Abstract

Introduction

Patients with alopecia areata (AA) report high levels of dissatisfaction with commonly used treatments. Patient-reported outcomes are essential to understanding patients’ experiences with AA treatments. The objective of this study was to evaluate patient-reported satisfaction with hair growth among patients with AA receiving ritlecitinib or placebo and the correlation between clinician-assessed efficacy and patient-reported satisfaction.

Methods

In the ALLEGRO-2b/3 (NCT03732807) trial, patients with AA and ≥50% scalp hair loss were randomized to daily ritlecitinib or placebo for 24 weeks, with a 24-week extension of continued ritlecitinib or switch from placebo to ritlecitinib. The Patient Satisfaction with Hair Growth (P-Sat) measure evaluated patients’ satisfaction with hair growth in 3 domains: amount, quality, and overall satisfaction with hair growth. The prespecified analysis evaluated the proportion of patients who were slightly, moderately, or very satisfied with hair growth. Several post hoc analyses assessed the proportion of patients who were moderately/very satisfied and moderately/very dissatisfied and calculated polyserial correlations between change from baseline (CFB) in Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) and P-Sat scores at weeks 24 and 48.

Results

At week 24, the proportion of patients (N = 718) reporting satisfaction (slightly, moderately, or very satisfied) overall with their hair growth ranged from 36.4% in the ritlecitinib 10-mg group (evaluated for dose ranging only) to 67.5% in the 200/50-mg group versus 22.6% in the placebo groups. In patients randomized to ritlecitinib, the proportion who were satisfied increased or was maintained at week 48. A substantially greater proportion of placebo patients who switched to ritlecitinib reported satisfaction at week 48 than at week 24. Similar results were observed for patient satisfaction with the amount and quality of hair growth. In the post hoc analyses defining satisfaction as moderately/very satisfied and dissatisfaction as moderately/very dissatisfied, the benefit of ritlecitinib was also observed. All P-Sat domain scores strongly correlated with CFB-SALT scores at weeks 24 (range 0.73–0.76; p < 0.05) and 48 (0.74–0.77; p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Patients receiving active ritlecitinib doses reported favorable results versus placebo in satisfaction with hair growth up to week 48. High concordance was observed between improvement in scalp hair growth evaluated by clinicians and patient-reported satisfaction.

Keywords: Alopecia areata, Patient-reported outcomes, Ritlecitinib, Satisfaction

Plain Language Summary

Alopecia areata (AA) is a disease which causes small or large areas of hair loss on the scalp and/or body. AA affects about 145 million people worldwide and occurs in children and adults. AA can have a large impact on a person’s mental health and cause damage to self-esteem. AA can also cause worry or feelings of sadness. Therefore, it is important to understand if people are satisfied with their treatments for AA. Our study looked at a medicine called ritlecitinib that was taken as a pill by mouth. People in the study had lost at least half of the hair on their scalp and were at least 12 years old. A total of 718 people in 18 countries were included. The purpose of this study was to compare ritlecitinib with a placebo (medicine that looks the same but does not have active ingredients). It was decided by chance what treatment people would take. We looked at how many people were satisfied with the amount and quality of their hair and how satisfied they were overall with hair growth during the 1-year study. After 6 months, many more people taking ritlecitinib were satisfied with their hair growth than people taking placebo. After people who were taking placebo switched to ritlecitinib, more were satisfied with their hair growth than before switching. The satisfaction that people reported with hair growth agreed with the improvement in hair growth reported by doctors involved in the study.

Introduction

Alopecia areata (AA) is an autoimmune disease that has underlying immuno-inflammatory pathogenesis and is characterized by nonscarring hair loss involving the scalp, face, and/or body [1]. Hair loss may occur in one or many patches, or there may be complete scalp hair loss (alopecia totalis [AT]) or complete loss of scalp, facial, and body hair (alopecia universalis [AU]) [1]. Hair loss in patients with AA is unpredictable; relapse and remission may occur, although extensive hair loss is more likely to be persistent [2–4]. The global prevalence of AA has been estimated at approximately 2% [5], and patients with AA may experience psychological and psychosocial symptoms that have a negative impact on their quality of life [6–14].

The underlying pathogenesis of AA involves the collapse of immune privilege at the hair follicle, followed by recognition of exposed hair follicle autoantigens by T-cell receptors on cytotoxic CD8+ T cells [15–17]. Downstream signaling from the T-cell receptor involves the tyrosine kinase expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (TEC) kinase family, which may contribute to the autoimmune reaction that characterizes AA [18–22]. Interferon-γ, produced by multiple active immune cells, including CD8+ T cells, induces interleukin-15 production; both interferon-γ and interleukin-15 signal through Janus kinases (JAKs), perpetuating an inflammatory feed-forward loop, leading to the collapse of hair follicle immune privilege [23–25].

Patients report high levels of dissatisfaction with commonly used treatment options due to ineffectiveness and adverse effects [6, 11, 26]; however, new treatment options for AA have recently been approved. Currently, 2 therapies are approved for the treatment of severe AA. Baricitinib is a JAK1/2 inhibitor approved in the USA, Japan, EU, China, and several other countries for adults with severe AA [2]. Ritlecitinib is a selective dual inhibitor of JAK3 and all 5 members of the TEC family kinases that is approved for adolescent (12–17 years of age) and adult patients with severe AA in the USA, Japan, EU, China, and several other countries [4].

The ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 trial (NCT03732807) demonstrated significantly greater scalp hair growth per clinician-assessed Severity of Alopecia Tool (SALT) score with ritlecitinib compared with placebo over 24 weeks among patients aged ≥12 years with AA [4]. Patient-reported outcomes (PROs), including treatment satisfaction, are essential to understand the patient’s experience with ritlecitinib. The objective of this study was to evaluate patient-reported satisfaction with hair growth among patients with AA receiving ritlecitinib or placebo and the correlation between clinician-assessed efficacy and patient-reported satisfaction.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

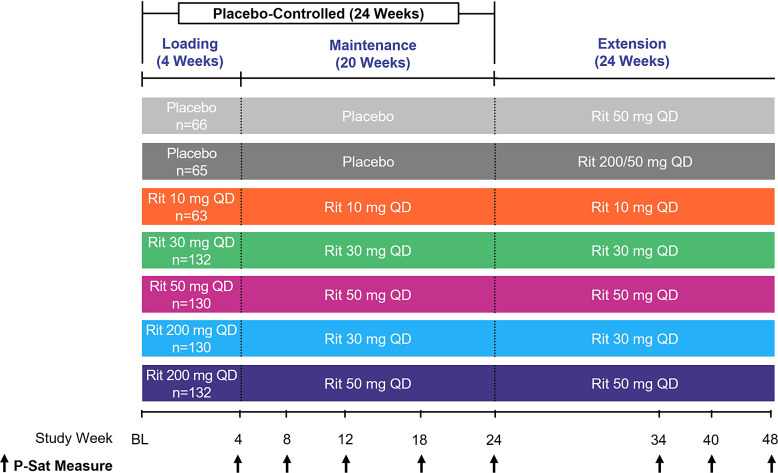

ALLEGRO-2b/3 was an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, combined dose-ranging and pivotal, phase 2b/3 study (Fig. 1) that enrolled both adult and adolescent patients with AA. The study design, including inclusion and exclusion criteria, has been published previously [4]. Briefly, patients ≥12 years of age with ≥50% scalp hair loss, including AT and AU, without evidence of terminal hair growth within 6 months, were included. The maximum duration of current episode of hair loss was restricted to ≤10 years.

Fig. 1.

Study design. BL, baseline; P-Sat, Patient Satisfaction with Hair Growth; QD, once daily; Rit, ritlecitinib.

Patients received once-daily ritlecitinib for 24 weeks ± an initial 4-week 200-mg loading dose: 10 mg, 30 mg, 50 mg, 200/30 mg, 200/50 mg, or placebo. After week 24, patients assigned to placebo switched to ritlecitinib 200/50 mg or 50 mg once daily for an additional 24 weeks; patients assigned to ritlecitinib continued their assigned maintenance dose.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards or Ethics Committees of the participating institutions (including the Western Institutional Review Board [now known as Western Institutional Review Board-Copernicus Group]; reference number 20182828); online suppl. Table 1; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000539536). The study was conducted in accordance with the general principles set forth in the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, 2002), International Council for Harmonisation Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient, parent, or patient’s legal representative.

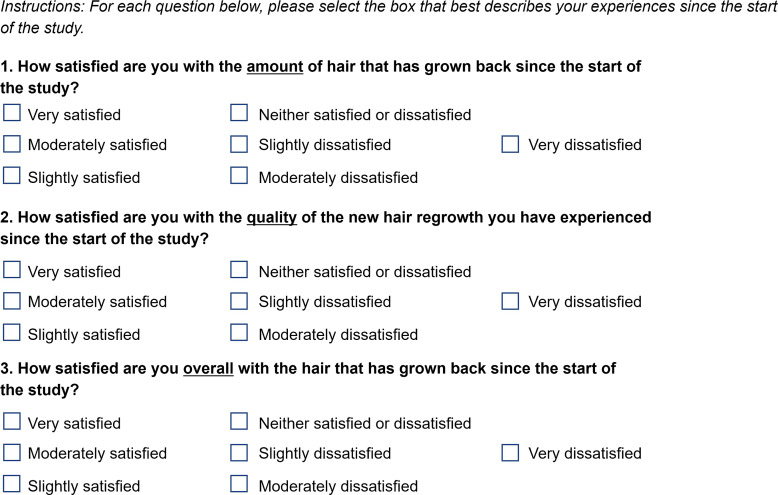

P-Sat Measure

The Patient Satisfaction with Hair Growth (P-Sat) measure (Fig. 2) was developed by Pfizer Inc through qualitative interviews with patients with AA. The measure evaluated patients’ satisfaction with hair growth since the start of the trial in 3 domains: amount, quality, and overall satisfaction. The P-Sat measure was administered at weeks 4, 8, 12, 18, 24, 34, 40, and 48.

Fig. 2.

P-Sat measure. P-Sat, Patient Satisfaction with Hair Growth.

Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

A prespecified analysis evaluated the proportion of patients reporting any satisfaction (slightly, moderately, or very satisfied) with hair growth. Post hoc analyses included (1) defining satisfaction as proportion of patients who were moderately or very satisfied with hair growth, (2) evaluating dissatisfaction defined as proportion of patients who reported they were moderately or very dissatisfied with hair growth, and (3) calculating polyserial correlations between change from baseline (CFB) in SALT scores and the 3 P-Sat domain scores at weeks 24 and 48 for all patients combined. Proportions were reported for all treatment groups up to and including week 48. p values were not controlled for multiplicity, and analyses were based on observed data without any imputations.

Results

Patients

A total of 718 patients in 18 countries were randomized (placebo, n = 131, 10 mg, n = 63; 30 mg, n = 132; 50 mg, n = 130; 200/30 mg, n = 130; 200/50 mg, n = 132). Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were generally balanced across treatment groups; the majority of patients in each group were female and White (Table 1) [4]. The mean duration of current AA episode ranged from 3.2 to 3.6 years across the groups. The proportion of patients in each group with AT/AU (defined as a SALT score of 100 at baseline) was ≥45%; for patients without AT/AU, the mean SALT score ranged from 78.3 to 87.0 across groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics [4]

| Placeboa (n = 131) | Ritlecitinib QD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 mg (n = 63) | 30 mg (n = 132) | 50 mg (n = 130) | 200/30 mg (n = 130) | 200/50 mg (n = 132) | ||

| Age | ||||||

| Mean (SD), years | 34.0 (15.0) | 34.3 (13.9) | 33.7 (14.8) | 32.4 (13.4) | 33.7 (13.8) | 34.5 (15.0) |

| 12–17 y, n (%) | 19 (14.5) | 9 (14.3) | 20 (15.2) | 18 (13.8) | 19 (14.6) | 20 (15.2) |

| ≥18 y, n (%) | 112 (85.5) | 54 (85.7) | 112 (84.8) | 112 (86.2) | 111 (85.4) | 112 (84.8) |

| Female, n (%) | 86 (65.6) | 43 (68.3) | 80 (60.6) | 71 (54.6) | 85 (65.4) | 81 (61.4) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 94 (71.8) | 42 (66.7) | 91 (68.9) | 79 (60.8) | 90 (69.2) | 92 (69.7) |

| Asian | 31 (23.7) | 17 (27.0) | 34 (25.8) | 43 (33.1) | 28 (21.5) | 33 (25.0) |

| Black or African American | 4 (3.1) | 2 (3.2) | 3 (2.3) | 5 (3.8) | 7 (5.4) | 6 (4.5) |

| Multiracial | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | 3 (2.3) | 0 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not reported | 0 | 1 (1.6) | 0 | 2 (1.5) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) |

| Severity of AA, n (%) | ||||||

| AT/AUb | 60 (45.8) | 29 (46.0) | 61 (46.2) | 60 (46.2) | 60 (46.2) | 60 (45.5) |

| Baseline SALT score, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Non-AT/AUb | 87.0 (12.9) | 78.3 (17.6) | 81.5 (16.3) | 82.0 (15.9) | 82.4 (15.4) | 82.2 (16.5) |

| Duration of current AA episode, mean (SD), years | 3.2 (2.7) | 3.3 (2.7) | 3.6 (2.8) | 3.2 (2.7) | 3.4 (2.9) | 3.4 (2.9) |

AA, alopecia areata; AT, alopecia totalis; AU, alopecia universalis; QD, once daily; SALT, Severity of Alopecia Tool.

aPlacebo alone for 24 weeks (and later switched to ritlecitinib).

bPatients in the AT/AU category had a SALT score of 100% at baseline as assessed by the investigator (regardless of the category in the AA history case report form).

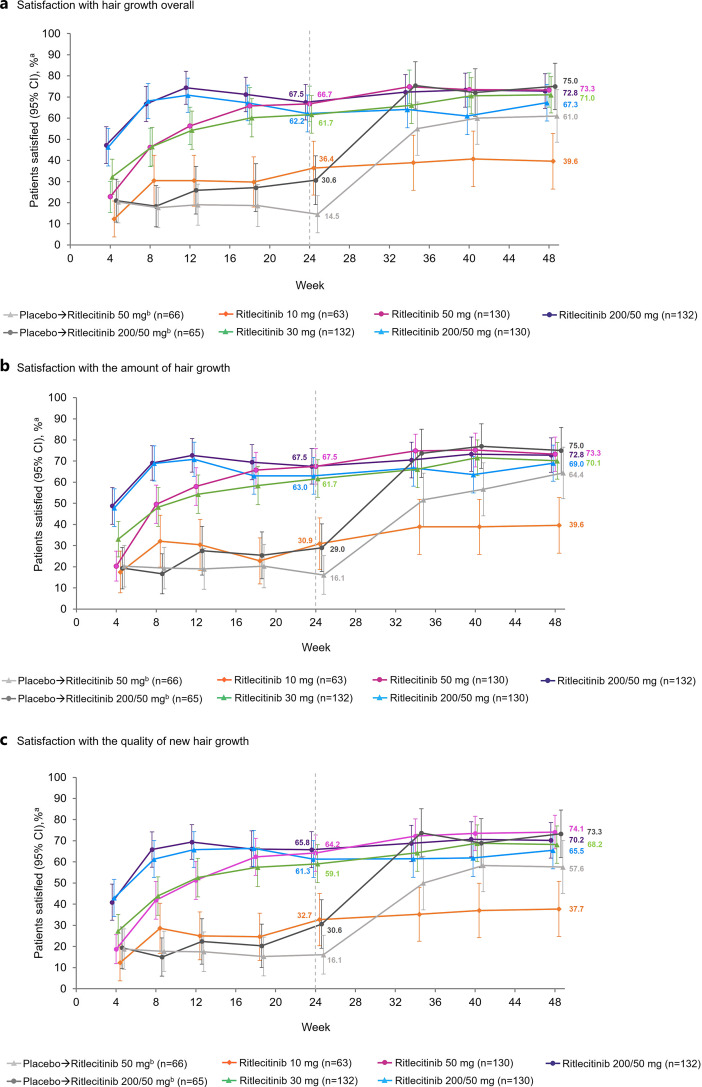

Prespecified Analysis of P-Sat

At week 24, the proportion of patients reporting satisfaction (primary outcome: slightly, moderately, or very satisfied) overall with their hair growth ranged from 36.4% in the ritlecitinib 10-mg group to 67.5% in the 200/50-mg ritlecitinib group compared with 22.6% in the placebo groups (30.6% in the placebo to ritlecitinib 200/50-mg group and 14.5% in the placebo to ritlecitinib 50-mg group; Fig. 3a). The proportion of patients satisfied with the amount of hair growth ranged from 30.9% in the ritlecitinib 10-mg group to 67.5% in the ritlecitinib 200/50-mg and 50-mg groups compared with 22.6% in the placebo groups (29.0% in the placebo to ritlecitinib 200/50-mg group and 16.1% in the placebo to ritlecitinib 50-mg group; Fig. 3b). The proportion of patients satisfied with the quality of hair growth ranged from 32.7% in the ritlecitinib 10-mg group to 65.8% in the 200/50-mg group compared with 23.4% in the placebo groups (30.6% in the placebo to ritlecitinib 200/50-mg group and 16.1% in the placebo to ritlecitinib 50-mg group; Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Proportion of patients reporting satisfaction (slightly, moderately, or very satisfied)a (a) with hair growth overall, (b) with the amount of hair growth, and (c) with the quality of new hair growth. aP-Sat response is defined as “slightly,” “moderately,” or “very satisfied.” bPatients received placebo until week 24 and then were switched to active ritlecitinib treatment.

Among patients who were randomized to active treatment with ritlecitinib (200/50, 50, 200/30, or 30 mg), the proportion who were satisfied overall and with the amount and quality of hair growth continued to increase or was maintained to week 48; satisfaction remained low in patients receiving ritlecitinib 10 mg (Fig. 3). Among patients who received placebo until week 24 and then switched to ritlecitinib 200/50 mg or 50 mg, a substantially greater proportion reported satisfaction overall (75.0% and 61.0%, respectively) and with the amount (75.0% and 64.4%) and quality of hair growth (73.3% and 57.6%) at week 48 than at week 24. At week 48, the proportion of patients in the placebo to ritlecitinib 200/50-mg group reporting satisfaction was similar to that of patients who had been receiving ritlecitinib 200/50 mg or 50 mg for the entire study.

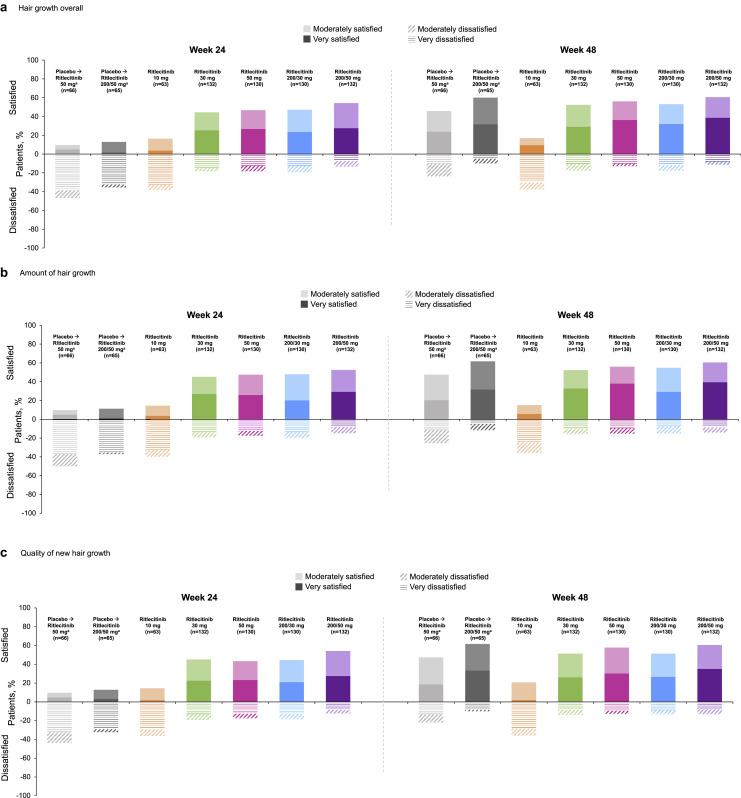

Post Hoc Analysis of P-Sat

Approximately half of patients randomized to receive active ritlecitinib treatment reported being moderately to very satisfied in all 3 P-Sat domains (amount, quality, and overall satisfaction) at week 24, with the overall proportion of patients moderately or very satisfied increasing or maintained to week 48 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Proportion of patients reporting moderately/very satisfied and moderately/very dissatisfied (a) with hair growth overall, (b) with the amount of hair growth, and (c) with the quality of new hair growth at weeks 24 and 48. a Patients received placebo until week 24 and then were switched to active ritlecitinib treatment.

Among patients receiving placebo until week 24 and then switching to ritlecitinib 200/50 mg or 50 mg, a substantially greater proportion were moderately or very satisfied in all 3 domains at week 48 than at week 24. At week 48, the proportion of patients in the placebo to ritlecitinib 200/50-mg group who were moderately or very satisfied was similar to that of patients who had been receiving ritlecitinib 200/50 mg or 50 mg for the entire study. The placebo group was twice as likely to report being dissatisfied (moderately or very dissatisfied) compared with active ritlecitinib treatment groups at week 24; dissatisfaction decreased by week 48 after patients switched over to active ritlecitinib treatment (Fig. 4).

Correlations between CFB-SALT Scores and the 3 P-Sat Domain Scores

All P-Sat domain scores were strongly correlated with CFB-SALT scores at week 24 (range, 0.73–0.76; p < 0.05) and week 48 (range, 0.74–0.77; p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation between P-Sat domains and CFB-SALT scores at weeks 24 and 48

| Measure | P-Sat domains, correlation coefficient (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| satisfaction with overall hair growth | satisfaction with amount of hair growth | satisfaction with quality of new hair growth | |

| CFB-SALT at week 24 (n = 647) | 0.76 (0.72–0.79) | 0.76 (0.72–0.79) | 0.73 (0.69–0.77) |

| CFB-SALT at week 48 (n = 621) | 0.77 (0.73–0.80) | 0.77 (0.73–0.80) | 0.74 (0.71–0.78) |

CFB-SALT, change from baseline in Severity of Alopecia Tool; P-Sat, Patient Satisfaction with Hair Growth.

p < 0.05 for all.

Discussion

In this analysis of the ALLEGRO-2b/3 trial, the proportion of patients reporting satisfaction (slightly, moderately, or very satisfied) overall and with the amount and quality of hair growth at week 24 was 2- to almost 3-fold higher in patients who received ritlecitinib doses >10 mg daily than in those who received placebo. Satisfaction increased or was maintained at week 48 among patients who were initially assigned to ritlecitinib and continued it in the extension period. A substantially greater proportion of patients in the placebo to ritlecitinib groups were moderately or very satisfied at week 48 than at week 24 (before switching from placebo); however, the proportion of patients in the placebo to ritlecitinib 200/50-mg group reporting satisfaction was ≈30% across the 3 P-Sat domains at week 24. In the secondary analysis defining satisfaction as moderately or very satisfied, the benefit of ritlecitinib on patient satisfaction with hair growth was also observed.

The benefit of ritlecitinib was also seen in the smaller proportion of patients who received ritlecitinib reporting dissatisfaction (moderately or very dissatisfied) compared with placebo. The strong correlations observed between CFB-SALT scores and P-Sat indicated a high concordance between improvement in scalp hair growth as evaluated by clinicians and patient-reported satisfaction. These are the first randomized clinical trial data demonstrating a higher proportion of patients reporting satisfaction with a treatment compared with placebo, as directly assessed by a patient-reported instrument measuring patient satisfaction with hair growth.

Patients with AA may experience psychological and psychosocial symptoms such as depression, anxiety, anger, social withdrawal, embarrassment, and low self-esteem due to their hair loss, which can have a substantial negative impact on their quality of life [6–8, 11, 14]. Furthermore, patients report high levels of dissatisfaction with commonly used treatment options due to ineffectiveness and adverse effects [6, 11, 26]. A survey conducted by the National Alopecia Areata Foundation in 1083 patients with AA reported that >75% of patients were unsatisfied with current medical treatments (63% [n = 682] were very unsatisfied and 15% [n = 164] were somewhat unsatisfied) [26]. Therefore, a need for safe and effective treatments for AA exists due to the significant burden on patients combined with the ineffectiveness of commonly used treatments.

Evaluation of therapies for AA should include PRO measures in addition to clinician-reported outcomes. Understanding treatment outcomes that are important to patients is recommended for the development of clinical trial endpoints [6, 27]. The P-Sat measure was developed based on qualitative patient input and includes patient satisfaction with not only overall hair growth and amount of hair growth but also the quality of hair growth. Quality of hair growth may be a concern for some patients with AA because hair that regrows may not have the same color or texture as hair that was lost [28–30]. Results from the analysis of both the prespecified and post hoc definitions (slightly, moderately, or very satisfied and moderately or very satisfied, respectively) of patient satisfaction with ritlecitinib treatment were consistent across all 3 of the P-Sat domains evaluated.

Patient satisfaction with hair growth may be affected by multiple factors, including the extent of hair loss at the start of treatment, duration of hair loss, level of acceptance of and coping strategies for hair loss, experience with previous treatments, and expectations of treatment results. Expectations for hair growth following treatment have been shown to vary based on patients’ current hair loss [31], and nonlinear relationships between health-related quality of life measures and AA severity have been demonstrated [32]. In addition, coping strategies in patients with AA may evolve over time [33]. In the present analysis, high satisfaction rates were observed in a population of patients that had no hair growth in the previous 6 months (46% of whom had AT/AU) and had a mean duration of current AA episode of >3 years. The proportion of patients in the ritlecitinib 10-mg group who reported satisfaction did not significantly differ from the placebo to ritlecitinib 200/50-mg group while these patients were receiving placebo; there was a substantial increase in proportion of patients in the placebo to ritlecitinib 200/50-mg group reporting satisfaction once treatment with ritlecitinib was initiated after week 24. The favorable results with ritlecitinib versus placebo in patient satisfaction with hair regrowth were consistent with improvements in other PROs in the ALLEGRO-2b/3 trial, including patient perception of treatment benefit as measured by the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGI-C) [4] and Alopecia Areata Patient Priority Outcomes (AAPPO) measure of hair loss experienced by patients [34].

Limitations of this study include the majority of patients being White, with <6% of Black or African American patients in all treatment groups; thus, these results may not be representative of all patients with AA. The P-Sat measure was designed to encapsulate all areas of hair growth and did not evaluate patient satisfaction by area of the body, and as a result, the effect of specific areas of hair growth (e.g., scalp hair vs. eyebrow/eyelash growth) on patient satisfaction with hair growth was not evaluated. Differences in growth of scalp hair versus eyebrows/eyelashes may affect patient satisfaction because eyebrow and eyelash growth are important to patients with AA [6, 35, 36]. However, in ALLEGRO-2b/3, improvement in eyebrows or eyelash growth was associated with a higher likelihood of SALT response [37]; therefore, a difference in patient-reported satisfaction would not be expected.

Conclusions

Patients receiving ritlecitinib reported overwhelmingly higher rates of satisfaction with hair growth compared with placebo. This is the first study using placebo-controlled clinical data demonstrating the impact of a treatment for AA on patient satisfaction that includes overall satisfaction and satisfaction with the quality and amount of hair. These results confirm the benefit to patients of treatment of their AA.

Key Message

Patients receiving ritlecitinib reported higher satisfaction rates with their hair growth compared with placebo.

Acknowledgments

Writing and scientific support were provided by Shailja Vaghela, MPH, and funded by Pfizer Inc. Third-party medical writing assistance provided by Nicola Gillespie, DVM, of Nucleus Global was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards or Ethics Committees of the participating institutions. The study was conducted in accordance with the general principles set forth in the International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects (Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences, 2002), ICH Guideline for Good Clinical Practice, and the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient, parent, or the patient’s legal representative.

Conflict of Interest Statement

R.S. has provided professional services to AbbVie, Aerotech, Amgen, Arena, Arcutis, Aksebio, AstraZeneca, Ascend, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Coherus Biosciences, Cutanea, Connect, Demira, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GSK, Janssen, LEO Pharma, MedImmune, Merck, MSD, Novartis, Oncobiologics, Pfizer, Regeneron, Reistone, Roche, Sanofi, Samson Clinical, Sun Pharma, and UCB. E.H.L. and L.N. are employees of and hold stock or stock options in Pfizer Inc. F.Z. and S.H.Z. were employees of and held stock or stock options in Pfizer Inc at the time of the study and manuscript preparation. X.Z.: no disclosures to report. B.K. has received honoraria and/or consultation fees from AbbVie, AltruBio Inc, Almirall, AnaptysBio, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Aslan Pharmaceuticals, Bioniz Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Concert Pharmaceuticals Inc, Equillium, Horizon Therapeutics, Eli Lilly and Company, Incyte Corp, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, LEO Pharma, Merck, Otsuka/Visterra Inc, Pfizer Inc, Q32 Bio Inc, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, Sun Pharmaceutical, TWi Biotechnology Inc, Viela Bio, and Ventyx Biosciences Inc. He has served on speaker bureaus for AbbVie, Incyte, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron, and Sanofi Genzyme. N.M. has provided professional services to AbbVie, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers Squibb, Concert Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, La Roche-Posay, and Pfizer.

Funding Sources

This study was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Author Contributions

Ernest H. Law, Lynne Napatalung, and Samuel H. Zwillich contributed conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis (supporting), investigation, writing – original draft, and writing – review and editing. Xingqi Zhang, Rodney Sinclair, Natasha Mesinkovska, and Brett King contributed data curation, formal analysis (supporting), investigation, and writing – review and editing. Fan Zhang contributed conceptualization, methodology, data curation, formal analysis (lead), investigation, and writing – review and editing.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by Pfizer Inc.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available for the protection of study participant privacy; however, upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.

Supplementary Material.

References

- 1. Islam N, Leung PS, Huntley AC, Gershwin ME. The autoimmune basis of alopecia areata: a comprehensive review. Autoimmun Rev. 2015;14(2):81–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. King B, Ohyama M, Kwon O, Zlotogorski A, Ko J, Mesinkovska NA, et al. Two phase 3 trials of baricitinib for alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(18):1687–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. King B. Top-line results from THRIVE-AA1: a phase 3 clinical trial of CTP-543 (deuruxolitinib), an oral JAK inhibitor, in adult patients with moderate to severe alopecia areata. 31st Annual Meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). 2022; Abstract 3473. [Google Scholar]

- 4. King B, Zhang X, Harcha WG, Szepietowski JC, Shapiro J, Lynde C, et al. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2b-3 trial. Lancet. 2023;401(10387):1518–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lee HH, Gwillim E, Patel KR, Hua T, Rastogi S, Ibler E, et al. Epidemiology of alopecia areata, ophiasis, totalis, and universalis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(3):675–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. US Food and Drug Administration . Patient-focused drug development public meeting for alopecia areata. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/industry/prescription-drug-user-fee-amendments/patient-focused-drug-development-public-meeting-alopecia-areata (last accessed December 5, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu LY, King BA, Craiglow BG. Alopecia areata is associated with impaired health-related quality of life: a survey of affected adults and children and their families. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):556–8.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Okhovat JP, Marks DH, Manatis-Lornell A, Hagigeorges D, Locascio JJ, Senna MM. Association between alopecia areata, anxiety, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88(5):1040–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Aldhouse NVJ, Kitchen H, Knight S, Macey J, Nunes FP, Dutronc Y, et al. “You lose your hair, what’s the big deal?’ I was so embarrassed, I was so self-conscious, I was so depressed:” a qualitative interview study to understand the psychosocial burden of alopecia areata. J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4(1):76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marahatta S, Agrawal S, Adhikari BR. Psychological Impact of alopecia areata. Dermatol Res Pract. 2020;2020:8879343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mesinkovska N, King B, Mirmirani P, Ko J, Cassella J. Burden of illness in alopecia areata: a cross-sectional online survey study. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20(1):S62–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mostaghimi A, Napatalung L, Sikirica V, Winnette R, Xenakis J, Zwillich SH, et al. Patient perspectives of the social, emotional and functional impact of alopecia areata: a systematic literature review. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(3):867–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Toussi A, Barton VR, Le ST, Agbai ON, Kiuru M. Psychosocial and psychiatric comorbidities and health-related quality of life in alopecia areata: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85(1):162–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim AB, Cheng BT, Hassan S. Association of mental health outcomes and lower patient satisfaction among adults with alopecia: a cross-sectional population-based study. JAAD Int. 2022;8:82–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Paus R, Ito N, Takigawa M, Ito T. The hair follicle and immune privilege. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2003;8(2):188–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang EHC, Yu M, Breitkopf T, Akhoundsadegh N, Wang X, Shi FT, et al. Identification of autoantigen epitopes in alopecia areata. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136(8):1617–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bertolini M, McElwee K, Gilhar A, Bulfone-Paus S, Paus R. Hair follicle immune privilege and its collapse in alopecia areata. Exp Dermatol. 2020;29(8):703–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schwartzberg PL, Finkelstein LD, Readinger JA. TEC-family kinases: regulators of T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5(4):284–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andreotti AH, Schwartzberg PL, Joseph RE, Berg LJ. T-cell signaling regulated by the Tec family kinase, Itk. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(7):a002287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Smith SE, Neier SC, Reed BK, Davis TR, Sinnwell JP, Eckel-Passow JE, et al. Multiplex matrix network analysis of protein complexes in the human TCR signalosome. Sci Signal. 2016;9(439):rs7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Howell MD, Kuo FI, Smith PA. Targeting the Janus kinase family in autoimmune skin diseases. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Solimani F, Meier K, Ghoreschi K. Emerging topical and systemic JAK inhibitors in dermatology. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gilhar A, Paus R, Kalish RS. Lymphocytes, neuropeptides, and genes involved in alopecia areata. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(8):2019–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Murray PJ. The JAK-STAT signaling pathway: input and output integration. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):2623–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Triyangkulsri K, Suchonwanit P. Role of Janus kinase inhibitors in the treatment of alopecia areata. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12:2323–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hussain ST, Mostaghimi A, Barr PJ, Brown JR, Joyce C, Huang KP. Utilization of mental health resources and complementary and alternative therapies for alopecia areata: a US survey. Int J Trichology. 2017;9(4):160–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. US Food and Drug Administration . Patient-focused drug development guidance public workshop: methods to identify what is important to patients & select, develop or modify fit-for-purpose clinical outcomes assessments. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/media/116276/download (accessed December 5, 2022).

- 28. Wade MS, Sinclair RD. Persistent depigmented regrowth after alopecia areata. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46(4):619–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dinh QQ, Chong AH. A case of widespread non-pigmented hair regrowth in diffuse alopecia areata. Australas J Dermatol. 2007;48(4):221–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Valins W, Vega J, Amini S, Woolery-Lloyd H, Schachner L. Alteration in hair texture following regrowth in alopecia areata: a case report. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147(11):1297–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Macey J, Kitchen H, Aldhouse NVJ, Burge RT, Edson-Heredia E, McCollam JS, et al. Dermatologist and patient perceptions of treatment success in alopecia areata and evaluation of clinical outcome assessments in Japan. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11(2):433–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gelhorn HL, Cutts K, Edson-Heredia E, Wright P, Delozier A, Shapiro J, et al. The relationship between patient-reported severity of hair loss and health-related quality of life and treatment patterns among patients with alopecia areata. Dermatol Ther. 2022;12(4):989–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Welsh N, Guy A. The lived experience of alopecia areata: a qualitative study. Body Image. 2009;6(3):194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sinclair R, Mesinkovska N, Mitra D, Wajsbrot D, Wolk R, King B. Improvement in a patient-reported hair loss outcome measure, the AAPPO, in patients with alopecia areata treated with ritlecitinib: 48-week results from the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am Acad Dermatol. 2022. Abstract 33280. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu LY, King BA, Ko JM. Eyebrows Are important in the treatment of alopecia areata. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20(1):S37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wyrwich KW, Kitchen H, Knight S, Aldhouse NVJ, Macey J, Nunes F, et al. The role of patients in alopecia areata endpoint development: understanding physical signs and symptoms. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2020;20(1):S71-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Holmes S, Rudnicka L, Blauvelt A, Zlotogorski A, Ocampo Candiani J, Edwards R, et al. Association between early eyebrow/eyelash assessments and subsequent scalp hair regrowth in patients with alopecia areata treated with ritlecitinib: post hoc analysis of the ALLEGRO phase 2b/3 study. 31st Annual Meeting of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV). 2022; Abstract 581. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available for the protection of study participant privacy; however, upon request, and subject to review, Pfizer will provide the data that support the findings of this study. Subject to certain criteria, conditions and exceptions, Pfizer may also provide access to the related individual de-identified participant data. See https://www.pfizer.com/science/clinical-trials/trial-data-and-results for more information.