Abstract

Background

Blood loss during liver resection is one of the most important factors affecting the peri‐operative outcomes of patients undergoing liver resection.

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of pharmacological interventions to decrease blood loss and to decrease allogeneic blood transfusion requirements in patients undergoing liver resections.

Search methods

We searched The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Science Citation Index Expanded until November 2008 for identifying the randomised trials.

Selection criteria

We included all randomised clinical trials comparing various pharmacological interventions aimed at decreasing blood loss and allogeneic blood transfusion requirements in liver resection. Trials were included irrespective of whether they included major or minor liver resections, normal or cirrhotic livers, vascular occlusion was used or not, and irrespective of the reason for liver resection.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently identified trials for inclusion and independently extracted data. We analysed the data with both the fixed‐effect and the random‐effects models using RevMan Analysis. For each outcome we calculated the risk ratio (RR), mean difference (MD), or standardised mean difference with 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on intention‐to‐treat analysis or available case‐analysis. For dichotomous outcomes with only one trial included under the outcome, we performed the Fisher's exact test.

Main results

Six trials involving 849 patients satisfied the inclusion criteria. Pharmacological interventions included aprotinin, desmopressin, recombinant factor VIIa, antithrombin III, and tranexamic acid. One or two trials could be included under most comparisons. All trials had a high risk of bias. There was no significant difference in the peri‐operative mortality, survival at maximal follow‐up, liver failure, or other peri‐operative morbidity. The risk ratio of requiring allogeneic blood transfusion was significantly lower in the aprotinin and tranexamic acid groups than the respective control groups. Other interventions did not show significant decreases of allogeneic transfusion requirements.

Authors' conclusions

None of the interventions seem to decrease peri‐operative morbidity or offer any long‐term survival benefit. Aprotinin and tranexamic acid show promise in the reduction of blood transfusion requirements in liver resection surgery. However, there is a high risk of type I (erroneously concluding that an intervention is beneficial when it is actually not beneficial) and type II errors (erroneously concluding that an intervention is not beneficial when it is actually beneficial) because of the few trials included, the small sample size in each trial, and the high risk of bias. Further randomised clinical trials with low risk of bias and random errors assessing clinically important outcomes such as peri‐operative mortality are necessary to assess any pharmacological interventions aimed at decreasing blood loss and blood transfusion requirements in liver resections. Trials need to be designed to assess the effect of a combination of different interventions in liver resections.

Keywords: Humans; Hepatectomy; Antithrombin III; Antithrombin III/administration & dosage; Aprotinin; Aprotinin/administration & dosage; Blood Loss, Surgical; Blood Loss, Surgical/prevention & control; Blood Transfusion; Blood Transfusion/statistics & numerical data; Deamino Arginine Vasopressin; Deamino Arginine Vasopressin/administration & dosage; Factor VIIa; Factor VIIa/administration & dosage; Hemostatics; Hemostatics/administration & dosage; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Recombinant Proteins; Recombinant Proteins/administration & dosage; Tranexamic Acid; Tranexamic Acid/administration & dosage

Plain language summary

Aptrotinin and tranexamic acid may show promise in decreasing blood loss and blood transfusion requirements

Blood loss during liver resection (partial removal of liver) is one of the important factors affecting the post‐operative complications of patients. Allogeneic blood transfusion (using blood donated by a different individual) is associated with increased morbidity and lower survival in patients with liver cancer. This systematic review was aimed at determining whether any medical treatment decreased blood loss and decreased allogeneic blood transfusion requirements in patients undergoing liver resections. This systematic review included six trials with 849 patients. All trials had high risk of bias ('systematic error') as well of play of chance ('random error'). The trials included comparison of medicines (such as aprotinin, desmopressin, recombinant factor VIIa, antithrombin III, and tranexamic acid) with controls (no medicines). There was no difference in the death or complications due to surgery or long‐term survival in any of the comparisons. Fewer patients required transfusion of blood donated by others when aprotinin or tranexamic acid were compared to controls not receiving the interventions. The other comparisons did not decrease the transfusion requirements. However, there is a high risk of type I errors (erroneously concluding that an intervention is beneficial when it is actually not beneficial) and type II errors (erroneously concluding that an intervention is not beneficial when it is actually beneficial) because of the few trials included and the small sample size in each trial as well as the inherent risk of bias (systematic errors). Aprotinin and tranexamic acid show promise in the reduction of blood transfusion requirements in liver resections. Further randomised clinical trials with low risk of bias (systematic errors) and low risk of play of chance (random errors) which assess clinically important outcomes (such as death and complications due to operation) are necessary to assess any pharmacological interventions aimed at decreasing blood transfusion and blood transfusion requirements in liver resections. Trials need to be designed to assess the effect of a combination of different interventions in liver resections.

Background

Elective liver resection is performed mainly for benign and malignant liver tumours (Belghiti 1993). The malignant tumours may arise primarily within the liver (hepatocellular carcinoma and cholangiocarcinoma) or may be metastases from malignancies of other organs (Belghiti 1993; Chouker 2004). More than 1000 elective liver resections are performed annually in the United Kingdom alone (HES 2005).

The liver is subdivided into eight Couinaud segments (Strasberg 2000), which can be removed individually or by right hemi‐hepatectomy (Couinaud segments 5‐8), left hemi‐hepatectomy (segments 2‐4), right trisectionectomy (segments 4‐8), or left trisectionectomy (segments 2‐5 and 8 ±1) (Strasberg 2000). Although every liver resection is considered major surgery, only resection of three or more segments is considered a major liver resection (Belghiti 1993).

Blood loss during liver resection is one of the important factors affecting the peri‐operative outcomes of patients (Shimada 1998; Yoshimura 2004; Ibrahim 2006). Blood loss and peri‐operative blood transfusion requirements also affect the long‐term survival after liver resection for cancers (Poon 2001; Gomez 2008). Various methods have been attempted to reduce the blood loss during liver resection. These include cardiopulmonary interventions such as lowering the central venous pressure (Wang 2006), peri‐operative administration of antifibrinolytics (Lentschener 1999; Wu 2006), use of topical haemostatic agents (Frilling 2005), and occlusion of the blood flow to the liver (Gurusamy 2009a).

Allogeneic blood transfusion (transfusion of blood donated by a blood donor) is associated with increased morbidity (Shinozuka 2000) and lower survival in patients with primary liver cancer (Kitagawa 2001) than the autologous blood transfusion (patient's own blood is collected and re‐infused) because of the possible immunosuppressive effect of donor blood (Shinozuka 2000).

We have addressed the role of vascular occlusion in liver resections in a Cochrane review (Gurusamy 2009a), and the role of topical haemostatic agents is being addressed in another Cochrane review (Gurusamy 2009b). We have addressed the role of cardiopulmonary interventions to decrease blood loss in another Cochrane review (Gurusamy 2009c). We did not find any systematic review or meta‐analysis addressing the role of pharmacological interventions in decreasing blood loss or decreasing allogeneic blood transfusion requirements during liver resections.

Objectives

To determine the benefits and harms of pharmacological interventions to decrease blood loss and to decrease allogeneic blood transfusion requirements in patients undergoing liver resections.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all randomised clinical trials irrespective of language, blinding, publication status, or sample size for inclusion.

Quasi‐randomised trials (where the method of allocating participants to a treatment are not strictly random, for example, date of birth, hospital record number, alternation) were not included regarding assessment of benefit, but were to be considered for inclusion regarding assessment of harms. This is because the trials with poor methodological quality, hence high risk of bias, overestimate the beneficial intervention effects (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001; Wood 2008).

Types of participants

Patients undergoing liver resection irrespective of aetiology, of major or minor liver resections, of normal or cirrhotic liver, of method of vascular occlusion, and use of topical haemostatic agents.

Types of interventions

We included any pharmacological intervention aimed at reducing operative blood loss or peri‐operative allogeneic blood transfusion requirements during liver resection compared with no intervention, placebo, or compared with another intervention aimed at reducing blood loss during liver resection or at decreasing allogeneic blood transfusion requirements during liver resections.

Co‐interventions were allowed if carried out equally in the trial groups.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Peri‐operative mortality.

-

Survival.

Proportion survived at 1, 3, and 5 years (in primary liver cancers and in secondary liver cancers).

Mean or median survival in months (in primary liver cancers and in secondary liver cancers).

Hazard ratio for survival.

Liver failure (however defined by authors).

Peri‐operative morbidity (other than mortality and liver failure such as sepsis, cardiovascular complications, respiratory complications, bile leak, wound complications).

-

Transfusion requirements.

-

Whole blood or red cell allogeneic transfusion (ie, transfusion of blood donated by others to the patient).

Number of patients requiring whole blood or red cell allogenic transfusion.

Overall mean number of units or volume of allogenic whole blood or red cell transfused.

Fresh frozen plasma.

Platelets.

-

Secondary outcomes

Operating time.

Hospital stay.

Intensive therapy unit (ITU) stay.

Blood loss (transection blood loss, operative blood loss) and within 24 hours.

Markers of liver function (bilirubin, prothrombin time).

Biochemical markers of liver injury (aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT)).

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register (Gluud 2009), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, EMBASE, and Science Citation Index Expanded (Royle 2003). We have given the search strategies in Appendix 1 with the time span of the searches. We also searched the references of the identified trials to identify further relevant trials.

Data collection and analysis

Trial selection and extraction of data

Two authors (KG and BO or JL), independently of each other, identified the trials for inclusion. We have also listed the excluded studies with the reasons for the exclusion.

Two authors (KG and BO or JL) independently extracted the following data.

Year and language of publication.

Country in which the trial was conducted.

Year of conduct of trial.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Number of major and minor liver resections.

Number of cirrhotic patients.

Method of vascular occlusion.

Use of topical haemostatic agents.

Outcomes (mentioned above).

Methodological quality (described below).

Any unclear or missing information was sought by contacting the authors of the individual trials. If there was any doubt whether the trial reports shared the same participants ‐ completely or partially (by identifying common authors and centres) ‐ the authors of the trials were contacted to clarify whether the trial report had been duplicated.

We resolved any differences in opinion through discussion or arbitration of the third author (BRD).

Assessment of risk of bias

Two authors (KG and BO or JL) assessed the risk of bias of the trials independently, without masking of the trial names. We followed the instructions given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008) and the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Module (Gluud 2009). According to empirical evidence (Schulz 1995; Moher 1998; Kjaergard 2001; Wood 2008), the following risk of bias components were extracted from each trial.

Sequence generation

Low risk of bias (the methods used is either adequate (eg, computer generated random numbers, table of random numbers) or unlikely to introduce confounding).

Uncertain risk of bias ( there is insufficient information to assess whether the method used is likely to introduce confounding).

High risk of bias (the method used (eg, quasi‐randomised trials) is improper and likely to introduce confounding).

Allocation concealment

Low risk of bias (the method used (eg, central allocation) is unlikely to induce bias on the final observed effect).

Uncertain risk of bias (there is insufficient information to assess whether the method used is likely to induce bias on the estimate of effect).

High risk of bias (the method used (eg, open random allocation schedule) is likely to induce bias on the final observed effect).

Blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors

Low risk of bias (blinding was performed adequately, or the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding).

Uncertain risk of bias (there is insufficient information to assess whether the type of blinding used is likely to induce bias on the estimate of effect).

High risk of bias (no blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome or the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding).

Incomplete outcome data

Low risk of bias (the underlying reasons for missingness are unlikely to make treatment effects departure from plausible values, or proper methods have been employed to handle missing data).

Uncertain risk of bias (there is insufficient information to assess whether the missing data mechanism in combination with the method used to handle missing data is likely to induce bias on the estimate of effect).

High risk of bias (the crude estimate of effects (eg, complete case estimate) will clearly be biased due to the underlying reasons for missingness, and the methods used to handle missing data are unsatisfactory).

Selective outcome reporting

Low risk of bias (the trial protocol is available and all of the trial's pre‐specified outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported or similar or all of the primary outcomes in this review have been reported).

Uncertain risk of bias (there is insufficient information to assess whether the magnitude and direction of the observed effect is related to selective outcome reporting).

High risk of bias (not all of the primary outcomes in this review have been reported and not all of the trial's pre‐specified outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported).

Other bias

Baseline imbalance

Low risk of bias (there was no baseline imbalance in important characteristics).

Uncertain risk of bias (the baseline characteristics were not reported).

High risk of bias (there was a baseline imbalance due to chance or due to imbalanced exclusion after randomisation).

Early stopping

Low risk of bias (sample size calculation was reported and the trial was not stopped or the trial was stopped early by a formal stopping rule at a point where the likelihood of observing an extreme intervention effect due to chance was low).

Uncertain risk of bias (sample size calculations were not reported and it is not clear whether the trial was stopped early or not).

High risk of bias (the trial was stopped early due to an informal stopping rule or the trial was stopped early by a formal stopping rule at a point where the likelihood of observing an extreme intervention effect due to chance was high).

Academic bias

Low risk of bias (the author of the trial has not conducted previous trials addressing the same interventions).

Uncertain risk of bias (It is not clear if the author has conducted previous trials addressing the same interventions).

High risk of bias (the author of the trial has conducted previous trials addressing the same interventions).

Source of funding bias

Low risk of bias (the trial's source(s) of funding did not come from any parties that might have conflicting interest (eg, drug manufacturer).

Uncertain risk of bias (the source of funding was not clear).

High risk of bias (the trial was funded by a drug manufacturer).

We considered trials which were classified as low risk of bias in sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data, and selective outcome reporting as trials with low risk of bias.

Statistical methods

We performed the meta‐analyses according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008) and the Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Module (Gluud 2009). We used the software package RevMan 5 (RevMan 2008). For dichotomous variables, we calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI), if there were two or more trials for an outcome. If there was only trial included under the comparison, we performed Fisher's exact test using StatsDirect 2.7; and we have reported the proportion of patients with the outcome in each group and the P value for the comparison between the groups. For continuous variables, we calculated the mean difference (MD) or standardised mean difference (SMD) (for outcomes such as transfusion requirements where the requirements may be reported as units or as volume in millilitres) with 95% confidence interval. For both dichotomous and continuous outcomes including only one trial, a P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. We used a random‐effects model (DerSimonian 1986) and a fixed‐effect model (DeMets 1987) for meta‐analysis in the presence of two or more trials included under the outcomes. In case of discrepancy between the two models, we have reported both results; otherwise we have reported the results of the fixed‐effect model. Heterogeneity was explored by chi‐squared test with significance set at P value 0.10, and the quantity of heterogeneity was measured by I2 (Higgins 2002) set at 30% (Higgins 2008). We have highlighted the primary outcomes where the heterogeneity was more than 30%.

The analysis was performed on an intention‐to‐treat basis (Newell 1992) whenever possible using the good outcome and poor outcome scenarios. Otherwise, we adopted the 'available‐case analysis' (Higgins 2008). We did not impute any data for the post‐randomisation drop‐outs for any of the continuous outcomes. We had planned to perform a sensitivity analysis with and without empirical continuity correction factors, as suggested by Sweeting et al, (Sweeting 2004) using StatsDirect 2.7 in case there were 'zero‐event' trials in statistically significant outcomes. We also reported the results of risk difference if they were different from the results of risk ratio.

Imputation

We imputed the standard deviation from P values according to the instructions given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention (Higgins 2008) and used the median for the meta‐analysis when mean was not available. If it was not possible to calculate the standard deviation from the P value or confidence intervals, we imputed the standard deviation as the highest standard deviation noted for that group under that outcome. If the mean and standard deviation for blood transfusion was given only for patients who required transfusion, we calculated the mean and standard deviation for the entire group by using the methods for combining groups suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention (Higgins 2008). While this decision was made a priori, we have stated this to clarify this.

Subgroup analysis

We intended to perform the following subgroup analyses:

trials with low risk of bias (adequate generation of allocation sequence, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete data outcomes, and selective reporting) compared to trials with high risk of bias (one or more of the five components inadequate or unclear).

major or minor liver resection.

cirrhotic or non‐cirrhotic liver.

different methods of autologous blood transfusion.

As all the trials were of high bias‐risk and few trials were included under each outcome, we were not able to perform any subgroup analysis.

Bias exploration

We planned to use a funnel plot to explore bias (Egger 1997; Macaskill 2001) and to use asymmetry in funnel plot of trial size against treatment effect to assess this bias. We also planned to perform linear regression approach described by Egger 1997 to determine the funnel plot asymmetry. However, we performed neither of these because of the few trials included under each outcome.

Results

Description of studies

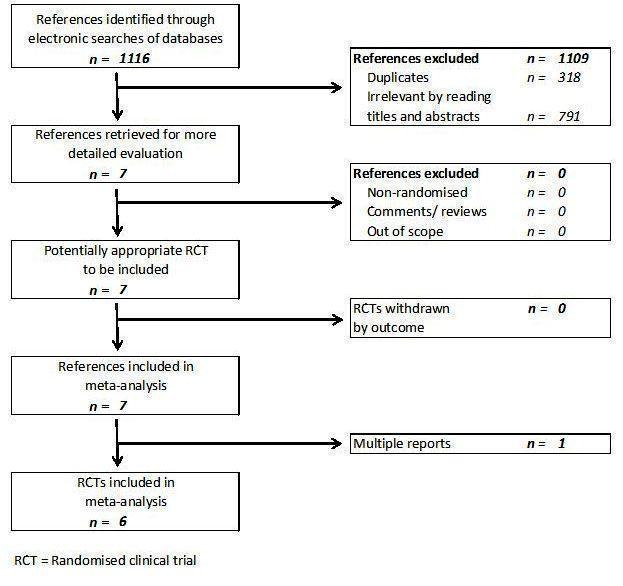

We identified a total of 1116 references through electronic searches of The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials in The Cochrane Library (n = 126), MEDLINE (n = 569), EMBASE (n = 207), and Science Citation Index Expanded (n = 214). We excluded 318 duplicates and 791 clearly irrelevant references through reading abstracts. Seven references were retrieved for further assessment. No reference was identified through scanning reference lists of the identified randomised trials. All the seven retrieved references met the inclusion criteria and so we did not include any reference in the list of excluded studies. In total, six completed randomised trials described in seven publications fulfilled the inclusion criteria and could provide data for the review. Two of the trials had three arms and provided data for three comparisons (Lodge 2005; Shao 2006). The reference flow is shown in Figure 1. Details about the patients, interventions, reasons for post‐randomisation drop‐outs, and the methodological quality of the trials are shown in the table 'Characteristics of included studies'.

1.

Reference flow chart

Aprotinin versus control

A total of 109 patients who underwent elective liver resections were randomised in one trial (Lentschener 1999). Twelve patients were excluded after randomisation. The groups to which these patients belonged to were not stated. The remaining 97 patients belonged to the aprotinin group (n = 48) and placebo group (n = 49). The proportion of females and the mean age of participants in the trials were 46.4% and 53.5 years respectively. The proportion of major liver resections was 64.9%. The proportion of cirrhotic livers was not stated.

Tranexamic acid versus control

A total of 217 patients who underwent elective liver resections were randomised in one trial (Wu 2006) to tranexamic acid (n = 109) and placebo (n = 108). Three patients were excluded as the liver resection was not completed.The proportion of females and the mean age of participants in the trials were 26.6% and 59.5 years respectively. The proportion of major liver resections was 17.8%. The proportion of cirrhotic livers was 51.4%.

Desmopressin versus control

A total of 60 patients who underwent elective liver resections were randomised in one trial (Wong 2003) to desmopressin (n = 30) and placebo (n = 30). The proportion of females and the mean age of participants in the trial were 38.3% and 51.2 years respectively. The proportion of major liver resections was not stated. The proportion of cirrhotic livers was 38.3%.

Recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) versus control

A total of 439 patients were randomised in two trials into high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) rFVIIa, or low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) rFVIIa, or control (Lodge 2005; Shao 2006). There were a total of 33 drop‐outs after randomisation. In one trial (Shao 2006) data of two patients who belonged to the placebo group were lost. The groups to which the remaining 31 drop‐outs belonged was not stated. The remaining 406 patients, who were included for analysis, were randomised to high dose rFVIIa (n = 133 ), low dose rFVIIa (n = 134), or control (n = 139). The proportion of females was 32.0%. The mean age was 53.9 years. The proportion of major liver resections was not stated in either trial. All the patients in one trial had cirrhotic livers (n = 221) (Shao 2006), and all the patients in the second trial had normal livers (n = 185).

Antithrombin III versus control

A total of 24 patients undergoing liver resection were randomised in one trial (Shimada 1994) to antithrombin III (n = 13) versus control (n = 11). The proportion of females and the mean age of participants in the trial were 16.7% and 62.7 years respectively. The proportion of major liver resections was 41.7%. The proportion of cirrhotic livers was 50%.

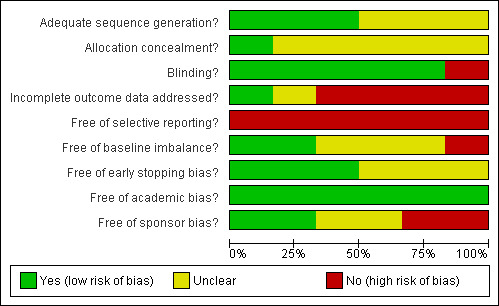

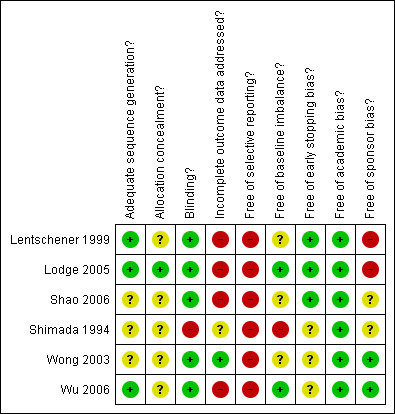

Risk of bias in included studies

The sequence generation was adequate in three (50%) trials (Lentschener 1999; Lodge 2005; Wu 2006). The allocation concealment was adequate in one trials (17.7%) (Lodge 2005). Blinding was adequate in five (83.3%) out of six trials (Lentschener 1999; Wong 2003; Lodge 2005; Shao 2006; Wu 2006). One trial was free from incomplete data outcome bias (17.7%) (Wong 2003). None of the trials were free from selective outcome reporting or from other bias.

All the trials were considered to be of high risk of bias.

The risk of bias is summarised in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

The summary measures used were risk ratio (RR), mean difference (MD), or standardised mean difference (SMD). The 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) are also stated.

Primary outcomes

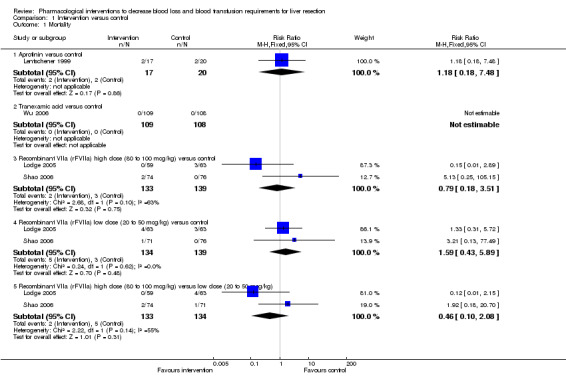

Peri‐operative mortality

There was no significant difference in the peri‐operative mortality in any of the comparisons (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 1 Mortality.

Survival

Only one trial (Lentschener 1999) reported survival data in a sub‐group of patients with colorectal liver metastases. This trial included a comparison of aprotinin and placebo. Even in this trial, the exact number was not stated and survival outcomes could not be included for meta‐analysis. The one‐year survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases was statistically greater in the aprotinin group than the control group. However, the survival advantage was lost at 28 months (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 2 Survival.

| Survival | |

|---|---|

| Study | |

| Aprotinin versus control | |

| Lentschener 1999 | In this trial, survival was reported for patients undergoing liver resection for colorectal liver metastases. The exact number of patients in each group was not stated and survival outcomes could not be included for meta‐analysis. The one‐year survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases was statistically greater in the aprotinin group than the control group. However, the survival advantage was lost at 28 months. |

Liver failure

There was no significant difference in liver failure in the only trial that reported this outcome (7.7% antithrombin III versus 9.1% control; P > 0.99) (Shimada 1994) (Analysis 1.3). None of the remaining trials reported this outcome.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 3 Liver failure.

| Liver failure | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Antithrombin | Control | P value |

| Antithrombin III versus control | |||

| Shimada 1994 | 1/13 (7.7%) | 1/11 (9.1%) | P > 0.9999 |

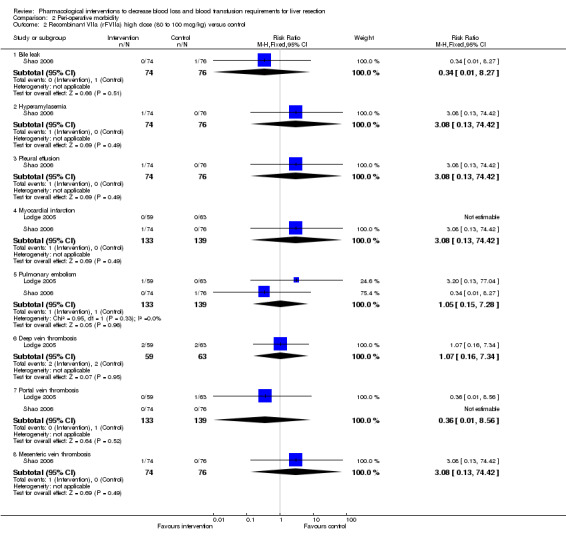

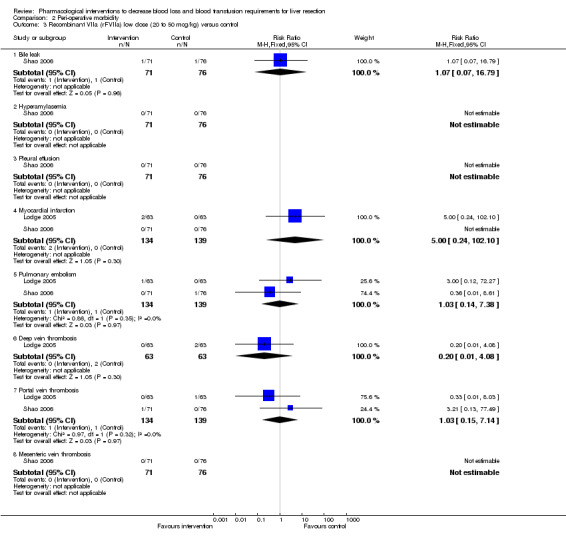

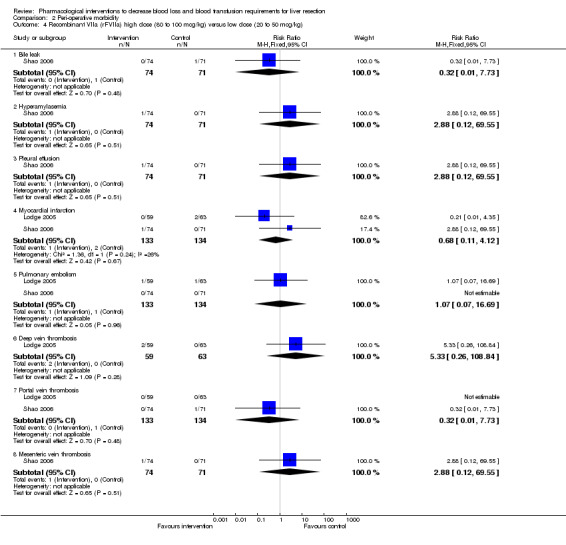

Peri‐operative morbidity

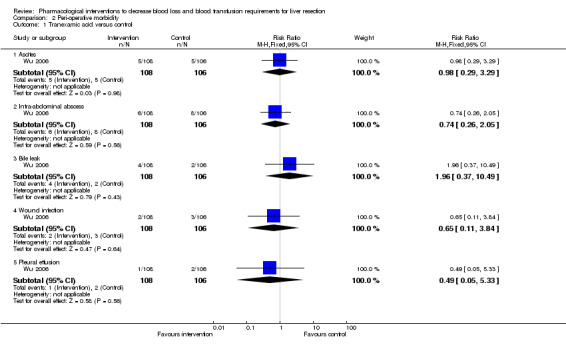

There was no significant difference in the peri‐operative morbidity in any of the comparisons. This was reported in four trials (Shimada 1994; Lodge 2005; Shao 2006; Wu 2006) (Analysis 2.1 to Analysis 2.5).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peri‐operative morbidity, Outcome 1 Tranexamic acid versus control.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peri‐operative morbidity, Outcome 5 Anitithrombin III versus control.

| Anitithrombin III versus control | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Antithrombin | Control | P value |

| Infected intra‐abdominal collection | |||

| Shimada 1994 | 1/13 (7.7%) | 1/11 (9.1%) | P > 0.9999 |

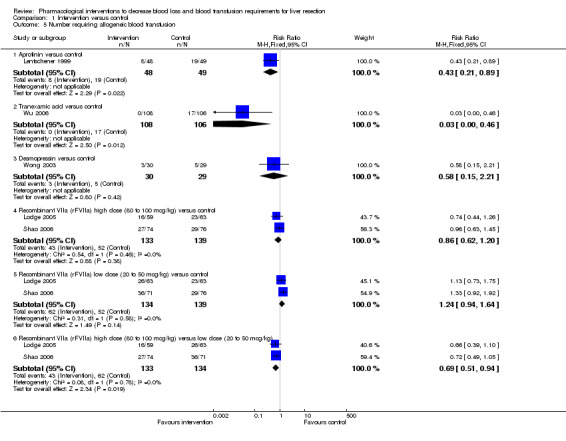

Transfusion requirements

See (Analysis 1.5; Analysis 1.6). None of the trials reported the fresh frozen plasma requirements or platelet transfusion in sufficient detail to be included in this review.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 5 Number requiring allogeneic blood transfusion.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 6 Red cell transfusion.

Aprotinin versus control

One trial was included (Lentschener 1999). The number of patients requiring allogeneic transfusion was significantly lower in the aprotinin group than in the controls (16.7% aprotinin versus 38.8% control; P = 0.0228). The mean red cell transfusion was not reported in this trial.

Tranexamic acid versus control

One trial was included (Wu 2006).The number of patients requiring allogeneic transfusion was significantly lower in the tranexamic acid group than in controls (0% tranexamic acid versus 16% control; P < 0.001). The mean red cell transfusion was not reported in this trial.

Desmopressin versus control

One trial was included (Wong 2003). There was no significant difference in the number of patients requiring blood transfusion (10% desmopressin versus 17.2% control; P = 0.47) or in the mean red cell transfusion (MD ‐0.49 units; 95% CI ‐1.31 to 0.33; P = 0.24) between the groups.

High dose rFVIIa versus low dose rFVIIa versus control

Two trials were included (Lodge 2005; Shao 2006). There was no significant difference in the number of patients requiring allogeneic transfusion (32.3% high dose versus 46.3% low dose versus 37.4% control) or in the amount of red cells transfused between the different groups.

Antithrombin III versus control

One trial was included (Shimada 1998). The number of patients requiring transfusion was not stated in the trial. There was no significant difference in the number of units transfused between the groups (MD 0.40 units; 95% CI ‐3.76 to 4.56; P = 0.85).

Secondary outcomes

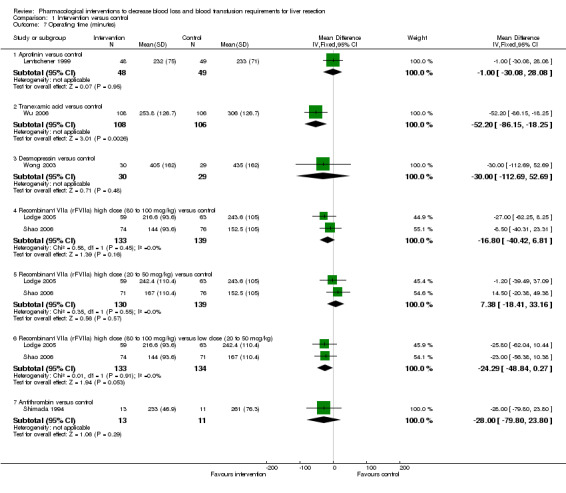

Operating time

The operating time was significantly lower in the intervention group than control in the comparison: tranexamic acid versus placebo (Wu 2006) (MD ‐52.20 minutes; 95% CI ‐86.15 to ‐18.25; P = 0.95). There was no significant difference in the operating time between the intervention and control groups in the remaining comparisons (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 7 Operating time (minutes).

Hospital stay

There was no significant difference in the hospital stay between the intervention and control groups in the comparison: tranexamic acid versus control (Wu 2006). The hospital stay was not reported in the remaining comparisons (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 8 Hospital stay (days).

| Hospital stay (days) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Tranexamic acid Mean (standard deviation) | ControlMean (standard deviation) | P value |

| Tranexamic acid versus control | |||

| Wu 2006 | 8 (7.66) | 9 (7.66) | 0.34 |

Intensive therapy unit (ITU) stay

None of the trials reported ITU stay.

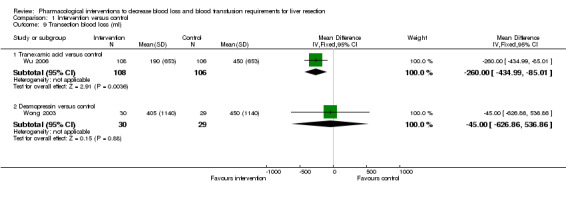

Blood loss

See (Analysis 1.9; Analysis 1.10).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 9 Transection blood loss (ml).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 10 Operative blood loss (ml).

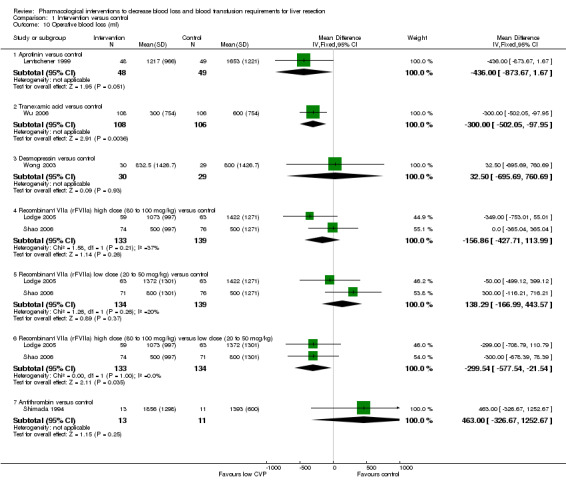

Aprotinin versus control

One trial was included (Lentschener 1999). This trial did not report transection blood loss. There was no statistically significant difference in the operative blood loss between the two groups (MD ‐436.00 ml; 95% CI ‐873.67 to 1.67; P = 0.05).

Tranexamic acid versus control

One trial was included (Wu 2006). The transection blood loss and operating blood loss were lower in the tranexamic acid group than in the placebo group (MD ‐260.00 ml; 95% CI ‐434.99 to ‐85.01; P = 0.004 and MD ‐300.00 ml; 95% CI ‐502.05 to ‐97.95; P = 0.004 respectively).

Desmopressin versus control

One trial was included (Wong 2003). There was no significant difference in the transection blood loss or operative blood loss between the groups (MD ‐45.00 ml; 95% CI ‐621.91 to 531.91; P = 0.88 and MD 32.50 ml; 95% CI ‐689.50 to 754.50; P = 0.93).

High dose rFVIIa versus low dose rFVIIa versus control

Two trials were included (Lodge 2005; Shao 2006). Both trials did not report the transection blood loss. There was no significant difference in the operative blood loss between high dose rFVIIa or low dose rFVIIa and control. However, the operative blood loss was significantly lower in the high dose rFVIIa than low dose rFVIIa (MD ‐299.54 ml; 95% CI ‐577.54 to ‐21.54; P = 0.03).

Antithrombin III versus control

One trial was included (Shimada 1998). This trial did not report the transection blood loss. There was no significant difference in the operative blood loss between the two groups (MD 463.00 ml; 95% CI ‐326.67 to 1252.67; P = 0.25).

Markers of liver function (bilirubin, prothrombin time)

These were reported in two trials (Shimada 1994; Lentschener 1999). There was no significant difference in the markers of liver function in any of the comparisons (Analysis 1.11; Analysis 1.12).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 11 Bilirubin (micromol/litre).

| Bilirubin (micromol/litre) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study |

Antithrombin III Mean (standard deviation) |

Control Mean (standard deviation) |

Mean difference (95% confidence intervals) |

Statistical signficance |

| Antithrombin III versus control | ||||

| Shimada 1994 | 2.1(1.1) | 2.5(1.3) | ‐0.40 (‐1.37 to 0.57) | P = 0.42 |

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 12 Prothrombin activity (percentage of normal activity).

| Prothrombin activity (percentage of normal activity) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study |

Aprotinin Mean (standard deviation) |

Control Mean (standard deviation) |

Mean difference(95% confidence intervals) | Statistical significance |

| Aprotinin versus control | ||||

| Lentschener 1999 | 63(12) | 63(15) | 0 (‐5.4 to 5.4) | P = 1.00 |

Biochemical markers of liver injury (aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT))

These were reported in one trial (Shimada 1994).There was no significant difference in the markers of liver injury (Analysis 1.13; Analysis 1.14).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 13 Aspartate transaminase (international units per litre) (peak).

| Aspartate transaminase (international units per litre) (peak) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study |

Antithrombin III Mean (standard deviation) |

Control Mean (standard deviation) |

Mean difference (95% confidence intervals) |

Statistical significance |

| Antithrombin III versus control | ||||

| Shimada 1994 | 170 (86.5) | 177(63) | ‐7.00 (‐66.98 to 52.98) | P = 0.82 |

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Intervention versus control, Outcome 14 Alanine transminase (international units per litre) (peak).

| Alanine transminase (international units per litre) (peak) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study |

Antithrombin III Mean (standard deviation) |

Control Mean (standard deviation) |

Mean difference (95% confidence intervals) |

Statistical significance |

| Antithrombin III versus control | ||||

| Shimada 1994 | 95 (39.7) | 86 (39.8) | 9.00 (‐22.92 to 40.92) | P = 0.58 |

Variations in statistical analysis

There were no changes in results by adopting the random‐effects model in any of the comparisons with more than one trial. There was no change in results by calculating the risk difference for any of dichotomous outcomes.

Subgroup analysis

We did not perform any subgroup analysis because of the few trials included under each category in this review.

Exploration of bias

We did not perform the funnel plot or the linear regression approach described by Egger 1997 to determine the funnel plot asymmetry because of the few trials included under each outcome.

Discussion

In this review, the safety and efficacy of different pharmacological interventions in reducing blood loss and allogeneic blood transfusion requirements have been evaluated. There was no significant difference in the mortality or morbidity between the intervention groups and controls. However, none of the trials were powered to identify differences in mortality or morbidity. The choice of which morbidity to report and which morbidity not to report varies from one report to another. Thus, it is not possible to make conclusions on the safety of these interventions from these trials. However, most of the pharmacological interventions are already well established regarding their safety.

Aprotinin and tranexamic acid appear to be beneficial in decreasing the number of patients requiring allogeneic blood transfusion. Aprotinin was also associated with a greater one‐year survival than controls. This could be because of the immunosuppressive effects of allogeneic transfusion (Shinozuka 2000) or the role of aprotinin in controlling the plasmin activity involved in tumour cell spread (Lentschener 1999). In both cases, one would expect a beneficial effect on long‐term survival also. In the only trial that was included under this comparison (Lentschener 1999), there was no long‐term difference in the survival between the groups and an alternate explanation has to be sought if the findings are confirmed.

The decreased operating time in the comparison of tranexamic acid with control (Wu 2006) may be due to the quicker haemostasis achieved as the groups were matched for major and minor liver resections in the majority of patients. This may benefit the patient and also decrease the costs.

Most of the trials employed intermittent vascular occlusion. It is not clear whether the beneficial effects of the interventions will be increased or decreased in situations where vascular occlusion is not employed. Furthermore, the effect of a combination of interventions has to be assessed using adequately powered factorial trials.

However, there is a high risk of type I (erroneously concluding that an intervention is beneficial when it is actually not beneficial) and type II errors (erroneously concluding that an intervention is not beneficial when it is actually beneficial) because of the few trials included and the small sample size in each trial. Furthermore, the risks of type I errors are increased due to the many risks of bias (Wood 2008).

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

None of the interventions seem to decrease peri‐operative morbidity or offer any long‐term survival benefit. Aprotinin and tranexamic acid may show promise in the reduction of blood loss and blood transfusion requirements, but they need assessment in further trials.

Implications for research.

Randomised clinical trials with low risk of systematic errors and random errors are necessary to assess these pharmacological interventions in liver resections. Trials need to be designed (factorial design) to assess the effect of a combination of different interventions in liver resections. Trials need to be conducted and reported according to the CONSORT Statement (www.consort‐statement.org) (Moher 2001; Boutron 2008).

Notes

This is one of the two reviews written based on the protocol "Non‐surgical interventions to decrease blood loss and blood transfusion requirements for liver resection" (Gurusamy 2008). This protocol was split into two reviews because of the comments from CHBG editors.

Acknowledgements

To Bujar Osmani, Macedonia, who partially extracted the data for the review. To TC Mahendran, Chennai, India, who was the first author's first surgical teacher. To The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group for the support that they have provided.

Peer Reviewers: Ingmar Königsrainer, Germany; Tahany Awad, Denmark. Contact Editor: Frederic Keus, The Netherlands.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies

| Database | Period of search | Search strategy used |

| The Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group Controlled Trials Register | November 2008. | (Blood loss OR bleeding OR hemorrhage OR haemorrhage OR hemorrhages OR haemorrhages OR hemostasis OR haemostasis OR transfusion) AND (((liver OR hepatic OR hepato) AND (resection OR segmentectomy)) OR hepatectomy) |

| Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in The Cochrane Library | Issue 4, 2008 | #1 Blood loss OR bleeding OR hemorrhage OR haemorrhage OR hemorrhages OR haemorrhages OR hemostasis OR haemostasis OR transfusion #2 MeSH descriptor Hemorrhage explode all trees #3 MeSH descriptor Blood Transfusion explode all trees #4 (#1 OR #2 OR #3) #5 liver OR hepatic OR hepato #6 MeSH descriptor Liver explode all trees #7 (#5 OR #6) #8 resection OR segmentectomy #9 (#7 AND #8) #10 hepatectomy #11 MeSH descriptor Hepatectomy explode all trees #12 (#9 OR #10 OR #11) #13 (#4 AND #12) |

| MEDLINE (Pubmed) | January 1951 to November 2008 | (Blood loss OR bleeding OR hemorrhage OR haemorrhage OR hemorrhages OR haemorrhages OR hemostasis OR haemostasis OR transfusion OR "Hemorrhage"[Mesh] OR "Blood Transfusion"[Mesh]) AND (((liver OR hepatic OR hepato OR "liver"[MeSH]) AND (resection OR segmentectomy)) OR hepatectomy OR "hepatectomy"[MeSH]) AND (((randomized controlled trial [pt] OR controlled clinical trial [pt] OR randomized controlled trials [mh] OR random allocation [mh] OR double‐blind method [mh] OR single‐blind method [mh] OR clinical trial [pt] OR clinical trials [mh] OR ("clinical trial" [tw]) OR ((singl* [tw] OR doubl* [tw] OR trebl* [tw] OR tripl* [tw]) AND (mask* [tw] OR blind* [tw])) OR (placebos [mh] OR placebo* [tw] OR random* [tw] OR research design [mh:noexp]) NOT (animals [mh] NOT human [mh])))) |

| EMBASE (Ovid SP) | January 1980 to November 2008 | 1 exp CROSSOVER PROCEDURE/ 2 exp DOUBLE BLIND PROCEDURE/ 3 exp SINGLE BLIND PROCEDURE/ 4 exp RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL/ 5 (((RANDOM* or FACTORIAL* or CROSSOVER* or CROSS) and OVER*) or PLACEBO* or (DOUBL* and BLIND*) or (SINGL* and BLIND*) or ASSIGN* or ALLOCAT* or VOLUNTEER*).af. 6 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 7 exp BLEEDING/ 8 exp Blood Transfusion/ 9 (Blood loss or bleeding or hemorrhage or haemorrhage or hemorrhages or haemorrhages or hemostasis or haemostasis or transfusion).af. 10 8 or 7 or 9 11 (liver or hepatic or hepato).af. 12 (segmentectomy or resection).af. 13 11 and 12 14 hepatectomy.af. 15 exp Liver Resection/ 16 13 or 15 or 14 17 6 and 16 and 10 |

| Science Citation Index Expanded (http://portal.isiknowledge.com) | January 1970 to November 2008 | #1 TS=(Blood loss OR bleeding OR hemorrhage OR haemorrhage OR hemorrhages OR haemorrhages OR hemostasis OR haemostasis OR transfusion) #2 TS=(((liver OR hepatic OR hepato) AND (resection OR segmentectomy)) OR hepatectomy) #3 TS=(random* OR blind* OR placebo* OR meta‐analysis) #4 #3 AND #2 AND #1 |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Intervention versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mortality | 4 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Aprotinin versus control | 1 | 37 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.18 [0.18, 7.48] |

| 1.2 Tranexamic acid versus control | 1 | 217 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 1.3 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.79 [0.18, 3.51] |

| 1.4 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.59 [0.43, 5.89] |

| 1.5 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) | 2 | 267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.46 [0.10, 2.08] |

| 2 Survival | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 2.1 Aprotinin versus control | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3 Liver failure | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 3.1 Antithrombin III versus control | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4 Peri‐operative morbidity | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 4.1 See analysis 2 | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 5 Number requiring allogeneic blood transfusion | 5 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 Aprotinin versus control | 1 | 97 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.43 [0.21, 0.89] |

| 5.2 Tranexamic acid versus control | 1 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [0.00, 0.46] |

| 5.3 Desmopressin versus control | 1 | 59 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.58 [0.15, 2.21] |

| 5.4 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.86 [0.62, 1.20] |

| 5.5 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.24 [0.94, 1.64] |

| 5.6 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) | 2 | 267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.69 [0.51, 0.94] |

| 6 Red cell transfusion | 4 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 6.1 Desmopressin versus control | 1 | 59 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.31 [‐0.82, 0.21] |

| 6.2 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 272 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.01 [‐0.23, 0.24] |

| 6.3 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 269 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.19 [‐0.05, 0.43] |

| 6.4 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) | 2 | 267 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.19 [‐0.43, 0.05] |

| 6.5 Antithrombin versus control | 1 | 24 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.07 [‐0.73, 0.88] |

| 7 Operating time (minutes) | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 Aprotinin versus control | 1 | 97 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐1.0 [‐30.08, 28.08] |

| 7.2 Tranexamic acid versus control | 1 | 214 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐52.20 [‐86.15, ‐18.25] |

| 7.3 Desmopressin versus control | 1 | 59 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐30.0 [‐112.69, 52.69] |

| 7.4 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 272 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐16.80 [‐40.42, 6.81] |

| 7.5 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 269 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.38 [‐18.41, 33.16] |

| 7.6 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) | 2 | 267 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐24.29 [‐48.84, 0.27] |

| 7.7 Antithrombin versus control | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐28.0 [‐79.80, 23.80] |

| 8 Hospital stay (days) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 8.1 Tranexamic acid versus control | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 9 Transection blood loss (ml) | 2 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 Tranexamic acid versus control | 1 | 214 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐260.0 [‐434.99, ‐85.01] |

| 9.2 Desmopressin versus control | 1 | 59 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐45.0 [‐626.86, 536.86] |

| 10 Operative blood loss (ml) | 6 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 Aprotinin versus control | 1 | 97 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐434.00 [‐873.67, 1.67] |

| 10.2 Tranexamic acid versus control | 1 | 214 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐300.0 [‐502.05, ‐97.95] |

| 10.3 Desmopressin versus control | 1 | 59 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 32.5 [‐695.69, 760.69] |

| 10.4 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 272 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐156.86 [‐427.71, 113.99] |

| 10.5 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | 273 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 138.29 [‐166.99, 443.57] |

| 10.6 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) | 2 | 267 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐299.54 [‐577.54, ‐21.54] |

| 10.7 Antithrombin versus control | 1 | 24 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 463.00 [‐326.67, 1252.67] |

| 11 Bilirubin (micromol/litre) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 11.1 Antithrombin III versus control | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 12 Prothrombin activity (percentage of normal activity) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 12.1 Aprotinin versus control | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 13 Aspartate transaminase (international units per litre) (peak) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 13.1 Antithrombin III versus control | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 14 Alanine transminase (international units per litre) (peak) | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 14.2 Antithrombin III versus control | Other data | No numeric data |

Comparison 2. Peri‐operative morbidity.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Tranexamic acid versus control | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Ascites | 1 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.98 [0.29, 3.29] |

| 1.2 Intra‐abdominal abscess | 1 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.74 [0.26, 2.05] |

| 1.3 Bile leak | 1 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.96 [0.37, 10.49] |

| 1.4 Wound infection | 1 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.65 [0.11, 3.84] |

| 1.5 Pleural effusion | 1 | 214 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.49 [0.05, 5.33] |

| 2 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 Bile leak | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.34 [0.01, 8.27] |

| 2.2 Hyperamylasemia | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.08 [0.13, 74.42] |

| 2.3 Pleural effusion | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.08 [0.13, 74.42] |

| 2.4 Myocardial infarction | 2 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.08 [0.13, 74.42] |

| 2.5 Pulmonary embolism | 2 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.05 [0.15, 7.28] |

| 2.6 Deep vein thrombosis | 1 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.16, 7.34] |

| 2.7 Portal vein thrombosis | 2 | 272 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.01, 8.56] |

| 2.8 Mesenteric vein thrombosis | 1 | 150 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 3.08 [0.13, 74.42] |

| 3 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) versus control | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 Bile leak | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.07, 16.79] |

| 3.2 Hyperamylasemia | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.3 Pleural effusion | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 3.4 Myocardial infarction | 2 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.0 [0.24, 102.10] |

| 3.5 Pulmonary embolism | 2 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.14, 7.38] |

| 3.6 Deep vein thrombosis | 1 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.2 [0.01, 4.08] |

| 3.7 Portal vein thrombosis | 2 | 273 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.03 [0.15, 7.14] |

| 3.8 Mesenteric vein thrombosis | 1 | 147 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.0 [0.0, 0.0] |

| 4 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) | 2 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 Bile leak | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.73] |

| 4.2 Hyperamylasemia | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [0.12, 69.55] |

| 4.3 Pleural effusion | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [0.12, 69.55] |

| 4.4 Myocardial infarction | 2 | 267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.68 [0.11, 4.12] |

| 4.5 Pulmonary embolism | 2 | 267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.07 [0.07, 16.69] |

| 4.6 Deep vein thrombosis | 1 | 122 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 5.33 [0.26, 108.84] |

| 4.7 Portal vein thrombosis | 2 | 267 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.32 [0.01, 7.73] |

| 4.8 Mesenteric vein thrombosis | 1 | 145 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 2.88 [0.12, 69.55] |

| 5 Anitithrombin III versus control | Other data | No numeric data | ||

| 5.1 Infected intra‐abdominal collection | Other data | No numeric data |

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peri‐operative morbidity, Outcome 2 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus control.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peri‐operative morbidity, Outcome 3 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg) versus control.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Peri‐operative morbidity, Outcome 4 Recombinant VIIa (rFVIIa) high dose (80 to 100 mcg/kg) versus low dose (20 to 50 mcg/kg).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Lentschener 1999.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial Sequence generation: adequate. Allocation concealment: unclear. Blinding: adequate. Incomplete outcome data addressed: inadequate. Free of selective reporting: inadequate. Free of other bias: inadequate. |

|

| Participants | Country: France.

Number randomised: 109.

Post‐randomisation drop‐outs: 12 (11%) (see notes).

Mean age: 53.5 years.

Females: 45 (46.4%).

Major liver resections: 63 (64.9%).

Cirrhotic livers: not stated. Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to two groups. Group 1: Aprotinin (n = 48). Group 2: control (n = 49). Further details of intervention: 5 million KIU per hour until skin closure (loading dose of 2 million KIU at induction) Other details: Vascular occlusion: intermittent clamping. Method of parenchymal transection: clamp crush technique. Management of raw surface: absorbable clips. Other co‐interventions to decrease blood loss: none reported. |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures were mortality, survival (one year survival and 28 months survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases), peri‐operative morbidity, transfusion requirements, blood loss and liver function tests. | |

| Notes | 12 patients from both groups (individual groups not stated) in whom tumour could not be removed (n = 6), had wrong operative histological assessment (n = 5), and thoracotomy (n = 1) were excluded from analysis. Attempts to contact the authors in November 2008 were unsuccessful. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: "Adult patients scheduled for elective liver resection performed through abdominal incision were assigned in a double‐blind fashion, by means of a computer‐generated random code ....." |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Adult patients scheduled for elective liver resection performed through abdominal incision were assigned in a double‐blind fashion ....."; "An identical‐appearing placebo was prepared by a nurse not involved in latter assessment." |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Comment: There were 12 post‐randomisation drop‐outs. The reasons for these drop‐outs could be related to the treatment effect. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as liver failure were not reported. |

| Free of baseline imbalance? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Free of early stopping bias? | Low risk | Comment: The trialists recruited the intended number of patients. |

| Free of academic bias? | Low risk | Comment: There were no previously published trials of same comparisons by the author. |

| Free of sponsor bias? | High risk | Quote: "This study was conducted independently of, but partially supported by Assistance Publique‐Hopitaux de Paris, Bayer Pharma France, ....." |

Lodge 2005.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial Sequence generation: adequate. Allocation concealment: adequate. Blinding: adequate. Incomplete outcome data addressed: inadequate. Free of selective reporting: inadequate. Free of other bias: inadequate. |

|

| Participants | Country: France, Germany, Spain, United Kingdom.

Number randomised: 204.

Post‐randomisation drop‐out: 19 (9.3%) (see notes).

Mean age: 56.5 years.

Females: 92 (49.7%).

Major liver resections: not stated.

Cirrhotic livers: 0 (0%). Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to three groups. Group 1: rFVIIa 80 mcg/kg (n = 59). Group 2: rFVIIa 20 mcg/kg (n = 63). Group 3: control (n = 63). Further details of intervention: IV drug 5 minutes before incision and repeated at 5 hours if anticipated operating time > 6 hours. Other details: Vascular occlusion: PTC (in 64.9%). Method of parenchymal transection: not stated. Management of raw surface: not stated. Other co‐interventions to decrease blood loss: none reported. |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures were mortality, transfusion requirements, peri‐operative morbidity, operating time, and blood loss. | |

| Notes | 19 patients from all three groups (individual groups not stated) in whom drug was not administered (n = 4) and in those who did not undergo liver resection after the drug was administered (n = 15) were excluded from analysis. Attempts to contact the authors in November 2008 were unsuccessful. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was computer‐generated and was performed after patient eligibility assessments on the day of surgery by means of a central interactive voice response system set up by Novo Nordisk A/S." |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Quote: "Randomization was computer‐generated and was performed after patient eligibility assessments on the day of surgery by means of a central interactive voice response system set up by Novo Nordisk A/S." |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "To maintain blinding, an equal volume of trial drug per body weight was administered to all patients, irrespective of treatment group allocation." |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Comment: 19 patients were excluded post‐randomisation. This could be related to the treatment effect. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as liver failure were not reported. |

| Free of baseline imbalance? | Low risk | Yes. |

| Free of early stopping bias? | Low risk | Comment: The trialists recruited the intended number of patients. |

| Free of academic bias? | Low risk | Comment: There were no previously published trials of same comparisons by the author. |

| Free of sponsor bias? | High risk | Quote: "The authors thank the patients and the hospital staff participating in the trial, as well as Allan Blemings, M.Sc. (Statistician), and Karsten Soendergaard, M.Sc. (Clinical Researcher), both at Novo Nordisk A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark." |

Shao 2006.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial Sequence generation: unclear. Allocation concealment: unclear. Blinding: adequate. Incomplete outcome data addressed: inadequate. Free of selective reporting: inadequate. Free of other bias: unclear. |

|

| Participants | Country: China, Thailand, Taiwan.

Number randomised: 235

Post‐randomisation drop‐outs: 14 (6%) (see notes).

Mean age: 51.7 years.

Females: 38 (17.2%).

Major liver resections: not stated.

Cirrhotic livers: 235 (100%). Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to three groups. Group 1: rFVIIa 100 mcg/kg (n = 74). Group 2: rFVIIa 50 mcg/kg (n = 71). Group 3: control (n = 76). Further details of intervention: IV drug every 2 hours starting 10 minutes before incision (maximum 4 doses). Other details: Vascular occlusion: not stated. Method of parenchymal transection: not stated. Management of raw surface: not stated. Other co‐interventions to decrease blood loss: none reported. |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures were mortality, transfusion requirements, peri‐operative morbidity, operating time, and blood loss. | |

| Notes | 12 patients from all three groups (individual groups not stated) who did not undergo liver resection (n = 11) and who withdrew consent (n = 1) were excluded from analysis. The data of 2 patients in the placebo group were lost. Thus only 221 patients were included for analysis. Attempts to contact the authors in November 2008 were unsuccessful. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Within 10 minutes before the first skin cut, a bolus dose of rFVIIa 50 or 100 g/kg or placebo was administered intravenously over the course of 2 minutes...." |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Comment: 14 patients were excluded post‐randomisation. This could be related to the treatment effect. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as liver failure were not reported. |

| Free of baseline imbalance? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Free of early stopping bias? | Low risk | Comment: The trialists recruited the intended number of patients. |

| Free of academic bias? | Low risk | Comment: There were no previously published trials of same comparisons by the author. |

| Free of sponsor bias? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

Shimada 1994.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial Sequence generation: unclear. Allocation concealment: unclear. Blinding: inadequate. Incomplete outcome data addressed: unclear. Free of selective reporting: inadequate. Free of other bias: inadequate. |

|

| Participants | Country: Japan.

Number randomised: 24.

Post‐randomisation drop‐outs: not stated.

Mean age: 62.7 years.

Females: 4 (16.7%).

Major liver resections: 10 (41.7%).

Cirrhotic livers: 12 (50%). Inclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to two groups. Group 1: antithrombin (n = 13). Group 2: control (n = 11). Further details of intervention 1500 units IV 3 doses (just before operation, before liver parenchymal transection, and just after operation). Other details: Vascular occlusion: not stated. Method of parenchymal transection: not stated. Management of raw surface: not stated. Other co‐interventions to decrease blood loss: none reported. |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures were liver failure, transfusion requirements, peri‐operative morbidity, operating time, blood loss, and liver function tests. | |

| Notes | Attempts to contact the authors in November 2008 were unsuccessful. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | No. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as mortality were not reported. |

| Free of baseline imbalance? | High risk | Comment: There was statisitically significantly more patients with cirrhosis in the intervention group. |

| Free of early stopping bias? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Free of academic bias? | Low risk | Comment: There were no previously published trials of same comparisons by the author. |

| Free of sponsor bias? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

Wong 2003.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial Sequence generation: unclear. Allocation concealment: unclear. Blinding: adequate. Incomplete outcome data addressed: adequate. Free of selective reporting: inadequate. Free of other bias: unclear. |

|

| Participants | Country: China.

Number randomised: 60.

Post‐randomisation drop‐outs: 0.

Mean age: 51.2 years.

Females: 23 (38.3%).

Major liver resections: not stated.

Cirrhotic livers: 23 (38.3%). Inclusion criteria: Elective liver resection. Exclusion criteria

|

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to two groups. Group 1: desmopressin (n = 30). Group 2: control (n = 30). Further details of intervention: single dose IV desmopressin 0.3 mcg/kg just after induction. Other details: Vascular occlusion: PTC in 17 and 18 patients in the two groups. Method of parenchymal transection: not stated. Management of raw surface: not stated. Other co‐interventions to decrease blood loss: none reported. |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures were transfusion requirements, operating time, and blood loss. | |

| Notes | Attempts to contact the authors in November 2008 were unsuccessful. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Quote: "Patient randomization was by drawing a sealed envelope specifying a prescription for either desmopressin or placebo...." Comment: It is not clear whether the authors used opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Patient randomization was by drawing a sealed envelope specifying a prescription for either desmopressin or placebo, which was then prepared by an independent investigator and blinded to the patient, attending anesthesiologist and surgeon. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: There were no post‐randomisation drop‐outs. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as liver failure were not reported. |

| Free of baseline imbalance? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Free of early stopping bias? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Free of academic bias? | Low risk | Comment: There were no previously published trials of same comparisons by the author. |

| Free of sponsor bias? | Low risk | Quote: "This study was supported by a Hong Kong University CRCG grant (10202115/20013/20100/323/01)." |

Wu 2006.

| Methods | Randomised clinical trial Sequence generation: adequate. Allocation concealment: unclear. Blinding: adequate. Incomplete outcome data addressed: inadequate. Free of selective reporting: inadequate. Free of other bias: unclear. |

|

| Participants | Country: China.

Number randomised: 217.

Post‐randomisation drop‐outs: 3 (1.4%) (see notes).

Mean age: 59.5 years.

Females: 57 (26.6%).

Major liver resections: 38 (17.8%).

Cirrhotic livers: 110 (51.4%). Inclusion criteria: Liver resection for tumours. Exclusion criteria:

|

|

| Interventions | Participants were randomly assigned to two groups. Group 1: tranexamic acid (n = 108). Group 2: control (n = 106). Further details of intervention: 250 mg four times a day for 3 days starting just before operation (first dose = 500 mg). Other details: Vascular occlusion: intermittent PTC or selective intermittent occlusion. Method of parenchymal transection: clamp‐crush method. Management of raw surface: ligatures and sutures. Other co‐interventions to decrease blood loss: none reported. |

|

| Outcomes | The outcome measures were mortality, transfusion requirements, operating time, hospital stay, and blood loss. | |

| Notes | 1 patient from intervention group and 2 patients from control group in whom liver resection was not completed because of presence of peritoneal dissemination or because the tumours were present in both lobes of the liver were excluded from analysis. Authors replied to questions related to methodological quality and mortality in November 2008. |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: "The random sequence was made by random number table." (author replies) |

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear risk | Quote: "The randomization was double‐blinded in a sealed envelope." Comment: It is not clear whether the authors used opaque envelopes. |

| Blinding? All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "...a similar volume of normal saline was used as a placebo at the same time interval as TA injection. Neither surgeons nor medical staffs knew whether patients were enrolled in group A or group B." |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Comment: 3 patients were excluded post‐randomisation. The outcomes could be measured and reported in these patients. But these were not reported. |

| Free of selective reporting? | High risk | Comment: Important outcomes such as liver failure were not reported. |

| Free of baseline imbalance? | Low risk | Yes. |

| Free of early stopping bias? | Unclear risk | Unclear. |

| Free of academic bias? | Low risk | Comment: There were no previously published trials of same comparisons by the author. |

| Free of sponsor bias? | Low risk | Quote: "Supported in part by a grant from National Science Council, Taiwan (No. 92‐2314‐B‐075A‐006)." |

CUSA = cavitron ultrasonic surgical aspirator CVP = central venous pressure MAP = mean arterial pressure PTC = portal triad clamping

Differences between protocol and review

This is one of the two reviews written based on the protocol "Non‐surgical interventions to decrease blood loss and blood transfusion requirements for liver resection". This protocol was split into two reviews because of the comments from CHBG editors.

The outcomes are divided into primary and secondary outcomes.

For dichotomous outcomes with only one trial included under the comparisons, we performed the Fisher's exact test.

Contributions of authors

KS Gurusamy wrote the review and assessed the trials for inclusion and extracted data on included trials. J Li is the co‐author of the review and independently assessed the trials for inclusion and extracted data on included trials. D Sharma and BR Davidson critically commented on the review and provided advice for improving the review.

Sources of support

Internal sources

None, Not specified.

External sources

None, Not specified.

Declarations of interest

None known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

Lentschener 1999 {published data only}

- Lentschener C, Benhamou D, Mercier FJ, Boyer‐Neumann C, Naveau S, Smadja C, et al. Aprotinin reduces blood loss in patients undergoing elective liver resection. Anesthesia and Analgesia 1997;84(4):875‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lentschener C, Li H, Franco D, Mercier FJ, Lu H, Soria J, et al. Intraoperatively‐administered aprotinin and survival after elective liver resection for colorectal cancer metastasis: A preliminary study. Fibrinolysis & Proteolysis 1999;13(1):39‐45. [Google Scholar]

Lodge 2005 {published data only}

- Lodge JP, Jonas S, Oussoultzoglou E, Malago M, Jayr C, Cherqui D, et al. Recombinant coagulation factor VIIa in major liver resection: a randomized, placebo‐controlled, double‐blind clinical trial. Anesthesiology 2005;102(2):269‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shao 2006 {published data only}

- Shao YF, Yang JM, Chau GY, Sirivatanauksorn Y, Zhong SX, Erhardtsen E, et al. Safety and hemostatic effect of recombinant activated factor VII in cirrhotic patients undergoing partial hepatectomy: a multicenter, randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. American Journal of Surgery 2006;191(2):245‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Shimada 1994 {published data only}

- Shimada M, Matsumata T, Kamakura T, Hayashi H, Urata K, Sugimachi K. Modulation of coagulation and fibrinolysis in hepatic resection: a randomized prospective control study using antithrombin III concentrates. Thrombosis Research 1994;74(2):105‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wong 2003 {published data only}

- Wong AY, Irwin MG, Hui TW, Fung SK, Fan ST, Ma ES. Desmopressin does not decrease blood loss and transfusion requirements in patients undergoing hepatectomy. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia 2003;50(1):14‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Wu 2006 {published and unpublished data}

- Wu CC, Ho WM, Cheng SB, Yeh DC, Wen MC, Liu TJ, et al. Perioperative parenteral tranexamic acid in liver tumor resection: a prospective randomized trial toward a "blood transfusion"‐free hepatectomy. Annals of Surgery 2006;243(2):173‐80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Additional references

Belghiti 1993

- Belghiti J, Kabbej M, Sauvanet A, Vilgrain V, Panis Y, Fekete F. Drainage after elective hepatic resection. A randomized trial. Annals of Surgery 1993;218(6):748‐53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Boutron 2008

- Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. Methods and processes of the CONSORT Group: example of an extension for trials assessing nonpharmacologic treatments. Annals of Internal Medicine 2008;148(4):W60‐W66. [PUBMED: 18283201] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Chouker 2004

- Chouker A, Schachtner T, Schauer R, Dugas M, Lohe F, Martignoni A, et al. Effects of Pringle manoeuvre and ischaemic preconditioning on haemodynamic stability in patients undergoing elective hepatectomy: a randomized trial. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2004;93(2):204‐11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DeMets 1987

- DeMets DL. Methods for combining randomized clinical trials: strengths and limitations. Statistics in Medicine 1987;6(3):341‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

DerSimonian 1986

- DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 1986;7(3):177‐88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Egger 1997

- Egger M, Davey SG, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta‐analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.) 1997;315(7109):629‐34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Frilling 2005

- Frilling A, Stavrou GA, Mischinger HJ, Hemptinne B, Rokkjaer M, Klempnauer J, et al. Effectiveness of a new carrier‐bound fibrin sealant versus argon beamer as haemostatic agent during liver resection: a randomised prospective trial. Langenbecks Archives of Surgery 2005;390(2):114‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gluud 2009

- Gluud C, Nikolova D, Klingenberg SL, Whitfield K, Alexakis N, Als‐Nielsen B, et al. Cochrane Hepato‐Biliary Group. About The Cochrane Collaboration (Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs)) 2009, Issue 3. Art. No.: LIVER.

Gomez 2008

- Gomez D, Morris‐Stiff G, Wyatt J, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP, Prasad KR. Surgical technique and systemic inflammation influences long‐term disease‐free survival following hepatic resection for colorectal metastasis. Journal of Surgical Oncology 2008;98(5):371‐6. [PUBMED: 18646038] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gurusamy 2008

- Gurusamy KS, Osmani B, Sharma D, Davidson BR. Non‐surgical interventions to decrease blood loss and blood transfusion requirements for liver resection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007338] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Gurusamy 2009a