Abstract

Introduction

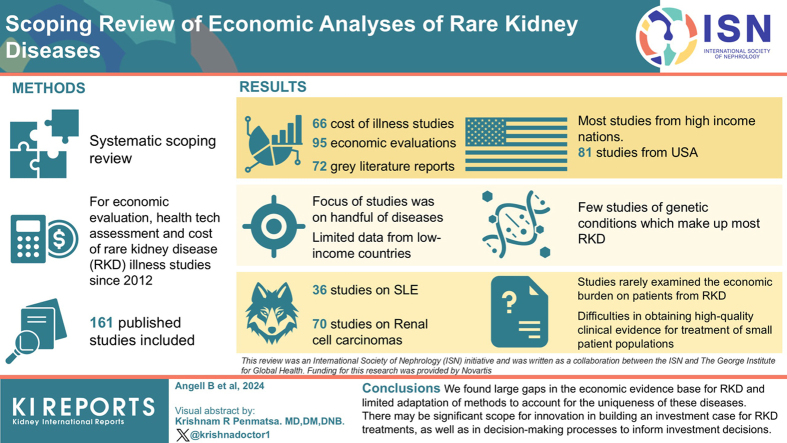

Rare kidney diseases (RKDs) place a substantial economic burden on patients and health systems, the extent of which is unknown and may be systematically underestimated by health economic techniques. We aimed to investigate the economic burden and cost-effectiveness evidence base for RKDs.

Methods

We conducted a systematic scoping review to identify economic evaluations, health technology assessments, and cost-of-illness studies relating to RKDs, published since 2012.

Results

A total of 161 published studies, including 66 cost-of-illness studies and 95 economic evaluations; 72 grey literature reports were also included. Most published literature originated from high-income nations, particularly the USA (81 studies), and focused on a handful of diseases, notably renal cell carcinomas (70) and systemic lupus erythematosus (36). Limited evidence was identified from lower-income settings and there were few studies of genetic conditions, which make up most RKDs. Some studies demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of existing treatments; however, there were limited considerations of broader economic impacts on patients that may be important to those with RKDs. Included health technology assessments highlighted difficulties in obtaining high-quality clinical evidence for treatments in very small patient populations, and often considered equity issues and other patient impacts qualitatively alongside clinical and economic evidence in their recommendations.

Conclusion

We found large gaps in the economic evidence base for RKDs and limited adaptation of methods to account for the uniqueness of these diseases. There may be significant scope for innovation in building an investment case for RKD treatments, as well as in decision-making processes to inform investment decisions.

Keywords: cost-effectiveness, economic burden, rare kidney disease

Graphical abstract

Although there is no universally accepted definition, rare kidney diseases (RKDs) are often defined as a group of over 150 conditions affecting the kidneys, many of which are inherited, with a prevalence of about 60 to 80 cases per 100,000 in Europe and the USA.1, 2, 3 Less is known about the prevalence of these conditions in the rest of the world, especially low- and lower-middle-income countries.

The diagnosis and management of RKDs present distinct challenges to patients, their families, and health systems. Patients and their families face prolonged periods of multiple tests and uncertainty before diagnosis, while the diseases themselves contribute significantly to morbidity, premature mortality, and economic stress for those affected.2,3 For health systems, small numbers of patients, unidentified causes, lack of diagnostic tools, limited treatment options and complex care needs challenge the ability of even well-resourced health systems to provide appropriate and responsive care.2,4 Further, though each individual disease is uncommon, collectively, RKDs place significant burdens on health systems.4 Emerging data from the UK have demonstrated that people with RKDs have a higher likelihood of experiencing kidney failure but are less than half as likely to die with chronic kidney disease stages 3 to 5, therefore accounting for a disproportionate share of patients on kidney replacement therapy. This suggests that better treatments for these diseases at earlier stages could effectively curb the growing demand for expensive kidney replacement therapy and yield disproportionate economic benefits across health systems.5

Investing in treatments and care for RKD necessitates trade-offs. Despite the life-changing potential of effective therapies for patients and their families, their overall impact on population health may be limited by small numbers of patient for individual diseases. Therefore, investing scarce resources in high-cost treatments for relatively small groups seemingly detracts from potentially larger population health gains from alternative investments in more common public health problems. This is further complicated by a large unmet need, because effective targeted treatments are available for less than 10% of RKDs. Incentives to the pharmaceutical industry to develop treatments for RKDs may be weak, given the small potential market, unless countered by specific regulatory frameworks to encourage investment. Further, given the overrepresentation of people with RKD among those receiving kidney replacement therapy,5 such conditions pose major financial challenges for low- and middle-income countries, which are seeing a higher proportion of their health care budgets being used for kidney replacement therapy (relative to high-income settings).4,6 Given the substantial burden of health care costs experienced by individual patients, much of which is borne out of pocket in low- and middle-income nations, there may be strong equity arguments for regulatory provisions that address the barriers new RKD treatments encounter in conventional HTA processes. Approaches to funding treatments for rare diseases vary across countries.7,8 Some nations, such as Latvia and Bulgaria, exempt treatments for rare diseases from HTA processes, whereas others, including the UK, Sweden, and Australia, have developed guidelines for drugs for rare diseases that go beyond usual cost-effectiveness considerations. Others, such as Slovakia and Romania, do not have explicit processes for rare diseases. Policy development is often limited by the lack of large databases.

We conducted a systematic scoping review of the published and grey literature to investigate the current economic evidence base supporting investment into treatments for RKDs. We sought to identify the evidence base estimating the economic impact of RKDs on health systems around the world as well as the comparative cost-effectiveness of available treatments for these conditions. A scoping review method was used because we sought to capture diverse studies incorporating different patient groups, methods, and health systems, as well as identifying gaps in the existing literature. Although no previous reviews were found investigating the economic burden of RKDs, several scoping reviews have examined the cost of illness studies in rare diseases or have focused specifically on economic evaluations of some rare diseases (not limited to those affecting the kidneys) in certain contexts.9, 10, 11 One recently published study examined economic evaluations of inherited rare diseases in a selected group of high-income nations, finding that patient costs are rarely included in such studies, which the authors suggest may be systematically underestimating the cost-effectiveness of such treatments.11 Here, we build on these previous studies to draw together the global economic evidence base, including economic evaluations, health technology assessments, and cost-of-illness studies in the field of RKDs. In doing so, we hope to illustrate the current case for investment in treatments for RKDs, identify shortcomings in the health economic approaches used in these studies, and identify potential areas for improvement.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review to identify economic evaluations, cost analyses, and health technology assessments of interventions for RKDs. The review specifically sought to identify the following:

-

1.

the economic burden of RKDs and relative cost-effectiveness of available treatment;

-

2.

the extent and type of economic evidence available to inform investment decisions for treatments of RKDs in countries around the world;

-

3.

gaps in the existing literature relating to the income classification of countries where evidence exists, types of treatment and diseases covered, the applicability of methods and perspectives taken in these analyses, and;

-

4.

whether any specific adjustments to HTA processes had been identified that had occurred or were recommended within this evidence base.

Study Selection

Studies published between December 2012 and the time of search (May 2023) were included if they examined the cost, cost-effectiveness, or value of treatment for a rare kidney disease. The list of eligible RKDs was developed based on the existing Orphanet list of rare diseases and European Rare Kidney Disease registry.12,13 A brief literature review was conducted to confirm that all conditions were associated with kidney disease. Conditions without an association with kidney disease were not included in this study. Some conditions, such as renal cell carcinomas, which are not necessarily rare, were only eligible for inclusion if they were associated with rare syndromes. The full list of conditions is provided in the Supplementary Material.

Searches were conducted in the PubMed, EMBASE, and Global Health databases. Briefly, searches contained terms (keywords and MESH subject headings) to identify relevant methodologies (e.g., economic evaluations, health technology assessments, budget impact analyses, cost-of-illness studies, and other cost analyses) and eligible RKDs. No restrictions were placed on the country of study or interventions included. The search strategy used in Medline is provided in the Supplementary Table S1. This was supplemented by a search of the grey literature involving targeted searches of the websites of HTA institutions and national or regional kidney association websites, as well as Google searches of key terms to identify non peer-reviewed and publicly available studies. Websites searched included specific HTA institutions, including the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, Australia’s Medical Services Advisory Committee and Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee, and the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Key kidney and rare disease-related sources were also searched, including the International Rare Diseases Research Consortium, The UK Kidney Association, Overton, and Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Controversies Conferences.14, 15, 16, 17, 18

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Results from the database searches were uploaded into Rayyan,19 and titles and abstracts were screened by 1 of 3 authors (SW, TG, or BA) for potential suitability for inclusion in this review. Full texts were then screened for inclusion by the same authors who proceeded to extract data from the included studies. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus in all circumstances. Data were extracted on study characteristics and findings, including country, method, time horizon, discount rate and perspective of analysis, the disease or diseases of interest, types of costs included, intervention studied, results, key drivers of costs, whether budget impacts were considered or analyzed, and if the paper raised issues or shortcomings with HTA or funding systems about RKD treatments. We synthesized the evidence in accordance with method of Arksey and O’Malley20 (2005) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Scoping Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews guidance21 (Supplementary Material).

Results

Overview of Peer-Reviewed Economic Evidence Base

A total of 1802 articles were identified from the database search after the removal of duplicates and screened for potential inclusion (Supplementary Figure S1). Full texts were screened of 260 studies and ultimately, 161 peer-reviewed published papers met our inclusion criteria for this review: 66 cost-of-illness studies22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87 and 95 economic evaluations,88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, 105, 106, 107, 108, 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125, 126, 127, 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135, 136, 137, 138, 139, 140, 141, 142, 143, 144, 145, 146, 147, 148, 149, 150, 151, 152, 153, 154, 155 including 27 cost analyses.156, 157, 158, 159, 160, 161, 162, 163, 164, 165, 166, 167, 168, 169, 170, 171, 172, 173, 174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181, 182 The characteristics of these studies are shown in Table 1. Most of the economic evidence emanated from the United States (78 studies) and other high-income nations, with limited evidence from low- and middle-income nations (17 studies including 10 from China). The vast majority of studies (128) considered costs from the health care payer perspective. Studies examining 30 different RKDs were included in our review, though most focused on renal cell carcinoma (71 studies) and systemic lupus erythematosus (36). Very few studies explicitly noted shortcomings in current health technology assessment processes regarding RKDs. Approximately half of the included studies examined the economic burden of the RKD on patients and health systems without examining the impact of an intervention, whereas the remainder were economic evaluations of interventions to treat RKDs.

Table 1.

General characteristics of included studies

| Characteristics | Total n (%) | Cost-of-illness (n = 66) | Cost-effectiveness analyses (n = 68) | Cost analyses (n = 27) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication (n = 161) | ||||

| 2012–2017 | 80 (50) | 26 | 47 | 7 |

| 2018–2023 | 81 (50) | 40 | 21 | 20 |

| Country of studya (n = 169) | ||||

| High-income | 150 (89) | 66 | 61 | 23 |

| USA | 81 (48) | 32 | 33 | 16 |

| Europe | 38 (22) | 20 | 12 | 6 |

| UK | 10 (6) | 2 | 7 | 1 |

| Other high income | 21 (12) | 12 | 9 | 0 |

| Low or middle income | 19 (11) | 4 | 10 | 5 |

| Other low or middle income | 9 (5) | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| China | 10 (6) | 3 | 6 | 1 |

| Disease studied (n = 161) | ||||

| Renal cell carcinoma | 70 (43) | 10 | 47 | 13 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 36 (22) | 27 | 5 | 4 |

| Systemic sclerosis | 8 (5) | 7 | 0 | 1 |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | 7 (4) | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Tuberous sclerosis complex | 7 (4) | 6 | 1 | 0 |

| Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | 6 (4) | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Amyloid light chain amyloidosis | 4 (2) | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Acute intermittent porphyria | 3 (2) | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Gaucher disease type 1 | 3 (2) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency | 2 (1) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis | 2 (1) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Fabry disease | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Neurofibromatosis type 1 | 2 (1) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Otherb | 9 (6) | 2 | 5 | 2 |

| Perspective adopteda (n = 162) | ||||

| Health system or health payer | 128 (79) | 51 | 50 | 27 |

| Societal | 14 (9) | 7 | 7 | 0 |

| Other (e.g., patient or unclear) | 20 (12) | 8 | 12 | 0 |

Multiple perspectives and countries covered in some studies.

Including acute hepatic porphyria, familial mediterranean fever, galactosemia, giant cell arteritis, idiopathic nephrotic syndrome, polyarteritis nodosa, thrombotic microangiopathy, X-linked hypophosphatemia, and sickle cell anemia.

The Economic Burden of RKDs (Cost-of-Illness Studies)

In total, 66 cost-of-illness studies examined RKDs (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S2). The majority of these were conducted in high-income nations, particularly the USA (n = 32). Seventeen RKDs were covered across the cost-of-illness studies; 26 studies focused on systemic lupus erythematosus (including complications such as nephritis), 10 on renal cell carcinoma (including metastatic), 7 on systemic sclerosis, and 6 on tuberous sclerosis complex. Sample sizes for included studies ranged from 47 patients with tuberous sclerosis complex,74 to a nation-wide study of 22,258 systemic lupus erythematosus cases in Taiwan.34

Nearly all studies were retrospective, using insurance databases or patient registries to collect cost data. Only 2 studies prospectively recruited patients,32,35, whereas 4 collected patient costs through audits of clinical records and 2 estimated costs using economic models.24,62 Most studies adopted a health system or payer perspective (n = 51), 8 took a patient perspective, and 7 took a societal perspective.22, 23, 24,35,52,55,58 Of the latter, 5 studies calculated indirect costs using the human capital approach,22,23,35,52,58 whereas Knarborg et al.55 (2022) estimated indirect costs “as the differences in earning between matched cases and controls based on earned income and various social security compensation,” and Connolly et al.24 (2021) modeled the differences in lifetime earnings for patients with acute hepatic porphyria compared to the general population.24,55

The cost of illness studies demonstrated a large economic burden associated with RKDs, though most reported on diseases that involve multiple systems. Despite variation across specific conditions and health systems, studies identified that patients with RKDs incurred higher costs than those without. Across all included studies, regardless of disease type, direct medical costs were the main cost drivers, including hospitalization, utilization of outpatient services, and medication costs. In studies that adopted a societal perspective, key cost drivers included medical costs and foregone earnings related to long-term disability and sick leave.

Economic Evaluations of Treatments for RKDs

Sixty-eight studies examined the cost-effectiveness or cost utility of interventions for treatments of rare kidney diseases, including 2 cost-benefit analyses. An additional 27 studies were cost analyses that compared the relevant costs of treating people living with RKDs with specific treatments compared to usual care. The majority of cost-effectiveness and cost-utility studies were based in high-income countries, again predominantly the USA (n = 30), compared to low-and-middle income settings (10 studies, including 6 in China) (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S3). Most of these studies (n = 44) investigated the cost-effectiveness of first line and second-line treatments for renal cell carcinomas in different settings. Nearly all studies (n = 61) were modelled economic evaluations, with a few retrospective cohort studies (n = 7) that assessed cost-effectiveness. The time horizon of studies ranged from a few days to lifetime depending on the condition of interest. The most common discount rate used was 3% (n = 36) and most studies (n = 50) took the health system perspective, assessing the direct medical costs and effectiveness of treatments on national health care sector and third-party payers. Some studies also took a broader societal perspective, incorporating indirect costs such as loss in productivity and increased caregiver burden into the evaluation process (n = 7).95,96,131,133,135,145,180 Although diverse, the majority of studies examined drug-based treatments (n = 54), particularly for the first line and second-line treatments for renal cell carcinomas (n = 43). Aside from pharmaceutical treatments, included studies also evaluated the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic tests, screening and prevention programs, and disease management programs.

Table 2.

Summary of economic evaluation evidence

| Characteristics of economic evaluations included | Total n (%) | Cost-effective (n = 42) | Not cost-effective (n = 16) | Mixed results (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of studya (n = 71) | ||||

| High-income | 61 (86) | 38 | 13 | 10 |

| USA | 33 (46) | 19 | 7 | 7 |

| Europe | 12 (17) | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| UK | 7 (10) | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| Other high income | 9 (13) | 6 | 3 | 0 |

| Low or middle income | 10 (14) | 9 | 1 | 0 |

| Other low or middle income | 4 (6) | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| China | 6 (8) | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Intervention type (n = 68) | ||||

| Pharmaceutical interventions | 53 (78) | 31 | 15 | 7 |

| Nonpharmaceutical interventions | 15 (22) | 11 | 1 | 3 |

| Intervention studieda (n = 73) | ||||

| Renal cell carcinoma | ||||

| First line interventions | 33 (45) | 19 | 12 | 2 |

| Pazopanib vs. sunitinib | 6 (8) | 5 | 1 | 0 |

| Pembrolizumab plus axitinib vs. sunitinib | 4 (5) | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Nivolumab based strategies vs. sunitinibb | 11 (15) | 7 | 3 | 1 |

| Others vs. sunitinibc | 8 (11) | 3 | 5 | 0 |

| Other first line interventionsd | 4 (5) | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Second line interventionse | 11 (15) | 8 | 2 | 1 |

| Screening programs and other | 9 (12) | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | ||||

| Belimumab vs. soc | 3 (4) | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Lupus self-management program | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | ||||

| Screening programs | 2 (3) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Otherf | 2 (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Other disease interventionsg | 12 (16) | 7 | 2 | 3 |

Soc, AAA.

Multiple interventions and countries covered in some studies.

Including nivolumab plus ipilimumab and nivolumab plus cabozantinib.

Including lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab, anlotinib, and avelumab plus axitinib.

Including nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs. pembrolizumab plus axitinib, and nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs. pazopanib.

Including everolimus vs. sorafenib, cabozantinib vs. everolimus, nivolumab vs. everolimus, ofaxitinib vs. sorafenib, nivolumab vs. axitinib, pazopanib, everolimus and cabozantinib and cabozantinib vs. axitinib, and cabozantinib vs. nivolumab.

Including tolvaptan vs. soc and ace (angiotensin-converting enzymes inhibitors) vs. arb (angiotensin ii receptor blockers).

Including interventions for eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, galactosemia, Gaucher disease type 1, giant cell arteritis, idiopathic nephrotic syndrome, thrombotic microangiopathy, tuberous sclerosis complex, and X-linked hypophosphatemia.

Cost-Effectiveness of Included Interventions

Of the 68 studies evaluating the cost-effectiveness of treatments, 42 provided favorable cost-effectiveness evidence in support of the intervention, 16 indicated that the intervention was not cost-effective, and the remaining 10 reported mixed results. Of the 53 studies evaluating pharmaceutical interventions, 15 reported unfavorable cost-effectiveness results, whereas 12 out of 15 studies evaluating nonpharmaceutical interventions were found to be cost-effective.139,140,143, 144, 145, 146,148,150, 151, 152, 153 Details of the cost-effectiveness found for different treatment comparisons are shown in Table 2.

Most studies identified medication costs as a key cost driver, consequently impacting cost-effectiveness outcomes.89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95,98,100,101,104,105,118 Other key cost drivers included adverse event management, disease management, administration, and terminal care costs. For screening programs, the key drivers of costs also included screening costs, assessment costs, administrative costs, as well as the cost of early treatment of screened patients and the cost of delayed treatment of unscreened patients. These were generally outweighed by the benefits of reduced downstream health care costs. For studies taking a broader societal perspective, productivity losses and caregiver burden were also important cost components. Those studies that adopted a societal perspective highlighted the increased cost-effectiveness if broader costs were considered. Bindra et al.,135 for example, assessed the cost-effectiveness of Acthar gel (respiratory corticotropin injection) verses standard-of-care treatments in moderate-to-severe systemic lupus erythematosus and found that taking the broader societal perspective as opposed to the payer perspective lowered the Incremental Cost Effectiveness Ratio from $133,110 per quality-adjusted life year to $70,827 per quality-adjusted life year.135

Cost and Cost-Minimization Analyses

Twenty-seven studies were cost and cost consequences analyses, of which the majority (n = 24) were cost minimization studies estimating the cost impacts of introducing new diagnostics or treatments for RKDs compared to the current standard of care (Table 2 and Supplementary Table S3). Like the other included literature, most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 16) and focused on a handful of diseases. Most adopted a health system perspective and identified potential cost savings (n = 23) for health systems, predominantly due to reductions in drug acquisition costs.

Grey Literature

A total of 72 documents were identified in the grey literature,183, 184, 185, 186, 187, 188, 189, 190, 191, 192, 193, 194, 195, 196, 197, 198, 199, 200, 201 65 of which were health technology reports from the UK, Australia, and Canada (Table 3). Forty-eight of these recommended funding for interventions, 17 recommended not supporting estimate and 6 were inclusive, including 1 grey literature report on the cost of tuberous sclerosis complex in the USA. Once again, most reports focused on interventions to treat renal cell carcinoma (31 reports). Most reports focused on treatments for conditions; however, the introduction of certain diagnostic and screening interventions for some RKDs was considered cost-effective in some contexts.183,193,194

Table 3.

Summary of the included grey literature

| Characteristics of grey literature reports included | Total n (%) | Recommended with conditions (n = 48) | Not recommended (n = 17) | Inconclusive evidencea (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of studyb (N = 72) | ||||

| UK | 32 (44) | 25 | 4 | 3 |

| AU | 15 (21) | 9 | 5 | 0 |

| Canada | 20 (28) | 12 | 8 | 0 |

| Other | 5 (7) | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Intervention studiedb (N = 72) | ||||

| Renal cell carcinoma | ||||

| Avelumab-with-axitinib | 2 (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Axitinib | 2 (3) | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Cabozantinib based strategiesc | 5 (7) | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| Lenvatinib based strategiesd | 4 (6) | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Nivolumab based strategiese | 4 (6) | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Pembrolizumab based strategiesf | 5 (7) | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Sorafenib | 2 (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Sunitinib | 2 (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Otherg | 5 (7) | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | ||||

| Belimumab | 3 (4) | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Anifrolumab | 2 (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome | ||||

| Eculizumab | 2 (3) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ravulizumab | 4 (6) | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease | ||||

| Tolvaptan | 3 (4) | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Fabry disease | ||||

| Agalsidase alfa | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Migalastat | 3 (4) | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Pegunigalsidase | 1 (1) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Enzyme replacement therapies | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Other diseases studiedh | 21 (29) | 12 | 4 | 5 |

Includes 1 cost of illness study identified in the grey literature.

Multiple interventions and countries covered in some studies.

Including cabozantinib and cabozantinib plus nivolumab.

Including lenvatinib, lenvatinib plus everolimus, and Lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab.

Including nivolumab and nivolumab-with-ipilimumab.

Including pembrolizumab, pembrolizumab plus axitinib, and pembrolizumab plus lenvatinib.

Including tivozanib, vinflunine, pazopanib, everolimus and bevacizumab (first line), sorafenib (first- and second line), sunitinib (second-line) and temsirolimus (first-line).

Including daratumumab for AL amyloidosis, C3 glomerulopathy, selumetinib for neurofibromatosis type 1, caplacizumab for acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, screening programs for genetic diseases, enzyme replacement therapy for lysosmal storage diseases, enzyme replacement therapies for mucopolysaccharidosis type 1, rituximab for antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, ciclosporin for idiopathic steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, cost-of-illness of tuberous sclerosis complex, and burosumab for X-linked hypophosphatemia.

Grey literature reports commonly raised issues around inadequate clinical or economic evidence to establish the value of a treatment. Nonetheless, most health technology assessments supported funding and often deemed the treatment cost-effective. In addition to cost-effectiveness, included health technology assessments considered other criteria to inform investment decisions, including safety, clinical effectiveness, equity, access and rule of rescue, community preference, and social benefits. Although likely important to formulating an investment case for treatments, these benefits were generally presented qualitatively as part of supporting evidence alongside clinical and economic data. Safety and clinical effectiveness were the 2 most important criteria considered by all assessments in their decision-making process. Safety was incorporated through both the severity of adverse events, as well as the cost of managing these adverse events as part of the economic evaluation process. For clinical effectiveness, assessments reported the clinical effectiveness of the proposed treatments through the literature reviews of relevant clinical trials and synthesizing effectiveness data (noting the limitations in data due to small patient numbers described above). Six assessments explicitly considered equity within their decision criteria. Two documents considered the broader social benefits of the proposed treatments, including the ability to contribute to society or continue education, cost savings from personal expenses for patients and carers for transportation and housing, and caregivers’ ability to return to work, leading to increased productivity.184,189

Discussion

This review has provided a comprehensive assessment of the published economic literature on RKDs. Although the evidence base is diverse and somewhat fragmented, our findings highlight that the economic burden of rare kidney disease treatments on patients, health care systems, and society is substantial. Direct medical costs facing patients are often large and generally increased with severity of the disease, the existence of multiple conditions, hospital admission, and medication costs. Some treatments were identified as cost-effective in certain contexts in this review as were some diagnostic and screening interventions for RKDs. This suggests that well-targeted interventions can offer cost-effective improvements in patient outcomes, even under traditional measures of cost-effectiveness, despite relatively small target populations and indicates the potential for early detection and management.

Dialysis as a downstream consequence of advanced kidney disease is exceedingly expensive, albeit generally still considered cost-effective and reimbursed in many middle- and high-income countries. The review suggests that early and effective treatment interventions could potentially reduce the reliance on such expensive therapies, offering the promise of both health and economic benefits. However, the complexity of RKDs, which often affect multiple organ systems, complicates the assessment of their economic impact. Separating the specific impact of these conditions on the kidneys from their effects on other organ systems remains challenging, because these diseases often present with systemic manifestations contributing to their overall burden. This complexity necessitates a comprehensive approach to economic evaluation that considers the multifaceted nature of these conditions.

The evidence-base pulled together through this review focused primarily on several key conditions and came from a handful of countries. Over half of the cost-effective evidence found relates to renal cell carcinomas, a heterogeneous group of tumors (≥40 subtypes) with distinct genetic, histologic, and phenotypic characteristics. Although individually rare, together they constitute 85% of all kidney cancers.202 Further, most cost-of-illness studies considered diseases involving multiple systems, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, with few studies focusing on genetic conditions comprising most RKDs.

Among the published academic literature, we found limited evidence of methodologies specifically adapted to account for the unique challenges posed by rare diseases to health systems and policymakers. As a result, the literature may underestimate the actual societal economic burden of RKDs. For instance, from a societal perspective, the economic burden of 379 rare diseases in the USA was estimated to reach US $1 trillion in 2019, less than half of which was attributed to direct medical costs.203 Similar evidence should be developed for kidney diseases, and it would be crucial to develop an accurate and compelling argument for policymakers to invest in preventing and treating RKDs.

Other, less tangible impacts, such as health system strengthening impacts, were also largely overlooked in included studies. Previous work has investigated how investing in rare disease programs can build health system resilience by fostering multidisciplinary expertise and improved care quality,204,205 enabling faster decision-making and coordinated response to emerging health care challenges. This is particularly relevant for low- and middle-income countries that have few centers of excellence for RKDs. Research into rare diseases can also spill over into broader gains in medical knowledge and technologies, paving the way for developing new treatments, diagnostic techniques, and therapeutic strategies. The equity implications of investing in treatments for rare genetic diseases were not widely considered, and substantially constrains how an investment case can be made given the high upfront costs, especially in low- and middle-income countries. We found limited evidence that these broader factors were considered for RKDs. More generally, economic evaluations are likely to be challenging to conduct in a field often defined by limited clinical data and uncertainty in outcomes.

Combined, these challenges highlight the uncertainties inherent in funding models and health technology assessment processes regarding funding and incentivizing the development of treatments for RKDs. The evidence of this review suggests that though there are special considerations in some systems for treatments for rare diseases, the unique benefits from treatments for RKDs may be systematically underestimated. There might be scope to trial use of alternative funding mechanisms such as public-private partnerships, tax incentives, or building on existing orphan drug price regulations to improve the economic sustainability of treatment development for RKDs.

There were limitations to our review. Although the strengths of the review lies in the broad search strategy and research question, which enabled us to take a comprehensive view of the impact of RKDs on patients and health systems, the heterogeneity of included studies with regard to their varied scope, diverse populations, and health systems restricted our ability to pool their results or conduct a formal meta-analysis of their results and limited the policy implications that could be drawn from the identified literature. Another challenge for this review was the inconsistent reporting of costs. For instance, it was often unclear if costs were incurred by payers or whether they were out-of-pocket. The difficulty of comparing studies across diseases and settings limits our ability to develop an investment case. This aligns with other reviews and supports the call by Marshall and colleagues for a consistent approach to measuring the burden of rare diseases.11 A significant proportion of the cost-effectiveness evidence found through this review, however, relates to renal cell carcinomas that as a class are not necessarily rare but include numerous rare inherited syndromes associated with such cancers. Most of the evidence found was produced in high-income nations, most notably the USA, with very limited published evidence on the economic impact of RKDs in low and middle-income countries. Most included studies were funded by pharmaceutical companies, potentially skewing the focus of this evidence away from nonpharmaceutical interventions and overlooking regions of the world where there might be less of a potential market. Although these findings highlight several cost-effective interventions in RKDs, efficient and equitable investment options may have been missed due to remaining gaps in evidence. Although we sought to identify reports in the grey literature, challenges associated with this and the nature of health technology assessment processes around the world mean that some of these could have been missed. Furthermore, the difficulty in separating the economic impact of RKDs on kidneys from other organ systems complicates the interpretation of results, because these diseases often have systemic effects. Finally, we did not conduct any quality appraisal of the included studies.

Future research should address the gaps identified in this review by focusing on low- and middle-income countries, where the economic burden of RKDs may be more pronounced due to limited health care resources. Prospective studies incorporating patient-reported outcomes and broader societal perspectives are needed to better capture the full economic impact of RKDs. In addition, research should explore the cost-effectiveness of nonpharmaceutical interventions, such as lifestyle modifications and early screening programs, which could offer cost-saving opportunities. Efforts to develop comprehensive databases and registries for RKDs would enhance the quality and scope of future economic analyses. Moreover, studies should aim to disentangle the specific economic impacts on the kidneys from impacts on other organ systems to better understand the burden associated with RKDs.

Conclusions

Our scoping review of economic evaluations, health technology assessments, and cost of illness studies in RKDs has pulled together this evidence base for the first time. Despite evidence of a substantial economic burden facing health systems from RKDs, there are substantial gaps in the economic literature, particularly regarding geographic location and most disease types. Included studies focused on health system costs with limited consideration of broader costs and impacts that could be significant considerations in investment decisions relating to treatment for RKDs.

Disclosure

DPG reports receiving consulting fees from Novartis, Alexion, Judo Bio, Calliditas, Sanofi, Alnylam, Sofinnova, and Britannia; honoraria payments from Vifor, Sanofi, and Stada. IIU reports honoraria payments from Boehringer Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca and Sanofi. JB reports receiving consulting fees from Alnylam, Argenx, Astellas, BioCryst, Calliditas, Chinook, Dimerix, Galapagos, Novartis, Omeros, Travere Therapeutics, Vera Therapeutics, and Visterra; and grant support from Argenx, Calliditas, Chinook, Galapagos, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Omeros, Travere Therapeutics, and Visterra. DPG is a Trustee and Scientific Advisor for Alport UK, and Chair of UK Kidney Association Rare Diseases Committee. OD is supported by the ITINERARE University Research Priority Program of the University of Zurich and by the European Reference Network for Rare Kidney Diseases (ERKNet) funded by the European Union within the framework of the EU4Health Programme (101085068). BA is supported by a NHMRC Investigator Grant (GNT2010055). ISN provided funding support to The George Institute for Global Health, Australia (AP, AS, BA, SJ, SW, TG) for this research. All the other authors declared no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

This review was an ISN initiative and was written as a collaboration between the ISN and The George Institute for Global Health. Funding for this research was provided by Novartis. The funder did not play a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation or review of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Availability Statement

All data resulting from this research are available in the main text and Supplementary Materials.

Footnotes

Classification and listing of rare renal diseases.

Figure S1. PRISMA flow chart of study inclusion.

Table S1. Search strategy for Medline.

Table S2. Overview of cost-of-illness studies.

Table S3. Overview of economic evaluation studies.

PRISMA Checklist.

Supplementary Material

Classification and listing of rare renal diseases. Figure S1. PRISMA flow chart of study inclusion. Table S1. Search strategy for Medline. Table S2. Overview of cost-of-illness studies. Table S3. Overview of economic evaluation studies. PRISMA Checklist.

References

- 1.Soliman N.A. Orphan kidney diseases. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;120:c194–c199. doi: 10.1159/000339785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devuyst O., Knoers N.V., Remuzzi G., Schaefer F. Board of the Working Group for Inherited Kidney Diseases of the European Renal Association and European Dialysis and Transplant Association. Rare inherited kidney diseases: challenges, opportunities, and perspectives. Lancet. 2014;383:1844–1859. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60659-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aymé S., Bockenhauer D., Day S., et al. Common elements in rare kidney diseases: conclusions from a kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 2017;92:796–808. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2017.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanholder R., Coppo R., Bos W.J.W., et al. A policy call to address rare kidney disease in health care plans. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2023;18:1510–1518. doi: 10.2215/CJN.0000000000000220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong K., Pitcher D., Braddon F., et al. Effects of rare kidney diseases on kidney failure: a longitudinal analysis of the UK National Registry of Rare Kidney Diseases (RaDaR) cohort. Lancet. 2024;403:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02843-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Tol A., Lameire N., Morton R.L., Van Biesen W., Vanholder R. An international analysis of dialysis services reimbursement. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14:84–93. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08150718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whittal A., Nicod E., Drummond M., Facey K. Examining the impact of different country processes for appraising rare disease treatments: a case study analysis. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2021;37:e65. doi: 10.1017/S0266462321000337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nicod E., Lloyd A.J., Morel T., et al. Improving interpretation of evidence relating to quality of life in health technology assessments of rare disease treatments. Patient. 2023;16:7–17. doi: 10.1007/s40271-022-00598-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angelis A., Tordrup D., Kanavos P. Socio-economic burden of rare diseases: a systematic review of cost of illness evidence. Health Policy. 2015;119:964–979. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2014.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.García-Pérez L., Linertová R., Valcárcel-Nazco C., Posada M., Gorostiza I., Serrano-Aguilar P. Cost-of-illness studies in rare diseases: a scoping review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:178. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01815-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall D.A., Gerber B., Lorenzetti D.L., MacDonald K.V., Bohach R.J., Currie G.R. Are we capturing the socioeconomic burden of rare genetic disease? A scoping review of economic evaluations and cost-of-illness studies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2023;41:1563–1588. doi: 10.1007/s40273-023-01308-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orphanet The portal for rare diseases and orphan drugs. https://www.orpha.net/en/disease/detail/269531 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.ERKNet Disease Information. https://www.erknet.org/

- 14.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/

- 15.International Rare Diseases Research Consortium. https://irdirc.org/

- 16.UK Kidney Association. Rare Renal: information on rare kidney diseases. https://ukkidney.org/rare-renal/homepage

- 17.Overton. https://www.overton.io/

- 18.KDIGO Controversies conferences. https://kdigo.org/conferences/

- 19.Ouzzani M., Hammady H., Fedorowicz Z., Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016/12/05;5:210. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricco A.C., Lillie E., Zarin W., et al. PRISMA Extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005/02/01;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jönsen A., Bengtsson A.A., Hjalte F., Petersson I.F., Willim M., Nived O. Total cost and cost predictors in systemic lupus erythematosus −8-years follow-up of a Swedish inception cohort. Lupus. 2015;24:1248–1256. doi: 10.1177/0961203315584812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jönsen A., Hjalte F., Willim M., et al. Direct and indirect costs for systemic lupus erythematosus in Sweden. A nationwide health economic study based on five defined cohorts. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45:684–690. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Connolly M.P., Kotsopoulos N., Vermeersch S., Patris J., Cassiman D. Estimating the broader fiscal consequences of acute hepatic porphyria (AHP) with recurrent attacks in Belgium using a public economic analytic framework. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:346. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01966-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anandarajah A.P., Luc M., Ritchlin C.T. Hospitalization of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus is a major cause of direct and indirect healthcare costs. Lupus. 2017;26:756–761. doi: 10.1177/0961203316676641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bell C.F., Ajmera M.R., Meyers J. An evaluation of costs associated with overall organ damage in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States. Lupus. 2022;31:202–211. doi: 10.1177/09612033211073670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bell C.F., Huang S.P., Cyhaniuk A., Averell C.M. The cost of flares among patients with systemic lupus erythematosus with and without lupus nephritis in the United States. Lupus. 2023;32:301–309. doi: 10.1177/09612033221146093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bell C.F., Wu B., Huang S.P., et al. Healthcare resource utilization and associated costs in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus diagnosed with lupus nephritis. Cureus. 2023;15 doi: 10.7759/cureus.37839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bell C.F., Blauer-Peterson C., Mao J. Burden of illness and costs associated with eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis: evidence from a managed care database in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27:1249–1259. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2021.21002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Betts K.A., Stockl K.M., Yin L., Hollenack K., Wang M.J., Yang X. Economic burden associated with tuberous sclerosis complex in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;112 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.107494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bhandari N.R., Kale H.P., Carroll N.V., et al. Healthcare costs and resource utilization associated with renal cell carcinoma among older Americans: a longitudinal case-control study using the SEER-Medicare data. Urol Oncol. 2022;40:347.e17–347.e27. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2022.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Blaylock B., Epstein J., Stickler P. Real-world annualized healthcare utilization and expenditures among insured US patients with acute intermittent porphyria (AIP) treated with hemin. J Med Econ. 2020;23:537–545. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2020.1724118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buja A., De Luca G., Gatti M., et al. Renal cell carcinoma: the population, real world, and cost-of-illness. BMC Urol. 2022;22:206. doi: 10.1186/s12894-022-01160-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiu Y.M., Chuang M.T., Lang H.C. Medical costs incurred by organ damage caused by active disease, comorbidities and side effect of treatments in systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a Taiwan nationwide population-based study. Rheumatol Int. 2016;36:1507–1514. doi: 10.1007/s00296-016-3551-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho J.H., Chang S.H., Shin N.H., et al. Costs of illness and quality of life in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus in South Korea. Lupus. 2014;23:949–957. doi: 10.1177/0961203314524849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cholley T., Thiery-Vuillemin A., Limat S., et al. Economic burden of metastatic clear-cell renal cell carcinoma for French patients treated with targeted therapies. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2019;17:e227–e234. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2018.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clarke A.E., Urowitz M.B., Monga N., Hanly J.G. Costs associated with severe and nonsevere systemic lupus erythematosus in Canada. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:431–436. doi: 10.1002/acr.22452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarke A.E., Yazdany J., Kabadi S.M., et al. The economic burden of systemic lupus erythematosus in commercially- and Medicaid-insured populations in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:759–768. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dall’Era M., Kalunian K., Eaddy M., et al. Real-world treatment utilization and economic implications of lupus nephritis disease activity in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2023;29:36–45. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2022.21496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doria A., Amoura Z., Cervera R., et al. Annual direct medical cost of active systemic lupus erythematosus in five European countries. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:154–160. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-202443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Eriksson D., Karlsson L., Eklund O., et al. Real-world costs of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease in the Nordics. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:560. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2513-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fagnani F., Laurendeau C., de Zelicourt M., Marshall J. Epidemiology and disease burden of tuberous sclerosis complex in France: a population-based study based on national health insurance data. Epilepsia Open. 2022;7:633–644. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fatoye F., Gebrye T., Svenson L.W. Direct health system costs for systemic lupus erythematosus patients in Alberta, Canada. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Furst D.E., Clarke A., Fernandes A.W., et al. Medical costs and healthcare resource use in patients with lupus nephritis and neuropsychiatric lupus in an insured population. J Med Econ. 2013;16:500–509. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.772058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gagnon-Sanschagrin P., Liang Y., Sanon M., Oberdhan D., Guérin A., Cloutier M. Excess healthcare costs in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease by renal dysfunction stage. J Med Econ. 2021;24:193–201. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2021.1877146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Geynisman D.M., Hu J.C., Liu L., Tina Shih Y.C. Treatment patterns and costs for metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients with private insurance in the United States. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2015;13:e93–e100. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2014.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hagiwara M., Hackshaw M.D., Oster G. Economic burden of selected adverse events in patients aged ≥65 years with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Med Econ. 2013/11/01;16:1300–1306. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2013.838570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang M., Near A.M., Desta B., Wang X., Hammond E.R. Disease and economic burden increase with systemic lupus erythematosus severity 1 year before and after diagnosis: a real-world cohort study, United States, 2004-2015. Lupus Sci Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.1136/lupus-2021-000503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jonasch E., Song Y., Freimark J., et al. Epidemiology and economic burden of von Hippel-Lindau disease-associated renal cell carcinoma in the United States. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2023;21:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2022.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kan H.J., Song X., Johnson B.H., Bechtel B., O’Sullivan D., Molta C.T. Healthcare utilization and costs of systemic lupus erythematosus in Medicaid. BioMed Res Int. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/808391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Karl F.M., Holle R., Bals R., et al. Costs and health-related quality of life in Alpha-1-Antitrypsin Deficient COPD patients. Respir Res. 2017;18:60. doi: 10.1186/s12931-017-0543-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kawalec P.P., Malinowski K.P. The indirect costs of systemic autoimmune diseases, systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis and sarcoidosis: a summary of 2012 real-life data from the Social Insurance Institution in Poland. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;15:667–673. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2015.1065733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khamashta M.A., Bruce I.N., Gordon C., et al. The cost of care of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) in the UK: annual direct costs for adult SLE patients with active autoantibody-positive disease. Lupus. 2014;23:273–283. doi: 10.1177/0961203313517407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kingswood J.C., Crawford P., Johnson S.R., et al. The economic burden of tuberous sclerosis complex in the UK: a retrospective cohort study in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. J Med Econ. 2016;19:1087–1098. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2016.1199432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knarborg M., Løkke A., Hilberg O., Ibsen R., Sikjaer M.G. Direct and indirect costs of systemic sclerosis and associated interstitial lung disease: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Respirology. 2022;27:341–349. doi: 10.1111/resp.14234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu X., Mao Y.H., He X.M., Zhang Y.J., Sun Y. Analysis on inpatient health expenditures of renal cell carcinoma in a Grade-A Tertiary Hospital in Beijing. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130:2447–2452. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.216412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lokhandwala T., Coutinho A.D., Bell C.F. Retrospective analysis of disease severity, health care resource utilization, and costs among patients initiating Belimumab for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Ther. 2021;43:1320–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.López-Bastida J., Linertová R., Oliva-Moreno J., Posada-de-la-Paz M., Serrano-Aguilar P. Social economic costs and health-related quality of life in patients with systemic sclerosis in Spain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2014;66:473–480. doi: 10.1002/acr.22167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Maroun R., Maunoury F., Benjamin L., Nachbaur G., Durand-Zaleski I. In-hospital economic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in France in the era of targeted therapies: analysis of the French National Hospital database from 2008 to 2013. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McCormick N., Marra C.A., Sadatsafavi M., Aviña-Zubieta J.A. Incremental direct medical costs of systemic lupus erythematosus patients in the years preceding diagnosis: a general population-based study. Lupus. 2018;27:1247–1258. doi: 10.1177/0961203318768882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyazaki C., Sruamsiri R., Mahlich J., Jung W. Treatment patterns and medical cost of systemic lupus erythematosus patients in Japan: a retrospective claims database study. J Med Econ. 2020;23:786–799. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2020.1740236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Morrisroe K., Stevens W., Sahhar J., et al. Quantifying the direct public health care cost of systemic sclerosis: A comprehensive data linkage study. Med (Baltim) 2017;96 doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000008503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Neeleman R.A., Wagenmakers M., Koole-Lesuis R.H., et al. Medical and financial burden of acute intermittent porphyria. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2018;41:809–817. doi: 10.1007/s10545-018-0178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Padala S.D., Lao C., Solanki K., White D. Direct and indirect health-related costs of systemic sclerosis in New Zealand. Int J Rheum Dis. 2022;25:1386–1394. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.14433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Petri M., Daly R.P., Pushparajah D.S. Healthcare costs of pregnancy in systemic lupus erythematosus: retrospective observational analysis from a US health claims database. J Med Econ. 2015/11/02;18:967–973. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2015.1066796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ram Poudel D., George M., Dhital R., Karmacharya P., Sandorfi N., Derk C.T. Mortality, length of stay and cost of hospitalization among patients with systemic sclerosis: results from the National Inpatient Sample. Rheumatol (Oxf Engl) 2018;57:1611–1622. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/key150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Prada S.I., Pérez A.M., Nieto-Aristizábal I., Tobón G.J. Increase in direct costs for health systems due to lupus nephritis: the case of Colombia. Einstein (São Paulo) 2022;20 doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2022AO6553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Qi X., Xu J., Shan L., et al. Economic burden and health related quality of life of ultra-rare Gaucher disease in China. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:358. doi: 10.1186/s13023-021-01963-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Quock T.P., Chang E., Munday J.S., D’Souza A., Gokhale S., Yan T. Mortality and healthcare costs in Medicare beneficiaries with AL amyloidosis. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7:1053–1062. doi: 10.2217/cer-2018-0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Quock T.P., Yan T., Chang E., Guthrie S., Broder M.S. Healthcare resource utilization and costs in amyloid light-chain amyloidosis: a real-world study using US claims data. J Comp Eff Res. 2018;7:549–559. doi: 10.2217/cer-2017-0100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sieluk J., Slejko J.F., Silverman H., Perfetto E., Mullins C.D. Medical costs of Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency-associated COPD in the United States. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:260. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soerensen A.V., Donskov F., Kjellberg J., et al. Health economic changes as a result of implementation of targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: national results from DARENCA study 2. Eur Urol. 2015;68:516–522. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Strzelczyk A., Rosenow F., Zöllner J.P., et al. Epidemiology, healthcare resource use, and mortality in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: a population-based study on German health insurance data. Seizure. 2021;91:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2021.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sun P., Liu Z., Krueger D., Kohrman M. Direct medical costs for patients with tuberous sclerosis complex and surgical resection of subependymal giant cell astrocytoma: a US national cohort study. J Med Econ. 2015;18:349–356. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2014.1001513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sundaram M., Song Y., Rogerio J.W., et al. Clinical and economic burdens of recurrence following nephrectomy for intermediate high- or high-risk renal cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results-Medicare data. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2022;28:1149–1160. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2022.22133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tanaka Y., Mizukami A., Kobayashi A., Ito C., Matsuki T. Disease severity and economic burden in Japanese patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: a retrospective, observational study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2018;21:1609–1618. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.13363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tanzer M., Tran C., Messer K.L., et al. Inpatient health care utilization by children and adolescents with systemic lupus erythematosus and kidney involvement. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65:382–390. doi: 10.1002/acr.21815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ungprasert P., Koster M.J., Cheungpasitporn W., Wijarnpreecha K., Thongprayoon C., Kroner P.T. Inpatient burden and association with comorbidities of polyarteritis nodosa: national Inpatient Sample 2014. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vogelzang N.J., Pal S.K., Ghate S.R., et al. Clinical and economic outcomes in elderly advanced renal cell carcinoma patients starting pazopanib or sunitinib treatment: a retrospective Medicare claims analysis. Adv Ther. 2017;34:2452–2465. doi: 10.1007/s12325-017-0628-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang H., Li M., Zou K., et al. Annual direct cost and Cost-Drivers of systemic lupus erythematosus: a multi-center cross-sectional study from CSTAR registry. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20 doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang X., Desai K., Agrawal N., et al. Characteristics, treatment patterns, healthcare resource use, and costs among pediatric patients diagnosed with neurofibromatosis type 1 and plexiform neurofibromas: a retrospective database analysis of a Medicaid population. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37:1555–1561. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1940907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhou Z., Fan Y., Tang W., et al. Economic burden among commercially insured patients with systemic sclerosis in the United States. J Rheumatol. 2019;46:920–927. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.180445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Park S.Y., Joo Y.B., Shim J., Sung Y.K., Bae S.C. Direct medical costs and their predictors in South Korean patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:1809–1815. doi: 10.1007/s00296-015-3344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.D’Souza A., Broder M.S., Bognar K., Chang E., Tarbox M.H., Quock T.P. Diagnostic amyloid light chain amyloidosis hospitalizations associated with high acuity and cost: analysis of the Premier Healthcare Database. J Comp Eff Res. 2022;11:1225–1230. doi: 10.2217/cer-2022-0141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chu W.C., Chiang L.L., Chan D.C., Wong W.H.S., Chan G.C.F. Prevalence, mortality and healthcare economic burden of tuberous sclerosis in Hong Kong: a population-based retrospective cohort study (1995-2018) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:264. doi: 10.1186/s13023-020-01517-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kim H., Cho S.K., Kim J.W., et al. An increased disease burden of autoimmune inflammatory rheumatic diseases in Korea. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2020;50:526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2019.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pollissard L., Shah A., Punekar R.S., Petrilla A., Pham H.P. Burden of illness among Medicare and non-Medicare US populations with acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Med Econ. 2021;24:706–716. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2021.1922262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Jogimahanti A.V., Kini A.T., Irwin L.E., Lee A.G. The cost-effectiveness of tocilizumab (Actemra) therapy in giant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2021;41:342–350. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ambavane A., Yang S., Atkins M.B., et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of treatment sequences for intermediate- to poor-risk advanced renal cell carcinoma. Immunotherapy. 2020;12:37–51. doi: 10.2217/imt-2019-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Amdahl J., Diaz J., Park J., Nakhaipour H.R., Delea T.E. Cost-effectiveness of pazopanib compared with sunitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2016;23:e340–e354. doi: 10.3747/co.23.2244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Amdahl J., Diaz J., Sharma A., Park J., Chandiwana D., Delea T.E. Cost-effectiveness of pazopanib versus sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the United Kingdom. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bensimon A.G., Zhong Y., Swami U., et al. Cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab with axitinib as first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36:1507–1517. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2020.1799771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Çakar E., Oniangue-Ndza C., Schneider R.P., et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Nivolumab Plus ipilimumab for the First-Line Treatment of Intermediate/Poor-Risk Advanced and/or Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma in Switzerland. Pharmacoecon Open. 2023;7:567–577. doi: 10.1007/s41669-023-00395-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Capri S., Porta C., Condorelli C., et al. An updated cost-effectiveness analysis of pazopanib versus sunitinib as first-line treatment for locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Italy. J Med Econ. 2020;23:1579–1587. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2020.1839240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chan A., Dang C., Wisniewski J., et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis comparing Pembrolizumab-Axitinib, Nivolumab-Ipilimumab, and sunitinib for treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45:66–73. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen J., Hu G., Chen Z., et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib in first-line advanced renal cell carcinoma in China. Clin Drug Investig. 2019;39:931–938. doi: 10.1007/s40261-019-00820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.De Groot S., Blommestein H.M., Redekop W.K., et al. Potential health gains for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma in daily clinical practice: a real-world cost-effectiveness analysis of sequential first- and second-line treatments. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Delea T.E., Amdahl J., Diaz J., Nakhaipour H.R., Hackshaw M.D. Cost-effectiveness of pazopanib versus sunitinib for renal cancer in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2015;21:46–54. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.1.46. 54a-b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Deniz B., Ambavane A., Yang S., et al. Treatment sequences for advanced renal cell carcinoma: a health economic assessment. PLoS One. 2019;14 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0215761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ding D., Hu H., Shi Y., et al. Cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib as first-line therapy in advanced renal cell carcinoma in the U.S. Oncologist. 2021;26:e290–e297. doi: 10.1002/ONCO.13522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gupta D., Singh A., Gupta N., et al. Cost-effectiveness of the first line treatment options for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in India. JCO Glob Oncol. 2023;9 doi: 10.1200/GO.22.00246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kim H., Goodall S., Liew D. Reassessing the cost-effectiveness of nivolumab for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma based on mature survival data, updated safety and lower comparator price. J Med Econ. 2021;24:893–899. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2021.1955540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kim S., Han S., Kim H., Suh H.S. Cost-effectiveness and value of information of cabozantinib treatment for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma after failure of prior therapy in South Korea. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2021;19:545–555. doi: 10.1007/s40258-021-00640-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li S., Li J., Peng L., Li Y., Wan X. Cost-effectiveness of nivolumab plus cabozantinib versus sunitinib as a first-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma in the United States. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.736860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Liao W., Lei W., Feng M., et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of first-line nivolumab plus cabozantinib for advanced renal cell carcinoma in the United States. Adv Ther. 2021;38:5662–5670. doi: 10.1007/s12325-021-01926-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lin J., Fang Q., Zheng X. Cost-effectiveness analysis of anlotinib versus sunitinib as first-line treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in China. PLoS One. 2023;18 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0281402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Lu P., Liang W., Li J., et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis: first-line avelumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:619. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.00619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Mason N.T., Joshi V.B., Adashek J.J., et al. Cost effectiveness of treatment sequences in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol Oncol. 2023;6:331–338. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2023.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.McCrea C., Johal S., Yang S., Doan J. Cost-effectiveness of nivolumab in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated in the United States. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2018;7:4. doi: 10.1186/s40164-018-0095-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Meng J., Lister J., Vataire A.L., Casciano R., Dinet J. Cost-effectiveness comparison of cabozantinib with everolimus, axitinib, and nivolumab in the treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma following the failure of prior therapy in England. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2018;10:243–250. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S159833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mihajlović J., Pechlivanoglou P., Sabo A., Tomić Z., Postma M.J. Cost-effectiveness of everolimus for second-line treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Serbia. Clin Ther. 2013;35:1909–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Nazha S., Tanguay S., Kapoor A., et al. Cost-utility of sunitinib versus pazopanib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Canada using real-world evidence. Clin Drug Investig. 2018;38:1155–1165. doi: 10.1007/s40261-018-0705-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Petrou P. Cost-effectiveness analysis of axitinib through a probabilistic decision model. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1233–1243. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1039982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Petrou P.K., Talias M.A. Cost-effectiveness of sorafenib compared to best supportive care in second line renal cell cancer from a payer perspective in Cyprus. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2014;14:131–138. doi: 10.1586/14737167.2014.873703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Pruis S.L., Aziz M.I.A., Pearce F., Tan M.H., Wu D.B.C., Ng K. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of sunitinib versus interferon-Alfa for First-Line Treatment of Advanced and/or Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma in Singapore. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2019;35:126–133. doi: 10.1017/S0266462319000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Raphael J., Sun Z., Bjarnason G.A., Helou J., Sander B., Naimark D.M. Nivolumab in the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a cost-utility analysis. Am J Clin Oncol. 2018;41:1235–1242. doi: 10.1097/COC.0000000000000451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Redig J., Dalén J., Harmenberg U., et al. Real-world cost-effectiveness of targeted therapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Sweden: a population-based retrospective analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:1289–1297. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S188849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Reinhorn D., Sarfaty M., Leshno M., et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of nivolumab and ipilimumab versus sunitinib in first-line intermediate- to poor-risk advanced renal cell carcinoma. Oncologist. 2019;24:366–371. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sarfaty M., Leshno M., Gordon N., et al. Cost effectiveness of nivolumab in advanced renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2018;73:628–634. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2017.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sharma V., Wymer K.M., Joyce D.D., et al. Cost-effectiveness of adjuvant pembrolizumab after nephrectomy for high-risk renal cell carcinoma: insights for patient selection from a markov model. J Urol. 2023;209:89–98. doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000002953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shay R., Nicklawsky A., Gao D., Lam E.T. A cost-effectiveness analysis of nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus pembrolizumab plus axitinib and versus avelumab plus axitinib in first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2021;19:370–370.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2021.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Vargas C., Balmaceda C., Rodríguez F., Rojas R., Giglio A., Espinoza M.A. Economic evaluation of sunitinib versus pazopanib and best supportive care for the treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma in Chile: cost-effectiveness analysis and a mixed treatment comparison. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2019;19:609–617. doi: 10.1080/14737167.2019.1580572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wan X., Zhang Y., Tan C., Zeng X., Peng L. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab vs sunitinib for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a cost-effectiveness analysis. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:491–496. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.7086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Wan X.M., Peng L.B., Ma J.A., Li Y.J. Economic evaluation of nivolumab as a second-line treatment for advanced renal cell carcinoma from US and Chinese perspectives. Cancer. 2017;123:2634–2641. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Wang Y., Wang H., Yi M., Han Z., Li L. Cost-effectiveness of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab or everolimus as first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.853901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Watson T.R., Gao X., Reynolds K.L., Kong C.Y. Cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab plus axitinib vs nivolumab plus ipilimumab as first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.16144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Wu B., Zhang Q., Sun J. Cost-effectiveness of nivolumab plus ipilimumab as first-line therapy in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:124. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0440-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Zhu J., Zhang T., Wan N., et al. Cost-effectiveness of pembrolizumab plus axitinib as first-line therapy for advanced renal cell carcinoma. Immunotherapy. 2020;12:1237–1246. doi: 10.2217/imt-2020-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhu Y., Liu K., Ding D., Peng L. First-Line lenvatinib Plus Pembrolizumab or everolimus versus sunitinib for Advanced Renal Cell Carcinoma: a United States-Based Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2023;21:417.e1–417.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2022.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Clark L.A., Whitmire S., Patton S., Clark C., Blanchette C.M., Howden R. Cost-effectiveness of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors versus angiotensin II receptor blockers as first-line treatment in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Med Econ. 2017;20:715–722. doi: 10.1080/13696998.2017.1311266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Erickson K.F., Chertow G.M., Goldhaber-Fiebert J.D. Cost-effectiveness of tolvaptan in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159:382–389. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Rombach S.M., Hollak C.E.M., Linthorst G.E., Dijkgraaf M.G.W. Cost-effectiveness of enzyme replacement therapy for Fabry disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013/02/19;(8):29. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.van Dussen L., Biegstraaten M., Hollak C.E.M., Dijkgraaf M.G.W. Cost-effectiveness of enzyme replacement therapy for type 1 Gaucher disease. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2014/04/14;(9):51. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-9-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Alsuwayegh A., Almaghlouth I.A., Almasaoud M.A., et al. Cost Consequence Analysis of Belimumab versus Standard of Care for the Management of systemic lupus erythematosus in Saudi Arabia: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20 doi: 10.3390/ijerph20031917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Bindra J., Chopra I., Hayes K., Niewoehner J., Panaccio M., Wan G.J. Cost-effectiveness of Acthar gel versus standard of care for the treatment of exacerbations in moderate-to-severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Adv Ther. 2023;40:194–210. doi: 10.1007/s12325-022-02332-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Otten T., Riemsma R., Wijnen B., et al. Belimumab for treating active autoantibody-positive systemic lupus erythematosus: an evidence review group perspective of a NICE single technology appraisal. Pharmacoeconomics. 2022;40:851–861. doi: 10.1007/s40273-022-01166-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Specchia M.L., de Waure C., Gualano M.R., et al. Health technology assessment of Belimumab: a new monoclonal antibody for the treatment of systemic lupus erythematosus. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/704207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Vandewalle B., Amorim M., Ramos D., et al. Value-based decision-making for orphan drugs with multiple criteria decision analysis: burosumab for the treatment of X-linked hypophosphatemia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37:1021–1030. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1904861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Donovan E.K., Xie F., Louie A.V., et al. Cost effectiveness analysis of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) versus stereotactic body radiotherapy (SBRT) for early stage renal cell carcinoma (RCC) Clin Genitourin Cancer. 2022;20:e353–e361. doi: 10.1016/j.clgc.2022.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]