Abstract

Buprenorphine is an effective medication for both opioid use disorder (OUD) and chronic pain (CP), but transitioning from full opioid agonists to buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, can be challenging. Preliminary studies suggest that low-dose buprenorphine initiation can overcome some challenges in starting treatment, but no randomized controlled trials have compared low-dose and standard buprenorphine initiation approaches regarding effectiveness and safety or examined implementation in hospital settings.

In a pragmatic open-label hybrid type I effectiveness-implementation trial based in a single urban health system, 270 hospitalized patients with (a) CP and (b) OUD or opioid misuse are being randomized to buprenorphine treatment initiation using 5-day low-dose or standard initiation protocols. Outcomes include buprenorphine treatment uptake (primary), defined as receiving buprenorphine treatment 7 days after enrollment, and other OUD and pain outcomes at 1, 3, and 6-months follow-up (secondary). Data collection will also include safety measures, implementation of low-dose initiation protocols, patient acceptability, and cost-effectiveness.

Comparing strategies in a randomized clinical trial will provide the most definitive data to date regarding the effectiveness and safety of low-dose buprenorphine initiation. The study will also provide important data on treating CP at a time that clinical guidelines are evolving to center buprenorphine as a preferred opioid for CP.

Background:

Description of IMPOWR-ME Research Center

Improving opioid use disorder (OUD) and chronic pain (CP) management requires new integrated approaches that address both interrelated conditions. This article describes one of three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) supported by the Initiative Integrative Management of Chronic Pain and OUD for Whole Recovery (IMPOWR) 1 Research Center at Montefiore Einstein (IMPOWR-ME) in the Bronx, NY. Prioritizing real-world relevance, IMPOWR-ME has partnered with individuals with lived experience with CP and OUD, and with payors, policy and advocacy organizations, and health system leaders to conduct these RCTs, support pilot studies, and disseminate research findings.

Focus of this project

This study, a “Randomized Controlled Trial Of Buprenorphine Low-Dose Induction During Hospitalization For Chronic Pain Conditions,” is testing low-dose buprenorphine initiation for effectiveness and safety among hospitalized patients with CP and OUD or opioid misuse. Buprenorphine, a partial opioid agonist, is an effective but underutilized medication for both CP and OUD.2-4 The standard approach to initiating buprenorphine treatment requires patients to stop other opioids and experience opioid withdrawal before starting buprenorphine, which may limit treatment uptake.5,6 An innovative low-dose strategy for buprenorphine initiation may overcome this challenge but requires additional testing.

Rationale and Overall Goal

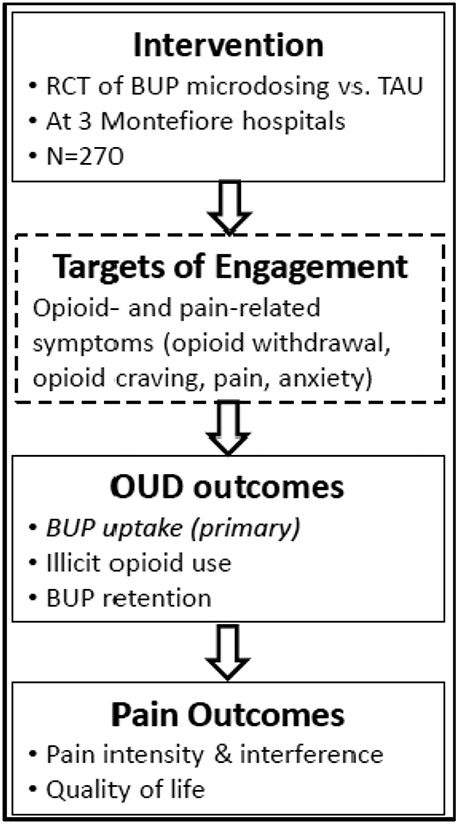

Buprenorphine is a US Food and Drug Administration-approved medication for both chronic pain and OUD. Buprenorphine treatment reduces non-prescribed opioid use, opioid cravings, and all-cause and overdose mortality making it a first-line OUD treatment.7,8 As a pain medication, buprenorphine has similar analgesic efficacy 9-11 and may induce less opioid-induced hyperalgesia during long-term use than other opioid analgesics.12 Additionally, buprenorphine blocks the effects of misused opioids improving safety for persons with CP and OUD.13,14 Nonetheless, buprenorphine, is an underutilized medication for both CP and OUD.2-4,15 One major challenge limiting buprenorphine use is that buprenorphine’s pharmacology makes it difficult to initiate treatment.6,16 Due to buprenorphine’s partial opioid agonism, taking typical dosages soon after taking full opioid agonists can precipitate opioid withdrawal symptoms.17,18 In the standard initiation approach, patients with physical opioid dependence are instructed to stop other opioids and start buprenorphine after they experience moderate opioid withdrawal; however, those who cannot tolerate withdrawal may never start buprenorphine.6,19,20 If buprenorphine worsens opioid withdrawal during initiation, patients may prematurely drop-out of treatment.21-23 Regular fentanyl use may increase the risk of precipitated withdrawal and initiation failure, amplifying the barriers to treatment for many patients.24 Therefore, improving buprenorphine initiation protocols could increase treatment uptake and improve retention in treatment.25 See Figure 1 for overview of study and target of engagement.

Figure 1.

Study Summary

Bup = buprenorphine ∣ TAU = treatment as usual

Numerous case reports and other observational studies suggest that starting buprenorphine at low doses can facilitate buprenorphine initiation, but current data are not strong enough to establish definitive clinical guidelines.16 Low-dose buprenorphine initiation starts with doses ≤ 0.5 mg, which typically will not precipitate withdrawal, and doses can be gradually increased while continuing a full opioid agonist.26 This approach is theorized to minimize the withdrawal and pain common with standard buprenorphine initiation.25 Observational data suggest that patients experience minimal opioid withdrawal during low-dose buprenorphine initiation and most patients successful transition to maintenance doses of buprenorphine.23-26 27,28 Despite these promising results, the current literature on low-dose initiation are limited to case reports and retrospective cohort studies, which are not designed to draw strong conclusions regarding the risks and benefits of the low-dose initiation approach.26 In recent cohort studies of low-dose buprenorphine initiation 16-32% of hospitalized patients failed to fully transition to buprenorphine, demonstrating that initiation success is not universal among all patients.29-31 While standard buprenorphine initiation protocols can be completed in 1 or 2 days, low-dose buprenorphine initiation protocols last anywhere from 3 to more than 20 days. A prolonged initiation process could leave patients with opioid withdrawal symptoms, require more supplemental full agonist opioids, and lead to early treatment drop-out.29,31 Therefore, low-dose buprenorphine initiation may benefit some patients but has not supplanted standard protocols as the default approach to starting buprenorphine treatment. Clinical trials that compare low-dose and standard buprenorphine initiation protocols, and implementation data that examines patient and provider acceptability and experiences, are needed to inform clinical guidelines and aid in best practices being disseminated in real-world settings.

This study focuses on the hospital setting, because general hospitals are highly utilized by people with OUD and CP and can be a critical touch-point to prevent opioid overdoses.32-34 Initiating buprenorphine treatment during hospitalization improves linkage to outpatient OUD treatment.35,36 Transitioning from full opioid agonists to buprenorphine could also lower the risk of opioid-related adverse events after hospital discharge for patients without OUD. However, retrospective cohort studies suggest that one-third of hospitalized patients starting a low-dose buprenorphine initiation do not complete the process, which highlights the challenges with implementation.29-31

The overall goal of the study is to definitively test low-dose buprenorphine initiation among hospitalized patients with CP and OUD, while also providing essential implementation data. The study aims to test the effectiveness of low-dose initiation on: 1) OUD outcomes and 2) pain outcomes, and 3a) examine factors influencing reach, adoption, implementation and maintenance of low-dose initiation in hospital settings, and 3b) calculate the cost and examine the cost-effectiveness of low dose initiation in hospital settings.

Methods

Study design:

This hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation study uses a pragmatic open-label RCT design. The full study protocol is available in Appendix 1. Hospitalized patients with CP and OUD or opioid misuse who start buprenorphine are randomized to low-dose or standard initiation protocols. Participants receive office-based buprenorphine treatment after discharge. End-points include buprenorphine treatment uptake (primary outcome) and other OUD and pain outcomes (secondary outcomes) at 1, 3, and 6 months. The trial is registered with clinical trials.gov (NCT05118204) and was approved by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine’s Institutional Review Board. The IMPOWR-ME Center’s Data and Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) and Community Leadership Board provided input regarding the study.

Setting:

Three hospitals in the Montefiore Health System, the largest healthcare provider in the Bronx, serve as study sites. During hospitalization, generalist physicians care for medical patients with support from pain, addiction medicine, and psychiatry consultation. Montefiore has many outpatient buprenorphine treatment providers, including 20 community health centers and 5 Opioid Treatment Programs.

Study participants:

Participants are hospitalized patients (N = 270) with CP and OUD or opioid misuse. Chronic pain is defined as pain occurring on most or all days for ≥ 3 months with at least moderate intensity and interference (score >4 on Pain, Enjoyment of Life and General Activity scale).37 Opioid misuse is defined as prescribed or non-prescribed opioid use without a prescription; use in greater amounts or more often than prescribed; or running out of prescribed opioids early.38 OUD is based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria (mild, moderate, or severe).39

Recruitment:

An algorithm is used to search Montefiore electronic medical records for potentially eligible hospitalized patients. Using documented diagnoses in problem lists (e.g., opioid dependence), prescribed medications (e.g., oxycodone), and key words (e.g., overdose), a potential participant list is generated daily. Study clinicians manually review medical records and request permission from patient’s attending physician to pursue screening.

Data collection:

A study coordinator conducts research visits with participants at baseline, 1 week, and 1, 3 and 6 months collecting urine for drug testing and questionnaire data. Participants also receive mobile devices and complete Electronic Momentary Assessment prompts 5 times daily to track opioid- and pain-related symptoms during buprenorphine initiation (14 days) and during three 1-week periods in follow-up.

Study treatments:

Participants are randomized (1:1 ratio) to a low-dose or standard buprenorphine initiation protocol. Buprenorphine doses less than 2 mg are administered as buprenorphine buccal films and doses ≥ 2 mg are administered as buprenorphine-naloxone (bup-nx) sublingual films. The buccal films were chosen to avoid splitting the sublingual films or tablets.

Low-dose protocol

Participants start “low-dose” buprenorphine while continuing a full opioid agonist according to a 5-day protocol (see Table 1). Starting doses and speed of dose titration were informed by published reports.26,40 Low-dose protocols have ranged from 3 to 7 days or more, and a 5-day protocol was chosen based on Montefiore’s average hospital length of stay to help participants reach stable buprenorphine doses prior to discharge. Clinicians may prescribe other opioids, including methadone, to manage pain or withdrawal during initiation. Final buprenorphine doses are agreed upon by participants and study clinicians with a maximum dose of 16-4 mg bup-nx daily.

Table 1.

Buprenorphine Initiation Dosing Schedule

| Day | Low-dose initiation | Treatment As Usual (TAU) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bup or Bup-nx | Full agonist | Bup-nx | Full agonist |

|||

| Total daily bup dose |

Dosing | Total daily bup dose |

||||

| 1 | 225 mcg* q12 | 1 mg | Full dose | -- | -- | STOP |

| 2 | 450 mcg* q8 | 3 mg | Full dose | 2-0.5 mg q6 | 8 mg | -- |

| 3 | 2-0.5 mg q8 | 6 mg | Full dose | 8-2 mg q12 | 16 mg | -- |

| 4 | 4-1 mg q8 | 12 mg | Full dose | 8-2 mg q12 | 16 mg | -- |

| 5 | 8-2 mg q12 | 16 mg | STOP | 8-2 mg q12 | 16 mg | -- |

Buprenorphine Buccal Film: 225 mcg is equivalent to 0.5 mg bup in bup-nx for calculations

Bup = buprenorphine ∣ Bup-nx = buprenorphine-naloxone

q6, 8 or 12 = every 6, 8 or 12 hours respectively

Standard protocol

Participants receive a standard guideline-informed protocol for buprenorphine initiation (see Table 1).41 All opioids are stopped and a clinician assesses for withdrawal using the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS).42 Participants with COWS scores of ≥8 are eligible to receive a 2-0.5 mg dose of bup-nx with additional dose titration over two days. Final buprenorphine doses are agreed upon by participants and study clinicians with a maximum dose of 16-4 mg bup-nx.

Follow-up treatment

After hospital discharge, participants receive buprenorphine treatment and pain management at Montefiore community health centers. Buprenorphine doses may be increased to 24-6 mg bup-nx daily, and primary care physicians may prescribe adjuvant medications for CP or opioid withdrawal as needed.

Effectives Outcomes

Primary outcome:

Buprenorphine treatment uptake, defined as receiving buprenorphine 7 days after enrollment using electronic health record data (hospital medication administration or prescriptions).

Secondary outcomes:

Key secondary treatment outcomes include non-prescribed opioid use, retention in buprenorphine treatment, pain intensity and pain interference, and opioid withdrawal symptoms. Non-prescribed opioid use will be measured by urine toxicology and self-reported use of heroin, fentanyl, or non-prescribed opioid analgesics in the prior 30 days based on an adapted version of the Addiction Severity Index (ASI).43 Retention in buprenorphine treatment is defined as having a buprenorphine prescription dispensed at the pharmacy 180-210 days (6-month retention) after enrollment, as recorded in the state prescription drug monitoring program.44 Pain intensity and pain interference scores is measured using the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI).45

Implementation Outcomes

Implementation evaluation follows the RE-AIM framework (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, and maintenance). Process measures include: the number and percentage of patients with CP and OUD who are screened and enrolled (reach), assessed for BUP, complete initiation, and linked to outpatient treatment (adoption), receive ≥1 dose of buprenorphine within the assigned initiation protocol, and meet fidelity standards (implementation), as well as the number of hospitals still conducting low-dose initiation three months after the grant ends (maintenance). See Appendix 1 for more details.

Feasibility and acceptability are evaluated through qualitative interviews with participants and providers. For the participant interviews, a semi-structured interview guide, informed by people with lived experience, includes open-ended questions about patients’ experiences with initiation, reasons for buprenorphine initiation or lack of initiation, and whether buprenorphine helps with pain. For provider interviews, the semi-structured interview guide, informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), focuses on the innovation (i.e., low-dose buprenorphine initiation) and the hospital setting where implementation has occurred. Interviews probe how various factors enable or hinder implementing the low-dose protocol, including ease of initiating buprenorphine (e.g., feasibility), organizational characteristics (e.g., fit and acceptability within hospitals), the outer setting (e.g., social factors influencing clinical practice), perceptions of individuals involved (e.g., perceived benefits of buprenorphine for pain), and implementation processes (e.g., protocol adaptation). Questions regarding potential barriers to implementation, such as provider stigma about OUD, and facilitators, such as leadership endorsement of protocols, are also included in interview guides.

Cost-effectiveness Analysis

We will also collect data on implementation costs and quality of life hypothesizing that low-dose buprenorphine initiation will be cost-effective from health care sector and societal perspectives. Health Related Quality of Life is measured with the PROMIS-Preference (PROPr) scoring system and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) is the effectiveness measure.46,47

Safety

Because buprenorphine and bup-nx are FDA-approved medications, there will not be a formal safety endpoint. The frequency, severity, and relationship of adverse events (AEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs) are tallied as the total numbers in each study arm. These AEs and SEAs will be compared between study arms in aggregate.

Discussion

To our knowledge, we are conducting the first RCT of low-dose buprenorphine initiation in the US. Buprenorphine is an effective treatment for both CP and OUD, yet the experiences of withdrawal while transitioning from full agonist opioids to buprenorphine acts as a barrier to treatment uptake and retention. Low-dose buprenorphine protocols, which may lessen withdrawal symptoms, are increasingly used in clinical practice, yet remain untested by prospective clinical trials. There also remain open questions about effective implementation. This study will provide important insights regarding effectiveness, safety, patient experience and acceptability, cost-effectiveness, and implementation of low-dose protocols in hospitals. Study findings will inform future clinical guidelines.

The chosen hybrid type 1 effectiveness-implementation study design balances rigor and generalizability using real-world clinical settings. The study is pragmatic with broad inclusion criteria (e.g., heterogenous chronic pain conditions) and uses buprenorphine products widely available in the US, which replicates the conditions that clinicians face when managing hospitalized patients with CP and OUD or opioid misuse. Linkage to outpatient buprenorphine providers also reflects real-world conditions, and follow-up over 6 months allows for assessment of longer-term CP outcomes. The implementation outcomes include participant acceptability, which will help create more patient-centered approaches to buprenorphine treatment initiation.

Feedback from the IMPOWR-ME Community Leadership Board (CLB) was also incorporated into the study design and conduct. Because buprenorphine is frequently prescribed for OUD, patients with CP may worry about being labeled as having an OUD, which carries stigma and could affect future pain management decisions; therefore, we developed written patient-facing materials that outline buprenorphine’s risks and benefits and addresses potential stigma. We also trained hospital-based physicians on buprenorphine prescribing and stigma reduction. The CLB perceived that people with CP are generally unaware of buprenorphine as an effective pain treatment; therefore, we will tailor dissemination efforts to both scientific and general communities, if the study shows beneficial pain outcomes.

The study plays an important role in extending currently available observational data. Another RCT of low-dose buprenorphine initiation for OUD is underway in Canada, but that study does not focus on CP, has a smaller sample size, and will not report follow-up outcomes at 6 months.48 This study will also provide data at an important moment in the evolving practices of chronic pain treatment. According to the latest Department of Defense and the Veterans Administration guidelines, buprenorphine is now recommended as the first-line opioid when opioids are used for chronic pain.49 Data on transitioning from full agonist opioids to buprenorphine, and follow-up pain outcomes for patients taking buprenorphine, will be valuable for extending these guidelines in areas where currently available data are insufficient.

Our study also has limitations. There could be selection bias in that potential participants who had previously experienced precipitated withdrawal while initiating buprenorphine may be less likely to participate than others. With an open-label design, participant preference for one protocol could affect compliance when participants are randomized to their less preferred protocol. The study is conducted in a low-income urban community with broad buprenorphine treatment access, but implementation outcomes (i.e., feasibility and acceptability) may be different in other geographic areas.

Conclusion

Buprenorphine is an important treatment for people with CP and OUD. However, challenges with starting treatment limit uptake. Low-dose buprenorphine initiation may overcome these barriers. Our study will provide important data on the effectiveness, implementation and safety of this novel approach.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

This will be the first randomized controlled trial of low-dose buprenorphine for people with chronic pain and opioid use disorder or opioid misuse.

The primary outcome will be buprenorphine treatment uptake at 7 days following enrollment.

The study will also examine longer-term impact on opioid use disorder and chronic pain outcomes.

Funding

The research described was supported by National Institutes of Health under Grant RM1DA055437. Dr. Hayes is supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant K23DA055933. Dr. Starrels is supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant K24DA046309. Dr. Fox is additionally supported by National Institutes of Health under Grant Number K24DA057873. Dr. Gabbay is additionally supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grants P30AI124414, R01DA054885, R21MH126501, R01MH120601, R21MH121920, R01MH128878, and R01MH126821

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: none

CRediT roles:

Benjamin T. Hayes: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Funding acquisition; Writing – original draft

Guillermo Sanchez Fat: Investigation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing

Kristine Torres-Lockhart: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing

Laila Khalid: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Writing – Reviewing and Editing

Haruka Minami: Methodology; Writing – Reviewing and Editing

Megan Ghiroli: Project administration; Software

Mary Beth Hribar, MPP: Project administration

Jessica Pacifico, MD: Investigation

Yuhua Bao, Ph.D: Data curation; Methodology; Writing – Review and Editing

Caryn R. R. Rodgers, Ph.D: Methodology; Writing – Review and Editing

Vilma Gabbay, MD: Conceptulization; Funding acquisition; Methodology; Visulization

Joanna Starrels, MD, MS

Aaron D. Fox: Conceptualization; Supervision; Project administration; Investigation; Funding acquisition; Writing – Reviewing and Editing; Visulization

References

- 1.Su ZI. Addressing the Intersections of Chronic Pain and OUD: Integrative Management of Chronic Pain and OUD for Whole Recovery (IMPOWR) Research Network. Subst Use Addctn J. Mar 14 2024:29767342241236592. doi: 10.1177/29767342241236592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Feb 06 2014;(2):CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aiyer R, Gulati A, Gungor S, Bhatia A, Mehta N. Treatment of Chronic Pain With Various Buprenorphine Formulations: A Systematic Review of Clinical Studies. Anesth Analg. Aug 2018;127(2):529–538. doi: 10.1213/ane.0000000000002718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saloner B, Karthikeyan S. Changes in Substance Abuse Treatment Use Among Individuals With Opioid Use Disorders in the United States, 2004-2013. JAMA. Oct 13 2015;314(14):1515–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daitch J, Frey ME, Silver D, Mitnick C, Daitch D, Pergolizzi J Jr. Conversion of chronic pain patients from full-opioid agonists to sublingual buprenorphine. Pain Physician. Jul 2012;15(3 Suppl):Es59–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller JC, Brooks MA, Wurzel KE, Cox EJ, Wurzel JF 3rd. A Guide to Expanding the Use of Buprenorphine Beyond Standard Initiations for Opioid Use Disorder. Drugs R D. Dec 2023;23(4):339–362. doi: 10.1007/s40268-023-00443-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bart G. Maintenance medication for opiate addiction: the foundation of recovery. J Addict Dis. 2012;31(3):207–25. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.694598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. British Medical Association. Apr 26 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudin J, Fudin J. A Narrative Pharmacological Review of Buprenorphine: A Unique Opioid for the Treatment of Chronic Pain. Pain and Therapy. Jun 2020;9(1):41–54. doi: 10.1007/s40122-019-00143-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raffa RB, Haidery M, Huang HM, et al. The clinical analgesic efficacy of buprenorphine. J Clin Pharm Ther. Dec 2014;39(6):577–83. doi: 10.1111/jcpt.12196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen KY, Chen L, Mao J. Buprenorphine-naloxone therapy in pain management. Anesthesiology. May 2014;120(5):1262–74. doi: 10.1097/aln.0000000000000170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, Patel VB, Manchikanti L. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician. Mar-Apr 2011;14(2):145–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McDermott KA, Griffin ML, McHugh RK, et al. Long-term naturalistic follow-up of chronic pain in adults with prescription opioid use disorder. Drug Alcohol Depend. Dec 1 2019;205:107675. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.107675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones JD, Sullivan MA, Manubay J, Vosburg SK, Comer SD. The subjective, reinforcing, and analgesic effects of oxycodone in patients with chronic, non-malignant pain who are maintained on sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone. Neuropsychopharmacology. Jan 2011;36(2):411–22. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones CM, Han B, Baldwin GT, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Use of Medication for Opioid Use Disorder Among Adults With Past-Year Opioid Use Disorder in the US, 2021. JAMA Netw Open. Aug 1 2023;6(8):e2327488. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.27488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weimer MB, Herring AA, Kawasaki SS, Meyer M, Kleykamp BA, Ramsey KS. ASAM Clinical Considerations: Buprenorphine Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder for Individuals Using High-potency Synthetic Opioids. J Addict Med. Nov-Dec 01 2023;17(6):632–639. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000001202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosado J, Walsh SL, Bigelow GE, Strain EC. Sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone precipitated withdrawal in subjects maintained on 100mg of daily methadone. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. Oct 8 2007;90(2-3):261–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh SL, Eissenberg T. The clinical pharmacology of buprenorphine: extrapolating from the laboratory to the clinic. Drug Alcohol Depend. May 21 2003;70(2 Suppl):S13–27. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00056-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Henry SG, Paterniti DA, Feng B, et al. Patients' Experience With Opioid Tapering: A Conceptual Model With Recommendations for Clinicians. J Pain. Feb 2019;20(2):181–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2018.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frank JW, Levy C, Matlock DD, et al. Patients' Perspectives on Tapering of Chronic Opioid Therapy: A Qualitative Study. Pain Med. Oct 2016;17(10):1838–1847. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnw078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenblum A, Cruciani RA, Strain EC, et al. Sublingual buprenorphine/naloxone for chronic pain in at-risk patients: development and pilot test of a clinical protocol. J Opioid Manag. Nov-Dec 2012;8(6):369–82. doi: 10.5055/jom.2012.0137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stein MD, Herman DS, Kettavong M, et al. Antidepressant treatment does not improve buprenorphine retention among opioid-dependent persons. J Subst Abuse Treat. Sep 2010;39(2):157–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2010.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee JD, Grossman E, DiRocco D, Gourevitch MN. Home buprenorphine/naloxone induction in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. Feb 2009;24(2):226–32. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0866-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varshneya NB, Thakrar AP, Hobelmann JG, Dunn KE, Huhn AS. Evidence of Buprenorphine-precipitated Withdrawal in Persons Who Use Fentanyl. J Addict Med. Jul-Aug 01 2022;16(4):e265–e268. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams KK, Machnicz M, Sobieraj DM. Initiating buprenorphine to treat opioid use disorder without prerequisite withdrawal: a systematic review. Addict Sci Clin Pract. Jun 8 2021;16(1):36. doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00244-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen SM, Weimer MB, Levander XA, Peckham AM, Tetrault JM, Morford KL. Low Dose Initiation of Buprenorphine: A Narrative Review and Practical Approach. J Addict Med. Jul-Aug 01 2022;16(4):399–406. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmed S, Bhivandkar S, Lonergan BB, Suzuki J. Microinduction of buprenorphine/naloxone: A review of the literature. Am J Addict. Jul 2021;30(4):305–315. doi: 10.1111/ajad.13135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moe J, O'Sullivan F, Hohl CM, et al. Short communication: Systematic review on effectiveness of micro-induction approaches to buprenorphine initiation. Addict Behav. Mar 2021;114:106740. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhatraju EP, Klein JW, Hall AN, et al. Low Dose Buprenorphine Induction With Full Agonist Overlap in Hospitalized Patients With Opioid Use Disorder: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Addict Med. Jul-Aug 01 2022;16(4):461–465. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Button D, Hartley J, Robbins J, Levander XA, Smith NJ, Englander H. Low-dose Buprenorphine Initiation in Hospitalized Adults With Opioid Use Disorder: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. J Addict Med. Mar-Apr 01 2022;16(2):e105–e111. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hayes BT, Li P, Nienaltow T, Torres-Lockhart K, Khalid L, Fox AD. Low-dose buprenorphine initiation and treatment continuation among hospitalized patients with opioid dependence: A retrospective cohort study. J Subst Use Addict Treat. Dec 14 2023;158:209261. doi: 10.1016/j.josat.2023.209261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peterson C, Xu L, Mikosz CA, Florence C, Mack KA. US hospital discharges documenting patient opioid use disorder without opioid overdose or treatment services, 2011-2015. J Subst Abuse Treat. Sep 2018;92:35–39. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2018.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orhurhu V, Olusunmade M, Urits I, et al. Trends of Opioid Use Disorder Among Hospitalized Patients With Chronic Pain. Pain Pract. Jul 2019;19(6):656–663. doi: 10.1111/papr.12789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larochelle MR, Bernstein R, Bernson D, et al. Touchpoints - Opportunities to predict and prevent opioid overdose: A cohort study. Drug Alcohol Depend. Nov 1 2019;204:107537. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liebschutz JM, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine Treatment for Hospitalized, Opioid-Dependent Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2014;174(8):1369–1376. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Trowbridge P, Weinstein ZM, Kerensky T, et al. Addiction consultation services - Linking hospitalized patients to outpatient addiction treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. Aug 2017;79:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. Jun 2009;24(6):733–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0981-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hughes A, Williams M, Lipari R, Bose J, Copello E, Kroutil L. Prescription drug use and misuse in the United States: results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review. Accessed June 27, 2023. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FFR2-2015/NSDUH-FFR2-2015.htm [Google Scholar]

- 39.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weimer MB, Guerra M, Morrow G, Adams K. Hospital-based Buprenorphine Micro-dose Initiation. J Addict Med. May-Jun 01 2021;15(3):255–257. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cunningham C, Edlund FMJ, Fishman M, et al. The ASAM National Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder: 2020 Focused Update. J Addict Med. Mar/Apr 2020;14(2S Suppl 1):1–91. doi: 10.1097/adm.0000000000000633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wesson DR, Ling W. The Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS). J Psychoactive Drugs. Apr-Jun 2003;35(2):253–9. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fox AD, Sohler NL, Starrels JL, Ning Y, Giovanniello A, Cunningham CO. Pain is not associated with worse office-based buprenorphine treatment outcomes. Subst Abus. 2012;33(4):361–5. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.638734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Poquet N, Lin C. The Brief Pain Inventory (BPI). J Physiother. Jan 2016;62(1):52. doi: 10.1016/j.jphys.2015.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dewitt B, Feeny D, Fischhoff B, et al. Estimation of a Preference-Based Summary Score for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System: The PROMIS(®)-Preference (PROPr) Scoring System. Med Decis Making. Aug 2018;38(6):683–698. doi: 10.1177/0272989x18776637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanders GD, Neumann PJ, Basu A, et al. Recommendations for Conduct, Methodological Practices, and Reporting of Cost-effectiveness Analyses: Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine. JAMA. Sep 13 2016;316(10):1093–103. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mathew N, Azar P. Comparing Rapid Micro-Induction and Standard Induction of Buprenorphine/Naloxone for Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT04234191. Updated October 7, 2022. Accessed April 29, 2024. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04234191?cond=opioid%20use%20disorder&intr=microdosing%20buprenorphine&rank=5#collaborators-and-investigators [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sandbrink F, Murphy JL, Johansson M, et al. The Use of Opioids in the Management of Chronic Pain: Synopsis of the 2022 Updated U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. Mar 2023;176(3):388–397. doi: 10.7326/m22-2917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.