Abstract

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) can have a profound impact on patients’ lives. However, multinational data on patients’ lived experience with CKD are scarce.

Methods

Individuals from the prospective cohort of DISCOVER CKD (NCT04034992), an observational cohort study, were recruited to participate in one-to-one telephone interviews to explore their lived experience with CKD. A target of 100 participant interviews was planned across four countries (Japan, Spain, the UK, and the USA). These qualitative interviews, lasting ∼60–90 min, were conducted in the local language by trained interviewers with specific experience in CKD, between January and June 2023. Transcribed interviews were translated into English for coding and analysis. Data were coded using qualitative research software.

Results

Of the 105 participants interviewed, 103 were included in the final analysis. The average time since CKD diagnosis was 9.5 years, and at least half (50.5%) of participants had CKD stage 3A or 3B. CKD diagnosis was an emotional experience, driven by worry (n = 29/103; 28.2%) and shock (n = 26/103; 25.2%), and participants often reported feeling inadequately informed. Additional information was frequently sought, either online or via other healthcare providers. The proportion of participants reporting no impacts of CKD on their lives was highest in those with CKD stage 1 and 2 (64.3%). Conversely, every participant in the CKD stage 5 on dialysis group reported some impact of CKD on their lives. Across all participants, the most reported impacts were anxiety or depression (37.9%) or ability to sleep (37.9%). The frequency of the reported impacts appeared to increase with disease severity, with the highest rates observed in the dialysis group. In that group, the most frequently reported impact was on the ability to work (80.0%).

Conclusion

Findings from this multinational qualitative study suggest that patients may experience symptoms and signs of disease prior to diagnosis; however, these are often nonspecific and may not be directly associated with CKD. Once diagnosed, the burden of CKD can have a diverse, negative impact on various aspects of patients’ lives. This highlights the need for early identification of at-risk individuals, and the importance of early CKD diagnosis and management with guideline-directed therapies to either prevent further deterioration of CKD or slow its progression, thus reducing symptom burden and improving quality of life.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease, Patient experience, Patient insights, Telephone interview, DISCOVER CKD

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a progressive condition affecting over 10% of the general population worldwide [1] and is estimated to become the fifth-leading global cause of death by 2040 [2, 3]. People with CKD face multiple psychosocial adjustment challenges, and experience high symptom burden and reduced health-related quality of life, even in the early stages of the disease when symptoms, including those associated with uremia, are typically less severe or are absent [4–6]. Consequently, CKD is associated with substantial morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs, which negatively impact patients, healthcare systems, and society as a whole [1, 7, 8].

Despite advances in CKD diagnosis, a high proportion of people with CKD remains undiagnosed or is diagnosed late in the evolution of disease, which contributes to poor outcomes [8, 9]. Indeed, it is estimated that just 6% of the general population and 10% of high-risk individuals worldwide are aware of their CKD status [10], and studies have reported levels of undiagnosed CKD as high as 44% in the UK [11] and 62–96% across France, Germany, Italy, Japan, and the USA [12]. Early diagnosis and proactive disease management may slow progression, in turn reducing severity and disease burden, to potentially improve clinical outcomes for people with CKD [9, 13, 14].

Supporting traditional clinical research with experiential patient data is increasingly being recognized among researchers [15–17] and is highly valued by drug regulators [18–20] and payers [21]. Patient-reported insights can help identify previously unrecognized symptoms and highlight the aspects of diseases that most impact patients, thus facilitating earlier diagnosis, development of novel therapies, and encouraging a more tailored approach to care [17]. However, multinational, real-world data regarding the experience of people living with CKD are limited [22].

DISCOVER CKD (NCT04034992) is a multicountry, noninterventional cohort study designed to characterize the epidemiology of CKD and to describe clinical outcomes including disease progression, pharmacological interventions, and important clinical events across the patient journey [22]. The DISCOVER CKD study includes retrospective [23, 24] and prospective cohorts. This qualitative analysis of patient-reported data from the prospective phase of the DISCOVER CKD study describes the lived experience of people with CKD, including perspectives on the diagnosis and management of CKD.

Methods

The DISCOVER CKD study rationale and methodology have been described previously [22]. The study used a hybrid design, comprising retrospective and prospective cohorts. As part of the prospective cohort, people with CKD were recruited to participate in a qualitative sub-study involving one-to-one, semi-structured telephone interviews. The objectives for this qualitative interview study were: to better understand the patient journey, including the settings in which they receive care, and their experience and satisfaction with the care received; to explore the signs, symptoms, and impacts of CKD and establish the most bothersome symptoms and impacts as reported by people living with the condition; and to understand their attitudes toward CKD treatments, as well as expectations for new treatments.

The qualitative interview sub-study followed the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki [22]. No study activities were performed prior to ethics committee approval. All data collection/abstraction was conducted in a method that is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, the Data Protection Act, Independent Review Boards/Ethics Committees, other regulations and participating data custodians’ policies as appropriate for each area in which the study was conducted [22].

Population

Sample Size

Overall, 100 participant interviews were planned across four countries (Japan, Spain, the UK, and the USA) with 20–25 individuals per country. This number of participants was anticipated to achieve information saturation and provide representativeness across countries. Previously, a sample size of 100 has been found to yield acceptable results for this type of study and the sampling method was based on disease stage, presence of type 2 diabetes (T2D), and country of residence in order to capture a wide spectrum of disease severity and health-related quality of life [25, 26]. To reach saturation, it was anticipated that a minimum of 12 participants would be required for each CKD stage (stage 2–5 without dialysis, stage 5 with dialysis) and T2D (with and without).

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Individuals participating in the prospective component of the DISCOVER CKD study were recruited between January and June 2023 to take part in qualitative interviews. The enrollment criteria for the DISCOVER CKD prospective study are reported in detail elsewhere [22]. Briefly, participants had CKD stage 2–5 (with or without dialysis), and the current CKD stage was recorded for the purposes of this analysis. Individuals were excluded if they had a history of significant neurological events (such as a major stroke), or had a medical condition or diagnosis that, in the opinion of the investigator, made them ineligible or unable to participate.

Procedure for the Telephone Interviews

The qualitative interviews (duration, ∼60–90 min) were led by trained interviewers with specific experience in CKD and were conducted in the participants’ local language. Interviews were conducted using a bespoke interview discussion guide, which was developed to support the interviewer by providing questions and probes (see Supplementary Methods; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000541064). All interviews were audio recorded with participants’ consent, and transcripts were used for subsequent data analysis and coding. Each country moderator conducted quality control independently to ensure transcription and translation accuracy. Where translations were needed, moderators carried out quality control on both the local language and the English version of the transcript. Participants were permitted to withdraw from the study at any time. The interview approach followed was consistent with recommended guidelines provided by ISPOR – The Professional Society for Health Economics and Outcomes Research Good Research Practices Task Force [27].

Bothersomeness and Severity Ratings Scale

In this study, separate ratings were sought for symptom bothersomeness and severity to better understand the impact of CKD on participants’ lives; while a symptom or impact may be quite bothersome, it may not have necessarily been considered the most severe symptom or impact experienced. During the interview, following on from the question of “How does CKD currently impact your life?” participants were asked to name their top 3 most bothersome symptoms/impacts. They were then requested to provide a numeric value from 0 to 10 to rate the severity of the symptom/impact on their life, with 0 being “none at all” and 10 being “very severe.” Subsequently, they were asked to rate the bothersomeness of their symptoms/impacts on a scale of 0–10, where 0 was “not at all bothered” and 10 was “greatly bothered.”

Data Analysis

Transcribed interviews were translated into English for coding and analysis. Data were subsequently coded using qualitative research software (MAXQDA Plus 2022 v22.3.0). This facilitated the analysis and classification of patient responses according to their experiences, and the identification of concepts (signs, symptoms, and impacts) that were most important and relevant. The codes were organized within a coding framework established at the beginning of the process and refined and expanded throughout the process.

Four coders were involved in transcript generation, and inter-rater agreement was evaluated between coders for a subset of transcripts to ensure consistency. Of the full transcript set, 20% were randomly selected for double coding by more than one coder. Transcripts were compared using the inter-coder reliability function in the MAXQDA software to highlight potential discrepancies. The coding lead reviewed any discrepancies and evaluated the quality, consistency, and accuracy of the process. Any coding issues were then reconciled internally, ensuring a high level of consistency, accuracy, and reliability between each coder.

No formal statistical analysis was conducted, and descriptive data are presented. Data are presented for the overall population, and according to CKD stage for current experiences of signs, symptoms, and impacts of disease.

Results

Demographics

Overall, 105 participants were interviewed, and 103 participants were included in the final analysis; 2 interviews were unusable due to malfunctions in the audio recording. The mean (standard deviation) age of the study population was 63.1 (10.2) years and 42.7% were female (Table 1). A total of 22.3% of participants had CKD stage 3A, 28.2% had stage 3B, 18.5% had stage 4, and 7.8% had stage 5 without dialysis. The mean (standard deviation) time since CKD diagnosis (n = 102) was 9.5 (6.1) years (range 0–21 years). Overall, 52% of the participants had hypertension (n = 54/103) or T2D (n = 53/103). A total of 13.6% of participants (n = 14/103) had cardiovascular disease.

Table 1.

Participant demographics

| Characteristic | N = 103 | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), years | 63.05 (10.15) | – |

| Sex, female, n | 44 | 42.7 |

| Geographical location, n | ||

| USA | 29 | 28.2 |

| UK | 25 | 24.3 |

| Spain | 25 | 24.3 |

| Japan | 24 | 23.3 |

| Race, n | ||

| White | 70 | 68.0 |

| Asian | 5 | 4.9 |

| Black/African American | 24 | 23.3 |

| Other | 1 | 1.0 |

| Not reported | 3 | 2.9 |

| CKD stage, n | ||

| Stage 1 | 2 | 1.9 |

| Stage 2 | 12 | 11.7 |

| Stage 3A | 23 | 22.3 |

| Stage 3B | 29 | 28.2 |

| Stage 4 | 19 | 18.5 |

| Stage 5 (without dialysis) | 8 | 7.8 |

| Stage 5 (dialysis) | 10 | 9.7 |

| Comorbidities, n | ||

| Hypertension | 54 | 52.4 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 53 | 51.5 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 14 | 13.6 |

| Heart failure | 8 | 7.8 |

CKD, chronic kidney disease; SD, standard deviation.

CKD Diagnosis

CKD diagnosis was often a multidisciplinary effort involving numerous referrals between more than 1 specialist. Participants normally received a referral from their general practitioner to a specialist who helped with the diagnosis following abnormal test results. Most participants reported having a nephrologist (n = 73/103; 70.9%) or a general practitioner (n = 48/103; 46.6%) involved in their diagnosis, and 10.7% (n = 11/103) and 5.8% (n = 6/103) reported a cardiologist or endocrinologist being involved, respectively. Of the participants who recalled how long it took to receive a diagnosis, 16 stated that they received their diagnosis within 1 year of seeking healthcare and 2 recalled receiving their diagnosis within 1–3 years of seeking care.

Signs and Symptoms Experienced prior to CKD Diagnosis

Of 103 participants, 40 (38.8%) did not recall experiencing signs or symptoms prior to CKD diagnosis. Overall, 61.2% of participants experienced a specific sign/symptom around the time of diagnosis, most commonly fatigue (n = 22/103; 21.4%), high blood pressure (n = 16/103; 15.5%), and swelling (n = 12/103; 11.7%) (online suppl. Fig. 1). Many participants did not realize that the signs and symptoms experienced could be related to their CKD.

Emotional Experiences at CKD Diagnosis

CKD diagnosis was an emotional experience for participants; the most observed feelings included worry (n = 29/103; 28.2%) and shock (n = 26/103; 25.2%); 27.2% (n = 28/103) reported no reaction (online suppl. Fig. 2). Participants explained that the predominant feeling of worry was driven by uncertainty of the prognosis or disease worsening, such as “…I was really scared. I said, are you going to be able to save my kidney?” (online suppl. Table 1). The feeling of shock/surprise resulted from receiving an unexpected diagnosis following clinical investigations for an unrelated reason, or a routine or unrelated blood test, rather than the participant presenting to their healthcare provider with symptoms of CKD. For example, one participant said: “It seemed to be plucked out of the air” (online suppl. Table 1). Participants with T2D less commonly reported feelings of shock, as many were aware of their risk of developing CKD. Other emotions reported at diagnosis were sadness (n = 7/103; 6.8%), anger (n = 4/103; 3.9%), and feeling upset (n = 3/103; 2.9%). Patients felt that they were not informed of their diagnosis in a timely manner, and the idea that their healthcare provider may have missed something that should have been obvious. Delayed diagnoses also led to feelings of anger from some participants, such as “…I was kind of upset…I think I could have been told more earlier” (online suppl. Table 1).

Information Provided at Initial CKD Diagnosis

At initial diagnosis, participants struggled to understand the information provided and often left the appointment feeling inadequately informed (n = 32/58; 55.2%). The main reported information gaps were: not enough explanation of the diagnosis (n = 21/75; 28.0%), lack of information (n = 20/75; 26.7%), and feeling that their questions had not been addressed (n = 8/75; 10.7%). A total of 59.2% of participants (n = 45/76) were either not told or could not recall their CKD stage at the time of diagnosis. Of those who were told, 12.9% (n = 4/31) were diagnosed at stage 4/5, and 25.8% (n = 8/31) and 32.3% (n = 10/31) at stages 3A and 3B, respectively.

Information and Support following CKD Diagnosis

After diagnosis, some participants sought more information, such as “[I] searched online and read a variety of things” (online suppl. Table 1). The internet was the most common source of additional information (n = 36/68; 52.9%), followed by other healthcare professionals (n = 13/68; 19.1%), books and printed information (n = 8/68; 11.8%), patient support groups (n = 6/68; 8.8%), and family and friends (n = 2/68; 2.9%). Spanish participants had the greatest number of requests for additional support (n = 18/52; 34.6%), while US participants had the fewest (n = 7/52; 13.5%). When asked what additional support would help manage their CKD, help from a dietician was the most commonly mentioned overall (n = 10/52; 19.2%). Those who met with a dietician or nutritionist described appreciating this support and subsequently felt more confident in making choices around diet. General practitioners were the most cited source of advice around lifestyle changes, although family members were also mentioned. Other than this, participants wanted more time with CKD specialists and access to resources such as lifestyle coaches and other forms of patient support.

Experience of Living with CKD

Current Symptoms of CKD

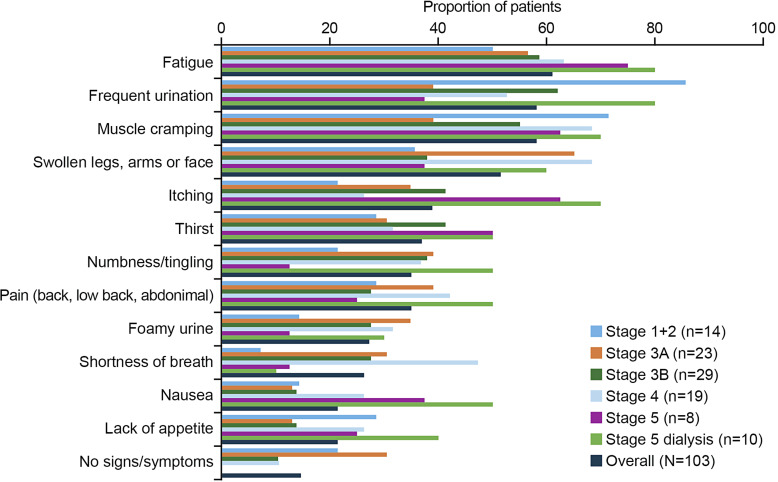

Overall, fatigue (n = 63/103; 61.2%), frequent urination (n = 60/103; 58.3%), and muscle cramping (n = 60/103; 58.3%) were the most frequently reported symptoms (Fig. 1), such as “I become fatigued easily” and “I can urinate more times than normal.” Notable quotes from participants are described in online supplementary Table 1. The symptoms most commonly reported by those earlier in their disease journey (CKD stage 1 + 2) were frequent urination (n = 12/14; 85.7%) and muscle cramping (n = 10/14; 71.4%) (Fig. 1). The burden of symptoms was highest in those with advanced disease; the most frequently reported symptoms for participants with CKD stage 5 on dialysis were fatigue (n = 8/10; 80.0%), frequent urination (n = 8/10; 80.0%), muscle cramping (n = 7/10; 70.0%), swollen legs/arms/face (n = 6/10; 60.0%), and itching (n = 7/10; 70.0%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Current symptoms of CKD according to CKD stage (>10% of participants; N = 103). CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Impact of CKD on Patients’ Lives

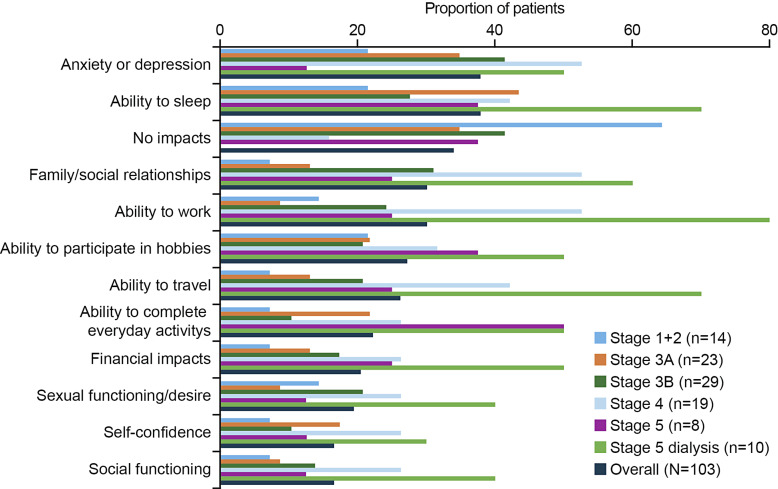

Overall, 35/103 (34.0%) interviewees reported no impact of CKD on their life, either because they felt unaffected by their condition or were unclear about how it could impact their lives. No impacts were most commonly reported in participants with CKD stage 1 + 2 (n = 9/14; 64.3%). A summary of the reported impacts of CKD overall and according to CKD stage are presented in Figure 2. In the overall group, the most observed impact was on mental wellbeing, with anxiety or depression reported by 37.9% (n = 39/103) of participants overall. In most cases, anxiety and depression were attributed to worry about disease progression and death, such as “The worry about dying” (online suppl. Table 1). The second most reported impact overall was on the ability to sleep (n = 39/103; 37.9%), normally described as difficulty staying asleep, either due to muscle cramps or frequent urination. Thirty-one (30.1%) participants reported that CKD had an impact on their ability to work, with them needing to take time off work, undertake adjusted duties, or retire earlier than planned, for example, “I was able to return to work, but I experienced fatigue and various symptoms” (online suppl. Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Impact of CKD on participants lives according to CKD stage (>10% of participants; N = 103). CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Considering subgroups of CKD stages, the frequency of the reported impacts appeared to increase with disease severity, with the highest rates generally observed in the CKD stage 5 on dialysis group (Fig. 2). In this group, the most common impact was on the ability to work, affecting 80% of patients (n = 8/10). The impact of disease on the ability to complete everyday activities was highest in the group with CKD stage 5, both with and without dialysis, affecting 50% of patients in each group (n = 5/10 and n = 4/8, respectively).

CKD impacts, severity, and bothersomeness ratings are presented in Table 2. Financial impacts due to CKD or its management were indicated as the most severe and having the most bothersome impact. The top 5 rated (from 0 to 10) most bothersome impacts were financial impacts (9.00; n = 4/103), social functioning (8.80; n = 5/103), sexual functioning (8.57; n = 7/103), ability to work (8.43; n = 7/103), and ability to sleep (8.42; n = 12/103).

Table 2.

Impacts severity and bothersomeness rating

| Impacts | Severity rating (0–10)a (n) | Bothersomeness rating (0–10)b (n) |

|---|---|---|

| Financial impacts | 10.0 (2) | 9.0 (4) |

| Social functioning | 9.0 (4) | 8.8 (5) |

| Ability to work | 8.7 (7) | 8.4 (7) |

| Sexual functioning | 7.5 (2) | 8.6 (7) |

| Ability to complete everyday activities | 7.4 (5) | 8.0 (6) |

| Ability to travel | 7.2 (6) | 7.3 (8) |

| Ability to sleep | 6.9 (11) | 8.4 (12) |

| Ability to participate in hobbies | 6.8 (4) | 6.6 (5) |

| Family/social relationships | 6.0 (5) | 8.2 (6) |

| Anxiety/depression | 5.1 (9) | 6.1 (11) |

aPatients provided a numerical value to rate the severity of the top 3 most bothersome symptoms/impacts on their life, with 0 being “none at all” and 10 being “very severe.”

bFollowing this, they were asked to provide a numeric value from 0 to 10 to rate the bothersomeness of the symptom/impact, where 0 was “not at all bothered” and 10 was “greatly bothered.”

Treatment Experience of Patients with CKD

Across countries, treatment for underlying complications was the most common approach initially discussed. Overall, 38/57 (66.7%) participants set treatment goals with their healthcare provider, such as staying off dialysis for as long as possible (“…I don’t want to go on dialysis”; online suppl. Table 1), treatment of the underlying cause of CKD (e.g., blood sugar control in participants with diabetes), blood pressure control, and dietary management. At a country level, Japanese participants reported the highest proportion of goal setting (n = 17/21; 81.0%).

Most participants perceived that they were not currently receiving a specific medical treatment to manage their CKD. Treatment for CKD complications was the most discussed (n = 52/111 responses; 46.9%), including interventions such as dialysis, and treatment for anemia, hyperkalemia, and fluid overload, as well as vitamin/mineral supplementation.

Of 70 individuals who reported discussing treatments for their CKD, most (n = 52; 74.3%) stated that they understood the purpose of the treatment. Overall, 39/66 (59.1%) expressed a greater preference for oral medication, followed by lifestyle changes (n = 21/66; 31.8%). Such changes, as recommended by healthcare professionals, included increased physical activity (n = 69/103; 67.0%) and dietary changes (n = 76/103; 73.8%) to limit salt and potassium consumption. Those with more advanced stages of CKD were also advised to limit protein intake. Overall, 96.1% of participants reported attempting to make lifestyle changes; however, difficulties were noted regarding being consistent with dietary changes and increasing physical activity, often due to the impact of other health conditions. Starting dialysis was a key worry for participants. Ten participants were on dialysis at the time of the study, and this was the most commonly discussed treatment specifically for CKD (n = 29/52; 55.8%). In terms of accessing care, the main challenges reported were related to care management (n = 22/42; 52.4%) and long waiting lists to see healthcare providers (n = 11/42; 26.2%).

Patient Confidence with CKD Management

Patient confidence with CKD management tended to improve with disease experience (see online suppl. material: Patient Confidence with CKD Management).

Discussion

The DISCOVER CKD study includes retrospective [23, 24] and prospective cohorts. In this qualitative sub-study of the prospective cohort, patient insights collected through one-to-one interviews were designed to complement clinical and patient-reported outcome data gathered as part of the DISCOVER CKD study, increasing understanding of patients’ perspectives and experiences of CKD [22]. Evidence suggests that awareness of CKD is low compared with other chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension [28], which is a major contributor to the global rise in prevalence [3]. Despite the range of symptoms experienced, CKD is often under-recognized and under-treated [29, 30]. CKD-associated symptoms are typically nonspecific, difficult to quantify, and challenging to differentiate [30]. In our study, a pattern of low symptom awareness was observed, and a CKD diagnosis, often made following laboratory tests for other conditions, was a shock for participants. While efforts aimed at the early detection and treatment of CKD among high-risk individuals are strongly recommended in clinical guidelines [10], our findings also suggest a significant gap in implementing guideline-directed medical therapy. Improving patient and family/carer education about the risks of CKD may also help alleviate some of the diagnosis-related anxiety and shock.

The importance of patient insight as a component of integrated care is recognized in other diseases such as cardiovascular disease [31, 32], diabetes [33], and rheumatological disorders [34]. Awareness of the patient experience [17], and shared patient–healthcare provider decision-making are growing in recognition as components of CKD management [30]. In our study, the process of diagnosis was reported as overwhelming and confusing, with over half of participants experiencing dissatisfaction with the explanation received and, subsequently, additional information was sought. Patient education offers the potential for a collaborative approach to disease management, enabling improved self-management and prognosis [10, 14]; our findings highlight a need for healthcare providers to have access to additional resources to help support people with CKD. Offerings such as pamphlets developed based on patient insights and in patient-friendly language could help individuals through the disease process, including how to have conversations with their healthcare providers, as well as signposting to simple-to-navigate websites. Furthermore, tailored education should be made available for healthcare professionals to use in their practice, based on the spectrum of patients encountered, in a format that factors in age-related preferences for written or audiovisual materials, and different levels of patient literacy. Follow-up appointments after diagnosis could offer patients an opportunity to ask questions and enable healthcare providers a further opportunity to direct patients to trusted sources of support information. In addition, initiation of renal rehabilitation programs, which provide multifaceted lifestyle guidance including dietary management and psychosocial care for improvement of health status, in addition to exercise therapy, may be warranted [35]. Further research is recommended to discern the ideal modality and content of optimized educational approaches.

The burden of CKD can negatively impact various aspects of the lives of those with the condition as well as their families/carers, due to the combination of symptoms, lifestyle changes, and medical care that are often required to manage CKD [30, 36, 37]. In our study, psychological impacts such as anxiety and depression, and sleep disturbance were the most reported impacts, consistent with previous observations [30]. Additionally, fear of dialysis was identified as a key worry for participants. Symptoms and impacts of disease become more evident with progressing disease severity. A key finding is that financial impacts and ability to work were bothersome impacts. This aligns with previous reports of people with CKD experiencing difficulties with work (often requiring adjustment of work or partial work disability) and financial hardship due to lost working days [38–40]. However, it is encouraging that many participants were motivated to make these changes and stated that their confidence in managing their disease improved over time.

Strengths of this qualitative interview study include the geographical and clinical diversity of the participants. Indeed, the overall prospective DISCOVER CKD cohort is representative of multiple races, geographical locations and clinical backgrounds, and participant characteristics are similar to other published CKD cohorts [41–46]. In addition, interviews were conducted by experienced moderators and analyzed using a combination of inductive and deductive methods to maximize the influence of the patient voice in the results. Overall, a notable number of participants (N = 103) took part in the interviews. However, it is acknowledged as a limitation that participant numbers were small in some of the subgroups, due to incomplete data. Furthermore, due to the length of the interview guide, not all questions could be asked of all participants in the given timeframe. Therefore, responses to some questions were not based on the entire interview sample. Smaller numbers in some subgroups of participants mean that concept saturation may not have been achieved for some topics. Other limitations include the low ethnic diversity of the sample, with mostly White participants, despite documented prevalence of CKD in Black/African American populations in the UK and USA Additionally, the Asian patients were all from Japan, and so findings cannot be generalized to other Asian populations. Also, the mean time since CKD diagnosis was approximately 9.5 years. This may have introduced recall bias and should be considered when interpreting the results. Future research may involve the use of tailored surveys to obtain quantifiable data related to the care journey, treatments, and the utilization of different types of educational information, as well as exploring the lived experiences of patients who have received a kidney transplant.

In conclusion, findings from this large multinational CKD cohort qualitative study suggest that most patients experience symptoms and signs of disease prior to diagnosis; however, these are often non-specific and challenging to directly associate with CKD. Hence, there is a need for patient education regarding the diagnosis process for CKD, and proactive screening for early identification of at-risk individuals and the timely implementation of guideline-directed pharmacotherapy to either prevent CKD occurrence or slow its progression. Educating, supporting, and active monitoring of individuals diagnosed with CKD are needed to motivate lifestyle changes and adherence to guideline-directed treatment. Participants reported diverse impacts of CKD, which suggests that measures to minimize such impacts should be multifaceted with consideration of broad aspects that include the psychological, social, and financial burden.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who participated in the study. Medical writing support was provided by Louise Brady, PhD, and Shaun Foley, BSc (Hons), both of Core (a division of Prime, London, UK), according to Good Publication Practice guidelines (https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/full/10.7326/M22-1460).

Statement of Ethics

This study was performed in accordance with ethical principles consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki, International Conference on Harmonization, Good Clinical Practice, and the applicable legislation on noninterventional studies and observational studies. The study received Institutional Review Board ethics approval across the different countries and sites (central approval: UK: REC No. 19/YH/0357; Spain: 2021/342; and USA: Pro00036594; and local approval: Japan). A full list of study sites and their respective ethics committees is provided in online supplementary Table 2. All interviewed participants provided written informed consent.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Carol Pollock reports advisory board membership for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Vifor Pharma; and speaker fees for AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, Otsuka, and Vifor Pharma. Juan-Jesus Carrero reports institutional grants from Astellas, AstraZeneca, and Vifor Pharma; speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Abbott, and Nutricia; and consultancy for AstraZeneca and Bayer. Eiichiro Kanda is a consultant for AstraZeneca. Richard Ofori-Aseno, Surendra Pentakota, Juan Jose Garcia Sanchez, Ewelina Palmer, and Anna Niklasson are employees of, and hold or may hold stock in, AstraZeneca. Andrew Linder and Helen Woodward report no conflict of interest. Naoki Kashihara is a consultant for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Kyowa Hakko Kirin; and receives honoraria from Kyowa Hakko Kirin and Daiichi Sankyo. Steven Fishbane reports research support and consulting fees from AstraZeneca; and research support from Akebia Inc., MegaPro Biomedical Co., Ltd., Ardelyx, Corvidia Therapeutics, Inc., and Cara Therapeutics. Robert Pecoits-Filho is an employee of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, which receives global support for the ongoing Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study Programs (provided without restriction on publications by a variety of funders; for details see https://www.dopps.org/AboutUs/Support.aspx). Robert Pecoits-Filho also reports research grants from Fresenius Medical Care; nonfinancial support from Akebia, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Novo Nordisk, and FibroGen; personal fees from Travere Therapeutics; and consulting fees from George Clinical outside the submitted work. David C. Wheeler reports personal fees and nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca; and personal fees from Astellas, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Janssen, Mundipharma, Napp, Reata Pharmaceuticals, Tricida, and Vifor Fresenius.

Funding Sources

This analysis was funded by AstraZeneca. Medical writing support was funded by AstraZeneca.

Author Contributions

C.P., E.K., R.O-A., E.P., A.N., S.P., J.J.G.S., N.K., S.F., R.P-F., D.C.W., and J-J.C.: study design, data analysis, data interpretation, and drafting and reviewing the manuscript. A.L. and H.W.: data analysis, data interpretation, and drafting and reviewing the manuscript. The sponsor was involved in the study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. However, ultimate responsibility for opinions, conclusions, and data interpretation lies with the authors.

Funding Statement

This analysis was funded by AstraZeneca. Medical writing support was funded by AstraZeneca.

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be requested in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure. AstraZeneca Group of Companies allows researchers to submit a request to access anonymized patient level clinical data, aggregate clinical or genomics data (when available), and anonymized clinical study reports through the Vivli web-based data request platform.

Supplementary Material.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl. 2011;12(1):7–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Foreman KJ, Marquez N, Dolgert A, Fukutaki K, Fullman N, McGaughey M, et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet. 2018;392(10159):2052–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carriazo S, Villalvazo P, Ortiz A. More on the invisibility of chronic kidney disease… and counting. Clin Kidney J. 2022;15(3):388–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cruz MC, Andrade C, Urrutia M, Draibe S, Nogueira-Martins LA, Sesso CC. Quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinics. 2011;66(6):991–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brown SA, Tyrer FC, Clarke AL, Lloyd-Davies LH, Stein AG, Tarrant C, et al. Symptom burden in patients with chronic kidney disease not requiring renal replacement therapy. Clin Kidney J. 2017;10(6):788–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hansen MS, Tesfaye W, Sud K, Sewlal B, Mehta B, Kairaitis L, et al. Psychosocial factors in patients with kidney failure and role for social worker: a secondary data audit. J Ren Care. 2023;49(2):75–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration . Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2020;395(10225):709–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sundstrom J, Bodegard J, Bollmann A, Vervloet MG, Mark PB, Karasik A, et al. Prevalence, outcomes, and cost of chronic kidney disease in a contemporary population of 2·4 million patients from 11 countries: the CaReMe CKD study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;20:100438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tangri N, Peach E, Franzen S, Barone S, Kushner P. Patient management and clinical outcomes associated with a recorded diagnosis of stage 3 chronic kidney disease: the REVEAL-CKD study. Adv Ther. 2023;40(6):2869–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes KDIGO CKD Work Group . KDIGO 2024 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2024;105(4s):S117–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hirst JA, Hill N, O'Callaghan CA, Lasserson D, McManus RJ, Ogburn E, et al. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the community using data from OxRen: a UK population-based cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2020;70(693):e285–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tangri N, Moriyama T, Schneider MP, Virgitti JB, De Nicola L, Arnold M, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed stage 3 chronic kidney disease in France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the USA: results from the multinational observational REVEAL-CKD study. BMJ Open. 2023;13(5):e067386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Levin A, Rigatto C, Brendan B, Madore F, Muirhead N, Holmes D, et al. Cohort profile: Canadian study of prediction of death, dialysis and interim cardiovascular events (CanPREDDICT). BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, Grams ME, Ix JH, Jha V, et al. The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int. 2021;99(1):34–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Anderson A, Benger J, Getz K. Using patient advisory boards to solicit input into clinical trial design and execution. Clin Ther. 2019;41(8):1408–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Oben P. Understanding the patient experience: a conceptual framework. J Patient Exp. 2020;7(6):906–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ryden A, Nolan S, Maher J, Meyers O, Kundig A, Bjursell M. Understanding the patient experience of chronic kidney disease stages 2-3b: a qualitative interview study with Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL-36) debrief. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services FaDA . Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product developmet to support labeling claims; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. U.S. Food and Drug Administration . 21st century cures Act; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 20. European Medicines Agency . Patient experience data in EU medicines development and regulatory decision-making; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zagadailov E, Fine M, Shields A. Patient-reported outcomes are changing the landscape in oncology care: challenges and opportunities for payers. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2013;6(5):264–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pecoits-Filho R, James G, Carrero JJ, Wittbrodt E, Fishbane S, Sultan AA, et al. Methods and rationale of the DISCOVER CKD global observational study. Clin Kidney J. 2021;14(6):1570–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. James G, Garcia Sanchez JJ, Carrero JJ, Kumar S, Pecoits-Filho R, Heerspink HJL, et al. Low adherence to kidney disease: improving global outcomes 2012 CKD clinical practice guidelines despite clear evidence of utility. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7(9):2059–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pollock C, James G, Garcia Sanchez JJ, Arnold M, Carrero JJ, Lam CSP, et al. Cost of end-of-life inpatient encounters in patients with chronic kidney disease in the United States: a report from the DISCOVER CKD retrospective cohort. Adv Ther. 2022;39(3):1432–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2nd ed.SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Creswell JW Qualitative inquiry and research design: choosing among five approaches. 2nd ed.SAGE Publications, Inc.; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, Leidy NK, Martin ML, Molsen E, et al. Content validity: establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1 – eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14(8):967–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tuot DS, Zhu Y, Velasquez A, Espinoza J, Mendez CD, Banerjee T, et al. Variation in patients' awareness of CKD according to how they are asked. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11(9):1566–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gelfand SL, Scherer JS, Koncicki HM. Kidney supportive care: Core curriculum 2020. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(5):793–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kalantar-Zadeh K, Lockwood MB, Rhee CM, Tantisattamo E, Andreoli S, Balducci A, et al. Patient-centred approaches for the management of unpleasant symptoms in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2022;18(3):185–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Vrablik M, Catapano AL, Wiklund O, Qian Y, Rane P, Grove A, et al. Understanding the patient perception of statin experience: a qualitative study. Adv Ther. 2019;36(10):2723–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ski CF, Cartledge S, Foldager D, Thompson DR, Fredericks S, Ekman I, et al. Integrated care in cardiovascular disease: a statement of the association of cardiovascular nursing and allied professions of the European society of cardiology. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2023;22(5):e39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ndjaboue R, Chipenda Dansokho S, Boudreault B, Tremblay MC, Dogba MJ, Price R, et al. Patients' perspectives on how to improve diabetes care and self-management: qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(4):e032762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bryant MJ, Munt R, Black RJ, Reynolds A, Hill CL. Joining forces to understand what matters most: qualitative insights into the patient experience of outpatient rheumatology care. Rheumatol Adv Pract. 2023;7(3):rkad068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kohzuki M. Renal rehabilitation: present and future perspectives. J Clin Med. 2024;13(2):552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Evans M, Lewis RD, Morgan AR, Whyte MB, Hanif W, Bain SC, et al. A narrative review of chronic kidney disease in clinical practice: current challenges and future perspectives. Adv Ther. 2022;39(1):33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fletcher BR, Damery S, Aiyegbusi OL, Anderson N, Calvert M, Cockwell P, et al. Symptom burden and health-related quality of life in chronic kidney disease: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2022;19(4):e1003954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Essue BM, Wong G, Chapman J, Li Q, Jan S. How are patients managing with the costs of care for chronic kidney disease in Australia? A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2013 2013/01/10;14(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Morton RL, Schlackow I, Gray A, Emberson J, Herrington W, Staplin N, et al. Impact of CKD on household income. Kidney Int Rep. 2018 2018/05/01/;3(3):610–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Alma MA, van der Mei SF, Brouwer S, Hilbrands LB, van der Boog PJM, Uiterwijk H, et al. Sustained employment, work disability and work functioning in CKD patients: a cross-sectional survey study. J Nephrol. 2023;36(3):731–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Martinez-Castelao A, Gorriz JL, Portoles JM, De Alvaro F, Cases A, Luno J, et al. Baseline characteristics of patients with chronic kidney disease stage 3 and stage 4 in Spain: the MERENA observational cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2011;12:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Denker M, Boyle S, Anderson AH, Appel LJ, Chen J, Fink JC, et al. Chronic renal insufficiency cohort study (CRIC): overview and summary of selected findings. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(11):2073–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kang E, Han M, Kim H, Park SK, Lee J, Hyun YY, et al. Baseline general characteristics of the Korean chronic kidney disease: report from the Korean cohort study for outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease (KNOW-CKD). J Korean Med Sci. 2017;32(2):221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yuan J, Zou XR, Han SP, Cheng H, Wang L, Wang JW, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for cardiovascular disease among chronic kidney disease patients: results from the Chinese cohort study of chronic kidney disease (C-STRIDE). BMC Nephrol. 2017;18(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Stengel B, Metzger M, Combe C, Jacquelinet C, Briancon S, Ayav C, et al. Risk profile, quality of life and care of patients with moderate and advanced CKD: the French CKD-REIN cohort study. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2019;34(2):277–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Reichel H, Zee J, Tu C, Young E, Pisoni RL, Stengel B, et al. Chronic kidney disease progression and mortality risk profiles in Germany: results from the chronic kidney disease outcomes and practice patterns study. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2020;35(5):803–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data underlying the findings described in this manuscript may be requested in accordance with AstraZeneca’s data sharing policy described at https://astrazenecagrouptrials.pharmacm.com/ST/Submission/Disclosure. AstraZeneca Group of Companies allows researchers to submit a request to access anonymized patient level clinical data, aggregate clinical or genomics data (when available), and anonymized clinical study reports through the Vivli web-based data request platform.