Abstract

Workers and employers in the informal economy are often outside the scope of legal frameworks of occupational safety and health (OSH) service in South Asia. The present study aimed to find practical support measures to improve their safety and health. International Labour Organization’s participatory training activities in five selected informal economy workplaces comprising waste collection and recycling in India, sewage cleaning in Pakistan, home-based manufacturing in Nepal, small-scale construction in Nepal, and cotton farming in India were studied. The common steps taken in the training were collaboration with local trade unions and employer organizations to reach informal economy workplaces, collection of local good practices in OSH for designing participatory training contents, training worker and employer OSH trainers, assisting trained worker and employer trainers in conducting cascading training activities in their own workplaces, and follow-up visits for support and sustainability. It was found that working with local trade unions and employer organizations had the strong potential to reach various informal economy workplaces. Applying the easy-to-apply participatory training methodologies was vital in delivering practical OSH support.

Keywords: Employer organizations, Informal economy workplaces, Participatory training, South Asia, Trade unions

1. Introduction

International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates show the high percentage of informal economy workers in the total employment in South Asian countries, namely 89.0% in Bangladesh, 88.2% in India, 94.3% in Nepal, 82.4% in Pakistan, and 70.4% in Sri Lanka. Informality of women workers is higher than men [1]. For example, in Pakistan, 92.1% of employed women are in informal employment in contrast to 79.6% of men. Globally, two billion of the world’s employed population aged 15 and over work informally, representing 61.2% of global employment [1]. The workers in the informal economy contribute to the economy without being recognized. They include home-based workers manufacturing textile, metal, and other products, workers working in small, unregistered construction sites, workers engaged in waste collection and recycling work, pedicab and rikisha drivers, farmers, and others. The workers in the informal economy are usually outside the scope of existing occupational safety and health (OSH) legislation and seldom receive adequate OSH inspection and protection [2]. The countries in South Asia need practical measures to improve the safety and health in informal economy workplaces.

Before 2022, ILO’s fundamental principles and rights at work had covered four categories; (1) freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining, (2) the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor, (3) the effective abolition of child labor, and (4) the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation. In 2022, ILO included “a safe and healthy working environment” as the fifth category of its framework of fundamental principles and rights at work [3]. Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 1981 (No. 155) and Promotional Framework for Occupational Safety and Health Convention, 2006 (No. 187) were newly added to ILO’s fundamental conventions. All ILO member states, irrespective of the ratification of these conventions, have an obligation to respect, promote, and realize the principles they set out. Increasing efforts are needed to create safe, healthy, and decent workplaces for all workers including informal economy workplaces. The ILO defines the term “informal economy” as all economic activities by workers and economic units that are—in law or in practice—not covered or insufficiently covered by formal arrangements [4].

Innovative measures and actions have been taken for reaching informal economy workplaces to provide quality, safety, and health services. It has been known that the existing labor administration framework alone is difficult to cover them since informal economy workplaces are often outside their mandate [5]. As an alternative functioning way, Basic Occupational Health Services (BOHSs) approach used the network of district health centers and primary care units under the Ministry of Health and significantly expanded their occupational health service coverage [6]. In Thailand, for example, the primary care unit staff were retrained and attached with essential occupational health service skills. They visited informal economy workplaces including home-based manufacturing and provided practical advisory services for improving occupational health [7,8]. Another practical approach to extend OSH services to unreached workplaces was developed with the trade union initiative in Pakistan. The trade union OSH trainers convinced their employers and extended practical OSH support to many workers and their workplaces using a participatory training methodology [9]. These trade union approaches in cooperation with employers reached informal economy workplaces and provided practical OSH support [10].

ILO style participatory training methodologies are gaining momentum as a practical way to assist employers and workers in improving safety and health and increasingly applied in many countries [[11], [12], [13]]. The ILO participatory training directly involves workers using action checklists and other standard tools to identify OSH areas needing improvements and managing hazards and risks through the walk-through observation of a workplace. Collaboration of employer and workers are promoted for collaborative action and setting timelines of implementation of improvements. OSH workshops using the ILO style participatory training methodologies commonly start with workplace visits with the action checklist application. Participating employers and workers first identify the good examples in OSH of their workplaces and the points to be improved. The subsequent group work among the participants facilitates exchanging their findings and views for making joint improvement proposals. The participatory training covers essential technical areas in OSH including materials’ handling, workstation designs, machine safety, physical environment, and welfare facilities. ILO's WISE (Work Improvements in Small Enterprises) training methodology provides a typical example [14]. Inspired by WISE, the participatory methodologies were widely applied to farmers [15], home-based workers [16], workers in small construction sites [17], and waste collection and recycling workers [18].

The present study examined the recent ILO experiences of improving OSH of informal economy workplaces in South Asia. Participatory training methodologies as the practical support measure to improve OSH were examined. Special attention was paid to the roles of trade unions, employer organizations, and farmer associations for reaching various informal economy workplaces.

2. Methods

ILO developmental cooperation activities of improving safety and health in informal economy workplaces in South Asia from 2017 to 2023 were reviewed. From the review, five participatory OSH training activities directly with workers, employers, and farmers were selected for analysis. They were waste collection and recycling in India, sewage cleaning in Pakistan, home-based manufacturing in Nepal, small-scale construction in Nepal, and cotton farming in India. There were two selection criteria. The first was if the activities collaborated directly with the trade unions, employer organizations, and the farmer associations. The second was if the participatory training methodologies were applied. The author had been the main trainer in the five training activities.

The training contents and tools used in the selected training activities were studied from the viewpoints of promoting active participation of workers and employers. Examined were the application of the participatory training tools and approaches such as action checklists, good practice approaches relying on locally achieved OSH examples [19], low-cost improvement measures, and group work methods that can promote worker and employer participation. In addition, described were the roles of the networks of trade unions, employer organizations, and farmer associations in order to reach informal economy workplaces and organize their workers and farmers. Farmer associations unionized local farmers and were different from trade unions and employer organizations.

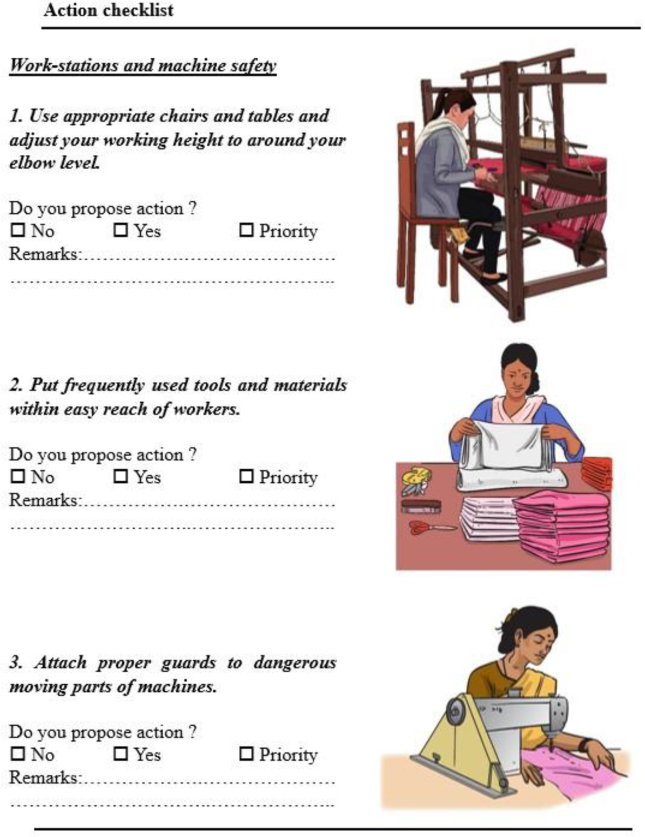

The action checklist covers multiple aspects of practical OSH improvements and consists of about 20 to 40 check items [20]. It uses action sentences together with good example pictures to help participants to develop their own ideas for improvement (photo 1). The definition of low-cost improvements is pragmatic rather than a specific amount of money [21]. There were two selection criteria in the context of South Asia. First, actual financial outlay should be within the day-to-day possibilities of most workplaces, including smaller enterprises. Second, the materials and labor required should be easily available, wherever possible within the workplace itself.

The characteristics of the selected five case studies were as follows.

2.1. Case 1. Waste collection and recycling workers in India

Building an efficient and sustainable waste collection and recycling system is a major public concern in India. In Ahmedabad in Gujarat state, informal waste collection and recycling workers had been progressively unionized. The safety and health of workers was recognized as an important trade union issue. The municipal government of Ahmedabad established a recyclable waste sorting workshop and outsourced its operation to a trade union cooperative. The waste collection and recycling worker union proposed to develop worker safety and health trainers. In response, the ILO assisted conducting a trainer-of-training (TOT) course applying ILO’s Work Adjustment for Recycling and Managing Waste (WARM) training program [18].

2.2. Case 2. Sewage cleaning workers in Pakistan

In the sewage cleaning work in Lahore City, Pakistan, workers had to enter the sewers for manually taking out the sewage. Many were informal workers who worked on a daily wage without receiving safety and health training and necessary protective equipment. Work-related accidents such as falls, cuts, and bruises occurred. Pieces of broken glass and sharp metal were often thrown into the sewage and they were the cause of cut injuries. Toxic gases, such as methane, were accumulated in the sewage and caused fatal accidents. There was the risk of skin and eye infections due to the sewage splash.

2.3. Case 3. Home-based manufacturing workers in Nepal

Many people worked as home-based workers in Kathmandu, the capital of Nepal. They manufacture, for example foods, clothes, jewelry rings and necklaces, metal statues, and Tibetan-style paintings called Thangka. Women from the neighborhood gathered in common workshops to sew woolen hats and make shoes. They suffered from musculo-skeletal disorders due to awkward working posture and carrying heavy materials. Workers engaged in the gold plating of metal statues used the mercury amalgam and were exposed to mercury vapor. Nepali trade unions and handicraft manufacturing employers were keen to improve safety and health of the home-based workers and proposed an OSHTOT workshop using ILO’s WISH (Work Improvement for Safe Home) program [16]. Nepali trade unions were extending their efforts to unionize the disadvantageous home-based workers in the informal economy. Employer organizations purchased the home-based worker products for trading and had regular business contacts with them. They were also keen to assist home-based workplaces in improving their safety and health.

2.4. Case 4. Workers in small construction sites in Nepal

Many women and men workers in Nepal worked in small-scale construction sites for building houses or two-story buildings with stores on the first floor and residences on the second floor. Women workers were engaged in transporting heavy construction materials such as soil and bricks. Most of the workers at small-scale construction sites were informal.

2.5. Case 5. Cotton farmers in India

Cotton farming was growing in Telangana state, India, and required practical support for improving safety and health. Their cotton plants were around only one meter tall. In the lean farmland, they were even shorter. Farmers plucked cotton flowers by hand one by one. Their safety and health risks included carrying heavy objects, sustained forward bending posture, continuous exposure to strong sun heat, unsafe and overuse of pesticides, cobra and other snake bites, and lack of hygienic drinking water and resting facilities in the farm.

3. Results

3.1. Common steps taken in the five participatory training activities

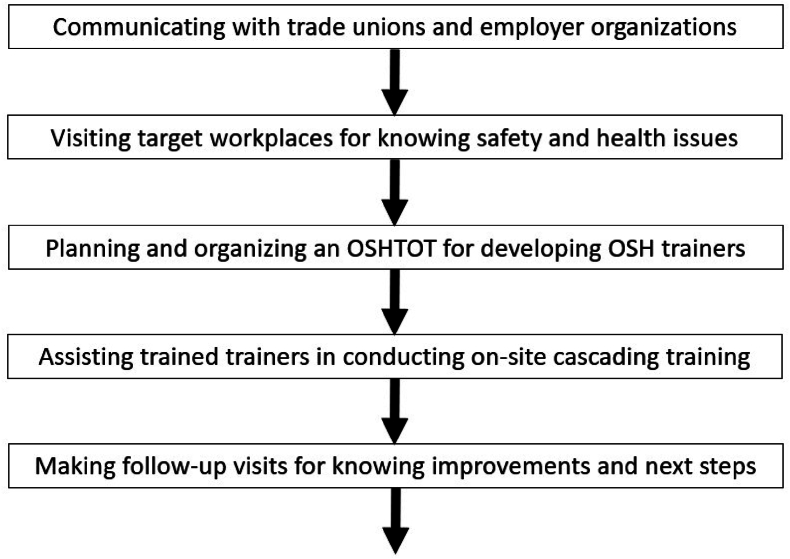

Table 1 shows an outline of the five selected training activities. They commonly took the collaborative steps with trade unions or employer organizations as shown in Fig. 1. The collaborative relationships with local trade unions and employer organizations were inevitable to engage informal economy workplaces for organizing the five participatory training activities. The training of workers and employer trainers was an essential strategy for disseminating the training to neighboring informal economy workers. As shown in Table 2, measures were taken for promoting active participation of informal economy workers in the training and for making the training contents easy-to-understand and practical.

Table 1.

An outline of the five training activities

| Target informal economy workers | Participatory training methodologies used | Collaborative organizations | Reasons for cooperation in OSH |

|---|---|---|---|

|

WARM (Work Adjustment for Recycling and Managing Waste) | Trade unions | Trade unions were concerned with OSH of women waste recycling workers |

|

WARM (Work Adjustment for Recycling and Managing Waste) | Trade unions | Trade unions were concerned with frequent accidents among sewage cleaning workers |

|

WISH (Work Improvement for Safe Home) | Handicraft association Trade unions |

Employer organization and trade unions planned to strengthen their support to home-based workers for promoting OSH and productivity |

|

WISCON (Work Improvement for Small Construction Sites) | Small construction business association | Women employers wanted to prevent accidents of their workers who have no social insurance coverage |

|

WIND (Work Improvement in Neighbourhood Development) | Farmer producer organizations (FPOs) | FPO planned to promote OSH through their established FPRW networks |

FPO, farmer producer organization; FPRW, fundamental principles and rights at work; OSH, occupational safety and health

Fig. 1.

Steps to support informal economy workplaces.

Table 2.

Measures taken to facilitate active involvement of workers in the informal economy workplaces

| Measures | Reasons and benefits |

|---|---|

| Organizing training in workers’ own workplaces | Workers can come to the training center easily |

| Applying shorter training programmes | Workers do not lose their income |

| Training worker and employer trainers | Training activities can be disseminated to neighboring workplaces |

| Learning from local good OSH examples | Workers and employers can know what solutions they can have |

| Applying action checklists with pictures | Workers and employers find good practices and points to be improved in OSH effectively |

| Discussing in small group | Every worker can speak and exchange ideas for improvements |

OSH, occupational safety and health.

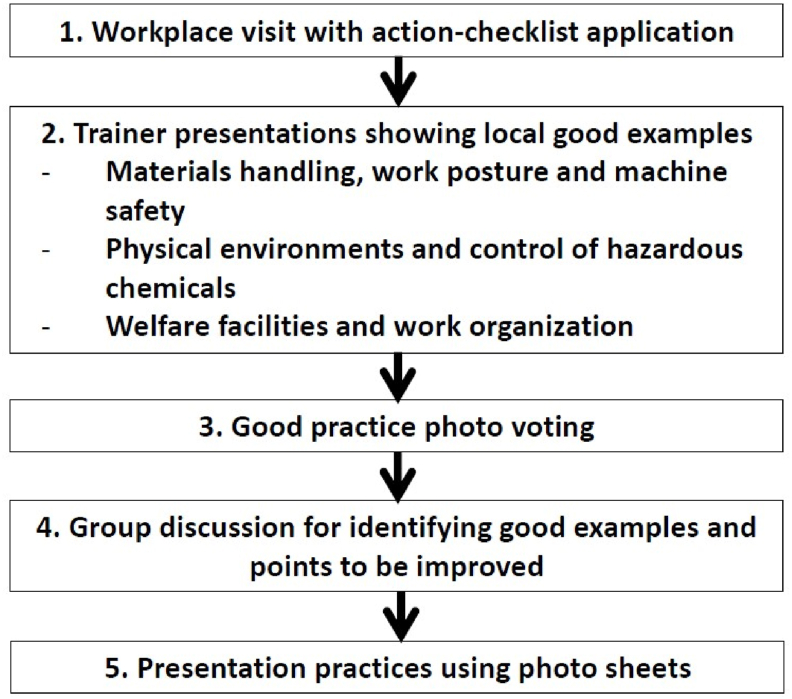

All the five training activities used the same program shown in Fig. 2. The first step was a workplace visit with the application of the action checklist associated with clear-cut good practice illustrations (Photo 1). The workplace visit at the beginning of the training assisted participating workers in assessing the safety and health with their own eyes and experiences. The second step was trainer presentations showing good OSH example pictures in materials handling, work posture, machine safety, physical environments, control of hazardous chemicals, welfare facilities, and work organization. The third step was a good practice photo voting session. The participants overviewed the good practice pictures which the trainers presented and voted for the pictures that were most simple, low-cost, and smart. The fourth step was their group discussions for identifying good examples and points to be improved in OSH in the workplaces that the participants visited in the first step. In the fifth step, the participants learned trainer skills and practiced presentations of OSH good example pictures. The presentation files that the main trainer used were printed on A3 papers as photo-sheets. The participants practiced presentations using them in front of other participants.

Fig. 2.

Program used in the training workshops.

Photo 1.

A sample of WISH action checklist associated with good practice pictures for garment home-based workers. WISH: Work Improvement for Safe Home

3.2. Case 1. Waste collection and recycling workers in India

Thirty workers including 22 women participated in the two-day TOT workshop. Their action checklist exercise (Photo 2) and group discussions identified good examples in OSH such as convenient hand tools for waste collection, sunshades in the segregation area, protective gloves and clothes, waste bins with labels for separate collections, and provision of safe drinking water. Improvements proposed by the participants were carts to move collected waste, safer shoes and goggles for protecting eyes, first-aid kits, hygienic eating places, and toilets separately arranged for women and men.

Photo 2.

Workplace walk-through with the application of the WARM action checklist. WARM, Work Adjustment for Recycling and Managing Waste

The trained trainers started their cascading training activities one month after the TOT (Photo 3). With the photo-sheet method, the trained trainers were able to conduct the training in their workplaces where laptops and projectors were not available. One year later, a trade union trainer reported that they had completed 17 on-site training activities and trained some 1000 workers, mostly women.

Photo 3.

An on-site cascading training workshop for waste recycling workers organized by trained local trainers using photo-sheets.

3.3. Case 2. Sewage cleaning workers in Pakistan

Pakistani trade unions requested ILO support for improving OSH of the sewage workers who were the trade union members. A participatory training workshop was held with both worker and employer representatives. The same structure of the training program shown in Fig. 2 was used by applying a WARM program modified for sewage workers. The participants visited sewage cleaning sites on the road and assessed safety and health risks with the application of the WARM action checklist. Trade union leaders were able to organize the site visit through their collaborative networks. Pump and jetting trucks were on standby for the participants to arrive at the site, and sewage workers demonstrated the ways to open a heavy manhole cover and began the actual sewage cleaning work.

In the group discussions after the site visit, the participants identified an urgent need of facilities of washing workers’ bodies after sewage cleaning work. Workers also needed essential safety measures such as traffic safety barriers while working on the road, gas detectors before entering manholes, and firm footsteps when going down into manholes. Workers and employers jointly proposed updating standard operating procedures for safer and healthier work and training all workers through the trained trainers.

3.4. Case 3. Home-based manufacturing workers in Nepal

Representatives from the government, employers, trade unions, and NGOs who supported home-based workers participated in the TOT workshop. The same structure and contents shown in Fig. 2 were used for the TOT. The trained Nepali trainers organized a cascading training activity for home-based workers. The trainers used the photo-sheet method for showing good practice pictures to their participants. After the initial action checklist (Photo 1) exercise and the trainer presentations, participating home-based workers discussed and identified their improvement ideas. One whole cascading training workshop completed in about 3 hours in the participants’ own home-based workplaces. This short training program was an advantage for easy participation of workers without losing their daily-based income.

After the TOT workshop, workers and employer trainers continued cascading training activities and assisted home-based workers in implementing improvements. The improvements included better lighting by installing skylights and lowering the position of existing electric lights, installation of a ceiling under the tin roof to combat heat, adjusting the height of tables and chairs to improve work posture, attaching cardboard egg containers to the walls to absorb noise, and setting up first-aid kits. The weaving machines were relocated closer to the windows for better lighting and ventilation, and chemical containers were labeled. The handicraft industry association planned to install the new equipment for absorbing mercury vapor in the metal handicraft workplaces.

3.5. Case 4. Workers in small construction sites in Nepal

An employer association of small construction businesses faced occupational accidents of their workers and desired to improve their safety and health. Trade unions had the same concerns. These accidents were outside the scope of the government’s reporting systems. ILO approached the employer associations and trade unions to train their representatives as workplace safety and health trainers. WISCON (Work Improvement for Small Construction Sites) training methodologies were applied [17]. The training contents and structure consisted of the same five steps shown in Fig. 2. In addition to the materials handling, physical environments, welfare facilities sessions, one more technical area of safety of working at heights was added to the WISCON training. Gender equality and making the workplace to meet the needs of women workers were also incorporated in the training.

After the TOT, follow-up visits were organized to some construction sites where the trainers carried out cascading training. A woman employer trainer demonstrated her WISCON training activity on-site using the photo-sheets. The improvements carried out included removal of unnecessary materials from passageways, designated storage areas of construction materials, safe electrical wiring connections, secured ladders, and provision of helmets and shoes for workers. Many women workers requested a safe, clean toilet on their construction sites and the employers agreed to build a toilet facility on site (Photo 4).

Photo 4.

A toilet was built in a small construction site responding to the proposal of women construction workers.

3.6. Case 5. Cotton farmers in India

The networking of the cotton farmers had progressed for promoting ILO’s fundamental principles and rights at work which comprise freedom of association and collective bargaining, elimination of forced labor, abolition of child labor, and elimination of discrimination. Farmers became more unionized, and their collective bargaining power increased for selling the cotton at a better price [22]. The ILO approached to the established farmer networks proposed adding safety and health and organized an OSHTOT course. The participants were twenty farmer representatives from four cotton growing villages in Telangana. A participatory training methodology, WIND (Work Improvement in Neighbourhood Development) designed for agriculture was applied [15]. The training program shown in Fig. 2 was used with the modification for the cotton farming.

The training participants through their group discussions proposed practical safety and health improvements in their cotton farms. Their ideas were the use of wheelbarrows to transport heavy materials, selection of safer seeds as commercially available seeds were often coated with chemicals, safe and designated pesticide storage areas located outside their home, and attaching guards to moving parts of agricultural machinery. One participant demonstrated a method of sowing seeds using cattle for reducing the burden of manual sowing. Female workers proposed clean drinking water, rest facilities, and toilets in the farm.

Follow-up visits one year after the TOT confirmed that the farmer trainers trained 647 neighboring cotton farmers (159 women and 488 men) in 18 villages. The trained farmer trainers started their cascading training one month after the TOT and progressively reached neighboring villages. Trained farmers showed their OSH improvement implementation such as a widened path to the cotton farm for easier transport, use of smaller, lighter sacks for easy carrying of plucked cotton (Photo 5), weeding devices with longer bars to prevent bending posture, or collection of used pesticide packages for safe disposal, and a hut for resting and eating.

Photo 5.

Cotton farmers changed large, heavy sacks (left) to smaller ones (right) for women farmers to carry harvested cotton easily.

4. Discussion

The present study provided important empirical evidence regarding the role of trade unions and employer organizations for delivering practical OSH support to informal economy workplaces that were outside the scope of the government OSH service systems. The trade unions established good contacts to informal economy workplaces for unionizing their workers. The employer organizations had business relationships with informal economy workplaces and purchased their products and services. The five training activities collaborated with these networks of the trade unions, employer organizations, and farmer organizations and were able to organize effective OSH training activities in the targeted informal economy workplaces.

The participatory training methodologies like WISH, WARM, and WIND fit the immediate needs of the informal economy workplace and were able to deliver practical training contents. These participatory training methodologies emphasized that many OSH improvements were possible at low-cost and presented good OSH examples that employers and workers developed using locally available resources [21,23]. The low-cost improvement examples attracted attention of employers and workers for immediate solutions and led them to a series of visible changes. The action checklists associated with good example pictures (Photo 1) assisted the participating workers, employers, and farmers in identifying and proposing practical solutions. Trained trainers benefited from the photo-sheet methods and were able to conduct cascading training activities in the neighboring informal economy workplaces.

The worker and employer trainers and their networks played vital roles in reaching the unreached informal economy workers. The present study confirmed that active collaboration with trade unions, employer organizations, and farmer organizations had the strong potential to extend practical OSH support to informal economy workplaces. In the previous experiences in Cambodia and Thailand, the government took lead and reached informal economy workplaces through their infrastructure [7,24]. The case studies in the present paper added the empirical evidence of the initiatives of trade unions, employer organizations, and farmer organizations to promote OSH in various informal economy workplaces. The worker trainers in waste collection and recycling in Ahmedabad city in India were able to train some 1000 workers in one year through their network. The farmer trainers delivered the training in 18 villages in Telangana state in India and 647 cotton farmers were reached. The participatory training methodologies delivered action-oriented training contents and assisted workers and employers in identifying practical solutions.

It was vital to collect and present good practices in OSH as the inevitable element of the participatory training methodologies. Good practices showed what employers and workers can do for improving OSH using their available resources [19]. Employers and workers in informal economy workplaces were motivated to discuss together practical OSH solutions that can be implemented in their workplaces. It was apparent that trade unions, employer organizations and farmer organizations needed good practice approaches when influencing informal economy workplaces to improve their safety and health.

In conclusion, the present study found that practical OSH training activities reached informal economy workplaces through the collaboration with trade unions, employer organizations, and farmer organizations. The application of the participatory training methodologies provided practical and easy-to-apply solutions. The trained OSH trainers were able to extend the participatory training to neighboring workers and farmers. It is recommended that OSH practitioners and service providers should look at opportunities to work directly with trade unions, employer organizations, and farmer organizations for reaching informal economy workplaces and delivering participatory training support to improve the safety and health.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the ILO.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Tsuyoshi Kawakami: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Conflicts of interest

The author declare no conflicts of interest relating to this paper.

Acknowledgments

This work benefitted from the ILO/Japan Multibilateral Programme support.

References

- 1.ILO . Third edition; 2018. Women and men in the informal economy: a statistical picture. [Google Scholar]

- 2.ILO . 2019. Safety and health at the heart of the future of work: building on 100 years of experience. [Google Scholar]

- 3.ILO . 2023. The fundamental Conventions on occupational safety and health. An overview of the occupational safety and health convention, 1981 (No. 155) and the promotional framework for occupational safety and health convention, 2006 (No. 187) [Google Scholar]

- 4.ILO . 2015. Transition from the informal to the formal economy recommendation, No, 204. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kawakami T. Networking grassroots efforts to improve safety and health in informal economy workplaces in Asia. Ind Health. 2006;44:42–47. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rantanen J., Lehtinen S., Valenti A., Iavicoli S. A global survey on occupational health services in selected international commission on occupational health (ICOH) member countries. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:787. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4800-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siriruttanapruk S., Wada K., Kawakami T. ILO Asia-Pacific working Paper Series. ILO; 2009. Promoting occupational health services for workers in the informal economy through primary care units. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Siriruttanapruk S., Praekunatham H. Integration of basic occupational health services into primary health care in Thailand: current situation and progress. WHO South-East Asia J Pub Health. 2022;11:17–23. doi: 10.4103/WHO-SEAJPH.WHO-SEAJPH_193_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawakami T., Kogi K., Toyama N. Participatory approaches to improving safety and health under trade union initiative; experiences of POSITIVE training program in Asia. Indus Health. 2004;42:196–206. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.42.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Japan International Labour Foundation (JILAF). 15-year POSTIVE experiences: Participation-oriented safety improvements by trade union initiative. JILAF. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kogi K. Roles of participatory action-oriented programs in promoting safety and health at work. Saf Health Work. 2012;3:155–165. doi: 10.5491/SHAW.2012.3.3.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park J.-K., Khai T.-T. Occupational safety and health activities conducted across countries in Asia. Saf Health Work. 2015;6:1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.shaw.2015.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawakami T. Participatory training to improve safety and health in small construction sites in some countries in Asia: Development and application of the WISCON training program. J New Solu. 2016;26:209–210. doi: 10.1177/1048291116652158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ILO . ILO; 2017. Global manual for WISE: work improvements in small enterprises. [Google Scholar]

- 15.ILO . ILO; 2014. Global manual for WIND: practical approaches for improving safety, health and working conditions in agriculture. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawakami T., Arphorn A., Ujita Y. ILO; 2006. WISH (Work Improvement for Safe Home: action manual for improving safety, health and working conditions of home workers) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kawakami T. ILO; 2021. WISCON (Work improvement for small construction sites) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawakami T., Khai T. ILO; 2010. WARM (work adjustment for recycling and managing waste) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kogi K. Advances in participatory occupational health aimed at good practices in small enterprises and the informal sector. Industrial Health. 2006;44:31–34. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.44.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kogi K. Kawakami T. Khai T-T. Design concepts of handy ergonomic checklists for small workplaces. Proceedings of the joint conference of the 4th Asia Pacific Conference on Human Computer Interaction and the 6th South East Asian Ergonomics Society Conference. 298-304.

- 21.Kogi K., Phoon W., Thurman J. ILO; 1988. Low-cost ways of improving working conditions – 100 examples from Asia. [Google Scholar]

- 22.ILO . ILO; 2021. Sustainable cotton farming brings better lives for farmers and their families [Internet] Available from: Our impact, Their voices: Sustainable cotton farming brings better lives for farmers and their families (ilo.org) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kogi K. Facilitating participatory steps for planning and implementing low-cost improvements in small workplaces. Appl Ergono. 2008;39:475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kawakami T., Tong L., Kannitha Y., Sophorn T. Participatory approach to improving safety, health and working conditions in informal economy workplaces in Cambodia. Work. 2011;38:235–240. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2011-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]