Abstract

Mindfulness instruction comprising both formal (FM) and informal (IM) mindfulness practice is increasingly offered to university students. FM involves sustaining attention on thoughts, emotions and bodily sensations through structured practices, while IM involves incorporating mindfulness into daily activities. However, recent evidence suggests that FM may pose challenges for students with recent non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI), whereas the flexibility and brevity inherent in IM may be better tolerated. This randomized controlled trial compared a FM induction, IM induction and control task among university students with (n = 103) and without (n = 123) past‐year NSSI in terms of acceptability and pre‐post state mindfulness, stress and well‐being. Notably, results did not differ as a function of NSSI history. Two‐way ANOVAs revealed that only IM was consistently preferred over the control task. Furthermore, three‐way mixed ANOVAs revealed that—when assessed using brief Visual Analogue Scales—state well‐being increased in all conditions, state mindfulness increased after both IM and FM, and state stress only decreased after IM. Notably, these differences by condition appeared to be of short duration as they were not found with lengthier measures. Results highlight the potential promise of IM and the importance of measurement selection when assessing the transient effects of mindfulness inductions in research.

Keywords: mindfulness, non‐suicidal self‐injury, stress, university students, well‐being

INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, teaching mindfulness has become an important element in university campuses' resilience‐building programming (Dawson et al., 2020; Halladay et al., 2019). Mindfulness is commonly defined as the purposeful awareness and nonjudgmental acceptance of one's present moment experience (Kabat‐Zinn, 1994); within this broad definition is a multidimensional construct, including what one does when being mindful (e.g., awareness, observing, describing) as well as how one does it (nonjudging, nonreacting) (Baer et al., 2006). Standard mindfulness instruction typically includes teaching a combination of both formal and informal mindfulness strategies, where formal strategies involve setting aside a set of period of time to become nonjudgmentally aware of one's breath, bodily sensations, thoughts and/or emotions (e.g., a sitting meditation), while informal strategies involve the more flexible integration of mindful awareness and nonjudgmental acceptance into day‐to‐day activities (e.g., noticing the feeling of the water on one's hands while washing them; Crane et al., 2017). The aim of standard mindfulness instruction is to increase individuals' general tendency to be mindful (i.e., their dispositional mindfulness) by increasing the frequency with which they experience states of mindfulness (Kabat‐Zinn, 2013; Kiken et al., 2015). Greater dispositional mindfulness has been found to, in turn, lead to various mental health and well‐being benefits (Verhaeghen, 2021; Visted et al., 2015). Indeed, an ever‐growing body of literature demonstrates that standard mindfulness instruction has been found to be effective among the general university student population at decreasing stress, depression and anxiety, as well as improving resilience, well‐being and university adjustment (Dawson et al., 2020; Halladay et al., 2019).

However, a universal, one‐size‐fits‐all approach to mindfulness instruction may not be optimal in the university context, as recent evidence suggests that some students may respond differently to standard mindfulness instruction (Petrovic et al., 2022, Petrovic et al., 2023b; Ribeiro, 2020). This may be particularly true for university students with a history of non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI), defined as the deliberate destruction of one's body tissue in the absence of suicidal intent and for purposes not socially or culturally sanctioned (International Society for the Study of Self‐Injury, 2023). Specifically, individuals with lived experience of NSSI often report emotion regulation difficulties, elevated levels of self‐criticism, alexithymia (i.e., the inability to identify and describe one's emotional experiences) and a complex relationship with their body (Cipriano et al., 2017; Duggan et al., 2013; Greene et al., 2020; Muehlenkamp, 2012; Zelkowitz & Cole, 2019). Each of these factors may undermine the benefits of formal mindfulness, which often requires a prolonged focus on thoughts, emotions and bodily sensations.

For instance, in a recent experimental study by Petrovic et al. (2022), it was found that university students with a history of NSSI experienced a greater increase in their body awareness following a formal mindfulness induction (i.e., a body scan meditation) relative to students without such a history. Of note, mindfulness ‘inductions’ are brief, single‐session mindfulness practices aimed at inducing a mindful state in the participant. However, the nature of this response—including whether this heightened body awareness was perceived as pleasant or aversive—remained unclear. More recent findings suggest that a hyperawareness of thoughts, emotions and physical sensations during formal mindfulness practice may be perceived as aversive or upsetting among university students with a recent history of NSSI (Petrovic et al., 2023b). In particular, this heightened awareness led some students to fixate on chronic pain, feel physically numb or dissociate, experience intrusive negative thoughts or report feelings of anxiety during practice. These findings point to a need for more research exploring alternative approaches to fostering mindfulness (i.e., beyond formal practice) that may circumvent these challenges, to maximize the acceptability and efficacy of such interventions; we posit that this is particularly true among individuals with a history of NSSI.

Informal mindfulness strategies that are brief and unstructured may be more appropriate for university students with a history of NSSI since they are highly accessible and can be easily implemented within daily routine activities (Birtwell et al., 2019; Crane et al., 2017; Ribeiro, 2020). These characteristics of IM may be appealing for university student populations in general, who overwhelmingly report ‘lack of time’ as a barrier to their help‐seeking (Broglia et al., 2021; Dunley & Papadopoulos, 2019). Even within the general population, difficulty adhering to a regular practice of formal mindfulness is commonly reported, often due to challenges in being able to find time to practice regularly, or feeling frustrated with not ‘getting it right’ (Birtwell et al., 2019). Moreover, findings from a systematic review by Ribeiro (2020) suggest that informal mindfulness may be preferred by individuals experiencing difficulties with emotion regulation, which is often the case for those who engage in NSSI (see review by Wolff et al., 2019). In support of this argument, a recent qualitative study found that informal mindfulness practice was deemed particularly enjoyable and easy to implement into one's daily routine among university students with a history of NSSI (Petrovic et al., 2023b). Although this was a first study of its kind and conclusions are tentative, the authors suggested that encouraging its use may provide the best opportunity for students with lived experience of self‐injury to build a regular mindfulness practice and ultimately improve their emotion regulation. Furthermore, a growing body of research suggests that informal practice may have benefits in its own right including decreased stress, anxiety and depression, as well as increased state and dispositional mindfulness, positive affect and life satisfaction (Hanley et al., 2015; Hindman et al., 2015; Mettler et al., 2024; Shankland et al., 2020; Verger et al., 2021).

The present study

University students with a history of NSSI are particularly at‐risk of experiencing elevated levels of stress and difficulty coping in the university context (Ewing et al., 2019; Hamza et al., 2021). Therefore, these students stand to benefit greatly from mindfulness instruction that is adapted to their needs. While the benefits of mindfulness instruction for university students' mental health and adjustment have been well‐established (Dawson et al., 2020; Halladay et al., 2019), a paucity of work has considered person‐level heterogeneity in response to mindfulness instruction among this population. Notably, a recent qualitative study provided preliminary evidence that university students with a history of NSSI may have a preference for informal practices of mindfulness over formal ones (Petrovic et al., 2023b). However, the potential impacts of informal mindfulness on these students' mental health and well‐being remain unknown, and empirical evidence of the effectiveness of informal practice is needed before its use can be rightly emphasized. Nevertheless, to date, there have been no randomized controlled studies that have explored the relative effectiveness and acceptability of formal versus informal mindfulness among university students with or without a history of NSSI.

The objectives of the present randomized controlled trial were thus to compare the effectiveness (Objective 1) and acceptability (Objective 2) of a formal mindfulness (FM) induction, an informal mindfulness (IM) induction and an active control task in university students with versus without a recent history of NSSI. Effectiveness was inferred from pre‐post changes in state mindfulness, state stress and state well‐being, while acceptability was only assessed post‐intervention. Changes in state (as opposed to trait) mindfulness, stress and well‐being were explored given that mindfulness inductions are expected to impact these outcomes in‐the‐moment, whereas repeated instances of mindfulness practice would likely be needed to see trait‐level differences in these outcomes (Kabat‐Zinn, 2013; Kiken et al., 2015). It was expected that both the FM and IM inductions would be more effective (Hypothesis 1 [H1]) and acceptable (Hypothesis 2 [H2]) than the control task among all students. However, among those with a recent history of NSSI, the IM induction was also expected to be more effective (Hypothesis 3 [H3]) and acceptable (Hypothesis 4 [H4]) than the FM induction.

METHOD

The present randomized controlled trial obtained institutional Research Ethics Board approval and was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov prior to recruitment (ID NCT05608304). Abbreviated descriptions of this study's procedure and measures are provided below. However, a detailed report of the study design, interventions, randomization and allocation concealment processes, procedures to minimize bias, measure psychometrics and power analysis can be found in the proactively published study protocol (see Petrovic et al., 2023a).

Participants

Participants were students at a large Canadian university. Eligibility criteria to participate included (i) active enrolment at the host institution, (ii) being between 18 and 29 years of age and (iii) either reporting NSSI engagement on at least five separate days within the last year, a recency/frequency criterion that is aligned with the DSM‐5 diagnostic criteria for NSSI Disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), or reporting never having engaged in NSSI.

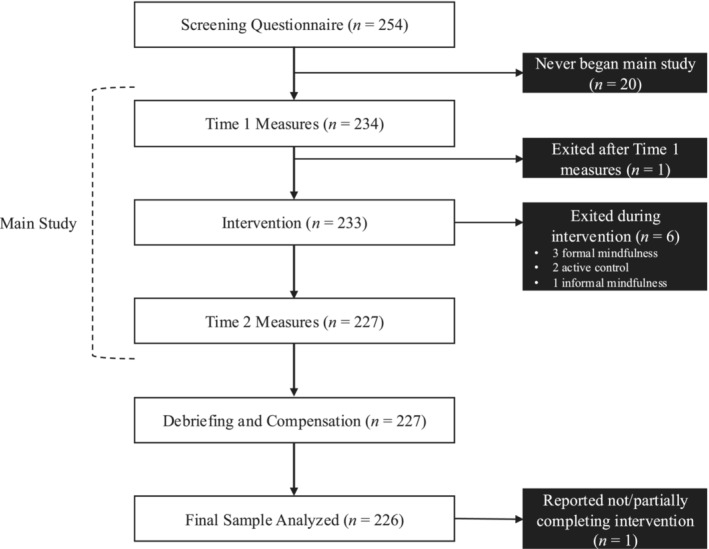

A priori power analyses with a desired power of .80 and accounting for an attrition rate of 20% revealed a minimum sample size of 204 participants to detect a medium‐sized effect. A total of 254 university students participated in the present study. However, 27 were lost to attrition, and one was omitted from analyses as they selected ‘no/partially’ in response to an item asking whether they completed the self‐regulation activity (i.e., their assigned experimental task) and did not elaborate on this response when prompted. A participant flow chart is provided in Figure 1. Attrition analyses comparing study completers to non‐completers on age, gender identity, and NSSI history (i.e., the demographic variables assessed within the screening questionnaire) revealed no significant group differences. The final sample thus consisted of 226 university students (M age = 21. 57 years, SD = 3.04; 82.3% women), 103 of whom reported a history of NSSI on at least five separate days within the last year and 123 of whom reported never having engaged in NSSI. Participants were randomly assigned to either the FM induction, IM induction or active control task based on their NSSI history (NSSI/no‐NSSI). As such, six clusters of participants were created; demographic information for all clusters is provided in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow chart.

TABLE 1.

Participant demographics (N = 226).

| NSSI | No‐NSSI | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Formal (n = 34) | Informal (n = 34) | Control (n = 35) | Formal (n = 41) | Informal (n = 41) | Control (n = 41) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Gender identity | ||||||||||||

| Woman | 27 | 79.4 | 27 | 79.4 | 27 | 77.1 | 35 | 85.4 | 35 | 85.4 | 35 | 85.4 |

| Man | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 8.8 | 4 | 11.4 | 6 | 14.6 | 6 | 14.6 | 6 | 14.6 |

| Non‐binary, gender fluid or two‐spirit | 4 | 11.7 | 4 | 11.7 | 4 | 11.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Sexual orientation | ||||||||||||

| Heterosexual | 12 | 35.3 | 15 | 44.1 | 14 | 42.4 | 35 | 85.4 | 31 | 75.6 | 32 | 78.0 |

| Gay | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.0 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 4.9 |

| Lesbian | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 8.8 | 3 | 9.1 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.4 |

| Bisexual | 13 | 38.2 | 13 | 38.2 | 8 | 24.2 | 3 | 7.3 | 8 | 19.5 | 3 | 7.3 |

| Asexual | 2 | 5.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 9.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.4 |

| Questioning | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 3.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 4.9 | 2 | 4.9 |

| Other | 2 | 5.9 | 2 | 5.9 | 3 | 9.1 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Population group | ||||||||||||

| Arab | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 4.9 | 2 | 4.9 | 1 | 2.4 |

| Black | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Chinese, Japanese or Korean | 8 | 23.5 | 8 | 23.5 | 6 | 17.1 | 8 | 19.5 | 13 | 31.6 | 9 | 22.0 |

| Latin American | 3 | 8.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.9 | 3 | 7.3 | 3 | 7.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| South Asian (ex. Indian, Pakistani) | 2 | 5.9 | 2 | 5.9 | 3 | 5.7 | 3 | 7.3 | 2 | 4.9 | 5 | 12.2 |

| Southeast Asian (e.g., Thai, Filipino) | 1 | 2.9 | 2 | 5.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.4 |

| West Asian (e.g., Iranian, Afghan) | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 2.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| White | 15 | 44.1 | 18 | 52.9 | 18 | 51.4 | 18 | 43.9 | 19 | 46.3 | 20 | 48.8 |

| Other | 2 | 5.9 | 2 | 5.9 | 4 | 11.4 | 5 | 12.2 | 2 | 4.9 | 5 | 12.2 |

| Mean age (SD) | ||||||||||||

| 21.2 (1.8) | 21.6 (2.5) | 21.3 (3.1) | 22.5 (3.8) | 21.0 (2.7) | 21.8 (3.6) | |||||||

Procedure

Following institutional Research Ethics Board approval, participants were recruited through electronically distributed recruitment flyers (via university listservs and social media pages) as well as through recruitment emails sent to an existing database of students who agreed to be contacted for future studies by our research team. Interested students completed an online screening questionnaire to determine eligibility (described in Section 2.3 below). Eligible participants within each group (NSSI, no‐NSSI) were matched on gender before being randomly assigned to one of the three study conditions using a 1:1:1 allocation ratio: a FM induction, an IM induction or an active control condition. Participants then received a personalized link to an online survey that reflected their condition assignment and were instructed to complete the survey on their own time within a 2‐week period. In an effort to blind participants to their assigned condition, all three experimental tasks were vaguely described as ‘self‐regulation activities’.

All data collection procedures were conducted virtually. In a single session of approximately 20 min, participants first completed pre‐intervention measures of state mindfulness, state stress and state well‐being. Participants then completed a brief FM induction, IM induction or active control task. The FM induction consisted of a 10‐min audio recording of a sitting meditation, guiding the participant to consciously and repeatedly bring their attention to their breath and inner experience with nonjudgmental acceptance (Kabat‐Zinn, 2013). The IM induction consisted of an audio recording of informal directives, guiding the participant through the completion of four routine tasks (washing hands, drinking water, laying down, listening to music) with focused, nonjudgmental attention on the thoughts, emotions and/or physical sensations that arose as they did this over the course of 10 min. Participants in the active control condition were instructed to download a single‐page document containing 100 letters, numbers and symbols and a grid of 100 boxes. Following along with an audio recording, participants were instructed to place all of the characters in the grid in a specific order over the course of 10 min. Transcripts of all three intervention audio files are provided in File S2. All participants then completed the same survey completed at pre‐intervention once again, with added acceptability questionnaires. Participants were compensated $20 via e‐transfer following their participation.

Measures

Screening questionnaire

A screening questionnaire was used to confirm students' eligibility to participate and included questions about age, gender identity and NSSI history. Items used to assess NSSI history included, ‘Have you ever engaged in non‐suicidal self‐injury (the deliberate destruction of one's bodily tissue, e.g., self‐cutting, self‐hitting, burning, bruising, scratching, etc.), without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially or culturally sanctioned (e.g., body modification, tattoos, body piercings)?’ and, ‘Have you engaged in non‐suicidal self‐injury on at least 5 separate days within the past 12 months?’ Response options for both items were Yes and No. Students had to report no history of NSSI (No to both items) or report a history of NSSI that was consistent with the definition and frequency/recency requirements used in the present study (Yes to both items) to be eligible to participate.

Primary outcome

Pre‐post state mindfulness (Visual Analogue Scale [VAS])

A Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), a self‐report measure commonly used in induction research (e.g., Hessler‐Kaufmann et al., 2020), was used to assess state mindfulness. The VAS is an adaptable, single‐item measure, consisting of a simple one‐dimensional line with endpoints defining extreme values that is widely used in the measurement of health and mental health states (e.g., pain, stress). For the purposes of this study, five VAS items (one for each facet of mindfulness as described by Baer et al., 2006: observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonjudging and nonreactivity) were created and were modelled on items in the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). Each VAS item consisted of a line with endpoints labelled as (0) Not true at all and (10) Completely true. Participants were asked to ‘Indicate the extent to which each statement below accurately reflects your experience in this moment on the corresponding ruler’. A sum score was calculated for each time point (pre‐ and post‐intervention), whereby a higher sum score indicates greater overall state mindfulness at that time point (possible range: 0–50). This researcher‐developed measure, along with a researcher‐developed adaptation of the FFMQ (described below), were both used to assess state mindfulness due to the absence of existing measures of state mindfulness that assess these specific facets and given the evidence of their relative contributions to overall levels of mindfulness (Baer et al., 2006). Moreover, all VAS measures employed in the present study were piloted with a small sample (n = 10) of undergraduate and graduate students to ensure that the items and their respective response options were easily understood by participants. The VAS for state mindfulness had good internal consistency both pre‐ (α = .81) and post‐intervention (α = .84) in the present study.

Secondary outcomes

Pre‐post state mindfulness (FFMQ‐24 adapted)

An adaptation of the FFMQ‐24 (Baer et al., 2006; Medvedev et al., 2018) was also used to measure state mindfulness. Similar to the original FFMQ‐24, this measure consisted of five subscales each assessing a specific facet of state mindfulness (observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonjudging and nonreactivity), although items were adapted to represent experiences in the present moment (rather than more generally). Items included, ‘I am ‘running on automatic’ without much awareness of what I'm doing’, and, ‘I could easily find the words to describe my feelings’. Participants rated each item on a 5‐point Likert scale ranging from (1) Not true at all to (5) Very true. A sum score was calculated for each time point (pre‐ and post‐intervention), whereby a higher sum score indicates greater overall state mindfulness at that time point (possible range: 24–120). This adaptation of the FFMQ‐24 had high internal consistency both pre‐ and post‐intervention in the present study (α's = .88 and .87, respectively).

Pre‐post state stress (VAS)

A VAS was used to assess state stress (Lesage et al., 2012).

Participants were asked to ‘Indicate how stressed you feel in this moment’ on a ruler ranging from (0) Not stressed at all to (10) As stressed as could be. The VAS thus yielded a single subjective stress score from 0 to 10, where a higher score indicates greater state stress.

Pre‐post state stress (9‐item Psychological Stress Measure [PSM‐9])

The PSM‐9 (Lemyre & Tessier, 2003) was also used to assess state stress. The PSM‐9 consists of items such as, ‘I feel rushed; I do not seem to have enough time’, and, ‘I feel stressed’. Items are rated on an 8‐point Likert scale ranging from Not at all (1) to Extremely (8). For this study, ‘in this moment’ was provided as the timeframe of interest. A higher sum score on the PSM‐9 indicates greater state stress (possible range: 9–72). The PSM‐9 demonstrated high internal consistency in the present study both pre‐ and post‐intervention (both α's = .88).

Pre‐post state well‐being (VAS)

A VAS was used to assess state well‐being. Specifically, six VAS items were created for this study, which are aligned with Diener's (1984) tripartite model of subjective well‐being comprising positive affect, negative affect and life satisfaction. However, as this measure was developed to assess well‐being in‐the‐moment, its items probe positive and negative affective states rather than life satisfaction (which was not expected to change in response to a 10‐min experimental task). Items were broadly modelled on those in the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988), which is commonly used to assess positive and negative affect in the context of Diener's (1984) tripartite model, but were adapted to reflect affective states that were expected to change in response to our experimental tasks. Participants were thus asked to ‘Indicate how [calm/good/focused/self‐critical/distracted/frustrated] you feel in this moment’ on a ruler ranging from 0 to 10. A sum score was calculated, whereby a higher score indicates greater overall state well‐being at that time point (possible range: 0–60). The VAS for state well‐being had good internal consistency both pre‐ and post‐intervention in the present study (α's = .80 and .84, respectively).

Post‐intervention acceptability (Theoretical Framework of Acceptability [TFA] Questionnaire)

The TFA Questionnaire was used to assess acceptability (Sekhon et al., 2022). This measure assesses the seven components of the TFA (affective attitude, burden, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, perceived effectiveness and self‐efficacy), is adaptable and can be used to evaluate a variety of healthcare interventions including mental healthcare (Sekhon et al., 2017). It consists of seven items, each pertaining to one of the components listed above, as well as an eighth item that assesses general acceptability. For the purpose of this study, the item pertaining to opportunity costs was omitted as it was deemed not applicable. In its place, an eighth item was created and added to this measure, reflecting concerns around the participant's assigned intervention (i.e., Do you have any concerns around your use of this self‐regulation strategy?). All items were rated on 5‐point Likert scales. A mean score was calculated whereby a higher mean indicates a higher level of acceptability. The TFA Questionnaire had good internal consistency in the present study (α = .82).

Post‐intervention acceptability (Intrinsic Motivation Inventory [IMI])

The IMI (Ryan, 1982) is a measure intended to assess participants' subjective experience of a target activity in experimental research. It measures participants' interest/enjoyment as well as perceptions of competence, autonomy, value/usefulness, effort and pressure/tension felt while performing a given activity, thus yielding six subscales. Ryan (1982) recommends that researchers use the subscales that are most relevant to their respective experimental activity, as the inclusion or exclusion of specific subscales has not been shown to negatively impact the psychometric properties of the overall scale. For the purposes of this study, four subscales of this measure were thus used to also assess acceptability from a self‐determination theory perspective, which may be relevant to the subjective experience of FM versus IM activities (Petrovic et al., 2023b): interest/enjoyment (five items; e.g., ‘I enjoyed doing this activity very much’), perceived competence (five items; e.g., ‘I am satisfied with my performance on this activity’), perceived autonomy (six items; e.g., ‘I believe I had some choice in how I went about doing this activity’) and value/usefulness (seven items; e.g., ‘I believe this activity could be of some value to me’). All items were rated on a 7‐point Likert scale ranging from Not at all true (1) to Very true (7). A mean score was calculated, whereby a higher mean indicates a higher level of acceptability. The IMI had excellent internal consistency in the present study (α = .94).

Supplemental outcomes

Although not included in the original data analysis protocol, state mindfulness was also assessed in terms of its five facets separately (i.e., observing, describing, acting with awareness, nonjudging, nonreactivity) as measured by both the VAS for state mindfulness and the FFMQ‐24 adapted. For the VAS, the single‐item score for each mindfulness facet (on a scale from 0 to 10) was used at each time point. For the FFMQ‐24 adapted, a sum score was calculated for each facet of mindfulness at each time point. Reliability statistics for the FFMQ‐24 adapted are provided in File S3.

Data analytic plan

Preliminary analyses

Separate Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFAs) were first conducted to confirm the single‐factor structures of all of the researcher‐developed/adapted measures used in this study (i.e., all but the PSM‐9). CFAs were conducted using pre‐intervention items, with the exception of those conducted for the two acceptability measures (which were only administered post‐intervention). Several goodness of fit indices were used, including the χ2/df ratio (≤2), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; ≤.06), comparative fit index (CFI; ≥.90), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI; ≥.90) and standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR; ≤.08) (Meyers et al., 2017; West et al., 2012).

Primary analysis: Objective 1

Mixed design three‐way (Group*Condition*Time) ANOVAs were conducted to compare effectiveness across groups (NSSI, no‐NSSI), conditions (IM induction, FM induction, active control) and time (pre‐, post‐intervention). Specifically, five separate analyses were conducted for (1) state mindfulness (VAS), (2) state mindfulness (FFMQ‐24 adaptation), (3) state stress (VAS), (4) state stress (PSM‐9) and (5) state well‐being (VAS). Simple main effects analyses were conducted to probe significant interactions, while follow‐up univariate analyses and pairwise comparisons were conducted to determine where group differences lied, with and without a Bonferroni correction to account for familywise error.

Primary analysis: Objective 2

Between‐subjects two‐way ANOVAs (Group*Condition) were conducted to compare mean levels of post‐intervention acceptability across groups (NSSI, no‐NSSI) and conditions (IM induction, FM induction, active control) as measured by (1) the TFA Questionnaire and (2) the IMI. A Bonferroni correction was applied using the same approach as for Objective 1.

Supplemental analyses

The same analytic approach used to assess Objective 1 was used to compare effectiveness across groups (NSSI, no‐NSSI), conditions (IM induction, FM induction, active control) and time (pre‐, post‐intervention) in terms of impacts on the five facets of state mindfulness, as measured by both the VAS for state mindfulness and the FFMQ‐24 adapted.

RESULTS

Preliminary analyses

Results from separate CFAs confirmed the single‐factor structures of all researcher‐developed/adapted measures used. Results of these CFAs are presented in File S1.

Primary analysis: Objective 1

As noted earlier (see Section 2.4), pairwise comparisons for all primary analyses were conducted with and without a Bonferroni correction. All results are reported with the correction, in the interest of being conservative and as the patterns of significance did not differ as a function of whether the correction was applied or not. In the sole instance where the pattern did differ as a function of the correction, both results are reported. Observed means and standard deviations of all study variables at each level of group, condition and time are found in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Observed means and standard deviations of all study variables at each level of group, condition and time.

| Time 1 | Time 2 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSSI | No‐NSSI | Combined | NSSI | No‐NSSI | Combined | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Mindfulness (VAS) | ||||||||||||

| Formal | 31.03 | 9.90 | 36.02 | 6.89 | 33.76 | 8.69 | 33.85 | 7.16 | 38.46 | 7.50 | 36.37 | 7.66 |

| Informal | 30.71 | 8.87 | 36.12 | 6.65 | 33.67 | 8.15 | 35.32 | 7.98 | 39.32 | 6.99 | 37.51 | 7.67 |

| Control | 31.31 | 8.22 | 36.07 | 8.31 | 33.88 | 8.56 | 31.69 | 7.53 | 34.20 | 7.63 | 33.04 | 7.64 |

| Mindfulness (FFMQ) | ||||||||||||

| Formal | 76.68 | 17.05 | 87.51 | 12.48 | 82.53 | 15.63 | 88.10 | 13.31 | 93.38 | 11.98 | 90.95 | 12.80 |

| Informal | 78.14 | 16.09 | 87.64 | 12.69 | 83.33 | 15.00 | 86.41 | 12.14 | 94.60 | 12.47 | 90.89 | 12.91 |

| Control | 80.02 | 10.10 | 83.10 | 11.56 | 81.68 | 10.95 | 86.09 | 11.90 | 87.21 | 11.88 | 86.70 | 11.82 |

| Stress (VAS) | ||||||||||||

| Formal | 6.97 | 1.80 | 5.41 | 2.21 | 6.12 | 2.17 | 5.12 | 2.29 | 4.02 | 2.63 | 4.52 | 2.53 |

| Informal | 5.85 | 2.46 | 5.46 | 2.54 | 5.64 | 2.50 | 3.88 | 2.43 | 3.46 | 2.63 | 3.65 | 2.53 |

| Control | 6.03 | 1.89 | 6.17 | 2.45 | 6.11 | 2.19 | 5.17 | 2.24 | 5.20 | 2.57 | 5.18 | 2.41 |

| Stress (PSM‐9) | ||||||||||||

| Formal | 47.47 | 13.12 | 39.93 | 12.81 | 43.35 | 13.41 | 37.76 | 12.49 | 32.07 | 11.80 | 34.65 | 12.37 |

| Informal | 44.44 | 12.99 | 36.17 | 11.96 | 39.92 | 13.03 | 36.18 | 10.72 | 29.41 | 11.69 | 32.48 | 11.69 |

| Control | 46.59 | 9.44 | 41.38 | 11.78 | 43.77 | 11.01 | 39.68 | 10.91 | 36.45 | 12.54 | 37.93 | 11.85 |

| Well‐being (VAS) | ||||||||||||

| Formal | 27.47 | 11.90 | 33.46 | 9.31 | 30.75 | 10.91 | 35.41 | 8.83 | 40.49 | 9.51 | 38.19 | 9.49 |

| Informal | 29.59 | 10.40 | 34.71 | 9.93 | 32.39 | 10.40 | 37.82 | 9.28 | 42.05 | 9.35 | 40.13 | 9.50 |

| Control | 29.23 | 8.47 | 30.83 | 10.33 | 30.09 | 9.49 | 34.20 | 9.19 | 35.66 | 11.15 | 34.99 | 10.25 |

| Acceptability (TFA) | ||||||||||||

| Formal | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.82 | 0.54 | 4.07 | 0.53 | 3.96 | 0.55 |

| Informal | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 4.01 | 0.49 | 4.25 | 0.41 | 4.14 | 0.46 |

| Control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 3.84 | 0.68 | 3.78 | 0.61 | 3.81 | 0.64 |

| Acceptability (IMI) | ||||||||||||

| Formal | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 4.39 | 1.12 | 4.79 | 1.08 | 4.61 | 1.11 |

| Informal | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 4.67 | 0.96 | 4.87 | 1.13 | 4.78 | 1.05 |

| Control | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | 4.10 | 1.11 | 4.18 | 1.10 | 4.14 | 1.10 |

Abbreviations: FFMQ, Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire; IMI, Intrinsic Motivation Inventory; PSM‐9, 9‐item Psychological Stress Measure; TFA, Theoretical Framework of Acceptability; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Pre‐post state mindfulness (VAS)

The Group*Condition*Time, Group*Condition and Group*Time interactions were all nonsignificant, although there was a significant Condition*Time interaction (see Table 3 for a detailed report of all three‐way ANOVA results). Simple main effects analyses revealed a significant simple main effect of condition post‐intervention only (p = .001), whereby state mindfulness was higher in both the FM (p = .027) and IM (p = .001) conditions post‐intervention relative to the active control (consistent with H1 but inconsistent with H3 given lack of group differences). There was also a significant simple main effect of time within the FM and IM conditions only, whereby state mindfulness increased from pre‐post‐intervention in the FM (p = .001) and IM (p < .001) conditions. Finally, there was a significant main effect of group, whereby students with a history of NSSI reported lower state mindfulness than those without a history, regardless of condition or time (p < .001).

TABLE 3.

Results of three‐way and two‐way ANOVAs across all outcomes and measures.

| Outcome (measure) | Effect | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness (VAS) | Condition*group*time | F(2, 220) = 0.35, p = .706, η p 2 = .00 |

| Group*time | F(1, 220) = 2.18, p = .141, η p 2 = .01 | |

| Condition*time | F(2, 220) = 217.68, p < .001, η p 2 = .08 | |

| Group*condition | F(2, 220) = 15.79, p = .160, η p 2 = .00 | |

| Group | F(1, 220) = 21.86, p < .001, η p 2 = .09 | |

| Condition | F(2, 220) = 1.73, p = .180, η p 2 = .00 | |

| Time | F(1, 220) = 17.75, p < .001, η p 2 = .08 | |

| Mindfulness (FFMQ) | Condition*group*time | F(2, 217) = 1.00, p = .371, η p 2 = .01 |

| Group*time | F(1, 217) = 4.94, p = .027, η p 2 = .02 | |

| Condition*time | F(2, 217) = 2.54, p = .082, η p 2 = .02 | |

| Group*condition | F(2, 217) = 1.77, p = .173, η p 2 = .02 | |

| Group | F(1, 217) = 15.70, p < .001, η p 2 = .07 | |

| Condition | F(2, 217) = 1.06, p = .350, η p 2 = .01 | |

| Time | F(1, 217) = 115.68, p < .001, η p 2 = .35 | |

|

Stress (VAS) |

Condition*group*time | F(2, 220) = 0.46, p = .629, η p 2 = .00 |

| Group*time | F(1, 220) = 0.16, p = .693, η p 2 = .00 | |

| Condition*time | F(2, 220) = 11.08, p = .004, η p 2 = .05 | |

| Group*condition | F(2, 220) = 2.05, p = .131, η p 2 = .02 | |

| Group | F(1, 220) = 3.63, p = .058, η p 2 = .02 | |

| Condition | F(2, 220) = 4.11, p = .018, η p 2 = .04 | |

| Time | F(1, 220) = 129.45, p < .001, η p 2 = .37 | |

|

Stress (PSM‐9) |

Condition*group*time | F(2, 218) = 0.02, p = .982, η p 2 = .00 |

| Group*time | F(1, 218) = 2.85, p = .093, η p 2 = .01 | |

| Condition*time | F(2, 218) = 2.45, p = .089, η p 2 = .02 | |

| Group*condition | F(2, 220) = 0.42, p = .655, η p 2 = .00 | |

| Group | F(1, 220) = 16.43, p < .001, η p 2 = .07 | |

| Condition | F(2, 220) = 2.98, p = .053, η p 2 = .03 | |

| Time | F(1, 218) = 196.20, p < .001, η p 2 = .47 | |

| Well‐being (VAS) | Condition*group*time | F(2, 220) = 0.06, p = .946, η p 2 = .00 |

| Group*time | F(1, 220) = 0.36, p = .550, η p 2 = .00 | |

| Condition*time | F(2, 220) = 2.85, p = .060, η p 2 = .03 | |

| Group*condition | F(2, 220) = 1.04, p = .357, η p 2 = .01 | |

| Group | F(1, 220) = 10.65, p = .001, η p 2 = .05 | |

| Condition | F(2, 220) = 2.95, p = .054, η p 2 = .03 | |

| Time | F(1, 220) = 153.00, p < .001, η p 2 = .41 | |

|

Acceptability (TFA) |

Group*condition | F(2, 220) = 1.98, p = .141, η p 2 = .02 |

| Group | F(1, 220) = 3.82, p = .052, η p 2 = .02 | |

| Condition | F(2, 220) = 6.40, p = .002, η p 2 = .06 | |

|

Acceptability (IMI) |

Group*condition | F(2, 220) = 0.39, p = .675, η p 2 = .00 |

| Group | F(1, 220) = 2.47, p = .118, η p 2 = .01 | |

| Condition | F(2, 220) = 6.60, p = .002, η p 2 = .06 |

Abbreviations: FFMQ, Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire; IMI, Intrinsic Motivation Inventory; PSM‐9, 9‐item Psychological Stress Measure; TFA, Theoretical Framework of Acceptability; VAS, Visual Analogue Scale.

Pre‐post state mindfulness (FFMQ‐24 adapted)

The Group*Condition*Time, Condition*Time and Group*Condition interactions were all nonsignificant, although there was a significant Group*Time interaction. Simple main effects analyses revealed a significant simple main effect of group pre‐ and post‐intervention, whereby students with a history of NSSI reported lower state mindfulness than those without such a history pre‐ (p < .001) and post‐intervention (p = .004). There was also a significant simple main effect of time within all three conditions, whereby state mindfulness increased from pre‐post‐intervention (all p's < .001; inconsistent with H1 and H3).

Pre‐post state stress (VAS)

The Group*Condition*Time, Group*Time and Group*Condition interactions were all nonsignificant, although there was a significant Condition*Time interaction. Simple main effects analyses revealed a significant simple main effect of condition post‐intervention only (p = .001), whereby state stress was lower in the IM condition post‐intervention relative to the active control (p < .001). Without a Bonferroni correction, state stress was also lower in the IM condition post‐intervention relative to the FM condition (p = .029), although this difference is nonsignificant when the correction is applied (p = .086). Further, there was a significant simple main effect of time within all three conditions, whereby state stress decreased from pre‐post‐intervention within each (all p's < .001). Overall, these results are partially consistent with H1 and H3.

Pre‐post state stress (PSM‐9)

The Group*Condition*Time, Group*Time, Condition*Time and Group*Condition interactions were all nonsignificant. However, there was a significant main effect of group, whereby students with a history of NSSI reported higher state stress than those without a history, regardless of condition or time point (p < .001). There was also a significant main effect of time, whereby state stress decreased for all from pre‐post‐intervention, regardless of group or condition (p < .001; inconsistent with H1 and H3).

Pre‐post state well‐being (VAS)

The Group*Condition*Time, Group*Time, Condition*Time and Group*Condition interactions were all nonsignificant. However, there was a significant main effect of group, whereby students with a history of NSSI reported lower state well‐being than those without a history, regardless of condition or time point (p < .001). There was also a significant main effect of time, whereby state well‐being decreased for all from pre‐post‐intervention, regardless of group or condition (p < .001; inconsistent with H1 and H3).

Primary analysis: Objective 2

Post‐intervention acceptability (TFA Questionnaire)

The Group*Condition interaction was nonsignificant (see Table 3 for all two‐way ANOVA results). However, there was a significant main effect of condition, whereby acceptability was higher in the IM condition (p < .001) but not the FM condition (p = .218) relative to the active control (partially consistent with H2). There were no significant differences between the FM and IM conditions (p = .102; inconsistent with H4). There was no significant main effect of group (p = .052).

Post‐intervention acceptability (IMI)

The Group*Condition interaction was nonsignificant, although there was a significant main effect of condition, whereby acceptability was higher in the IM (p = .001) and FM (p = .026) conditions relative to the active control (consistent with H2 but inconsistent with H4). There was no significant main effect of group (p = .118).

Supplemental analyses

Results of supplemental analyses are described in detail in File S3. To summarize, when assessed using the VAS for state mindfulness, significant Condition*Time interactions were found for observing, describing and acting with awareness. For observing, this interaction was in favour of both the FM and IM conditions over the control condition without a Bonferroni correction, but in favour only of the IM condition over the control condition with the correction. For describing, this interaction was in favour of the IM condition over the control condition. For acting with awareness, this interaction was in favour of both the FM and IM conditions over the control condition in terms of the simple main effect of condition but was in favour only of the FM condition over the control condition in terms of the simple main effect of time. Finally, a significant Group*Time interaction was also found for nonjudging, whereby those with a history of NSSI reported a steeper increase over time relative to those without a history. All other significant effects were constrained to group effects (favouring those without a history of NSSI) and time effects (reflecting increases over time).

When assessed using the FFMQ‐24 adapted, a significant Condition*Time interaction was only found for observing, favouring both the FM and IM conditions over the control condition. There was also a significant Group*Time interaction for nonjudging, whereby those with a history of NSSI reported a steeper increase over time relative to those without a history. All other significant effects were constrained to group effects (favouring those without a history of NSSI) and time effects (reflecting increases over time).

DISCUSSION

This randomized controlled trial sought to compare the effectiveness (Objective 1) and acceptability (Objective 2) of a FM induction, an IM induction and a control task among university students with and without a recent history of NSSI. Patterns of findings were expected to differ between both groups of students. It was expected that the FM and IM inductions would be more effective (H1) and acceptable (H2) than the control task among all students. However, among those with a recent history of NSSI, the IM induction was also expected to be more effective (H3) and acceptable (H4) than the FM induction.

Effectiveness of formal and informal mindfulness inductions

Counter to our expectations, patterns of findings for both effectiveness and acceptability seldom differed between university students with and without a recent history of NSSI. For all students, when assessed using VAS scales, both the FM and IM inductions were found to be more effective than a control task at increasing state mindfulness (with a moderate effect size), while only the IM induction was more effective than a control task at decreasing state stress (with a small effect size). The IM induction was also more effective than the FM induction at decreasing state stress when a Bonferroni correction was not applied to the results. These results partially support our hypotheses (H1, H3); although IM was expected to be more effective than both FM and a control task among students with a recent history of NSSI, it was not expected to have any significant advantage over FM for students without such a history. However, the current findings suggest that IM may be more effective than FM where the goal is to both increase mindfulness and decrease stress in‐the‐moment, and that this potential advantage of IM holds true for all university students regardless of NSSI history. For the general university student population, these results extend previous research, which documented numerous benefits of practicing IM even in the absence of FM but had not conducted a head‐to‐head comparison of IM and FM in isolation from one another (e.g., Hanley et al., 2015; Hindman et al., 2015).

Counter to our hypotheses (H1, H3), when lengthier measures of state mindfulness and state stress were used (i.e., the adapted FFMQ‐24 and the PSM‐9, respectively), significant pre‐post changes were largely confined to time effects, whereby state mindfulness increased and state stress decreased from pre‐post‐intervention for all participants regardless of their assigned condition (with large effect sizes). The main exception to this pattern of findings was that an interaction between group and time emerged for state mindfulness when it was assessed using the adapted FFMQ‐24, revealing that the increase in state mindfulness across conditions was slightly more pronounced for those with a history of NSSI relative to those without one (albeit with a small effect size). One possible explanation for the discrepancy in our findings that emerged as a function of measurement selection may be that lengthier measures provided more time for a placebo effect to emerge among participants in the active control group. As noted earlier, the experimental tasks to be completed were all vaguely described as ‘self‐regulation activities’ to participants until the study conclusion regardless of their assigned condition, in an effort to blind participants to the nature of their condition and thus reduce the likelihood of performance bias. As participants were completing the lengthier measures of state mindfulness and state stress (as opposed to the VAS scales), they may have had more time to reflect on the fact that they just completed a ‘self‐regulation’ activity and their responses may have been biased in alignment with anticipated effects. Taken together, these results therefore highlight the importance of measurement selection when the research aim is to probe the short‐lived effects of mindfulness inductions and suggest that VAS scales may be an optimal measurement tool in this context. Indeed, VAS scales have demonstrated sound psychometric properties in addition to their ease of administration when it has been used to measure psychological constructs such as state stress and state anxiety (Abend et al., 2014; Lesage et al., 2012).

It is also worth noting that exploring effectiveness in terms of intervention impacts on the five facets of mindfulness separately revealed interesting albeit mixed findings. Findings from the VAS for state mindfulness suggest that observing, describing and acting with awareness were particularly positively impacted by the mindfulness inductions, although whether effects were mostly in favour of the FM or IM induction appeared to differ by facet. In contrast, only observing significantly improved, in response to both the FM and IM inductions, when assessed using a lengthier measure of state mindfulness (i.e., the FFMQ‐24 adapted). Interestingly, across both measures of state mindfulness, nonjudging appeared to increase more rapidly among those with a history of NSSI relative to those without such a history (across all conditions). Overall, findings are consistent with previous studies, which have demonstrated that mindfulness interventions tend to impact the facets of mindfulness differentially (e.g., Chien et al., 2020; Mizera et al., 2016; Querstret et al., 2017). However, more research is needed to clarify which facets are most relevant to formal versus informal mindfulness practice, as well as to determine whether effects are sustained over longer periods of time.

Interestingly, although assessed using a VAS scale, state well‐being also increased for all participants from pre‐post‐intervention, regardless of their NSSI history or assigned experimental condition (with a large effect size). This was also counter to our hypotheses (H1, H3), as IM and FM were expected to outperform the control task in terms of their effectiveness at increasing state well‐being among both groups of students. It is possible that the active control task had an unintended pleasant effect on participants' sense of well‐being in the moment, despite it being intended to serve as a neutral task. In particular, given the nature of the active control task—which involved following along with an audio recording guiding them to place 100 letters, numbers and symbols in a grid in a specific order over the course of 10 min—it may have led participants to feel ‘calm’, ‘focused’, not ‘distracted’ and so forth (aligned with the phrasing of the VAS items for state well‐being) without impacting their state mindfulness or state stress per se. This might explain why participants reported a greater state of well‐being following all experimental tasks including the active control task, whereas only the FM and IM inductions appeared to induce states of increased mindfulness and decreased stress (when similarly assessed using VAS items). Moreover, the pattern of findings for state well‐being once again did not differ as a function of NSSI history. Rather, a state of increased well‐being was elicited in response to FM, IM, and an active control task regardless of whether or not university students had a recent history of NSSI. This finding therefore does not support any advantage of IM over FM in terms of eliciting a state of well‐being among university students nor does it support an advantage of either IM or FM over an active control task to this same end. Where the goal is to elicit a state of well‐being, it may be the case that a guided, focused task performed over the course of 10 min is no less effective than a brief mindfulness activity at eliciting a state of well‐being.

Acceptability of formal and informal mindfulness inductions

Lastly, across two measures of acceptability, higher levels of acceptability were consistently reported in response to IM relative to the active control task, whereas higher levels of acceptability in response to FM relative to the active control task were only reported when assessed using the TFA Questionnaire; all effect sizes were moderate. A possible interpretation of this discrepancy may be that while both the IMI and TFA Questionnaire inquired about participants' overall liking of their assigned experimental task (e.g., Did you like or dislike the self‐regulation activity? [TFA], I enjoyed doing this activity very much [IMI]), their perception of the task's utility (e.g., It is clear to me how this self‐regulation can improve my well‐being [TFA], I think doing this activity could help me [IMI]) and their sense of competence when completing it (e.g., How confident did you feel about your ability to engage in this self‐regulation activity? [TFA], I think I am pretty good at this activity [IMI]), only the IMI included items around participants' perceived sense of autonomy or choice when completing their assigned task. The common perception of FM inductions as inflexible due to their seemingly rigid verbal directives may have thus undermined participants' perceived sense of autonomy while practicing FM (Petrovic et al., 2023b), while the relatively greater flexibility that is inherent to IM may have led to its rating as significantly more acceptable across both measures used in the present study.

Overall, these findings are aligned with emerging evidence for the particular acceptability of IM inductions over FM inductions reported by university students with a recent history of NSSI (Petrovic et al., 2023b). While research with general adult and adolescent populations have revealed a similar preference for brief IM practices over FM ones (Mettler et al., 2024; Verger et al., 2021), the present study extends these findings to university students without a history of NSSI as well. Moreover, these acceptability findings also demonstrate that despite the significant improvements noted from pre‐post‐intervention across all effectiveness outcomes (i.e., state mindfulness, state stress, state well‐being) and measurement tools, the mindfulness inductions were nevertheless preferred over the active control task by university students with and without a history of NSSI, suggesting potential short‐term advantages of mindfulness inductions (and especially of IM) over an active control task among these populations.

Taken together, results of the present study suggest that IM may be comparable or superior to FM, in terms of both its short‐term effectiveness and acceptability, among university students with and without a history of NSSI. Findings contribute to a growing body of literature, which has documented the distinct benefits of IM among various populations (e.g., Hindman et al., 2015; Mettler et al., 2024; Shankland et al., 2020). Results also challenge the notion that IM is more beneficial for university students with a history of NSSI relative to those without such a history; rather, IM appears to be similarly beneficial for and preferred by all students. Thus, NSSI history—as operationalized in the present study—may not drive heterogeneity in short‐term responses to single‐session mindfulness practices among university student populations. Nevertheless, additional research on the long‐term effectiveness and acceptability of regular IM practice among university students is warranted. Lasting benefits of IM over time may be particularly relevant for students with a history of NSSI, given their relatively low levels of mindfulness and the documented protective effects of mindfulness among this population (Per et al., 2022). Furthermore, IM is easy to implement into one's daily routine and is a highly accessible and resource‐efficient method for cultivating mindfulness skills among university students (Birtwell et al., 2019; Crane et al., 2017; Petrovic et al., 2023b; Ribeiro, 2020).

Limitations and future directions

The present findings should be interpreted within the context of this study's limitations. First, the present university sample is not representative of the general population of young adults with lived experience of NSSI in the last year, in part because it is disproportionately composed of women. Future research should compare the effectiveness and acceptability of FM and IM inductions with a more representative, nonuniversity sample of young adults with a recent history of NSSI engagement. Second, the active control task may have had unintended positive effects on our target outcomes (e.g., on state well‐being). Thus, a replication of these findings with another neutral control task may be informative. Lastly, findings demonstrate the responses to a brief, single‐session practice of FM or IM. Given that the benefits of mindfulness activities are incurred through repeated practice over time (Kabat‐Zinn, 2013; Kiken et al., 2015), the effectiveness and acceptability of these practices in the long‐term should be assessed for these results to be optimally informative for clinical/practical use.

Conclusion

The present randomized controlled trial was the first to explore the effectiveness and acceptability of IM and FM inductions relative to an active control task among university students with and without a past‐year history of NSSI. Counter to our hypotheses, patterns of all findings were the same for those with and without a history of NSSI and suggest that a brief, single‐session IM induction may be more effective in the short‐term and generally preferred relative to a FM induction and an active control task among all university students. Overall, the present study builds upon a growing body of literature that has highlighted the promise of IM and underscores the need for additional research on the longer term effectiveness and acceptability of repeated IM practice among university students.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The present randomized controlled trial was approved by McGill University's Research Ethics Board (22‐06‐104).

Supporting information

File S1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) Results.

File S2. Intervention Audio File Transcripts.

File S3. Results of Three‐Way ANOVAs Across All Facets of Mindfulness as Measured by the VAS.

Petrovic, J. , Mettler, J. , Böke, B. N. , Rogers, M. A. , Hamza, C. A. , Bloom, E. , Di Genova, L. , Romano, V. , & Heath, N. L. (2025). The effectiveness and acceptability of formal versus informal mindfulness among university students with and without recent self‐injury: A randomized controlled trial. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 17(1), e12613. 10.1111/aphw.12613

Funding information Funding for this research was provided through an Insight Grant awarded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC 435‐2022‐0426).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The dataset generated by the research and analyzed within the present study is available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository: https://osf.io/mpdgh.

REFERENCES

- Abend, R. , Dan, O. , Maoz, K. , Raz, S. , & Bar‐Haim, Y. (2014). Reliability, validity and sensitivity of a computerized visual analog scale measuring state anxiety. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45(4), 447–453. 10.1016/j.jbtep.2014.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [DOI]

- Baer, R. A. , Smith, G. T. , Hopkins, J. , Krietemeyer, J. , & Toney, L. (2006). Using self‐report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. 10.1177/1073191105283504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtwell, K. , Williams, K. , van Marwijk, H. , Armitage, C. J. , & Sheffield, D. (2019). An exploration of formal and informal mindfulness practice and associations with wellbeing. Mindfulness, 10(1), 89–99. 10.1007/s12671-018-0951-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broglia, E. , Millings, A. , & Barkham, M. (2021). Student mental health profiles and barriers to help seeking: When and why students seek help for a mental health concern. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(4), 816–826. 10.1002/capr.12462 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chien, W. T. , Chow, K. M. , Chong, Y. Y. , Bressington, D. , Choi, K. C. , & Chan, C. W. H. (2020). The role of five facets of mindfulness in a mindfulness‐based psychoeducation intervention for people with recent‐onset psychosis on mental and psychosocial health outcomes. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 177. 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipriano, A. , Cella, S. , & Cotrufo, P. (2017). Nonsuicidal self‐injury: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1946. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane, R. S. , Brewer, J. , Feldman, C. , Kabat‐Zinn, J. , Santorelli, S. , Williams, J. M. , & Kuyken, W. (2017). What defines mindfulness‐based programs? The warp and the weft. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 990–999. 10.1017/S0033291716003317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, A. F. , Brown, W. W. , Anderson, J. , Datta, B. , Donald, J. N. , Hong, K. , Allan, S. , Mole, T. B. , Jones, P. B. , & Galante, J. (2020). Mindfulness‐based interventions for university students: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. Applied Psychology. Health and Well‐Being, 12(2), 384–410. 10.1111/aphw.12188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well‐being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. 10.1037/0033-2909.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duggan, J. M. , Toste, J. R. , & Heath, N. L. (2013). An examination of the relationship between body image factors and non‐suicidal self‐injury in young adults: The mediating influence of emotion dysregulation. Psychiatry Research, 206(2–3), 256–264. 10.1016/j.psychres.2012.11.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunley, P. , & Papadopoulos, A. (2019). Why is it so hard to get help? Barriers to help‐seeking in postsecondary students struggling with mental health issues: A scoping review. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17(3), 699–715. 10.1007/s11469-018-0029-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing, L. , Hamza, C. A. , & Willoughby, T. (2019). Stressful experiences, emotion dysregulation, and nonsuicidal self‐injury among university students. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48, 1379–1389. 10.1007/s10964-019-01025-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, D. , Boyes, M. , & Hasking, P. (2020). The associations between alexithymia and both non‐suicidal self‐injury and risky drinking: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 140–166. 10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halladay, J. E. , Dawdy, J. L. , McNamara, I. F. , Chen, A. J. , Vitoroulis, I. , McInnes, N. , & Munn, C. (2019). Mindfulness for the mental health and well‐being of post‐secondary students: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Mindfulness, 10, 397–414. 10.1007/s12671-018-0979-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamza, C. A. , Goldstein, A. L. , Heath, N. L. , & Ewing, L. (2021). Stressful experiences in university predict non‐suicidal self‐injury through emotional reactivity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 610670. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.610670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, A. W. , Warner, A. R. , Dehili, V. M. , Canto, A. I. , & Garland, E. L. (2015). Washing dishes to wash the dishes: Brief instruction in an informal mindfulness practice. Mindfulness, 6(5), 1095–1103. 10.1007/s12671-014-0360-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hessler‐Kaufmann, J. B. , Heese, J. , Berking, M. , Voderholzer, U. , & Diedrich, A. (2020). Emotion regulation strategies in bulimia nervosa: An experimental investigation of mindfulness, self‐compassion, and cognitive restructuring. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 7, 13. 10.1186/s40479-020-00129-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindman, R. K. , Glass, C. R. , Arnkoff, D. B. , & Maron, D. D. (2015). A comparison of formal and informal mindfulness programs for stress reduction in university students. Mindfulness, 6, 873–884. 10.1007/s12671-014-0331-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Society for the Study of Self‐Injury . (2023). What is self‐injury? https://www.itriples.org/what-is-nssi

- Kabat‐Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kabat‐Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living (revised edition): Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Bantam Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kiken, L. G. , Garland, E. L. , Bluth, K. , Palsson, O. S. , & Gaylord, S. A. (2015). From a state to a trait: Trajectories of state mindfulness in meditation during intervention predict changes in trait mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences, 81, 41–46. 10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemyre, L. , & Tessier, R. (2003). Measuring psychological stress: Concept, model, and measurement instrument in primary care research. Canadian Family Physician, 49, 1159–1160. https://www.cfp.ca/content/cfp/49/9/1159.full.pdf [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, F. , Berjot, S. , & Deschamps, F. (2012). Clinical stress assessment using a visual analogue scale. Occupational Medicine, 62(8), 600–605. 10.1093/occmed/kqs140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medvedev, O. N. , Titkova, E. A. , Siegert, R. J. , Hwang, Y.‐S. , & Krägeloh, C. U. (2018). Evaluating short versions of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire using Rasch analysis. Mindfulness, 9, 1411–1422. 10.1007/s12671-017-0881-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mettler, J. , Zito, S. , Bastien, L. , Bloom, E. , & Heath, N. L. (2024). How we teach mindfulness matters: Adolescent development and the importance of informal mindfulness. [Manuscript submitted for publication]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Meyers, L. S. , Gamst, G. , & Guarino, A. J. (2017). Applied multivariate research: Design and interpretation. SAGE. 10.4135/9781071802687 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizera, C. M. , Bolin, R. M. , Nugent, W. R. , & Strand, E. B. (2016). Facets of mindfulness related to a change in anxiety following a mindfulness‐based intervention. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26(1), 100–109. 10.1080/10911359.2015.1062674 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2012). Body regard in non‐suicidal self‐injury: Theoretical explanations and treatment decisions. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 26(4), 331–347. 10.1891/0889-8391.26.4.331 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Per, M. , Schmelefske, E. , Brophy, K. , Austin, S. B. , & Khoury, B. (2022). Mindfulness, self‐compassion, self‐injury, and suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A correlational meta‐analysis. Mindfulness, 13(4), 821–842. 10.1007/s12671-021-01815-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, J. , Bastien, L. , Mettler, J. , & Heath, N. L. (2022). The effectiveness of a mindfulness induction as a buffer against stress among university students with and without a history of self‐injury. Psychological Reports, 126(5), 2280–2302. 10.1177/00332941221089282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, J. , Mettler, J. , Böke, B. N. , Rogers,,M. A. , Hamza, C. A. , Bloom, E. , Di Genova, L. , Romano, V. , Arcuri, G. G. , & Heath, N. L. (2023a). The effectiveness and acceptability of formal versus informal mindfulness among university students with and without recent nonsuicidal self‐injury: Protocol for an online, parallel‐group, randomized controlled trial. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 126, 107109. 10.1016/j.cct.2023.107109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic, J. , Milad, J. , Mettler, J. , Hamza, C. , & Heath, N. L. (2023b). Surprise and delight: Response to informal versus formal mindfulness among university students with self‐injury. Psychological Services, 21, 674–684. 10.1037/ser0000825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querstret, D. , Cropley, M. , & Fife‐Schaw, C. (2017). Internet‐based instructor‐led mindfulness for work‐related rumination, fatigue, and sleep: Assessing facets of mindfulness as mechanisms of change. A randomized waitlist control trial. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(2), 153–169. 10.1037/ocp0000028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, L. (2020). Adherence and evidence of effectiveness of informal mindfulness practices: A systematic review [Doctoral dissertation, Pacific University].

- Ryan, R. M. (1982). Control and information in the intrapersonal sphere: An extension of cognitive evaluation theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 450–461. 10.1037/0022-3514.43.3.450 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon, M. , Cartwright, M. , & Francis, J. J. (2017). Acceptability of healthcare interventions: An overview of reviews and development of a theoretical framework. BMC Health Services Research, 17, 88. 10.1186/s12913-017-2031-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon, M. , Cartwright, M. , & Francis, J. J. (2022). Development of a theory‐informed questionnaire to assess the acceptability of healthcare interventions. BMC Health Services Research, 22, 279. 10.1186/s12913-022-07577-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankland, R. , Tessier, D. , Strub, L. , Gauchet, A. , & Baeyens, C. (2020). Improving mental health and well‐being through informal mindfulness practices: An intervention study. Applied Psychology. Health and Well‐Being, 13(1), 63–83. 10.1111/aphw.12216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verger, N. , Shankland, R. , Strub, L. , Kotsou, I. , Leys, C. , & Steiler, D. (2021). Mindfulness‐based programs, perceived stress and well‐being at work: The preferential use of informal practices. European Review of Applied Psychology, 71(6), 100709. 10.1016/j.erap.2021.100709 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaeghen, P. (2021). Mindfulness as attention training: Meta‐analyses on the links between attention performance and mindfulness interventions, long‐term meditation practice, and trait mindfulness. Mindfulness, 12(3), 564–581. 10.1007/s12671-020-01532-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Visted, E. , Vøllestad, J. , Nielsen, M. B. , & Nielsen, G. H. (2015). The impact of group‐based mindfulness training on self‐reported mindfulness: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Mindfulness, 6(3), 501–522. 10.1007/s12671-014-0283-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, D. , Clark, L. A. , & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070. 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West, S. G. , Taylor, A. B. , & Wu, W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. In Hoyle R. H. (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 209–231). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, J. C. , Thompson, E. , Thomas, S. A. , Nesi, J. , Bettis, A. H. , Ransford, B. , Scopelliti, K. , Frazier, E. A. , & Liu, R. T. (2019). Emotion dysregulation and non‐suicidal self‐injury: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. European Psychiatry, 59, 25–36. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2019.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelkowitz, R. L. , & Cole, D. A. (2019). Self‐criticism as a transdiagnostic process in nonsuicidal self‐injury and disordered eating: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Suicide & Life‐Threatening Behavior, 49(1), 310–327. 10.1111/sltb.12436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

File S1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) Results.

File S2. Intervention Audio File Transcripts.

File S3. Results of Three‐Way ANOVAs Across All Facets of Mindfulness as Measured by the VAS.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset generated by the research and analyzed within the present study is available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository: https://osf.io/mpdgh.