Abstract

Background

The use of FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) as a crucial target for kinase inhibitors is well established, but its association with immune infiltration remains unclear. This study aimed to explore the relationship between FLT3 mutations and immune checkpoint molecules (ICMs) in patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

Methods

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases were used to identify the ICMs associated with FLT3 mutations. A Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis, and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) were conducted to analyze the signaling pathways related to the ICMs. The single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA), Cibersort, and estimate algorithms were used to assess immune cell infiltration in AML.

Results

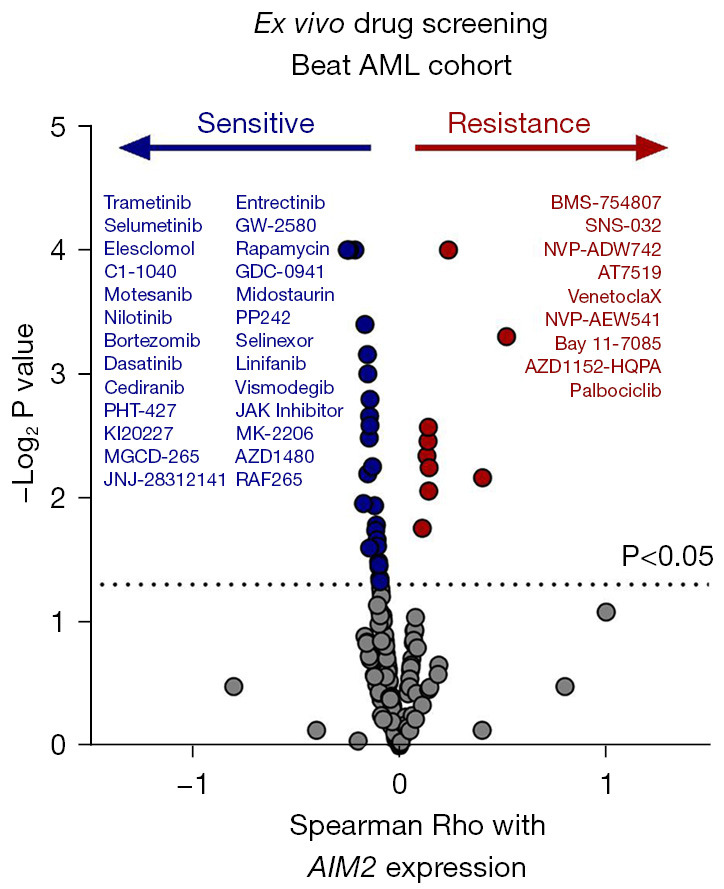

Absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) exhibits elevated expression levels in AML patients harboring FLT3 mutation, contributing significantly to the progress of AML and establishing of an immunosuppressive microenvironment. AIM2 expression significantly correlated with sensitivity of clinically relevant drugs in ex vivo assays of AML. Additionally, AIM2 demonstrates substantial prognostic value and holds promise as a prospective immunotherapeutic target for AML. Our findings indicate a significant correlation between AIM2 and immune infiltration in AML cases, potentially affecting the presence of neutrophils, macrophages, effector memory T cells (Tem), and monocytes. Furthermore, AIM2 is closely linked to various signaling pathways, such as immune cytokine release, immune antigen presentation, and inflammasome signaling, which could play a role in immune cell enrichment in AML.

Conclusions

Our study identified AMI2 as an ICM linked to FLT3 mutations. AMI2 may be involved in the activation of suppressive immune cell populations, such as macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes. AIM2 could serve as a promising immunotherapeutic target for combination therapy with FLT3 inhibitors in AML.

Keywords: Acute myeloid leukemia (AML), FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), immune checkpoint, immune infiltration, absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)

Highlight box.

Key findings

• Our study identified absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) as an immune checkpoint molecule (ICM) linked to FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3) mutations. AMI2 may be involved in the activation of suppressive immune cell populations, such as macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes. AIM2 could serve as a promising immunotherapeutic target for combination therapy with FLT3 inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

What is known, and what is new?

• The mutation results in aberrant activation of the FLT3 signaling pathway, thereby facilitating the proliferation and survival of AML cells. Furthermore, the dysregulated expression of FLT3 may impair the anti-tumor immune response, diminishing the immune system’s capacity to identify and eliminate AML cells.

• AMI2 is an ICM with immunomodulatory properties that plays a role in the immune infiltration of AML. Additionally, AMI2 may be implicated in the stimulation of suppressive immune cell populations, including macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes.

What is the implication, and what should change now?

• The findings of our study indicate that AMI2 may serve as a promising candidate for immunotherapeutic interventions in individuals diagnosed with AML, offering a potential synergistic treatment approach when used in conjunction with FLT3 inhibitors.

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a hematological malignancy with an increasing incidence in childhood as well as adults, and is more frequent in those aged 60 years or more due to its association with the aging process (1,2). In AML, aberrantly differentiated, prolonged myeloid hematopoietic progenitor cells undergo oncogenic transformation and unregulated proliferation, leading to the expansion of immature cells and the subsequent replacement of normal blood constituents by malignant cells (2,3). Therapeutic approaches typically involve the administration of induction chemotherapy to achieve remission, followed by post-remission chemotherapy, with or without stem cell transplantation, to prevent disease relapse (4). Targeted therapies, such as inhibitors targeting isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH)1, IDH2, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 (FLT3), and B-cell lymphoma 2, are frequently used in the management of relapsed/refractory AML (R/RA) (5-7). However, the efficacy of current treatments for AML in improving long-term prognosis, overcoming relapse, and improving drug resistance remains limited. Recent studies have identified various immunotherapeutic approaches, such as antibody-drug conjugates, chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, dendritic cell vaccines, and natural killer cell therapy, which offer promising treatment options for R/RA (8-12).

Various signaling pathways and immune cells play a role in the modification of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and the immune evasion mechanisms in patients with AML (13-15). For example, the upregulation of cluster of differentiation (CD)47 on AML cells hinders the phagocytic capacity of macrophages. Additionally, the inhibition of a receptor called T-cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domain (TIGIT) enhances the anti-CD47-induced phagocytosis of AML cell lines and primary AML cells (16). Moreover, according to the European Leukemia Network guidelines, the presence of FLT3 mutation and heightened occurrences of TIGIT+ M2 leukemia-associated macrophages (LAMs) are correlated with an intermediate or unfavorable risk (16). The in vitro inhibition of TIGIT results in a shift in the polarization of primary LAMs or M2 macrophages derived from peripheral blood toward the M1 phenotype, leading to an increase in the secretion of cytokines and chemokines associated with the M1 phenotype (16). CD70 has the ability to stimulate regulatory T cells (Tregs) via CD27 and secrete immunosuppressive molecules, ultimately resulting in the immune escape in AML (17). Both in vitro and in vivo experiments have shown that anti-CD70 CAR T cells display strong cytotoxicity, cytokine production, proliferation, and significant anti-leukemia activity, resulting in prolonged survival (18,19). These findings indicate that immune checkpoint molecules (ICMs) may serve as promising targets for the development of novel medications and combination treatment strategies for AML.

Absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) has been characterized as a cytoplasmic DNA sensor or a regulatory protein of the inflammasome, and possesses a capable of detecting DNA damage signals resulting from cellular injury and infection by pathogenic microorganisms, thereby contributing significantly to the innate immune response (20,21). AIM2 facilitates the maturation and release of proinflammatory cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β and IL-18, leading to an inflammatory cascade triggering pyroptosis, and altering immune metabolism (20-22). The precise role of AIM2 in tumor progression remains ambiguous; however, research indicates that AIM2 expression is suppressed or hindered in colorectal cancer, which suggests that AIM2 could exert a potential anti-tumor effect and serve as a predictor of tumor immunotherapy efficacy (23-25). AIM2 has been recognized as an immunomodulator that plays a role in regulating the function of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and facilitating tumor rejection in renal carcinoma by mediating M1 macrophage polarization (26). Conversely, in lung adenocarcinoma, AIM2 exhibits increased expression levels that are correlated with unfavorable clinical outcomes and immunosuppressive effects (27,28). Herein, currently, there is a lack of pertinent literature regarding the expression of AIM2, its prognostic implications, and its association with immune infiltration in AML.

As AML is characterized by high genetic heterogeneity, identifying an appropriate immunotherapy target for most of the patients represents challenges. Comprehensive analysis of distinct AML subgroups is essential to identifying suitable targets and facilitating personalized immunotherapy. Our study stratified AML patients into FLT3 mutant and FLT3 non-mutant (wild type) categories to evaluate the differences in AIM2 expression, prognostic significance, associated regulatory pathways, and the correlation between AIM2 and tumor immunity in patients with AML. We present this article in accordance with the REMARK reporting checklist (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-24-1403/rc).

Methods

Activated gene (AG) screening and bioinformatics

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) was used to screen AGs based on a log2(fold change) >1 and a P-adjusted value <0.05. R software (version 4.2.1) with DESeq2 (version 1.36.0) and edgeR (version 3.38.2) were used to analyze the AGs in AML cases with (n=58) or without (n=135) FLT3 mutations as described previously (29,30). The Gene Ontology (GO) analysis, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis, and pathway gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) were conducted using the DAVID online database with the ICMs (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/), and the results were visualized with ggplot2 (version 3.3.6). The GeneCards database (https://www.genecards.org/) provides comprehensive information about immune infiltration-related genes. The expression of ICMs was analyzed with the stats (version 4.2.1) and car (version 3.1-0) software packages. The statistical method was chosen based on the data format characteristics, and the ggplot2 package (version 3.3.6) was used for the data visualization. The RNA-sequencing data from the STAR process of the TCGA-AML project was downloaded from the TCGA database, sorted, and extracted in transcripts per million (TPM) format. A Spearman correlation analysis was performed to assess gene expression, and the results were visualized using ggplot2 (version 3.3.6). The Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/; GSE2191) with GEOquery (version 2.64.2), limma (version 3.52.2), ggplot2 (version 3.3.6), and ComplexHeatmap (version 2.13.1) were used to evaluate AIM2 expression. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Prognostic analysis

The correlation between the expression of six ICMs and overall survival (OS) in AML cases was evaluated using the TCGA database. The survival package (version 3.3.1) was used to test the proportional hazards hypothesis and conduct the survival regression analysis. The outcomes were then visualized using the survminer (version 0.4.9) and ggplot2 (version 3.3.6) packages.

Drug sensitivity prediction

The area under the curve (AUC) values from the 165 drugs tested in ex vivo assays by the BeatAML study (n=520) were used to investigate the correlation between drug response and AIM2 expression (31). The results were visualized using the GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

The association between AIM2 and immune infiltration

The single-sample GSEA (ssGSEA), Cibersort, and estimate algorithms were used to investigate the association between AIM2 and immune infiltration in patients with AML. The ssGSEA algorithm provided by the R package gene set variation analysis (GSVA) (version 1.46.0) was used to calculate immune infiltration based on markers for 24 immune cells as described previously (32,33). The ImmuneScore, ESTIMATEScore, and StromalScore were calculated using the R-estimate package (version 1.0.13). The core algorithm of CIBERSORT (CIBERSORT.R script analysis) was used to calculate immune cell infiltration based on markers of 22 types of immune cells provided by the CIBERSORTx website (https://cibersortx.stanford.edu/). Please refer to the references for more details (34,35).

Statistical analysis

The data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. The statistical analysis was conducted using R software (version 4.2.1) with the stats (version 4.2.1) and car (version 3.1-0) software packages. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare two groups, and the Spearman’s rank analysis was used to assess correlations. Mann-Whitney was also used for measurable factors and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test were employed for categorical factors using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). A P<0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Relationship between FLT3 mutation and tumor immunity

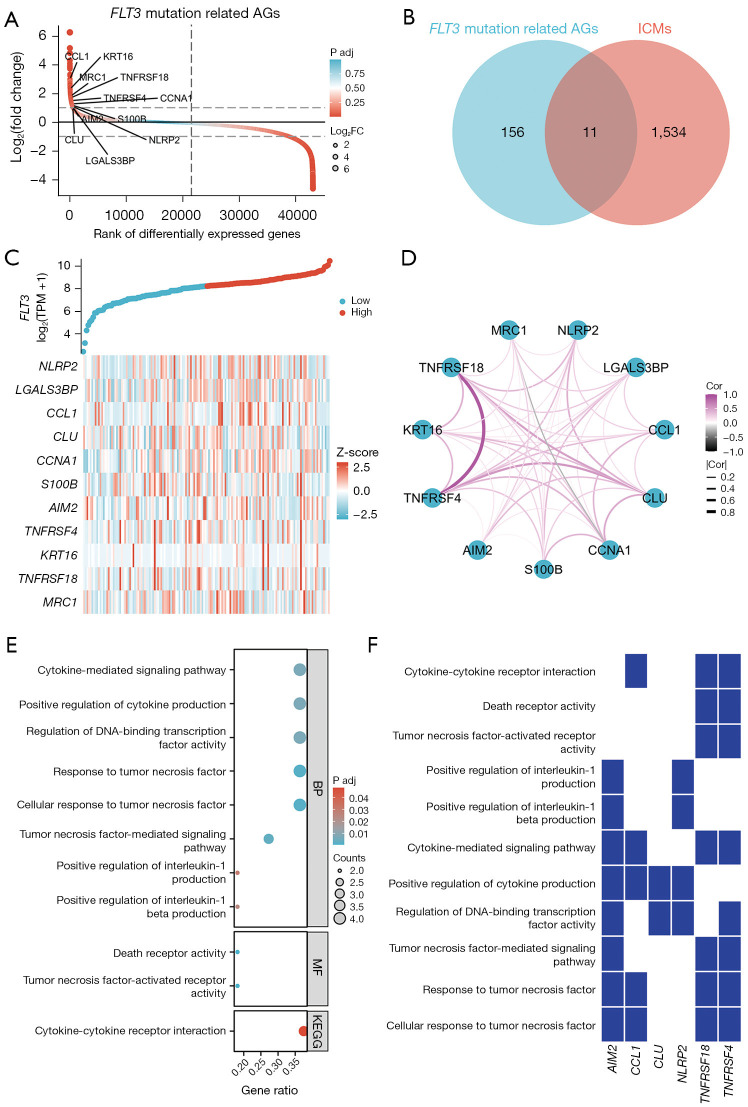

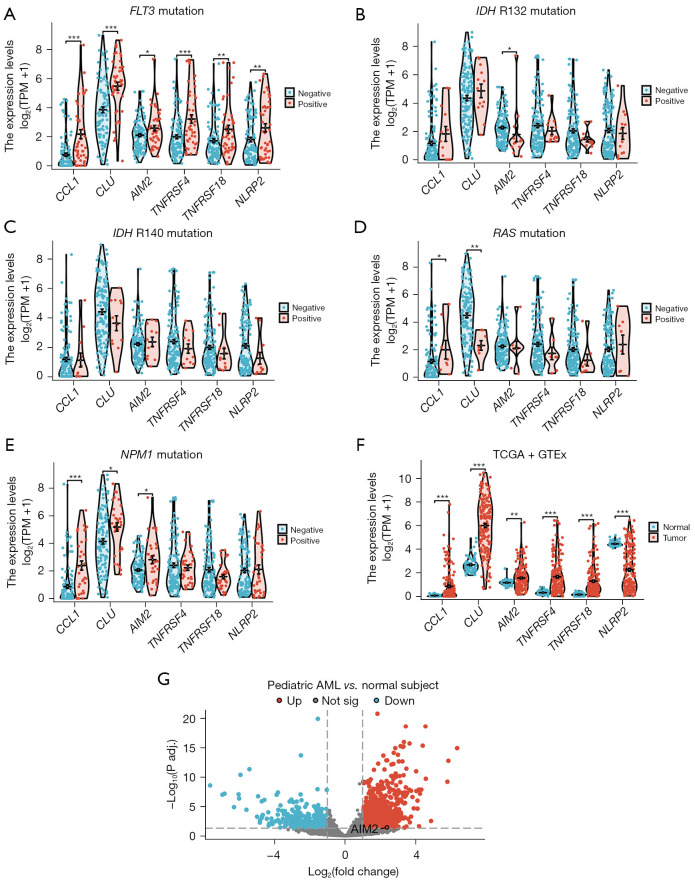

To explore the correlation between FLT3 mutation and tumor immunity in patients with AML, AGs related to FLT3 mutations and the genes associated with tumor immunity were identified using TCGA and GeneCards databases, respectively. The analysis revealed 167 AGs in the FLT3 mutated AML cases compared to those without the mutation (Figure 1A). Additionally, 1,545 ICMs were identified through the GeneCards database. The Venn diagram analysis indicated that 11 ICMs were linked to the FLT3 mutation (Figure 1B). We conducted an additional co-expression analysis to elucidate the relationship between the 11 ICMs and FLT3 mutation (Figure 1C), and explored the correlations among the 11 ICMs (Figure 1D). A significant positive correlation was found among the 11 ICMs, except MRC1 exhibits a negative correlation with CCNA1. An analysis of the biological functions of the ICMs using the GO and KEGG databases demonstrated that cytokine-related signaling pathways had a significant effect on AML patients with the FLT3 mutation (Figure 1E). Among these ICMs, six genes (AIM2, CCL1, CLU, NLRP2, TNFRSF18, and TNFRSF4) were identified as key regulators of cytokine-related signaling pathways (Figure 1F). Despite the known association between these six ICMs and FLT3 mutations (Figure 2A), their relationship with other mutated genes remains unclear. Moreover, our study disclosed that these six ICMs were not strongly correlated with the known frequent mutations associated with AML occurrence, namely the IDH R132 mutation (Figure 2B), IDH R140 mutation (Figure 2C), RAS mutation (Figure 2D), and NPM1 mutation (Figure 2E). Using TCGA and Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) databases (https://gtexportal.org/home/), we confirmed the expression levels of these six ICMs in both normal populations and AML patients. Our findings indicated that other than NLRP2, which was significantly downregulated, the rest five ICMs (AIM2, CCL1, CLU, TNFRSF18, and TNFRSF4) were significantly upregulated in the patients with AML compared to the normal healthy controls (Figure 2F). Subsequent analyses using the GEO database (GSE2191) revealed that AIM2 was significantly upregulated in the mononuclear cells obtained from the peripheral blood or bone marrow of pediatric AML cases (n=54) compared to the normal healthy pediatric controls (n=4) (Figure 2G).

Figure 1.

The relationship between FLT3 mutation and tumor immunity. FLT3 mutation-related AGs in AML were selected using data from TCGA database, including 135 FLT non-mutated and 58 FLT-mutated samples (A). Venn diagram representing the 11 ICMs related to FLT3 mutation in AML (B). Co-expression analysis of the relationship between 11 ICMs and FLT3 mutation (C), and the correlation among the 11 ICMs (D). Analysis of the biological functions of ICMs using the GO and KEGG databases (E). Heatmap showing six ICMs (AIM2, CCL1, CLU, NLRP2, TNFRSF18, and TNFRSF4) as key regulators in this biological process (F). FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; AG, activated gene; FC, fold change; ICM, immune checkpoint molecule; TPM, transcripts per million; BP, biological progress; MF, molecular function; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GO, Gene Ontology.

Figure 2.

The correlation between six ICMs and the gene mutation in AML. The relationship between the expression of the six ICMs and the FLT3 mutation (A), IDH R132 mutation (B), IDH R140 mutation (C), RAS mutation (D), and NPM1 mutation (E) was analyzed using TCGA database. The expression of the six ICMs was also investigated in TCGA and GTEx databases (F). The GEO database (GSE2191) was used to detect AIM2 in pediatric AML and normal subjects (G). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; TPM, transcripts per million; IDH, isocitrate dehydrogenase; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; ICM, immune checkpoint molecule; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; AIM2, absent in melanoma 2.

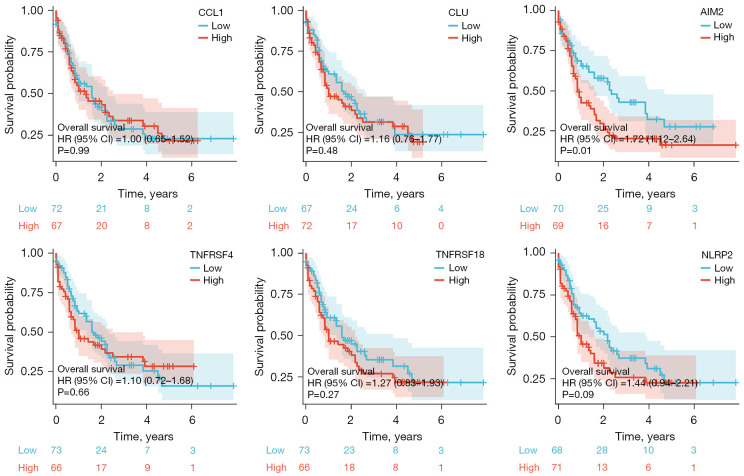

The association between the six ICMs and prognosis of patients with AML

Five of the six assessed ICMs, including CCL1, CLU, TNFRSF18, NLRP2, and TNFRSF4, were found to have no significant association with the outcome of patients with AML. Interestingly, patients with low AIM2 expression exhibited a significantly longer OS than those with high AIM2 expression. Patients with high AIM2 expression had a median survival of 10.2 months, while those with low AIM2 expression had a median survival of 28.5 months (Figure 3). In the TCGA AML cohort, high expression of AIM2 was associated with a lower proportion of AML patients with good molecular risk and a higher prevalence in the intermediate and poor risk groups (Table 1, P=0.009).

Figure 3.

The association between the six ICMs and the prognosis of AML patients. The correlation between the expression of six ICMs and the OS of AML patients was evaluated using TCGA database. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; ICM, immune checkpoint molecule; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; OS, overall survival; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas.

Table 1. Association of AIM2 expression with clinical and molecular factors in TCGA AML cohort.

| Clinicopathological factors† | N | AIM2 | P value§ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low‡ | High‡ | |||

| Total | 173 | 86 (49.7) | 87 (50.3) | |

| Age (years) | 0.09 | |||

| <60 | 91 | 51 (59.3) | 40 (46.0) | |

| ≥60 | 82 | 35 (40.7) | 47 (54.0) | |

| Age (years) | 58 [18–88] | 55 [18–81] | 61 [23–88] | 0.06 |

| Bone marrow blasts (%) | 72 [30–100] | 74 [35–100] | 72 [30–100] | 0.13 |

| White blood cell count (×109/L) | 17 [0.4–297.4] | 15.3 [0.5–297] | 19.6 [0.4–137] | 0.83 |

| Gender | 0.46 | |||

| Male | 92 | 43 (50.0) | 49 (56.3) | |

| Female | 81 | 43 (50.0) | 38 (43.7) | |

| Molecular risk¶ | n=84 | n=86 | 0.009 | |

| Good | 33 | 23 (27.4) | 10 (11.6) | |

| Intermediate | 95 | 38 (45.2) | 57 (66.3) | |

| Poor | 42 | 23 (27.4) | 19 (22.1) | |

Data are presented as n (%) or median [range]. †, the clinical and laboratorial data of TCGA AML cohort were obtained from cBioPortal for Cancer Genomics (http://www.cbioportal.org). ‡, gene expression values were dichotomized by median. §, for statistical analyzes, Mann-Whitney test was used for measured factors, and Fisher’s exact test or Chi-squared test was used for categorical factors. ¶, molecular risk was stratified according TCGA study; 3 AML patients were not classified. AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

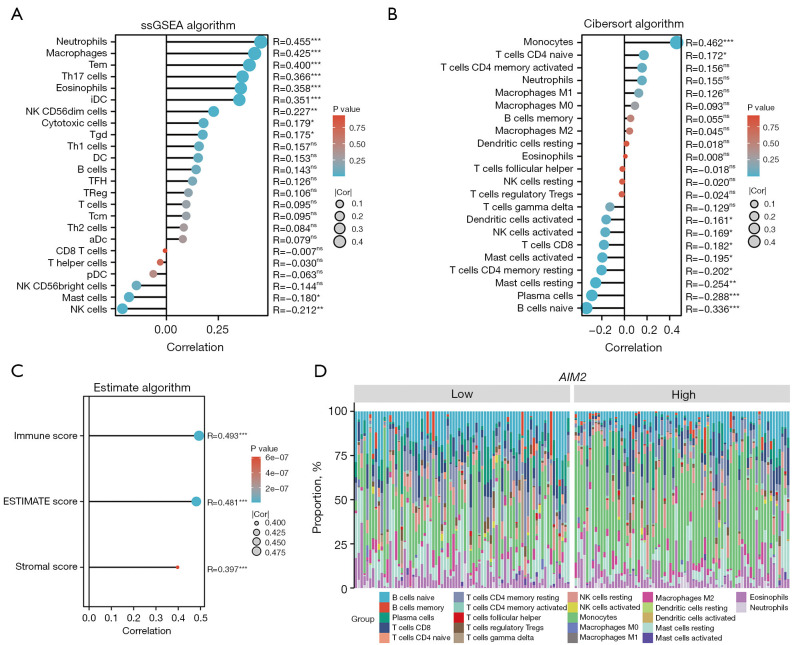

The association between AIM2 and immune infiltration

Given the correlation between AIM2 and the FLT3 mutation, as well as the association between AIM2 and an unfavorable prognosis in AML patients, our study sought to investigate the connection between AIM2 and immune infiltration. Using the ssGSEA algorithm (Figure 4A), we observed a significant positive correlation between AIM2 expression and the presence of neutrophils, macrophages, and transverse electromagnetic (TEM) cells in the TME of AML patients. However, our analysis utilizing the ssGSEA algorithm to determine immune cell enrichment scores revealed no significant correlation between OS and the enrichment scores of neutrophils (Figure S1A), macrophages (Figure S1B), effector memory T cells (Tem) (Figure S1C), or Th17 cells (Figure S1D) in AML patients. Additionally, the Cibersort algorithm results revealed a high abundance of monocyte infiltration in the TME (Figure 4B). The findings of the estimate algorithm indicated a significant positive correlation between AIM2 expression and each of the following: ImmuneScore (r=0.493, P<0.001), ESTIMATEScore (r=0.481, P<0.001), and StromalScore (r=0.397, P<0.001) (Figure 4C). The ImmuneScore evaluates the robustness of the immune response by analyzing the concentration and spatial distribution of immune cells within tumor tissue. A high ImmuneScore typically signifies increased immune cell infiltration in the vicinity of the tumor (32). Conversely, the ESTIMATEScore is a computational approach that estimates the relative proportions of tumor tissue components and immune cells based on gene expression data. The ESTIMATEScore facilitates the assessment of the overall composition of the TME, encompassing both stromal and immune cell populations, thereby aiding in the prediction of tumor progression and patient prognosis (32). The StromalScore is an evaluative metric that quantifies the composition of the tumor tissue’s stroma, typically comprising connective tissue cells and the extracellular matrix. An elevated StromalScore may suggest an increased presence of stromal components surrounding the tumor, potentially influencing tumor growth, invasion, and therapeutic response (32). A subsequent analysis using the Cibersort algorithm revealed that AML cases with elevated AIM2 expression had a higher abundance of monocytes in their TMEs compared to those with low AIM2 expression (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

The association between AIM2 and immune infiltration. The ssGSEA (A), Cibersort (B), and estimate (C) algorithms were used to investigate the association between AIM2 and immune infiltration in AML patients. A subsequent analysis using the Cibersort algorithm revealed that the abundance of monocytes was higher in the AML patients with high AIM2 expression than those with low AIM2 expression (D). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001; ns, not significant. ssGSEA, single-sample gene set enrichment analysis; Tem, effector memory T cells; Th, T helper; iDC, immature dendritic cell; NK, natural killer; Tgd, gamma-delta T cells; DC, dendritic cell; TFH, T follicular helper; TReg, regulatory T cell; Tcm, central memory T cell; aDC, activated dendritic cell; pDC, plasmacytoid dendritic cell; AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

AIM2 expression correlates with ex vivo drug sensitivity in AML

We investigated whether AIM2 messenger RNA (mRNA) levels could influence the response to antineoplastic agents in AML models. In the BeatAML study, we observed that transcriptional levels of AIM2 showed significant positive correlations with eight drugs (BMS-754807, SNS-032, NVP-ADW742, AT7519, venetoclax, NVP-AEW541, Bay 11-7085, AZD1152-HQPA, and palbociclib; all P<0.05) and a significant negative correlation with 26 (trametinib, selumetinib, elesclomol, CI-1040, motesanib, nilotinib, bortezomib, dasatinib, cediranib, PHT-427, KI20227, MGCD-265, JNJ-28312141, entrectinib, GW-2580, rapamycin, GDC-0941, midostaurin, PP242, selinexor, linifanib, vismodegib, JAK inhibitor I, MK-2206, AZD1480, and RAF265, P<0.05) in assays using primary cells from AML patients (Figure 5). Among the correlations found, it is highlighted that AIM2 expression is associated with relevant drugs associated with leukemia therapy, such as sensitivity to several tyrosine kinase inhibitors in clinical use (i.e., nilotinib, dasatinib, midostaurin) and resistance to venetoclax.

Figure 5.

Association between AIM2 expression and drug sensitivity in ex vivo assays in AML. Drug sensitivity according to AIM2 expression in ex vivo assays. Drugs with P<0.05, as determined by the Spearman correlation test, are indicated. AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

AIM2 is correlated with the biomarkers of neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes in AML

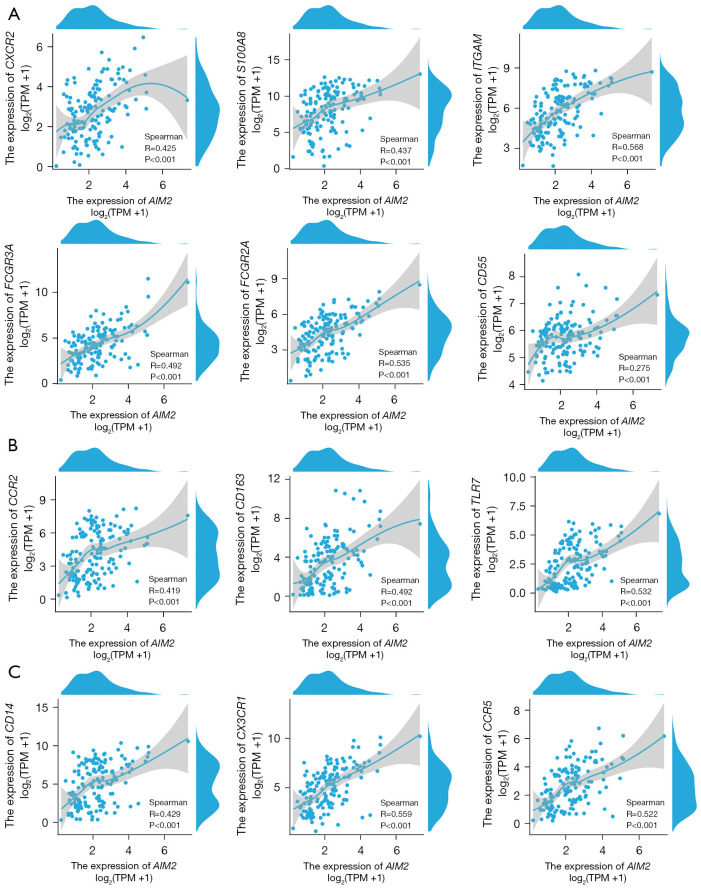

Our earlier data indicated the significant relationship between AIM2 and immune cell enrichment in AML. To further explore this association, the correlation between AIM2 and the markers of neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes was assessed using data from TCGA database. Our results showed a significant correlation between AIM2 expression and neutrophil biomarkers CXCR2 (r=0.425, P<0.001), S100A8 (r=0.437, P<0.001), ITGAM (r=0.568, P<0.001), FCGR3A (r=0.492, P<0.001), FCGR2A (r=0.535, P<0.001), and CD55 (r=0.275, P<0.001) (Figure 6A). Moreover, the expression of AIM2 was found to be substantially associated with macrophage biomarkers CCR2 (r=0.419, P<0.001), CD163 (r=0.492, P<0.001), and TLR7 (r=0.532, P<0.001) (Figure 6B). Additionally, AIM2 expression was found to be significantly correlated with monocyte biomarkers CD14 (r=0.429, P<0.001), CX3CR1 (r=0.559, P<0.001), and CCR5 (r=0.522, P<0.001) (Figure 6C). The markers commonly utilized to identify neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes are referenced in previous studies (36,37).

Figure 6.

AIM2 was found to be correlated with the biomarkers of neutrophils (A), macrophages (B), and monocytes (C) in AML. TPM, transcripts per million; AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

Correlation between AIM2 and popular ICMs in AML

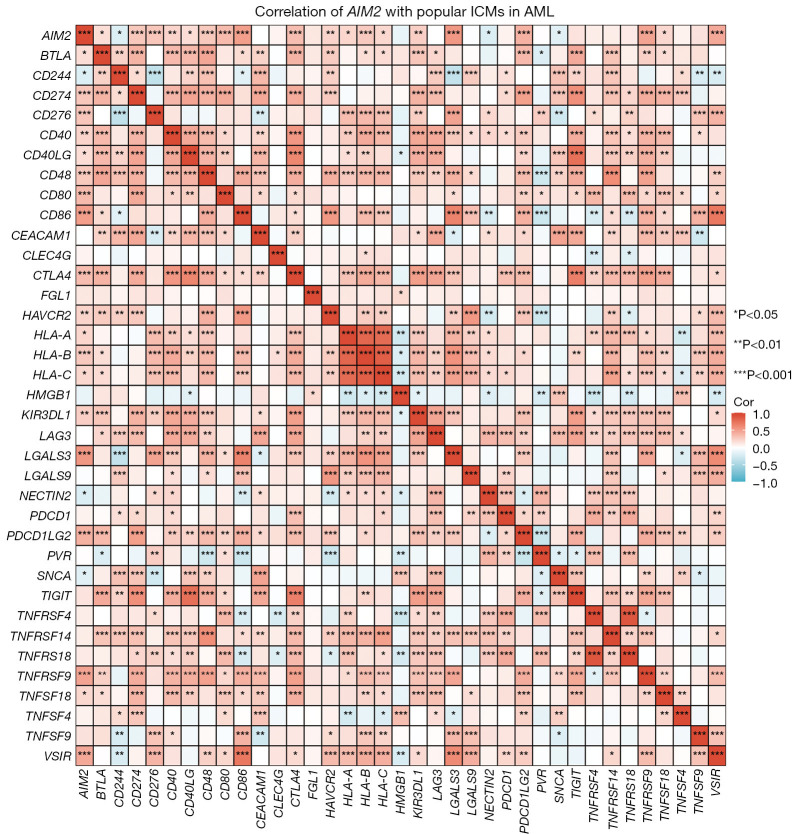

The relationship between AIM2 and 36 prevalent ICMs in AML is currently under investigation to validate the association between AIM2 and immune cell enrichment. As Figure 7 shows, a positive correlation was found between AIM2 and the majority of ICMs, notably including CD80 (r=0.351, P<0.001), CD86 (r=0.499, P<0.001), LGALS3 (r=0.534, P<0.001), PDCD1LG2 (r=0.397, P<0.001), TNFRSF9 (r=0.474, P<0.001), and VSIR (r=0.446, P<0.001). These data show a clear correlation between the AIM2 and ICMs prevalent in AMLs. Prevalent ICMs were selected according to previous studies (38,39).

Figure 7.

Correlation between AIM2 and popular ICMs in AML. The relationship between AIM2 and 36 prevalent ICMs in AML is currently under investigation to validate the association between AIM2 and immune cell enrichment. AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; ICM, immune checkpoint molecule; AML, acute myeloid leukemia.

AIM2-related immune regulatory signaling pathway

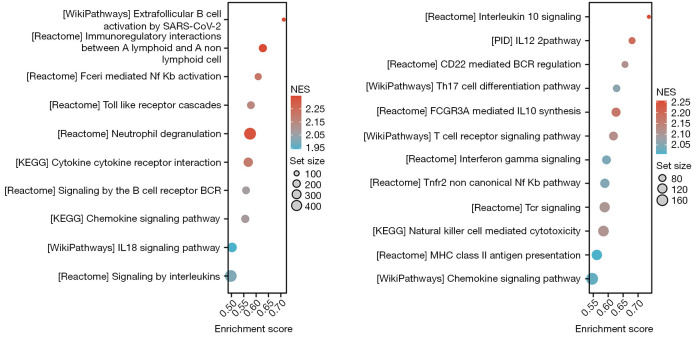

To further investigate the molecular signaling pathways associated with AIM2-mediated immune infiltration in AML, we first conducted a screening of AIM2-related differentially expressed genes using the TCGA database, and then conducted a GSEA to investigate signal pathway enrichment. Figure 8 shows a compilation of the top 22 molecular signaling pathways potentially linked to AIM2-mediated immune infiltration in AML. These pathways predominantly included extrafollicular B-cell activation by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), immunoregulatory interactions between a lymphoid and a non-lymphoid cell, FCERI-mediated nuclear factor (NF)-kappa B activation, toll-like receptor cascades, neutrophil degranulation, cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions, signaling by B-cell receptors (BCRs), the chemokine signaling pathway, the IL-18 signaling pathway, signaling by ILs, IL-10 signaling, the IL-12 pathway, CD22 mediated BCR regulation, T-helper (Th)17 cell differentiation, FCGR3A-mediated IL-10 synthesis, interferon gamma signaling, the TNFR2 non-canonical NF-kappa B pathway, T-cell receptor (TCR) signaling, natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II antigen presentation, and the chemokine signaling pathway. These findings indicate that the immune infiltration mediated by AIM2 is primarily associated with the release of immune cytokines and the presentation of immune antigens.

Figure 8.

AIM2-related immune regulatory signaling pathway. To enhance understandings of the molecular signaling pathways associated with AIM2-mediated immune infiltration in AML, we first screened AIM2-related differentially expressed genes using the TCGA database, and then conducted a GSEA to investigate signal pathway enrichment. SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; NF, nuclear factor; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; BCR, B-cell receptor; IL, interleukin; NES, normalized effect size; PID, primary immunodeficiency; Th, T helper; MHC, major histocompatibility complex; AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis.

AIM2-related canonical inflammasomes signaling pathway

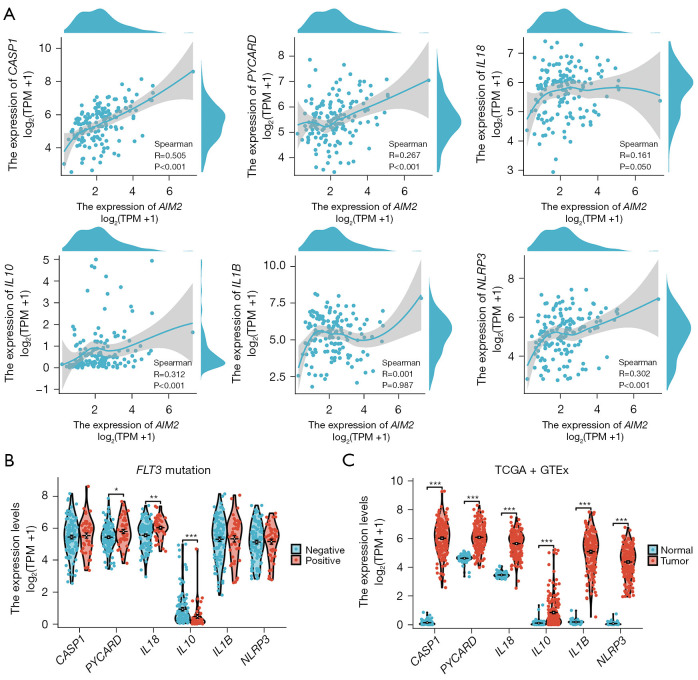

AIM2 has the ability to identify both endogenous and exogenous double-stranded DNA, leading to the formation of an inflammasome protein polymer. This complex serves as a crucial component in the activation of inflammatory caspase 1 (CASP1) through the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns and injury-associated molecular patterns. The inflammasome facilitates cytokine maturation, secretion, and cell pyroptosis, and thus plays a significant role in innate immunity (22). We also explored the correlation between the AIM2-related canonical inflammasome signaling pathway and FLT3 mutations in patients with AML. We found a significant positive correlation between AIM2 and key inflammasome components, including CASP1 (r=0.505, P<0.001), a N-terminal PYRIN-PAAD-DAPIN domain (PYD) and a C-terminal caspase-recruitment domain containing (PYCARD) (r=0.267, P<0.001), IL-10 (r=0.312, P<0.001), and NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) (r=0.302, P<0.001) (Figure 9A). While no direct association was found between any of CASP1, IL-1β, or NLRP3, and FLT3 mutation status (Figure 9B). Our data demonstrated that such components, including CASP1, PYCARD, IL-1β, IL-10, IL-18, and NLRP3, were significantly upregulated in patients with AML compared to healthy individuals (Figure 9C).

Figure 9.

AIM2-related canonical inflammasomes signaling pathway. A significant positive correlation was found between AIM2 and key inflammasome components, including CASP1, PYCARD, IL-18, IL-10, IL-1B, and NLRP3 (A). The association between key inflammasome components and FLT3 mutation status in AML (B). The expression of key inflammasome components was also investigated in TCGA and GTEx databases (C). *, P<0.05; **, P<0.01; ***, P<0.001. TPM, transcripts per million; AIM2, absent in melanoma 2; AML, acute myeloid leukemia; FLT3, FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; GTEx, Genotype-Tissue Expression; CASP1, caspase 1; PYCARD, a N-terminal PYRIN-PAAD-DAPIN domain) and a C-terminal caspase-recruitment domain containing; IL-18, interleukin-18; IL-10, interleukin-10; IL-1B, interleukin-1β; NLRP3, NOD-, LRR-, and pyrin domain-containing protein 3.

Discussion

Currently, AIM2 exhibits elevated expression levels in AML cases harboring FLT3 mutations, contributing significantly to the advancement of AML and the establishment of an immunosuppressive microenvironment. Additionally, AIM2 has substantial prognostic value and holds promise as a prospective immunotherapeutic target for AML. Our findings revealed a significant correlation between AIM2 and immune infiltration in AML cases, potentially affecting the number of neutrophils, macrophages, TEM cells, and monocytes in TME. Furthermore, AIM2 is closely linked to various signaling pathways, such as immune cytokine release, immune antigen presentation, and inflammasome signaling, which could play a role in immune cell enrichment in AML. These results suggest that AIM2 could serve as a promising immunotherapeutic target for combination therapy in AML.

FLT3 is expressed in the hematopoietic stem cells and progenitor cells of myeloid and lymphoid lineages. Mutations in FLT3 lead to the activation of signaling pathways that upregulate anti-apoptotic proteins, promoting the survival of AML stem cells by evading apoptosis. Patients with FLT3 mutations exhibit a higher incidence of hyperleukemia, increased rates of relapse, resistance to treatment, and poorer prognosis than those with wild-type FLT3. The effective clinical management of these patients presents a significant challenge (40). Recent research has demonstrated that FLT3 is significantly implicated in the compromised immune response observed in patients with the FLT3 mutation being linked to aberrant T-cell phenotypes (41). In individuals with FLT3 mutation-associated AML, the administration of multi-kinase inhibitors has been shown to enhance immune surveillance of leukemia by increasing the presence of PD-1 expressing CD8+ lymphocytes in the bone marrow (42). The present investigation revealed that AIM2 activation occurs in patients with the FLT3 mutated AML, resulting in the enrichment of neutrophils, macrophages, TEM cells, and monocytes, and the subsequent activation of various inflammatory signaling pathways, BCRs, and TCRs. These pathways may be implicated in immune evasion mechanisms.

Various types of immune cells play a crucial role in the TME and are associated with the prognosis, metastasis, and response to immunotherapy in cancer (43,44). For instance, TAMs promote the development and advancement of malignant tumors through the secretion of proinflammatory cytokines and the stimulation of cancer stem cell proliferation (45). In hematological malignancies, the use of bispecific antibodies targeting macrophages, specifically the anti-CD47/signal regulatory protein α axis (SIRPα) and anti-SIRPα/CLDN18.2, has been shown to effectively reprogram pro-tumor macrophages into anti-tumor macrophages (46). Additionally, toll-like receptor agonists, CAR macrophages, and PI3K inhibitors demonstrate anti-tumor activities by the activation of macrophage reprogramming and anticancer phenotypes (46). The results of our study indicate that increased AIM2 expression may enhance the recruitment of macrophages, with a significant positive association observed between AIM2 expression and the macrophage markers CCR2, CD163, and TLR7. These findings suggest that targeting AIM2 could potentially modulate macrophage function.

Neutrophils, as the predominant immune cells in the bloodstream, exhibit a dual role in cancer immunotherapy. Their effect on tumor progression is contingent upon the molecular markers present on their surface, with certain neutrophil populations capable of either facilitating or impeding tumor growth. Enhanced efficacy of immunotherapy is associated with an increased presence of anti-tumor neutrophils in the TME (47). Conversely, CD300ld has been shown to be upregulated in pathologically activated neutrophils, leading to its role in suppressing T-cell activation through the STAT3-S100A8/A9 axis (48). Knockout of CD300ld has been found to reverse the immune-suppressive microenvironment in tumors (48). Recent studies have shown that neutrophil and neutrophil extracellular traps are also involved in the immunosuppression of AML (49,50). Our research also revealed that AIM2, serves as a crucial ICM, and facilitates the accumulation of neutrophils in individuals with AML. Our findings showed a noteworthy association between AIM2 expression and neutrophil-related marker expression such as CXCR2, S100A8, ITGAM, FCGR3A, FCGR2A, and CD55 in AML samples. The TME in AML frequently demonstrates immunosuppressive characteristics, including the accumulation of TAMs, Tregs, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (51-53). These elements can impede effector T cell function and diminish the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors (10,52,53). Furthermore, AML cells may directly suppress T cell activity and attenuate the response to immune checkpoint inhibitors through the expression of PD-L1 and other ICMs (10). Considering the intricate interactions between AML immune cells and various environmental components, it is plausible to hypothesize that the future of AML immunotherapy resides in the strategic integration of complementary immunotherapy approaches with chemotherapeutic agents or other inhibitors targeting carcinogenic pathways.

Adverse prognostic factors associated with AML include an age greater than 60 years, a prior history of myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPN), treatment-related or secondary AML, hyperleukocytosis, central nervous system involvement, chromosomal abnormalities or molecular genetic markers indicative of poor prognosis, and the failure to achieve complete remission after two courses of induction chemotherapy (54-56). Our findings indicate that the ICM AIM2, which is related to FLT3 mutations, is associated with poor prognosis. Conversely, our analysis revealed that the enrichment scores of four major immune cell types do not correlate with the prognosis of AML. Nevertheless, immunoinvasive AML has been associated with poor prognosis (57), and various immune cell enrichment scoring algorithms may yield disparate prognostic outcomes. While our study did not identify a statistically significant correlation between macrophage enrichment and poor prognosis in AML, there was a tendency for lower macrophage enrichment to be linked with better prognostic outcomes. It is well-documented that macrophage enrichment is correlated with poor prognosis in various tumor types (58,59). Consequently, the relationship between immune cell enrichment and AML prognosis warrants further investigation with a larger sample size to achieve more definitive conclusions.

The current study had some limitations; while we showed that the high expression of AIM2 led to the induction of suppressive immune subsets, including macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes, the specific relationship between AIM2 and M1/M2 macrophages and the potential involvement of AIM2 in macrophage reprogramming remain unclear. Second, our research utilized data from The TCGA database, which lacks specific classification of FLT3 mutations. Consequently, it is not feasible to analyze the correlation between AIM2 expression and distinct FLT3 mutations.

Conclusions

Our results identify AMI2 as a crucial ICM linked to FLT3 mutations, and demonstrates that the elevated expression of AMI2 is correlated with unfavorable outcomes in patients with AML. Our subsequent investigations suggest that AMI2 may be involved in the activation of suppressive immune cell populations, such as macrophages, neutrophils, and monocytes, leading to immune evasion in AML. Molecular mechanism analyses indicate AMI2-mediated modulation of immune infiltration in AML via the canonical inflammasome signaling pathway.

Supplementary

The article’s supplementary files as

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (as revised in 2013).

Reporting Checklist: The authors have completed the REMARK reporting checklist. Available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-24-1403/rc

Conflicts of Interest: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (available at https://tcr.amegroups.com/article/view/10.21037/tcr-24-1403/coif). J.A.M.N. serves as an unpaid editorial board member of Translational Cancer Research from September 2023 to August 2025. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

(English Language Editor: L. Huleatt)

References

- 1.Li JF, Cheng WY, Lin XJ, et al. Aging and comprehensive molecular profiling in acute myeloid leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024;121:e2319366121. 10.1073/pnas.2319366121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chianese U, Papulino C, Megchelenbrink W, et al. Epigenomic machinery regulating pediatric AML: Clonal expansion mechanisms, therapies, and future perspectives. Semin Cancer Biol 2023;92:84-101. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2023.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeWolf S, Tallman MS, Rowe JM, et al. What Influences the Decision to Proceed to Transplant for Patients With AML in First Remission? J Clin Oncol 2023;41:4693-703. 10.1200/JCO.22.02868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Chaer F, Hourigan CS, Zeidan AM. How I treat AML incorporating the updated classifications and guidelines. Blood 2023;141:2813-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Short NJ, Nguyen D, Ravandi F. Treatment of older adults with FLT3-mutated AML: Emerging paradigms and the role of frontline FLT3 inhibitors. Blood Cancer J 2023;13:142. 10.1038/s41408-023-00911-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forsberg M, Konopleva M. AML treatment: conventional chemotherapy and emerging novel agents. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2024;45:430-48. 10.1016/j.tips.2024.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Senapati J, Kadia TM, Ravandi F. Maintenance therapy in acute myeloid leukemia: advances and controversies. Haematologica 2023;108:2289-304. 10.3324/haematol.2022.281810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakhtiyaridovvombaygi M, Yazdanparast S, Mikanik F, et al. Cytokine-Induced Memory-Like NK Cells: Emerging strategy for AML immunotherapy. Biomed Pharmacother 2023;168:115718. 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.115718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haubner S, Mansilla-Soto J, Nataraj S, et al. Cooperative CAR targeting to selectively eliminate AML and minimize escape. Cancer Cell 2023;41:1871-1891.e6. 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang ZW, Zhang XN, Zhang L, et al. STAT5 promotes PD-L1 expression by facilitating histone lactylation to drive immunosuppression in acute myeloid leukemia. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2023;8:391. 10.1038/s41392-023-01605-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nixdorf D, Sponheimer M, Berghammer D, et al. Adapter CAR T cells to counteract T-cell exhaustion and enable flexible targeting in AML. Leukemia 2023;37:1298-310. 10.1038/s41375-023-01905-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dao T, Xiong G, Mun SS, et al. A dual-receptor T-cell platform with Ab-TCR and costimulatory receptor achieves specificity and potency against AML. Blood 2024;143:507-21. 10.1182/blood.2023021054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vegivinti CTR, Keesari PR, Veeraballi S, et al. Role of innate immunological/inflammatory pathways in myelodysplastic syndromes and AML: a narrative review. Exp Hematol Oncol 2023;12:60. 10.1186/s40164-023-00422-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tettamanti S, Pievani A, Biondi A, et al. Catch me if you can: how AML and its niche escape immunotherapy. Leukemia 2022;36:13-22. 10.1038/s41375-021-01350-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ediriwickrema A, Gentles AJ, Majeti R. Single-cell genomics in AML: extending the frontiers of AML research. Blood 2023;141:345-55. 10.1182/blood.2021014670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brauneck F, Fischer B, Witt M, et al. TIGIT blockade repolarizes AML-associated TIGIT(+) M2 macrophages to an M1 phenotype and increases CD47-mediated phagocytosis. J Immunother Cancer 2022;10:e004794. 10.1136/jitc-2022-004794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mirazee J, Shah NN. CD70 CAR T cells in AML: Form follows function. Cell Rep Med 2022;3:100639. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu G, Guo S, Luo Q, et al. Preclinical evaluation of CD70-specific CAR T cells targeting acute myeloid leukemia. Front Immunol 2023;14:1093750. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1093750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheng J, Ge T, Zhu X, et al. Preclinical development and evaluation of nanobody-based CD70-specific CAR T cells for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2023;72:2331-46. 10.1007/s00262-023-03422-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du L, Wang X, Chen S, et al. The AIM2 inflammasome: A novel biomarker and target in cardiovascular disease. Pharmacol Res 2022;186:106533. 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang B, Bhattacharya M, Roy S, et al. Immunobiology and structural biology of AIM2 inflammasome. Mol Aspects Med 2020;76:100869. 10.1016/j.mam.2020.100869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chou WC, Guo Z, Guo H, et al. AIM2 in regulatory T cells restrains autoimmune diseases. Nature 2021;591:300-5. 10.1038/s41586-021-03231-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang Z, Dong X, Yang X, et al. Expression and clinical significance of absent in melanoma 2 in colorectal cancer. Biomed Pharmacother 2017;94:843-9. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choubey D. Absent in melanoma 2 proteins in the development of cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 2016;73:4383-95. 10.1007/s00018-016-2296-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Qin Y, Pan L, Qin T, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of AIM2 inflammasomes with potential implications for immunotherapy in human cancer: A bulk omics research and single cell sequencing validation. Front Immunol 2022;13:998266. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.998266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chai D, Zhang Z, Shi SY, et al. Absent in melanoma 2-mediating M1 macrophages facilitate tumor rejection in renal carcinoma. Transl Oncol 2021;14:101018. 10.1016/j.tranon.2021.101018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colarusso C, Terlizzi M, Falanga A, et al. Absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2) positive profile identifies a poor prognosis of lung adenocarcinoma patients. Int Immunopharmacol 2023;124:110990. 10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alanazi M, Weng T, McLeod L, et al. Cytosolic DNA sensor AIM2 promotes KRAS-driven lung cancer independent of inflammasomes. Cancer Sci 2024;115:1834-50. 10.1111/cas.16171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010;26:139-40. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bottomly D, Long N, Schultz AR, et al. Integrative analysis of drug response and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2022;40:850-864.e9. 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshihara K, Shahmoradgoli M, Martínez E, et al. Inferring tumour purity and stromal and immune cell admixture from expression data. Nat Commun 2013;4:2612. 10.1038/ncomms3612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bindea G, Mlecnik B, Tosolini M, et al. Spatiotemporal dynamics of intratumoral immune cells reveal the immune landscape in human cancer. Immunity 2013;39:782-95. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen B, Khodadoust MS, Liu CL, et al. Profiling Tumor Infiltrating Immune Cells with CIBERSORT. Methods Mol Biol 2018;1711:243-59. 10.1007/978-1-4939-7493-1_12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods 2015;12:453-7. 10.1038/nmeth.3337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang Q, Wang Z. Serpin family H member 1 and its related collagen gene network are the potential prognostic biomarkers and anticancer targets for glioma. J Biochem Mol Toxicol 2024;38:e23541. 10.1002/jbt.23541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karin N, Razon H. The role of CCR5 in directing the mobilization and biological function of CD11b(+)Gr1(+)Ly6C(low) polymorphonuclear myeloid cells in cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2018;67:1949-53. 10.1007/s00262-018-2245-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marin-Acevedo JA, Kimbrough EO, Manochakian R, et al. Immunotherapies targeting stimulatory pathways and beyond. J Hematol Oncol 2021;14:78. 10.1186/s13045-021-01085-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morad G, Helmink BA, Sharma P, et al. Hallmarks of response, resistance, and toxicity to immune checkpoint blockade. Cell 2021;184:5309-37. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.09.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bystrom R, Levis MJ. An Update on FLT3 in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Landscape. Curr Oncol Rep 2023;25:369-78. 10.1007/s11912-023-01389-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lawal B, Kuo YC, Khedkar H, et al. Deciphering the immuno-pathological role of FLT, and evaluation of a novel dual inhibitor of topoisomerases and mutant-FLT3 for treating leukemia. Am J Cancer Res 2022;12:5140-59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lange A, Jaskula E, Lange J, et al. The sorafenib anti-relapse effect after alloHSCT is associated with heightened alloreactivity and accumulation of CD8+PD-1+ (CD279+) lymphocytes in marrow. PLoS One 2018;13:e0190525. 10.1371/journal.pone.0190525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mellman I, Chen DS, Powles T, et al. The cancer-immunity cycle: Indication, genotype, and immunotype. Immunity 2023;56:2188-205. 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jin HR, Wang J, Wang ZJ, et al. Lipid metabolic reprogramming in tumor microenvironment: from mechanisms to therapeutics. J Hematol Oncol 2023;16:103. 10.1186/s13045-023-01498-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu J, Cao X. Glucose metabolism of TAMs in tumor chemoresistance and metastasis. Trends Cell Biol 2023;33:967-78. 10.1016/j.tcb.2023.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li W, Wang F, Guo R, et al. Targeting macrophages in hematological malignancies: recent advances and future directions. J Hematol Oncol 2022;15:110. 10.1186/s13045-022-01328-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gungabeesoon J, Gort-Freitas NA, Kiss M, et al. A neutrophil response linked to tumor control in immunotherapy. Cell 2023;186:1448-1464.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2023.02.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang C, Zheng X, Zhang J, et al. CD300ld on neutrophils is required for tumour-driven immune suppression. Nature 2023;621:830-9. 10.1038/s41586-023-06511-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fu D, Zhang B, Wu S, et al. Molecular subtyping of acute myeloid leukemia through ferroptosis signatures predicts prognosis and deciphers the immune microenvironment. Front Cell Dev Biol 2023;11:1207642. 10.3389/fcell.2023.1207642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang J, Wang H, Ding Y, et al. NET-related gene signature for predicting AML prognosis. Sci Rep 2024;14:9115. 10.1038/s41598-024-59464-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gournay V, Vallet N, Peux V, et al. Immune landscape after allo-HSCT: TIGIT- and CD161-expressing CD4 T cells are associated with subsequent leukemia relapse. Blood 2022;140:1305-21. 10.1182/blood.2022015522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kent A, Crump LS, Davila E. Beyond αβ T cells: NK, iNKT, and γδT cell biology in leukemic patients and potential for off-the-shelf adoptive cell therapies for AML. Front Immunol 2023;14:1202950. 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1202950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sauerer T, Velázquez GF, Schmid C. Relapse of acute myeloid leukemia after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: immune escape mechanisms and current implications for therapy. Mol Cancer 2023;22:180. 10.1186/s12943-023-01889-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Haddad FG, Sasaki K, Senapati J, et al. Outcomes of Patients With Newly Diagnosed AML and Hyperleukocytosis. JCO Oncol Pract 2024. [Epub ahead of print]. doi: . 10.1200/OP.24.00027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DiNardo CD, Erba HP, Freeman SD, et al. Acute myeloid leukaemia. Lancet 2023;401:2073-86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00108-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shimony S, Stahl M, Stone RM. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am J Hematol 2023;98:502-26. 10.1002/ajh.26822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vadakekolathu J, Minden MD, Hood T, et al. Immune landscapes predict chemotherapy resistance and immunotherapy response in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2020;12:eaaz0463. 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaz0463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Matusiak M, Hickey JW, van IJzendoorn DGP, et al. Spatially Segregated Macrophage Populations Predict Distinct Outcomes in Colon Cancer. Cancer Discov 2024;14:1418-39. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-23-1300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang LX, Zhang CT, Yang MY, et al. C1Q labels a highly aggressive macrophage-like leukemia population indicating extramedullary infiltration and relapse. Blood 2023;141:766-86. 10.1182/blood.2022017046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]