Abstract

Genetic resistance and susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis have been linked with the production of interleukin-4 (IL-4) or gamma interferon (IFN-γ), respectively. To determine the absolute requirement for these cytokines in disease outcome, we compared arthritis development in wild-type, IL-4-deficient (IL-4°), and IFN-γ-deficient (IFN-γ°) mice. While susceptible C3H mice developed swelling of ankle joints during the second week of infection, this swelling was exacerbated in C3H IFN-γ° mice. Their arthritis severity scores at day 21, however, were similar. Resolution of arthritis was also similar between C3H and C3H IFN-γ° mice. Arthritis-resistant DBA mice did not develop ankle swelling during the experimental period. There were no differences in ankle swelling or arthritis severity scores between control DBA mice and DBA IL-4° mice at any of the time points tested. While the presence of spirochetes in various tissues was similar among all strains at day 21, DBA IL-4° mice had a higher presence of spirochetes in blood, heart, and spleen than the DBA, C3H, and C3H IFN-γ° mice did at day 60. DBA IL-4° mice also had impaired ability to produce Borrelia-specific antibody responses, especially immunoglobulin G1. Thus, while IFN-γ and IL-4 are not absolutely required for arthritis susceptibility or resistance, the production of IL-4 does appear to play an important role in Borrelia-specific antibody production and spirochete clearance.

Experimental Lyme borreliosis is caused by the infection of inbred strains of mice with the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. While all mouse strains are susceptible to infection with B. burgdorferi, only certain strains develop severe arthritis (2). C3H/HeJ (C3H) mice will develop severe arthritis when infected with as few as 200 spirochetes (20). In contrast, C57BL/6J (B6) or DBA/2J (DBA) mice are resistant to arthritis development even when infected with 106 spirochetes (6, 20). BALB/c mice represent an intermediate-responding strain, which are resistant to arthritis development when challenged with low numbers of spirochetes, but develop arthritis of increasing severity as the infectious dosage is increased (20). Clearly, host factors play critical roles in determining the extent of arthritis following infection with B. burgdorferi.

The development of arthritis following experimental inoculation of mice with B. burgdorferi correlates with T-cell subset development (17, 21). T cells from arthritis-resistant BALB/c mice produce interleukin-4 (IL-4) and develop a Th2 phenotype following infection with B. burgdorferi (17, 21). In contrast, T cells from arthritis-susceptible C3H mice produce gamma interferon (IFN-γ) and develop a Th1 phenotype following infection with B. burgdorferi (17, 21). Treatment of BALB/c mice with antibody to IL-4 increased the severity of arthritis, while treatment of C3H mice with either antibody to IFN-γ or recombinant IL-4 reduced arthritis development (17, 18, 21). These results suggested that T-cell cytokines might be important mediators of resistance and susceptibility to Lyme arthritis development. Recent reports, however, have indicated that these cytokines may not be absolutely required for disease modulation. Signaling through B7-1 and B7-2 has been shown to influence arthritis severity in susceptible C3H mice (1). Blocking of B7-CD28 interactions in BALB/c mice, however, decreased IL-4 production and increased IFN-γ levels, but did not alter arthritis development (27). The timing of IL-4 production also suggests it may act to resolve arthritis inflammation, not prevent it (15). Similarly, we have recently shown that depletion of NK cells in C3H mice ablates their early IFN-γ production, but does not alter arthritis development (7). Thus the absolute roles of IL-4 and IFN-γ in resistance and susceptibility to Lyme arthritis development are unclear.

To assess the requirement for IL-4 and IFN-γ in resistance or susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis, we infected DBA IL-4-deficient (DBA IL-4°) or C3H IFN-γ-deficient (C3H IFN-γ°) mice and monitored arthritis development and resolution. Our results show that IFN-γ deficiency has little effect on either arthritis development and resolution or on mounting an efficient immune response against B. burgdorferi. While IL-4 deficiency in DBA mice had little effect on their resistance to arthritis development, they were unable to mount an effective antibody response to B. burgdorferi and were unable to efficiently clear spirochetes from their tissues.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

All mice were females between 4 and 6 weeks of age at the time of infection. DBA/2J (DBA) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine). DBA IL-4° mice were generated from BALB/c IL-4° mice (a generous gift from Horst Bluthmann [F. Hoffman-La Roche AG]) by backcrossing to DBA mice for 5 generations. C3H IFN-γ° mice were generated from C57BL/6 × 129 IFN-γ° mice (a kind gift from Genentech) by backcrossing to C3H for 5 generations. Littermate C3H IFN-γ+/+ or C3H IFN-γ+/− were used as control animals.

Bacteria and infections.

The N40 strain of B. burgdorferi was kindly provided by Steven Barthold (Yale University, New Haven, Conn.), and spirochetes were recovered from samples frozen in aliquots as described previously (6). Mice were inoculated in both hind footpads with 5 × 105 B. burgdorferi organisms in 50 μl of Barbour-Stoenner-Kelley II medium (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.). Tibiotarsal joints were measured weekly with a metric caliper (Ralmike’s Tool-A-Rama, South Plainfield, N.J.) through the thickest anteroposterior diameter of the ankle. Mice were sacrificed on day 21 or 60 following infection. Blood, heart, spleen, urinary bladder, skin, and ankles were aseptically collected and cultured at 32°C for 14 days in Barbour-Stoenner-Kelley media. Cultures were read by placing 10 μl of supernatant on a microscope slide under a 22 by 22 mm coverslip and examining 20 high-powered fields by dark-field microscopy. In some experiments, one ankle from each mouse was frozen for PCR analysis. In other experiments, one ankle from each mouse was formalin fixed, embedded in paraffin, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and blindly evaluated for arthritis severity on a scale of 0 to 3 (3). Grade 0 represents no inflammation, grades 1 and 2 represent mild to moderate inflammation, and grade 3 represents severe inflammation. Arthritis in histological samples was characterized by neutrophil and monocyte infiltration into the joints, tendons, and ligament sheaths; hyperplasia and hypertrophy of the synovium; and fibrin exudates. The extent of the observed inflammatory changes provided the basis for the arthritis severity scores.

PCR analysis.

To extract DNA from ankles, samples were first incubated in 0.5 ml of 1% collagenase overnight at 37°C. Tissue was then digested by incubation in 0.25 ml of 3× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-Tris lysis buffer (0.3 mg of proteinase K per ml in 600 mM NaCl–20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]–150 mM EDTA–0.6% SDS) for 16 h at 55°C. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and precipitated with ethanol. The sample DNA was resuspended in 200 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer. DNA samples from uninfected mice were tested as negative controls. Competitive PCR was performed as described previously (6) by using a constant amount of the BC3 polycompetitor and approximately 150 ng of sample DNA. The BC3 polycompetitor consists of a linear DNA molecule which contains modified portions of the ospA and flagellin genes of B. burgdorferi and a modified portion of the promoter region of the single-copy mammalian IL-4 gene (IL-4pr) (6). The presence of B. burgdorferi ospA in sample DNA was detected with the following primers: ospA 5′ primer TCTTGAAGGAACTTTAACTGCTG and ospA 3′ primer CAAGTTTTGTAATTTCAACTGCTGA. PCR mixtures were denatured for 60 s at 94°C, followed by cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 60 s, annealing at 60°C for 60 s, and extension at 72°C for 90 s for 35 cycles. Amplified products were visualized on a 2.5% agarose gel.

ELISA for IgG.

For the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for immunoglobulin G (IgG), mice were bled from the retro-orbital plexus prior to infection and then every 10th day for the remainder of the experiment. Serum was collected and stored at 4°C until analyzed. Briefly, 96-well Immulon plates were coated with 40 μl of sonicated B. burgdorferi antigen (30 μg/ml) overnight at 4°C. The wells were then blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 2 h at room temperature. Dilutions of mouse serum (1:100 in 3% BSA) were added to replicate plates and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Samples were then incubated with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rat anti-mouse antibodies to IgG1, IgG2a, IgG2b, and IgG3 (all from PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) or IgG (heavy plus light chains) (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, Pa.), diluted 1:1,000 in 3% BSA in PBS, and incubated at room temperature for 45 min. Plates were developed with Sigma 104 reagent (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and read at 405 nm on a spectrophotometer.

Statistics.

Data were analyzed by Student’s t test for single comparisons or Tukey’s test for multiple comparisons. Critical values for statistical significance were set at α = 0.05.

RESULTS

Development of arthritis.

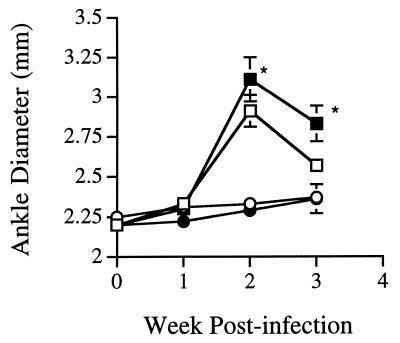

To determine the absolute requirement for the production of IL-4 and IFN-γ on disease resistance or susceptibility, we infected C3H IFN-γ° and DBA IL-4° mice along with wild-type controls and observed arthritis development for 21 or 60 days. C3H and C3H IFN-γ° mice developed severe swelling of their tibiotarsal joints by 14 days following inoculation of 5 × 105 B. burgdorferi organisms into their hind footpads (Fig. 1). The footpad route of infection was used to deliver the organisms near the tibiotarsal joints and to control for differences in spirochete dissemination between mice of different strains and with immunological deficiency. DBA and DBA IL-4° mice did not develop any ankle swelling during the experimental period. Ankle diameters of C3H and C3H IFN-γ° mice were significantly larger than those of DBA and DBA IL-4° mice on days 14 and 21 of infection (P < 0.001). C3H IFN-γ° mice had consistently greater ankle swelling than wild-type C3H mice during the acute phase of arthritis development (P < 0.01). Arthritis resolution, however, was similar for C3H and C3H IFN-γ° mice, and ankle swelling was completely resolved by day 60 in both strains (data not shown). There were no differences in ankle swelling between DBA and DBA IL-4° mice during either arthritis development (Fig. 1) or resolution (data not shown). Similar results were seen with BALB/c and BALB/c IL-4° mice (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Ankle swelling following infection of IL-4° and IFN-γ° mice with B. burgdorferi. Mice (three to five per group) were 4 to 6 weeks old at the time of infection and were inoculated in the hind footpads. Panels are representative of five separate experiments. Open symbols represent wild-type animals, and solid symbols represent cytokine-deficient animals. Ankle curves are shown for C3H (squares) and DBA (circles) mice. Error bars represent standard deviation. Asterisks indicate significant differences in ankle swelling between C3H IFN-γ° and C3H mouse strains (P < 0.01).

Arthritis development was also examined histologically, since it does not always correlate with ankle diameter. Hematoxylin-and-eosin-stained sections of ankle tissue were scored for arthritis severity in a blinded manner as previously described (3). A severity score of 0 represents no inflammation, while a score of 3 represents severe arthritis. At day 21, severity scores were significantly higher for C3H and C3H IFN-γ° mice than for the DBA and DBA IL-4° mice (Table 1; P < 0.001). There were no differences, however, in severity scores between C3H and C3H IFN-γ° mice. Arthritis severity scores of DBA IL-4° mice tended to be slightly lower than those of wild-type DBA mice, but these differences were not statistically significant. At day 60, arthritis severity scores were similar between all strains tested (Table 1). However, while the scores had decreased for all other strains, the arthritis severity scores of DBA IL-4° mice were nearly identical to those from day 21. This suggested that spirochete clearance might not be as efficient in these mice.

TABLE 1.

Isolation of B. burgdorferi from selected tissues and arthritis development in ankles of control and cytokine knockout micea

| Strain | Day | Arthritis severityb | No. of cultures positive/no. tested

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joint | Blood | Heart | Spleen | Bladder | Ear | |||

| C3H | 21 | 2.1 ± 0.6* | 5/6 | 0/9 | 3/5 | 4/8 | 3/9 | 8/8 |

| C3H IFN-γ° | 21 | 2.2 ± 0.6* | 8/11 | 2/11 | 4/10 | 6/11 | 10/11 | 6/6 |

| DBA | 21 | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 8/9 | 3/10 | 4/10 | 2/10 | 9/10 | 8/10 |

| DBA IL-4° | 21 | 0.7 ± 0.5 | 9/13 | 3/13 | 3/13 | 1/13 | 11/13 | 9/13 |

| C3H | 60 | 1.0 ± 1.0 | 6/10 | 0/10 | 3/10 | 2/10 | 10/10 | 8/10 |

| C3H IFN-γ° | 60 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 3/7 | 0/7 | 1/7 | 0/7 | 6/7 | 5/7 |

| DBA | 60 | 0.3 ± 0.6 | 2/8 | 0/8 | 1/8 | 0/8 | 8/8 | 8/8 |

| DBA IL-4° | 60 | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 10/16 | 3/16 | 8/16 | 6/16 | 13/16 | 16/16 |

Mice were infected with 5 × 105 B. burgdorferi organisms and sacrificed at 21 or 60 days. Tibiotarsal arthritis severity was scored on a scale from 0 to 3. (Means ± standard deviation are shown.)

Asterisks indicate that C3H background severity scores were significantly higher than those of DBA background mice (P < 0.001).

Spirochete burden in tissues.

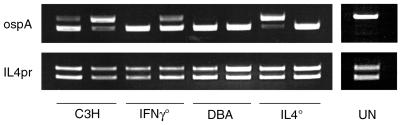

The effect of deficiency in IFN-γ or IL-4 might not only alter arthritis development, but might also affect the ability of mice to mount effective immune responses against B. burgdorferi. To determine if there were differences in spirochetal burdens in tissues, we sacrificed knockout and wild-type mice at these two time points, cultured various tissues, and scored them 14 days later for the presence of spirochetes. At day 21, during the acute phase of infection, few differences can be seen between mouse strains in the presence of B. burgdorferi spirochetes in the various tissues (Table 1). Cultures from tissues with high spirochete tropism—urinary bladder, skin (ear punches), and ankles—were almost uniformly positive. The presence of spirochetes in other tissues was more variable, but few differences between wild-type and knockout mice could be seen (Table 1). At day 60, however, the DBA IL-4° mice still had high numbers of positive cultures in blood, heart, and spleen samples, while the other mouse strains had mostly cleared these tissues (Table 1). To compare the absolute numbers of spirochetes, we used competitive PCR of ankle joints. Figure 2 shows the comparative levels of spirochete DNA in ankles from mice infected for 60 days. These results show that, although there was some variability between strains and among mice of the same strain, the DBA IL-4° mice did not have greatly increased levels of spirochetes within their ankle tissues.

FIG. 2.

Competitive PCR amplification of ospA and IL-4pr genes from ankles of C3H, C3H IFN-γ°, DBA, and DBA IL-4° mice. The control lane contains DNA from an uninfected mouse. The upper bands in each lane are the BC3 competitor amplification products, and the lower bands are wild-type DNA PCR products. Each lane represents data from an individual mouse. Sample DNA levels were equalized by using primers for the single-copy mammalian IL-4pr gene. Spirochete DNA was amplified by using primers for ospA. The amount of BC3 competitor spiked into each sample was 0.25 pg.

Borrelia-specific antibody responses.

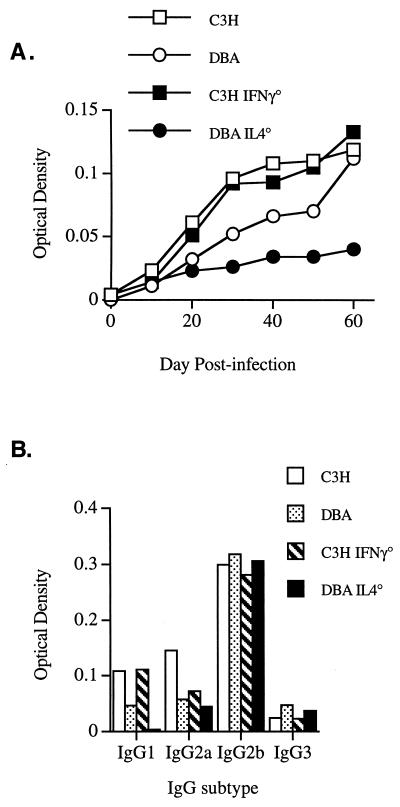

Resolution of Lyme arthritis and spirochetal clearance has been mainly attributed to the production of antibody (4). T cells may be involved, however, especially through the production of cytokines which promote antibody production. Th1 cytokines promote increased levels of IgG2a, while Th2 cytokines promote increased levels of IgG1 and IgG2b. To determine if the IL-4 or IFN-γ deficiency caused any changes in Borrelia-specific antibody responses, control and knockout mice were bled every 10 days during the infection and antibody responses were measured by ELISA. The production of total Borrelia-specific IgG over the course of the experiment is shown in Fig. 3A. While C3H, C3H IFN-γ°, and DBA mice made increasing amounts of anti-Borrelia IgG during the infection, the DBA IL-4° mice had depressed antibody responses. As expected, C3H IFN-γ° mice had depressed levels of IgG2a compared with wild-type C3H mice and produced levels similar to that of mice on the susceptible DBA background (Fig. 3B). While levels of IgG2b were similar between all mice tested, DBA IL-4° mice had greatly depressed production of IgG1. Since IgG1 makes up approximately 80% of the IgG antibody levels in mice, this deficiency could explain the low total IgG levels seen in the DBA IL-4° mice (Fig. 3A). Thus, IL-4 may play an important role in resistant mouse strains by promoting Borrelia-specific IgG1 production and contributing to efficient spirochetal clearance.

FIG. 3.

IgG in B. burgdorferi-infected control, IFN-γ°, and IL-4° mice. Antibody titers in sera were measured by ELISA for total IgG over the course of the infection (A) and for IgG subsets on day 60 (B).

DISCUSSION

Resistance or susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis development has been correlated with the production of IL-4 or IFN-γ, respectively, and T helper cell subset development (17, 21). Mice with a Th2 phenotype were resistant, and mice with a Th1 phenotype were susceptible. Moreover, treatment of mice with antibody to IL-4 or IFN-γ could attenuate or exacerbate arthritis development (17, 18, 21). These studies supported the hypothesis that genetic resistance and susceptibility to Lyme arthritis were mediated by T helper cell subset phenotypes. Studies with humans also supported this view; for example, peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with active disease produced more IFN-γ and less IL-4 than those from controls (23). Similarly, the Th1/Th2 ratio was highest in patients with active disease (13), and high numbers of T cells with the Th1 phenotype can be isolated from these types of patients (30). The absolute requirement of these cytokines for resistance or susceptibility, however, has been challenged recently. In the present study, we demonstrated that IFN-γ was not absolutely required for arthritis development or resolution or for the generation of an effective immune response. Likewise, IL-4 was also not absolutely required for resistance to arthritis development, but may play an important role in stimulating an effective immune response. Likewise, IL-4 was also not absolutely required for resistance to arthritis development, but may play an important role in stimulating an effective immune response against B. burgdorferi.

The production of IL-4 is an important mediator of T-cell help to B cells in the production of antibodies to T-dependent antigens. B. burgdorferi-specific humoral responses are thought to be the primary mediators of arthritis resolution and bacterial clearance (4). SCID mice can be protected from arthritis by the transfer of presensitized spleen cells and partially by B cells, but not by T cells alone (26). Similarly, transfer of immune sera, but not T cells, will induce arthritis resolution in B. burgdorferi-infected SCID mice (4, 5). Recent studies have shown that arthritis-protective antibodies can arise without the need for T-cell help. For example, protective antibodies arise and arthritis resolves in CD40 ligand-deficient mice and also in mice deficient in major histocompatibility complex class II and CD4+ T cells (10). Also, a single exposure of mice to B. burgdorferi elicits IgG characteristic of secondary immune responses without the production of IL-4 by immune T cells (12). In contrast, other studies using intradermal infection of mice with B. burgdorferi have suggested that CD4+ T cells and T-dependent antibody responses may play a role in protection against arthritis development, since depletion of CD4+ T cells results in an increase in ankle swelling (16), and passive transfer of CD4+ Th2 T cell lines or clones can also protect against pathology (24, 25). In the present study, footpad inoculation of DBA IL-4° mice resulted in a significant decrease in their B. burgdorferi-specific total IgG production. Most of this decrease was of the IgG1 subtype. While the IL-4 deficiency appeared to have no effect on the resistance of these mice to arthritis development, it did appear to have an effect on arthritis resolution and spirochetal clearance in certain tissues. Arthritis severity scores decreased in the other mouse strains from day 21 to day 60. In the DBA IL-4° mice, however, there was no decrease in the arthritis severity scores, suggesting a defect in arthritis resolution, possibly mediated by a T-dependent antigen. Spirochetes appeared to be as efficiently cleared from ankles in the DBA IL-4° mice as in the other strains of mice. However, clearance from blood, hearts, and spleens appeared to be less efficient. This is similar to the effect reported by others using the intradermal infection model that CD4+ T cells might be required for resolution of carditis (10).

In conclusion, these results demonstrate that IFN-γ is not required for arthritis development or resolution, nor is it needed for efficient control of spirochetal burdens. In contrast, while IL-4 is not required for resistance to arthritis development, it does appear to play a role in arthritis resolution and spirochetal clearance from specific tissues, possibly through B-cell help and production of T-dependent antibodies. While it is clear that these cytokines are not required for genetic resistance or susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis development, other studies have shown that one must use caution in interpreting results obtained with knockout mice. For example, IL-4 is considered to be crucial for the development of Th2 cells and the susceptibility of BALB/c mice to infection with Leishmania major (14). Despite the absence of this critical cytokine, BALB/c IL-4° mice remained susceptible to L. major infection (22). Similarly in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, which is mediated by Th1 cells, immunization of IFN-γ° mice with the dominant autoantigen, myelin basic protein, revealed that IFN-γ was not required for the induction or clinical course of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (9, 31). Clues to the complexity of these mechanisms have come from studies of the host-parasite relationship between mice and gastrointestinal nematode parasites. IL-4 has a central role in host defense and worm expulsion (11). Infection of IL-4° mice with either Heligmosomoides polygyrus or Trichuris muris results in chronic infection and prevents worm expulsion (8, 28). This is not the case, however, with the murine-adapted strain of the gastrointestinal nematode parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis (19). Infection of BALB/c IL-4° mice with N. brasiliensis results in normal immunity and worm expulsion. This has recently been shown to be due to the ability of IL-13 to induce Stat6 activation through the IL-4 receptor α chain, which results in parasite expulsion (29). Thus, the redundancy of cytokines may explain the discrepancies between the present study and those using antibody treatment of mice to modulate arthritis development. Whatever the mechanism, however, it is clear that IL-4 is not required for resistance and IFN-γ is not required for susceptibility to experimental Lyme arthritis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Jennifer Bird and Nancy Reilly for technical assistance and Horst Bluthmann (F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG) and Genentech for supplying the knockout mice.

This work was supported by the NIH (AR 44042) and by the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anguita J, Roth R, Samanta S, Gee R J, Barthold S W, Mamula M, Fikrig E. B7-1 and B7-2 monoclonal antibodies modulate the severity of murine Lyme arthritis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3037–3041. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3037-3041.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthold S W, Beck D S, Hansen G M, Terwilliger G A, Moody K O. Lyme borreliosis in selected strains and ages of laboratory mice. J Infect Dis. 1990;162:133–138. doi: 10.1093/infdis/162.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barthold S W, Sidman C L, Smith A L. Lyme borreliosis in genetically resistant and susceptible mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;47:605–613. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1992.47.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barthold S W, de Souza M, Feng S. Serum-mediated resolution of Lyme arthritis in mice. Lab Investig. 1996;74:57–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barthold S W, Feng S, Bockenstedt L K, Fikrig E, Feen K. Protective and arthritis-resolving activity in serum of mice actively infected with Borrelia burgdorferi. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:S9–S17. doi: 10.1086/516166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown C R, Reiner S L. Clearance of Borrelia burgdorferi may not be required for resistance to experimental Lyme arthritis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:2065–2071. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2065-2071.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown C R, Reiner S L. Activation of natural killer cells in arthritis-susceptible but not arthritis-resistant mouse strains following Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5208–5214. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5208-5214.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Else K J, Finkelman F D, Maliszewski C R, Grencis R K. Cytokine mediated regulation of chronic intestinal helminth infection. J Exp Med. 1994;179:347–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferber I A, Brocke S, Taylor-Edwards C, Ridgway W, Dinisco C, Steinman L, Dalton D, Fathman C G. Mice with a disrupted IFN-γ gene are susceptible to the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) J Immunol. 1996;156:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fikrig E, Barthold S W, Chen M, Chang C-H, Flavell R A. Protective antibodies develop, and murine arthritis regresses in the absence of MHC class II and CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 1997;159:5682–5686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finkelman F D, Shea-Donohue T, Goldhill J, Sullivan C A, Morris S C, Madden K B, Gause W C, Urban J F., Jr Cytokine regulation of host defense against parasite gastrointestinal helminths: lessons from studies with rodent models. Annu Rev Immunol. 1997;15:505–533. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frey A B, Rao T D. Single exposure of mice to Borrelia burgdorferi elicits immunoglobulin G antibodies characteristic of secondary immune response without production of interleukin-4 by immune T cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2596–2603. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.7.2596-2603.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gross D M, Steere A C, Huber B T. T helper 1 response is dominant and localized to the synovial fluid in patients with Lyme arthritis. J Immunol. 1998;160:1022–1028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heinzel F P, Sadick M D, Holaday B J, Coffman R L, Locksley R M. Reciprocal expression of interferon gamma or IL4 during the resolution or progression of murine leishmaniasis: evidence for expansion of distinct helper T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 1989;169:59–72. doi: 10.1084/jem.169.1.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang I, Barthold S W, Persing D H, Bockenstedt L K. T-helper-cell cytokines in the early evolution of murine Lyme arthritis. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3107–3111. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3107-3111.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keane-Myers A, Nickell S P. T cell subset-dependent modulation of immunity to Borrelia burgdorferi in mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:1770–1776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keane-Myers A, Nickell S P. Role of IL-4 and IFN-γ in modulation of immunity to Borrelia burgdorferi in mice. J Immunol. 1995;155:2020–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keane-Myers A, Maliszewski C R, Finkelman F D, Nickell S P. Recombinant IL-4 treatment augments resistance to Borrelia burgdorferi infections in both normal susceptible and antibody-deficient susceptible mice. J Immunol. 1996;156:2488–2494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kopf M, Le Gros G, Bachman M, Lamers M D, Bluthmann H, Kohler G. Disruption of the murine IL-4 gene blocks Th2 cytokine responses. Nature. 1993;362:245–248. doi: 10.1038/362245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ma Y, Seiler K P, Eichwald E J, Weis J H, Teuscher C, Weis J J. Distinct characteristics of resistance to Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis in C57BL/6N mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66:161–168. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.161-168.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matyniak J, Reiner S L. T helper phenotype and genetic susceptibility in experimental Lyme disease. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1251–1254. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Noben-Trauth N, Kropf P, Muller I. Susceptibility to Leishmania major infection in interleukin-4-deficient mice. Science. 1996;271:987–990. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5251.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oksi J, Savolainen J, Pène J, Bousquet J, Laippala P, Viljanen M K. Decreased interleukin-4 and increased gamma interferon production by peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with Lyme borreliosis. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3620–3623. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3620-3623.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rao T D, Fischer A, Frey A B. CD4+ Th2 cells elicited by immunization confer protective immunity to experimental Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;730:364–366. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rao T D, Frey A B. Protective resistance to experimental Borrelia burgdorferi infection of mice by adoptive transfer of a CD4+ T cell clone. Cell Immunol. 1995;162:225–234. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaible U E, Wallich R, Kramer M D, Nerz G, Stehle T, Museteanu C, Simon M M. Protection against Borrelia burgdorferi infection in scid mice is conferred by presensitized spleen cells and partially by B but not T cells alone. Int Immunol. 1994;6:671–681. doi: 10.1093/intimm/6.5.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shanafelt M-C, Kang I, Barthold S W, Bockenstedt L K. Modulation of murine Lyme borreliosis by interruption of the B7/CD28 T-cell costimulatory pathway. Infect Immun. 1998;66:266–271. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.266-271.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urban J F, Jr, Katona I M, Paul W E, Finkelman F D. Interleukin 4 is important in protective immunity to a gastrointestinal nematode infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5513–5517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urban J F, Jr, Noben-Trauth N, Donaldson D D, Madden K B, Morris S C, Collins M, Finkelman F D. IL-13, IL-4Rα, and Stat6 are required for the expulsion of the gastrointestinal nematode parasite Nippostrongylus brasiliensis. Immunity. 1998;8:255–264. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80477-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yssel H, Shanafelt M C, Soderberg C, Schneider P V, Anzola J, Peltz G. Borrelia burgdorferi activates T helper type 1-like T cell subset in Lyme arthritis. J Exp Med. 1991;174:593–601. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zamvil S S, Mitchell D J, Moore A C, Schwarz A J, Stiefel W, Nelson P A, Rothbard J B, Steinman L. T cell specificity for class II (I-A) and the encephalitogenic N-terminal epitope of the autoantigen myelin basic protein. J Immunol. 1987;139:1075–1079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]