Abstract

Multiple circular and linear plasmids of Lyme disease and relapsing fever Borrelia spirochetes carry genes for members of the Bdr (Borrelia direct repeat) protein family. To define their common and divergent attributes, we first comprehensively compared the known homologs. Bdr proteins with predicted sizes ranging from 10.7 to 30.6 kDa formed five homology groups, based on variable numbers of short direct repeats in a central domain and diverse N- and C-terminal domains. In a further characterization, Western blots were probed with rabbit antisera raised against either of two purified recombinant Bdr proteins from Borrelia burgdorferi B31. The results showed that antibodies cross-react and several Bdr paralogs 19.5 to 30.5 kDa in size are expressed by cultured strain B31 in a temperature-independent manner. In situ proteolysis, immunofluorescence, and growth inhibition assays indicated that Bdr proteins are not surface exposed. Distinct patterns of cross-reacting proteins of 17.5 to 33 kDa were also detected in other B. burgdorferi, Borrelia garinii, and Borrelia afzelii strains as well as in relapsing fever spirochetes Borrelia hermsii and Borrelia turicatae. Last, we examined whether these proteins are antibody targets during Lyme disease. Analysis of 47 Lyme disease patient sera by immunoblotting and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays showed that 24 (51%) and 20 (43%), respectively, had detectable antibodies to one or more of the Bdr proteins. Together, these data indicate that Bdr proteins constitute a family of cross-reactive Borrelia proteins which are expressed in the course of Lyme disease and in vitro.

Spirochetes of the genus Borrelia are host-associated microorganisms that cycle between vertebrate hosts by means of arthropod vectors (10). Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, including B. burgdorferi (16), Borrelia garinii (5), Borrelia afzelii (18), and possibly several other closely related genospecies, are the etiologic agents of Lyme disease (50). A phylogenetically distinct group that includes Borrelia hermsii and Borrelia turicatae (39) are causes of relapsing fever (10).

The genome of Borrelia species consists of a 1-Mb linear chromosome (13, 25) complemented by a large number of linear plasmids (lp’s) and circular plasmids (cp’s) 10 to 60 kb in size (7, 46, 56, 61). lp’s and cp’s have been shown to share common sequences (8, 47, 48, 56, 61, 63, 64) and, in the case of a B. hermsii plasmid, can exist in both linear and circular forms (26). As lp’s and the chromosome appear to have exchanged genetic information (21) and some of the cp’s carry genes usually found on chromosomes of other prokaryotes (36), Borrelia plasmids have been likened to minichromosomes (6).

Both lp’s and cp’s are close to if not equimolar with the chromosome (32, 34). Peculiar in this respect is a family of cp’s about 32 kb in size (cp32s) which are almost identical in genetic information. In strain B31, eight of a total of nine distinct plasmids (numbered cp32-1 to cp32-9) have been identified within a clonal bacterial culture (22, 56). Similar cp32s or variants thereof have been found in other B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates (24, 28, 37, 47, 54). Recently, B. hermsii was shown to contain multiple related cp32s (51). This presence of several very similar yet not identical plasmid sequence entities within one cell leads to a host of paralogous gene families.

Three separate cp32-encoded loci have been sequenced and analyzed to different extents. The most in-depth studies to date have dealt with members of the Erp lipoprotein family, which are related to OspE and OspF, differentially expressed and immunogenic in mammals (52, 56). Two open reading frames (ORFs) originally identified as part of a genetic locus termed 2.9 present on seven cp32s of B. burgdorferi 297, 2.9orfA and 2.9orfB (37), have recently been shown to code for proteins with hemolytic activity in B. burgdorferi B31 (BlyA and BlyB [30]).

A third locus consisting of five ORFs (ORF-1, -2, -C, -3, and -E) flanked by inverted repeats was identified in part by Dunn and colleagues (24) and in our earlier studies on repeated DNA of Lyme disease spirochetes (48, 63, 64). The functions of the ORFs remain unknown. ORF-2 has been postulated to represent a RepC homolog (24), while ORF-C resembled bacterial proteins involved in plasmid partitioning (8, 53, 64). The last ORF in this locus, originally named ORF-E, featured multiple internal 33- and 21-bp-long direct in-frame repeats, suggesting a repeated protein motif domain. Two complete ORF-E copies were identified on one of the multiple homologous cp32s and the related lp56 of B. burgdorferi B31. The predicted polypeptides had 64% overall amino acid identity. Intriguingly, they varied in the number of direct repeat units and thus in size (24.1 and 20.6 kDa, respectively) (64). We hypothesized that these two ORF products represented members of a protein family. To date, a total of 29 ORF-E homologs have been described under various names in strain B31 (20, 28) and other B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates (1, 37, 54, 57) as well as other Borrelia species (19, 51).

To define the common and divergent characteristics of this protein family, we first undertook a comprehensive comparison of all known paralogs (i.e., intraspecies homologs) and orthologs (i.e., interspecies homologs). We then investigated their possible biological functions, using polyclonal antibodies raised against each of two B. burgdorferi B31 paralogs. Finally, we examined whether these proteins are targeted by the antibody response during Lyme disease. Our results demonstrate that they indeed represent a class of cross-reactive Borrelia proteins that are expressed in vitro and in vivo. Based on their common features, we suggest a common, unambiguous name, Bdr (for Borrelia direct repeat) for all members of this family.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

DNA sequence computer analysis.

DNA and protein sequences were obtained from the database sources listed in Table 1. Predictions of protein molecular weight, isoelectric point (pI), and secondary structure features as well as protein sequence identity comparisons (Higgins default values) were performed with the MacDNASIS Pro program suite (version 3.6; Hitachi Software Engineering). Unrooted phylogenetic trees were constructed with the Clustal X program suite (58): multiple pairwise sequence alignments (default values) were subjected to neighbor-joining and bootstrap analysis (number of bootstrap trials = 1,000). The resulting tree data were plotted with the DRAWTREE algorithm in the PHYLIP program suite (version 3.5; J. Felsenstein, University of Washington, Seattle). Transmembrane domains were predicted with the TMPred program (33).

TABLE 1.

ORF-E (bdr) paralogs and orthologs

| Strain | Plasmida | Paralog geneb | Proteinc

|

Accession no. (reference[s])d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Size (kDa) | pI | ||||

| B. burgdorferi | |||||

| B31 | cp32-1 (P) | bdrA | 24.1 | 5.11 | X87127 (ORF-E[25/65]) (64) |

| BBP34 (15, 20) | |||||

| bdrB | Missing (replaced by rev [37]) | ||||

| cp32-2 (?) | bdrC | Missing (not sequenced) | |||

| bdrD | Missing (not sequenced) | ||||

| cp32-3 (S) | bdrE | 22.7 | 5.74 | BBS37 (15, 20) | |

| bdrF | 23.2 | 4.88 | BBS29 (15, 20) | ||

| cp32-4 (R) | bdrG | 10.7 | 4.39 | BBR34 (15, 20) | |

| bdrH | 19.0 | 5.02 | BBR27 (15, 20) | ||

| cp32-5 (?) | bdrI | Missing (not sequenced) | |||

| bdrJ | Missing (not sequenced) | ||||

| cp32-6 (M) | bdrK | 25.4 | 4.98 | BBM34 (15, 20) | |

| bdrL | Missing (replaced by rev [37]) | ||||

| cp32-7 (O) | bdrM | 21.9 | 4.93 | BBO34 (15, 20) | |

| bdrN | 22.4 | 5.09 | BBO27 (15, 20) | ||

| cp32-8 (L) | bdrO | 22.1 | 6.20 | BBL35 (15, 20) | |

| bdrP | 21.1 | 4.94 | BBL27 (15, 20) | ||

| cp32-9 (N) | bdrQ | 20.7 | 5.17 | BBN34 (15, 20) | |

| bdrR | 21.0 | 4.94 | BBN29 (15, 20) | ||

| lp28-1 (F) | bdrS* | (19.9) | (7.20) | BBF03 AE000794 (28) | |

| lp28-2 (G) | bdrT | 30.6 | 5.29 | BBG33 (15, 20) | |

| AE000786 (28) | |||||

| lp28-3 (H) | bdrU | 25.8 | 5.30 | BBH13 (15, 20) | |

| AE000784 (28) | |||||

| lp56 (Q) | bdrV | 20.6 | 6.20 | X87201 (ORF-E[14/17]) (64) | |

| BBQ42 (15, 20) | |||||

| bdrW | 26.4 | 4.86 | BBQ34 (15, 20) | ||

| lp36 (K) | bdrX | 21.6 | 5.83 | BBK40 (15, 20) | |

| lp38 (J) | bdrY* | (7.9) | (10.13) | BBJ10 (15, 20) | |

| 297 | cp | 2.9-1rep | 21.1 | 4.98 | U45421 (37) |

| cp | 2.9-2rep | 24.7 | 4.74 | U45422 (37) | |

| cp | 2.9-3rep | 21.9 | 5.07 | U45423 (37) | |

| cp | 2.9-4rep | 23.2 | 4.88 | U45424 (37) | |

| cp | 2.9-5rep | 24.0 | 4.80 | U45425 (37) | |

| cp18-2 | 297 bdrA | 11.9 | 5.17 | AF023853 (ORF-E) (1, 2) | |

| N40 | cp18 | N40 bdrA | 21.9 | 4.93 | U42599 (orfE) (54) |

| B. afzelii DK1 | cp | DK1p21 | 22.4 | 5.29 | Y08413 (57) |

| B. hermsii HS1 | cp32 | bdrA | 21.8 | 4.95 | AF123078 (51) |

| B. turicatae 91E136 | lp | repA | 30.2 | 4.71 | AF062395 (19) |

Where identified, the cp and lp sizes are given. Plasmids of strains B31 are numbered and labeled with letters according to references 15, 20, and 28.

All ORFs found in strain B31 and the ones previously referred to as ORF-E or orfE in other strains were renamed bdr. The nomenclature of all other sequences follows the referenced publications. Probable pseudogenes lacking upstream Shine-Dalgarno sequences are marked with asterisks.

Protein sizes and pI values were calculated by using the MacDNASIS program. Coding sequences within an ORF were assumed to begin with the first AUG codon downstream of a consensus Shine-Dalgarno sequence (64).

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

B. burgdorferi B31 (ATCC 35210), Sh-2-82 (43), N40 (27), and HB19 (12), B. garinii Ip90 (5), B. afzelii ACA1 (3), B. hermsii HS1 (ATCC 35209), B. turicatae Oz1 (17), and the Osp-less B. burgdorferi B31 derivative B313 (41) were grown in BSKII medium supplemented with 12% rabbit serum at 24 or 34°C. Escherichia coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene), DH5α (Gibco), BL21(DE3)(pLysS) (Novagen), and InvαF′ (Invitrogen) were grown in LB Lennox medium at 30 or 37°C.

Nucleic acid analysis.

B. burgdorferi plasmid-enriched DNA was obtained by diethylpyrocarbonate extraction (9) and dot blotted onto nylon membranes (Nytran; Schleicher & Schuell), using standard procedures (4). DNA probes specific for B. burgdorferi B31 cp32-1 through cp32-9 (22, 56) were enzymatically labeled and used in Southern hybridizations (ECL [enhanced chemiluminescence] direct labeling and detection system; Amersham). Hybridizations were carried out in glass tubes in a Mini hybridization oven (Autoblot; Bellco) under standard stringency conditions (0.5× SSC in primary wash; 20× SSC is 0.3 M sodium citrate plus 3 M NaCl [pH 7]). PCRs with oligonucleotide primer pairs E155 plus E168 (cp32-2 specific) and E703 plus E704 (cp32-7 specific) were performed as described by Stevenson et al. (52, 53). DNA probes and primers were a gift from Brian Stevenson, University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Recombinant Bdr (rBdr) proteins.

bdrA and bdrV (Table 1) were PCR amplified from recombinant plasmids pOMB14 and pOMB65 (63, 64), using Pwo polymerase (Boehringer Mannheim) and primer pairs bdrA-fwd (5′-GGAATTCCATATGACTAATTTAGCGTAC-3′) plus bdrA-rev (5′-CCGAATTCTCATTAATGATGATGATGATGGTGTTTGATATATTG-3′) and bdrV-fwd (5′-GGAATTCCATATGAATAGTTTGAC-3′) plus bdrV-rev (5′-CCGAATTCTCATTAATGATGATGATGATGGTCTTTGCCACCTTGT-3′), respectively. Fragments were digested with NdeI and EcoRI, ligated into pET29b (Novagen), and cloned in E. coli XL1-Blue (Stratagene), resulting in recombinant plasmids pWRZ101 (bdrA) and pWRZ102 (bdrV).

E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS) (Novagen) transformants containing the recombinant plasmids were grown from single colonies at 37°C. Expression from the T7 promoter was induced with isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (final concentration of 1 mM) when the culture optical density at 595 nm (OD595) reached 0.4. Incubation continued for 3 h at 30°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and concentrated 20-fold by resuspension in column buffer (10 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM NaH2PO4, 500 mM NaCl [pH 7.4]) containing 100 mM imidazole and 2% Tween 20. Cleared lysates were obtained by freeze thawing (−20°C), brief sonication (Branson Sonifier), and passage through a 0.45-μm-pore-size filter (Nalgene). Lysates were passed over nickel-loaded 1-ml HisTrap columns (Pharmacia). After washing with 5 ml of column buffer–100 mM imidazole, rBdr was eluted in column buffer–500 mM imidazole, dialyzed against carbonate buffer (15 mM Na2CO3, 35 mM NaHCO3, 30 mM NaN3 [pH 9.6]) in Slide-A-Lyzer cassettes (10,000-molecular-weight cutoff; Pierce), and concentrated in Centriprep-10 centrifugal concentrators (Amicon). Protein concentrations were determined by a Bradford assay (Bio-Rad).

Whole-cell protein preparations.

Borrelia whole-cell lysates were prepared from early-stationary-phase BSKII cultures. Cells were harvested by centrifugation for 30 min at 2000 × g (Sorvall RT7), washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 10 mM MgCl2 (PBS-Mg), concentrated 50-fold by resuspension in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) loading buffer, and boiled for 5 min. Whole-cell protein preparations from low-passage infectious B. burgdorferi B31 initially grown at 23°C and then shifted to 35°C (55) were a gift from Brian Stevenson. For assaying surface exposure by proteinase K accessibility, intact or sonicated cells were treated with 200 μg of proteinase K (Boehringer Mannheim) per ml of cell suspension as previously described (11). Fivefold-concentrated E. coli whole-cell proteins were prepared as described above.

Human sera, rabbit sera, and monoclonal antibodies.

A panel of reference sera from North American individuals with 42 documented cases of Lyme disease and five control sera was provided by Barbara Johnson (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], Fort Collins, Colo.). The cases were clinically classified into the stages of early localized or disseminated and persistent infection according to previously described guidelines (49). Additional patient sera included in this study were from four Swiss individuals with disseminated Lyme disease (provided by Peter Erb, Institute for Medical Microbiology, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland) and a New Jersey patient with chronic Lyme arthritis (provided by Lisa Dever, Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Orange, N.J.). Sera from seven healthy adults living in an area where Lyme disease is not endemic and a commercially available pool of normal human sera (Omega Scientific) were used as additional controls.

Polyclonal Bdr antisera were raised in New Zealand White rabbits by immunization with gel-purified antigen. Briefly, rBdr proteins were purified from SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad Mini-Protean system). Gel fragments containing the protein bands identified by Coomassie blue staining were ground and suspended by addition of PBS (4). A suspension containing approximately 50 μg of recombinant protein emulsified in either complete or incomplete Freund’s adjuvant was used for the initial immunization or the boost (2 weeks postimmunization), respectively. Rabbits were bled 4 weeks postimmunization. As a control, rabbits were immunized with gel fragments containing E. coli proteins similar in size to the particular Bdr proteins. Polyclonal rabbit serum against lipidated OspA (anti-OspA) was a kind gift from Bob Huebner (Pasteur Mérieux Connaught, Swiftwater, Pa.). The anti-OspC mouse monoclonal antibody (L22 1C3 [60]) was kindly provided by Bettina Wilske (Max von Pettenkofer Institute for Hygiene and Medical Microbiology, University of Munich, Munich, Germany).

SDS-PAGE and Western immunoblot analysis.

Proteins were separated and visualized on SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels as described above. For Western immunoblots, proteins were electrotransferred (Bio-Rad Trans-Blot) to nitrocellulose membranes (Immobilon-NC; Millipore). Membranes were rinsed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 20 mM Tris, 500 mM NaCl [pH 7.5]) and either air dried or processed directly; 5% dry milk in TBST (TBS with 0.05% Tween 20) was used for membrane blocking and subsequent incubations (1 h each), and TBST was used for intermittent washes. Human patient and control sera were used at 1:100 dilutions, rabbit antisera were used at 1:500 (anti-Bdr) and 1:5,000 (anti-OspA) dilutions, and mouse monoclonal antibody hybridoma supernatants (anti-OspC) were used at a 1:10 dilution. Alkaline phosphatase-conjugated protein A/G (ImmunoPure protein A/G-calf intestinal phosphatase conjugate; 1:5,000; Pierce) as the second ligand and a stabilized alkaline phosphatase substrate solution (1-Step NBT/BCIP; Pierce) were used for colorimetric detection.

IFA and GIA.

For indirect immunofluorescence assays (IFA) with unfixed cells, B. burgdorferi cells were washed as described above, resuspended in PBS-Mg containing 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (PBS-Mg-BSA) to a concentration of 2 × 107 cells/ml, and incubated with dilutions of polyclonal rabbit sera at room temperature (RT) for 1 h with gentle rotation. After a wash with PBS-Mg-BSA, the cells were suspended in a 1:15 dilution of the secondary antibody, fluorescein-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (heavy plus light chain) [IgG(H+L); Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories], and incubated for 30 min. Subsequently, the cell suspension was adjusted to a volume of 300 μl with PBS-Mg-BSA and mounted for microscopy.

For IFA with fixed cells, spirochetes were suspended with sheep erythrocytes in 50% PBS–50% fetal calf serum (Gibco BRL). Thin smears of the mixture were made on glass slides, air dried, and fixed in 100% methanol. Slides were blocked with TBS–1% BSA for 5 min, spotted with dilutions of polyclonal rabbit serum, and incubated at RT in a wet chamber for 1 h. After three washes with TBS, the slides were incubated with a 1:20 dilution of the above secondary antibody for 30 min, washed in TBS, air dried, and mounted for microscopy, using a fluorescence quenching medium (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). Microscopy was performed with a Zeiss Axioskop epifluorescence microscope. Images were captured with an Oncor Imaging system (software version 2.01).

The ability of rabbit polyclonal antibodies to inhibit growth of B. burgdorferi in vitro was assessed by a growth inhibition assay (GIA) (40), using a slightly modified protocol (35).

ELISA.

Tissue culture flat-bottom 96-well plates (Costar) were coated overnight with rBdrA (200 ng/well) in carbonate buffer and blocked with 1% dried nonfat milk in PBS pH 7.4 (1% milk–PBS) for 2 h. Subsequently, the plates were incubated for 2 h with dilutions of sera in 1% milk–PBS followed by a 1-h incubation with a 1:1,000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-human IgG(H+L) antibodies (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories). All incubations were carried out at RT with intermittent washes with PBS pH 7.4. Detection was carried out in the dark, using 1 mg of Sigma 104 phosphatase substrate per ml in DEA buffer (9.7% diethanolamine, 0.01% MgCl2, 0.02% sodium azide [pH 9.8]). Plates were read on a SPECTRAmax 340 microplate reader (Molecular Devices) at 405 nm, using 490 nm as reference, and analyzed with the SOFTmax PRO software package (version 1.2.0 for Macintosh). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) titer values 3 standard deviations (SD) above the mean of the negative control values were considered positive.

RESULTS

Comparative analysis of the Bdr protein family.

To further define the common and divergent characteristics of the ORF-E-related protein family, we comprehensively compared the known paralogs and orthologs. Including the two initially identified copies on one of the multiple homologous cp32s and the related lp56 of B. burgdorferi B31 (ORF-E [64]), a total of 29 related sequences have been determined, mostly as part of the B. burgdorferi B31 genome sequencing project but also in other B. burgdorferi sensu lato strains and the relapsing fever spirochetes B. hermsii and B. turicatae (Table 1). Strain B31 ORFs BBF03 and BBJ10 (28) are likely pseudogenes, since they do not possess a consensus Shine-Dalgarno sequence upstream of the AUG start codon, and were therefore excluded from further analysis.

The nomenclature of the ORF-E-related proteins has been rather divergent. Besides the original ORF-E, one of the more commonly used names has been Rep (referring to the protein’s short repeats). In other well-studied prokaryotes, though, this designation is used solely for proteins involved in DNA replication, and a bona fide Rep homolog (BB0607) has been identified on the chromosome of B. burgdorferi B31 (28). To avoid further confusion and to consolidate the nomenclature for the direct repeat protein family, we propose an unambiguous term Bdr, referring to the common features of their members and their presence in several Borrelia species.

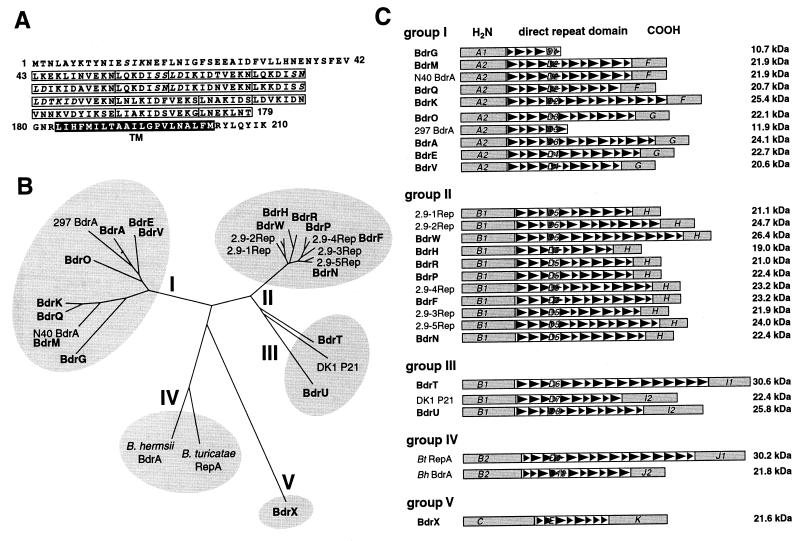

Some of the common characteristics of a small subset of sequences were described previously (19, 62), and in general apply to all Bdr proteins described here. Bdr homologs possess a central direct repeat domain flanked by an amino-terminal domain and, except in the trunctated BdrG and the 297 Bdr proteins, a carboxy-terminal domain (Fig. 1A and C). While the proteins’ predicted molecular masses vary from 10.7 to 30.6 kDa, the predicted pIs are all acidic, varying from 4.39 to 6.20 (Table 1). Putative phosphorylation sites were first noticed by Theisen in the B. afzelii DK1 ortholog p21 (57) and can also be found, primarily in the central repeat region, of all homologs (e.g., six sites in BdrA [Fig. 1A]). Chou and Fasman secondary structure predictions suggest that all homologs contain long stretches of alpha helices.

FIG. 1.

Features and comparison of Bdr paralog and ortholog proteins. (A) Features of Bdr proteins, showing B. burgdorferi B31 BdrA as an example. Amino acid positions: 1 to 42, N-terminal domain; 43 to 179, central direct repeat domain; 180 to 210, C-terminal domain. Residues in italics are putative phosphorylation sites. Boxed rectangles indicate the 7- and 11-aa repeat units. The black bar with white letters indicates the predicted C-terminal transmembrane (Tm) domain. (B) Comparative analysis of known Bdr paralogs and orthologs (Table 1). B. burgdorferi B31 paralogs are listed in bold. Protein sequence alignments were bootstrapped by using Clustal X. An unrooted phylogenetic tree was drawn by using the PHYLIP DRAWTREE algorithm. (C) Comparison of Bdr paralogs and orthologs. Sequences are listed according to the homology groups in panel B. Levels of homology of N and C termini are indicated with letters and numbers as follows: different letters separate groups of sequences with more than 30% amino acid identity within a group; different numbers separate subgroups of sequences with more than 60% amino acid identity among members. Boxed shaded triangles indicate the 7- and 11-aa repeat units in the central direct repeat domain.

Comparison of the full-length Bdr homolog sequences by alignment and comparative analysis using Clustal X and PHYLIP computer algorithms, showed that they formed five major branches of a bootstrapped unrooted tree (Fig. 1B); group I comprised cp32 and lp56 Bdr homologs related to the original B31 ORF-E (BdrA [64]), whereas group II included Bdr homologs on the cp32s and lp56 closely related to the 2.9Rep sequences identified in B. burgdorferi 297 (37). The paralogs carried by two 28-kb linear plasmids of B31 were found in a widely branched group III together with the ortholog described for B. afzelii (57). Group IV contained the two Bdr orthologs described for tick-borne relapsing fever spirochetes (19, 51), while BdrX, a paralog found on the 36-kb linear plasmid of strain B31, formed a distant fifth branch (Fig. 1B).

Differences in the amino and carboxy termini appear to be the main contributors to this diversity. In alignments, the 27 amino termini fell into three groups (A, B, and C) with less than 30% amino acid identity between each group. With the exception of BdrX, which diverges considerably from other homologs in all domains (approximately 10% amino acid identity), the strain B31 paralogs have at least 26% identical amino acid residues among each other in the N-terminal domain. Computer analysis did not reveal any motifs such as signal peptidase cleavage or lipidation sites. The carboxy termini are even more heterogeneous, with six groups (F to K) of less than 30% identity between each group (Fig. 1C). The strain B31 paralogs share only 10% identical amino acids residues. Two paralogs (BdrG and strain 297 BdrA) are truncated and thus lack the carboxy-terminal domain. Intriguingly, however, all 25 carboxy termini, as different as their amino acid sequences might be, are predicted to have a transmembrane domain by the TMPred algorithm (33). The highest degree of overall homology between the Bdr proteins can be found in the central direct repeat domain, which is composed of units with periodicities of either 7 or 11 amino acids (aa) (Fig. 1A). All homologs except BdrX (group E) share more than 30% of common amino acids residues in this region (group D); the strain B31 paralogs share even 46%. Interestingly, the number of repeat units, and therefore the length of this domain, can vary dramatically between the homologs. The length of this domain is the main contributor to the protein size differences (Fig. 1C).

Heterologous expression and cross-reactivity of BdrA and BdrV.

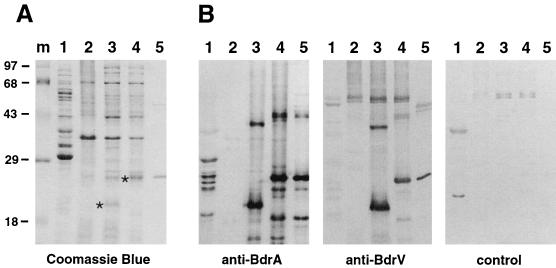

Based on the common features and homologies in the direct repeat domain, we surmised that the Bdr proteins could constitute a cross-reactive protein family. To test this hypothesis with two closely related proteins, we chose two previously cloned group I paralogs from strain B31, BdrA and BdrV (Table 1; Fig. 1B) (64), for overexpression in E. coli. Whole-cell preparations of the E. coli harboring the expression construct pWRZ101 or pWRZ102 showed that BdrA and BdrV could be expressed in this system (Fig. 2A). The observed sizes corresponded to the expected molecular masses of BdrA (24.1 kDa) and BdrV (20.6 kDa).

FIG. 2.

Heterologous expression and cross-reactivity of B31 Bdr proteins. (A) Coomassie blue-stained SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel. Lanes: m, molecular weight marker (Gibco high molecular weight); 1, B. burgdorferi B31 whole-cell lysate; 2, E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS)(pET29b) whole-cell lysate; 3, E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS)(pWRZ102) whole-cell lysate (expressing rBdrV); 4, E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS)(pWRZ101) whole-cell lysate (expressing rBdrA); 5, purified rBdrA. Asterisks indicate rBdrV and rBdrA. (B) Western immunoblot with anti-BdrA, anti-BdrV, and control rabbit sera (1:500). Lanes are as in panel A.

We gel purified rBdrA and rBdrV and used these preparations to raise polyclonal antisera in rabbits. These two antisera, anti-BdrA and anti-BdrV, as well as a control serum from a sham-immunized rabbit were used in immunoblot analyses of whole-cell lysates of E. coli carrying either pET29b (control), pWRZ101 (expressing rBdrA), or pWRZ102 (expressing rBdrV). Whereas the control serum did not react (Fig. 2B), anti-BdrA reacted with the rBdrA and rBdrV proteins present in whole-cell lysates but not with any proteins of the E. coli(pET29b) control (Fig. 2B). The additional bands seen in whole-cell lysates of E. coli carrying pWRZ101 and pWRZ102 are most likely either multimers or degradation products, as they are also detected in a column-purified rBdrA fraction (see Fig. 2B and below). Reciprocal results were obtained in experiments using anti-BdrV, which also recognized BdrA, although the reactivity of the antiserum was not as strong (Fig. 2B). These experiments indicated that antibodies against two closely related proteins of this family cross-react.

Further characterization of Bdr proteins.

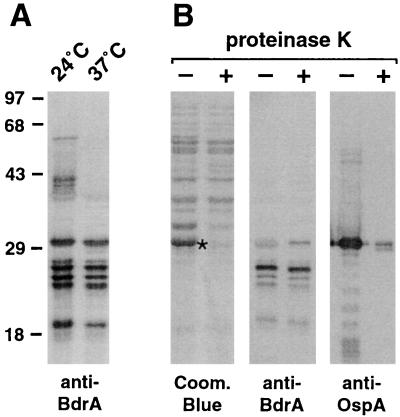

Since the expression of many immunogenic Borrelia proteins (e.g., OspC) is differentially regulated by environmental factors such as temperature, we assayed for differences in Bdr expression in cultured B. burgdorferi B31 in cultures grown at a constant temperatures of either 24 or 37°C. As shown in Fig. 3A, Bdr expression was essentially the same at 24 and 37°C. Interestingly, protein bands in the 35- to 60-kDa range, likely corresponding to Bdr paralog dimers, were seen in lysates of cells grown at 24°C but not at 37°C. We repeated the experiment, this time assaying for Bdr expression immediately after a temperature shift from 23 to 35°C, which leads to an upregulation of OspC (44, 55). As expected, we detected OspC at 35°C but not at 23°C. The level of Bdr proteins, however, remained constant under these conditions as well (results not shown).

FIG. 3.

Lack of temperature-dependent expression and proteinase K susceptibility of Bdr proteins. (A) Western immunoblot of an SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel with whole-cell lysates of B. burgdorferi B31 grown at 24 or 37°C probed with anti-BdrA antiserum (1:500). Protein sizes indicated to the left are derived from a molecular weight marker (Gibco high molecular weight). (B) Proteinase K susceptibility of Bdr proteins. Coom. Blue, Coomassie blue-stained SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel with whole-cell lysates of B. burgdorferi B31 either untreated (−) or previously treated (+) with proteinase K (200 μg/ml of cell suspension); anti-BrdA and anti-OspA, Western immunoblots of gels with anti-BdrA (1:500) and anti-OspA (1:20,000) antisera. An asterisk indicates OspA.

We also assessed the surface exposure of Bdr protein paralogs by their proteinase K accessibility. B. burgdorferi B31 cells were incubated with proteinase K at a concentration removing known surface-exposed proteins such as OspA (200 μg/ml of cell suspension) (11). While OspA was clearly removed by this treatment, Western blots with anti-BdrA showed that none of the Bdr paralogs were susceptible to proteolysis under these conditions (Fig. 3B). This finding suggested that Bdr proteins are not surface exposed. Note that one of the B. burgdorferi B31 paralogs (BdrT, 30.6 kDa) comigrates with OspA. While a diffuse reacting protein band can be seen before protease treatment, the corresponding band becomes more apparent after the removal of OspA.

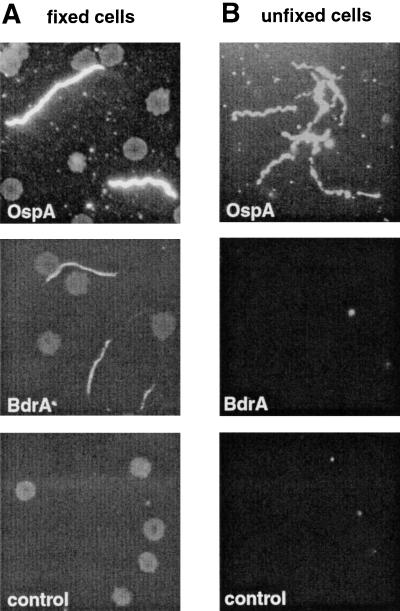

In an alternative approach, we tested for antibody accessibility of the Bdr proteins by IFA of unfixed intact and methanol-fixed permeabilized spirochetes and by GIA. GIA titers obtained with anti-BdrA and the negative control serum were identical (≤1:16), while anti-OspA inhibited growth at a titer of 1:4,096. In agreement with the previous results, intact spirochetes did not bind antibodies directed against BdrA yet reacted readily with antibodies against OspA. On the other hand, spirochetes permeabilized by fixation reacted with both anti-BdrA and anti-OspA polyclonal antibodies (Fig. 4). This also supports the previously described immunoblot data showing that Bdr proteins are expressed by culture-grown B. burgdorferi.

FIG. 4.

Immunofluorescence microscopy of fixed and unfixed B. burgdorferi cells. (A) Methanol-fixed, permeabilized B. burgdorferi B31 cells reacted with anti-OspA (1:1,000), anti-BdrA (1:200), and control (1:200) polyclonal rabbit sera. Secondary antibody was a fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled goat anti-rabbit antibody. (B) Unfixed, intact B. burgdorferi B31 cells reacted with anti-OspA (1:1,000), anti-BdrA (1:100), and control (1:100) polyclonal rabbit sera.

Cross-reactive Bdr proteins in B. burgdorferi B31.

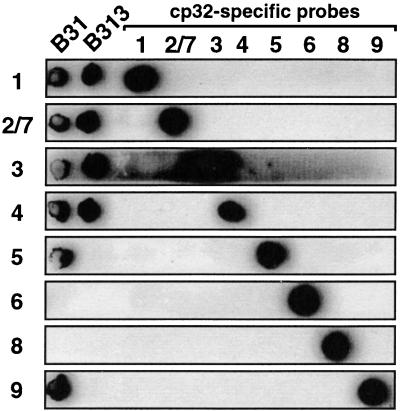

In the immunoblot experiments described above, we also included whole-cell lysates of B. burgdorferi B31. Interestingly, anti-BdrA detected several protein bands with estimated sizes of 30.5, 28, 27, 25.5, 24.5, 24, and 19.5 kDa (Fig. 2B). On a Coomassie blue-stained gel, however, the corresponding bands were barely detectable (Fig. 2A). The range of protein band sizes corresponds with the expected sizes of Bdr paralogs described in this strain (Table 1 and Fig. 1C). To corroborate this observation and to audit the antigen specificity of anti-BdrA, we repeated the experiment including B. burgdorferi B313, a derivative of B31. This strain had been previously shown to lack several lp’s, including lp29 (i.e., the lp28s [28]), lp38 (lp36 and lp38), and lp49 (lp54 and lp56), and thus to lack bdrT, bdrU, bdrX, bdrV, and bdrW. Circular plasmids such as cp30 (i.e., the multiple cp32s), however, were still present (41). To determine the B313 complement of bdr paralogs, we used cp32-specific DNA probes (22, 56) and PCR oligonucleotide primers (52, 53) to determine its cp32 plasmid profile.

These experiments indicated that our high-passage B31 was lacking cp32-6, cp32-7, and cp32-8, and its derivative B313 in addition had lost cp32-5 and cp32-9 (Fig. 5). B313 thus contains only the complements of bdrA, bdrC, bdrD, bdrE, bdrF, bdrG, and bdrH carried by cp32-1, cp32-2, cp32-3, and cp32-4. cp32-2 has not been sequenced in its entirety, and therefore the bdrC and bdrD sequences are not available. The available sequences of cp32-2 and cp32-7, however, have proven to be almost identical (in fact, the two plasmids may be incompatible [53]), letting us assume that their bdr paralogs (bdrC/bdrM and bdrD/bdrN) are very similar if not identical. In that case, B313 would express proteins with the following calculated sizes: BdrA, 24.1 kDa; BdrC, 21.9 kDa; BdrD, 22.4 kDa; BdrE, 22.7 kDa; BdrF, 23.2 kDa; BdrG, 10.7 kDa; and BdrH, 19.0 kDa. Two major bands of approximately 25.5 and 24 kDa can be seen in whole-cell lysates of B313, likely corresponding to BdrA and/or -F or BdrC, -D, and/or -E, respectively (Fig. 6B). While BdrG, a truncated and probably defective paralog, has likely run off the gel, the reason for the absence of BdrH remains unclear. Together, these results indicated that antibodies raised against BdrA not only specifically detect closely related, i.e., group I, paralogs like BdrV, but also group II and III Bdr paralogs of strain B31. Furthermore, they suggested that several Bdr paralogs are expressed simultaneously by cultured B. burgdorferi.

FIG. 5.

cp32 plasmid profile of B. burgdorferi B31 derivative B313. Plasmid-enriched DNA of B. burgdorferi B31 and its derivative B313 was dot blotted with nucleotide probes (1 through 9) specific for the multiple homologous 32-kb-long circular plasmids (cp32-1 through cp32-9). Probes were also blotted as a control for probe specificity. Note that probe 2/7 does not discriminate between cp32-2 and cp32-7. PCR analysis with oligonucleotide primers specific for cp32-2- or cp32-7 revealed that both B31 and B313 carried cp32-2 but not cp32-7 (see text).

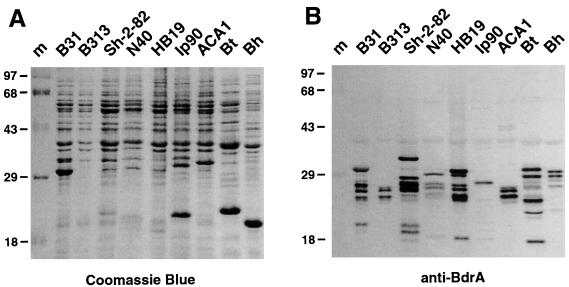

FIG. 6.

Cross-reacting Bdr paralog and ortholog proteins in other Borrelia isolates. (A) Coomassie blue-stained SDS–12% polyacrylamide gel. Borrelia isolates are indicated above the lanes: m, molecular weight protein marker (Gibco high molecular weight); B. burgdorferi sensu stricto isolates B31, B313, Sh-2-82, N40, and HB19; B. garinii Ip90; B. afzelii ACA1; tick-borne relapsing fever isolates B. turicatae Oz1 (Bt) and B. hermsii HS1 (Bh). (B) Western immunoblot of an identical gel with anti-BdrA antiserum (1:500). Lanes are as in panel A.

Cross-reactive Bdr proteins in Borrelia species.

As mentioned above, genes belonging to the B. burgdorferi B31 Bdr family have also been found in other Lyme disease or relapsing fever Borrelia isolates (Table 1). We therefore checked for the presence of cross-reacting proteins in three additional B. burgdorferi strains, Sh-2-82, N40, and HB19, as well as in B. garinii Ip90, B. afzelii ACA1, and two relapsing fever spirochete species, B. turicatae Oz1 and B. hermsii HS1. Immunoblots with anti-BdrA against whole-cell lysates revealed proteins in every isolate tested, ranging in size from approximately 17.5 to 33 kDa (Fig. 6B). This indicates that the cross-reactivity of the Bdr protein family also extends to other Borrelia species in general. Intriguingly, each of the isolates had a distinct immunoreactive protein pattern ranging from, e.g., only one 27-kDa protein band in Ip90 to seven bands ranging from 18 to 30 kDa in HB19.

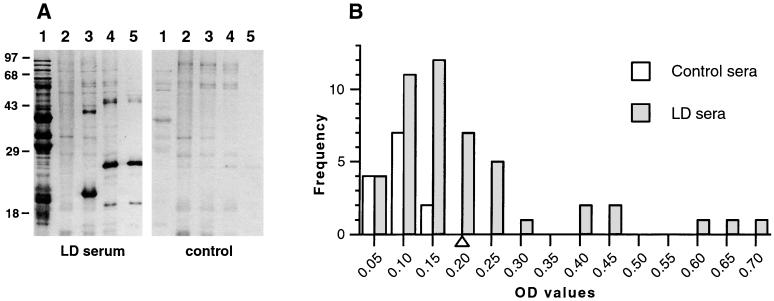

Antibody response to Bdr in Lyme disease.

Many of the plasmid-encoded, immunogenic proteins studied so far have proven to be antigens expressed at one point during the parasitic life cycle of Borrelia, either in the tick vector or in the vertebrate host. We therefore determined whether Bdr was immunogenic during the course of Lyme disease. For that purpose, we obtained 4 European and 43 American Lyme disease patient sera as well as 13 human control sera; 42 of the patient sera were from a well-characterized CDC Lyme disease patient serum panel. The sera were first used in an immunoblot assay against whole-cell lysates of E. coli expressing rBdrA and rBdrV. None of the control sera produced reactive bands the sizes of rBdrA and rBdrV, whereas 51% (24 of 47) (chi square = 9.04, P = 0.003) of the patient sera reacted with both BdrA and BdrV, indicating that Bdr proteins are indeed immunogenic. Representative immunoblots for a positive serum as well as a negative control serum are shown in Fig. 7A.

FIG. 7.

Western immunoblots and ELISA with Lyme disease patient sera. (A) Left, Western immunoblot with a representative positive Lyme disease (LD) patient serum (1:100). Lane 1, B. burgdorferi B31 whole-cell lysate; lane 2, E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS)(pET29b) whole-cell lysate; lane 3, E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS)(pWRZ102) whole-cell lysate (expressing rBdrV); lane 4, E. coli BL21(DE3)(pLysS)(pWRZ101) whole-cell lysate (expressing rBdrA); lane 5, purified rBdrA. Right, Western immunoblot of an identical blot with a representative human control serum. (B) Distribution of rounded ELISA OD values obtained with LD patient and control sera. A triangle on the x axis indicates the cutoff OD (mean of control sera values plus 3 SD = 0.20) for positive sera.

For a more quantitative analysis of the antibody response to Bdr, we used an ELISA. As the expression levels of Bdr proteins are low, at least in cultured Borrelia species, we used purified rBdrA as a target in an IgG-specific ELISA. Preliminary experiments with Western blot-negative and -positive sera showed that rBdrA concentrations of 200 ng/well and serum dilutions of 1:100 would yield the most discriminating OD405 values. The same panel of sera used for the immunoblot analysis were analyzed. The cutoff between negative and positive sera was conservatively defined as the mean OD value of control sera plus 3 SD i.e., 0.20. Figure 7B shows the distribution of the OD values obtained with the human serum panel. All control sera were negative; 43% (20 of 47) (chi square = 6.49, P = 0.011) of the patient sera tested were positive. According to guidelines described elsewhere (49), the serum panel can be further divided into sera from patients with (i) early localized or (ii) disseminated or persistent Lyme disease; 37% (14 of 38) of the former sera gave a positive result, in contrast to 66% (6 of 9) of the latter (P = 0.142, Fisher exact test). These data indicate that Bdr proteins are expressed by B. burgdorferi in vivo and recognized by the humoral immune response during Lyme disease.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we further characterized the Borrelia spp. Bdr protein family. The genes encoding these proteins so far have been found exclusively on plasmids. B. burgdorferi B31, e.g., carries a large number of bdr paralogs on several lp’s as well as the multiple homologous 32-kb-long cp’s (20, 28). Interestingly, most of the cp32s carry two bdr copies in two different plasmid loci separated by approximately 5 kb (see below and reference 20). Related genes have been found on circular and linear plasmids of other B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates (1, 37, 54, 57) as well as relapsing fever spirochetes B. hermsii (51) and B. turicatae (19) (Table 1). So far, no homologs have been found in spirochetes other than Borrelia, such as Treponema pallidum (29), or in other prokaryotes, which suggests that this family of proteins is specific for the genus Borrelia.

All Bdr proteins have a characteristic central domain consisting of various numbers of tandem 7- and 11-aa repeat units and thereby alter in size from about 18 to 31 kDa. Another common feature is a variable yet structurally conserved C-terminal putative transmembrane domain. Our comparative analyses show that the currently known members of the Borrelia Bdr protein family fall into five major homology groups, mainly due to variations in their N- and C-terminal domains. Interestingly, the differentiation between homology groups is consistent with their respective linear or circular plasmid locations. Whereas group I and group II homologs are both found on the cp32s (and related plasmids), they are part of different loci: group I paralogs are part of the ORF-1-2-C-3-E locus (24, 64); group II paralogs are located approximately 5 kb upstream, as part of a locus related to the 2.9 locus identified in B. burgdorferi 297 (37).

We have shown that antibodies raised against two B31 Bdr paralogs from the same homology group, BdrA and BdrV, cross-react. Furthermore, anti-BdrA antibodies also detect related proteins in other B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates and relapsing fever spirochetes. We were able to account for all visible reactive protein bands in strain B31 as well as its derivative B313 by linking them to the encoding bdr paralogs, and the size ranges of proteins seen in the other isolates correspond with each other and the one seen in strain B31. This strongly suggests that the polyclonal antiserum used is specific for members of the Bdr protein family. Given the significant overall sequence variability of Bdr proteins, the observed cross-reactivity is likely due to the more conserved direct repeat domain.

Our studies with strain B31 indicate that several if not all Bdr paralogs are expressed by B. burgdorferi. Expression is likely contemporaneous, as is the case for the Erp proteins encoded downstream of the bdr paralogs (52). Under all conditions examined in this work and in a recent study with the B. turicatae ortholog (19), Bdr expression levels are constant and low compared to other Borrelia antigens. Expression is not upregulated in an OspC-like manner (55) by an increase in temperature. Nevertheless, there could be other environmental factors that lead to a transient upregulation of Bdr expression in the human host.

Several lines of evidence indicate that Bdr proteins are not surface exposed: in intact B. burgdorferi cells, they are not susceptible to proteolytic degradation by external proteinase K and inaccessible to polyclonal antibodies. Due to the lack of a periplasmic export sequence and the structurally conserved C-terminal predicted transmembrane domain, the proteins are predicted to be anchored in the cytoplasmic membrane. In a previous study, Bledsoe and colleagues isolated inner and outer membranes of B. burgdorferi B31 by isopycnic centrifugation (14). They found proteins 20 to 60 kDa in size that appeared to localize specifically to the inner membrane. Most of these proteins had apparent pIs more acidic than that of OspA. Intriguingly, two of the protein clusters identified by two-dimensional nonequilibrium pH gel electrophoresis–SDS-PAGE (II and III) formed a vertical ladder, indicating various sizes (approximately 15 to 32 kDa) but similar pIs. These parameters would agree with the predicted values for the Bdr paralogs expressed by this strain.

In the last part of this study, we showed that Bdr proteins are also expressed in vivo and recognized in the course of Lyme disease. Approximately half of the tested patient sera reacted with one or more Bdr proteins in immunoblots and an IgG-based ELISA. All of a statistically significant number of control sera were negative in both assays. Our data may suggest an increase in seroconversion from early localized to late disseminated Lyme disease. However, this is also true for several other B. burgdorferi antigens recognized in North American as well as European Lyme disease (23, 31), and this difference is not statistically significant due to the low number of sera from the latter patient group.

Among the immunodominant B. burgdorferi antigens are several outer surface proteins (OspA to -F), an outer membrane porin (p66), decorin- and fibronectin-binding proteins (DbpA and BBK32, respectively), a periplasmic flagellar protein (FlaB), a cytoplasmic membrane-associated protein (BmpA), heat shock proteins (DnaK and GroEL), and a protoplasmic cylinder-associated protein (p93) (23, 31). In comparison to these abundant proteins, the individual Bdr proteins are present in relatively scarce amounts in culture-grown B. burgdorferi and therefore might go undetected in standard diagnostic immunoblots. In a recent study, Western blots with patient sera were subjected to densitometric analysis revealing approximately 40 visually distinguishable bands, including several sofar uncharacterized and unassigned immunogenic proteins in the 20- to 30-kDa range (31). It is possible that Bdr paralogs account for some of these protein bands. The polyclonal anti-Bdr sera described here may be helpful in further analysis.

The function of the Bdr proteins remains unclear, as our current knowledge of Lyme disease and relapsing fever bdr homologs is limited. Proteins with similarly sized repeat motifs can be found in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic pathogens. Among others are the surface-located IgA proteases of several Streptococcus species (38), a cell surface antigen of Bacteroides forsythus (45), and a repetitive organellar protein of Plasmodium chabaudi (59). It has been proposed that repetitive domains of antigens direct the immune response towards a less protective T-cell-independent B-cell activation (42). However, a similar function for the Bdr proteins is at odds with the observed lack of surface exposure in vitro.

Alternatively, the presence of some of the bdr genes in plasmid loci containing homologs for plasmid segregation and partition proteins (8, 53, 64) may suggest that Bdr paralogs are part of this machinery. As is the case for other genes in this locus, the observed sequence divergence and thus plasmid specificity of each Bdr paralog might ensure that each cp32 plasmid is segregated properly, resolving plasmid incompatibility issues. The predicted subcellular location of Bdr proteins in the cytoplasmic membrane could be a further hint in this direction. The significance of these and other predicted Bdr features such as the putative phosphorylation sites separated by multiples of alpha-helical turns (19, 57, 62) remains unknown. Together, these questions warrant further investigation of the role of Bdr proteins in both Lyme disease and relapsing fever as well as in their respective etiological agents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Brian Stevenson for the DNA probes, PCR primers, and protein samples, Barbara Johnson and Peter Erb for the human sera, Bob Huebner for the anti-OspA serum, and Bettina Wilske for the anti-OspC monoclonal antibody. We are grateful to Cath Luke for performing the GIA and to Jennifer Miller, Dave Shraga, and Elena Cuaresma for technical assistance. We acknowledge Brian Stevenson, Cath Luke, Jonas Bunikis, and Sherwood Casjens for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control (cooperative agreement U50/CCU914771 to A.G.B.) and the Swiss National Science Foundation (grant 32-39441.93/2 to J.M.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Akins D R, Bourell K W, Caimano M J, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. A new animal model for studying Lyme disease spirochetes in a mammalian host-adapted state. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:2240–2250. doi: 10.1172/JCI2325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akins D R, Caimano M J, Yang X, Cerna F, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Molecular and evolutionary analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi 297 circular plasmid-encoded lipoproteins with OspE- and OspF-like leader peptides. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1526–1532. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1526-1532.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Åsbrink E, Hovmark A, Hederstedt B. The spirochetal etiology of acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans Herxheimer. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 1984;64:506–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baranton G, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Boerlin P, Piffaretti J C, Assous M, Grimont P A D. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:378–383. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barbour A G. Linear DNA of Borrelia species and antigenic variation. Trends Microbiol. 1993;1:236–239. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90139-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbour A G. Plasmid analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:475–478. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.3.475-478.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbour A G, Carter C J, Bundoc V, Hinnebusch J. The nucleotide sequence of a linear plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi reveals similarities to those of circular plasmids of other prokaryotes. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6635–6639. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6635-6639.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbour A G, Garon C F. Linear plasmids of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi have covalently closed ends. Science. 1987;237:409–411. doi: 10.1126/science.3603026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barbour A G, Hayes S F. Biology of Borrelia species. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:381–400. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.381-400.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barbour A G, Tessier S L, Hayes S F. Variation in a major surface protein of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1984;45:94–100. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.94-100.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barbour A G, Tessier S L, Todd W J. Lyme disease spirochetes and ixodid tick spirochetes share a common surface antigenic determinant defined by a monoclonal antibody. Infect Immun. 1983;41:795–804. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.795-804.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baril C, Richaud C, Baranton G, Saint Girons I S. Linear chromosome of Borrelia burgdorferi. Res Microbiol. 1989;140:507–516. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(89)90083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bledsoe H A, Carroll J A, Whelchel T R, Farmer M A, Dorward D W, Gherardini F C. Isolation and partial characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi inner and outer membranes by using isopycnic centrifugation. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7447–7455. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.24.7447-7455.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borrelia burgdorferi Genome Database. 16 October 1998, revision date. [Online.] The Institute for Genomic Research. http://www.tigr.org/tdb/mdb/bbdb/bbdb.html. [2 April 1999, last date accessed].

- 16.Burgdorfer W, Barbour A G, Hayes S F, Benach J L, Grunwaldt E, Davis J P. Lyme disease—a tick-borne spirochetosis? Science. 1982;216:1317–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.7043737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cadavid D, Thomas D D, Crawley R, Barbour A G. Variability of a bacterial surface protein and disease expression in a possible mouse model of systemic Lyme borreliosis. J Exp Med. 1994;179:631–642. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Canica M M, Nato F, du Merle L, Mazie J C, Baranton G, Postic D. Monoclonal antibodies for identification of Borrelia afzelii sp. nov. associated with late cutaneous manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25:441–448. doi: 10.3109/00365549309008525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carlyon J A, Marconi R T. Cloning and molecular characterization of a multicopy, linear plasmid-carried, repeat motif-containing gene from Borrelia turicatae, a causative agent of relapsing fever. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4974–4981. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4974-4981.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casjens, S., and C. M. Fraser. Personal communication.

- 21.Casjens S, Murphy M, DeLange M, Sampson L, van Vugt R, Huang W M. Telomeres of the linear chromosomes of Lyme disease spirochaetes: nucleotide sequence and possible exchange with linear plasmid telomeres. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:581–596. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6051963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Casjens S, van Vugt R, Tilly K, Rosa P A, Stevenson B. Homology throughout the multiple 32-kilobase circular plasmids present in Lyme disease spirochetes. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:217–227. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.1.217-227.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dressler F, Whalen J A, Reinhardt B N, Steere A C. Western blotting in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:392–400. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn J J, Buchstein S R, Butler L-L, Fisenne S, Polin D S, Lade B N, Luft B J. Complete nucleotide sequence of a circular plasmid from the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:2706–2717. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.9.2706-2717.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferdows M S, Barbour A G. Megabase-sized linear DNA in the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5969–5973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferdows M S, Serwer P, Griess G A, Norris S J, Barbour A G. Conversion of a linear to a circular plasmid in the relapsing fever agent Borrelia hermsii. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:793–800. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.3.793-800.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Kantor F S, Flavell R A. Protection of mice against the Lyme disease agent by immunizing with recombinant OspA. Science. 1990;250:553–556. doi: 10.1126/science.2237407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fraser C M, Casjens S, Huang W M, Sutton G G, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum K A, Dodson R, Hickey E K, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb J F, Fleischmann R D, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage A R, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams M D, Gocayne J, Venter J C. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fraser C M, Norris S J, Weinstock G M, White O, Sutton G G, Dodson R, Gwinn M, Hickey E K, Clayton R, Ketchum K A, Sodergren E, Hardham J M, McLeod M P, Salzberg S, Peterson J, Khalak H, Richardson D, Howell J K, Chidambaram M, Utterback T, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Cotton M D, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science. 1998;281:375–388. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guina T, Oliver D B. Cloning and analysis of a Borrelia burgdorferi membrane-interactive protein exhibiting haemolytic activity. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:1201–1213. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.4291786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hauser U, Lehnert G, Lobentanzer R, Wilske B. Interpretation criteria for standardized Western blots for three European species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1433–1444. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1433-1444.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinnebusch J, Barbour A G. Linear- and circular-plasmid copy numbers in Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5251–5257. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.16.5251-5257.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hofmann K, Stoffel W. TMbase, a database of membrane spanning protein segments. Biol Chem Hoppe Seyler. 1993;347:166. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitten T, Barbour A G. The relapsing fever agent Borrelia hermsii has multiple copies of its chromosome and linear plasmids. Genetics. 1992;132:311–324. doi: 10.1093/genetics/132.2.311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luke, C. J., M. A. Marshall, J. M. Zahradnik, B. E. Menefee, and A. G. Barbour. Characterization by growth inhibition assay of sera of humans vaccinated with recombinant OspA and/or infected with Borrelia burgdorferi. Submitted for publication. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Margolis N, Hogan D, Tilly K, Rosa P A. Plasmid location of Borrelia purine biosynthesis gene homologs. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6427–6432. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.21.6427-6432.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Porcella S F, Popova T G, Akins D R, Li M, Radolf J D, Norgard M V. Borrelia burgdorferi supercoiled plasmids encode multicopy tandem open reading frames and a lipoprotein family. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3293–3307. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3293-3307.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poulsen K, Reinholdt J, Jespersgaard C, Boye K, Brown T A, Hauge M, Kilian M. A comprehensive genetic study of streptococcal immunoglobulin A1 protease: evidence for recombination within and between species. Infect Immun. 1998;66:181–190. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.181-190.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ras N M, Lascola B, Postic D, Cutler S J, Rodhain F, Baranton G, Raoult D. Phylogenesis of relapsing fever Borrelia spp. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:859–865. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sadziene A, Thompson P A, Barbour A G. In vitro inhibition of Borrelia burgdorferi growth by antibodies. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:165–172. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sadziene A, Wilske B, Ferdows M S, Barbour A G. The cryptic ospC gene of Borrelia burgdorferi B31 is located on a circular plasmid. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2192–2195. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2192-2195.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schofield L. On the function of repetitive domains in protein antigens of Plasmodium and other eukaryotic parasites. Parasitol Today. 1991;7:99–105. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(91)90166-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schwan T G, Burgdorfer W, Schrumpf M E, Karstens R H. The urinary bladder, a consistent source of Borrelia burgdorferi in experimentally infected white-footed mice (Peromyscus leucopus) J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:893–895. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.5.893-895.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwan T G, Piesman J, Golde W T, Dolan M C, Rosa P A. Induction of an outer surface protein on Borrelia burgdorferi during tick feeding. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2909–2913. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sharman A, Sojar H T, Glurich I, Honma K, Kuramitsu H K, Genco R J. Cloning, expression, and sequencing of a cell surface antigen containing a leucine-rich repeat motif from Bacteroides forsythus ATCC 43037. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5703–5710. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5703-5710.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Simpson W J, Garon C F, Schwan T G. Analysis of supercoiled circular plasmids in infectious and non-infectious Borrelia burgdorferi. Microb Pathog. 1990;8:109–118. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(90)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simpson W J, Garon C F, Schwan T G. Borrelia burgdorferi contains repeated DNA sequences that are species specific and plasmid associated. Infect Immun. 1990;58:847–853. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.4.847-853.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stålhammar-Carlemalm M, Jenny E, Gern L, Aeschlimann A, Meyer J. Plasmid analysis and restriction fragment length polymorphisms of chromosomal DNA allow a distinction between Borrelia burgdorferi strains. Zentralbl Bakteriol. 1990;274:28–39. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80972-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Steere A C. Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:586–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908313210906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Steere A C. Lyme disease: a growing threat to urban populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2378–2383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stevenson, B. Personal communication.

- 52.Stevenson B, Bono J L, Schwan T G, Rosa P. Borrelia burgdorferi Erp proteins are immunogenic in mammals infected by tick bite, and their synthesis is inducible in cultured bacteria. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2648–2654. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.6.2648-2654.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stevenson B, Casjens S, Rosa P. Evidence of past recombination events among the genes encoding the Erp antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi. Microbiology. 1998;144:1869–1879. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-7-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stevenson B, Casjens S, van Vugt R, Porcella S F, Tilly K, Bono J L, Rosa P. Characterization of cp18, a naturally truncated member of the cp32 family of Borrelia burgdorferi plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:4285–4291. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.13.4285-4291.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stevenson B, Schwan T G, Rosa P A. Temperature-related differential expression of antigens in the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4535–4539. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4535-4539.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stevenson B, Tilly K, Rosa P A. A family of genes located on four separate 32-kilobase circular plasmids in Borrelia burgdorferi B31. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3508–3516. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3508-3516.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Theisen M. Molecular cloning and characterization of nlpH, encoding a novel, surface-exposed, polymorphic, plasmid-encoded 33-kilodalton lipoprotein of Borrelia afzelii. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:6435–6442. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.22.6435-6442.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Werner E B E, Taylor W R, Holder A A. A Plasmodium chabaudi protein contains a repetitive region with a predicted spectrin-like structure. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;94:185–196. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Jauris S, Hofmann A, Pradel I, Soutschek E, Schwab E, Will G, Wanner G. Immunological and molecular polymorphisms of OspC, in immunodominant major outer surface protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2182–2191. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2182-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu Y, Johnson R C. Analysis and comparison of plasmid profiles of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2679–2685. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.10.2679-2685.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zückert, W. R., J. A. Carlyon, R. T. Marconi, and J. Meyer. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 63.Zückert W R, Filipuzzi-Jenny E, Stålhammar-Carlemalm M, Meister-Turner J, Meyer J. Repeated DNA sequences on circular and linear plasmids of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. In: Axford J S, Rees D H E, editors. Lyme borreliosis. New York, N.Y: Plenum; 1994. pp. 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zückert W R, Meyer J. Circular and linear plasmids of Lyme disease spirochetes have extensive homology: characterization of a repeated DNA element. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:2287–2298. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.8.2287-2298.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]