MR, Hirschl R, Moya FR, Tibboel D, et al. Surfactant does not improve survival rate in preterm infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2004;39(6):829–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sevilmis YD, Olutoye OO, 2nd, Peiffer S, Mehl SC, Belfort MA, Rhee CJ, et al. Surfactant therapy in congenital diaphragmatic hernia and fetoscopic endoluminal tracheal occlusion. J Surg Res. 2024;296:239–248. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2023.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Meurs K Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Is surfactant therapy beneficial in the treatment of the term newborn infant with congenital diaphragmatic hernia? J Pediatr. 2004;145(3):312–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boucherat O, Benachi A, Chailley-Heu B, Franco-Montoya ML, Elie C, Martinovic J, et al. Surfactant maturation is not delayed in human fetuses with diaphragmatic hernia. PLoS Med. 2007;4(7):e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guner YS, Delaplain PT, Zhang L, Di Nardo M, Brogan TV, Chen Y, et al. Trends in mortality and risk characteristics of congenital diaphragmatic hernia treated with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. ASAIO J. 2019;65(5):509–515. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guner YS, Harting MT, Fairbairn K, Delaplain PT, Zhang L, Chen Y, et al. Outcomes of infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia treated with venovenous versus venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a propensity score approach. J Pediatr Surg. 2018;53(11):2092–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kugelman A, Gangitano E, Pincros J, Tantivit P, Taschuk R, Durand M. Venovenous versus venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38(8):1131–1136. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(03)00256-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuda S, Aoyama M, Yamada Y, Saitoh N, Honjoh T, Hasegawa T, et al. Comparison of venoarterial versus venovenous access in the cerebral circulation of newborns undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Surg Int. 1999;15(2):78–84. doi: 10.1007/s003830050521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kays DW, Talbert JL, Islam S, Larson SD, Taylor JA, Perkins J. Improved survival in left liver-up congenital diaphragmatic hernia by early repair before extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: optimization of patient selection by multivariate risk modeling. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(4):459–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seetharamaiah R, Younger JG, Bartlett RH, Hirschl RB Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. Factors associated with survival in infants with congenital diaphragmatic hernia requiring extracorporeal membrane oxygenation: a report from the Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia Study Group. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44(7):1315–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2008.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoffman SB, Massaro AN, Gingalewski C, Short BL. Survival in congenital diaphragmatic hernia: use of predictive equations in the ECMO population. Neonatology. 2011;99(4):258–265. doi: 10.1159/000319064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]