ABSTRACT

Background and Aims

Organ donation is the last option for patients with end‐stage organ failure, but the number of people in need of transplantation outweighs the supply of donor organs. A thorough analysis of public understanding is required to design educational programs that increase public commitment to organ donation. Therefore, the present study aimed to explore Bangladeshi adults' understanding, attitudes, and willingness towards organ donation, while also investigating the sources of information, gender‐specific knowledge, intentions, and the factors influencing their decisions.

Methods

A cross‐sectional survey was conducted between October 15 and November 25, 2021, using a non‐probability convenience sampling technique. Data were analysed using both descriptive and inferential statistics.

Results

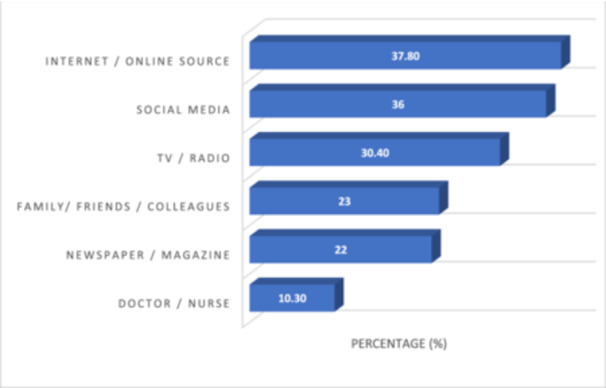

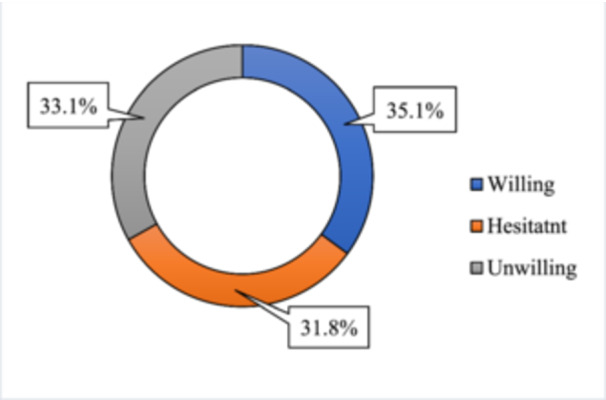

Among 592 participants, only 35.8% were knowledgeable about organ donation. Internet/online sources were the most reported source of knowledge (37.8%), followed by social media (36%). Despite having limited knowledge, 63.7% had a positive attitude, with females demonstrating a more positive attitude than males (β = 0.09, p = 0.024). Males were significantly more likely than females to follow Bangladesh's specific organ donation laws (29.3% vs. 25%, p = 0.004). Besides, 48.6% of females, compared to 40.4% of males, believe that the health service related to organ donation in Bangladesh is ineffective (p = 0.016). More than one‐third (35.1%) of the participants indicated a willingness to donate their organs after death. The participants' significant barriers to organ donation were found to be family objections (40.4%), health complications (34.4%), fear of disfigurement (31.1%), and religious barriers (26.8%).

Conclusion

Although Bangladeshi adults have a positive attitude regarding organ donation, they lack adequate knowledge, which renders them unlikely to be eager to donate organs. Therefore, it is crucial to update policy within a sociocultural framework to boost organ donation for transplantation. National education campaigns and awareness‐raising events should be held in Bangladesh to increase public knowledge of organ donation and transplants.

Keywords: attitude, Bangladesh, knowledge, organ donation, willingness

1. Introduction

Organ donation is the lifesaving process of surgically removing an organ or tissue from a healthy donor and placing it in a patient in need because of organ failure [1]. At the last stage of organ failure, it is the only possible treatment for the patient [2]. Though organ donation is one of the most scientifically advanced treatment procedures in modern medicine, the number of donors is minimal compared to its immense necessity [3]. According to the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, about 157494 solid organ transplants were performed globally in 2022, meeting less than 10% of the world's needs. On average, 18 transplants are carried out every hour [4]. Tragically, 17 people die each day while waiting for an organ transplant, and every 8 min, a new patient is added to the transplant waiting list [5].

Concerning organ donation, there will always be moral and legal issues. To help increase the rate of organ donation, it is crucial to dispel community misconceptions about the donation process [6]. Numerous factors can impact a person's decision to donate their organs, as evidenced by literature. Mistrust of the organ allocation system, legal upholding of organ donation inconsistently, institutional mistrust, and racial, ethnic, and religious viewpoints on organ donation are some of these factors [7]. The development of beliefs around organ donation is significantly influenced by cultural and religious perspectives [8]. The three monotheistic religions of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity all encourage deceased donations as an expression of compassion, love, and respect for fellow humans. It is not specifically forbidden for anyone to donate organs in any of these three faiths. Any transplant from a living or deceased donor is accepted by these three religions. The Christian belief, however, permits and even encourages organ donation for transplantation far more easily than the Jewish and Muslim doctrines [9, 10, 11, 12]. Organ donation and transplantation are also supported by Hinduism [13]. Other common factors that can affect organ donation are misinformation, social values, the taboo around dying, and procrastination [14].

In Bangladesh, there are certain societal obstacles and prejudices against organ donation, making it challenging to donate organs. For instance, most Bangladeshis prefer to be buried with their bodies intact. Hence, they refuse to give organs after death [15]. Moreover, one of the biggest challenges to organ donation in Bangladesh is a lack of instruments to facilitate donation, rather than those who do not want to donate their organs. Because of those factors, people have less belief in the procedure and are discouraged from donating organs, which is affecting organ donation [16]. Organ donation is greatly influenced by public perceptions of and views toward organ donation. In Bangladesh, the lack of public awareness may serve as a reason for the absence of posthumous organ donation from brain‐dead patients [17].

In Bangladesh, Muslims make up almost 90% of the population. Muslims are confused about whether they should give their organs after death due to the disparity in opinions among Islamic experts [17]. As a result, Islamic authorities have issued a religious ruling (fatwa) supporting the acquisition of organs from brain‐dead individuals, which has affected Bangladeshi people's attitudes regarding organ donation for transplantation. On April 13, 1999, the Human Organ Transplantation Act was formally enacted in Bangladesh, permitting the donation of organs for transplantation from both related living donors and brain‐dead donors. Before this 1999 legislation was passed, Muslim religious authorities' consent, or a fatwa, was also acquired. On January 8, 2018, the Parliament revised the statute, primarily by adding a living‐related donor pool to the already‐existing act. Currently, no system exists for donors to register, making it unlikely that any donors will be found for transplants. The only possibilities are to see hospitalized patients whose families have given permission to be considered brain dead or to collect organs from an unclaimed deceased body [18].

Almost 180 million people live in the highly populated nation of Bangladesh. Thousands of people in Bangladesh die every year because of organ failure and the unavailability of organs, donors, prospective transplantation, and transplantation capacity [19]. This is because the number of suffering patients who need organ transplantation is much higher than organ availability or donor availability [20, 21]. Even though there is a growing demand for organ transplantation, the country's organ donation practice is inadequate. According to some studies, a lack of knowledge, ignorance, and social stigma are the leading causes of this [15, 20, 22].

It is recommended that to increase the number of organ donors, education about organ donation is necessary. Before launching educational initiatives to promote organ donation, it is critical to assess public perceptions of and attitudes toward the practice [23, 24]. A person's willingness to donate an organ is determined by their knowledge and views about organ donation. Enhancing the number of organ donors should be a top priority to reduce the morbidity and mortality linked to untreated organ failure [25]. Given the information above, the current research seeks to determine Bangladeshi adults' knowledge, attitudes, and willingness concerning organ donations while also examining the sources of information and gender‐specific knowledge, intention, and factors influencing their decision.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design, Participants, and Sampling

An online‐based cross‐sectional survey was conducted between October 15 and November 25, 2021, through Google Forms due to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Initially, a pre‐tested, structured questionnaire was developed in Google Forms and circulated across various social media platforms (Facebook, Messenger, and WhatsApp). To participate in the survey, the inclusion criteria were adults (18 years old), users of social media, and current residents of Bangladesh. Incomplete responses and people under the age of 18 were all excluded from the study. The following equation was used to calculate the sample size:

Here, n = number of samples, z = 1.96 (95% confidence level), p = prevalence estimate (0.5), q = (1−p), and d = precision limit or proportion of sampling error (0.05). Assuming a 10% nonresponse rate, a total sample size of 423.5 ≈ 424 was estimated. However, the survey questionnaire was completed by 592 eligible participants and taken for final analysis.

2.2. Measures

The survey comprised questions relating to socio‐demographic information, awareness and source of knowledge, knowledge, and attitude toward organ donation. The survey questionnaire was developed after an extensive review of previous studies related to organ donation.

2.2.1. Socio‐Demographic Measures

Participants' socio‐demographic data were collected using closed‐ended questions involving their age, gender, educational level, marital status, family type, monthly family income [that was categorized into four groups: less than 20,000 Bangladeshi Taka (BDT) or < 170 USD, 20,000–30,000 BDT (170–255 USD), 30,000–40,000 BDT (255–340 USD), and more than 40,000 BDT(> 340 USD], and place of residence.

2.2.2. Awareness and Source of Knowledge

Participants' awareness was determined by asking, “Do you hear about organ donation?” with a dichotomous (“yes/no”) response. Participants who responded positively were identified as “aware” of organ donation. Then, participants were asked to mention the common sources from which they heard information regarding organ donation.

2.2.3. Knowledge About Organ Donation

The participants knowledge about organ donation was assessed using 10 questions adapted from previous research [26, 27]. The response options were “true,” “false,” and “don't know.” For scoring the knowledge items, 1 point was awarded for the correct response, and 0 points were awarded for an incorrect/unknown response. The total knowledge score for items ranged from 0 to 10. Participants with scores of less than 60% (0–6 out of 10) were considered to have poor knowledge, while those who scored ≥ 60% (6–10 out of 10) were regarded to have good knowledge [28]. In addition, participants were also asked, “Do you know which organs could be donated?” and “Who is the ideal candidate for organ donation?” with multiple response options.

2.2.4. Attitude Toward Organ Donation

The participants' attitudes were measured using a 5‐point Likert scale with “strongly disagree,” “disagree,” “neutral,” “agree,” and “strongly agree,” each weighing 1 to 5, with a higher score denoting a more positive attitude. Participants were classified as having a low attitude if they scored less than 60% and as having a high attitude if they scored more than ≥ 60% [28].

2.2.5. The Intentions of the Participants Toward Organ Donation

Participants' intention towards organ donation was assessed by asking, “Would you be willing to donate organs if needed?” Response options included “willing,” “hesitant,” and “not willing.” Those who were willing to donate organs were asked, “What will be the driving factors for you when you decide to donate your organs?” as opposed to “What are the reasons for your unwillingness to donate organs?” among the unwilling and hesitant group. Participants were able to choose multiple answers among the possible options.

2.3. Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study followed the ethical principles of the Helsinki Declaration 2013 along with STROBE guidelines 2007 for a cross‐sectional study. The ethical aspects of this study were also reviewed and approved by the Biosafety, Biosecurity, and Ethical Review Board of the Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka‐1342, Bangladesh [Ref No: BBEC, JU/M 2021/09 (3)]. All responses were anonymous, ensuring data confidentiality. All participants provided their informed consent to participate in the study after being informed the purpose of the study.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The data from the responses in Google Forms was coded and prepared for final analysis in Microsoft Excel 2019. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 25.0) was used for formal analysis. Frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviations (SDs), and other descriptive statistics were computed as appropriate. Bivariate analysis (e.g., Chi‐square test and Fisher's exact test) was used to analyse the gender differences in the participants' responses. Binary logistic regression and linear regression analyses were carried out for categorical (i.e., willingness to donate organs) and continuous (i.e., knowledge and attitudes regarding organ donation) outcome variables, respectively. Statistical significance was defined as a p value of less than 0.05 for all analyses. Besides, multicollinearity (VIF and tolerance values) was tested, and no issues were found.

3. Results

3.1. Socio‐Demographic Characteristics of the Participants

The study comprised 592 participants, whose mean age was 22.63 ± 5.35. Among the participants, males accounted for 62.1%, and most were unmarried (90.5%). Most participants held a graduate degree (78.7%), belonged to nuclear families (77.2%), had a monthly income below 20,000 BDT or < 170 USD, and lived in urban areas (68.9%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of participants.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 22.63 (5.35) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 368 (62.16) |

| Female | 224 (37.84) |

| Marital Status | |

| Unmarried | 536 (90.54) |

| Married | 56 (9.46) |

| Education | |

| Higher Secondary | 101 (17.06) |

| Graduation | 466 (78.72) |

| Postgraduation | 25 (4.22) |

| Family type | |

| Nuclear family | 457 (77.2) |

| Joint family | 135 (22.8) |

| Monthly household income | |

| Less than 20,000 | 167 (28.21) |

| 20,000–30,000 | 148 (25.00) |

| 30,000–40,000 | 112 (18.92) |

| More than 40,000 | 165 (27.87) |

| Residence | |

| Urban | 408 (68.92) |

| Rural | 184 (31.08) |

3.2. Awareness, Source of Knowledge About Organ Donation

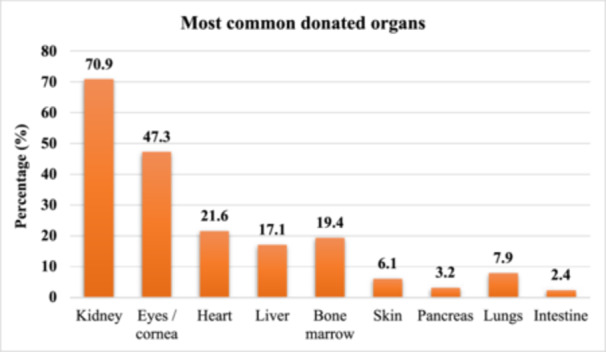

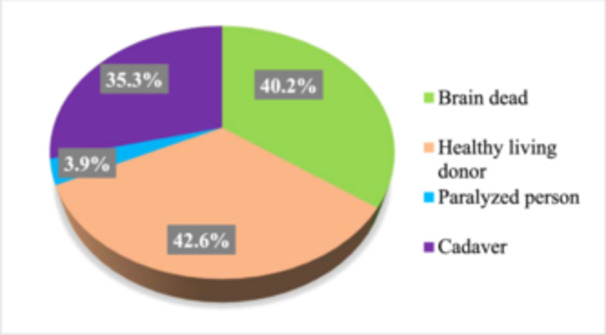

Most of the participants (84.1%) heard about organ donation, and the internet/online sources were the most reported (37.8%) source of knowledge, followed by social media (36%) and TV/radio (30.4%) (Figure 1). More than two‐thirds of the participants reported the kidney (70.9%) as the most common organ that can be donated (Figure 2). About 42.6% of the participants were healthy living donors, the best candidates to donate an organ (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Sources of knowledge regarding organ donation.

Figure 2.

Most common donated organs reported by the participants.

Figure 3.

Ideal candidate for organ donation reported by the participants.

3.3. Knowledge Regarding Organ Donation

In Table 2, the distribution of each knowledge item and its gender difference is presented. Only 30.57% correctly responded to the statement, “Cancer patients can donate organs after death.” The difference was significantly higher among males than females (32.3% vs. 27.6%, p = 0.008). About 58.4% of the participants reported that it is necessary to do screening before organ donation. However, 18.4% of the participants reported that organ donation violated their religious beliefs. Males were significantly more likely than females to follow Bangladesh's specific organ donation laws (29.3% vs. 25%, p = 0.004). The mean score of the knowledge items was 3.58 ± 2.33 out of 10, indicating an overall correct answer of 35.8%. The regression analysis by knowledge regarding organ donation is presented in Table 3. No significant association was obtained between sociodemographic variables and knowledge.

Table 2.

Distribution of knowledge items regarding organ donation and gender differences.

| Variables | Overall | Male | Female | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| People of any age group can be an organ donor. (True) | ||||

| Yes | 113 (19.09) | 68 (18.48) | 45 (20.09) | 0.802 |

| No | 282 (47.64) | 179 (48.64) | 103 (45.98) | |

| Don't know | 197 (33.28) | 121 (32.88) | 76 (33.93) | |

| It is necessary to do screening before organ donation. (True) | ||||

| Yes | 346 (58.45) | 205 (55.71) | 141 (62.95) | 0.053* |

| No | 19 (3.21) | 16 (4.35) | 3 (1.34) | |

| Don't know | 227 (38.34) | 147 (39.95) | 80 (35.71) | |

| There is a time duration for which an organ remains viable for transplant. (True) | ||||

| Yes | 254 (42.91) | 152 (41.3) | 102 (45.54) | 0.337 |

| No | 63 (10.64) | 44 (11.96) | 19 (8.48) | |

| Don't know | 275 (46.45) | 172 (46.74) | 103 (45.98) | |

| There exist some cultural barriers regarding organ donation. (True) | ||||

| Yes | 197 (33.28) | 129 (35.05) | 68 (30.36) | 0.244 |

| No | 202 (34.12) | 128 (34.78) | 74 (33.04) | |

| Don't know | 193 (32.6) | 111 (30.16) | 82 (36.61) | |

| Organ donation is against our religious beliefs. (False) | ||||

| Yes | 109 (18.41) | 72 (19.57) | 37 (16.52) | 0.599 |

| No | 287 (48.48) | 178 (48.37) | 109 (48.66) | |

| Don't know | 196 (33.11) | 118 (32.07) | 78 (34.82) | |

| Organ donation prevents or interferes with funeral arrangements. (False) | ||||

| Yes | 107 (18.07) | 77 (20.92) | 30 (13.39) | 0.052 |

| No | 280 (47.3) | 172 (46.74) | 108 (48.21) | |

| Don't know | 205 (34.63) | 119 (32.34) | 86 (38.39) | |

| Cancer patients can donate organs after death. (False) | ||||

| Yes | 76 (12.84) | 57 (15.49) | 19 (8.48) | 0.008 |

| No | 181 (30.57) | 119 (32.34) | 62 (27.68) | |

| Don't know | 335 (56.59) | 192 (52.17) | 143 (63.84) | |

| Infectious disease is a contraindication for organ donation. (True) | ||||

| Yes | 224 (37.84) | 139 (37.77) | 85 (37.95) | 0.056 |

| No | 71 (11.99) | 53 (14.4) | 18 (8.04) | |

| Don't know | 297 (50.17) | 176 (47.83) | 121 (54.02) | |

| There is not sufficient information about organ transplantation in your society. (True) | ||||

| Yes | 76 (12.84) | 50 (13.59) | 26 (11.61) | 0.243 |

| No | 389 (65.71) | 247 (67.12) | 142 (63.39) | |

| Don't know | 127 (21.45) | 71 (19.29) | 56 (25) | |

| Organ donation is legal (the existence of any law) in Bangladesh. (True) | ||||

| Yes | 164 (27.7) | 108 (29.35) | 56 (25) | 0.004 |

| No | 48 (8.11) | 39 (10.6) | 9 (4.02) | |

| Don't know | 380 (64.19) | 221 (60.05) | 159 (70.98) | |

Fisher's exact test.

Table 3.

Regression analysis by knowledge regarding organ donation.

| Variables | Mean (SD) | B | SE | t | β | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | – | < 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.888 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 3.58 (2.32) | 0.01 | 0.20 | 0.03 | < 0.01 | 0.973 |

| Male | 3.59 (2.34) | Ref. | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 3.59 (2.32) | 0.09 | 0.33 | 0.28 | 0.01 | 0.776 |

| Married | 3.5 (2.41) | Ref. | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Graduation | 3.62 (2.37) | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.827 |

| Postgraduation | 3 (1.78) | −0.56 | 0.52 | −1.08 | −0.05 | 0.279 |

| Higher secondary | 3.56 (2.25) | Ref. | ||||

| Family type | ||||||

| Nuclear family | 3.62 (2.32) | 0.16 | 0.23 | 0.71 | 0.03 | 0.478 |

| Joint family | 3.46 (2.37) | Ref. | ||||

| Monthly household income | ||||||

| 20,000–30,000 | 3.5 (2.36) | 0.06 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.829 |

| 30,000–40,000 | 3.72 (2.14) | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.98 | 0.05 | 0.326 |

| More than 40,000 | 3.71 (2.43) | 0.27 | 0.26 | 1.04 | 0.05 | 0.299 |

| Less than 20,000 | 3.44 (2.32) | Ref. | ||||

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 3.6 (2.33) | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.833 |

| Rural | 3.55 (2.33) | Ref. | ||||

3.4. Attitudes Toward Organ Donation

In Table 4, the distribution of each attitude item and its gender difference is presented. 58.9% of the participants did not perceive organ donation as an unpleasant sacrifice. The agreed/strongly agreed response towards “My family would object if I were to donate my organs” was significantly higher among females than males (45.5% vs. 42.1%, p = 0.006). Females were much more likely than males to agree that it should be possible to compensate donors or relatives of potential donors to encourage them to donate organs (39.2% vs. 28.%, p = 0.002). Only 15% of participants agreed/strongly agreed with the statement, “I feel that organ donation should be made compulsory by law.” In response, females were significantly more neutral than males (44.6% vs. 33.1%, p = 0.005). Besides, 48.6% of females, compared to 40.4% of males, believe that the health service related to organ donation in Bangladesh is ineffective (p = 0.016). The mean score of the attitude items was 31.86 ± 4.34 out of 50, indicating an overall correct answer of 63.7%. The regression analysis by attitudes regarding organ donation was presented in Table 5, where females showed a more positive attitude than males (β = 0.09, p = 0.024).

Table 4.

Distribution of attitudes items regarding organ donation and gender differences.

| Variables | Overall | Male | Female | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| I think of organ donation as an unpleasant sacrifice. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 147 (24.83) | 95 (25.82) | 52 (23.21) | 0.252* |

| Disagree | 202 (34.12) | 121 (32.88) | 81 (36.16) | |

| Neutral | 191 (32.26) | 114 (30.98) | 77 (34.38) | |

| Agree | 42 (7.09) | 29 (7.88) | 13 (5.8) | |

| Strongly agree | 10 (1.69) | 9 (2.45) | 1 (0.45) | |

| I think that the body will be disfigured when the organs are removed. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 110 (18.58) | 74 (20.11) | 36 (16.07) | 0.185* |

| Disagree | 254 (42.91) | 150 (40.76) | 104 (46.43) | |

| Neutral | 177 (29.9) | 109 (29.62) | 68 (30.36) | |

| Agree | 40 (6.76) | 25 (6.79) | 15 (6.7) | |

| Strongly agree | 11 (1.86) | 10 (2.72) | 1 (0.45) | |

| I think donating an organ can cause harmful effects/complications. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 76 (12.84) | 56 (15.22) | 20 (8.93) | 0.095* |

| Disagree | 189 (31.93) | 116 (31.52) | 73 (32.59) | |

| Neutral | 192 (32.43) | 115 (31.25) | 77 (34.38) | |

| Agree | 120 (20.27) | 69 (18.75) | 51 (22.77) | |

| Strongly agree | 15 (2.53) | 12 (3.26) | 3 (1.34) | |

| My family would object if I were to donate my organs. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 65 (10.98) | 49 (13.32) | 16 (7.14) | 0.006 |

| Disagree | 91 (15.37) | 66 (17.93) | 25 (11.16) | |

| Neutral | 179 (30.24) | 98 (26.63) | 81 (36.16) | |

| Agree | 206 (34.8) | 121 (32.88) | 85 (37.95) | |

| Strongly agree | 51 (8.61) | 34 (9.24) | 17 (7.59) | |

| I find it important that my body goes untouched into the grave. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 91 (15.37) | 65 (17.66) | 26 (11.61) | 0.121 |

| Disagree | 167 (28.21) | 104 (28.26) | 63 (28.13) | |

| Neutral | 206 (34.8) | 126 (34.24) | 80 (35.71) | |

| Agree | 97 (16.39) | 59 (16.03) | 38 (16.96) | |

| Strongly agree | 31 (5.24) | 14 (3.8) | 17 (7.59) | |

| I will allow organ donation from my family after Brain's death. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 83 (14.02) | 60 (16.3) | 23 (10.27) | 0.291 |

| Disagree | 105 (17.74) | 66 (17.93) | 39 (17.41) | |

| Neutral | 256 (43.24) | 153 (41.58) | 103 (45.98) | |

| Agree | 127 (21.45) | 75 (20.38) | 52 (23.21) | |

| Strongly agree | 21 (3.55) | 14 (3.8) | 7 (3.13) | |

| I think more people should know about organ donation and transplantation. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 91 (15.37) | 65 (17.66) | 26 (11.61) | 0.322 |

| Disagree | 49 (8.28) | 32 (8.7) | 17 (7.59) | |

| Neutral | 117 (19.76) | 72 (19.57) | 45 (20.09) | |

| Agree | 219 (36.99) | 131 (35.6) | 88 (39.29) | |

| Strongly agree | 116 (19.59) | 68 (18.48) | 48 (21.43) | |

| It should be possible to motivate donors or relatives of potential donors with compensation, to make them donate organs. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 73 (12.33) | 56 (15.22) | 17 (7.59) | 0.002 |

| Disagree | 82 (13.85) | 61 (16.58) | 21 (9.38) | |

| Neutral | 207 (34.97) | 123 (33.42) | 84 (37.5) | |

| Agree | 194 (32.77) | 106 (28.8) | 88 (39.29) | |

| Strongly agree | 36 (6.08) | 22 (5.98) | 14 (6.25) | |

| I feel that organ donation should be made compulsory by law. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 124 (20.95) | 90 (24.46) | 34 (15.18) | 0.005 |

| Disagree | 157 (26.52) | 107 (29.08) | 50 (22.32) | |

| Neutral | 222 (37.5) | 122 (33.15) | 100 (44.64) | |

| Agree | 67 (11.32) | 37 (10.05) | 30 (13.39) | |

| Strongly agree | 22 (3.72) | 12 (3.26) | 10 (4.46) | |

| The health service related to organ donation in Bangladesh is ineffective. | ||||

| Strongly disagree | 58 (9.8) | 44 (11.96) | 14 (6.25) | 0.016 |

| Disagree | 83 (14.02) | 61 (16.58) | 22 (9.82) | |

| Neutral | 193 (32.6) | 114 (30.98) | 79 (35.27) | |

| Agree | 215 (36.32) | 125 (33.97) | 90 (40.18) | |

| Strongly agree | 43 (7.26) | 24 (6.52) | 19 (8.48) | |

Fisher's exact test.

Table 5.

Regression analysis by attitudes regarding organ donation.

| Mean | B | SE | t | β | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | – | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.31 | −0.01 | 0.757 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 32.38 (4.33) | 0.83 | 0.37 | 2.26 | 0.09 | 0.024 |

| Male | 31.55 (4.32) | Ref. | ||||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Unmarried | 31.91 (4.31) | 0.44 | 0.61 | 0.73 | 0.03 | 0.468 |

| Married | 31.46 (4.6) | Ref. | ||||

| Education | ||||||

| Graduation | 31.76 (4.33) | −0.29 | 0.48 | −0.61 | −0.02 | 0.540 |

| Postgraduation | 33.12 (3.84) | 1.07 | 0.97 | 1.11 | 0.05 | 0.269 |

| Higher Secondary | 32.05 (4.47) | Ref. | ||||

| Family type | ||||||

| Nuclear family | 31.88 (4.39) | 0.07 | 0.43 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 0.879 |

| Joint family | 31.81 (4.16) | Ref. | ||||

| Monthly household income | ||||||

| 20,000–30,000 | 32.11 (4.44) | 0.35 | 0.49 | 0.72 | 0.04 | 0.471 |

| 30,000–40,000 | 31.46 (4.27) | −0.29 | 0.53 | −0.55 | −0.03 | 0.584 |

| More than 40,000 | 32.03 (4.38) | 0.28 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.03 | 0.563 |

| Less than 20,000 | 31.75 (4.27) | Ref. | ||||

| Residence | ||||||

| Urban | 31.92 (4.39) | 0.19 | 0.39 | 0.49 | 0.02 | 0.622 |

| Rural | 31.73 (4.22) | Ref. | ||||

3.5. The Intention to Donate an Organ

More than one‐third (35.1%) of the participants indicated a willingness to donate their organs after death, whereas 64.9% responded undecided or unwilling (Figure 4). As per the regression analysis, no significant association was obtained between socio‐demographic variables and willingness to donate an organ, although about 64% and 57% of males and females, respectively, had no intention to donate their organs (Table 6). About 86.2% of participants reported that saving somebody's life would be the driving factor for organ donation (Table 7). Other reasons included a responsibility to society (33.2%) and compassion (22.4%). The family objection was mentioned by 40.4% of those who were unwilling or hesitant to donate organs, followed by health complications (34.4%), fear of disfigurement (31.1%), and religious barriers (26.8%).

Figure 4.

Participants intention towards organ donation.

Table 6.

Intention of organ donation among participants.

| Variables | Willingness | Undecided/unwillingness | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Age | 23.01 (5.79) | 22.42 (5.1) | 1.02 (0.989–1.051) | 0.208 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 134 (36.41) | 234 (63.59) | 1.161 (0.818–1.647) | 0.404 |

| Female | 74 (33.04) | 150 (66.96) | Ref. | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 22 (39.29) | 34 (60.71) | 1.218 (0.692–2.142) | 0.495 |

| Unmarried | 186 (34.7) | 350 (65.3) | Ref. | |

| Education | ||||

| Graduation | 172 (36.91) | 294 (63.09) | 1.243 (0.525–2.941) | 0.620 |

| Higher Secondary | 28 (27.72) | 73 (72.28) | 0.815 (0.316–2.1) | 0.672 |

| Postgraduation | 8 (32) | 17 [68] | Ref. | |

| Family type | ||||

| Nuclear family | 158 (34.57) | 299 (65.43) | 0.898 (0.603–1.339) | 0.598 |

| Joint family | 50 (37.04) | 85 (62.96) | Ref. | |

| Monthly household income | ||||

| Less than 20,000 | 53 (31.74) | 114 (68.26) | 0.715 (0.455–1.123) | 0.146 |

| 20,000–30,000 | 54 (36.49) | 94 (63.51) | 0.884 (0.559–1.397) | 0.597 |

| 30,000–40,000 | 36 (32.14) | 76 (67.86) | 0.729 (0.44–1.207) | 0.219 |

| More than 40,000 | 65 (39.39) | 100 (60.61) | Ref. | |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 146 (35.78) | 262 (64.22) | 1.097 (0.76–1.582) | 0.622 |

| Rural | 62 (33.7) | 122 (66.3) | Ref. | |

Table 7.

Information related to the intention of organ donation.

| Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Influential factors regarding willingness to donate organs a | ||

| Somebody's life | 319 | 86.2% |

| Out of compassion | 83 | 22.4% |

| To satisfy one's own religious beliefs | 38 | 10.3% |

| Financial reasons | 45 | 12.2% |

| As a responsibility to the society | 123 | 33.2% |

| Reasons for the unwillingness of organ donation b | ||

| Afraid of disfigurement | 114 | 31.1% |

| Family objection | 148 | 40.4% |

| No financial benefits | 17 | 4.6% |

| Religious barrier | 98 | 26.8% |

| Lack of knowledge | 93 | 25.4% |

| Health complications | 126 | 34.4% |

| Fear of the operation itself | 86 | 23.5% |

| Too young/old to donate an organ | 50 | 13.7% |

Sample was limited to those who were willing to donate an organ (n = 208).

Sample was limited to those who were unwilling/hesitant to donate an organ (n = 384).

4. Discussion

Organ failure and organ donation demand have increased globally [29]. The need for organ transplants increases in direct proportion to the number of people with chronic illnesses that cause end‐organ failure. Policymakers must be aware of the barriers to effectively encouraging and disseminating information regarding organ donation. Public awareness and attitude are essential for resolving organ scarcity [26, 30].

The present study depicted that the mean knowledge and attitude scores were 3.58 ± 2.33 and 31.86 ± 4.34, respectively, indicating that knowledge is not satisfactory while attitudes are progressive. The present study also found most participants (84.1%) had heard about organ donation. This percentage was slightly lower than other studies conducted in India [31] and Saudi Arabia [32]. In incomparable research in Bangladesh among medical professionals, students, patients, and relatives, the rate was found at 85% [20]. Most participants in this study claimed they learned about organ donation online/on the Internet. Comparable patterns were found in a study of Pakistani citizens and Brazil [30, 33]. Contrarily, other studies of adults from Spain and Saudi Arabia showed that television was the primary information source [34, 35]. The study population was mostly educated and always connected to the internet for their everyday activities related to work and studies. Therefore, this finding is plausible. This suggests that organ donation awareness campaigns in Bangladesh should use the Internet or social media.

Most participants said “kidney” when asked about organs that can be given, which mirrors previous research [27, 30, 32]. In contrast, a similar study among medical students in India revealed that the eye is the most donated organ [1]. In this study, most of the participants reported healthy living donors as the best candidates who could donate organs, followed by cadavers. Earlier research among Pakistani medical students found that while fourth‐year medical students reported cadaveric organ donation, first‐year medical students reported a living, healthy donor [36]. This might be because organ donation is not commonplace in Bangladesh, and many people have misunderstandings about why they prefer living donors over cadavers, highlighting the need for education on organ donation in Bangladesh.

The current study indicates poor knowledge about organ donation; just over one‐third (35.6%) of the participants gave accurate answers. Similarly, earlier studies also revealed a lower degree of understanding regarding organ donation [37, 38]. However, similar studies conducted in India and Pakistan found a higher percentage of participants with adequate knowledge than the present study, which was 57% and 60%, respectively [30, 38]. Furthermore, there are two possible explanations for this disparity. Firstly, this might be due to the research population being different. Secondly, compared to the previous study, various knowledge factors were employed in our investigation to measure participants' knowledge status about organ donation. However, just a little less than a third of the participants (30.1%) were aware that cancer patients could not donate organs after they died. In a comparative study of Indian medical students, 76.5% of those surveyed knew of an issue more significant than twofold more remarkable than the present study [1]. About 58.4% of the participants reported that it is necessary to do screening before organ donation. Pre‐transplant screening of potential organ donors and recipients was critical to solid organ transplantation's success [39].

Religious sentiments are essential in organ donation and transplantation worldwide [12]. About one‐fifth (18.4%) of the participants in this survey reported that their religion forbade them from participating in organ donation. A study in Bangladesh indicated that 12.6% of participants believed organ donation was against their faith [20]. Muslim academics and believers have diverse views about organ donation for transplantation because the primary sources of Islamic jurisprudence, the Quran and Hadith, do not have clear rules on the matter. However, this prohibition may be broken in some situations, such as when someone's life is in danger, as one of the core principles of Islam (The Holy Quran, Ayah al‐Ma'idah,5:32). While there are many positive viewpoints, there are also negative ones [11]. Muslims are confused about whether they should give their organs after death due to the disparity in opinions among Islamic experts [17]. According to a survey conducted in the United Kingdom, there was no association between religious beliefs and attitudes toward organ donation [40]. In contrast, religious obstacles were shown to be the most common reason for organ refusal in Bangladesh [15, 21].

Strikingly, only 27.7% of the participants were aware that Bangladesh has a specific law regarding organ donation, contrary to a previous study among Bangladeshi physicians, which found that more than half (57%) of the participants were aware of Bangladesh's organ donation law, the “Human Organ Transplant Act, 1999” [19]. The current result might be explained by the fact that the research population differed, and physicians must be more educated about government organ donation rules. Almost three‐fifths (63.7%) of the participants correctly answered all attitude questions, indicating that, despite having less knowledge about organ donation, most participants had positive attitudes. Studies conducted among Indian and Ethiopian people also found a higher prevalence of positive attitudes regarding organ donation [26, 41].

The present study revealed that more than one‐third (34.8%) of the participants agreed that their families would object if they were to donate organs, which is supported by a previous Indian study. However, the agreement was 21.4% [37]. The most significant barrier to organ donation was identified in a prior study as families' refusal to give consent [42]. In addition to their close‐knit familial ties and widespread religious misconceptions, Bangladeshis are often concerned about giving their organs away after death [15]. Only approximately 15% of those surveyed agreed or strongly agreed that organ donation should be made a legal requirement. This raises issues related to the complex relationships between biomedicine, organ donation, and transplantation and societal norms, religion, and faith.

According to the study, females exhibited more positive attitudes regarding organ donation than males. In contrast, Dibaba et al. [26] found that being of the male sex was linked to a positive attitude regarding organ donation. However, a study done in Spain reported that being of the female sex was related to a positive attitude [43], which corresponds to the present finding. This might be because women are more empathetic, sensitive, and compassionate. As a result, the emotional quotient may significantly influence women's reactions, particularly in times of hardship or crisis. Women are perceived as more willing to give up things and more likely to donate an organ, particularly if a family member is in need. Over one‐third of those who participated in this study said they would be ready to donate their organs to anyone who needed them. In a previous study in Bangladesh, the willingness to give organs was 54.9% among physicians [19]. On the contrary, positive willingness among the general people regarding organ donation was found in studies conducted in Lebanon [44], Nepal [37], China [25], and Saudi Arabia [45].

The current study found no association between willingness and socio‐demographic factors such as age, gender, or marital status. In contrast, a previous Indian study found a significant association between the willingness to donate organs and the age, gender, education, and economic status of the participants [41]. In the current study, a significant reason for agreement on organ donation (86.2%) was the wish to save someone's life. Consistent with a prior study from Bangladesh, which demonstrates that organ donation is primarily done out of compassion and societal duty, saving someone's life is a compelling incentive to donate an organ [19]. In conformity with the present study, previous studies revealed that, besides saving another person's life, some respondents believed it was a responsibility [46, 47]. On the contrary, a previous Bangladeshi study found religious fear as the primary reason, followed by family constraints and fear of disfigurement [19].

The discussion above brings up several issues regarding the complex relationships between biomedicine, organ donation, and transplantation and cultural expectations, religious beliefs, and personal faith. Amendments are required to the Bangladesh Organ Donation Act of 1999, which restricted the donor pool by limiting recipients and donors to members of the donor's extended family. Revision of organ donation guidelines is important to boost organ donation for transplantation in context with the current public health crisis and the sociocultural framework.

5. Limitations

A few limitations to the study should be considered before drawing conclusions. First, the study was done online because of the COVID‐19 pandemic, therefore, all of the respondents were educated. Second, the cross‐sectional approach of the study limits the detection of causal correlations between variables. There could be some potential unobserved confounding factors. Third, convenience sampling was used to choose the respondents, which may have resulted in some bias in the representation of our respondents. Finally, the results may not represent actual attitudes and actions since respondents may try to produce socially acceptable responses.

6. Recommendations

However, the results of this study have some implications for enhancing Bangladesh's organ donation setting. First, it is essential to educate the public on organ donation's legal and moral aspects nationwide by organizing events and campaigns and ensuring people are informed of transplant and organ donation procedures. Every accessible strategy should be used to the utmost extent that it is practical, including social media, campaigns, advertisements, exhibitions, curriculum, and religious institutions. Second, it is crucial to modernize the human resources and medical infrastructure needed for organ transplantation, including training programs and hospital facilities; recruit counselors to ask prospective donors' grieving families for consent; allot necessary funds for transplant care. Third, a national registry where people can register their decision to give their tissues and organs must be established in Bangladesh. Finally, future research may include public education through interventional research in a range of situations. To establish strategies that are suited for the given environment and to gain a deeper understanding of the challenges, qualitative research is crucial.

7. Conclusions

Despite their positive attitudes, the intention of participants to donate organs was relatively low due to family concerns, health complications, a lack of knowledge, and socio‐cultural and religious perceptions. All these concerns should be addressed and prioritized when developing an awareness program.

Author Contributions

Mst Sabrina Moonajilin: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, funding acquisition, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing, project administration, supervision, validation. Rajon Banik: data curation, formal analysis, writing–review and editing, software. Md. Saiful Islam: data curation, formal analysis, writing–review and editing, software. Kifayat Sadmam Ishadi: data curation. Ismail Hosen: formal analysis, writing–review and editing, validation. Hailay Abrha Gesesew: writing–review and editing, validation. Paul R. Ward: writing–review and editing, validation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the publication of this research output. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate all those who participated in this study voluntarily.

The Jahangirnagar University Research Fund funded the study for 2021–2022. The funding award number is N/A. Besides, the funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, the decision to publish, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Ganta S. R., Pamarthi K., and L. P. K. K., “Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Organ Donation and Transplantation Among Undergraduate Medical Students in North Coastal Andhra Pradesh,” International Journal Of Community Medicine And Public Health 5, no. 3 (2018): 1064–1068. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Whisenant D. P. and Woodring B., “Improving Attitudes and Knowledge Toward Organ Donation Among Nursing Students,” International Journal of Nursing Education Scholarship 9 (2012): 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Xiong X., Lai K., Jiang W., et al., “Understanding Public Opinion Regarding Organ Donation in China: A Social Media Content Analysis,” Science Progress 104, no. 2 (2021): 368504211009665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation . 2024. Available from: https://www.transplant-observatory.org/.

- 5. Health Resources & Services Administration . Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Modernization Initiative 2024. Available from: https://www.organdonor.gov/.

- 6. Lewis J. and Gardiner D., “Ethical and Legal Issues Associated With Organ Donation and Transplantation,” Surgery (Oxford) 41, no. 9 (2023): 552–558. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Da Silva I. R. F. and Frontera J. A., “Worldwide Barriers to Organ Donation,” JAMA Neurology 72, no. 1 (2015): 112–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mostafazadeh‐Bora M. and Zarghami A., “The Crucial Role of Cultural and Religious Beliefs on Organ Transplantation,” International Journal of Organ Transplantation Medicine 8, no. 1 (2017): 54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bokek‐Cohen Y., Abu‐Rakia R., Azuri P., and Tarabeih M., “The View of the Three Monotheistic Religions Toward Cadaveric Organ Donation,” OMEGA ‐ Journal of Death and Dying 85, no. 2 (2022): 429–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tarabeih M., Bokek‐Cohen Y., and Azuri P., “Evaluating Health‐Related Quality of Life and Emotions in Muslim and Jewish Kidney Transplant Patients,” International Journal for Quality in Health Care 33, no. 4 (2021): mzab096, 10.1093/intqhc/mzab096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tarabeih M., Abu‐Rakia R., Bokek‐Cohen Y., and Azuri P., “Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Unwillingness to Donate Organs Post‐Mortem,” Death Studies 46, no. 2 (2022): 391–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tarabeih M., Bokek‐Cohen Y., Abu Rakia R., Nir T., Coolidge N. E., and Azuri P., “Religious Observance and Perceptions of End‐Of‐Life Care,” Nursing Inquiry 27, no. 3 (2020): e12347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Raghuram L. and Shroff S., “Religious Leaders and Organ Donation – An Indian Experience,” TRANSPLANTATION 101 (2017): S59. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cotrau P., Hodosan V., Vladu A., Daina C., Daina L. G., and Pantis C., “Ethical, Socio‐Cultural and Religious Issues in Organ Donation,” Maedica ‐ A Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 1 (2019): 12–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Siraj M. S., “Deceased Organ Transplantation in Bangladesh: The Dynamics of Bioethics, Religion and Culture,” HEC Forum 34, no. 2 (2022): 139–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bari A., Islam S., Nobi F., et al, “#2311 Comparative Analysis of Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Deceased Donation in Health Care Workers and the General Population,” Nephrology, Dialysis, Transplantation 39, no. Suppl_1 (2024): gfae069‐0984‐2311. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Siraj M. S., “Family‐Based Consent and Motivation for Familial Organ Donation in Bangladesh: An Empirical Exploration,” Developing world bioethics. Published ahead of print, October 19, 2023. 10.1111/dewb.12431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Siraj M. S., “The Human Organ Transplantation Act in Bangladesh: Towards Proper Family‐Based Ethics and Law,” Asian Bioethics Review 13, no. 3 (2021): 283–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Billah M. M., Farzana H., Latif A., et al., “Knowledge and Attitude of Bangladeshi Physicians Towards Organ Donation and Transplantation,” Bangladesh Critical Care Journal 4, no. 1 (2016): 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Anwar A. S. M. T. and Lee J. M., “A Survey on Awareness and Attitudes Toward Organ Donation Among Medical Professionals, Medical Students, Patients, and Relatives in Bangladesh,” Transplantation Proceedings 52, no. 3 (2020): 687–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Farid M. S. and Naim Mou T. B., “Religious, Cultural and Legal Barriers to Organ Donation: The Case of Bangladesh,” Bangladesh Journal of Bioethics 12, no. 1 (2021): 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mitra P., Hossain M. G., Hossan M. E., et al., “A Decade of Live Related Donor Kidney Transplant: Experience in a Tertiary Care Hospital of Bangladesh,” BIRDEM Medical Journal 8, no. 3 (2018): 198–202. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tam W. W. S., Suen L. K. P., and Chan H. Y. L., “Knowledge, Attitudes and Commitment Toward Organ Donation Among Nursing Students in Hong Kong,” Transplantation Proceedings 44, no. 5 (2012): 1196–1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kaiser G. M., “The Effect of Education on the Attitude of Medical Students Towards Organ Donation,” Annals of Transplantation 17, no. 1 (2012): 140–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fan X., Li M., Rolker H., et al., “Knowledge, Attitudes and Willingness to Organ Donation Among the General Public: A Cross‐Sectional Survey in China,” BMC Public Health 22, no. 1 (2022): 918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dibaba F. K., Goro K. K., Wolide A. D., et al., “Knowledge, Attitude and Willingness to Donate Organ Among Medical Students of Jimma University, Jimma Ethiopia: Cross‐Sectional Study,” BMC Public Health 20, no. 1 (2020): 799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ali M., “Organ Transplantation in Bangladesh ‐ Challenges and Opportunities,” Ibrahim Medical College Journal 6, no. 1 (2013): i–ii. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Asimakopoulou E., Stylianou V., Dimitrakopoulos I., and Argyriadis A., “Bellou‐Mylona P. Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Organ Transplantation Among Cyprus Residents,” The Journal of Nursing Research 29, no. 1 (2020): e132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nadeem Ahmad K. and Taqi Taufique K., “Organ Donation: Demand and Supply.” in Current Challenges and Advances in Organ Donation and Transplantation, eds. Georgios T. (Rijeka: IntechOpen, 2023. p. Ch. 4). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Khalid F., Khalid A. B., Muneeb D., Shabir A., Fayyaz D., and Khan M., “Level of Knowledge and Attitude Regarding Organ Donation: A Community‐Based Study From Karachi, Pakistan,” BMC Research Notes 12, no. 1 (2019): 309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Balwani M. R., Gumber M. R., Shah P. R., et al., “Attitude and Awareness Towards Organ Donation in Western India,” Renal Failure 37, no. 4 (2015): 582–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khushaim L., “The Knowledge, Perception and Attitudes Towards Organ Donation Among General Population ‐ Jeddah, Saudi Arabia,” International Journal of Advanced Research 6, (2018): 1255–1269. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Videira M. A. R., dos Santos Silva M. A., Costa G. P., et al., “Knowledge, Attitude, and Factors That Influence Organ Donation and Transplantation in a Brazilian City,” Journal of Public Health 32, no. 1 (2024): 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Almela‐Baeza J., Febrero B., Ros I., et al., “The Influence of Mass Media on Organ Donation and Transplantation in Older People,” Transplantation Proceedings 52, no. 2 (2020): 503–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alghanim S. A., “Knowledge and Attitudes Toward Organ Donation: A Community‐Based Study Comparing Rural and Urban Populations,” Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation: An Official Publication of the Saudi Center for Organ Transplantation, Saudi Arabia 21, no. 1 (2010): 23–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ali N. F., Qureshi A., Jilani B. N., and Zehra N., “Knowledge and Ethical Perception Regarding Organ Donation Among Medical Students,” BMC Medical Ethics 14 (2013): 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gc A., Timilsina A., and Kc V. K., “Knowledge and Attitude of Organ Donation Among University Students in Pokhara,” Journal of Biomedical Research & Environmental Sciences 1, no. 8 (2020): 452–457, 10.37871/jbres1177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Devi D. K., Leondra D. M. L., and Poovitha D. M. R., “Knowledge, Attitude and Practice of Organ Donation in Urban Areas of Puducherry – A Community Based Study,” Public Health Review: International Journal of Public Health Research 5, no. 2 (2018): 82–91. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Malinis M. and Boucher H. W., “Screening of Donor and Candidate Prior to Solid Organ Transplantation‐Guidelines From the American Society of Transplantation Infectious Diseases Community of Practice,” Clinical Transplantation 33, no. 9 (2019): e13548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Coad L., Carter N., and Ling J., “Attitudes of Young Adults From the UK Towards Organ Donation and Transplantation,” Transplantation Research 2, no. 1 (2013): 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vijayalakshmi P., Sunitha T. S., Gandhi S., Thimmaiah R., and Math S. B., “Knowledge, Attitude and Behaviour of the General Population Towards Organ Donation: An Indian Perspective,” The National Medical Journal of India 29, no. 5 (2016): 257–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Yousefi H., Roshani A., and Nazari F., “Experiences of the Families Concerning Organ Donation of a Family Member with Brain Death,” Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research 19, no. 3 (2014): 323–330. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ríos A., López‐Navas A., López‐López A., et al., “A Multicentre and Stratified Study of the Attitude of Medical Students Towards Organ Donation in Spain,” Ethnicity & Health 24, no. 4 (2019): 443–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. El Abed El Rassoul A., Razzak R. A., Alwardany A., Moubarak M., and Hashim H. T., “Attitudes to Organ Donation in Lebanon: A Cross‐Sectional Survey,” Ethics, Medicine and Public Health 31 (2023): 100952. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Alghalyini B., Zaidi A. R. Z., Faroog Z., et al., “Awareness and Willingness Towards Organ Donation Among Riyadh Residents: A Cross‐Sectional Study,” Healthcare 12, no. 14 (2024): 1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Alwahaibi N., Al Wahaibi A., and Al Abri M., “Knowledge and Attitude About Organ Donation and Transplantation Among Omani University Students,” Frontiers in Public Health 11 (2023), 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1115531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Soqia J., Ataya J., Alhomsi R., et al., “Attitudes and Factors Influencing Organ Donation Decision‐Making in Damascus, Syria: A Cross‐Sectional Study,” Scientific Reports 13, no. 1 (2023): 18150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.